Science Mapping of the Global Knowledge Base on Microfinance: Influential Authors and Documents, 1989–2019

Abstract

1. Introduction

- RQ1:

- How is the global microfinance literature distributed by type and volume over time, and by geography?

- RQ2:

- Which authors have the most significant influence on global microfinance research, and what is the intellectual structure of the knowledge base?

- RQ3:

- Which publications have the most significant influence on global microfinance research?

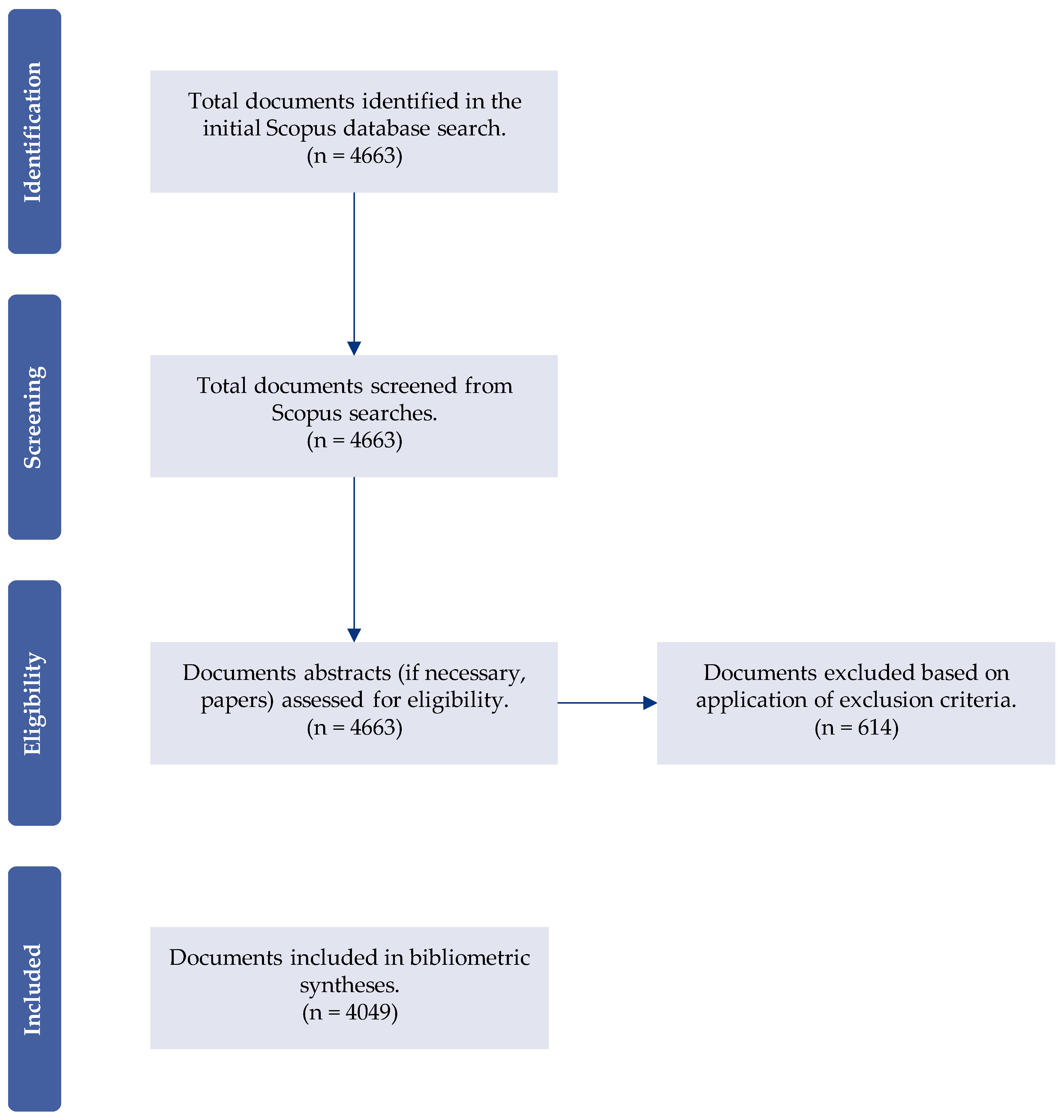

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Search Criteria and Identification of Sources

