Review of the Relationship Between the Composition, Strength, and Ultimate Tensile Strain of Engineering Geopolymer Composites

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Composition of EGC

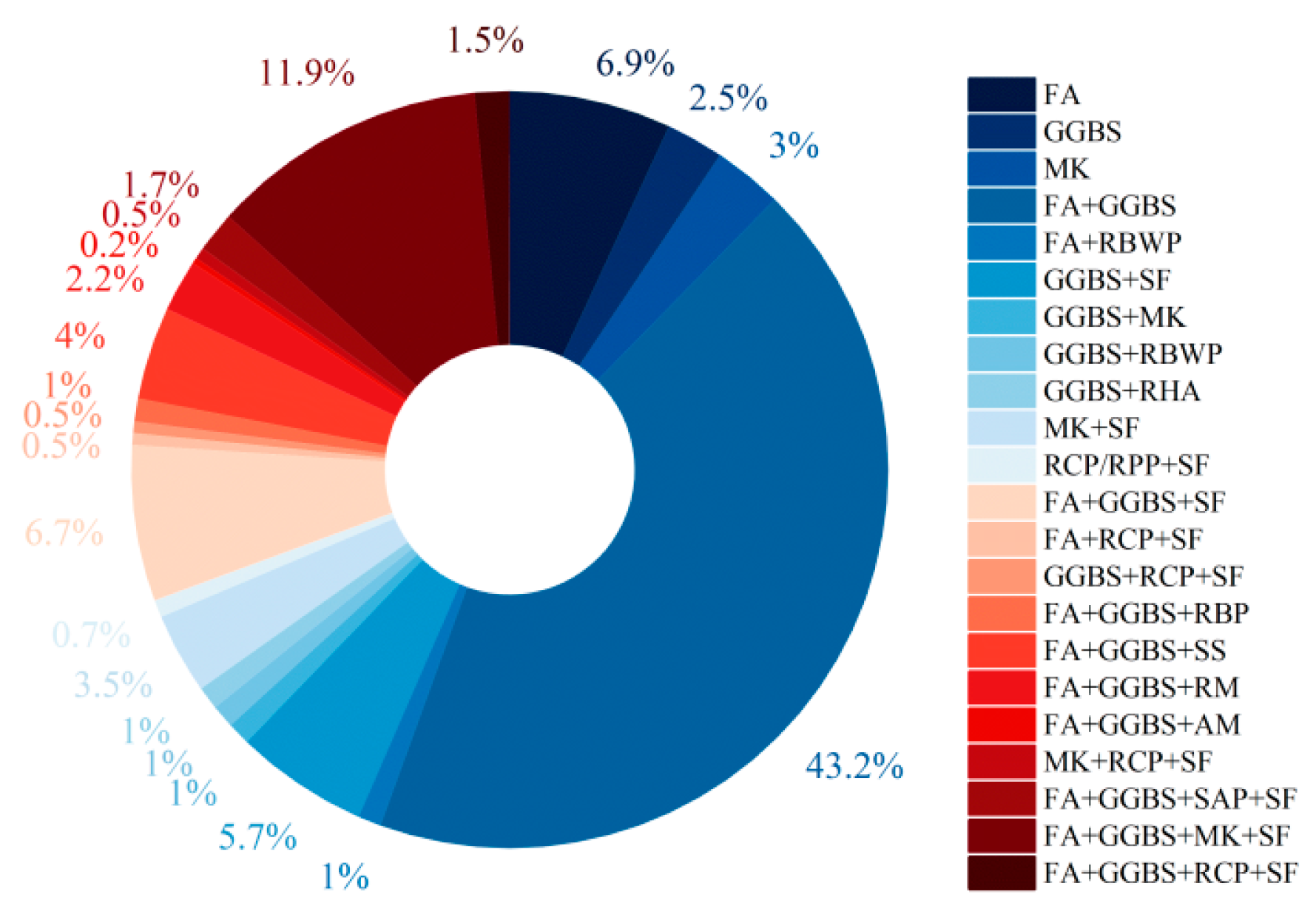

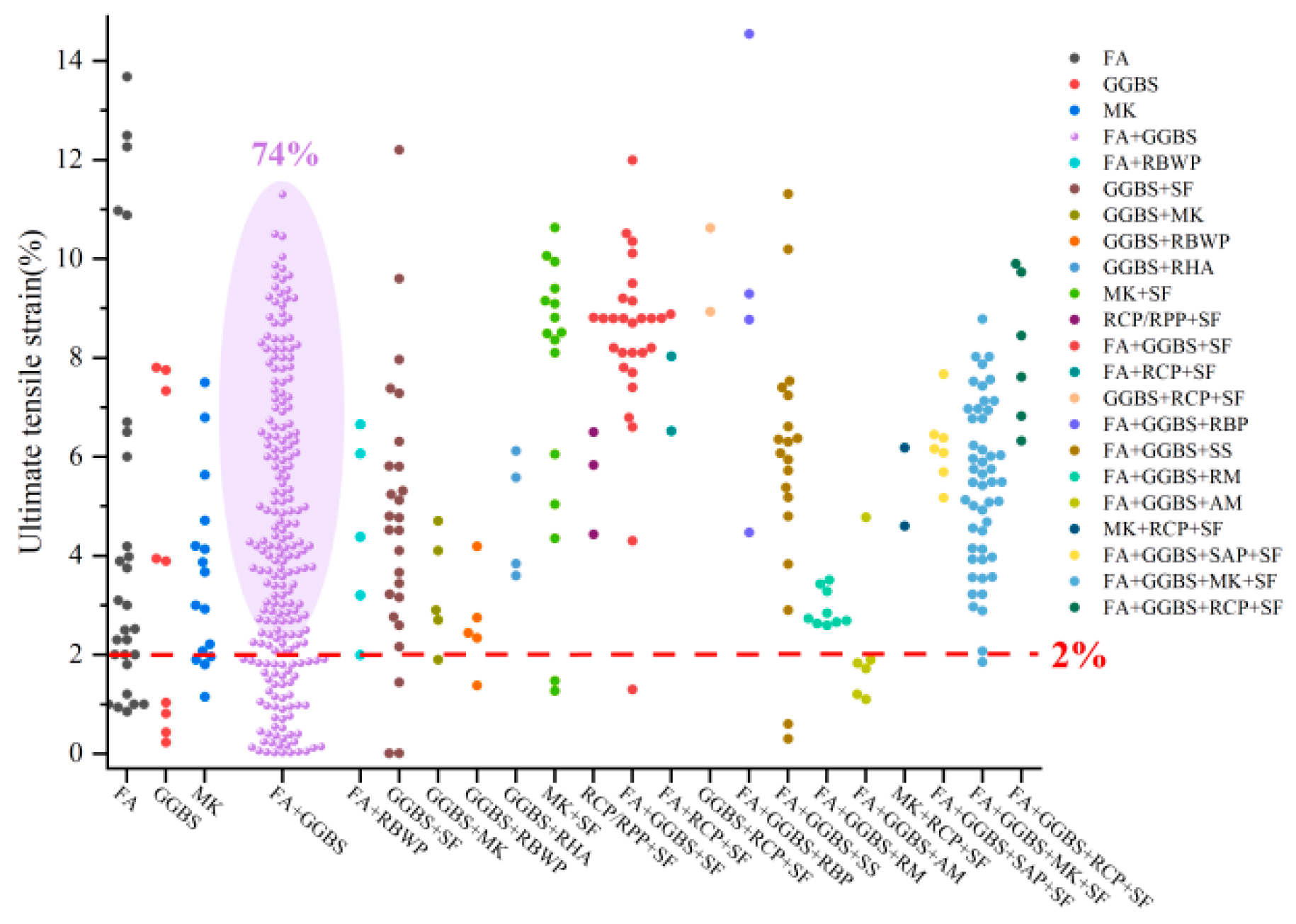

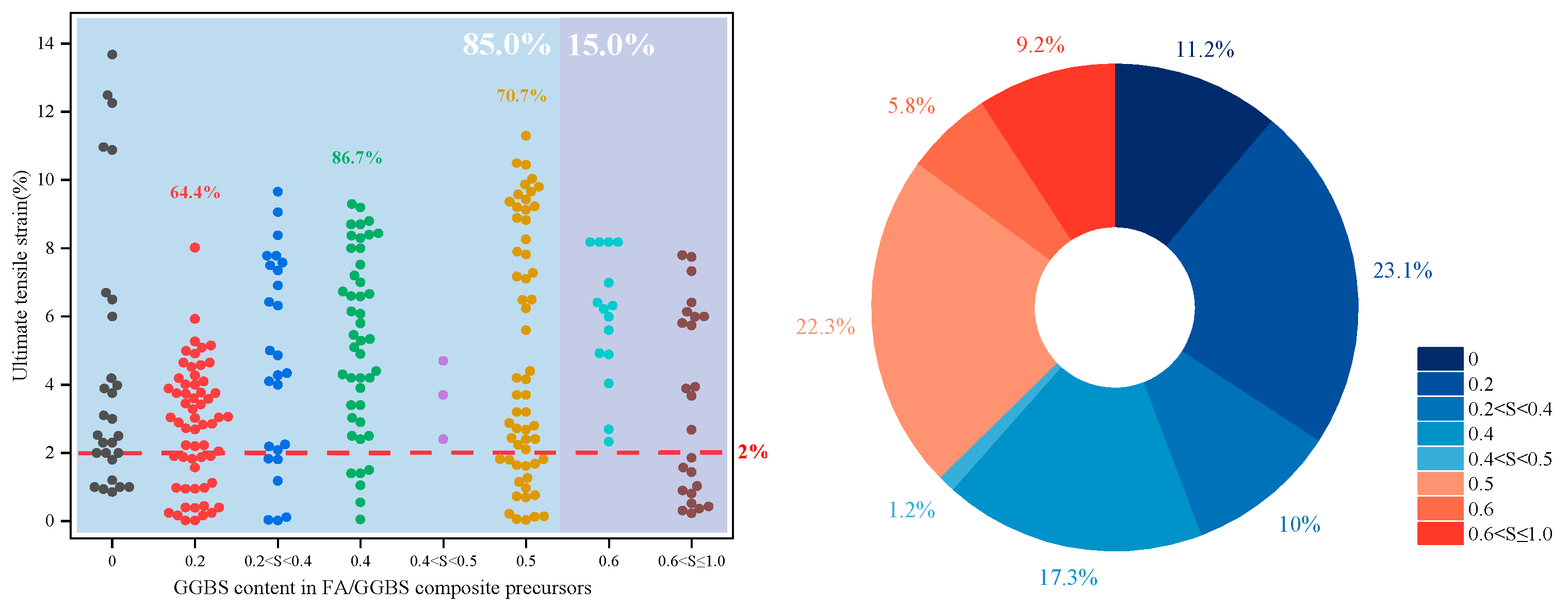

2.1. Precursor

