Review of Emerging Hybrid Gas–Magnetic Bearings for Aerospace Electrical Machines

Abstract

1. Introduction

- At startup and low speeds (<1000 rpm), the magnetic bearing component actively levitates the rotor (since a gas film is not yet established);

- At high speeds (>10,000 rpm), the gas film supports most of the load with minimal power loss, while the magnetic bearing can either offload or provide damping and stability control;

- At medium speeds (1000–10,000 rpm), both gas and magnetic bearings contribute to performance to some extent;

- In case one component fails or becomes insufficient (e.g., magnetic system fault or gas film collapse during a shock), the other can temporarily back up the rotor support, greatly improving reliability.

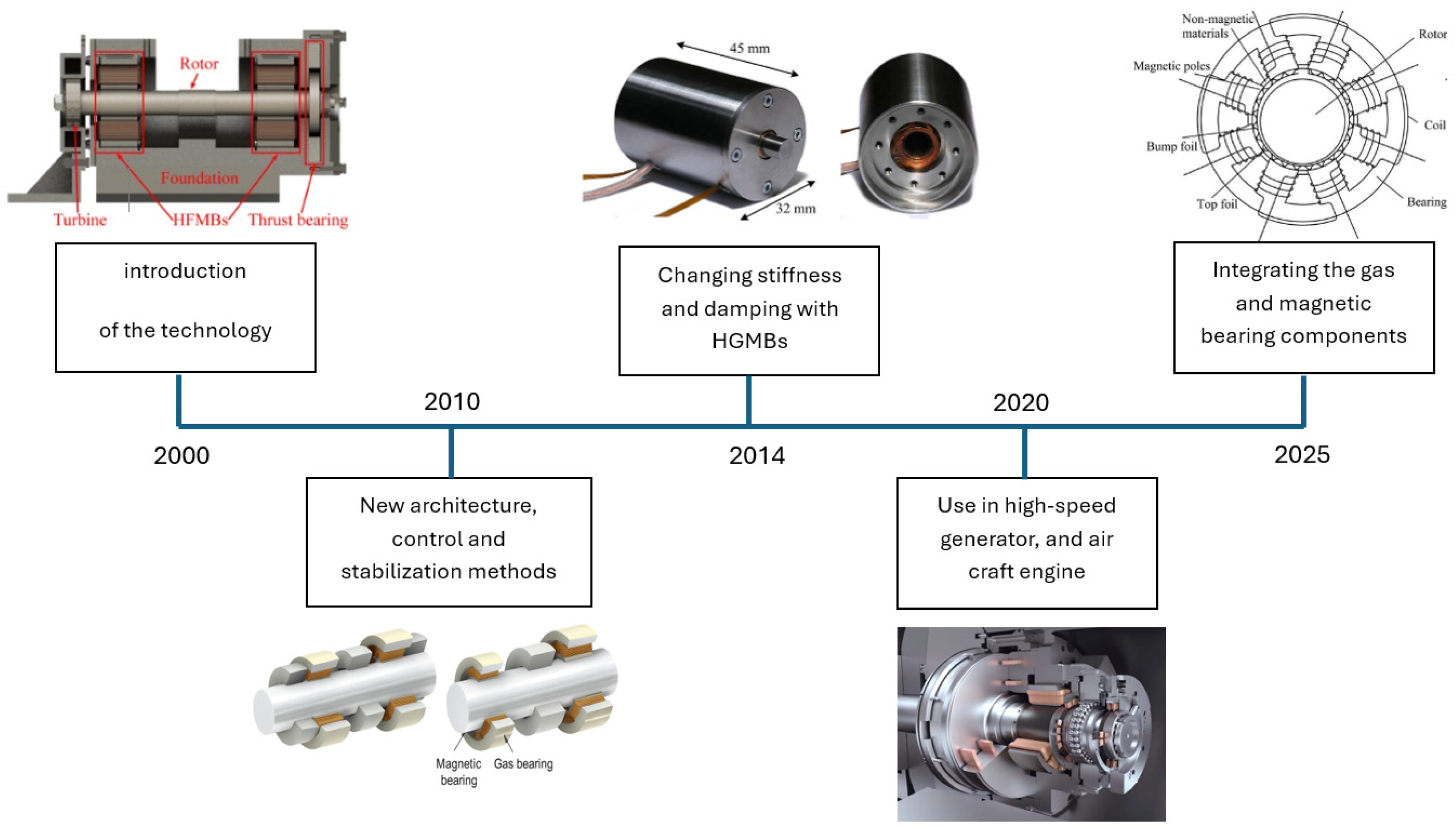

2. Historical Overview of HGMB Development

- -

- In the 2000s: Advances in foil air bearings and AMBs laid the groundwork for hybridization. By 2000, Heshmat et al. [1] reported that merging foil (gas) bearings with magnetic bearings was possible and extremely attractive, envisioning a bearing that takes advantage of the strengths of each while minimizing each other’s weaknesses. Early theoretical studies proposed active control of foil bearings and the idea of magnetic augmentations to improve stability. Swanson et al. [2] built and tested a hybrid foil-magnetic bearing for a small turbine engine rotor (31–53 kN thrust class). In tests, the velocity reached up to 30,000 rpm, and the hybrid bearing shared the rotor load between a compliant airfoil journal bearing and an active magnetic bearing. At 22,000 rpm, the hybrid bearing carried over 5300 N of load. Notably, this tripled the load capacity compared to the AMB alone, demonstrating the huge load advantage of adding a gas bearing. A custom control algorithm adjusted the magnetic force to actively tune load sharing. The rotor ran stably with small vibrations, and when the magnetic coils were deliberately shut off, the foil bearing alone safely supported the rotor at full speed until a controlled coast-down was executed. This experiment proved the feasibility of HGMBs for high-speed turbomachinery and their fail-safe potential. Following the initial success, hybrid bearing research continued, especially in contexts requiring oil-free operation and oil-free turbomachinery applications. In 2002, a refined version of the hybrid bearing was published [3], confirming the earlier Turbo Expo results and garnering wider attention (cited by dozens of subsequent works). In 2003 [49], a large 150 mm diameter hybrid foil-magnetic bearing was experimentally investigated for heavy-duty turbomachines, further demonstrating scalability. Meanwhile, active magnetic bearings alone had begun seeing use in specialized aerospace applications like control moment gyroscopes and rocket engine turbopumps. Pushing the need for fault-tolerant designs and highlighting the appeal of hybrid backup support.

