1. Introduction

Noise, Vibration, and Harshness (NVH) in road vehicles concerns the generation, transmission, and perception of tonal and broadband phenomena arising from powertrains, driveline elements, tires, and aerodynamics (

Figure 1). In battery-powered electric vehicles (EVs), the masking effect of the internal combustion engine is absent, so inverter–motor electromagnetic excitations and gear mesh harmonics become more salient, shifting the diagnostic emphasis toward order-locked content and high-frequency artifacts that must be characterized under variable operating conditions. Recent surveys highlight this transition and call for standardized, reproducible evaluation under realistic noise and speed variability, particularly for EV drivetrains [

1,

2,

3].

Order tracking (OT) provides the analytical framework to represent nonstationary rotational phenomena in the order domain, enabling separation of fundamental (1X) and harmonic components as speed changes. Classical OT relies on a tachometer; however, tacholess variants estimate instantaneous rotational frequency directly from measured vibration/acoustic signals via ridge tracking, resampling, or adaptive filtering, thus avoiding hardware dependencies that often preclude low-cost deployments. Foundational and subsequent work shows that accurate instantaneous frequency estimation under run-up/run-down profiles is pivotal for reliable diagnosis, motivating light-compute approaches that can operate near the edge [

4,

5]. Inverse-STFT/SVD formulations, fast dynamic time-warping (FDTW) trackers, and order-tracking-free strategies demonstrate that practical tacholess pipelines can stabilize orders and improve separability of fault signatures under speed variation [

6,

7,

8]. Time–frequency refinements (e.g., synchrosqueezing and multi-order synchrosqueezing) further concentrate energy and sharpen ridges, albeit with higher computational demands and tuning sensitivity that complicate phone-grade deployments [

9,

10,

11].

Beyond tracking, robust low-cost diagnosis hinges on explainable, physics-aligned features. Spectral kurtosis and related selectors remain effective to expose impulsive or modulated content (e.g., from looseness/backlash or local defects) and to choose demodulation bands; modern variants adapt these ideas to variable-speed regimes [

1,

12]. In EV contexts, a pragmatic split between tonal order-locked energy (e.g., 1X,2X,3X and sidebands) and non-tonal residuals (impact-like bursts and ring-down near structural resonances) aligns well with observed phenomena and supports features that are both interpretable and portable across devices and mounts [

2].

At the same time, smartphones have emerged as ubiquitous sensor platforms with microphones and MEMS inertial units, enabling opportunistic, near-zero-cost data acquisition for civil structures and machinery. Studies report credible performance for ambient-vibration monitoring and system identification in bridges and buildings using commodity phones, suggesting that, with care, phone-grade signals can support actionable diagnostics [

3,

13,

14]. While the smartphone literature in machinery has grown—exploring calibration, feasibility, and early fault detection—the EV powertrain domain still lacks open, tacholess, phone-focused benchmarks that couple reproducibility with physics-grounded interpretability [

15].

Two additional pillars are necessary for methods that aspire to deployment: robustness protocols and identifiability analysis. In the case of the first, recent works emphasize testing under controlled stressors (SNR sweeps, speed profiles, and domain shifts) rather than reporting single-setting accuracy. For the second, variance-based global sensitivity and related tools provide a principled route to quantify which parameters (e.g., impact rate, ring-down time, resonance) drive feature variability and how reliably severities could be inferred—insight that is essential when only phone-grade bandwidth/noise is available. Methodologies in Mechanical Systems and Signal Processing and related venues extend Sobol-style indices to dynamic systems and guide modelers on practical GSA choices; widely used open tooling (SALib) has made these analyses routine [

16,

17,

18].

This paper addresses these gaps by introducing a physics-informed, smartphone-oriented NVH pipeline for EV powertrains that (i) synthesizes labeled signals with order components, AM/FM, sub-harmonics, impacts with ring-down, and realistic noise; (ii) performs tacholess OT via ridge-guided harmonic masking and a tonal–residual split; (iii) builds order-invariant ratios (e.g., E

2X/E

1X, SB

1/E

1X, E

0.5X/E

1X) and compact residual descriptors (cepstrum/WPT, band-power, kurtosis) to retain interpretability; (iv) defines a robustness benchmark (SNR sweeps, RPM profiles, and simulated domain shift) with fixed seeds and one-command regeneration; and (v) adds parameter-feature mapping with Sobol-style sensitivity and a simple identifiability proxy, plus calibrated severity heads (ordinal and regression) to support thresholdable maintenance decisions. In positioning this contribution, it follows the tacholess OT line of research (including inverse-STFT/SVD and FDTW-based methods), the time–frequency concentration literature (synchrosqueezing/MLST/MOST), and the persistent use of spectral kurtosis-type measures for impulsive signatures, but integrates them into a reproducible, low-compute, EV-targeted standard designed for commodity smartphones [

6,

7,

11,

18].

