Assessment of the Crown Condition of Oak (Quercus) in Poland—Analysis of Defoliation Trends and Regeneration in the Years 2015–2024

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

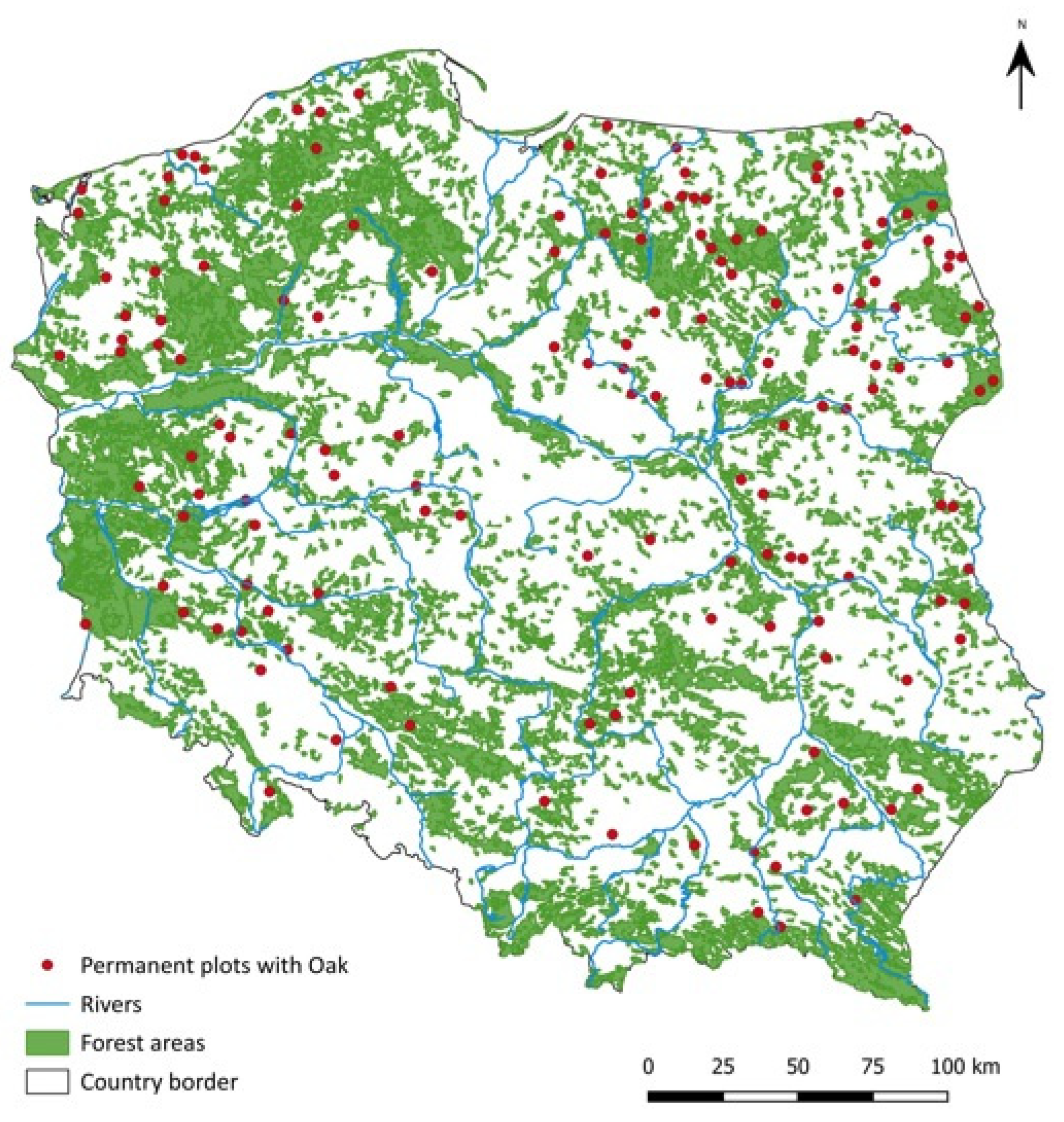

2.1. Field Observations

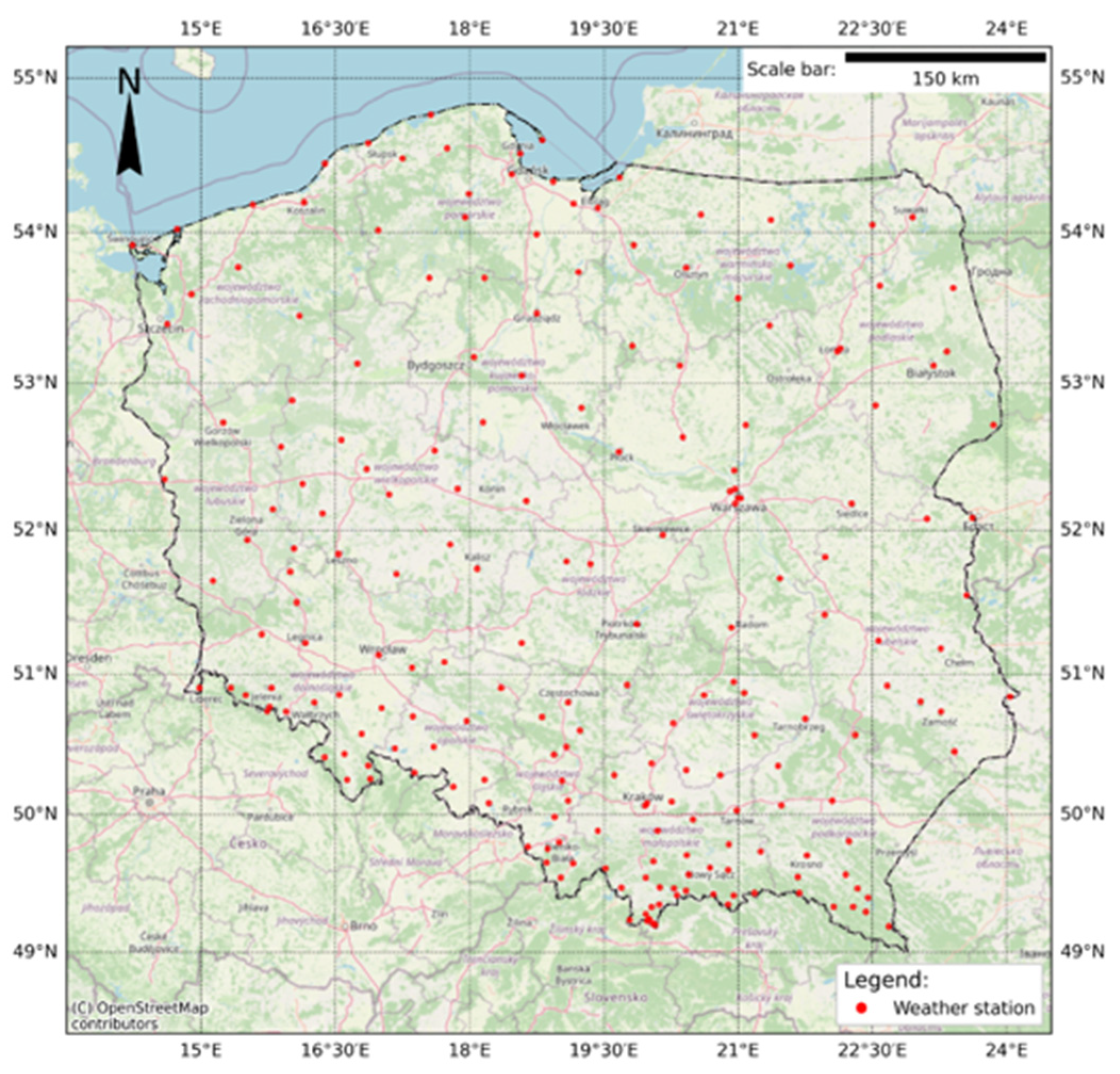

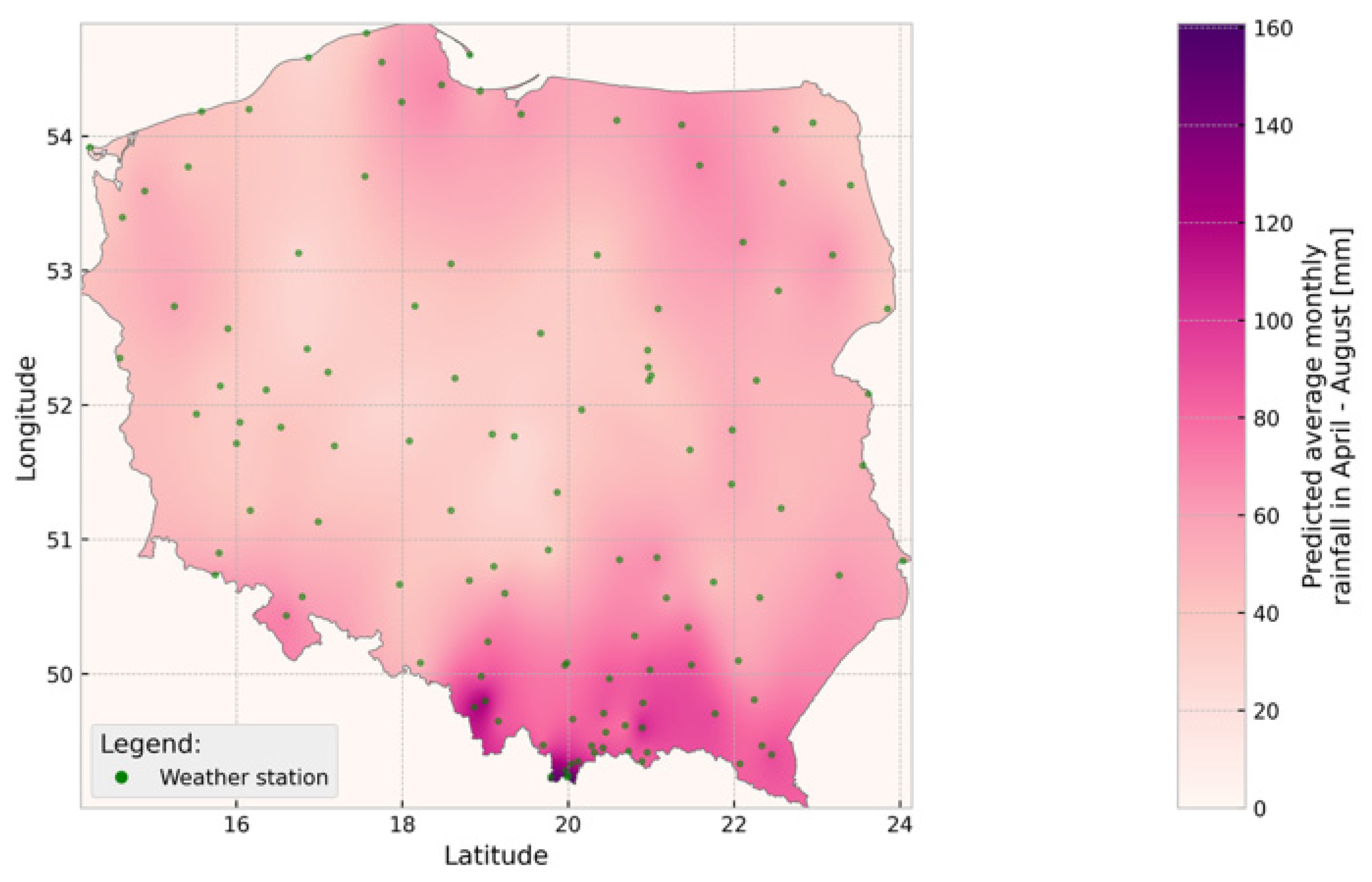

2.2. Climatic Analyses

2.3. The Statistical Analysis

- yt—mean defoliation in year t,

- α—intercept term,

- β1, β2—slope coefficients before and after the breakpoint,

- τ—breakpoint,

- (x)+ = max (x, 0),

- εt—random error term.

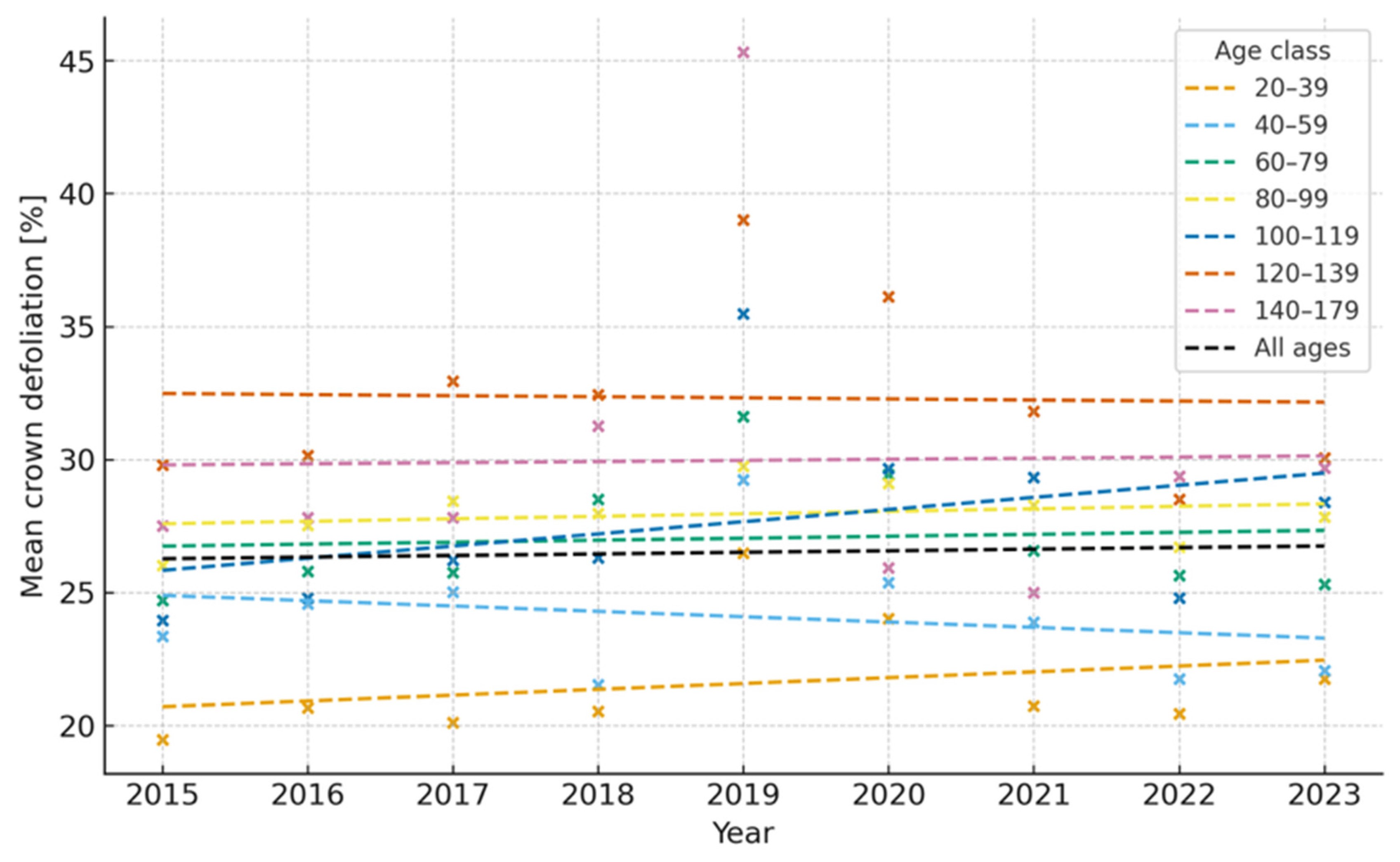

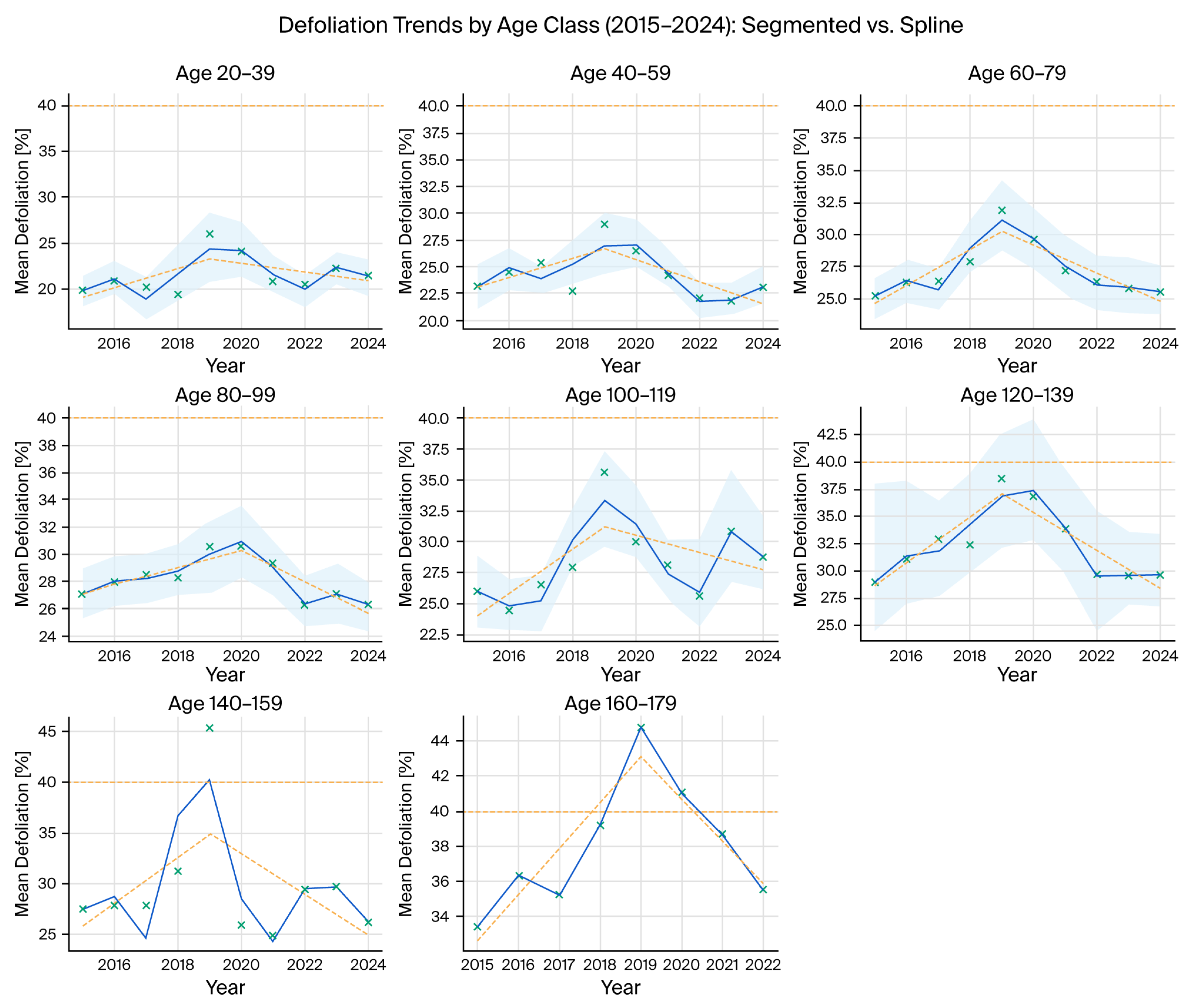

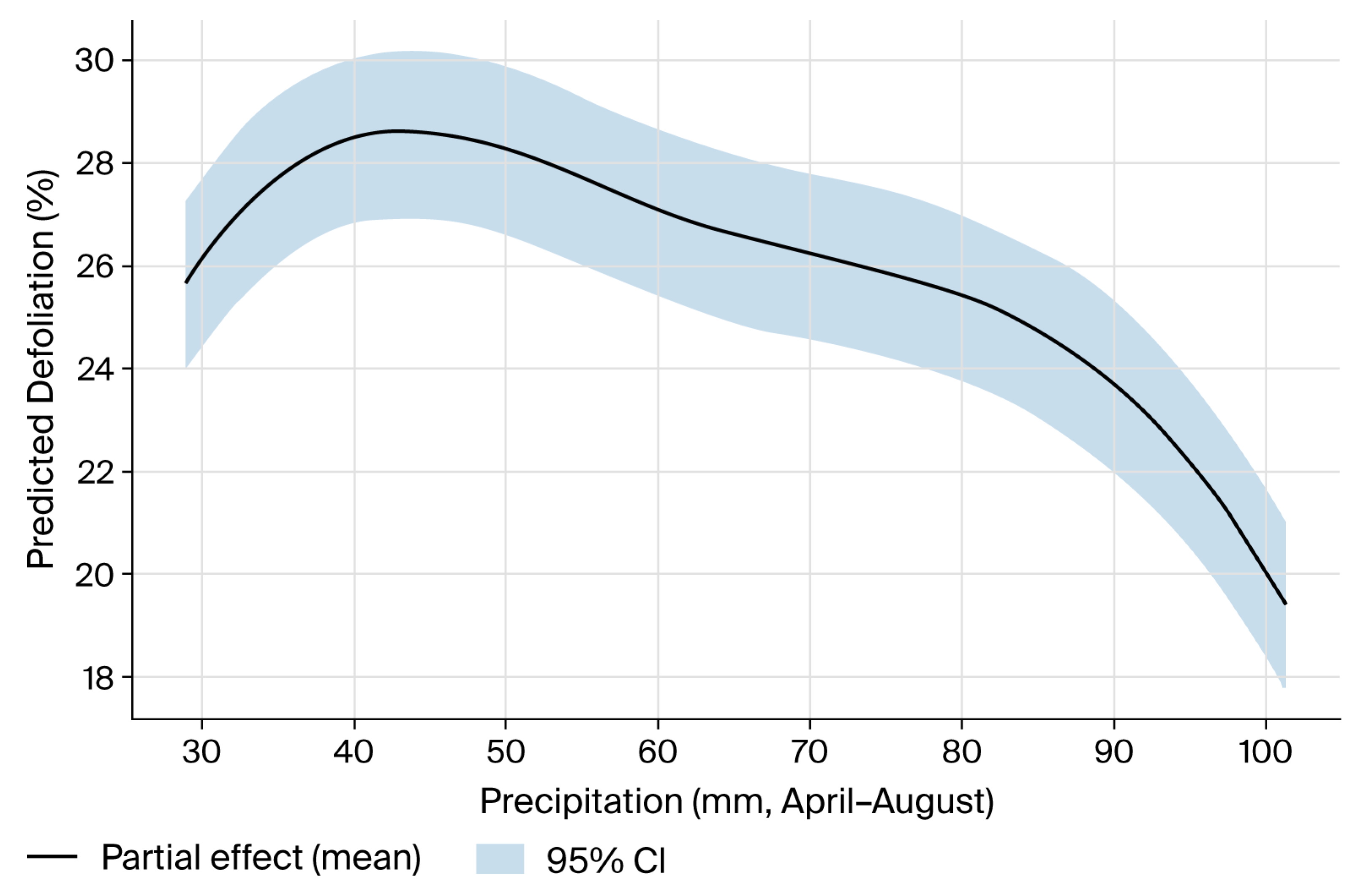

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

- (1)

- older oak stands require prioritised monitoring due to their reduced hydraulic safety margins and slower post-drought recovery;

- (2)

- maintaining adequate soil nutrient availability, particularly phosphorus, can enhance resilience under drought;

- (3)

- integrating defoliation monitoring with climatic indicators can support early warning systems for forest health.