- -

- In the 2010s: Control Integration and New Architectures. Research in the 2010s addressed the rotor dynamic stability issues of gas bearings by leveraging magnetic actuators as dampers. For instance, Looser et al. in 2014 [48] developed an active magnetic damper to stabilize a high-speed rotor on gas bearings, effectively a form of hybrid support where the magnetic system provides damping. They found that by tuning the magnetic bearing’s control stiffness, they could suppress the rotor vibration modes that pure gas bearings struggled with. By the late 2010s, several patents on air-foil magnetic hybrid bearings and numerous prototypes had emerged, indicating growing maturity. However, these systems often used a “nested” configuration, the magnetic bearing and foil bearing were separate components arranged in the same housing or one inside the other, which increased complexity and size.

- -

- In the 2020s: Recent Developments. The past few years have seen a surge of interest in HGMBs, driven by the needs of cryogenic electrical machines, high-speed generators, and hydrogen economy applications. Liu et al. in 2021 [46] published an extensive review summarizing the state-of-the-art in HGMB theory, simulations, and experiments up to 2020. They highlighted inherent challenges in design, analysis, and control that needed to be solved for reliable operation. Building on this, researchers have proposed single-structured HGMBs, where a single device acts as both a gas and magnetic bearing, eliminating duplicate components. Falkowski et al. in 2022 [45] present a detailed study on the design of magnetic bearings specifically for electric jet engine rotors. By 2024, Liu et al. [50] introduced a single-structure HGMB tailored for high-speed cryogenic turboexpanders, such as hydrogen liquefaction turbines. This design integrates the magnetic poles as the journal for the gas bearing, drastically simplifying the assembly and raising the system’s critical speeds. The proposed HGMB design used one bearing at each end of the rotor, each bearing being both magnetic and gas journal. Simulation and analysis verified that the design could support the rotor throughout its operating map and offered simpler construction and higher critical speeds than an equivalent foil bearing design. Ha et al. in 2024 [51] investigated the application of an Integrated Hybrid Air-Foil Magnetic Thrust Bearing (i-HFMTB) in a 250 HP air compressor system. Their work demonstrated that conventional air-foil journal bearings often suffer from rigid-mode instabilities, such as sub- and super-synchronous vibrations, which can limit system performance and reliability. By combining the passive load-supporting capacity of air-foil bearings with the active vibration control of magnetic bearings, the i-HFMTB successfully suppressed these instabilities. Concurrently, advanced modeling in 2025 quantified the performance trade-offs (like clearance effects) to guide HGMB optimization. These latest works mark a transition of HGMBs from experimental novelty towards practical design methodologies for aerospace applications. Figure 2 shows some information about the number of papers and countries that conducted the studies on HGMBs in aerospace motors.

3. Design Principles of Gas, Magnetic, and Hybrid Bearings

3.1. Principles and Performance of Gas Bearings

3.1.1. Hydrodynamic Gas Bearings

3.1.2. Hydrostatic Gas Bearings

3.2. Principles and Performance of Magnetic Bearings

- I

- Zero-Friction, Active Control: Because there is no physical contact, friction is eliminated, and there is no need for lubrication. This yields potentially unlimited life (no wear) and no contamination, critical for high-purity or vacuum environments (e.g., oxygen turbopumps, space applications). An AMB system continually monitors rotor position (usually with eddy-current sensors) and adjusts currents to maintain stability [45]. This active control can also deliberately adjust stiffness and damping by feedback gains, allowing tunable rotor support. For instance, an AMB can be made “softer” or “stiffer” in real-time operations, and can inject damping to quench vibrations [3]. Such capability is impossible in passive bearings and is very attractive for managing critical speeds and transient loads.

- II

- Load Capacity and Bias Currents: Magnetic bearing load capacity depends on magnetic flux, limited by material saturation and heating [4]. Bias currents linearize force but cause continuous power loss, while zero-bias designs reduce losses at the cost of nonlinearity and lower stiffness [3]. Compared to gas bearings, AMBs are less stiff, allowing the rotor to “float,” which can be advantageous by lowering critical speeds and promoting self-centering, thus widening the stable operating range.

- III

- Auxiliary Systems: An AMB setup demands a control system, power electronics, and backup bearings. The control hardware monitors sensor signals and drives the actuator coils. If the magnetic power or control fails, the rotor must safely coast on backup (usually rolling element) bearings [2], which are only engaged in emergencies. This need for redundant support and continuous power is a disadvantage of magnetic bearings in aerospace applications, where a sudden power loss could cause loss of support. However, in a well-designed system, magnetic bearings have been shown to handle rapid dynamic loads and shock inputs better than mechanical bearings, because the active control can react to disturbances [46]. They have been researched for decades and are now used in niche but critical applications, such as satellite reaction wheels, turboexpanders, and experimental electric aircraft engines [46].

4. Hybrid Bearing Configurations and Design Approaches

- I

- Nested or Concentric Bearings: An early approach is to physically collocate a gas bearing and a magnetic bearing around the same rotor journal. The nested layout saves space (shorter rotor length than two separate bearings) and was used in several prototypes. However, it requires a fairly complex construction (embedding foil pads within a magnetic circuit) and precise alignment [52,59].

