1. Introduction

With a global shift towards decarbonisation and energy sustainability, the transport sector is fast becoming a focus area for reducing greenhouse gas emissions. Electric vehicles (EVs) are increasingly promoted as a green alternative to conventional internal combustion engine (ICE)-based vehicles. However, the environmental benefits of EVs are not as straightforward as they appear; the electricity used for charging often originates from carbon-intensive grids [

1], resulting in a dissociation between perceived sustainability and actual upstream emissions. This indirect dependency on fossil fuel highlights the importance of evaluating sources of emissions when determining the sustainability of EVs. Further still, there is potential for increased fossil fuel demand as the popularity of electric vehicles grows [

2].

By harvesting solar energy directly from the surface of the vehicle, VIPV can supplement grid charging [

3]. This reduces the vehicle’s carbon footprint while simultaneously improving energy autonomy. In addition, to extend range and support auxiliary loads, VIPV may be particularly advantageous in high irradiance regions such as Australia [

4].

Overall, VIPV presents a promising opportunity to advance sustainable transportation further. Thus far, its integration into modern vehicles has been lacking due to several challenges facing vehicle manufacturers, with the key factors being different environmental conditions heavily impacting energy yield, initial development costs for integrating cells into the vehicle’s body and design trade-offs between maximising solar exposure and minimising weight, aerodynamics and aesthetics. Integration of photovoltaic cells onto curved and contoured vehicle surfaces further complicates installation, as non-planar geometry, orientation changes and partial shading across panels can significantly reduce conversion efficiency and add complexity to the system design. There is also a lack of standardised methodologies and performance metrics in the dynamic nature of vehicle movement, usage and location. Variable load demands and realistic solar tracking on a vehicle with dynamic orientation also require further understanding.

For vehicle manufacturers, it is essential to maximise the system performance without compromising economic viability, as solutions with poor return on investment will not achieve widespread adoption. To enable sustainable transport, vehicle-integrated technology must be cost-effective, scalable and accessible to the broader public market, as opposed to being a premium extra. Regardless of technological innovation and achievement, customer opinion and perception are by far the biggest hurdle when bringing a new product to market [

5].

This paper contributes to the ongoing sustainability effort by presenting a practical, simulation-based analysis of a VIPV system integrated with a light passenger vehicle. The model evaluates energy yield under seasonal environmental conditions and varying vehicle orientation, explores system-level energy flow and incorporates intelligent energy management via fuzzy logic control. The aim is to assess real-world feasibility and performance of VIPV under typical Australian driving conditions.

To give an overview of existing research into VIPV systems, and to provide comparable results for this study,

Table 1 gives a brief analysis of the existing literature.

In terms of solar energy integration, MPPT is the industry-preferred technique for optimising power extraction from photovoltaic systems, boasting up to 33% efficiency gains over pulse width modulation (PWM) in cloudy conditions. References [

12,

13] discuss some of the most commonly available methods, of which perturb and observe remains the most widely adopted due to its simplicity, minimal sensing requirements and low computational overhead. This makes it particularly attractive for VIPV applications. Despite these advantages, P&O is prone to small oscillations around the maximum power point (MPP) and can mis-track when exposed to rapid changes in irradiation, such as when clouds pass overhead. In this study, each solar module is controlled independently using P&O, allowing the roof and bonnet panels to operate at their optimal power points despite differences in size, orientation and shading. This per-panel approach is yet to be demonstrated in VIPV systems.

Hence, while advanced MPPT methods are well documented, P&O continues to represent the best balance of accessibility, reliability and cost-effectiveness for real-world VIPV application. Importantly, system level strategies such as fuzzy logic energy management can be layered on top of P&O to mitigate its weaknesses without undermining its low-cost advantage.

In practice, MPPT is often implemented using DC-DC converters, such as buck, boost and the combination, buck–boost topologies. For VIPV, the buck converter is most suitable, as photovoltaic (PV) array voltages often exceed those of the vehicle auxiliary battery, making step-down conversion an efficient and effective choice.

