Effect of Nano-TiO2 Addition on Some Properties of Pre-Alloyed CoCrMo Fabricated via Powder Technology

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

2.2. Experimental Procedures

2.3. Dry Sliding Wear Test

3. Results and Discussion

4. Conclusions

- The nanocomposites are fruitfully made up utilizing CCMA with several additions of TiO2 nanoparticles via PMR.

- No drop in the hardness of CCMA was detected when TiO2 nanoparticles were added. In contrast, its value increased slightly with the addition of nanoparticles.

- The porosity was increased due to nanoparticle addition, and this will enhance the utilization of the nanocomposite in biomedical applications, such as bone fixation.

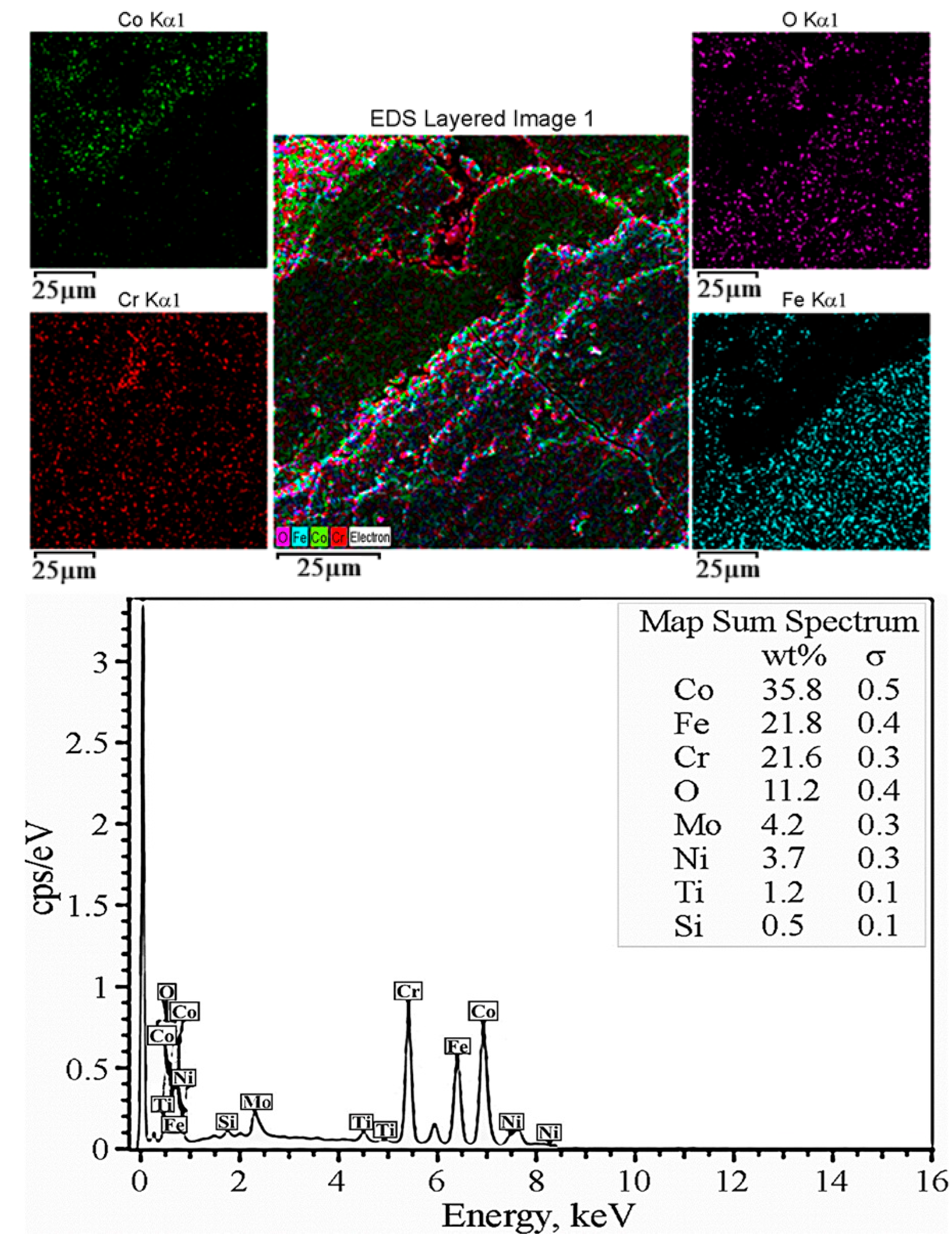

- Even though TiO2 nanoparticles moderately isolated the pressed powder particles of CCMA, it does not stop the creation of Cr2O3 among the particles, which is revealed from the existence of Cr and O elements within the CCMA particles and at their boundaries.

