1. Introduction

Technological progress in the world has, of late, been conspicuously led by artificial intelligence (AI), whose applicability is expanding exponentially in all facets of life and business. The manufacturing and automobile industry have been revolutionized by AI-powered robotics, among other applications. The electric vehicle (EV) industry, a step ahead of the conventional auto industry in terms of technology absorption, is better equipped to exploit AI for efficient processes, smoother logistics/supply chains, vendor management, and better customer experience.

A logical question: how significant is the influence of AI on sustainability in the EV industry, and for the purposes of this study, the Indian electric two-wheeler (IE2W) industry? With increasing focus on the environment and sustainability, governments and industries will need to address these concerns comprehensively, and AI will play a huge role going forward.

India is the second top net crude oil (including products) importer (85–88% of its oil needs), having imported 205.3 MT in 2019 [

1,

2,

3,

4], adversely affecting geopolitical resilience and self-sufficiency [

5]. Proliferation of EVs will accelerate the adoption of a circular economy (CE), especially in the IE2W industry. This aligns with government regulations and policies nudging the industry to adopt green norms, like FAME (Faster Adoption and Manufacture of Hybrid and Electric Vehicles scheme 2015), the FAME II scheme [

6], and the Government of India (GoI) target of ‘E-Vehicles Only’ on the roads by 2030 [

7,

8]. The Indian EV market value of USD 54.41 billion in 2025 could ascend to USD 110.7 billion by 2029, with a compounded annual growth rate (CAGR) of 19.44% over 2025–2029 [

9]. Electric bikes and scooters are expected to exponentially grow in sales [

10], displaying the Indian penchant for two-wheelers (2W) and three-wheelers (3W) rather than four-wheelers/cars (4W) [

11]. The E2W market CAGR of 29.07% will lead to USD 1.3 billion in sales by 2028 [

12]. Dynamic government policies should complement this [

13,

14].

India has 14 of the 20 most polluted cities in the world, which includes 6 of the 10 most polluted cities in the world [

15,

16]. Pollution-related fatalities of 12.5 lakh people annually are unacceptable [

17]. In India (the world’s 3rd largest auto market) [

18], 2Ws account for 75.5% of the annual total production of 28.4 million [

19]. In FY 2023–2024, 2W sales increased to 1.80 crore (cr) units (from 1.59 cr in FY 2022–2023) [

19]. Indian 2Ws account for over 20% of the total CO

2 emissions and about 30% of urban particulate emissions (PM2.5) [

20]. Indian 2Ws cover a daily average of 27–33 km (maximum 86 km), covering 8800 km annually on average [

21,

22,

23], and thus are a major source of pollution, which can be offset by a higher E2W production and penetration [

24].

Environmentally, the battery supply chain is one of the gray areas of the IE2W industry, as with any Indian EV (IEV) industry. This needs to be addressed, and AI could be the catalyst to achieve CE and sustainability.

2. Significance and Scope of the Study

This review aims to analyze the extent to which the IE2W industry, still in its infancy, will benefit from AI in the area of CE and sustainability. This paper will highlight the path forward in exploiting AI to enhance value for the IE2W industry, the government, the public, and the environment. The paper will scrutinize the literature available on EV adoption barriers, the government’s role through regulations and norms, sustainability, sustainable supply chain management (SSCM), green supply chain management (GSCM), and waste management, in the context of AI and its applicability for the IE2W industry. Due to its restricted scope as a review, this study will not focus on quantitative/empirical data pertaining to the IE2W industry or specific performance data from IE2W companies.

The following outcomes are expected:

Highlighting the positive effects of AI-driven technology in vendor partnerships and supply chain management, and highlighting the ability of the IE2W industry to meet the government’s environmental/sustainability targets and stipulations;

Critically examining AI pitfalls/paradoxes;

Draw on the interrelationship between AI, CE, sustainability, the IE2W industry, and green innovation;

Assessing the impact of government support for AI in the IE2W industry;

Aligning the IE2W industry and its operations to enhance CE;

Laying the foundation for research on differing variables like AI-driven technology, the human aspect, investment, and operations, vis-à-vis IE2W performance;

Creating awareness of AI applications for solutions to supply chain challenges in the IE2W sector;

Academic collaboration for R&D on AI-absorption for sustainability in the IEV/IE2W industry;

Helping interested parties from not only the IE2W industry but also other industries regarding the aspects mentioned above.

3. Sources and Classification of Literature

A literature search was conducted systematically to identify relevant peer-reviewed studies examining the application of AI principles to the CE and sustainability challenges within the EV industry. The primary electronic database searched was Scopus to capture contemporary research aligned with the rapid growth of AI and the EV market. We employed two search strings whose results are summarized in

Table 1. An initial screening was carried out to review the titles and abstracts of the retrieved records. Inclusion criteria focused on articles published in English between January 2016 and the present (November 2025) and empirical research published in peer-reviewed journals that demonstrated the use of AI technologies to enhance CE principles (e.g., product life extension, waste minimization, and resource recovery) within the EV or EV battery value chain. Exclusion criteria filtered out theoretical papers, policy documents, non-peer-reviewed sources, and studies focused exclusively on internal combustion engine vehicles or general manufacturing processes. The initial search yielded 386 records (see search string 2 results), which were refined to 171 records when screened for India/Indian context. In addition, considering the relatively new nature of the topic and its focus on India, other material (as enumerated in the references section), like webpages, news articles, and reports, has also been consulted.

The findings are enumerated in the ensuing paragraphs, and will cover the IE2W industry and sustainability; IE2W in the CE; CE in IE2W industry; AI in the CE of the IE2W industry; challenges, opportunities, and recommendations for AI in CE of IE2W; the identified gaps and setting up a conceptual framework; and, the exploration of scope and potential for future research.

4. The IE2W Industry and Sustainability

4.1. How Green Are EVs?

EVs and E2Ws are largely understood to be green and environmentally friendly, but the following information is relevant:

Components manufacturing may utilize non-green technologies and processes [

25,

26,

27,

28].

Raw materials/minerals used in batteries, like lithium, are dependent on the mining industry, which has a negative impact on the environment. The inherent significant geopolitical dynamics also bear mention [

29,

30,

31,

32,

33].

The electricity used for EVs may come from coal-fired power plants or through other non-green technologies [

34,

35,

36].

