Mechanical Properties and Fracture Behavior of Hot Isostatically Pressed TiC/TC4 Composites

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results and Discussion

4. Conclusions

- (1)

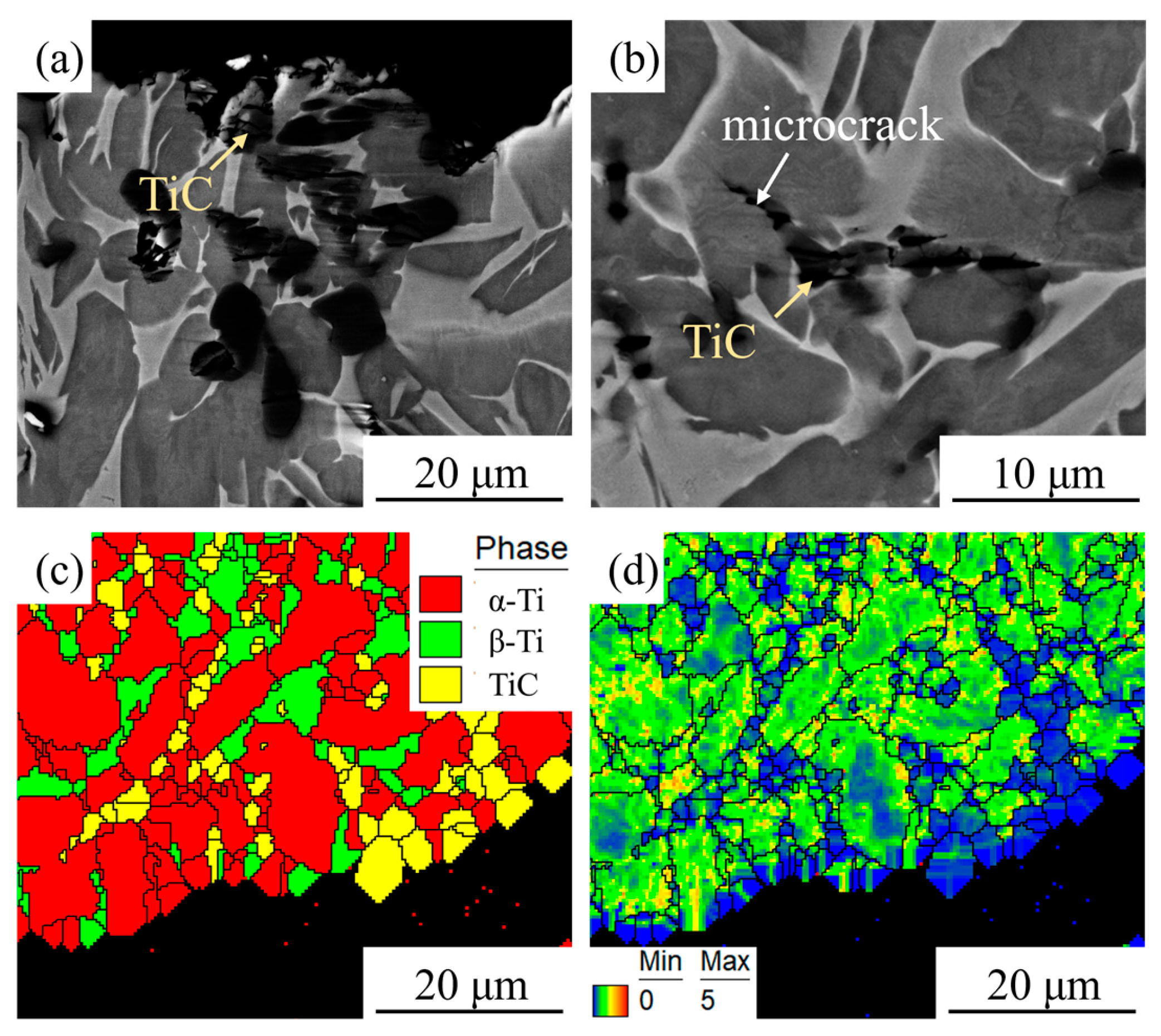

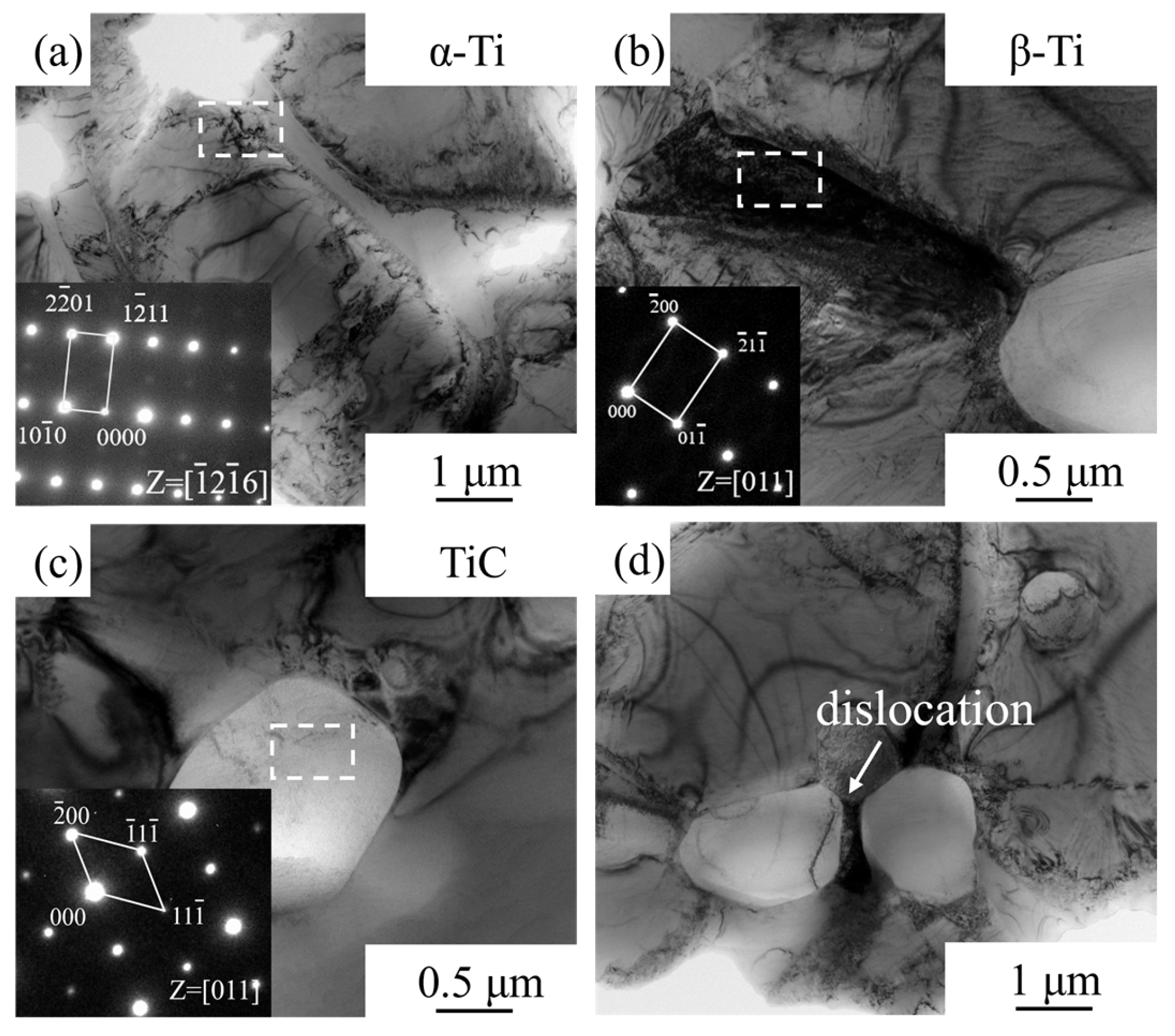

- The HIPed TiC/TC4 composite exhibited a typical equiaxed α+β dual-phase matrix microstructure. The TiC reinforcement particles were primarily distributed at grain boundaries, with fine TiC particles also uniformly precipitated within the grains. The tensile strength of the composite was comparable to previously reported titanium matrix composites, but its total elongation was significantly increased to 17.0 ± 0.5%. The fine matrix grains and uniformly distributed TiC particles were identified as the primary reasons for this high ductility.