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- McDowell, N.G.; Allen, C.D.; Anderson-Teixeira, K.; Aukema, B.H.; Bond-Lamberty, B.; Chini, L.; Clark, J.S.; Dietze, M.; Grossiord, C.; Hanbury-Brown, A.; et al. Pervasive shifts in forest dynamics in a changing world. Science 2020, 368, eaaz9463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Council of the European Communities. Council Directive 92/43/EEC of 21 May 1992 on the Conservation of Natural Habitats and of Wild Fauna and Flora. Off. J. Eur. Communities 1992, L 206, 7–50. [Google Scholar]

- Cook, B.I.; Mankin, J.S.; Marvel, K.; Williams, A.P.; Smerdon, J.E.; Anchukaitis, K.J. Twenty-First Century Drought Projections in the CMIP6 Forcing Scenarios. Earth’s Future 2020, 8, e2019EF001461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seidl, R.; Thom, D.; Kautz, M.; Martin-Benito, D.; Peltoniemi, M.; Vacchiano, G.; Wild, J.; Ascoli, D.; Petr, M.; Honkaniemi, J.; et al. Forest disturbances under climate change. Nat. Clim. Change 2017, 7, 395–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hlásny, T.; Seidl, R.; Barka, I.; Dobor, L.; Merganičová, K.; Kulla, L.; Trombik, J.; Štěpánek, P.; Bartoš, M.; Turčáni, M. Climate change increases the drought risk in Central European forests: What are the options for adaptation? For. Ecol. Manag. 2021, 494, 118990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dyderski, M.K.; Paź-Dyderska, S.; Jagodziński, A.M.; Puchałka, R. Shifts in native tree species distributions in Europe under climate change. J. Environ. Manag. 2025, 373, 123504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Przybylski, P.; Związek, T.; Kowalczyk, J.; Słowiński, M. Research perspectives on historical legacy of the Scots pine (Pinus sylvestris L.): Genes as the silent actor in the transformation of the Central European forests in the last 200 years. Elem. Sci. Anthr. 2025, 13, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krawczyk, W.; Wężyk, P. Using Satellite Imagery and Aerial Orthophotos for the Multi-Decade Monitoring of Subalpine Norway Spruce Stands Changes in Gorce National Park, Poland. Remote Sens. 2023, 15, 951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niemczyk, M.; Thomas, B.R.; Jastrzębowski, S. Strategies for difficult times: Physiological and morphological responses to drought stress in seedlings of Central European tree species. Trees 2023, 37, 1657–1669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arend, M.; Kuster, T.; Günthardt-Goerg, M.S.; Dobbertin, M. Provenance-specific growth responses to drought in Quercus robur and Q. petraea. For. Ecol. Manag. 2011, 261, 1221–1232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmied, G.; Hilmers, T.; Mellert, K.-H.; Uhl, E.; Buness, V.; Ambs, D.; Steckel, M.; Biber, P.; Šeho, M.; Hoffmann, Y.-D.; et al. Nutrient regime modulates drought response patterns of three temperate tree species. Sci. Total Environ. 2023, 868, 161601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Somorowska, U. Amplified signals of soil moisture and evaporative stresses across Poland in the twenty-first century. Sci. Total Environ. 2022, 812, 151465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gehring, C.A.; Swaty, R.L.; Deckert, R.J. Mycorrhizas, drought, and host-plant mortality. In Mycorrhizal Mediation of Soil; Johnson, N.C., Gehring, C., Jansa, J., Eds.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2017; pp. 279–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grossiord, C.; Buckley, T.N.; Cernusak, L.A.; Novick, K.A.; Poulter, B.; Siegwolf, R.T.W.; Sperry, J.S.; McDowell, N.G. Plant responses to rising vapor pressure deficit. New Phytol. 2020, 226, 1550–1566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nicolescu, V.-N.; Vor, T.; Brus, R.; Đodan, M.; Perić, S.; Podrázský, V.; Andrašev, S.; Tsavkov, E.; Ayan, S.; Yücedağ, C.; et al. Management of sessile oak (Quercus petraea (Matt.) Liebl.), a major forest species in Europe. J. For. Res. 2025, 36, 78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Przybylski, P.; Mohytych, V.; Rutkowski, P.; Tereba, A.; Tyburski, Ł.; Fyalkowska, K. Relationships between some biodiversity indicators and crown damage of Pinus sylvestris L. in natural old-growth pine forests. Sustainability 2021, 13, 1239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eickenscheidt, N.; Augustin, N.H.; Wellbrock, N. Spatio-temporal modelling of forest monitoring data: Modelling German tree defoliation data collected between 1989 and 2015 for trend estimation and survey grid examination using GAMMs. iForest 2019, 12, 338–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hartmann, H.; Adams, H.D.; Anderegg, W.R.L.; Jansen, S.; Zeppel, M.J.B. Research frontiers in drought-induced tree mortality: Crossing scales and disciplines. New Phytol. 2015, 205, 965–969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bugała, W. (Ed.) Dęby: Quercus robur L.; Quercus petraea (Matt.) Liebl.; Nasze Drzewa Leśne; Bogucki Wydawnictwo Naukowe: Poznań, Poland, 2006; Volume 11, pp. 1–972. [Google Scholar]

