1. Introduction

Climate change combined with legacy forest management practices (e.g., fire exclusion and densification of forests) is resulting in a more frequent occurrence of conditions favoring large wildfires that burn at greater severity and expanse than previously recorded [

1]. While fire is a natural disturbance process and necessary for many forest dynamics, unprecedented wildfire events have been altering entire fire regimes, disrupting conifer seed dispersal and seedling survival, and hampering forest recovery [

2]. As intensifying drought conditions increase rates of tree mortality, the need to prioritize successful regeneration and efficient postfire monitoring becomes more urgent for both ecological recovery and long-term forest management.

Increasing ambient temperatures and drought conditions could challenge seedbank and seedling resilience [

3]. The focus of this research is to identify an “optimal range”—defined as a span of measured microclimate variables associated with high seedling abundance. Understanding what optimal postfire environmental conditions are associated with seedling success can allow decision makers to more easily prioritize regeneration in areas with a higher likelihood of establishment and success by taking advantage of when these conditions arise postfire.

Tree seedlings and understory vegetation establishment depends strongly on environmental context quantified by biophysical site factors and microclimate conditions [

4]. Understanding how microclimates within the understory influence vegetative responses to landscape disturbances is still limited but important to implementing microclimate modeling that informs forest management and decision making [

5]. Roadblocks to microclimate modeling include gaps in understanding the ecological relationship of seedlings to a postfire environment.

Decades of fire suppression and exclusion have led to increased fuel loads, amplifying fire’s rate of spread, intensity, severity, and overall size [

1]. A total of 70,170 hectares burned in the 2020 Holiday Farm fire in the McKenzie River watershed in western Oregon, USA, the study site for this analysis (approximate center: 44.154075, −122.34265) (

Figure 1).

Unprecedented fire weather, resulting behavior, and high severity make the Holiday Farm fire a unique opportunity to monitor postfire natural regeneration. The large footprint and high severity were a result of unpredictable fire behavior caused by extreme weather in the form of an east wind event, a regional Foehn wind, synonymous with extreme fire behavior in the Pacific Northwest [

7]. The fire caused an estimated USD 4.8 billion in economic losses, including timber, land value, reconstruction, and reforestation, partially offset by USD 744 million in salvage harvest revenue [

8].

This mixed-conifer ecosystem supports culturally and economically important species, including Douglas fir (

Pseudotsuga menziesii), western hemlock (

Tsuga heterophylla), incense-cedar (

Calocedrus decurrens), and western redcedar (

Thuja plicata). The McKenzie River watershed lies within the Willamette National Forest, spanning elevations from 200 to 1200 m in a landscape of valleys, streams, and lakes [

9]. Wildland fire historically regulated vegetation under a Mediterranean climate with hot, dry summers and cool, wet winters [

10], with a mean fire interval (MFRI) of 49 years driven by Indigenous stewardship and natural ignitions; however, this has recently since shifted due to anthropogenic and climate factors [

11]. Other research has described postfire understory microclimate dynamics in dry mixed conifer forests, finding strong evidence of drought as a role player in stunted regeneration [

1,

5]. The western Oregon Cascade Mountains present a unique opportunity for this kind of microclimate research since it was conducted in a cool-wet forest type recently disturbed by high-severity stand-replacing fire exacerbated by drought conditions.

Successful seedling establishment underpins long-term forest recovery and the associated production of timber and other ecosystem services. Conifer seedlings grow very slowly at the beginning of their life cycle and are known to be well adapted to drought and fire. Douglas fir is relatively shade-intolerant but may require some cover (e.g., from residual overstory trees or shrubs) for protection from herbivores and to shield their microclimate [

6]. As saplings grow above competing vegetation and near stem exclusion, stand dynamics begin to shift and the young trees grow very quickly, increasing biomass and shading the understory below. These dynamic changes take place over decades and are indicative of millions of years of evolution, commensalism, and mutualistic relationships coevolving with fire regimes and thousands of years of human forest management via cultural burning. Increasing fire intervals via suppression and resultant fire exclusion can disrupt this dynamic and impact future generations of trees when fire return intensity/frequency accelerates beyond the capacity of conifers to reestablish [

12].

