Abstract

The foodservice sector plays an important economical role in the “Langa del Barolo”, in Northwest Italy. It is now on the UNESCO (the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization) World Heritage List and is in first place in Italy in the Vineyard Landscape field, along with the Roero and Monferrato territories. The tourists who visit this area are constantly increasing and its inscription in UNESCO World Heritage List seems to have increased its international appeal even more. This study aimed at obtaining feedback from the “Langa del Barolo” restaurateurs as to their perception of the communication and promotion tools implemented to enhance the territory. A semi-structured interview, that adopted a questionnaire based on the PAPI technique, was used to survey all the 78 restaurateurs in this area. This technique was chosen to stimulate the individual propensity of the restaurant owner to share information freely. It was observed that the UNESCO status provides new stimuli for the restaurateurs when carrying out their activities, increases tourist’s interest in the “Langa del Barolo” and disseminates the local brands at an international level. Other tools, such as TripAdvisor, word-of-mouth, Slow Food and gastronomic guides, were also presented and discussed with the participants. The feedback and results demonstrate that having a UNESCO status improves and enhances the territory, making it an extremely useful promotion tool.

1. Introduction

The modern consumer has developed a growing interest for quality food and wine, mainly as a result of cultural, ethical, social and economic changes [1,2,3]. This is partly due to the rediscovery of taste that has allowed for the preservation of territorial typical products [4,5,6,7] and the traditional connections with the territory itself [8,9,10]. This trend has integrated the “Economy of Taste” concept [11], defined as the economic value of the market, into the cultural heritage of a given territory, i.e., its tangible and intangible aspects [12,13,14]. Indeed, the territory is not only the portion of land and its geographical features e.g., pedology, geomorphology, hydrology, climatology, but also the relationship between society and the resources of a determined system [15], allowing also for the concept of terroir to be evidenced.

The word terroir has been defined as “a geographical limited area where a human community generates and accumulates a set of cultural distinctive features throughout its history, along with knowledge and practices based on a system of interactions between biophysical and human factors. The combination of techniques involved in production reveals originality, confers typicity and leads to a reputation for goods originating from this geographical area and, therefore, for its inhabitants. The terroirs are live, innovating spaces that cannot be reduced to tradition alone” [16,17], even if this term has been traditionally used in the French wine sector.

The International Organization of Vine and Wine (OIV) updated the definition of “vitivinicultural terroir” with the Resolution N° 333/2010, which now refers “to an area where the collective knowledge of the interactions between the identifiable physical and biological environment and the applied vitivinicultural practices develop, providing distinctive characteristics for the products which originate in that area. Terroir includes specific soil, topography, climate, landscape characteristics and biodiversity features”. This concept is used to explain the wine quality pyramid associated with European Geographical Indications, such as Protected Designation of Origin (PDO) and Protected Geographical Indication (PGI). Some studies have evidenced the relationship between the characteristics of wine e.g., factors of the natural environment, taste and quality and its geographic origin which can create these characteristics and have analyzed the significant economic repercussions [18,19,20,21].

Recently, the term terroir has been adopted with the same meaning for foodstuff, where, the quality of wine and food production is also to be associated to this term. These products often have quality brands, such as those in the European system for the protection of the Geographical Indications (Protected Designation of Origin and Protected Geographical Indication) which mark the strongest link to the territory, requiring that all tasks involved in the production, processing and preparation be carried out in that region [22]. Several other countries besides France use the term terroir, such as Italy and Spain, to indicate high quality products developing protection and enhancement policies for these products [23,24,25]. Moreover, some authors have tried to better understand the complex relationships between terroir and product by the application of multidisciplinary tools [26,27,28].

In this context, the territory is a manifestation of its traditions and culture also at an Italian level [29]. The goods express the specific traditions that typically characterize the territory, including the well-established socio-economic relationships with the stakeholders, which, thanks to the interaction between the various territorial actors, have been consolidated over time [30]. The local product concept is synonymous with the territorial system and is considered an economic offer, proposed by one or more companies, rooted in a geographical, cultural and historical territory. This is perceived by the demand as a unitary product made up of tangible factors (e.g., agro-food products, food craft products) and intangible factors (e.g., service, information, culture, history, knowledge, traditions) and is characterized by an image or brand [31].

The policy makers have now started implementing territorial development policies with the aim of disseminating local heritage along with its tangible and intangible assets and enhancing tourism [32]. Food tourism, or gastronomy tourism, is an emerging phenomenon that has expanded so much so that it has become one of the most dynamic segments of tourism in the world. Hall and Sharples [28] reported on one of the most common definitions of food tourism or gastronomy tourism: “an experiential trip to a gastronomic region, for recreational or entertainment purposes, which includes visits to primary and secondary producers of food, gastronomic festivals, food fairs, events, farmers’ markets, cooking shows and demonstrations, tastings of quality food products or any tourism activity related to food”. Quan and Wang [33] asserted that “the cuisine of the destination is an aspect of utmost importance in the quality of the holiday experience” and over a third of the income that derives from tourism comes from food.

Food tourism now takes on more of a connotation where eating and drinking become expressions of the specific culture indigenous to a particular territory, attracting enthusiasts of cultural tourism [34,35]. Wolf [36] reported on the search for a touristic experience that involves the tasting of typical food and wines framed by their own landscapes, involving a unique and specific experience linked to that particular destination. Croce and Perri [37] emphasized the importance of “coming into direct contact with the producer”. This involves visiting the territory and the production first-hand, following the product through its various stages, like selection, quality control and packaging. This is then followed by tasting on site, with the possibility of purchasing the goods directly from the producer and taking the specialties back home. Whilst Smith et al. [38] reported that food tourism is “any tourism experience in which one learns about, appreciates, or consumes branded local culinary resources”, food tourism now encompasses many aspects of cultural tourism in a broader sense, in as much as it is no longer connected exclusively to the concept of visiting monuments and art cities, but is rather becoming acquainted with new cultures and taking part in cultural events and local fairs, which means living a more complete experience [39,40,41,42,43]. Food tourism has been reported as having been born with the aim of understanding a specific foodstuff, fruit of a specific territory, so as to approach the aspects related to the cultural nature and knowledge of the territory of origin [44,45,46,47]. Therefore, the links amongst foodstuff, landscape, culture and climate, can influence the tourist’s choice [48,49,50,51,52,53,54]. Food and wine are strategic factors in defining the brand and image of destinations. Indeed, the world of tourism has several international territories where brand image is connected to food and wine values that have become gastronomy destinations, e.g., France, Italy, Spain, the USA, New Zealand, Australia, Japan and South Africa. Furthermore, Bertuccioli and Ninfali [55] also reported on how the role of the Mediterranean Diet of Spain, Greece, Italy and Morocco was included in UNESCO’s list of Intangible Cultural Heritage of Humanity in November 2010, describing it as a tool to protect and enhance the culture of food. A sense of landscape also plays an important role in enhancing local food experiences [56,57,58,59,60,61,62,63]. Food and wine tourism is aimed at the search for culinary tourism and wine tourism of a specific area with its traditions, becoming a form of both experiential and cultural tourism [64,65,66].