- Schwärzel, K.; Seidling, W.; Hansen, K.; Strich, S.; Lorenz, M. Part I: Objectives, strategy and implementation of ICP Forests. Version 2022-2. In Manual on Methods and Criteria for Harmonized Sampling, Assessment, Monitoring and Analysis of the Effects of Air Pollution on Forests; UNECE ICP Forests Programme Coordinating Centre, Ed.; Thünen Institute of Forest Ecosystems: Eberswalde, Germany, 2022; 12p + Annexes; Available online: http://www.icp-forests.net/page/icp-forests-manual (accessed on 2 October 2025).

- Chief Inspectorate of Environmental Protection (GIOŚ). Reports on the Health Condition of Forests in Poland. Available online: https://monlas.gios.gov.pl/wyniki/raporty-o-stanie-zdrowotnym-lasow (accessed on 29 October 2025).

- Institute of Meteorology and Water Management (IMGW-PIB). Public Data Portal. Available online: https://danepubliczne.imgw.pl/en (accessed on 29 October 2025).

- McKinney, W. Data structures for statistical computing in Python. In Proceedings of the 9th Python in Science Conference (SciPy 2010), Austin, TX, USA, 28 June–3 July 2010; pp. 51–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harris, C.R.; Millman, K.J.; van der Walt, S.J.; Gommers, R.; Virtanen, P.; Cournapeau, D.; Wieser, E.; Taylor, J.; Berg, S.; Smith, N.J.; et al. Array programming with NumPy. Nature 2020, 585, 357–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jordahl, K.; Van den Bossche, J.; Fleischmann, M.; Wasserman, J.; McBride, J.; Gerard, J.; Tratner, J.; Perry, M.; Badaracco, A.; Farmer, C.; et al. Geopandas/Geopandas: v0.8.1. Zenodo. 2020. Available online: https://zenodo.org/records/3946761 (accessed on 15 July 2020).

- Murphy, B.; Yurchak, R.; Müller, S.; Ziebarth, M.; Basak, S.; Peveler, M.; van Lombeek, K.; Chang, W.; Matchette-Downes, H.; Mejía Raigosa, D.; et al. GeoStat-Framework/PyKrige: v1.7.2. Zenodo. 2024. Available online: https://zenodo.org/records/17372225 (accessed on 15 July 2025).

- Gillies, S. Rasterio: Geospatial Raster I/O for Python Programmers. Available online: https://github.com/mapbox/rasterio (accessed on 10 July 2025).

- Hunter, J.D. Matplotlib: A 2D graphics environment. Comput. Sci. Eng. 2007, 9, 90–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sen, P.K. Estimates of the regression coefficient based on Kendall’s tau. J. Am. Stat. Assoc. 1968, 63, 1379–1389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seabold, S.; Perktold, J. Statsmodels: Econometric and statistical modeling with Python. In Proceedings of the 9th Python in Science Conference (SciPy 2010), Austin, TX, USA, 28 June–3 July 2010; pp. 92–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pedregosa, F.; Varoquaux, G.; Gramfort, A.; Michel, V.; Thirion, B.; Grisel, O.; Blondel, M.; Prettenhofer, P.; Weiss, R.; Dubourg, V.; et al. Scikit-learn: Machine learning in Python. J. Mach. Learn. Res. 2011, 12, 2825–2830. [Google Scholar]

