Modification of Sunflower Stalks as a Template for Biochar Adsorbent for Effective Cu(II) Containing Wastewater Treatment

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

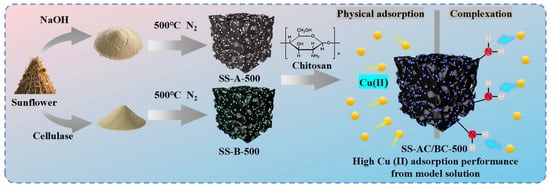

2.2. Preparation of Sunflower Straw Derived Adsorbents

2.3. Adsorption Experiments

2.3.1. Single-Factor Adsorption

2.3.2. Adsorption Kinetics

2.3.3. Adsorption Isotherm

2.4. Characterization

3. Results and Discussion

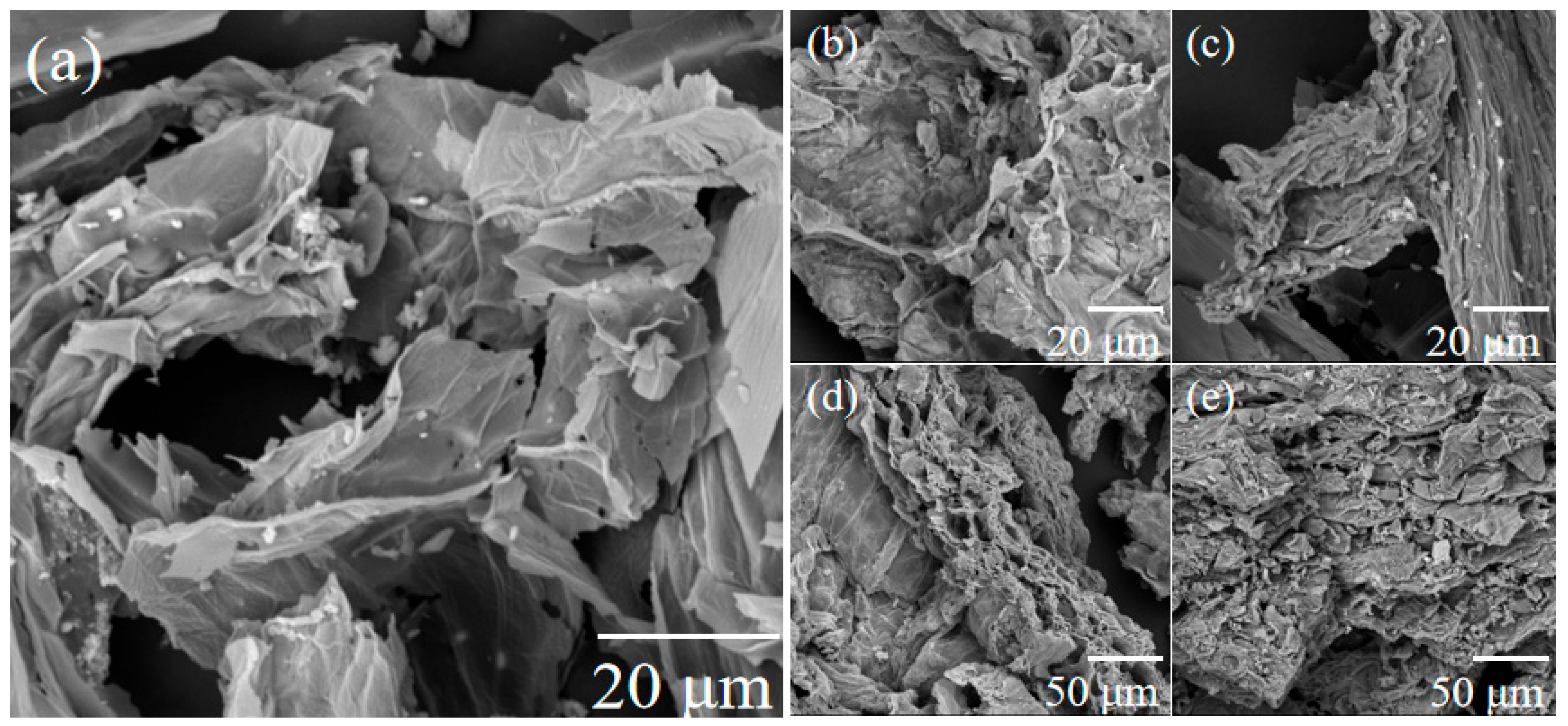

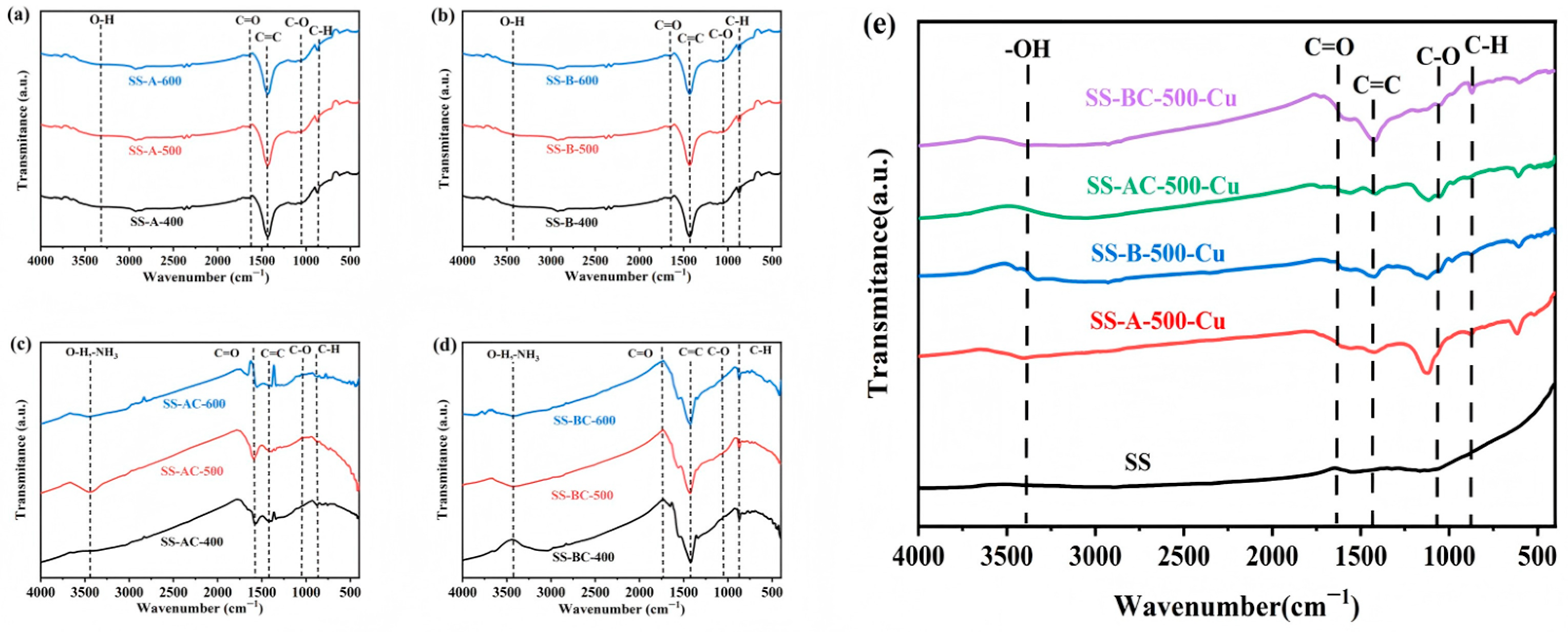

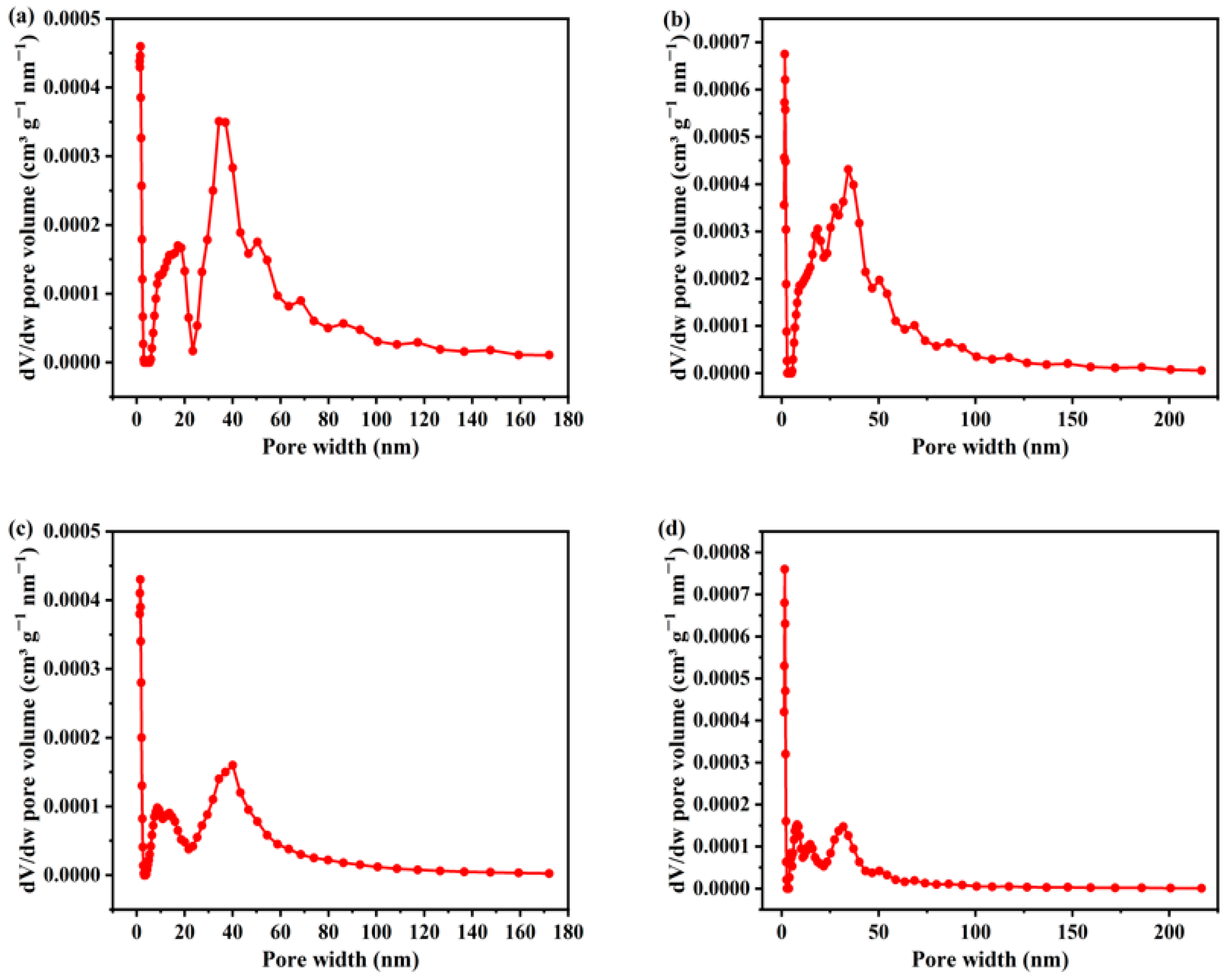

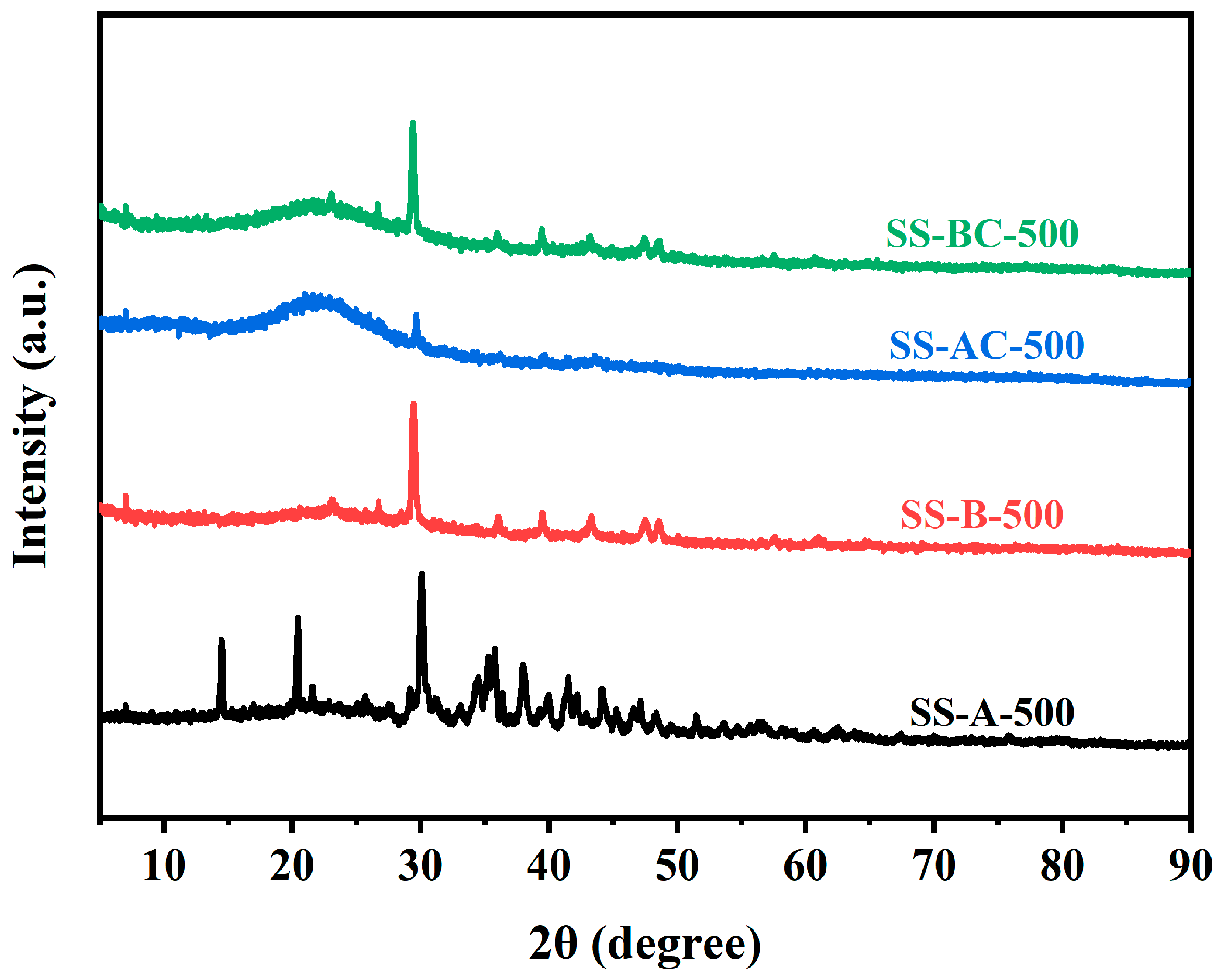

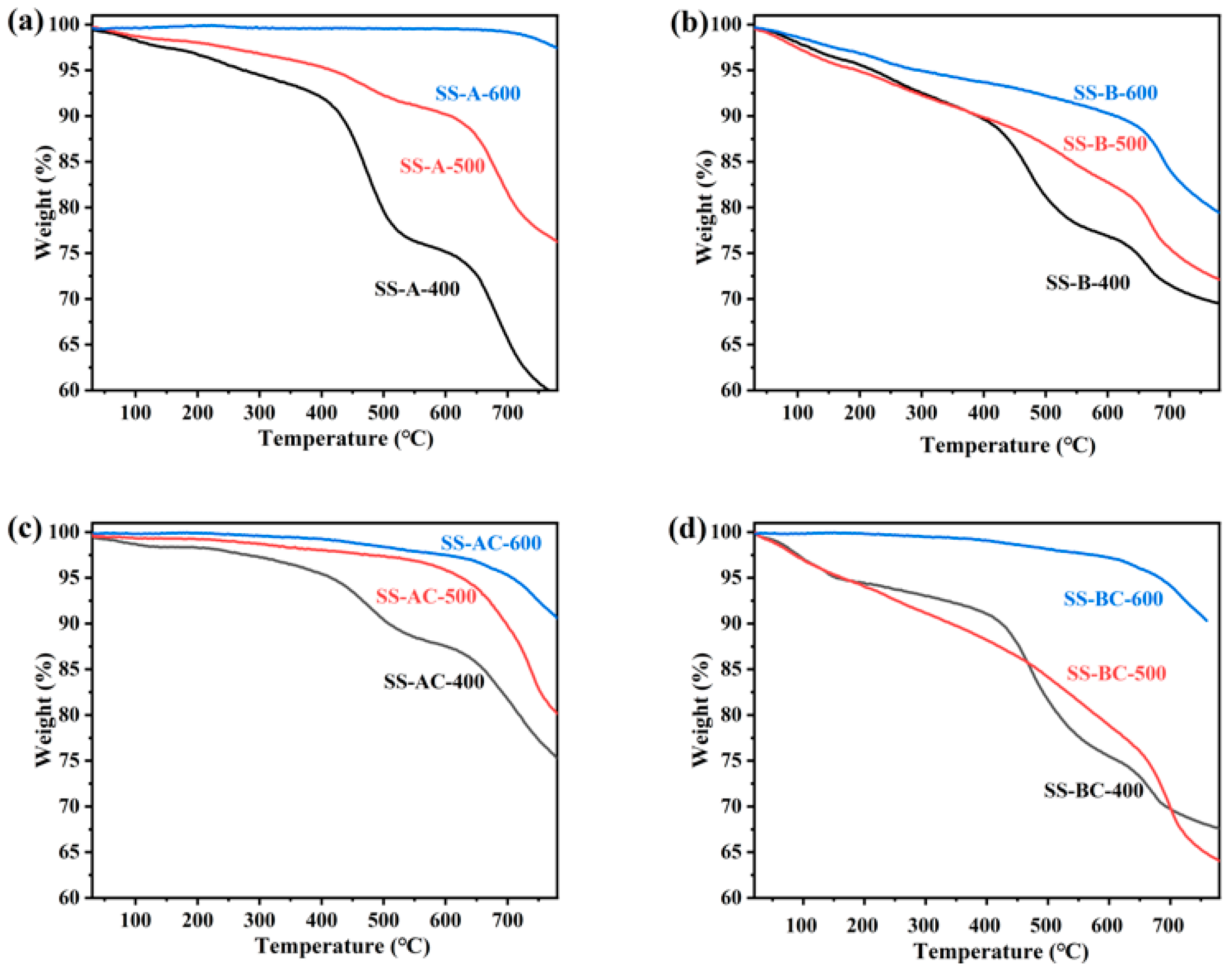

3.1. Characterization of the Sunflower-Derived Biochar Adsorbents

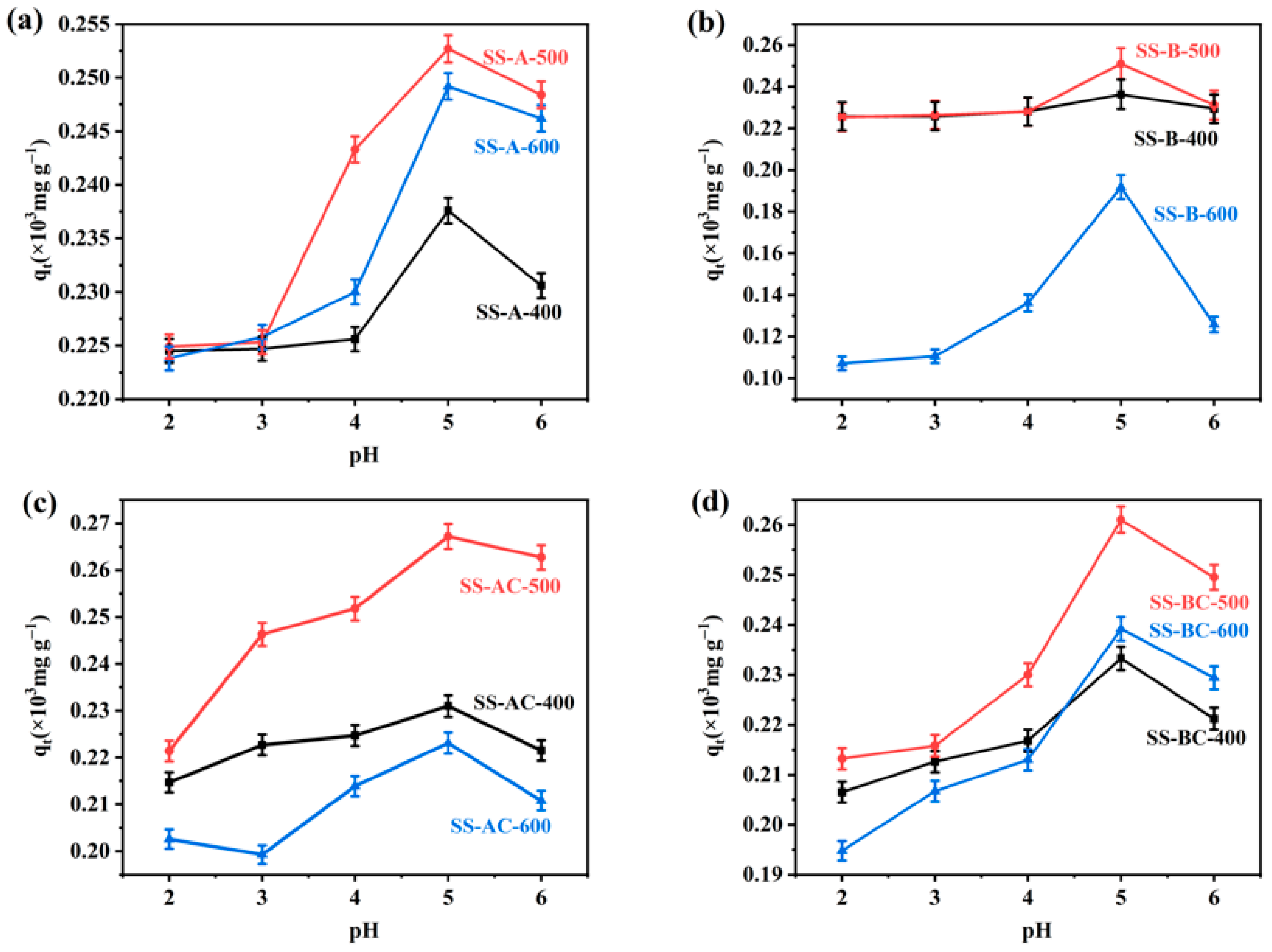

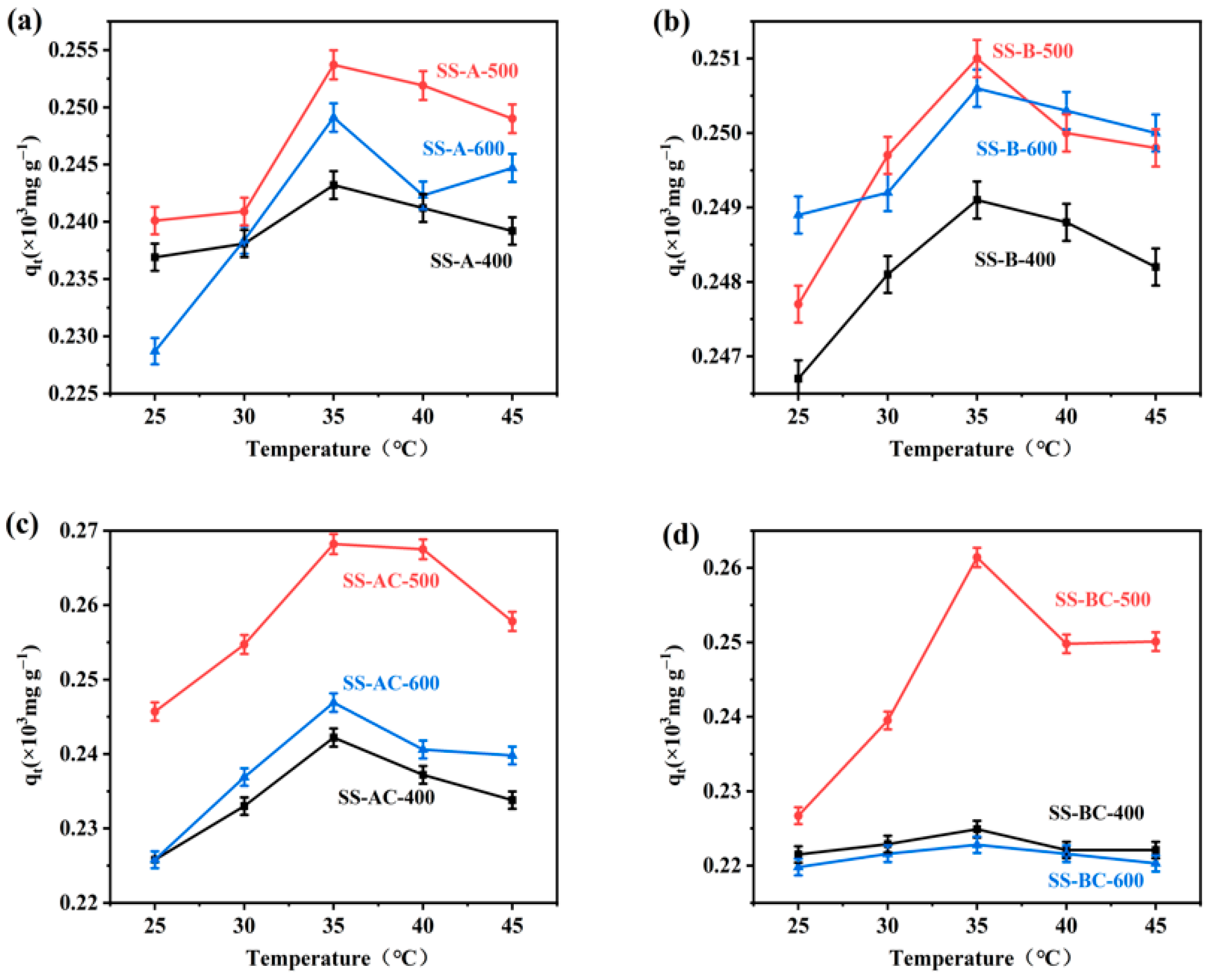

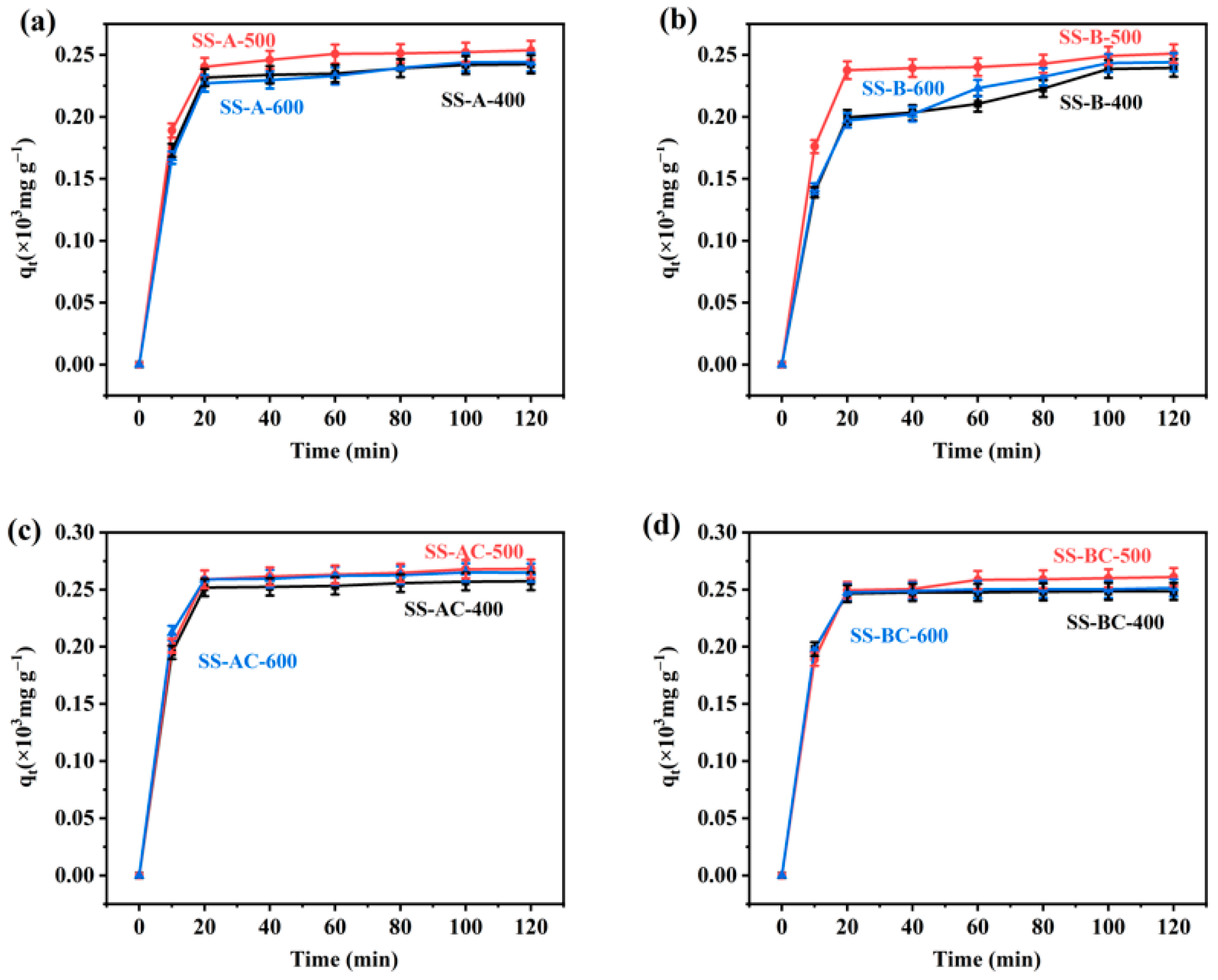

3.2. Analysis of Single-Factors

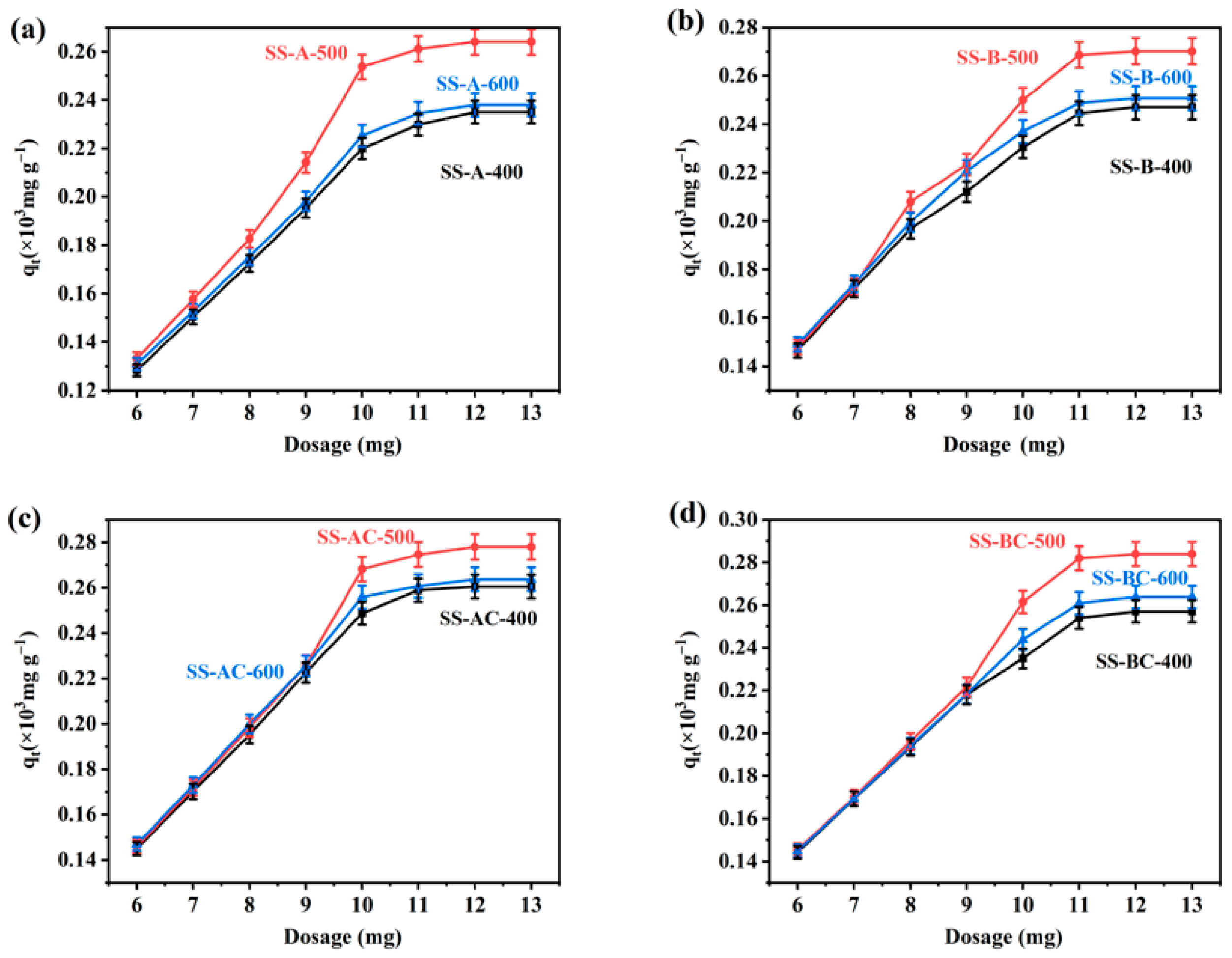

3.3. Adsorption Kinetics Fitting Analysis

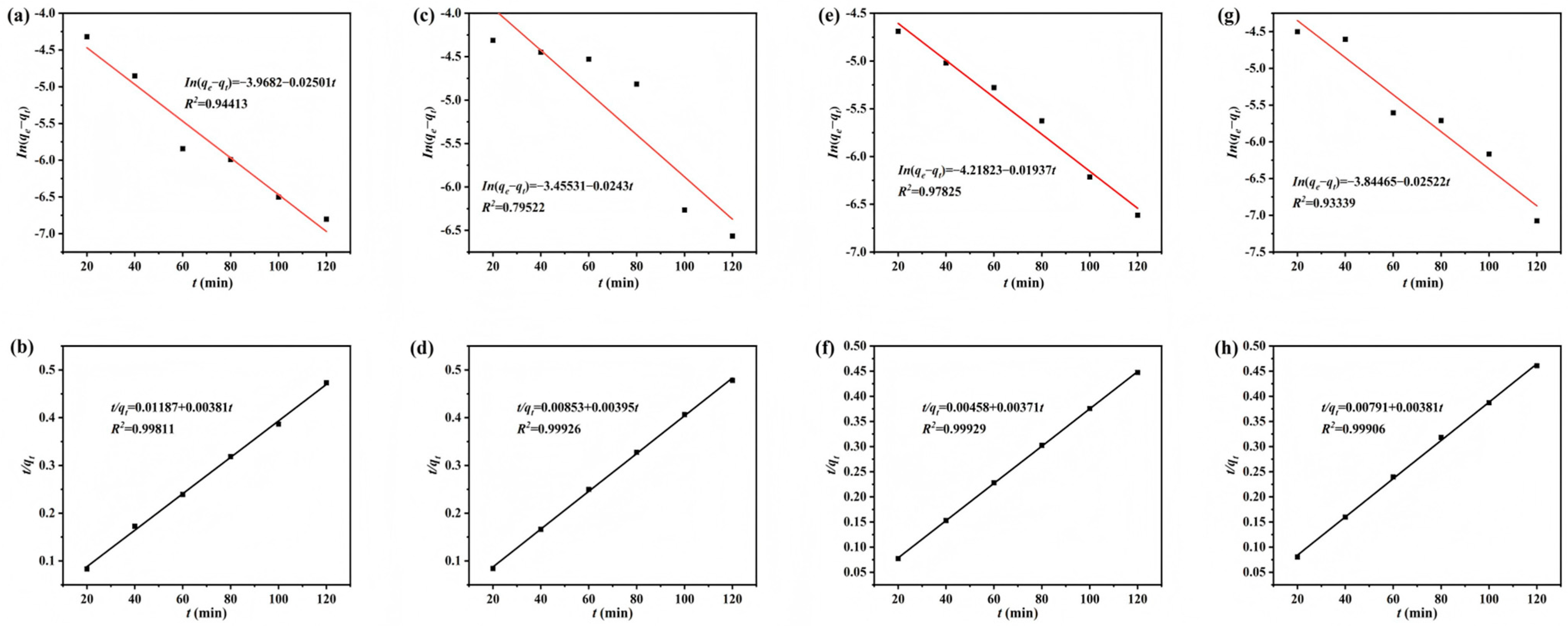

3.4. Adsorption Isotherm Fitting Analysis

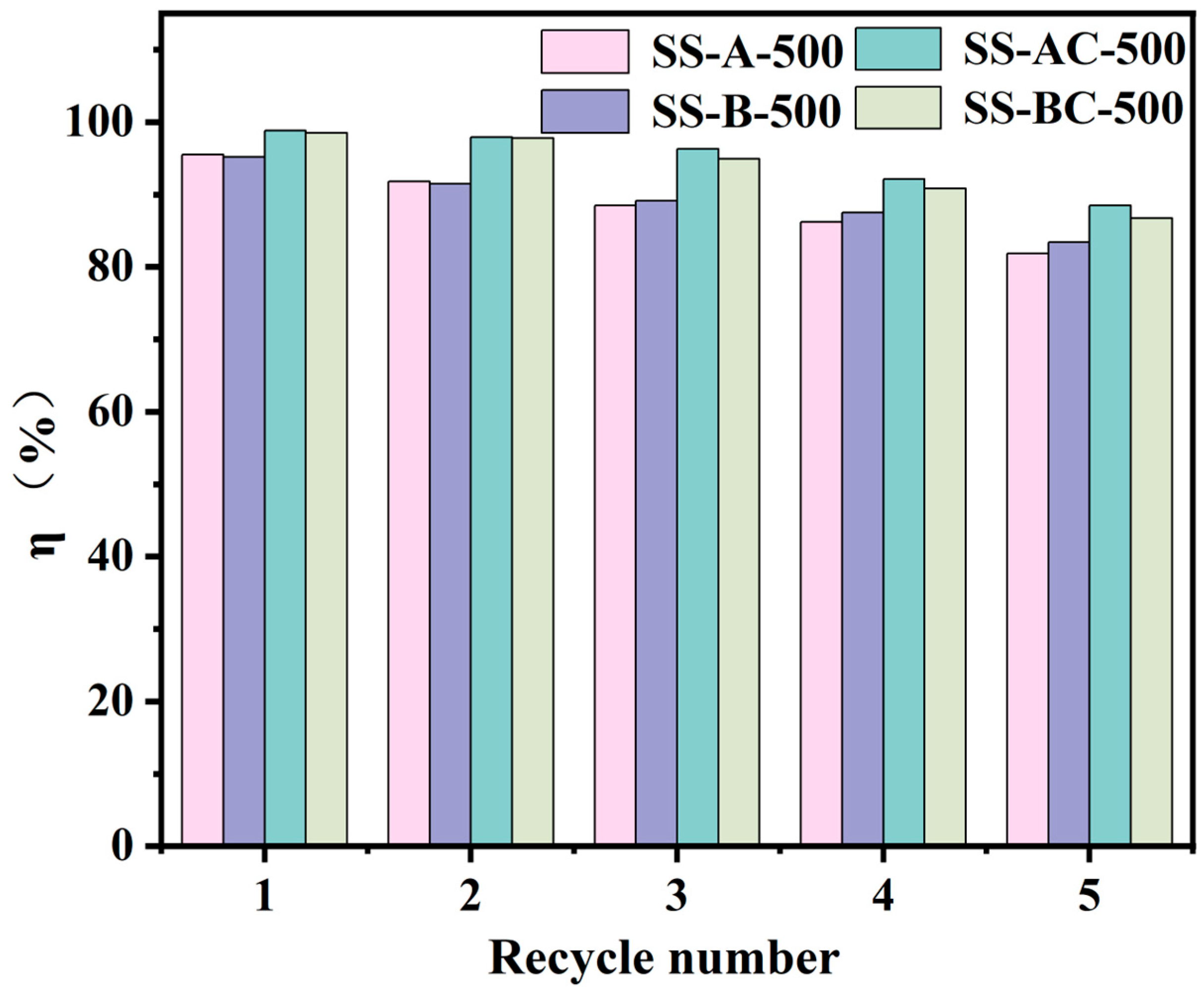

3.5. Analysis of Regenerative Effects and Comparison Study

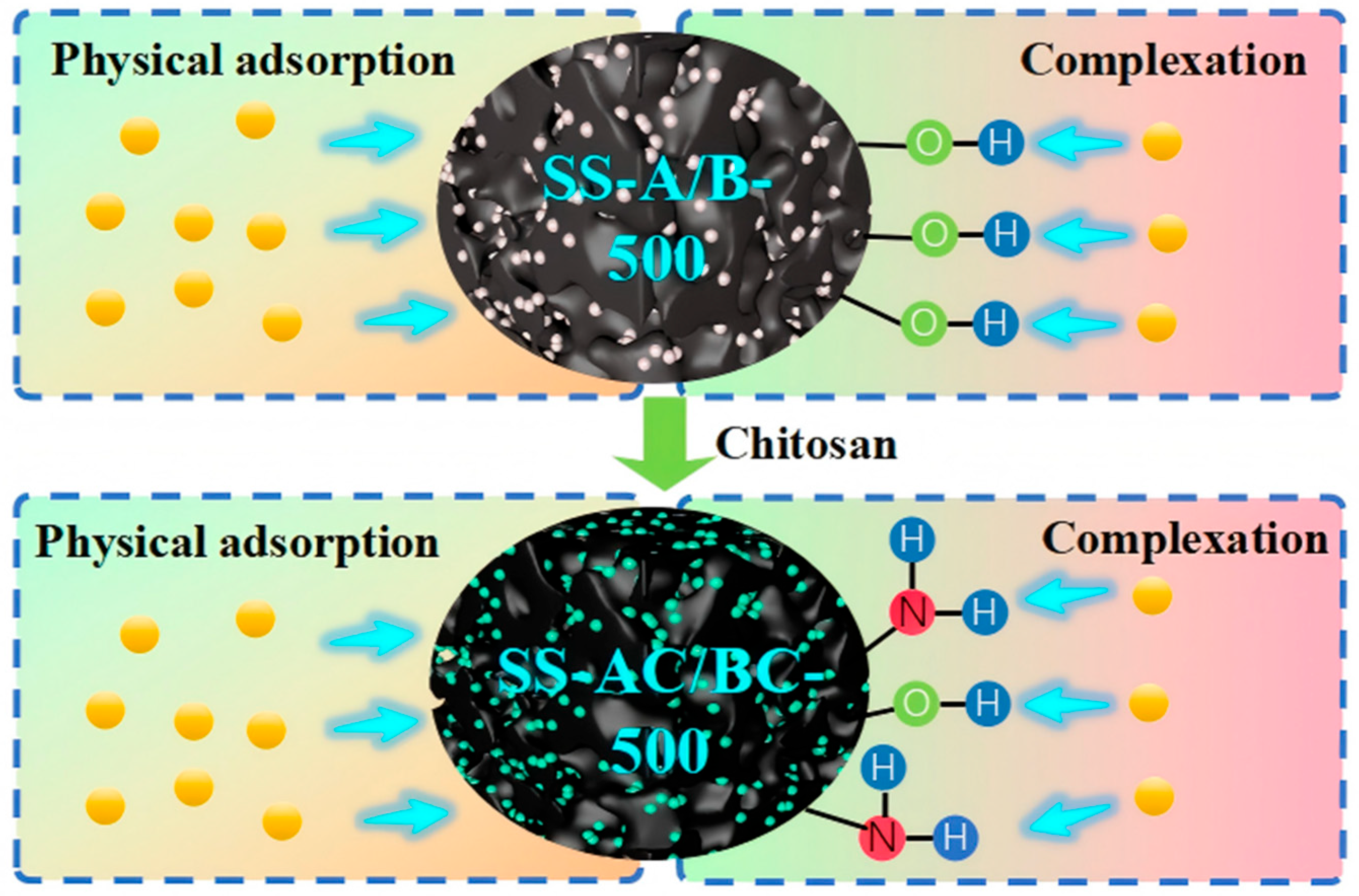

3.6. Sorption Mechanisms

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Yan, K.; Wang, H.; Lan, Z.; Zhou, J.; Fu, H.; Wu, L.; Xu, J. Heavy metal pollution in the soil of contaminated sites in China: Research status and pollution assessment over the past two decades. J. Clean. Prod. 2022, 373, 133780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, T.; Chen, W.Q.; Ma, Y.; Qian, Q.; Jia, J. Environmental impacts and improvement potentials for copper mining and mineral processing operations in China. J. Environ. Manag. 2023, 342, 118178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, W.; Liu, X.; Lyu, X.; Gao, W.; Su, H.; Li, C. Extraction and separation of copper and iron from copper smelting slag: A review. J. Clean. Prod. 2022, 368, 133095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeevarajan, J.A.; Joshi, T.; Parhizi, M.; Rauhala, T.; Juarez-Robles, D. Battery hazards for large energy storage systems. ACS Energy Lett. 2022, 7, 2725–2733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alsawy, T.; Rashad, E.; El-Qelish, M.; Mohammed, R.H. A comprehensive review on the chemical regeneration of biochar adsorbent for sustainable wastewater treatment. NPJ Clean Water 2022, 5, 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maroušek, J.; Minofar, B.; Maroušková, A.; Strunecký, O.; Gavurová, B. Environmental and economic advantages of production and application of digestate biochar. Environ. Technol. Innov. 