Application of Psychoacoustic Metrics in the Noise Assessment of Geared Drives

Abstract

1. Introduction

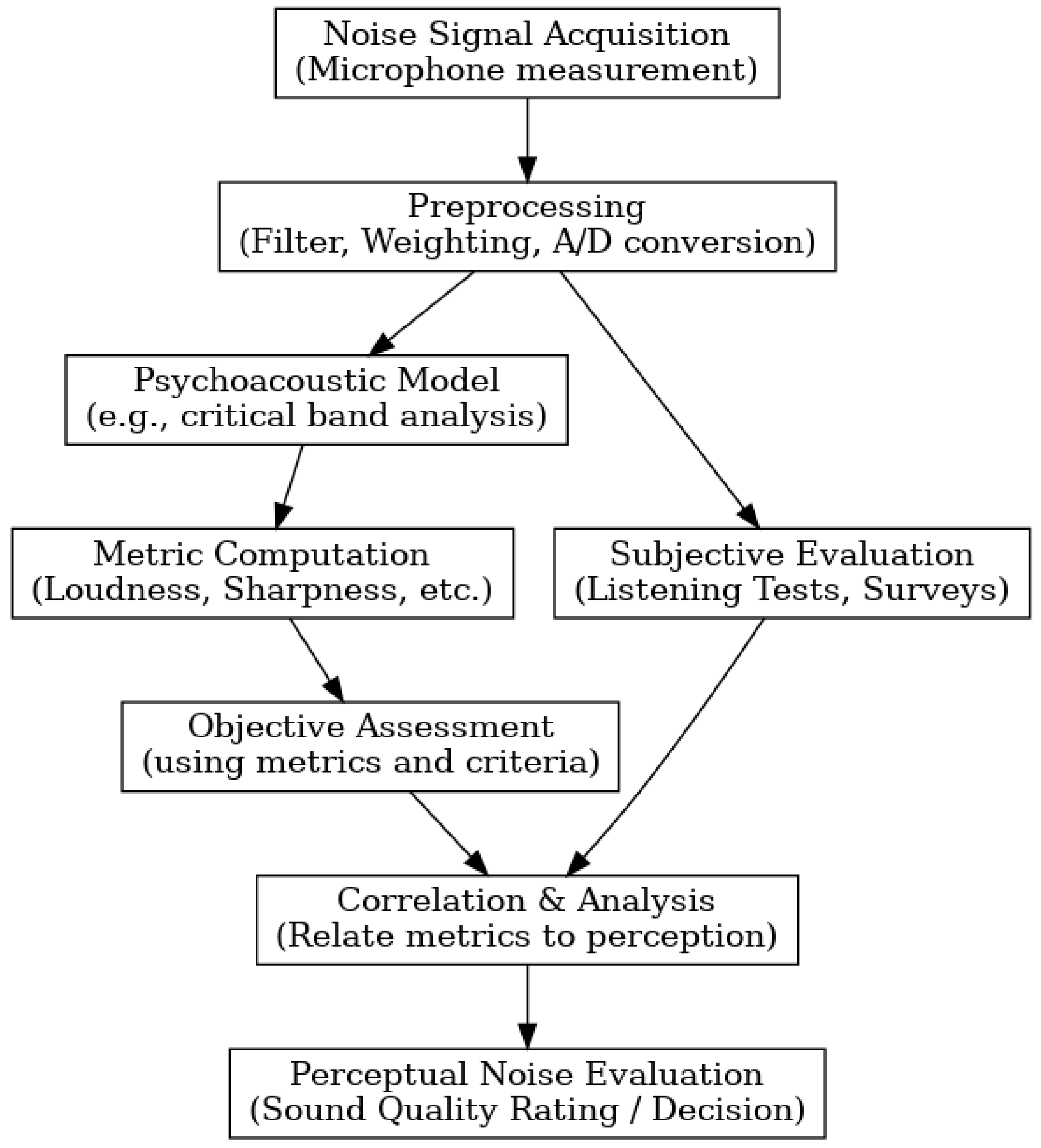

2. Materials and Methods

3. Background: Traditional vs. Psychoacoustic Noise Evaluation

3.1. Traditional Gear Noise Evaluation Methods

3.2. Psychoacoustic Noise Evaluation Approaches

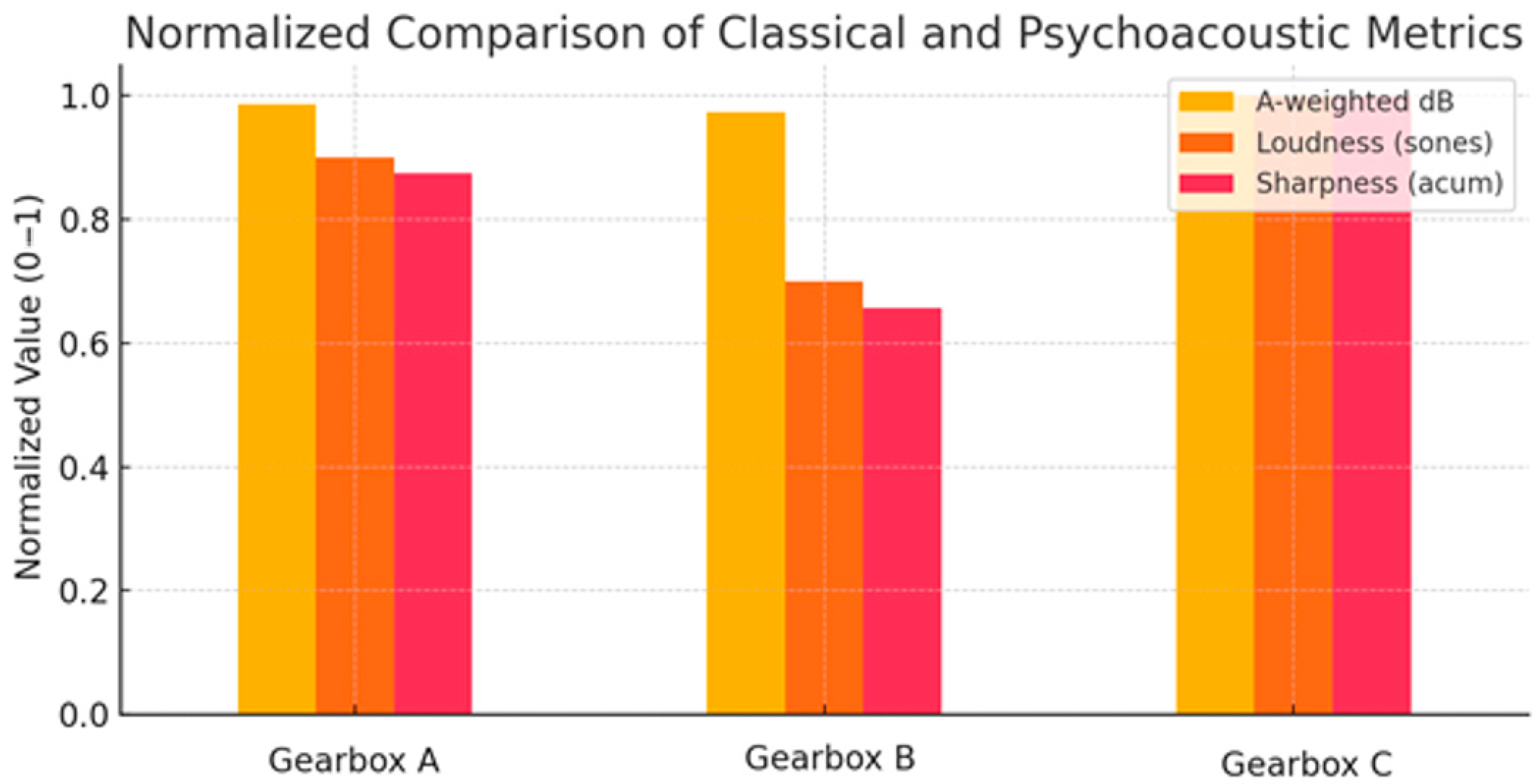

- Overall Level vs. Loudness: Traditional: dB(A) level; Psychoacoustic: loudness in sones accounts for frequency weighting and masking as per human hearing [1].

- Frequency Spectrum vs. Sharpness/Tonality: Traditional: identify spectral peaks; Psychoacoustic: quantify how tonal a sound is or how high-frequency-weighted it is (sharpness), which better predicts harshness.

- Time Waveform vs. Roughness/Fluctuation: Traditional: time-domain metrics like kurtosis; Psychoacoustic: quantify modulation effects that cause rough or throbbing sensations.

- TE vs. Sound Quality Index: Traditional: minimize mechanical error; Psychoacoustic: measure resultant sound’s annoyance (which may involve multiple factors beyond just error magnitude).

4. Psychoacoustic Metrics and Models

4.1. Loudness

- Frequency Analysis in Critical Bands: The sound’s spectrum is broken into frequency bands that correspond to the critical bands or auditory filters of human hearing. This is often done by converting the linear frequency axis into the Bark scale (a psychoacoustic frequency scale named after Heinrich Barkhausen). Each Bark corresponds to a critical band width of the cochlea. For example, 1 Bark is around 100 Hz wide at low frequencies but much wider at high frequencies. The input sound (e.g., a gear noise recording) is filtered into these critical bands, yielding a spectrum of sound pressure in each band [9].

- Incorporating Masking and Specific Loudness: Within each critical band, the model accounts for masking effects—louder components will raise the hearing threshold for nearby frequencies. Zwicker’s method calculates an “excitation pattern” along the basilar membrane, then derives specific loudness in each band (in sones per Bark). This involves non-linear compression (to reflect the ear’s dynamic range) and subtracting the absolute threshold of hearing. The output of this stage is a specific loudness distribution across the Bark scale [22].

- Integration to Total Loudness: Finally, the specific loudness values across all bands are summed up to give the total loudness in sones. If the sound is stationary, this might be a single number. For time-varying sounds (like a changing gear noise), loudness can be computed as a function of time (short-term loudness), and sometimes a percentile loudness (N5 or N10—the loudness value exceeded 5% or 10% of the time) is used to represent the loudness of fluctuating sounds [22].

