Brazeability Study of an Additively Manufactured CuCrZr Alloy to Tungsten Using Various Cu-Based Fillers

Highlights

- Cu13Ge and Cu19Ge fillers produced high-quality joints between CuCrZr and tungsten, while Cu33Ge led to brittle and discontinuous interfaces.

- The Cu20Ti filler generated Ti-rich brittle phases that caused cracking, making it unsuitable for this application.

- CuCrZr softened during brazing due to dissolution of strengthening precipitates, but its hardness could be restored through post-brazing heat treatments; the best result was obtained with Cu13Ge after solution annealing and aging, reaching ~116 HV0.1.

- Cu13Ge is identified as the most promising filler for achieving mechanically reliable CuCrZr–W joints.

- Post-brazing heat treatments are essential to recover the mechanical properties of CuCrZr for fusion-relevant operating conditions.

- Optimizing the brazing process supports the development of DEMO divertor components by improving structural integrity and heat-dissipation performance.

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials and Fabrication of the Fillers

2.2. Brazing Process and Post-Brazing Heat Treatments

2.3. Characterization Techniques

3. Results

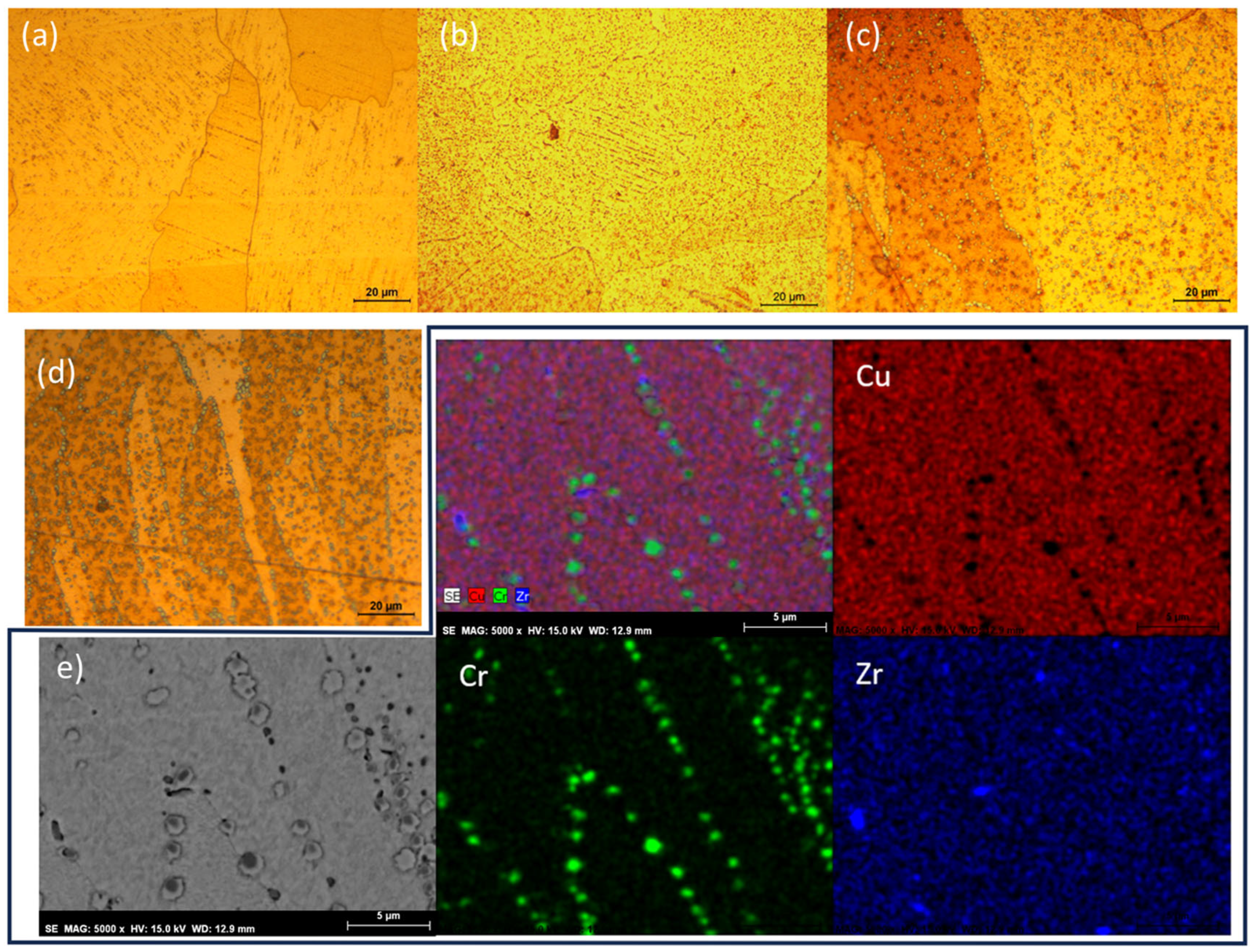

3.1. Characterization of CuCrZr Base Material

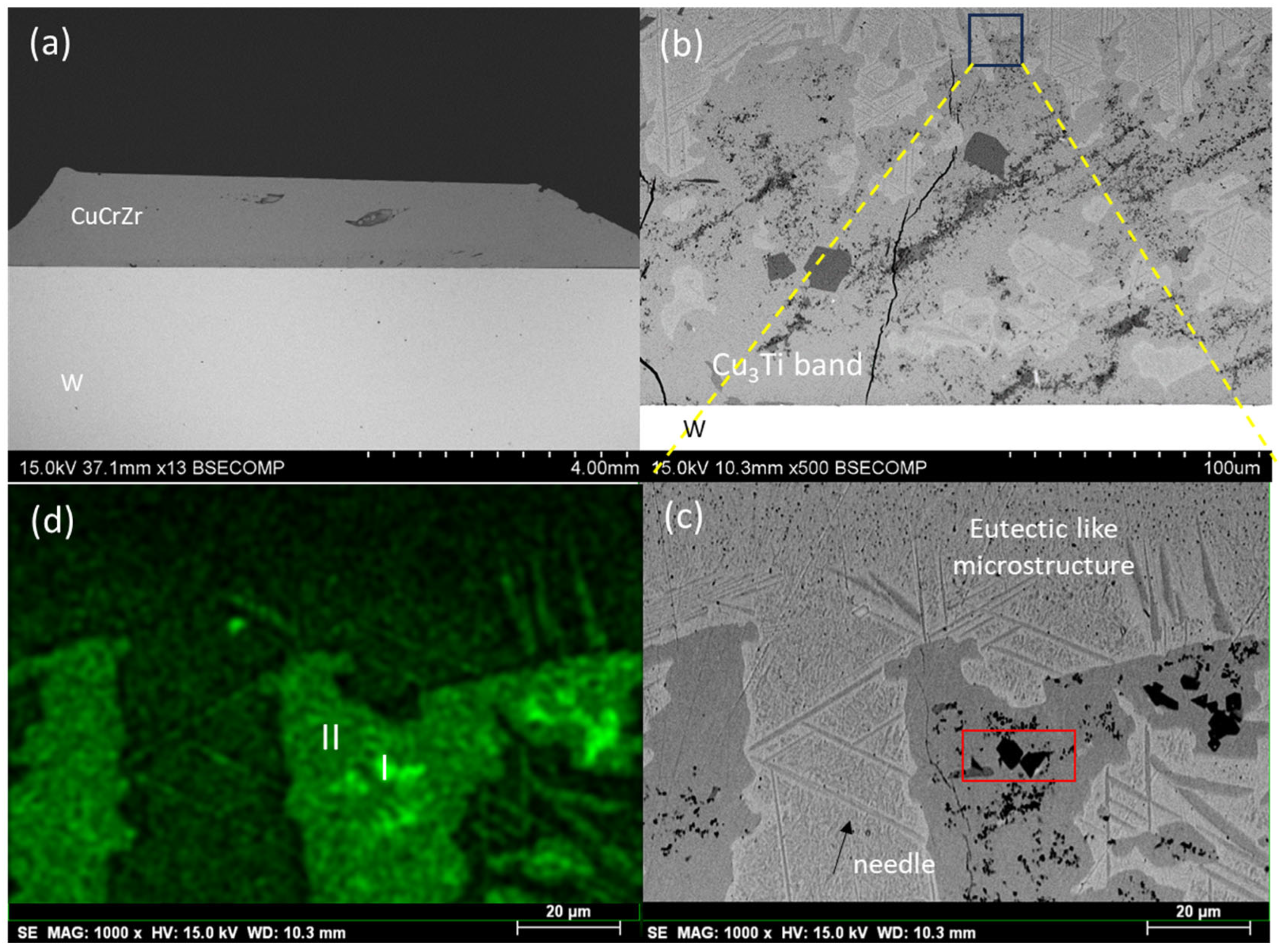

3.2. Microstructural Characterization of Brazed Joints

3.2.1. Cu13Ge

3.2.2. Cu19Ge

3.2.3. Cu33Ge

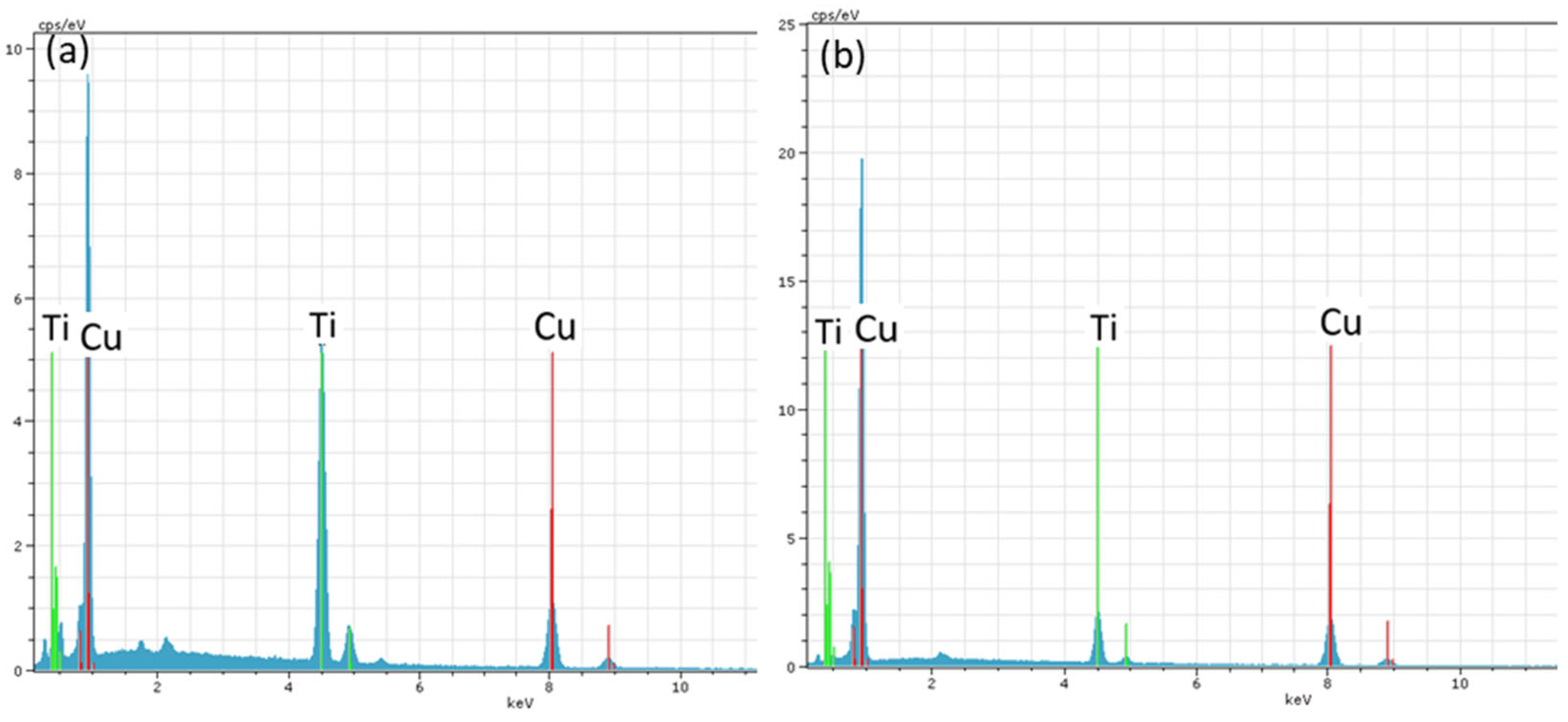

3.2.4. Cu20Ti

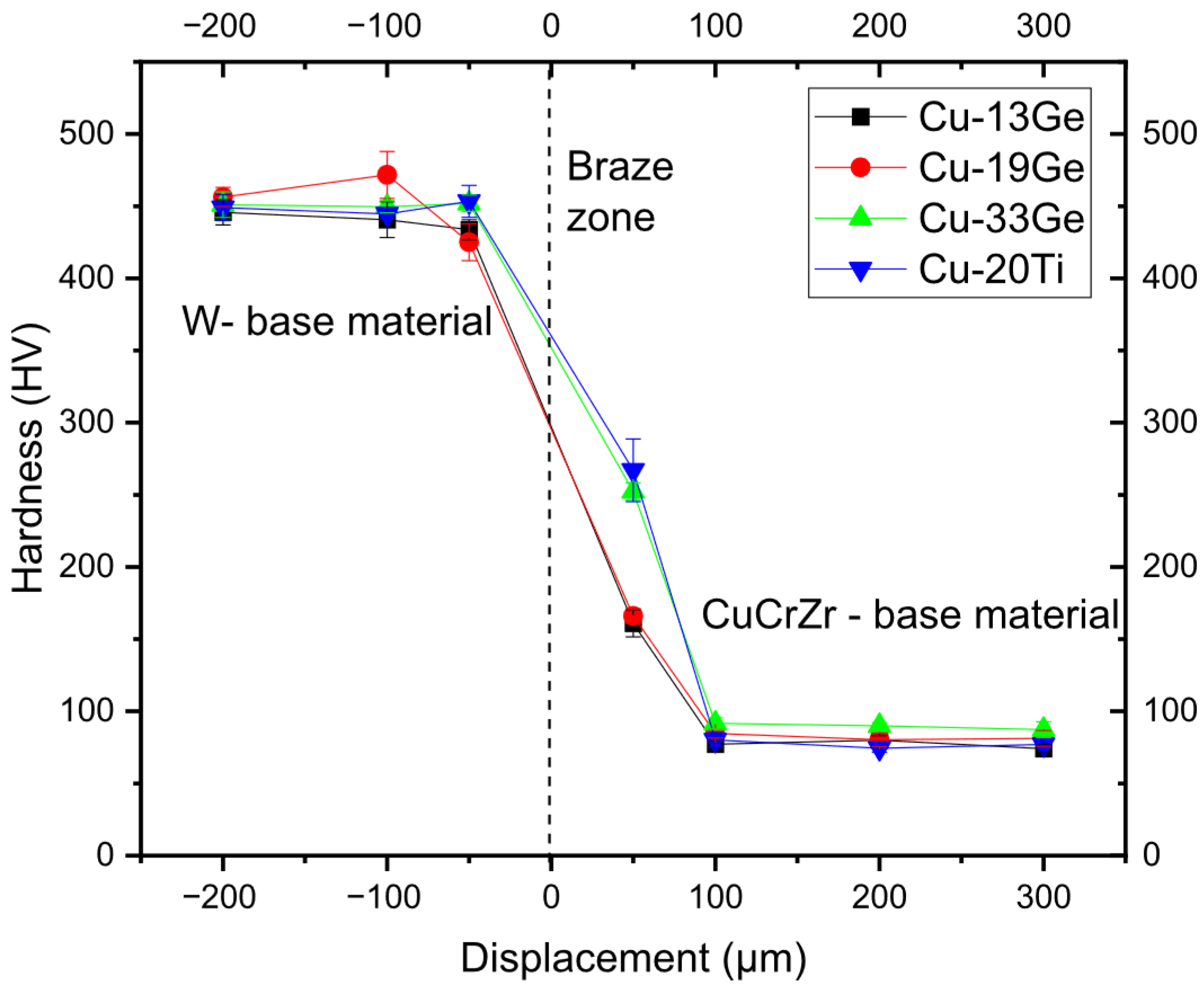

3.3. Mechanical Characterization of Brazed Joints

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Federici, G.; Biel, W.; Gilbert, M.R.; Kemp, R.; Taylor, N.; Wenninger, R. European DEMO design strategy and consequences for materials. Nucl. Fusion 2017, 57, 092002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richardson, M.; Gorley, M.; Wang, Y.; Aiello, G.; Pintsuk, G.; Gaganidze, E.; Richou, M.; Henry, J.; Vila, R.; Rieth, M. Technology readiness assessment of materials for DEMO in-vessel applications. J. Nucl. Mater. 