2023, 30, 103109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inyang, M.I.; Gao, B.; Yao, Y.; Xue, Y.; Zimmerman, A.; Mosa, A.; Pullammanappallil, P.; Ok, Y.S.; Cao, X. A review of biochar as a low-cost adsorbent for aqueous heavy metal removal. Crit. Rev. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2016, 46, 406–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loc, N.X.; Tuyen, P.T.T.; Mai, L.C.; Phuong, D.T.M. Chitosan-modified biochar and unmodified biochar for methyl orange: Adsorption characteristics and mechanism exploration. Toxics 2022, 10, 500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, X.; Cheng, H.; Ye, G.; Fan, J.; Yao, F.; Wang, Y.; Jiao, Y.; Zhu, W.; Huang, H.; Ye, D. Key factors and primary modification methods of activated carbon and their application in adsorption of carbon-based gases: A review. Chemosphere 2022, 287, 131995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, Q.; Zhu, G.; Wang, R.; Zhao, Z. Enhancement of the thermal properties of the phase change composite of acid-base modified biochar/paraffin wax. Sol. Energy Mater. Sol. Cells 2024, 269, 112802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hawryluk-Sidoruk, M.; Raczkiewicz, M.; Krasucka, P.; Duan, W.; Mašek, O.; Zarzycki, R.; Kobyłecki, R.; Pan, B.; Oleszczuk, P. Effect of biochar chemical modification (acid, base and hydrogen peroxide) on contaminants content depending on feedstock and pyrolysis conditions. Chem. Eng. J. 2024, 481, 148329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, X.; Wang, X.; Ge, Z.; Bao, Z.; Lin, L.; Chen, Y.; Dai, W.; Sun, Y.; Yuan, H.; Yang, W.; et al. KOH-activated biochar and chitosan composites for efficient adsorption of industrial dye pollutants. Chem. Eng. J. 2024, 486, 150387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, M.; Liu, G.; Liu, R.; Xu, J.; Si, W.; Wei, Y. High-efficient co-removal of copper and zinc by modified biochar derived from tea stalk: Characteristics, adsorption behaviors, and mechanisms. J. Water Process Eng. 2024, 57, 104533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zou, M.; Tian, W.; Chu, M.; Gao, H.; Zhang, D. Biochar composite derived from cellulase hydrolysis apple branch for quinolone antibiotics enhanced removal: Precursor pyrolysis performance, functional group introduction and adsorption mechanisms. Environ. Pollut. 