People’s Knowledge of Illegal Chinese Pangolin Trade Routes in Central Nepal

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Methods

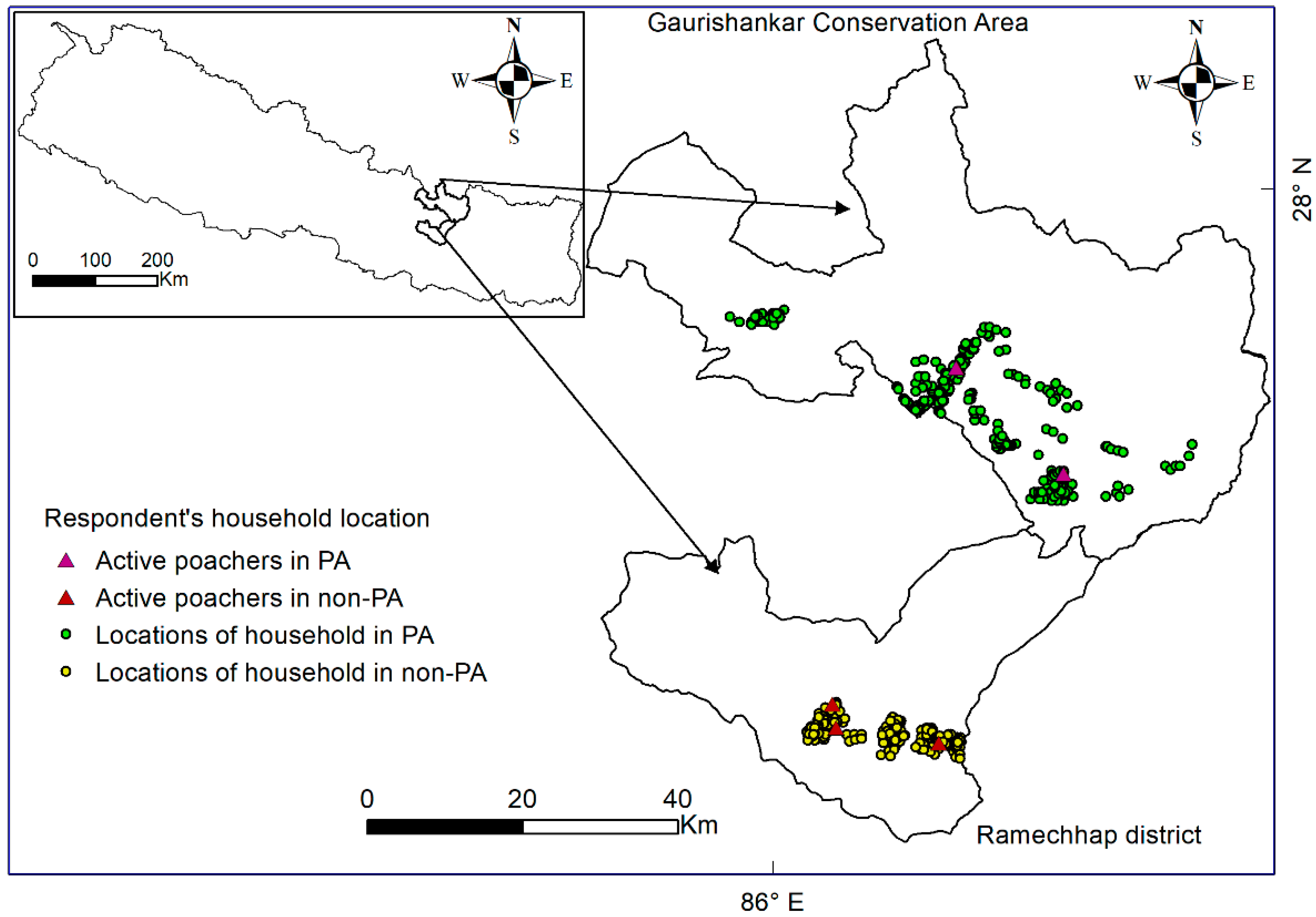

2.1. Study Area

2.2. Data Collection

3. Results

3.1. Characteristics of Traders/Poachers

3.2. Trade Reports

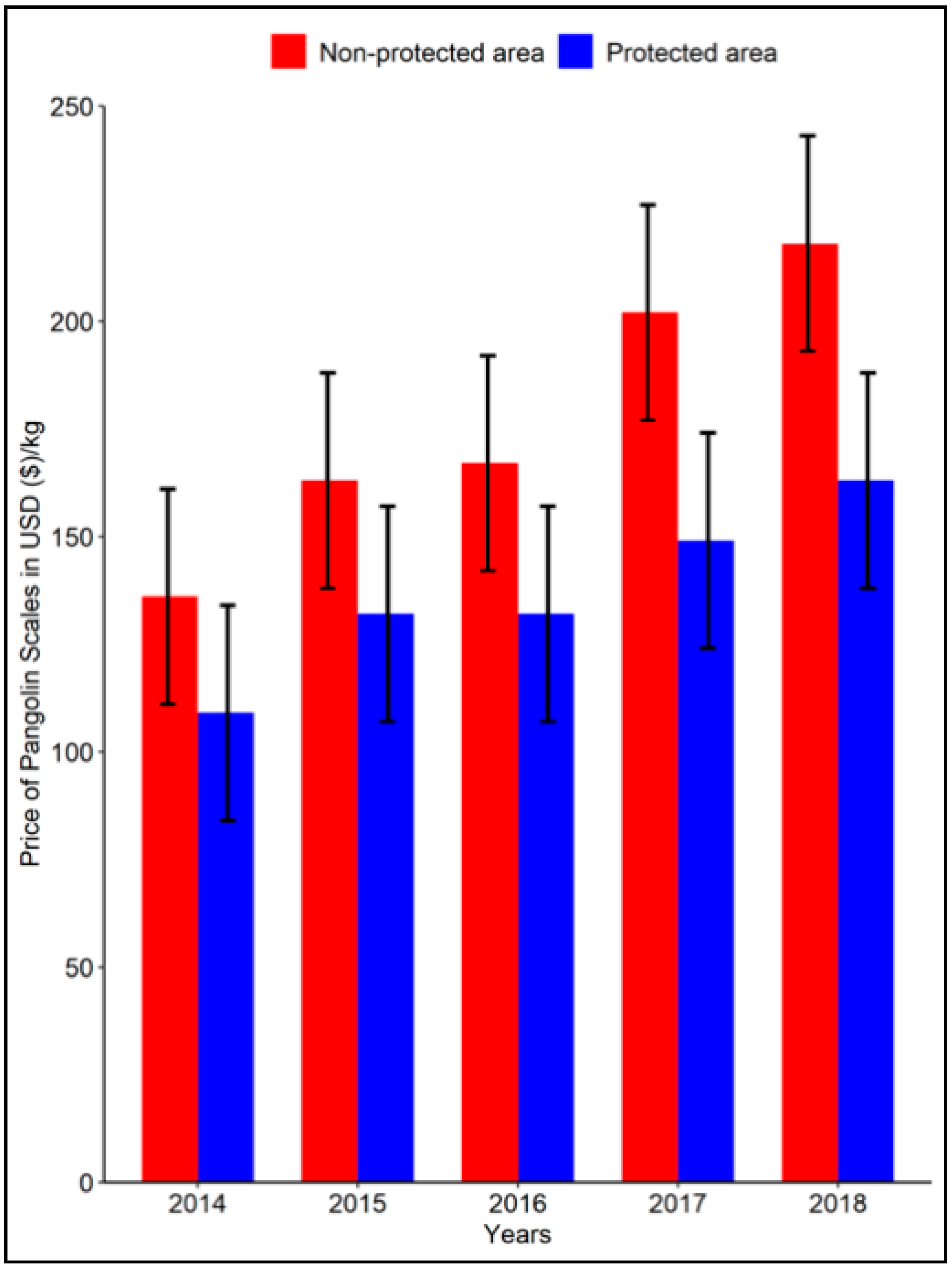

3.3. Trade Routes and Prices

4. Discussion

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Newton, P.; Van Thai, N.; Roberton, S.; Bell, D. Pangolins in peril: Using local hunters’ knowledge to conserve elusive species in Vietnam. Endanger. Species Res. 2008, 6, 41–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jnawali, S.R.; Baral, H.S.; Lee, S.; Subedi, N.; Acharya, K.P.; Upadhyay, G.P.; Pandey, M.; Shrestha, R.; Joshi, D.; Lamichhane, B.R.; et al. The status of Nepal’s Mammals: The National Red List Series; Department of National Parks and Wildlife Conservation: Kathmandu, Nepal, 2011.

- Baker, F. Assessing the Asian Industry Link in the Intercontinental Trade of African Pangolin, Gabon. Master’s Thesis, Imperial College London, London, UK, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Katuwal, H.B.; Neupane, K.R.; Adhikari, D.; Sharma, M.; Thapa, S. Pangolins in eastern Nepal: Trade and ethno-medicinal importance. J. Threat. Taxa 2015, 7, 7563–7567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Challender, D.; Waterman, C. Implementation of CITES Decision2 17.239 b) and 17.240 on Pangolins (Manis spp.); Prepared by IUCN for the CITES Secretariat. SC69 Doc; IUCN: Gland, Switzerland, 2017; Volume 57. [Google Scholar]

