Liability for Autonomous Vehicle Torts: Who Should Be Held Responsible?

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Autonomous Vehicle Liability in China: Legal Framework and Challenges

2.1. The Legal Framework for Autonomous Driving Liability

2.2. The Dilemma of Liability Attribution in Autonomous Driving

2.2.1. Difficulties in Liability Attribution

2.2.2. Insurance System Deficits in Autonomous Driving

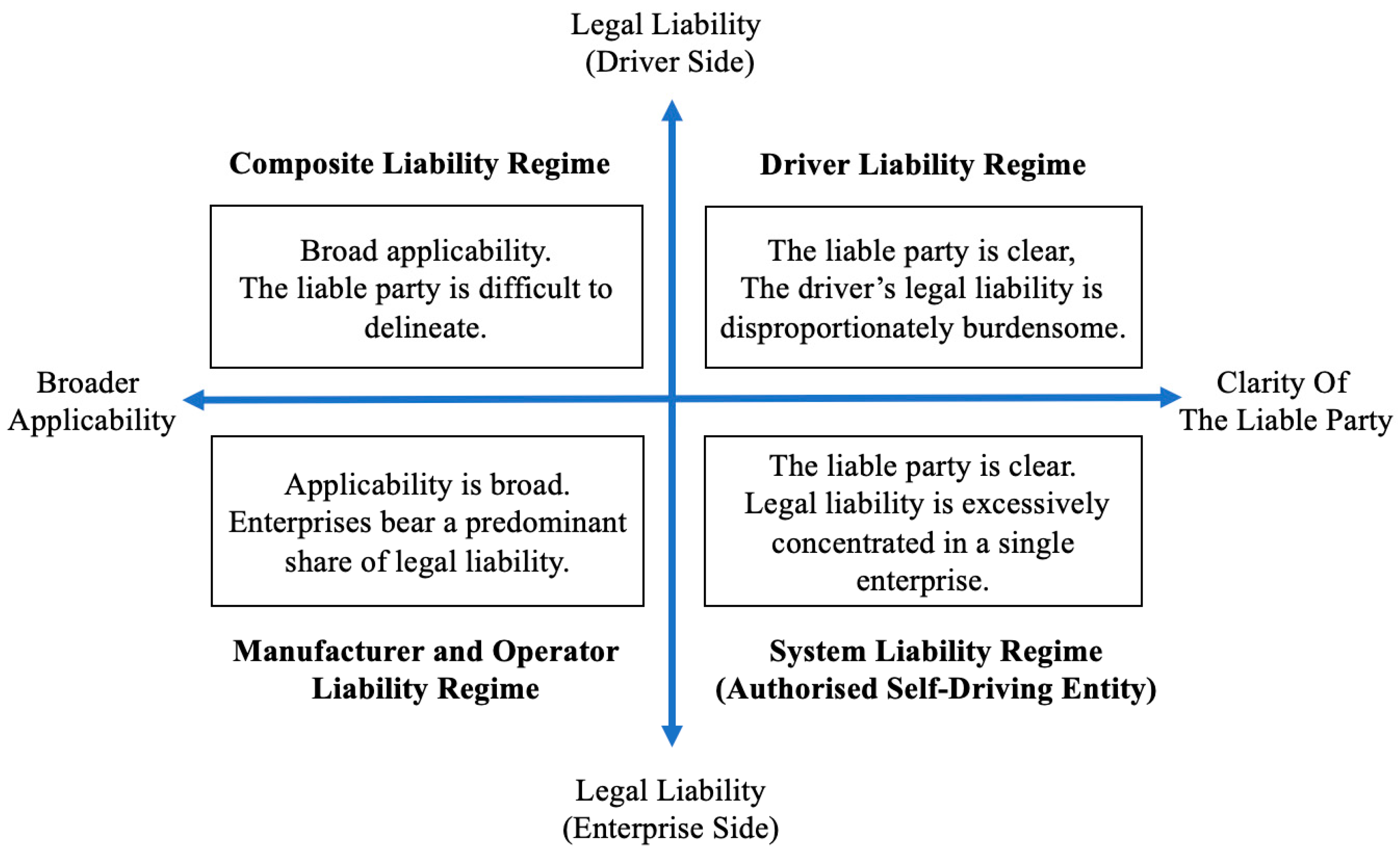

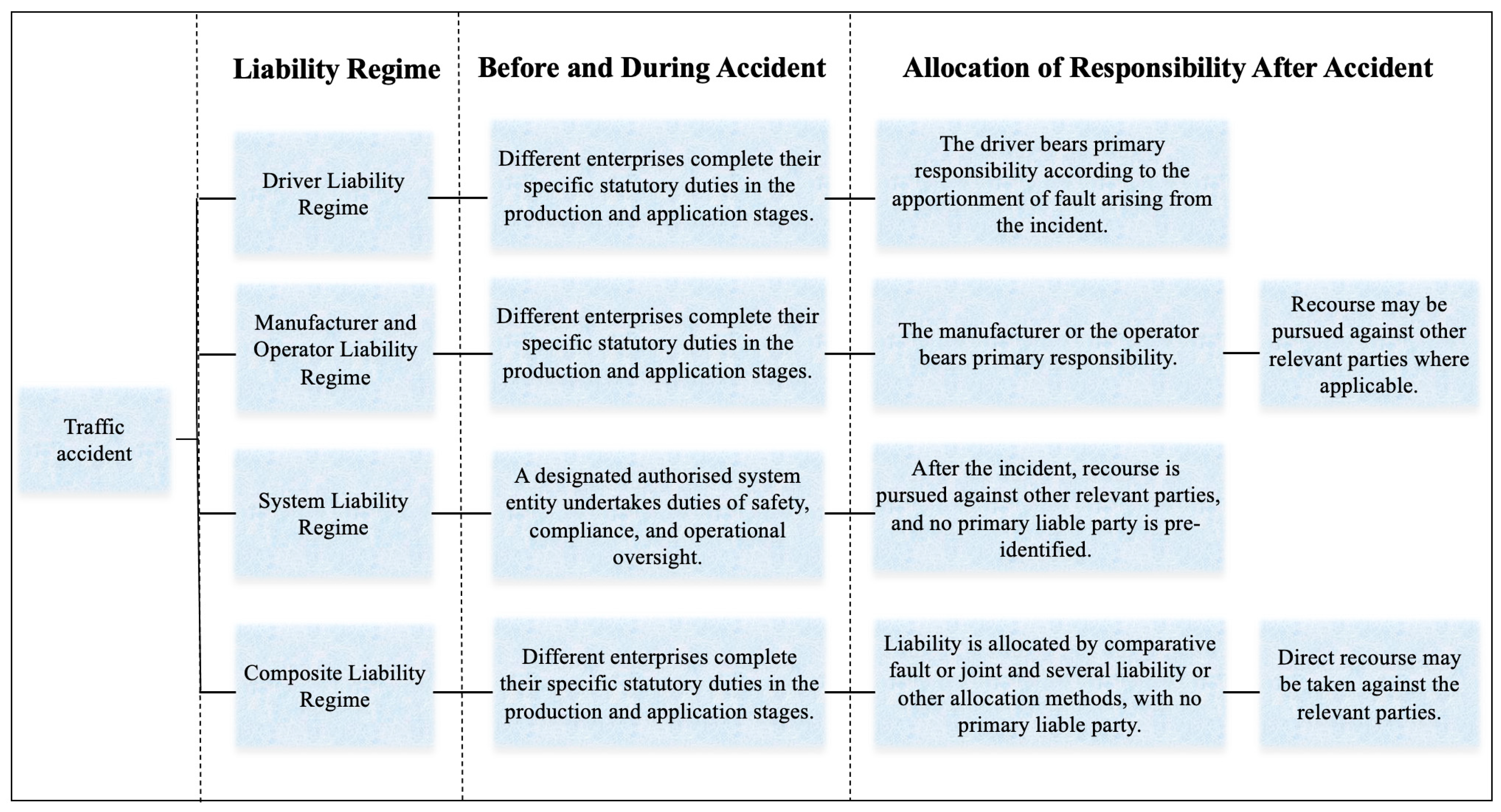

3. Analysis of Liability Regimes for Autonomous Driving

3.1. Driver Liability Regime

3.2. Manufacturer and Operator Liability Regime

3.3. System Liability Regime

3.4. Composite Liability Regime

4. Exploring Liability Regimes for Autonomous Driving in China

4.1. The Development of China’s Autonomous Driving Industry

4.2. Proposed Liability Regime for Automated Driving in China

4.2.1. Liability Regime Across Levels of Driving Automation

- 1.

- L0–L2: Driver Liability Regime

- 2.

- L3: Driver, Manufacturer or Operator Liability Regime

- 3.