While fuzzy logic, MPPT techniques and dual buck converters have already been studied independently, their combined application to a cost-effective VIPV system under a realistic Australian temperature and irradiance conditions has not yet been thoroughly investigated. Recent studies [

14,

15] demonstrate the potential of VIPV technology through advanced components and sophisticated design; however, reliance on prototype-level technology or exclusion of key design factors limits the real-world applicability of such studies. This study addresses that gap by developing a simulation-based model that evaluates system-level energy flow, explores performance under dynamic conditions and assesses real-world feasibility for the mass production of vehicle-integrated photovoltaics.

To provide a clear outline of realistically achievable VIPV performance, the following research questions are addressed:

What is the technical and practical performance of a VIPV system under realistic driving and environmental conditions?

How effectively can fuzzy logic energy management and dual MPPT buck converters optimise energy capture and storage efficiency?

To what extent can the proposed VIPV configuration reduce grid energy use and CO2 emissions compared to existing implementations?

2. System Design

This study employs a simulation-based methodology to optimise a vehicle-integrated photovoltaic (VIPV) system, focusing on charging the vehicle’s auxiliary battery. The approach includes a review of current solar energy technologies and techniques, with an emphasis on low-cost and low-complexity implementations to assess the practical viability of VIPV systems in Australia using today’s technology.

Given the relatively low voltage output of photovoltaic systems, charging the auxiliary battery is preferred over the main traction battery, to minimise switching losses and simplify system integration. MATLAB/Simulink 2025b is used for simulation and modelling throughout the study, enabling detailed analysis and performance prediction.

Key stages of design include:

Converter Design: Tailored for efficient energy transfer from the solar array to the auxiliary battery.

Irradiance Simulation: modelling solar exposure under typical Australian conditions.

Fuzzy Logic Charging Control: Implementing intelligent control strategies to optimise battery charging.

Performance Evaluation: Assessing the system efficiency, reliability and potential energy yield.

This optimised scenario aims to provide insights into the capabilities and limitations of VIPV systems in the Australian context, contributing to the broader understanding of sustainable vehicle energy solutions.