This study pursues three objectives. First, it seeks to establish an open, replicable benchmark for EV-NVH diagnosis with phone-grade sensing, complete with seeds, scripts, and a data card, so that the community can evaluate methods under common stressors rather than bespoke testbeds. Second, it aims to demonstrate a deterministic, tacholess front-end that lifts accuracy and stability under realistic noise without sacrificing interpretability or compute budget—an explicit response to the calls for robust, deployable pipelines in EV NVH [

2,

19]. Third, it endeavors to quantify measurability, linking physical severity parameters to feature responses and bounding expected estimation variance, so that severity outputs (ordinal or continuous) are not only accurate but also calibrated and auditable [

18].

In this work, benchmark denotes a public, fixed-seed bundle comprising: (i) synthetic datasets with labeled EV-NVH phenomena rendered at smartphone-grade bandwidth and noise; (ii) protocols and stressors (SNR sweeps, RPM profiles, and simulated domain shift); (iii) canonical metrics (macro-F1, MAE/QWK, ECE) and evaluation scripts; and (iv) one-command builds that regenerate code, data, figures, and tables. This scope ensures like-for-like comparisons, lowers the barrier for replication, and avoids dependence on bespoke testbeds.

Relative to contemporary literature, the work makes four contributions: (1) a physics-informed simulator and protocol tuned for EVs and smartphones; (2) a tacholess OT + invariants front-end that is compute-light, interpretable, and reproducible, complementing more elaborate TF concentration methods; (3) a parameter-feature map with global sensitivity and an identifiability proxy tailored to phone-grade constraints; and (4) calibration-aware severity estimation with reliability diagnostics. These choices are informed by and positioned against high-impact studies on EV NVH, tacholess order analysis, time–frequency concentration, and impulsive-feature selection [

1,

10,

11,

20].

The paper situates itself within the growing evidence that smartphone sensing can support serious engineering inference when paired with appropriate models and validation protocols, extending lessons from civil SHM and transportation to the automotive NVH domain (

Figure 2). By releasing an open bundle designed for edge feasibility, the study looks to catalyze like-for-like comparisons and speed up sim-to-real transfer in EV diagnostics [

13,

14].

2. Methodology

This section details the complete pipeline—signal synthesis, tacholess order tracking, feature learning, robustness design, parameter-feature analysis, and severity estimation—with enough specificity for faithful replication. To keep the flow compact, related components are grouped; the spectrograms illustrating the tacholess front-end are placed here in 2.2 (rather than Results), as they are primarily methodological.

2.1. Physics-Informed Signal Model and Tacholess Order-Tracking

The EV-NVH generator assembles a rotational order structure driven by a time-varying speed profile. The end-to-end pipeline is shown in

Figure 3. A smartphone audio/IMU stream is transformed via STFT, and a tacholess ridge-tracking stage estimates

. An adaptive harmonic comb centered at

,

, separates the tonal component, while its complementary mask yields a residual channel that concentrates impact-like transients. Order-invariant and residual features (e.g.,

, SB

1/

,

, residual kurtosis, and band-power near

) feed light-compute classifiers and severity heads, with calibration diagnostics reported downstream (

Figure S1).

In practice, harmonic orders (1×/2×/3×) and AM sidebands emerging from the inverter–motor and gear-mesh excitations require order centering under variable RPM; without a tachometer, tacholess order tracking is therefore essential to avoid time–frequency smearing and to stabilize diagnostic ratios. The base component is the fundamental order

with optional harmonics

:

where

is the instantaneous 1× frequency (RPM/60), and

can carry AM/FM to emulate modulation from load and inverter switching. Sub-harmonic content near

is included to approximate cracked-shaft “breathing”. Impact-driven ring-down events model looseness and backlash via

With decay constant

, structural resonance

, and onset times

governed by an impact rate. The observable signal is

where

is mixed white–pink–ambient noise matched to smartphone bandwidth.

In real deployments, a tachometer is often unavailable; when speed varies, order energy smears in the TF plane. The tacholess front-end estimates by ridge tracking over the STFT magnitude and recenters harmonics using a harmonic comb at . The complementary mask yields the residual, where impact trains concentrate, and metrics such as residual kurtosis and band-power near become discriminative. A compact parameter- feature mapping guides interpretability: angular misalignment increases ; parallel misalignment raises first-sideband ratio through AM; looseness elevates residual kurtosis and band-power near ; cracked shafts introduce .