- The wear resistance of CCMA is improved at the lowest nano-TiO2 particle addition, while the wear rate increased and became more than that of the base CCMA; hence, if the wear resistance is the main requirement of the prepared nanocomposite, then the addition amount must be at the stated lowest quantity, which is 1 wt% TiO2 particle addition.

- Wear particle debris analysis explained the formation of debris particles with different sizes and irregular shapes. Also, it indicated the creation of wear for the tested CCMA sample under the test conditions, mainly by the adhesion process.

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| CCMA | CoCrMo alloy |

| ρg | Green compact density (g/cm3) |

| EDS | Energy-dispersive X-ray spectroscopy |

| GC | Green compact |

| ρM | ρCo, ρCr, ρMo, ρSi, ρMn, and ρTiO2 |

| Mc | Green compacted sample mass (gm) |

| NP | Nanoparticle |

| PMR | Powder metallurgy route |

| POD | Pin-on-disk |

| PSD | Particie size distribution |

| PTR | Powder technology route |

| SC | Sintered compact |

| SEM | Scanning electron microscopy |

| TP | Total porosity |

| Vg | Green compacted sample volume (cm3) |

| XM | (XCo, XCr, XMo, XSi and XMn) and TiO2%wt |

| XRD | X-ray diffraction |

References

- Moretoa, J.A.; Rodriguesa, A.C.; da Silva Leiteb, R.R.; Rossia, A.; da Silvaa, L.A.; Alvesa, V.A. Effect of Temperature, Electrolyte Composition and Immersion Time on the Electrochemical Corrosion Behavior of CoCrMo Implant Alloy Exposed to Physiological Serum and Hank’s Solution. Mater. Res. 2018, 21, e20170659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaman, H.A.; Sharif, S.; Kim, D.W.; Idris, M.H.; Suhaimi, M.A.; Tumurkhuyag, Z. Machinability of Cobalt-based and Cobalt Chromium Molybdenum Alloys—A Review. Procedia Manuf. 2017, 11, 563–570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bettini, E.; Leygraf, C.; Pan, J. Nature of Current Increase for a CoCrMo Alloy: “transpassive” Dissolution vs. Water Oxidation. Int. J. Electrochem. Sci. 2013, 8, 11791–11804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamid, M.H.A.; Fadzil, F.S.M.; Selamat, M.A.; Ahmad, M.A. Sintering Effects on the Microstructure and Mechanical Properties of CoCrMo Alloy. Adv. Mater. Res. 2016, 1133, 259–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mathe, J.; Cheng, K.Y.; Bijukumar, D.; Barba, M.; Pourzal, R.; Neto, M.; Mathew, M.T. Hip implant modular junction: The role of CoCrMo alloy microstructure on fretting-corrosion. J. Mech. Behav. Biomed. Mater. 2022, 134, 105402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Radice, S.; Neto, M.Q.; Fischer, N.A.; Wimmer, M.A. Nickel-free high-nitrogen austenitic steel outperforms CoCrMo alloy regarding tribocorrosion in simulated inflammatory synovial fluids. J. Orthop. Res. 2022, 40, 1397–1408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Man, K.; Mazumder, S.; Dahotre, N.B.; Yang, Y. Surface Nanostructures Enhanced Biocompatibility and Osteoinductivity of Laser-Additively Manufactured CoCrMo Alloys. ACS Omega 2023, 8, 47658–47666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Döring, J.; Basten, S.; Ecke, M.; Herbster, M.; Kirsch, B.; Halle, T.; Lohmann, C.H.; Bertrand, J.; Aurich, J. Surface integrity modification of CoCrMo alloy by deep rolling in combination with sub-zero cooling as potential implant application. J. Biomed. Mater. Res. Part B Appl. Biomater. 2023, 111, 946–957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bombač, D.; Brojan, M.; Fajfar, P.; Kosel, F.; Turk, R. Review of materials in medical applications. Mater. Geoenvironment 2007, 54, 471–499. [Google Scholar]