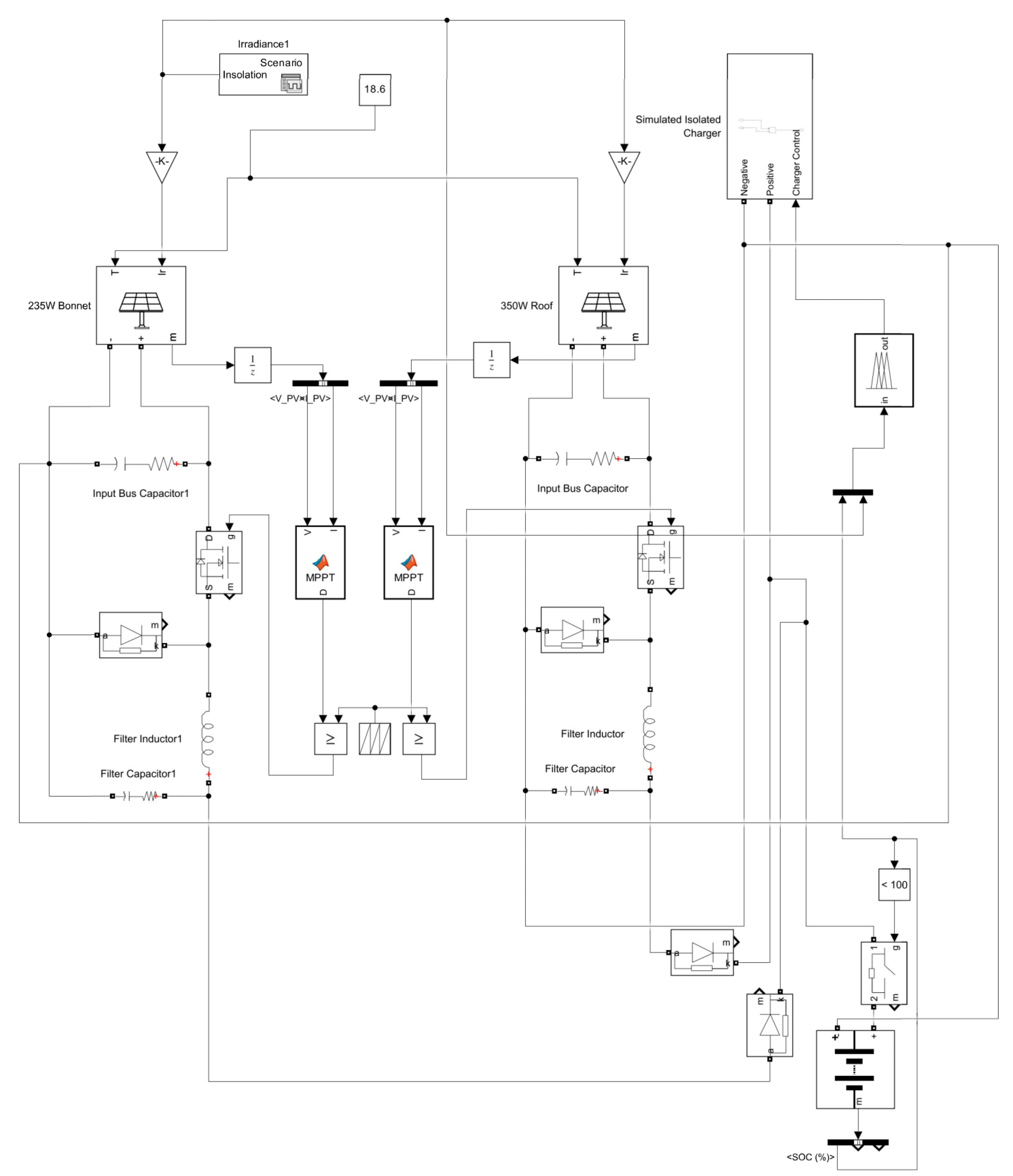

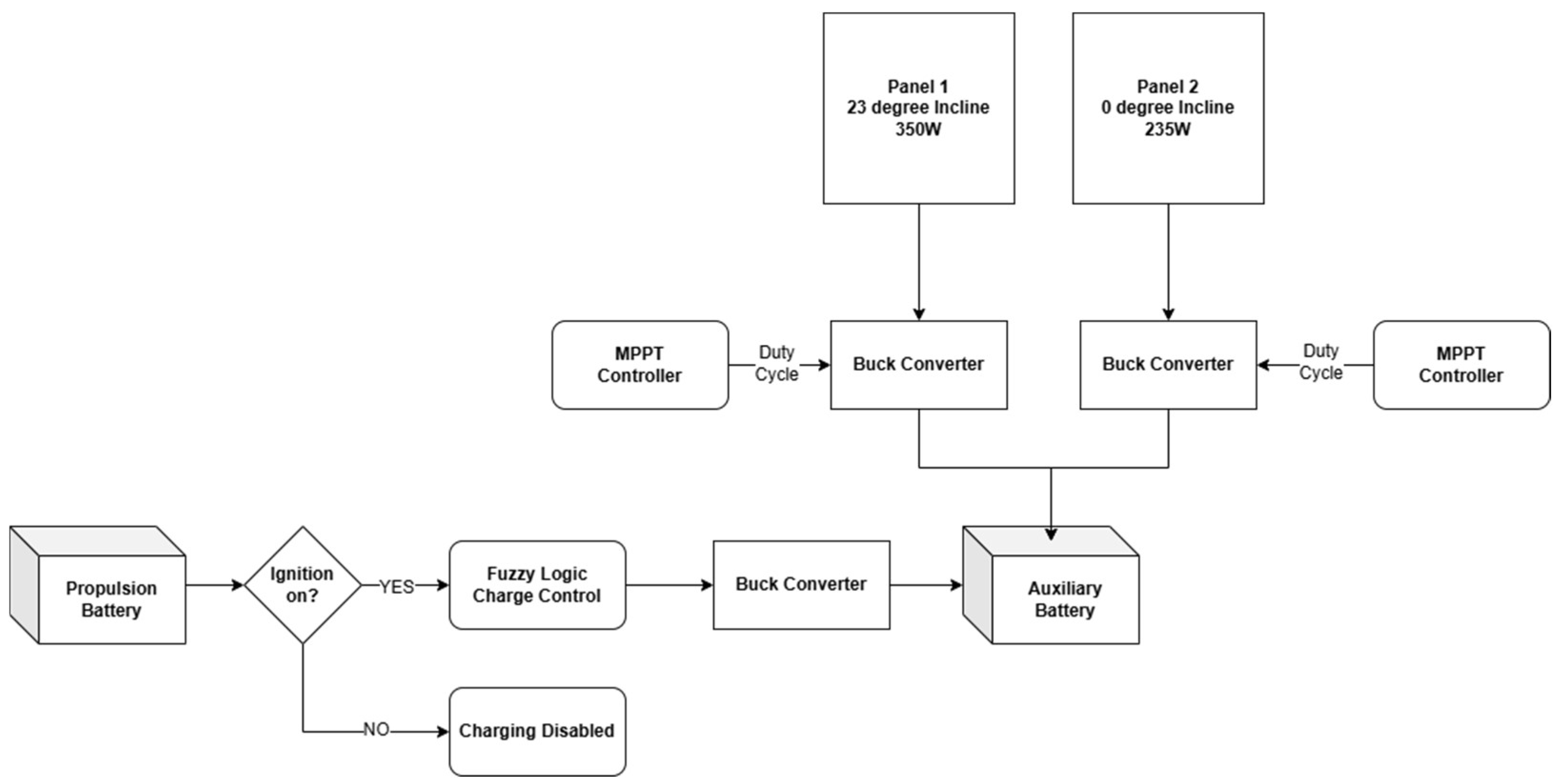

Figure 1 shows how fuzzy logic and MPPT control are integrated with DC-DC buck converters to optimise system performance.

The VIPV system is designed around a light passenger vehicle, with dimensions based on a Tesla Model 3. Major system components include a fixed rooftop/bonnet photovoltaic array, dual MPPT, dual DC-DC buck converters and a traction battery–auxiliary battery fuzzy logic charging controller.

Baseline values of solar insolation and average temperatures for the Melbourne metropolitan area were sourced from [

16,

17,

18], utilising the most conservative data to avoid overestimating performance. These sources are used to simulate real-world conditions and seasonal cycles for the local climate, as close as is practicable. The simulation uses a daily time scope to collect expected data for a month-by-month basis. On-vehicle zenith angle remains constant to reflect typical vehicle mounting and production is averaged across four different vehicle azimuths: 0°, 90°, 180° and 270°.

Within MATLAB/Simulink, two separate solar arrays are used to simulate the PV panels mounted on the roof and bonnet of the vehicle, each configured to represent a single panel. The simulation time step was set to 1 × 10

−6 s, providing high resolution to capture rapid variations in PV output and converter performance. Based on the approximate available surface area of a Tesla Model 3, panel dimensions of 1 m

2 (bonnet) and 1.5 m

2 (roof) are considered feasible for integration into the vehicle body. High-efficiency (23.4%) copper indium gallium di-selenide (CIGS) solar cells [

19], with their small cell size, are suitable for this application; these modules would have nominal power ratings of approximately 235 W and 350 W, at elevation angles of 12° and 0°, respectively. Module angle within the model is accounted for by applying appropriate gain (±) to the 240 W panel, according to vehicle azimuth.