2.2. Data Extraction

2.3. Data Analysis

3. Results

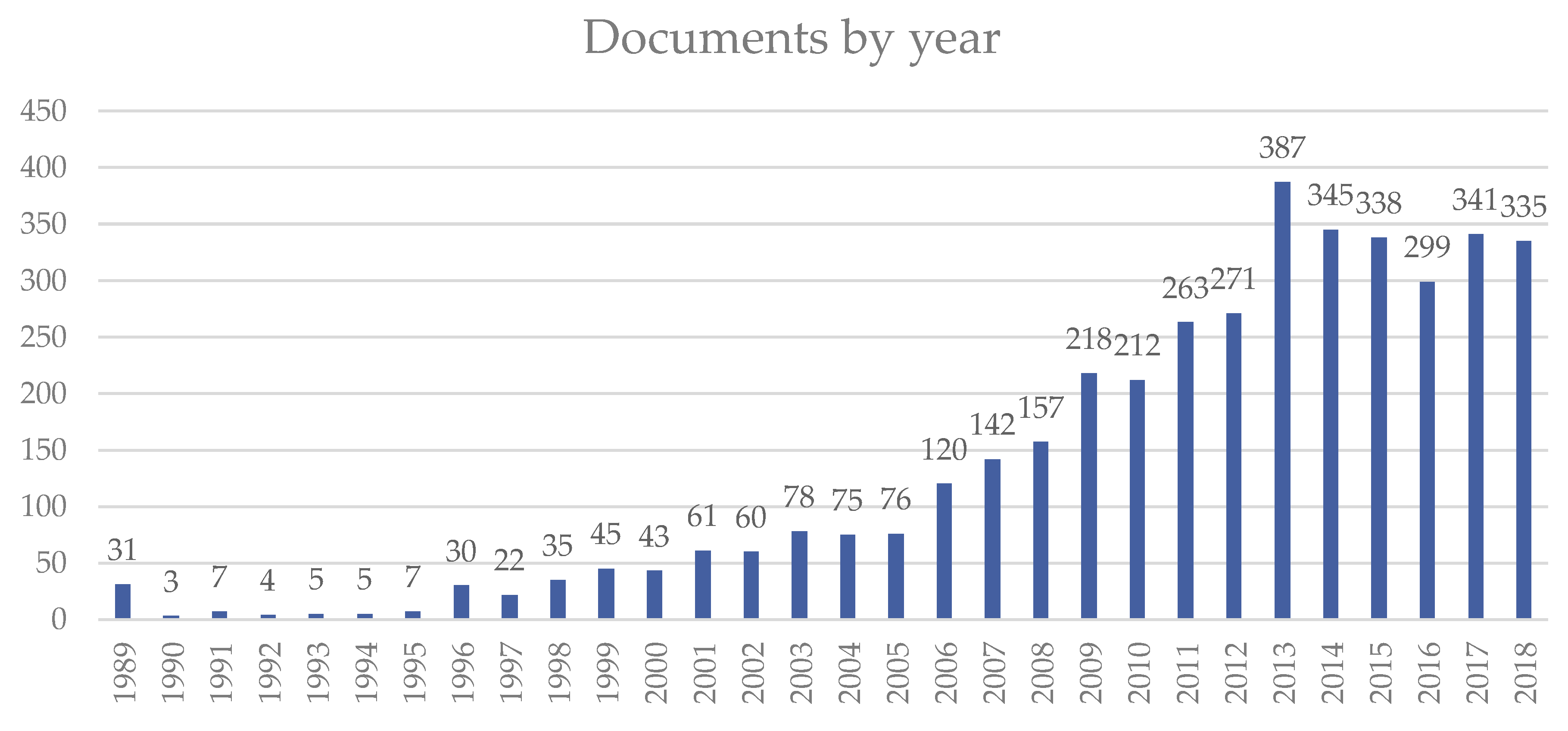

3.1. Distribution of Microfinance Literature by Type, Volume, Time, and Geography

3.2. Analysis of Influential Authors and Intellectual Structure of the Knowledge Base

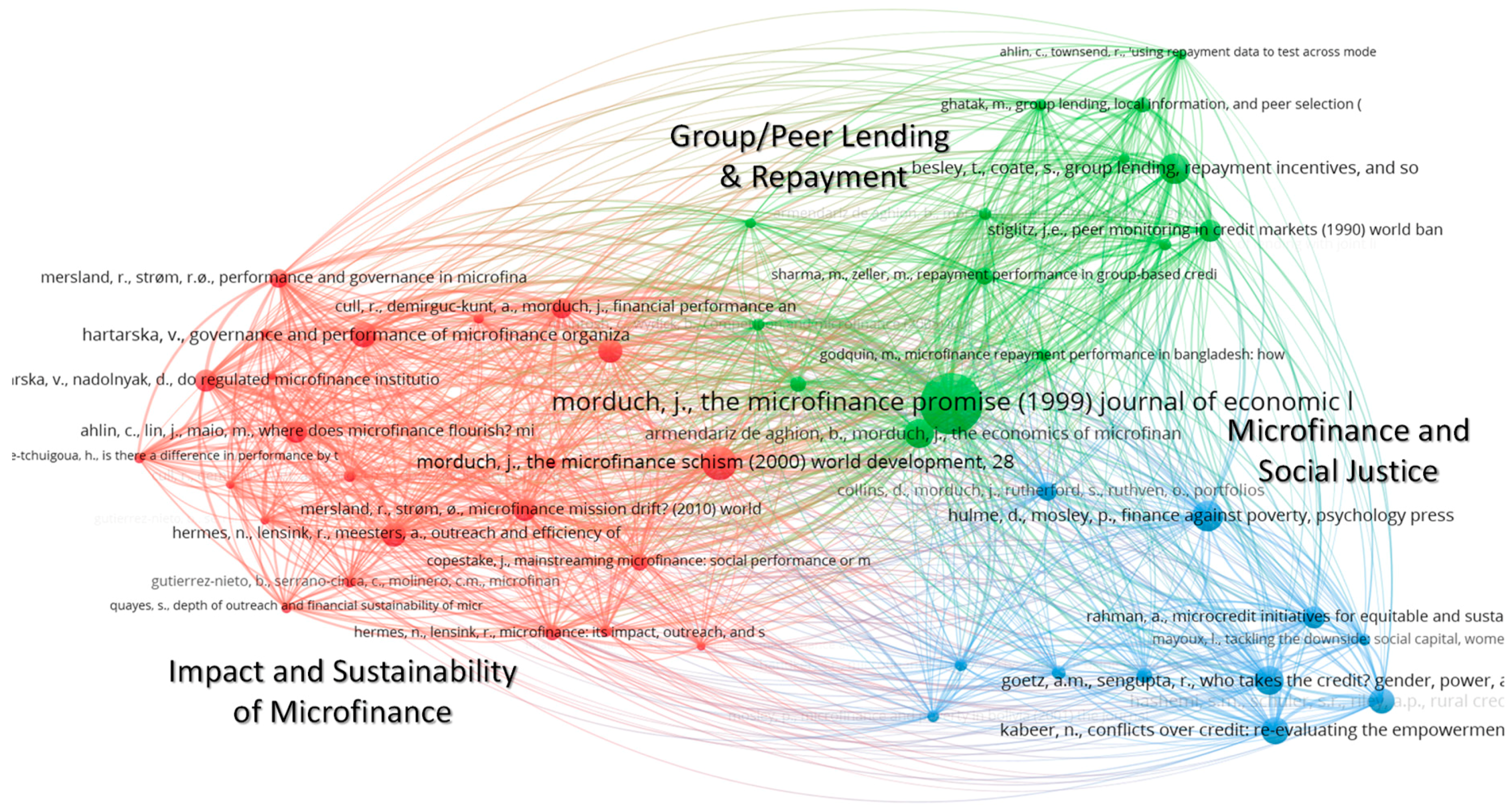

3.3. Analysis of Influential Documents

- Publications focusing on efficiency, outreach, performance, and sustainability of microfinance and MFIs (red cluster, ’Impact and Sustainability of Microfinance’)

- Research dealing with the repayment performance of group and peer lending (green cluster, ‘Group/Peer Lending and Repayment’)

- Documents on poverty alleviation, rural development, as well as equality, empowerment, and gender issues (blue cluster, ‘Microfinance and Social Justice’)

4. Discussion

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Mebratu, D. Sustainability and sustainable development: Historical and conceptual review. Environ. Impact Assess. Rev. 1998, 18, 493–520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Armendariz, B.; Morduch, J. The Economics of Microfinance, 2nd ed.; The MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Hudon, M. Should access to credit be a right? J. Bus. Ethics 2009, 84, 17–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robinson, M.S. The Microfinance Revolution: Sustainable Finance for the Poor; The World Bank: Washington, DC, USA, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Bharti, N.; Shylendra, H.S. Microfinance and sustainable micro entrepreneurship development. In Proceedings of the 7th Biennial Conference on Entrepreneurship, Entrepreneurship Development Institute of India, Gujarat, India, 21–23 March 2007. [Google Scholar]

- García-Pérez, I.; Muñoz-Torres, M.-J.; Fernández-Izquierdo, M.-Á. Microfinance literature: A sustainability level perspective survey. J. Clean. Prod. 2017, 142, 3382–3395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arbolino, R.; Carlucci, F.; Cirà, A.; Yigitcanlar, T.; Ioppolo, G. Mitigating regional disparities through microfinancing: An analysis of microcredit as a sustainability tool for territorial development in Italy. Land Use Policy 2018, 70, 281–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Pérez, I.; Muñoz-Torres, M.J.; Fernández-Izquierdo, M.Á. Microfinance institutions fostering sustainable development. Sustain. Dev. 2018, 26, 606–619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lopatta, K.; Tchikov, M.; Jaeschke, R.; Lodhia, S. Sustainable Development and Microfinance: The Effect of Outreach and Profitability on Microfinance Institutions’ Development Mission. Sustain. Dev. 2017, 25, 386–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohammed, E.Y.; Uraguchi, Z.B. Financial Inclusion for Poverty Alleviation: Issues and Case Studies for Sustainable Development; Sustainable Markets Group, International Institute for Environment and Development (IIED), Taylor and Francis: London, UK, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Ramaswamy, A.; Krishnamoorthy, A. The Nexus Between Microfinance Sustainable Development: Examining the Regulatory Changes Needed for Its Efficient Implementation. Eur. J. Sustain. Dev. 2016, 5, 453–460. [Google Scholar]

- Jimenez, L.E. Microfinance and housing for immigrants in the U.S.A.: A sustainable tool. Rev. INVI 2015, 30, 183–210. [Google Scholar]

- Manta, O. Countryside microfinance opportunity for sustainable rural development. In Proceedings of the 25th International Business Information Management Association Conference—Innovation Vision 2020: From Regional Development Sustainability to Global Economic Growth, IBIMA 2015, Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 7–8 May 2015; pp. 1446–1450. [Google Scholar]

- Mazumder, M.S.U. Role of Microfinance in Sustainable Development in Rural Bangladesh. Sustain. Dev. 2015, 23, 396–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Warnecke, T. “Greening” gender equity: Microfinance and the sustainable development agenda. J. Econ. Issues 2015, 49, 553–562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Senanayake, S.M.P.; Premaratne, S.P. Micro-finance for accelerated development. Sav. Dev. 2006, 30, 143–168. [Google Scholar]

- Pretty, J. Social Capital and the Collective Management of Resources. Science 2003, 302, 1912–1914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pretty, J.; Ward, H. Social capital and the environment. World Dev. 2001, 29, 209–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nugroho, L.; Utami, W.; Akbar, T.; Arafah, W. The challenges of microfinance institutions in empowering micro and small entrepreneur to implementating green activity. Int. J. Energy Econ. Policy 2017, 7, 66–73. [Google Scholar]

- Shammi, M.; Hasan, N.; Rahman, M.M.; Begum, K.; Sikder, M.T.; Bhuiyan, M.H.; Uddin, M.K. Sustainable pesticide governance in Bangladesh: Socio-economic and legal status interlinking environment, occupational health and food safety. Environ. Syst. Decis. 2017, 37, 243–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forcella, D.; Hudon, M. Green Microfinance in Europe. J. Bus. Ethics 2016, 135, 445–459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forcella, D.; Servet, J.-M. Finance as a Common: From Environmental Management to Microfinance and Back. Critical Studies on Corporate Responsibility, Governance and Sustainability; Centre for European Research in Microfinance, Emerald Group Publishing Ltd.: Brussels, Belgium, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Moser, R.M.B.; Gonzalez, L. Green microfinance: A new frontier to inclusive financial services. Rae Rev. De Adm. De Empresas 2016, 56, 242–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Archer, G.R.; Jones-Christensen, L. Entrepreneurial value creation through green microfinance: Evidence from Asian microfinance lending criteria. Asian Bus. Manag. 2011, 10, 331–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bastiaensen, J.; Huybrechs, F.; Forcella, D.; Van Hecken, G. Microfinance plus for ecosystem services: A territorial perspective on Proyecto CAMBio in Nicaragua. Enterp. Dev. Microfinance 2015, 26, 292–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonzalez, L.; Moser, R.M.B. Green microfinance: The case of the cresol system in Southern Brazil. Rev. De Adm. Publica 2015, 49, 1039–1058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Huybrechs, F.; Iaensen, J.B.; Forcella, D. Guest editorial: An introduction to the special issue on green microfinance. Enterp. Dev. Microfinance 2015, 26, 211–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahbouli, H.; Fortes, D. Is green microfinance “investment ready”? Perspective of an international impact investor. Enterp. Dev. Microfinance 2015, 26, 222–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moser, R.M.B.; Gonzalez, L. Microfinance and climate change impacts: The case of agroamigo in Brazil. Rae Rev. De Adm. De Empresas 2015, 55, 397–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahidullah, A.K.M.; Haque, C.E. Green microfinance strategy for entrepreneurial transformation: Validating a pattern towards sustainability. Enterp. Dev. Microfinance 2015, 26, 325–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hall, J.; Collins, L.; Israel, E.; Wenner, M. The Missing Bottom Line: Microfinance and the Environment; GreenMicrofinance: Philadelphia, PA, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Sachs, J.D. From millennium development goals to sustainable development goals. Lancet 2012, 379, 2206–2211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United Nations. Sustainable Development Goals; United Nations: New York, NY, USA; Available online: https://sustainabledevelopment.un.org/sdgs (accessed on 20 March 2019).

- United Nations Capital Development Fund. UNCDF and the SDG; United Nations Capital Development Fund: New York, NY, USA; Available online: https://www.uncdf.org/uncdf-and-the-sdgs (accessed on 20 March 2019).

- United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs. International Year of Microcredit 2005; United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs: New York, NY, USA; Available online: https://www.yearofmicrocredit.org/ (accessed on 20 March 2019).

- Dey, P.; Steyart, C. Tracing and theorizing ethics in entrepreneurship: Toward a critical hermeneutics of imagination. In The Routledge Companion to Ethics, Politics and Organizations; Pullen, A., Rhodes, C., Eds.; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2015; pp. 231–248. [Google Scholar]

- Mongeon, P.; Paul-Hus, A. The journal coverage of Web of Science and Scopus: A comparative analysis. Scientometrics 2016, 106, 213–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Falagas, M.E.; Pitsouni, E.I.; Malietzis, G.A.; Pappas, G. Comparison of PubMed, Scopus, Web of Science, and Google Scholar: Strengths and weaknesses. FASEB J. 2008, 22, 338–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gutierrez-Nieto, B.; Serrano-Cinca, C. 20 years of research in microfinance: An information management approach. Int. J. Inf. Manag. 2019, 47, 183–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- White, H.D.; McCain, K.W. Visualizing a discipline: An author co-citation analysis of information science, 1972-1995. J. Am. Soc. Inf. Sci. 1998, 49, 327–355. [Google Scholar]

- Zupic, I.; Čater, T. Bibliometric Methods in Management and Organization. Organ. Res. Methods 2015, 18, 429–472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Eck, N.J.; Waltman, L. Citation-based clustering of publications using CitNetExplorer and VOSviewer. Scientometrics 2017, 111, 1053–1070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hallinger, P. Science mapping the knowledge base on educational leadership and management from the emerging regions of Asia, Africa and Latin America, 1965–2018. Educ. Manag. Adm. Leadersh. 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hallinger, P.; Kovačević, J. A Bibliometric Review of Research on Educational Administration: Science Mapping the Literature, 1960 to 2018. Rev. Educ. Res. 2019, 89, 335–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hallinger, P.; Suriyankietkaew, S. Science Mapping of the Knowledge Base on Sustainable Leadership, 1990–2018. Sustainability 2018, 10, 4846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Small, H. Visualizing science by citation mapping. J. Am. Soc. Inf. Sci. 1999, 50, 799–813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCain, K.W. Mapping authors in intellectual space: A technical overview. J. Am. Soc. Inf. Sci. 1990, 41, 433–443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moher, D.; Liberati, A.; Tetzlaff, J.; Altman, D.G. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: The PRISMA statement. BMJ 2009, 339, 332–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Condosta, L. How banks are supporting local economies facing the current financial crisis: An Italian perspective. Int. J. Bank Mark. 2012, 30, 485–502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lerman, Z. Rural livelihoods in Tajikistan: What factors and policies influence the income and well-being of rural families? In Rangeland Stewardship in Central Asia: Balancing Improved Livelihoods, Biodiversity Conservation and Land Protection; Springer: Cham, The Netherlands, 2012; pp. 165–187. [Google Scholar]