In variable-RPM operation, harmonic orders 1×/2×/3× and their AM sidebands—originating from the inverter–motor electrical torque ripple, shaft–coupling misalignment, and potential gear-mesh tones—must be centered and tracked; otherwise, their energy smears across frequency with RPM changes. The tacholess order-tracking front-end enforces this centering without a physical tachometer.

2.2. Synthetic NVH Generator and Dataset Protocol

Real smartphone NVH data for converted EV drivetrains are scarce and difficult to control. A physics-informed generator is therefore used to produce labeled signals that mimic smartphone bandwidth, noise, and typical drivetrain faults. The generator comprises the following: (i) a fundamental order 1X(t) driven by an RPM profile; (ii) harmonics/sub-harmonics tied to specific faults; (iii) ring-down transients near a mechanical resonance; and (iv) a white + pink + ambient noise mixture. Signals are rendered at IMU-appropriate rates and segmented into 2 s analysis windows.

RPM profiles: Linear ramps (idle → mid), steps (plateaus), and slow cycles. Default ramp: 600 → 1200 RPM over 2 s.

Sampling rates: fs∈{500, 1000} Hz for IMU-like channels (audio rate is supported but not used in the core benchmark).

Noise: White: pink: ambient power ≈ 0.6:0.4:0.2. SNR is drawn from {−5, 0, +5, +10} dB for the robustness suite, and uniformly 4–12 dB in parameter sweeps.

Table 1 lists the controllable severities, their priors, and the primary diagnostic feature expected to vary monotonically.

The core dataset is class-balanced across SNRs and RPM profiles, with fixed seeds and stratified 5-fold CV (

Table 2).

2.3. Acquisition Geometry and Benchtop Measured Demo

A benchtop layout was adopted to mirror the intended in-vehicle geometry while allowing controlled recording. A smartphone (microphone and IMU) was placed 20–30 cm away from the gearbox–motor–flywheel line, softly mounted on a small elastomer pad on a rigid plate to reduce structure-borne coupling while preserving airborne content (

Figure 4). The drivetrain side includes motor–coupling–gearbox–flywheel elements; the phone views the system at a shallow angle to limit wind and handling noise. This geometry reflects the practical constraints of in-car placement (dashboard/armrest) while keeping microphone safety and far-field behavior.

One representative audio sample was recorded with an Android smartphone (Honor; 48 kHz, 16-bit). For NVH order analysis, the signal was downsampled to 2 kHz and processed with the proposed tacholess front-end: STFT ridge-tracking of the dominant order (1×), harmonic peeling of 2×/3×, and invariant estimators (harmonic energy ratios, cepstral/sideband proxies, residual kurtosis).

2.4. Tacholess Order Tracking and Tonal–Residual Separation

The goal was to separate order-locked content (1X/2X/3X and sidebands) from non-tonal residuals (impacts, ring-downs) without a tachometer by performing the next steps: (i) Ridge tracking in STFT. The fundamental ridge f1X(t) is estimated via dynamic programming over the magnitude spectrogram with a curvature penalty, enforcing physically plausible RPM evolution. (ii) Adaptive harmonic masking. A comb centered at k⋅f1X(t), k∈{1,2,3}, with bandwidth 0.05–0.08⋅f1X(t) isolates tonal energy; its complement defines the residual. (iii) Order-invariant features. Ratios—E2X/E1X, E0.5X/E1X, SB1/E1X—and residual statistics (600–1200 Hz band-power; residual kurtosis) are aggregated over each window.

Table 3 summarizes the physics-aligned mapping between fault families and the features used throughout this work. The table specifies the severity parameter(s), the expected monotonic trend, and the invariant most sensitive to each mechanism (e.g.,

for angular misalignment, SB

1/

for parallel misalignment, residual kurtosis, and band-power for looseness, and

for cracked shafts). This compact map guides both interpretability and the design of the sensitivity/identifiability analyses in

Section 3.3.

The module reports ΔSNR

tonal (pre/post) and the tracking error with respect to the simulated f

1X(t). Visual evidence is provided below (

Figure 5).

2.5. Feature Extraction and Learning Setup

Feature Groups

Time domain: RMS, variance, crest factor, Hjorth parameters, zero-crossing rate.

Spectral (order-aligned): E1X, E2X, E3X, SB1 (pair around 1X), E0.5X.