Roof and bonnet curvature also play an important role in optimal power output. Based on a maximum estimated sagitta (height) of 50 mm for the roofline, Formula (1) gives an estimation of curvature.

where

R is the radius of curvature,

h is the sagitta and

L is the length of the chord subtending the arc. A curvature radius of 3.78 m and 2.53 m is estimated, longitudinal and transverse for the roof. The bonnet is assumed to be almost flat and is only affected by elevation angle and azimuth. Formula (2) gives the angle required to calculate curvature performance degradation.

θ is the angle subtended by the arc of the roofline. This results in an angle of

across the transverse axis and

along the longitudinal axis. Based on results in [

20], these curvatures are estimated to cause up to 19% performance loss for the roof panel, and 11.37% systemwide, due to suboptimal incident angles.

Figure 2 illustrates how solar modules can be integrated into the vehicle body using protective glass or polymer coatings, allowing them to be incorporated seamlessly into the existing design and aesthetics. Flexible solar panels, operating at extra-low voltage and appropriately fused, are unlikely to present elevated safety risks or significantly affect vehicle weight distribution during a collision or aggressive cornering. Nevertheless, any substantial vehicle modification must comply with rigorous safety and crash-testing standards.

To minimise system losses resulting from differences in module size and elevation angle, the DC-DC converter design incorporates two parallel buck converters, each with its own MPPT controller. This allows each panel to operate independently at its optimal power point, under varying irradiance and orientation. This design prioritises high efficiency by optimising inductor and capacitor sizing, minimising switching and conduction losses and allowing each PV module to extract maximum power independently. Converter switching parameters are also optimised to reduce electromagnetic interference (EMI), ensuring minimal impact on vehicle electronics and communication systems. In addition, a fuzzy logic controller manages energy flow from the traction to the auxiliary battery, dynamically adjusting the DC-DC charger output based on the battery’s state of charge and solar availability. Unlike traditional controllers that follow fixed settings or rigid ‘if-then’ rules, the fuzzy logic controller adapts smoothly and intelligently to multivariable inputs, improving auxiliary battery charging efficiency and maintaining battery health. The combination of dual MPPT converters with fuzzy logic energy management is novel in the context of a light passenger VIPV system, providing coordinated control that has not been demonstrated in the prior literature. As the cell count for the roof and bonnet PV modules differs significantly, a unique buck converter is designed to complement each solar panel. The equations in

Table 2 calculate the specific component ratings, where

is the intended output voltage for the lithium battery chemistry,

is the minimum expected input voltage from the solar panel,

is its rated power and

is the switching frequency of the PWM signal.

The selection of input variables for the fuzzy logic controller was guided by their direct influence on auxiliary battery charging requirements. The battery state of charge is critical to ensure the battery is neither overcharged nor excessively depleted, while solar irradiance reflects the available energy from the VIPV system. These inputs were classified into low, medium and high categories to capture the practical operating ranges observed in Australian driving conditions and PV output variability. The output variable, charger amperage, was chosen to provide fine-grained control over energy transfer from the traction battery to the auxiliary battery, maintaining battery health and maximising solar utilisation. The fuzzy rule base was constructed to prioritise charging when the SOC is low and/or solar availability is high, while reducing or halting charging when the battery is near full or solar input is insufficient. This approach balances energy efficiency, battery longevity and responsiveness to changing environmental conditions, ensuring adaptive and robust system performance under dynamic real-world scenarios.

Table 3 displays the calculated ratings for buck converter components. The value for the 350 W panel input capacitor was 112.6 μF; however, it was discovered that the output was not reaching its maximum power point unless this capacitor was increased in size to 900 μF.

For the MPPT controller, the perturb and observe logic has been selected for this application due to its reliability, minimal requirements and ease of implementation.