- (2)

- During room-temperature tensile deformation, the high-strength but non-plastic TiC particles readily caused dislocation pile-ups, leading to interfacial stress concentration and the initiation of microcracks, which ultimately resulted in material fracture. The predominant strengthening mechanism provided by the TiC particles at room temperature was load-transfer strengthening.

- (3)

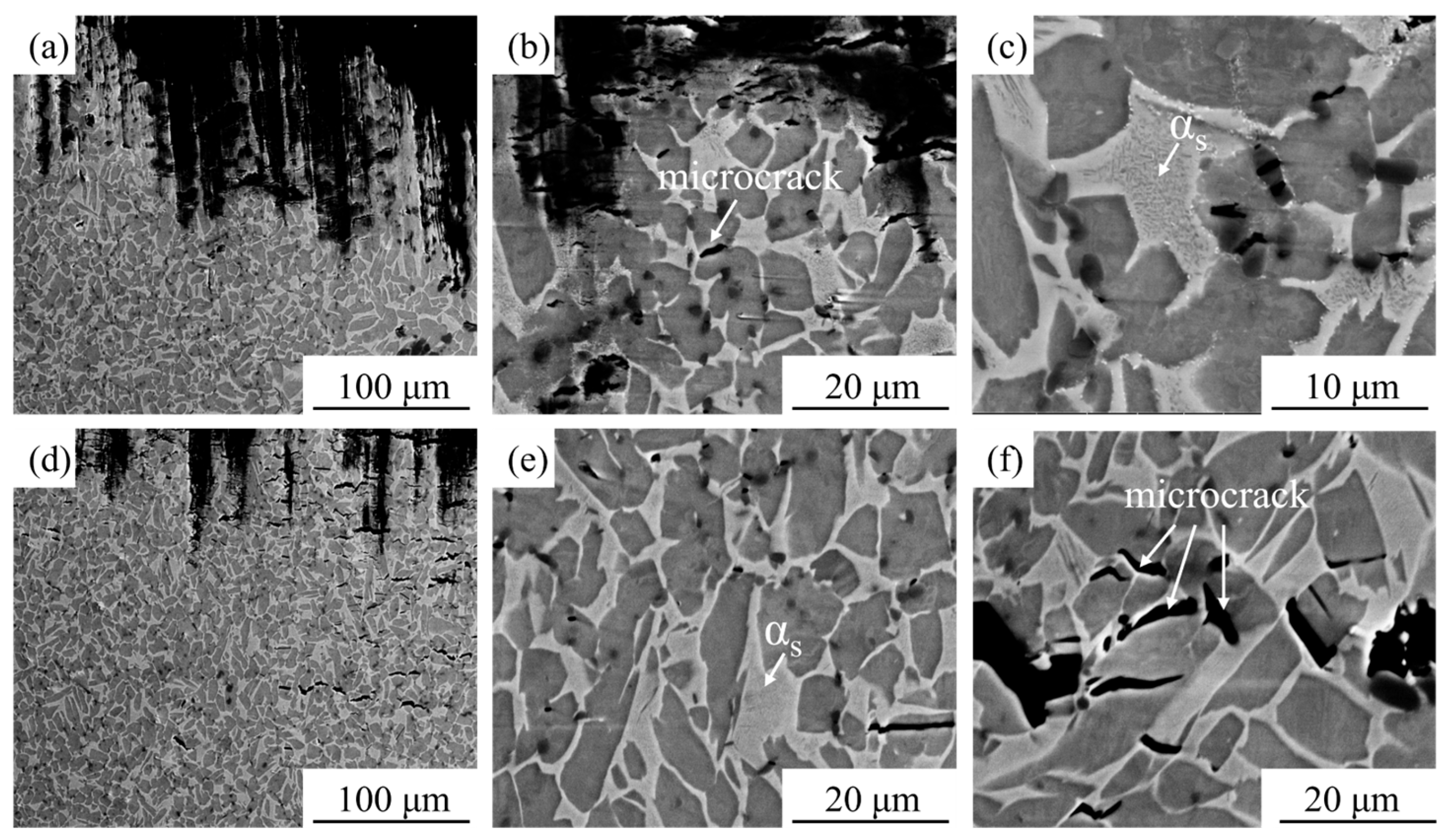

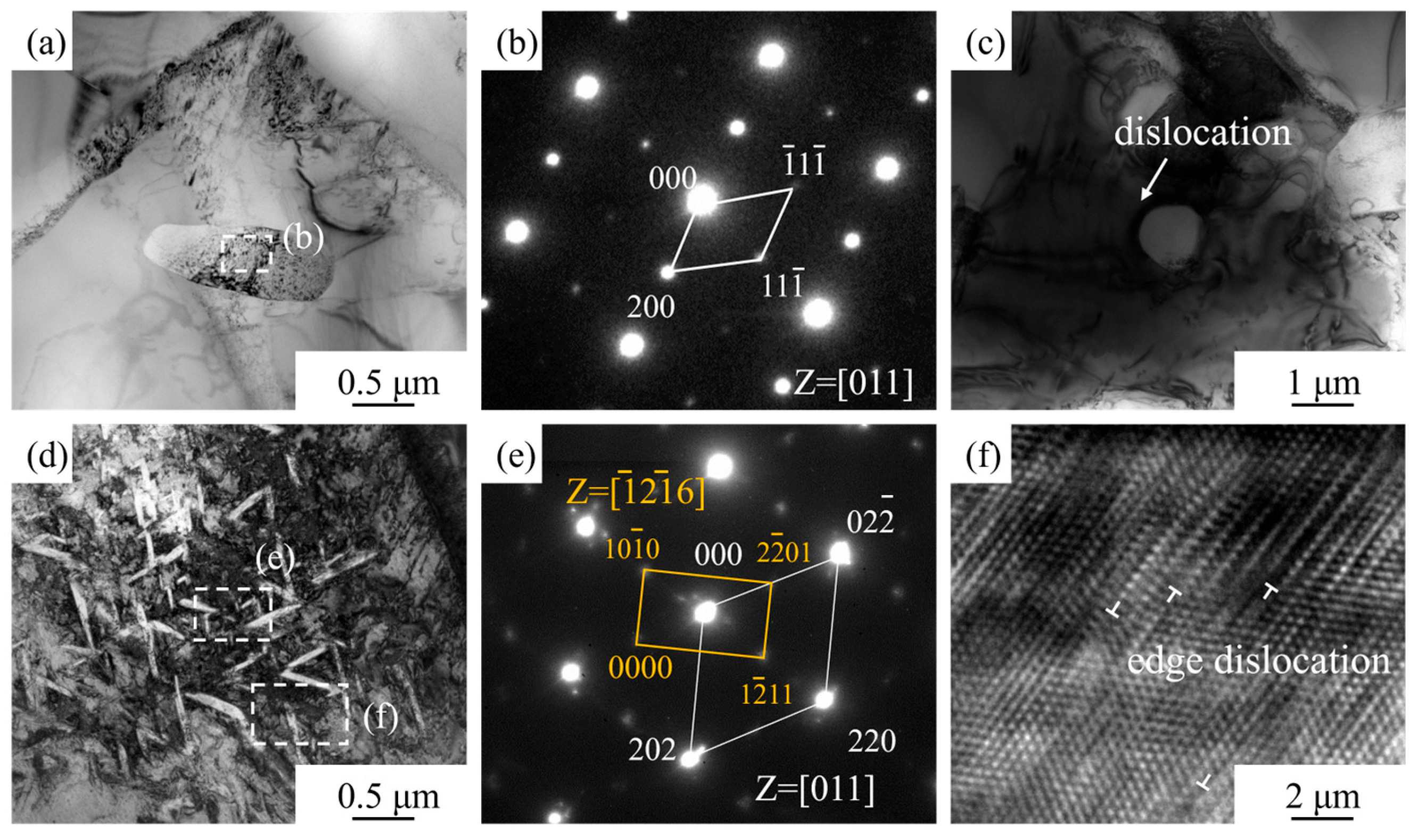

- At elevated temperatures, the strength of the matrix decreased, leading to the extensive initiation of microcracks within the matrix, which became the dominant fracture mechanism. At 600 °C, the composite exhibited predominantly ductile fracture, while a mixed ductile-brittle failure mode emerged at 650 °C. The TiC particles exhibited deformation compatibility at high temperatures, resulting in a diminished particle strengthening effect. Concurrently, nano-acicular αs phases precipitated from the β phase under high-temperature deformation, providing a precipitation strengthening effect.

