Effects of Two-Way Cold Rolling and Subsequent Annealing on the Microstructure and Tensile Properties of Low-Carbon Steel with Different Initial Microstructures

Abstract

1. Introduction

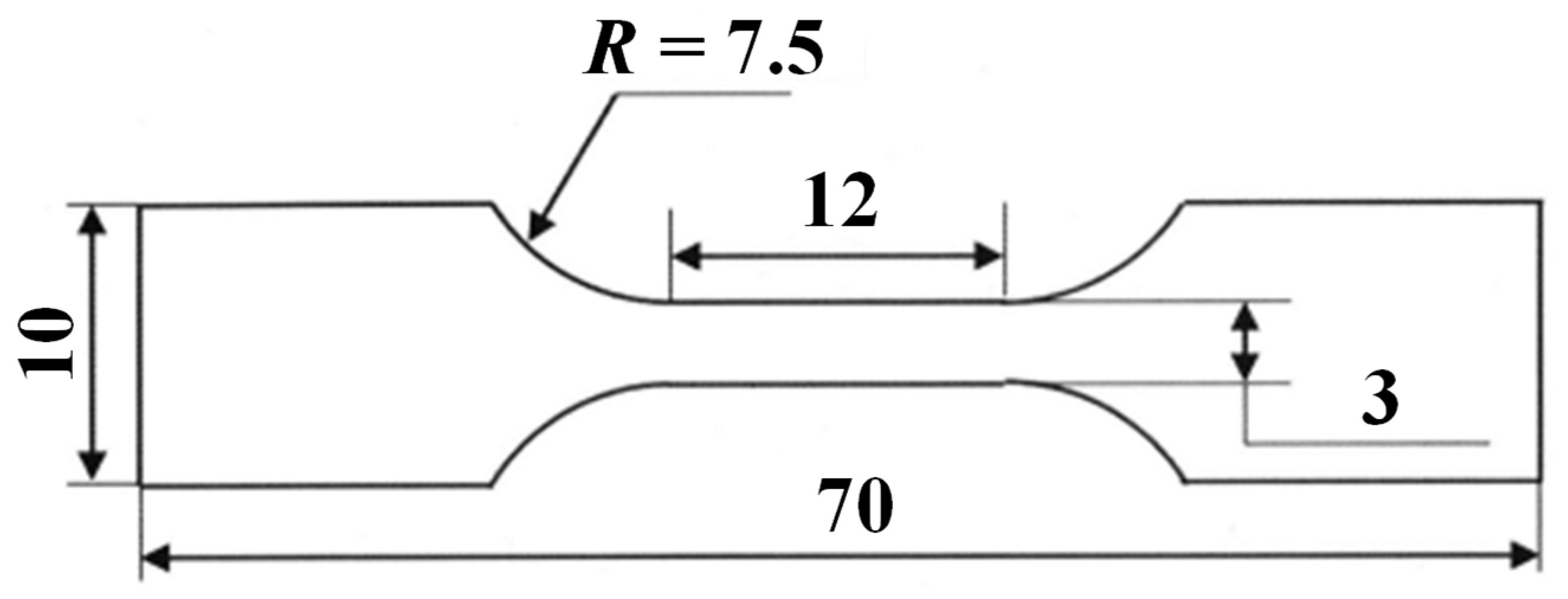

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results and Discussion

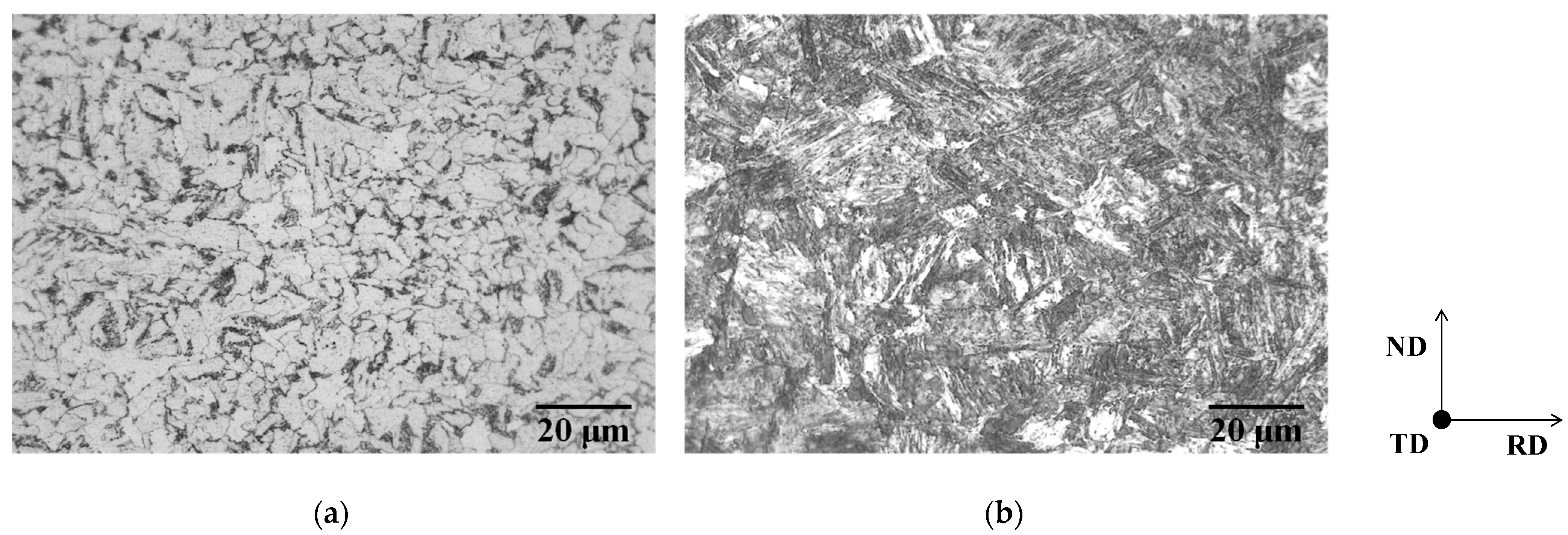