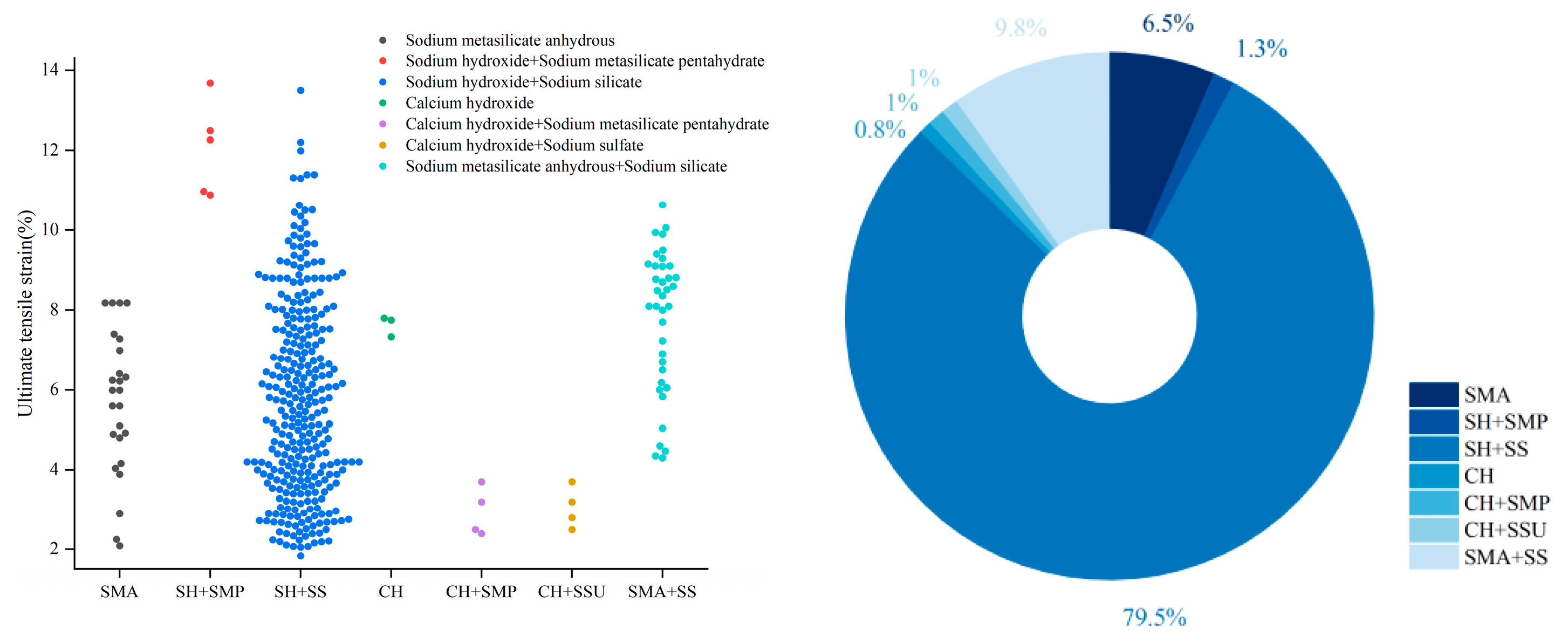

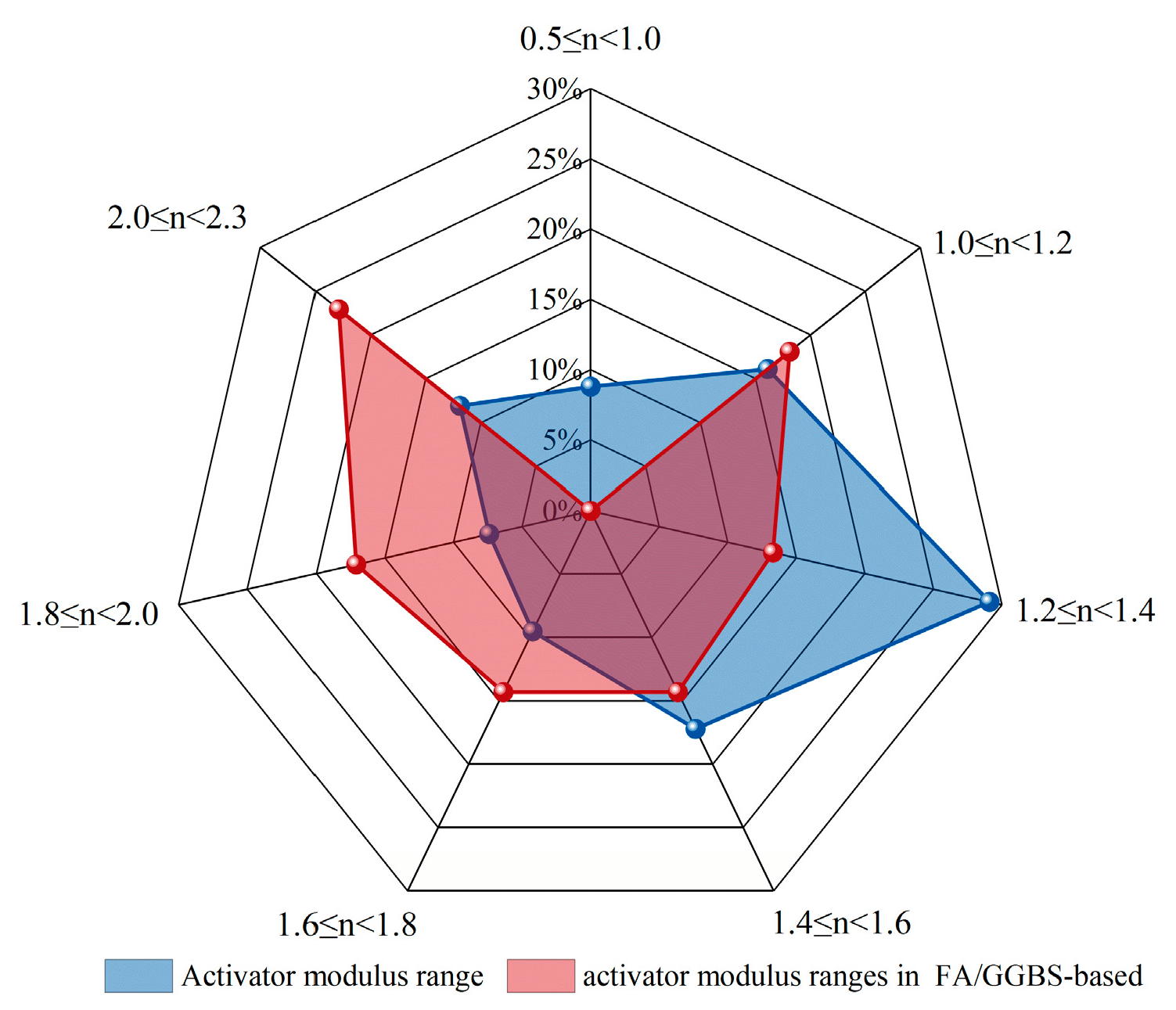

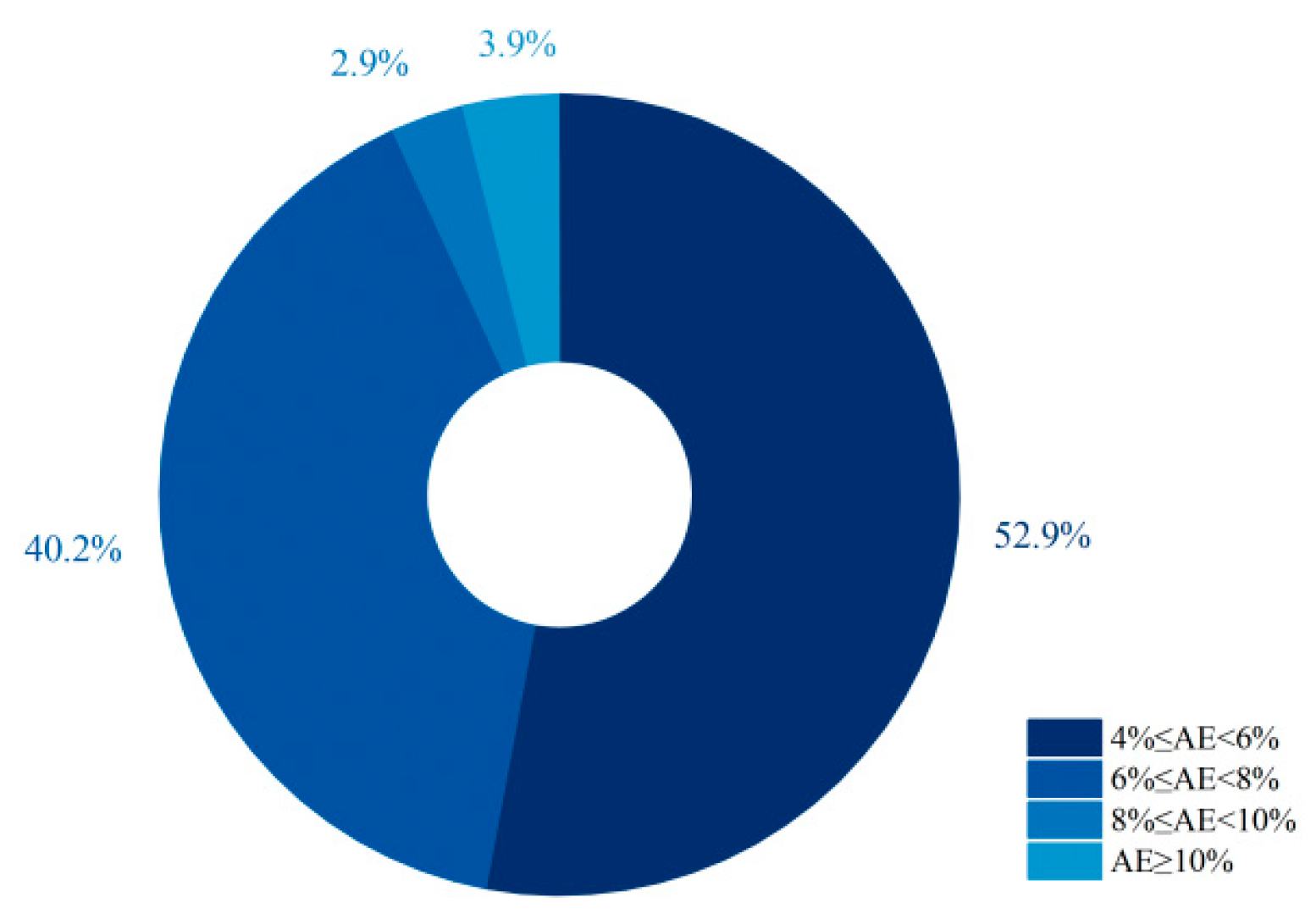

2.2. Alkali Activators

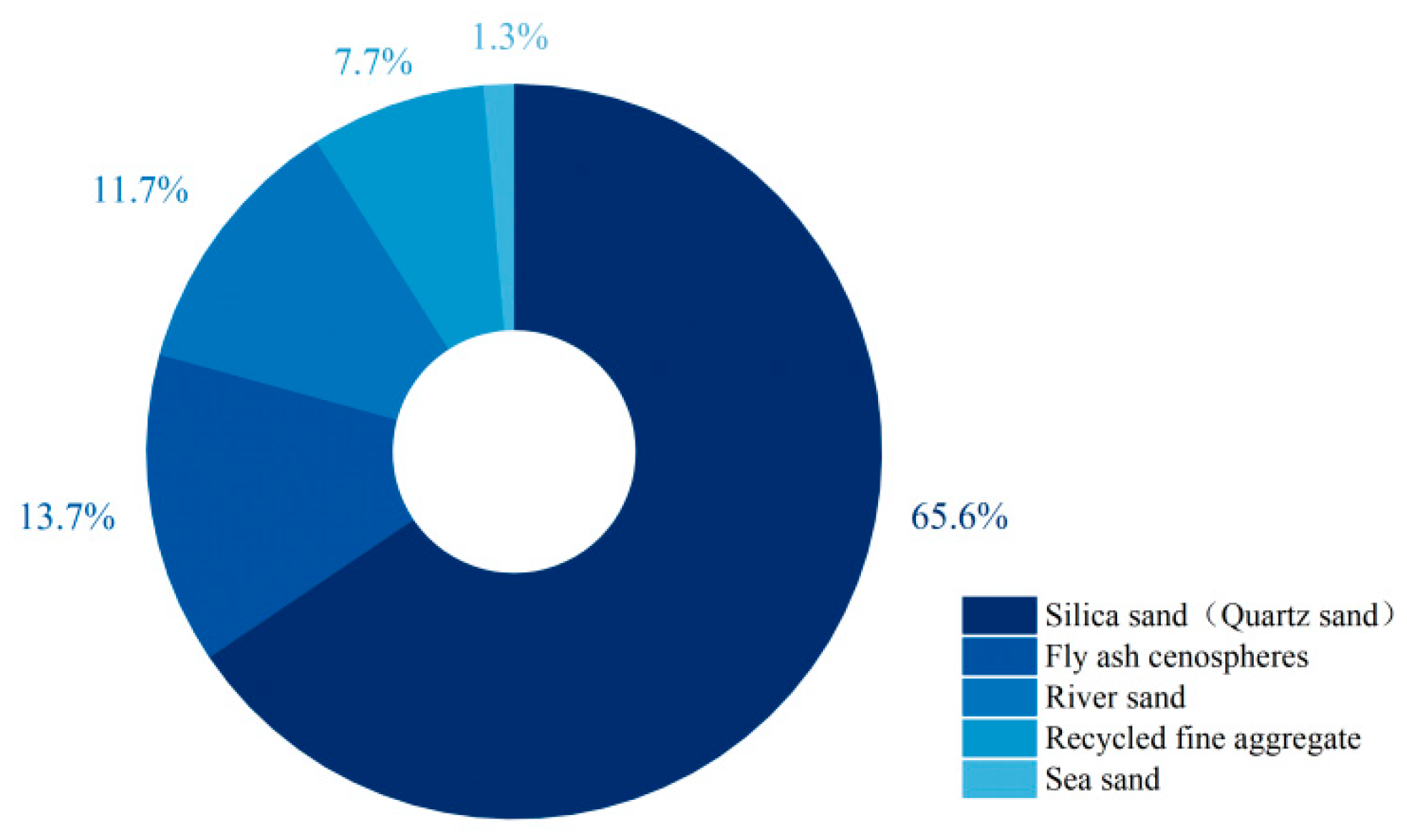

2.3. Sand

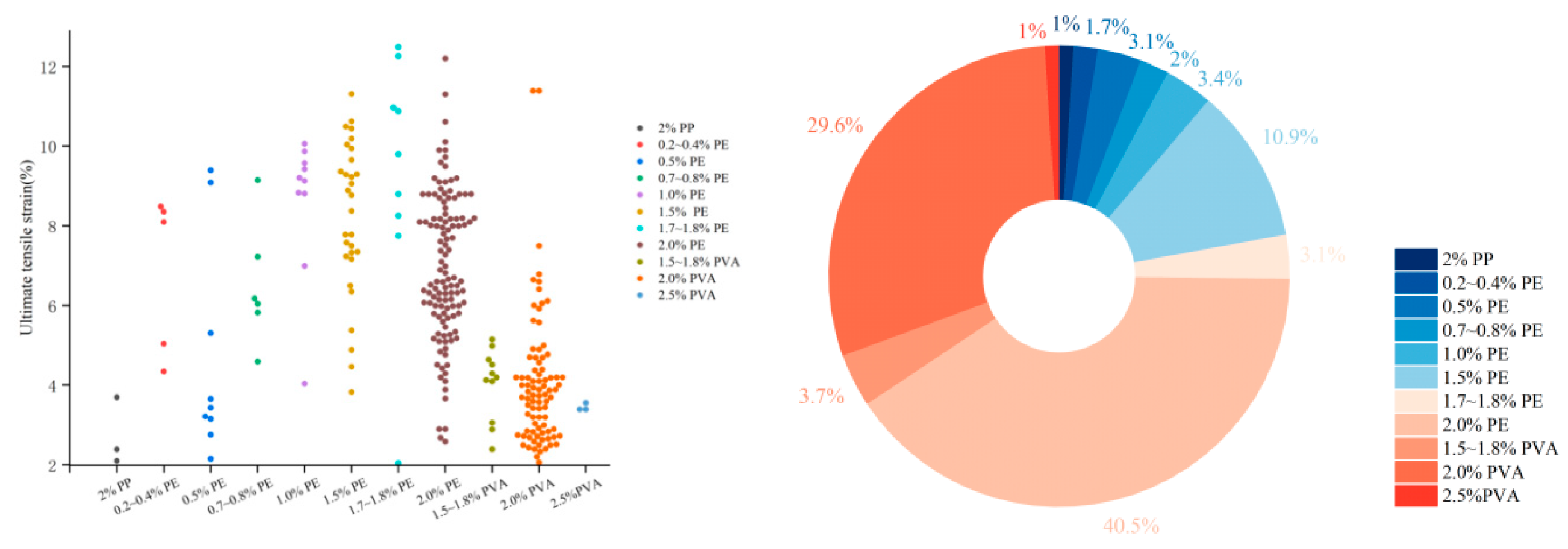

2.4. Fibers

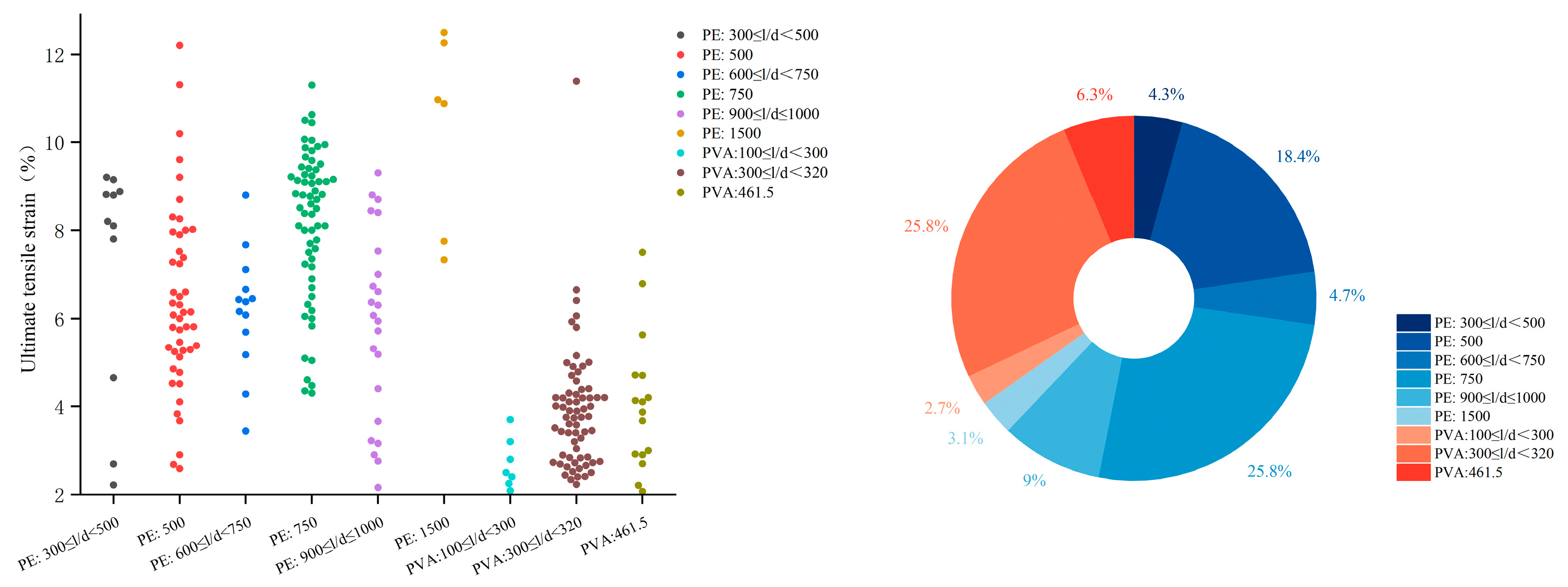

2.4.1. Type and Content of Fiber

2.4.2. Fiber Geometry