- Challender, D.; Wu, S.; Kaspal, P.; Khatiwada, A.; Ghose, A.; Ching-Min Sun, N.; Mohapatra, R.K.; Laxmi Suwal, T. Manis Pentadactyla. The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species 2019: E.T12764A168392151. Available online: https://dx.doi.org/10.2305/IUCN.UK.2019-3.RLTS.TI2764A168392151.en (accessed on 15 November 2019).

- Heinrich, S.; Wittman, T.A.; Ross, J.V.; Shepherd, C.R.; Challender, D.W.S.; Cassey, P. The Global Trafficking of Pangolins: A Comprehensive Summary of Seizures and Trafficking Routes from 2010–2015; TRAFFIC; Southeast Asia Regional Office: Petaling Jaya, Selangor, Malaysia, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Department of National Parks and Wildlife Conservation. Pangolin Conservation Action Plan for Nepal (2018–2022); Department of National Parks and Wildlife Conservation and Department of Forests: Kathmandu, Nepal, 2018.

- Zhou, Z.M.; Zhou, Y.; Newman, C.; Macdonald, D.W. Scaling up pangolin protection in China. Front. Ecol. Environ. 2014, 12, 97–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Davis, E.O.; Glikman, J.A.; Crudge, B.; Dang, V.; Willemsen, M.; Nguyen, T.; O’Connor, D.; Bendixen, T. Consumer demand and traditional medicine prescription of bear products in Vietman. Biol. Conserv. 2019, 235, 119–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Challender, D.W.S.; Sas-Rolfes, M.; Ades, G.W.J.; Chin, J.S.C.; Sun, N.C.