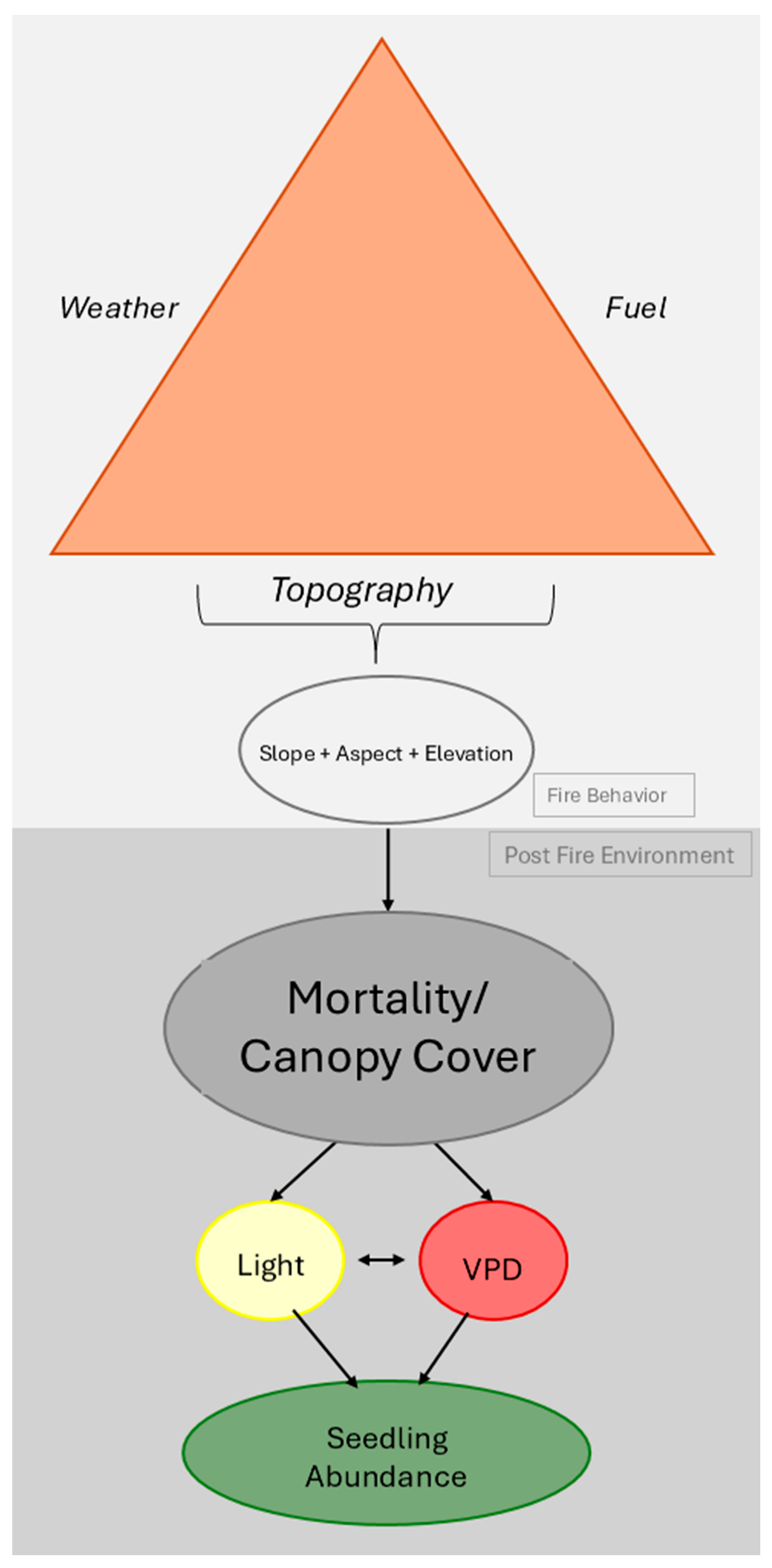

In the absence of adequate canopy cover, postfire seedlings are more exposed to and more susceptible to microclimatic extremes [

4]. Important measurable microclimate factors include vapor pressure deficit (VPD) and available sunlight. Drought intensity can be measured through VPD combining relative humidity and temperature, with recent studies highlighting increasing VPD across western North America as a significant threat to vegetation and ecosystems [

13]. Holding fuels and weather constant (in the absence of prefire and incident data that would show variability), topography is isolated as a predictor for overstory vegetation mortality after fire and residual canopy cover. Canopy cover can be indicative of a seed source, creating another indirect connection to seedling abundance. Canopy cover influences light levels and VPD directly, and these factors influence each other. These concepts emphasize that microclimate helps regulate the dynamics between postfire mortality, seed sources, and seedling abundance. High-severity fire with total canopy loss would be hypothesized to be the least conducive to seedling abundance, consistent with work in the area emphasizing moderate fire severity as most beneficial to natural regeneration [

14].

This study had two objectives: (1) identify optimal ranges of VPD and sun for seedling abundance in postfire environments of the McKenzie River watershed; and (2) evaluate how fire severity alters these optimal conditions, informing concepts of conifer regeneration under shifting fire regimes using nonparametric analyses including Kruskal–Wallis tests. A combination of ground measurements and nonparametric hypothesis tests begin to quantify the ecological relationship between microclimate and seedling abundance.

2. Materials and Methods

Increases in VPD have been strongly associated with changing wildfire patterns and conditions conducive to fire spread as drought conditions preheat and dry out fuels more rapidly [

15]. VPD is a useful indicator of tree stress, as higher VPD reflects drier air conditions that accelerate plant moisture loss through transpiration [

3]. Risks of high VPD include reduced photosynthesis and therefore growth, along with carbon starvation, and hydraulic failure [

16]. Light availability is a key microclimate factor influencing tree seedling success. Photosynthetic active radiation (PAR) wavelengths range from 400 to 700 nm, encompassing most of the visible spectrum [

17]. These wavelengths are related to photosynthesis and biomass accumulation in plants. Both insufficient and excessive light can limit growth; too little restricts photosynthesis, while too much can increase metabolic demand and desiccate seedlings when water is limited [

18].