4.2. Sharpness

4.3. Tonality

- Tone-to-Noise Ratio (TNR): For each detected tonal frequency, compute the difference in level between the tone and the noise floor in its critical band vicinity. The larger the difference, the more prominent (tonal) the tone is. Aures [28] proposed a tonality metric that effectively integrates the contributions of all tonal components weighted by such contrasts. Aures’s tonality (also called tonalness) is one classical psychoacoustic metric; it yields a value in a range roughly from 0 (no tone) to 1 (very tonal), or sometimes expressed in “tu” (tonality units) [28].

- Prominence Ratio (PR): Defined in certain standards, PR is the ratio of the sound energy in a critical band around the tone to the energy in adjacent bands. If the ratio exceeds certain thresholds, the tone is considered prominent. PR is more of a detection criterion but can be used as a metric too.

- Tone Audibility (ΔLta): Defined in DIN 45681 [29], this metric calculates how far a tone is above the masking noise threshold. DIN 45681 provides a procedure to quantify tonal audibility in dB for discrete tones in product sound measurements. High tonal audibility values indicate clearly audible tones.

4.4. Roughness

4.5. Fluctuation Strength

4.6. Summary of Metrics Characteristics

5. Applications in Gear Noise Analysis

- Automotive NVH and Sound Quality: optimizing the sound of vehicle transmissions and axles (e.g., reducing gear whine in passenger cars) [42].

- Gear Design and Manufacturing: guiding design modifications (like gear micro-geometry or tolerance scatter) to achieve better sound quality metrics, often by companies like ZF (a major gearbox manufacturer) or through academic–industry collaborations [32].

- Fault Diagnosis and Condition Monitoring: identifying gear faults (wear, misalignment, damage) by analyzing noise in psychoacoustic terms, which can sometimes reveal issues that traditional metrics miss [43].

- Product Quality Control (End-of-Line Testing): using psychoacoustic features in automated systems to detect if a gearbox sounds abnormal (as an alternative to human listening tests on the production line) [44].

- Comparative studies and fundamental research: academic works that compare traditional and psychoacoustic evaluations for gear noise, or that develop new metrics tailored to gears (e.g., specialized tonality metrics) [45].

