Leveraging User Preferences to Develop Profitable Business Models for Electric Vehicle Charging †

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Motivation & Prior Research

1.2. Objectives

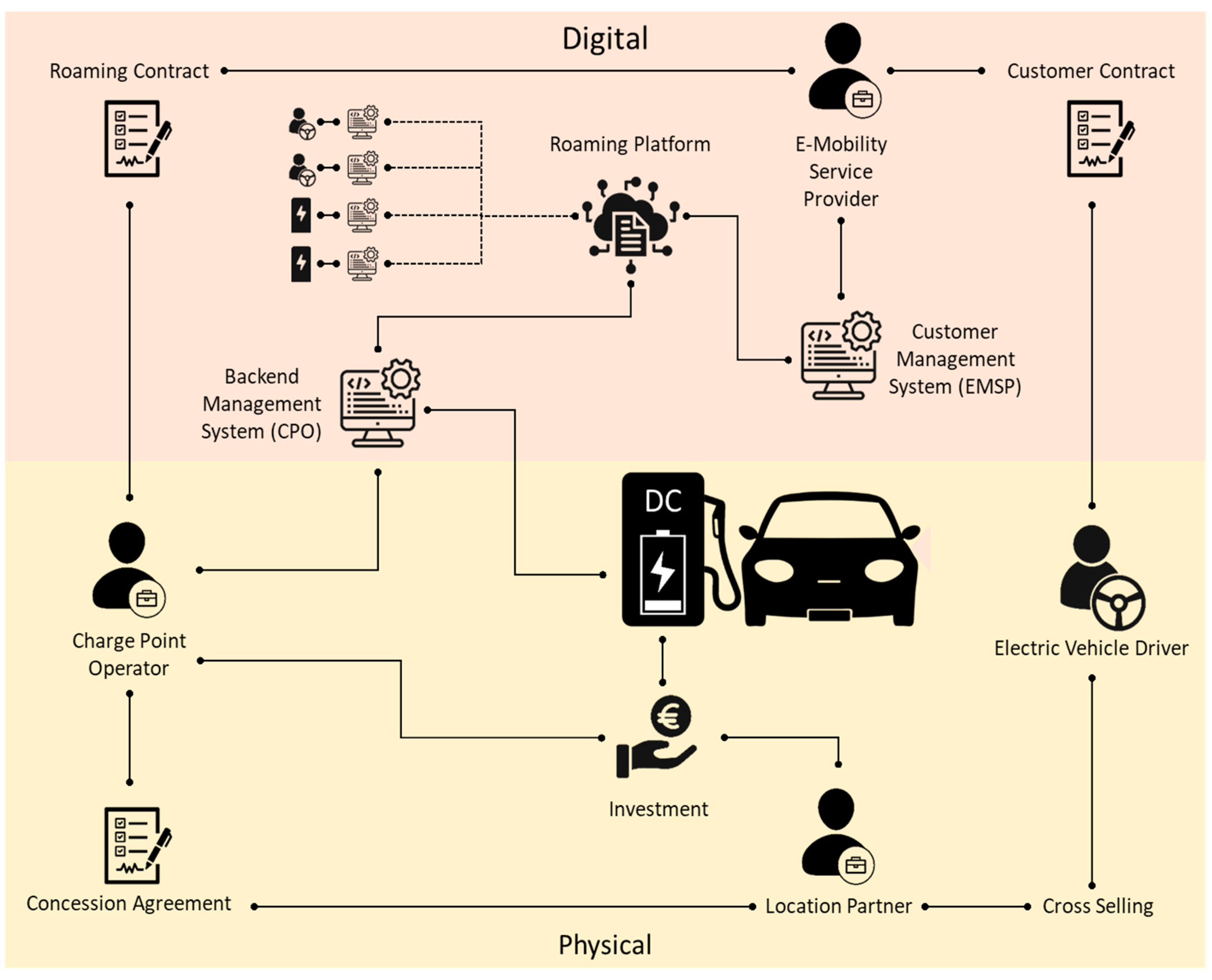

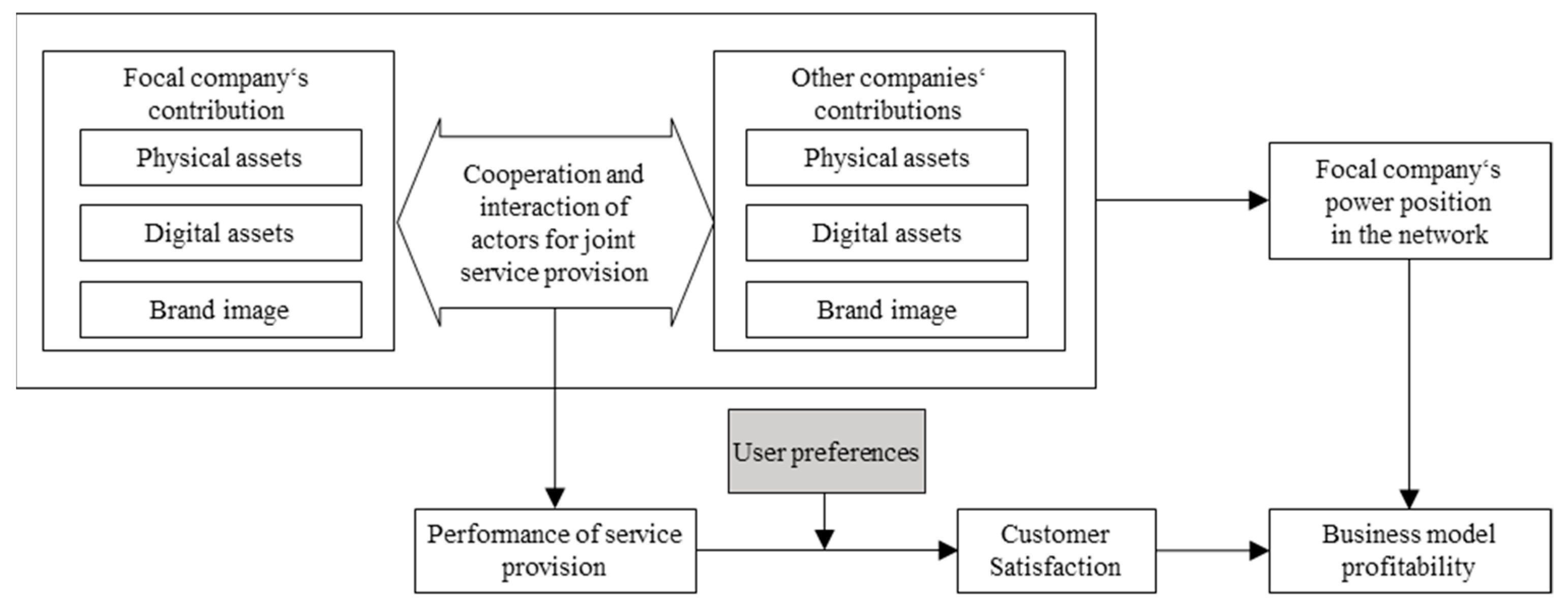

1.3. EV Charging as One Example for an Emerging Mobility Ecosystem: Cooperation and Interaction of Actors for Joint Service Provision