Enhancing our conceptual understanding of how organisms interact with abiotic forest factors is essential for creating effective tools and strategies to guide management and decision making in a postfire environment, when regeneration is critical. This research considers the resulting environment that favors regeneration, taking a top–down approach. Topography is prioritized as a strong indicator of fire severity based on the fire triangle (

Figure 2).

Using the Holiday Farm fire footprint in western Oregon, USA (

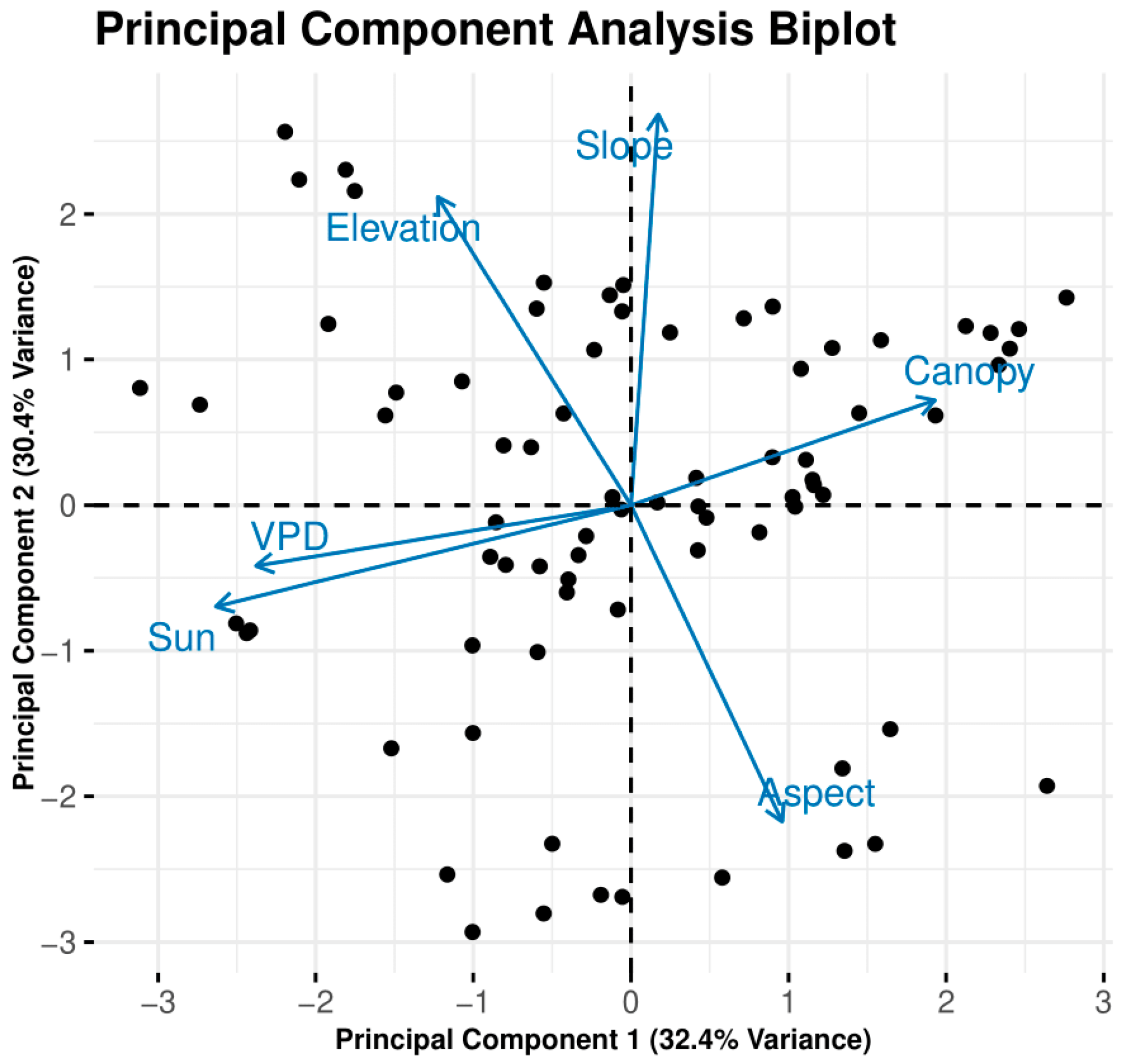

Figure 1), covariate space coverage sampling was used to select study sites based on elevation, aspect, slope, soil water storage, and composite burn index (CBI) using ESRI ArcGIS Pro v.3.4.3 [

19,

20,

21,

22,

23]. Covariate space coverage sampling is best used on small sample sizes and when measuring factors that may have many covariates influencing their behavior [

24]. All eligible sites were within 50–500 m from roads and more than 500 m from each other. Covariate space coverage sampling uses reiterations of k-means clusters to select sites across a variance to reduce the likelihood of selecting a local minimum; points are clustered together based on similarity, then one point is selected from that group. Successful microclimate ground assessment was completed for 20 plots.