Since ICE vehicles will continue to be used till their end-of-lifecycle (EoL), EVs will not be able to replace ICE completely any time soon. There is also the issue of barriers to EV adoption, like range anxiety [

8,

37,

38], safety aspects (batteries’ fire hazard) [

39], not-yet-matured service support, inadequacy of charging infrastructure, etc. Further, some players in the automobile industry look ahead at solar power or hydrogen as a propulsion source, thus discouraging a whole-hearted shift to EVs [

40].

4.2. Battery Environmental Issues and Potential for Recycling

Battery waste management (e-waste) [

41,

42,

43] and recycling can boost CE, promote sustainability, and reduce reliance on rare earths and minerals [

44,

45,

46,

47].

The rapid proliferation of EVs raises the challenge of managing EoL EV batteries (EoLEVB). Batteries’ second-life potential [

48,

49] and reverse supply chain [

50] can help. Lithium-ion batteries (LIBs) contain hazardous materials that cause environmental and health risks unless properly disposed of, thereby highlighting the viability of recycling. While the quantum of EV battery waste by 2030 is difficult to determine, its exponential growth is certain. Indian EV battery waste data year-wise from 2020 onwards is not accurately determinable, primarily due to the domination of the informal sector and the absence of proper safeguards. To cite an example, as of 2020, a mere 10% of the total 70–90% collected retired batteries in India was performed by formal waste management entities. Improper disposal often leads to severe soil/water contamination through toxic leaching. Ironically, the government’s 18% GST on retired batteries in the formal sector has remained unchanged even after the reduced GST norms of the Indian government took effect beginning on 22 September 2025. This incentivizes non-compliance, which leads to black mass export (battery anode and cathode remnants), causing the loss of precious minerals and material. From October 2022 to 22 September 2023, black mass export in India totaled approx. 350 tons of cobalt, 71.7 tons of lithium, and 215 tons of nickel [

51].

At present, India recycles <5% of its LIBs formally [

41]. In spite of an estimated recycling capacity of approx. 83 kilotons per annum (KTPA), 95% of used batteries were handled by the informal sector or ended up in landfills [

52]. Some companies, however, have made notable strides, including Tata Chemical’s battery recycling plant (2019) [

53] and Attero’s facility in Telangana [

54], which will inspire the IE2W industry to follow suit.

India’s Battery Waste Management Rules (BWMRs) 2022 [

55], seek to increase recycling and material recovery, setting progressive collection targets of up to 70%, and material recovery: beginning at 5% for FY 2027–2028, 10% by FY 2028–2029, 15% by FY 2029–2030, and 20% by 2030–2031 and onwards [

55]. The automobile industry’s internal goals of 95% recycling by 2030 are also noteworthy [

56]. NITI Aayog’s key projections include the following [

57]:

4.3. Vendor Management Issues

Various challenges to setting up a proper SSCM for the Indian automobile/IEV/IE2W industry need resolution [

61,

62,

63] through concepts like green logistics, reverse logistics, etc., [

64,

65]. Studies on SSCM in the Indian automotive industry, from multiple stakeholders’ views [

66,

67], factors that warrant sustainability in this competitive industry [

68], automotive SSCM in the context of CE, and setting up a strategic framework [

69,

70], have been carried out. Vendor management challenges and opportunities, resilience, and strategy have been covered in the transition to EVs [

71,

72]. Sustainability challenges in the EV battery value chain, like resource sufficiency, geographical distribution, regulations, policy, etc., [

71,

73], reveal that demand for lithium, cobalt, nickel, and graphite will go up 26×, 6×, 12×, and 9x, respectively, in the period from 2021 to 2050. IE2W manufacturers need to work collaboratively with vendors to ensure SSCM in production to meet global environmental norms. Outsourcing is an important aspect of vendor management that needs to be holistically researched to improve the performance of the IEV/IE2W industries [

74,

75,

76,

77].