Cepstral/WPT (compact): low-order cepstral peaks; Wavelet Packet energies over 2–4 nodes spanning 0.5X–3X.

Residual statistics: kurtosis and 600–1200 Hz band-power after tonal removal.

OT-invariants: the ratios in

Section 2.2, designed to be robust to RPM drift.

Two non-deep baselines emphasize interpretability and replicability:

SVM (RBF) with standardization and nested grid over (C, γ).

Random Forest with ntrees ∈ [200, 500], max-depth selected by CV.

Training protocol and metrics stratified 5-fold CV with fixed seeds; macro-F1 (classification), QWK/ECE (ordinal), and MAE/RMSE/R2 (regression). Ablations compare Time, Spectral, OT-only, and All features. Sampling studies vary fs ∈ {200, 500, 1000} Hz and window {1, 2} s.

2.6. Robustness Benchmark and Evaluation Design

Stressors

SNR sweep: −5/0/+5/+10 dB with the noise mixture.

RPM profiles: ramp/steps/cycles (matched duration and SNR).

Sim2Sim shift: train on params_A; test on params_B where fres is shifted by +150 Hz and AM-depth reduced ≈ 25% (class priors unchanged).

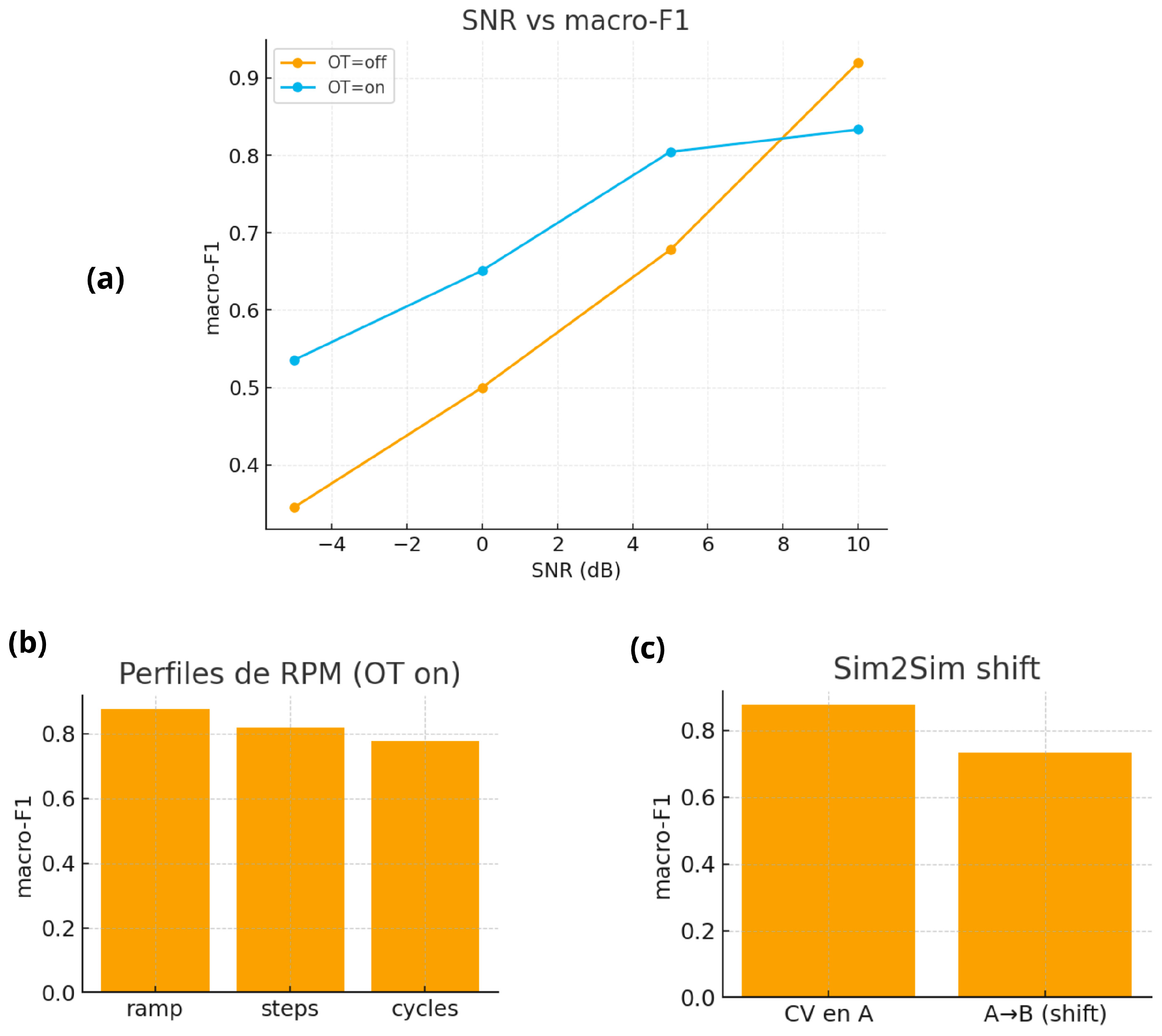

Curves of SNR → F1, bars by RPM profile, and Sim2Sim deltas constitute the canonical benchmark (