Food tourism is in constant growth, especially in Italy, as shown by the figures reported on tourist overnight stays by Unioncamere, which reached 110 million for food and wine tourism in 2017. The estimated tourist turnover generated by food and wine exceeded 12 billion euros (equal to 15.1 of the total tourism outlay), which had a significant positive effect, not only on the Italian economic system, but also from a cultural point of view [67]. The Tourism and Heritage & Culture rankings place Italy in first place (Unicredit Bank in collaboration with the Italian Touring Club—the most important Italian national tourist organization). This demonstrates that the food and wine component is not only an interesting tourist segment, but that it is also a fundamental aspect of tourist attraction [68,69]. Indeed, Italy is chosen by 26% of European tourists within the broad sector of cultural tourism [70] and has one of the richest and most diverse cultural heritages in the world [71,72]. Moreover, gastronomy is what spurs many tourists to travel, followed by culture, sports and shopping. This is supported by Unioncamere, that states gastronomic tourism has increased over the last decade from 5% in 2008 to 26% in 2017, with a greater interest for foreign tourists than Italian tourists. The demand for holidays that include food and wine tours, visits to agro-food companies and wineries is constantly increasing. The most popular activities during a holiday have been reported to be tied to tastings of local food and wine (over 13% of the total Italian tourism), while 8.6% buy artisanal and food and wine products [66,67].

The first report on Italian food and wine tourism [73] stated that gastronomy tourists showed a strong interest in all the experiences linked to the food and wine themes. They took part in a wide range of activities e.g., food and wine events, visits to local agricultural markets and tasting typical dishes in a local restaurant. Moreover, they searched for the possibility to have food and wine itineraries guided by local experts and visited wineries and/or breweries. The enogastronomic tourist wants to live an experience which includes photographing the dishes tasted on holiday and frequently sharing these on social networks. Consequently, if the experience is positive, the gastronomy tourist is more likely to buy food and wine products than a traditional tourist and will probably go back home and recommend it to others by word of mouth [73].

In this context, wine tourism plays a significant role. Wine is an attractive and representative asset of the culture of an area, life, dialogues, meals and traditions that characterize a given territory. Wine is unquestionably linked to its terroir as it derives its specificity and recognition on the market from the factors that integrate tradition and excellence. Furthermore, wine takes on a personality of its very own and becomes the interpretation of a specific territory where the product is closely linked to the production traditions in a given area, qualifying it as a patrimony endowed with a precise identity, according to internationally-accepted denominations [74]. The XII Wine Tourism in Italy Report [75] also provides various definitions of wine tourism. Johnson [76] concentrated on the recreational aspects of a visit to wine cellars, whilst Getz and Brown [62] described the concept of wine tourism as having: A type of consumption/purchase of a touristic product, an opportunity for economic development for the territorial offer, a business opportunity for wine producing companies and a complementary way as a main source of income and jobs in rural areas [77,78].

In 2018, the United Nations promoted sustainable tourism with the aim of raising awareness among citizens and companies of the need to enhance the cultural and natural characteristics of the territory. As part of this initiative, the Italian Agriculture and Culture Ministers proclaimed the international year of Italian food in the world in 2018, highlighting the strong links amongst food, landscape and culture. These are internationally recognized distinctive elements of Italian identity that can boast a high level reputation. Moreover, the connection between quality food production and tourism is one of the bases of sustainable development of a territory.

This study was carried out to obtain feedback on the foodservice operators’ perception as to some initiatives and/or tools implemented for territorial enhancement i.e., UNESCO, Slow Food, gastronomic guides and electronic word-of-mouth (eWOM) and the relative importance assigned to them by the restaurateurs of the Langa del Barolo.

2. Literature Review

There are numerous communication and promotion tools dedicated to geographical areas worldwide. Some of them were identified on the basis of their presence in the selected territory and their diffusion. The recognition by UNESCO and the Slow Food organization is now considered internationally as a sign of quality connected to the territory, as can be seen in gastronomic guides, e.g., the national Gambero Rosso guide and the international Michelin guide, along with the word-of-mouth (WOM) dissemination such as the TripAdvisor platform, all of which have a direct impact on local foodservice.

UNESCO recognition is a strong advantage for the food tourism sector, confirming that tradition, gastronomy and cooking styles are part of a worldwide cultural heritage [75,79,80,81]. It has also become a new international and territorial tool for the Langa del Barolo area [82]. This quality recognition improved tourism flows and has had a positive economic impact on the territory [52,83,84]. Moreover, the diffusion of the brand itself can be increased as can its appeal, thus empowering the local economies [54]. Some authors used quantitative methods to define the influence of UNESCO recognition on tourism development e.g., Prud’homme [85] carried out a comparative econometric analysis to define the attractiveness of French UNESCO sites and highlighted that the Michelin Guide was more important than the inscription on the World Heritage List; Mazanec et al. [86] used a model of destination competitiveness to define the influence of cultural heritage on tourism economy; Kim et al. [87] used the contingent evaluation method to assess the economic value of a South Korean world heritage site.

The Slow Food organization is the most important association for the food sector in the selected area. It aims at promoting territorial tourism, safeguarding gastronomic heritage and culture and protecting rare local food products [88,89,90], and has activated some tools with the aim of reaching these objectives, e.g., Slow Food presidia [91,92,93,94]. Moreover, some authors used qualitative and quantitative methods to analyzed the phenomenon of Slow Food initiatives e.g., Reznickova and Zepeda [95] gave a inductive thematic analysis supported by semi-structured interviews to the members of Slow Food University of Wisconsin association to investigate into the importance of the Self-Determination Theory; Jung et al. [96] carried out an exploratory factor analysis to determine which quality elements of food festivals have a direct impact on the visitors’ satisfaction level.

Gastronomic guides are worldwide tools used to promote high quality foodservices and some of them are internationally well known. On the one hand, the Michelin French guide is the most affirmed and the most studied e.g., when it comes to comparing the communication strengths of websites reporting on stellar restaurants and culinary tourists’ behaviour [97], or the diverse organizational structures within the stellar cuisines [98]. On the other, the Italian Gambero Rosso guide is specialized in reporting on high quality vineyard areas and sustainable production [99,100].

Word of mouth (WOM) is yet another tool able to promote territories and their operators and can be a strong tool for the valorization of a territory. However, although different positions have been taken as its use, its power and collateral effects, it is generally considered a reliable and credible tool supported by a friendly evaluation [101,102,103,104,105,106]. The innovation in technologies and the increased popularity and diffusion of the use of Internet has led to the emergence of a new form of WOM, the electronic word-of-mouth (eWOM) [107,108,109,110,111].

The internet eWOM is able to put a large population of international users that were previously unacquainted, into contact with one another [112,113,114]. Indeed, the eWOM is considered one of the most influential forms of informal media amongst consumers, businesses and the population [115]. Electronic word of mouth influences the consumer’s buying behaviour through an online exchange of customer opinions and experiences as to commodities, using social networking sites [116]. This kind of information forms consumer expectations of the brand. Therefore, if the consumers’ expectations of a brand are managed correctly, managers may be able to mitigate some brand image problems [117]. Moreover, eWOM has a more powerful effect on destination image, attitude and travel intention than does face-to-face WOM [118]. Conversely, eWOM can be a particularly powerful tool for the dissemination of vindictive messages posted by highly dissatisfied customers [119] and may also lead to asymmetric information, which may distort prices and reduce incentives to provide quality services [120]. TripAdvisor, the most important platform on the evaluation of foodservice, is considered a reliable tool to create helpful online information and identify the main characteristics of tourist services as it provides useful information and influences different stakeholders [118,121,122,123].