2022, 313, 120104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, H.; Wu, S.; Zhou, J. Preparation and modification of nanocellulose and its application to heavy metal adsorption: A review. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2023, 236, 123916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, B.; Liu, Y.; Tong, W.K.; Zhang, J.B.; Tang, H.; Wang, W.; Gao, M.-T.; Dai, C.; Liu, N.; Hu, J.; et al. Effects of cellulase treatment on properties of lignocellulose-based biochar. Bioresour. Technol. 2024, 413, 131452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, H.; Al-Kurdhani, J.M.H.; Ma, J.; Wang, Y. Adsorption of Zn2+ ion by macadamia nut shell biochar modified with carboxymethyl chitosan and potassium ferrate. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2023, 11, 110150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adeniyi, A.G.; Micheal, T.T.; Emenike, E.C.; Abd-Elkader, O.H.; Iwuozor, K.O.; Al-Lohedan, H.A.; Hambali, H.U.; Ezzat, A.O.; Adeeyo, T.; Amoloye, M.A.; et al. Production and characterization of sunflower stalk biochar and ash: A study on batch versus semi-batch gasifier systems. Int. J. Chem. React. Eng. 2025, 23, 577–595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, Z.; Wu, C.; Tang, W.; Huang, M.; Ma, C.; He, Y.-C. Enhancing enzymatic saccharification of sunflower straw through optimal tartaric acid hydrothermal pretreatment. Bioresour. Technol. 2023, 385, 129279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, Z.; Huang, S.; Zhao, Q.; Xin, L. Respective evolution of soil and biochar on competitive adsorption mechanisms for Cd(II), Ni(II), and Cu(II) after 2-year natural ageing. J. Hazard. Mater. 2024, 469, 133938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Z.Y.; Shi, L.Q.; Liang, D.K.; Li, F.X.; Wei, L.H.; Li, W.Z.; Zha, X.H. Study on the hydrocarbon-rich bio-oil from catalytic fast co-pyrolysis cotton stalk and polypropylene over alkali-modified HZSM-5. Ind. Crops Prod. 2025, 224, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.; Wen, J.; Su, C.; Jiang, C.; Zhang, C.; Wang, Y.; Jiang, Y.; Ren, W.; Qin, P.; Cai, D. Inhibitions of microbial fermentation by residual reductive lignin oil: Concerns on the bioconversion of reductive catalytic fractionated carbohydrate pulp. Chem. Eng. J. 2023, 452, 139267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, S.; Wong, A.; Zanoni, M.V.B.; Sotomayor, M.D.P.T. Electrochemical sensors based on biomimetic magnetic molecularly imprinted polymer for selective quantification of methyl green in environmental