- De La Cruz, L.G.; Alvaredo, P.; Torralba, J.M.; Campos, M. Improvement of Mechanical Properties of CoCrMo Alloys through Microstructure Engineering using Powder Metallurgy. J. Jpn. Soc. Powder Powder Metall. 2025, 72, S1221–S1225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahyudin, F.; Hermawan, H. Biomaterials and Medical Devices, a Perspective from an Emerging Country; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2016; pp. 5–7. [Google Scholar]

- Peaubuapuan, C.; Tunthawiroon, P.; Kanlayasiri, K.; Yuangyai, C. Effect of Si on Microstructure and Corrosion Behavior of CoCrMo Alloys. IOP Conf. Ser. Mater. Sci. Eng. 2018, 361, 012004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oksiuta, Z.; Dabrowski, J.R.; Olszyna, A. Co-Cr-Mo-based composite reinforced with bioactive glass. J. Mater. Process. Technol. 2009, 209, 978–985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abbass, M.K.; Yagoob, J.A. Wear Behavior and Mechanism of CoCrMo Alloy Fabricated by Powder Metallurgy Route. IOP Conf. Ser. Mater. Sci. Eng. 2019, 518, 032009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abbass, M.K.; Yagoob, J.A. Effect of A-Al2O3 Nanoparticles Addition On Some Properties Of Cocrmo Alloy Fabricated By Powder Metallurgy Route. Iraqi J. Mech. Mater. Eng. 2020, 20, 47–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abbass, M.K.; Yagoob, J.A. Influence of Al2O3 nanoparticles on the corrosion behavior of biomedical CoCrMo alloy in Ringer’s solution. AIP Conf. Proc. 2023, 2787, 020003. [Google Scholar]

- Cui, G.; Han, J.; Wu, G. High-temperature wear behavior of self-lubricating Co matrix alloys prepared by P/M. Wear 2016, 346–347, 116–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Deen, D.H.J.J.; Hobihaleem, A.; Khilfe, A.H. Studying the Properties of CoCrMo (F75) Doped Y Using (P-M) Technique. Int. J. Metall. Mater. Chem. Eng. 2016, 1, 11–20. [Google Scholar]

- Haleem, A.H.; Haydar, H.J.; Al-Deen, J.; Khilfa, A.H. Studying the Properties of CoCrMo Alloys (F75) Doped Ge Using (Powder Metalluregy) Technique. J. Babylon Univ./Eng. Sci. 2016, 24, 723–729. [Google Scholar]

- Abdullah, R.; Adzali, N.M.S.; Daud, Z.C. Bioactivity of a Bio-composite Fabricated from CoCrMo/Bioactive Glass by Powder Metallurgy Method for Biomedical Application. Procedia Chem. 2016, 19, 566–570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grądzka-Dahlke, M.; Dąbrowski, J.R.; Dąbrowski, B. Modification of mechanical properties of sintered implant materials on the base of Co–Cr–Mo alloy. J. Mater. Process. Technol. 2008, 204, 199–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, P.; Huang, T.; Zheng, Z.; Sun, L.; Du, W.; Su, G. Photocatalytic Degradation of Cresol Red in Wastewater Using Nanometer TiO2. Adv. Mater. Res. 2013, 643, 174–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tok, A.I.Y.; Boey, F.Y.C.; Zhao, X.L. Novel synthesis of TiO2 nano-particles by flame spray pyrolysis. J. Mater. Process. Technol. 2006, 178, 270–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lingaraju, K.; Basavaraj, R.B.; Jayanna, K.; Bhavana, S.; Devaraja, S.; Swamy, H.K.; Nagaraju, G.; Nagabhushana, H.; Naika, H.R. Biocompatible fabrication of TiO2 nanoparticles: Antimicrobial, anticoagulant, antiplatelet, direct hemolytic and cytotoxicity properties. Inorg. Chem. Commun. 2021, 127, 108505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Irfan, S.; Ali, H.; Aman, N.; Gao, C.; Qiao, Z.; Sun, H.; Amir, J.; Shah, A.; Kashif, M.; Aman, N. Biomedical Applications of Titanium Dioxide (TiO2) Nanoparticles. Phytopharm. Res. J. 2024, 3, 29–40. [Google Scholar]

