Abstract

Three decades of extensive work in the HIV field have revealed key viral and host cell factors controlling proviral transcription. Various models of transcriptional regulation have emerged based on the collective information from in vitro assays and work in both immortalized and primary cell-based models. Here, we provide a recount of the past and current literature, highlight key regulatory aspects, and further describe potential limitations of previous studies. We particularly delve into critical steps of HIV gene expression including the role of the integration site, nucleosome positioning and epigenomics, and the transition from initiation to pausing and pause release. We also discuss open questions in the field concerning the generality of previous regulatory models to the control of HIV transcription in patients under suppressive therapy, including the role of the heterogeneous integration landscape, clonal expansion, and bottlenecks to eradicate viral persistence. Finally, we propose that building upon previous discoveries and improved or yet-to-be discovered technologies will unravel molecular mechanisms of latency establishment and reactivation in a “new era”.

Keywords:

HIV-1; provirus; persistence; cure; integration; transcription; ART; latency; latent reservoir; epigenomics 1. The Latent Reservoir in the Spotlight

The development of combination anti-retroviral therapy (ART), which targets several steps of the viral life cycle, decreased patient viral titers to below the limit of detection using contemporary methods [1,2]. This remarkable biomedical breakthrough was the tipping point for reducing mortality and extending the lifespan of HIV-infected individuals. However, despite initial hopes of undetectable viremia, the discontinuation of ART quickly led to viral titer rebound [3,4], suggesting the presence of a “latent” yet inducible and replication-competent viral reservoir. Consequently, in efforts to control infection, patients must remain on a lifelong regime of ART to prevent the rebound of plasma viremia.

The best characterized latent reservoir in patients consists of integrated viral DNA in resting memory CD4+ T cells [2,5], which are refractory to immune surveillance and current ART regime. Studies over the past decade have revealed the timeline, size, stability, and composition of the latent reservoir in ART treated patients.

1.1. Timeline, Size, Stability, and Composition of the Latent Reservoir

Kinetically, the latent reservoir is established within days after infection regardless whether the patient has undergone ART [6]. The stability of the latent reservoir in resting memory CD4+ T cells in patients receiving highly suppressive therapy with no detectable viremia for many years has been estimated to have a half-life of ~44 months [7]. Given this long-term stability, it is impossible to cure HIV by waiting for the infected cells to decay over time.

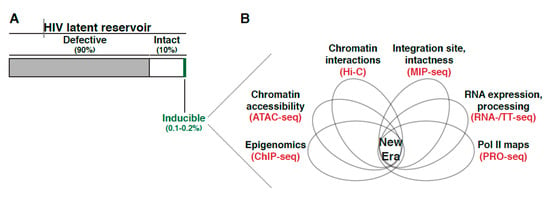

In addition to the stability of the latent reservoir, there have been attempts to estimate its size and composition. Initial studies used PCR-based techniques but were later found to have largely overestimated the reservoir magnitude [8,9,10,11,12], as the majority of latently-infected cells in patients hold replication-incompetent proviruses. This discovery indicated that defective genomes are not the source of the rebound virus upon ceasing ART, although they can otherwise contribute to continued immune activation and exhaustion [10,13].

More recent assays, such as the quantitative viral outgrowth assay (QVOA), measure the latent reservoir by computing the number of latently-infected resting CD4+ T cells that produce replication-competent virus after in vitro stimulation typically with strong T-cell agonists [14,15]. With this assay, it was estimated that about one in a million resting CD4+ T cells in the blood of ART treated patients can be induced to produce replication-competent virus [7,16,17,18]. Nonetheless, in contrast to PCR detection methods, the QVOA largely underestimates the reservoir size as not all intact proviruses reactivate after one round of immune stimulation, i.e., subsequent rounds of treatment can activate a larger (2–3-fold) population of intact proviruses [8,19,20].

In theory, most intact proviruses are capable of producing replication-competent virus. However, the frequency of cells harboring intact proviruses that can, in theory, be stimulated is ~30 times larger than the actual frequency of cells that are induced in the QVOA assay. The collective evidence suggest ~90% of proviral genomes in resting memory CD4+ T cells within individuals on ART are defective, and from the remaining ~10% of intact proviruses [8,19,21] only ~0.1–0.2% can be reactivated, posing the question as to where in the human genome is this small fraction of intact and reactivatable proviruses located, and what are the molecular mechanisms underlying their persistence.

Overall, the scarcity of cells containing intact proviruses has posed limitations for defining the composition and underlying molecular mechanisms regulating these types of proviruses. Recent tools to simultaneously define both integration positions and proviral intactness [22,23] are starting to reveal a clearer picture of the “physiologic” latent reservoir and its heterogeneous mechanism of regulation.

Strikingly, Swanstrom and colleagues reported that the genetic diversity of the latent reservoir largely depends on the timing of initiating ART post-infection (i.e., acute or chronic phase) [24], where ~71% of unique intact proviruses induced from post-ART samples were genetically similar to samples taken shortly before ART initiation. Thus, within the intact latent reservoir, there is a small population of inducible proviruses that can potentially reseed the active viral reservoir if ART is interrupted. Further, to sustain viral lifelong persistence, several recent studies have shown the intact, replication-competent proviruses within populations of resting memory CD4+ T cells are maintained by inconspicuous levels of clonal expansion [20,25,26,27,28] which could influence targetable approaches. Sékaly and colleagues described that proviruses are maintained by either homeostatic proliferation (in memory CD4+ T cells) or antigen stimulation (in resting central memory CD4+ T cells) rather than by viral re-infection [29]. Moreover, it was further suggested that clonal expansion can be driven by cytokine and antigen stimulation without causing antiviral effects or inducing viral production, thereby giving key biological insights suggesting an additional challenge to reverse latency in the clinics [30].

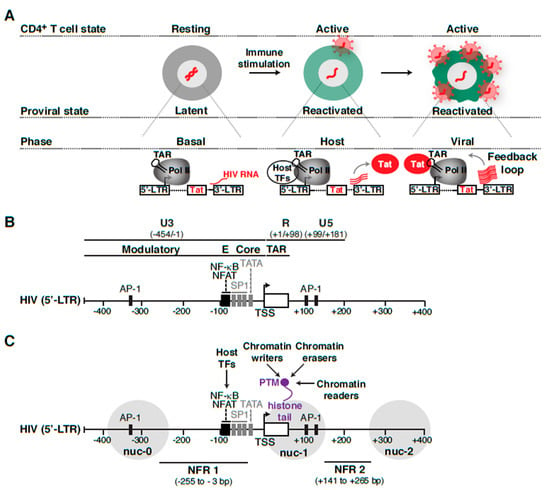

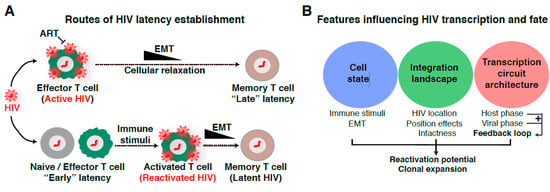

1.2. Routes of Latency Establishment

The previous discoveries on the timeline, size, stability, and composition of the latent reservoir opened a field on itself and led to the long-lasting debate regarding how the reservoir is established. Different proposed routes have been made concerning how latency establishment occurs after HIV integrates into the genome of target immune cells (naïve and effector CD4+ T cell subsets) [4,5,31,32,33,34]. At present, the most widely accepted model of latency establishment is that HIV enters a latent state when effector CD4+ T cells transition to a resting memory state due to cellular relaxation, the so-called effector-memory-transition (EMT) [35,36] (Figure 1A, top panel). We refer to this mechanism as “late” latency because the provirus is initially active and later becomes inactive as a potential consequence of cellular relaxation, thereby suggesting a major contribution of host cell state on viral entry into latency. Alternative, non-mutually exclusive models proposed the direct infection of resting CD4+ T cells [37], and naive or effector CD4+ T cells in which the proviral genome is not efficiently transcribed (Figure 1A, bottom panel). In the latter case, it is likely certain integration sites promote “early” latency, in which the provirus becomes transcriptionally silent immediately after integration into specific, unfavorable genomic areas, despite the beneficial environment for proviral transcription and replication in effector CD4+ T cells (Figure 1A, bottom panel).

Figure 1.

Routes of latency establishment and features influencing HIV proviral transcription and fate. (A) In “early” latency, HIV integrates into genomic domains not supporting transcription, but is otherwise intact and induced by immune stimuli. Alternatively, HIV infects cells in different states of activation or during effector-memory transition (EMT) [35,36] in which cellular relaxation pushes an initial transcriptionally active provirus into a silent provirus promoting “late” latency. (B) List of features contributing to HIV proviral transcription and fate. The “cell state” denotes CD4+ T cells of any of the major subsets (e.g., Th1, Th2, Th17, Treg, Tcm) in different stages (naïve, effector, resting memory, and effector memory). The “integration landscape” describes the heterogeneous positions of HIV proviruses in the human genome and position effects. The complex “transcription circuit architecture” describes the progressions through the different phases of the HIV transcriptional program (basal, host, and viral) leading to the positive-feedback loop. See text and Figure 4A for details.

In contrast to “late” latency, “early” latency suggests a major contribution of integration landscape, but not cell state, of viral entry into latency. As such, the integration site can influence the provirus in different ways: (1) through a nucleosome position and epigenetic-driven mechanism, and/or (2) through an RNA polymerase II (Pol II) transcription-driven mechanism related to transcriptional interference [38,39]. On this topic, several landmark studies have surveyed the chromatin environment of single-copy integrated proviruses in CD4+ T cell lines such as Jurkat (the J-Lat clones), including nucleosome positioning [40,41], DNA methylation [42], and histone post-translational modifications (PTMs) [41,43,44,45,46] to study their impact on the establishment and/or maintenance of latency, thereby providing an initial view of the potential effect of integration landscape to proviral transcription and fate (active vs. latent; inducible vs. not inducible). In the sections below, we expand on these topics to describe key discoveries, potential limitations, and urgently needed ideas for future investigations to underpin their contributions to disease progression in physiologically relevant models and patient samples.