3. Curing Regime

4. Mechanical Properties of EGC

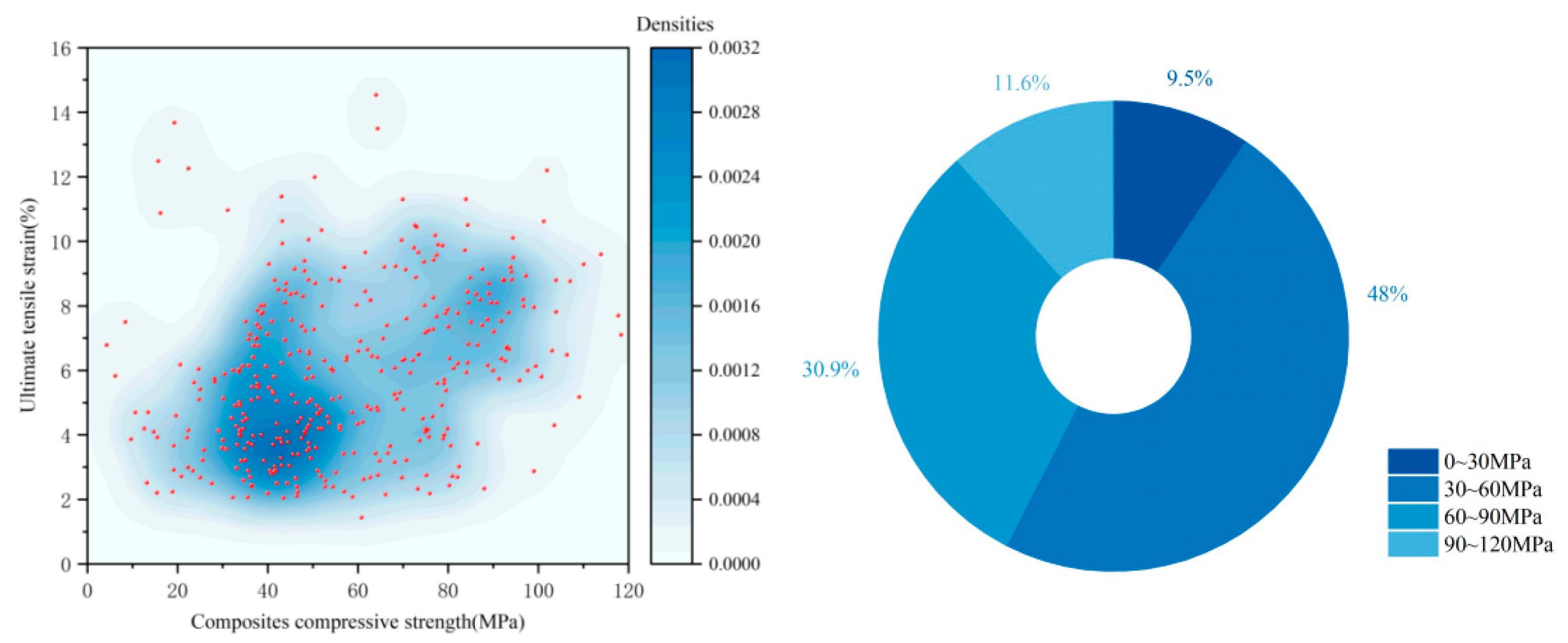

4.1. Relationship Between Compressive Strength and Ultimate Tensile Strain of EGC

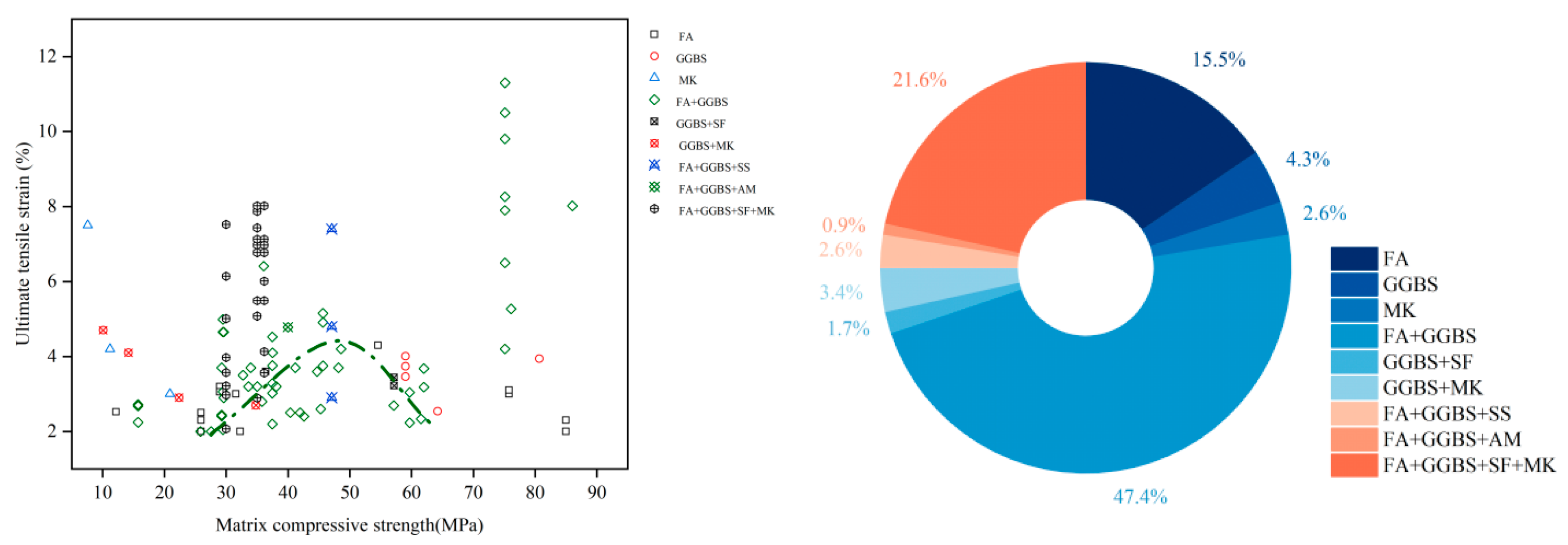

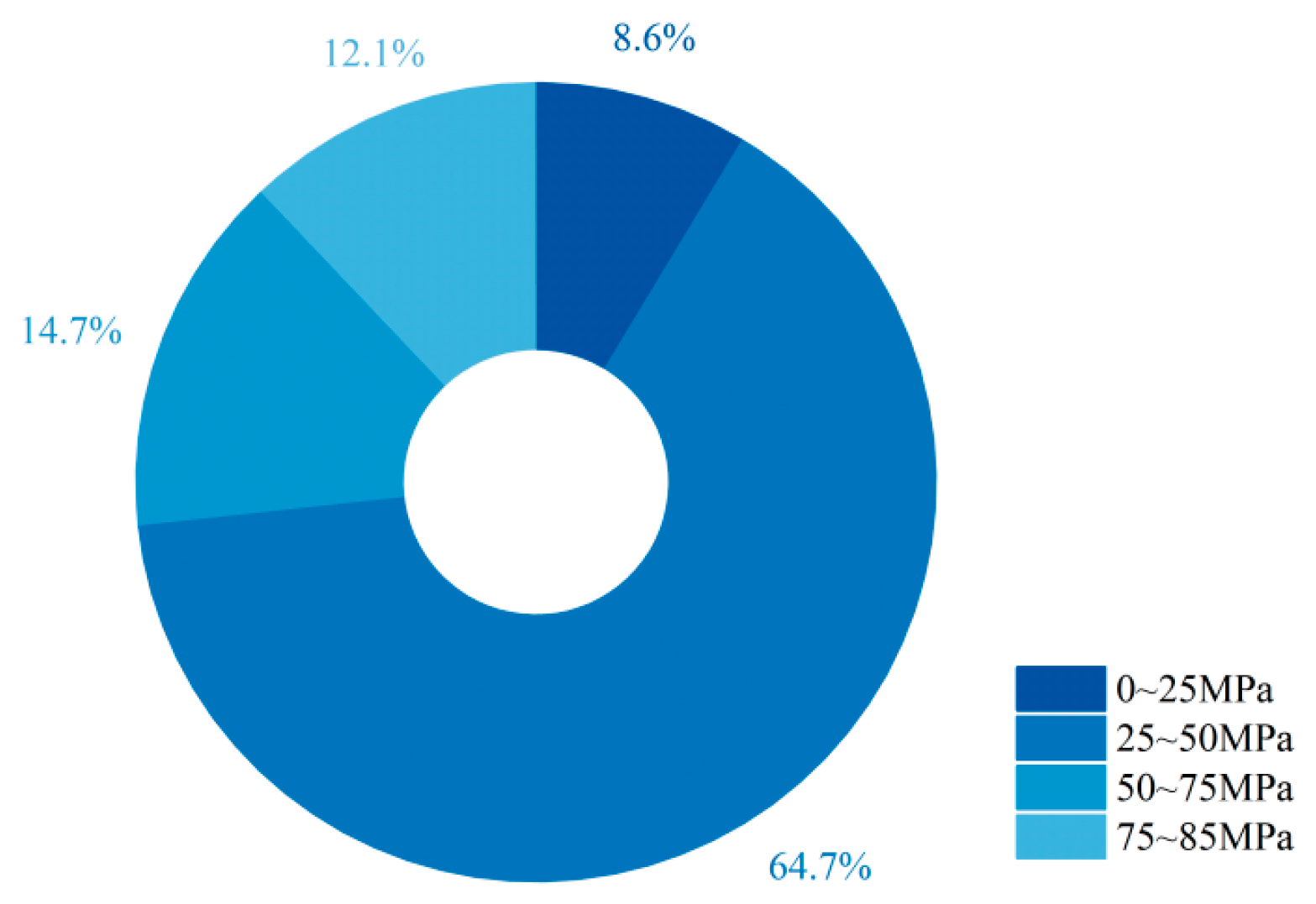

4.2. Relationship Between Matrix Compressive Strength and Ultimate Tensile Strain of EGC

5. Conclusions

- (1)

- Strain-hardening behavior in EGC is achieved by tuning precursor type, activator composition, fiber characteristics, and interfacial properties. Generally, a low-toughness matrix, fibers with moderate modulus and strength, and weak interfacial bonding are conducive to achieving strain-hardening and multiple cracking.

