Topographic and Edaphic Drivers of Community Structure and Species Diversity in a Subtropical Deciduous Broad-Leaved Forest in Eastern China

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Area

2.2. Survey and Sampling Methods

2.3. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Basic Overview of Community Structure Characteristics, Species Diversity, Topography and Soil Properties

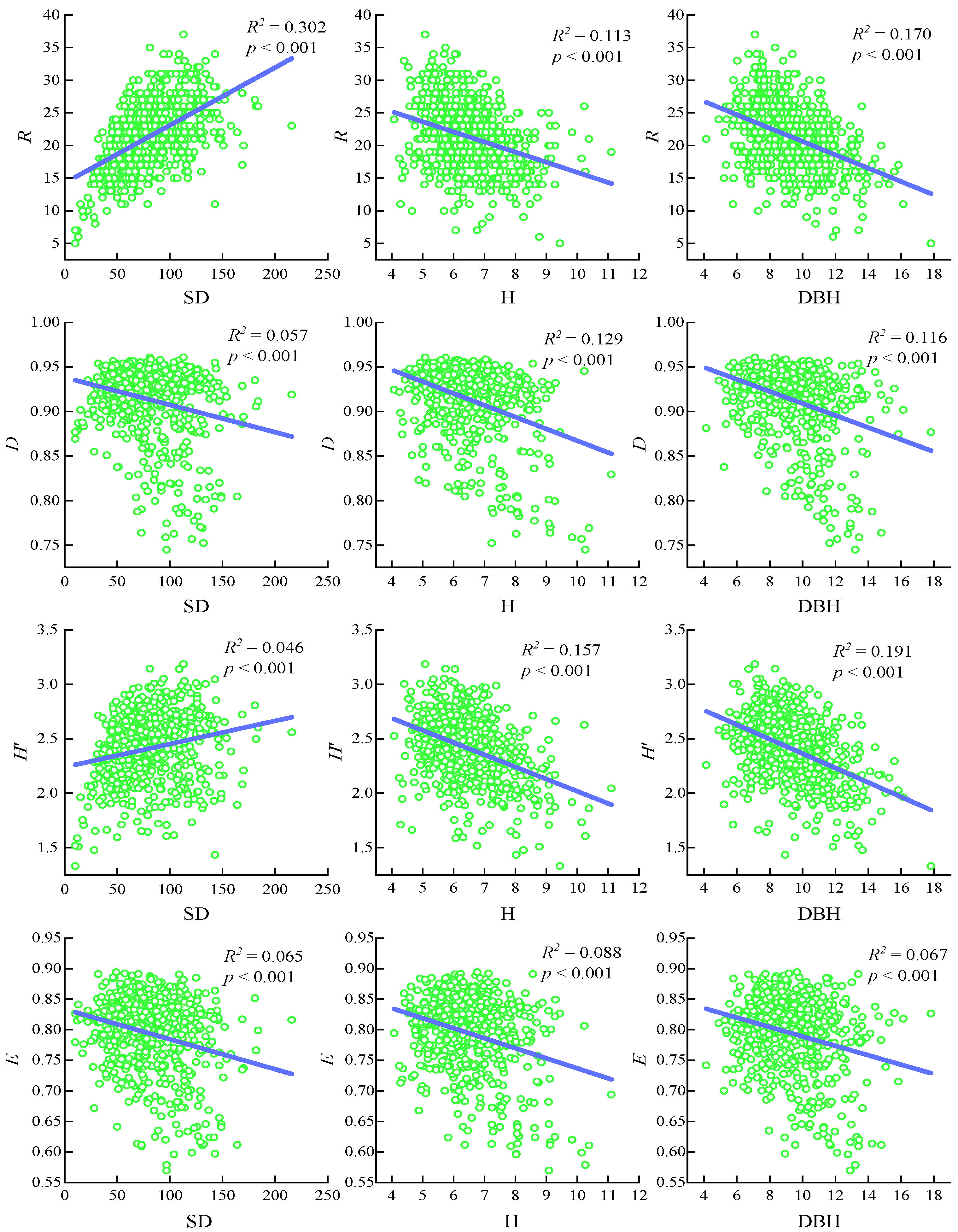

3.2. Relationship Between Community Structure Characteristics and Species Diversity in Tree Layer

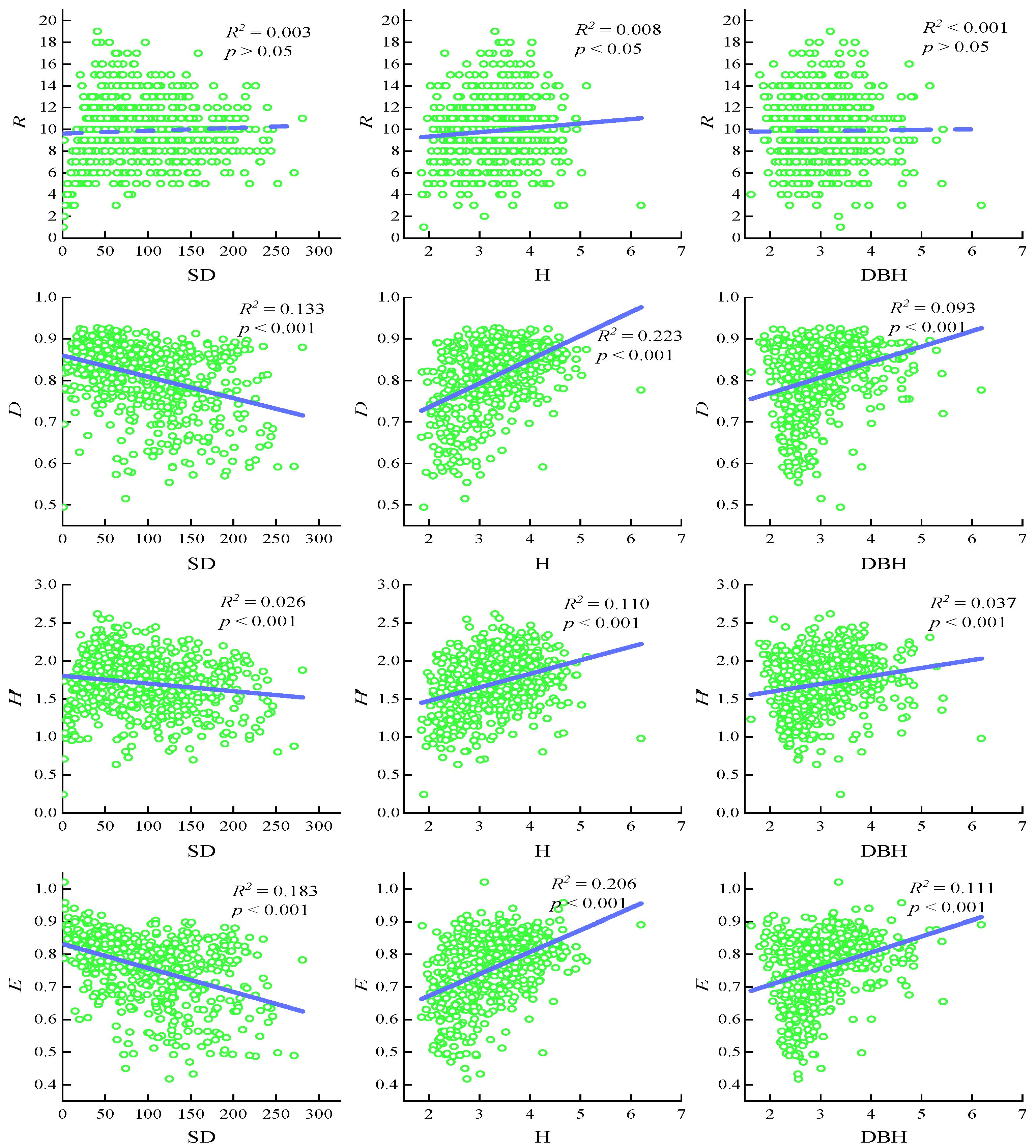

3.3. Relationship Between Community Structure Characteristics and Species Diversity in Shrub Layer

3.4. Relationship Between Tree Layer and Shrub Layer of Community Structure and Diversity

3.5. Relationship Between Topographic Factors and Soil Properties

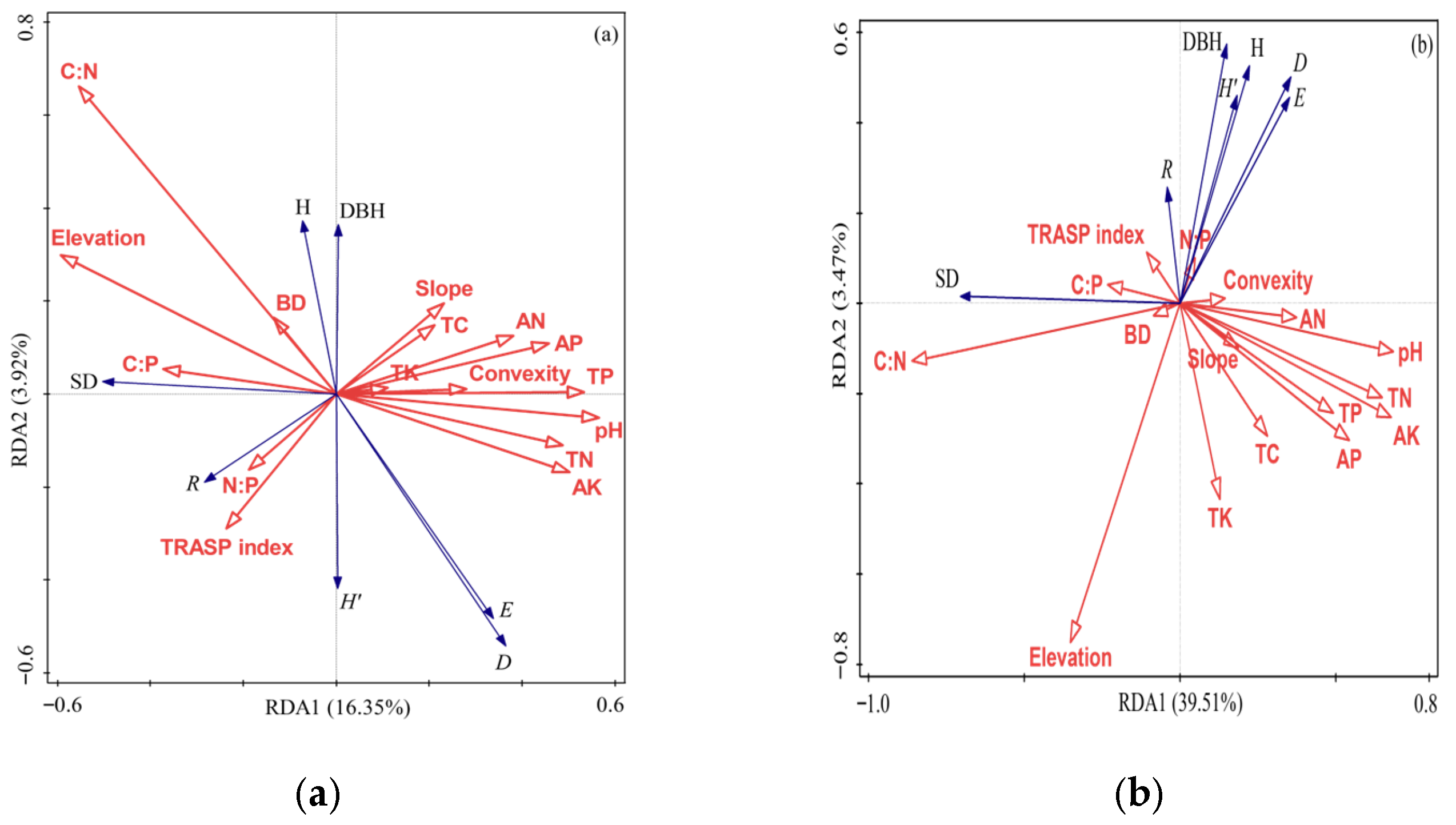

3.6. Relationships of Forest Community Structure and Diversity with Environmental Factors

4. Discussion

4.1. Effects of Forest Community Structure Characteristics on Diversity

4.2. Effects of Topographic Factors on Soil Environment

4.3. Response of Forest Community Structure and Diversity to Environmental Factors

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Aubert, M.; Margerie, P.; Trap, J.; Bureau, F. Aboveground-belowground relationships in temperate forests: Plant litter composes and microbiota orchestrates. For. Ecol. Manag. 