One major paradigm about “late” latency is whether it is simply attributed to cells dropping immune signaling dynamics during EMT (Figure 1A, top panel), thereby reducing transcription-sustaining host cell factors, or whether the virus actively “pushes” cells into the resting state by rewiring host transcriptional programs [32], or a combination of both. Conversely, other theories have argued in favor of a cell-autonomous model establishing latency where the virus itself shuts-off viral transcription without host cell-intrinsic or cell-extrinsic contributions [47], indicating a “free solo” scenario. However, the potential key viral players involved in the proposed mechanisms remain to be discovered. Together, these studies potentially indicate that both viral and host cell factors influence the establishment and maintenance of proviral latency.

Despite all these possible routes of latency establishment, one outstanding question in the field to address is whether there are several mechanisms operating at different levels due: (1) to the site of proviral integration into the human genome (weighting more on the proposed “early” latency model) and/or (2) to alterations in cell state leading to cellular relaxation (weighting more on the proposed “late” latency model) (Figure 1A).

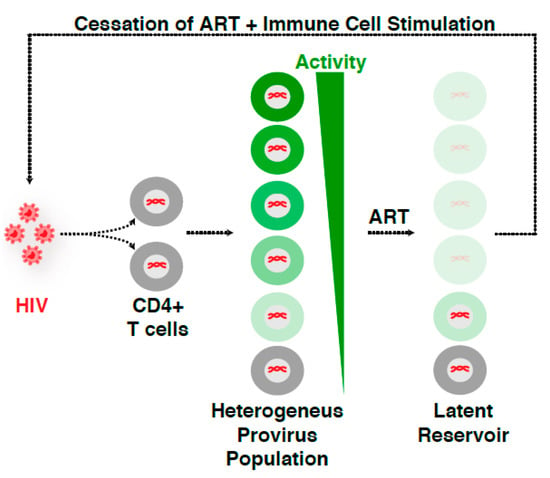

Because of the multiple routes of latency establishment and features influencing proviral transcription, including immune cell state, integration landscape, and complex transcription circuit architecture (Figure 1B), it has become difficult to ascertain their precise contribution to proviral fate. Indeed, the numerous possible variations on the origin of latency at the single-cell level may account for the rising of a heterogenous proviral population (Figure 2), whereby cells contain proviruses with variable degrees of activity (expression and replication). While ART stops viral replication in cells containing active proviruses, ART is unable to cope with the transcriptionally silent proviruses and those replicating at very low levels. Therefore, these proviruses survive therapy and generate a latent reservoir that upon ART cessation results in a rapid rebound of plasma viremia. We thus propose that a “new era” of research in this field will encompass uncoupling the influence of various regulatory features (immune cell state, integration landscape, and transcription circuit architecture) on proviral transcription (Figure 1B). We envision that building upon previous discoveries and improved technologies with the advent of genomics (e.g., single-cell) and deep learning will facilitate unraveling molecular mechanisms of latency establishment and reactivation. Further, this will enable the identification of novel cell targets, which may guide strategies to eliminate persistent reservoirs to end the HIV epidemic [48].

Figure 2.

HIV infection leads to a heterogeneous proviral population. HIV infection of CD4+ T cells yields a “heterogeneous provirus population” with a variable, continuum degree of gene expression and replication. ART stops viral replication and disease progression into the AIDS phase. However, ART is unable to cope with both the transcriptionally silent proviruses and those replicating at very low levels, thereby surviving therapy and generating the so-called “latent reservoir”. As such, ART discontinuation in the presence of immune stimulation results in a rapid rebound of virus, indicating that while ART suppresses viral replication, HIV is able to persist in an infectious state for years.

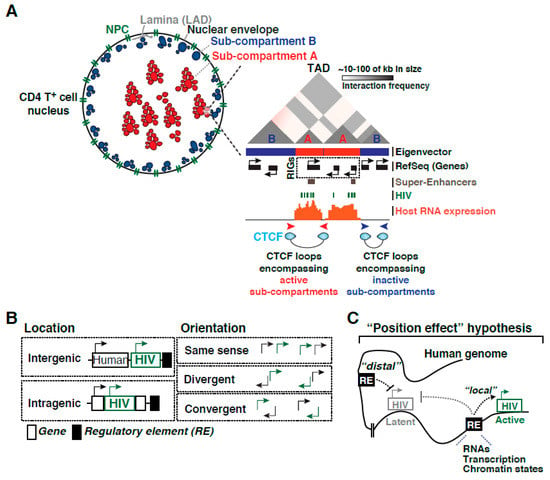

Given all these previous landmark discoveries, here, we provide a recount of the literature to discuss the evolution of the field, highlighting the use of various latency models and studies with patient isolates. At the same time, we will be presenting potential limitations of previous discoveries and discuss new approaches needed to move the field forward in our race to devise an effective HIV cure strategy in the “new era”. Specifically, we discuss the following: the role of the nuclear architecture in integration site selection, the current knowledge on how the integration landscape may influence HIV transcription dynamics and proviral fate, the role of nucleosomes and chromatin states, the functions of host cell machinery in regulating transcription, and finally combine these basic discoveries to better understand the therapeutic challenges faced.

7. Disease Relevance and Current Therapeutic Challenges

Early on, it has been noted that HIV persistence was due to viral latency and not drug failure citing limited mutation rates [264]. Where latency is maintained by memory CD4+ T cell survival (possibly leading to clonal expansion) and homeostatic proliferation ([29], reviewed in [265]), clinical interventions must include targeting not only viral replication, but the rebound provirus that perpetuates in proliferating memory CD4+ T cells too ([29], reviewed in [265]). As such, many therapeutic efforts have been initiated which fall under different strategic categories: Reducing the reservoir, immunologically control viral rebound, and silencing the reservoir (reviewed in [265]). It is worth noting these efforts are focused to target the intact inducible provirus, which some may argue is not a complete cure as defective provirus may still express viral proteins able to inflict harm [266]. Nonetheless, to highlight a few strategies, one method for reducing the reservoir is “shock and kill” which boosts the provirus out of latency using latency reversing agents (LRA) so that enhanced cytotoxic lymphocytes may completely purge the virus (reviewed in [267,268]). Immunotherapy includes the use of broadly neutralizing antibodies [269,270] and chimeric antigen receptor T (CAR-T) cells [271] to target viral envelope on the cell surface for killing. A “block and lock” strategy could be used for silencing the reservoir in where pharmacologic inhibitors are used to implore HIV into a permanent transcriptionally silent state [272]. Importantly, the efficiency of these strategies and the underlying molecular mechanisms is often biased to singular latency models used, such that when tested in non-homogeneous patient samples (Figure 2), the efficacy in reducing overall reservoir size is often questioned/limited (reviewed in [2]). Therefore, new attempts to capture generalizable model(s) of latency, such as combining cell line data with ex vivo approaches [236], is often at the forefront of identifying and confirming new compounds. It is clear the varying transcription activity within a reservoir is influenced by the heterogeneous integrated nature within a proviral population [75] (Figure 2). Even so, we must also consider the added complexity stemming from the different origins, or genesis, of each unique proviral integrations within the same individual (Figure 1). Distinguishing how the origin of establishing latency, for example an intact provirus arising from clonal expansion vs uniquely integrated intact proviruses, influences viral rebound and reseeding of active infection upon ART cessation may illuminate the strategic development of novel compounds or combination of treatments.

The importance of using primary models of latency is highlighted in the identification of benzotriazoles as a class of LRAs that inhibit STAT5 SUMOylation increasing its presence on the HIV proviral promoter [273]. Yet, as opposed to primary cells and ex vivo models of latency, benzotriazoles fail to reactivate in multiple immortalized models of latency (J-Lat clones) because they lack the IL-2 receptor (CD25), thereby impeding STAT5 activation [273]. Physiologically relevant models are increasingly being used in combination and/or to verify findings derived from immortalized models. This combination of approaches has aided the understanding of the chromatin landscape and offered insights into predicting and validating long-term efficient new compounds. For example, didehydro-cortistatin A (dCA) was shown to inhibit Tat function by preventing TAR binding to reduce viral replication in vitro using immortalized models of latency (HeLa-CD4-LTR-Luc) and later confirmed using patient samples [274,275]. Yet, even now, we are beginning to bypass immortalized models for mechanistic studies all together. For example, to understand the mechanism of dCA, Valente and colleagues assessed how dCA promotes epigenetic silencing by increasing nuc-1 occupancy at the proviral genome (Figure 4), thereby preventing Pol II from binding the promoter using patient samples ex vivo. These results further confirm long term efficacy using the bone marrow-liver-thymus (BLT) mouse model of latency and persistence [272].

Given the importance of chromatin-modifying complexes in silencing proviral transcription, they were the focus of many studies aimed at promoting latency-reversal and reduction of the latent reservoir. The SWI/SNF chromatin modifying complexes have been targets for the development of therapies in the clinical setting. However, given BAF and PBAF complexes share several subunits and have functionally opposed roles in proviral transcription, this has represented a roadblock for “shock and kill” approaches of an HIV cure. Further, several compounds were recently identified to target subunits of the SWI/SNF BAF complex, but were later reported to have toxic off-target effects [208]. Recently, Dykhuizen and colleagues used a high throughput approach to identify non-toxic small molecule inhibitors of the BAF complex, which led to the identification of macrolactam compounds as LRAs that reverse latency both in immortalized and primary models of latency as well as in CD4+ T cells from aviremic patients without causing toxicity or T cell activation [276]. These new compounds target the BAF-specific ARID1A subunit, thereby reducing repressive nucleosome occupancy at the 5′-LTR (Figure 4).

Beyond high-throughput approaches, another tactic others have taken is to provide a better kinetic understanding of the proviral chromatin environment as it transitioned into a latent state in a primary model of latency (CD4+ T cells transduced with the with anti-apoptotic molecule Bcl-2) during EMT (Figure 1) [277]. Expectedly, heterochromatin (named based on H3K9me3 or H3K27me3 densities at the provirus (Figure 4)) gradually stabilized as cells transitioned from the active to the resting state, and thus proviruses became less accessible with reduced activation potential. Such a tool may eventually help specify drug development to accurate chromatin environment profiles.

The strongest indications of LRA’s efficacy are in vivo studies using animal models. Garcia and colleagues showed how treatment with the compound AZD5582 in HIV infected BLT mice and SIV infected rhesus macaques under ART induced HIV and SIV RNA expression in several tissues including lymph node of the macaques and lymph node, thymus, bone marrow, liver, and lung of BLT mice [278]. Though no reduction in reservoir size was detected, these models can lead the way to determine dose, timing and pairing with other compounds to induce the cytotoxic lymphocyte killing of the persistent reservoir. As shown by Silvestri and colleagues though the IL-15 super agonist compound, N-803, is able to reactivate primary human CD4+ T cells latently infected with HIV in vitro, co-culturing with CD8+ T cells inhibited N-803–mediated latent provirus reactivation [279]. This was later confirmed in SIV infected macaques, where N-803 alone had no impact on the reservoir. Yet, combining N-803 with MT807R1, an antibody that depletes CD8+ T cells in vivo resulted in a robust SIV increase. Together, these studies illuminate how animal models can be used not only to test compound efficacy but also to develop latency reversing strategies that take into account physiologic variables.

Overall, the importance of cross-validation using different models of latency, with emphasis on physiologically relevant models, is becoming increasingly apparent. Additionally, a careful analysis of hundreds or even thousands of single proviruses integrated in unique positions and bearing unique genetic variants, and not population-based studies, will hone our understanding on the role of integration landscape and cell state on latency reversal potential and other therapeutic schemes.

8. The Ephemeral Nature of Ideas and Considerations for Future Research

Characterizing the latent reservoir composition was the first core discovery spurring an entire field dedicated to understanding the mechanisms underlying its establishment and maintenance. Though initially capturing the precise reservoir size and composition were low resolution estimates (i.e., either over- or under-estimating the size and intactness), improved and combined methodologies have continuously revised the latent reservoir profile, unveiling that only a miniscule proportion is intact and inducible (Figure 5A). By surveying the genetic environmental landscape in where proviruses have embedded themselves, many were able to define peculiar preferential “behaviors” of this intriguing virus. RIGs, genes where the provirus was found repeatedly integrated in patient samples, began to reveal the integration site could largely influence what would become the position effect phenomena (Figure 3) [75], in where the integration site neighborhood shift proviral activity. Indeed, it is clear the partialities extend beyond the 1D view of simply a proviral insertion into a linear scale, as the importance of 3D nuclear architecture and temporal order of events in respect to cell state have become more apparent. Nonetheless, each new uncovered characteristic adds to understanding the proviral integration code, or molecular rules tempering proviral fate. At the same time, there is a growing consensus that many of these preferences might only be observed in patient samples and lost in immortalized and/or primary models of latency suggesting limitations in applicability of models potentially attributed to in vivo “selective pressures” and fitness of select proviral groups not recapitulated in vitro.

Beyond fixed provirus physical location and compartmentalization, other influences of latency establishment and maintenance are much more fluid. Cell status, as illustrated by large fluctuations of nuclear transcriptional regulators and coregulators, can galvanize transcriptional responses when transitioning from resting to active status. The factor fluctuations may also be small enough only to generate heterogenized threshold within a state (at rest for example) due to stochasticity. Or the fluctuations may be at the local gene level where deposition of epigenetic marks, Pol II pausing, and/or nucleosome positioning can influence the inducibility of an otherwise intact provirus. Again, many conflicting results are often attributed to differences in models used for their respective studies given the multiple layers of variability (Figure 1B).

Because of the multifactorial aspects contributing to latency (establishment, maintenance, and reversal), it is obvious the era of singular cause is over. From a therapeutic perspective, the failure of LRAs has always been attributed to the same reason: inability of a single drug, which often target a single molecular rule of latency (e.g., HDAC inhibitor, BRD4 inhibitor, etc.), to reactivate the entire latent reservoir. This extends to screening for new drug compounds. In the “new era”, it will be imperative to integrate multiple approaches (such as multiple genetic datasets, epigenetics, transcriptomes, proteomics, 3D genome architecture, nuclear topology, chromatin states, transcriptional activity, proviral position, and intactness) followed by deep learning [75] to predict and experiment with emphasis at the single-cell level and across multiple models including patient samples, and interrogate “deep” (Figure 5B). Understanding how each molecular rule fits together (simultaneously or stepwise) and which rules govern individual proviruses (i.e., is it the same set of rules for all proviruses or are there different kits/sets of rules for different proviruses) will aid personalized therapeutic development and eventual eradication of HIV. However, one obvious but extreme challenge is how the dataset integration (Figure 5B) will be achieved if patient samples are composed of a scarce and heterogeneous population in which multiple CD4+ T cells contain proviruses integrated in unique regions in addition to the clonally expanded pool.

As physiological relevance is vital to remove distracting or inapplicable models/mechanisms from the discussion, preference must be given to use patient samples or primary cell systems. Yet, with the limitation of the number of intact proviruses within a patient to collect data from, alternative models may need to be developed. In this context, can primary models of latency be created in the presence of ART, without the ectopic expression of anti-apoptotic factors but allowing their long-term culturing without causing T cell exhaustion? With the advent of genome editing tools [280], can we engineer “anatomically” correct in vitro models of latency (in immortalized but noncancerous cells or naïve healthy donor cells) in where proviruses are directed to the same integration sites as those found in patient samples? Would this approach potentially remove the roadblock of limited number of cells? No doubt, this would raise additional questions as it would uncouple the specific integration site from latency status, i.e., would repeating the same integration site (not by clonal expansion, but by executing into the same insertion site) repeatedly yield the same “inducibility” or not? Will the integration site landscape remain the same? If the results are consistent, then the molecular rules must be stable and therefore targetable.

With our efforts to discuss a surmountable number of key discoveries and situate them in the context of previously published literature, we hope to provoke future work that will advance our understanding of this fascinating biomedical research challenge. New data supporting or refuting the models discussed herein will undoubtedly increase our knowledge and generate discussions to help with future clinical applications rather than engendering unproductive controversy. Even the more skeptical researchers should be attracted to challenge these models and bring their own points of view to fuel progress in the field.

Funding

Research reported in this publication was supported by the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID) of the NIH under award numbers R01AI114362 and R33AI116222, and Welch Foundation grant number I-1782 (to I.D.).

Acknowledgments

We thank members of the D’Orso lab (Emily Cruz-Lorenzo, Jinli Wang, and Usman Hyder) and Holly Ruess for critical reading of the manuscript.