5.1. Automotive Case Studies (Axle Whine and Transmission NVH)

5.2. Gear Design Optimization and Industrial Applications

5.3. Fault Diagnosis and Condition Monitoring

5.4. Product Quality Control

5.5. Academic Research and Case Studies

- A human perception of gear noise depending on gear geometry. They had subjects listen to recordings of gears with different helix angles, profile modifications, etc., and correlated subjective rankings with metrics. They found, for instance, that certain modifications reduced PA more effectively than they reduced SPL, highlighting again that psychoacoustic metrics guided to better solutions. Psychoacoustic metrics—such as loudness, tonality, fluctuation strength and sharpness—are not merely acoustic quantities, but indicators relevant to subjective noise quality. According to an article in Gear Technology [49], even a relatively quiet engine noise can be extremely disturbing if it appears as a high-pitched sound, which clearly illustrates that SPL alone is not sufficient for assessing noise comfort [51,52].

- Choi et al. [53] applied a genetic algorithm on gear macro-geometry (module, teeth number, etc.) optimizing for minimal noise. Interestingly, while their objective was mainly dB-based, the results were later evaluated for sound quality and did show improvements in metrics like sharpness (the example showing 3.1 dB(A) reduction along with harmonic noise reduction; one can infer psychoacoustic benefit though it was not explicitly quantified) [53].

- Yang [54] and others modeled complex gear dynamics to reduce vibration at the source. While that work is simulation-heavy, when it comes to evaluating outcomes, increasingly the researchers use psychoacoustic descriptors to say “the optimized design sounds quieter or smoother” in psychoacoustic terms, not just in raw forces.

6. Discussion

6.1. Benefits and Insights Gained

6.2. Challenges in Applying Psychoacoustic Metrics to Gears

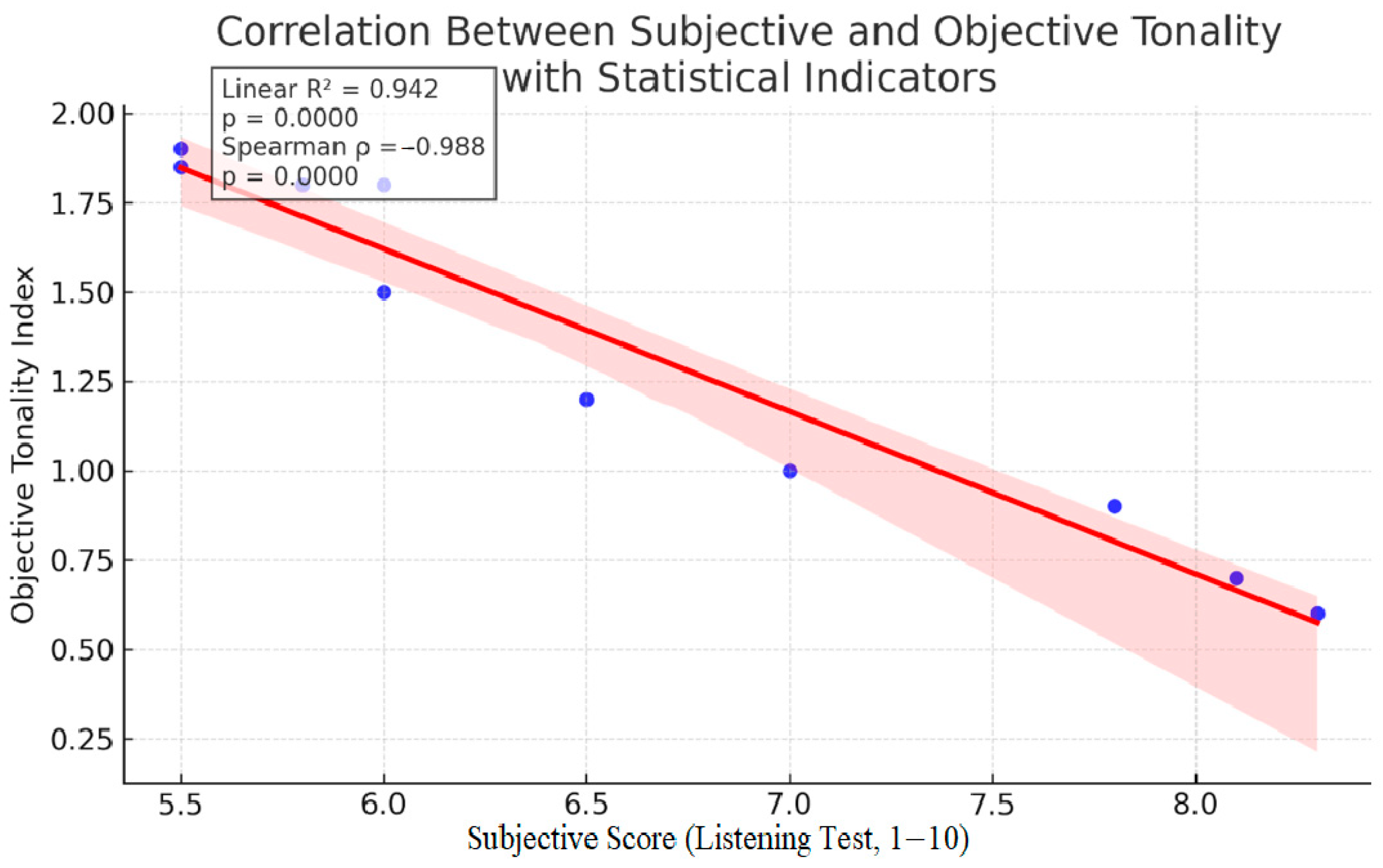

6.3. Validation and Human Perception Studies

- Paired Comparison and Ranking Tests: As used by Pietrzyk et al. [1], paired comparison forces a listener to choose which of two sounds is more pleasant or more annoying. By presenting many pairs and analyzing choices (often using Bradley-Terry model or similar), one can derive a ranking scale of perceived annoyance. This can then be compared to metrics. If listeners consistently prefer the sound with lower tonality metric, that validates the metric’s relevance. Paired comparisons are good because they are easier for subjects than rating scales, especially for small differences [1].

- Absolute Rating Scales: Some studies use a numerical scale or categorical scale (e.g., 1 to 10 annoyance, or opinions like “not noticeable” to “extremely annoying”). This can yield data for correlation (Pearson or Spearman correlation between metric values and mean subjective ratings). For instance, a researcher might play various gear noise recordings at different conditions and have listeners rate annoyance; then find that roughness (asper) correlates r = 0.8 while A-weighted dB correlates only r = 0.5, suggesting roughness is a better predictor.

- Jury Workshops with Sound Quality Metrics: Automakers sometimes conduct sound clinics with experts who both listen and measure. They might adjust a noise sample’s equalizer (tone controls) to reach a subjectively optimal sound, then analyze how metrics changed. This is more free-form but can reveal, say, that they always try to reduce sharpness when complaining of harshness.