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Hayat, M.D.; Singh, H.; He, Z.; Cao, P. Titanium metal matrix composites: An overview. Compos. Part A 2019, 121, 418–438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miracle, D.B. Metal matrix composites—From science to technological significance. Compos. Sci. Technol. 2005, 65, 2526–2540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tjong, S.C.; Mai, Y.-W. Processing-structure-property aspects of particulate- and whisker-reinforced titanium matrix composites. Compos. Sci. Technol. 2008, 68, 583–601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, W.; Liu, M.; Zhang, W.; Yang, Y.; Wang, X.; Zhou, S.; Du, J. Microstructure and mechanical behaviour of TiCx-MLG-TiCx network reinforced Ti6Al4V fabricated with core-shell structure powders. J. Alloys Compd. 2022, 897, 163210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, J.; Tan, Y.C.; Janasekaran, S.; Tai, V.C.; Wang, D.; Yang, Y.; Fan, Y. Multi-objective optimization of laser powder bed fusion parameters for SiC/Ti composites using a BP neural network and NSGA-II. J. Mater. Res. Technol. 2025, 39, 1466–1479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rominiyi, A.L.; Mashinini, P.M. Spark plasma sintering of discontinuously reinforced titanium matrix composites: Densification, microstructure and mechanical properties—A review. Int. J. Adv. Manuf. Technol. 2023, 124, 709–736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiu, P.; Han, Y.; Huang, G.; Le, J.; Lei, L.; Xiao, L.; Lu, W. Texture Evolution and Dynamic Recrystallization Behavior of Hybrid-Reinforced Titanium Matrix Composites: Enhanced Strength and Ductility. Metall. Mater. Trans. A 2020, 51, 2276–2290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lv, S.; Li, J.S.; Li, S.F.; Kang, N.; Chen, B. Room-/High-Temperature Mechanical Properties of Titanium Matrix Composites Reinforced with Discontinuous Carbon Fibers. Adv. Eng. Mater. 2022, 24, 2101026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.L.; Zhou, Z.M.; Wang, J.L.; Li, X.Y. Diamond Tool Wear in Precision Turning of Titanium Alloy. Mater. Manuf. Process. 2013, 28, 1061–1064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matuszak, J.; Zaleski, K.; Zyśko, A. Investigation of the Impact of High-Speed Machining in the Milling Process of Titanium Alloy on Tool Wear, Surface Layer Properties, and Fatigue Life of the Machined Object. Materials 2023, 16, 5361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, M.; Han, Y.; Shi, Z.; Huang, G.; Song, J.; Lu, W. Embedding boron into Ti powder for direct laser deposited titanium matrix composite: Microstructure evolution and the role of nano-TiB network structure. Compos. Part B 2021, 211, 108683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.; Zou, D.; Mazur, M.; Mo, J.P.T.; Li, G.; Ding, S. The State of the Art in Machining Additively Manufactured Titanium Alloy Ti-6Al-4V. Materials 2023, 16, 2583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, S.L.; Li, S.F.; Liu, H.Y.; Liu, L.; Pan, D.; Li, G.; Wang, Z.M.; Hou, X.D.; Gao, J.B.; Zhang, X.; et al. Achieving back-stress strengthening at high temperature via heterogeneous distribution of nano TiBw in titanium alloy by electron beam powder bed fusion. Mater. Charact. 2024, 215, 114132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, M.; Zhang, L.; Zhang, N. Microstructural evolution, mechanical and tribological properties of TiC/Ti6Al4V composites with unique microstructure prepared by SLM. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 2021, 814, 141187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, L.; Li, X.; Sun, G.; Xu, J.; Li, M.; Tang, Y.; Fu, Y.; Elmarakbi, A.; Cui, W.; Zhou, L.; et al. Constructing micro-network of Ti2Cu and in-situ formed TiC phases in titanium composites as new strategy for significantly enhancing strength. Compos. Commun. 2024, 45, 101787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, Z.; Wang, X.D.; Li, J.L.; Wu, Y.; Zhang, H.P.; Guo, J.Q.; Wang, S.Q. Reinforcement with graphene nanoflakes in titanium matrix composites. J. Alloys Compd. 2017, 696, 498–502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, W.D.; Ning, J.G.; Jiang, F.; Mao, X.N. Microstructural and mechanical characterization of TP-650 titanium matrix composites. Lat. Am. J. Solids Struct. 2009, 6, 1–11. [Google Scholar]