5. The Circular Economy in IE2W

5.1. The Circular Economy (CE)

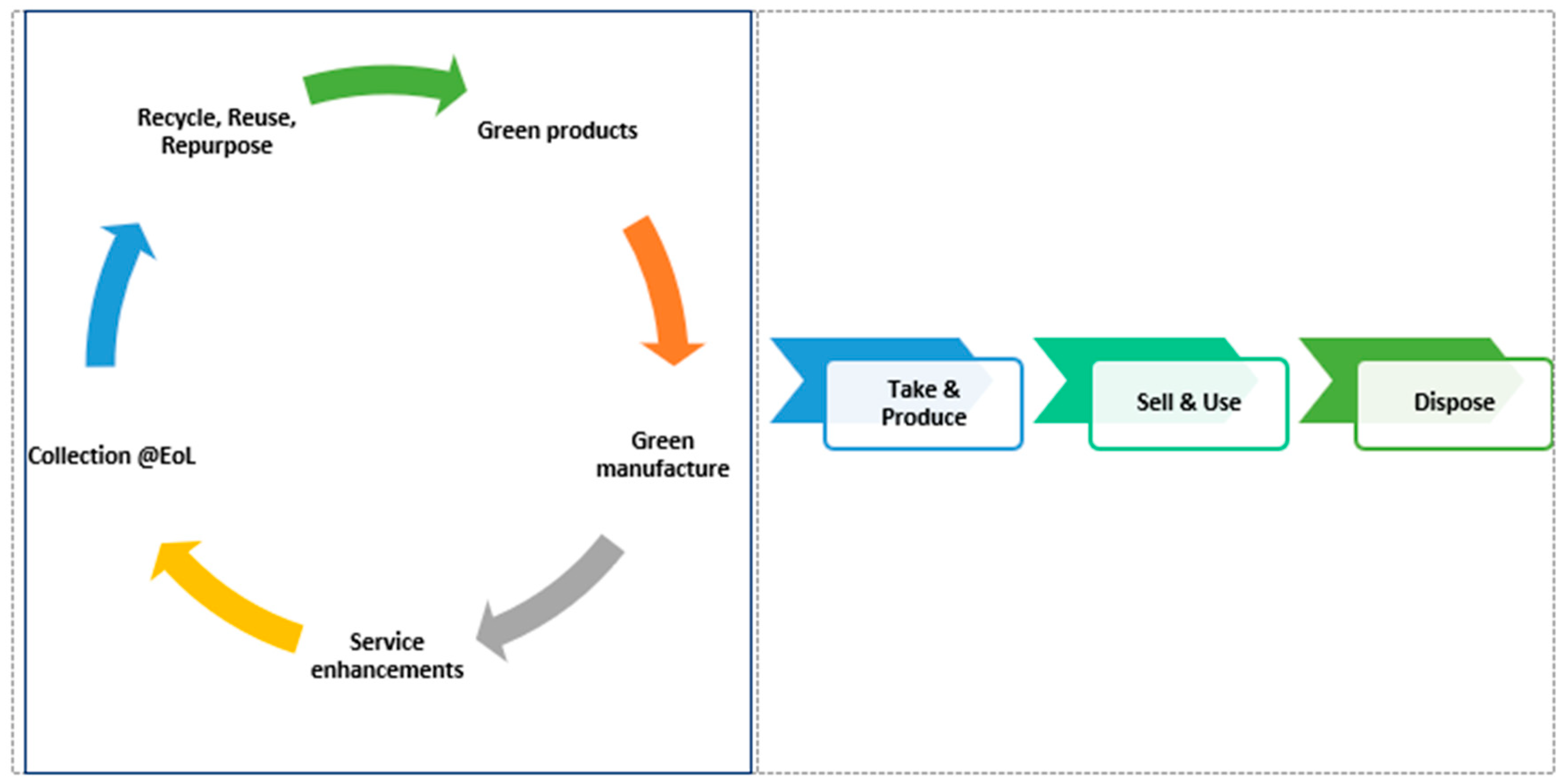

The CE is an economic model seeking to change the traditional “take-make-waste” linear economy [

78] by eliminating waste and pollution, retaining products and materials in use, and regenerating natural systems. It is a paradigm shift in how we design, produce, and consume goods. It focuses on closing material loops and decoupling economic growth from the consumption of finite resources [

79]. CE principles (graphically represented in

Figure 1) [

80,

81,

82,

83,

84] are reinforced by the 3Rs (reduce, reuse, and recycle) and strategies to refurbish, remanufacture, and repurpose [

79]. Digital technologies could be used to advance CE practices [

85] and demonstrate how AI can play an empowering role in multifarious areas, like the use of green raw materials, green production, high service standards, promoting product longevity, and ensuring collection at EoL for the 3R process. CE and sustainability are intertwined and cannot be seen in isolation [

78,

86,

87,

88].

5.2. Green SCM and Green Manufacturing

The automotive industry, in general, and specifically the IEV/IE2W industry in India, needs to incorporate green innovation [

89] and the CE [

90] in order to ensure sustainability and sustainable development [

91,

92] through reduced resource usage, enhanced efficiency, new market opportunities, and profitability. Green SCM (GSCM) is an alternate concept, but not entirely different from SSCM [

93,

94], and research shows that both internal and external GSCM can positively impact performance and organizational profitability [

95,

96,

97,

98,

99].

GSCM implies that all stages of the supply chain, including green design, suppliers, purchase, manufacturing, packaging, warehousing, transportation, and even customers, are entirely green (portrayed graphically for the IE2W in

Figure 2). This study finds that not much study of GSCM concepts specific to the EV/E2W industry has been performed, and certainly not in the IEV/IE2W industry. It is, however, pertinent that the tenets of GSCM (like most supply chain aspects and logistics) are not much different between the automobile and the EV/E2W industries, and hence the empirical material on GSCM in the Indian automobile industry [

100] will continue to be relevant to the IEV/IE2W industry too.

Table 2 identifies GSCM practices that are most pertinent and impactful for the IE2W industry.

5.3. Green Practices of IE2W Companies

Some leading IE2W OEMs have adapted to CE significantly. Two examples follow.

5.3.1. Ather Energy

Ather Energy seeks to distinguish itself in technology innovation, effective battery management, and in contributing to the country’s clean mobility ecosystem. The firm has a memorandum of understanding (MoU) with the Department for Promotion of Industry and Internal Trade (DPIIT) [

106,

107], Ministry of Commerce and Industry, to offer strategic mentorship for high-tech startups and give infrastructure support for emerging EV companies, joint innovation programs (such as the Bharat Startup Grand Challenge), and talent and skill development initiatives. It has developed a proprietary battery management system (BMS) to optimize battery performance and ensure battery life, apart from initiatives like “70% battery health assurance” and extended warranty programs, offering coverage for 5 years/60,000 km or extended 8 years/80,000 km (whichever comes first), enhancing consumer confidence. The company has been certified for battery recycling on the Central Pollution Control Board’s (CPCB) online portal. Ather follows a policy of delaying EoLEVB to reduce waste and increase reliability.

5.3.2. Ola Electric

With a world-class “FutureFactory” project in Krishnagiri, Tamil Nadu, Ola Electric has developed one of the world’s most environmentally compliant carbon-negative production facilities. This encompasses a 100-acre dedicated forest plus 2 acres of forest internal to the plant itself. Automated production is aided by 3000+ AI-driven robots working alongside employees to produce 10 million two-wheelers per year [

108]. A vast solar array on the factory roofs further boosts sustainability.

Ola Electric is also registered for battery waste recycling on the Central Pollution Control Board (CPCB) portal to comply with BWMR 2022 [

109,

110]. A recent initiative was the announcement of using non-rare-material magnets in production, in addition to the operationalization of its own battery plant, “GigaFactory”, which produces the BharatCell.