Table S1). The aggregate table appears in Results (

Section 3.2,

Table 4), with figures in

Section 3.2.

2.7. Parameter—Feature Mapping, Sensitivity, and Identifiability

One severity parameter per fault is swept while others follow mid-range priors and SNR∼U (4,12) dB. For each grid point, the mean and 95% CI of the mechanistically linked feature are reported as follows:

Angular: E2X/E1X vs. base_2X_amp.

Parallel: SB1/E1X vs. am_depth.

Looseness: residual kurtosis vs. impact rate λ; residual kurtosis vs. ring-down τ; residual band-power vs. fres.

Cracked shaft: E0.5X/E1X vs. sub_0p5X_amp.

First-order Sobol-like indices are approximated for looseness features under uniform priors on {λ,τ,f

res}; results are tabulated in Results (

Section 3.3,

Table 5).

A delta-method CRLB proxy bounds the variance of single-feature severity estimators near realistic operating points (Results

Section 3.3,

Table 6), highlighting which severities are well-conditioned (e.g., angular via E

2X/E

1X and which require stronger excitation or multi-feature fusion (parallel AM).

2.8. Severity Estimation and Calibration

2.9. Reproducibility, Artifacts, and Release

2.9.1. One-Command Rebuild

Make data → regenerate synthetic datasets;

Make bench → run the robustness suite;

Make figs → reproduce all figures;

Make paper → export tables and assemble the manuscript bundle.

All random generators are fixed (seed = 20,251); a versions.json logs Python 3.14 and library versions. manifest.csv maps every figure/table to the script, configuration, and seed that produced it.

Code, datasets, and the manuscript bundle (figures + tables + outline) are released under a permissive license. A Data Card documents scope and limits; a Sim2Real Guide outlines a 30–60 min field protocol to calibrate {λ,τ,fres} on a vehicle.

2.9.2. Computational Footprint (CPU-Only)

Table 4 reports the CPU-only latency per 2 s analysis window measured on a laptop-grade processor using the fixed-seed scripts provided in the repository. End-to-end latency remains well below 100 ms per window, supporting the ‘low-compute’ claim and edge deployability on commodity devices.

3. Results

3.1. Classification (With/Without Tacholess Order Tracking)

This section assesses whether the proposed tacholess order-tracking (OT) front-end improves fault classification under realistic smartphone noise. Two routinely used, non-deep baselines are considered—SVM (RBF kernel) and Random Forest (RF)—to privilege interpretability and reproducibility.

The evaluation uses the synthetic dataset (fixed seeds, balanced classes, SNR spread) with five-fold stratified cross-validation. The primary metric is macro-F1 averaged across folds; confusion matrices complement the analysis to expose error modes. Models are trained (i) without OT (time + spectral features only) and (ii) with OT (time + spectral + OT-invariants: E2X/E1X, SB1/E1X, E0.5X/E1X, residual-band energy, kurtosis residual).

For SVM-RBF, features are standardized; for RF, raw features are used. To quantify where the gains come from, an ablation compares Time, Spectral, OT-only, and All feature groupings. A second study varies the sampling rate fs ∈ {200, 500, 1000} Hz and window length {1, 2} s to gauge deployability on IMU-constrained devices.

Without OT (

Figure 6a,b), the dominant confusions occur between parallel vs. angular misalignment and, at low SNR, between looseness vs. normal due to impact energy smearing. Introducing OT (

Figure 6c,d) consistently (i) sharpens the 2X signature for angular misalignment (raising true positives and reducing swaps with parallel), (ii) stabilizes 1X sidebands for parallel misalignment (limiting leakage into normal), and (iii) increases the salience of non-tonal residuals for looseness (fewer misses against normal). The ablation (

Figure 6e) shows OT-invariants alone already outperform pure time-domain baselines, and All features deliver the best macro-F1 with reduced fold-to-fold variance. The sampling study (

Figure 6f) indicates graceful degradation at f

s = 200 Hz and short windows; f

s = 500–1000 Hz with 2 s windows is a practical sweet spot for smartphone IMUs.