- Fruhauf, J.B.; Roger, J.; Dezellus, O.; Gourdet, S.; Karnatak, N.; Peillon, N.; Saunier, S.; Montheillet, F.; Desrayaud, C. Microstructural and mechanical comparison of Ti+15%TiCp composites prepared by free sintering, HIP and extrusion. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 2012, 554, 22–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ASTM E8; Standard Test Methods for Tension Testing of Metallic Materials. ASTM: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2022.

- Zheng, Y.; Xiong, R.; Zhao, Z.; Zhao, C.; Wang, Z.; Niu, W.; Xue, H.; Cheng, F.; Liu, W.; Wei, S. Laser melting deposition of in-situ (TiB+TiC) hybrid reinforced TC4 composites: Preparation, microstructure and room/high-temperature corrosion behaviour. J. Mater. Sci. Technol. 2025, 228, 137–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loretto, M.H.; Konitzer, D.G. The effect of matrix reinforcement reaction on fracture in Ti-6Ai-4V-base composites. Metall. Trans. A 1990, 21, 1579–1587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, Z.J.; Cao, L.; Wang, H.W.; Zou, C.M. Microstructure and mechanical properties of TiC/Ti-6Al-4V composites processed by in situ casting route. Mater. Sci. Technol. 2011, 27, 1321–1327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ya, B.; Zhou, B.; Yang, H.; Huang, B.; Jia, F.; Zhang, X. Microstructure and mechanical properties of in situ casting TiC/Ti6Al4V composites through adding multi-walled carbon nanotubes. J. Alloys Compd. 2015, 637, 456–460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Liu, X.; Xing, F.; Xu, G.; Bian, H.; Liu, W. Microstructure and mechanical properties of TiC/Ti6Al4V composite fabricated by concurrent wire-powder feeding laser-directed energy deposition. Opt. Laser Technol. 2025, 181, 111836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, S.; Chai, C.; Guo, S.; Li, F.; Liu, Y.; Yi, J.; Yu, J.; Eckert, J. Laser directed energy deposition of heteroarchitected Ti6Al4V composites: In-situ TiB/TiC network engineering for multi-mechanistic strength-ductility synergy. J. Mater. Res. Technol. 2025, 37, 5187–5202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, B.; Zhang, F.; Saba, F.; Shang, C. Graphene-TiC hybrid reinforced titanium matrix composites with 3D network architecture: Fabrication, microstructure and mechanical properties. J. Alloys Compd. 2021, 859, 157777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, C.; He, S.; Li, L.; Teng, Q.; Song, B.; Yan, C.; Wei, Q.; Shi, Y. In-situ TiB/Ti-6Al-4V composites with a tailored architecture produced by hot isostatic pressing: Microstructure evolution, enhanced tensile properties and strengthening mechanisms. Compos. Part B 2019, 164, 546–558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gurson, A.L. Continuum Theory of Ductile Rupture by Void Nucleation and Growth: Part I—Yield Criteria and Flow Rules for Porous Ductile Media. J. Eng. Mater. Technol. 1977, 99, 2–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, T.; Yue, C.; Zheng, B.; Gu, F.; Zuo, X.; Dong, F.; Lin, X.; Wang, Y.; Huang, H.; Yuan, X. Achieving synergistic enhancement of strength and plasticity of (TiC+Ti5Si3)/TC4 composites by dual-scale near-network structure design. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 2025, 927, 148022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.; Dong, L.; Yang, Q.; Huo, W.; Fu, