The Construction Site of Tomorrow: Results of 3 Years of Field-Testing Electric Excavators

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

- Residential construction;

- Civil engineering;

- Forestry;

- Demolition works;

- Railway maintenance.

3. Results

3.1. Energy Consumption

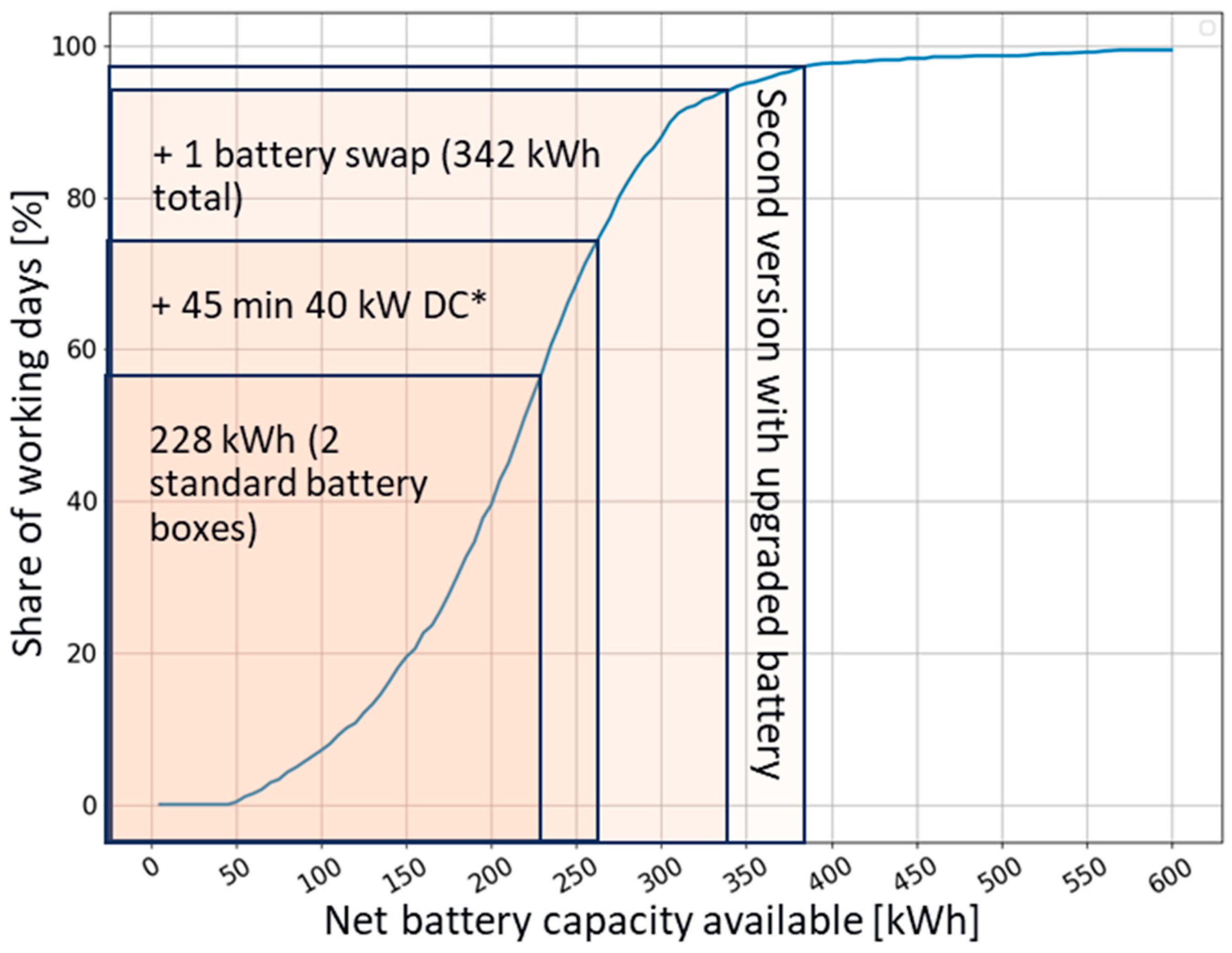

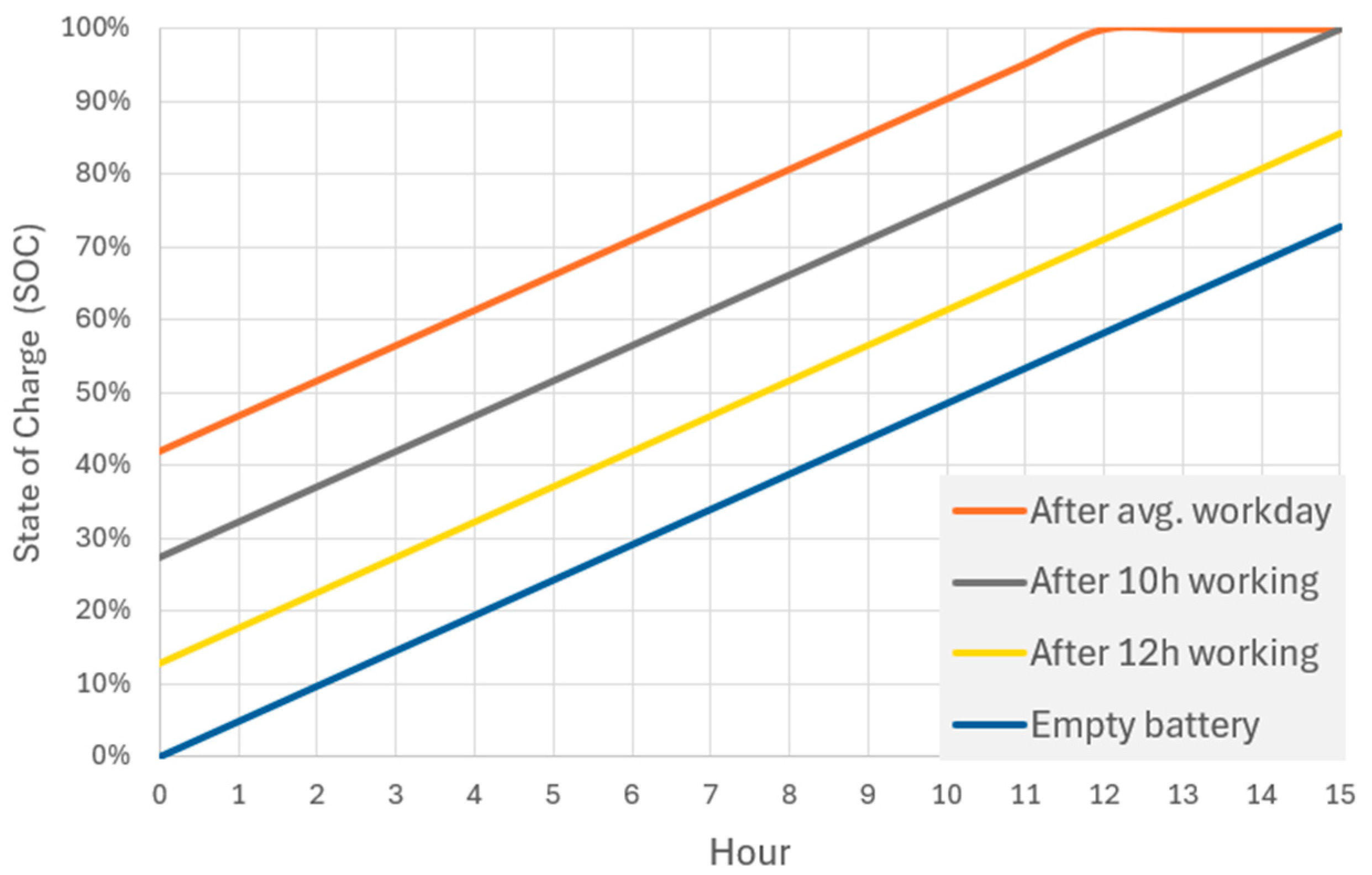

3.2. Usability

3.3. Avoided Emissions

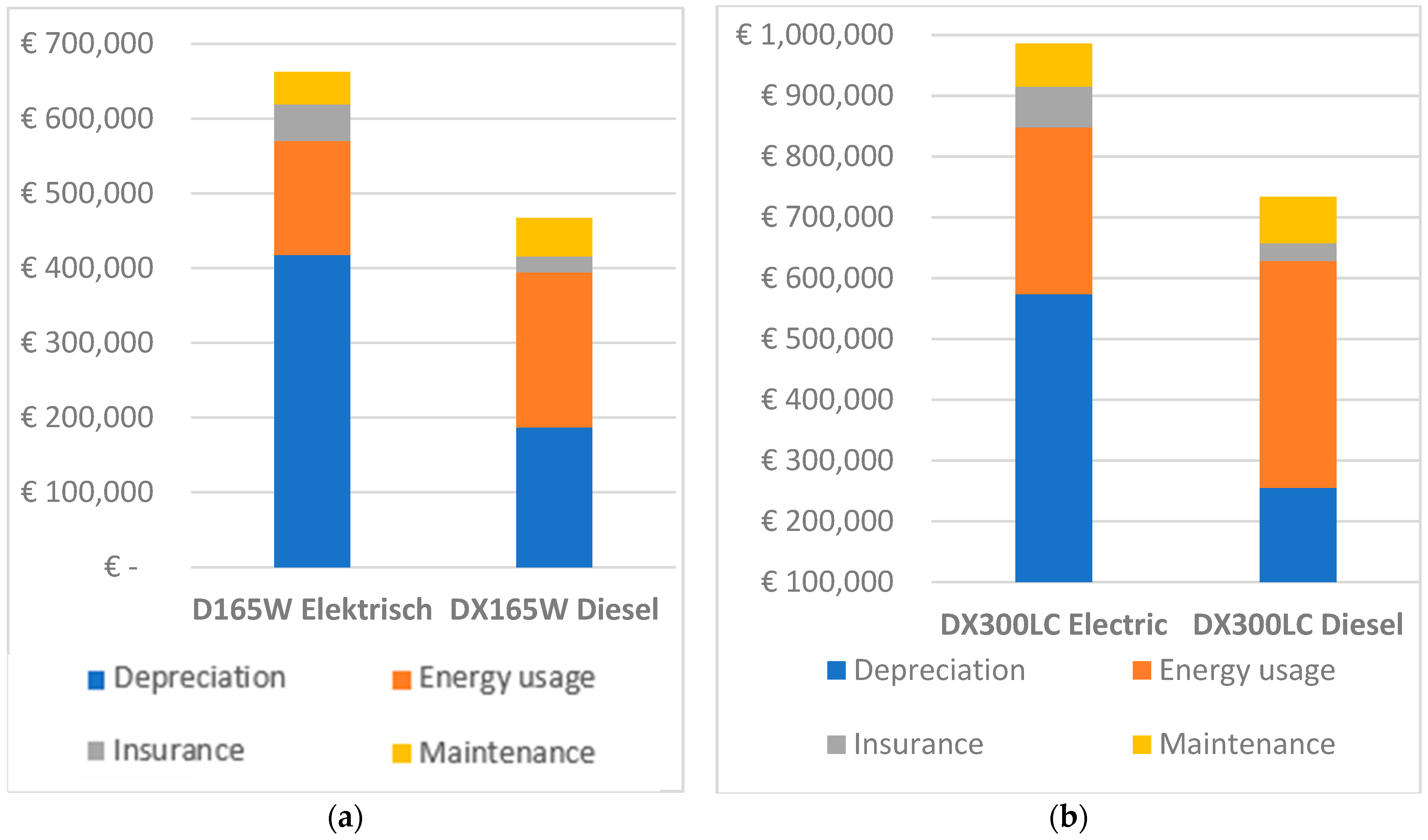

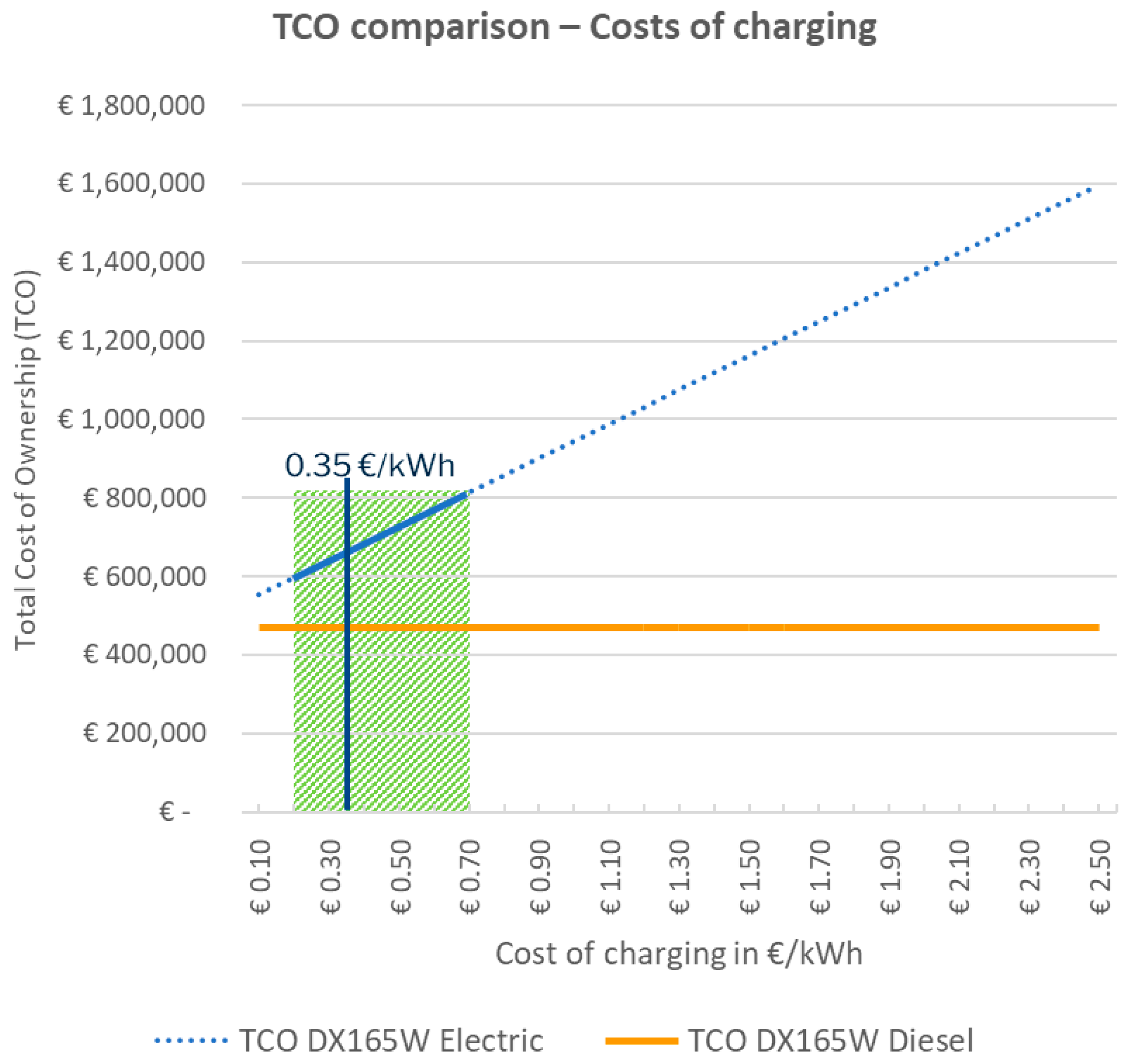

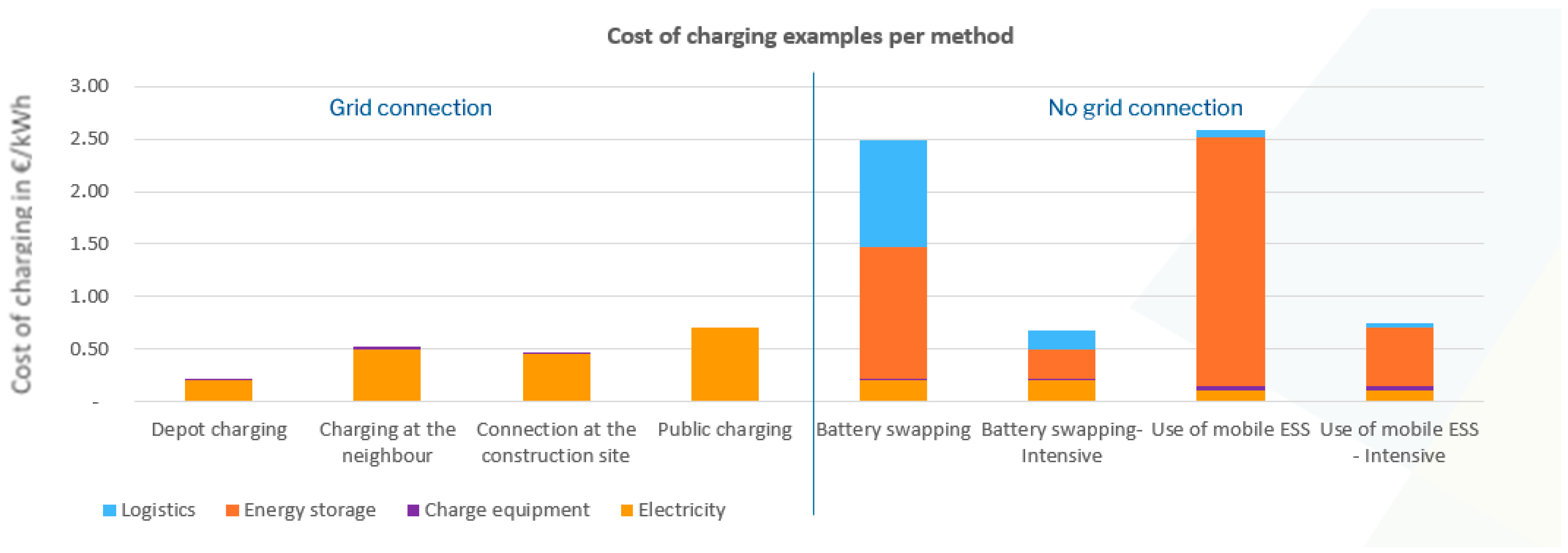

3.4. Total Cost of Ownership (TCO)

4. Conclusions

- The electric excavators have been successfully used in the project “The Construction Site of Tomorrow”.