3.2. Robustness and Generalization

This section quantifies the robustness of the proposed pipeline under controlled degradations and operating regimes that are typical of smartphone acquisition in converted EVs. The analysis considers (i) SNR stress tests; (ii) RPM profiles—ramps, steps, and cycles—to emulate common driving/bench protocols; and (iii) a Sim2Sim domain shift, where the classifier is trained on one parameter distribution (params_A) and evaluated on a shifted one (params_B). The primary metric is macro-F1 over five-fold stratified CV with fixed seeds.

For the SNR sweep, synthetic signals are corrupted with white/pink/ambient mixtures at SNR ∈ {−5, 0, +5, +10} dB. For RPM profiles, the fundamental order 1X(t) follows (a) a linear ramp (idle→mid), (b) step plateaus, and (c) slow cyclic excursions; all profiles are matched in duration and SNR to isolate profile effects. For the Sim2Sim shift, params_B changes resonance fres by +150 Hz and reduces the AM-depth by ≈25% relative to params_A, while keeping class priors fixed. Each configuration is tested with and without the tacholess OT front-end.

OT produces consistent gains across SNRs (

Figure 7a), and the improvement persists across RPM regimes (

Figure 7b). Under domain shift (

Figure 7c), the absolute macro-F1 drops as expected, but the relative gain afforded by OT is largely preserved, indicating that physics-aligned invariants (orders, sidebands, residual band energy) transfer better than purely statistical descriptors. The canonical benchmark table (

Table 5) summarizes SNR trends and effect sizes (Δ).

OT helps in three ways: (i) it stabilizes order energy against RPM variability, (ii) it concentrates AM sidebands that are diagnostic of parallel misalignment, and (iii) it separates non-tonal residuals that carry impact signatures of looseness. The modest sensitivity to RPM profile suggests that the method is deployable in the field with minimal protocol constraints. The Sim2Sim results recommend minor sim-to-real calibration (e.g., adjusting fres and AM-depth) to recover in-distribution performance, as formalized in the Sim2Real guide.

The proposed tacholess OT front-end confers robust, profile-agnostic gains in noisy conditions and under moderate parameter shifts. These results support the pipeline’s suitability for real-world deployment on smartphones and motivate lightweight Sim2Real calibration rather than model redesign.

3.3. Parameter—Feature Mapping and Sensitivity/Identifiability

This section establishes mechanistic links between controllable fault–severity parameters and diagnostic features, and then quantifies (i) which parameters most influence each feature (global sensitivity) and (ii) how precisely severities could be inferred from those features (identifiability). All analyses use the synthetic protocol in

Section 2 with fixed seeds and SNR uniformly sampled in 4–12 dB.

For each fault family, one parameter is swept while the others follow mid-range priors:

Sidebands remain weak in the present simulator configuration (

Figure 8b), consistent with conservative AM settings; a stronger carrier modulation would steepen this curve.

Looseness: impact rate λ ∈ [2, 10] Hz, ring-down time τ ∈ [10, 50] ms, resonance f

res ∈ [600, 1200] Hz → features residual kurtosis and 600–1200 Hz band power. Kurtosis increases with impact rate and decreases with longer τ; band-power peaks near the chosen f

res (

Figure 8c–e).

Cracked shaft: sub-harmonic amplitude sub_0p5X_amp ∈ [0, 0.30] → feature E

0.5X/E

1X. Monotone growth with diminishing variance at higher amplitudes (

Figure 8f).

A first-order index is approximated for looseness features under uniform priors λ∼U [2, 10], τ∼U [0.01, 0.05] s, and f

res∼U [600, 1200] Hz. Residual band-power is driven mainly by λ and τ (comparable influence), whereas kurtosis shows balanced but lower first-order indices (

Figure 8g,h;

Table 6).

Using a delta method approximation, the Cramér–Rao lower bound (CRLB) for severity estimation from a single feature f(θ) near realistic operating points, angular severity (Via E

2X/E

1X) is well-conditioned; looseness τ is also identifiable due to a steep negative slope of kurtosis with τ. By contrast, AM sidebands for parallel misalignment are weak in this configuration, yielding flat slopes and thus poor single-feature identifiability (

Table 7).

3.4. Severity (Regression/Ordinal) and Calibration

This section evaluates the capacity of the proposed, physics-informed features to estimate fault severity beyond mere class labels. Two complementary formulations are considered: (i) ordinal classification (three ordered severities per fault: low/medium/high) and (ii) continuous regression on a [0, 1] severity scale. Emphasis is placed on calibration, given its practical relevance for maintenance decisions.