2021, 550, 152906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, C.; Xu, L.; Zong, L.; Shen, H.; Wei, S. Research status of tungsten-based plasma-facing materials: A review. Fusion Eng. Des. 2023, 190, 113487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shah, V.; van Maris, M.P.F.H.L.; van Dommelen, J.A.W.; Geers, M.G.D. Experimental investigation of the microstructural changes of tungsten monoblocks exposed to pulsed high heat loads. Nucl. Mater. Energy 2020, 22, 100716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- You, J.H.; Greuner, H.; Böswirth, B.; Hunger, K.; Roccella, S.; Roche, H. High-heat-flux performance limit of tungsten monoblock targets: Impact on the armor materials and implications for power exhaust capacity. Nucl. Mater. Energy 2022, 33, 101307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, J.; Zhang, H.; Wang, Y.; Richardson, M.; Liu, X.; Knowles, D.; Mostafavi, M. Correlation study on tensile properties of Cu, CuCrZr and W by small punch test and uniaxial tensile test. Fusion Eng. Des. 2022, 177, 113061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, H.; Saito, T.; Gao, Z.; Ogino, Y.; Kondo, S.; Kasada, R.; Noto, H.; Hishinuma, Y.; Matsuzaki, S. Feasibility study on mass-production of oxide dispersion strengthened Cu alloys for the divertor of DEMO fusion reactor. J. Nucl. Mater. 2024, 599, 155205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, P.; Ding, W.; Ji, J.; Song, Y.; Wang, P.; Peng, X.; Chen, Q.; Mao, X.; Qian, X.; Zhang, J. Heat transfer and thermo-mechanical analyses of W/CuCrZr monoblock divertor in subcooled flow boiling. Fusion Eng. Des. 2019, 144, 46–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, P.; Qian, X.; Mao, X.; Song, W.; Peng, X. Study