- Pilkington, A.; Meredith, J. The evolution of the intellectual structure of operations management-1980-2006: A citation/co-citation analysis. J. Oper. Manag. 2009, 27, 185–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nerur, S.P.; Rasheed, A.A.; Natarajan, V. The intellectual structure of the strategic management field: An author co-citation analysis. Strateg. Manag. J. 2008, 29, 319–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berger, M. An introduction: Women’s ventures. In Women’s Ventures; Berger, M., Buvinic, M., Eds.; Kumarian Press Library of Management for Development: Sterling, VA, USA, 1989; pp. 1–18. [Google Scholar]

- Lycette, M.; White, K. Improving women’s access to credit in Latin America and the Caribbean: Policy and project recommendations. In Women’s Ventures; Kumarian Press Library of Management for Development: Sterling, VA, USA, 1989; pp. 19–44. [Google Scholar]

- Mezzera, J. Excess labor supply and urban informal sector: An analytical framework. In Women’s Ventures; Berger, M., Buvinic, M., Eds.; Kumarian Press Library of Management for Development: Sterling, VA, USA, 1989; pp. 45–64. [Google Scholar]

- Escobar, S. Small-scale commerce in the city of La Paz, Bolivia. In Women’s Ventures; Berger, M., Buvinic, M., Eds.; Kumarian Press Library of Management for Development: Sterling, VA, USA, 1989; pp. 65–82. [Google Scholar]

- Otero, M. Solidarity group programs: A working methodology for enhancing the economic activities of women in the informal sector. In Women’s Ventures; Berger, M., Buvinic, M., Eds.; Kumarian Press Library of Management for Development: Sterling, VA, USA, 1989; pp. 83–101. [Google Scholar]

- McKean, C.S. Training and technical assistance for small and microbusiness: A review of their effectiveness and implications for women. In Women’s Ventures; Berger, M., Buvinic, M., Eds.; Kumarian Press Library of Management for Development: Sterling, VA, USA, 1989; pp. 102–120. [Google Scholar]

- Placencia, M.M. Training and credit programs for microentrepreneurs: Some concerns about the training of women. In Women’s Ventures; Berger, M., Buvinic, M., Eds.; Kumarian Press Library of Management for Development: Sterling, VA, USA, 1989; pp. 121–131. [Google Scholar]

- Reichmann, R. Women’s participation in two PVO credit programs for microenterprise: Cases from the Dominican Republic and Peru. In Women’s Ventures; Berger, M., Buvinic, M., Eds.; Kumarian Press Library of Management for Development: Sterling, VA, USA, 1989; pp. 132–160. [Google Scholar]

- Abreu, L.M. The experience of MUDE Dominicana in operating a women-specific credit program. In Women’s Ventures; Berger, M., Buvinic, M., Eds.; Kumarian Press Library of Management for Development: Sterling, VA, USA, 1989; pp. 161–173. [Google Scholar]

- Women’s World Banking. The credit guarantee mechanisms for improving women’s access to bank loans. In Women’s Ventures; Berger, M., Buvinic, M., Eds.; Kumarian Press Library of Management for Development: Sterling, VA, USA, 1989; pp. 174–184. [Google Scholar]

- Guzman, M.M.; Castro, M.C. From a women’s guarantee fund to a bank for microenterprise: Process and results. In Women’s Ventures; Berger, M., Buvinic, M., Eds.; Kumarian Press Library of Management for Development: Sterling, VA, USA, 1989; pp. 185–200. [Google Scholar]

- Arias, M.E. The Rural Development Fund: An integrated credit program for small and medium entrepreneurs. In Women’s Ventures; Berger, M., Buvinic, M., Eds.; Kumarian Press Library of Management for Development: Sterling, VA, USA, 1989; pp. 201–213. [Google Scholar]

- Landivar, J.F. Credit and development for women: An introduction to the Ecuadorian Development Foundation. In Women’s Ventures; Berger, M., Buvinic, M., Eds.; Kumarian Press Library of Management for Development: Sterling, VA, USA, 1989; pp. 214–221. [Google Scholar]

- Buvinic, M.; Berger, M.; Jaramillo, C. Impact of a credit project for women and men microentrepreneurs in Quito, Ecuador. In Women’s Ventures; Berger, M., Buvinic, M., Eds.; Kumarian Press Library of Management for Development: Sterling, VA, USA, 1989; pp. 222–246. [Google Scholar]

- De Soto, H. Structural adjustment and the informal sector. In Microenterprises in Developing Countries, Proceedings of an International Conference Held in Washington, DC, USA, 6–9 June 1988; Intermediate Technology Publications: London, UK, 1989; pp. 3–12. [Google Scholar]

- Tokman, V.E. Micro-level support for the informal sector. In Microenterprises in Developing Countries, Proceedings of an International Conference Held in Washington, DC, USA, 6–9 June 1988; Intermediate Technology Publications: London, UK, 1989; pp. 13–25. [Google Scholar]

- Tendler, J. Whatever happened to poverty alleviation? In Microenterprises in Developing Countries, Proceedings of an International Conference Held in Washington, DC, USA, 6–9 June 1988; Intermediate Technology Publications: London, UK, 1989; pp. 26–56. [Google Scholar]

- Nowak, M. The role of microenterprises in rural industrialization in Africa. In Microenterprises in Developing Countries, Proceedings of an International Conference Held in Washington, DC, USA, 6–9 June 1988; Intermediate Technology Publications: London, UK, 1989; pp. 57–75. [Google Scholar]

- Chandavarkar, A.G. Informal credit markets in support of microbusiness. In Microenterprises in Developing Countries, Proceedings of an International Conference Held in Washington, DC, USA, 6–9 June 1988; Intermediate Technology Publications: London, UK, 1989; pp. 79–96. [Google Scholar]

- Seibel, H.D. Linking informal and formal financial institutions in Africa and Asia. In Microenterprises in Developing Countries, and Proceedings of an International Conference Held in Washington, DC, USA, 6–9 June 1988; Intermediate Technology Publications: London, UK, 1989; pp. 97–118. [Google Scholar]

- Meyer, R.L. Financial services for microenterprises: Programmes or markets? In Microenterprises in Developing Countries, and Proceedings of an International Conference Held in Washington, DC, USA, 6–9 June 1988; Intermediate Technology Publications: London, UK, 1989; pp. 121–130. [Google Scholar]

- Jackelen, H.R. Banking on the informal sector. In Microenterprises in Developing Countries, Proceedings of an International Conference Held in Washington, DC, USA, 6–9 June 1988; Intermediate Technology Publications: London, UK, 1989; pp. 131–143. [Google Scholar]

- Yunus, M. Grameen Bank: Organization and operation. In Microenterprises in Developing Countries, Proceedings of an International Conference Held in Washington, DC, USA, 6–9 June 1988; Intermediate Technology Publications: London, UK, 1989; pp. 144–161. [Google Scholar]

- Carr, M. Institutional aspects of microenterprise promotion. In Microenterprises in Developing Countries, Proceedings of an International Conference Held in Washington, DC, USA, 6–9 June 1988; Intermediate Technology Publications: London, UK, 1989; pp. 165–176. [Google Scholar]

- Harper, M. Training and technical assistance for microenterprises. In Microenterprises in Developing Countries, Proceedings of an International Conference Held in Washington, DC, USA, 6–9 June 1988; Intermediate Technology Publications: London, UK, 1989; pp. 177–188. [Google Scholar]

- Gamser, M.; Almond, F. The role of technology in microenterprise development. In Microenterprises in Developing Countries, Proceedings of an International Conference Held in Washington, DC, USA, 6–9 June 1988; Intermediate Technology Publications: London, UK, 1989; pp. 189–201. [Google Scholar]

- Carvajal, J. Microenterprise as a social investment. In Microenterprises in Developing Countries, Proceedings of an International Conference Held in Washington, DC, USA, 6–9 June 1988; Intermediate Technology Publications: London, UK, 1989; pp. 202–207. [Google Scholar]

- Otero, M. Benefits, costs and sustainability of microenterprise assistance programmes. In Microenterprises in Developing Countries, Proceedings of an International Conference Held in Washington, DC, USA, 6–9 June 1988; Intermediate Technology Publications: London, UK, 1989; pp. 211–223. [Google Scholar]

- Timberg, T.A. Comparative experience with microenterprise projects. In Microenterprises in Developing Countries, Proceedings of an International Conference Held in Washington, DC, USA, 6–9 June 1988; Intermediate Technology Publications: London, UK, 1989; pp. 224–239. [Google Scholar]

- Okelo, M.E. Support for women in microenterprises in Africa. In Microenterprises in Developing Countries, Proceedings of an International Conference Held in Washington, DC, USA, 6–9 June 1988; Intermediate Technology Publications: London, UK, 1989; pp. 240–250. [Google Scholar]

- Mosley, P.; Hulme, D. The story of the Grameen Bank: From subsidized microcredit to market based microfinance. In Microfinance; Arun, T., Hulme, D., Eds.; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- The Nobel Foundation. The Nobel Peace Prize for 2006; The Nobel Foundation: Stockholm, Sweden; Available online: https://www.nobelprize.org/prizes/peace/2006/press-release/ (accessed on 20 March 2019).

- Cull, R.; Demirguc-Kunt, A.; Morduch, J. Banks and Microbanks. J. Financ. Serv. Res. 2014, 46, 1–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morduch, J. The microfinance schism. World Dev. 2000, 28, 617–629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cull, R.; Demirguc-Kunt, A.; Morduch, J. Financial performance and outreach: A global analysis of leading microbanks. Econ. J. 2007, 117, F107–F133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Golesorkhi, S.; Mersland, R.; Piekkari, R.; Pishchulov, G.; Randøy, T. The effect of language use on the financial performance of microfinance banks: Evidence from cross-border activities in 74 countries. J. World Bus. 2019, 54, 213–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lensink, R.; Mersland, R.; Vu, N.T.H.; Zamore, S. Do microfinance institutions benefit from integrating financial and nonfinancial services? Appl. Econ. 2018, 50, 2386–2401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mersland, R.; Oystein Strom, R. Performance and governance in microfinance institutions. J. Bank. Financ. 2009, 33, 662–669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hartarska, V. Governance and performance of microfinance institutions in Central and Eastern Europe and the Newly Independent States. World Dev. 2005, 33, 1627–1643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hartarska, V.; Nadolnyak, D. Do regulated microfinance institutions achieve better sustainability and outreach? Cross-country evidence. Appl. Econ. 2007, 39, 1207–1222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hermes, N.; Lensink, R. The empirics of microfinance: What do we know? Econ. J. 2007, 117, F1–F10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hermes, N.; Lensink, R. Microfinance: Its Impact, Outreach, and Sustainability. World Dev. 2011, 39, 875–881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hermes, N.; Lensink, R.; Meesters, A. Outreach and Efficiency of Microfinance Institutions. World Dev. 2011, 39, 938–948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hulme, D.; Shepherd, A. Conceptualizing chronic poverty. World Dev. 2003, 31, 403–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mosley, P.; Hulme, D. Microenterprise finance: Is there a conflict between growth and poverty alleviation? World Dev. 1998, 26, 783–790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khandker, S.R. Microfinance and poverty: Evidence using panel data from Bangladesh. World Bank Econ. Rev. 2005, 19, 263–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khandker, S.R. Fighting Poverty with Microcredit: Experience in Bangladesh; Oxford University Press, for the World Bank: Oxford, UK, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Hulme, D.; Mosley, P. Finance against Poverty. Volume 1–2; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Matin, I.; Hulme, D.; Rutherford, S. Finance for the poor: From microcredit to microfinancial services. J. Int. Dev. 2002, 14, 273–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collins, D.; Morduch, J.; Rutherford, S.; Ruthven, O. Portfolios of the Poor: How the World’s Poor Live on $2 a Day; Princeton University Press: Princeton, NJ, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Karlan, D.S. Using experimental economics to measure social capital and predict financial decisions. Am. Econ. Rev. 2005, 95, 1688–1699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karlan, D.; Zinman, J. Microcredit in theory and practice: Using randomized credit scoring for impact evaluation. Science 2011, 332, 1278–1284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jan, S.; Ferrari, G.; Watts, C.H.; Hargreaves, J.R.; Kim, J.C.; Phetla, G.; Morison, L.A.; Porter, J.D.; Barnett, T.; Pronyk, P.M. Economic evaluation of a combined microfinance and gender training intervention for the prevention of intimate partner violence in rural South Africa. Health Policy Plan. 2011, 26, 366–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pronyk, P.M.; Hargreaves, J.R.; Kim, J.C.; Morison, L.A.; Phetla, G.; Watts, C.; Busza, J.; Porter, J.D. Effect of a structural intervention for the prevention of intimate-partner violence and HIV in rural South Africa: A cluster randomised trial. Lancet 2006, 368, 1973–1983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pronyk, P.M.; Kim, J.C.; Abramsky, T.; Phetla, G.; Hargreaves, J.R.; Morison, L.A.; Watts, C.; Busza, J.; Porter, J.D. A combined microfinance and training intervention can reduce HIV risk behaviour in young female participants. AIDS 2008, 22, 1659–1665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hargreaves, J.; Hatcher, A.; Strange, V.; Phetla, G.; Busza, J.; Kim, J.; Watts, C.; Morison, L.; Porter, J.; Pronyk, P.; et al. Process evaluation of the Intervention with Microfinance for AIDS and Gender Equity (IMAGE) in rural South Africa. Health Educ. Res. 2010, 25, 27–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, J.C.; Watts, C.H.; Hargreaves, J.R.; Ndhlovu, L.X.; Phetla, G.; Morison, L.A.; Busza, J.; Porter, J.D.H.; Pronyk, P. Understanding the impact of a microfinance-based intervention on women’s empowerment and the reduction of intimate partner violence in South Africa. Am. J. Public Health 2007, 97, 1794–1802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pronyk, P.M.; Kim, J.C.; Hargreaves, J.R.; Makhubele, M.B.; Morison, L.A.; Watts, C.; Porter, J.D.H. Microfinance and HIV prevention - Emerging lessons from rural South Africa. Small Enterp. Dev. 2005, 16, 26–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rankin, K.N. Social capital, microfinance, and the politics of development. Fem. Econ. 2002, 8, 1–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rankin, K.N. Governing development: Neoliberalism, microcredit, and rational economic woman. Econ. Soc. 2001, 30, 18–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The World Bank. Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) and the 2030 Agenda; The World Bank: Washington, DC, USA; Available online: http://www.worldbank.org/en/programs/sdgs-2030-agenda (accessed on 14 May 2019).