- II

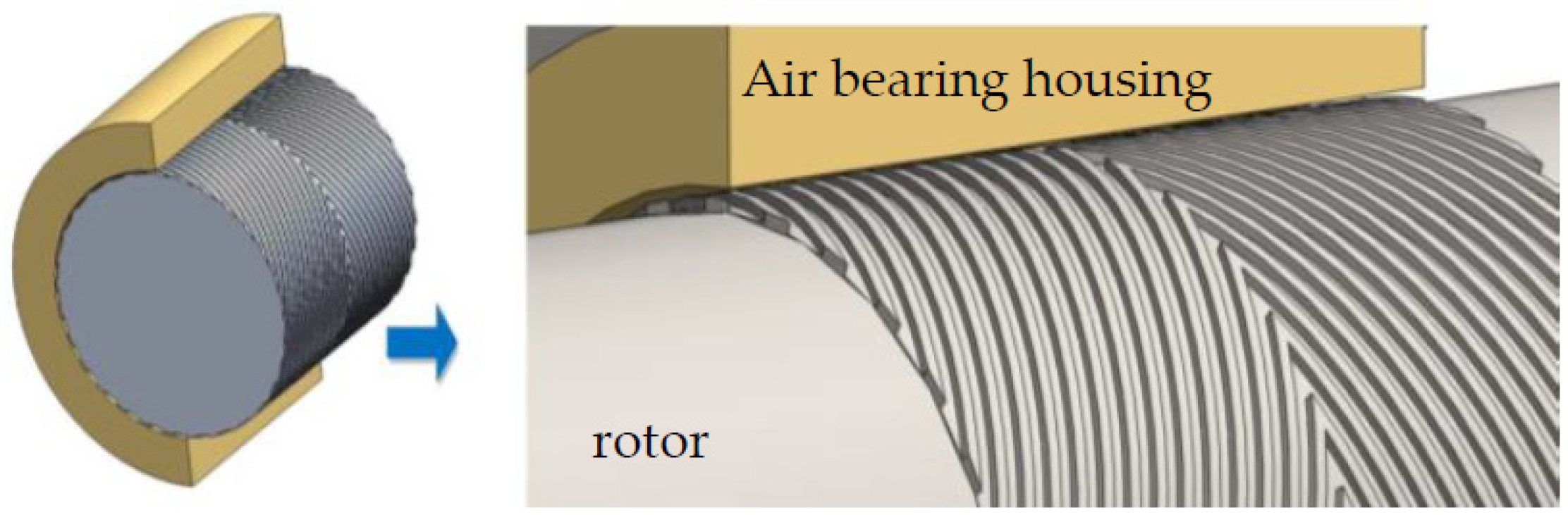

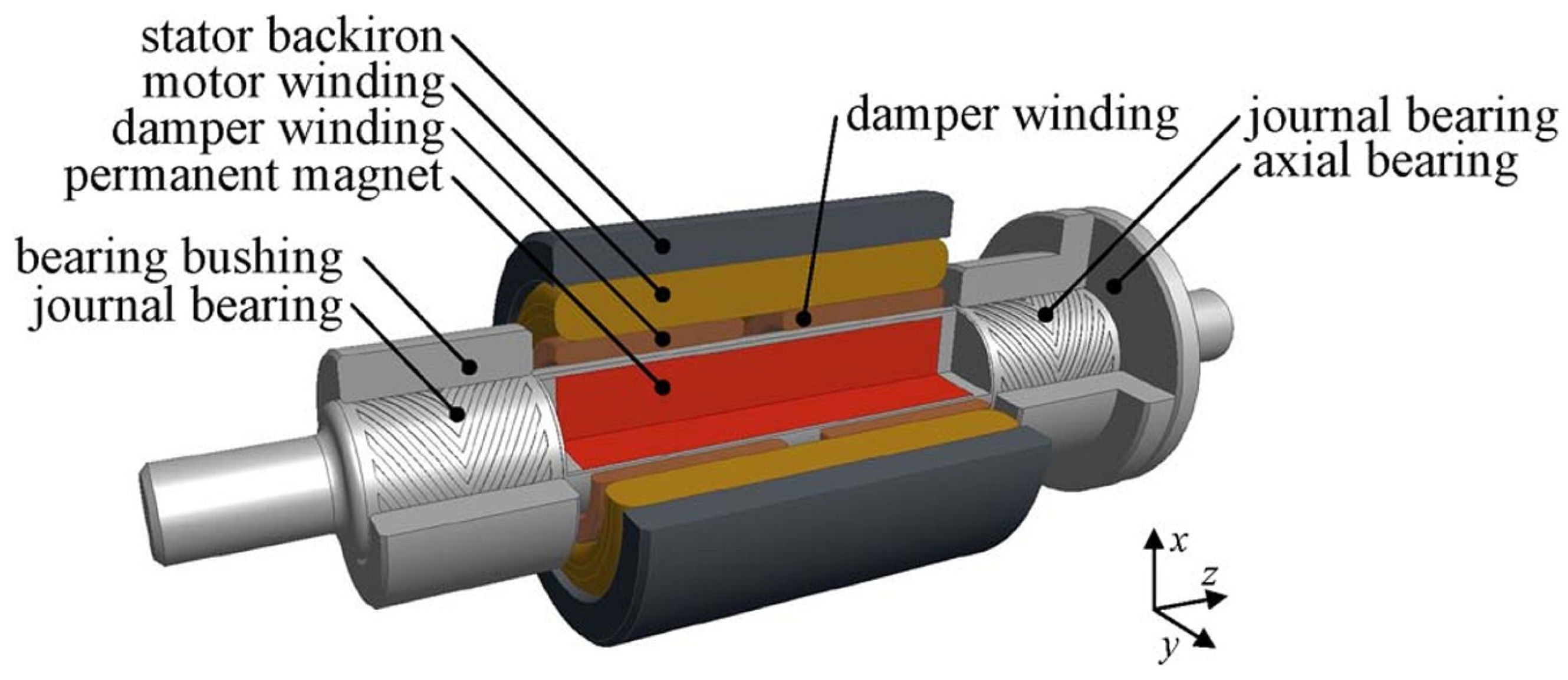

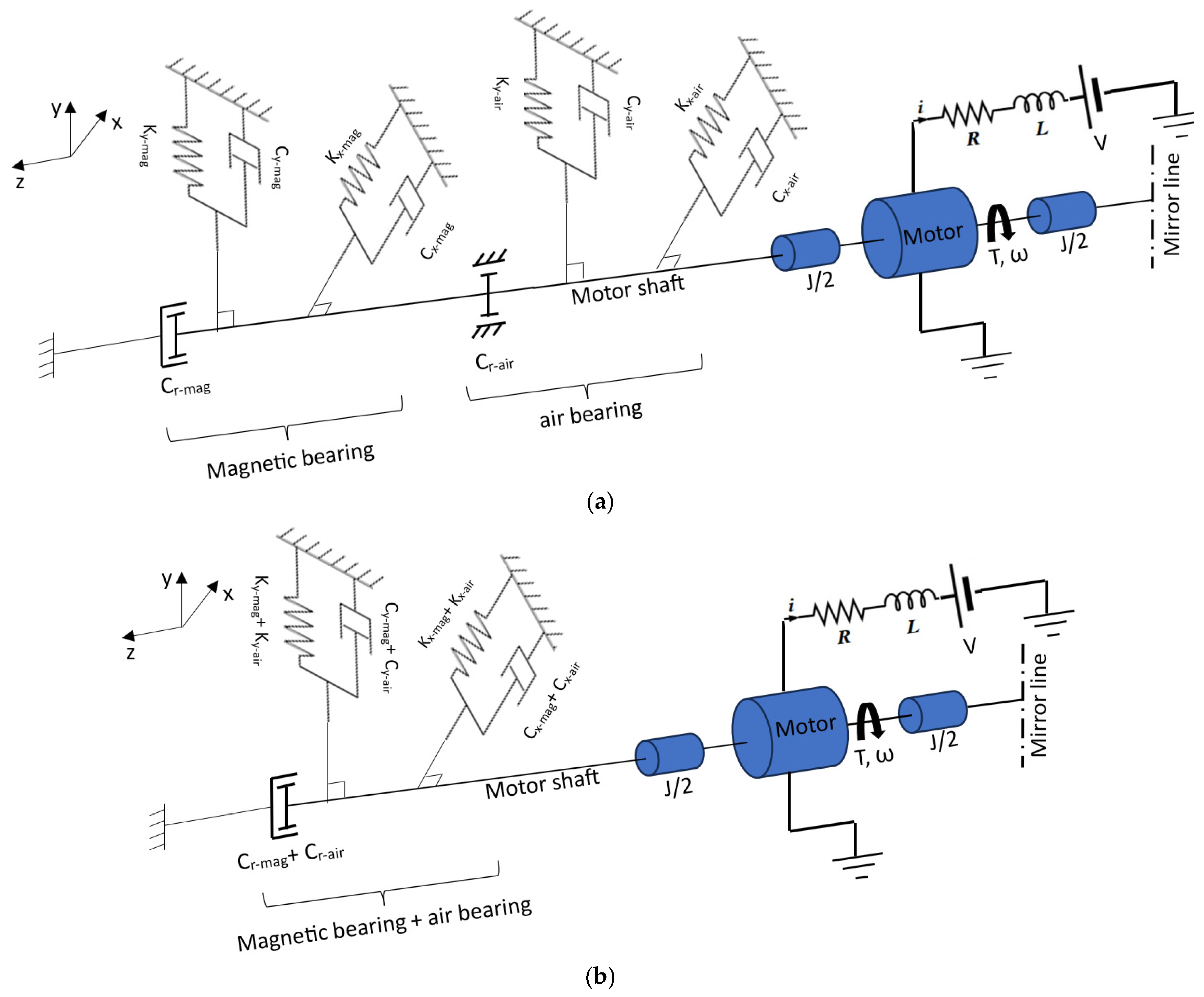

- Series (Axial) Arrangement: Another approach simply places a magnetic bearing next to a gas bearing along the shaft. This is easier to implement (each bearing retains its own structure), and the control strategy can modulate how load is shared (e.g., through a coupling or compliance). The downside is a longer rotor and potential dynamic coupling issues [1,60]. Figure 6 reveals these two types. The air bearing housing is made of a porous, non-ferromagnetic material such as aluminum or ceramic. In contrast, the magnetic bearing stator is made of ferromagnetic iron and has a laminated structure to prevent the generation of eddy currents within it.

- III

- Integrated Single-Structure HGMB: The latest designs strive to truly integrate both functions into one bearing element [48]. In a single-structured HGMB, the goal is that the same physical gap and surfaces serve as both the magnetic bearing air gap and the gas film clearance. This eliminates separate foil structures or external gas feeds where the gas film is a simple clearance between the rotor and the stator sleeve. The main difficulty here is clearance compatibility: Magnetic bearings typically need a larger gap on the order of 0.5–1 mm for large AMBs to avoid saturating and to allow enough control range. Whereas gas bearings work best with very small clearances on the order of 50 µm to generate high pressure [46]. This design has been specifically proposed for cryogenic turboexpanders used in hydrogen liquefaction, which