- (2)

- The most widely used precursor system is the fly ash–slag blend, activated by a combination of sodium hydroxide and sodium silicate. Effective systems typically use activators with a modulus of 1.4–1.8 and alkali equivalent of 4–8%. Common fibers include PE (2.0%, aspect ratio 500–750) and PVA (1.8–2.0%, aspect ratio ≈ 300). Fine aggregates are primarily silica sand with particle sizes of 100–250 μm. Curing strategies now favor normal temperature or segmented curing, depending on precursor type.

- (3)

- The compressive strength of EGC ranges from 20–120 MPa, satisfying structural requirements. Most high-performance EGCs achieving ultimate tensile strains ≥ 2% have matrix strengths between 25–50 MPa. For FA-GGBS and fly ash-only systems, tensile performance tends to improve with increasing matrix strength, peaking at an optimal range before declining.

- (1)

- Green Design: Promote research on precursors and powder activators based on solid waste resources, explore the synergistic mechanisms among various solid wastes, and develop a low-carbon, sprayable, and pumpable engineering-applicable EGC mix system.

- (2)

- Engineering Applications: Conduct service performance evaluations under the coupling of multiple environmental factors and verify applications at the structural component level, achieving the transition of EGC from materials research to engineering practice.

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| EGC | Engineered geopolymer composites |

| ECC | Engineered cementitious composites |

| FA | Fly ash |

| GGBS | Ground granulated blast furnace slag |

| RBWP | Recycled brick waste powder |

| SF | Silica fume |

| MK | Metakaolin |

| RHA | Rice husk ash |

| RCP | Recycled concrete powder |

| RPP | Recycled paste powder |

| RBP | Recycled brick powder |

| SSL | Steel slag |

| RM | Red mud |

| AM | Alkaline mud |

| SAP | Superabsorbent polymers |

| SSI | Sodium silicate |

| SH | Sodium hydroxide |

| SMA | Sodium metasilicate anhydrous |

| SMP | Sodium metasilicate pentahydrate |

| CH | Calcium hydroxide |

| SSU | Sodium sulfate |

References

- Li, V.C.; Maalej, M. Toughening in cement based composites. Part II: Fiber reinforced cementitious composites. Cem. Concr. Compos. 1996, 18, 239–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khalel, H.; Khan, M.; Starr, A.; Khan, K.A.; Muhammad, A. Performance of engineered fibre reinforced concrete (EFRC) under different load regimes: A review. Constr. Build. Mater. 2021, 306, 124692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hannant, D.J. Fibre-reinforced concrete. In Advanced Concrete Technology; Elsevier Ltd.: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2003; Volume 4, p. 6. [Google Scholar]

- Zollo, R.F. Fiber-reinforced concrete: An overview after 30 years of development. Cem. Concr. Compos. 1997, 19, 107–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, V.C. On engineered cementitious composites (ECC) a review of the material and its applications. J. Adv. Concr. Technol. 2003, 1, 215–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fischer, G.; Li, V.C. Influence of matrix ductility on tension-stiffening behavior of steel reinforced engineered cementitious composites (ECC). Struct. J. 2002, 99, 104–111. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, S.; Li, V.C. Polyvinyl alcohol fiber reinforced engineered cementitious composites: Material design and performances. In Proceedings of the International RILEM Workshop on HPFRCC in Structural Applications, Honolulu, HI, USA, 23–26 May 2005; pp. 65–73. [Google Scholar]

- Li, V.C. Engineered Cementitious Composites (ECC): Bendable Concrete for Sustainable and Resilient Infrastructure; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Zhu, J.X.; Xu, L.Y.; Huang, B.T.; Weng, K.F.; Dai, J.G. Recent developments in Engineered/Strain-Hardening Cementitious Composites (ECC/SHCC) with high and ultra-high strength. Constr. Build. Mater. 2022, 342, 127956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Y.Y.; Fischer, G.; Li, V.C. Performance of bridge deck link slabs designed with ductile engineered cementitious composite. Struct. J. 2004, 101, 792–801. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, T.; Tang, Y.; Qin, S.; Li, G.; Wu, H.; Leung, C.K. Sustainable and mechanical properties of Engineered Cementitious Composites with biochar: Integrating micro- and macro-mechanical insight. Cem. Concr. Compos. 2025, 155, 105813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wan, F.; Guo, Y.; Ge, K.; Zhuang, S.; Elghazouli, A.Y. Mechanical properties of sustainable engineered geopolymer composites with sodium carbonate activators. J. Build. Eng. 2025, 105, 112486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, L.Y.; Lao, J.C.; Shi, D.D.; Cai, J.; Xie, T.Y.; Huang, B.T. Recent advances in High-Strength Engineered Geopolymer Composites (HS-EGC): Bridging sustainable construction and resilient infrastructure. Cem. Concr. Compos. 2025, 165, 106307. [Google Scholar]

- Zhong, H.; Zhang, M. Engineered geopolymer composites: A state-of-the-art review. Cem. Concr. Compos. 2023, 135, 104850. [Google Scholar]

- Davidovits, J. Geopolymers: Inorganic polymeric new materials. J. Therm. Anal. Calorim. 1991, 37, 1633–1656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Deventer, J.S.J.; Provis, J.L. Geopolymers-Structure, Processing, Properties and Industrial Applications; Woodhead Publishing: Cambridge, UK, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, H.; Van Deventer, J.S.J. The geopolymerisation of alumino-silicate minerals. Int. J. Miner. Process. 2000, 59, 247–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehta, A.; Siddique, R. An overview of geopolymers derived from industrial by-products. Constr. Build. Mater. 2016, 127, 183–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davidovits, J. Geopolymer Chemistry and Applications; Geopolymer Institute: Saint-Quentin, France, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, J.; Li, M.; Zhao, D.; Zhong, G.; Sun, Y.; Hu, X.; Sun, J.; Li, X.; Zhu, W.; Li, M.; et al. Research and application progress of geopolymers in adsorption: A review. Nanomaterials 2022, 12, 3002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chi, M.; Huang, R. Binding mechanism and properties of alkali-activated fly ash/slag mortars. Constr. Build. Mater. 2013, 40, 291–298. [Google Scholar]

- Li, N.; Farzadnia, N.; Shi, C. Microstructural changes in alkali-activated slag mortars induced by accelerated carbonation. Cem. Concr. Res. 2017, 100, 214–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Yao, X.; Zhu, H. Potential application of geopolymers as protection coatings for marine concrete: II. Microstructure and anticorrosion mechanism. Appl. Clay Sci. 2010, 49, 7–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaikh, F.U.A. Deflection hardening behaviour of short fibre reinforced fly ash based geopolymer composites. Mater. Des. 2013, 50, 674–682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elmesalami, N.; Celik, K. A critical review of engineered geopolymer composite: A low-carbon ultra-high-performance concrete. Constr. Build. Mater. 2022, 346, 128491. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, E.H.; Yang, Y.; Li, V.C. Use of high volumes of fly ash to improve ECC mechanical properties and material greenness. ACI Mater. J. 2007, 104, 620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nematollahi, B.; Sanjayan, J. Effect of different superplasticizers and activator combinations on workability and strength of fly ash based geopolymer. Mater. Des. 2014, 57, 667–672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hardjito, D.; Wallah, S.E.; Sumajouw, D.M.; Rangan, B.V. On the development of fly ash-based geopolymer concrete. Mater. J. 2004, 101, 467–472. [Google Scholar]

- Sakulich, A.R. Reinforced geopolymer composites for enhanced material greenness and durability. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2011, 1, 195–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Komnitsas, K.; Zaharaki, D. Geopolymerisation: A review and prospects for the minerals industry. Miner. Eng. 2007, 20, 1261–1277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, B.; Ishwarya, G.; Gupta, M.; Bhattacharyya, S.K. Geopolymer concrete: A review of some recent developments. Constr. Build. Mater. 2015, 85, 78–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Gamal, S.M.A.; Selim, F.A. Utilization of some industrial wastes for eco-friendly cement production. Sustain. Mater. Technol. 2017, 12, 9–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, J.; Jie, Y.; Zhang, J.; Yu, Y.; Zhang, G. Synthesis and characterization of red mud and rice husk ash-based geopolymer composites. Cem. Concr. Compos. 2013, 37, 108–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reddy, K.N.; Narayana, K.S.; Reddy, J.D.; Chandra, B.S.; Kumar, Y.H. Effect of sodium hydroxide and sodium silicate solution on compressive strength of metakaolin and GGBS geopolymer. Int. J. Civ. Eng. Technol. 2017, 8, 1905–1917. [Google Scholar]

- Jegan, M.; Annadurai, R.; Rajkumar, P.R.K. A state of the art on effect of alkali activator, precursor, and fibers on properties of geopolymer composites. Case Stud. Constr. Mater. 2023, 18, e01891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phoo-ngernkham, T.; Maegawa, A.; Mishima, N.; Hatanaka, S.; Chindaprasirt, P. Effects of sodium hydroxide and sodium silicate solutions on compressive and shear bond strengths of FA–GBFS geopolymer. Constr. Build. Mater. 2015, 91, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y.; Cai, J.; Xu, L.; Ma, X.; Pan, J. Mechanical and environmental performance of engineered geopolymer composites incorporating ternary solid waste. J. Clean. Prod. 2024, 441, 141065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abd Elmoaty, A.E.M.; Morsy, A.M.; Harraz, A.B. Effect of fiber type and volume fraction on fiber reinforced concrete and engineered cementitious composite mechanical properties. Buildings 2022, 12, 2108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Sheikh, M.N.; Feng, H.; Hadi, M.N. Mechanical properties of ambient cured fly ash-slag-based engineered geopolymer composites with different types of fibers. Struct. Concr. 2023, 24, 2363–2383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- AbuFarsakh, R.; Arce, G.; Hassan, M.; Huang, O.; Radovic, M.; Rupnow, T.; Mohammad, L.N.; Sukhishvili, S. Effect of sand type and PVA fiber content on the properties of metakaolin based engineered geopolymer composites. Transp. Res. Rec. 2021, 2675, 475–491. [Google Scholar]