- Psychoacoustic Model Validation: As mentioned, the concept of a composite like PA has been proposed. Validation involves seeing if PA correlates better with subjective annoyance than any single component. Often, loudness is weighted heavily because it is primary, but including sharpness and fluctuation terms improves the match to subjective annoyance data from experiments. In context of gear noise, one could test PA vs. actual annoyance votes for various gear whine samples.

- Real-world feedback: For products in the field, sometimes customer complaint data can serve as validation., e.g., if a new gear design that had lower tonality metric yields fewer NVH complaints from drivers, that retroactively validates the metric’s predictive power. This is of course less formal but very convincing to management.

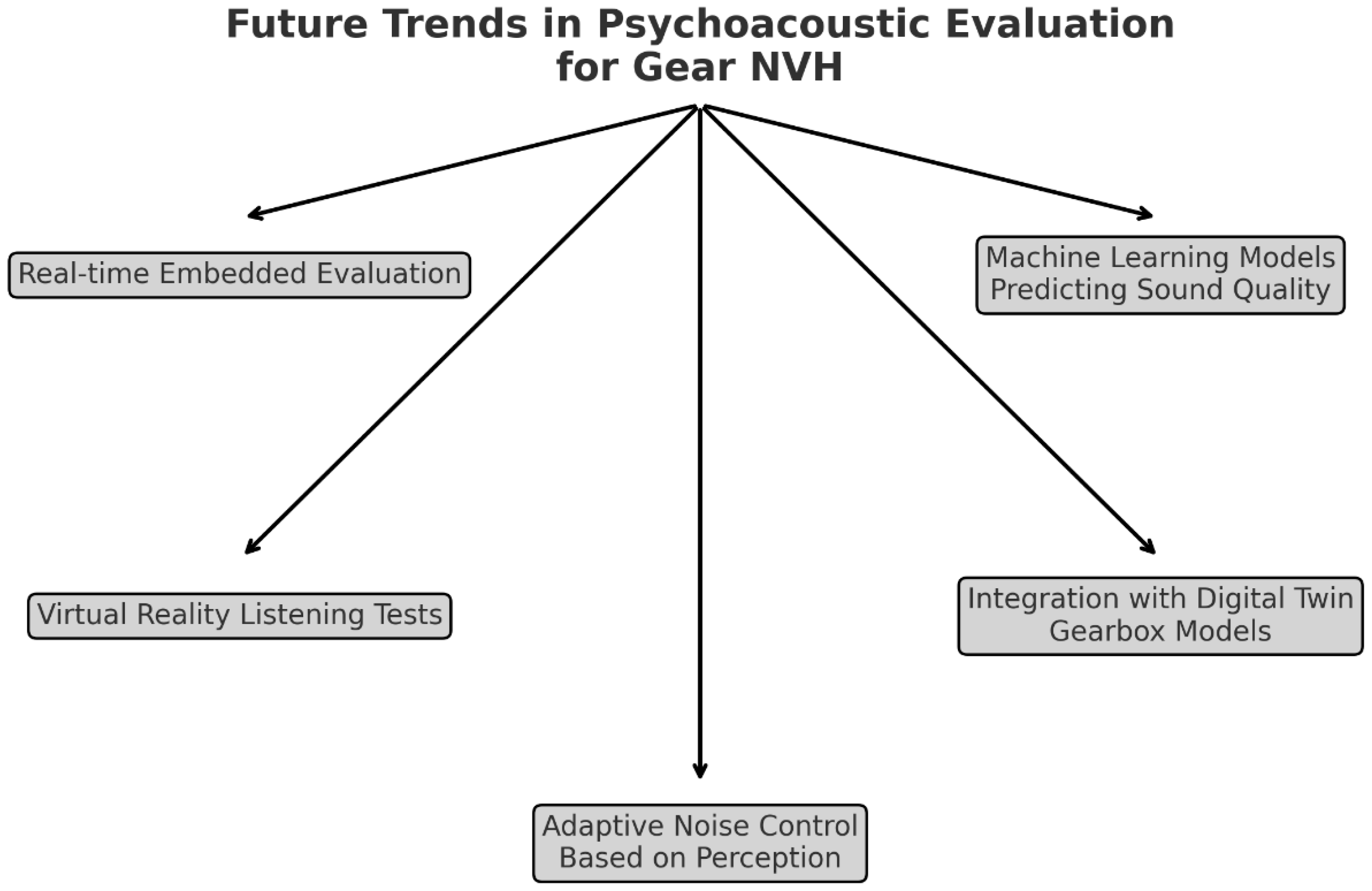

6.4. Limitations and Future Work

7. Conclusions

- Traditional vs. Psychoacoustic Approaches: Conventional noise metrics (dB levels, spectra, TE) are essential for quantifying and addressing the physical causes of gear noise, but they do not reliably indicate the pact of the noise. Psychoacoustic metrics bridge this gap by relating measurements to human perception. An integrated approach is ideal: use traditional analysis to identify and mitigate root causes, and use analysis to fine-tune the sound quality outcome.

- Understanding Psychoacoustic Metrics: Loudness, sharpness, tons, and fluctuation strength each capture a different auditory dimension of gear noise. Loudness correlates with overall intensity as heard; sharpness with high-frequency content; tonality with presence of tonal gear whine; roughness with rapid modulations (e.g., rattling); and fluctuation with slow amplitude beats. These metrics can be computed using established models.

- Applications in Gear Noise illustrate the practical benefits. Psychoacoustic metrics have been used to diagnose gear noise issues (identifying exactly why a noise is annoying), to compare design alternatives (choosing a design that yields lower perceived noise, not just lower SPL), and to develop innovative solutions (like micro-geometry modulation to reduce tonality). Automotive examples showed improved customer NVH by focusing on reducing sharpness and tonality of axle whine rather than only reducing amplitude. In manufacturing, psychoacoustic features enabled automated detection of faulty gearboxes with accuracy on par with human inspectors. These successes underline that Psychoacoustic metrics are not just academic; they have tangible impact on engineering outcomes.

