Enhancing the Quality of Diamond Film Growth Through the Synergistic Addition of Nitrogen and Carbon Dioxide

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

3. Result and Discussion

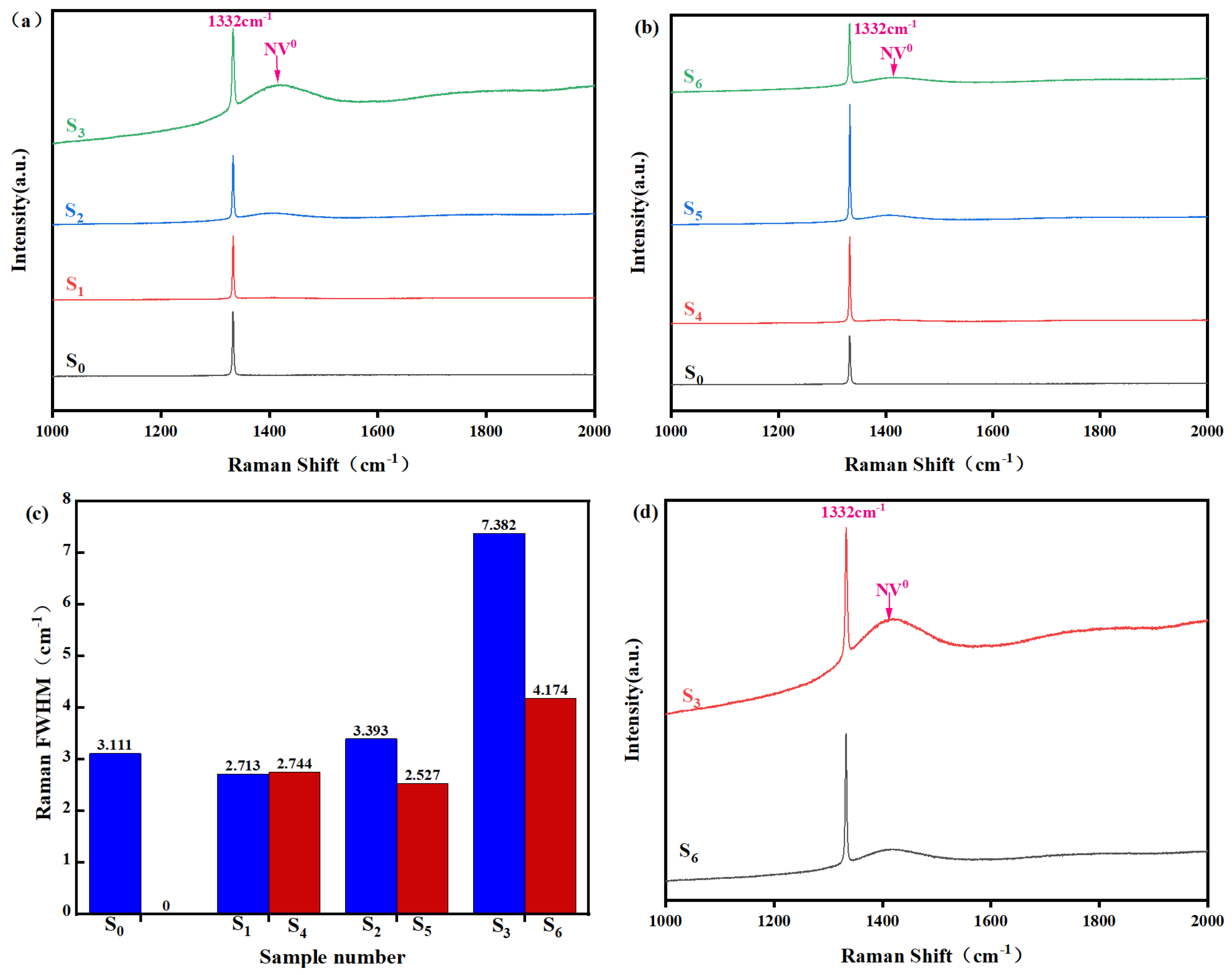

3.1. Diamond Film Growth Rate and Its Quality

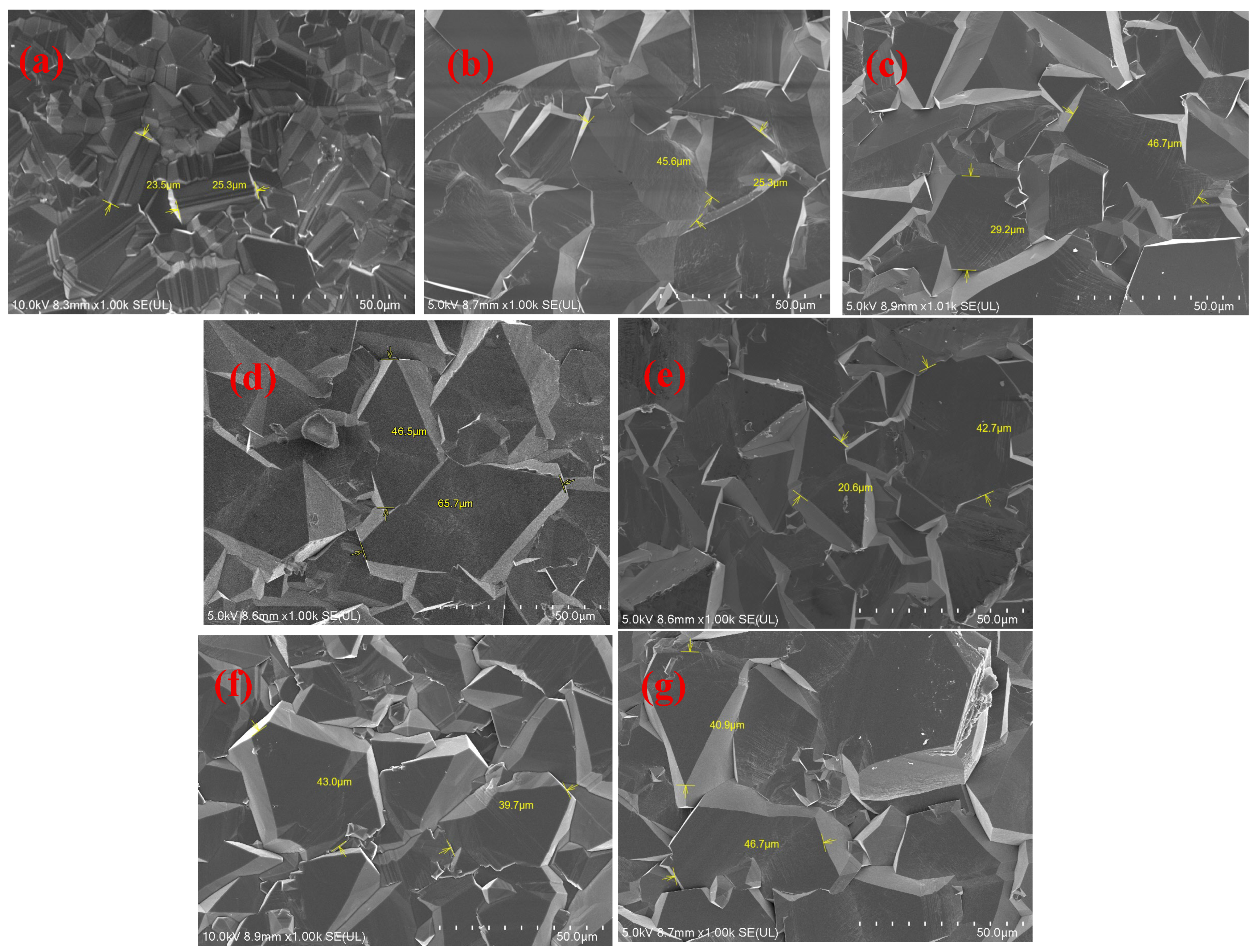

3.2. Microstructural Analysis

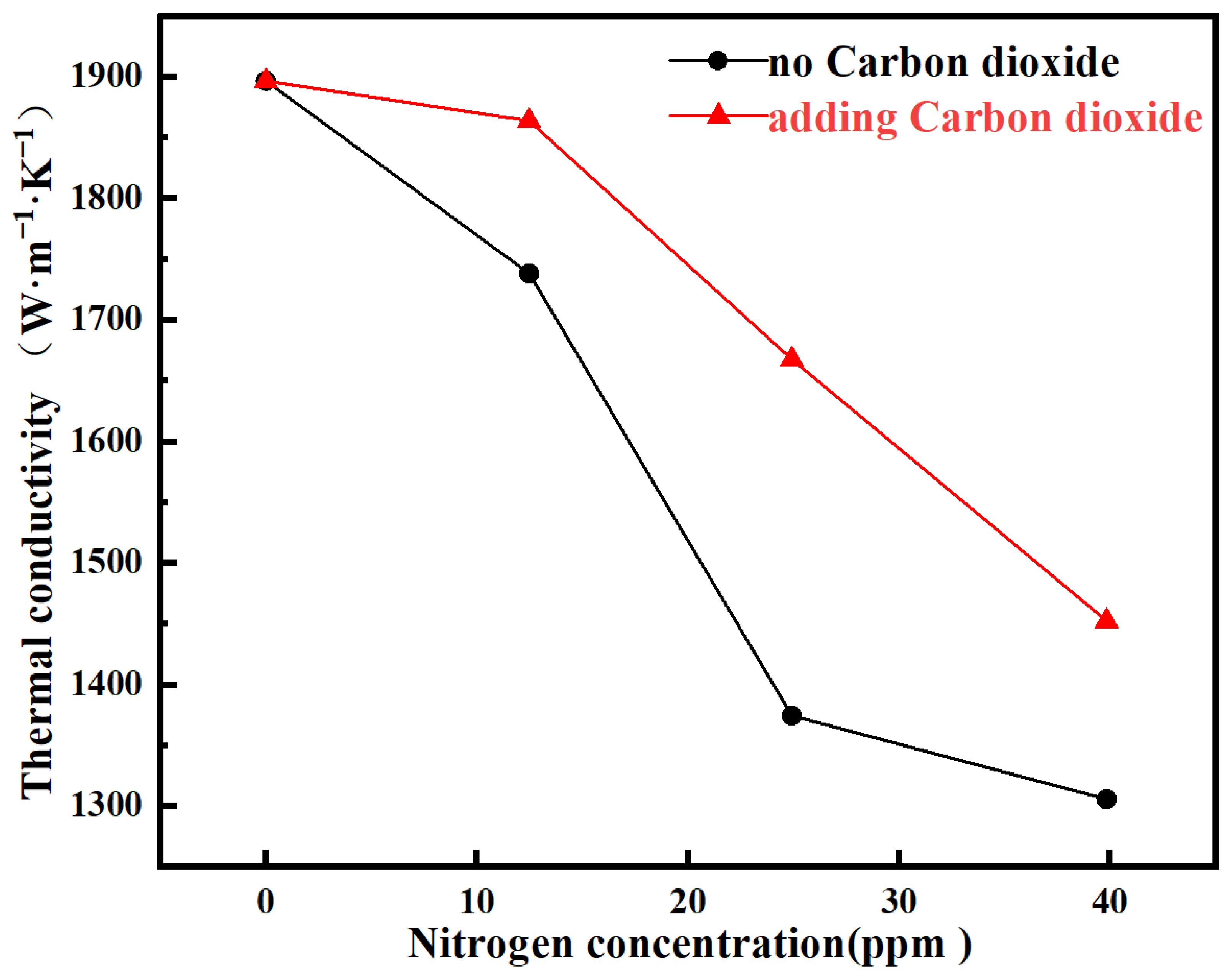

3.3. Thermodynamic Properties of Diamond Materials

4. Conclusions

- Advantage of introducing trace amounts of carbon dioxide: This study successfully demonstrates that the co-doping strategy utilizing N2 and CO2 during MPCVD growth is a highly effective method for fabricating high-quality, optical-grade polycrystalline diamond films. This approach ingeniously leverages the dual functions of N2 in promoting growth rate and CO2 in purifying the crystal lattice.

- Performance Optimization: Employing this method enabled the attainment of diamond films featuring high thermal conductivity (1863.94 W·m−1·K−1) and a highly <111>-textured morphology, while maintaining a high growth rate (~3–4 µm/h) and effectively mitigating defects introduced by nitrogen impurities.

- Defect Control Mechanism: The introduction of CO2, through its etching action, significantly reduces the concentration of complex defects such as NV colour centres and alleviates lattice strain. This mechanism is identified as the fundamental reason for the observed enhancements in both thermal conductivity and optical properties.

- Application Prospect: This work provides an effective solution to the long-standing challenge of reconciling crystal quality with performance in nitrogen-doped diamond. The fabricated ultra-low nitrogen-doped diamond films exhibit broad application prospects in fields such as high-efficiency thermal management.

