Abstract

This paper investigates how users of smart devices attribute agency both to themselves and to their devices. Statistical analyses, tag cloud analysis, and sentiment analysis were applied on survey data collected from 587 participants. As a result of a preliminary factorial analysis, two independent constructs of agency emerged: (i) user agency and (ii) device agency. These two constructs received further support from a sentiment analysis and a tag cloud analysis conducted on the written responses provided in a survey. We also studied how user agency and device agency relate to various background variables, such as the user’s professional knowledge of smart devices. We present a new preliminary model, where the two agency constructs are used to conceptualize agency in human–smart device relationships in a matrix composed of a controller, collaborator, detached, and victim. Our model with the constructs of user agency and device agency fosters a richer understanding of the users’ experiences in their interactions with devices. The results could facilitate designing interfaces that better take into account the users’ views of their own capabilities as well as the capacities of their devices; the findings can assist in tackling challenges such as the feeling of lacking agency experienced by technologically savvy users.

1. Introduction

As smart devices continue their march into every corner of our personal lives, it is increasingly important to understand our interactions with these objects from a perspective that acknowledges the agency of both the user and the device (e.g., [1]). The fact that smart devices have characteristics that by far exceed those of other, “non-smart” objects, calls for a more nuanced understanding of how users perceive the varied capacities of these objects as well as the capacities of themselves to use these artifacts. In this paper, we advance this understanding by elaborating on the notion of agency. Our aim is to conceptualize the relationship that humans have with their devices as consisting of the attributions of abilities and capacities that the user assigns to themselves as well as to their device.

We will present how two aspects of this interaction are important:

- User agency, the self-perceived abilities to use a device.

- Device agency, the capacities the user attributes to a device.

Agency is a notion that has made a variety of appearances in several different disciplines over the past few decades. In psychology, the common term is sense of agency, which refers to the feeling that one is in control of one’s actions and their consequences; when people take action, they tend to feel that they are in charge of the action and not that the action happens to them [2]. In Human–Computer Interaction, the term of agency has been used for a long time, but it has often been reduced to denote people’s feeling of being in control of a device [3,4]. A more detailed understanding of the user’s perception of their agency and of the agency they are willing to see ascribed to their device can improve our understanding of the challenges that different users might have in adopting different devices. Consequently, an understanding of user–device relationships as emerging from agency attributions also supports more tailored interface developments.

When developing the concepts of user and device agency, we revisit Gibson and his notion of affordances [5]. Whereas the popular notion of affordances by Norman defines them as the actual and perceived designed-in characteristics of an object [6], especially such characteristics that define how the object can be used, the notion of agency as adopted in this paper underlines the user’s perceptions of what they and their device can and cannot do. Our notion of device agency is, naturally and to some degree, overlapping with the perceived affordances of the device, but it also includes more of other aspects of the device’s action capacities and tendencies compared to those related to how to use it or what to do with it. We do not tie our thinking of device and user agency with any designed-in characteristics of the object but stay at the level of what the users think about their devices. Since under the notion of affordances there has not been much nuanced discussion of what the users actually believe about themselves as being able to (or not being able to) do with their devices, we broadened the discussion to this direction. The notion of agency shifts the focus away from the potential uses of a device to what the users actually perceive themselves and their gadgets as able to do.

We do not claim to be investigating agency as it actually manifests in people’s actions with their smart device. Instead, we are focusing on exploring and developing the notion of agency by looking at people’s perceived sense of agency as well as their perceived device agency.

This study has been approved by the Ethics Committee of Tilburg University (TiSEM Institution Review Board or IRB for short) under the Standard Research Protocol SRP-2 and has been conducted in accordance with the Netherlands Code of Conduct for Research Integrity (VSNU, 2018). The approval code is IRB EXE 2020-007. The rest of the paper is structured as follows. First, we will take a look at previous conversations around affordances and then proceed to a broader literature review about the various definitions of and approaches to agency in HCI and IS. In the next section, we will explain our conceptualization of user–device relationships, show how we developed the agency survey, and discuss our data collection and the sample. We proceed to present the results of all of our analyses. Finally, in the discussion section, we reflect on the findings and their practical implications for, e.g., interface development in HCI.

1.1. The Role of Agency in Human–Technology Interactions: The Perspective of Affordances

To understand agency in the context of theorizing and research that has been important in the history of Human–Computer Interaction and Information Systems, we need to look at the notion of affordances. Traditionally, affordance is the possibility for an action provided by the environment for an actor; thus, affordances are directly perceivable, since all the information necessary to guide behavior is available in the environment, not hidden in mental processes [5]. Affordances do not depend on humans; even if an individual’s changing needs might influence whether the affordance is perceived or not, it is never imposed upon the environment by the observer—it is already there [5]. In alignment with this, Norman [5] defined affordances as the actual and perceived designed-in characteristics of an object, in particular, basic ones that define how said object can be used.

Later, the concept of affordances was brought into the sociology of science and technology. The opposite poles of constructivism (technology as a tabula rasa to which people can ascribe any meaning they want to), and determinism (the power of technology to make people act in a certain way) were brought closer together [7]. Whereas Gibson’s tradition sees affordances as embedded in the object’s design and thus, existing independently of the users, Huthcby sees affordances as emerging from the relationship between a goal-oriented user and the object over time. The latter approach underlines the fact that affordances can be facilitated through design, but affordances may or may not emerge in action [8]. In the original Gibsonian view, a goal-directed actor is perceiving an object in terms of how it can be used, and the focus is on what the potential actions afforded are intended to accomplish [9]. Lately, affordances have been viewed as existing within the relationship between the user and the object and emerging from a combination of the user’s characteristics and those of the object, reflecting possible actions on the artifact itself [7,10,11]. Thus, an object does not have any affordances except in relation to a user that has goals [9], but at the same time, the object’s affordances exist independently of the situational needs of the user [12].

In alignment with the notion of affordances, we acknowledge that technology is not only what the users make of it. In addition, we appreciate how the notion of affordances directs attention to the ways that technology both constrains and enables people’s actions. A technological device has some material functionality but needs to be recognized as a social object, because the possibilities of action depend on the goal-directed user who is enacting them [9,13]. However, we do not focus on the qualities of technology offering action possibilities, nor on such qualities that are directly perceivable by the user. We are also not exploring the potential for action in particular user–object dyads. Thus, the ascriptions of agency as framed in this paper are not meant to reflect the action potentials of a device emerging in user–device dyads. The users’ agency attributions to their devices are not the same as the possibilities of action offered to them by the technological device. Moreover, whereas affordances are just action potentials that need to be executed by an actor to achieve a goal [9], our notions of user and device agency also capture notions of actions already executed and goals achieved or not achieved with the device, thus grounding our notion on a different timescale that also reflects accumulated experiences with a certain device. Importantly, device agency also includes notions of what the device can and cannot do independently of the user vs. only actions commanded by the user.

1.2. A Further Look at Agency in the Literature of Information Systems (IS) and Human–Computer Interaction (HCI)

Agency is often defined, both in HCI and IS, as a human subject’s intentional influence on the outside world [12,14,15,16]. In terms of agency, studies on humans’ interactions with technology have created a lively debate around two opposing poles. On one hand, human users are viewed as free to exercise their mastery and control over technology, and on the other hand, technology is depicted as having the fundamental capacity to restrict and constrain human agency [17]. Previous work in IS have often treated the artifact as merely a passive tool that could not initiate action; however, the new generation of IS objects requires challenging this underlying assumption of the primacy of human agency, as these new artifacts are not passively waiting to be used, or subordinate to human control [1].