- AbuFarsakh, R.; Amador, G.A.; Noorvand, H.; Subedi, S.; Hassan, M. Influence of Sand and Fiber Type on the Fiber-Bridging Properties of Metakaolin-Based Engineered Geopolymer Composites. Transp. Res. Rec. 2024, 2678, 1639–1658. [Google Scholar]

- Asrani, N.P.; Murali, G.; Abdelgader, H.S.; Parthiban, K.; Haridharan, M.K.; Karthikeyan, K. Investigation on mode I fracture behavior of hybrid fiber-reinforced geopolymer composites. Arab. J. Sci. Eng. 2019, 44, 8545–8555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, T.; Fan, X.; Gao, C.; Qu, C.; Liu, J.; Yu, G. The influence of fiber on the mechanical properties of geopolymer concrete: A review. Polymers 2023, 15, 827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farhan, K.Z.; Johari, M.A.M.; Demirboğa, R. Impact of fiber reinforcements on properties of geopolymer composites: A review. J. Build. Eng. 2021, 44, 102628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.; Lu, B.; Bai, T.; Wang, H.; Du, F.; Zhang, Y.; Jiang, C.; Wang, W. Geopolymer, green alkali activated cementitious material: Synthesis, applications and challenges. Constr. Build. Mater. 2019, 224, 930–949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amran, M.; Debbarma, S.; Ozbakkaloglu, T. Fly ash-based eco-friendly geopolymer concrete: A critical review of the long-term durability properties. Constr. Build. Mater. 2021, 270, 121857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Artyk, Z.; Kuan, Y.; Zhang, D.; Shon, C.S.; Ogwumeh, C.M.; Kim, J. Development of engineered geopolymer composites containing low-activity fly ashes and ground granulated blast furnace slags with hybrid fibers. Constr. Build. Mater. 2024, 422, 135760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Subramanian, S.; Eswar, T.D.; Joseph, V.A.; Mathew, S.B.; Davis, R. Fly ash and BOF slag as sustainable precursors for engineered geopolymer composite (EGC) mixes: A strength optimization study. Arab. J. Sci. Eng. 2024, 49, 5697–5719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, S.; Cai, Y.; Guo, Y.; Lin, J.; Liu, G.; Lan, X.; Song, Y. Experimental study on axial compressive performance of polyvinyl alcohol fibers reinforced fly ash—Slag geopolymer composites. Polymers 2021, 14, 142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kan, L.L.; Wang, W.S.; Liu, W.D.; Wu, M. Development and characterization of fly ash based PVA fiber reinforced Engineered Geopolymer Composites incorporating metakaolin. Cem. Concr. Compos. 2020, 108, 103521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nematollahi, B.; Sanjayan, J.; Ahmed Shaikh, F.U. Tensile strain hardening behavior of PVA fiber-reinforced engineered geopolymer composite. J. Mater. Civ. Eng. 2015, 27, 04015001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, X.; Yin, J.; Xu, X.; Zhang, D.; Wang, Y. Rheological, mechanical, and microstructural properties of Engineered Geopolymer Composite (EGC) made with ground granulated blast furnace slag (GGBFS) and fly ash. J. Mater. Res. Technol. 2025, 35, 1996–2010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, H.; Wen, J.; Shao, Q.; Yang, Y.; Yao, X. Carbonation resistance of fly ash/slag based engineering geopolymer composites. Constr. Build. Mater. 2024, 449, 138471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyu, B.C.; Guo, L.P.; Fei, X.P.; Wu, J.D.; Bian, R.S. Preparation and properties of green high ductility geopolymer composites incorporating recycled fine brick aggregate. Cem. Concr. Compos. 2023, 139, 105054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y. Study on Effect and Mechanism of Fiber Interfacial Modification on the Properties of Engineering Geopolymer Composites. Master’s Thesis, Qingdao University of Technology, Qingdao, China, 2024. (In Chinese). [Google Scholar]