- Stiglitz, J.E. Peer monitoring and credit markets. World Bank Econ. Rev. 1990, 4, 351–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morduch, J. The microfinance promise. J. Econ. Lit. 1999, 37, 1569–1614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pitt, M.M.; Khandker, S.R. The Impact of Group-Based Credit Programs on Poor Households in Bangladesh: Does the Gender of Participants Matter? J. Political Econ. 1998, 106, 958–996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karlan, D.; Zinman, J. Expanding credit access: Using randomized supply decisions to estimate the impacts. Rev. Financ. Stud. 2010, 23, 433–464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mersland, R.; Oystein Strom, R.O. Microfinance Mission Drift? World Dev. 2010, 38, 28–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cull, R.; Demirguc-Kunt, A.; Morduch, J. Microfinance meets the market. J. Econ. Perspect. 2009, 23, 167–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cull, R.; Demirguc-Kunt, A.; Morduch, J. Does Regulatory Supervision Curtail Microfinance Profitability and Outreach? World Dev. 2011, 39, 949–965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Armendariz, B.; Szafarz, A. On mission drift in microfinance institutions. In The Handbook of Microfinance; World Scientific Publishing Co.: London, UK, 2011; pp. 341–366. [Google Scholar]

- Schreiner, M.; Woller, G. Microenterprise development programs in the United States and in the developing world. World Dev. 2003, 31, 1567–1580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schreiner, M. A cost-effectiveness analysis of the Grameen bank of Bangladesh. Dev. Policy Rev. 2003, 21, 357–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banerjee, A.; Chandrasekhar, A.G.; Duflo, E.; Jackson, M.O. The diffusion of microfinance. Science 2013, 341, 1236498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Banerjee, A.V.; Besley, T.; Guinnane, T.W. Thy neighbor’s keeper: The design of a credit cooperative with theory and a test. Q. J. Econ. 1994, 109, 491–515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banerjee, A.; Duflo, E.; Glennerster, R.; Kinnan, C. The miracle of microfinance? Evidence from a randomized evaluation. Am. Econ. J. Appl. Econ. 2015, 7, 22–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hashemi, S.M.; Schuler, S.R.; Riley, A.P. Rural Credit Programs and Women’s Empowerment in Bangladesh. World Dev. 1996, 24, 635–653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schuler, S.R.; Hashemi, S.M. Credit programs, women’s empowerment, and contraceptive use in rural Bangladesh. Stud. Fam. Plan. 1994, 25, 65–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yunus, M.; Moingeon, B.; Lehmann-Ortega, L. Building social business models: Lessons from the Grameen experience. Long Range Plan. 2010, 43, 308–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yunus, M. Credit for the poor: Poverty as distant history. Harv. Int. Rev. 2007, 29, 20–24. [Google Scholar]

- Pitt, M.M.; Khandker, S.R.; Cartwright, J. Empowering women with micro finance: Evidence from Bangladesh. Econ. Dev. Cult. Chang. 2006, 54, 791–831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kabeer, N. Assessing the “Wider” Social impacts of microfinance services: Concepts, methods, findings. Ids Bull. 2003, 34, 106–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Kabeer, N. Conflicts over credit: Re-evaluating the empowerment potential of loans to women in rural Bangladesh. World Dev. 2001, 29, 63–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schuler, S.R.; Hashemi, S.M.; Badal, S.H. Men’s violence against women in rural Bangladesh: Undermined or exacerbated by microcredit programmes? Dev. Pract. 1998, 8, 148–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schuler, S.R.; Hashemi, S.M.; Riley, A.P. The influence of women’s changing roles and status in Bangladesh’s fertility transition: Evidence from a study of credit programs and contraceptive use. World Dev. 1997, 25, 563–575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Navajas, S.; Schreiner, M.; Meyer, R.L.; Gonzalez-Vega, C.; Rodriguez-Meza, J. Microcredit and the poorest of the poor: Theory and evidence from Bolivia. World Dev. 2000, 28, 333–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schreiner, M. Aspects of outreach: A framework for discussion of the social benefits of microfinance. J. Int. Dev. 2002, 14, 591–603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caudill, S.B.; Gropper, D.M.; Hartarska, V. Which microfinance institutions are becoming more cost effective with time? Evidence from a mixture model. Pers. Psychol. 2009, 62, 651–672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banerjee, A.; Karlan, D.; Zinman, J. Six randomized evaluations of microcredit: Introduction and further steps. Am. Econ. J. Appl. Econ. 2015, 7, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patel, V.; Kleinman, A. Poverty and common mental disorders in developing countries. Bull. World Health Organ. 2003, 81, 609–615. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Battilana, J.; Dorado, S. Building sustainable hybrid organizations: The case of commercial microfinance organizations. Acad. Manag. J. 2010, 53, 1419–1440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vertovec, S. Migrant transnationalism and modes of transformation. Int. Migr. Rev. 2004, 38, 970–1001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pretty, J.; Toulmin, C.; Williams, S. Sustainable intensification in African agriculture. Int. J. Agric. Sustain. 2011, 9, 5–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahman, A. Micro-credit initiatives for equitable and sustainable development: Who pays? World Dev. 1999, 27, 67–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Besley, T.; Coate, S. Who takes the credit? Gender, power, and control over loan use in rural credit programs in Bangladesh. J. Dev. Econ. 1995, 46, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goetz, A.-M.; Sen Gupta, R. Who takes the credit? Gender, power, and control over loan use in rural credit programs in Bangladesh. World Dev. 1996, 24, 45–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahlin, C.; Lin, J.; Maio, M. Where does microfinance flourish? Microfinance institution performance in macroeconomic context. J. Dev. Econ. 2011, 95, 105–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, M.; Zeller, M. Repayment performance in group-based credit programs in Bangladesh: An empirical analysis. World Dev. 1997, 25, 1731–1742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yunus, M.; Sibieude, T.; Lesueur, E. Social business and big business: Innovative, promising solutions to overcome poverty? Field Actions Sci. Rep. 2012, 4, 68–74. [Google Scholar]

- Yunus, M. The Story of Micro-credit: Grameen Bank and Social Business. In Democracy, Sustainable Development, and Peace: New Perspectives on South Asia; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Yunus, M.; Zeitinger, C.-P. Money matters. In Uberpreneurs: How to Create Innovative Global Businesses and Transform Human Societies; Palgrave Macmillan: Basingstoke, UK, 2013; pp. 217–231. [Google Scholar]

