The Effect of Nordic Walking Intervention (NORDIN-JOY) on Individuals with Intellectual Disabilities and Their Families: A Multicenter Randomized Crossover Study

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

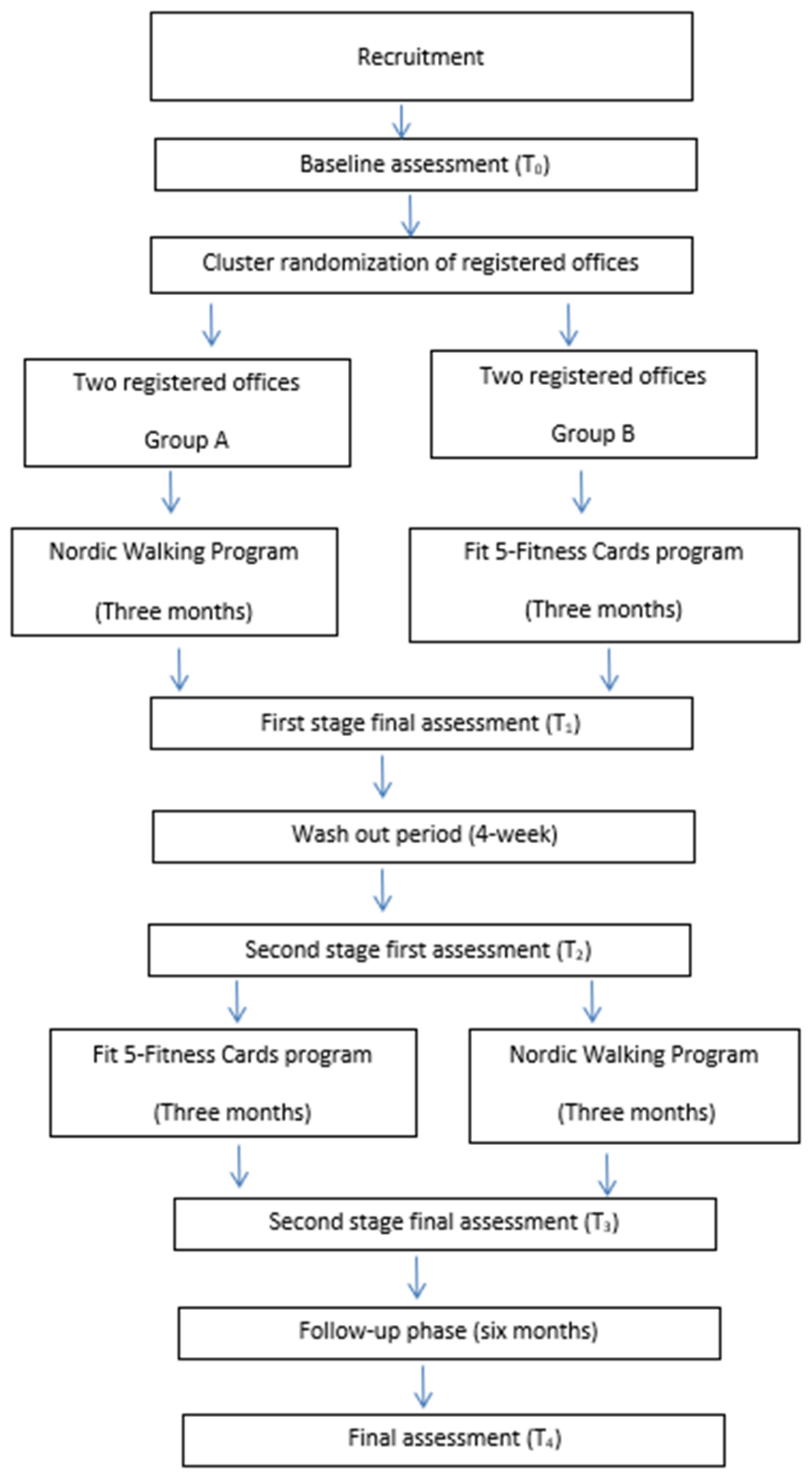

2.1. Study Design

2.2. Participants

2.3. Procedures

2.4. Measurements

2.4.1. Quality of Life

2.4.2. Functionality

- Dynamic Balance and Gait Speed: The “Timed Up and Go Test” (TUGT) will be employed, a reliable assessment tool for individuals with ID [31]. In a sample of 31 adults with ID, the TUG proved to be a feasible assessment tool, demonstrating excellent test–retest reliability (ICC: 0.90; 95% CI: 0.82–0.95) [32];