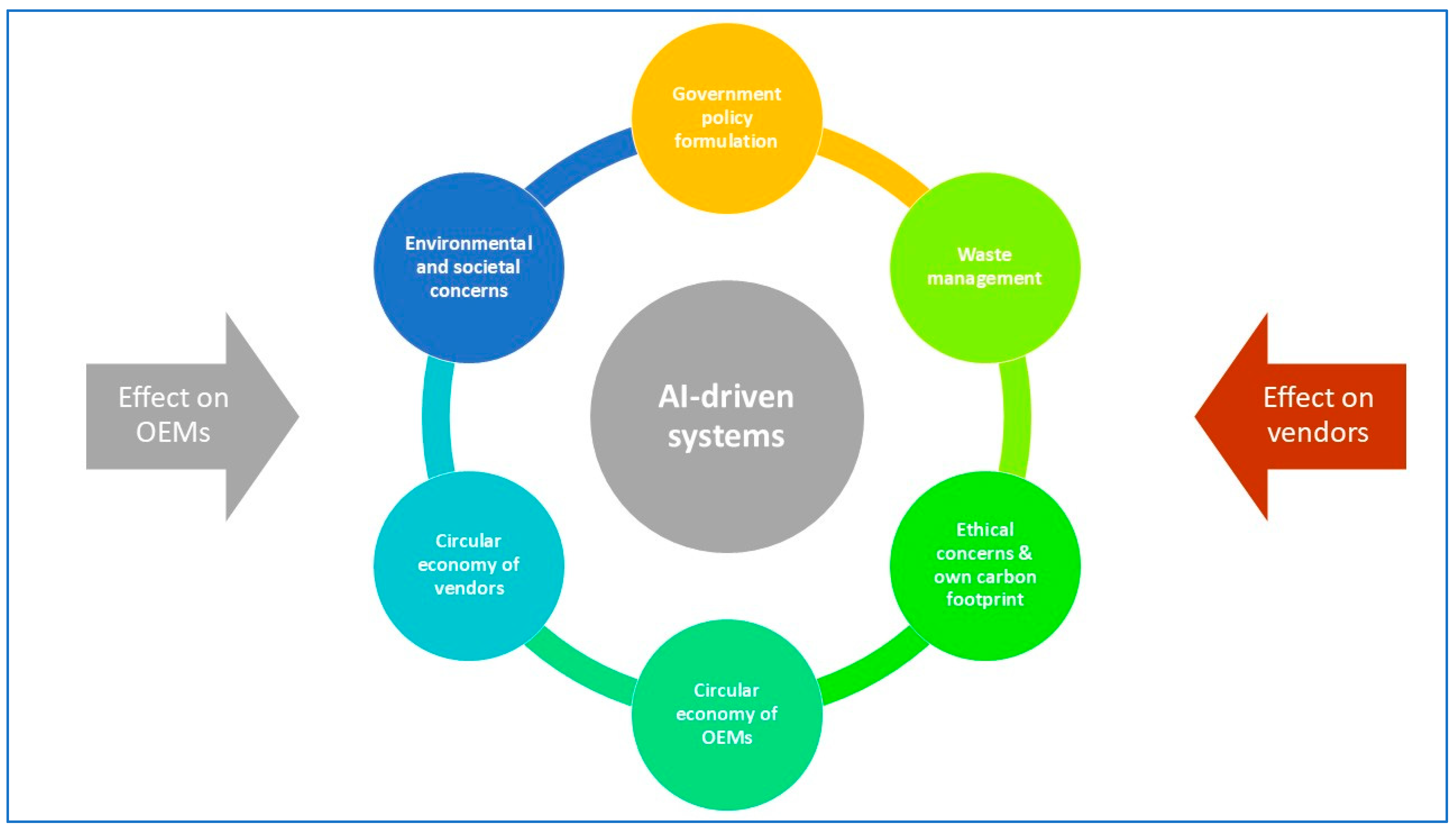

5.4. Interrelationship Between AI and CE/Sustainability in the IE2W Industry

Figure 3 portrays the interdependence between the parameters influencing CE, emphasizing how AI-driven systems can impact each aspect of the IE2W industry. Environmental and societal concerns, CE of vendors/OEMs, and the adherence by both vendors/OEMs to environmental regulations and waste management, can all benefit from AI-driven systems and processes, notwithstanding their own carbon footprints and some ethical concerns regarding AI (discussed later). In this milieu, it would affect and be affected by vendors and OEMs separately.

5.5. Critical Examination of Government Policies, Regulations, and Implementation

Indian government EV policies target adherence to CE principles. Some policies include BWMR 2022 [

55] to promote the following: battery recycling [

111]; extended producer responsibility (EPR) to make manufacturers responsible for collecting and recycling/refurbishing EoLEVB; setting collection/recycling targets projected at 70% and recycling targets of 90% by 2027; recycled content in new batteries (5% by FY 2027–2028 and 20% by FY 2030–2031); a ban on landfill/burning, encouraging second-life applications, traceability initiatives, reducing resource import dependence, and productivity linked incentive schemes (PLI) facilitating domestic battery ecosystem; and, “Guidelines for Prevention and Regulation of Greenwashing or Misleading Environmental Claims, 2024” issued by the Central Consumer Protection Authority (CCPA) under the Consumer Protection Act, 2019 [

112].

However, while the policies are sound in theory, the problem lies primarily with inadequate implementation. Gaps in implementation include continued informal sector dominance (90% of battery-related e-waste), non-availability of disposal methods (pyrometallurgical or hydrometallurgical plants, which need high capital investments), and technological lag. Due to inadequate collection infrastructure, storage, transportation, and advanced recycling of EoLEVB, less than 5% of LIBs are formally recycled. Other deficiencies include inadequate reverse logistics systems, missing battery lifecycle tracking mechanisms, like battery passports or battery aadhar [

113], a lack of a standardized battery design, and low consumer awareness.

The government needs to strengthen enforcement mechanisms [

114], make capital investments in recycling infrastructure, address disincentives like GST on waste batteries and low EPR price, formalize the informal sector, enforce standardized battery designs, and enhance public awareness on the subject. It is also imperative that a continuous assessment of the CE policies is made for periodic review [

115] to monitor the impact of governmental incentives [

116,

117,

118,

119,

120]. The government needs to strictly enforce penalties for ‘greenwashing’ violations of IE2W companies [

112,

121].

Since effective government policies will promote EV adaptability, these need to be diligently designed and implemented [

122]. The role of AI in the framing of policy and implications for regulations and policy is covered separately in this review.