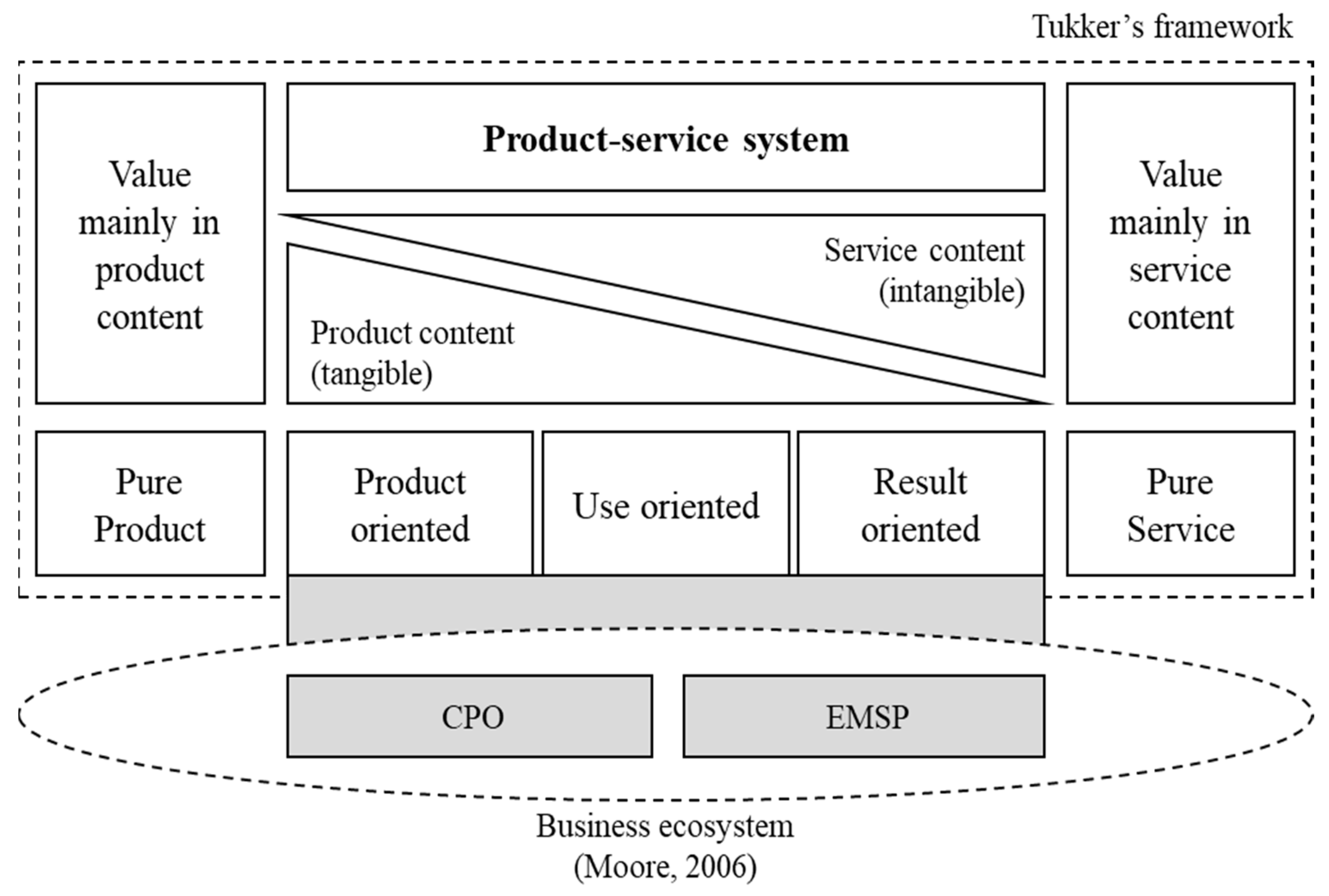

2. Materials and Methods: State of the Art Used to Develop a Conceptual Framework

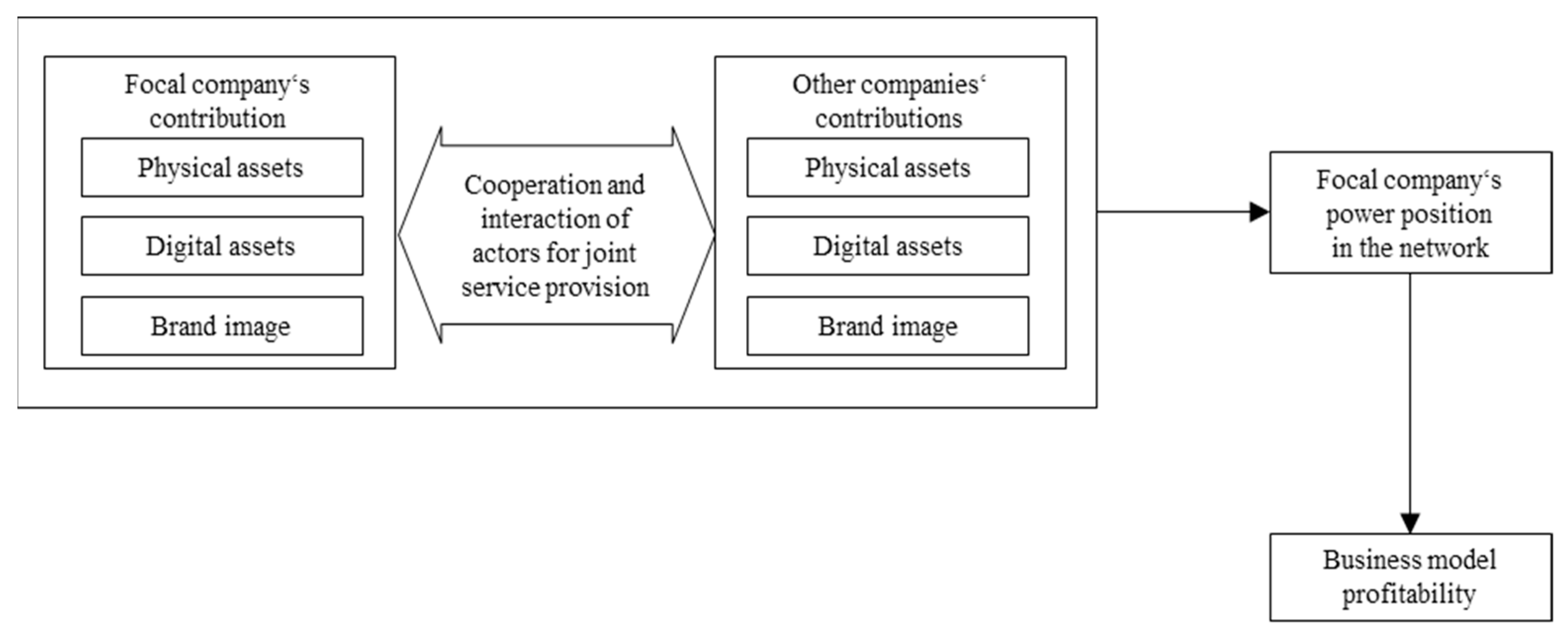

2.1. Quality-of-Service Provision Defined by Digital and Physical Assets and Brand Image

2.2. Power Balance in the Value Network

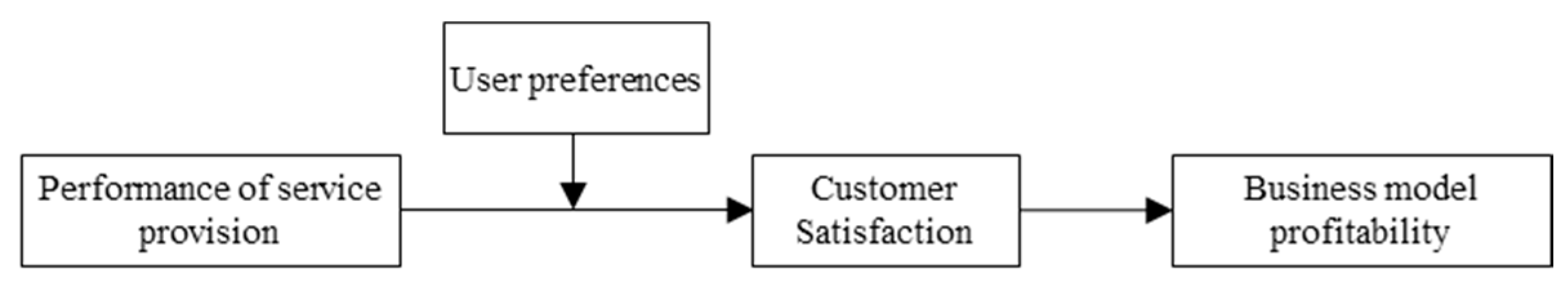

2.3. Customer Satisfaction: Antecedents and Its Impact on Business Model Profitability

2.4. Overall Hypothesis

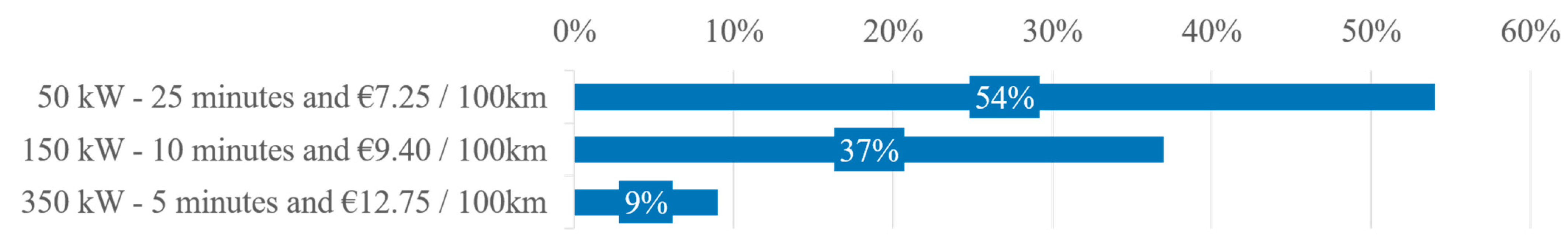

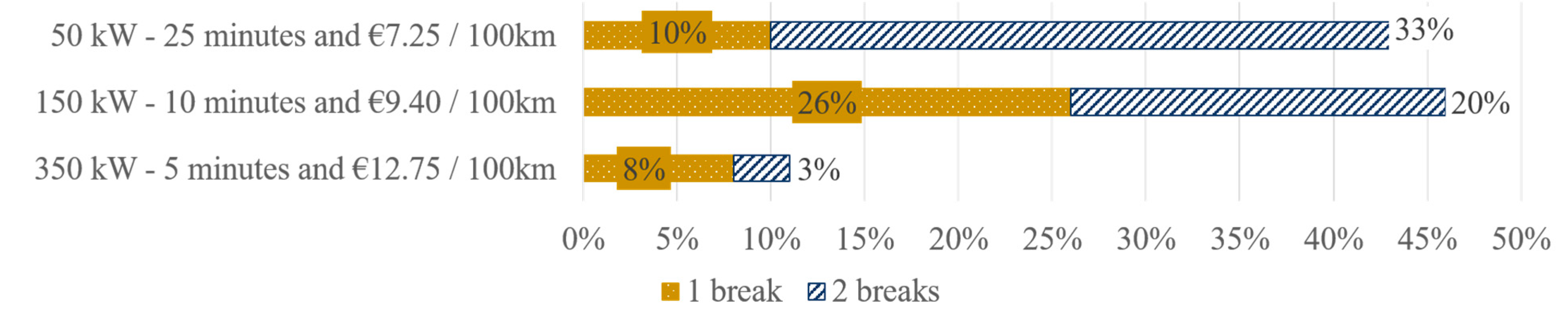

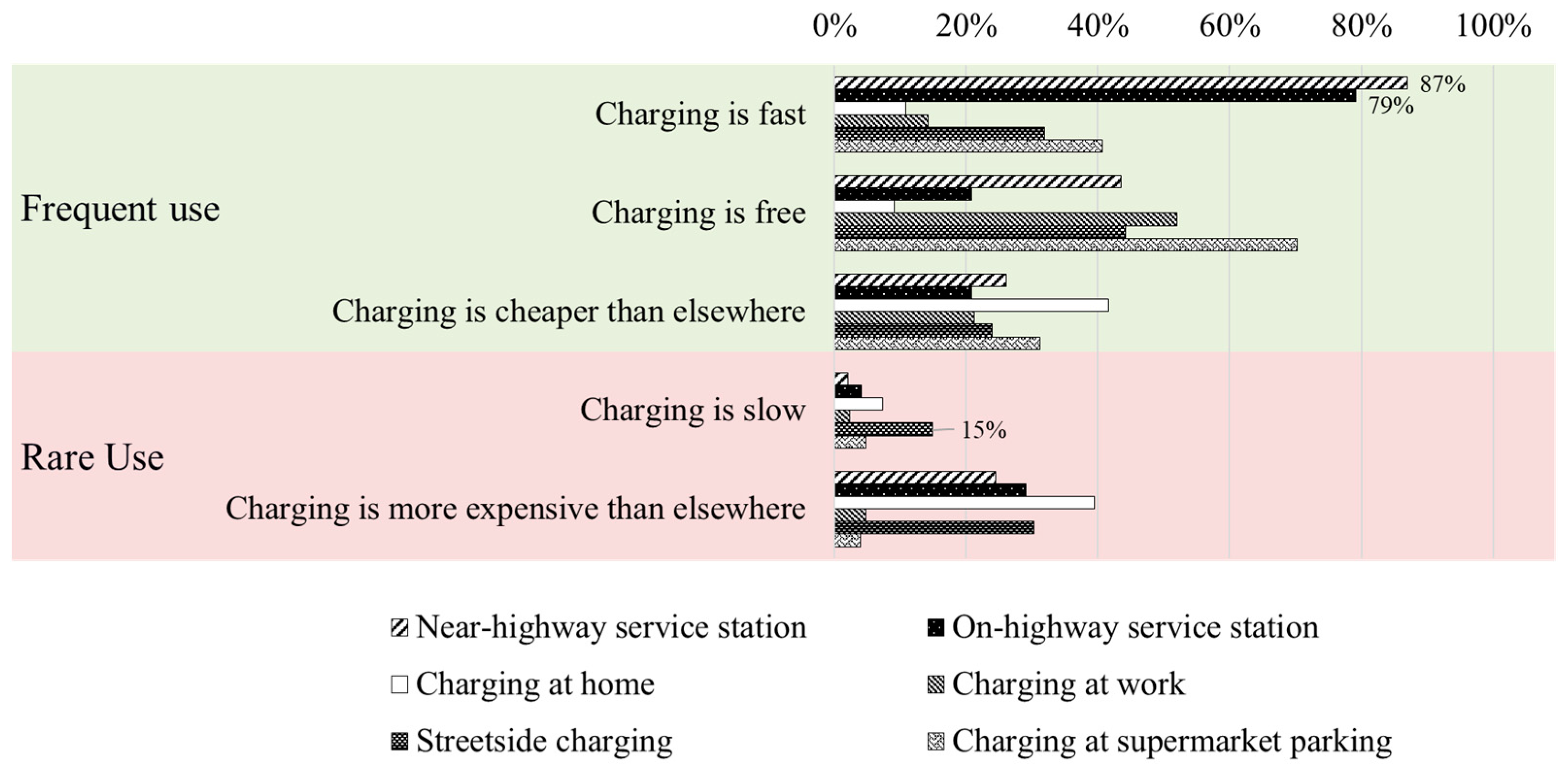

3. Results: Examining User Preferences as One Observable Element of the Framework

4. Discussion—Case Studies Exemplifying the Framework

- Companies that have a very strong position (+++) in one of the three resource classes that define the quality-of-service provision demand a higher price for fast charging. They do this even though a high price is one of the main drivers for not choosing a charging option. However, the main reason for (fast) charging at highway service stations (cf. Figure 9) is “charging is fast”. Thus, price is not a dealbreaker.