The current main trend in the theory and research on human interaction with technology reflects the balancing of these opposing arguments. Technology is seen as both enabling and constraining human action as it is enacted in interactions between humans and devices [7,17,18,19,20]. There is increasing agreement that humans and technology are both agentic, but their agency is fundamentally of a different quality [16,21]. Both the capacities of the user and those of technology are important in task performance, and often compensate for each other [22].

Human agency has often been conceptualized as including two different dimensions. On the one hand, human agency (1) concerns the ability to act and cause an effect intentionally in the world, and on the other hand, (2) it denotes self-awareness and the ability to conduct reflective evaluations [12,16,18,19,21]. It has been customary to argue that only humans are able to initiate actions intentionally and adopt a reflective/reflexive perspective in relation to themselves, their actions, and things and phenomena of the outside world, while claiming that technology does not possess such capabilities [12,16,18,19,21]. To give an example of theorizing about human agency in relationship with technology, authors in [23] proposed a temporally situated self-agency theory to capture how users reshape information technologies to achieve their goals; in this process, agency emerges as relational, technology-oriented, and future-directed, as purposeful and future-oriented user-actors make and pursue new goals. Outside such dimensions of intentional action and reflective action resides mere behavior that can be explained by material cause and effect and that is attributable to both technology and humans [19].

In the previous IS literature, agency has remained predominantly a theoretical concept. There are literature reviews [2,16,16,19] and theoretical frameworks [1,15,20,23], but very few attempts to clearly operationalize agency in the context of user–technology interactions. To give a recent example of a theoretically informed agency definition that is very close to the common conceptualization of agency as a feeling of control over actions [2], agency has been framed as the user’s inherent capacity to form goals and intentionally take action to achieve those goals [23]. Studies on human–IT interactions have also adopted other concepts close to agency such as self-regulation and self-efficacy [11,23,24]. Authors in [11] showed how the user’s self-regulation and self-control, denoting the user’s ability to adapt their behaviors and responses to IT, are central in managing technostress.

As stated before, in the field of HCI, agency often becomes identical with the user’s feeling of control, that is, the perception that they are the one initiating their actions and causing something to happen in their interactions with technology [3,25,26,27,28,29]. Along these lines, most of the experimental approaches to agency in the field of HCI represent the intentional binding tradition. Intentional binding can be understood as a psychophysiological measure of an implicit aspect of agency, more specifically, people’s perceptions of the time between the initiation of an action and its effects [3,27,28].

When exploring humans’ relations with technology, we need to take into account both the user’s sense of agency and the degree and kind of agency that they are willing to perceive their technology as having [3]. Earlier research included some explorations on the kinds of relationships users develop with technology that are interesting to our discussion on agency. Mick and Fournier in [30] listed paradoxes related to technology, such as control/chaos and freedom/enslavement: while technology is often positioned to facilitate control and freedom, it can also feed the conditions of upheaval and dependency. Users adopt either a partnering strategy of committed interdependence or a mastering strategy of commanding the object completely to solve the paradoxes [30]. Social psychology, affective computing, and perceptual motor research indicates that people attribute human-like agentic capacities to interactive systems that are sufficiently complex [27,28]. Using the circumplex model of interpersonal complementarity, Novak and Hoffman in [20] presented a model of relationship dynamics between consumers and objects, dividing these into master–servant relationships, partner relationships, and unstable relationships. In another study, three different patterns of users with voice controlled smart assistants (VCSA) were found: a servant–master relationship (the VCSA being the servant), or vice versa, servant–master (the VCSA is the master), and a third group where the relationship was described as one between partners [31]. It was argued that increased interactions are more likely to occur when the users feel that they are the master of their device [31]. Carter and Grover in [24] have pointed out that users incorporate new capacities afforded by the IT as their personal resources; a strong sense of IT being integral to one’s sense of self impacts feature use and enhances user behaviors. ITs that have attributes such as malleability, mobility, and high functionality impact computer self-efficacy, which in turn feeds back to the user’s IT identity [24]. A recent IS delegation model describes the transfer of responsibilities and rights to and from humans in interactions with IS artifacts, where both the human and the object are endowed with resources and capabilities [1].

The earlier literature has also taken steps in defining the kind of agency that technology has. Smart objects have object experience and information possessing and filtering activities that the device carries out independently of the user. Inthis sense, the objects have primary agency, the ability to initiate and bring about actions independently [31]. Most recently, Baird and Maruping in [1] suggested the categorization of IS artifacts into four classes of agency, running from reflexive artifacts with sensing and reacting capacities to prescriptive ones that can substitute human decision making.

In Human–Machine networks, the agency of any actor, machine or human, has been defined as the capacity to execute activities in a specific environment in terms of a set of objectives influencing how these actors participate in the networks [18]. Machines have agency in terms of how much they perform creative and personal actions, influence other actors in Human–Machine networks, enable humans to have proxy agency (utilize the resources of other agents to have them act on their behalf), and of how much humans perceive them as possessing agency of their own [18].

The exploration of agency attributions to technology is important, since a key challenge for the whole HCI community continues to be how to develop technology and interfaces that sustain and support the human user’s sense of agency in their interactions with the system [2,3,25,32]. We cannot really understand the user’s sense of agency in isolation from their perceptions of the agency of devices. Smart objects, with their increasing autonomy and other smart capacities, continuously challenge the users’ views on the agency of technology and invite them to create a more dynamic and multisided understanding of agency in human–smart device interactions [20]. Classical conceptualizations of ideal human–technology relationships maintain that the user must sustain their sense of control over technology that they experience as responding to their actions [2,32]. Such views do not seem equipped to map the complexity of different variations of agency that come into play as humans relate to and interact with their smart devices. This paper aims to fill this theoretical and empirical gap.

Table 1 summarizes important earlier work on agency. We can distinguish the following focuses: (i) humans, (ii) technology, and (iii) interaction.

Table 1.

Agency and the specific focus of seminal papers.

We take the stance that the previous definitions of human agency vs. the agency of technology need to be revised and expanded beyond the simple notion of control and by taking into account human and smart device agency simultaneously. Moreover, in addition to mere theorizing, agency needs to be operationalized. To our knowledge, there does not exist yet a survey scale to assess agency in human–smart device interactions. In this study, we expanded our literature review to construct a survey to explore users’ perceptions of their agency and the agency they attribute to their device.

We acknowledge that our decision to focus on smart devices instead of applications is not unproblematic. However, smart devices comprise a varied group of different kinds of personal gadgets, the use of which is not dominated by applications in the same way as is the case with computers, tablets, and smart phones. Moreover, we argue that users still interact with devices as coherent, singular objects that warrant their treatment as entities in human–device interactions. Smart devices should not be approached as channels of message transferring or human interaction but as participants in communicative exchanges; in fact, a smart device is not a communication medium but a communication “other” [36].

The main research questions of this study are as follows. (1) Is it possible to conceptualize the relationship people have with their smart devices, developing and operationalizing the concepts of user agency and device agency? (2) What is the most appropriate way of defining agency in a survey format? (3) Do user variables such as age, sex, and educational and professional background influence the levels of user and device agency?