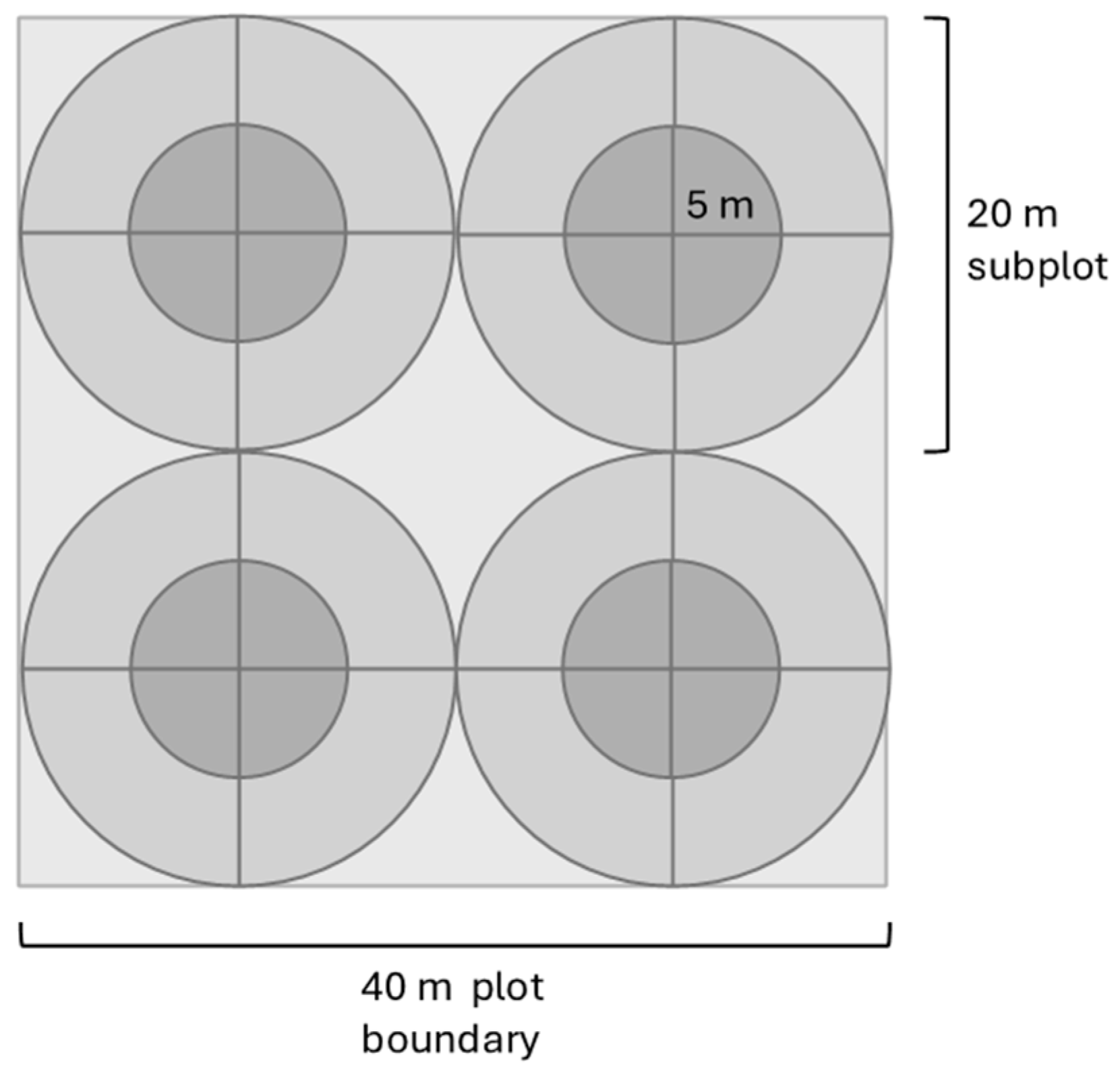

Data collection commenced on 17 June and ended on 1 August 2024. Using the Avenza Maps v.5.4.1 mobile application coordinates for each site and georeferenced. From that location, 4 subplots were established. To establish a subplot, the first coordinate location was recorded, and a 5 and 10 m radius were measured around it (

Figure 3).

We integrated data from a Kestrel handheld weather device (Nielsen-Kellerman Co., Boothwyn PA, USA), PAR sensor (LI-COR, Lincoln, NE, USA), and sunfleck ceptometer (Decagon, LP-80 Ceptometer, 1994, Pullman, WA, USA). The sunfleck ceptometer measures available light using 80 PAR sensors along a 1 m wand. Within the 5 m radius, GPS location, slope, elevation, photosynthetic active radiation (PAR), temperature, and relative humidity were recorded. Special considerations when measuring PAR were taken to aid consistency and standardization of data. A PAR sensor was left in a full sun area near the plot to record calibration measurements every ten seconds. In total, 20 measurements were taken with the ceptometer covering the 5 m radius to give a single average value per subplot and 4 values per plot. The time of these measurements was also recorded. Using time, ceptometer values, and full sun values, percent sun was calculated while accounting for diurnal changes. In addition, all seedling heights and diameters were measured, and tree species were delineated across all 20 plots (

Table 1).