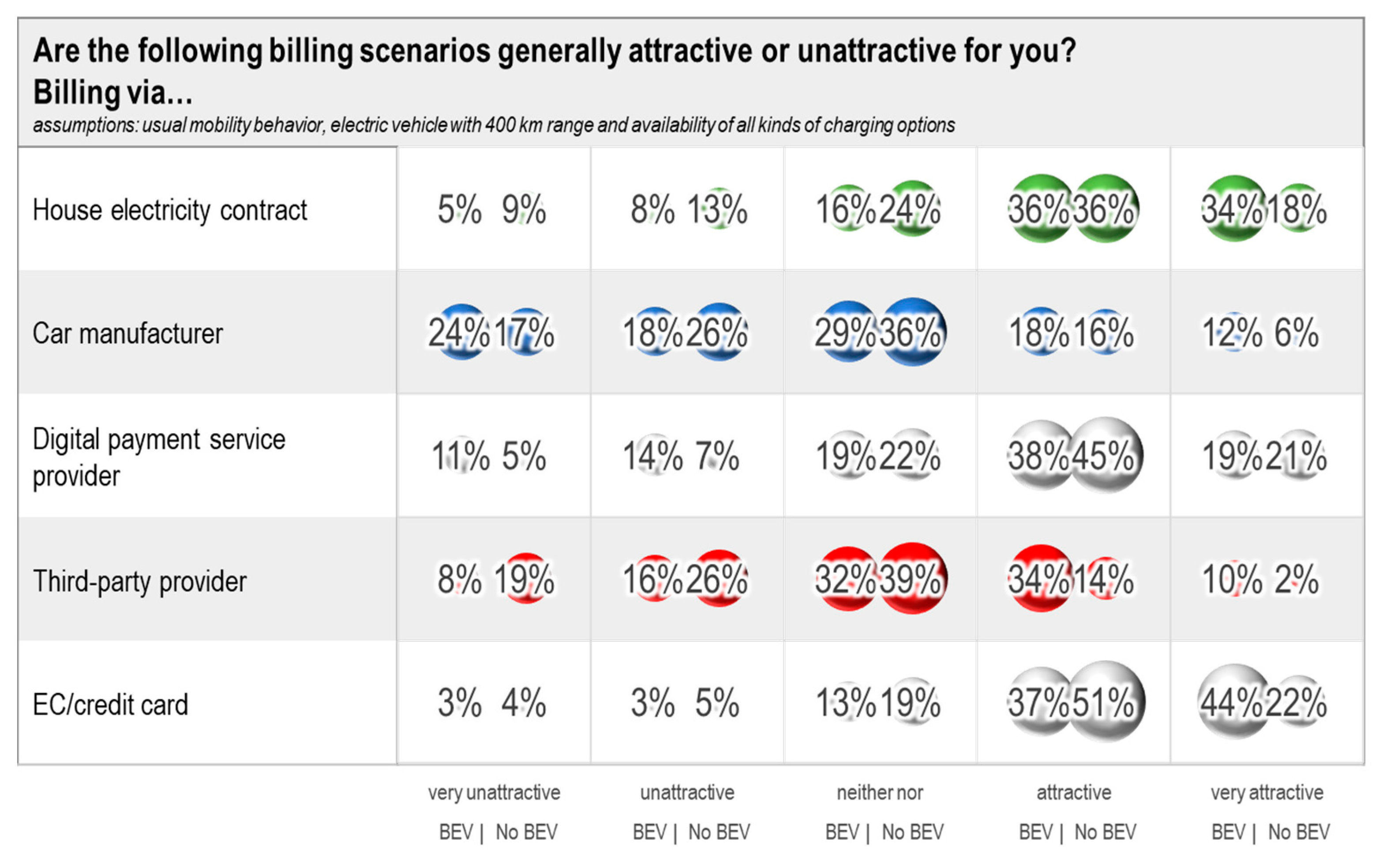

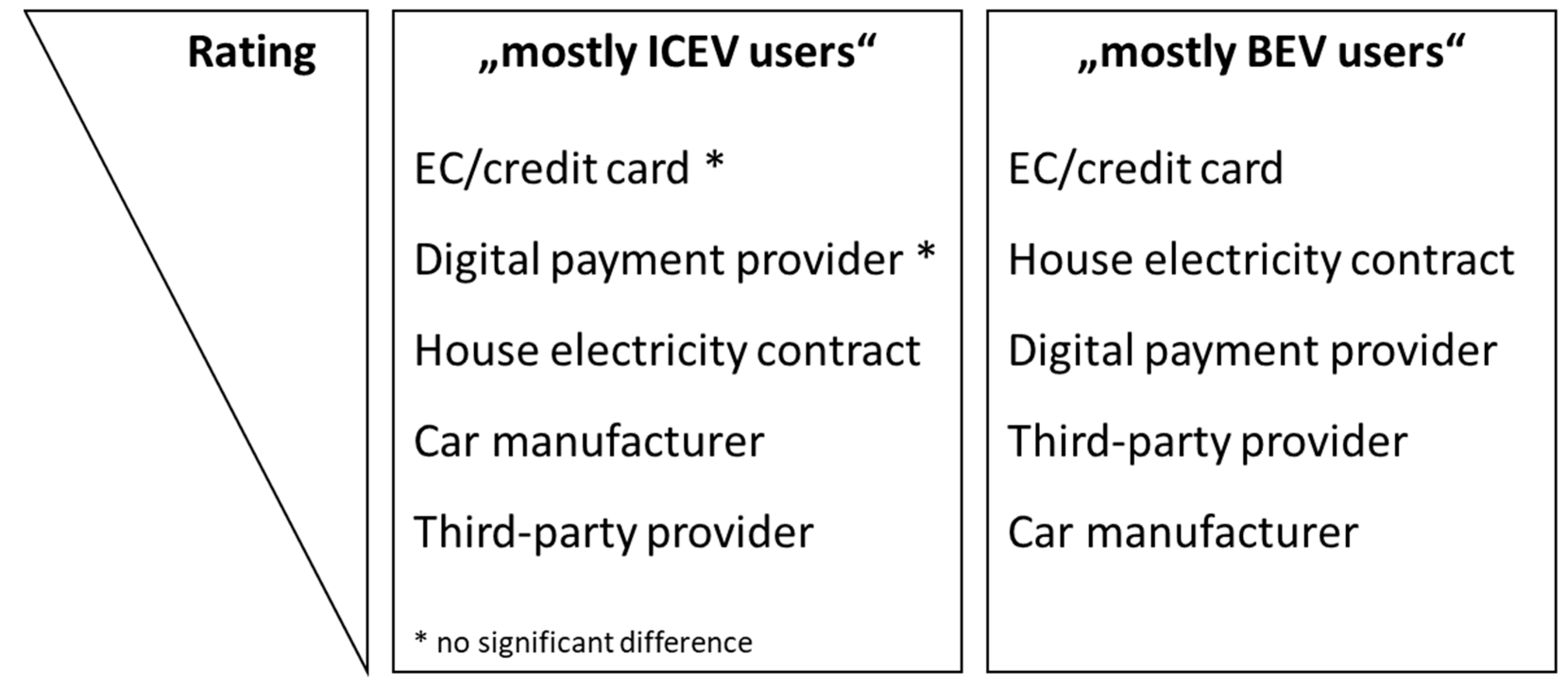

- Utility companies (EnBW, Maingau) leverage their existing customer base (and indirectly their brand image) and offer special rates for house electricity customers (10 ct cheaper per kWh). This step is well in line with user preferences. As shown in Figure 10, a majority of current and potential EV drivers consider this an attractive or very attractive option.

- New to the industry firms leverage their brand image to enter the market. Deutsche Telekom, originating from the telecommunications industry, has entered the market with an aggressive price policy in December 2018 [73]. This approach is easily comprehensible: The differentiation between EMSP apps is marginal and more importantly, switching costs are extremely low (=downloading and setting up another app). In this case, consumers are generally open to trying new service providers—even if the tariffs are similar. Telekom’s brand strength thus could explain the price difference to Maingau, another “discount EMSP” (29 ct vs. 25 ct).

- Selling below cost is not sustainable. Both Deutsche Telekom and Maingau have (at least partially) raised their prices in the past year [74,75]. As both companies only have a limited network of fast charging stations or no fast-charging stations at all (physical assets), their service provision heavily depends on (other) charge point operators. The price increase is an indicator that both “discount EMSP” have been selling below cost to gain market share.

- Sharp price distinctions reflect the power balance within the value network. Both Ionity and Deutsche Telekom vary their pricing scheme depending on which other players are involved in the interaction. Ionity is asking for a comparably high price but offers special rates to drivers that