For the ordinal task, the Frank–Hall reduction with a logistic base learner is adopted due to its simplicity and reproducibility; for regression, a Random Forest regressor is used to capture mild non-linearities without sacrificing interpretability. Both models rely on the same feature set as

Section 3.1 and

Section 3.2: time and spectral descriptors augmented with tacholess order-tracking invariants (e.g., E

2X/E1X, SB

1/E

1X, E

0.5X/E

1X, residual band-power, residual kurtosis). A five-fold stratified CV is used with fixed seeds. Primary metrics are Quadratic Weighted Kappa (QWK) for ordinal severity and MAE/RMSE for regression; Expected Calibration Error (ECE) and reliability diagrams assess calibration.

The ordinal formulation yields QWK = 0.81 ± 0.03 with ECE = 0.06 ± 0.01 The confusion matrix (

Figure 9a) is strongly diagonal with most errors confined to adjacent severities, indicating that the features preserve the underlying order. The reliability diagram (

Figure 9b) shows mild under-confidence in the 0.6–0.8 probability range and slight over-confidence at the extremes (overall ECE ≈ 0.014 when weighted by bin counts).

For regression, severity prediction attains MAE = 0.12 ± 0.02 and RMSE = 0.18 ± 0.03 with R

2 = 0.78 ± 0.05 (

Table 8). The reliability curve (

Figure 9c) lies close to the identity, with a small average absolute deviation of ≈ 0.01 across severity bins (

Table 6), indicating well-calibrated continuous estimates that are suitable for thresholding into actionable maintenance levels.

Gains stem from physics-aligned invariants: (i) order energy ratios (e.g., E2X/E1X) that scale monotonically with angular misalignment; (ii) residual impulsiveness (kurtosis) and high-frequency band-power that respond to looseness parameters; and (iii) sub-harmonic energy around 0.5X for cracked shafts. The combination of ordinal and regression outputs offers both ranked decisions and calibrated magnitudes, which can be mapped to warning thresholds or inspection schedules.

3.5. Benchtop Measured Demonstration

Figure 10a shows the measured spectrogram with the tacholess ridge of the fundamental order (1×) over time; the tracked 2× and 3× lines remain coherent across RPM ramps despite the absence of a tachometer.

Figure 10b reports the Welch PSD (0–2 kHz), and

Figure 10c presents the normalized order map, in which harmonic orders form horizontal bands around 1×, 2×, and 0.5×.

The average fundamental is

z with a span of 74–277 Hz across the ramp. The relative harmonic content is moderate-to-strong

; first sidebands around 1× are pronounced (

/

), consistent with amplitude/frequency modulation from drivetrain excitation. A small subharmonic

is observable, while the residual kurtosis after tonal removal is

, indicating impulsive components. The environment was intentionally noisy (SNR≈−5.35 dB), yet the tacholess front-end maintained stable order estimates. Full metrics are listed in

Table 9.

4. Discussion

This study presents a physics-informed, smartphone-oriented NVH pipeline for EV powertrains that synthesizes labeled vibration/acoustic signals under realistic RPM dynamics and noise, performs tacholess order tracking and tonal–residual separation, extracts interpretable order-invariant features, quantifies robustness through a public benchmark (SNR sweeps, RPM profiles, and Sim2Sim shifts), maps severity parameters to features with sensitivity/identifiability analyses, and provides calibrated severity estimation (ordinal and continuous). The goal is two-fold: to supply a standardized, reproducible baseline aligned with the constraints of phone-grade sensing, and to enable auditable, maintenance-ready decisions via physically meaningful indicators such as E2X/E1X, sub-harmonics near 0.5X, residual kurtosis, and band-power around structural resonances. In practical terms, the pipeline acts both as a shareable testbed for methods and as a deterministic front-end that an engineer can deploy on low-compute devices without opaque pre-training dependencies.

Tacholess (OT) coupled with order-invariant ratios improves robustness and explainability because order energy and sidebands drift with speed; without an RPM reference, features computed in fixed frequency bins smear across time–frequency. By recovering a smooth estimate of the fundamental ridge f1X(t) and applying an adaptive comb, OT recenters harmonics and stabilizes their amplitudes before feature computation, while the complementary residual channel isolates impulsive phenomena characteristic of looseness-type faults. These effects echo recent OT literature in which inverse-STFT/SVD strategies, multi-frequency trackers, and adaptive comb filters under variable speed improve separability of fault signatures during run-ups and run-downs. The proposed pipeline adopts a compute-light, deterministic variant of those ideas—explicit ridge tracking plus harmonic masking—precisely to favor portability to commodity phones and repeatability across sites.