samples. Mater. Sci. Eng. C 2019, 103, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xia, C.F.; Huang, H.H.; Liang, D.R.; Xie, Y.; Kong, F.P.; Yang, Q.H.; Fu, J.X.; Dou, Z.W.; Zhang, Q.; Meng, Z.L. Adsorption of tetracycline hydrochloride on layered double hydroxide loaded carbon nanotubes and site energy distribution analysis. Chem. Eng. J. 2022, 443, 136398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cortés, J.-C.; Navarro-Quiles, A.; Santonja, F.-J.; Sferle, S.-M. Statistical analysis of randomized pseudo-first/second order kinetic models. Application to study the adsorption on cadmium ions onto tree fern. Chemom. Intell. Lab. Syst. 2023, 240, 104910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tran, H.N. Applying Linear Forms of Pseudo-Second-Order Kinetic Model for Feasibly Identifying Errors in the Initial Periods of Time-Dependent Adsorption Datasets. Water 2023, 15, 1231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ezzati, R.; Ezzati, S.; Azizi, M. Exact solution of the Langmuir rate equation: New Insights into pseudo-first-order and pseudo-second-order kinetics models for adsorption. Vacuum 2024, 220, 112790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pietrelli, L.; Francolini, I.; Piozzi, A. Dyes Adsorption from Aqueous Solutions by Chitosan. Sep. Sci. Technol. 2015, 50, 1101–1107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Debnath, S.; Das, R. Strong adsorption of CV dye by Ni ferrite nanoparticles for waste water purification: Fits well the pseudo second order kinetic and Freundlich isotherm model. Ceram. Int. 2023, 49, 16199–16215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, D.H.; Zhang, X.D.; Wu, Y.D.; Liu, X. Adsorption of anionic dyes from aqueous solution on fly ash. J. Hazard. Mater. 2010, 181, 335–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boughrara, L.; Zaoui, F.; Guezzoul, M.; Sebba, F.Z.; Bounaceur, B.; Kada, S.O. New alginic acid derivatives ester for methylene blue dye adsorption: Kinetic, isotherm, thermodynamic, and mechanism study. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2022, 205, 651–663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, D.; Li, P.; Luo, Z.; Qin, P.; Chen, C.; Wang, Y.; Wang, Z.; Tan, T. Effect of dilute alkaline pretreatment on the conversion of different parts of corn stalk to fermentable sugars and its application in acetone–butanol–ethanol fermentation. Bioresour. Technol. 