- L4–L5: Manufacturer, Operator or System Liability Regime

4.2.2. Complementary Rules for Liability Attribution

4.3. Global Applicability and Potential Uptake of the Chinese Approach

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Liu, S. New Reflections on the Criminal Liability of Traffic Accidents by Autonomous Vehicle. J. Railw. Police Coll. 2025, 35, 48–54. [Google Scholar]

- Davola, A. A Model for Tort Liability in a World of Driverless Cars: Adapting the Civil Liability System to the Shifting Paradigm of Driving. Ida. Law Rev. 2018, 54, 592–614. [Google Scholar]

- Calvert, S.C.; Zgonnikov, A. A Lack of Meaningful Human Control for Automated Vehicles: Pressing Issues for Deployment and Regulation. Front. Future Transp. 2025, 6, 1534157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, Y. Research on the Identification of the Subject of Infringement Liability of Autonomous Driving Vehicles. Open J. Leg. Sci. 2024, 12, 2492–2500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, X.; Guo, C. A Comparative Legal Study on the Attribution of Liability for Autonomous Driving Accidents in China and Germany. Ctry. Area Adv. Technol. 2025, 1, 28–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Widen, W.H.; Wolf, M.C. Law as a Design Consideration for Automated Vehicles Suitable to Transport Intoxicated Persons. In Proceedings of the 2025 Design, Automation & Test in Europe Conference (DATE), Lyon, France, 31 March–2 April 2025; pp. 1–7. [Google Scholar]

- Steege, H.; Caggiano, I.A.; Gaeta, M.C.; Bodungen, B. Autonomous Vehicles and Civil Liability in a Global Perspective: Liability Law Study Across the World in Relation to SAE J3016 Standard for Driving Automation, 1st ed.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2024; pp. 19–28, 409–428, 430–432. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, Z.; Cai, Q.; Wei, H. Distribution of the Burden of Proof in Autonomous Driving Tort Cases: Implications of the German Legislation for China. World Electr. Veh. J. 2024, 15, 305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L. New Challenges to Civil Law in the AI Era. Orient. Law 2018, 3, 4–9. [Google Scholar]

- Zheng, F. Legal Risks of Driver Assistance and Countermeasures. Shanghai Rule of Law Daily. 2025. Available online: https://zjkxyjy.cupl.edu.cn/info/2538/8359.htm (accessed on 26 November 2025).

- Ye, F.; Fan, S. Research on the Tort Liability Subject in Autonomous Vehicle Traffic Accidents. J. Chongqing Univ. Sci. Technology 2025, 2, 45–57. [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Chamber Institute for Legal Reform. Torts of the Future III: Autonomous Vehicles and Emerging Liability Challenges; U.S. Chamber Institute for Legal Reform: Washington, DC, USA, 2018; Available online: https://instituteforlegalreform.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/10/Torts_of_the_Future_Repackage_Update051418_Web.pdf (accessed on 26 November 2025).

- De Bruyne, J.; Werbrouck, J. Merging Self-Driving Cars with the Law. Comput. Law Secur. Rev. 2018, 34, 1150–1153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, X. The Liability Structure of Automated Driving—Also on the Three-Layer Insurance Structure of Automated Driving Vehicles. J. Shanghai Univ. (Soc. Sci.) 2019, 36, 90–103. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Y.; Xu, C. Research on Tort Liability of Driverless Vehicles in Traffic Accidents. J. Heilongjiang Univ. Technol. 2022, 22, 128–133. [Google Scholar]

- Gao, W.; Ning, Z. Regulations on the Risk of Harm Caused by Artificial Intelligence Products and Its Tort Liability. Henan Soc. Sci. 2021, 29, 57–67. [Google Scholar]

- Tao, Y. Research about compensation for damage of automatic vehicle traffic accidents. J. Hunan Univ. 2018, 32, 136–141. [Google Scholar]

- Rimkutė, D.; Povylius, K. Civil and Criminal Liability for Damage Caused by Self-Driving Cars. In Teisės Mokslo Pavasaris; Vilnius University Press: Vilnius, Lithuania, 2021; pp. 182–210. [Google Scholar]

- Ghavami Pour Sereshkeh, M.; Mahmoudi, A. An Introduction to the Legal Frameworks of Criminal Liability for Artificial Intelligence Systems. Mod. Technol. Law J. 2025, 6, 209–232. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, Y. Dilemmas and Solutions in Applying Product Liability to Autonomous Vehicles. Open J. Leg. Sci. 2025, 13, 154–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chu, Y. The Impact of Artificial Intelligence on the Tort Legal System and its Response. Int. J. Educ. Humanit. 2024, 9, 199–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, F.; Wu, T. Reflections on the Subject of Civil Tort Liability in Autonomous Vehicle Traffic Accidents. J. Xinyu Univ. 2025, 30, 20–28. [Google Scholar]

- Widen, W.H.; Koopman, P. The Awkward Middle for Automated Vehicles: Liability Attribution Rules When Humans and Computers Share Driving Responsibilities. Jurimetrics 2023, 64, 41–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Standing Committee of the National People’s Congress of the People’s Republic of China. Road Traffic Safety Law of the People’s Republic of China 29 April 2021; Standing Committee of the National People’s Congress of the People’s Republic of China: Beijing, China, 2021. Available online: https://flk.npc.gov.cn/detail?id=ff8081817ab231eb017abd617ef70519 (accessed on 27 October 2025).

- National People’s Congress of the People’s Republic of China. Civil Code of the People’s Republic of China, Book on Tort Liability 28 May 2025; National People’s Congress of the People’s Republic of China: Beijing, China, 2025. Available online: https://flk.npc.gov.cn/detail?id=ff808081729d1efe01729d50b5c500bf (accessed on 27 October 2025).

- Standing Committee of Shenzhen Municipal People’s Congress. Shenzhen Special Economic Zone Regulations on Intelligent and Connected Vehicles (Arts. 53–54). 2022. Available online: https://www.szrd.gov.cn/v2/zx/szfg/content/post_966190.html (accessed on 27 October 2025).

- Ministry of Public Security of the People’s Republic of China. Road Traffic Safety Law (Draft Revision—Solicitation of Comments); Ministry of Public Security of the People’s Republic of China: Beijing, China, 2021. Available online: https://www.mps.gov.cn/n2254536/n4904355/c7787881/content.html (accessed on 27 October 2025).

- Soyer, B.; Tettenborn, A. Artificial Intelligence and Civil Liability—Do We Need a New Regime? Int. J. Law Inf. Technol. 2022, 30, 385–397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, L. Comparative Study on the Liability Rules for Traffic Accidents of Autonomous Vehicles in Local Regulations. Law Sci. Mag. 2025, 46, 22–37+2. Available online: https://d.wanfangdata.com.cn/periodical/CiBQZXJpb2RpY2FsQ0hJU29scjkyMDI1MTExNzE2MDExNxINZnh6ejIwMjUwMTAwMxoIZ3JhdmE4ZnY%3D (accessed on 1 December 2025).

- Lin, X.; Lee, C.-Y.; Fan, C.K. Exploring the Impacts of Autonomous Vehicles on the Insurance Industry and Strategies for Adaptation. World Electr. Veh. J. 2025, 16, 119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yeo, H.Y.; Yeo, R.S. Autonomous Vehicles and Insurance Law Principles: Navigating New Frontiers in Singapore. Singap. Acad. Law J. 2024, 36, 164–194. [Google Scholar]

- China TAIPING. White Paper on Insurance Innovation for Intelligent and Connected Vehicles; China TAIPING: Hong Kong China, 2024; Available online: https://www.cntaiping.com/news/110611.html (accessed on 26 November 2025).

- Yang, D. Legislation of Intelligent Connected Vehicles and Innovative Practice in Shenzhen. Urban Transp. China 2023, 3, 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Wei, C.; Zhao, J.; Sun, L. Achieving Regulatory Alignment for E2E Autonomous Driving in China: A Framework for Tort Liability and Data Governance. Comput. Law Secur. Rev. 2025, 59, 106192–106202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alhabib, R.; Yadav, P. Data Authorisation and Validation in Autonomous Vehicles: A Critical Review. Discov. Appl. Sci. 2025, 7, 735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mordor Intelligence. Autonomous Car Market Size & Share Analysis—Growth Trends & Forecasts (2025–2030); Mordor Intelligence: Hyderabad, India, 2024; Available online: https://www.mordorintelligence.com/industry-reports/autonomous-driverless-cars-market-potential-estimation (accessed on 26 November 2025).

- IDTechEx. Autonomous Vehicles Markets 2025–2045: Robotaxis, Autonomous Cars, Sensors; IDTechEx: Cambridge, UK, 2024; Available online: https://www.idtechex.com/en/research-report/autonomous-vehicles-markets-2025/1045 (accessed on 26 November 2025).