-M.; Chong, J.U.; Connelly, E.; Hywood, L.; Luz, S.; Mohapatra, R.K.; et al. Evaluating the feasibility of pangolin farming and its potential conservation impact. Glob. Ecol. Conserv. 2019, 20, e00714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crudge, B.; Nguyen, T.; Cao, T.T. The challenges and conservation implications of bear bile farming in Viet Nam. Oryx 2018, 54, 252–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katuwal, H.B.; Sharma, H.P.; Parajuli, K. Anthropogenic impacts on the occurrence of the critically endangered Chinese pangolin (Manis pentadactyla) in Nepal. J. Mammal. 2017, 98, 1667–1673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, H.P.; Rimal, B.; Zhang, M.; Sharma, S.; Poudyal, L.P.; Maharjan, S.; Kunwar, R.; Kaspal, P.; Bhandari, N.; Baral, L.; et al. Potential distribution of the critically endangered Chinese Pangolin (Manis pentadactyla) in different land covers of Nepal: Implications for conservation. Sustainability 2020, 12, 1282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Sharma, S.; Sharma, H.P.; Chaulagain, C.; Katuwal, H.B.; Belant, J.L. Estimating occupancy of Chinese pangolin (Manis pentadactyla) in a protected and non-protected area of Nepal. Ecol. Evol. 2020, 10, 4303–4313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- CITES. Prop. 11.13. Manis crassicaudata, Manis pentadactyla, Manis javanica. Transfer from Appendix II to Appendix I (India, Nepal, Sri Lanka, United States). 2000. Available online: https://www.cites.org/eng/app/appendices.php (accessed on 16 June 2020).