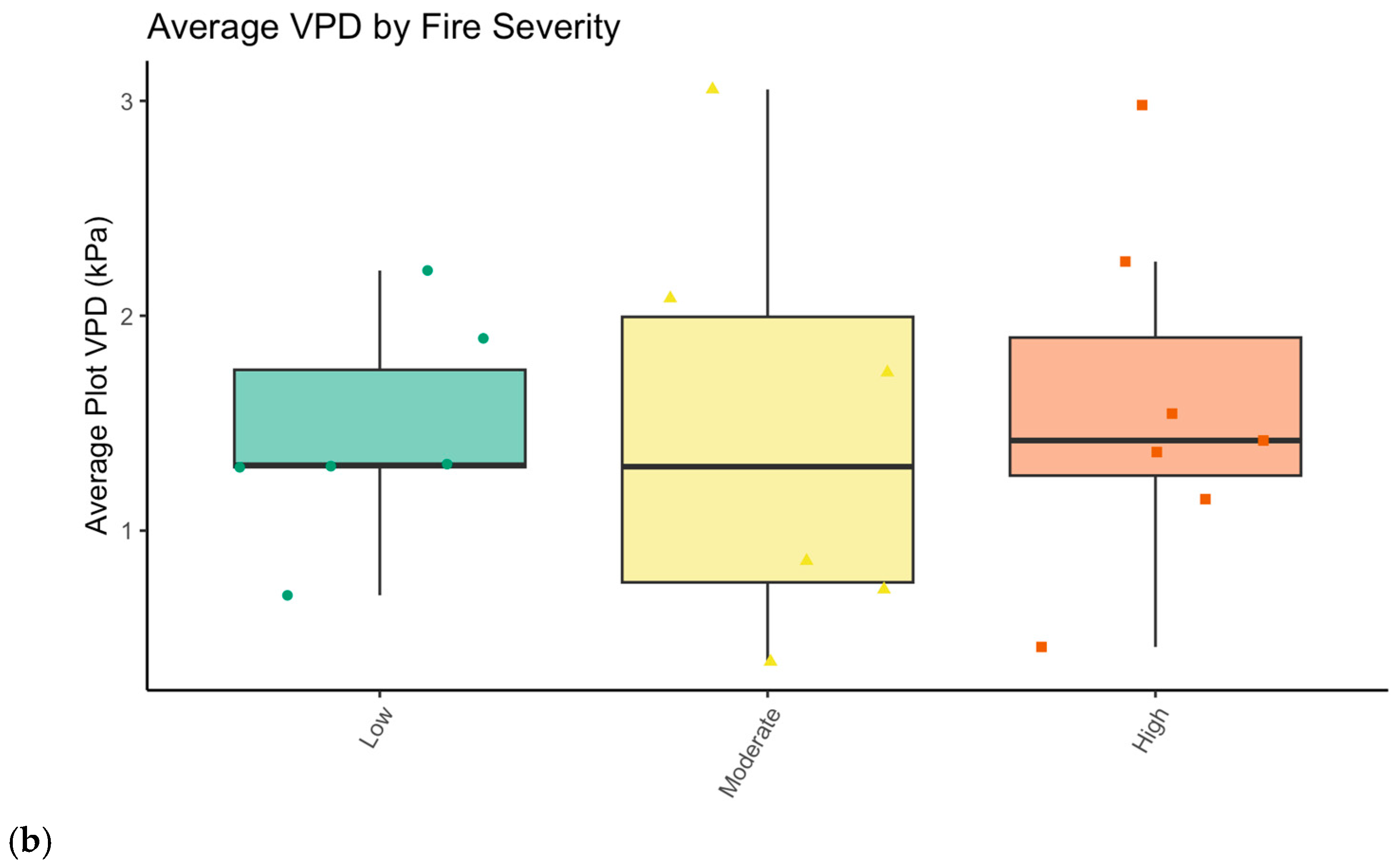

Seedling abundance (total count per plot), average atmospheric vapor pressure deficit (kPa), and average percent sun were calculated for each plot. Data were grouped by plot and fire severity class based on CBI values categorizing sites as low, moderate, or high severity.