require frequent start-stop cycles and ultra-high speeds of 70,000 rpm. In such electrical machines, traditional oil bearings cannot be used due to contamination/viscosity issues [48], and pure magnetic bearings would generate too much heat and consume too much power at high speed in a vacuum-like environment. A single-structured HGMB can provide the needed performance while minimizing frictional losses and complexity [50]. Figure 7 shows an integrated Single-Structure HGMB.

- IV

- Zero-Bias Magnetic Hybrid: A variant in design philosophy is using zero-bias AMB in the hybrid to further reduce power loss and heating. Typically, AMBs use bias currents [3]; however, a “zero-bias HGMB” means the magnetic bearing part has no DC and only actively provides corrective forces as needed. Without bias, the magnetic stiffness is lower [46]. Therefore, the gas bearing must carry more of the static load. Liu et al. in 2025 [62] examined a single-structured HGMB under zero-bias operation. They simulated that while a zero-bias AMB alone had reduced load capacity and dynamic stiffness, combining it with a rigid gas bearing allowed the hybrid to function well even with zero bias. The benefit was a significant reduction in power consumption and heat generation compared to a traditional biased HGMB or pure AMB. The zero-bias HGMB performed ideally for light loads at ultra-high speeds or in cryogenic environments where any heat is problematic. This suggests that future HGMBs do not need bias current, making the system more efficient for aerospace applications, where every Watt of waste heat counts heavily.