- Challenges and Future Work: Applying psychoacoustic metrics to geared drives is not without difficulties. Non-stationary noise and multiple simultaneous phenomena can complicate metric calculation and interpretation. The lack of standardized methods for some metrics (tonality, roughness) can lead to inconsistency. However, ongoing research and development are addressing these issues. New metrics and analysis techniques are being developed for time-varying sounds, and there is movement toward industry standards that include sound quality. Additionally, increasing computational power and simulation fidelity will likely allow psychoacoustic optimization to be a part of the early design phase, not just a post-test evaluation. The future geared drive might be “tuned” for sound quality in much the same way engines have been, using these metrics as design targets.

- Human-centric evaluation is essential. Psychoacoustic metrics—such as loudness, sharpness, tonality, roughness, and fluctuation strength—provide an additional dimension for assessing gearbox noise beyond conventional energy-based parameters.

- Integration into engineering workflows is viable. The review shows that psychoacoustic analysis can be effectively combined with CAE simulations, test bench data, and machine learning algorithms to support noise optimization at earlier design stages.

- Industrial adoption is emerging. While still limited, there are clear trends in automotive and transmission manufacturing towards including psychoacoustic criteria in NVH targets, especially in EVs where tonal noise is more prominent.

- Real-time psychoacoustic evaluation: Development of embedded algorithms that can process psychoacoustic metrics in real-time during drivetrain operation, enabling adaptive control strategies for noise reduction.

- Coupling with advanced CAE and digital twins: Integration of psychoacoustic evaluation modules into multi-body dynamics and vibroacoustic simulation platforms to predict perceived sound quality directly from design data.

- Machine learning and big data analytics: Leveraging large datasets of measured and simulated NVH signals to train AI models capable of predicting psychoacoustic outcomes from early-stage design parameters or manufacturing tolerances.

- Psychoacoustics for electric drivetrains: Focused studies on EV-specific tonal and high-frequency noise, where masking by combustion engines is absent, making perceived noise more critical to passenger comfort.

- Standardization and benchmarking: Establishing standardized procedures for psychoacoustic measurement and evaluation in gearbox NVH, facilitating cross-comparison between research groups and industry applications.

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Pietrzyk, T.; Georgi, M.; Schlittmeier, S.; Schmitz, K. Psychoacoustic Evaluation of Hydraulic Pumps. Sustainability 2021, 13, 7320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, D.; Shi, Q.; Yi, P. Psychoacoustic Analysis of Gear Noise with Gear Faults. SAE Int. J. Passeng. Cars–Mech. Syst. 2016, 9, 459–464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Genuit, K. Need for Standardization of Psychoacoustics. J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 2010, 127, 1880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Groby, J. Introduction to Psychoacoustics and Psychoacoustic Tests; University of Zagreb: Zagreb, Croatia, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Seeber, B. Echoes from the Archives of the Munich School of Psychoacoustics. In Proceedings of the 10th Convention of the European Acoustics Association Forum Acusticum, Torino, Italy, 11–15 September 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferguson, S.; Cabrera, D.; Beilharz, K.; Song, H. Using Psychoacoustical Models for Information Sonification. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Auditory Display, London, UK, 20–23 June 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Schell-Majoor, L.; Rennies, J.; Ewert, S.; Kollmeier, B. Modeling Sound Quality from Psychoacoustic Measures; Institute of Noise Control Engineering: Wakefield, MA, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- DIN 45631:1991-03; Acoustics—Calculation of Loudness Level and Loudness from the Sound Spectrum (Zwicker Method). DIN: Berlin, Germany, 1991. Available online: https://webstore.ansi.org/standards/din/din456311991de (accessed on 27 October 2025).

- ISO 532-1:2017; Acoustics—Methods for Calculating Loudness—Part 1: Zwicker Method. ISO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2017. Available online: https://www.iso.org/standard/63069.html (accessed on 27 October 2025).

- ISO 532-2; Acoustics—Methods for Calculating Loudness—Part 2: Zwicker Method. ISO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2017.

- Fastl, H. Advanced Procedures for Psychoacoustic Noise Evaluation. In Proceedings of the 6th European Confernce on Noise Control 2006, Tampere, Finland, 30 May–1 June 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Pastor-Aparicio, A.; Segura-García, J.; Lopez-Ballester, J.; Felici-Castell, S.; García-Pineda, M.; Perez-Solano, J. Psychoacoustic Annoyance Implementation with Wireless Acoustic Sensor Networks for Monitoring in Smart Cities. IEEE Internet Things J. 2020, 7, 128–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ziemer, T.; Yu, Y.; Tang, S. Using Psychoacoustic Models for Sound Analysis in Music. In Proceedings of the 8th Annual Meeting of the Forum for Information Retrieval Evaluation, Kolkata, India, 8–10 December 2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheerla, G.; Pulugundla, K.; Kolla, K.; Sathyanarayana, P. Solving Whine Noise in Electric Vehicles: A Comprehensive Study Using Experimental and Multiphysics Techniques; SAE Tech. Pap. Ser.; SAE International: Warrendale, PN, USA, 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, Y.; Zhang, T. Sound Quality of the Acoustic Noise Radiated by PWM-Fed Electric Powertrain. IEEE Trans. Ind. Electron. 2018, 65, 4534–4541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Altinsoy, M. The Evaluation of Conventional, Electric and Hybrid Electric Passenger Car Pass-By Noise Annoyance Using Psychoacoustical Properties. Appl. Sci. 2022, 12, 5146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ECMA-418-2:2022; Psychoacoustic Metrics for ITT Equipment—Part 2: Models Based on Human Perception, 2nd ed. Ecma International: Geneva, Switzerland, 2022. Available online: https://www.ecma-international.org/wp-content/uploads/ECMA-418-2_2nd_edition_december_2022.pdf?trk=organization_guest_main-feed-card_reshare-copy (accessed on 27 October 2025).

- Sottek, R.; Lobato, T. Applications of the Psychoacoustic Tonality Method. J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 2023, 153, A149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zakrajsek, J.J.; Townsend, D.P. The Root Cause for Gear Noise Excitation. Gear Solut. 2000. Available online: https://gearsolutions.com/features/the-root-cause-for-gear-noise-excitation/ (accessed on 27 October 2025).

- Genuit, K. The Sound Quality of Vehicle Interior Noise: A Challenge for the NVH-Engineers. Int. J. Veh. Noise Vib. 2004, 1, 158–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, X.; Liu, S.; Shi, Z.; Yue, H. Noise Analysis and Optimization of the Gear Transmission System for Two-Speed Automatic Transmission of Pure Electric Vehicles. Mech. Sci. 2023, 14, 361–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fastl, H. Psychoacoustics and Sound Quality. Technical Acoustics Group, Technical University of Munich, 2007. Available online: https://mediatum.ub.tum.de/doc/1138438/document.pdf (accessed on 27 October 2025).

- Fastl, H. Psycho Acoustics and Sound Quality. In Communication Acoustics; Blauert, J., Ed.; Springer: Berlin, Germany, 2005; pp. 139–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swift, S.H.; Gee, K.L. Extending Sharpness Calculation for an Alternative Loudness Metric Input. J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 2017, 142, EL549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moore, B.C.J.; Glasberg, B.R. A Revision of Zwicker’s Loudness Model. Acust. Acta Acust. 1996, 82, 335–345. [Google Scholar]

- Zwicker, E.; Fastl, H. Roughness. In Psychoacoustics: Facts and Models, 3rd ed.; Springer: Berlin, Germany, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Deutsches Institut für Normung. DIN 45692: Measurement Technique for the Simulation of the Auditory Sensation of Fluctuation Strength; Beuth Verlag: Berlin, Germany, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Aures, W. Procedure for Calculating the Sensory Pleasantness of Various Sounds. Acustica 1985, 59, 130–141. [Google Scholar]

- DIN 45681; Acoustics—Determination of Tonal Components of Noise and Determination of a Tone Adjustment for the Assessment of Noise Immissions. Beuth Verlag: Berlin, Germany, 2005.

- Kim, E.Y.; Jang, J.U.; Lee, S.K. Tonality Design for Sound Quality Evaluation for Gear Whine Sound. Trans. Korean Soc. Noise Vib. Eng. 2012, 22, 1172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brecher, C.; Löpenhaus, C.; Kasten, M. Psychoacoustic Optimization of Gear Noise: Chaotic Scattering of Micro Geometry and Pitch on Cylindrical Gears. Gear Technol. 2021. Available online: https://www.geartechnology.com/psychoacoustic-optimization-of-gear-noise-chaotic-scattering-of-micro-geometry-and-pitch-on-cylindrical-gears (accessed on 27 October 2025).

- Kasten, M.; Brecher, C.; Löpenhaus, C. Reduction of the Tonality of Gear Noise by Application of Topography Scattering for Ground Bevel Gears. Gear Solut. 2021. Available online: https://gearsolutions.com/features/reduction-of-the-tonality-of-gear-noise-by-application-of-topography-scattering-for-ground-bevel-gears (accessed on 27 October 2025).

- Daniel, P.; Weber, R. Psychoacoustical Roughness: Implementation of an Optimized Model. Acta Acust. United Acust. 1997, 83, 113–123. [Google Scholar]

- Hoeldrich, R.; Pflueger, M. A Parametrized Model of Psychoacoustical Roughness for Objective Vehicle Noise Quality Evaluation. J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 1999, 105, 1371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fastl, H. The Hearing Sensation Roughness and Neuronal Responses to AM Tones. Hear. Res. 1990, 46, 293–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hörmann, H.; Zwicker, E. Loudness of Noise Containing Tones. Acustica 1972, 27, 229–233. [Google Scholar]

- Fastl, H. Fluctuation Strength and Temporal Masking Patterns of Amplitude Modulated Broadband Noise. Hear. Res. 1982, 8, 59–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fastl, H.; Zwicker, E. Fluctuation Strength. In Psychoacoustics; Springer: Berlin, Germany, 2007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poeppel, D.; Assaneo, M.F. Speech Rhythms and Their Neural Foundations. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 2020, 21, 322–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kane, P.V.; Andhare, A.B. Application of Psychoacoustics for Gear Fault Diagnosis Using Artificial Neural Network. J. Low Freq. Noise Vib. Act. Control 2016, 3, 207–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simmons, D. Test Signals for Validating Sound Quality Measurement Instrumentation. Proc. Inst. Acoust. 2005, 27, 189–194. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, H.; Kim, S.; Lee, S. Design of New Sound Metric and Its Application for Quantification of an Axle Gear Whine Sound by Utilizing Artificial Neural Network. J. Mech. Sci. Technol. 2009, 23, 1182–1193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, A.; Nakra, B.C. Vibration and Noise Analysis for Gearbox Fault Detection Using Acoustic Signals. Appl. Acoust. 2009, 70, 1378–1385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.J.; Lee, H.H.; Lee, S.K. Sound Quality Evaluation for the Axle Gear Noise in the Vehicle. SAE Int. J. Passeng. Cars Mech. Syst. 2008, 1, 1514–1521. [Google Scholar]

- Jiang, Q.; Liu, X.; Wang, H.; Zhang, Y.; Li, P. Correlation of the Sound Quality and Vibration of End-of-Line Testing for Automatic Transmission. Meas. Control. 2024, 57, 1348–1362. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, B.; Yang, S. A Study on Contribution Analysis Using Operational Transfer Path Analysis Based on the Correlation between Subjective Evaluation and Zwicker’s Sound Quality Index for Sound Quality of Forklifts. Korean Soc. Fluid Power Constr. Equip. 2016, 13, 19–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Brecher, C.; Gorgels, C.; Carl, C.; Brumm, M. Benefit of Psychoacoustic Analyzing Methods for Gear Noise Investigation. Gear Technol. 2011, 28, 49–55. [Google Scholar][Green Version]

- Marrant, B. An Automated Simulation Approach of Drive Trains towards Tonality-Free Wind Turbines; ZF Wind Power Antwerpen NV: Lommel, Belgium, 2020. [Google Scholar][Green Version]

- Gear Technology. Aspects of Gear Noise, Quality, and Manufacturing Technologies for Electromobility; Gear Technology: Elk Grove Village, IL, USA, 2023. [Google Scholar][Green Version]