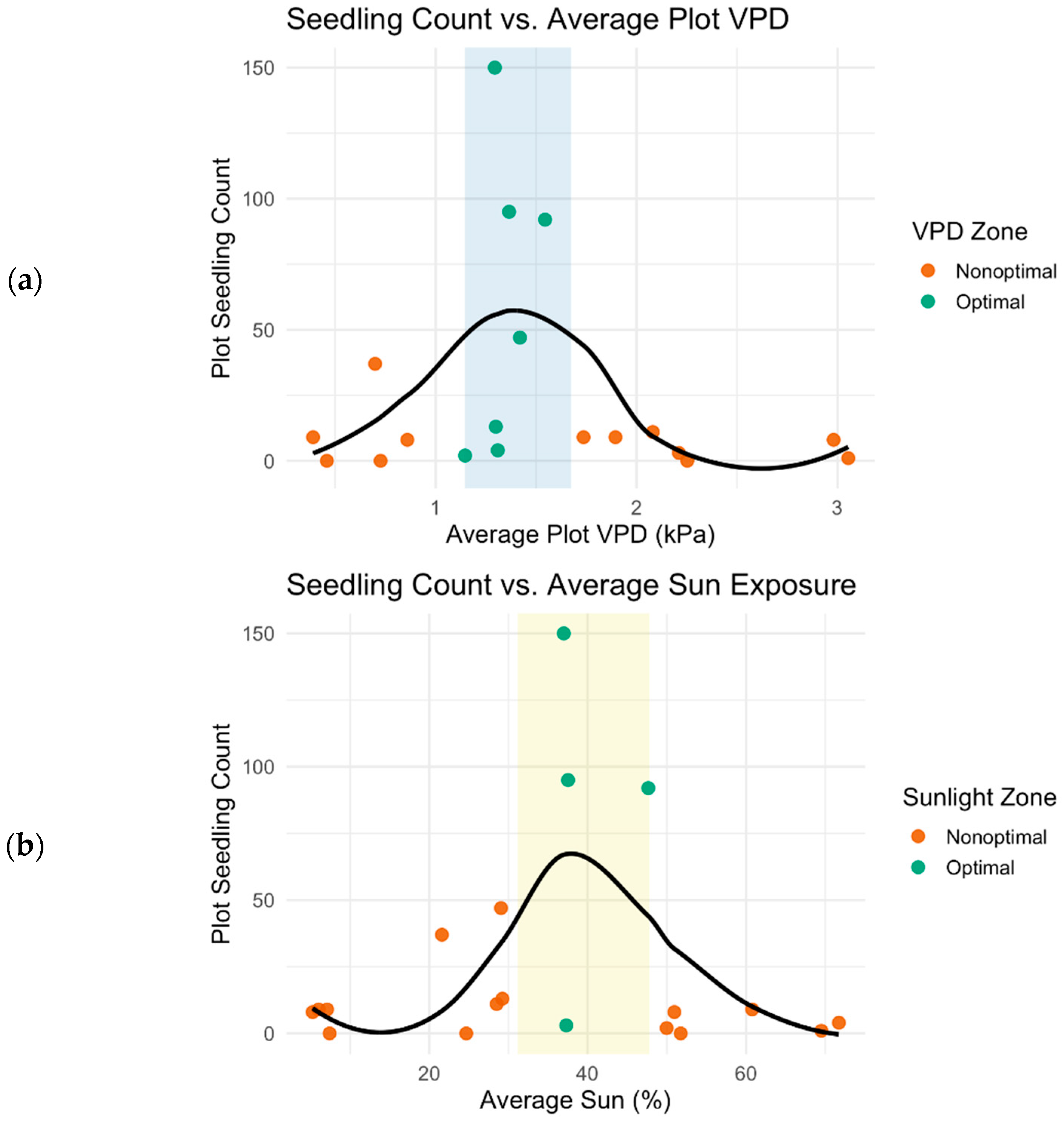

Exploratory data visualization and summary statistics identified optimal VPD and percent sun ranges for seedling abundance. To visualize potential nonlinear relationships between microclimate variables and seedling abundance, locally weighted least squares regression (LOESS) curves were fit between average VPD and seedling count, and between average percent sun and seedling count using a span of 0.75 for sun and 0.8 for VPD to avoid overfitting where there was more variance. LOESS curves are a form of regression used to smooth scatter plots based on a moving average across data [

25]. Predictive LOESS models were used to identify optimal ranges of VPD and percent sun.