- Yunus, M. Alleviating poverty through technology. Science 1998, 282, 409–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yunus, M.; Dalsace, F.; Menascé, D.; Faivre-Tavignot, B. Reaching the rich world’s poorest consumers. Harv. Bus. Rev. 2015, 93, 12. [Google Scholar]

- Yunus, M. Halving poverty by 2015-we can actually make it happen. Round Table 2003, 92, 363–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Rank | Author | Topical Focus | Country | Docs | Scopus Citations | CPD1 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Morduch J. | Institutional | US2 | 27 | 2999 | 111 |

| 2 | Phetla G. | Health | SA3 | 7 | 1130 | 161 |

| 3 | Busza J. | Health | UK4 | 6 | 1103 | 184 |

| 4 | Hargreaves J. R. | Health | UK | 7 | 1094 | 156 |

| 5 | Kim J. C. | Health | US | 6 | 1051 | 175 |

| 6 | Morison L. A. | Health | UK | 6 | 1051 | 175 |

| 7 | Hulme D. | Poverty in General | UK | 17 | 1008 | 59 |

| 8 | Mersland R. | Institutional | NO5 | 44 | 964 | 22 |

| 9 | Watts C. | Health | UK | 7 | 872 | 125 |

| 10 | Khandker S. R. | Poverty in General | US | 13 | 854 | 66 |

| 11 | Mosley P. | Poverty in General | UK | 18 | 844 | 47 |

| 12 | Pronyk P. M. | Health | US | 6 | 835 | 139 |

| 13 | Karlan D. | Impact | US | 20 | 822 | 41 |

| 14 | Cull R. | Institutional | US | 12 | 729 | 61 |

| 15 | Demirguc-Kunt A. | Institutional | US | 6 | 691 | 115 |

| 16 | Hartarska V. | Institutional | US | 20 | 626 | 31 |

| 17 | Rankin K. N. | Women’s Empowerment | CA6 | 8 | 623 | 78 |

| 18 | Rutherford S. | Poverty in General | UK | 7 | 615 | 88 |

| 19 | Lensink R. | Institutional | NL7 | 21 | 611 | 29 |

| 20 | Hermes N. | Institutional | NL | 15 | 542 | 36 |

| Rank | Author | School of Thought (Cluster in Figure 4) | Co-Citations | Total Link Strength |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | *Morduch J. | Institutional Aspects | 3269 | 86,004 |

| 2 | *Khandker S. R. | Social Justice | 1352 | 32,118 |

| 3 | *Karlan D. | Impact and Sustainability | 1182 | 36,521 |

| 4 | *Mersland R. | Institutional Aspects | 1154 | 31,651 |

| 5 | *Demirguc-Kunt A. | Institutional Aspects | 1017 | 31,508 |

| 6 | *Hulme D. | Social Justice | 1000 | 22,655 |

| 7 | Armendariz B. | Institutional Aspects | 842 | 24,080 |

| 8 | Banerjee A. | Impact and Sustainability | 783 | 23,298 |

| 9 | *Mosley P. | Social Justice | 770 | 17,730 |

| 10 | *Cull R. | Institutional Aspects | 755 | 24,345 |

| 11 | Hashemi S. | Social Justice | 723 | 15,742 |

| 12 | Yunus M. | Social Justice | 723 | 14,484 |

| 13 | Duflo E. | Impact and Sustainability | 696 | 19,627 |

| 14 | Stiglitz J. | Impact and Sustainability | 695 | 18,855 |

| 15 | *Lensink R. | Institutional Aspects | 685 | 20,474 |

| 16 | Pitt M. | Social Justice | 654 | 17,071 |

| 17 | *Hartarska V. | Institutional Aspects | 608 | 16,723 |

| 18 | Kabeer N. | Social Justice | 589 | 12,422 |

| 19 | Schreiner M. | Institutional Aspects | 579 | 13,088 |

| 20 | *Hermes N. | Institutional Aspects | 563 | 16,510 |

| Author(s) | Document | Scopus Citations | CPD1 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Morduch (2000) | The microfinance schism [86] | 333 | 18 |

| Cull et al. (2007) | Financial performance and outreach [87] | 332 | 28 |

| Cull et al. (2009) | Microfinance meets the market [119] | 244 | 24 |

| Hermes et al. (2011) | Outreach and efficiency of microfinance institutions [95] | 192 | 24 |

| Mersland and Strom (2009) | Performance and governance in microfinance institutions [90] | 185 | 19 |

| Hartarska (2005) | Governance and performance of microfinance institutions in Central and Eastern Europe… [91] | 154 | 11 |

| Hartarska and Nadolnyak (2007) | Do regulated microfinance institutions achieve better sustainability and outreach? Cross-country evidence [92] | 151 | 13 |

| Navajas et al. (2000) | Microcredit and the poorest of the poor: Theory and evidence from Bolivia [136] | 143 | 8 |

| Hermes and Lensink (2007) | The empirics of microfinance: What do we know? [93] | 130 | 11 |

| Schreiner (2002) | Aspects of outreach: A framework for discussion of the social benefits of microfinance [137] | 114 | 7 |

| Hermes and Lensink (2011) | Microfinance: Its impact, outreach, and sustainability [94] | 105 | 13 |

| Cull et al. (2011) | Does regulatory supervision curtail microfinance profitability and outreach? [120] | 90 | 11 |

| Caudill et al. (2009) | Which microfinance institutions are becoming more cost effective with time? [138] | 73 | 7 |

| Armendariz and Szafarz (2011) | On mission drift in microfinance institutions [121] | 67 | 8 |

| Author(s) | Document | Scopus Citations | CPD1 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Stiglitz (1990) | Peer monitoring and credit markets [114] | 484 | 17 |

| Banerjee et al. (2013) | The diffusion of microfinance [124] | 206 | 34 |

| Banerjee et al. (1994) | Thy neighbor’s keeper: The design of a credit cooperative with theory and a test [125] | 195 | 8 |

| Karlan (2005) | Using experimental economics to measure social capital and predict financial decisions [103] | 184 | 13 |

| Karlan and Zinman (2010) | Expanding credit access: Using randomized supply decisions to estimate the impacts [117] | 167 | 19 |

| Banerjee et al. (2015) | The miracle of microfinance? Evidence from a randomized evaluation [126] | 155 | 39 |

| Banerjee et al. (2015) | Six randomized evaluations of microcredit: Introduction and further steps [139] | 124 | 31 |

| Karlan and Zinman (2011) | Microcredit in theory and practice: Using randomized credit scoring for impact evaluation [104] | 116 | 15 |

| Author(s) | Document | Scopus Citations | CPD1 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Pitt and Khandker (1998) | The impact of group-based credit programs on poor households in Bangladesh: Does gender matter? [116] | 539 | 26 |

| Hashemi et al. (1996) | Rural credit programs and women’s empowerment in Bangladesh [127] | 467 | 20 |

| Kabeer (2001) | Conflicts over credit: Re-evaluating the empowerment potential of loans to women in rural Bangladesh [133] | 388 | 22 |