on creep-fatigue of heat sink in W/CuCrZr divertor target based on a new approach to creep life. Nucl. Mater. Energy 2020, 25, 100846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Galloway, A.; Wood, J.; Robbie, M.B.O.; Easton, D.; Zhu, W. Interfacial metallurgy study of brazed joints between tungsten and fusion related materials for divertor design. J. Nucl. Mater. 2014, 454, 207–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, D.; Lv, J.; Liu, Z.; Liu, L.; Wei, Y.; Chang, C.; Zhou, W.; Zhang, Y.; Han, C. Interface Optimization, Microstructural Characterization, and Mechanical Performance of CuCrZr/GH4169 Multi-Material Structures Manufactured via LPBF-LDED Integrated Additive Manufacturing. Materials 2025, 18, 2206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhai, W.; Li, G.; Zhou, W. Evaluation of Laser Powder Bed Fusion-Fabricated 316L/CuCrZr Bimetal Joint. Materials 2025, 18, 1434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, W.; Kousaka, T.; Moriya, S.; Kimura, T.; Nakamoto, T.; Nomura, N. Fabrication of a strong and ductile CuCrZr alloy using laser powder bed fusion. Addit. Manuf. Lett. 2023, 5, 100121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuai, Z.; Li, Z.; Liu, B.; Chen, Y.; Li, H.; Bai, P. Microstructure and mechanical properties of CuCrZr/316L hybrid components manufactured using selective laser melting. J. Alloys Compd. 2023, 955, 170103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Z.; Du, Z.; Yang, Z.; Yu, L.; Ma, Z. Preparation of Cu–Cr–Zr alloy by selective laser melting: Role of scanning parameters on densification, microstructure and mechanical properties. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 2022, 836, 142740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Chen, C.; Yi, R.; Ouyang, Y. Review: Special brazing and soldering. J. Manuf. Process. 