However, the studies rarely include the restaurant managers in their evaluation. Some authors included restaurateurs and other food supply chain stakeholders in their studies. Several aspects were covered, e.g., the wine purchasing process where the needs of restaurateurs are fundamental [124], the trust dimension of relationships amongst restaurateurs, wholesale distributors and farmers [125], the menu in organic restaurants [126], or the use of local products in a specific area [127]. On the basis of this information, it can be deduced that there is a scarcity of studies dedicated to the restaurateurs’ perception and assessment of quality signs in a specific territorial area, e.g., “Langa del Barolo”.

3. Materials and Methods

This paper analyses the Barolo restaurateurs’ perception of some territorial communication and promotion tools in the province of Cuneo (Italy), in Piedmont Region. Restaurants are the main stakeholders of food tourism and the local cuisine represents an important element of the intangible heritage of a territory where food is a strong stimulus to visit a destination.

3.1. Study Area

Piedmont is a north-western region of Italy that is undergoing deep economic transformation as it is passing from a widely-diffused industrial culture in decline, to a diversification of the regional economy, which involves also the development of the tourism sector. Indeed, the last 20 years have witnessed innovative governance policies for the immense historical, naturalistic and gastronomic heritage of this territory. These seem to have been fruitful, as the overall tourist flow data had an upward trend in the 2006–2015 period, with an increase of 23% in overnight stays and 41% of arrivals, for a total of 13.6 million overnight stays in 2015 [128].

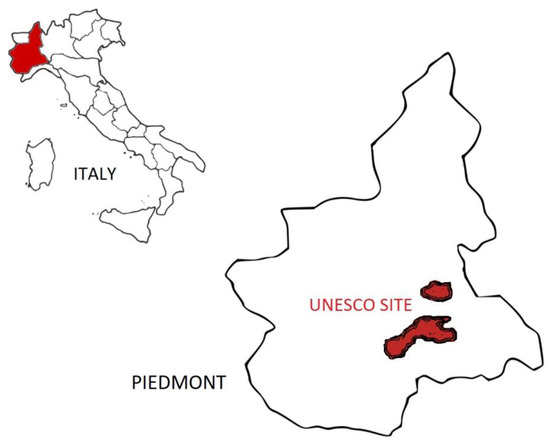

The Langhe, a hilly area to the south of Piedmont in the province of Cuneo, has become one of the most popular territories with a substantial increase in tourism, in particular wine and food tourism. This area is famous for two extraordinary products: Its Barolo wine and the white truffles of Alba. On 22 June 2014, the “Vineyard Landscape of Piedmont: Langhe-Roero and Monferrato” was added to the UNESCO’s World Heritage list, making it the 50th UNESCO site in Italy and the first Italian Vineyard landscape [129].

This landscape “covers five distinct wine-growing areas with outstanding landscapes and the Castle of Cavour, an emblematic name both in the development of vineyards and in Italian history. It is located in the southern part of Piedmont, between the Po River and the Ligurian Apennines, and encompasses the whole range of technical and economic processes relating to the winegrowing and winemaking that has characterized the region for centuries” [130]. This site has six sub-areas that fall within the boundaries of three provinces: Alessandria (AL), Asti (AT) and Cuneo (CN). The sub-areas are “Langa del Barolo”, “Castello di Grinzane Cavour”, “Colline del Barbaresco”, “Nizza Monferrato e il Barbera”, “Canelli e l’Asti Spumante”, “Monferrato degli Infernot”. There are 29 municipalities with 10,780 hectares [82] (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Italy, the Piedmont Region and Vineyard Landscape of Piedmont: Langhe-Roero and Monferrato UNESCO site.

The “Langhe—Roero and Monferrato” terroir is one of the most internationally well-known destinations for the quality of its wine and foodstuff [75]. The Wine Enthusiast Company placed Piedmont in second place, after Finger Lakes (NY), among the 10 most important wine tourism destinations in the world [75]. Moreover, The New York Times reported that Turin and the UNESCO world heritage landscapes of the Langhe-Roero and Monferrato are places to be visited by tourists interested in the history of the territory and the quality of the wine and food [131]. The data from the Piedmont Tourism Observatory show that the Langhe and Roero areas have had a significant increase in tourist flows over the last few years [128].

The study group included restaurateurs operating in the area of Langa del Barolo that is one of six areas of “The Vineyard Landscape of Piedmont: Langhe-Roero and Monferrato” site, recognized by UNESCO in 2014. The Langa of Barolo has 1940 hectares of vineyards, where the Nebbiolo grape variety prevails. This cultivar is used to make the famous red Barolo wine, an internationally renowned Piedmontese wine. The peculiarities of the soil and the climatic conditions in this area support the cultivation of this variety and empower the historic vocation for the cultivation of the Nebbiolo grape-variety. The birth and development of Barolo was strongly encouraged and supported by the Savoy Royal Family and the properties of the Falletti Family. Moreover, the Langa del Barolo is also characterized by its landscapes based on a bucolic hilly environment and fashioning anthropic presence through vineyards, farms and historical villages [82].

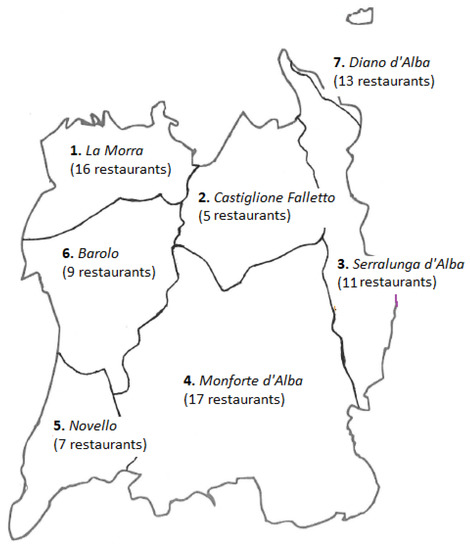

This territory was chosen as it is well known worldwide and attracts a high number of tourists, not only for its wine but also for other specialties, such as truffles. All the 78 restaurateurs in this area took part in the survey (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

The Langa del Barolo area and the number of the restaurants per municipality.

3.2. Survey

The survey was carried out by a semi-structured interview using a questionnaire with the PAPI technique (Paper and Pencil Interviewing) [132,133], in line with the objective identified. The order of the questions can be changed depending on the individual propensity of the restaurant owner to share information, so they could explain their thoughts and also their experiences freely, in line with other authors [134].

The questionnaire aimed at the investigation of how important communication and promotion tools are to the restaurateurs. A preliminary version of the questionnaire was pre-tested on five restaurateurs of the same area to detect any errors and assess any structural weaknesses. This allowed the authors to make some adjustments to the questionnaire to make it as pertinent as possible.

This step was pivotal as the results emphasized the relevant interest for the national guide Gambero Rosso and there being less interest in the National quality sign Bandiera Arancione, as well as promotion policies made by local authorities, such as the Unione di Comuni Collinari di Langa e di Barolo. The Gambero Rosso Guide was included in the questionnaire in the definitive version and Bandiera Arancione and local authorities were excluded.

The final version of the questionnaire was divided into two parts. The first one collected the interviewees’ information: restaurant name, type of restaurant, municipality, website, social channels, capacity, average cost of one meal and cooking style proposed. The second part covered the restaurateurs’ perception on communication and promotion tools: UNESCO status, food and wine guides (Michelin and Gambero Rosso), TripAdvisor (eWOM) and Slow Food. The restaurateurs were asked if they knew the tools and, if they did, they were asked to give an opinion on each one and to give a mark according to the Likert scale. These scales had seven points, which ranged from one to seven, where 1 expresses minimal approval and 7, maximum approval. This scale had a neutral mid-point, with a good variability and allows for a better performance than do other scales [135,136]. Lastly, an open question was put as to communication and promotion tools to obtain further information also about other tools, e.g., the conventional WOM.