We answered these questions by collecting survey responses from 587 respondents and analyzing them statistically. The aim of the study was not developing and confirming a model or theory, but taking preliminary empirical steps in understanding whether conceptualizing user agency and device agency as complementary and separate notions would make theoretical and empirical sense. In the following sections, we will explain our literature-driven preliminary theorizing on user and device agency as well as the process of the building of the survey. We will explain our multiple analyses on the survey data and display our results. Finally, we will discuss the findings and their implications for studying human–technology interactions.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Toward Developing a Scale for Agency in Human and Smart Device Relationships

In this paper, we propose a preliminary conceptualization of agency in human–smart device interactions comprising both user agency and device agency. User agency is here conceptualized as a dimension, where at the one end is low agency—a feeling of not mastering one’s device optimally—and at the other end is high agency—a sense of mastery of one’s device. In a similar manner, device agency is a dimension that evolves from low agency—the device does not have the capacities to do things that are meaningful for the user’s goals—to high agency—the device has its own relevant action capacities that can help the user to reach their goals. We will later explicate the literature behind our conceptualizations, and for a quick reference, the reader is advised to look at Table 2.

Table 2.

The survey items related to user and device agency constructions, their definitions, and references to their theoretical background.

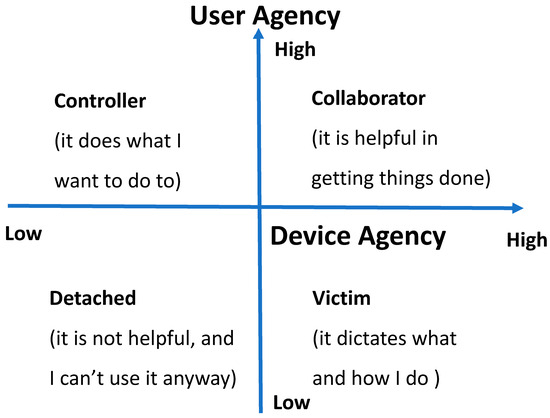

We propose that the dimensions of user agency and device agency are independent. This means that a person can be simultaneously high in both or, likewise, low in both these dimensions. In this way, we obtain a matrix of four different ways the user can relate to their device (Figure 1). These user–device dynamics have been named controller, collaborator, detached, and victim.

Figure 1.

A collaborator regards their device as useful and helpful, thus attributing agency to it. Simultaneously, they attribute agency to oneself, viewing themself as capable of using the device in a meaningful manner. A victim attributes low agency to themselves but high agency to the device. This kind of user sees the device as able to do things and themselves as not able to use it in a way that they perceive as optimal. A detached user scores low both in self-perceived user agency and in device agency. This is a user that perceives themselves as unable with the smart device, and also perceives the device as not helpful or useful.

In our theoretical model, a controller is a user who attributes agency to themselves but less to the device. A controller sees oneself as a capable user and the device either as not having any independent capabilities outside the user’s control or as completely unable to do things.

2.2. On Developing the Agency Survey

The survey developed in this study aimed to further define the concepts of user and device agency in human–smart device interactions. It is exploratory and preliminary in nature; we aimed to understand if the relationships that people develop with their smart devices can be effectively conceptualized using these two notions.

Based on an extensive literature review on agency, efficacy, and related notions within the fields of HCI in particular and IS in general, we formulated 16 survey items concerning the agency of both the user and the device. The final survey included four items designed to capture high user agency, four on low user agency, four on high device agency and four on low device agency. The survey thus included eight items of user agency and eight of device agency. In Table 2, we show the underlying construct and the sources that suggested each survey item.

In addition to the dimensions of user agency and device agency measured as explained in Table 2, the survey included scales developed for other constructs used both within HCI and other fields to describe how people interact with technology:

- The functionality or usability of the device [39,40,41].

- Price utility: the perceived good use of money when purchasing the device [42].

- Self-extension [39,43].

- The social aspect, such as using the device to express social status or to enhance social relationships [39,41,42]

- The emotional dimension [39,41].

- Attributing human-like qualities to the device, anthropomorphism [20,38].

All constructs were measured with multi-item scales designed specifically for the purposes of this study. The survey also included a set of questions for describing the sample (the respondents’ sex, age, educational background, etc.).

2.3. Data Collection

The survey used in this study was actively shared by the authors on different social media (Facebook, Twitter, Reddit, LinkedIn) as well as mailing lists of technology professionals. The people reached were encouraged to further share the survey in their social media or other channels. In the data collection, we used an anonymous Qualtrics format. The data were stored at a Tilburg University data repository according to the GDPR protocol. The data are be available for the scientific community for the next 10 years [43].

In the final part of the survey, we asked the participants to describe their relationship with their smart device in the form of a few open questions. This part of the survey was analyzed with sentiment analysis and tag cloud techniques in order to investigate the validity of our proposed conceptualization of human and smart device agency with other alternative methods compared to that of a statistical analysis. In the last part of the survey, we inquired whether the participants would be interested in an interview about their smart device use, with the aim of performing a second iteration of this preliminary study.

For the purposes of this research, we originally obtained data from 809 participants. The removal of all incomplete surveys, that is, surveys where the respondent had not answered all questions, left a dataset of 587 surveys.

The respondents came from 70 different countries from all continents and resided in 75 different countries. As is evident from Table 3, the obtained sample is skewed toward highly educated professionals and people very knowledgeable of technology. This constitution of the sample naturally places a constraint on the generalizability of the results. However, it also provides a unique window into the agency of a very particular user group.

Table 3.

The survey respondents.

In the beginning of the survey, the respondents were asked to pick one personal smart device that they use and keep it in mind when responding to the questions. Only if the respondent indicated not owning an actual smart device, then they were encouraged to take the survey while thinking about their mobile phone or computer.

3. Results

We first present the results of our statistical analyses. Next, we move on to those of the tag cloud analysis and finally present the sentiment analysis results.

3.1. Exploratory Factorial Analysis

With the exploratory factorial analysis, we aimed at investigating the emergence and patterning of the constructs previously specified. We were especially interested in whether and how the constructs of user agency and device agency would emerge from the data. The preliminary statistical analyses showed that the data is non-normal, but conducting exploratory factorial analysis is valid in these circumstances, because we are not testing a theory (merely exploring whether certain conceptualizations of agency make sense) or aiming to generalize the results beyond this specific sample [44].

When designing the survey, our intention was to create a new measure to explore a variety of nuances of agency. As we did not aim to artificially heighten Cronbach’s alpha by building in some redundancy to the scale, that is, repeating the same question in different versions [45], a low Cronbach’s alpha is to be expected. Indeed, not unexpectedly, the Cronbach alphas were only 0.44 for device agency and 0.62 for user agency. As the low alphas might raise some discussion, we would like to note that the Cronbach alpha has been a widely discussed measure with a lot of disagreement on the appropriate acceptability range. Many scholars have warned against using any automatic cutoff criteria, suggesting that researchers should not draw conclusions on scale adequacy based only on Cronbach’s alpha, because the purpose and stage of the research as well as the decisions that are supposed to be made using the scale all influence what is adequate reliability [46].

We conducted a Principal Axis Factor analysis with oblique rotation (Promax) on all 35 agency-related questions in the survey. The Kaiser–Meyer–Olkin measure (KMO = 0.84) verified the sampling adequacy for the analysis. All except six of the KMO values for individual items were greater than 0.5. Since the six items were not included in the agency factors that emerged in the factorial analysis, they were not part of the further statistical analyses, and hence, their low KMO did not present a problem.

Eight of the factors that emerged in the exploratory factorial analysis had eigenvalues larger than Kaiser’s criterion of 1. In combination, these eight factors explained 54.89% of the total variance. The scree plot was rather ambiguous, containing inflexions that justified retaining two, four, six, or eight factors. Six of the factors made theoretical sense and were named user agency, device agency, self-extension, functionality, anthropomorphism, and feelings.