6. AI in the CE of the IE2W Industry

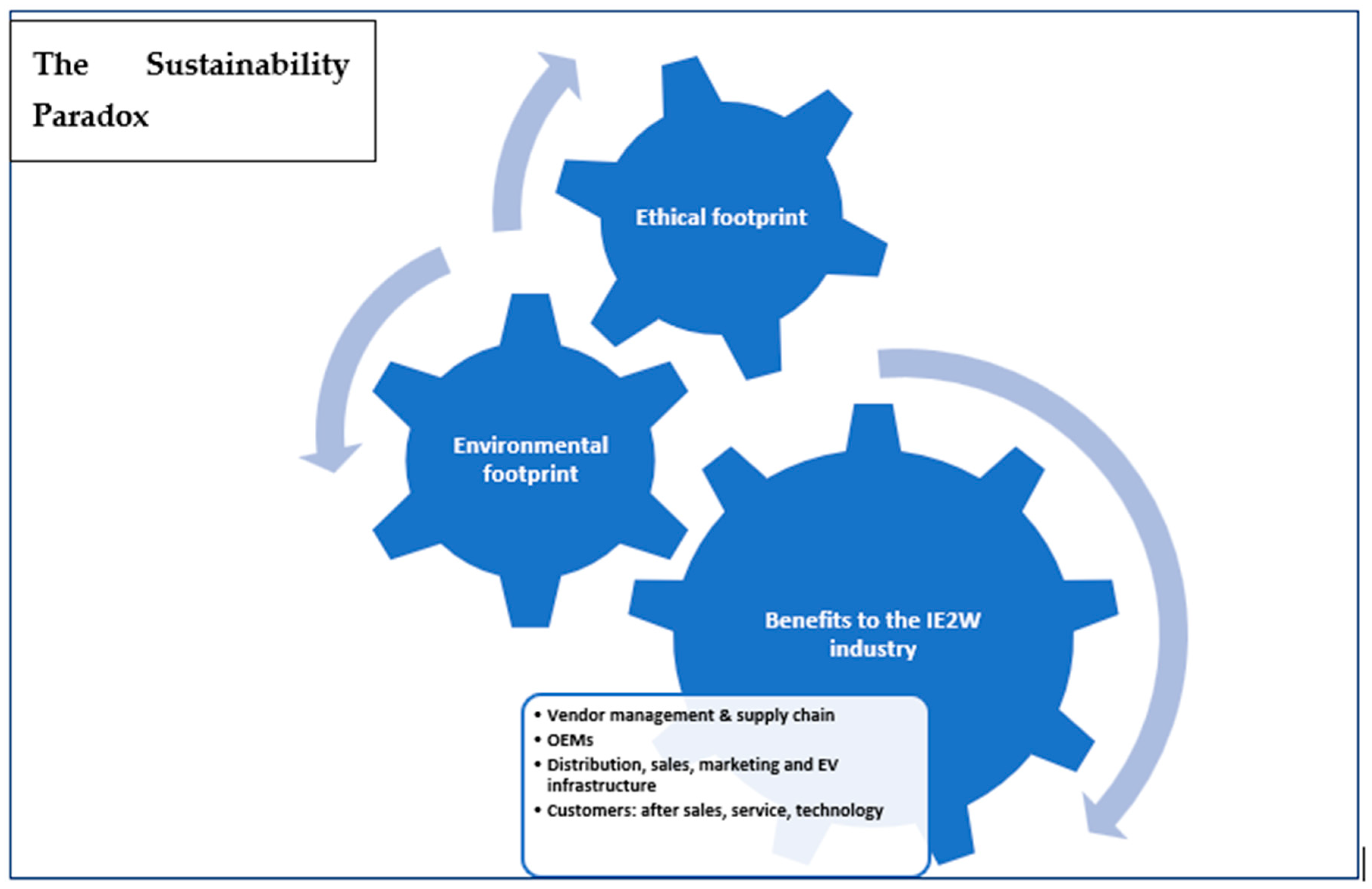

6.1. The Sustainability Paradox: Addressing Environmental and Ethical Footprints of AI

AI has both an environmental and ethical footprint, which creates a sustainability paradox. It positively benefits the vendors and vendor management; manufacturing for OEMs and vendors; distribution, sales, marketing, and creation of EV infrastructure; and, the customers, who receive sustainable mobility, good after-sales service, and other technological benefits like advanced driver assistance systems (ADASs), over-the-air (OTA) updates, etc.

On the flip side, AI’s own sustainability, its environmental and ethical footprints, come under question, calling for a critical assessment of its impact. The environmental costs primarily stem from the immense computational power required to train and deploy advanced AI models, especially large language models (LLMs), that even India plans to acquire. This will need a lot of power, leading to higher CO

2 emissions, since roughly 73–77% of India’s total energy comes from coal. Figures for May 2025 show coal as 46.12% of the installed capacity, but it is much higher in terms of actual generation [

123]. Data centers are the backbone of AI operations and contribute 1% of global greenhouse gas emissions. This figure is expected to double by 2026. AI hardware like graphics processing units (GPUs) needs energy-intensive manufacturing that contributes significantly to electronic waste [

124]. Cooling GPUs in data centers requires an enormous amount of water, straining local societies further. A propensity to keep releasing newer versions ignores the energy wasted in training the previous models.

Figure 4 explains how the benefits offered by AI to the IE2W sector may at times be at odds with its environmental, societal, and ethical footprints. Algorithmic bias occurs from incorrect training data, poor feature selection, or systemic discrimination existing in legacy datasets [

125] and may discriminate against some groups of people [

125], reinforcing societal biases and reducing public trust in AI. Data privacy is another factor, as AI-driven systems in EVs and fleet management collect, store, and process massive amounts of personal data, like driving patterns and location information [

125].

Evidently, while AI can prove invaluable to the IE2W sector in multiple ways, the benefits will need to be weighed in terms of this sustainability paradox [

126]. The government should put in place a strong regulatory framework with robust data ethics frameworks and privacy-by-design principles [

127] to promote transparency and accountability and to counter its ill-effects [

127].

Table 3 summarizes some risks and mitigation strategies.

6.2. AI in the IEV/IE2W Industry

6.2.1. General Applications

Lately, AI, blockchain, robotics, Internet of Things (IoT) and Industry 5.0 are gaining traction [

130]. These will significantly influence manufacturing and the emergent IE2W industry will also benefit [

131,

132,

133]. AI can find great application in overall energy management systems and to ensure the sustainability of the IE2W industry as well as of the environment [

89]. Industry 4.0 (and now Industry 5.0 with the sustainability edge) have been analyzed [

134], highlighting its importance for companies wanting to make a change. AI in Industry 5.0 is manifested through digital manufacturing, which can be applied in various industries [

135]. This is often called the 5th industrial revolution (IR5.0) that will revolutionize the manufacturing sector to enable seamless and sustainable synergy between the efforts of man and machine [

136,

137]. Technologies like the blockchain can also be applied in the EV supply chain [

138] in keeping with the CE [

139]. However, it is important to view the benefits of these technologies in light of unique infrastructure (power shortages, charging infrastructure, etc.), economic (high capital costs prevent large-scale adoption of many of these technologies), and social (low awareness, inadequate skill development, etc.) challenges that exist in India.

AI technology can facilitate and accelerate the implementation of CE norms in the IE2W industry [

140] in the fields given below:

Supply chain optimization: AI-powered supply chain solutions enable manufacturers to forecast parts demand, track inventory, and identify risks, thereby empowering smooth procurement and logistics. These could address sustainability bottlenecks in the Indian EV/IE2W industry, creating a more efficient, resilient, and circular value chain [

141].