- Teo, W.; Shirai, K.; Lim, J.H. Characterisation of “one-part” ambient cured engineered geopolymer composites. J. Adv. Concr. Technol. 2023, 21, 204–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, F.; Yang, Z.; Chen, D.; Lu, Y.; Li, S. Research on mechanical properties and micro-mechanism of Engineering Geopolymers Composites (EGCs) incorporated with modified MWCNTs. Constr. Build. Mater. 2021, 303, 124516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, F.; Zhou, Z.; Lu, Y.; Li, S. Effect of PVA fibers grafted with MWCNTs on the shrinkage behaviors of engineered geopolymer composite (EGC). Constr. Build. Mater. 2024, 449, 138508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyễn, H.H.; Nguyễn, P.H.; Lương, Q.H.; Meng, W.; Lee, B.Y. Mechanical and autogenous healing properties of high-strength and ultra-ductility engineered geopolymer composites reinforced by PE-PVA hybrid fibers. Cem. Concr. Compos. 2023, 142, 105155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, J.Q.; Li, B.; Chen, Y.T.; Ghiassi, B. Investigation on the roles of glass sand in sustainable engineered geopolymer composites. Constr. Build. Mater. 2023, 363, 129576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyễn, H.H.; Lương, Q.H.; Nguyễn, P.H.; Kim, H.K.; Kim, Y.; Lee, B.Y. Micromechanical and mineralogy analyses on extremely ductile engineered geopolymer composites with different activator pretreatments. J. Build. Eng. 2023, 80, 108093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, F.; Zhao, J.; Zhang, B.; Feng, Y.; Chen, C.; Lu, Z.; Yang, J.; Xie, J. Physical, mechanical and microstructural properties of ultra-lightweight high-strength geopolymeric composites. Case Stud. Constr. Mater. 2023, 19, e02446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hossain, K.M.A.; Sood, D. The strength and fracture characteristics of one-part strain-hardening green alkali-activated engineered composites. Materials 2023, 16, 5077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kan, L.; Gan, Y.; Lv, L.; Dai, L.; Dai, W.; Lin, Y.; Li, J.; Zhang, Z. Thermal impacts on eco-friendly ultra-lightweight high ductility geopolymer composites doped with low fiber volume. Constr. Build. Mater. 2025, 458, 139607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, F.; Zhai, J.; Kan, E.; Norkulov, B.; Ding, Y.; Yu, J.; Yu, K. Value-added recycling of waste brick powder and waste sand to develop eco-friendly engineered geopolymer composite. Case Stud. Constr. Mater. 2024, 21, e03590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, F.; Yang, Z.; Zheng, A.; Li, S. Properties of modified engineered geopolymer composites incorporating multi-walled carbon Nanotubes (MWCNTs) and granulated blast furnace Slag (GBFS). Ceram. Int. 2021, 47, 14244–14259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, Z.; Lu, Y.; An, J.; Zhang, H.; Li, S. Multi-scale reinforcement of multi-walled carbon nanotubes/polyvinyl alcohol fibers on lightweight engineered geopolymer composites. J. Build. Eng. 2022, 57, 104889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Zhong, H.; Zhang, M. Experimental study on static and dynamic properties of fly ash-slag based strain hardening geopolymer composites. Cem. Concr. Compos. 2022, 129, 104481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, Z.; An, J.; Li, F.; Lu, Y.; Li, S. Effect of fly ash cenospheres on properties of multi-walled carbon nanotubes and polyvinyl alcohol fibers reinforced geopolymer composites. Ceram. Int. 2022, 48, 18956–18971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lao, J.C.; Ma, R.Y.; Xu, L.Y.; Li, Y.; Shen, Y.N.; Yao, J.; Wang, Y.; Xie, T.; Huang, B.T. Fly ash-dominated high-strength engineered/strain-hardening geopolymer composites (HS-EGC/SHGC): Influence of alkalinity and environmental assessment. J. Clean. Prod. 2024, 447, 141182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, Z.; Pang, Z.; Lu, C.; Yao, Y. Feasibility study of engineered geopolymer composites based high-calcium fly ash and micromechanics analysis. Case Stud. Constr. Mater. 2024, 20, e02701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lao, J.C.; Huang, B.T.; Xu, L.Y.; Khan, M.; Fang, Y.; Dai, J.G. Seawater sea-sand Engineered Geopolymer Composites (EGC) with high strength and high ductility. Cem. Concr. Compos. 2023, 138, 104998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, J.X.; Liu, R.A.; Liu, L.Y.; Zhuo, K.Y.; Chen, Z.B.; Guo, Y.C. High-strength and high-toughness alkali-activated composite materials: Optimizing mechanical properties through synergistic utilization of steel slag, ground granulated blast furnace slag, and fly ash. Constr. Build. Mater. 2024, 422, 135811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramesh, V.A.; Nikbakht Jarghouyeh, E.; Alraeeini, A.S.; Al-Fakih, A. Optimisation Investigation and Bond-Slip Behaviour of Bigh Btrength PVA-Engineered Geopolymer Composite (EGC) Cured in Ambient Temperatures. Buildings 2023, 13, 3020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, F.; Ma, J.; Ding, Y.; Yu, J.; Yu, K. Engineered Geopolymer Composite (EGC) with Ultra-Low Fiber Content of 0.2%. Constr. Build. Mater. 2024, 411, 134626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, J.; Cai, J.; Lin, Y.; Sun, Y.; Pan, J. Impact resistance of engineered geopolymer composite (EGC) in cold temperatures. Constr. Build. Mater. 2022, 343, 128150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, X.; Zhu, J.; Gao, X. Sea/coral sand in marine engineered geopolymer composites: Engineering, mechanical, and microstructure properties. Int. J. Appl. Ceram. Technol. 2025, 22, e14874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, J.Q.; Lu, Z.; Chen, Y.T.; Ghiassi, B.; Shi, W.; Li, B. Mechanical properties and cracking behaviour of lightweight engineered geopolymer composites with fly ash cenospheres. Constr. Build. Mater. 2023, 400, 132622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, L.Y.; Lao, J.C.; Qian, L.P.; Khan, M.; Xie, T.Y.; Huang, B.T. Low-carbon high-strength engineered geopolymer composites (HS-EGC) with full-volume fly ash precursor: Role of silica modulus. J. CO2 Util. 2024, 88, 102948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, S.; Das, C.S.; Lao, J.; Alrefaei, Y.; Dai, J.G. Effect of sand content on bond performance of engineered geopolymer composites (EGC) repair material. Constr. Build. Mater. 2022, 328, 127080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Liu, W.; Liu, M. Setting time and mechanical properties of chemical admixtures modified FA/GGBS-based engineered geopolymer composites. Constr. Build. Mater. 2024, 431, 136473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, J.; Pan, J.; Han, J.; Lin, Y.; Sheng, Z. Low-energy impact behavior of ambient cured engineered geopolymer composites. Ceram. Int. 2022, 48, 9378–9389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, J.; Pan, J.; Han, J.; Wang, X. Mechanical behaviors of metakaolin-based engineered geopolymer composite under ambient curing condition. J. Mater. Civ. Eng. 2022, 34, 04022152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Ling, Y.; Wu, Y.; Lai, H.; Wang, Y.; Chen, Z. Comprehensive analysis of mechanical, economic, and environmental characteristics of hybrid PE/PP fiber-reinforced engineered geopolymer composites. Buildings 2024, 14, 1094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Zhang, Z.; Liu, X.; Zhang, Y.; Ma, Z. Elucidating the role of recycled concrete aggregate in ductile engineered geopolymer composites: Effects of recycled concrete aggregate content and size. J. Build. Eng. 2024, 95, 110150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, Y.Q.; Zheng, D.P.; Pan, H.S.; Yang, J.L.; Lin, J.X.; Lai, H.M.; Wu, P.Z.; Zhu, H.Y. Strain hardening geopolymer composites with hybrid POM and UHMWPE fibers: Analysis of static mechanical properties, economic benefits, and environmental impact. J. Build. Eng. 2023, 76, 107315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Humur, G.; Cevik, A. Effects of hybrid fibers and nanosilica on mechanical and durability properties of lightweight engineered geopolymer composites subjected to cyclic loading and heating–cooling cycles. Constr. Build. Mater. 2022, 326, 126846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Cao, W.; Zhang, M.; Yao, Y. A multi-scale experimental study of hybrid fiber reinforced ternary geopolymer with multiple solid wastes. J. Mater. Res. Technol. 2024, 30, 7187–7202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, J.K.; Atmaca, N.; Khoshnaw, G.J. Building a sustainable future: An experimental study on recycled brick waste powder in engineered geopolymer composites. Case Stud. Constr. Mater. 2024, 20, e02863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, X.; Wang, Q.; Zhao, P.; Wu, C.; Zhu, D. Mechanical properties and enhancement mechanism of lithium slag-contained geopolymers reinforced with PVA fibers and functionalized multi-walled carbon nanotubes. J. Build. Eng. 2024, 97, 110977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, J.; Li, Z.; Liu, X.; Yang, X.; Lv, J. Mechanical Properties and Stress–Strain Relationship of PVA-Fiber-Reinforced Engineered Geopolymer Composite. Polymers 2024, 16, 1685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, J.Q.; Li, B.; Chen, Y.T.; Ghiassi, B.; Elamin, A. Effects of polyethylene fiber dosage and length on the properties of high-tensile-strength engineered geopolymer composite. J. Mater. Civ. Eng. 2023, 35, 04023224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, S.U.; Ayub, T. PET fiber–reinforced engineered geopolymer and cementitious composites. J. Mater. Civ. Eng. 2022, 34, 06021010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kan, L.; Gan, Y.Q.; Dai, W.; Lv, L.H.; Dai, L.Q.; Zhai, J.B.; Wang, F. Curing-dependent behaviors of sustainable alkali-activated fiber reinforced composite: Temperature and humidity effects. J. Build. Eng. 2024, 96, 110392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyễn, H.H.; Lương, Q.H.; Choi, J.I.; Ranade, R.; Li, V.C.; Lee, B.Y. Ultra-ductile behavior of fly ash-based engineered geopolymer composites with a tensile strain capacity up to 13.7%. Cem. Concr. Compos. 2021, 122, 104133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, Y.; Guo, W.; Jiang, B.; Song, N.; Su, Y.; Zhang, J.; Yu, J.; Li, B. Understanding the role of superabsorbent polymers in engineered geopolymer composites. Constr. Build. Mater. 2025, 458, 139770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yaswanth, K.K.; Revathy, J.; Gajalakshmi, P. Influence of copper slag on Mechanical, durability and microstructural properties of GGBS and RHA blended strain hardening geopolymer composites. Constr. Build. Mater. 2022, 342, 128042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, B.; Liu, C.; Shumuye, E.D.; Zhang, Y.; Zhong, H.; Fang, G. Effect of nano-silica on mechanical properties and microstructure of engineered geopolymer composites. Cem. Concr. Compos. 2025, 156, 105849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lao, J.C.; Huang, B.T.; Fang, Y.; Xu, L.Y.; Dai, J.G.; Shah, S.P. Strain-hardening alkali-activated fly ash/slag composites with ultra-high compressive strength and ultra-high tensile ductility. Cem. Concr. Res. 2023, 165, 107075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, L.P.; Lyu, B.C.; He, J.O.; Lu, J.T.; Chen, B. Mechanical and thermoelectric properties of high ductility geopolymer composites with nano zinc oxide and red mud. Constr. Build. Mater. 2024, 455, 139173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, F.; Zhai, J.; Ding, Y.; Nishiwaki, T.; Yu, J.; Li, V.C.; Yu, K. Design-driven approach for engineered geopolymer composite with recorded low fiber content. Compos. Part B Eng. 2024, 287, 111834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, J.I.; Nguyễn, H.H.; Park, S.E.; Ranade, R.; Lee, B.Y. Effects of fiber hybridization on mechanical properties and autogenous healing of alkali-activated slag-based composites. Constr. Build. Mater. 2021, 310, 125280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kan, L.; Chen, B.; Zhai, J.; Dai, L.; Wang, F.; Xu, M.; Bai, P. Long-term behaviors of fiber reinforced alkali-activated composite cured at ambient condition: Mechanical characterization. Case Stud. Constr. Mater. 2024, 20, e03306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhong, H.; Zhang, M. Effect of recycled tyre polymer fibre on engineering properties of sustainable strain hardening geopolymer composites. Cem. Concr. Compos. 2021, 122, 104167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, H.; Liu, X.; Wang, C.; Zhang, Y.; Ma, Z. Micro-properties and mechanical behavior of high-ductility engineered geopolymer composites (EGC) with recycled concrete and paste powder as green precursor. Cem. Concr. Compos. 2024, 152, 105672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, Y. Rheological and Mechanical Properties of Fiber Reinforced Alkali-Activated Cementitious Material Based on Utilization of Alkali Mud. Master’s Thesis, Qingdao University of Technology, Qingdao, China, 2022. (In Chinese). [Google Scholar]

- Shen, C. A Study on Mechanical Properties and Fracture Properties of Engineering Geopolymer Composites. Master’s Thesis, Qingdao University of Technology, Qingdao, China, 2019. (In Chinese). [Google Scholar]

- Liu, J. Study on Properties and Modification of Interface in Fiber Reinforced Geopolymer Composites. Master’s Thesis, Qingdao University of Technology, Qingdao, China, 2022. (In Chinese). [Google Scholar]

- Zhu, L.; Ju, Z.; Yang, Z.; Lin, T.; Liu, R.; Lin, J. Experimental Study on the Positive Bonding Performance at the Interface between Engineered Geopolymer-Based Composites and Ordinary Concrete. Highway 2025, 70, 416–423. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Sun, L.; Yu, L.; Liu, B. Study on the mechanical properties of lightweight engineered geopolymer composite prepared by recycled concrete powder. New Build. Mater. 2025, 52, 36–41. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- He, R.; Yang, Z.; Yan, T.; Wan, X.; Chen, X.; Zhuo, K.; Li, R.; Zhuo, K.; Guo, Y. Experimental study on mechanical properties of steel slag modified high ductility geopolymer composites. Concrete 2025, 94–98. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Zhu, H.; Lin, C.; Cai, S.; Xu, Y.; Pan, L. Influence of PVA Fiber Type on Mechanical Properties of Strain-Hardening Geopolymer Composites. Bull. Chin. Ceram. Soc. 2021, 40, 3693–3701. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kan, L.; Li, M.; Wang, F.; Zhao, Y.; Wang, Z. Influence of Activator Modulus on Tensile and Compressive Propertiesof High Ductile Alkali-activated Slag Composites. J. Mater. Sci. Eng. 2024, 42, 562–568+601. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kan, L.; Pang, C.; Wang, F.; Xue, J.; Zhao, S.; Liu, W.; Zhao, Y. Tensile and compressive properties and crack distribution ofpolyethylene fiber reinforced high ductile alkali-activated slag composites. Acta Mater. Compos. Sin. 2021, 38, 4305–4312. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nematollahi, B.; Sanjayan, J.; Shaikh, F.U.A. Matrix design of strain hardening fiber reinforced engineered geopolymer composite. Compos. Part B Eng. 2016, 89, 253–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nematollahi, B.; Sanjayan, J.; Qiu, J.; Yang, E.H. High ductile behavior of a polyethylene fiber-reinforced one-part geopolymer composite: A micromechanics-based investigation. Arch. Civ. Mech. Eng. 2017, 17, 555–563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nematollahi, B.; Qiu, J.; Yang, E.H.; Sanjayan, J. Microscale investigation of fiber-matrix interface properties of strain-hardening geopolymer composite. Ceram. Int. 2017, 43, 15616–15625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nematollahi, B.; Sanjayan, J.; Qiu, J.; Yang, E.H. Micromechanics-based investigation of a sustainable ambient temperature cured one-part strain hardening geopolymer composite. Constr. Build. Mater. 2017, 131, 552–563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farooq, M.; Bhutta, A.; Banthia, N. Tensile performance of eco-friendly ductile geopolymer composites (EDGC) incorporating different micro-fibers. Cem. Concr. Compos. 2019, 103, 183–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zahid, M.; Shafiq, N.; Razak, S.N.A.; Tufail, R.F. Investigating the effects of NaOH molarity and the geometry of PVA fibers on the post-cracking and the fracture behavior of engineered geopolymer composite. Constr. Build. Mater. 2020, 265, 120295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alrefaei, Y.; Dai, J.G. Tensile behavior and microstructure of hybrid fiber ambient cured one-part engineered geopolymer composites. Constr. Build. Mater. 2018, 184, 419–431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, X.; Xu, J.-Y.; Li, W.M. Erlei Bai Effect of alkali-activator types on the dynamic compressive deformation behavior of geopolymer concrete. Mater. Lett. 2014, 124, 310–312. [Google Scholar]

- Gökçe, H.S.; Tuyan, M.; Ramyar, K.; Nehdi, M.L. Development of eco-efficient fly ash–based alkali-activated and geopolymer composites with reduced alkaline activator dosage. J. Mater. Civ. Eng. 2020, 32, 04019350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Réunion internationale des laboratoires et experts des matériaux, systèmes de construction et ouvrages. In Alkali Activated Materials: State-of-the-Art Report, RILEM TC 224-AAM; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2014.