- Flexibility: The sit and reach test (SR) will be used to assess the impact of the program on the participants’ lower-body flexibility. For performing the SR, the participants will sit on the floor without shoes and with knees straight, and feet placed flat against the front-end panel of a standard SR box. Then, they will be asked to slowly reach forward as far as possible while placing the palms down along the measuring scale placed on the top of the box and to hold the position for approximately 2 s. The most distant point reached with the fingertips will be recorded (to the nearest centimeter). The best of two trials will be retained for analysis. The SR has demonstrated high reliability in a sample of 63 adolescents with ID (ICC = 0.97) [33] and has been previously used to assess fitness levels in adults with ID [34];

- Cardiorespiratory Fitness: Heart rate (HR) data will be collected using a Polar HR monitor (Polar Team Pro for iPad, version 1.0.1) during the tests. This method has been previously applied to individuals with ID [3].

2.4.3. Feasibility of the Programs

2.4.4. Cost-Effectiveness of the Program

- TC = Total cost of the program (NW or Fit 5-Fitness Cards);

- ΔE = Change in average outcomes scores (post-intervention minus pre-intervention).

- C1 = Total cost of the NW intervention;

- C0 = Total cost of the Fit 5-Fitness Cards program;

- E1 = Post-intervention outcome for the NW group (e.g., average QoL score);

- E0 = Post-intervention outcome for the Fit 5-Fitness Cards group.

2.4.5. Post-Intervention Average Weekly Physical Activity

2.5. Intervention

2.5.1. Nordic Walking

2.5.2. Fit 5-Fitness Cards

2.6. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

4. Discussion

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Nair, R.; Chen, M.; Dutt, A.S.; Hagopian, L.; Singh, A.; Du, M. Significant Regional Inequalities in the Prevalence of Intellectual Disability and Trends from 1990 to 2019: A Systematic Analysis of GBD 2019. Epidemiol. Psychiatr. Sci. 2022, 31, e91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ayán-Pérez, C.; Cancela-Carral, J.M.; Álvarez-Costas, A.; Varela-Martínez, S.; Martínez-Lemos, R.I. Water-Based Exercise for Adults with Down Syndrome: Findings from a Preliminary Study. Int. J. Ther. Rehabil. 2018, 25, 20–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayán-Pérez, C.; Martínez-Lemos, R.I.; Cancela-Carral, J.M. Reliability and Convergent Validity of the 6-Min Run Test in Young Adults with Down Syndrome. Disabil. Health J. 2017, 10, 105–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Domínguez, L.; Navas, P.; Verdugo, M.Á.; Arias, V.B. Chronic Health Conditions in Aging Individuals with Intellectual Disabilities. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 3126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carmeli, E.; Imam, B.; Bachar, A.; Merrick, J. Inflammation and Oxidative Stress as Biomarkers of Premature Aging in Persons with Intellectual Disability. Res. Dev. Disabil. 2012, 33, 369–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rydzewska, E.; Nijhof, D.; Hughes, L.; Melville, C.; Fleming, M.; Mackay, D.; Sosenko, F.; Ward, L.; Dunn, K.; Truesdale, M.; et al. Rates, Causes and Predictors of All-Cause and Avoidable Mortality in 514,878 Adults with and without Intellectual Disabilities in Scotland: A Record Linkage National Cohort Study. BMJ Open 2025, 15, e089962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez-Aldao, D.; Martínez-Lemos, I.; Bouzas-Rico, S.; Ayán-Pérez, C. Feasibility of a Dance and Exercise with Music Programme on Adults with Intellectual Disability. J. Intellect. Disabil. Res. 2019, 63, 519–527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacob, U.S.; Pillay, J.; Johnson, E.; Omoya, O.; Adedokun, A.P. A Systematic Review of Physical Activity: Benefits and Needs for Maintenance of Quality of Life among Adults with Intellectual Disability. Front. Sports Act. Living 2023, 5, 1184946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oppewal, A.; Hilgenkamp, T.I.M. Physical Fitness Is Predictive for 5-Year Survival in Older Adults with Intellectual Disabilities. J. Appl. Res. Intellect. Disabil. 2019, 32, 958–966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ortega, F.B.; Ruiz, J.R.; Castillo, M.J.; Sjöström, M. Physical Fitness in Childhood and Adolescence: A Powerful Marker of Health. Int. J. Obes. 2007, 32, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caspersen, C.; Powell, K.; Christenson, G. Physical Activity, Exercise, and Physical Fitness: Definitions and Distinctions for Health-Related Research. Public Health Rep. 1985, 100, 126–131. [Google Scholar]