- The energy consumption per hour is reasonably comparable among the different use cases.

- The number of operating hours per day varies widely. It has been proven to be possible to run double shifts, even with the limited battery capacity of the first-generation batteries, when making use of the battery swap system (and good planning). Using the upgraded batteries of 380 kWh makes this even easier.

- The grid connection on the construction site has to have sufficient capacity to be able to charge the machines overnight, and if necessary, separate swapped-out batteries during the daytime. In the case of long working hours, it can become critical even with 2 × 22 kW (3-phase 64 A per machine).

- The comparative emission measurements point at expected emissions reductions of around 21 tons of CO2 and 114 kg of NOx per year for the mobile excavator, and 34 tons of CO2 and 202 kg of NOx per year for the larger tracked machine.

- When replacing a diesel machine with an electric one, it can be expected that 4 kWh from the grid is needed for every litre of diesel consumed.

- The TCO of electric excavators is considerably higher (34–42%) than that of comparable diesel excavators, given the Dutch situation and the assumptions made.

- Upscaling and technological developments will have a positive impact on the TCO of electric machines in the long term. In this, there is the potential to improve efficiency and therefore reduce the need for large battery capacities. This will result in lower overall machine costs.

- The costs of charging are very much dependent on the local situation. A grid connection is the most cost-effective. If not available, energy storage and/or logistics give rise to higher costs.

- Charging requires organisation and planning. It is attractive in the case of long-running projects and the use of multiple machines.

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Econ. Instituut voor de Bouw. Stikstofproblematiek: Effecten op Realisatie van Bouwprojecten op Korte en Middellange Termijn. 2019. Available online: https://www.eib.nl/publicaties/stikstof-problematiek/ (accessed on 13 September 2025).

- Economisch Instituut voor de Bouw. Nieuwe Stikstofregels: Gevolgen voor de Woningbouw. 2025. Available online: https://www.eib.nl/publicaties/nieuwe-stikstofregels-gevolgen-voor-de-woningbouw/ (accessed on 13 September 2025).

- Economisch Instituut voor de Bouw. Effecten Stikstof op Wegenprojecten. 2024. Available online: https://www.eib.nl/publicaties/effecten-stikstof-op-wegenprojecten/ (accessed on 13 September 2025).