We conducted a second exploratory factorial analysis focusing on the 16 survey questions concerning only agency. A Principal Axis Factor analysis was conducted with oblique rotation (Promax), extracting two factors (user agency and device agency). The KMO of 0.78 confirmed the adequacy of the sampling. As expected, two factors emerged: user agency and device agency. They had eigenvalues of 2.07 and 3.34, respectively, and together, they explained 33.81% of the variance. The goal was to obtain a simple factorial structure [47], where each factor had only a few high loadings and the rest of them were (close to) zero. We removed variables that had no loadings on either factor or had low loadings, as well as variables that cross-loaded on both factors. One variable at a time was deleted. The KMO was 0.7. The resulting two factors are shown in Table 4.

Table 4.

Results of the factorial analysis.

The variables included in these two factors had significant loadings on both factors, had no cross-loadings, and the scales had good internal consistency. Moreover, when selecting the final items to be included in the factors, we took into account the fact that when the sample size is greater than 100, factor loadings of 0.30 and higher can be considered significant [47].

These new constructs had Cronbach’s alphas of 0.66 (device agency) and 0.62 (user agency). According to [48], values of 0.6–0.7 are acceptable Cronbach alphas, especially in an exploratory study where a new scale is being tested. In addition, these agency constructs have a close-to-zero correlation with each other and have eigenvalues of 1.82 and 2.1. These two constructs account for 49% of the variance in the sample.

The factors of user agency and device agency consist of items belonging to the original agency and device agency survey scales. In Table 5, we present Pearson’s correlations of all of the agency items of the survey and of the constructs of user and device agency.

Table 5.

The Pearson correlations.

The table shows that items Q1, Q5, Q9, and Q13 are all negatively correlated with user agency. Items Q2, Q6, Q10, and Q14 are all positively correlated with user agency. At the same time, Q3, Q8, and Q11 are all negatively correlated with device agency, and item Q15 has a practically zero correlation. Finally, Q4, Q7, and Q12 are all positively correlated with device agency, while item Q16 has a zero correlation with it. This is in line with how we outlined the notions of high user agency, low user agency, high device agency, and low device agency (see Figure 1 and Table 2).

Items Q4, Q5, Q12, and Q7 had the highest correlations with device agency, while items Q6, Q10, Q14, and Q16 correlated highly with user agency. Items Q1, Q8, Q9, Q11, and Q15 had low correlations, pointing to the possibility that they measured aspects of relationship with devices that are not relevant in terms of agency and possibly measure a different dimension. These items measured either such aspects of user experience that are not directly related to the experience of using the device meaningfully (positive feelings, understanding how the device works) or highlight the device as having an independent intelligence and interaction capacity or an ability to outperform the human. It is possible that the high-device-agency items Q8, Q11, and Q15 over-anthropomorphized the device and represent such cognitive and interactional skills that the respondents were not willing to attribute to a smart device.

3.2. Tag Cloud Analysis

To conduct this analysis, we used the responses to the optional open question at the end of the survey where we asked the respondents to freely share their opinion regarding the relationship that they experienced with their smart device of choice. Our aim was to understand if users that were classified into different categories of device and user agency had a different way to describe their experiences with their device. In other words, if these constructs are irrelevant, we would expect no differences between the aggregate conversations of two different categories.

We grouped the respondents according to high and low user and device agency in the fourfold matrix of user–device agency (Figure 1). We then extracted the relevant keywords of the comments using a technique called bag of words where we analyzed the most relevant keyword in the text. The text had a pre-elaboration process consisting of two phases:

- Phase 1: the removal of punctuation and stop words;

- Phase 2: the removal of secondary stop words with the help of a domain expert.

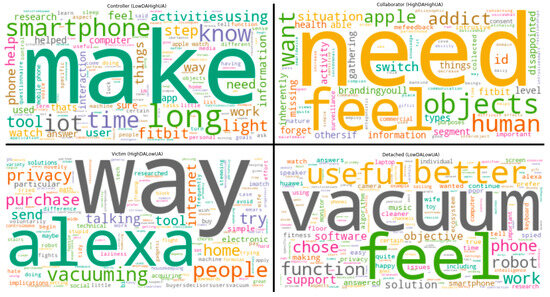

The results are shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Tag Cloud Analysis.

For each category, we can observe the most relevant keywords and their size reflecting the frequency of the words themselves. We can note the following:

- In the box of the controller (upper left), we see, firstly, a plethora of action verbs pop up, verbs such as make, work, need, know, watch, and learn, and, secondly, nouns such as tool, interaction, goals, user, time, sense, and function. There is a striking absence of any negative words. The words give an impression of function orientation and activity, which seem to fit with the profile of the controller as someone who attributes high agency to themselves while keeping their device as just a tool with low levels of independent agency.

- The box of the collaborator (upper right) has emphasis on communication- and interaction-oriented words, for example, need, feel, objects, human, situation, want, gathering, intrusive, missing, communication, helps, effects, disappointed, feedback, addict, and consent. This tag cloud segment seems to implicate a more personal relationship with the device and, notably, lacks the action and tool-oriented impression provided by the controller segment.

- In the segment of the victim (lower left), the words “Alexa” and “way” pop out first; however, further exploration reveals that the box contains many negatively loaded words: hate, error, try, stupid, avoid, yelling, and laziness. In the victim’s polar opposite segment, that of the controller, such negative expressions are absent, and the words related to actively performing an action that characterize the controller are not seen in this segment.

- In the detached segment (lower right), we see a multitude of nouns referring to the actual device the people are talking about, such as vacuum, keyboard, phone, function, solution, robot, and camera. Hence, the most important keywords are just about the technology and not about the actions and feelings of the user in interaction with the device, unlike in the tag clouds of the other three interaction styles. In this segment, some verbs, such as “feel”, have a negative in front of them in the original data (“do not feel”).

Consequently, we can conclude that this analysis provides preliminary support to the idea of conceptualizing the relationship that users have with their devices as composed of two components: device agency and user agency.

3.3. Sentiment Analysis

We used the data provided by the open question of the survey for conducting a sentiment analysis. We calculated the aggregate polarity and aggregate subjectivity of each group:

- Polarity refers to the strength of opinion that a person has in relation to the subject that is being described. It ranges between −1 (negative opinion) and +1 (positive opinion);

- Subjectivity refers to the degree to which a person is involved with the device and measures the degree to which the experience is described using facts versus personal stories. It ranges between 0 (factual conversation) and +1 (personal opinion).

As we are analyzing the aggregate sentiment of each group, it is reasonable to assume a convergence toward the mean of the group. Therefore, the sentiment should be somehow centered to the middle of the scale. However, different groups should still have different values.

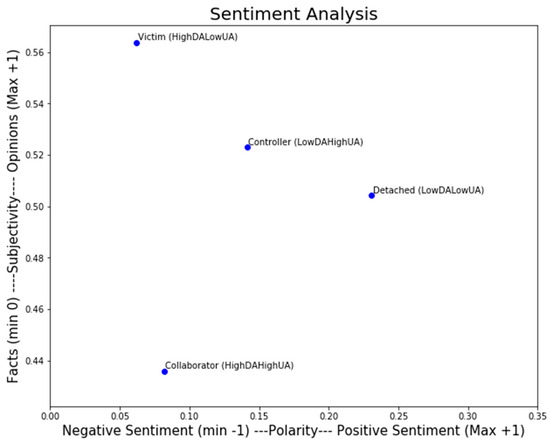

Observing the plot in Figure 3, we see that participants belonging to the preliminary groups detached and controller express more positive sentiments (Polarity, X-axis). This is in alignment with previous research. Users have been found to perceive their interactions with smart things more positively when exercising their agency compared to situations where the objects are the agents [34]. In addition, users who feel more superior to their VCSA, regarding it as a servant, are more likely to have increased interactions with it [31]. Collaborators, who attribute high agency both to themselves and to their device, differ from the other three profiles by being more fact-based and less opinionated (Subjectivity, Y-axis) in their discourse. Possibly, the tendency to attribute agency both to yourself and to your device goes hand in hand with the adoption of more factual and less opinionated language and, according to our theorizing, reflects the aim of these users to have a more multi-faceted and collaborative relationship to their personal devices.