use the EMSP service provided by the carmakers that jointly own Ionity (e.g., Audi e-Tron Charging Service) [76]. It seems that Ionity is using its bargaining power provided by brand strength and huge existing customer base to overcome the limited interest of users in billing models that involve the car manufacturer (cf. Figure 10). Deutsche Telekom, in turn, is used to distinguish the charging prices depending on the charging infrastructure that is being used. Fast charging stations by EnBW, for instance, are being classified as “other charging stations” and priced at 89 ct per kWh—more than twice the price that is asked for “preferred charging stations” (39 ct per kWh) [74]. Most likely this is because EnBW, due to their power position (resulting from physical assets: approaching 1000 fast-charging locations), did not accept the prices that Deutsche Telekom asked for and/or because EnBW did not want to cannibalize their own EMSP service (offering fast charging at 39–49 ct per kWh).

- Power plays may result in a fragmented market. Ionity, as CPO, is asking a comparably high price if downstream services (EMSP) provided by non-affiliated companies are used. This policy has led to the situation that Ionity charging stations cannot be used with EnBW’s EMSP service anymore. A similar observation can be made for the charging stations of “Fastned”, which (as of February 2020) cannot be used with EMSP services by “EWE Go” [2].

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Emobly. Der Emobly Ladekarten-Kompass September 2019. Available online: https://emobly.com/de/laden/der-emobly-ladekarten-kompass-sept-2019/ (accessed on 4 March 2021).

- Emobly. Der Emobly Ladekarten-Kompass Februar 2021. Available online: https://emobly.com/de/news/der-emobly-ladekarten-kompass-februar-2021/ (accessed on 4 March 2021).