2020, 60, 608–635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, L.; Mao, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Xi, L.; Deng, Q.; Wang, G. Microstructural and mechanical characterizations of W/CuCrZr and W/steel joints brazed with Cu-22TiH2 filler. J. Mater. Process. Technol. 2018, 254, 346–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, K.P.; Khirwadkar, S.S.; Bhope, K.; Patel, N.; Mokaria, P. Feasibility study on joining of multi-layered W/Cu-CuCrZr-SS316L-SS316L materials using vacuum brazing. Fusion Eng. Des. 2018, 127, 73–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Prado, J.; Sánchez, M.; Swan, D.; Ureña, A. Microstructural and mechanical characterization of W-CuCrZr joints brazed with Cu-Ti filler alloy. Metals 2021, 11, 202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Prado, J.; Sánchez, M.; Izaguirre, I.; Swan, D.; Ureña, A. Exploring Cu-Ge alloys as filler materials for high vacuum brazing application of W and CuCrZr. Mater. Today Commun. 2022, 33, 104286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, L.; Liu, Q.; Long, W.; Jia, G.; Yang, H.; Tang, Y. Microstructures and Mechanical Properties of V-Modified Ti-Zr-Cu-Ni Filler Metals. Materials 2023, 16, 199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, Y.; Li, J.; Wang, Z.; Lu, S.; Liu, K. Effect of Brazing Temperature and Holding Time on the Interfacial Microstructure and Properties of TC4-Brazed Joints with Ti-Zr-Cu-Ni Amorphous Filler. Materials 2025, 18, 2471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Canillas, F.; Leon-Gutierrez, E.; Roldan, M.; Hernandez, R.; Urionabarrenetxea, E.; Cardozo, E.; Portoles, L.; Blasco, J.; Ordas, N. On the feasibility to obtain CuCrZr alloys with outstanding thermal and mechanical properties by additive manufacturing. J. Nucl. Mater. 