- Garanto, V.; Geng, Z.; Hu, J.; Deng, X.; Yang, W.; Wang, H. Sound Quality Development Using Psychoacoustic Parameters with Special Focus on Powertrain Noise; SAE Tech. Pap.; SAE International: Warrendale, PA, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wißbrock, P.; Richter, Y.; Pelkmann, D.; Ren, Z.; Palmer, G. Cutting Through the Noise: An Empirical Comparison of Psychoacoustic and Envelope-Based Features for Machinery Fault Detection. arXiv 2022, arXiv:2211.01704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qian, K.; Hou, Z.; Sun, Q.; Yang, G.; Sun, D.; Liu, R. Evaluation and Optimization of Sound Quality in High-Speed Trains. Appl. Acoust. 2021, 174, 107830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, C.; Ahn, H.; Yu, J.; Han, J.S.; Kim, S.C.; Park, Y.J. Optimization of Gear Macro Geometry for Reducing Gear Whine Noise in Agricultural Tractor Transmission. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2021, 188, 106358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Li, W.; Lu, H.; Peng, Z. Development of a Deep Neural Network for Intelligent Fault Diagnosis of Rotating Machinery. J. Manuf. Process. 2020, 59, 116–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zakri, K.W.; Sarwono, R.S.J.; Santosa, S.P.; Soelami, F.X.N. Modeling and Validation of Acoustic Comfort for Electric Vehicle Using Hybrid Approach Based on Soundscape and Psychoacoustic Methods. World Electr. Veh. J. 2025, 16, 64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Metric | Primary Sensitivity (Perceptual Aspect) | Computational Cost | Standardization Status |

|---|---|---|---|

| Loudness (sone) | Overall perceived intensity; accounts for frequency weighting and masking. Affected by total sound energy and spectrum (critical bands). | Moderate—requires critical band spectral analysis and masking model. | ISO 532-1:2017; ISO 532-2:2017 Widely standardized and used. |

| Sharpness (acum) | High-frequency content of sound (“brightness”). Increases with more energy in >~1 kHz range relative to total loudness. | Low—calculated from specific loudness distribution (post-loudness calculation) with a simple weighting function. | DIN 45692:2009 [24] standardized calculation Can also be applied with Moore loudness. |

| Tonality (tonal units or dB tonality) | Prominence of tonal components (gear whine tones) over noise background. Sensitive to distinct frequency components (mesh frequency, harmonics). | Moderate—involves spectral analysis and identification of tones vs. noise. Possibly multiple steps: tone finding, masking assessment. | No single metric standard across all fields; methods defined in DIN 45681 (tone audibility ΔL). Aures’s tonality is used. Ongoing research for time-varying tonality metrics. |

| Roughness (asper) | Rapid amplitude modulations (~30–150 Hz) producing a “harsh” or rattling sensation. Sensitive to modulation depth and frequency (max ~70 Hz) | Moderate—requires demodulating the signal in critical bands and analyzing modulation spectra in the roughness range. | Defined in psychoacoustic literature. No ISO standard; unit asper commonly used. Implementation typically per Zwicker’s model. |

| Fluctuation Strength (vacil) | Slow amplitude modulations (~<20 Hz, peak sensitivity ~4 Hz) causing a “wavy” or throbbing loudness variation. | Moderate—similar to roughness calculation, but focusing on low-frequency envelope fluctuations. | Defined in the literature; no ISO standard; unit vacil used for 4 Hz reference. Often included in sound quality analysis tools. |

| Study (Year) | Context | Gear Type and Test Conditions | Psychoacoustic Metrics Analyzed | Key Results and Conclusions |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Brecher et al., [47]. | Demonstration of psychoacoustic method benefits for gear noise investigation (early study). Focus on correlating perceptual noise quality with gear design parameters. | Automotive gearbox gear sets (lab tests); compared noise from gear pairs with different geometries and quality levels. | Loudness, Sharpness, Roughness, Tonality (evaluated alongside traditional SPL). | Conventional acoustic metrics (dB, FFT) are insufficient for evaluating gear noise quality, while psychoacoustic metrics—such as tonality, roughness, and sharpness—vary systematically with gear speed and design changes, correlate with human perception, and enable sound-quality–oriented design optimization. |

| Kim et al., [30]. | Automotive gear whine sound quality evaluation. Studied tonal axle whine noise in a production SUV rear drivetrain. | Hypoid rear axle gear whine (SUV); non-stationary tonal noise varying with vehicle speed (frequency-modulated gear whine). Tests included on-road or dyno measurements of axle noise for sound quality analysis. | Tonality (used Aures’s tonality metric from prior work; developed a new Prominence Ratio-based tonality metric for time-varying tones), Overall Loudness (for reference | The existing tonality index failed to predict annoyance for modulated gear whine. A new high-resolution tonality metric correlated well with subjective evaluations. Applying this metric enabled rear-axle design changes that reduced perceived whine. This demonstrates the value of specialized tonality metrics for gear noise. |

| Guo et al., [2]. | Gear fault diagnosis using psychoacoustic analysis. Investigated noise signatures of gear defects for condition monitoring. | Automotive spur gear transmission (simulated gearbox noise spectra) with induced faults (gear tooth wear, misalignment). Noise signals were synthesized and analyzed in lieu of physical tests. | Loudness, Sharpness, Tonality, Spectral Centroid, Kurtosis (psychoacoustic metrics combined with spectral features) | Psychoacoustic metrics identified fault-specific noise patterns missed by traditional analysis. Misalignment introduced sideband modulations that increased roughness and tonality. These metrics provided more diagnostic insight into gear condition than standard methods. Setting thresholds on them enables early fault detection and improved sound-quality design. |

| Kim & Yang, [46]. | Forklift cabin noise sound quality study. Analyzed operator-perceived noise in industrial vehicles, emphasizing comfort in heavy equipment. | Forklift drivetrain and hydraulic noise (construction equipment); in-cabin noise recorded during operation. Conducted blind listening tests with forklift operators in multiple countries. | Zwicker’s Sound Quality Index (composite metric combining Loudness, Sharpness, etc.), with specific analysis of Loudness and Sharpness contributions. | Loudness and sharpness were the main factors affecting perceived sound quality in forklift cabins. The Zwicker index correlated strongly with operator comfort ratings. OTPA identified which noise sources most influenced loudness and sharpness at the driver’s ear. Psychoacoustic indices reliably reflected operator preferences and guided noise-source targeting. |

| Kane & Andhare, [40]. | Automated end-of-line (EOL) gear inspection via AI. Explored replacing human experts with an ANN classifier using sound-quality features. | Automotive transmission EOL test bench; recordings of gearboxes labeled “good” vs. “faulty” during quality control run-up. Training and testing were performed on this dataset under controlled conditions. | Loudness, Sharpness, Roughness, Tonality (a broad psychoacoustic feature set), plus statistical features (e.g., variance, etc.) as inputs to a neural network. | The model achieved about 98–99% accuracy in classifying healthy and defective gearboxes. Psychoacoustic features allowed the ANN to match expert listeners in detecting faulty sounds. Models using perceptual metrics outperformed those based only on vibration features. This shows that psychoacoustic metrics can replace human judgment in automated gear noise inspection. |