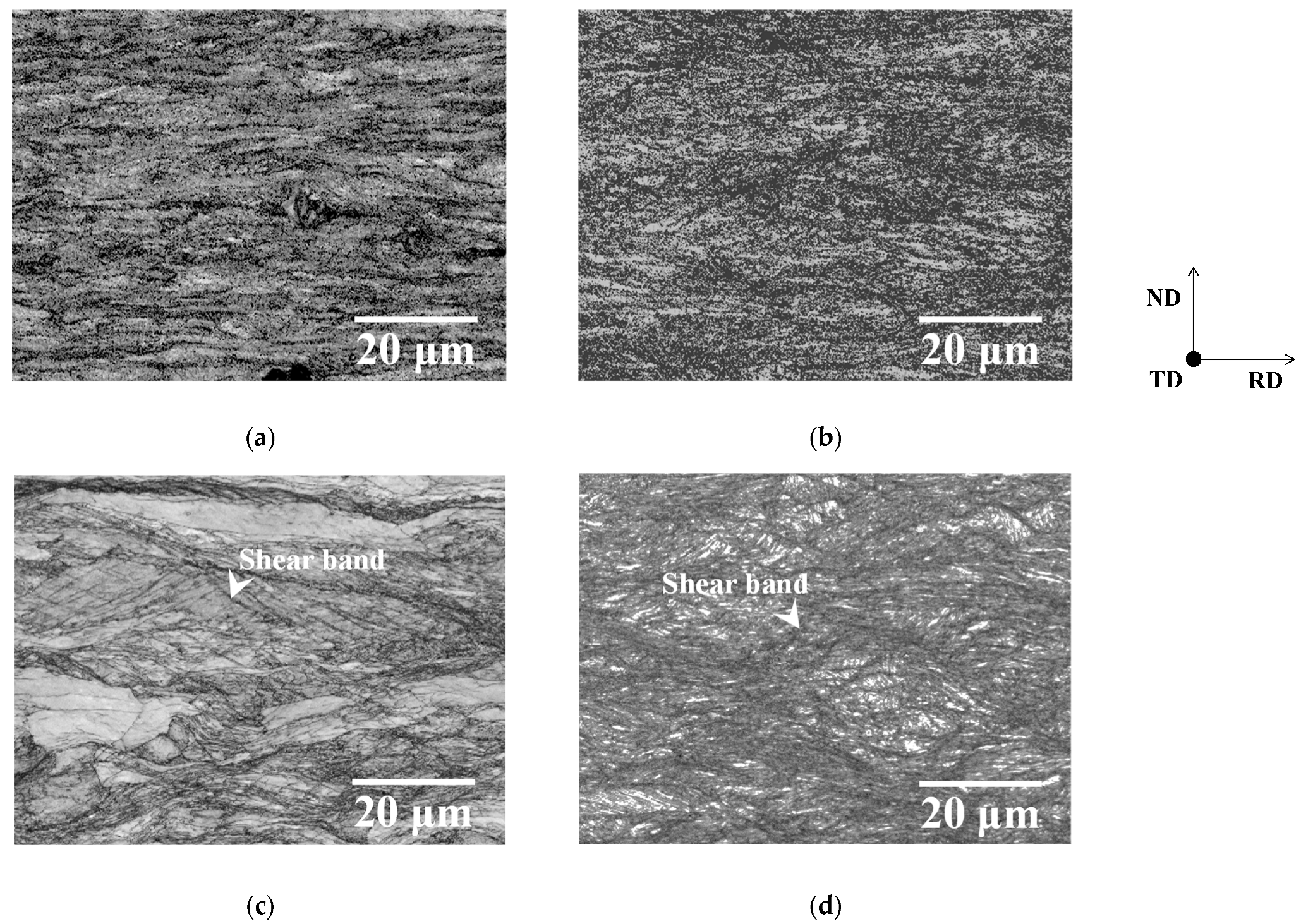

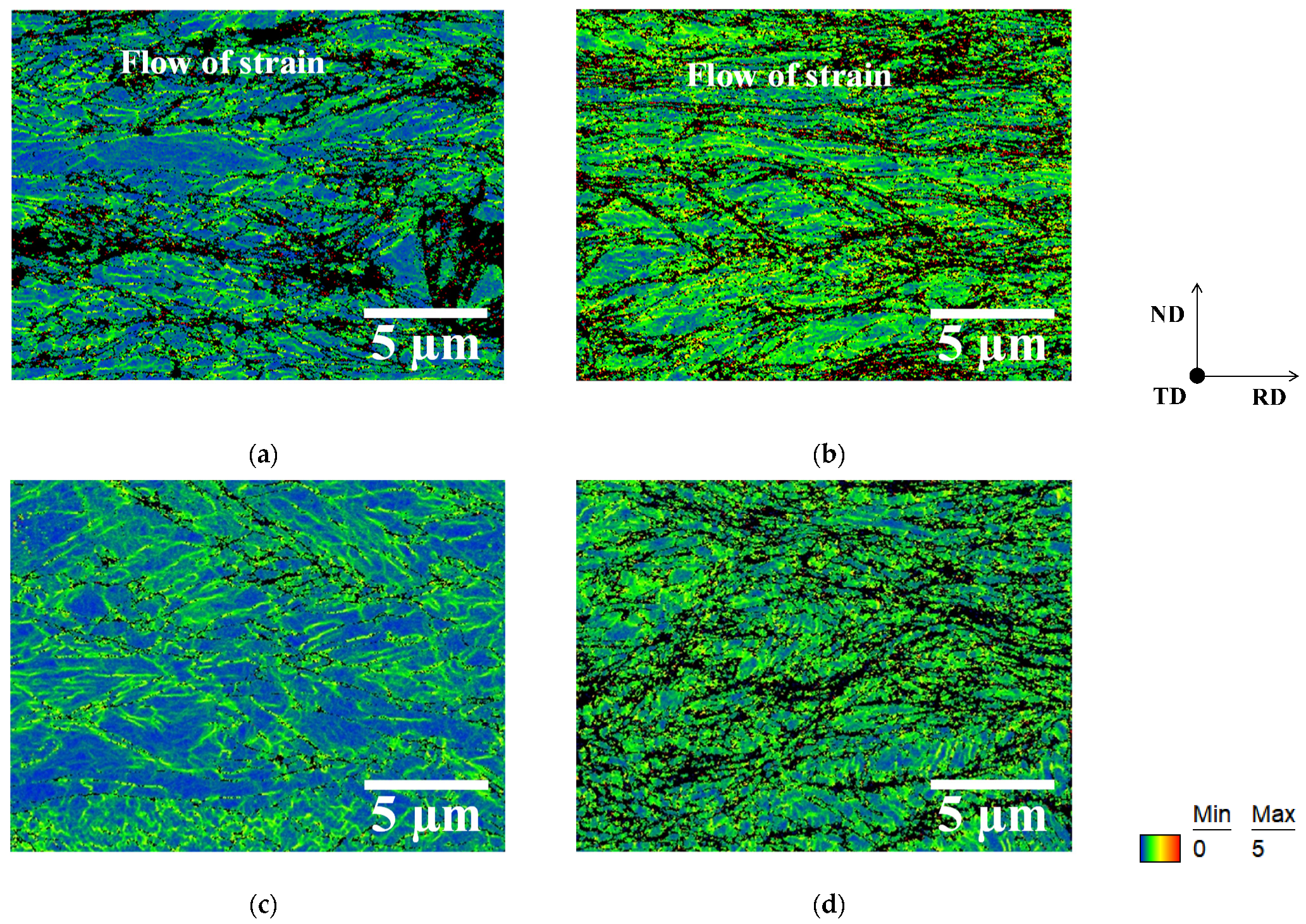

3.1. Microstructures and Textures of Two-Way Cold-Rolled Specimens

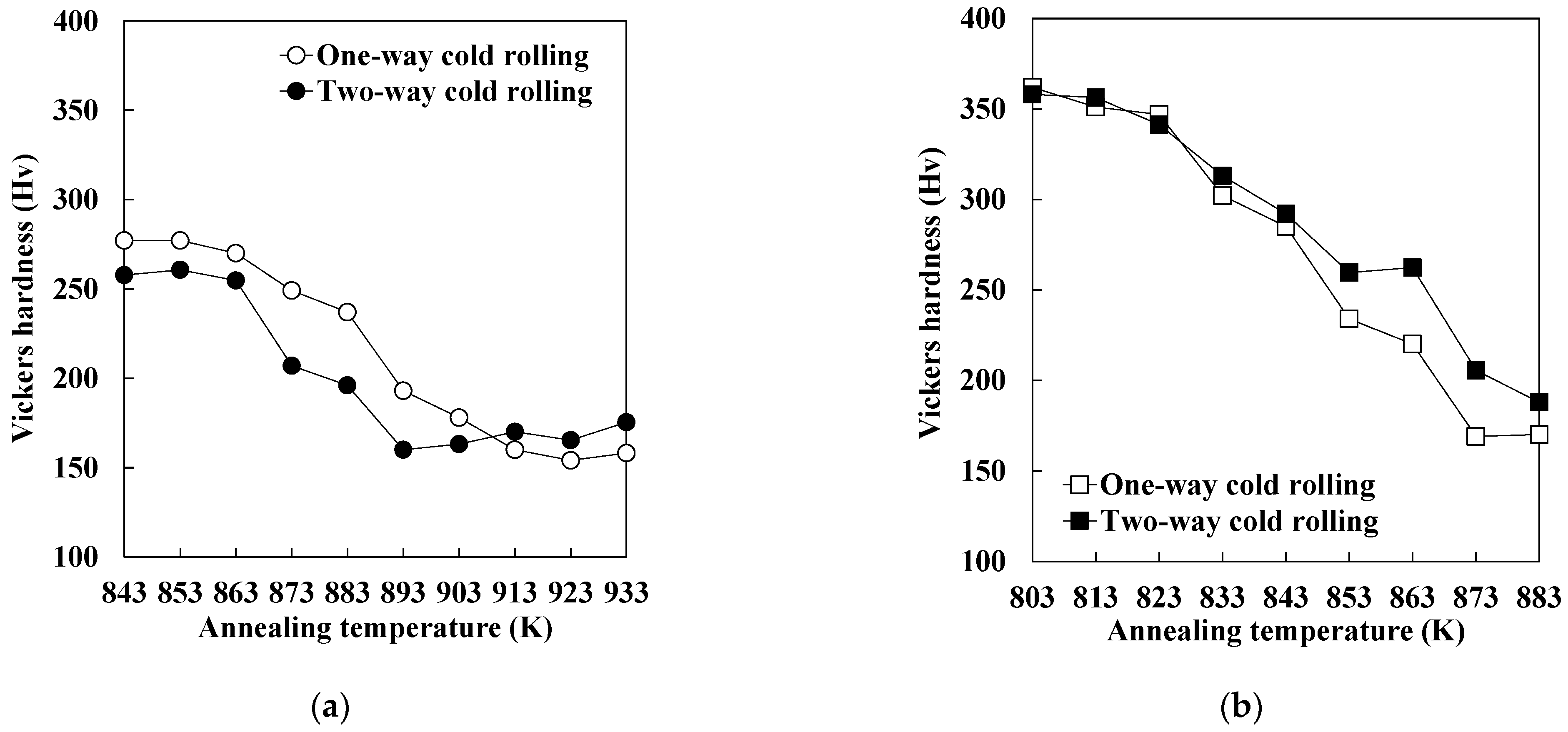