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Wu, K.; Chang, G.; Ye, J.; Zhang, G. Significantly Enhanced Interfacial Thermal Conductance across GaN/Diamond Interfaces Utilizing AlxGa1–xN as a Phonon Bridge. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2024, 16, 58880–58890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, S.; Yang, L.; Dai, B.; Geng, F.; Ralchenko, V.; Han, J.; Zhu, J. Past Achievements and Future Challenges in the Development of Infrared Antireflective and Protective Coatings. Phys. Status Solidi (a) 2020, 217, 2000149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kotomin, E.A.; Kuzovkov, V.N.; Lushchik, A.; Popov, A.I.; Shablonin, E.; Scherer, T.; Vasil’chenko, E. The Annealing Kinetics of Defects in CVD Diamond Irradiated by Xe Ions. Crystals 2024, 14, 546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaboli, S.; Burnley, P.C. Direct observations of crystal defects in polycrystalline diamond. Mater. Charact. 2018, 142, 154–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mussi, A.; Eyidi, D.; Shiryaev, A.; Rabier, J. TEM observations of dislocations in plastically deformed diamond. Phys. Status Solidi (a) 2012, 210, 191–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mizuochi, N.; Ogura, M.; Watanabe, H.; Isoya, J.; Okushi, H.; Yamasaki, S. EPR study of hydrogen-related defects in boron-doped p-type CVD homoepitaxial diamond films. Diam. Relat. Mater. 2004, 13, 2096–2099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mizuochi, N.; Watanabe, H.; Isoya, J.; Okushi, H.; Yamasaki, S. Hydrogen-related defects in single crystalline CVD homoepitaxial diamond film studied by EPR. Diam. Relat. Mater. 2004, 13, 765–768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alvarez, J.; Kleider, J.P.; Bergonzo, P.; Tromson, D.; Snidero, E.; Mer, C. Study of deep defects in polycrystalline CVD diamond from thermally stimulated current and below-gap photocurrent experiments. Diam. Relat. Mater. 2003, 12, 546–549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, F.; Hassouni, K.; Bonnin, X.; Gicquel, A. Microwave engineering of plasma-assisted CVD reactors for diamond deposition. J. Phys. Condens. Matter 2009, 21, 364202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, Y.; Liu, K.; Liu, B.; Li, Y.; Fan, S.; Dai, B.; Zhang, Y.; Zhu, J. Vapor phase nucleation and sedimentation of dispersed nanodiamonds by MPCVD. Powder Technol. 2024, 436, 119507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamada, H.; Chayahara, A.; Mokuno, Y.; Soda, Y.; Horino, Y.; Fujimori, N. Modeling and numerical analyses of microwave plasmas for optimizations of a reactor design and its operating conditions. Diam. Relat. Mater. 2005, 14, 1776–1779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teng, Y.; Yang, K.; Tang, K.; Zhao, W.; Gu, L.; Zhao, G.; Zhu, S.; Ye, J.; Gu, S. The regulation mechanism of oxygen additives on diamond growth and residual boron by microwave plasma chemical vapor deposition. Diam. Relat. Mater. 2025, 160, 113065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.-L.; Lu, X.-Y.; Li, L.-A.; Cheng, S.-H.; Li, H.-D. Growth and Characteristics of Freestanding Hemispherical Diamond Films by Microwave Plasma Chemical Vapor Deposition. Chin. Phys. Lett. 2010, 27, 047802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Z.; An, K.; Liu, Y.; Guo, Z.; Shao, S.; Liu, J.; Wei, J.; Chen, L.; Wu, L.; Li, C. Edge effect during microwave plasma chemical vapor deposition diamond-film: Multiphysics simulation and experimental verification. Int. J. Miner. Metall. Mater. 2024, 31, 2287–2299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, G.; Sun, P.; Zhu, T.; Wang, Y.; Li, S.; Liu, C.; Yang, G.; Yang, K.; Yang, X.; Lian, W.; et al. Fabrication, microstructure and optical properties of <110> textured CVD polycrystalline diamond infrared materials. Diam. Relat. Mater. 2024, 141, 110600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashkinazi, E.; Khmelnitskii, R.; Sedov, V.; Khomich, A.; Khomich, A.; Ralchenko, V. Morphology of Diamond Layers Grown on Different Facets of Single Crystal Diamond Substrates by a Microwave Plasma CVD in CH4-H2-N2 Gas Mixtures. Crystals 2017, 7, 166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Izak, T.; Babchenko, O.; Varga, M.; Potocky, S.; Kromka, A. Low temperature diamond growth by linear antenna plasma CVD over large area. Phys. Status Solidi (b) 2012, 249, 2600–2603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, D.-Y.; Tang, K.; Zhu, S.-M.; Rong, Z.; Zheng, Y.-D.; Shu-Lin, G. Effects of oxygen/nitrogen co-incorporation on regulation of growth and properties of boron-doped diamond films. Chin. Phys. B 2023, 32, 118102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giussani, A.; Janssens, S.D.; Vázquez-Cortés, D.; Fried, E. Evolution of nanodiamond seeds during the chemical vapor deposition of diamond on silicon substrates in oxygen-rich plasmas. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2022, 581, 152103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, Y.; Zhang, E.; Wang, J.; Shen, H.; Lei, X. Effect of oxygen doping on cutting performance of CVD diamond coated milling cutters in zirconia ceramics machining. Int. J. Refract. Met. Hard Mater. 