| Yunus et al. (2010) | Building social business models [129] | 356 | 40 |

| Khandker (2005) | Microfinance and poverty [98] | 339 | 24 |

| Hulme and Shepherd (2003) | Conceptualizing chronic poverty [96] | 305 | 19 |

| Khandker (1998) | Fighting poverty with microcredit [99] | 247 | 12 |

| Schuler and Hashemi (1994) | Credit programs, women’s empowerment, and contraceptive use in rural Bangladesh [128] | 198 | 8 |

| Schuler et al. (1998) | Men’s violence against women in rural Bangladesh [134] | 137 | 7 |

| Pitt et al. (2006) | Empowering women with micro finance [131] | 127 | 10 |

| Mosley and Hulme (1998) | Microenterprise finance: is there a conflict between growth and poverty alleviation? [97] | 126 | 6 |

| Schuler et al. (1997) | The influence of women’s changing roles and status in Bangladesh’s fertility transition [135] | 110 | 5 |

| Matin et al. (1997) | Finance for the poor [101] | 72 | 4 |

| Rank | Document | Topical Focus | Type 1 of Paper | Scopus Citations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Morduch (1999). The microfinance promise. [115] | Comprehensive | Con | 795 |

| 2 | Pretty and Ward (2001). Social capital and the environment. [18] | Environment | Con | 761 |

| 3 | Pretty (2003). Social Capital and the Collective Management of Resources. [17] | Environment | Con | 731 |

| 4 | Battilana and Dorado (2010). Building sustainable hybrid organizations. [141] | MFIs | Con | 699 |

| 5 | Patel and Kleinman (2003). Poverty and common mental disorders in developing countries. [140] | Health | Rev | 542 |

| 6 | Pitt and Khandker (1998). The Impact of Group-Based Credit Programs on Poor Households in Bangladesh. [116] | Poverty in General | Emp | 540 |

| 7 | Collins et al. (2009). Portfolios of the poor: How the world’s poor live on $2 a day. [102] | Poverty in General | Emp | 501 |

| 8 | Pronyk et al. (2006). Effect of a structural intervention for the prevention of intimate-partner violence and HIV in rural South Africa. [106] | Health | Emp | 489 |

| 9 | Hashemi et al. (1996). Rural Credit Programs and Women’s Empowerment in Bangladesh. [127] | Women’s Empowerment | Emp | 467 |

| 10 | Kabeer (2001). Conflicts over credit: Re-evaluating the empowerment potential of loans to women in rural Bangladesh. [133] | Women’s Empowerment | Emp | 388 |

| 11 | Vertovec (2004). Migrant transnationalism and modes of transformation. [142] | Migration | Con | 379 |

| 12 | Pretty et al. (2011). Sustainable intensification in African agriculture. [143] | Environment | Emp | 377 |

| 13 | Hulme and Mosley (1996). Finance against poverty. [100] | Poverty in General | Con | 362 |

| 14 | Yunus et al. (2010). Building social business models: Lessons from the Grameen experience. [129] | Comprehensive/MFIs | Con | 356 |

| 15 | Khandker (2005). Microfinance and poverty. [98] | Poverty in General | Emp | 339 |

| 16 | Morduch (2000). The microfinance schism. [86] | MFIs | Con | 333 |

| 17 | Cull et al. (2007). Financial performance and outreach: A global analysis of leading microbanks. [87] | MFIs | Emp | 332 |

| 18 | Rahman (1999). Micro-credit initiatives for equitable and sustainable development: Who pays? [144] | MFIs | Emp | 317 |

| 19 | Hulme and Shepherd (2003). Conceptualizing chronic poverty. [96] | Poverty in General | Con | 305 |

| 20 | Rankin (2001). Governing development: Neoliberalism, microcredit, and rational economic woman. [112] | Women’s Empowerment | Con | 300 |

| Rank | Document | Cluster | Type1 | Co-Citations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | *Morduch (1999). The microfinance promise. [115] | Green | Con | 322 |

| 2 | *Morduch (2000). The microfinance schism. [86] | Red | Con | 158 |

| 3 | Besley and Coate (1995). Who takes the credit? Gender, power, and control over loan use in rural credit programs in Bangladesh. [145] | Green | Emp | 139 |

| 4 | *Hulme and Mosley (1996). Finance against poverty. [100] | Blue | Con | 133 |

| 5 | Armendariz and Morduch (2010). The economics of microfinance. [2] | Green | Con | 127 |

| 6 | Goetz and Sen Gupta (1996). Who takes the credit? Gender, power, and control over loan use in rural credit programs in Bangladesh. [146] | Blue | Emp | 126 |

| 7 | *Kabeer (2001). Conflicts over credit: Re-evaluating the empowerment potential of loans to women in rural Bangladesh. [133] | Blue | Emp | 118 |

| 8 | *Hashemi et al. (1996). Rural Credit Programs and Women’s Empowerment in Bangladesh. [127] | Blue | Emp | 108 |

| 9 | Hartarska (2005). Governance and performance of microfinance institutions in Central and Eastern Europe and the Newly Independent States. [91] | Red | Emp | 107 |

| 10 | Hermes et al. (2011). Outreach and Efficiency of Microfinance Institutions. [95] | Red | Emp | 105 |

| 11 | *Cull et al. (2009). Microfinance meets the market. [119] | Red | Emp | 100 |

| 12 | Mersland and Strom (2010). Microfinance Mission Drift? [118] | Red | Emp | 96 |

| 13 | *Rahman (1999). Micro-credit initiatives for equitable and sustainable development: Who pays? [144] | Blue | Emp | 96 |

| 14 | Stiglitz (1990). Peer monitoring and credit markets. [114] | Green | Emp | 96 |

| 15 | Ahlin et al. (2011). Where does microfinance flourish? Microfinance institution performance in macroeconomic context. [147] | Red | Emp | 90 |

| 16 | Hartarska and Nadolnyak (2007). Do regulated microfinance institutions achieve better sustainability and outreach? [92] | Red | Emp | 90 |

| 17 | Cull et al. (2007). Financial performance and outreach: A global analysis of leading microbanks. [87] | Red | Emp | 88 |

| 18 | *Collins et al. (2009). Portfolios of the poor: How the world’s poor live on $2 a day. [102] | Blue | Emp | 73 |

| 19 | Mersland and Strom (2009). Performance and governance in microfinance institutions. [90] | Red | Emp | 73 |

| 20 | Sharma and Zeller (1997). Repayment performance in group-based credit programs in Bangladesh: An empirical analysis. [148] | Green | Emp | 69 |

© 2019 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Zaby, S. Science Mapping of the Global Knowledge Base on Microfinance: Influential Authors and Documents, 1989–2019. Sustainability 2019, 11, 3883. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11143883

Zaby S. Science Mapping of the Global Knowledge Base on Microfinance: Influential Authors and Documents, 1989–2019. Sustainability. 2019; 11(14):3883. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11143883

Chicago/Turabian StyleZaby, Simon. 2019. "Science Mapping of the Global Knowledge Base on Microfinance: Influential Authors and Documents, 1989–2019" Sustainability 11, no. 14: 3883. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11143883

APA StyleZaby, S. (2019). Science Mapping of the Global Knowledge Base on Microfinance: Influential Authors and Documents, 1989–2019. Sustainability, 11(14), 3883. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11143883