Figure 3 gives an overview of MPPT logic.

While P&O is widely used due to its simplicity and reliability, this study applies it independently to the roof and bonnet PV modules through dedicated buck converters and MPPT controllers. This per-panel approach allows each module to operate at its optimal power point under differing panel sizes, orientations and shading conditions, maximising energy extraction. This configuration has not been previously demonstrated in light-passenger vehicle VIPV.

In a single execution cycle of the programme, the algorithm reads the current power output and compares it to the voltage and power of the previous cycle. Using this information, a nested if-else decision process implements the following P&O logic.

also, and , the duty cycle is decreased by

or else, if , the duty cycle is increased by .

also, , the duty cycle is decreased by

or else, if , the duty cycle is increased by .

To maximise the utilisation of solar energy, a fuzzy logic controller, based on the Mamdani inference system, controls a DC-DC charger from the main traction battery. This is designed to only charge the auxiliary battery when solar is unavailable or the battery is deeply discharged. The DC-DC charger supports bidirectional energy flow, enabling power to be drawn from the traction battery to supplement the auxiliary battery when solar generation is insufficient, while minimising losses through intelligent load management. The controller takes fuzzy variables for the battery’s state of charge and solar irradiance, compares them to a rule set and varies the output of the DC battery charger accordingly.

Figure 4 shows the level of membership for each fuzzy variable;

Table 4 and

Table 5 show the cut-off parameters for each fuzzy variable and the ruleset that guides the output of the controller.

Lithium-ion chemistry has been selected for the battery in this model, since lithium batteries are lighter and more energy-dense than traditional lead-acid batteries. In addition, lithium is tolerable of deeper discharge and greater current drawing, making it a suitable candidate for a PV auxiliary system where lengthy durations in a discharged state are possible and likely.

In all, 48 simulations were performed based on the average monthly data for the city of Melbourne. Solar irradiance and average temperature were applied; panel elevation angle and azimuth were accounted for and 12.8% of the total system performance was subtracted due to a curved roof panel and the efficiency of the DC-DC converters. The simulation was executed with a time step of 1 × 10

−6 s, ensuring accurate resolution of power fluctuations and MPPT controller dynamics. Converter efficiency is calculated by Equation (9), where η is efficiency as a percentage.

3. Results

Table 6 illustrates the average daily energy production in watts for the proposed solar integration. Based on typical monthly temperatures and insolation levels for Melbourne, Australia, the results show evidence of seasonal trends. Green indicates above-average power, occurring for nearly half the year; orange indicates average production, generally from late autumn to mid-spring; red indicates the lowest yields, typically mid-winter, where energy harvesting declines drastically due to sub-optimal insulation and incident angles. This seasonal variation confirms that VIPV performance is strongly influenced by both solar availability and vehicle orientation, highlighting the importance of adaptive control strategies. The optimum yield captured 29% yearly insolation, while average maximum temperatures remained below the standard test conditions (STCs) at 21 °C. The variation between maximum and minimum energy capture indicates high sensitivity to environmental conditions, further reinforcing the need for per-panel MPPT control. Combined solar harvest for the full year provides an annual energy contribution of approximately 930 kWh, with an estimated shading factor of up to 50%; as stated earlier, due to covered parking and incidental or building shading, that number could be as low as 465 kWh.

These results show that the dual MPPT approach for roof and bonnet panels effectively maximises energy capture across seasonal and orientation-related variations. Without per-panel control, performance differences due to module size, shading and incident angle could result in significant energy losses.

Under the standard test conditions of at , the roof (350 W) solar panel reaches the maximum power point of 348.2 W at 25 °C, excluding curvature losses, with the MPPT controller and buck converter achieving 328.87 W, or efficiency. The bonnet module achieved a maximum power point of 234.5 W, with the MPPT controller and buck converter producing , or efficiency.