- Jacinto, M.; Vitorino, A.S.; Palmeira, D.; Antunes, R.; Ferreira, J.P.; Bento, T.; Matos, R. Perceived Barriers of Physical Activity Participation in Individuals with Intellectual Disability—A Systematic Review. Healthcare 2021, 9, 1521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bossink, L.W.M.; van der Putten, A.A.; Vlaskamp, C. Understanding Low Levels of Physical Activity in People with Intellectual Disabilities: A Systematic Review to Identify Barriers and Facilitators. Res. Dev. Disabil. 2017, 68, 95–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nutsch, N.; Bruland, D.; Latteck, Ä.D. Promoting Physical Activity in Everyday Life of People with Intellectual Disabilities: An Intervention Overview. J. Intellect. Disabil. 2022, 26, 990–1014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tschentscher, M.; Niederseer, D.; Niebauer, J. Health Benefits of Nordic Walking: A Systematic Review. Am. J. Prev. Med. 2013, 44, 76–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, Y.; Xie, W.; Ossowski, Z. The Effects of Nordic Walking on Health in Adults: A Systematic Review. J. Educ. Health Sport 2022, 13, 188–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alesi, M.; Pepi, A. Physical Activity Engagement in Young People with Down Syndrome: Investigating Parental Beliefs. J. Appl. Res. Intellect. Disabil. 2017, 30, 71–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Special Olympics Fit 5-Fitness Cards. Available online: https://resources.specialolympics.org/health/fitness/fit-5 (accessed on 24 October 2024).