2010, 259, 563–572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pomara, L.Y.; Ruokolainen, K.; Tuomisto, H.; Young, K.R. Avian Composition Co-varies with Floristic Composition and Soil Nutrient Concentration in Amazonian Upland Forests. Biotropica 2012, 44, 545–553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vergara-Tabares, D.L.; Cordier, J.M.; Landi, M.A.; Olah, G.; Nori, J. Global trends of habitat destruction and consequences for parrot conservation. Glob. Change Biol. 2020, 26, 4251–4262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Parron, L.M.; Bustamante, M.M.C.; Markewitz, D. Fluxes of nitrogen and phosphorus in a gallery forest in the Cerrado of Central Brazil. Biogeochemistry 2011, 105, 89–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qian, H.; White, P.S.; Song, J.S. Effects of regional vs. ecological factors on plant species richness: An intercontinental analysis. Ecology 2007, 88, 1440–1453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernandes, P.H.D.; de Souza, A.L.T.; Tanaka, M.O.; Sebastiani, R. Decomposition and stabilization of organic matter in an old-growth tropical riparian forest: Effects of soil properties and vegetation structure. For. Ecosyst. 2021, 8, 173–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wekesa, C.; Kirui, B.K.; Maranga, E.K.; Muturi, G.M. Variations in forest structure, tree species diversity and above-ground biomass in edges to interior cores of fragmented forest patches of Taita Hills, Kenya. For. Ecol. Manag. 2019, 440, 48–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mazón, M.M.; Klanderud, K.; Finegan, B.; Veintimilla, D.; Bermeo, D.; Murrieta, E.; Delgado, D.; Sheil, D. How forest structure varies with elevation in old growth and secondary forest in Costa Rica. For. Ecol. Manag. 