- Fu, S.; Wang, L.; Lin, T. Control of electric drive powertrain based on variable speed control in construction machinery. Autom. Constr. 2020, 119, 103281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mu, H.; Cheng, M.; Tang, X.; Ding, R.; Ma, W. A hybrid distributed-centralized load sensing system for efficiency improvement of electrified construction machinery. Energy 2025, 314, 134123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, J.; Zhang, D.; Liu, C.; Zhao, Y.; Hu, P.; Quan, W. Optimization of electro-hydraulic energy-savings in mobile machinery. Autom. Constr. 2019, 98, 132–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ng, K.-W.; Tong, H.-Y. Comparisons of Driving Characteristics between Electric and Diesel-Powered Bus Operations Along Identical Bus Routes. Sustainability 2024, 16, 4950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, Y.; Fang, W.; Yan, H.; Zhang, W.; Li, Y. An online energy consumption estimation method for different types of battery electric buses based on incremental learning. Energy 2025, 336, 138515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, W.; Han, Y.; Lu, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Ge, Z.; Pan, Y. Prediction of driving energy consumption for pure electric buses using dynamic driving style recognition and speed forecasting. Energy 2025, 329, 136785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meyer, M.; Bousonville, T. Analysis of truck electrification potential based on real-world data, the Science and Development of Transport -TRANSCODE 2025. Transp. Res. Procedia 2025, 91, 107–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Continental UniNOx Sensor Specifications. Available online: https://www.continental-aftermarket.com/en-en/products/small-production-runs-for-special-purpose-vehicles/sensors-switches/uninox-sensor (accessed on 1 June 2025).

- Dieselnet Page on NOx Sensors for Automotive Applications. Available online: https://dieselnet.com/tech/sensors_nox.php (accessed on 13 September 2025).

- Zult, M.; van Gijlswijk, R.; van der Mark, P. De Bouwplaats van Morgen: Resultaten Monitoring Elektrische Graafmachines; TNO Report 2024 P11947; TNO: The Hague, The Netherlands, 2024; Available online: https://publications.tno.nl/publication/34643295/humX67IH/TNO-2024-P11947.pdf (accessed on 13 September 2025).

- Vermeulen, R.; Ligterink, N.; Van der Mark, P. Real-World Emissions of Non-Road Mobile Machinery; TNO Report 2021 R10221; TNO: The Hague, The Netherlands, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Dellaert, S.N.C.; Ligterink, N.E.; Hulskotte, J.H.J.; van Eijk, E. EMMA–MEPHISTO Model–Calculating Emissions for Dutch NRMM Fleet; TNO Report 2023 R12643; TNO: The Hague, The Netherlands, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- van Mensch, P. Real-World NOx-Emissions from Various Non-Road Mobile Machinery and Vehicles; TNO Report 2025 R10466; TNO: The Hague, The Netherlands, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- FIER Sustainable Mobility; Christiaens, W.G.J.; Lamarra, A. Economische Analyse Bouwplaats van Morgen. Available online: https://www.fier.net/projects (accessed on 1 August 2025).

| DX165W | Unit | Civil | Residential | Forestry | Railway Maintenance | Demolition Works |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Average motor power during use | kW | 28.2 | 24.2 | 31.5 | 23.6 | 25.2 |

| Operating hours per working day | Hours | 8.1 | 8.0 | 6.6 | 8.3 | 6.6 |

| kWh/working day | kWh | 227 | 193 | 208 | 208 | 156 |

| Number of working days monitored | - | 1036 | 159 | 202 | 27 | 30 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Published by MDPI on behalf of the World Electric Vehicle Association. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Christiaens, W.; Weken, H.; van Gijlswijk, R.; Zult, M. The Construction Site of Tomorrow: Results of 3 Years of Field-Testing Electric Excavators. World Electr. Veh. J. 2026, 17, 62. https://doi.org/10.3390/wevj17020062

Christiaens W, Weken H, van Gijlswijk R, Zult M. The Construction Site of Tomorrow: Results of 3 Years of Field-Testing Electric Excavators. World Electric Vehicle Journal. 2026; 17(2):62. https://doi.org/10.3390/wevj17020062

Chicago/Turabian StyleChristiaens, Willem, Harm Weken, René van Gijlswijk, and Michiel Zult. 2026. "The Construction Site of Tomorrow: Results of 3 Years of Field-Testing Electric Excavators" World Electric Vehicle Journal 17, no. 2: 62. https://doi.org/10.3390/wevj17020062

APA StyleChristiaens, W., Weken, H., van Gijlswijk, R., & Zult, M. (2026). The Construction Site of Tomorrow: Results of 3 Years of Field-Testing Electric Excavators. World Electric Vehicle Journal, 17(2), 62. https://doi.org/10.3390/wevj17020062