Table 4 summarizes the optimization in the supply chain that is achievable through AI from a life cycle assessment (LCA) perspective.

Some examples of AI applications in the supply chain of IE2W are given in

Table 5 below.

Other AI applications for IE2W:

Table 6 summarizes the other AI applications that are employed by the IE2W industry to optimize processes for efficiency, cost control, and better productivity.

6.2.2. AI in Regulatory and Policy Framing by the Government

AI can help the government frame policies targeted at sustainability and circularity objectives, as given below:

Data-driven policy formulation: AI enables policymakers to analyze large-scale, real-time data on material flows, resource use, and environmental impacts, leading to greater accuracy in modeling and data-supported decisions for circular policy development through predictive analytics and scenario simulations [

174].

Adaptive and dynamic regulations: AI can create adaptable regulations that can auto-modify fresh inputs or situational changes, which is useful in dynamic domains like materials innovation, waste management, and reverse logistics [

175].

Effective monitoring, compliance, and transparency: Empowers real-time monitoring of supply chains, resource consumption, waste handling, etc., to assure circularity compliance to aid transparency and make policies more effective [

176].

Cross-sectoral collaboration: AI promotes synergy between government, industry, and academia for CE initiatives by identifying and overcoming systemic inefficiencies [

174].

Ethical and social considerations: By simulating long-term outcomes of policy measures and strategies, AI enables the government to actively address societal impacts and to ensure that CE policies are fair, inclusive, and equitable [

126,

177,

178].

Incentivizing circularity in industry: AI-designed policies can accommodate the promotion of economic incentives encouraging investment in circular business models and sustainable technologies [

179].

To summarize, AI assists policy development by offering governments and organizations advanced tools for analysis, implementation, and adaptation, thereby creating a resilient, adaptive, responsive, and technologically superior regulatory environment.

6.2.3. Policies for AI and Circularity: Snapshots from Other Countries

Many other countries have their own policies linking AI and circularity, often integrating digital infrastructure and advanced analytics in their national strategies for sustainability. We look at a few examples:

Successful implementation depends on the government’s capability to ensure effective legal frameworks, targeted incentives, open data policies, and support for digital infrastructure and AI skill development [

183].

6.2.4. AI in Waste Management

AI-powered waste management is often referred to as smart waste management [

184,

185]. Emerging economies have the potential to leapfrog legacy waste management systems by adopting digital CE models, creating cost-effective models, and promoting sustainability [

186]. They often use PPP models, public and donor funding, open-source platforms, and collaborative innovation ecosystems (DMR 2023) to overcome financial hurdles [

187]. Some of the key AI applications for this are given below:

Waste sorting: AI-driven systems considerably improve sorting (plastics, metals, and other materials) accuracy for recyclables and help to reduce contamination and boost recycling rates vis-à-vis manual sorting [

188].

Smart waste collection: AI in conjunction with IoT sensors predicts saturation levels of waste bins and optimizes collection routines, thereby reducing fuel consumption, operating costs, and emissions [

189].

Waste data analytics: AI collates and analyses waste generation data to facilitate planning and decision-making in policy through real-time dashboards with municipal authorities and companies. This also helps to measure performance and identify recycling loopholes [

186].

Consumer engagement: AI-powered mobile apps encourage sustainable behavior by informing citizens about waste segregation, collection timings, and incentivizing recycling participation, thereby boosting CE principles at grassroots levels [

188]. Countries like India and Kenya tackle growing electronic waste [

190] and deploy mobile-first platforms linking households with informal waste collectors for more efficient recycling and reuse [

191].

6.2.5. Limits, Risks, and Trade-Offs for AI in Waste Management

Deployment of AI-driven systems for waste management in emerging economies will have to deal with challenges that limit full utility. There will be risks and trade-offs. The path to a tailored and contextual process using technological innovations, effective regulatory frameworks, and pertinent stakeholder engagement will have to be worked out:

Infrastructure and technical challenges: The inadequacy of extensive IoT networks, sensor technologies, and effective data collection systems prevents AI from functioning optimally in waste management [

192]. Waste data is also sporadic and inaccurate, which impairs prediction in waste patterns and route optimization [

186]. The complexity of integrating AI with legacy systems and informal networks is also an issue [

189].

Financial and resource constraints: AI hardware, software, and implementation are expensive for municipalities or waste companies, necessitating hand-holding from the government or other sources [

188]. Added to this is the skill gap due to a shortage of personnel who are AI-trained and who understand data science while also having exposure to waste management [

191].

Social and institutional barriers: Informal waste management agencies are an inseparable part of waste collection in developing countries, and their integration into AI-driven systems can be a challenge [

186]. Lack of awareness of AI’s benefits in decision-makers and society at large adversely affects investment and adoption [

188]. Insufficient regulatory frameworks for data governance, privacy, and AI ethics pose their own set of challenges [

189].

Environmental and operational risks: Uneven waste generation patterns, in terms of waste types, volumes, and disposal practices across geographies, complicate AI efficiency [

193]. In developing economies, due to financial and institutional constraints, the maintenance and adaptation of AI systems are impacted [

186].

These challenges necessitate tailored, context-sensitive approaches combining technological innovation with capacity building, regulatory strengthening, and inclusive stakeholder engagement to enable effective AI-driven waste management in developing countries [

192].

7. Challenges, Opportunities, and Recommendations

We summarize the challenges, opportunities, and recommendations for applications of AI in the CE and sustainability of the IE2W industry below.

7.1. Challenges

There are certain key challenges that arise when integrating AI into IEV/IE2W CE models. These challenges include technical, organizational, and systemic barriers that restrict the efficiency of AI systems and their positive impact on circularity and sustainability [

194]. These are discussed below:

Data quality and availability: IEV/IE2W supply chains and recycling networks, as yet, do not have access to the accurate, comprehensive, and real-time data required for training AI models. They also lack the desired digital infrastructure and standardization across data sources [

194].

Hunger for resources and negative environmental impact: Large-scale AI models require significant computational power, necessitating high energy consumption and heavy reliance on rare earth metals, thereby negating sustainability gains [

179].

Linear model bias: Many existing AI solutions may suffer biases arising from the legacy training data obtained from linear (take–make–waste) models. This may prejudice circular production, procurement, and supply chain practices unless the AI systems are retrained appropriately [

179].