2020, 469, 118191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bélanger, N.; Collin, A.; Ricard-Piché, J.; Kembel, S.W.; Rivest, D. Microsite conditions influence leaf litter decomposition in sugar maple bioclimatic domain of Quebec. Biogeochemistry 2019, 145, 107–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weintraub, S.R.; Taylor, P.G.; Porder, S.; Cleveland, C.C.; Asner, G.P.; Townsend, A.R. Topographic controls on soil nitrogen availability in a lowland tropical forest. Ecology 2015, 96, 1561–1574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chadwick, K.D.; Asner, G.P. Tropical soil nutrient distributions determined by biotic and hillslope processes. Biogeochemistry 2016, 127, 273–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, X.Y.; Duan, P.P.; Wang, K.L.; Li, D.J. Topography modulates effects of nitrogen deposition on soil nitrogen transformations by impacting soil properties in a subtropical forest. Geoderma 2023, 432, 116381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blonska, E.; Lasota, J.; Szuszkiewicz, M.; Lukasik, A.; Klamerus-Iwan, A. Assessment of forest soil contamination in Krakow surroundings in relation to the type of stand. Environ. Earth Sci. 2016, 75, 1205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tamme, R.; Hiiesalu, I.; Laanisto, L.; Szava-Kovats, R.; Pärtel, M. Environmental heterogeneity, species diversity and co-existence at different spatial scales. J. Veg. Sci. 2010, 21, 796–801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Černý, T.; Doležal, J.; Janeček, Š.; Šrůtek, M.; Valachovič, M.; Petřík, P.; Altman, J.; Bartoš, M.; Song, J.S. Environmental correlates of plant diversity in Korean temperate forests. Acta Oecol. 