| Jiang et al., [45]. | Correlation of the sound quality and vibration of end-of-line testing for automatic transmission. | Automatic transmission end-of-line (EOL) testing in industrial production; comparing psychoacoustic parameters and vibration data against human subjective ratings. | Loudness, Sharpness, Roughness, and Tonality (also composite sound quality indices). | Psychoacoustic metrics correlated strongly with listener perception and vibration-based indicators. The study confirmed that perceptual features (e.g., tonality, sharpness) better predict subjective annoyance than A-weighted SPL. Results support replacing subjective listening tests with automated psychoacoustic evaluation in transmission QA. |

| Kim et al., [44]. | Sound quality evaluation for the axle gear noise in the vehicle. | Automotive axle and transmission NVH evaluation. Each gearbox or axle run on a dynamometer test bench; aiming to introduce objective psychoacoustic-based criteria for quality assurance. | Loudness, Sharpness, Tonality, and Psychoacoustic Annoyance (PA). | The study developed and validated a psychoacoustic framework for assessing gear noise quality in vehicle transmissions. Objective metrics such as tonality and sharpness showed strong correlation with subjective evaluations, enabling reliable detection of abnormal gear noise during production testing. Integrating psychoacoustic evaluation improved NVH quality control and alignment with perceived sound quality. |

| Garanto et al., [50]. | Automotive powertrain sound quality development. Proposed a comprehensive framework using psychoacoustic criteria in vehicle NVH design and evaluation. | Full vehicle powertrain (engine/motor + transmission) in development; combined simulation and physical NVH tests with perceptual analysis in a loop. Especially relevant for EV and hybrid drivetrain noise refinement. | Loudness, Sharpness, Roughness, Tonality (used in concert to evaluate sound quality). Also aggregated “sound quality” indices for annoyance. | Integrating psychoacoustic metrics into the design process improved noise refinement beyond traditional dB measures. Correlating perceptual metrics with engineering data revealed which attributes most affected perceived sound quality. Using loudness and tonality metrics early in design improved alignment with customer comfort goals in EVs and hybrids. The study established a practical workflow where psychoacoustic evaluation enhances conventional NVH analysis. |

| Marrant, [48]. | Wind turbine gearbox noise optimization. Explored design approaches to achieve “tonality-free” wind turbines for reduced community noise annoyance. | Wind turbine multi-MW gearbox (wind energy drivetrain); simulation-based study optimizing gear design and micro-modifications to minimize tonal mesh noise. Possibly validated by test data from wind turbines (not detailed here). | Tonality (primary focus, e.g., tone-to-noise ratio or psychoacoustic tonality metrics); also considered overall loudness to ensure no large increase in broadband noise. | Tonal gear noise in wind turbines can cause strong annoyance even at low levels. An automated design simulation modified gear micro-geometry to reduce tonal components. This approach lowered tonal prominence without increasing overall sound energy. Setting psychoacoustic tonality targets helps design wind turbine gearboxes that meet noise comfort requirements. |

| Brecher et al., [31]. | Psychoacoustic optimization of EV gear whine via micro-geometry scatter (industry case study). Investigated intentional gear deviations to improve sound quality. | EV single-speed reduction gear for automotive drivetrain (ZF/RWTH study). Applied “chaotic” pitch and micro-geometry variations to gear teeth; noise measured on test bench for baseline vs. modified gears. | Loudness, Sharpness, Roughness, Tonality; also composite Psychoacoustic Annoyance (PA) as an overall sound quality metric. | Slight random variations in gear pitch and tooth geometry reduced tonal gear whine by about 50%. Psychoacoustic metrics, especially tonality and sharpness, showed major improvement and lower annoyance. Listeners rated the modified gears as noticeably more pleasant despite similar SPL values. The study introduced a design approach that trades minor spectral purity for better perceived sound quality. |

| Kasten et al., [32]. | Reducing bevel gear whine via topography scattering. Extended psychoacoustic gear optimization to ground bevel gears in automotive applications. | Automotive bevel gear pair (rear axle or differential) tested under load on a noise rig and in-vehicle. Employed targeted micro-topography deviations on gear teeth and compared noise of two gear variants (baseline vs. scattered surface). | Loudness, Tonality (primary metrics for evaluation). Standard gear mesh excitation metrics (TE) were also measured to link physical vs. perceptual effects. | Topography scattering with controlled surface irregularities significantly reduced bevel gear tonality. Smeared excitation lowered tonal amplitudes but slightly increased broadband noise. Psychoacoustic analysis showed an overall improvement in perceived sound quality. Minimizing tonal metrics proved more effective for gear noise refinement than reducing overall SPL. |

| Zakri et al., [55]. | Holistic EV interior noise comfort (soundscape + psychoacoustics). Assessed how gear noise in quiet EVs affects user experience and preferences. | Electric vehicle passenger cabin noise, including reduction gear whine and motor/inverter sounds (no engine masking). Combined objective metric measurements with subjective soundscape evaluation (user surveys in situ or via playback). | Loudness, Sharpness, Tonality, Roughness (used to quantify the EV’s interior noise character) alongside subjective “soundscape” descriptors. | In quiet EV cabins, even moderate gear whine becomes noticeable and affects comfort. Psychoacoustic metrics combined with soundscape analysis explained both annoyance and user preference. Some drivers found slight tonal whine acceptable or useful as operational feedback. Evaluating gear noise in the context of user expectations ensures EV sound tuning balances comfort and information. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Published by MDPI on behalf of the World Electric Vehicle Association. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Horvath, K. Application of Psychoacoustic Metrics in the Noise Assessment of Geared Drives. World Electr. Veh. J. 2025, 16, 611. https://doi.org/10.3390/wevj16110611

Horvath K. Application of Psychoacoustic Metrics in the Noise Assessment of Geared Drives. World Electric Vehicle Journal. 2025; 16(11):611. https://doi.org/10.3390/wevj16110611

Chicago/Turabian StyleHorvath, Krisztian. 2025. "Application of Psychoacoustic Metrics in the Noise Assessment of Geared Drives" World Electric Vehicle Journal 16, no. 11: 611. https://doi.org/10.3390/wevj16110611

APA StyleHorvath, K. (2025). Application of Psychoacoustic Metrics in the Noise Assessment of Geared Drives. World Electric Vehicle Journal, 16(11), 611. https://doi.org/10.3390/wevj16110611