Figure 3.

The four agency profiles according to Sentiment Analysis.

Victims and collaborators are similar on the axis of Polarity, as they are both skewed toward neutrality rather than positive sentiment; however, we can observe a difference on the axis of Subjectivity. Supporting the profiling of victims as attributing low agency to themselves and high agency to their devices, their discourse is more opinion-based and draws less from factual language.

3.4. Data Analysis: User and Device Agency and the Background Variables

Using statistical analysis, we investigated whether the levels of user agency and device agency depend on the following background variables: the respondents’ (1) age, (2) sex, (3) educational level, (4) professional field, (5) working experience, (6) working situation, and (7) professional knowledge of one or more of the following disciplines: (i) the Internet of Things, (ii) Human–Computer Interaction, (iii) Artificial Intelligence, (iv) Big Data, or (v) Requirement Engineering. In addition, the survey included a question concerning (8) whether the respondent had been professionally involved in researching, producing, marketing, or selling smart devices, and (9) the category of the device that they wanted to focus on when taking the survey.

In analyzing the normality of the data with a visual inspection of the histograms, using the Shapiro–Wilk test, and conducting an analysis of skewness and kurtosis, we found that the data were not normally distributed. For this reason, we conducted all the statistical analyses first with non-parametric tests that do not assume normality. We also conducted the analyses with the parametric equivalents. The same results were obtained in both cases. Authors in [48] argued that ANOVA is a robust method also when the data are not normally distributed, and it is therefore to be preferred over the weaker Kruskall–Wallis. Thus, we present the results of ANOVA and the parametric tests that follow.

The non-parametric tests conducted were those of Kruskall–Wallis, Dunn (pairwise comparisons), and Mann–Whitney. The parametric ones were one-way ANOVA and post-hoc (i) Tukey, (ii) Bonferroni, (iii) Games–Howell, and (iv) Gabriel, all of which yielded identical results. Since our sample sizes were nonidentical, we report the results obtained with Gabriel. Finally, we also conducted an independent sample t-test.

3.5. Background Variables and Their Relationship with User Agency

In our sample, the mean of user agency was 2.44, which indicates a moderate level on the scale of 1–5, where 5 denotes the highest agency level. Levene’s test was used to analyze whether the variances of the subgroups created using the segmenting variables differed from each other significantly [49].

The Levene’s F test revealed that in terms of (1) age, the homogeneity of variance assumption was not met (p < 0.05). Hence, Welch’s adjusted F ratio was used. According to the one-way ANOVA, age did not have a significant effect on user agency (Welch’s F4223.77 = 2.30, p > 0.05, est. ⱷ2 = 0.01).

The one-way ANOVA showed that there was no significant effect of the (2) respondent’s sex (F2584= 0.662, ns, ŋ2 = 0.002) on user agency. Since we had only six respondents not identifying as either male or female, we also conducted an independent sample t-test with only those who identified as either male or female. In this way, we obtained the same result: sex does not affect user agency (t (579) = 0.614, p < 0.05, r = 0.03). Subsequent ANOVA analyses showed that (3) educational level (F5581 = 0.7, ns, ŋ2 = 0.006), (4) professional field (F8578 = 1.287, p > 0.05, ŋ2 = 0.018), (5) length of working experience (F7579 = 0.897, ns, ŋ2 = 0.01), and (6) working situation (F3583 = 0.770, ns, ŋ2 = 0.004) did not have significant effects on user agency.

The (9) category of device had a significant effect on user agency as shown through a one-way ANOVA (F8578 = 8,025, p < 0.01, ŋ2 = 0.10). More specifically, the respondents who chose a household cleaning device when responding to the questions scored highest on user agency (M = 2.83, SD = 0.83). The respondents choosing to focus on a personal assistant device had the lowest user agency (M = 1.99, SD = 0.81). We conducted post-hoc analyses to investigate which differences in user agency in terms of the category of device were significant. We used Gabriel’s test because of the differences in sample sizes [49].

Table 6 presents the significant differences in user agency. The plot shows how many respondents chose a particular device category (n), the mean score on user agency (M), the standard deviations (SD), all the significant differences between device categories with the significance levels indicated, and the 95% confidence intervals.

Table 6.

Post hoc analyses, significant comparisons in user agency. Note that ** imply that the difference is significant at the Bonferroni corrected alpha level and that * imply the difference is significant at p = 0.05.

According to the post-hoc tests, respondents choosing a personal assistant device (M = 1.99, SD = 0.81) had a significantly lower user agency than those choosing a smart watch/bracelet (M = 2.58, SD = 0.79), p= 2.1472 × 10−7, with a Cohen’s effect size of −0.7328 at a 95% CI [−0.9022–−0.2676].

The respondents who chose a personal assistant device when taking the survey, scored significantly lower on user agency than those participants who focused on a household cleaning device (M = 2.83, SD = 0.83), p = 1.3608 × 10−8, with an effect size of −1.0332 at a 95% CI [−1.2678–−0.4194]. The personal-assistant device owners also had a significantly lower user agency compared to those who focused on other household devices (M = 2.73, SD = 0.74), p = 0.000013, with an effect size of 0.9480 at a 95% CI [−1.1911–−0.2776]. These differences all hold at the Bonferroni-adjusted [29] alpha level of p = 0.00625.

The respondents taking the survey with a personal assistant device in mind had a significantly lower user agency than those focusing on a personal hygiene device (Mean = 2.72, SD = 0.72), but this p = 0.009 does not hold valid after the Bonferroni correction. The effect size was 0.9459 at the 95% CI [1.3586–0.0921]. In addition, the respondents choosing a personal health device (M = 2.59, SD = 0.82) differed from those choosing a personal assistant device (p = 0.019, effect size 0.7335, 95% CI [−1.1430–0.0484]. These did not hold after a Bonferroni correction.

Moreover, the participants who chose a smart tv/video streaming device (M = 2.30, SD = 0.76) scored significantly lower on user agency than those who chose a household cleaning device (M = 2.83, SD = 0.83), p = 0.001, with an effect size of 0.6686 and with a 95% CI [0.1302–0.9324]. This p holds at the Bonferroni-adjusted p-level of 0.00625. The respondents who did not choose to answer based on a smart device but chose a computer/mobile phone (M = 2.34, SD = 0.61) had significantly lower user agency compared to those choosing a household cleaning device (p = 0.011, effect size: 0.6814, 95% CI [0.0589–0.9311]). This does not hold after the Bonferroni correction.

To compare the levels of user agency between (7) those who indicated having professional knowledge of fields related to smart devices with the respondents who did not, we conducted an independent sample t-test. There was no significant difference (t (585) = −0.51, p > 0.05).

An additional independent sample t-test was conducted to compare the user agency of those who (8) indicated having professional experience with researching, producing, marketing, or selling smart devices with that of those who did not. Respondents with professional experience with smart devices (M = 2.35, SD = 0.82) differed significantly from those with no experience (M = 2.50, SD = 0.78) (t (585) = 2.31, p = 0.021, 95% CI [0.02341–0.28769]). In other words, people who had professional experience with smart devices reported a lower user agency than those without this kind of experience.