2013, 47, 37–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rossel, R.A.V.; Lee, J.; Behrens, T.; Luo, Z.; Baldock, J.; Richards, A. Continental-scale soil carbon composition and vulnerability modulated by regional environmental controls. Nat. Geosci. 2019, 12, 547–552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonzaga, A.P.D.; Machado, E.L.M.; Felfili, J.M.; Pinto, J.R.R. Brazilian Decidual Tropical Forest enclaves: Floristic, structural and environmental variations. Braz. J. Bot. 2017, 40, 417–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zolfaghari, R.; Fayyaz, P.; Jahantab, E.; Bergmeier, E. Habitat variation and vulnerability of Quercus brantii woodlands in the Zagros Mountains, Iran. Turk. J. Bot. 2021, 45, 688–700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scholten, T.; Goebes, P.; Kühn, P.; Seitz, S.; Assmann, T.; Bauhus, J.; Bruelheide, H.; Buscot, F.; Erfmeier, A.; Fischer, M.; et al. On the combined effect of soil fertility and topography on tree growth in subtropical forest ecosystems-a study from SE China. J. Plant Ecol. 2017, 1, 111–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Tan, C.; Xiong, W.; Wang, X.; Aierkaixi, D.; Fu, Q. Vascular plants in the tourist area of Lushan National Nature Reserve, China: Status, threats and conservation. Eco. Mont. 2020, 12, 60–63. [Google Scholar]