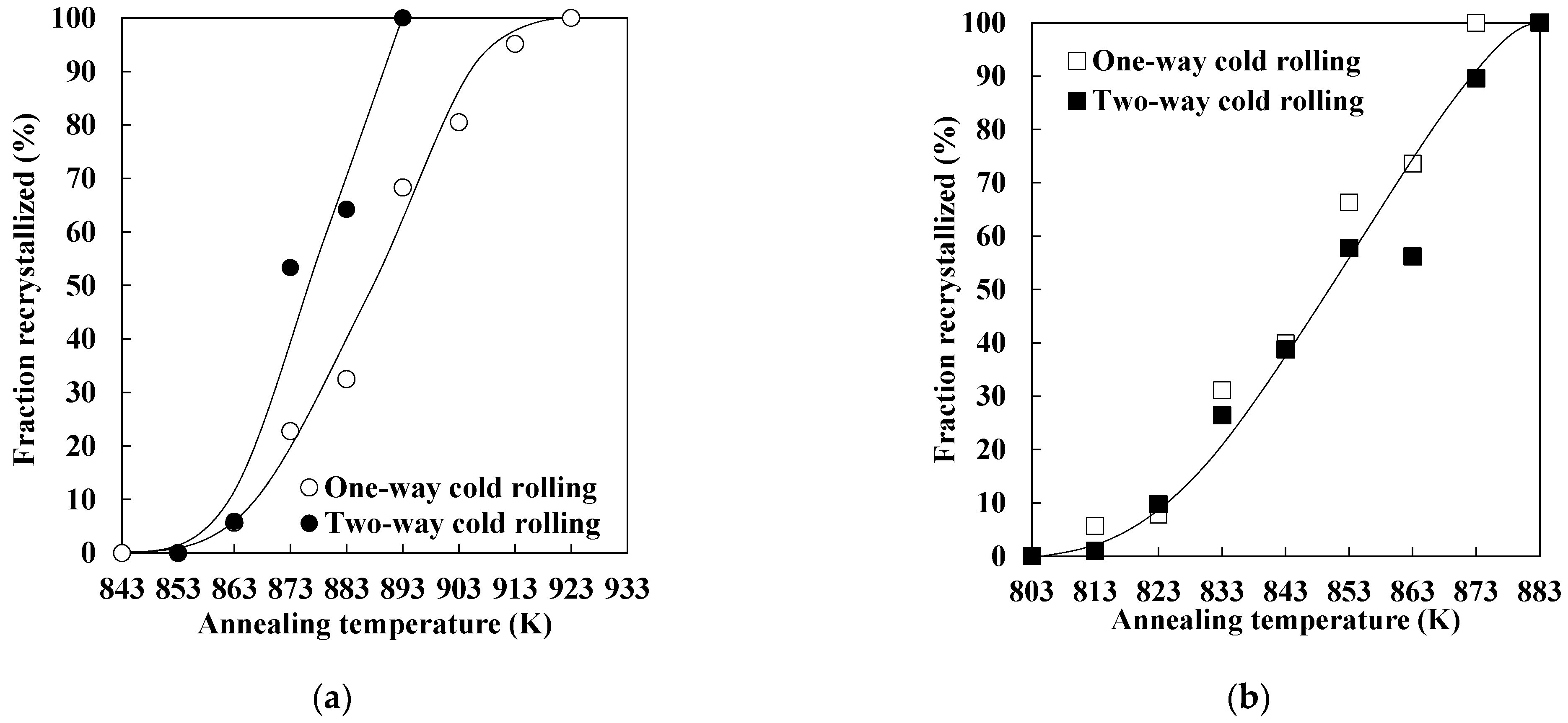

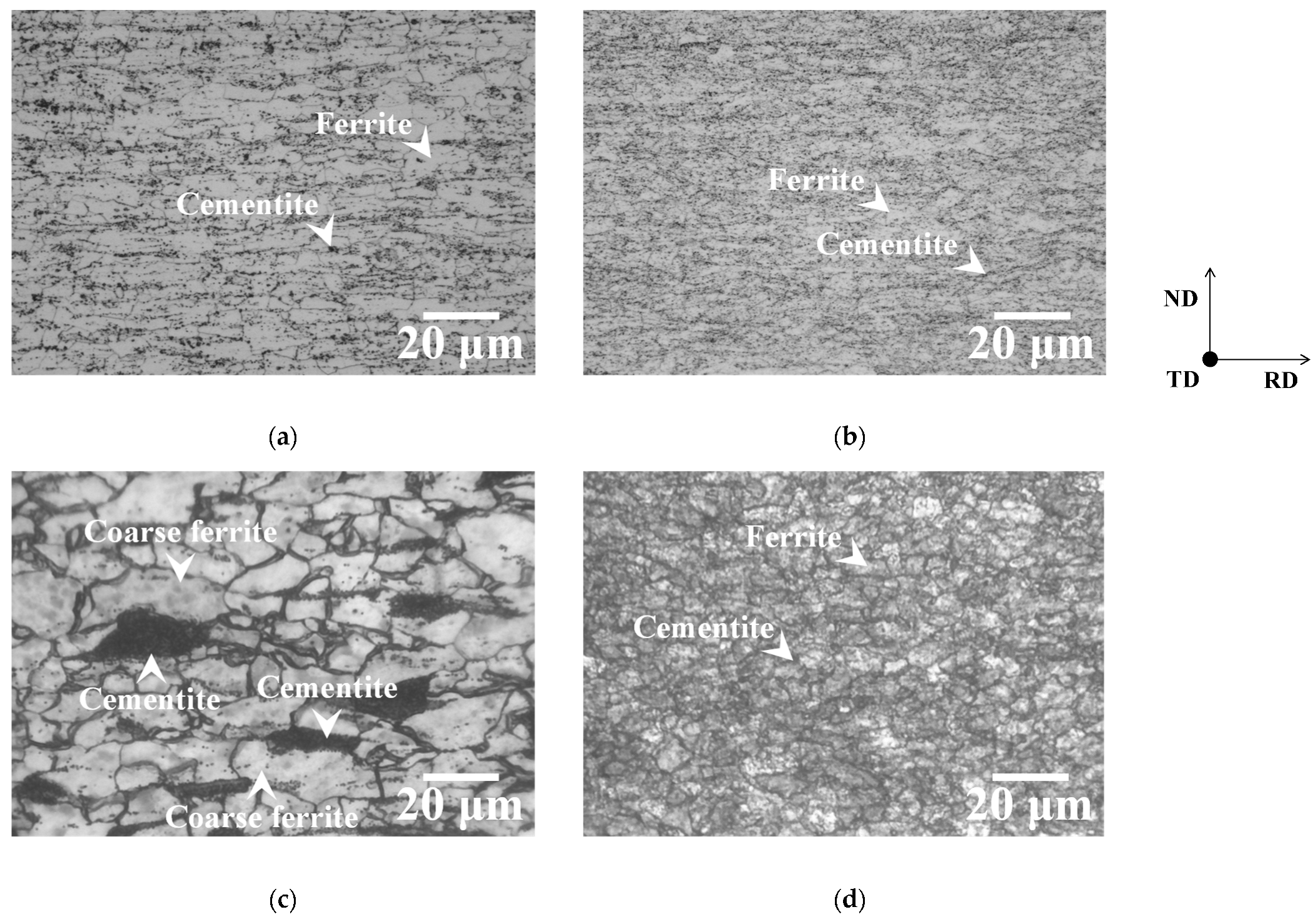

3.2. Microstructural Evolution During Annealing

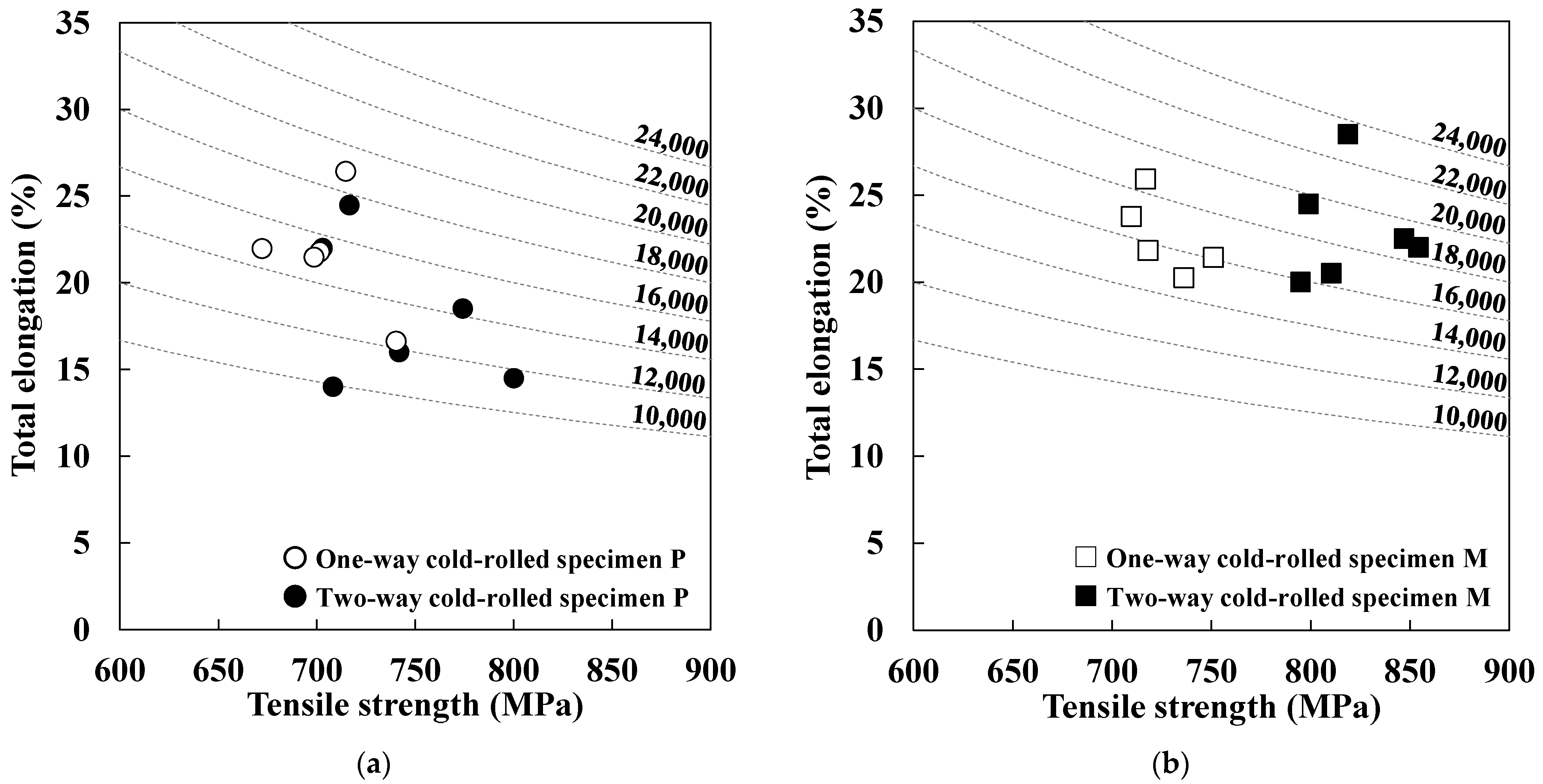