Conflicts of Interest

No conflicts to declare

References

- Perelson, A.S.; Essunger, P.; Cao, Y.; Vesanen, M.; Hurley, A.; Saksela, K.; Markowitz, M.; Ho, D.D. Decay characteristics of HIV-1-infected compartments during combination therapy. Nature 1997, 387, 188–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sengupta, S.; Siliciano, R.F. Targeting the Latent Reservoir for HIV-1. Immunity 2018, 48, 872–895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Davey, R.T.; Bhat, N.; Yoder, C.; Chun, T.W.; Metcalf, J.A.; Dewar, R.; Natarajan, V.; Lempicki, R.A.; Adelsberger, J.W.; Miller, K.D.; et al. HIV-1 and T cell dynamics after interruption of highly active antiretroviral therapy (HAART) in patients with a history of sustained viral suppression. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1999, 96, 15109–15114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chun, T.W.; Carruth, L.; Finzi, D.; Shen, X.; DiGiuseppe, J.A.; Taylor, H.; Hermankova, M.; Chadwick, K.; Margolick, J.; Quinn, T.C.; et al. Quantification of latent tissue reservoirs and total body viral load in HIV-1 infection. Nature 1997, 387, 183–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chun, T.W.; Finzi, D.; Margolick, J.; Chadwick, K.; Schwartz, D.; Siliciano, R.F. In vivo fate of HIV-1-infected T cells: Quantitative analysis of the transition to stable latency. Nat. Med. 1995, 1, 1284–1290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chun, T.W.; Engel, D.; Berrey, M.M.; Shea, T.; Corey, L.; Fauci, A.S. Early establishment of a pool of latently infected, resting CD4+ T cells during primary HIV-1 infection. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1998, 95, 8869–8873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siliciano, J.D.; Kajdas, J.; Finzi, D.; Quinn, T.C.; Chadwick, K.; Margolick, J.B.; Kovacs, C.; Gange, S.J.; Siliciano, R.F. Long-term follow-up studies confirm the stability of the latent reservoir for HIV-1 in resting CD4+ T cells. Nat. Med. 2003, 9, 727–728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ho, Y.C.; Shan, L.; Hosmane, N.N.; Wang, J.; Laskey, S.B.; Rosenbloom, D.I.S.; Lai, J.; Blankson, J.N.; Siliciano, J.D.; Siliciano, R.F. XReplication-competent noninduced proviruses in the latent reservoir increase barrier to HIV-1 cure. Cell 2013, 155, 540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bruner, K.M.; Murray, A.J.; Pollack, R.A.; Soliman, M.G.; Laskey, S.B.; Capoferri, A.A.; Lai, J.; Strain, M.C.; Lada, S.M.; Hoh, R.; et al. Defective proviruses rapidly accumulate during acute HIV-1 infection. Nat. Med. 2016, 22, 1043–1049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Imamichia, H.; Dewar, R.L.; Adelsberger, J.W.; Rehm, C.A.; O’doherty, U.; Paxinos, E.E.; Fauci, A.S.; Lane, H.C. Defective HIV-1 proviruses produce novel proteincoding RNA species in HIV-infected patients on combination antiretroviral therapy. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2016, 113, 8783–8788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hiener, B.; Horsburgh, B.A.; Eden, J.S.; Barton, K.; Schlub, T.E.; Lee, E.; von Stockenstrom, S.; Odevall, L.; Milush, J.M.; Liegler, T.; et al. Identification of Genetically Intact HIV-1 Proviruses in Specific CD4+ T Cells from Effectively Treated Participants. Cell Rep. 2017, 21, 813–822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, G.Q.; Orlova-Fink, N.; Einkauf, K.; Chowdhury, F.Z.; Sun, X.; Harrington, S.; Kuo, H.H.; Hua, S.; Chen, H.R.; Ouyang, Z.; et al. Clonal expansion of genome-intact HIV-1 in functionally polarized Th1 CD4+ T cells. J. Clin. Investig. 2017, 127, 2689–2696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pollack, R.A.; Jones, R.B.; Pertea, M.; Bruner, K.M.; Martin, A.R.; Thomas, A.S.; Capoferri, A.A.; Beg, S.A.; Huang, S.H.; Karandish, S.; et al. Defective HIV-1 Proviruses Are Expressed and Can Be Recognized by Cytotoxic T Lymphocytes, which Shape the Proviral Landscape. Cell Host Microbe 2017, 21, 494–506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Siliciano, J.D.; Siliciano, R.F. Enhanced culture assay for detection and quantitation of latently infected, resting CD4+ T-cells carrying replication-competent virus in HIV-1-infected individuals. Methods Mol. Biol. 2005, 304, 3–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Laird, G.M.; Rosenbloom, D.I.S.; Lai, J.; Siliciano, R.F.; Siliciano, J.D. Measuring the frequency of latent HIV-1 in resting CD4+ T cells using a limiting dilution coculture assay. Methods Mol. Biol. 2016, 1354, 239–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Finzi, D.; Blankson, J.; Siliciano, J.D.; Margolick, J.B.; Chadwick, K.; Pierson, T.; Smith, K.; Lisziewicz, J.; Lori, F.; Flexner, C.; et al. Latent infection of CD4+ T cells provides a mechanism for lifelong persistence of HIV-1, even in patients on effective combination therapy. Nat. Med. 1999, 5, 512–517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strain, M.C.; Günthard, H.F.; Havlir, D.V.; Ignacio, C.C.; Smith, D.M.; Leigh-Brown, A.J.; Macaranas, T.R.; Lam, R.Y.; Daly, O.A.; Fischer, M.; et al. Heterogeneous clearance rates of long-lived lymphocytes infected with HIV: Intrinsic stability predicts lifelong persistence. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2003, 100, 4819–4824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crooks, A.M.; Bateson, R.; Cope, A.B.; Dahl, N.P.; Griggs, M.K.; Kuruc, J.D.; Gay, C.L.; Eron, J.J.; Margolis, D.M.; Bosch, R.J.; et al. Precise Quantitation of the Latent HIV-1 Reservoir: Implications for Eradication Strategies. J. Infect. Dis. 2015, 212, 1361–1365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bruner, K.M.; Wang, Z.; Simonetti, F.R.; Bender, A.M.; Kwon, K.J.; Sengupta, S.; Fray, E.J.; Beg, S.A.; Antar, A.A.R.; Jenike, K.M.; et al. A quantitative approach for measuring the reservoir of latent HIV-1 proviruses. Nature 2019, 566, 120–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hosmane, N.N.; Kwon, K.J.; Bruner, K.M.; Capoferri, A.A.; Beg, S.; Rosenbloom, D.I.S.; Keele, B.F.; Ho, Y.C.; Siliciano, J.D.; Siliciano, R.F. Proliferation of latently infected CD4+ T cells carrying replication-competent HIV-1: Potential role in latent reservoir dynamics. J. Exp. Med. 2017, 214, 959–972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohn, L.B.; Silva, I.T.; Oliveira, T.Y.; Rosales, R.A.; Parrish, E.H.; Learn, G.H.; Hahn, B.H.; Czartoski, J.L.; McElrath, M.J.; Lehmann, C.; et al. HIV-1 integration landscape during latent and active infection. Cell 2015, 160, 420–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Garcia-Broncano, P.; Maddali, S.; Einkauf, K.B.; Jiang, C.; Gao, C.; Chevalier, J.; Chowdhury, F.Z.; Maswabi, K.; Ajibola, G.; Moyo, S.; et al. Early antiretroviral therapy in neonates with HIV-1 infection restricts viral reservoir size and induces a distinct innate immune profile. Sci. Transl. Med. 2019, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Einkauf, K.B.; Lee, G.Q.; Gao, C.; Sharaf, R.; Sun, X.; Hua, S.; Chen, S.M.; Jiang, C.; Lian, X.; Chowdhury, F.Z.; et al. Intact HIV-1 proviruses accumulate at distinct chromosomal positions during prolonged antiretroviral therapy. J. Clin. Investig. 2019, 129, 988–998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abrahams, M.R.; Joseph, S.B.; Garrett, N.; Tyers, L.; Moeser, M.; Archin, N.; Council, O.D.; Matten, D.; Zhou, S.; Doolabh, D.; et al. The replication-competent HIV-1 latent reservoir is primarily established near the time of therapy initiation. Sci. Transl. Med. 2019, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maldarelli, F.; Wu, X.; Su, L.; Simonetti, F.R.; Shao, W.; Hill, S.; Spindler, J.; Ferris, A.L.; Mellors, J.W.; Kearney, M.F.; et al. HIV latency. Specific HIV integration sites are linked to clonal expansion and persistence of infected cells. Science 2014, 345, 179–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Simonetti, F.R.; Sobolewski, M.D.; Fyne, E.; Shao, W.; Spindler, J.; Hattori, J.; Anderson, E.M.; Watters, S.A.; Hill, S.; Wu, X.; et al. Clonally expanded CD4+ T cells can produce infectious HIV-1 in vivo. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2016, 113, 1883–1888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bui, J.K.; Sobolewski, M.D.; Keele, B.F.; Spindler, J.; Musick, A.; Wiegand, A.; Luke, B.T.; Shao, W.; Hughes, S.H.; Coffin, J.M.; et al. Proviruses with identical sequences comprise a large fraction of the replication-competent HIV reservoir. PLoS Pathog. 2017, 13, e1006283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lorenzi, J.C.C.; Cohen, Y.Z.; Cohn, L.B.; Kreider, E.F.; Barton, J.P.; Learn, G.H.; Oliveira, T.; Lavine, C.L.; Horwitz, J.A.; Settler, A.; et al. Paired quantitative and qualitative assessment of the replication-competent HIV-1 reservoir and comparison with integrated proviral DNA. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2016, 113, E7908–E7916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chomont, N.; El-Far, M.; Ancuta, P.; Trautmann, L.; Procopio, F.A.; Yassine-Diab, B.; Boucher, G.; Boulassel, M.R.; Ghattas, G.; Brenchley, J.M.; et al. HIV reservoir size and persistence are driven by T cell survival and homeostatic proliferation. Nat. Med. 2009, 15, 893–900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Gurule, E.E.; Brennan, T.P.; Gerold, J.M.; Kwon, K.J.; Hosmane, N.N.; Kumar, M.R.; Beg, S.A.; Capoferri, A.A.; Ray, S.C.; et al. Expanded cellular clones carrying replication-competent HIV-1 persist, wax, and wane. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2018, 115, E2575–E2584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zerbato, J.M.; Serrao, E.; Lenzi, G.; Kim, B.; Ambrose, Z.; Watkins, S.C.; Engelman, A.N.; Sluis-Cremer, N. Establishment and Reversal of HIV-1 Latency in Naive and Central Memory CD4+ T Cells In Vitro. J. Virol. 2016, 90, 8059–8073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dobrowolski, C.; Valadkhan, S.; Graham, A.C.; Shukla, M.; Ciuffi, A.; Telenti, A.; Karn, J. Entry of Polarized Effector Cells into Quiescence Forces HIV Latency. mBio 2019, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Agosto, L.M.; Henderson, A.J. CD4(+) T Cell Subsets and Pathways to HIV Latency. Aids. Res. Hum. Retrovir. 2018, 34, 780–789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Agosto, L.M.; Herring, M.B.; Mothes, W.; Henderson, A.J. HIV-1-Infected CD4+ T Cells Facilitate Latent Infection of Resting CD4+ T Cells through Cell-Cell Contact. Cell Rep. 2018, 24, 2088–2100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shan, L.; Deng, K.; Gao, H.; Xing, S.; Capoferri, A.A.; Durand, C.M.; Rabi, S.A.; Laird, G.M.; Kim, M.; Hosmane, N.N.; et al. Transcriptional Reprogramming during Effector-to-Memory Transition Renders CD4(+) T Cells Permissive for Latent HIV-1 Infection. Immunity 2017, 47, 766–775.e3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Julg, B.; Barouch, D.H. HIV-1 Latency by Transition. Immunity 2017, 47, 611–612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Chavez, L.; Calvanese, V.; Verdin, E. HIV Latency Is Established Directly and Early in Both Resting and Activated Primary CD4 T Cells. PLoS Pathog. 2015, 11, e1004955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lenasi, T.; Contreras, X.; Peterlin, B.M. Transcriptional interference antagonizes proviral gene expression to promote HIV latency. Cell Host Microbe 2008, 4, 123–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gallastegui, E.; Millan-Zambrano, G.; Terme, J.-M.; Chavez, S.; Jordan, A. Chromatin Reassembly Factors Are Involved in Transcriptional Interference Promoting HIV Latency. J. Virol. 2011, 85, 3187–3202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verdin, E.; Paras, P.; Van Lint, C. Chromatin disruption in the promoter of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 during transcriptional activation. EMBO J. 1993, 12, 3249–3259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Lint, C.; Emiliani, S.; Ott, M.; Verdin, E. Transcriptional activation and chromatin remodeling of the HIV-1 promoter in response to histone acetylation. EMBO J. 1996, 15, 1112–1120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kauder, S.E.; Bosque, A.; Lindqvist, A.; Planelles, V.; Verdin, E. Epigenetic regulation of HIV-1 latency by cytosine methylation. PLoS Pathog. 2009, 5, e1000495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Coull, J.J.; Romerio, F.; Sun, J.-M.; Volker, J.L.; Galvin, K.M.; Davie, J.R.; Shi, Y.; Hansen, U.; Margolis, D.M. The Human Factors YY1 and LSF Repress the Human Immunodeficiency Virus Type 1 Long Terminal Repeat via Recruitment of Histone Deacetylase 1. J. Virol. 2000, 74, 6790–6799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hsia, S.-C.V.; Shi, Y.-B. Chromatin Disruption and Histone Acetylation in Regulation of the Human Immunodeficiency Virus Type 1 Long Terminal Repeat by Thyroid Hormone Receptor. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2002, 22, 4043–4052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chan, J.K.; Greene, W.C. NF-kappaB/Rel: Agonist and antagonist roles in HIV-1 latency. Curr. Opin. HIV Aids 2011, 6, 12–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Williams, S.A.; Chen, L.F.; Kwon, H.; Ruiz-Jarabo, C.M.; Verdin, E.; Greene, W.C. NF-κB p50 promotes HIV latency through HDAC recruitment and repression of transcriptional initiation. EMBO J. 2006, 25, 139–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Razooky, B.S.; Pai, A.; Aull, K.; Rouzine, I.M.; Weinberger, L.S. A hardwired HIV latency program. Cell 2015, 160, 990–1001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fauci, A.S.; Redfield, R.R.; Sigounas, G.; Weahkee, M.D.; Giroir, B.P. Ending the HIV Epidemic: A Plan for the United States. JAMA 2019, 321, 844–845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mbonye, U.; Karn, J. Control of HIV latency by epigenetic and non-epigenetic mechanisms. Curr. Hiv Res. 2011, 9, 554–567. [Google Scholar]