- Schroeder, A.; Traber, T. The economics of fast charging infrastructure for electric vehicles. Energy Policy 2012, 43, 136–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morrissey, P.; Weldon, P.; O’Mahony, M. Future standard and fast charging infrastructure planning: An analysis of EV charging behavior. Energy Policy 2016, 89, 257–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madina, C.; Zamora, I.; Zabala, E. Methodology for assessing EV charging infrastructure business models. Energy Policy 2016, 89, 284–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pagani, M.; Korosec, W.; Chokani, N.; Abhari, R.S. User behaviour and electric vehicle charging infrastructure: An agent-based model assessment. Appl. Energy 2019, 254, 113680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Röckle, F.; Marquardt, M.; Wichern, P. Fast-E: Study 1—Market Integration & Innovative Business Orientation; Allego GmbH: Berlin, Germany, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Costa, E.; Hufnagl, C.; Arndt, M.; Meier-Witty, B.; Mertens, A.; Wildburger, B.; Röckle, F. ultra-E: Study 1—Market and Business Models for Ultra Charging; Allego GmbH: Berlin, Germany, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Röckle, F.; Schmitt, G. Forschungsvorhaben zur Etablierung Eines Bundesweiten Schnellladenetzes für Achsen und Metropolen (SLAM): Verbund-Abschlussbericht; Universität Stuttgart: Stuttgart, Germany, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Röckle, F.; Litauer, R. Current and Potential Future EV Driver Charging Needs. In Proceedings of the 30th International Electric Vehicle Symposium (EVS 2017), Stuttgart, Germany, 9–11 October 2019; Red Hook: Curran, NY, USA, 2018; pp. 3445–3457. [Google Scholar]

- Röckle, F.; Weinmann, M.; Horn, D.; Schmidt, A. Integration of Roles vs. Specialization. In Proceedings of the 30th International Electric Vehicle Symposium (EVS 2017), Stuttgart, Germany, 9–11 October 2019; Red Hook: Curran, NY, USA, 2018; pp. 3431–3444. [Google Scholar]

- Bullinger, H.J.; Bauer, W.; Rüger, M. Geschäftsmodell-Innovationen Richtig Umsetzen. Vom Technologiemarkt zum Markterfolg; Fraunhofer-Institut für Arbeitswirtschaft und Organisation IAO: Stuttgart, Germany, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Stabell, C.B.; Fjeldstad, O.D. Configuring Value for Competitive Advantage: On Chains, Shops, and Networks. Strateg. Manag. J. 1998, 19, 413–437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grönroos, C.; Voima, P. Critical service logic: Making sense of value creation and co-creation. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 2013, 41, 133–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moore, J.F. Business ecosystems and the view from the firm. Antitrust Bull. 2006, 51, 31–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tukker, A. Eight types of product–service system: Eight ways to sustainability? Experiences from SusProNet. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2004, 13, 246–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McNaughton, R.B.; Osborne, P.; Imrie, B.C. Market-oriented value creation in service firms. Eur. J. Mark. 2002, 39, 990–1002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barney, J. Firm resources and sustained competitive advantage. J. Manag. 1991, 17, 99–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, H. Competitive advantage and firm performance. Compet. Rev. Int. Bus. J. 2000, 10, 15–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soh, C.; Markus, M.L. How IT creates business value: A process theory synthesis. In Proceedings of the ICIS 1995 Proceedings, Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 10–13 December 1995; Volume 4, pp. 29–41. [Google Scholar]

- Bharadwaj, A.; El Sawy, O.A.; Pavlou, P.A.; Venkatraman, N. Digital Business Strategy: Towards a Next Generation of Insights. Mis. Q. 2013, 37, 471–482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keen, P.; Williams, R. Value Architectures for Digital Business: Beyond the Business Model. Mis. Q. 2013, 37, 643–647. [Google Scholar]

- Malik, M.E.; Ghafoor, M.M.; Hafiz, K.I. Impact of Brand Image, Service Quality and price on customer satisfaction in Pakistan Telecommunication sector. Int. J. Bus. Soc. Sci. 2012, 3, 123–129. [Google Scholar]

- Davis, S. Brand Asset Management: How business can profit from the power of brand. J. Consum. Mark. 2002, 19, 351–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, H.H.; Liu, Y.M. The impact of brand equity on brand preference and purchase intentions in the service industries. Serv. Ind. J. 2009, 29, 1687–1706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bleeke, J.; Ernst, D. Is your strategic alliance really a sale? Harv. Bus. Rev. 1995, 73, 97–105. [Google Scholar]

- Nohria, N.; Garcia-Pont, C. Global strategic linkages and industry structure. Strateg. Manag. J. 1991, 12, 105–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burt, R.S. Structural Holes: The Social Structure of Competition; Harvard University Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Lorenzoni, G.; Baden-Fuller, C. Creating a strategic center to manage a web of partners. Calif. Manag. Rev. 1995, 37, 146–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pfeffer, J.; Salancik, G.R. The External Control of Organizations: A Resource Dependence Perspective; Stanford University Press: Stanford, CA, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Brandenburger, A.M.; Nalebuff, B.J. Co-Opetition; Doubleday: New York, NY, USA, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Ghemawat, P.; Collis, D.J.; Pisano, G.P.; Rivkin, J.W. Strategy and the Business Landscape: Text and Cases; Addison-Wesley: Reading, MA, USA, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Gomes-Casseres, B. Competitive advantage in alliance constellations. Strateg. Organ. 2003, 1, 327–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cattani, G.; Ferriani, S.A. core/periphery perspective of individual creative performance: Social networks and cinematic achievements in the Hollywood film industry. Organ. Sci. 2008, 29, 824–844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Human, S.; Provan, K.G. Legitimacy building in the evolution of small-firm multilateral networks: A comparative study of success and demise. Adm. Sci. Q. 2000, 45, 327–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chae, S.; Heidhues, P. Buyers’ alliances for bargaining power. J. Econ. Manag. Strategy 2004, 13, 731–754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mann, H. Seller Concentration, Barriers to Entry, and Rates of Return in Thirty Industries, 1950–1960. Rev. Econ. Stat. 1966, 48, 296–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Church, J.R.; Ware, R. Industrial Organization: A Strategic Approach; McGraw-Hill: New York, NY, USA, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- LaBarbera, P.A.; Mazursky, D.A. Longitudal assessment of consumer satisfaction/dissatisfaction: The dynamic aspect of the cognitive process. J. Mark. Res. 1983, 20, 393–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coldwell, J. Characteristics of a good customer satisfaction survey. In Customer Relationship Management: Emerging Concepts, Tools, and Applications; Tata McGraw-Hill Education: New Delhi, India, 2001; pp. 193–199. [Google Scholar]

- Hokanson, S. The deeper you analyze, the more you satisfy customers. Mark. News 1995, 29, 16. [Google Scholar]

- Homburg, C.; Rudolph, B. Customer Satisfaction in industrial markets: Dimensional and multiple role issues. J. Bus. Res. 2001, 52, 15–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woodall, T. Conceptualising ‘Value for the Customer’: An Attributional, Structural and Dispositional Analysis. Acad. Mark. Sci. Rev. 2003, 13, 1–42. [Google Scholar]

- Graf, A.; Maas, P. Customer value from a customer perspective: A comprehensive review. J. Betr. 2008, 58, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The Nielsen Company. Connecting with the Consumer. The Importance of Integrating Marketing Promises with Service Delivery. Available online: https://www.nielsen.com/wp-content/uploads/sites/3/2019/04/Nielsen_Connecting20with20the20Consumer.pdf (accessed on 10 April 2021).