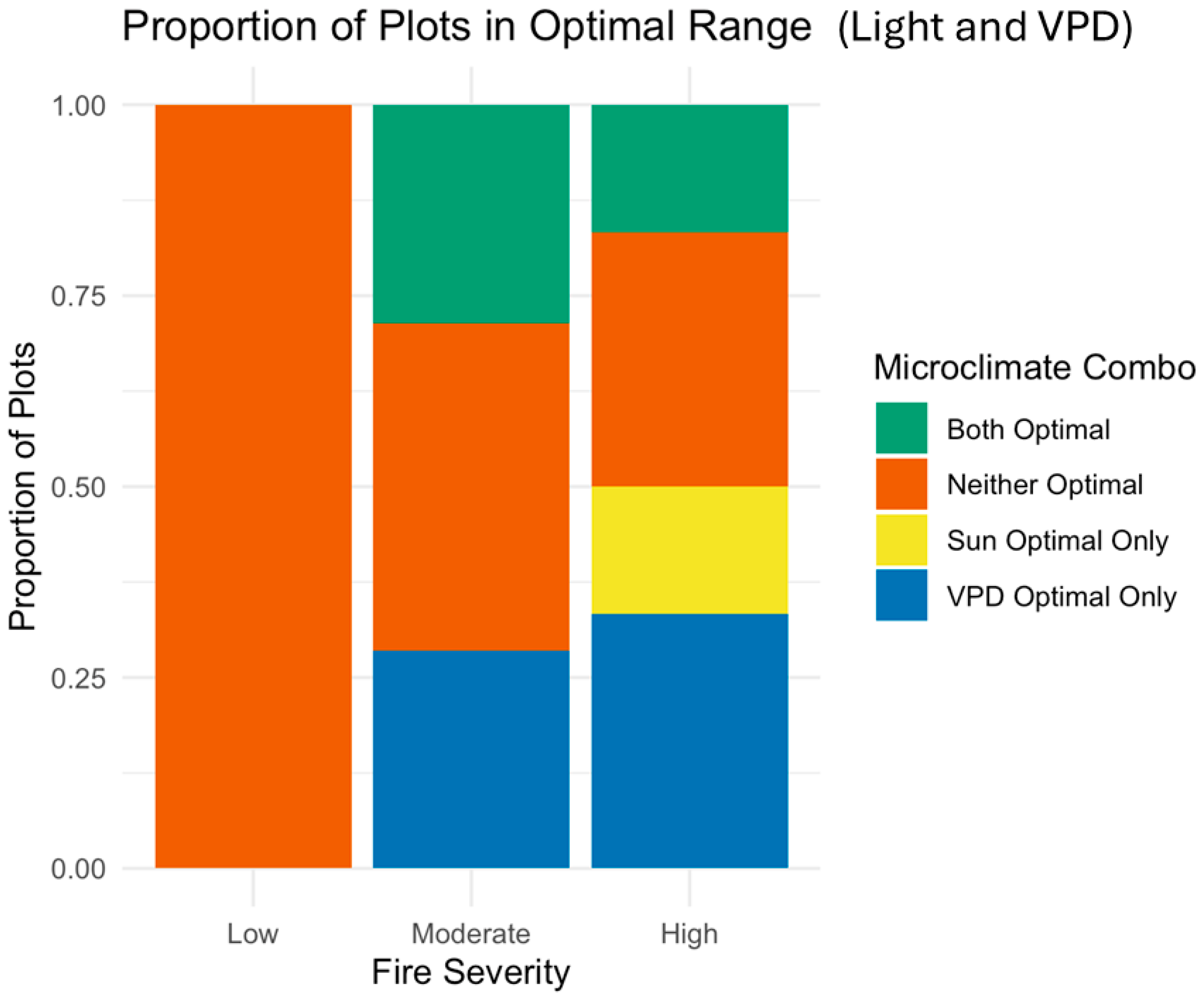

Nonparametric Kruskal–Wallis statistical analyses assessed if seedling abundance differed across quantile-based ranges of VPD and light based on seedling abundance. Kruskal–Wallis tests assessed differences in seedling abundance across low, medium, and high average VPD and average percent sun groups based on arbitrary bins. VPD and percent sun were evaluated separately. Bins for these groups were 0–0.3, 0.31–0.7, and 0.71–1, based on the percentile distribution of seedlings across VPD and percent sun. To determine data-driven optimal ranges of percent sun and VPD, LOESS predictions were used to identify and extract VPD and percent sun values correlated to the top 20% and 25% of predicted seedling abundance. Once optimal ranges were identified by LOESS predictions, each plot was classified as “optimal” or “nonoptimal” for VPD and percent sun.

Kruskal–Wallis and Wilcoxon rank-sum tests assessed differences in seedling abundance based on VPD and percent sun separately across these groups. Then, VPD and sun percent ranges were cross-classified into the groups “neither optimal,” “VPD optimal only,” “sun optimal only,” and “both optimal” to observe their combined effect on seedling abundance. Cross-classifications were performed to evaluate the variable combined effects on seedlings abundance. Kruskal–Wallis tests evaluated if seedling abundance differed across these ranges.

To assess whether fire severity influenced postfire microclimate, Kruskal–Wallis tests evaluated differences in average VPD and average percent sun across fire severity classes: low, moderate, and high. High severity was classified as >75% basal mortality [

24]. Then, using the determined optimal ranges, a targeted Wilcoxon-rank test directly compared “both optimal” and “neither optimal” groups to test the effect of jointly optimal microclimate conditions. To evaluate whether fire severity affected access to optimal microclimate conditions, the cross-classified groups were compared across severity using Kruskal–Wallis, and a chi-squared test evaluated independence between burn severity class and VPD and percent sun condition.

All data analyses were performed in R Studio Version 4.4.3 using the ggplot2 (v.3.5.2), ggpubr (v0.6.0), dplyr (v.1.1.4), patchwork (v.1.3.0), and FSA (v.0.10.0) packages. [

26,

27,

28,

29,

30]. The code is in the process of being made publicly available and can be requested from the corresponding author.

4. Discussion

Prioritizing natural regeneration and efficient postfire monitoring have become more urgent in the wake of intensifying severe wildfire seasons and increased risks of wildfires that increase rates of tree mortality. While VPD and percent sun measurements did not consistently differ across pre-assigned wildfire severity classes in these data, their relationship to seedling abundance did; VPD had a stronger relation to seedling abundance than percent sun at mid-elevation sites. These findings were consistent with morphological adaptations of conifers [

31], primarily Douglas fir in these data, that are typically shade-intolerant for establishment and growth, though they survive best with some cover to protect from herbivory and climate variability (optimal percent sun for conifer seedlings = 37.9%;

Figure 5). Conifers are similarly known to be drought-tolerant [

32]. Optimal VPD was above 1.00 Kpa, a point of reference for drought conditions (1.1–1.7 KPa) [

16]. Our measurements were taken during the dry season in Oregon and are consistent with other recordings in the area, though they do not reflect annual trends in VPD in relation to seedlings.