3.6. Device Agency and the Background Variables

To analyze whether the demographic and other background variables affected device agency, we conducted the same analyses consisting of one-way ANOVAs and t-tests as in the case of user agency. The mean of the device agency was 1.31, which, on a scale of 1–5, is very low. Thus, our respondents did not attribute much agency to their devices.

According to one-way ANOVA, the respondent’s (1) age (F4586 = 1.61, p > 0.05, ŋ2 = 0.01) and (2) sex (F2584 = 0.79, ns, ŋ2 = 0.0027) did not have significant effects on the level of device agency. Six respondents did not identify as male or female, so we also conducted an independent sample t-test including only those who identified as either male or female. We obtained the same result (t (579) = −0.81, p > 0.05, r = 0.03).

According to a one-way ANOVA, the respondents’ (3) educational level (F5581 = 1.20, p > 0.05, ŋ2 = 0.02), (4) professional field (F8578 = 1.73, p > 0.05, ŋ2 = 0.02), (5) length of working experience (F7579 = 1.51, p > 0.05, ŋ2 = 0.018), (6) working situation (F3583 = 1.91, p > 0.05, ŋ2 = 0.01), and (9) the category of the chosen device (F8578 = 1.44, p > 0.05, ŋ2 = 0.02) did not have significant effects on device agency.

To compare the scores on the device agency of (7) those who indicated having professional knowledge of related fields with the scores of those who did not claim to have such experience, we conducted an independent sample t-test. Professionally experienced people did not differ significantly from people who did not have professional knowledge of smart devices (t (585) = −0.12, p > 0.05, r = 0.01). We also performed an independent sample t-test to compare (8) those with professional experience with researching, producing, marketing, or selling smart devices with those who did not indicate having this kind of experience. Respondents who had professional experience with smart devices did not differ significantly from the participants without such experience (t (585) = −1.34, p > 0.05, r = 0.06).

4. Discussion

In this paper, we have introduced, on the basis of a literature review as well as statistical analyses, a tag cloud analysis, and a sentiment analysis of data collected with a survey, the notions of user and device agency. We are positioning ourselves in conversation with the literature on affordances, especially in the later wave where affordances are defined as emerging from the relationship between the user and the object, thus reflecting the combination of both of their characteristics [7,10]. We agree that the notion of affordances as the designed-in characteristics of an object defining how an object can be used [6] forms the baseline for what affordances are and how the users interact with their devices. The user does not have limitless freedom in perceiving the characteristics of their device.

In this paper, we have looked at the kind of action capacities that the user attributes to their device. The attributed agency is not identical to the actual potentials of the device; the user might perceive the device as unhelpful in completing tasks that the device was designed to perform or even attribute capacities that were not originally designed-in to it. As affordances emerge from the relation between an object and a goal-oriented actor [7,8,9,10,13], the notion of agency, understood in a broad way as in this paper, can contribute to providing a deeper insight into what these goals are and how the users position themselves as able or not able to realize them.

Currently, the notion of both humans and technology having agency of their own, albeit of a different kind, and technology as both enabling and restricting human agency, is rather widely accepted [7,16,17,18,19,20,21]. We align ourselves with this thinking, but at the same time, we have attempted to elaborate on what agency actually means, taking the stance that the agency of technology is always also something attributed to it by humans.

This paper positions itself in conversation with the notion of agency as understood in the fields of Information Management, especially HCI, while also borrowing from psychology. In HCI, agency has traditionally often been defined as the user’s sense of control over the device. In this paper, we have argued that this conceptualization is too narrow to capture the full range of what agency can mean in terms of a human user’s relation to their device. Moreover, as authors in [3] have argued, both the user’s immediate sense of agency in terms of individual actions happening at a timescale of less than a second and the feeling that they have mastery over their long-term goals are important in terms of the user experience. The items included in our analysis cover, theoretically, actions at any timescale while reflecting the user’s sense of agency as accumulated over the course of repeated device interactions.

Observing the constitution of the agency factors as they emerged in our exploratory factorial analyses offers interesting insights. User agency emerged as the user’s experience in that they are using the device flexibly and in the best possible way so that the device is actually helpful in achieving their goals. Feeling positive about the device or understanding how it works were not part of user agency as it emerged in this study. Device agency emerged as a concept that reflects whether or not the device is perceived as being able to independently initiate, change, and stop its actions and function independently of the user. Interestingly, the device’s agency was not a matter of it, e.g., having intelligence of its own or being an intelligible interaction participant. Thus, device agency emerged as a concept in alignment with the notion of authors in [19]: actions explainable by material cause and effect represent the kind of agency traditionally attributed to both humans and technology.

In our analyses, user agency emerges as the experience of being able to use the device flexibly in unison with one’s own personal goals; aspects related to positive feelings with the device, perceiving oneself as able to understand how it functions, or any anthropomorphized sense of the device as an active participant in the interaction did not emerge as related to the user’s sense of agency. Thus, user agency is defined as the general experience of being able to use the device optimally to realize one’s goals, while device agency is more specifically about the gadget initiating, changing, or stopping its functions dependent or independent of the user.

4.1. User and Device Agency and Their Implications for Designing HCI Experiences

In this paper, we argued that agency is not only about the user’s feeling of control over a device, especially when defined in a simple motor-cognitive manner. Agency is a dimensional concept that has a low and a high end, and the agency that the user attributes to themselves is separate from the agency that they attribute to their device.

In this research, personal assistant devices stood out from the other devices. The participants choosing to focus on them experienced significantly less user agency than the users who chose to focus on other devices when taking the survey (see Table 6). Personal assistants are sophisticated devices designed to make users perceive them as more than just objects, inviting users to anthropomorphize them. It is possible that this creates high expectations for both what the device should be able to do and for what the user should be able to perform with it. We hypothesize that personal assistants are examples of devices that are very prone to creating frustrating experiences for the user, as here indicated by lower levels of user agency. Designers of user experiences should take into account the fact that personal assistant devices seem to be a particularly challenging device group in terms of creating a sense of agency for the users. Their sense of agency could be increased by offering the users more chances to feel that they can use the device to serve in reaching their goals and that they can learn to use it in increasingly optimal ways.

Perhaps surprisingly, people with professional experience with smart devices scored lower on user agency than the respondents without such experience. It is possible that their more in-depth understanding of devices causes this group to place higher expectations on themselves with regard to what they should be able to do and achieve with their device. It seems that interface designers should pay specific attention on increasing the agency of these type of tech-savvy users. This could be accomplished by providing them more personalized chances to develop an understanding of the functions of the device and how they can be streamlined with their goals and actions, and perhaps by providing them feedback to underline the experience that they are using the functions of the device in an increasingly optimal manner.

We acknowledge that further research is needed to confirm and better understand the suggested classification of user–device interactions into the four different groups. In the future, the categorization matrix of controller, collaborator, detached, or victim may be beneficial for designers in creating HCI experiences. In our study, these user profiles were not dependent of the background variables such as the user’s age, sex, or education, but on the kind of device the user is interacting with. This means that instead of categorizing the users per se, we are suggesting a way to classify a particular user’s interactions with a particular device. We assume that users can manifest different kinds of relationship profiles with different devices, and thus, they could possibly be characterized by a collection of different user–device interaction profiles.

According to our theory, the user feeling agentic in relation to their device is always to be preferred over them not feeling this way. In this, we align with previous research that has often argued that positive user–device relationships are based on the user experiencing that they are in control and that the device is not outsmarting them [31,34,35]. While the user’s experience should always be agentic, a positive relationship with a device can include the user attributing both high or low agency to their device. In this study, low device agency meant that the device was not seen as able to independently start, modify, and finish its processes. Thus, low device agency should not be perceived as a negative element; instead, in some devices and contexts, such an aspect may actually foster a positive user experience.