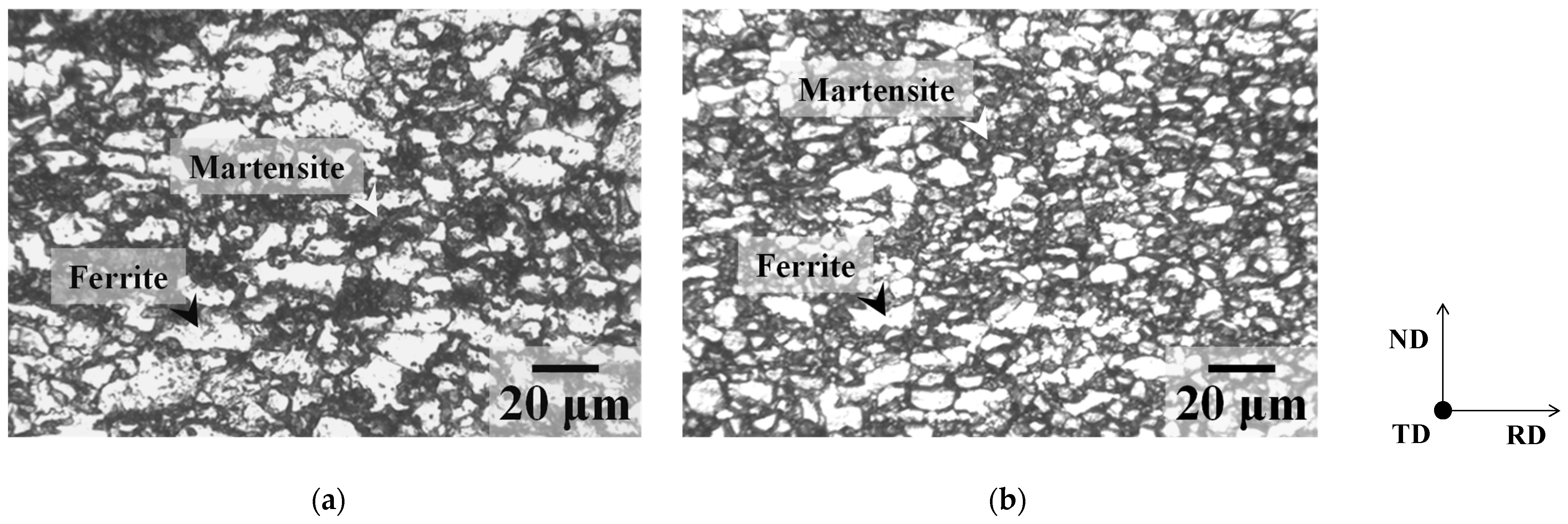

3.3. Microstructures and Tensile Properties of Intercritically Annealed Specimens

4. Conclusions

- (1)

- Two-way cold rolling accelerated the formation of shear bands. Furthermore, two-way cold-rolled specimens exhibited higher strain homogeneity than one-way cold-rolled specimens.