Design Trade-Offs and Integration Challenges

5. Performance Characteristics and Comparative Analysis

5.1. Load Capacity and Speed Range

5.2. Stiffness, Damping, and Stability

5.3. Friction Losses and Efficiency

5.4. Complexity, Reliability, and Design Maturity

5.5. Control Strategies for Hybrid Gas–Magnetic Bearings

6. Future Research Directions and Conclusion

- i

- Optimization of Design Parameters: As evidenced by recent studies [50,68] on clearance and geometry, finding the optimal balance in design (clearance, bearing size, bias current, etc.) is complex. Future work will involve multi-physics optimization—concurrently tuning magnetic circuit designs, fluid film geometries, and control laws. The goal is to maximize load and stability while minimizing losses and ensuring reliability. Tools that can co-simulate rotor dynamics with both fluid film and magnetic control will be invaluable. In particular, defining standards or guidelines for HGMB design (analogous to well-known charts and formulas for traditional bearings) will help engineers not intimately familiar with the technology to adopt it confidently.

- ii

- Advanced Control and Sensing: The active magnetic component provides an opportunity to implement sophisticated control algorithms for the rotor-bearing system [48]. Research can explore adaptive control that adjusts based on rotor speed (e.g., gradually handing off to the gas bearing) and fault-tolerant control [3] that can detect a failing sub-component and compensate via the other. Additionally, magnetics allows for built-in sensing (the AMB actuators themselves can sense rotor position through inductance changes). Active damping algorithms [48] will continue to be refined to extend the stable range of gas films.

- iii

- Integration with Motors: A future direction is integrating HGMB with the propulsion electric motor itself. For instance, an axial gap motor could conceivably incorporate a gas film in the gap and use the motor windings for cantering at low speeds. Liu et al. [50] study basically went in this direction by choosing an axial generator to complement the bearing design. Such integration can yield ultra-compact and efficient designs, but would require joint optimization of electromagnetic torque and suspension forces.

- iv

- Robustness in Real Conditions: Aerospace environments include vibrations, shocks (e.g., an aircraft landing or a rocket stage separation), and wide temperature swings. HGMB prototypes should be tested under such conditions. Particularly, the behavior under sudden external loads or loss-of-power scenarios [49] needs further study to ensure the hybrid system transitions smoothly to backup mode. The role of touchdown or backup bearings in an HGMB-equipped system should also be refined. Perhaps they can be smaller or simpler given the hybrid’s inherent redundancy, but they may still be needed for certification. Work on emergency modes (e.g., magnetic bearing catching the rotor after a sudden speed drop that collapses the gas film) will build confidence in the technology.

- v

- Application-Specific Adaptation: Different applications might require tailoring the hybrid approach. For example, a rocket turbopump might use a permanent magnet biased AMB combined with hydrostatic helium bearings—a somewhat different variant than an aircraft cabin air compressor that might use foil bearings with an actively controlled magnetic damper. Research into hybrid configurations for specific aerospace systems (like turbo-fan engine shafts, cryocooler turbines, etc.) will likely continue. Each has unique requirements (life, noise, power, environment) that may push the design one way or another.