Interoperability and integration: Data protocols and IT systems across OEMs, recyclers, and suppliers are not standardized and remain fragmented, which at times precludes seamless AI integration for circularity and sustainability of business models [

181,

195].

Ethical, privacy, and security concerns: Privacy, security, and ethical concerns should be addressed through robust governance systems to foster consumer trust [

126].

Skill and knowledge gaps: There is a skill deficit for recycling and CE throughout the battery value chain, from recovery to transportation to testing, recycling, and refurbishment. There is also low consumer awareness of battery environmental and safety risks. There is a shortage of professionals with cross-disciplinary knowledge in AI, CE principles, and EV technology, precluding the holistic organizational exploitation of AI and implementation of AI-driven circular solutions [

196].

Financial and regulatory barriers: Prohibitive capital costs for recycling plants (between Rs 220 and 370 cr) add to the lower penetration and willingness to invest. A total of 18% GST on retired batteries disincentivizes recycling. Further, there are logistical and data gaps. High capital outlay for AI infrastructure and systems causes problems for smaller firms, which are quite prevalent in the IE2W industry [

196].

Complexity of the EV value chain: The complexities involved in IEV/IE2W parts and multiple vendors imply the need for the utmost coordination, efficient reverse logistics, and comprehensive adoption of circular practices by OEMs and all other stakeholders in the value chain [

197]. These challenges highlight the need for orienting AI towards circularity, robust cross-sector collaboration, and supportive governmental frameworks to accrue the maximum benefits of AI within the IEV/IE2W CE models [

194].

7.2. Opportunities

Despite challenges, India has significant opportunities to establish a thriving CE for EV batteries, as given below:

Reducing imports of LIBs (now at 100%);

Recycling to reduce imports of rare earths and minerals to boost geopolitical resilience (recent discovery of Li reserves in India further offers long-term promise for domestic supply) [

198];

Battery recycling (market estimated at USD 95 billion annually by 2040) to recover 50–95% [

199] and to boost profitability, economic viability, and job creation (total LIB recycling market in India by 2030 is estimated at USD 11 billion);

Addressing environmental concerns and lowering carbon emissions by up to 90%;

Repurposing EoLEVB into stationary energy storage (ESS) systems [

52,

200];

Exploiting AI and other technological advances and green innovation;

Collaborative efforts on CE between lawmakers, automakers, vendors, battery manufacturers, recyclers, and academia.

7.3. Recommendations

Recommendations emerging from the study are summarized in

Table 7 below.

8. Gaps in the Literature

Going forward, it is clear that AI is not a solitary panacea but a strategic enabler to facilitate India’s EV sustainability and CE goals. ROL on the subject brings out that most research has been carried out in China, SE Asian countries, and some Middle Eastern/African countries. Few studies exist in India, and even these are limited to the manufacturing sector, in general, or to the automobile industry, and not particularly either the IEV or the IE2W industry.

Areas not covered by the literature, as seen during the review, are summarized in

Table 8 below, which also implies the areas for future research.

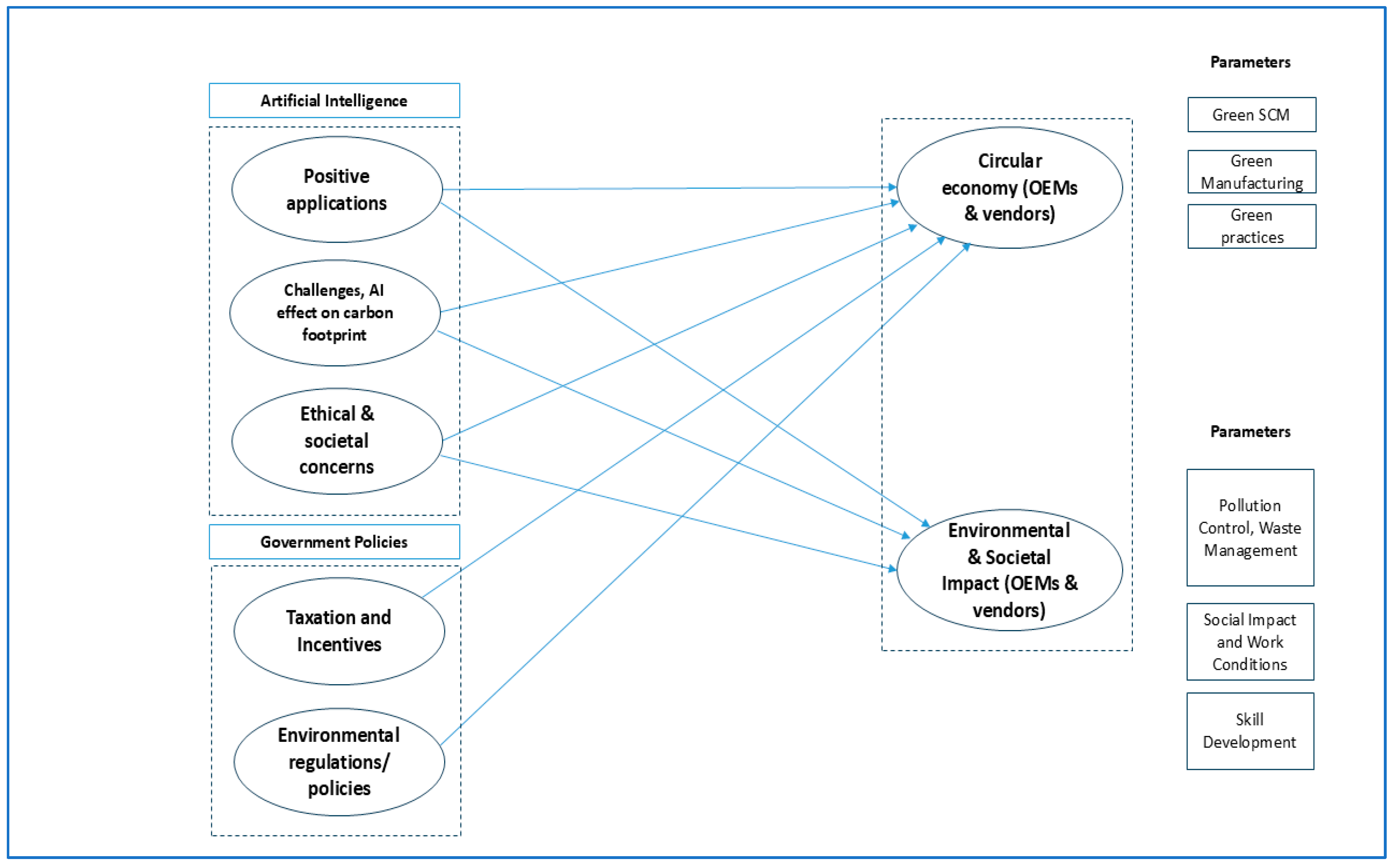

9. A Conceptual Framework

Through the identification of gaps, one can arrive at a tentative conceptual framework, as given in