- Niemeier, B.S.; Wetzlmair, L.C.; Bock, K.; Schoenbrodt, M.; Roach, K.J. Improvements in Biometric Health Measures among Individuals with Intellectual Disabilities: A Controlled Evaluation of the Fit 5 Program. Disabil. Health J. 2021, 14, 100979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cugusi, L.; Solla, P.; Serpe, R.; Carzedda, T.; Piras, L.; Oggianu, M.; Gabba, S.; Di Blasio, A.; Bergamin, M.; Cannas, A.; et al. Effects of a Nordic Walking Program on Motor and Non-Motor Symptoms, Functional Performance and Body Composition in Patients with Parkinson’s Disease. NeuroRehabilitation 2015, 37, 245–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gomeñuka, N.A.; Oliveira, H.B.; Silva, E.S.; Costa, R.R.; Kanitz, A.C.; Liedtke, G.V.; Schuch, F.B.; Peyré-Tartaruga, L.A. Effects of Nordic Walking Training on Quality of Life, Balance and Functional Mobility in Elderly: A Randomized Clinical Trial. PLoS ONE 2019, 14, e0211472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Della Guardia, L.; Carnevale Pellino, V.; Filipas, L.; Bonato, M.; Gallo, G.; Lovecchio, N.; Vandoni, M.; Codella, R. Nordic Walking Improves Cardiometabolic Parameters, Fitness Performance, and Quality of Life in Older Adults With Type 2 Diabetes. Endocr. Pract. 2023, 29, 135–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skiba, A.; Marchewka, J.; Skiba, A.; Podsiadło, S.; Sulowska, I.; Chwała, W.; Marchewka, A. Evaluation of the Effectiveness of Nordic Walking Training in Improving the Gait of Persons with Down Syndrome. BioMed Res. Int. 2019, 4, 6353292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Skiba, A.; Stopa, A.; Sulowska, I.; Chwała, W.; Marchewka, A. Effectiveness of Nordic Walking and Physical Training in Improving Balance and Body Composition of Persons With Down Syndrome. J. Kinesiol. Exerc. Sci. 2018, 28, 11–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.; Kang, Y.S. The Effects of Nordic Walking on Body Composition and Physical Fitness in Obese Women with Intellectual Disability. J. Digit. Converg. 2018, 16, 427–435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ptomey, L.T.; Washburn, R.A.; Sherman, J.R.; Mayo, M.S.; Krebill, R.; Szabo-Reed, A.N.; Honas, J.J.; Helsel, B.C.; Bodde, A.; Donnelly, J.E. Remote Delivery of a Weight Management Intervention for Adults with Intellectual Disabilities: Results from a Randomized Non-Inferiority Trial. Disabil. Health J. 2024, 17, 101587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sibbald, B.; Roberts, C. Understanding Controlled Trials. Crossover Trials. BMJ 1998, 316, 1719–1720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erdfelder, E.; FAul, F.; Buchner, A.; Lang, A.G. Statistical Power Analyses Using G*Power 3.1: Tests for Correlation and Regression Analyses. Behav. Res. Methods 2009, 41, 1149–1160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paramasivam, A.; Jaiswal, A.; Minhas, R.; Wittich, W.; Spruyt-Rocks, R. Informed Consent or Assent Strategies for Research With Individuals With Deafblindness or Dual Sensory Impairment: A Scoping Review. Arch. Rehabil. Res. Clin. Transl. 2021, 3, 100115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gómez, L.E.; Alcedo, M.Á.; Arias, B.; Fontanil, Y.; Arias, V.B.; Monsalve, A.; Verdugo, M.Á. A New Scale for the Measurement of Quality of Life in Children with Intellectual Disability. Res. Dev. Disabil. 2016, 53–54, 399–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blomqvist, S.; Wester, A.; Sundelin, G.; Rehn, B. Test-Retest Reliability, Smallest Real Difference and Concurrent Validity of Six Different Balance Tests on Young People with Mild to Moderate Intellectual Disability. Physiotherapy 2012, 98, 313–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salb, J.; Finlayson, J.; Almutaseb, S.; Scharfenberg, B.; Becker, C.; Sieber, C.; Freiberger, E. Test-Retest Reliability and Agreement of Physical Fall Risk Assessment Tools in Adults with Intellectual Disabilities. J. Intellect. Disabil. Res. 2015, 59, 1121–1129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mac Donncha, C.; Watson, A.W.S.; McSweeney, T.; O’Donovan, D.J. Reliability of Eurofit Physical Fitness Items for Adolescent Males with and without Mental Retardation. Adapt. Phys. Act. Q. 1999, 16, 86–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeoung, B. A Study of Blood Pressure and Physical Fitness in People with Intellectual Disabilities in South Korea. Healthcare 2024, 12, 887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arfken, C.L.; Balon, R. Declining Participation in Research Studies. Psychother. Psychosom. 2011, 80, 325–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graham, L.; Wright, J.; Walwyn, R.; Russell, A.M.; Bryant, L.; Farrin, A.; House, A. Measurement of Adherence in a Randomised Controlled Trial of a Complex Intervention: Supported Self-Management for Adults with Learning Disability and Type 2 Diabetes. BMC Med. Res. Methodol. 2016, 16, 132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oviedo, G.R.; Javierre, C.; Font-Farré, M.; Tamulevicius, N.; Carbó-Carreté, M.; Figueroa, A.; Pérez-Testor, S.; Cabedo-Sanromá, J.; Moss, S.J.; Massó-Ortigosa, N.; et al. Intellectual Disability, Exercise and Aging: The IDEA Study: Study Protocol for a Randomized Controlled Trial. BMC Public Health 2020, 20, 1266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barrett, S.; Begg, S.; Lawrence, J.; Barrett, G.; Nitschke, J.; O’Halloran, P.; Breckon, J.; Pinheiro, M.D.B.; Sherrington, C.; Doran, C.; et al. Behaviour Change Interventions to Improve Physical Activity in Adults: A Systematic Review of Economic Evaluations. Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Act. 2024, 21, 73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clasificaci, P.H.; Activity, P.; Recibido, H.; July, R.; February, A. Physical Activity Promotion: Cost-Utility Study. Rev. Int. Med. Ciencias Act. Física Deport. 2021, 21, 607–621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pellegrini, B.; Boccia, G.; Zoppirolli, C.; Rosa, R.; Stella, F.; Bortolan, L.; Rainoldi, A.; Schena, F. Muscular and Metabolic Responses to Different Nordic Walking Techniques, When Style Matters. PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e0195438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernhall, B.; McCubbin, J.A.; Pitetti, K.H.; Rintala, P.; Rimmer, J.H.; Millar, A.L.; De Silva, A. Prediction of Maximal Heart Rate in Individuals with Mental Retardation. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 2001, 33, 1655–1660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akinwande, M.O.; Dikko, H.G.; Samson, A. Variance Inflation Factor: As a Condition for the Inclusion of Suppressor Variable(s) in Regression Analysis. Open J. Stat. 2015, 05, 754–767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McKeon, M.; Slevin, E.; Taggart, L. A Pilot Survey of Physical Activity in Men with an Intellectual Disability. J. Intellect. Disabil. 2013, 17, 157–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pérez-Cruzado, D.; Cuesta-Vargas, A.I. Changes on Quality of Life, Self-Efficacy and Social Support for Activities and Physical Fitness in People with Intellectual Disabilities through Multimodal Intervention. Eur. J. Spec. Needs Educ. 2016, 31, 553–564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kong, Z.; Sze, T.M.; Yu, J.J.; Loprinzi, P.D.; Xiao, T.; Yeung, A.S.; Li, C.; Zhang, H.; Zou, L. Tai Chi as an Alternative Exercise to Improve Physical Fitness for Children and Adolescents with Intellectual Disability. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 1152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shields, N.; Taylor, N.F.; Wee, E.; Wollersheim, D.; O’Shea, S.D.; Fernhall, B. A Community-Based Strength Training Programme Increases Muscle Strength and Physical Activity in Young People with Down Syndrome: A Randomised Controlled Trial. Res. Dev. Disabil. 2013, 34, 4385–4394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lynch, L.; McCarron, M.; McCallion, P.; Burke, E. An Exploration into Self-Reported Inactivity Behaviours of Adults with an Intellectual Disability Using Physical Activity Questionnaires. J. Intellect. Disabil. Res. 2024, 68, 1396–1407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