7. Conclusions

8. Methodology of Literature Search and Selection

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Heshmat, H.; Chen, H.M.; Walton, J.F., II. On the Performance of Hybrid Foil-Magnetic Bearings. J. Eng. Gas Turbines Power 2000, 122, 73–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swanson, E.E.; Heshmat, H. Oil-Free Foil Bearings as a Reliable, High Performance Backup Bearing for Active Magnetic Bearings. In Proceedings of the ASME Turbo Expo 2002, Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 3–6 June 2002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swanson, E.E.; Heshmat, H.; Walton, J. Performance of a Foil–Magnetic Hybrid Bearing. J. Eng. Gas Turbines Power 2002, 124, 375–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Zhang, C.; Zhang, C.; Li, L. Review of High-Power-Density and Fault-Tolerant Design of Propulsion Motors for Electric Aircraft. Energies 2023, 16, 7015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adu-Gyamfi, B.A.; Good, C. Electric Aviation: A Review of Concepts and Enabling Technologies. Transp. Eng. 2022, 9, 100134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brelje, B.J.; Martins, J.R.R.A. Electric, Hybrid, and Turboelectric Fixed-Wing Aircraft: A Review of Concepts, Models, and Design Approaches. Prog. Aerosp. Sci. 2019, 104, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asef, P.; Perpiñà, R.B.; Lapthorn, A.C. Optimal Pole Number for Magnetic Noise Reduction in Variable-Speed Permanent Magnet Synchronous Machines with Fractional-Slot Concentrated Windings. IEEE Trans. Transp. Electrif. 2019, 5, 126–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asef, P.; Perpiñà, R.B.; Moazami, S.; Lapthorn, A.C. Rotor Shape Multi-Level Design Optimization for Double-Stator Permanent Magnet Synchronous Motors. IEEE Trans. Energy Convers. 2019, 34, 1223–1231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asef, P.; Bargallo, R.; Lapthorn, A.; Tavernini, D.; Shao, L.; Sorniotti, A. Assessment of the Energy Consumption and Drivability Performance of an IPMSM-Driven Electric Vehicle Using Different Buried Magnet Arrangements. Energies 2021, 14, 1418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asef, P.; Lapthorn, A. Overview of Sensitivity Analysis Methods Capabilities for Traction AC Machines in Electrified Vehicles. IEEE Access 2021, 9, 23454–23471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vatani, M.; Stewart, D.R.; Asef, P.; Ionel, D.M. Optimal Design of Coreless Axial Flux PM Machines Using a Hybrid Machine Learning and Differential Evolution Method. In Proceedings of the 2025 IEEE International Electric Machines & Drives Conference (IEMDC), Houston, TX, USA, 18–21 May 2025; pp. 1262–1267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stewart, D.R.; Vatani, M.; Alden, R.E.; Lewis, D.D.; Asef, P.; Ionel, D.M. Combined Machine Learning and Differential Evolution for Optimal Design of Electric Aircraft Propulsion Motors. In Proceedings of the 2024 13th International Conference on Renewable Energy Research and Applications (ICRERA), Nagasaki, Japan, 9–13 November 2024; pp. 1823–1828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saeidabadi, S.; Parsa, L.; Corzine, K.A.; Kovacs, C.; Haugan, T. Double-Rotor Flux Switching Machine with HTS Field Coils and Superconducting Shields for Aircraft Propulsion. IEEE Access 2024, 12, 132508–132520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spaven, F.; Liu, Y.; Bucknall, R.; Coombs, T.; Baghdadi, M. Thermal Design of Superconducting Cryogenic Rotor: Solutions to Conduction Cooling Challenges. Case Stud. Therm. Eng. 2021, 28, 101423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baghdadi, M.; Ruiz, H.S.; Fagnard, J.F.; Zhang, M.; Wang, W.; Coombs, T.A. Investigation of Demagnetization in HTS Stacked Tapes Implemented in Electric Machines as a Result of Crossed Magnetic Field. IEEE Trans. Appl. Supercond. 2015, 25, 6602404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grilli, F. Superconducting Motors for Aircraft Propulsion: The Advanced Superconducting Motor Experimental Demonstrator Project. J. Phys. Conf. Ser. 2020, 1590, 012051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caughley, A.; Lumsden, G.; Weijers, H.; Jeong, S.; Badcock, R.A. Cooling of Superconducting Motors on Aircraft. Aerospace 2024, 11, 317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haran, K.S.; Kalsi, S.; Arndt, T.; Karmaker, H.; Badcock, R.; Buckley, B.; Haugan, T.; Izumi, M.; Loder, D.; Bray, J.W.; et al. High-Power-Density Superconducting Rotating Machines—Development Status and Technology Roadmap. Supercond. Sci. Technol. 2017, 30, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hao, Z.; Ma, Y.; Wang, P.; Luo, G.; Chen, Y. A Review of Axial-Flux Permanent-Magnet Motors: Topological Structures, Design, Optimization and Control Techniques. Machines 2022, 10, 1178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kelch, F.; Yang, Y.; Bilgin, B.; Emadi, A. Investigation and Design of an Axial Flux Permanent Magnet Machine for a Commercial Midsize Aircraft Electric Taxiing System. IET Electr. Syst. Transp. 2018, 8, 52–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, S. Design Study of an Aerospace Motor for More Electric Aircraft. IET Electr. Power Appl. 2020, 14, 2881–2890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weng, F.; Zhang, M.; Lan, T.; Wang, Y.; Yuan, W. Fully Superconducting Machine for Electric Aircraft Propulsion: Study of AC Loss for HTS Stator. Supercond. Sci. Technol. 2020, 33, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Branagan, M.; Griffin, D.; Goyne, C.; Untaroiu, A. Compliant Gas Foil Bearings and Analysis Tools. J. Eng. Gas Turbines Power 2016, 138, 054001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, C.; Li, C.; Du, J. A Review on the Dynamic Performance Studies of Gas Foil Bearings. Lubricants 2024, 12, 262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- San Andrés, L.; Kim, T.H. Analysis of Gas Foil Bearings Integrating FE Top Foil Models. Tribol. Int. 2009, 42, 111–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- San Andrés, L.; Kim, T.H. Thermohydrodynamic Analysis of Bump-Type Gas Foil Bearings: A Model Anchored to Test Data. J. Eng. Gas Turbines Power 2010, 132, 042504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, J.; Kim, D.; Sim, K. Development and Performance Measurements of Gas Foil Polymer Bearings with a Dual-Rotor Test Rig Driven by Permanent Magnet Electric Motor. Appl. Sci. 2022, 12, 1505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Żywica, G.; Bagiński, P.; Roemer, J.; Zdziebko, P.; Martowicz, A.; Kaczmarczyk, T.Z. Experimental Characterization of a Foil Journal Bearing Structure with an Anti-Friction Polymer Coating. Coatings 2022, 12, 1252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, T.; Xiong, W.; Peng, X.; Feng, J.; Guo, Y. Experimental Investigation on the Start-Stop Performance of Gas Foil Bearings-Rotor System in the Centrifugal Air Compressor for Hydrogen Fuel Cell Vehicles. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2023, 48, 27183–27196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, B.; Hou, A.; Deng, R.; Wang, R.; Wu, Z.; Ni, Q.; Li, Z. Numerical Investigation of Bump Foil Configurations Effect on Gas Foil Thrust Bearing Performance Based on a Thermo-Elastic-Hydrodynamic Model. Lubricants 2023, 11, 417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, T.H.; San Andrés, L. Heavily Loaded Gas Foil Bearings: A Model Anchored to Test Data. J. Eng. Gas Turbines Power 2008, 130, 012504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ke, C.; Qiu, S.; Li, K.; Xiong, L.; Peng, N.; Zhang, X.; Dong, B.; Liu, L. Numerical Computation and Experimental Research for Dynamic Properties of Ultra-High-Speed Rotor System Supported by Helium Hydrostatic Gas Bearings. Lubricants 2024, 12, 302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gandzha, S.; Nikolay, N.; Chuyduk, I.; Salovat, S. Design of a Combined Magnetic and Gas Dynamic Bearing for High-Speed Micro-Gas Turbine Power Plants with an Axial Gap Brushless Generator. Processes 2022, 10, 1067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maslen, E.H.; Sortore, C.K.; Gillies, G.T.; Williams, R.D.; Fedigan, S.J.; Aimone, R.J. Fault-Tolerant Magnetic Bearings. J. Eng. Gas Turbines Power 1999, 121, 504–508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M.