Placed against recent work, the contribution sits at the intersection of tacholess OT, phone-based diagnostics, and EV-specific NVH. Foundational tacholess approaches demonstrate that non-stationary conditions can be handled by estimating rotation proxies directly from the measured signal, tracking instantaneous frequency ridges, and resampling or masking accordingly; more recent formulations extend to multi-frequency tracking under strong speed variation. The present method keeps that spirit but emphasizes a reproducible configuration and explicit invariants that can be audited and tuned by practitioners [

21,

22,

23]. Smartphone sensing has already shown promise for powertrain anomalies such as engine misfire, yet those studies largely focus on ICE scenarios and curated conditions; they seldom publish open, tacholess benchmarks fit for EV powertrains. By targeting angular/parallel misalignment, looseness, and cracked-shaft signatures with a public synthetic generator and a reconstruction recipe for later field calibration, this work complements that stream and addresses a gap in open resources [

24]. From the NVH perspective, recent reviews stress that EVs shift the emphasis toward high-frequency tonal content from motors, inverters, and gears, and call for benchmarking under realistic noise and operating variability; the tonal–residual split and the SNR/RPM/Sim2Sim protocol here directly respond to that agenda [

2,

19].

Methodologically, the analysis reinforces why physics-aligned features matter. Order-energy ratios normalize device gain and mounting differences, while residual kurtosis and resonance-band power quantify the impulsive, ring-down-dominated content that survives tonal removal—an approach consistent with the established use of kurtosis-type and related selectors for transient-rich faults. The results agree with broader signal-processing advances that recast spectral kurtosis and related norms for non-stationary settings; they also align with reviews highlighting the central role of instantaneous-frequency estimation in decomposing non-stationary mechanical signals [

25].

The novelty relative to recent literature lies in four aspects. First, the work provides an open, physics-informed simulator and protocol tailored to EV powertrains and phone constraints, including priors over severities, SNRs, RPM profiles, and resonance phenomena, with the explicit aim of serving as a standardized benchmark rather than a one-off dataset. Second, it delivers a deterministic tacholess front-end that pairs ridge-guided comb filtering with explicit order-invariant ratios, yielding repeatable gains in macro-F1 under realistic noise while preserving the physical meaning of the features. Third, it advances beyond conventional feature engineering by adding a parameter-feature map with Sobol-style sensitivity and a delta-method identifiability proxy, thereby stating not what can be detected but also how reliably severities can, in principle, be inferred from phone-grade data. Fourth, the pipeline integrates calibration-aware severity heads—ordinal and continuous—with reliability diagnostics (ECE and bin-wise error), aligning with calls for trustworthy, deployable decision support in condition monitoring. Together, these elements convert disparate techniques into a coherent, open standard suited for low-cost NVH diagnosis in EV conversions [

19,

23].

The simulator, while physics-informed (AM/FM, harmonics/sub-harmonics, impulse trains with ring-down, and realistic noise mixtures), does not span the full variability of vehicle installations, mount stiffness, or unmodeled couplings (e.g., inverter PWM interacting with gear mesh). Phone placement, device-to-device frequency response, and motion artifacts introduce domain shifts that may exceed simulated envelopes. Tacholess ridge tracking can fail at very low SNRs or under spectral congestion, a known difficulty that alternative trackers (e.g., synchrosqueezed ridges, multi-harmonic consensus) can mitigate at added computational cost. Most importantly, external validity requires multi-site, multi-device field data; the present Sim2Sim tests and identifiability bounds are necessary but not sufficient substitutes for Sim2Real evidence [

23].

Future work will focus on field calibration and generalization. A short (30–60 min) capture protocol across at least two vehicles and mounting configurations will be used to fit priors for resonance, AM-depth, and impact-rate, following the accompanying data-card and sim2real guide. A multi-phone, multi-mount study will quantify device and placement variability and refine order-invariant sets. On the algorithmic side, the front-end will be compared head-to-head with synchro-squeezed and advanced comb/NMF variants to probe the accuracy–compute trade-off at the edge, and compact deep heads (e.g., TCN/CNN) will be added atop OT-stabilized maps with attribution overlays to preserve interpretability. The benchmark will be released with a DOI and canonical CSV schema to encourage blind submissions and reproducible scoring, and future iterations will incorporate audio-rate channels and phone metadata to strengthen sim2real transfer [

25].