- PricewaterhouseCoopers GmbH. Bevölkerungsbefragung Stromanbieter 2015. Available online: https://www.pwc.de/de/energiewirtschaft/assets/pwc-umfrage-energie.pdf (accessed on 10 April 2021).

- Bundeskartellamt. Sektoruntersuchung Kraftstoffe. Zwischenbericht gemäß § 32e GWB. Juni 2009. Available online: https://www.bundeskartellamt.de/SharedDocs/Publikation/DE/Sektoruntersuchungen/Sektoruntersuchung%20Kraftstoffe%20-%20Zwischenbericht.pdf;jsessionid=D5F7069F28D4674896BC4366B0D3F0E8.1_cid371?__blob=publicationFile&v=5 (accessed on 10 April 2021).

- Frondel, M.; Sommer, S. Schwindende Akzeptanz für die Energiewende? Ergebnisse einer wiederholten Bürgerbefragung. Z. Energ. 2018, 124, 27–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- GMK Markenberatung, Aktuelle Umfrage. Markenrelevanz in der Energiewirtschaft. Available online: https://www.gmk-markenberatung.de/files/inhalte/wissen/pdf_markenpublikationen/05-140904_gmk_umfrage_markenrelevanz_von_stromanbietern.pdf (accessed on 10 April 2021).

- Statista. Umfrage zur Attraktivität/Relevanz von Mobile Payment in Deutschland Nach Alter 2016. Available online: https://de.statista.com/statistik/daten/studie/568933/umfrage/umfrage-zur-attraktivitaet-relevanz-von-mobile-payment-nach-alter/ (accessed on 16 March 2021).

- Statista. Umfrage zur Nutzung von Mobile Payment in Deutschland Nach Alter 2016. Available online: https://de.statista.com/statistik/daten/studie/568411/umfrage/umfrage-zur-nutzung-von-mobile-payment-in-deutschland-nach-alter/ (accessed on 16 March 2021).

- Beutin, N.; Harmsen, M. Mobile Payment Report 2019. Available online: https://www.pwc.de/de/digitale-transformation/pwc-studie-mobile-payment-2019.pdf (accessed on 10 April 2021).

- ServiceValue GmbH. Studie VERTRAUENSRANKING 2020. Available online: https://servicevalue.de/app/uploads/2020/10/Studieninformation-Vertrauensranking-2020.pdf (accessed on 10 April 2021).

- EnBW. Unternehmensportrait. Available online: https://www.enbw.com/unternehmen/konzern/ueber-uns/unternehmensportrait/ (accessed on 16 March 2020).

- CHECK24. EnBW Energie. Available online: https://www.check24.de/strom-gas/enbw/ (accessed on 16 March 2020).

- VERIVOX. EnBW Energie Baden-Württemberg AG. Available online: https://www.verivox.de/power/carriers.aspx?id=3542 (accessed on 16 March 2020).

- Google Play. ENBW Mobility Elektroautos im Vergleich; GET CHARGE; EinfachStromLaden—MAINGAU; IONITY. Available online: https://play.google.com/store (accessed on 16 March 2020).

- GoingElectric. Ladekarten/Angebote für Ladesäulen. Available online: https://www.goingelectric.de/stromtankstellen/anbieter/ (accessed on 16 March 2020).

- EnBW. Ausbau Schnellladenetz. Available online: https://www.enbw.com/elektromobilitaet/ausbau-schnellladenetz (accessed on 16 March 2020).

- EnBW. EnBW Mobility + App. Available online: https://www.enbw.com/elektromobilitaet/produkte/mobilityplus-app/laden-und-bezahlen (accessed on 16 March 2020).

- Fuchs, A. Geschäftszahlen 2018—Deutsche Telekom Setzt Wachstumskurs im Rekordjahr fort und Übertrifft Finanzziele. Available online: https://www.telekom.com/de/medien/medieninformationen/detail/geschaeftszahlen-2018-563878 (accessed on 16 March 2020).

- CHECK24. Telekom: Bewertungen und Erfahrungen der CHECK24-Kunden. Available online: https://www.check24.de/dsl/kundenbewertung/telekom/ (accessed on 16 March 2020).

- Schaal, S. Telekom Errichtet 100. Schnellladestation. Available online: https://www.electrive.net/2019/12/16/telekom-errichtet-100-schnellladestation/ (accessed on 16 March 2020).

- MAINGAU Energie. ÜBER UNS. Available online: https://www.maingau-energie.de/unternehmen (accessed on 16 March 2020).

- CHECK24. MAINGAU Energie. Available online: https://www.check24.de/strom-gas/maingau-energie/ (accessed on 16 March 2020).

- VERIVOX. Erfahrungen Mit MAINGAU Energie GmbH. Available online: https://www.verivox.de/erfahrungen/maingau-energie-1-2968.aspx (accessed on 16 March 2020).

- MAINGAU Energie. EinfachStromLaden—Wir Bewegen Elektrofahrer. Available online: https://www.maingau-energie.de/e-mobilit%C3%A4t/Autostrom-Tarif (accessed on 16 March 2020).

- Kraftfahrtbundesamt. Pressemitteilung Nr. 07/2020—Fahrzeugzulassungen im Februar 2020. Available online: https://www.kba.de/DE/Presse/Pressemitteilungen/2020/Fahrzeugzulassungen/pm07_2020_n_02_20_pm_komplett.html?nn=2562684 (accessed on 16 March 2020).

- IONITY. ÜBER UNS. Available online: https://ionity.eu/de/about.html (accessed on 16 March 2020).

- IONITY. Status Tracker for IONITY HPC. Available online: https://ionity.ev-info.eu/statistics (accessed on 16 March 2020).

- IONTIY. IAA 2019: IONITY Stellt Neue High Power Charging Ladesäule vor und Begrüßt Neuen Shareholder Hyundai Motor Group. Available online: https://ionity.eu/_Resources/Persistent/9190b854b955c5de3bea1f4b6ae4241b07e132ac/20190910_IONITY-IAA-CHARGER-DE_f.pdf (accessed on 16 March 2020).

- Schaal, S. Wirbel um Ionity-Preise Geht Weiter. Available online: https://www.electrive.net/2020/01/28/wirbel-um-ionity-preise-geht-weiter/ (accessed on 16 March 2020).