- Wan, D.; Peng, L. Autonomous Vehicle Acceptance in China: TAM-Based Comparison of Civilian and Military Contexts. World Electr. Veh. J. 2025, 16, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sever, T.; Contissa, G. Automated Driving Regulations—Where Are We Now? Transp. Res. Interdiscip. Perspect. 2024, 24, 101033–101051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeGuzman, C.A.; Mostafa, T.S.; Othman, K.; Donmez, B.; Abdulhai, B.; Shalaby, A.; Niece, J. What Influences Intention to Use a First-Mile/Last-Mile Automated Shuttle Service in a Suburban Area? A Case Study in Toronto, Canada. Transp. Plan. Technol. 2025, 48, 536–554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Federal Ministry for Digital and Transport (Germany). Germany Will Be the World Leader in Autonomous Driving; Federal Ministry for Digital and Transport: Berlin, Germany, 2021; Available online: https://www.bmv.de/SharedDocs/EN/Articles/DG/act-on-autonomous-driving.html (accessed on 26 November 2025).

- KPMG. Autonomous Vehicles Readiness Index 2020; KPMG: Amstelveen, The Netherlands, 2020; Available online: https://electricautonomy.ca/automakers/autonomous-vehicles/2020-07-07/kpmg-2020-autonomous-vehicles-readiness-index/ (accessed on 26 November 2025).

- GoAuto Premium. Getting Ready Index Names AV League Table; GoAuto Premium: Edmonton, AL, Canada, 2018; Available online: https://premium.goauto.com.au/getting-ready-index-names-av-league-table/ (accessed on 26 November 2025).

- Yu, Z.; Yu, Z.; Lu, Y.; Zhan, H.; Yu, Y.; Wang, Z. A Quantitative Legal Support System for Transnational Autonomous Vehicle Design. Drones 2025, 9, 316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chng, S.; Cheah, L. Understanding Autonomous Road Public Transport Acceptance: A Study of Singapore. Sustainability 2020, 12, 4974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- KPMG Thailand. Singapore Tops the List for AV Readiness as Self-Driving Vehicles Gain Momentum in the Wake of COVID-19; KPMG Thailand: Bangkok, Thailand, 2020; Available online: https://kpmg.com/th/en/home/media/press-releases/2020/07/press-release-avri-en.html (accessed on 26 November 2025).

- Tan, S.Y.; Taeihagh, A. Adaptive Governance of Autonomous Vehicles: Accelerating the Adoption of Disruptive Technologies in Singapore. Gov. Inf. Q. 2021, 64, 101546–101560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agencia Estatal Boletín Oficial del Estado. Real Decreto Legislativo 8/2004, de 29 de Octubre, por el que se Aprueba el Texto Refundido de la Ley Sobre Responsabilidad Civil y Seguro en la Circulación de Vehículos a Motor. 2004. Available online: https://www.boe.es/buscar/act.php?id=BOE-A-2004-18911 (accessed on 27 October 2025).

- UK Parliament. Road Traffic Act 1988; UK Parliament: London, UK, 2024. Available online: https://www.legislation.gov.uk/ukpga/1988/52/contents (accessed on 27 October 2025).

- UK Department for Transport; Driver and Vehicle Standards Agency. The Highway Code. 2025. Available online: https://www.gov.uk/guidance/the-highway-code/updates (accessed on 27 October 2025).

- UK Parliament. Automated Vehicles Act 2024, c.10. 2024. Available online: https://www.legislation.gov.uk/ukpga/2024/10/contents (accessed on 27 October 2025).

- German Bundestag and Bundesrat. Verkehrsvorschriften. 2024. Available online: https://datenbank.nwb.de/Dokument/79226_1b/ (accessed on 27 October 2025).

- Government of the French Republic. Code de la Route. 2021. Available online: https://www.legifrance.gouv.fr/codes/section_lc/LEGITEXT000006074228/LEGISCTA000043371833/ (accessed on 27 October 2025).

- Tennessee General Assembly. 2024 Tennessee Code. 2021. Available online: https://law.justia.com/codes/tennessee/title-55/chapter-30/section-55-30-106/ (accessed on 27 October 2025).

- European Union. Directive (EU) 2024/2853 on Liability for Defective Products (repealing 85/374/EEC). 2024. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/eli/dir/2024/2853/oj/eng (accessed on 27 October 2025).

- National Assembly of the Republic of Korea. Compulsory Motor Vehicle Liability Security Act. 2016. Available online: https://elaw.klri.re.kr/eng_mobile/viewer.do?hseq=40982&key=4&type=sogan (accessed on 27 October 2025).