- Cheng, D.; Duan, Z.; Li, Q.; Liu, Z.; Yan, Y.; Zhou, L.; Zhang, Z. Vegetation changes of Lushan, China between 1959 and 2020 based on pollen data. Palynology 2025, 49, 2428378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, F.Z.; Zhang, Z.Q.; Chen, L.Q.; Wang, J.X.; Shen, Z.P. Spatial distribution characteristics of soil organic carbon in subtropical forests of mountain Lushan, China. Environ. Monit. Assess. 2018, 190, 545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qiu, L.B.; Xiao, T.Q.; Bai, T.J.; Mo, X.Y.; Huang, J.H.; Deng, W.P.; Liu, Y.Q. Seasonal dynamics and influencing factors of litterfall production and carbon input in typical forest community types in Lushan Mountain, China. Forests 2023, 14, 341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, D.; Zhang, W.; Liu, X.; Zhao, Y.; Sun, L.; Zhang, S.; Chen, Z. Intra-Annual Growth Dynamics and Environmental Response of Leaves, Shoots and Stems in Quercus serrata on Lushan Mountain, Subtropical China. Forests 2025, 16, 305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin-Benito, D.; Pederson, N. Convergence in drought stress, but a divergence of climatic drivers across a latitudinal gradient in a temperate broadleaf forest. J. Biogeogr. 2015, 42, 925–937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forrester, D.I.; Ammer, C.; Annighöfer, P.J.; Barbeito, I.; Bielak, K.; Bravo-Oviedo, A.; Coll, L.; del Río, M.; Drössler, L.; Heym, M.; et al. Effects of crown architecture and stand structure on light absorption in mixed and monospecific Fagus sylvatica and Pinus sylvestris forests along a productivity and climate gradient through Europe. J. Ecol. 2017, 106, 746–760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zou, G.; Liu, Y.; Kong, F.; Liao, L.; Deng, G.; Jiang, X.; Cai, J.; Liu, W. Depression of the soil arbuscular mycorrhizal fungal community by the canopy gaps in a Japanese cedar (Cryptomeria japonica) plantation on Lushan Mountain, subtropical China. PeerJ 2021, 9, e10905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rao, J.; Ouyang, X.; Pan, P.; Huang, C.; Li, J.; Ye, Q. Ecological Risk Assessment of Forest Landscapes in Lushan National Nature Reserve in Jiangxi Province, China. Forests 2024, 15, 484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.Z.; Wang, L. Scientific Survey and Study of Biodiversity on the Lushan Nature Reserve in Jiangxi Province; Science Press: Beijing, China, 2010; pp. 241–443. [Google Scholar]

- Lin, L.; Xu, X.; Cao, G.; Zhang, F.; Li, Y.; Huang, J. Self-stabilizing maintenance process in plant communities of alpine meadows under different grazing intensities. Grassl. Res. 2023, 2, 140–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Du, H.; Yang, Z.; Song, T.; Zeng, F.; Peng, W.; Huang, G. Topography and Soil Properties Determine Biomass and Productivity Indirectly via Community Structural and Species Diversity in Karst Forest, Southwest China. Sustainability 2022, 14, 7644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, G.; Li, J.-Q.; Zang, R.-G.; Ding, Y.; Ai, X.-R.; Yao, L. Variation in three community features across habitat types and scales within a 15-ha subtropical evergreen-deciduous broadleaved mixed forest dynamics plot in China. Ecol. Evol. 2018, 8, 11987–11998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tomaszewska, M.A.; Henebry, G.M. How much variation in land surface phenology can climate oscillation modes explain at the scale of mountain pastures in Kyrgyzstan? Int. J. Appl. Earth Obs. Geoinf. 2020, 87, 102053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Wang, X.; Zhang, C.; Li, J.; Jiang, H.; Sheng, L.; Li, Z. Stand Structure Management and Tree Diversity Conservation Based on Using Stand Factors: A Case Study in the Longwan National Nature Reserve. Forests 2023, 14, 750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Li, Y.; Bai, X.Y.; Sheng, L.X.; Zhang, H.L.; Chen, F.P.; Xiao, Y.J.; Liu, W.Z.; Zhai, Y.Q. Effects of gold and copper mining on the structure and diversity of the surrounding plant communities in Northeast Tiger and Leopard National Park. Front. Plant Sci. 2024, 15, 1419345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, W.D.; Zhao, J.J.; Zhang, B.J.; Deng, G.; Maimaiti, A.; Guo, Z.J. Patterns and drivers of tree species diversity in a coniferous forest of northwest China. Front. For. Glob. Change 2024, 7, 1333232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simonson, W.D.; Allen, H.D.; Coomes, D.A. Overstorey and topographic effects on understories: Evidence for linkage from cork oak (Quercus suber) forests in Southern Spain. For. Ecol. Manag. 2014, 328, 35–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abella, S.R.; Menard, K.S.; Schetter, T.A.; Hausman, C.E. Co-Variation among Vegetation Structural Layers in Forested Wetlands. Wetlands 2021, 41, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; Zhao, M.; Qi, L.; Zhao, C.; Zhang, W.; Zhang, Y.; Wen, W.; Yuan, J. Coupled Relationship between Soil Physicochemical Properties and Plant Diversity in the Process of Vegetation Restoration. Forests 2022, 13, 648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Decocq, G. Patterns of plant species and community diversity at different organization levels in a forested riparian landscape. J. Veg. Sci. 2002, 13, 91–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ming, A.G.; Yang, Y.J.; Liu, S.R.; Nong, Y.; Tao, Y.; Zeng, J.; An, N.; Niu, C.H.; Zhao, Z.; Jia, H.Y.; et al. A Decade of Close-to Nature Transformation Alters Species Composition and Increases Plant Community Diversity in Two Coniferous Plantations. Front. Plant Sci. 2020, 11, 1141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodrigues, A.C.; Villa, P.M.; Ferreira-Júnior, W.G.; Schaefer, C.E.R.G.; Neri, A.V. Effects of topographic variability and forest attributes on fine-scale soil fertility in late-secondary succession of Atlantic Forest. Ecol. Process. 2021, 10, 62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, J.; Zhang, H.; Qiao, Y.; Yuan, H.; Xu, W.; Xia, X. Effects of Microtopography on Neighborhood Diversity and Competition in Subtropical Forests. Plants 2025, 14, 870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, C.S.; Li, X.Y.; Chen, L.; Xie, G.D.; Liu, C.L.; Pei, S. Effects of Topographical and Edaphic Factors on Tree Community Structure and Diversity of Subtropical Mountain Forests in the Lower Lancang River Basin. Forests 2016, 7, 222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, H.; Wang, Q.R.; Fan, W.; Song, G.H. The Relationship between Secondary Forest and Environmental Factors in the Southern Taihang Mountains. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 16431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.X.; Guo, X.W.; Chen, L.X.; Kuzyakov, Y.; Wang, R.Z.; Zhang, H.Y.; Han, X.G.; Jiang, Y.; Sun, O.J. Global pattern of organic carbon pools in forest soils. Glob. Change Biol. 2024, 30, e17386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, F.; Wang, Z.H.; Hou, J.F.; Li, X.Q.; Wang, D.; Yang, W.Q. The changes in soil organic carbon stock and quality across a subalpine forest successional series. For. Ecosyst. 2024, 11, 100203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lippok, D.; Beck, S.G.; Renison, D.; Hensen, I.; Apaza, A.E.; Schleuning, M. Topography and edge effects are more important than elevation as drivers of vegetation patterns in a neotropical montane forest. J. Veg. Sci. 2014, 25, 724–733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, L.J.; Wang, Z.G.; Zhan, X.H.; Wu, W.Z.; Jiang, B.; Jiao, J.J.; Yuan, W.G.; Zhu, J.R.; Ding, Y.; Li, T.T.; et al. Assessment of Species Composition and Community Structure of the Suburban Forest in Hangzhou, Eastern China. Sustainability 2022, 14, 4304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fujimoto, Y.; Kaneko, T.; Sato, H.; Rakotomamonjy, A.H.; Razafiarison, Z.L.; Kitajima, K. Topographical gradient of the structure and diversity of a woody plant community in a seasonally dry tropical forest in northwestern Madagascar. Ecol. Res. 2024, 39, 705–716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chuyong, G.B.; Kenfack, D.; Harms, K.E.; Thomas, D.W.; Condit, R.; Comita, L.S. Habitat specificity and diversity of tree species in an African wet tropical forest. Plant Ecol. 2011, 212, 1363–1374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Luo, Y.; Song, X.; Jiang, D.; He, Q.; Bai, A.; Li, R.; Zhang, W. Effects of the Dominate Plant Families on Elevation Gradient Pattern of Community Structure in a Subtropical Forest. Forests 2023, 14, 1860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, P.C.; Wang, W.D.; Bai, Z.Q.; Guo, Z.J.; Ren, W.; Huang, J.H.; Xu, Y.; Yao, J.; Ding, Y.; Zang, R.G. Nutrient loads and ratios both explain the coexistence of dominant tree species in a boreal forest in Xinjiang, Northwest China. For. Ecol. Manag. 2021, 491, 119198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Yu, S.X.; Xie, Z.P.; Staehelin, C. Analysis of a negative plant-soil feedback in a subtropical monsoon forest. J. Ecol. 2012, 100, 1019–1028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, M.M.; Zhang, S.; Wang, G.C.; Xiao, L.J.; Gu, B.J.; Zheng, M.H.; Niu, S.L.; Yang, Y.H.; Luo, Y.Q.; Zhang, G.L.; et al. Increased plant productivity exacerbates subsoil carbon losses under warming via nitrogen mining. Nat. Geosci. 2025, 18, 510–517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variable | Minimum | Maximum | Mean Value | Standard Deviation | Coefficient of Variation(%) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tree layer | R | 5.00 | 37.00 | 21.32 | 5.13 | 24.06 |