González-Devesa, D.; Ayán-Pérez, C.; González-Devesa, E.; Diz-Gómez, J.C. The Effect of Nordic Walking Intervention (NORDIN-JOY) on Individuals with Intellectual Disabilities and Their Families: A Multicenter Randomized Crossover Study. Clin. Pract. 2025, 15, 53. https://doi.org/10.3390/clinpract15030053

González-Devesa D, Ayán-Pérez C, González-Devesa E, Diz-Gómez JC. The Effect of Nordic Walking Intervention (NORDIN-JOY) on Individuals with Intellectual Disabilities and Their Families: A Multicenter Randomized Crossover Study. Clinics and Practice. 2025; 15(3):53. https://doi.org/10.3390/clinpract15030053

Chicago/Turabian StyleGonzález-Devesa, Daniel, Carlos Ayán-Pérez, Eva González-Devesa, and Jose Carlos Diz-Gómez. 2025. "The Effect of Nordic Walking Intervention (NORDIN-JOY) on Individuals with Intellectual Disabilities and Their Families: A Multicenter Randomized Crossover Study" Clinics and Practice 15, no. 3: 53. https://doi.org/10.3390/clinpract15030053

APA StyleGonzález-Devesa, D., Ayán-Pérez, C., González-Devesa, E., & Diz-Gómez, J. C. (2025). The Effect of Nordic Walking Intervention (NORDIN-JOY) on Individuals with Intellectual Disabilities and Their Families: A Multicenter Randomized Crossover Study. Clinics and Practice, 15(3), 53. https://doi.org/10.3390/clinpract15030053