- National Diet of Japan. Japan’s Road Traffic Act. 2024. Available online: https://perma.cc/GAU9-HY5J (accessed on 27 October 2025).

- Parliament of Singapore. Road Traffic Act 1961. 2021. Available online: https://sso.agc.gov.sg/Act/RTA1961 (accessed on 27 October 2025).

- MacCarthy, M. Setting the Standard of Liability for Self-Driving Cars. 2025. Available online: https://www.brookings.edu/articles/setting-the-standard-of-liability-for-self-driving-cars/ (accessed on 27 October 2025).

- UK Parliament. Automated and Electric Vehicles Act 2018. 2018. Available online: https://www.legislation.gov.uk/ukpga/2018/18/pdfs/ukpga_20180018_en.pdf (accessed on 27 October 2025).

- Australian National Transport Commission. Automated Vehicle Safety Reforms, Public Consultation. 2024. Available online: https://www.ntc.gov.au/sites/default/files/assets/files/Automated%20vehicle%20safety%20reforms%20April%202024%20-%20Copy.pdf (accessed on 27 October 2025).

- Geistfeld, M.A. Civil Liability for Motor Vehicle Crashes in the United States: From Conventional Vehicles to Autonomous Vehicles. In Autonomous Vehicles and Civil Liability in a Global Perspective, 1st ed.; Data Science, Machine Intelligence, and Law; Steege, H., Caggiano, I.A., Gaeta, M.C., Bodungen, B., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2024; Volume 3, pp. 91–107. [Google Scholar]

- Abraham, K.S.; Rabin, R.L. Automated Vehicles and Manufacturer Responsibility for Accidents: A New Legal Regime for a New Era. Va. Law Rev. 2019, 105, 127–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Australian National Transport Commission. Guidelines for Trials of Automated Vehicles in Australia 2023. 2023. Available online: https://www.ntc.gov.au/sites/default/files/assets/files/Guidelines%20for%20trials%20of%20automated%20vehicles%20in%20Australia%202023.pdf (accessed on 27 October 2025).

- Government of Ontario. Negligence Act, R.S.O. 1990, c. N.1. 2004. Available online: https://www.ontario.ca/laws/statute/90n01 (accessed on 27 October 2025).

- ICV TA&K. 2024 Will Be a Milestone Year for Global Intelligent Driving, with China Set to Lead the Global Progress. 2024. Available online: https://www.icvtank.com/newsinfo/968952.html (accessed on 27 October 2025).

- Shanghai Securities Journal. By September 2024, China Had Designated 32,000 Kilometres of Test Roads for Intelligent Connected Vehicles. 2024. Available online: https://www.sohu.com/a/816462753_120988576 (accessed on 27 October 2025).

- Ministry of Industry and Information Technology of the People’s Republic of China; Ministry of Public Security of the People’s Republic of China; Ministry of Natural Resources of the People’s Republic of China; Ministry of Housing and Urban-Rural Development of the People’s Republic of China; Ministry of Transport of the People’s Republic of China. Notice on Implementing the Pilot Program of Applying “Vehicle-Road-Cloud Integration” to Intelligent Connected Vehicles. 2024. Available online: https://www.gov.cn/zhengce/zhengceku/202407/content_6965771.htm (accessed on 27 October 2025).

- Qianzhan Industry Research Institute. Major Update: Policy Summary, Interpretation, and Development Target Analysis for China’s Driverless Vehicle Industry in 2024 and across 31 Provinces or Municipalities—The Entire Intelligent Vehicle Value Chain Is Poised to Benefit. 2024. Available online: https://bg.qianzhan.com/trends/detail/506/240415-cbc5526c.html (accessed on 27 October 2025).

- Ministry of Industry and Information Technology of the People’s Republic of China; State Administration for Market Regulation. Notice on Further Strengthening Access, Recall, and Over-the-Air Software Update Management for Intelligent and Connected Vehicles. 2025. Available online: https://www.gov.cn/zhengce/zhengceku/202503/content_7009422.htm (accessed on 26 November 2025).

- State Administration for Market Regulation. Circular on National Product Recalls in 2024. 2025. Available online: https://www.samr.gov.cn:8890/zw/zfxxgk/fdzdgknr/zlfzs/art/2025/art_cdc38c75aad549d88af6a4c71a4d0ad2.html (accessed on 26 November 2025).