| D | 0.74 | 0.96 | 0.91 | 0.04 | 4.50 | |

| H′ | 1.33 | 3.18 | 2.41 | 0.31 | 13.05 | |

| E | 0.57 | 0.89 | 0.79 | 0.06 | 7.75 | |

| SD | 10.00 | 216.00 | 79.88 | 31.91 | 39.95 | |

| H | 4.08 | 11.11 | 6.50 | 1.11 | 17.13 | |

| DBH | 4.14 | 17.82 | 9.32 | 2.07 | 22.20 | |

| Shrub layer | R | 1.00 | 19.00 | 9.85 | 2.93 | 29.73 |

| D | 0.49 | 0.93 | 0.81 | 0.08 | 10.04 | |

| H′ | 0.24 | 2.62 | 1.71 | 0.36 | 21.12 | |

| E | 0.42 | 0.96 | 0.76 | 0.10 | 13.00 | |

| SD | 1.00 | 281.00 | 96.51 | 57.61 | 59.69 | |

| H | 1.86 | 6.20 | 3.31 | 0.67 | 20.22 | |

| DBH | 1.63 | 6.18 | 3.10 | 0.66 | 21.45 | |

| Soil properties | pH | 3.58 | 5.34 | 4.10 | 0.23 | 5.50 |

| TC content (g/kg) | 22.51 | 80.80 | 47.24 | 9.92 | 20.99 | |

| TN content (g/kg) | 1.59 | 7.33 | 3.54 | 0.89 | 25.05 | |

| TP content (g/kg) | 0.11 | 1.13 | 0.38 | 0.13 | 34.50 | |

| TK content (g/kg) | 2.90 | 18.93 | 9.47 | 2.96 | 31.25 | |

| AN content (mg/kg) | 90.70 | 678.24 | 324.47 | 97.54 | 30.06 | |

| AP content (mg/kg) | 1.28 | 28.24 | 5.22 | 2.40 | 46.02 | |

| AK content (mg/kg) | 24.87 | 229.80 | 87.18 | 36.36 | 41.71 | |

| C:N | 10.04 | 19.60 | 13.66 | 1.63 | 11.90 | |

| C:P | 54.84 | 391.87 | 138.68 | 48.38 | 34.88 | |

| N:P | 4.03 | 27.64 | 10.28 | 3.64 | 35.46 | |

| BD (g/cm3) | 0.57 | 3.91 | 1.00 | 0.23 | 23.12 | |

| Topographic parameters | Elevation (m) | 945.03 | 1172.65 | 1062.55 | 54.38 | 5.12 |

| Slope (°) | 1.24 | 65.67 | 26.58 | 9.29 | 34.94 | |

| TRASP index | 0.01 | 1.00 | 0.83 | 0.20 | 24.56 | |

| Convexity | −35.87 | 63.53 | 0.15 | 7.11 | 4619.83 | |

| Index | Shrub Layer | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| R | D | H′ | E | SD | H | DBH | ||

| Tree layer | R | 0.312 *** | −0.044 ns | 0.142 *** | −0.154 *** | 0.228 *** | −0.102 * | −0.122 ** |

| D | 0.296 *** | 0.419 *** | 0.420 *** | 0.341 *** | −0.200 *** | 0.295 *** | 0.271 *** | |

| H′ | 0.348 *** | 0.199 *** | 0.329 *** | 0.122 ** | 0.025 ns | 0.121 ** | 0.092 * | |