All the restaurants replied to the questionnaire [137]. The study group was recruited directly at the restaurants from 15 July to 10 September 2016. Each interview lasted 30 min. The authors analyzed the interview results in two steps i.e., in the first phase, they evaluated them individually, so as to avoid them being influenced [138]; in the second phase, they shared and compared individual evaluations and the fundamental issues pertinent to the aim of this paper were extrapolated [139,140].

4. Results

The study sample is made up of 78 full service restaurants, divided into 49 “traditional restaurants”, 25 had a seating capacity of <61 and 24 of >61, a conventional restaurant with classic foodservice only, 13 farms with foodservice denominated “farmhouse restaurants”, 16 “other types of restaurants” (wine rooms with foodservice, pizzerias, steak houses and pubs).

The seating capacity of the restaurants varies: 13/78 seat less than 31 persons, 19/78 can seat from 31 to 50, 20/78 from 51 to 70, 17/78 from 71 to 100 and 9/78 more than 100. The cost of a meal also varies (wine and beverage excluded): 15/78 have an average cost of less than 21 Euros, 17/78 from 21 to 25 Euros, 15/78 from 26 to 30 Euros, 16/78 from 31 to 36 Euros, 15/78 more than 41 Euros.

The restaurants have different cooking styles and some have a fusion of styles. The restaurants have changed their offer over the last two decades. Currently, 51/78 restaurants offer dishes dedicated to the Italian traditional cuisine, 45/78 offer regional and local cuisine and 8/78 also prepare international dishes to satisfy the tourists’ demand.

Communication tools used by the restaurants: 67/78 restaurants have a specific web site with some information on address, contacts and geo-localization, as well as the menu and the raw materials used, culinary tradition and territory; 76/78 are on the TripAdvisor platform, 56/78 have a dedicated Facebook page and 53/78 are on Google Platform. Facebook is used to communicate brief and just-in-time information, TripAdvisor and Google pages are used as a tool to reply to the customers’ comments. Moreover, 9/78 restaurants do not have their own website but use at least one social media platform; in any case, only 56/78 restaurateurs declared to use habitually social media (Table 1).

Table 1.

Description of the sample.

All the study sample knew about the TripAdvisor platform, 96.15% of them knew about the UNESCO and Gastronomic guides and 88.46% the Slow Food organization. All the communication/promotion tools were known by 68/78 of the study sample (87.18%).

To evaluate the results, the arithmetic average was chosen as a tool of central measurement and used to verify the difference amongst the respondents’ evaluations. The standard deviation was chosen as a measure of variability to verify the distance amongst the respondents’ evaluation as to the quality signs investigated. Moreover, the median was chosen to verify the asymmetry amongst scores [141].

The restaurateurs were asked to assess each tool and to score how important they considered it to be through the Likert scale from 1 (useless or very unreliable) to 7 (very useful or very reliable). In terms of absolute value, UNESCO got the highest score with 5.85, followed by TripAdvisor with 4.77, Slow Food with 4.67 and the Guides got the lowest score, with 4.37.

This assessment was partially confirmed by the scenario obtained by standard deviation: UNESCO got the lowest value, σ = 1.27, but TripAdvisor with σ = 2.20 was higher than Slow Food σ = 1.61 and Guides σ = 2.18. The median value highlighted that some respondents gave very low scores to TripAdvisor leading to a decrease in the average score (Table 2).

Table 2.

Knowledge and perception of the communication and promotion tools.

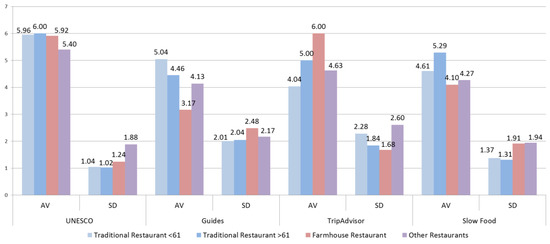

The results were analyzed also on the basis of the type of restaurant. UNESCO was the most popular, in terms of average score and standard deviation in three categories: in Traditional Restaurant >61 (AV = 6.00; σ = 1.02), Traditional Restaurant <61 (AV = 5.96; σ = 1.04) and other restaurants (AV = 5.40; σ = 1.88). TripAdvisor was the most popular in the Farmhouse Restaurant category (AV = 6.00; σ = 1.68). The Guides and Slow Food came into their own in the two Traditional Restaurant categories, i.e., the Guides in the Traditional Restaurant <61, AV = 5.04; σ = 2.01, and Slow food in the Traditional Restaurant >61, AV = 5.29; σ = 1.31 (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

The perception level on communication and promotion tools on the basis of type of restaurant.

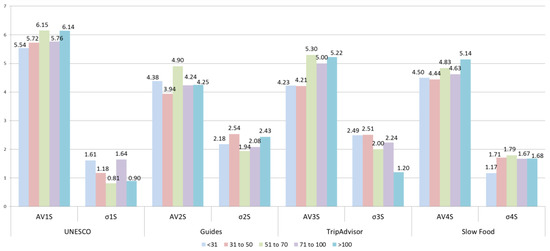

Moreover, the results were analyzed on the basis of the restaurant capacity and the Average Cost per Meal (ACM) in each restaurant surveyed. UNESCO got the highest score for capacity in all ranges and the two highest scores in the “51 to 70 range” as well as in the “>100 range” with the lowest standard deviation (respectively AV1S = 6.15; σ1S = 0.81 and AV1S = 6.14; σ1S = 0.90). Moreover, the restaurateurs with the highest capacity gave both TripAdvisor and Slow Food a high score (AV3S = 5.22; AV4S = 5.14, respectively), with a more homogenous opinion (σ3S = 1.20; σ4S = 1.68) (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

The perception level on communication and promotion tools on the basis of restaurant capacity (range).

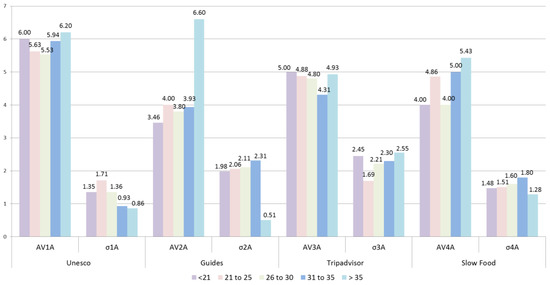

UNESCO got the highest score in the 4/5 ACM classes. The average scores obtained were always higher than 5.5 and the results of the standard deviation demonstrated that the restaurateurs were more homogenous in their opinions (σ1A < 1.71). However, the Guides, got the highest score in the >35 Euro class with the lowest standard deviation value (AV1A = 6.60; σ1A = 0.51). The performance of the Guides were not so high in the other classes, both in terms of AV2A and in σ2A. TripAdvisor and Slow Food got moderate results with similar average scores, but different standard deviations in favor of Slow Food (σ4A < 1.80). (Figure 5)

Figure 5.

The perception level on communication and promotion tools on the basis of average cost per meal.