2024, 601, 155304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ordás, N.; Portolés, L.; Azpeleta, M.; Gómez, A.; Blasco, J.R.; Martinez, M.; Ureña, J.; Iturriza, I. Development of CuCrZr via Electron Beam Powder Bed Fusion (EB-PBF). J. Nucl. Mater. 2021, 548, 152841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adame, E.V.R.; Aleksa, A.; Gilbert, M.R.; Cuddy, M.; Calvet, T.; Vizvary, Z.; Mantel, N.; Maviglia, F.; You, J.H. Qualification & testing of joining development for DEMO limiter component. Fusion Eng. Des. 2022, 180, 113164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, D.; Wang, P.; Song, Y.; Li, Q.; Chen, J. Effect of the ITER FW Manufacturing Process on the Microstructure and Properties of a CuCrZr Alloy. Plasma Sci. Technol. 2015, 17, 887–892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kulczyk, M.; Pachla, W.; Godek, J.; Smalc-Koziorowska, J.; Skiba, J.; Przybysz, S.; Wróblewska, M.; Przybysz, M. Improved compromise between the electrical conductivity and hardness of the thermo-mechanically treated CuCrZr alloy. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 2018, 724, 45–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okamoto, H.; Schlesinger, M.E.; Mueller, E.M. (Eds.) ASM Handbook Volume 3: Alloy Phase Diagrams; ASM International: Materials Park, OH, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Pintsuk, G.; Blumm, J.; Hohenauer, W.; Hula, R.C.; Koppitz, T.; Lindig, S.; Pitzer, D.; Rohde, M.; Schoderböck, P.; Schubert, T.; et al. Interlaboratory test on thermophysical properties of the ITER grade heat sink material copper-chromium-zirconium. Int. J. Thermophys. 2010, 31, 2147–2158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Zhang, J.; Zhang, M.; Wang, K.; Zhang, A.; Xiao, A.; Mao, C. Finite element analysis and experimental verification of residual stress in brazed diamond with Ni-Cr filler alloy. Diam. Relat. Mater. 