2024, 124, 106853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, G.; Tang, K.; Teng, Y.; Zhao, W.; Yang, K.; Zhu, S.; Gu, S. The regulation effect of trace amount of oxygen on the properties of p-type boron-doped diamond. J. Mater. Res. 2024, 39, 1313–1323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Podgursky, V.; Bogatov, A.; Sedov, V.; Sildos, I.; Mere, A.; Viljus, M.; Buijnsters, J.G.; Ralchenko, V. Growth dynamics of nanocrystalline diamond films produced by microwave plasma enhanced chemical vapor deposition in methane/hydrogen/air mixture: Scaling analysis of surface morphology. Diam. Relat. Mater. 2015, 58, 172–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.; An, K.; Xu, G.; Wu, H.; Yang, Z.; Xi, Z.; Liu, P.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, X.; et al. Twins and dark features in MPCVD diamond films. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2025, 701, 163222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yiming, Z.; Larsson, F.; Larsson, K. Effect of CVD diamond growth by doping with nitrogen. Theor. Chem. Acc. 2013, 133, 1432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- dos Santos, R.B.; Rivelino, R.; Mota, F.d.B.; Gueorguiev, G.K. Effects of N doping on the electronic properties of a small carbon atomic chain with distinctsp2terminations: A first-principles study. Phys. Rev. B 2011, 84, 075417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashfold, M.N.R.; Mankelevich, Y.A. Two-dimensional modeling of diamond growth by microwave plasma activated chemical vapor deposition: Effects of pressure, absorbed power and the beneficial role of nitrogen on diamond growth. Diam. Relat. Mater. 2023, 137, 110097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.X.; Zhang, H.D.; Li, C.M.; Chen, G.C.; Lu, F.X.; Tang, W.Z.; Tong, Y.M. Effects of nitrogen addition on morphology and mechanical property of DC arc plasma jet CVD diamond films. Diam. Relat. Mater. 2004, 13, 139–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, X.; Wei, J.; An, K.; Liu, J.; Chen, L.; Zheng, Y.; Zhang, X.; Li, C. High temperature surface graphitization of CVD diamond films and analysis of the kinetics mechanism. Diam. Relat. Mater. 2021, 120, 108647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ager, J.W.; Drory, M.D. Quantitative measurement of residual biaxial stress by Raman spectroscopy in diamond grown on a Ti alloy by chemical vapor deposition. Phys. Rev. B 1993, 48, 2601–2607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gries, T.; Vandenbulcke, L.; Simon, P.; Canizares, A. Anisotropic biaxial stresses in diamond films by polarized Raman spectroscopy of cubic polycrystals. J. Appl. Phys. 2008, 104, 023524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haddad, M.; Kurtulus, O.; Mertens, M.; Brühne, K.; Glüche, P.; Fecht, H. Optimization of residual stresses inside diamond thin films grown by hot filament chemical vapor deposition (HFCVD). Diam. Relat. Mater. 2023, 131, 109564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, W.V.; Sorokin, P.P.; Gelles, I.L.; Lasher, G.J. Electron-Spin Resonance of Nitrogen Donors in Diamond. Phys. Rev. 1959, 115, 1546–1552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tarun, A.; Lee, S.J.; Yap, C.M.; Finkelstein, K.D.; Misra, D.S. Impact of impurities and crystal defects on the performance of CVD diamond detectors. Diam. Relat. Mater. 2016, 63, 169–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, X.; Wang, J.; Li, X.; Wei, X.; Yang, Q.; He, Z.; Qi, H.; Zhang, B.; Meng, D.; Liang, Z.; et al. Preparation of step-flow grown diamond films and directionally oriented NV center ensembles. Diam. Relat. Mater. 2025, 156, 112387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tallaire, A.; Collins, A.T.; Charles, D.; Achard, J.; Sussmann, R.; Gicquel, A.; Newton, M.E.; Edmonds, A.M.; Cruddace, R.J. Characterisation of high-quality thick single-crystal diamond grown by CVD with a low nitrogen addition. Diam. Relat. Mater. 2006, 15, 1700–1707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krell, A.; Klimke, J.; Hutzler, T. Transparent compact ceramics: Inherent physical issues. Opt. Mater. 2009, 31, 1144–1150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Zhang, Q.; Li, B.; Chen, Z.; Liu, S.; Ma, X.; Tofil, S.; Yao, J. Effect of Laser on the Interface and Thermal Conductivity of Metallized Diamond/Cu Composite Coatings Deposited by Supersonic Laser Deposition. Materials 2024, 17, 5174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, M.; Tan, Z.; Huang, Y.; Huang, Z.; Liu, X.; Zhang, K. Preparation and interfacial microstructure of high thermal conductivity diamond/SiC composites. Ceram. Int. 2024, 50, 23754–23762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, N.K.; Omar, M.S.; Yousf, S.O. On the nitrogen concentration and crystal size dependence of lattice thermal conductivity in diamond thin and nanofilms. Diam. Relat. Mater. 2025, 155, 112340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Samples | H2/sccm | CH4/sccm | MN/sccm | CO2/sccm | Power/kw | Pressure/Torr | Temperature/°C |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| S0 | 400 | 12 | 0 | 0 | 3.8 | 100 | 850 ± 10 |