- Buras, A.; Rammig, A.; Zang, C.S. Quantifying impacts of the 2018 drought on European ecosystems in comparison to 2003. Biogeosciences 2020, 17, 3725–3740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Macháčová, M.; Nakládal, O.; Samek, M.; Baťa, D.; Zumr, V.; Pešková, V. Oak Decline Caused by Biotic and Abiotic Factors in Central Europe: A Case Study from the Czech Republic. Forests 2022, 13, 1223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beloiu, M.; Stahlmann, R.; Beierkuhnlein, C. Drought impacts in forest canopy and deciduous tree saplings in Central European forests. For. Ecol. Manag. 2022, 509, 120075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mölder, A.; Sennhenn-Reulen, H.; Fischer, C.; Rumpf, H.; Schönfelder, E.; Stockmann, J.; Nagel, R.-V. Success factors for high-quality oak forest (Quercus robur, Q. petraea) regeneration. For. Ecosyst. 2019, 6, 49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brunner, I.; Herzog, C.; Dawes, M.A.; Arend, M.; Sperisen, C. How tree roots respond to drought. Front. Plant Sci. 2015, 6, 547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gessler, A.; Bottero, A.; Marshall, J.; Arend, M. The way back: Recovery of trees from drought and its implication for acclimation. New Phytol. 2020, 228, 1704–1709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aitken, S.N.; Bemmels, J.B. Time to get moving: Assisted gene flow of forest trees. Evol. Appl. 2016, 9, 271–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choat, B.; Jansen, S.; Brodribb, T. Global convergence in the vulnerability of forests to drought. Nature 2012, 491, 752–755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hartmann, H.; Moura, C.F.; Anderegg, W.R.L.; Ruehr, N.K.; Salmon, Y.; Allen, C.D.; Arndt, S.K.; Breshears, D.D.; Davi, H.; Galbraith, D.; et al. Research frontiers for improving our understanding of drought-induced tree and forest mortality. New Phytol. 2018, 218, 15–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mucha, J.; Zadworny, M.; Bułaj, B. Root anatomical adaptations of contrasting ectomycorrhizal exploration types in Pinus sylvestris and Quercus petraea across soil horizons. Plant Soil 2025, 511, 119–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sukovata, L.; Jakoniuk, H.; Jaworski, T. A novel method for assessing the threat to oak stands from geometrid defoliators. For. Ecol. Manag. 2022, 520, 120380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Year | Mean Defoliation (%) | Change vs. Previous Year (pp) | Statistical Significance |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2015 | 25.1 | – | – |

| 2016 | 26.0 | +0.84 | n.s. |

| 2017 | 26.6 | +0.65 | n.s. |

| 2018 | 26.5 | −0.05 | n.s. |

| 2019 | 31.6 | +5.10 | *** |

| 2020 | 29.5 | −2.1 | n.s. |

| 2021 | 27.3 | −2.2 | ** |

| 2022 | 25.0 | −2.3 | ** |

| 2023 | 25.2 | +0.2 | n.s. |

| 2024 | 25.0 | −0.2 | n.s. |

| Year | Number of Plots (N) | Mean Defoliation (%) | Mean Precipitation (mm) | Pearson Correlation (r, Defoliation–Precipitation) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2017 | 102 | 28.5 | 78.9 | −0.10 |

| 2018 | 101 | 29.0 | 67.3 | −0.25 |

| 2019 | 100 | 33.5 | 47.0 | −0.45 |

| 2020 | 99 | 27.0 | 80.5 | −0.15 |

| 2021 | 101 | 25.0 | 74.8 | −0.08 |

| 2022 | 100 | 24.0 | 70.1 | −0.05 |

| 2023 | 101 | 26.0 | 72.4 | −0.12 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Zajączkowski, G.; Budniak, P.; Mroczek, P.; Gil, W.; Przybylski, P. Assessment of the Crown Condition of Oak (Quercus) in Poland—Analysis of Defoliation Trends and Regeneration in the Years 2015–2024. Forests 2025, 16, 1807. https://doi.org/10.3390/f16121807

Zajączkowski G, Budniak P, Mroczek P, Gil W, Przybylski P. Assessment of the Crown Condition of Oak (Quercus) in Poland—Analysis of Defoliation Trends and Regeneration in the Years 2015–2024. Forests. 2025; 16(12):1807. https://doi.org/10.3390/f16121807

Chicago/Turabian StyleZajączkowski, Grzegorz, Piotr Budniak, Piotr Mroczek, Wojciech Gil, and Pawel Przybylski. 2025. "Assessment of the Crown Condition of Oak (Quercus) in Poland—Analysis of Defoliation Trends and Regeneration in the Years 2015–2024" Forests 16, no. 12: 1807. https://doi.org/10.3390/f16121807

APA StyleZajączkowski, G., Budniak, P., Mroczek, P., Gil, W., & Przybylski, P. (2025). Assessment of the Crown Condition of Oak (Quercus) in Poland—Analysis of Defoliation Trends and Regeneration in the Years 2015–2024. Forests, 16(12), 1807. https://doi.org/10.3390/f16121807