Figure 5. The framework considers AI and government policies as being the two independent variables with a total of five constructs between them that are connected to the two dependent variables of the CE and environmental and societal impact. Furthermore, these dependent variables have parameters under them, which would be influenced by AI and government policies, respectively. It bears relevance that for both CE on one hand, and environmental and societal impact on the other, it would play differently for OEMs, who are the manufacturers of the IE2Ws, and the vendors, who supply parts and components to facilitate the manufacturing for the OEMs. Our understanding of environmental and sustainability issues would be incomplete without also factoring in societal aspects. The framework draws (but is distinct) from various models for SSCM (natural resource based view or N-RBV [

209], stakeholder and legitimacy theory [

210], institutional theory [

211]), Industry 5.0 (human centricity and resilience models [

212], sustainability model [

213]), and CE (10R Model [

214], C2C Model [

215]).

10. Scope for Research and Potential

10.1. Limitations of Study

Limitations for this review include a lack of adequate material, including empirical data in the Indian context with reference to the applicability of AI in the CE and sustainability of the EV industry, and virtually none at all for the IE2W industry. Some dynamics of the automobile industry in India, which has been taken as a reference point, may or may not work well for the IEV/IE2W industry. While the application of AI is often spoken about and touted, the on-ground utilization of AI-driven technology, processes, and systems may not be very widespread or mainstream, which leaves unanswered questions. Further, the country has been relatively slow off the block on AI, with most LLMs and models being of Western origin. Government regulations are the same, and policies are a work-in-progress with an unsatisfactory implementation record. With the dynamic nature of the constantly evolving IE2W industry, it may be difficult to accurately predict the scope of AI applicability in the near (5 years) and mid-term (10 years) future. Hence, present-day indicators have been relied on for projections. Considering the competitive nature of the IE2W industry, information, other than what is available on the open domain, is hard to come by (except for OEMs, which have gone public). Details of vendors are also hazy, with no definitive directory giving their credentials, and with open domain information varying greatly.

10.2. Discussions

10.2.1. Theoretical

Theoretical and managerial discussion points in a research article on the role of AI in the CE and sustainability of the EV industry should logically focus on both conceptual frameworks and actionable strategies for industry leaders [

216]. A few theoretical discussion points are brought out below to underscore the role of AI in the CE of the IEV/IE2W industry:

AI enables the CE: AI facilitates product design, which empowers circularity, ensures resource optimization, and facilitates decision-making using predictive analytics and tools [

217].

Sustainability in manufacturing: Deployment of AI in EV/E2W manufacturing cuts waste, reduces carbon footprints, and advances the life of products through predictive maintenance, efficient use of energy, and a streamlined supply chain [

218].

Frameworks across disciplines: When a conceptual model is devised, which combines green and sustainable manufacturing, digitalization, and circular supply chains, it demonstrates the synergy between business, technology, policy, and societal factors, which further boost the transition towards sustainability

Data-driven innovation: AI encompasses data collation, real-time monitoring, and simulation of environmental as well as economic impact to ensure a dynamically improving circularity for the business model [

219].

10.2.2. Managerial Practices

Taking the theoretical aspects forward, we have outlined steps that can be taken by managers to adopt ‘leagile’ practices [

220], supplier selection [

221,

222], and AI in manufacturing [

223]. Indian IEV/IE2W managers should adapt global best practices to the domestic supply chain [

61,

224], incorporating AI. Our work highlights the significance of AI in promoting the CE and sustainability in the IE2W industry. Certain other relevant issues for managers on this topic are given below:

Acting upon circular strategies: This can be performed by managers by leveraging AI tools to ensure circularity in the supply chain through the planned recovery, reallocation, refurbishment, sale, and disassembly of EV components in a smooth manner [

225].

Resource optimization and waste reduction: AI-driven solutions can be used to optimize material flow, facilitate sorting through visual recognition, and ensure effective energy management towards sustainability in resource use [

226].

Supply chain collaboration and transparency: AI facilitates real-time data sharing, stakeholders’ collaboration, and adaptive decision-making across multiple circular levels, including recycling agencies, logisticians, repair and maintenance services, and the OEMs [

139].

Strategic sustainability initiatives: Managers can employ AI analytics to simulate situations, forecast market developments, predict demand, and adapt circularity in their business models to enhance profitability and competitiveness while simultaneously meeting the obligations of government regulations and environmental norms [

227].

Ethical considerations: Effective managers should not ignore the sensitivity of data security, interoperability, skill gaps, and ethical design [

218].

The above covers both the conceptual analysis and an actionable roadmap for managers to benefit from AI to drive circularity and sustainability in the IE2W context [

216].

11. Summary

India is experiencing an EV revolution, of which E2W is a major component. The enormous future potential of the IE2W industry makes it an ideal candidate for study.

The main contributions of the study include highlighting the extent to which AI can be used to enhance CE and sustainability in the IE2W industry, while also taking into account the pitfalls of AI as well as its own environmental footprint. The study has revealed myriad use-cases for AI in all aspects of the IE2W industry, including vendor management, the supply chain, logistics, transportation, manufacturing, waste management, marketing, servicing, consumer engagement, and EoL management for batteries. All of these contribute to the CE and sustainability of the sector as a whole.

The government has an important role with regard to fixing policy and the regulatory frameworks. The study finds that policies and regulations in themselves will not be adequate without an effective methodology in place for their implementation and enforcement.

Gaps that have emerged in the reviewed literature have emphasized the areas that researchers can address exclusively in the IEV/IE2W sector. These include the following: (a) subject-particular issues like specific application of AI to CE, GSCM, and effects of AI on environmental aspects, including waste management and pollution control; (b) policy impact, impact of AI on job creation in this sector, and impact of R&D; (c) and, all technological aspects with regard to the deployment of AI in the IEV/IE2W sector that set it apart from other industries, including the automobile industry. Being an industry that is still young in India, there is ample scope for deeper exploration of many aspects based on empirical studies.