- J3016_202104; Taxonomy and Definitions for Terms Related to Driving Automation Systems for On-Road Motor Vehicles. SAE International: Warrendale, PA, USA, 2021. Available online: https://www.sae.org/standards/j3016_202104-taxonomy-definitions-terms-related-driving-automation-systems-road-motor-vehicles (accessed on 27 October 2025).

- Federal Ministry for Digital and Transport (Germany). Act to Amend the Road Traffic Act and the Compulsory Insurance Act—Act on Autonomous Driving. 2021. Available online: https://media.offenegesetze.de/bgbl1/2021/bgbl1_2021_48.pdf (accessed on 1 December 2025).

- République Française. Ordonnance No. 2021-443 of 14 April 2021 Relative to the Criminal Liability Regime Applicable to the Circulation of a Vehicle with Delegated Driving and Its Conditions of Use, Arts. 1–8. 2021. Available online: https://www.legifrance.gouv.fr/eli/ordonnance/2021/4/14/2021-443/jo/texte (accessed on 1 December 2025).

- République Française. Décret No. 2021-873 of 29 June 2021 Implementing Ordonnance No. 2021-443 of 14 April 2021 on the Criminal Liability Regime Applicable in the Event of the Circulation of a Vehicle with Delegated Driving and Its Conditions of Use, Arts. 1–10. 2021. Available online: https://www.legifrance.gouv.fr/eli/decret/2021/6/29/2021-873/jo/texte (accessed on 1 December 2025).

- Tennessee General Assembly. Automated Vehicles Act, Tennessee Code Annotate. 2017. Available online: https://law.justia.com/codes/tennessee/2018/title-55/chapter-30/ (accessed on 1 December 2025).

- European Union. Regulation (EU) 2018/858 on the Approval and Market Surveillance of Motor Vehicles and Their Trailers. 2018. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/eli/reg/2018/858/oj/eng (accessed on 27 October 2025).

- IATF 16949:2016; Quality Management System Requirements for Automotive Production and Relevant Service Parts Organizations. International Automotive Task Force (IATF): Versailles, France, 2024. Available online: https://www.iatfglobaloversight.org/?s=IATF+16949%3A2016 (accessed on 27 October 2025).

- Sun, H.; Zhang, L.; Ji, G. Research and Prospects on the Standards System and Key Standards for Intelligent and Connected Vehicles. J. Automot. Saf. Energy 2024, 15, 795–812. [Google Scholar]

- Jiang, C. Evolutionary Pathway and Institutional Innovation in Local Legislation for Autonomous Vehicle–Infrastructure Cooperation: From Road Testing to Commercial Deployment. Open J. Leg. Stud. 2025, 13, 1841–1851. [Google Scholar]

- Evas, T. A Common EU Approach to Liability Rules and Insurance for Connected and Autonomous Vehicles; European Parliament: Brussels, Belgium, 2018; Available online: https://www.europarl.europa.eu/RegData/etudes/STUD/2018/615635/EPRS_STU(2018)615635_EN.pdf (accessed on 1 December 2025).

- Schellekens, M. No-Fault Compensation Schemes for Self-Driving Vehicles. Law Innov. Technol. 2018, 10, 314–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chatzipanagiotis, M.; Leloudas, G. Automated Vehicles and Third-Party Liability: A European Perspective. Univ. Ill. J. Law Technol. Policy 2020, 2020, 109–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.; Han, H.; You, Y.; Cho, M.-J.; Hong, J.; Song, T.-J. A Comprehensive Traffic Accident Investigation System for Identifying Causes of the Accident Involving Events with Autonomous Vehicles. J. Adv. Transp. 2024, 2024, 9966310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Policy | Driver | Owner | Manager | Manufacturer | Seller | Test Safety Officer | Passenger | Other |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Regulations of Shenzhen Special Economic Zone on the Administration of Intelligent Connected Vehicles | Applicable | Applicable | Applicable | Applicable | Applicable | Not applicable | Not applicable | Not applicable |

| Provisions of Pudong New Area of Shanghai Municipality on Promoting the Innovative Application of Driverless Intelligent Connected Vehicles | Not applicable | Applicable | Applicable | Applicable | Not applicable | Not applicable | Not applicable | Partially applicable, including automatic driving system developer, Vehicle manufacturer, Equipment provider |

| Regulations of Wuxi Municipality on Promoting the Development of the Internet of Vehicles | Not applicable | Not applicable | Not applicable | Not applicable | Not applicable | Not applicable | Not applicable | Partially applicable, including Relevant entities in the internet of vehicles sector |