- (2)

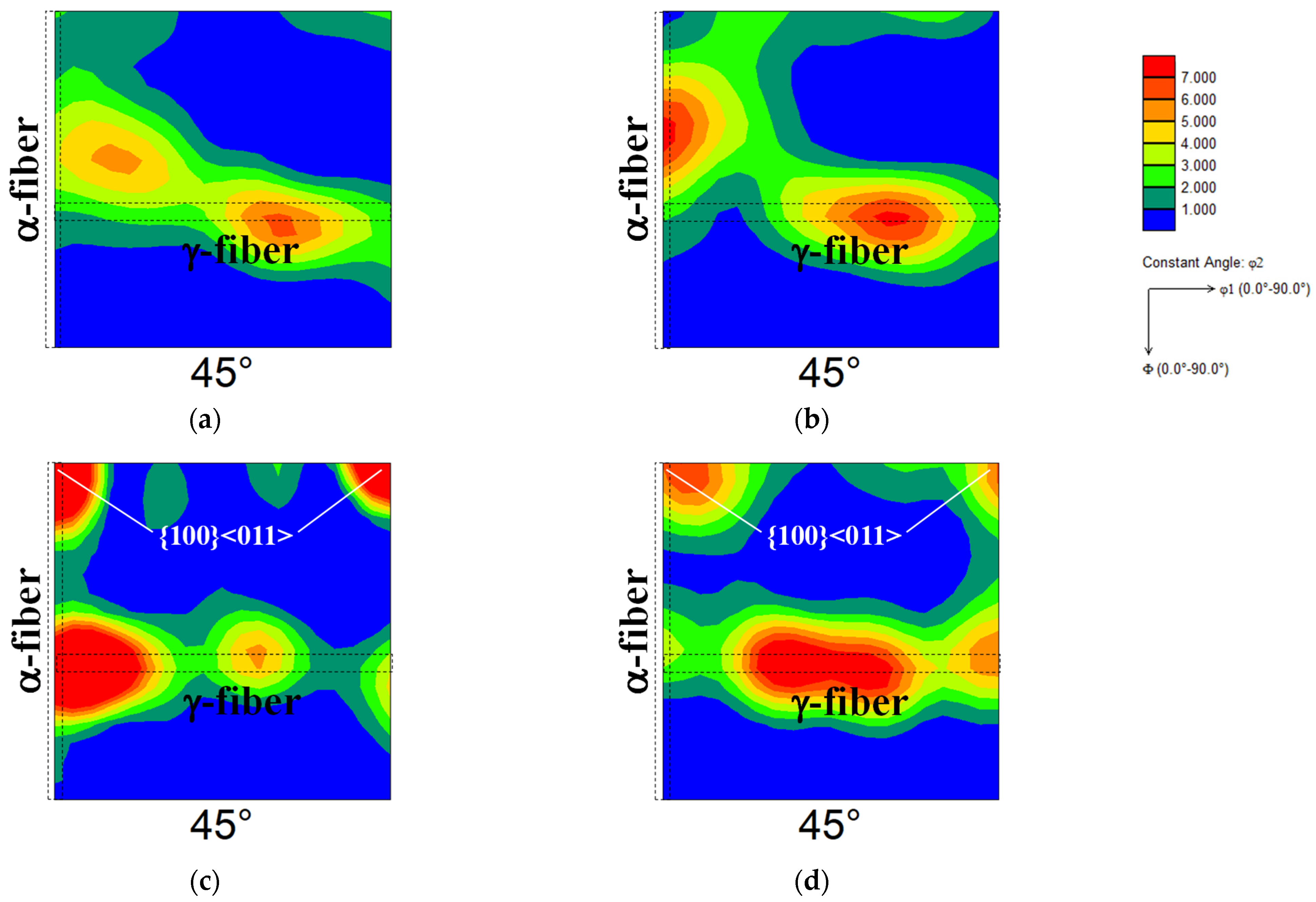

- In the two-way cold-rolled specimens, the formation of γ-fiber was observed, along with the development of the {100}<011> orientation.

- (3)

- Two-way cold rolling accelerated recrystallization during annealing in specimen P but not in specimen M. In the case of specimen P, two-way cold rolling increased the average size of recrystallized ferrite grains while reducing their aspect ratio. In contrast, it reduced the average size and the aspect ratio of recrystallized ferrite grains in specimen M.

- (4)

- In the case of intercritically annealed specimen P, the strength–ductility balance in the two-way cold-rolled specimen was similar to that in the one-way cold-rolled specimen. At the same time, in the case of intercritically annealed specimen M, the two-way cold-rolled specimen showed better strength–ductility balance than the one-way cold-rolled specimen.