- Chukwuone, N.A. Socio-economic determinants of cultivation of non-wood forest products in southern Nigeria. Biodiver. Conserv. 2009, 18, 339–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rao, M.; McGowan, P.J.K. Wild-meat use, food security, livelihoods, and conservation. Conserv. Biol. 2002, 16, 580–583. [Google Scholar]

- Milliken, T. Illegal Trade in Ivory and Rhino Horn: An Assessment Report to Improve Law Enforcement under Wildlife TRAPS Project; USAID and TRAFFIC, International: Cambridge, UK, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Duffy, R. Nature Crime: How we’re Getting Conservation Wrong; New Haven, Yale University Press: New Haven, CT, USA; London, UK, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- IFAW. Killing with Keystrokes: An Investigation of the Illegal Wildlife Trade on the World Wide Web; IFAW: Brussels, Belgium, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- TRAFFIC. What’s Driving the Wildlife Trade? A Review of Expert Opinion on Economic and Social Drivers of the Wildlife Trade and Trade Control Efforts in Cambodia, Indonesia, Lao PDR and Vietnam; World Bank: Washington, DC, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Biggs, D.; Cooney, R.; Roe, D.; Dublin, H.; Allan, J.; Challender, C.; Skinner, D. Engaging Local Communities in Tackling Illegal Wildlife Trade: Can a ‘Theory of Change’ Help? Discussion Paper; IIED: London, UK, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Brack, D.; Hayman, G. International Environmental Crime: The Nature and Control of Environmental Black Markets; The Royal Institute of International Affairs: London, UK, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Adams, W.M.; Aveling, R.; Brockington, D.; Dickson, B.; Elliott, J.; Hutton, J.; Roe, D.; Vira, B.; Wolmer, W. Biodiversity conservation and the eradication of poverty. Science 2004, 306, 1146–1149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Borgerhoff-Mulder, M.; Coppolillo, P. Conservation: Linking Ecology, Economics, and Culture; Princeton University Press: Princeton, NJ, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Ostrom, E. Governing the Commons: The Evolution of Institutions for Collective Action; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Kaspal, P.; Shah, K.B.; Baral, H.S. Saalak (i.e., Pangolin); Himalayan Nature: Kathmandu, Nepal, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Sharma, S.; Sharma, H.P.; Katuwal, H.B.; Belant, J.L. Knowledge of the Critically Endangered Chinese pangolin (Manis pentadactyla) by local people in Sindhupalchok, Nepal. Glob. Ecol. Conserv. 2020, e01052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DNPWC. Protected Areas of Nepal; Department of National Parks and Wildlife Conservation: Kathmandu, Nepal, 2012.

- Bhattachan, K.B. Country Technical Notes on Indigenous Peoples’ Issues Federal Democratic Republic of Nepal; International Fund for Agricultural Development: Rome, Italy, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- CBS. National Population and Household Census 2011; National report submitted to Government of Nepal; National Planning Commission Secretariat, Central Bureau of Statistics: Kathmandu, Nepal, 2012.