- Puertas, F.; Martínez-Ramírez, S.; Alonso, S.; Vázquez, T. Alkali-activated fly ash/slag cements: Strength behaviour and hydration products. Cem. Concr. Res. 2000, 30, 1625–1632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.; Sun, H.; Li, L. A review: The comparison between alkali-activated slag (Si+ Ca) and metakaolin (Si+ Al) cements. Cem. Concr. Res. 2010, 40, 1341–1349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, M. Effect of sand content on engineering properties of fly ash-slag based strain hardening geopolymer composites. J. Build. Eng. 2021, 34, 101951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xi, H.; Zhang, Z.L.; Zhuo, F.Y.; Hou, L.J.; Zhang, H.; Zhang, W.J.; Ji, X.H.; Liu, K.C.; Shen, Y.N.; Lao, J.C. High-strength high-ductility Engineered/Strain-Hardening Geopolymer Composites (EGC/SHGC) incorporating dredged river sand. Case Stud. Constr. Mater. 2025, 22, e04796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, L.Y.; Huang, B.T.; Lao, J.C.; Yao, J.; Li, V.C.; Dai, J.G. Tensile over-saturated cracking of ultra-high-strength engineered cementitious composites (UHS-ECC) with artificial geopolymer aggregates. Cem. Concr. Compos. 2023, 136, 104896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, M.; Song, S.; Feng, L.; Zhou, J.; Li, H.; Li, V.C. Development of basalt fiber engineered cementitious composites and its mechanical properties. Constr. Build. Mater. 2021, 266, 121173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Özkan, Ş.; Demir, F. The hybrid effects of PVA fiber and basalt fiber on mechanical performance of cost effective hybrid cementitious composites. Constr. Build. Mater. 2020, 263, 120564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pang, Z.; Lu, C.; Liu, J.; Yao, Y.; Wang, J. Experimental study of tensile properties of strain-hardening cementitious composites (SHCCs) reinforced with innovative twisted basalt fibers. Structures 2023, 48, 1977–1988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Premkumar, N.; Maheswaran, J.; Chellapandian, M. Characterization of Novel Natural Fiber-Reinforced Strain-Hardening Cementitious Composites. ACI Mater. J. 2024, 121, 75–90. [Google Scholar]

- Lv, C.; Liu, J.; Guo, G.; Zhang, Y. The mechanical properties of plant fiber-reinforced geopolymers: A review. Polymers 2022, 14, 4134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kishore, K.; Sheikh, M.N.; Hadi, M.N.S. Doped multi-walled carbon nanotubes and nanoclay based-geopolymer concrete: An overview of current knowledge and future research challenges. Cem. Concr. Compos. 2024, 154, 105774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sridhar, R.; Prasad, R. Study on mechanical properties of hybrid fiber reinforced engineered cementitious composites. Rev. Romana Mater. 2019, 49, 424–433. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Z.; Zhang, Q. Matrix tailoring of Engineered Cementitious Composites (ECC) with non-oil-coated, low tensile strength PVA fiber. Constr. Build. Mater. 2018, 161, 420–431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lan, M.; Zhou, J.; Xu, M. Effect of fibre types on the tensile behaviour of engineered cementitious composites. Front. Mater. 2021, 8, 775188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arain, M.F.; Wang, M.; Chen, J.; Zhang, H. Study on PVA fiber surface modification for strain-hardening cementitious composites (PVA-SHCC). Constr. Build. Mater. 2019, 197, 107–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Xu, J.; Song, Y.; Hou, M.; Xu, Y. Development of low-cost engineered cementitious composites using Yellow River silt and unoiled PVA fiber. Constr. Build. Mater. 2024, 425, 136063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, Z.; Wu, C.; Liu, J.; Wang, W.; Liu, J. Study on mechanical properties of cost-effective polyvinyl alcohol engineered cementitious composites (PVA-ECC). Constr. Build. Mater. 2015, 78, 397–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; Liu, J.; Duan, S.; Du, L.; Zhang, Z.; Zhang, M.; Jiang, D.; Wu, X. Investigation into the strength and toughness of polyvinyl alcohol fiber-reinforced fly ash-based geopolymer composites. J. Build. Eng. 2024, 90, 109371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Huang, X.; Guo, S.; Zhang, X.; Nie, Y. An experimental investigation on freeze-thaw resistance of fiber-reinforced red mud-slag based geopolymer. Case Stud. Constr. Mater. 2024, 20, e03409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, P.; Feng, Z.; Yuan, W.; Hu, S.; Yuan, P. Effect of PVA fiber on properties of geopolymer composites: A comprehensive review. J. Mater. Res. Technol. 2024, 29, 4086–4101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kan, L.; Wang, F. Mechanical properties of high ductile alkali-activated fiber reinforced composites incorporating red mud under different curing conditions. Ceram. Int. 2022, 48, 1999–2011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nath, P.; Sarker, P.K. Use of OPC to improve setting and early strength properties of low calcium fly ash geopolymer concrete cured at room temperature. Cem. Concr. Compos. 2015, 55, 205–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, R.; Liu, R.; Qin, G.; Jiang, M.; Wu, Y.; Guo, Y. Study on High-Ductility Geopolymer Concrete: The Influence of Oven Heat Curing Conditions on Mechanical Properties and Microstructural Development. Materials 2024, 17, 4011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mazzuca, P.; Micieli, A.; Campolongo, F.; Ombres, L. Influence of thermal exposure scenarios on the residual mechanical properties of a cement-based composite system. Constr. Build. Mater. 2025, 466, 140304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Presursor and Activator of Matrix of 52 EGC Cases | Curing Regime |

|---|---|

| FA (SH, SMP) [61,95] | High temperature curing + normal temperature curing (cure 5 d at 23 ± 3 °C demolding, 36/48 h at 80 °C, 23 ± 3 °C to 28 d). |

| FA (SH, SSI/SMA, SSI) [79,89,93,112] | High temperature curing + normal temperature curing (60 °C 8 h/70 °C 24 h/90 °C 72 h, room temperature to 28 d); Normal Temperature Curing (room temperature to 7 d). |

| GGBS, SF (SH, SSI) [62,94,103,113] | Normal temperature curing (room temperature/20 °C, 95% R.H. to 28 d); High temperature curing + normal temperature curing (60 °C 1 d, 20 °C, 60% R.H. to 28 d; 80 °C 2 h, Air-cured to test); Low temperature curing (−5 °C to 28 d). |

| FA, GGBS (SMA) [53,56,80] | Normal temperature curing (room temperature/20 ± 2 °C, 95% R.H. /25 °C, ≥80% R.H. to test). |

| FA, GGBS (SH, SSI) [39,47,52,54,55,60,68,71,77,78,81,84,86,87,91,92,98,104,107,108,109,111,112,114] | Normal temperature curing (standard curing room (20 ± 2 °C, 95% R.H.)/curing room (20 ± 3 °C, ≥90% R.H.)/23 ± 2 °C, 95 ± 5% R.H./room temperature to test); High temperature curing + normal temperature curing (60 °C 24 h, standard curing to test; 70 °C 24 h demolding, room temperature to 28 d; 24 h demolding, 80 °C to 3 d; plastic wrap sealing, 80 °C 2 h, room temperature to test; constant temperature (20 °C) and humidity 24 h demolding, 60 °C/80 °C constant temperature and humidity to test); Curing in water (curing in water to test). |

| FA, GGBS, SF (SMA + SSI) [70,72,99] | High temperature curing + normal temperature curing (80 °C 72 h remove to test); Normal temperature curing (room temperature to 28 d). |

| FA, GGBS, SF (SH + SSI) [59,74,85,86] | High temperature curing + curing in water (48 h demolding, 100 °C 24 h, 23 ± 3 °C curing in water to 28 d); Normal temperature curing (room temperature (20 ± 2 °C, 95% R.H.) to test). |

| FA, GGBS, SSL (SH + SSI) [37,73,111] | Curing in water (curing in water to test); Normal temperature curing (20~25 °C to test). |

| MK, SF/MK, RCP/MK, SF, GGBS (SMA + SSI) [47,64,110] | High temperature curing + normal temperature curing (80 °C 24 h, room temperature to 3/7 d). |

| FA, GGBS, SF, MK (SH + SSI) [57,66,67,69,90] | Normal temperature curing (standard curing room/box (20 ± 2 °C, ≥95%R.H.); Standard curing room (17~23 °C, ≥90% R.H.) to 28 d). |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Wan, X.; Guo, W.; Cong, J.; Wang, C.; Han, M. Review of the Relationship Between the Composition, Strength, and Ultimate Tensile Strain of Engineering Geopolymer Composites. Materials 2025, 18, 5603. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma18245603

Wan X, Guo W, Cong J, Wang C, Han M. Review of the Relationship Between the Composition, Strength, and Ultimate Tensile Strain of Engineering Geopolymer Composites. Materials. 2025; 18(24):5603. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma18245603

Chicago/Turabian StyleWan, Xiaomei, Weili Guo, Jiahao Cong, Chen Wang, and Mingjin Han. 2025. "Review of the Relationship Between the Composition, Strength, and Ultimate Tensile Strain of Engineering Geopolymer Composites" Materials 18, no. 24: 5603. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma18245603

APA StyleWan, X., Guo, W., Cong, J., Wang, C., & Han, M. (2025). Review of the Relationship Between the Composition, Strength, and Ultimate Tensile Strain of Engineering Geopolymer Composites. Materials, 18(24), 5603. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma18245603