-H.; Palazzolo, A.B.; Kenny, A.; Provenza, A.J.; Beach, R.F.; Kascak, A.F. Fault-Tolerant Homopolar Magnetic Bearings. IEEE Trans. Magn. 2004, 40, 3308–3318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sahinkaya, A.; Sawicki, J. Robust Control of Active Magnetic Bearing Systems with an Add-On Controller to Cancel Gyroscopic Effects: Is It Worth It? J. Vib. Control. 2021, 27, 359–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tamisier, V.; Font, S.; Lacou, M.; Carrere, F.; Dumur, D. Attenuation of Vibrations Due to Unbalance of an Active-Magnetic-Bearing Milling Electro-Spindle. CIRP Annals 2001, 50, 255–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maslen, E.H.; Allaire, P.E.; Noh, M.D.; Sortore, C.K. Magnetic Bearing Design for Reduced Power Consumption. J. Tribol. 1996, 118, 839–846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Na, U.J. Fault-Tolerant Control of Magnetic Bearings with Force Invariance. J. Mech. Sci. Technol. 2005, 19, 731–742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agarwal, P.K.; Chand, S. Fault-Tolerant Control of Three-Pole Active Magnetic Bearing. Expert Syst. Appl. 2009, 36, 12592–12604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y.; Wang, X.; Liu, M.; Li, N.; Yu, T. Fuzzy Variable Gains Robust Control of Active Magnetic Bearings Rigid Rotor System. IET Intell. Transp. Syst. 2024, 18, 90–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Javed, A.; Mizuno, T.; Takasaki, M.; Ishino, Y.; Hara, M.; Yamaguchi, D. Lateral Vibration Suppression by Varying Stiffness Control in a Vertically Active Magnetic Suspension System. Actuators 2018, 7, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Na, U.J. Fault Tolerance of Homopolar Magnetic Bearings. J. Sound Vib. 2004, 272, 495–511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, Z.; Wei, Z.; Sun, Y. Nonlinear Adaptive Control for Hybrid Foil-Magnetic Bearing. In Proceedings of the 2017 IEEE International Conference on Mechatronics and Automation (ICMA), Takamatsu, Japan, 6–9 August 2017; pp. 81–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Falkowski, A.; Mazurek, P.; Szocl, T.; Henzel, M. Radial Magnetic Bearings for Rotor–Shaft Support in Electric Jet Engine. Energies 2022, 15, 3339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Q.; Ahn, H. Hybrid Gas-Magnetic Bearings: An Overview. J. Appl. Electromagn. 2021, 53, 123–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barati, H.; Karafi, M. A Hybrid Contactless Air-Magnetic Bearing System for Operating at 15,000 rpm. Iran. J. Mech. Eng. Trans. ISME 2024, 25, 40–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Looser, A.; Kolar, J.W. An Active Magnetic Damper Concept for Stabilization of Gas Bearings in High-Speed Permanent-Magnet Machines. IEEE Trans. Ind. Appl. 2014, 50, 2363–2372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heshmat, H.; Xu, D.S. Experimental Investigation of 150 mm Diameter Large Hybrid Foil/Magnetic Bearing. In Proceedings of the 2003 International Gas Turbine Congress, Tokyo, Japan, 2–7 November 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Q.; Ge, R.; Wang, L.; Ren, T.; Feng, M. Single-Structured Zero-Bias Hybrid Gas-Magnetic Bearing and Its Rotor Dynamic Performance. International J. Appl. Electromagn. Mech. 2024, 74, 79–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ha, Y.; Kim, J.; Jeong, K.; Lee, Y. Rigid Mode Vibration Control for 250 HP Air Compressor System with Integrated Hybrid Air-Foil Magnetic Thrust Bearing (i-HFMTB). ASME J. Eng. Gas Turbines Power 2024, 146, 041002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basumatary, K.K.; Kumar, G.; Kalita, K.; Kakoty, S.K. Stability Analysis of Rigid Rotors Supported by Gas Foil Bearings Coupled with Electromagnetic Actuators. Proc. Inst. Mech. Eng. Part C J. Mech. Eng. Sci. 2019, 234, 427–443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, C.; Knospe, C. Optimal Control of a Magnetic Bearing without Bias Flux. In Proceedings of the 1997 American Control Conference, Albuquerque, NM, USA, 6 June 1997; pp. 1534–1538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rong, H.; Zhou, K. Nonlinear Zero-Bias Current Control for Active Magnetic Bearing in Power Magnetically Levitated Spindle Based on Adaptive Backstepping Sliding Mode Approach. Proc. Inst. Mech. Eng. Part C J. Mech. Eng. Sci. 2016, 231, 3753–3765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.; Weng, C. Robust Control of a Voltage-Controlled Three-Pole Active Magnetic Bearing System. IEEE/ASME Trans. Mechatron. 2010, 15, 381–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hung, J.Y. Magnetic Bearing Control Using Fuzzy Logic. IEEE Trans. Ind. Appl. 1995, 31, 1492–1497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.Y.; Song, M.H. Energy-Saving Dynamic Bias Current Control of Active Magnetic Bearing Positioning System Using Adaptive Differential Evolution. IEEE Trans. Syst. Man Cybern. Syst. 2019, 49, 942–953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heshmat, H.; Walton, J.F., II. Hybrid Foil-Magnetic Bearing with Improved Load Sharing. U.S. Patent No. US6965181B1, 15 November 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, B.; Geng, H.; Sun, Y.; Yu, L. Dynamic Characteristics of Hybrid Foil-Magnetic Bearings (HFMBs) Concerning Eccentricity Effect. Int. J. Appl. Electromagn. 2016, 52, 271–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jang, H.; Kim, J.; Han, D.; Jang, D.; Ahn, H. Improvement of High-Speed Stability of an Aerostatic Bearing-Rotor System Using an Active Magnetic Bearing. Int. J. Precis. Eng. Manuf. 2014, 15, 2565–2572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heshmat, H. Hybrid Foil-Magnetic Bearing. U.S. Patent US6353273B1, 15 September 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Q.; Wu, M.; Ge, R.; He, W.; Cheng, Z. Effect of Radial Clearance on Static and Dynamic Performances of Single-Structured Hybrid Gas-Magnetic Bearing Rotor System. ASME J. Tribol. 2025, 147, 104601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Yin, Q.; Guan, H.; Cao, Y.; Feng, K. Theoretical Investigation of Hybrid Foil-Magnetic Bearings on Operation Mode and Load Sharing Strategy. Proc. Inst. Mech. Eng. Part J J. Eng. Tribol. 2022, 236, 2491–2506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- San Andrés, L.; Rodríguez, B. Experiments with a Rotor-Hybrid Gas Bearing System Undergoing Maneuver Loads from Its Base Support. ASME J. Eng. Gas Turbines Power 2020, 142, 111004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Shi, Z.; Wang, M.Q. Study of the failure criterion for non-lubricated hybrid bearings under high-speed and heavy-load conditions. Tribol. Int. 2026, 214, 111174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, T.; Zhang, W. Review on Key Development of Magnetic Bearings. Machines 2025, 13, 113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, Y.; Zhang, G.; Hua, W. Review on Research and Development of Magnetic Bearings. Energies 2025, 18, 3222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Q.; Wang, L.; Feng, M. Clearance Compatibility and Design Principle of the Single-Structured Hybrid Gas-Magnetic Bearing. Ind. Lubr. Tribol. 2023, 75, 1219–1228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Aerospace System | Typical Speed Range | Operating Temperature | Radial Load Capacity Required | Environment/ Working Fluid | Technical Motivation for HGMB |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cryogenic H2 Turbo-Expander (Hydrogen liquefaction, ESA/industry) [50] | 40,000–70,000 rpm | 20–90 K | 200–800 N | Hydrogen, cryogenic | Minimize magnetic coil heating; oil-free; maintain stiffness at cryogenic viscosity |