| Regulations of Suzhou Municipality on Promoting the Development of the Intelligent Internet of Vehicles | Applicable | Applicable | Applicable | Applicable | Applicable | Not applicable | Applicable | Not applicable |

| Decision on Promoting the Development of Vehicle-to-Everything and Intelligent Connected Vehicles | Applicable | Applicable | Applicable | Applicable | Applicable | Not applicable | Applicable | Not applicable |

| Measures of Yangquan Municipality for the Administration of Intelligent Connected Vehicles | Applicable | Applicable | Applicable | Not applicable | Not applicable | Applicable | Not applicable | Partially applicable, including entities responsible for testing, pilot application and pilot operation |

| Regulations of Hangzhou Municipality on Promoting the Testing and Application of Intelligent Connected Vehicles | Applicable | Applicable | Applicable | Not applicable | Not applicable | Applicable | Not applicable | Partially applicable, including testing entities and application entities |

| Regulations of Hefei Municipality on Promoting the Application of Intelligent Connected Vehicles | Applicable | Applicable | Applicable | Not applicable | Not applicable | Not applicable | Not applicable | Not applicable |

| Regulations of Guangzhou Municipality on the Innovative Development of Intelligent Connected Vehicles | Applicable | Not applicable | Not applicable | Not applicable | Not applicable | Applicable | Not applicable | Partially applicable, including users of intelligent connected vehicles |

| Regulations of Wuhan Municipality on Promoting the Development of Intelligent Connected Vehicles | Applicable | Applicable | Applicable | Not applicable | Not applicable | Applicable | Not applicable | Partially applicable, including parties, Other relevant liable entities |

| Beijing Autonomous Vehicle Regulations | Not applicable | Not applicable | Not applicable | Not applicable | Not applicable | Applicable | Not applicable | Not applicable |

| State | Liability Regimes (L0–L2) | Liability Regimes (L3–L5) |

|---|---|---|

| China | Driver liability regime | Driver liability regime |

| Spain | Driver liability regime | |

| United Kingdom | System Liability Regime | |

| Germany | Manufacturer and operator liability | |

| Japan | ||

| France | ||

| South Korea | ||

| Singapore | ||

| Tennessee (United States) | ||

| United States | Composite liability regime | |

| Canada | ||

| Australia |

| Automation Level | Applicable Scenario | Controlling Entity | Legal Liability |

|---|---|---|---|

| Human Driving (L0–L2) | Any road | Driver | Driver |

| Driving Automation (L3) | Highways with well-developed infrastructure, or urban roads opened for pilot operation | Driver and the automated driving system | The driver, or the manufacturer or the operator |

| High-grade rural roads or urban roads with incomplete infrastructure | Driver and the automated driving system | The driver and the manufacturer, or the operator, jointly or severally | |

| Roads that do not meet the conditions for automated driving | Driver with a driver-assistance system | Driver | |

| High and Full Driving Automation (L4–L5) | Any road | Automated driving system | Designated authorised entities assume safety, compliance and supervisory responsibilities before the crash. Manufacturers or operators bear the primary responsibilities after the crash |

| Stage | Liability Regime | Legislation | Industry Standards | Local Governance | Insurance |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Phase I: Present—short term |

|

|

|

|

|

| Phase II: Medium term |

|

|

|

|

|

| Phase III: Long term |

|

|

|

|

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Published by MDPI on behalf of the World Electric Vehicle Association. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Ba, Z.; Zhao, Z.; Zhang, B. Liability for Autonomous Vehicle Torts: Who Should Be Held Responsible? World Electr. Veh. J. 2025, 16, 665. https://doi.org/10.3390/wevj16120665

Ba Z, Zhao Z, Zhang B. Liability for Autonomous Vehicle Torts: Who Should Be Held Responsible? World Electric Vehicle Journal. 2025; 16(12):665. https://doi.org/10.3390/wevj16120665

Chicago/Turabian StyleBa, Zhuo, Ziyu Zhao, and Bokang Zhang. 2025. "Liability for Autonomous Vehicle Torts: Who Should Be Held Responsible?" World Electric Vehicle Journal 16, no. 12: 665. https://doi.org/10.3390/wevj16120665

APA StyleBa, Z., Zhao, Z., & Zhang, B. (2025). Liability for Autonomous Vehicle Torts: Who Should Be Held Responsible? World Electric Vehicle Journal, 16(12), 665. https://doi.org/10.3390/wevj16120665