- NRCA. Initial Environmental Examination of Deitar-Phulasipokhari Section of Devitar-Doramba-Paseban-Kolibagar Road Rehabilitation Sub-Project; Ramechhap district. A report prepared by District Coordination Committee, Ramechhap and submitted to Government of Nepal, National Reconstruction Authority through Government of Nepal; Ministry of Federal Affairs and Local Development Earthquake Emergency Assistance Project: Ramechhap, Nepal, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Yamane, T. Statistics: An Introductory Analysis, 2nd ed.; Harper and Row: New York, NY, USA, 1967. [Google Scholar]

- MacNamara, J.; Rowcliffe, M.; Cowlishaw, G.; Alexander, J.S.; Ntiamoa-Baidu, Y.; Brenya, A.; Milner-Gulland, E.J. Characterising wildlife trade market supply-demand dynamics. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0162962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Bennett, L.; Dahal, D.R.; Govindasamy, P. Caste, Ethnic and Regional Identity in Nepal: Further Analysis of the 2006 Nepal Demographic and Health Survey; Macro International Inc: Calverton, MD, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Loibooki, M.; Hofer, H.; Campbell, K.L.I.; East, M.L. Bushmeat hunting by communities adjacent to the Serengeti National Park, Tanzania: The importance of livestock ownership and alternatie sources of protein and income. Environ. Conserv. 2002, 29, 391–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghimire, P.; Raut, N.; Khanal, P.; Acharya, S.; Upadhaya, S. Species in peril: Assessing the status of the trade in pangolins in Nepal. J. Threat. Taxa. 2020, 12, 15776–15783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacKenzie, C.; Chapman, C.A.; Sengupta, R. Spatial patterns of illegal resource extraction in Kibale National Park, Uganda. Env. Conserv. 2011, 39, 38–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Nellemann, C.; Henricksen, R.; Raxter, P.; Ash, N.; Mrema, E. (Eds.) The Environmental Crime Crisis-Threats to Sustainable Development from Illegal Exploitation and Trade in Wildlife and Forest Resources; A UNEP Rapid Response Assessment; UN Environment Programme and GRID-Arendal: Nairobi, Kenya; Arendal, Norway, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Katuwal, H.B.; Parajuli, K.; Sharma, S. Money overweighed the traditional beliefs for hunting of Chinese pangolins in Nepal. J. Biodivers. Endanger. Species 2016, 4, 173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Twinamatsiko, M.; Baker, J.; Harrison, M.; Shirkhorshidi, M.; Bitariho, R.; Wieland, M.; Asuma, S.; Milner-Gulland, E.J.; Franks, P.; Roe, D. Linking Conservation, Equity and Poverty Alleviation: Understanding Profiles and Motivations of Resource Users and Local Perceptions of Governance at Bwindi Impenetrable National Park, Uganda; IIED Resources Report: London, UK, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, M.; Gouveia, A.; Qin, T.; Quan, R.; Nijman, V. Illegal pangolin trade in Northernmost Myanmar and its links to India and China. Glob. Ecol. Conserv. 2017, 10, 23–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Challender, D.W.S.; Harrop, S.R.; MacMillan, D.C. Understanding markets to conserve trade-threatened species in CITES. Biol. Conserv. 2015, 187, 249–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Lindsey, P.; Balme, G.; Becker, M.; Begg, C.; Bento, C.; Bocchino, C.; Dickman, A.; Diggel, R.; Eves, H.; Henschel, P.; et al. Illegal Hunting and the Bush-Meat Trade in Savanna Africa: Drivers, Impacts and Solutions to Address the Problem; Panthera/Zoological Society of London/Wildlife Conservation Society report: New York, NY, USA, 2015; Available online: http//www.fao.org/3/a-bc609e.pdf (accessed on 21 November 2019).