| S1 | 400 | 0.5 | 0 | ||||

| S2 | 400 | 1 | 0 | ||||

| S3 | 400 | 1.6 | 0 | ||||

| S4 | 400 | 0.5 | 1 | ||||

| S5 | 400 | 1 | 1 | ||||

| S6 | 400 | 1.6 | 1 |

| Schemes | Thickness/μm | Growth Rate μm/h |

|---|---|---|

| S0 | 45 | 1.125 |

| S1 | 84 | 2.100 |

| S2 | 111 | 2.775 |

| S3 | 139 | 3.475 |

| S4 | 95 | 2.375 |

| S5 | 125 | 3.125 |

| S6 | 150 | 3.750 |

| Samples | Raman Shift/cm−1 | Residual Stress/GPa |

|---|---|---|

| S0 | 1332.64 | −0.69 |

| S1 | 1333.45 | −1.57 |

| S2 | 1333.18 | −1.27 |

| S3 | 1333.25 | −1.35 |

| S4 | 1333.21 | −1.31 |

| S5 | 1333.08 | −1.17 |

| S6 | 1332.91 | −0.98 |

| Samples | Thermal Diffusivity/mm2·S | Thermal Conductivity/W·m−1·K−1 |

|---|---|---|

| S0 | 1038.34 | 1896.93 |

| S1 | 951.61 | 1738.47 |

| S2 | 752.39 | 1374.52 |

| S3 | 714.79 | 1305.84 |

| S4 | 1020.29 | 1863.94 |

| S5 | 912.86 | 1667.69 |

| S6 | 795.14 | 1452.63 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Sheng, Z.; Cui, X.; Zhao, L.; Lv, Y.; Zhang, R.; Kon, D.; Jiang, N.; Yi, J.; Zheng, L. Enhancing the Quality of Diamond Film Growth Through the Synergistic Addition of Nitrogen and Carbon Dioxide. Materials 2026, 19, 183. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma19010183

Sheng Z, Cui X, Zhao L, Lv Y, Zhang R, Kon D, Jiang N, Yi J, Zheng L. Enhancing the Quality of Diamond Film Growth Through the Synergistic Addition of Nitrogen and Carbon Dioxide. Materials. 2026; 19(1):183. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma19010183

Chicago/Turabian StyleSheng, Zhanpeng, Xuejian Cui, Lei Zhao, Yihan Lv, Rongchen Zhang, Defang Kon, Nan Jiang, Jian Yi, and Lingxia Zheng. 2026. "Enhancing the Quality of Diamond Film Growth Through the Synergistic Addition of Nitrogen and Carbon Dioxide" Materials 19, no. 1: 183. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma19010183

APA StyleSheng, Z., Cui, X., Zhao, L., Lv, Y., Zhang, R., Kon, D., Jiang, N., Yi, J., & Zheng, L. (2026). Enhancing the Quality of Diamond Film Growth Through the Synergistic Addition of Nitrogen and Carbon Dioxide. Materials, 19(1), 183. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma19010183