| E | 0.193 *** | 0.307 *** | 0.318 *** | 0.323 *** | −0.202 *** | 0.243 *** | 0.229 *** | |

| SD | 0.088 * | −0.314 *** | −0.137 *** | −0.398 *** | 0.432 *** | −0.204 *** | −0.295 *** | |

| H | −0.279 *** | −0.161 *** | −0.254 *** | −0.082 * | 0.091 * | 0.097 * | 0.034 ns | |

| DBH | −0.323 *** | −0.163 *** | −0.276 *** | −0.034 ns | 0.055 ns | −0.072 ns | 0.051 ns | |

| Index | Elevation | Slope | Convexity | TRASP Index |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| pH | −0.203 *** | 0.073 ns | 0.010 ns | −0.103 * |

| BD | −0.023 ns | −0.020 ns | 0.103 * | −0.076 ns |

| TC | 0.123 ** | 0.039 ns | −0.054 ns | −0.071 ns |

| TN | −0.005 ns | 0.061 ns | −0.051 ns | −0.092 * |

| TP | −0.003 ns | <0.001 ns | −0.009 ns | 0.092 * |

| TK | −0.033 ns | 0.116 ** | 0.046 ns | 0.041 ns |

| AN | −0.068 ns | 0.055 ns | 0.040 ns | −0.140 *** |

| AP | −0.111 ** | 0.058 ns | 0.005 ns | −0.097 * |

| AK | −0.138 *** | 0.101 * | 0.009 ns | −0.022 ns |

| C:N | 0.200 *** | −0.079 * | −0.005 ns | 0.062 ns |

| C:P | 0.098 * | 0.045 ns | −0.019 ns | −0.146 *** |

| N:P | 0.033 ns | 0.071 ns | −0.016 ns | −0.170 *** |

| Environmental Factor | Tree Layer | Shrub Layer | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| F | p | F | p | |

| pH | 10 | 0.002 ** | 46.3 | 0.002 ** |

| BD | 0.7 | 0.474 | 0.4 | 0.646 |

| TC | 21.3 | 0.002 ** | 6.3 | 0.004 ** |

| TN | 2 | 0.102 | 29 | 0.002 ** |

| TP | 22 | 0.002 ** | 5.8 | 0.006 ** |

| TK | 0.5 | 0.61 | 5 | 0.014 * |

| AN | 6.6 | 0.004 ** | 2.1 | 0.128 |

| AP | 2.7 | 0.058 | 5.8 | 0.006 ** |

| AK | 0.2 | 0.894 | 7.9 | 0.008 ** |

| C:N | 45.6 | 0.002 ** | 258 | 0.002 ** |

| C:P | 1.7 | 0.166 | 1.6 | 0.188 |

| N:P | 1.4 | 0.206 | 1.2 | 0.272 |

| Elevation | 29.4 | 0.002 ** | 26.9 | 0.002 ** |

| Slope | 1.6 | 0.206 | 0.4 | 0.706 |

| Convexity | 1.1 | 0.318 | 1.6 | 0.172 |

| TRASP index | 3.3 | 0.062 | 2.7 | 0.078 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Xiang, Z.; Wang, J.; Xi, D.; Zhang, Z.; Tang, Z.; Hu, Y.; Zhang, J.; Zhou, S. Topographic and Edaphic Drivers of Community Structure and Species Diversity in a Subtropical Deciduous Broad-Leaved Forest in Eastern China. Forests 2025, 16, 1837. https://doi.org/10.3390/f16121837

Xiang Z, Wang J, Xi D, Zhang Z, Tang Z, Hu Y, Zhang J, Zhou S. Topographic and Edaphic Drivers of Community Structure and Species Diversity in a Subtropical Deciduous Broad-Leaved Forest in Eastern China. Forests. 2025; 16(12):1837. https://doi.org/10.3390/f16121837

Chicago/Turabian StyleXiang, Zeyu, Jingxuan Wang, Dan Xi, Zhaochen Zhang, Zhongbing Tang, Yunan Hu, Jiaxin Zhang, and Saixia Zhou. 2025. "Topographic and Edaphic Drivers of Community Structure and Species Diversity in a Subtropical Deciduous Broad-Leaved Forest in Eastern China" Forests 16, no. 12: 1837. https://doi.org/10.3390/f16121837

APA StyleXiang, Z., Wang, J., Xi, D., Zhang, Z., Tang, Z., Hu, Y., Zhang, J., & Zhou, S. (2025). Topographic and Edaphic Drivers of Community Structure and Species Diversity in a Subtropical Deciduous Broad-Leaved Forest in Eastern China. Forests, 16(12), 1837. https://doi.org/10.3390/f16121837