2016, 211, 117–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, D.; Li, P.; Chen, C.; Wang, Y.; Hu, S.; Cui, C.; Qin, P.; Tan, T. Effect of chemical pretreatments on corn stalk bagasse as immobilizing carrier of Clostridium acetobutylicum in the performance of a fermentation-pervaporation coupled system. Bioresour. Technol. 2016, 220, 68–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, B.; Cai, D.; Luo, Z.; Chen, C.; Zhang, C.; Qin, P.; Cao, H.; Tan, T. Corncob residual reinforced polyethylene composites considering the biorefinery process and the enhancement of performance. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 198, 452–462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raczkiewicz, M.; Ostolska, I.; Mašek, O.; Oleszczuk, P. Effect of the pyrolysis conditions and type of feedstock on nanobiochars obtained as a result of ball milling. J. Clean. Prod. 2024, 458, 142456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nandiyanto, A.B.D.; Ragadhita, R.; Fiandini, M. Interpretation of Fourier transform infrared spectra (FTIR): A practical approach in the polymer/plastic thermal decomposition. Indones. J. Sci. Technol. 2023, 8, 113–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, P.; Cai, D.; Luo, Z.; Qin, P.; Chen, C.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, C.; Wang, Z.; Tan, T. Effect of acid pretreatment on different parts of corn stalk for second generation ethanol production. Bioresour. Technol. 2016, 206, 86–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Afessa, M.M.; Olu, F.E.; Geleta, W.S.; Legese, S.S.; Ramayya, A.V. Unlocking the potential of biochar derived from coffee husk and khat stem for catalytic tar cracking during biomass pyrolysis: Characterization and evaluation. Biomass Convers. Biorefinery 2025, 15, 11011–11026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Cai, D.; Jiang, Y.; Mei, X.; Ren, W.; Sun, M.; Su, C.; Cao, H.; Zhang, C.; Qin, P. Rapid fractionation of corn stover by microwave-assisted protic ionic liquid [TEA][HSO4] for fermentative acetone–butanol–ethanol production. Biotechnol. Biofuels Bioprod. 2024, 17, 62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, Y.; Shan, H.; Jiang, Y.; Zhang, Z.; Jiao, J.; Wang, M.; Cai, D.; Zhang, R.; Jiao, T. Bifunctional Membrane Design Based on Thiol-Functionalized Triazine-Containing Covalent Organic Polymer for Integrated Mercury Ion Removal and Monitoring. J. Membr. Sci. 2025, 733, 124316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, R.; Li, Y.; Meng, B.; Liu, Y.; Zeng, J.; Weng, G.; Shan, H.; Cai, D.; Huang, X.; Jin, L. Highly selective recovery of palladium using innovative double-layer adsorptive membranes. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2024, 337, 126460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Ghamdi, A.A.; Galhoum, A.A.; Alshahrie, A.; Al-Turki, Y.A.; Al-Amri, A.M.; Wageh, S. Superparamagnetic multifunctionalized chitosan nanohybrids for efficient copper adsorption: Comparative performance, stability, and mechanism insights. Polymers 2023, 15, 1157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bąk, J.; Thomas, P.; Kołodyńska, D. Chitosan-modified biochars to advance research on heavy metal ion removal: Roles, mechanism and perspectives. Materials 2022, 15, 6108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, C.; Qiao, J.; Yuan, J.; Tang, Z.; Chu, T.; Lin, R.; Wen, H.; Zheng, C.; Chen, H.; Xie, H.; et al. Novel chitosan-modified biochar prepared from a Chinese herb residue for multiple heavy metals removal: Characterization, performance and mechanism. Bioresour. Technol. 2024, 402, 130830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ethaib, S.; Al-Qutaifia, S.; Al-Ansari, N.; Zubaidi, S.L. Function of nanomaterials in removing heavy metals for water and wastewater remediation: A review. Environments 2022, 9, 123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azadian, M.; Gilani, H.G. Adsorption of Cu2+, Cd2+, and Zn2+ by engineered biochar: Preparation, characterization, and adsorption properties. Environ. Prog. Sustain. Energy 2023, 42, e14088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shafeeq, K.; Rayes, S.M.E.; Khalil, M.M.H.; Shah, R.K.; Saad, F.A.; Khairy, M.; Algethami, F.K.; Abdelrahman, E.A. Functionalization of calcium silicate/sodium calcium silicate nanostructures with chitosan and chitosan/glutaraldehyde as novel nanocomposites for the efficient adsorption of Cd (II) and Cu (II) ions from aqueous solutions. Silicon 2024, 16, 1713–1730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- No, H.K.; Kim, S.H.; Lee, S.H.; Park, N.Y.; Prinyawiwatkul, W. Stability and antibacterial activity of chitosan solutions affected by storage temperature and time. Carbohydr. Polym. 2006, 65, 174–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, B.; Chen, T.; Wang, B.; Zhou, S.; Zhang, Z.; Li, Y.; Pan, X.; Wang, N. Enhanced removal of Cd2+ from water by AHP-pretreated biochar: Adsorption performance and mechanism. J. Hazard. Mater. 2022, 438, 129467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Das, N.C.; Rahman, M.M.; Kabir, S.F. Preparation of novel clay/chitosan/ZnO bio-composite as an efficient adsorbent for tannery wastewater treatment. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2023, 249, 126136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Binti Abdullah, N.A.; Badiei, M.; Mohammad, M.; Asim, N.; Yaakob, Z.; Othman, M.A.R. Monocomponent Biosorption of Copper Ions (II) onto Nanocrystalline Cellulose from Coconut Husk Fibers. Curr. Nanosci. 2024, 20, 564–575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lv, X.; Zhou, X.; Yang, R.; Cai, D.; Ren, W. Enzymatic Modification of Walnut Shell for High-Efficiency Adsorptive Methylene Blue Removal. Materials 2025, 18, 3434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Yang, Y.; Shan, H.; Zhao, J.; Wang, Z.; Cai, D.; Qin, P.; Baeyens, J.; Tan, T. Ultrafast and ultrahigh adsorption of furfural from aqueous solution via covalent organic framework-300. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2019, 220, 283–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Zhong, S.; Zheng, X.; Xiao, D.; Zheng, L.; Yang, Y.; Zhang, H.; Ai, B.; Sheng, Z. Calcite modification of agricultural waste biochar highly improves the adsorption of Cu(II) from aqueous solutions. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2021, 9, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Yang, X.; Liu, H.; Cheng, W.; Bao, Y. Modification of calcium-rich biochar by loading Si/Mn binary oxide after NaOH activation and its adsorption mechanisms for removal of Cu(II) from aqueous solution. Colloids Surf. A Physicochem. Eng. Asp. 2020, 601, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kareem, R.; Afkhami, A.; Aziz, K.H.H. Synthesis of a novel magnetic biochar composite enhanced with polyaniline for high-performance adsorption of heavy metals: Focus on Hg(ii) and Cu(ii). Rsc Adv. 2025, 15, 20309–20320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hu, J.J.; Yang, S.H.; Ma, P.Y.; Deng, Z.H. Adsorption of Cu(II), Pb(II), Cd(II), and Cr(III) from aqueous solutions using modified coffee grounds biochar. Desalin. Water Treat. 2025, 323, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Truong, Q.M.; Ho, P.N.T.; Nguyen, T.B.; Chen, W.-H.; Bui, X.-T.; Patel, A.K.; Singhania, R.R.; Chen, C.-W.; Dong, C.-D. Magnetic biochar derived from macroalgal Sargassum hemiphyllum for highly efficient adsorption of Cu(II): Influencing factors and reusability. Bioresour. Technol. 2022, 361, 127732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Adsorbents | BET Surface Area |