2023, 139, 110350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yi, R.; Chen, C.; Shi, C.; Li, Y.; Li, H.; Ma, Y. Research advances in residual thermal stress of ceramic/metal brazes. Ceram. Int. 2021, 47, 20807–20820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, S.; Sun, L.; Fang, J.; Zheng, Z.; Zhang, J.; Wen, Y.; Shan, T.; Liu, C. Residual stress, microstructure and corrosion behavior in the 316L/Si3N4 joint by multi-layered braze structure-experiments and simulation. Ceram. Int. 2022, 48, 32894–32907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aldazabal, J.; García-Rosales, C.; Meizoso, A.M.; Ordás, N.; Sordo, F.; Martínez, J.; Gil Sevillano, J. A comparison of the structure and mechanical properties of commercially pure tungsten rolled plates for the target of the European spallation source. Int. J. Refract. Met. Hard Mater. 2018, 70, 45–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lemetais, M.; Lenci, M.; Maurice, C.; Devictor, T.; Durif, A.; Minissale, M.; Mondon, M.; Pintsuk, G.; Piot, D.; Gallais, L.; et al. Temperature gradient based annealing methodology for tungsten recrystallization kinetics assessment. Fusion Eng. Des. 2023, 193, 113785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, C.; Li, F.; Chen, Y.; Huang, Y.; Wang, Z. Joining of oxygen-free high-conductivity Cu to CuCrZr by direct diffusion bonding without using an interlayer at Low temperature. Fusion Eng. Des. 2020, 151, 111400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wallis, C.; Buchmayr, B. Effect of heat treatments on microstructure and properties of CuCrZr produced by laser-powder bed fusion. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 2019, 744, 215–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Izaguirre, I. Desarrollo de Uniones W-EUROFER y W-CuCrZr Mediante Soldadura Fuerte para Aplicaciones de Alta Temperatura en Reactores de Fusion. Ph.D. Thesis, Universidad Rey Juan Carlos, Móstoles, Spain, 2024. [Google Scholar]