The questionnaire obtained information as to the restaurateurs’ opinion on communication and promotion tools in the Langa del Barolo territory. A total of 53.88% added information. Most of them indicated that having a UNESCO status had a positive economic impact on the territory, as can be seen by the rise in the number of tourists over last few years. On the one hand, restaurateurs (76.19% of the respondents) had an increase in tourist flow, with economic advantages, after having been given a UNESCO status and the new tourists seemed to be part of a different class of cultural tourists. On the other hand, 23.81% of the respondents were of the opinion that it is too early to evaluate the UNESCO status and that only time will tell if it has positive economic spin-offs. However, 54.76% of the respondents said that the food and beverage heritage of a UNESCO area was what motivated the tourists the most to visit it and 42.86% affirmed that most tourists came from northern Europe and North America. Moreover, 42.86% of the respondents evidenced the importance of the old Word of Mouth (WOM); indeed, in some cases, the WOM was perceived as the main promotion and communication tool for their proposed foodservices.

Lastly, a total of 35.71% of the respondents evidenced the importance of the “three pillars” of the foodservices offered in the Langa, i.e., local tradition and culture, foodservice quality and food peculiarities. These pillars lay the foundations for improvement in local foodservices, based on the restaurateurs’ competence and honesty.

5. Discussion

The international UNESCO status seems to provide new motivations for the restaurateurs that declared to expect some benefits in terms of the development of local economy and increase in tourists’ interest in the Langa del Barolo area. Moreover, the results showed that, although the Slow Food initiatives were generally evaluated as positive, they sometimes generated uncertainty amongst the restaurateurs, supporting some doubts reported in other studies [92,93,94].

As to the review tools, on the one hand, the Guides were evaluated with moderate positive scores and obtained the absolute highest score in the range of the most expensive restaurants. On the other hand, TripAdvisor seemed the most important promotion tool after UNESCO, on the basis of the high scores obtained in the different categories, but were also the most disputable tools in this survey, on the basis of values in the standard deviation. These results confirmed what has been reported in some studies dedicated to this type of tool. Indeed, it allowed for a fast diffusion of information about restaurants at a global level [112,113,114] and had a positive influence on consumers [113], but it should be supported by a control system to detect illicit behaviour by customers and reduce the fake reviews [119]. Moreover, the restaurateurs declared that the traditional WOM is an important tool to promote their activities. They consider it a reliable and credible tool, in line with other studies [101,103], supported by other well-known customers with their personal evaluations [102]. The different kinds of WOM (eWOM and WOM) were considered to be the main tools able to obtain information on the foodservice quality of the restaurants. The tourist can understand “if it is possible to eat good food” and “why it is good food” through other customers’ comments. Although the two different kinds of WOM do have the same target, they reach it differently: Directly, without the web, by sharing the experience in a limited geographical area with friends; and indirectly, through the web, by sharing the review information posted worldwide.

6. Conclusions, Limitations and Future Research

The study reached its goal of being able to analyze the Langa del Barolo restaurateurs’ perceptions on communication and promotion tools. A high value was given to the WOM and Slow Food initiatives but UNESCO recognition was considered an unique opportunity to enhance a territory, link local operators and support their economic growth. Indeed, restaurateurs seemed to want more collaboration from all the operators in the Langa del Barolo area, i.e., policy makers and territorial stakeholders, to enhance the tourist demand, in line with the sustainable development goals.

As aforementioned, this survey analyzed the restaurateurs’ perception on the communication and promotion tools present in this area. The majority of the restaurateurs know and use some tools to obtain feedback by customers, such as TripAdvisor and the Google platform and communicate their initiatives on their own website and Facebook, but only part of them do so. This kind of behavior and the fact that the analyzed tools differ could be considered a limitation of the study. However, the results showed that there was a strong and diffused interest on the part of those foodservice operators who pay attention to the UNESCO status, TripAdvisor, Slow Food and the “evergreen” WOM. The data collected evidences a clear need for further analysis; moreover, the results suggest that it might be advisable to implement a cluster analysis of the restaurateurs’ perception on the communication and promotion tools. Therefore, further analysis is ongoing.

Author Contributions

The authors contribute equally to the study.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Fabio Paruzzo for his bibliographic research, Barbara Wade for her linguistic advice and Luigi Bollani for his useful suggestions.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Bernues, A.; Olaizola, A.; Corcoran, K. Labelling information demanded by European consumers and relationship with purchasing motives, quality and safety of meat. Meat Sci. 2003, 65, 1095–1106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caputo, V.; Nayga, R.M.J.; Scarpa, R. Food miles or carbon emissions? Exploring labelling preference for food transport footprint with a stated choice study. Aust. J. Agric. Resour. Econ. 2013, 57, 465–482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calabrò, G.; Vieri, S. The reorganization of agricultural production patterns and food consumption for managing critical issues of current models. Qual.-Access Success 2017, 18, 124–129. [Google Scholar]

- Barjolle, D.; Sylvander, B. PDO and PGI Products: Market, Supply Chains and Institutions. Final Report: Protected Designations of Origin and Protected Geographical Indications in Europe: Regulation or Policy? Recommendations. European Commission, FAIR 1-CT95–0306. 2000. Available online: http://www.origin-food.org/pdf/pdo-pgi.pdf (accessed on 14 May 2018).

- Ikerd, J.E. Local food: Revolution and reality. J. Agric. Food Inf. 2011, 12, 49–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonadonna, A.; Peira, G.; Varese, E. The European Optional Quality Term “Mountain Product”: Hypothetical Application in the Production Chain of a Traditional Dairy Product. Qual.-Access Success 2015, 16, 99–104. [Google Scholar]

- Peri, C. The universe of food quality. Food Qual. Prefer. 2006, 17, 3–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belliveau, S. Resisting global, buying local: Goldschmidt revisited. Great Lake Geogr. 2005, 12, 45–53. [Google Scholar]

- Morgan, K.; Mardsen, T.; Murdoch, J. Worlds of Food: Place, Power, and Provenance in the Food Chain; Oxford University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Tregear, A.; Kuznesof, S.; Moxey, A. Policy initiatives for regional foods: Some insights from consumer research. Food Policy 1998, 23, 383–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peira, G.; Soster, M.; Bonadonna, A. The Italian public policies for the economy of taste: The regional point of view. Qual.-Access Success 2018, 19, 137–144. [Google Scholar]

- Cerquetti, M.; Ferrara, C. Marketing research for cultural heritage conservation and sustainability: Lessons from the field. Sustainability 2018, 10, 774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chever, T.; Renault, C.; Renault, S.; Romieu, V. Value of Production of Agricultural Products and Foodstuffs, Wines, Aromatized Wines and Spirits Protected by a Geographical Indication (GI); Final Report; AND International: Capelle aan den Ijssel, The Netherlands; European Commission: Brussels, Belgium, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- EU. Database of Origin & Registration, DOOR. Available online: http://ec.europa.eu/agriculture/quality/door/list.html?locale=it (accessed on 20 June 2018).

- Raffestin, C.; Butler, S.A. Space, territory, and territoriality. Environ. Plan. D 2012, 30, 121–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teissier du Cros, M.; Vincent, A.L. (Eds.) Rencontres Internationales Planète Terroirs, UNESCO 2005: Actes; UNESCO: Montpellier, France; Association Terroirs & Cultures: Paris, France, 2007; Available online: http://unesdoc.unesco.org/images/0015/001543/154388f.pdf (accessed on 16 August 2018).