- Transcriptional control of HIV latency: Cellular signaling pathways, epigenetics, happenstance and the hope for a cure. Virology 2014, 454–455, 328–339. [CrossRef]

- Mbonye, U.; Karn, J. The Molecular Basis for Human Immunodeficiency Virus Latency. Annu. Rev. Virol. 2017, 4, 261–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hughes, S.H.; Coffin, J.M. What Integration Sites Tell Us about HIV Persistence. Cell Host Microbe 2016, 19, 588–598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Michieletto, D.; Lusic, M.; Marenduzzo, D.; Orlandini, E. Physical principles of retroviral integration in the human genome. Nat. Commun. 2019, 10, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Han, Y.; Lin, Y.B.; An, W.; Xu, J.; Yang, H.C.; O’Connell, K.; Dordai, D.; Boeke, J.D.; Siliciano, J.D.; Siliciano, R.F. Orientation-Dependent Regulation of Integrated HIV-1 Expression by Host Gene Transcriptional Readthrough. Cell Host Microbe 2008, 4, 134–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schröder, A.R.W.; Shinn, P.; Chen, H.; Berry, C.; Ecker, J.R.; Bushman, F. HIV-1 Integration in the Human Genome Favors Active Genes and Local Hotspots. Cell 2002, 110, 521–529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, Y.; Lassen, K.; Monie, D.; Sedaghat, A.R.; Shimoji, S.; Liu, X.; Pierson, T.C.; Margolick, J.B.; Siliciano, R.F.; Siliciano, J.D. Resting CD4+ T Cells from Human Immunodeficiency Virus Type 1 (HIV-1)-Infected Individuals Carry Integrated HIV-1 Genomes within Actively Transcribed Host Genes. J. Virol. 2004, 78, 6122–6133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marini, B.; Kertesz-Farkas, A.; Ali, H.; Lucic, B.; Lisek, K.; Manganaro, L.; Pongor, S.; Luzzati, R.; Recchia, A.; Mavilio, F.; et al. Nuclear architecture dictates HIV-1 integration site selection. Nature 2015, 521, 227–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lucic, B.; Chen, H.C.; Kuzman, M.; Zorita, E.; Wegner, J.; Minneker, V.; Wang, W.; Fronza, R.; Laufs, S.; Schmidt, M.; et al. Spatially clustered loci with multiple enhancers are frequent targets of HIV-1 integration. Nat. Commun. 2019, 10, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, R.W.; Mamede, J.I.; Hope, T.J. Impact of Nucleoporin-Mediated Chromatin Localization and Nuclear Architecture on HIV Integration Site Selection. J. Virol. 2015, 89, 9702–9705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Kane, M.; Rebensburg, S.V.; Takata, M.A.; Zang, T.M.; Yamashita, M.; Kvaratskhelia, M.; Bieniasz, P.D. Nuclear pore heterogeneity influences HIV-1 infection and the antiviral activity of MX2. eLlife 2018, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lusic, M.; Siliciano, R.F. Nuclear landscape of HIV-1 infection and integration. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2017, 15, 69–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anderson, E.M.; Maldarelli, F. The role of integration and clonal expansion in HIV infection: Live long and prosper. Retrovirology 2018, 15, 71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dekker, J.; Mirny, L. The 3D Genome as Moderator of Chromosomal Communication. Cell 2016, 164, 1110–1121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yu, M.; Ren, B. The Three-Dimensional Organization of Mammalian Genomes. Annu. Rev. Cell Dev. Biol. 2017, 33, 265–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meaburn, K.J.; Misteli, T. Cell biology: Chromosome territories. Nature 2007, 445, 379–781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lieberman-Aiden, E.; van Berkum, N.L.; Williams, L.; Imakaev, M.; Ragoczy, T.; Telling, A.; Amit, I.; Lajoie, B.R.; Sabo, P.J.; Dorschner, M.O.; et al. Comprehensive mapping of long-range interactions reveals folding principles of the human genome. Science 2009, 326, 289–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rao, S.S.P.; Huntley, M.H.; Durand, N.C.; Stamenova, E.K.; Bochkov, I.D.; Robinson, J.T.; Sanborn, A.L.; Machol, I.; Omer, A.D.; Lander, E.S.; et al. A 3D map of the human genome at kilobase resolution reveals principles of chromatin looping. Cell 2014, 159, 1665–1680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whyte, W.A.; Orlando, D.A.; Hnisz, D.; Abraham, B.J.; Lin, C.Y.; Kagey, M.H.; Rahl, P.B.; Lee, T.I.; Young, R.A. Master transcription factors and mediator establish super-enhancers at key cell identity genes. Cell 2013, 153, 307–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dixon, J.R.; Selvaraj, S.; Yue, F.; Kim, A.; Li, Y.; Shen, Y.; Hu, M.; Liu, J.S.; Ren, B. Topological domains in mammalian genomes identified by analysis of chromatin interactions. Nature 2012, 485, 376–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bukrinsky, M.I.; Stanwick, T.L.; Dempsey, M.P.; Stevenson, M. Quiescent T lymphocytes as an inducible virus reservoir in HIV-1 infection. Science 1991, 254, 423–427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jordan, A.; Defechereux, P.; Verdin, E. The site of HIV-1 integration in the human genome determines basal transcriptional activity and response to Tat transactivation. EMBO J. 2001, 20, 1726–1738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sherrill-Mix, S.; Lewinski, M.K.; Famiglietti, M.; Bosque, A.; Malani, N.; Ocwieja, K.E.; Berry, C.C.; Looney, D.; Shan, L.; Agosto, L.M.; et al. HIV latency and integration site placement in five cell-based models. Retrovirology 2013, 10, 90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wagner, T.A.; McLaughlin, S.; Garg, K.; Cheung, C.Y.K.; Larsen, B.B.; Styrchak, S.; Huang, H.C.; Edlefsen, P.T.; Mullins, J.I.; Frenkel, L.M. Proliferation of cells with HIV integrated into cancer genes contributes to persistent infection. Science 2014, 345, 570–573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chuong, E.B.; Elde, N.C.; Feschotte, C. Regulatory activities of transposable elements: From conflicts to benefits. Nat. Rev. Genet. 2017, 18, 71–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruess, H.; Lee, J.; Guzman, C.; Malladi, V.; D’Orso, I. An integrated genomics approach towards deciphering human genome codes shaping HIV-1 proviral transcription and fate. bioRxiv 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Emiliani, S.; Fischle, W.; Ott, M.; Van Lint, C.; Amella, C.A.; Verdin, E. Mutations in the tat Gene Are Responsible for Human Immunodeficiency Virus Type 1 Postintegration Latency in the U1 Cell Line. J. Virol. 1998, 72, 1666–1670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Emiliani, S.; Van Lint, C.; Fischle, W.; Paras, P.; Ott, M.; Brady, J.; Verdin, E. A point mutation in the HIV-1 Tat responsive element is associated with postintegration latency. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1996, 93, 6377–6381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feinberg, M.B.; Baltimore, D.; Frankel, A.D. The role of Tat in the human immunodeficiency virus life cycle indicates a primary effect on transcriptional elongation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1991, 88, 4045–4049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nabel, G.; Baltimore, D. An inducible transcription factor activates expression of human immunodeficiency virus in T cells. Nature 1987, 326, 711–713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pache, L.; Dutra, M.S.; Spivak, A.M.; Marlett, J.M.; Murry, J.P.; Hwang, Y.; Maestre, A.M.; Manganaro, L.; Vamos, M.; Teriete, P.; et al. BIRC2/cIAP1 Is a Negative Regulator of HIV-1 Transcription and Can Be Targeted by Smac Mimetics to Promote Reversal of Viral Latency. Cell Host Microbe 2015, 18, 345–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kinoshita, S.; Su, L.; Amano, M.; Timmerman, L.A.; Kaneshima, H.; Nolan, G.P. The T cell activation factor NF-ATc positively regulates HIV-1 replication and gene expression in T cells. Immunity 1997, 6, 235–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morton, E.L.; Forst, C.V.; Zheng, Y.; DePaula-Silva, A.B.; Ramirez, N.G.P.; Planelles, V.; D’Orso, I. Transcriptional Circuit Fragility Influences HIV Proviral Fate. Cell Rep. 2019, 27, 154–171.e9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weinberger, L.S.; Burnett, J.C.; Toettcher, J.E.; Arkin, A.P.; Schaffer, D.V. Stochastic Gene Expression in a Lentiviral Positive-Feedback Loop: HIV-1 Tat Fluctuations Drive Phenotypic Diversity. Cell 2005, 122, 169–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Singh, A.; Razooky, B.; Cox, C.D.; Simpson, M.L.; Weinberger, L.S. Transcriptional Bursting from the HIV-1 Promoter Is a Significant Source of Stochastic Noise in HIV-1 Gene Expression. Biophys. J. 2010, 98, L32–L34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Razooky, B.S.; Weinberger, L.S. Mapping the architecture of the HIV-1 Tat circuit: A decision-making circuit that lacks bistability and exploits stochastic noise. Methods 2011, 53, 68–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Rouzine, I.M.; Razooky, B.S.; Weinberger, L.S. Stochastic variability in HIV affects viral eradication. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2014, 111, 13251–13252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jordan, A.; Bisgrove, D.; Verdin, E. HIV reproducibly establishes a latent infection after acute infection of T cells in vitro. EMBO J. 2003, 22, 1868–1877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lassen, K.G.; Hebbeler, A.M.; Bhattacharyya, D.; Lobritz, M.A.; Greene, W.C. A Flexible Model of HIV-1 Latency Permitting Evaluation of Many Primary CD4 T-Cell Reservoirs. PLoS ONE 2012, 7, e30176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cillo, A.R.; Sobolewski, M.D.; Bosch, R.J.; Fyne, E.; Piatak, M.; Coffin, J.M.; Mellors, J.W. Quantification of HIV-1 latency reversal in resting CD4+ T cells from patients on suppressive antiretroviral therapy. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2014, 111, 7078–7083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Golumbeanu, M.; Cristinelli, S.; Rato, S.; Munoz, M.; Cavassini, M.; Beerenwinkel, N.; Ciuffi, A. Single-Cell RNA-Seq Reveals Transcriptional Heterogeneity in Latent and Reactivated HIV-Infected Cells. Cell Rep. 2018, 23, 942–950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siliciano, R.F.; Greene, W.C. HIV latency. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Med. 2011, 1, a007096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Klaver, B.; Berkhout, B. Comparison of 5′ and 3′ long terminal repeat promoter function in human immunodeficiency virus. J. Virol. 1994, 68, 3830–3840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cullen, B.R.; Lomedico, P.T.; Ju, G. Transcriptional interference in avian retroviruses—implications for the promoter insertion model of leukaemogenesis. Nature 1984, 307, 241–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, Y. HIV-1 gene expression: Lessons from provirus and non-integrated DNA. Retrovirology 2004, 1, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delannoy, A.; Poirier, M.; Bell, B. Cat and Mouse: HIV Transcription in Latency, Immune Evasion and Cure/Remission Strategies. Viruses 2019, 11, 269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taube, R.; Peterlin, M. Lost in transcription: Molecular mechanisms that control HIV latency. Viruses 2013, 5, 902–927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pereira, L.A. A compilation of cellular transcription factor interactions with the HIV-1 LTR promoter. Nucleic Acids Res. 2000, 28, 663–668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mousseau, G.; Valente, S.T. Role of Host Factors on the Regulation of Tat-Mediated HIV-1 Transcription. Curr. Pharm. Des. 2017, 23, 4079–4090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, K.; Kadonaga, J.; Luciw, P.; Tjian, R. Activation of the AIDS retrovirus promoter by the cellular transcription factor, Sp1. Science 1986, 232, 755–759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garcia, J.A.; Harrich, D.; Soultanakis, E.; Wu, F.; Mitsuyasu, R.; Gaynor, R.B. Human immunodeficiency virus type 1 LTR TATA and TAR region sequences required for transcriptional regulation. EMBO J. 1989, 8, 765–778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rittner, K.; Churcher, M.J.; Gait, M.J.; Karn, J. The Human Immunodeficiency Virus Long Terminal Repeat Includes a Specialised Initiator Element which is Required for Tat-responsive Transcription. J. Mol. Biol. 1995, 248, 562–580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xiao, H.; Lis, J.T.; Jeang, K.T. Promoter activity of Tat at steps subsequent to TATA-binding protein recruitment. Mol. Cell. Biol. 1997, 17, 6898–6905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Perkins, N.D.; Edwards, N.L.; Duckett, C.S.; Agranoff, A.B.; Schmid, R.M.; Nabel, G.J. A cooperative interaction between NF-kappa B and Sp1 is required for HIV-1 enhancer activation. EMBO J. 1993, 12, 3551–3558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Perkins, N.D.; Agranoff, A.B.; Pascal, E.; Nabel, G.J. An interaction between the DNA-binding domains of RelA(p65) and Sp1 mediates human immunodeficiency virus gene activation. Mol. Cell. Biol. 1994, 14, 6570–6583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sif, S.; Gilmore, T.D. Interaction of the v-Rel oncoprotein with cellular transcription factor Sp1. J. Virol. 1994, 68, 7131–7138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bosque, A.; Planelles, V. Induction of HIV-1 latency and reactivation in primary memory CD4+ T cells. Blood 2009, 113, 58–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cron, R.Q.; Bartz, S.R.; Clausell, A.; Bort, S.J.; Klebanoff, S.J.; Lewis, D.B. NFAT1 Enhances HIV-1 Gene Expression in Primary Human CD4 T Cells. Clin. Immunol. 2000, 94, 179–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Y.K.; Mbonye, U.; Hokello, J.; Karn, J. T-Cell Receptor Signaling Enhances Transcriptional Elongation from Latent HIV Proviruses by Activating P-TEFb through an ERK-Dependent Pathway. J. Mol. Biol. 2011, 410, 896–916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, B.K.; Feinberg, M.B.; Baltimore, D. The kappaB sites in the human immunodeficiency virus type 1 long terminal repeat enhance virus replication yet are not absolutely required for viral growth. J. Virol. 1997, 71, 5495–5504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alcamí, J.; Laín de Lera, T.; Folgueira, L.; Pedraza, M.A.; Jacqué, J.M.; Bachelerie, F.; Noriega, A.R.; Hay, R.T.; Harrich, D.; Gaynor, R.B. Absolute dependence on kappa B responsive elements for initiation and Tat-mediated amplification of HIV transcription in blood CD4 T lymphocytes. EMBO J. 1995, 14, 1552–1560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tyagi, M.; Pearson, R.J.; Karn, J. Establishment of HIV Latency in Primary CD4+ Cells Is due to Epigenetic Transcriptional Silencing and P-TEFb Restriction. J. Virol. 2010, 84, 6425–6437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brooks, D.G.; Arlen, P.A.; Gao, L.; Kitchen, C.M.R.; Zack, J.A. Identification of T cell-signaling pathways that stimulate latent HIV in primary cells. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2003, 100, 12955–12960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Coiras, M.; López-Huertas, M.; Rullas, J.; Mittelbrunn, M.; Alcamí, J. Basal shuttle of NF-κB/IκBα in resting T lymphocytes regulates HIV-1 LTR dependent expression. Retrovirology 2007, 4, 56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ne, E.; Palstra, R.-J.; Mahmoudi, T. Transcription: Insights From the HIV-1 Promoter. Int. Rev. Cell Mol. Biol. 2018, 335, 191–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ruelas, D.S.; Greene, W.C. An Integrated Overview of HIV-1 Latency. Cell 2013, 155, 519–529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karin, M.; Liu, Z.; Zandi, E. AP-1 function and regulation. Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 1997, 9, 240–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, X.; Chen, Y.; Gabuzda, D. ERK MAP Kinase Links Cytokine Signals to Activation of Latent HIV-1 Infection by Stimulating a Cooperative Interaction of AP-1 and NF-κB. J. Biol. Chem. 1999, 274, 27981–27988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duverger, A.; Wolschendorf, F.; Zhang, M.; Wagner, F.; Hatcher, B.; Jones, J.; Cron, R.Q.; van der Sluis, R.M.; Jeeninga, R.E.; Berkhout, B.; et al. An AP-1 Binding Site in the Enhancer/Core Element of the HIV-1 Promoter Controls the Ability of HIV-1 To Establish Latent Infection. J. Virol. 2013, 87, 2264–2277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El Kharroubi, A.; Piras, G.; Zensen, R.; Martin, M.A. Transcriptional Activation of the Integrated Chromatin-Associated Human Immunodeficiency Virus Type 1 Promoter. Mol. Cell. Biol. 1998, 18, 2535–2544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olson, A.; Basukala, B.; Wong, W.W.; Henderson, A.J. Targeting HIV-1 proviral transcription. Curr. Opin. Virol. 2019, 38, 89–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muse, G.W.; Gilchrist, D.A.; Nechaev, S.; Shah, R.; Parker, J.S.; Grissom, S.F.; Zeitlinger, J.; Adelman, K. RNA polymerase is poised for activation across the genome. Nat. Genet. 2007, 39, 1507–1511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, F.X.; Smith, E.R.; Shilatifard, A. Born to run: Control of transcription elongation by RNA polymerase II. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2018, 19, 464–478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jadlowsky, J.K.; Wong, J.Y.; Graham, A.C.; Dobrowolski, C.; Devor, R.L.; Adams, M.D.; Fujinaga, K.; Karn, J. Negative Elongation Factor Is Required for the Maintenance of Proviral Latency but Does Not Induce Promoter-Proximal Pausing of RNA Polymerase II on the HIV Long Terminal Repeat. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2014, 34, 1911–1928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Klatt, A.; Gilmour, D.S.; Henderson, A.J. Negative elongation factor NELF represses human immunodeficiency virus transcription by pausing the RNA polymerase II complex. J. Biol. Chem. 2007, 282, 16981–16988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kao, S.Y.; Calman, A.F.; Luciw, P.A.; Peterlin, B.M. Anti-termination of transcription within the long terminal repeat of HIV-1 by tat gene product. Nature 1987, 330, 489–493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wada, T.; Takagi, T.; Yamaguchi, Y.; Ferdous, A.; Imai, T.; Hirose, S.; Sugimoto, S.; Yano, K.; Hartzog, G.A.; Winston, F.; et al. DSIF, a novel transcription elongation factor that regulates RNA polymerase II processivity, is composed of human Spt4 and Spt5 homologs. Genes Dev. 1998, 12, 343–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamaguchi, Y.; Wada, T.; Watanabe, D.; Takagi, T.; Hasegawa, J.; Handa, H. Structure and Function of the Human Transcription Elongation Factor DSIF. J. Biol. Chem. 1999, 274, 8085–8092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamaguchi, Y.; Takagi, T.; Wada, T.; Yano, K.; Furuya, A.; Sugimoto, S.; Hasegawa, J.; Handa, H. NELF, a Multisubunit Complex Containing RD, Cooperates with DSIF to Repress RNA Polymerase II Elongation. Cell 1999, 97, 41–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rao, J.N.; Neumann, L.; Wenzel, S.; Schweimer, K.; Rösch, P.; Wöhrl, B.M. Structural studies on the RNA-recognition motif of NELF E, a cellular negative transcription elongation factor involved in the regulation of HIV transcription. Biochem. J. 2006, 400, 449–456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pagano, J.M.; Kwak, H.; Waters, C.T.; Sprouse, R.O.; White, B.S.; Ozer, A.; Szeto, K.; Shalloway, D.; Craighead, H.G.; Lis, J.T. Defining NELF-E RNA Binding in HIV-1 and Promoter-Proximal Pause Regions. PLoS Genet. 