We suggest that interfaces should be designed in a manner that allows the user to feel that they are able to use the device to do things that are relevant for them in a specific situation. In other words, the device’s potentials (affordances) should be aligned with the user’s actual needs and goals to support user agency. This could be further reinforced by implementing a feedback system that lets the user know how they have been using their device to fulfil their own personally meaningful goals. Ideally, this feedback system is incorporated into a way of measuring the user’s level of agency with this particular device. Authors in [35] have suggested that balancing human and object agency and enhancing them simultaneously can occur by including human input and incorporating user-related cues to ensure that the invisible user input becomes more visible to the users. We add that this user input should be directly related to the user’s situation-specific goals and designed to highlight the human user being able to use the device in the optimal way.

It should be noted that we do not see agency as a static phenomenon. The user–device interaction profiling is, potentially, a dynamic way to illustrate the user’s journey with a particular device. Furthermore, we suggest that smart device interfaces could potentially be designed with the particular user–smart device interaction profile in mind. The goal would be to foster the evolution of users who manifest detached or victim dynamics toward developing controller or collaborator interactions. We suggest that simplicity of design and underlining the assistance that the device can provide in terms of the user’s personally meaningful and practical goals should be preferred over very sophisticated features, especially to enable the victim or detached dynamics to develop more user agency. Similar points about interface design have been raised earlier by, e.g., Schaumburg, who argued that the designing of user interfaces should be guided by assistance with the user’s task instead of emphasizing social mimicry. If the design efforts to fill the object with social characteristics disturbs the user′s main goal, the technology is likely to be rejected [50].

We do not suggest that the user’s agency, by definition, increases over time in accumulating interactions with a particular device. Quite on the contrary, our results indicate that people who have professional experience with working with smart devices have a lower user agency than people without such experience. It is likely that different users experience different journeys with their devices. This can mean evolving from more to less agency, vice versa, or having a more jigsaw experience including both more and less agentic interactions.

4.2. Limitations and Avenues for Future Research

The results of this study are preliminary and should not be generalized, as our sample consisted, to a high degree, of educated people with professional knowledge and experience with technology. The obvious limitations also include the fact that this study is based on the first iteration of a survey and on an exploratory rather than confirmatory factorial analysis. However, we do venture to argue that we have evidence in support of our theory of agency in human–smart device interactions.

It is plausible that our preliminary survey has not been able to capture all possible nuances and varieties of user agency and device agency. Hence, there can very possibly exist an even richer matrix of qualitatively different agencies that the user can attribute to themselves and to their device, and that these vary based on the category of device. Moreover, the relationship between reported agency attributions and agency manifest in context-dependent and situated interactions with the devices, which are not the same thing, and how, e.g., high user agency shows in actual device use remains to be investigated in future research.

The previous literature on agency is theory-heavy and does not provide many operationalizations of the concept. At its best, studies limit themselves to asking participants whether they feel that they caused a certain action to happen or not (see, e.g., [3,27,28]). At the other end of the spectrum, agency has been defined so vaguely as to mean anything and everything at the same time. With this paper, we hope to advance the conversation of what is agency in human interactions with technology, and what kinds of aspects of user experience should be taken into account in future studies concerning people’s interactions with smart devices. Also, since smart devices are a varied group of increasingly sophisticated devices that serve users in a multiplicity of everyday situations, there is a need to widen our understanding of the aspects of agency in order to better grasp this plethora of attributed agencies at work. It remains for further research to investigate how the different aspects of agency play out with different devices and depending on the context and goal of the user.

We provide preliminary evidence of how the constructs of user agency and device agency can be used as proxies for investigating the user’s experiences with their device. In future research, the conceptualizations presented here should be refined in combination with existing constructs that have proved relevant for describing human–technology interactions, such as anthropomorphism or the expansion of self. In addition, a further iteration of the survey used here should be conducted, taking into account the results of the factorial analysis in designing the survey items and then using an expert panel to assess the new lists of candidate items for the survey. More research is also needed to understand whether the constructs of user agency and device agency function as mediators for other factors mentioned here, such as anthropomorphism [39]. Eventually, the preliminary model of agency in human–smart device interaction could be a part of a wider theory including also a variety of other relevant aspects of how people relate to their devices.

The survey presented in this paper should be further refined and tested with other user populations in addition to those of the highly educated and technologically savvy, and used in unison with other methodologies aiming to grasp the practical and everyday level of device use in relation to the user’s specific attributions of user and device agency. Another promising venue of research concerns the development of user experiences over time and how users can, in interacting with their devices, learn to experience and attribute agency in ways that support them using the device in the manner that is optimal for them.

5. Conclusions

In this paper, we have argued that user agency and device agency exist as two separate constructs that are independent of each other. We reached out to users and explored what kinds of agency they attribute to themselves and to their devices. We show preliminary empirical evidence of the constructs of user agency and device agency and argue that the ways in which users attribute agency to themselves and to their personal devices frame how the users perceive and leverage the affordances of the device. Consequently, the attribution of user and device agency can be approached as a way to measure whether the user masters the potential capabilities of the device in a maximal manner or not. We propose modeling user–device interactions with a fourfold matrix that could serve interface designs by further profiling users and their experiences.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, H.T. and F.L.; methodology, H.T. and F.L.; software, H.T. and F.L.; validation, F.L.; formal analysis, H.T. and F.L.; investigation, H.T. and F.L.; resources, H.T. and F.L.; data curation, F.L.; writing—original draft preparation, H.T.; writing—review and editing, H.T. and F.L.; visualization, F.L.; supervision, F.L.; project administration, F.L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The research not receiving any funding information.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available in [51].

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Baird, A.; Maruping, L.M. The Next Generation of Research on IS Use: A Theoretical Framework of Delegation to and from Agentic IS Artifacts. MIS Q. 2021, 45, 315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moore, J.W. What is the sense of agency and why does it matter? Front. Psychol. 2016, 7, 1272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Limerick, H.; Coyle, D.; Moore, J.W. The Experience of agency in human-computer interactions: A review. Front. Hum. Neurosci. 2014, 8, 643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schneiderman, B. Direct manipulation for comprehensible, predictable and controllable user interfaces. In IUI ‘97: Proceedings of the 2nd International Conference on Intelligent User Interfaces, Orlando, FL, USA, 6–9 January 1997; Moore, J., Edmonds, E., Puerta, A., Eds.; Association for Computing Machinery: New York, NY, USA, 1997; pp. 33–39. [Google Scholar]

- Gibson, J. The Theory of Affordances. In Perceiving, Acting, and Knowing toward an Ecological Psychology; Shaw, R., Bransford, J., Shaw, R., Bransford, J., Eds.; Lawrence Erlbaum Associates: Hillsdale, NJ, USA, 1977; pp. 67–82. [Google Scholar]

- Norman, D. The Psychology of Everyday Things; Basic Books: New York, NY, USA, 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Hutchby, I. Technologies, Texts, and Affordances. Sociology 2001, 2, 441–456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stendal, K.; Thapa, D.; Lanamäki, A. Analyzing the concept of affordances in information systems. In Proceedings of the 49th Hawaii International Conference on System Sciences (HICSS), Koloa, HI, USA, 5–8 January 2016; pp. 5270–5277. [Google Scholar]