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Takahashi, M. Sheet steel technology for the last 100 years: Progress in sheet steels in hand with the automotive industry. Tetsu-Hagané 2013, 100, 82–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hiwatashi, S. Autobody lightweighting and decarbonization with advanced high-strength steels. J. Surf. Finish. Soc. Jpn. 2022, 73, 390–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nonaka, T.; Fujita, N.; Taniguchi, H.; Tomokiyo, T.; Goto, K. Development of ultrahigh-strength steel sheets with excellent formabilities. Mater. Jpn. 2007, 46, 108–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamikawa, N.; Hirohashi, M.; Sato, Y.; Chandiran, E.; Miyamoto, G.; Furuhara, T. Tensile behavior of ferrite–martensite dual-phase steels with nano-precipitation of vanadium carbides. ISIJ Int. 2015, 55, 1781–1790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chandiran, E.; Sato, Y.; Kamikawa, N.; Miyamoto, G.; Furuhara, T. Effect of ferrite/martensite phase size on tensile behavior of dual-phase steels with nano-precipitation of vanadium carbides. Metall. Mater. Trans. A 2019, 50, 4111–4126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chandiran, E.; Kamikawa, N.; Sato, Y.; Miyamoto, G.; Furuhara, T. Improvement of strength–ductility balance by the simultaneous increase in ferrite and martensite strength in dual-phase steels. Metall. Mater. Trans. A 2021, 52, 5394–5408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calcagnotto, M.; Adachi, Y.; Ponge, D.; Raabe, D. Deformation and fracture mechanisms in fine- and ultrafine-grained ferrite/martensite dual-phase steels and the effect of aging. Acta Mater. 2011, 59, 658–670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ismail, K.; Perlade, A.; Jacques, P.J.; Pardoen, T.; Brassart, L. Impact of second phase morphology and orientation on the plastic behavior of dual-phase steels. Int. J. Plast. 2019, 118, 130–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, M.H.; Shibata, A.; Tsuji, N. Effect of grain size on mechanical properties of dual-phase steels composed of ferrite and martensite. MRS Adv. 2016, 1, 811–816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, J.; Kim, S.; Lee, Y. Grain refinement of dual-phase steel for simultaneous enhancement of strength and ductility. Acta Mater. 2025, 292, 121061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ogawa, T.; Dannoshita, H.; Maruoka, K.; Ushioda, K. Microstructural evolution during cold rolling and subsequent annealing in low-carbon steel with different initial microstructures. J. Mater. Eng. Perform. 2017, 26, 3821–3830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ogatsu, K.; Ogawa, T.; Chen, T.T.; Sun, F.; Adachi, Y. Dramatic improvement in strength–ductility balance of dual-phase steels by optimizing features of ferrite phase. J. Mater. Res. Technol. 2025, 35, 289–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ogawa, T.; Suzuki, Y.; Adachi, Y.; Yamaguchi, A.; Matsubara, Y. Effect of cold-rolling directions on recrystallization texture evolution of pure iron. Materials 2022, 15, 3083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Umezaki, S.; Murata, Y.; Nomura, K.; Kubushiro, K. Quantitative analysis of dislocation density in an austenitic steel after plastic deformation. J. Jpn. Inst. Met. Mater. 2014, 78, 218–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ogawa, T.; Hishikawa, R.; Adachi, Y. Effect of cold reduction rate on ferrite recrystallization behavior during annealing in low-carbon steel with different initial microstructures. Mater. Sci. Forum 2021, 1016, 1045–1050. [Google Scholar]

- Sanjari, M.; He, Y.; Hilinski, E.J.; Yue, S.; Kestens, L.A.I. Texture evolution during skew cold rolling and annealing of a non-oriented electrical steel containing 0.9 wt% silicon. J. Mater. Sci. 2017, 52, 3281–3300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nave, M.D.; Barnett, M.R.; Beladi, H. The influence of solute carbon in cold-rolled steels on shear band formation and recrystallization texture. ISIJ Int. 2004, 44, 1072–1078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tomita, M.; Inaguma, T.; Sakamoto, H.; Ushioda, K. Development of recrystallization texture in severely cold-rolled pure iron. ISIJ Int. 2016, 56, 693–699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gobernado, P.; Petrov, R.H.; Kestens, L.A.I. Recrystallized {311}⟨136⟩ orientation in ferrite steels. Scr. Mater. 2012, 66, 623–626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dannoshita, H.; Ogawa, T.; Yamashita, T.; Harjo, S.; Umezawa, O. Role of dislocation characteristics on the recrystallization of martensite in a low-carbon steel. In Proceedings of the FEMS EUROMAT 2023, Frankfurt am Main, Germany, 3–7 September 2023. [Google Scholar]

| C | Si | Mn | P | S | Nb | Al | N | O |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0.10 | <0.003 | 2.03 | 0.010 | 0.0029 | <0.003 | 0.027 | 0.0030 | <0.001 |

| Fraction (%) | Average Size (μm) | Aspect Ratio | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| One-way [12] | Specimen P | 54.9 | 5.52 | 2.68 |

| Specimen M | 57.2 | 3.47 | 1.88 | |

| Two-way | Specimen P | 59.8 | 7.98 | 1.88 |

| Specimen M | 56.9 | 3.08 | 1.66 | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Ogawa, T.; Hayashi, H.; Dannoshita, H. Effects of Two-Way Cold Rolling and Subsequent Annealing on the Microstructure and Tensile Properties of Low-Carbon Steel with Different Initial Microstructures. Materials 2026, 19, 466. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma19030466

Ogawa T, Hayashi H, Dannoshita H. Effects of Two-Way Cold Rolling and Subsequent Annealing on the Microstructure and Tensile Properties of Low-Carbon Steel with Different Initial Microstructures. Materials. 2026; 19(3):466. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma19030466

Chicago/Turabian StyleOgawa, Toshio, Hidetomo Hayashi, and Hiroyuki Dannoshita. 2026. "Effects of Two-Way Cold Rolling and Subsequent Annealing on the Microstructure and Tensile Properties of Low-Carbon Steel with Different Initial Microstructures" Materials 19, no. 3: 466. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma19030466

APA StyleOgawa, T., Hayashi, H., & Dannoshita, H. (2026). Effects of Two-Way Cold Rolling and Subsequent Annealing on the Microstructure and Tensile Properties of Low-Carbon Steel with Different Initial Microstructures. Materials, 19(3), 466. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma19030466