- Gyimóthy, S. The reinvention of terroir in Danish food place promotion. Eur. Plan. Stud. 2017, 25, 1200–1216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Leeuwen, C.; Seguin, G. The concept of terroir in viticulture. J. Wine Res. 2006, 17, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Charters, S. Marketing terroir: A conceptual approach. In Proceedings of the 5th International Academy of Wine Business Research Conference, Auckland, New Zealand, 8–10 February 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Marchini, A.; Riganelli, C.; Diotallevi, F.; Paffarini, C. Factors of collective reputation of the Italian PDO wines: Ananalysis on central Italy. Wine Econ. Policy 2014, 3, 127–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ditter, J.G.; Brouard, J. The competitiveness of French protected designation of origin wines: A theoretical analysis of the role of proximity. J. Wine Res. 2014, 25, 5–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gragnani, M. The EU regulation 1151/2012 on quality schemes for agricultural products and foodstuffs. Eur. Food Feed Law Rev. 2013, 8, 376–385. [Google Scholar]

- Aurier, P.; Fort, F.; Sirieix, L. Exploring terroir product meanings for the consumer. Anthropol. Food 2005, 4. Available online: https://journals.openedition.org/aof/187 (accessed on 16 August 2018).

- Hassan, D.; Monier-Dilhan, S. National brands and store brands: Competition through public quality label. Agribusiness 2006, 22, 21–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boccia, F.; Covino, D.; Sarno, V.; Malgeri Manzo, R. The role of typical local products in the international competitive scenario. Qual.-Access Success 2017, 18, 130–134. [Google Scholar]

- Bérard, L.; Marchenay, P.; Delfosse, C. Les « produits de terroir »: De la recherche à l’expertise. Ethnol. Fr. 2004, 34, 591–600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barham, E. Translating terroir: The global challenge of French AOC labelling. J. Rural Stud. 2003, 19, 127–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hall, C.M.; Sharples, L. The consumption of experiences or the experience of consumption? An introduction to the tourism of taste. In Food Tourism around the World; Elsevier Butterworth-Heinemann: Oxford, UK, 2003; pp. 1–24. [Google Scholar]

- Montanari, M. The Culture of Food; Wiley-Blackwell: Oxford, UK, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Santagata, W. White Paper on Creativity. Towards an Italian Model of Development; Università Bocconi Editore: Milan, Italy, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Bonadonna, A.; Duglio, S. A Mountain Niche Production: The case of Bettelmatt cheese in the Antigorio and Formazza Valleys (Piedmont—Italy). Qual.-Access Success 2016, 17, 80–86. [Google Scholar]

- Magagnoli, S. Eating tradition: Typical products, distinction and the myth of memory. Glob. Environ. 2018, 11, 154–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quan, S.; Wang, N. Towards a structural model of the tourist experience: An illustration from food experiences in tourism. Tour. Manag. 2004, 25, 297–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mnguni, E.M.; Giampiccoli, A. Indigenous food and tourism for community well-being: A possible contributing way forward. Mediterr. J. Soc. Sci. 2015, 6, 24–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Henderson, J. Food tourism reviewed. Br. Food J. 2009, 111, 317–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolf, E. Culinary Tourism: A Tasty Economic Proposition; International Culinary: Portland, OR, USA, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Croce, E.; Perri, G. Food and Wine Tourism: Integrating Food, Travel and Territory; CABI Tourism Texts: Wallingford, UK, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, S.L.J.; Honggen, X. Culinary tourism supply chains: A preliminary examination. J. Travel Res. 2008, 46, 289–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prat Forga, J.M.; Cànoves Valiente, G. Cultural change and industrial heritage tourism: Material heritage of the industries of food and beverage in Catalonia (Spain). J. Tour. Cult. Chang. 2017, 15, 265–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Getz, D. Explore Wine Tourism: Management, Development and Destinations; Cognizant Communication Corporation: New York, NY, USA, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Oh, M.J.; Lee, T.J. How local festivals affect the destination choice of tourists. Event Manag. 2012, 16, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López-Guzmán, T.; Sánchez-Cañizares, S. Gastronomy, tourism and destination differentiation: A case study in Spain. Rev. Econ. Financ. 2012, 1, 63–72. [Google Scholar]

- Park, J.H.; Chung, L.C. The impact of reputation of culture & tourism oriented markets on revisit and WOM intention in traditional markets. J. Distrib. Sci. 2016, 77–86. [Google Scholar]

- Boniface, P. Tasting Tourism: Travelling for Food and Drink; Ashgate Publishing Ltd.: Aldershot, UK, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Hjalagar, A.; Richards, G. Tourism and Gastronomy; Routledge: London, UK, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Brownlie, D.; Hewer, P.; Horne, S. Culinary tourism: An exploratory reading of contemporary representations of cooking. Consum. Mark. Cult. 2005, 8, 7–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, E.; Avieli, N. Food in tourism: Attraction and impediment. Ann. Tour. Res. 2004, 31, 775–778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Durydiwka, M. Food Tourism—A new (?) trend in cultural Tourism. Pr. Stud. Geogr. 2013, 52, 9–30. [Google Scholar]

- Ellis, A.; Park, E.; Kim, S.; Yeoman, I. What is food tourism? Tour. Manag. 2018, 68, 250–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garibaldi, R.; Pozzi, A. Creating tourism experiences combining food and culture: An analysis among Italian producers. Tour. Rev. 2018, 73, 230–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iizuka, R.; Kikuchi, T. A village of high fermentation: Brewing culture-based food tourism in Watou, West Flanders, Belgium. Eur. J. Geogr. 2016, 7, 58–72. [Google Scholar]

- Jiménez Beltrán, J.; López-Guzmán, T.; Santa-Cruz, F.G. Gastronomy and Tourism: Profile and Motivation of International Tourism in the City of Córdoba, Spain. J. Culin. Sci. Technol. 2016, 14, 347–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, K.H.; Packer, J.; Scott, N. Travel lifestyle preferences and destination activity choices of Slow Food members and non-members. Tour. Manag. 2015, 46, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pearson, D.; Pearson, T. Branding Food Culture: UNESCO Creative Cities of Gastronomy. J. Food Prod. Mark. 2017, 23, 342–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bertuccioli, A.; Ninfali, P. The Mediterranean Diet in the era of globalization: The need to support knowledge of healthy dietary factors in the new socio-economical framework. Mediterr. J. Nutr. Metab. 2014, 7, 75–86. [Google Scholar]

- Duffy, L.N.; Kim, G.; Jodice, L.W.; Norman, W.C. Coastal Tourist Interest in Value-Added, Aquaculture-Based, Culinary Tourism Opportunities. Coast. Manag. 2017, 45, 310–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boksberger, P.; Carlsen, J. Enhancing consumer value in wine tourism. J. Hosp. Tour. Res. 2015, 39, 132–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carmichael, B.A. Understanding the Wine Tourism Experience for Winery Visitors in the Niagara Region, Ontario, Canada. Tour. Geogr. 2005, 7, 185–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brouder, P.; De la Barre, S. Consuming stories: Placing food in the Arctic tourism experience. J. Herit. Tour. 2013, 8, 213–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cruz, M.; Fernandes, T. Dimensions and outcomes of experience quality in tourism: The case of Port wine cellars. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2016, 31, 371–379. [Google Scholar]