| Composition [wt.%] | Impurities [ppm] | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cu | Cr | Zr | Fe | Si | Al | C | O |

| Bal. | 0.95 | 0.067 | 110 | 120 | <200 | 19 | 80 |

| Beam Current (mA) | 8.5 |

| Scanning Speed (mm/s) | 170 |

| Line offset (mm) | 0.15 |

| Focus offset (mA) | 22 |

| Layer thickness (µm) | 70 |

| Rotation angle between layers (°) | 90 |

| Powder bed temperature (°C) | >380 |

| Sample | Brazing Temperature (°C) |

|---|---|

| Cu13Ge | 1030 |

| Cu19Ge | 900 |

| Cu33Ge | 775 |

| Cu20Ti | 960 |

| Brazing | Solution Annealing (Quenching) | Aging (Air Cooling) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sample | T (°C) | t (min) | T (°C) | t (min) | T (°C) | t (min) |

| Cu13Ge | 1030 | 10 | 900 | 30–60 | 450–500 | 15-60-120-180 |

| Cu19Ge | 900 | 10 | 775 | 60–120 | 450–500 | 15-60-120-180 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Izaguirre, I.; de Prado, J.; Ordás, N.; Sánchez, M.; Ureña, A. Brazeability Study of an Additively Manufactured CuCrZr Alloy to Tungsten Using Various Cu-Based Fillers. Materials 2025, 18, 5577. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma18245577

Izaguirre I, de Prado J, Ordás N, Sánchez M, Ureña A. Brazeability Study of an Additively Manufactured CuCrZr Alloy to Tungsten Using Various Cu-Based Fillers. Materials. 2025; 18(24):5577. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma18245577

Chicago/Turabian StyleIzaguirre, Ignacio, Javier de Prado, Nerea Ordás, María Sánchez, and Alejandro Ureña. 2025. "Brazeability Study of an Additively Manufactured CuCrZr Alloy to Tungsten Using Various Cu-Based Fillers" Materials 18, no. 24: 5577. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma18245577

APA StyleIzaguirre, I., de Prado, J., Ordás, N., Sánchez, M., & Ureña, A. (2025). Brazeability Study of an Additively Manufactured CuCrZr Alloy to Tungsten Using Various Cu-Based Fillers. Materials, 18(24), 5577. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma18245577