- Pangau-Adam, M.; Noske, R.A. Wildlife hunting and bird trade in north-east Papua (Irian Jaya), Indonesia. In Ethno-Ornithology: Birds, Indigenous Peoples, Culture and Society; Tidemann, S., Gosler, A., Gosford, R., Eds.; Earthscan: London, UK, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Paudel, K.; Potter, G.R.; Phelps, J. Conservation enforcement: Insights from people incarcerated for wildlife crimes in Nepal. Conserv. Sci. Prac. 2020, 2, e137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Davis, E.O. Understanding Use of Bear Products in Southeast Asia: Human-Oriented Perspectives from Cambodia and Laos. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Bristol, Bristol, UK, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Agarwal, B. Participatory exclusions, community forestry, and gender: An analysis for South Asia and a conceptual framework. World Dev. 2001, 29, 1623–1648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pokharel, S. Gender discriminatory practices in Tamang and Brahmin communities. Tribhuvan Univ. J. 2009, 26, 85–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McElwee, P. The Gender Dimensions of the illegal trade in wildlife: Local and global connections in Vietnam. In Gender and Sustainability: Lessons from Asia and Latin America; Cruz-Torres, M.L., McElwee, P., Eds.; University of Arizona Press: Tucson, AZ, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Sharma, H.P.; Belant, J.L.; Shaner, P.J.L. Attitudes towards conservation of the Endangered red panda Ailurus fulgens in Nepal: A case study in protected and non-protected areas. Oryx 2019, 53, 542–547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, J. Tackilng southeast Asia’s Illegal wildlife trade. SYBIL 2005, 9, 191–208. [Google Scholar]

- Heinrich, S.; Wittmann, T.A.; Prowse, T.A.A.; Ross, J.V.; Delean, S.; Sepherd, C.R.; Cassey, P. Where did all the pangolins go? International CITES trade in pangolin species. Glob. Ecol. Conserv. 2016, 8, 241–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Dangol, B.R. Illegal wildlife trade in Nepal: A case study from Kathmandu Valley. Master’s Thesis, Norwegian University of Life Science, Faculty of Life Science, Oslow, Norway, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Shrestha, A.B.; Bajracharya, S.R.; Kargel, J.S.; Khanal, N.R. The Impact of Nepal’s 2015 Gorkha Earthquake-Induces Geohazards; ICIMOD: Kathmandu, Nepal, 2016. [Google Scholar]

| Variable | Protected Area | Non-Protected Area | Statistics |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sex | Female = 48.8% Male = 51.2% | Female = 49.7% Male = 50.3% | Fisher’s exact test, two-tailed, p = 0.83 |

| Age (years) | Median = 29 | Median = 28 | Kruskal–Wallis test, χ2 = 2.13, p = 0.14 |

| Occupation | Agriculture = 69.1% | Agriculture = 74.1% | Fisher’s exact test, two-tailed, p = 0.63 |

| Education | Literate = 86.9% Illiterate = 13.1% | Literate = 84.2% Illiterate = 15.8% | Fisher’s exact test, two-tailed, p = 0.31 |

| Religion | Hindu = 54.2% Buddhist = 42.3% Christian = 3.5% | Hindu = 56.1% Buddhist = 39.7% Christian = 4.2% | Fisher’s exact test, two-tailed, p = 0.56 (Christian excluded because of small sample sizes) |

| Family size | Median = 5 | Median = 5 | Kruskal–Wallis test, χ2 = 0.9, p = 0.34 |

| Overall income | 87.4% sufficient | 82.7% sufficient | χ2 = 0.5, p = 0.47 |

| Overall income from agriculture | 52.2% sufficient | 39.9% sufficient | χ2 = 6.5, p = 0.01 |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Sharma, S.; Sharma, H.P.; Katuwal, H.B.; Chaulagain, C.; Belant, J.L. People’s Knowledge of Illegal Chinese Pangolin Trade Routes in Central Nepal. Sustainability 2020, 12, 4900. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12124900

Sharma S, Sharma HP, Katuwal HB, Chaulagain C, Belant JL. People’s Knowledge of Illegal Chinese Pangolin Trade Routes in Central Nepal. Sustainability. 2020; 12(12):4900. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12124900

Chicago/Turabian StyleSharma, Sandhya, Hari Prasad Sharma, Hem Bahadur Katuwal, Chanda Chaulagain, and Jerrold L. Belant. 2020. "People’s Knowledge of Illegal Chinese Pangolin Trade Routes in Central Nepal" Sustainability 12, no. 12: 4900. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12124900