- Williams, P. The Evolving Images of Wine Tourism Destinations. Tour. Recreat. Res. 2001, 26, 3–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Getz, D.; Brown, G. Critical success factors for wine tourism regions: A demand analysis. Tour. Manag. 2006, 27, 146–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ben-Nun, L.; Cohen, E. The important dimensions of wine tourism experience from potential visitors’ perception. Tour. Hosp. Res. 2009, 9, 20–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Tourism Organization. Second Global Report on Gastronomy Tourism; UNWTO: Madrid, Spain, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Sormaza, U.; Akmeseb, H.; Gunesc, E.; Aras, S. Gastronomy in Tourism. In Proceedings of the 3rd Global Conference on Business, Economics, Management and Tourism, Rome, Italy, 26–28 November 2015. [Google Scholar]

- World Tourism Organization. Global Report on Food Tourism; UNWTO: Madrid, Spain, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- ISNART. Unioncamere, Turismo e Enogastronomia; ISNART: Rome, Italy, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Unicredit and TCI. Rapporto sul Turismo; Unicredit and TCI: Milano, Italy, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Maltese, F.; Giachino, C.; Bonadonna, A. The Safeguarding of Italian Eno-Gastronomic Tradition and Culture around the World: A Strategic Tool to Enhance the Restaurant Services. Qual.-Access Success 2016, 17, 91–96. [Google Scholar]

- Flash Eurobarometer. Report. Preferences of European towards Tourism. 2016. Available online: http://ec.europa.eu/COMMFrontOffice/publicopinion/index.cfm/Survey/getSurveyDetail/instruments/FLASH/surveyKy/2065 (accessed on 14 June 2018).

- Iadanza, C.; Cacace, C.; Del Conte, S.; Spizzichino, D.; Cespa, S.; Trigila, A. Cultural heritage, landslide risk and remote sensing in Italy. In Landslide Science and Practice: Risk Assessment, Management and Mitigation; Margottini, C., Canuti, P., Sassa, K., Eds.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2013; Volume 6, pp. 491–501. [Google Scholar]

- Nicu, I.C. Natural hazards—A threat for immovable cultural heritage. A review. Int. J. Conserv. Sci. 2017, 8, 375–388. [Google Scholar]

- Garibaldi, R. Primo Rapporto sul Turismo Enogastronomico Italiano 2018; Centro Editoriale Librario Studium Bergomense: Bergamo, Italy, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Demossier, M. Contemporary lifestyles: The case of wine. In Culinary Taste. Consumer Behavior in the International Restaurant Sector; Sloan, D., Ed.; Elsevier Butterworth-Heinemann: Oxford, UK, 2004; pp. 93–108. [Google Scholar]

- Borsa Internazionale del Turismo. Città del Vino, XII Rapporto sul Turismo del Vino in Italia; Borsa Internazionale del Turismo: Milano, Italy, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson, H. Wine Tourism in New Zealand—A National Survey of Wineries; University of Otago: Otago, New Zealand, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Peris-Ortiz, M.; Del Río Rama, C. Wine and Tourism. A Strategic Segment for Sustainable Economic Development; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Corigliano, M.A. Wine routes and territorial events as enhancers of tourism experiences. In Wine and Tourism: A Strategic Segment for Sustainable Economic Development; Springer International Publishing: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2015; pp. 41–56. [Google Scholar]

- Matta, R. Food incursions into global heritage: Peruvian cuisine’s slippery road to UNESCO. Soc. Anthropol. 2016, 24, 338–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Medina, F.X. Mediterranean diet, culture and heritage: Challenges for a new conception. Public Health Nutr. 2009, 12, 1618–1620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Strangio, D.; Tamborrino, R. Urban heritage and ethnic food: The Little Italy of New York and its image for a comparative study. Preliminary aspects of an itinerary project. Citta Stor. 2016, 11, 91–121. [Google Scholar]

- UNESCO World Heritage List. The Vineyard Landscape of Piedmont: Langhe-Roero and Monferrato. Executive Summary. Available online: https://whc.unesco.org/en/list/1390/multiple=1&unique_number=1971 (accessed on 6 July 2018).

- Forné, F.F. Cheese tourism in a world heritage site: Vall de Boí (Catalan Pyrenees). Eur. J. Tour. Res. 2015, 11, 87–101. [Google Scholar]

- Din, B.H.; Habibullah, M.S.; Tan, S.H. The effects of world heritage sites and governance on tourist arrivals: Worldwide evidence. Int. J. Econ. Manag. 2017, 11, 437–448. [Google Scholar]

- Prud’homme, R. Les Impacts Socio-Economiques de L’inscription d’un Site sur la Liste du Patrimoine Mondial: Trois Etudes; Technical report for UNESCO; UNESCO’s World Heritage; Mimeo: Paris, France, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Mazanec, J.A.; Wober, K.; Zins, A.H. Tourism destination competitiveness: From definition to explanation? J. Travel Res. 2007, 46, 86–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.S.; Wong, K.K.F.; Cho, M. Assessing the economic value of a World Heritage Site and willingness-to-pay determinants: A case of Changdeok Palace. Tour. Manag. 2007, 28, 317–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lotti, A. The commoditization of products and taste: Slow food and the conservation of agrobiodiversity. Agric. Hum. Values 2010, 27, 71–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petrini, C. Slow Food Nation: Why Our Food Should Be Good, Clean, and Fair; Rizzoli International Publications: New York, NY, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Petrini, C. Slow Food Revolution: A New Culture for Eating and Living; Rizzoli New York: New York, NY, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Colombino, A.; Giaccaria, P. Alternative food networks between local and global: The case study of the Presidium of the Piemontese cattle breed. Riv. Geogr. Ital. 2013, 120, 225–240. [Google Scholar]

- Fonte, M. Slow Food’s Presidia: What do Small Producers do with Big Retailers? Res. Rural Sociol. Dev. 2006, 12, 203–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lazzaroni, C.; Iacurto, M.; Vincenti, F.; Biagini, D. Consumer attitudes to food quality products of animal origin in Italy. EAAP Sci. Sér. 2012, 133, 83–96. [Google Scholar]

- West, H.G.; Domingos, N. Gourmandizing poverty food: The Serpa cheese slow food presidium. J. Agrar. Chang. 2012, 12, 120–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reznickova, A.; Zepeda, L. Can Self-Determination Theory Explain the Self-Perpetuation of Social Innovations? A Case Study of Slow Food at the University of Wisconsin—Madison. J. Community Appl. Soc. 2016, 26, 3–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jung, T.; Ineson, E.M.; Kim, M.; Yap, M.H.T. Influence of festival attribute qualities on Slow Food tourists’ experience, satisfaction level and revisit intention: The case of the Mold Food and Drink Festival. J. Vacat. Mark. 2015, 21, 277–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daries, N.; Cristobal-Fransi, E.; Ferrer-Rosell, B.; Marine-Roig, E. Maturity and development of high-quality restaurant websites: A comparison of Michelin-starred restaurants in France, Italy and Spain. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2018, 73, 125–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giousmpasoglou, C.; Marinakou, E.; Cooper, J. “Banter, bollockings and beatings”: The occupational socialisation process in Michelin-starred kitchen brigades in Great Britain and Ireland. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2018, 30, 1882–1902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cacchiarelli, L.; Carbone, A.; Laureti, T.; Sorrentino, A. The value of quality clues in the wine market: Evidences from Lazio, Italy. J. Wine Res. 2014, 25, 281–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosso, G. Ethics + economy + environment = sustainability: Gambero Rosso on the front lines with a new concept of sustainability a business article by Paolo Cuccia. Wine Econ. Policy 2015, 4, 69–70. [Google Scholar]