Comparison with datasheet specifications validated the simulation model. When compared with the roof panel rated MPP of 359.8 W, a deviation of 0.46%, when comparing the bonnet panel against a rated 234.9 W, a 0.2% deviation. These results demonstrate that the simulation reasonably represents real-world PV behaviour, accounting for orientation, temperature and converter losses.

Several scenarios were simulated to assess the response of the fuzzy logic-controlled battery charger under varying irradiance and battery state-of-charge conditions.

Figure 5 illustrates the system’s behaviour during a deep discharge event. Early in the day, when the solar irradiance is low and the battery is heavily discharged, the charger delivers the full 40 A of current. As the irradiance increases, the fuzzy logic controller reduces the charge output, prioritising solar energy utilisation. This demonstrates that fuzzy logic control can intelligently balance energy flow and maintain battery health while maximising the renewable energy contribution. Later in the day, as solar input declines and the battery has partially recovered, the charger re-engages at a moderate level to continue battery recovery. Fuzzy logic control ensures the ability to adjust in real time and avoids under- or overcharging the auxiliary battery: a key consideration for practical VIPV implementation. The MATLAB/Simulink model illustrating MPPT buck converters, fuzzy logic-based charging control, along with the core MPPT code can be found in

Appendix A.

Simulations indicate that, under optimal solar conditions, the VIPV integration can provide up to 6838 km of additional range per annum (+15% daily average) for a Tesla Model 3 [

22], while less efficient vehicles, such as the Lotus Emeya [

22], could gain approximately 4366 km (+11% daily average). Based on current electricity rates of

$0.25/kWh, these savings translate to roughly

$232 of annual savings per vehicle.

To evaluate system behaviour under dynamic conditions, an oscillating battery state of charge was simulated to represent multiple charge and discharge events throughout the day.

Figure 6 illustrates the charger’s intelligent response to these rapid fluctuations under varying irradiance. In the early morning, steep reductions in the state of charge trigger a strong response from the charger to maintain operational readiness. Around midday, the fuzzy logic controller adjusts output more conservatively, ensuring that the charger supports the battery without competing with the increasing solar contribution. Again, this prevents unnecessary grid draw and prioritises solar utilisation. By late afternoon, as irradiance decreases, the controller shifts emphasis back to the charger, which resumes primary responsibility for maintaining battery stability. This adaptive control approach ensures optimised energy flow, maximises solar usage and enhances the overall system efficiency under realistic operating conditions. These results confirm the system’s resilience to fluctuating energy demands. Adaptive control ensures optimal energy flow and battery stability.

Considering that approximately 60% of Australia’s electricity is sourced from carbon intensive sources [

23], the VIPV system contributes a measurable reduction in grid-sourced emissions, demonstrating a tangible environmental benefit. Performance depends on factors such as outdoor parking and long-term PV module durability. Physical degradation or mid-life repairs will reduce the energy capture and return on investment.

Figure 7 illustrates the transient response of the P&O MPPT algorithm when subjected to a step change in irradiance. The controller rapidly converges to the maximum power point, with oscillations significantly damped within approximately 0.15 s and full stabilisation achieved by 0.5 s. Relative to the results reported in [

24], the proposed controller demonstrates markedly superior dynamic performance, far outperforming the 25 s convergence of P&O and 2.5 s for fuzzy logic control. This demonstrates the algorithm’s ability to track the optimal operating point in an efficient time frame. The result confirms that the implemented MPPT strategy effectively extracts maximum power with minimal delay, a key requirement for VIPV systems where irradiance can fluctuate rapidly due to vehicle motion and environmental variability.

Rapid convergence and minimal oscillation confirm the dual MPPT approach is effective for VIPV, quickly adapting to changes in solar input due to shading or vehicle motion.

Table 7 summarises the performance of the proposed VIPV system in comparison with the published literature, highlighting improvements in energy contribution, efficiency and renewable source utilisation.