|---|---|

| SS-A-500 | 147 ± 5 m2 g−1 |

| SS-B-500 | 162 ± 5 m2 g−1 |

| SS-AC-500 | 103 ± 4 m2 g−1 |

| SS-BC-500 | 119 ± 4 m2 g−1 |

| Adsorbent | Langmuir | Freundlich | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| qe cal (mg g−1) | qe exp (mg g−1) | KL | R2 | 1/n | Kf | R2 | |

| SS-A-500 | 253.7 | 254.2 | 0.0996 | 0.99 | 0.584 | 10.35 | 0.85 |

| SS-A-500 | 251.0 | 251.8 | 0.1002 | 0.99 | 0.578 | 11.28 | 0.84 |

| SS-AC-500 | 268.2 | 268.9 | 0.0945 | 0.99 | 0.462 | 18.52 | 0.94 |

| SS-BC-500 | 261.4 | 262.3 | 0.0989 | 0.99 | 0.472 | 19.51 | 0.86 |

| Type of Biochar | Pyrolysis Temperature (°C) | Modifying Agent | Adsorption Capacity (mg g−1) | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Coconut shells | 600 | Calcite | 213.9 | [54] |

| Shrimp shell | 800 | NaOH | 141.76 | [55] |

| Sesame | 600 | Aniline | 124.78 | [56] |

| Coffee Ground | 800 | KOH | 75.02 | [57] |

| Brown algae | 700 | Ethylenediamine | 105.3 | [58] |

| SS-A-500 | 500 | NaOH | 253.7 | Present study |

| SS-B-500 | 500 | Cellulase | 251.0 | Present study |

| SS-AC-500 | 500 | NaOH + Chitosan | 268.2 | Present study |

| SS-BC-500 | 500 | Cellulase + Chitosan | 261.4 | Present study |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Yang, R.; Zhou, X.; Zhang, C.; Zhang, X.; Bao, Q.; Qi, Y.; Liu, X.; Sun, M.; Lv, X.; Cai, D. Modification of Sunflower Stalks as a Template for Biochar Adsorbent for Effective Cu(II) Containing Wastewater Treatment. Materials 2025, 18, 5604. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma18245604

Yang R, Zhou X, Zhang C, Zhang X, Bao Q, Qi Y, Liu X, Sun M, Lv X, Cai D. Modification of Sunflower Stalks as a Template for Biochar Adsorbent for Effective Cu(II) Containing Wastewater Treatment. Materials. 2025; 18(24):5604. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma18245604

Chicago/Turabian StyleYang, Ruiqi, Xuejian Zhou, Chunhui Zhang, Xinyue Zhang, Qiyu Bao, Yanou Qi, Xiangshi Liu, Mingyuan Sun, Xifeng Lv, and Di Cai. 2025. "Modification of Sunflower Stalks as a Template for Biochar Adsorbent for Effective Cu(II) Containing Wastewater Treatment" Materials 18, no. 24: 5604. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma18245604

APA StyleYang, R., Zhou, X., Zhang, C., Zhang, X., Bao, Q., Qi, Y., Liu, X., Sun, M., Lv, X., & Cai, D. (2025). Modification of Sunflower Stalks as a Template for Biochar Adsorbent for Effective Cu(II) Containing Wastewater Treatment. Materials, 18(24), 5604. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma18245604