- Arndt, J. Role of Product-Related Conversations in the Diffusion of a New Product. J. Mark. Res. 1967, 4, 291–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sen, S.; Lerman, D. Why are you Telling me this? An examination into Negative Consumer Reviews on the Web. J. Interact. Mark. 2007, 21, 76–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schiffman, L.G.; Kanuk, L.L. Consumer Behavior; Prentice Hall: Upper Saddle River, NJ, USA, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, H.-K.; Lee, T.J. Brand equity of a tourist destination. Sustainability 2018, 10, 431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vassalos, M.; Gao, Z.; Zhang, L. Factors affecting current and future CSA participation. Sustainability 2017, 9, 478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cho, H.-S.; Byun, B.; Shin, S. An examination of the relationship between rural tourists’ satisfaction, revisitation and information preferences: A Korean case study. Sustainability 2014, 6, 6293–6311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dellarocas, C. The Digitization of Word-Of-Mouth: Promise and Challenge of Online Feedback Mechanisms. Manag. Sci. 2003, 49, 1407–1424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hennig-Thurau, T.; Gwiner, K.P.; Walsh, G.; Gremler, D.D. Electronic Word-Of-Mouth Via Consumer Opinion Platforms: What Motivates Consumers to Articulate Themselves on the Internet? J. Interact. Mark. 2004, 18, 38–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, B.; Kim, S.; Heo, C.Y. Analysis of satisfiers and dissatisfiers in online hotel reviews on social media. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2016, 28, 1915–1936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Themba, G.; Mulala, M. Brand-Related E-WOM and Its Effects on Purchase Decisions: An Empirical Study of University of Botswana Students. Int. J. Bus. Manag. 2013, 8, 31–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, E.E.; Kang, H.; Ahn, H.J. Word-of-mouth of cultural products through institutional social networks. Sustainability 2017, 9, 917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chatterjee, P. Online review: Do consumers use them? Adv. Consum. Res. 2001, 28, 129–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chu, S.; Kim, Y. Determinants of Consumer Engagement in Electronic Word-Of-Mouth (E-WOM). Int. J. Advert. 2011, 30, 47–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goldsmith, R.E.; Horowitz, E. Measuring motivations for online opinions seeking. J. Interact. Advert. 2006, 6, 3–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huete-Alcocer, N. A literature review of word of mouth and electronic word of mouth: Implications for consumer behaviour. Front. Physiol. 2017, 8, 1256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hussain, S.; Guangju, W.; Jafar, R.M.S.; Ilyas, Z.; Mustafa, G.; Jianzhou, Y. Consumers’ online information adoption behavior: Motives and antecedents of electronic word of mouth communications. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2018, 80, 22–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krishnamurthy, A.; Kumar, S.R. Electronic word-of-mouth and the brand image: Exploring the moderating role of involvement through a consumer expectations lens. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2018, 43, 149–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jalilvand, M.R.; Heidari, A. Comparing face-to-face and electronic word-of-mouth in destination image formation: The case of Iran. Inf. Technol. People 2017, 30, 710–735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Campos Ribeiro, G.; Butori, R.; Le Nagard, E. The determinants of approval of online consumer revenge. J. Bus. Res. 2018, 88, 212–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manes, E.; Tchetchik, A. The role of electronic word of mouth in reducing information asymmetry: An empirical investigation of online hotel booking. J. Bus. Res. 2018, 85, 185–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casado-Díaz, A.B.; Pérez-Naranjo, L.M.; Sellers-Rubio, R. Aggregate consumer ratings and booking intention: The role of brand image. Serv. Bus. 2017, 11, 543–562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, H.A.; Law, R.; Murphy, J. Helpful Reviewers in TripAdvisor, an Online Travel Community. J. Travel Tour. Mark. 2011, 28, 675–688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perez-Aranda, J.; Guerreiro, M.M.; Mendes, J.D.C. Predictors of positive reviews on hotels: Hoteliers’ perception. Online Inf. Rev. 2018, 42, 146–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dodd, T.H.; Gultek, M.M.; Guydosh, R.M. Restaurateurs’ perceptions of wine supplier attributes. J. Foodserv. Bus. Res. 2004, 7, 73–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roy, H.; Hall, C.M.; Ballantine, P.W. Trust in local food networks: The role of trust among tourism stakeholders and their impacts in purchasing decisions. J. Destin. Mark. Manag. 2017, 6, 309–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poulston, J.; Yiu, A.Y.K. Profit or principles: Why do restaurants serve organic food? Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2011, 30, 184–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López, X.A.A.; Martín, B.G. Local restaurants and food products. An overview of Moianès (Catalonia, Spain). Ager 2016, 21, 43–72. [Google Scholar]

- Osservatorio Turistico Regionale. Dati Statistici del Turismo in Piemonte—Anno 2015; Osservatorio Turistico Regionale: Torino, Italy, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Gullino, P.; Beccaro, G.L.; Larcher, F. Assessing and monitoring the sustainability in rural world heritage sites. Sustainability 2015, 7, 14186–14210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UNESCO. Vineyard Landscape of Piedmont: Langhe-Roero and Monferrato. Available online: https://whc.unesco.org/en/list/1390/ (accessed on 14 June 2018).

- New York Times, 52 Places to Go in 2016. Available online: https://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2016/01/07/travel/places-to-visit.html (accessed on 20 June 2018).

- Brancato, G.; Macchia, S.; Murgia, M.; Signore, M.; Simeoni, G.; Blanke, K.; Hoffmeyer-Zlotnik, J. Handbook of Recommended Practices for Questionnaire Development and Testing in the European Statistical System. European Statistical System, 2006. Available online: https://www.istat.it/it/files/2013/12/Handbook_questionnaire_development_2006.pdf (accessed on 24 July 2018).

- Harrell, M.C.; Bradley, M.A. Data Collection Methods. Semi-Structured Interviews and Focus Groups; Rand National Defense Research Institute: Santa Monica, CA, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Bernard, H.R. Qualitative Methods in Cultural Anthropology; Sage: Newbury Park, CA, USA, 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Likert, R. A technique for the measurement of attitudes. In Archives of Psychology; No. 140; The Science Press: New York, NY, USA, 1932; pp. 1–55. [Google Scholar]

- Darbyshire, P.; McDonald, H. Choosing response scale labels and length: Guidance for researchers and clients. Australas. J. Mark. Res. 2004, 12, 17–26. [Google Scholar]

- Alvesson, M. Methodology for close up studies—Struggling with closeness and closure. High Educ. 2003, 46, 167–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atkinson, A.C.; Shaffir, W. Standards for Field Research in Management Accounting. J. Manag. Account. Res. 1998, 10, 41–68. [Google Scholar]

- Bonadonna, A.; Peira, G.; Giachino, C.; Molinaro, L. Traditional Cheese Production and an EU Labeling Scheme: The Alpine Cheese Producers’ Opinion. Agriculture 2017, 7, 65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peira, G.; Bollani, L.; Giachino, C.; Bonadonna, A. The Management of Unsold Food in Outdoor Market Areas: Food Operators’ Behaviour and Attitudes. Sustainability 2018, 10, 1180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frosini, B.V. Metodi Statistici. Teoria e Applicazioni Economiche e Sociali; Carocci Editore: Roma, Italy, 2009. [Google Scholar]

© 2018 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).