- Volkoff, O.; Strong, D.M. Affordance theory and how to use it in is research. In The Routledge Companion to Management Information Systems; Galliers, R.D., Stein, M.-K., Eds.; Taylor and Francis: Milton, UK, 2017; pp. 232–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pozzi, G.; Pigni, F.; Vitari, C. Affordance Theory in the IS Discipline: A Review and Synthesis of the Literature. In Proceedings of the 20th American Conference on Information Systems AMCIS 2014 Proceedings, Savannah, GA, USA, 7 November 2014; Volume 13, pp. 1–12. [Google Scholar]

- Salo, M.; Pirkkalainen, H.; Chua CE, H.; Koskelainen, T. Formation and Mitigation of Technostress in the Personal Use of IT. MIS Q. 2022, 46, 1073–1108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaptelinin, V.; Nardi, B. Affordances in HCI: Toward a mediated action perspective. In Proceedings of the Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems, Austin, TX, USA, 5–10 May 2012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zammuto, R.F.; Griffith, T.L.; Majchrzak, A.; Dougherty, D.J.; Faraj, S. Information technology and the fabric of organization. Organ. Sci. 2007, 18, 749–762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bandura, A. Social Cognitive Theory: An Agentic Perspective. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 2001, 52, 21–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McCarthy, J.; Wright, P. Putting ‘felt-life’ at the centre of human–computer interaction (HCI). Cogn. Technol. Work 2005, 7, 262–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rose, J.; Jones, M. The Double Dance of Agency: A Socio-Theoretic Account of How Machines and Humans Interact. Systems, Signs & Actions. Int. J. Commun. Inf. Technol. Work 2005, 1, 19–37. [Google Scholar]

- Boudreau, M.-L.; Robey, D. Enacting Integrated Information Technology: A Human Agency Perspective. Organ. Sci. 2005, 16, 3–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Engen, V.; Pickering, J.; Walland, P. Machine Agency in Human-Machine Networks; Impacts and Trust Implications. In Proceedings of the 18th International Conference on Human-Computer Interaction International, Toronto, ON, Canada, 17–22 July 2016; Volume 9733, pp. 96–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, D.; Verdicchio, M. AI, agency and responsibility: The VW fraud case and beyond. AI Soc. 2019, 34, 639–647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Novak, T.; Hoffman, D. Relationship journeys in the internet of things: A new framework for understanding interactions between consumers and smart objects. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 2019, 47, 216–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rammert, W. Distributed Agency and Advanced Technology Or: How to Analyse Constellations of Collective Inter-Agency. In Agency without Actors? New Approaches to Collective Action; Passoth, J., Peuker, B., Schill, M., Eds.; Routledge: London, UK, 2014; pp. 89–112. [Google Scholar]

- Serrano, C.; Karahanna, E. The compensatory interaction between user capabilities and technology capabilities in influencing task performance. MIS Q. 2016, 40, 597–622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nevo, S.; Nevo, D.; Pinsonneault, A. A temporally situated self-agency theory of information technology reinvention. Mis Q. 2016, 40, 157–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michelle, C.; Varun, G. Me. My Self, and I(T): Conceptualizating Information Technology Identity and its Implications. MIS Q. 2015, 39, 931–957. [Google Scholar]

- Berberian, B. Man-Machine teaming: A problem of agency. IFAC-PapersOnLine 2019, 51, 118–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berberian, B.; Sarrazin, J.C.; Le Blaye, P.; Haggard, P. Automation technology and sense of control: A window on human agency. PLoS ONE 2012, 7, e34075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McEneaney, J. Agency Attribution in Human-Computer Interaction. In Engineering Psychology and Cognitive Ergonomics EPCE 2009, Lecture Notes in Computer Science; Harris, D., Ed.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2009; Volume 5639, pp. 81–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McEneaney, J. Agency Effects in Human–Computer Interaction. Int. J. Hum.-Comput. Interact. 2013, 29, 798–813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sato, A.; Yasuda, A. Illusion of sense of self-agency: Discrepancy between the predicted and actual sensory consequences of actions modulates the sense of self-agency, but not the sense of self-ownership. Cognition 2005, 94, 241–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mick, D.G.; Fournier, S. Paradoxes of Technology: Consumer Cognizance, Emotions, and Coping Strategies. J. Consum. Res. 1998, 25, 123–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schweitzer, F.; Belk, R.; Jordan, W.; Ortner, M. Servant, friend or master? The relationships users build with voice-controlled smart devices. J. Mark. Manag. 2019, 35, 693–715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shneiderman, B.; Plaisant, C.; Cohen, M.; Jacobs, S.; Elmqvist, N. Designing the User Interface: Strategies for Effective Human-Computer Interaction, 6th ed.; Pearson: Boston, MA, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Scott, J.E.; Walczak, S. Cognitive engagement with a multimedia ERP training tool: Assessing computer self-efficacy and technology acceptance. Inf. Manag. 2009, 46, 221–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, H.; Kim, K.J. Feeling connected to smart objects? A moderated mediation model of locus of agency, anthropomorphism, and sense of connectedness. Int. J. Hum.-Comput. Stud. 2020, 133, 45–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, H.; Wu, M.; Jung, E.; Shapiro, A.; Sundar, S.S. Balancing human agency and object agency: An end-user interview study of the internet of things. In Proceedings of the 2012 ACM Conference on Ubiquitous Computing (UbiComp ‘12), Association for Computing Machinery, New York, NY, USA, 5 September 2012; pp. 1185–1188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gunkel, D.J. Communication and Artificial Intelligence: Opportunities and Challenges for the 21st Century. Communication 2012, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassenzahl, M. The Interplay of Beauty, Goodness, and Usability in Interactive Products. Hum.-Comput. Interact. 2004, 19, 319–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alter, S. Making Sense of Smartness in the Context of Smart Devices and Smart Systems. Inf. Syst. Front. 2020, 22, 381–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waytz, A.; Heafner, J.; Epley, N. The mind in the machine: Anthropomorphism increases trust in an autonomous vehicle. J. Exp. Soc. Psychol. 2014, 52, 113–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dillon, A. Beyond usability: Process, outcome and affect in human-computer interactions. Can. J. Libr. Inf. Sci. 2002, 26, 57–69. [Google Scholar]

- Shin, D.-H. Cross-analysis of usability and aesthetic in smart devices: What influences users’ preferences. Cross Cult. Manag. 2012, 19, 563–587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.-W.; Gupta, S.; Koh, J. Investigating the intention to purchase digital items in social networking communities: A customer value perspective. Inf. Manag. 2011, 48, 228–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belk, R. Possessions and the Extended Self. J. Consum. Res. 1988, 15, 139–168. [Google Scholar]

- Costello, A.B.; Osborne, J. Best practices in exploratory factor analysis: Four recommendations for getting the most from your analysis. Pract. Assess. Res. Eval. 2005, 10, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taber, K.S. The Use of Cronbach’s Alpha When Developing and Reporting Research Instruments in Science Education. Res. Sci. Educ. 2018, 48, 1273–1296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cortina, J.M. What is coefficient alpha? An examination of theory and applications. J. Appl. Psychol. 1993, 78, 98. [Google Scholar]

- Kline, P. An Easy Guide to Factor Analysis; Routledge: London, UK, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Wim, J.; Katrien, W.; Patrick, D.; Patrick, V. Marketing Research with SPSS; Prentice Hall, Pearson Education: Upper Saddle River, NJ, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Field, A. Discovering Statistics Using SPSS, 2nd ed.; Sage Publications: London, UK, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Schaumburg, H. Computers as Tools or as Social Actors?—The Users’ perspective on Anthropomorphic Agents. Int. J. Coop. Inf. Syst. 2001, 10, 217–234. [Google Scholar]

- Lelli, F.; Heidi, T. A Survey for investigating human and smart devices relationships. 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).