Moderate-severity fire has been shown to be most associated with high rates of conifer regeneration [

14]. This apparent relationship is likely due to the seed source requirement—while high-severity fire is more associated with optimal climate, overstory mortality may be too great in specific locations to provide sufficient seed for regeneration. Seed is susceptible to predation both before and after dispersal, and only a fraction of germinating seed become established seedlings in the wild under typical conditions. Therefore, abundant overstory seed trees are a prerequisite to overcome these probabilities [

10]. Retaining seed trees is also vital to survival, to provide cover and shelter seedling microclimate. Many of our high-severity wildfire sites had sufficient seed sources to yield natural regeneration within four years of the fire, suggesting that different thresholds might be used in future wildfire severity classifications (e.g., 95% basal area mortality).

4.1. Changing Wildfire Regimes and Impacts on Landscape Vegetation

Seedlings may not be able to properly establish, outcompete neighboring vegetation, and grow to a height and width that can withstand subsequent high-intensity fires such as those becoming more frequent in many parts of the world. As current trends of increasing global temperatures continue, we may see a threshold effect where the highly adaptive conifers of the Pacific Northwest can no longer adapt to their quickly changing surroundings.

Direct effects of wildfire on stand dynamics are dominated by near-term vegetation mortality. Indirect effects can also create a more hostile microclimate for regeneration from a limited seed source. The postfire environment may become unsuitable for regeneration, an indirect effect of increasing fire frequency [

10]. Optimal environments may become rarer as regions shift out of an optimal climate, encouraging unwanted landcover change.

Repeated severe wildfires can also boost the relative abundance of weedy annuals like

Chamaenerion angustifolium (fire weed), and invasive shrubs, including notably

Rubus armeniacus (Himalayan blackberry) and rapidly colonizing

Cytisus scoparius (scotch broom). Invasive plants tend to be annuals with short life cycles and, when they dry out each year, they create flashy fuels and enable quickly moving wildfire to catalyze the cycle over again. This provides little time for tree seedlings to establish and grow into saplings and mature trees that can withstand subsequent fire. When prioritizing hillsides affected by high-severity fire, mechanical fuel removal and invasive species management could be included in the site preparation methods before planting to increase long-term resilience. These observations are consistent with decades of monitoring changing fire regimes in the American West [

1].

Our findings display that there are multiple risks that come with changing fire regimes, supporting other work carried out in this study area [

14]. Fuel buildup, a lack of sustainable forest management, and the risks of increasing fire frequency and fire severity promote losses of overstory seed source trees and postfire environments that favor desired vegetation types [

10]. The feedback loop between forest fuels, wildfires, and climate change is one that necessitates further understanding, discussion, and intervention.

4.2. Considerations and Future Directions

Previous studies on climate optimality for seedlings have been limited to greenhouse studies [

33], whereas this work evaluates a small range of in situ postfire environments for seedling abundance tied to microclimate as part of a larger sample in one example wildfire. The importance of microclimate to seedling success is well recognized [

3,

4,

5,

11,

15,

16,

34] but using the relationship of microclimate to seedling abundance to target regeneration is a direction worth further consideration. This work contributed to the ecological understanding of forest regeneration and postfire conditions across varied severity.

Limitations of this study include both a small sample size and a short-term dataset collected four years after the wildfire. Active wildfires in the study area that year limited the sites available for assessment. Data was collected from June to August 2025. While this short window allowed for consistent snapshot data for VPD and percent sun with minimized seasonal variability, recording trends over time would allow for a more holistic vision of optimal climates to be generated [

15].

Future directions of this work would span over an entire season to capture rare microclimatic conditions or collect time series data to expand the list of potential microclimatic signals and/or to compare years. These sites could be revisited for continued census work to monitor seedling success as these stands develop, as climate conditions change, and as new wildfires appear. More complex ecological work evaluating soil moisture, soil respiration, leaf VPD, leaf moisture, and proximal remote sensing could explain ecological changes and phenomena even further. The scope of this study was to use simple techniques to increase the accessibility of repeatable results to be built upon with knowledge found in this work.

Some of the Holiday Farm fire footprint has already burned again, in the Lookout fire (2023) and Ore fire (2024), which could provide additional sample locations to capture the impact of repeated burning over short time intervals. Postfire (and pre-second-fire) monitoring of conifer regeneration can not only provide insight into ecological dynamics of seedling establishment but can also inform silvicultural decision making of what optimal seedling environments look like, to prioritize those areas for regeneration.

An integrated holistic approach is necessary in a changing climate and variable landscape experiencing variable wildfires [

5]. Long-term sustainable forest management cannot be evaluated solely by seedling success [

5,

14]. In complex postfire environments, the entire site must be considered and evaluated to truly understand the dynamics at play. For this reason, an integrated top–down approach is necessary. Our framework and initial data support this thinking. Once variables were combined and binned, more accurate relationships quickly became visible and explainable. Understanding wildfire impacts can lead to more resilient forest management and help repair the relationship between humans and wildland fire.