| Rocket Turbopump (LOX/LH2 environment) [1] | 20,000–35,000 rpm | 300–600 °C transient | 3–6 kN | Liquid oxygen or hydrogen | No oil allowed; tolerate high shock load; fail-safe capability during magnetic shutdown |

| Electric Aircraft High-Speed Propulsion Motor [4] NASA’s Turboelectric Distributed Propulsion, Airbus ZEROe | 20,000–40,000 rpm | 100–200 °C | 500–1500 N | Air; high-altitude low-density | Reduce losses, suppress vibration; lightweight oil-free support for distributed propulsion |

| Aspect | Gas Bearings (GFBs/HGBs) | Magnetic Bearings (AMBs) | Hybrid Gas–Magnetic Bearings (HGMBs) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Load Capacity | Hydrodynamic: 0.5–2 kN (depends on speed) [1,49] Hydrostatic: up to 5–10 kN [52] | Typical: 0.5–2 kN [1] Large AMBs: 2–6 kN (limited by saturation) [4,46] | 3–5× AMB capacity [3] 5.3 kN demonstrated in turbine tests [3] |

| Stiffness (radial) | 106–108 N/m (small clearances 10–80 µm) [33] | 105–106 N/m (open-loop) 106–107 N/m (closed-loop) [58] | 106–108 N/m (combined effect) [52] |

| Damping | Very low: 10–200 N·s/m [51] | Closed-loop equivalent damping tunable: 200–2000 N·s/m [58] | High damping at low speeds (AMB) + moderate damping at high speeds (gas film) [60] |

| Speed Limit | Foil bearings: 20,000–200,000 rpm [26] Hydrostatic: 10,000–80,000 rpm [33] | Most AMBs: 10,000–60,000 rpm [46] | Demonstrated: 30,000–70,000 rpm [33] |

| Power Loss | Air shear loss <1–3% of motor losses [46] | Joule + eddy losses: 20–200 W per bearing [46] | Lowest combined: 20–50 W in hybrid mode, AMB losses low at high speed, gas losses low at low speed [3] |

| Operating Temperature | −200 °C to >650 °C [24] | −200 °C to 200 °C (coil resistivity increases with temp) [46] | Cryogenic to high-temp ranges depending on design [50] |

| Clearance Range | 10–80 µm [33] | 300–1000 µm [4] | 50–300 µm (compromise for hybrid integration) [46,52] |

| Startup Behavior | Requires speed or external pressure [51] | Excellent: supports rotor at 0 rpm [3] | AMB handles zero speed; gas takes over at high speeds [33] |

| Failure Behavior | Film collapses → rub [51] | Power loss → rotor drops to backup bearing [45] | Redundancy: each system backs up the other [3,47] |

| Volume, Mass | Small [23] | Large (due to coils + iron) [46] | 20–35% volume reduction 10–25% mass reduction [50] |

| Rotor Speed Range | Dominant Mechanism | Lifetime Trend |

|---|---|---|

| 0–5 krpm | Magnetic heating (AMB-dominated) | Essentially unlimited (AMB-limited) |

| 5–20 krpm | Mixed magnetic–gas loading | Lifetime stable; minor thermal cycling |

| >20 krpm | Gas film dominated | >10,000 h demonstrated (foil-based hybrids) |

| >40 krpm | High-speed structural stress | Depends on foil fatigue and boundary lubrication |

| Speed | AMB Power Loss | Gas Bearing Loss | Total Hybrid Loss |

|---|---|---|---|

| 0 rpm | 40–120 W | 0 W | 40–120 W |

| 10,000 rpm | 20–80 W | 1–3 W | 25–85 W |

| 40,000 rpm | 5–20 W | 3–7 W | 10–25 W |

| 60,000 rpm | 5–10 W | 5–12 W | 10–22 W |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Published by MDPI on behalf of the World Electric Vehicle Association. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Karafi, M.R.; Asef, P. Review of Emerging Hybrid Gas–Magnetic Bearings for Aerospace Electrical Machines. World Electr. Veh. J. 2025, 16, 662. https://doi.org/10.3390/wevj16120662

Karafi MR, Asef P. Review of Emerging Hybrid Gas–Magnetic Bearings for Aerospace Electrical Machines. World Electric Vehicle Journal. 2025; 16(12):662. https://doi.org/10.3390/wevj16120662

Chicago/Turabian StyleKarafi, Mohammad Reza, and Pedram Asef. 2025. "Review of Emerging Hybrid Gas–Magnetic Bearings for Aerospace Electrical Machines" World Electric Vehicle Journal 16, no. 12: 662. https://doi.org/10.3390/wevj16120662

APA StyleKarafi, M. R., & Asef, P. (2025). Review of Emerging Hybrid Gas–Magnetic Bearings for Aerospace Electrical Machines. World Electric Vehicle Journal, 16(12), 662. https://doi.org/10.3390/wevj16120662