2014, 10, e1004090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Narita, T.; Yamaguchi, Y.; Yano, K.; Sugimoto, S.; Chanarat, S.; Wada, T.; Kim, D.-K.; Hasegawa, J.; Omori, M.; Inukai, N.; et al. Human Transcription Elongation Factor NELF: Identification of Novel Subunits and Reconstitution of the Functionally Active Complex. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2003, 23, 1863–1873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gressel, S.; Schwalb, B.; Decker, T.M.; Qin, W.; Leonhardt, H.; Eick, D.; Cramer, P. CDK9-dependent RNA polymerase II pausing controls transcription initiation. eLife 2017, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shao, W.; Zeitlinger, J. Paused RNA polymerase II inhibits new transcriptional initiation. Nat. Genet. 2017, 49, 1045–1051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sathyan, K.M.; McKenna, B.D.; Anderson, W.D.; Duarte, F.M.; Core, L.; Guertin, M.J. An improved auxin-inducible degron system preserves native protein levels and enables rapid and specific protein depletion. Genes Dev. 2019, 33, 1441–1455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nabet, B.; Roberts, J.M.; Buckley, D.L.; Paulk, J.; Dastjerdi, S.; Yang, A.; Leggett, A.L.; Erb, M.A.; Lawlor, M.A.; Souza, A.; et al. The dTAG system for immediate and target-specific protein degradation. Nat. Chem. Biol. 2018, 14, 431–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Burslem, G.M.; Crews, C.M. Proteolysis-Targeting Chimeras as Therapeutics and Tools for Biological Discovery. Cell 2020, 181, 102–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aoi, Y.; Smith, E.R.; Shah, A.P.; Rendleman, E.J.; Marshall, S.A.; Woodfin, A.R.; Chen, F.X.; Shiekhattar, R.; Shilatifard, A. NELF Regulates a Promoter-Proximal Step Distinct from RNA Pol II Pause-Release. Mol. Cell 2020, 78, 261–274.e5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hartzog, G.A.; Basrai, M.A.; Ricupero-Hovasse, S.L.; Hieter, P.; Winston, F. Identification and analysis of a functional human homolog of the SPT4 gene of Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Mol. Cell. Biol. 1996, 16, 2848–2856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Glover-Cutter, K.; Kim, S.; Espinosa, J.; Bentley, D.L. RNA polymerase II pauses and associates with pre-mRNA processing factors at both ends of genes. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 2008, 15, 71–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gilchrist, D.A.; Dos Santos, G.; Fargo, D.C.; Xie, B.; Gao, Y.; Li, L.; Adelman, K. Pausing of RNA Polymerase II Disrupts DNA-Specified Nucleosome Organization to Enable Precise Gene Regulation. Cell 2010, 143, 540–551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Missra, A.; Gilmour, D.S. Interactions between DSIF (DRB sensitivity inducing factor), NELF (negative elongation factor), and the Drosophila RNA polymerase II transcription elongation complex. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2010, 107, 11301–11306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wen, Y.; Shatkin, A.J. Transcription elongation factor hSPT5 stimulates mRNA capping. Genes Dev. 1999, 13, 1774–1779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marciniak, R.A.; Sharp, P.A. HIV-1 Tat protein promotes formation of more-processive elongation complexes. EMBO J. 1991, 10, 4189–4196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Karn, J. The molecular biology of HIV latency: Breaking and restoring the Tat-dependent transcriptional circuit. Curr. Opin. HIV Aids 2011, 6, 4–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mancebo, H.S.Y.; Lee, G.; Flygare, J.; Tomassini, J.; Luu, P.; Zhu, Y.; Peng, J.; Blau, C.; Hazuda, D.; Price, D.; et al. P-TEFb kinase is required for HIV Tat transcriptional activation in vivo and in vitro. Genes Dev. 1997, 11, 2633–2644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhu, Y.; Pe’ery, T.; Peng, J.; Ramanathan, Y.; Marshall, N.; Marshall, T.; Amendt, B.; Mathews, M.B.; Price, D.H. Transcription elongation factor P-TEFb is required for HIV-1 Tat transactivation in vitro. Genes Dev. 1997, 11, 2622–2632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wei, P.; Garber, M.E.; Fang, S.M.; Fischer, W.H.; Jones, K.A. A novel CDK9-associated C-type cyclin interacts directly with HIV-1 Tat and mediates its high-affinity, loop-specific binding to TAR RNA. Cell 1998, 92, 451–462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fujinaga, K.; Irwin, D.; Huang, Y.; Taube, R.; Kurosu, T.; Peterlin, B.M. Dynamics of Human Immunodeficiency Virus Transcription: P-TEFb Phosphorylates RD and Dissociates Negative Effectors from the Transactivation Response Element. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2004, 24, 787–795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamada, T.; Yamaguchi, Y.; Inukai, N.; Okamoto, S.; Mura, T.; Handa, H. P-TEFb-Mediated Phosphorylation of hSpt5 C-Terminal Repeats Is Critical for Processive Transcription Elongation. Mol. Cell 2006, 21, 227–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bourgeois, C.F.; Kim, Y.K.; Churcher, M.J.; West, M.J.; Karn, J. Spt5 Cooperates with Human Immunodeficiency Virus Type 1 Tat by Preventing Premature RNA Release at Terminator Sequences. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2002, 22, 1079–1093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marshall, N.F.; Peng, J.; Xie, Z.; Price, D.H. Control of RNA Polymerase II Elongation Potential by a Novel Carboxyl-terminal Domain Kinase. J. Biol. Chem. 1996, 271, 27176–27183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ramanathan, Y.; Rajpara, S.M.; Reza, S.M.; Lees, E.; Shuman, S.; Mathews, M.B.; Pe’ery, T. Three RNA Polymerase II Carboxyl-terminal Domain Kinases Display Distinct Substrate Preferences. J. Biol. Chem. 2001, 276, 10913–10920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Komarnitsky, P.; Cho, E.J.; Buratowski, S. Different phosphorylated forms of RNA polymerase II and associated mRNA processing factors during transcription. Genes Dev. 2000, 14, 2452–2460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peterlin, B.M.; Price, D.H. Controlling the Elongation Phase of Transcription with P-TEFb. Mol. Cell 2006, 23, 297–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, Q.; Li, T.; Price, D.H. RNA polymerase II elongation control. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 2012, 81, 119–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, V.T.; Kiss, T.; Michels, A.A.; Bensaude, O. 7SK small nuclear RNA binds to and inhibits the activity of CDK9/cyclin T complexes. Nature 2001, 414, 322–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Z.; Zhu, Q.; Luo, K.; Zhou, Q. The 7SK small nuclear RNA inhibits the CDK9/cyclin T1 kinase to control transcription. Nature 2001, 414, 317–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, R.; Yang, Z.; Zhou, Q. Phosphorylated Positive Transcription Elongation Factor b (P-TEFb) Is Tagged for Inhibition through Association with 7SK snRNA. J. Biol. Chem. 2004, 279, 4153–4160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Q.; Price, J.P.; Byers, S.A.; Cheng, D.; Peng, J.; Price, D.H. Analysis of the Large Inactive P-TEFb Complex Indicates That It Contains One 7SK Molecule, a Dimer of HEXIM1 or HEXIM2, and Two P-TEFb Molecules Containing Cdk9 Phosphorylated at Threonine 186. J. Biol. Chem. 2005, 280, 28819–28826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xue, Y.; Yang, Z.; Chen, R.; Zhou, Q. A capping-independent function of MePCE in stabilizing 7SK snRNA and facilitating the assembly of 7SK snRNP. Nucleic Acids Res. 2010, 38, 360–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krueger, B.J.; Jeronimo, C.; Roy, B.B.; Bouchard, A.; Barrandon, C.; Byers, S.A.; Searcey, C.E.; Cooper, J.J.; Bensaude, O.; Cohen, E.A.; et al. LARP7 is a stable component of the 7SK snRNP while P-TEFb, HEXIM1 and hnRNP A1 are reversibly associated. Nucleic Acids Res. 2008, 36, 2219–2229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeronimo, C.; Forget, D.; Bouchard, A.; Li, Q.; Chua, G.; Poitras, C.; Thérien, C.; Bergeron, D.; Bourassa, S.; Greenblatt, J.; et al. Systematic Analysis of the Protein Interaction Network for the Human Transcription Machinery Reveals the Identity of the 7SK Capping Enzyme. Mol. Cell 2007, 27, 262–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, N.; Jahchan, N.S.; Hong, E.; Li, Q.; Bayfield, M.A.; Maraia, R.J.; Luo, K.; Zhou, Q. A La-Related Protein Modulates 7SK snRNP Integrity to Suppress P-TEFb-Dependent Transcriptional Elongation and Tumorigenesis. Mol. Cell 2008, 29, 588–599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bacon, C.W.; D’Orso, I. CDK9: A signaling hub for transcriptional control. Transcription 2019, 10, 57–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McNamara, R.P.; McCann, J.L.; Gudipaty, S.A.; D’Orso, I. Transcription factors mediate the enzymatic disassembly of promoter-bound 7SK snRNP to locally recruit P-TEFb for transcription elongation. Cell Rep. 2013, 5, 1256–1268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Faust, T.B.; Li, Y.; Bacon, C.W.; Jang, G.M.; Weiss, A.; Jayaraman, B.; Newton, B.W.; Krogan, N.J.; D’Orso, I.; Frankel, A.D. The HIV-1 Tat protein recruits a ubiquitin ligase to reorganize the 7SK snRNP for transcriptional activation. eLife 2018, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- D’Orso, I.; Frankel, A.D. RNA-mediated displacement of an inhibitory snRNP complex activates transcription elongation. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 2010, 17, 815–821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Orso, I.; Jang, G.M.; Pastuszak, A.W.; Faust, T.B.; Quezada, E.; Booth, D.S.; Frankel, A.D. Transition Step during Assembly of HIV Tat:P-TEFb Transcription Complexes and Transfer to TAR RNA. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2012, 32, 4780–4793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barboric, M.; Yik, J.H.N.; Czudnochowski, N.; Yang, Z.; Chen, R.; Contreras, X.; Geyer, M.; Matija Peterlin, B.; Zhou, Q. Tat competes with HEXIM1 to increase the active pool of P-TEFb for HIV-1 transcription. Nucleic Acids Res. 2007, 35, 2003–2012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sedore, S.C.; Byers, S.A.; Biglione, S.; Price, J.P.; Maury, W.J.; Price, D.H. Manipulation of P-TEFb control machinery by HIV: Recruitment of P-TEFb from the large form by Tat and binding of HEXIM1 to TAR. Nucleic Acids Res. 2007, 35, 4347–4358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Garber, M.E.; Mayall, T.P.; Suess, E.M.; Meisenhelder, J.; Thompson, N.E.; Jones, K.A. CDK9 Autophosphorylation Regulates High-Affinity Binding of the Human Immunodeficiency Virus Type 1 Tat-P-TEFb Complex to TAR RNA. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2000, 20, 6958–6969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jang, M.K.; Mochizuki, K.; Zhou, M.; Jeong, H.-S.; Brady, J.N.; Ozato, K. The Bromodomain Protein Brd4 Is a Positive Regulatory Component of P-TEFb and Stimulates RNA Polymerase II-Dependent Transcription. Mol. Cell 2005, 19, 523–534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, Z.; Yik, J.H.N.; Chen, R.; He, N.; Moon, K.J.; Ozato, K.; Zhou, Q. Recruitment of P-TEFb for stimulation of transcriptional elongation by the bromodomain protein Brd4. Mol. Cell 2005, 19, 535–545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- He, N.; Liu, M.; Hsu, J.; Xue, Y.; Chou, S.; Burlingame, A.; Krogan, N.J.; Alber, T.; Zhou, Q. HIV-1 Tat and Host AFF4 Recruit Two Transcription Elongation Factors into a Bifunctional Complex for Coordinated Activation of HIV-1 Transcription. Mol. Cell 2010, 38, 428–438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sobhian, B.; Laguette, N.; Yatim, A.; Nakamura, M.; Levy, Y.; Kiernan, R.; Benkirane, M. HIV-1 Tat Assembles a Multifunctional Transcription Elongation Complex and Stably Associates with the 7SK snRNP. Mol. Cell 2010, 38, 439–451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McNamara, R.P.; Reeder, J.E.; McMillan, E.A.; Bacon, C.W.; McCann, J.L.; D’Orso, I. KAP1 Recruitment of the 7SK snRNP Complex to Promoters Enables Transcription Elongation by RNA Polymerase II. Mol. Cell 2016, 61, 39–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, C.; Smith, E.R.; Takahashi, H.; Lai, K.C.; Martin-Brown, S.; Florens, L.; Washburn, M.P.; Conaway, J.W.; Conaway, R.C.; Shilatifard, A. AFF4, a Component of the ELL/P-TEFb Elongation Complex and a Shared Subunit of MLL Chimeras, Can Link Transcription Elongation to Leukemia. Mol. Cell 2010, 37, 429–437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chou, S.; Upton, H.; Bao, K.; Schulze-Gahmen, U.; Samelson, A.J.; He, N.; Nowak, A.; Lu, H.; Krogan, N.J.; Zhou, Q.; et al. HIV-1 Tat recruits transcription elongation factors dispersed along a flexible AFF4 scaffold. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2013, 110, E123–E131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, H.; Li, Z.; Xue, Y.; Schulze-Gahmen, U.; Johnson, J.R.; Krogan, N.J.; Alber, T.; Zhou, Q. AFF1 is a ubiquitous P-TEFb partner to enable Tat extraction of P-TEFb from 7SK snRNP and formation of SECs for HIV transactivation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2014, 111, E15–E24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, Z.; Lin, C.; Guest, E.; Garrett, A.S.; Mohaghegh, N.; Swanson, S.; Marshall, S.; Florens, L.; Washburn, M.P.; Shilatifard, A. The super elongation complex family of RNA polymerase II elongation factors: Gene target specificity and transcriptional output. Mol. Cell Biol. 2012, 32, 2608–2617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Lu, H.; Zhou, Q. A Minor Subset of Super Elongation Complexes Plays a Predominant Role in Reversing HIV-1 Latency. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2016, 36, 1194–1205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Filippakopoulos, P.; Qi, J.; Picaud, S.; Shen, Y.; Smith, W.B.; Fedorov, O.; Morse, E.M.; Keates, T.; Hickman, T.T.; Felletar, I.; et al. Selective inhibition of BET bromodomains. Nature 2010, 468, 1067–1073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dey, A.; Chitsaz, F.; Abbasi, A.; Misteli, T.; Ozato, K. The double bromodomain protein Brd4 binds to acetylated chromatin during interphase and mitosis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2003, 100, 8758–8763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boehm, D.; Calvanese, V.; Dar, R.D.; Xing, S.; Schroeder, S.; Martins, L.; Aull, K.; Li, P.-C.; Planelles, V.; Bradner, J.E.; et al. BET bromodomain-targeting compounds reactivate HIV from latency via a Tat-independent mechanism. Cell Cycle 2013, 12, 452–462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banerjee, C.; Archin, N.; Michaels, D.; Belkina, A.C.; Denis, G.V.; Bradner, J.; Sebastiani, P.; Margolis, D.M.; Montano, M. BET bromodomain inhibition as a novel strategy for reactivation of HIV-1. J. Leukoc. Biol. 2012, 92, 1147–1154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanno, T.; Kanno, Y.; LeRoy, G.; Campos, E.; Sun, H.-W.; Brooks, S.R.; Vahedi, G.; Heightman, T.D.; Garcia, B.A.; Reinberg, D.; et al. BRD4 assists elongation of both coding and enhancer RNAs by interacting with acetylated histones. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 2014, 21, 1047–1057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Winter, G.E.; Mayer, A.; Buckley, D.L.; Erb, M.A.; Roderick, J.E.; Vittori, S.; Reyes, J.M.; di Iulio, J.; Souza, A.; Ott, C.J.; et al. BET Bromodomain Proteins Function as Master Transcription Elongation Factors Independent of CDK9 Recruitment. Mol. Cell 2017, 67, 5–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Devaiah, B.N.; Lewis, B.A.; Cherman, N.; Hewitt, M.C.; Albrecht, B.K.; Robey, P.G.; Ozato, K.; Sims, R.J.; Singer, D.S. BRD4 is an atypical kinase that phosphorylates Serine2 of the RNA Polymerase II carboxy-terminal domain. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2012, 109, 6927–6932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, W.; Ma, Q.; Wong, K.; Li, W.; Ohgi, K.; Zhang, J.; Aggarwal, A.K.; Rosenfeld, M.G. Brd4 and JMJD6-Associated Anti-Pause Enhancers in Regulation of Transcriptional Pause Release. Cell 2013, 155, 1581–1595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Orso, I. 7SKiing on chromatin: Move globally, act locally. RNA Biol. 2016, 13, 545–553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolf, D.; Goff, S.P. TRIM28 mediates primer binding site-targeted silencing of murine leukemia virus in embryonic cells. Cell 2007, 131, 46–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rowe, H.M.; Jakobsson, J.; Mesnard, D.; Rougemont, J.; Reynard, S.; Aktas, T.; Maillard, P.V.; Layard-Liesching, H.; Verp, S.; Marquis, J.; et al. KAP1 controls endogenous retroviruses in embryonic stem cells. Nature 2010, 463, 237–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bacon, C.W.; Challa, A.; Hyder, U.; Shukla, A.; Borkar, A.N.; Bayo, J.; Liu, J.; Wu, S.Y.; Chiang, C.-M.; Kutateladze, T.G.; et al. A chromatin reader couples steps RNA polymerase II transcription to sustain oncogenic programs. Mol. Cell 2020, 78, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiang, C.; Pugh, B.F. Nucleosome positioning and gene regulation: Advances through genomics. Nat. Rev. Genet. 2009, 10, 161–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steger, D.J.; Workman, J.L. Stable co-occupancy of transcription factors and histones at the HIV-1 enhancer. EMBO J. 1997, 16, 2463–2472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rafati, H.; Parra, M.; Hakre, S.; Moshkin, Y.; Verdin, E.; Mahmoudi, T. Repressive LTR Nucleosome Positioning by the BAF Complex Is Required for HIV Latency. PLoS Biol. 2011, 9, e1001206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verdin, E.; Becker, N.; Bex, F.; Droogmans, L.; Burny, A. Identification and characterization of an enhancer in the coding region of the genome of human immunodeficiency virus type 1. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1990, 87, 4874–4878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bushnell, D.A.; Cramer, P.; Kornberg, R.D. Structural basis of transcription: -Amanitin-RNA polymerase II cocrystal at 2.8 A resolution. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2002, 99, 1218–1222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; Xue, Y.; Zhou, S.; Kuo, A.; Cairns, B.R.; Crabtree, G.R. Diversity and specialization of mammalian SWI/SNF complexes. Genes Dev. 1996, 10, 2117–2130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kadoch, C.; Crabtree, G.R. Mammalian SWI/SNF chromatin remodeling complexes and cancer: Mechanistic insights gained from human genomics. Sci. Adv. 2015, 1, e1500447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hodges, C.; Kirkland, J.G.; Crabtree, G.R. The Many Roles of BAF (mSWI/SNF) and PBAF Complexes in Cancer. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Med. 2016, 6, a026930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]