- Werwitzke, C. Ladenetze: Telekom Steigt in den Preiskampf um Kunden ein. Available online: https://www.electrive.net/2018/12/03/ladenetze-telekom-steigt-in-preiskampf-um-kunden-ein/ (accessed on 16 March 2020).

- Bönnighausen, D. Deutsche Telekom Führt Abrechnung nach Kilowattstunde ein. Available online: https://www.electrive.net/2019/03/20/deutsche-telekom-fuehrt-abrechnung-nach-kilowattstunde-ein/ (accessed on 16 March 2020).

- Ecomento. “EinfachStromLaden”: Maingau Erhöht Preise, Angebot Soll Ausgebaut Warden. Available online: https://ecomento.de/2019/07/23/einfachstromladen-maingau-erhoeht-preise-35-cent-kwh/ (accessed on 16 March 2020).

- Schaal, S. Ionity Ändert Preismodell—Auf 79 Cent pro kWh. Available online: https://www.electrive.net/2020/01/16/ionity-aendert-preismodell-auf-79-cent-pro-kwh/ (accessed on 16 March 2020).

| Value-Added Perspective: What is the bargaining power of the firm within the group? The firm controls scarce, valued, and well-protected assets Competition among the firm’s suppliers of complements |

| Structural Perspective: What is the position of the firm within the network of allies? The firm participates in multiple constellations The firm occupies structural holes |

| Billing Via… | T | df | Sig. (2-Sided) | 95% Confidence Interval for the Difference | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lower | Upper | ||||

| House electricity contract * | −8.628 | 1076.824 | 0.000 | −0.715 | −0.450 |

| Car manufacturer | −0.760 | 926.012 | 0.447 | −0.198 | 0.087 |

| Digital payment provider * | 2.731 | 940.668 | 0.006 | 0.053 | 0.322 |

| Third-party provider * | −10.359 | 1149 | 0.000 | −0.770 | −0.524 |

| EC/credit card * | −7.373 | 1149 | 0.000 | −0.537 | −0.312 |

| df | F | Sig. | Partial Eta Squared | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Billing options “mostly ICEV users” * | 3.558 | 233.524 | 0.000 | 0.259 |

| Billing options “mostly BEV users” * | 3.879 | 141.923 | 0.000 | 0.228 |

| Mean Distance (I–J) | Billing Option I | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | ||

| Billing option J | 1 | n/a | −0.658 * | 0.332 * | −0.822 * | 0.417 * |

| 2 | 0.658 * | n/a | 0.990 * | −0.164 * | 1.075 * | |

| 3 | −0.332 * | −0.990 * | n/a | −1.154 * | 0.085 | |

| 4 | 0.822 * | 0.164 * | 1.154 * | n/a | 1.239 * | |

| 5 | −0.417 * | −1.075 * | −0.085 | −1.239 * | n/a | |

| Mean Distance (I–J) | Billing Option I | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | ||

| Billing option J | 1 | n/a | −1.185 * | −0.438 * | −0.757 * | 0.259 * |

| 2 | 1.185 * | n/a | 0.747 * | 0.427 * | 1.444 * | |

| 3 | 0.438 * | −0.747 * | n/a | −0.320 * | 0.697 * | |

| 4 | 0.757 * | −0.427 * | 0.320 * | n/a | 1.017 * | |

| 5 | −0.259 * | −1.444 * | −0.697 * | −1.017 * | n/a | |

| Brand image | ++ | 5.5 million customers (electricity, gas, and water); 4.3/5 stars rating on check 24 and customer loyalty rating of 80% on Verivox (online consumer portals) |

| Digital assets | +++ | Charging app with ≥100,000 downloads and 4.7/5 stars rating; access to 47,000 charge points |

| Physicalassets | +++ | 1000 fast-charging locations (target for year-end 2020) |

| Pricing (fast charging) | €€€ €€ €€ | 49 ct/kWh for general customers 39 ct/kWh for intensive users that pay a monthly fee of 5€ 39 ct/kWh for customers that also have a house electricity contract |

| Brand image | +++ | ≥43 million customers (mobile, landline, and TV); 4/5 stars rating on check 24 (online consumer portal); survey: 27% of survey sample (47% of people aged 18–27) could imagine having Deutsche Telekom as their energy provider |

| Digital assets | ++ | Charging app with ≥10,000 downloads and 2/5 stars rating; access to 32,000 charge points (Telekom GetCharge) |

| Physical assets | + | ≥100 fast-charging stations (Telekom Comfort Charge) |

| Pricing (fast charging) | €€ €€€€ | 39 ct/kWh at “privileged” charging stations (including own stations) 89 ct/kWh at “other” charging stations (including e.g., stations of EnBW) |

| Brand image | ++ | 300,000 customers (electricity and gas); 4.2/5 stars rating on check 24 and customer loyalty rating of 88% on Verivox (online consumer portals) |

| Digital assets | + | Charging app with ≥10,000 downloads and 2.9/5 stars rating; access to 45,000 charge points |

| Physical assets | - | None own fast-charging stations |

| Pricing (fast charging) | €€ € | 35 ct/kWh for general customers 25 ct/kWh for customers that also have a house electricity contract |

| Brand image | +++ | Market share of about 55% of newly registered vehicles in Germany (as of 02/2020—makes: Audi, BMW, Mercedes, Ford, Seat, Volkswagen) |

| Digital assets | + | Charging app with ≥10,000 downloads and 1.7/5 stars rating; access to 1000 charge points |

| Physical assets | ++ | 219 fast-charging locations (as of 03/2020, target for year-end 2020 is 400) |

| Pricing (fast charging) | €€€€ € | 79 ct/kWh for general customers 29 ct/kWh for customers of BMW, Daimler, Ford, Volkswagen |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Röckle, F.; Schulz, T. Leveraging User Preferences to Develop Profitable Business Models for Electric Vehicle Charging. World Electr. Veh. J. 2021, 12, 60. https://doi.org/10.3390/wevj12020060

Röckle F, Schulz T. Leveraging User Preferences to Develop Profitable Business Models for Electric Vehicle Charging. World Electric Vehicle Journal. 2021; 12(2):60. https://doi.org/10.3390/wevj12020060

Chicago/Turabian StyleRöckle, Felix, and Thimo Schulz. 2021. "Leveraging User Preferences to Develop Profitable Business Models for Electric Vehicle Charging" World Electric Vehicle Journal 12, no. 2: 60. https://doi.org/10.3390/wevj12020060

APA StyleRöckle, F., & Schulz, T. (2021). Leveraging User Preferences to Develop Profitable Business Models for Electric Vehicle Charging. World Electric Vehicle Journal, 12(2), 60. https://doi.org/10.3390/wevj12020060