The proposed system is compared against a leading VIPV vehicle, a prototype and a recent performance study. The Lightyear One, a limited-production

$265,000 USD vehicle [

23], demonstrates the potential of VIPV with 1100 W of PV modules across a 5 m

2 surface area, an example of premium design without cost constraints.

The Toyota Prius (prototype demonstration vehicle) [

15] features 860 W of solar panels, 2.8 m

2 of PV modules and high-efficiency solar cells. This vehicle has a 180 W production variant, starting at

$33,000 USD [

29].

The recent study [

14] illustrates comparable irradiation conditions in the northern hemisphere at an average of 3.8 kWh/m

2 per year and utilising high efficiency (30%), triple junction InGaP/GaAs/InGaAs cells. Notably, the author of the study included a more complex dual active bridge DC converter. Unfortunately, converter efficiency, although tested, is not specifically stated.

The proposed system delivers 930 kWh annually, exceeding the Lightyear One yet falling short of the Prius; this demonstrates that the system achieves competitive solar integration despite using commercially available high-efficiency cells, rather than prototype-level PV technology. When compared to the study in Maryland, USA, the proposed system performs competitively despite the use of more economical solar cells and converters. Solar-assisted range is presented as an illustrative example based on vehicle mileage efficiency, with the proposed system falling between the Lightyear One and the Prius.

The MPPT/buck converter achieved efficiencies of 94.18% (roof) and 95.1% (bonnet) at the upper end of typical practical ranges (70–95%) for DC–DC converters. Small variations are expected due to operating point, temperature and measurement uncertainty. Physical components may exhibit a slightly lower efficiency than the simulation results.

The system provides estimated electricity savings of ~$232/year at $0.25/kWh, exceeding the ~$209/year reported for the Prius, and delivers an estimated carbon offset of 585.9 kg CO2/year, slightly below the Prius’ 526 kg CO2/year. These figures show meaningful reductions in grid electricity consumption and greenhouse gas emissions.

With a peak power density of 360 W/m2, the proposed system highlights strong energy harvesting potential per unit area, outperforming both the Prius (220 W/m2) and the Lightyear One (307 W/m2). The system uses panels with 23.4% efficiency, which is lower than the Prius’ 34%, yet still high for commercially available solar cells. Notably, the high-efficiency cells used in the Toyota prototype are not commercially available.

4. Conclusions

This study illustrates the feasibility and practical performance of a vehicle-integrated photovoltaic system for light passenger vehicles under realistic Australian conditions. The proposed system, comprising roof- and bonnet-mounted PV modules, dual MPPT-controlled DC-DC buck converters and a fuzzy logic-managed auxiliary battery charging system, achieved an annual energy contribution of 930 kWh, translating to a significant solar assisted range, energy cost savings and carbon reduction. The per-panel MPPT approach and fuzzy logic energy management were shown to maximise energy capture and adapt intelligently to rapid changes in irradiance and battery state of charge, highlighting the benefits of intelligent control in unpredictable conditions.

Comparative analysis indicates that the system is competitive with leading VIPV implementations. While cell efficiency could be vastly improved in years to come, as demonstrated by the Toyota Prius, the system’s peak power density of 360 W/m2 surpasses both the Toyota and Lightyear examples, demonstrating efficient energy management and use of the available surface area. MPPT/buck converter efficiency is in the high range, and the system delivers measurable reductions in grid energy use, amounting to approximately $232 per year. Greenhouse gas emissions also see a considerable reduction, at 585.9 kg of CO2 per year. These results show that cost-effective, commercially available VIPV systems can meaningfully supplement vehicle energy demands, improve energy autonomy and contribute to decarbonisation without relying on premium prototype level components.

Overall, this work provides evidence that VIPV integration with intelligent energy management is both technically feasible and practically beneficial. The study establishes a foundation for further development in the areas of PV placement, improved cell efficiency and adaptive control strategies, supporting the broader adoption of sustainable vehicle technologies.