- Yagoob, J.A.; Abbass, M.K. Characterization of Cobalt Based CoCrMo Alloy Fabricated by Powder Metallurgy Route. In Proceedings of the 2nd International Conference for Engineering, Technology and Sciences of Al-Kitab (ICETS), Karkuk, Iraq, 4–6 December 2018; pp. 1–5. [Google Scholar]

- ASTM E384-17; Standard Test Method for Microindentation Hardness of Materials. ASTM International: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2017.

- Fadzil, A.F.b.A.; Pramanik, A.; Basak, A.; Prakash, C.; Shankar, S. Role of surface quality on biocompatibility of implants—A review. Ann. 3D Print. Med. 2022, 8, 100082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bandyopadhyay, A.; Mitra, I.; Goodman, S.B.; Kumar, M.; Bose, S. Improving biocompatibility for next generation of metallic implants. Prog. Mater. Sci. 2023, 133, 101053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chawla, N.; Chawla, K.K. Metal Matrix Composites; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2006; p. 340. [Google Scholar]

- Ameen, H.A.; Hassan, K.S.; Mubarak, E.M.M. Effect of loads, sliding speeds and times on the wear rate for different materials. Am. J. Sci. Ind. Res. 2011, 2, 99–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohapatra, S.; Mishra, D.K.; Mishra, G.; Roy, G.S.; Behera, D.; Mantry, S.; Singh, S.K. A study on sintered TiO2 and TiO2/SiC composites synthesized through chemical reaction-based solution method. J. Compos. Mater. 2012, 47, 3081–3089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yadav, P.; Beniwal, G.; Saxena, K.K. A review on pore and porosity in tissue engineering. Mater. Today Proc. 2021, 44, 2623–2628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levashov, E.; Kurbatkina, V.; Alexandr, Z. Improved Mechanical and Tribological Properties of Metal-Matrix Composites Dispersion-Strengthened by Nanoparticles. Materials 2010, 3, 97–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Property | μ | σ | CV% | Interpretation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hardness | 339.95 | 6.380178 | 1.877 | Very low variability |

| Porosity | 21.162 | 4.331567 | 20.461 | moderate variability |

| Ra | 0.448 | 0.154868 | 34.569 | High variability |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Yagoob, J.A.; Wahhab, M.S.; Najm, S.M.; Oleksik, M.; Trzepieciński, T.; Mohammed, S.O. Effect of Nano-TiO2 Addition on Some Properties of Pre-Alloyed CoCrMo Fabricated via Powder Technology. Materials 2026, 19, 186. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma19010186

Yagoob JA, Wahhab MS, Najm SM, Oleksik M, Trzepieciński T, Mohammed SO. Effect of Nano-TiO2 Addition on Some Properties of Pre-Alloyed CoCrMo Fabricated via Powder Technology. Materials. 2026; 19(1):186. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma19010186

Chicago/Turabian StyleYagoob, Jawdat Ali, Mahmood Shihab Wahhab, Sherwan Mohammed Najm, Mihaela Oleksik, Tomasz Trzepieciński, and Salwa O. Mohammed. 2026. "Effect of Nano-TiO2 Addition on Some Properties of Pre-Alloyed CoCrMo Fabricated via Powder Technology" Materials 19, no. 1: 186. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma19010186

APA StyleYagoob, J. A., Wahhab, M. S., Najm, S. M., Oleksik, M., Trzepieciński, T., & Mohammed, S. O. (2026). Effect of Nano-TiO2 Addition on Some Properties of Pre-Alloyed CoCrMo Fabricated via Powder Technology. Materials, 19(1), 186. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma19010186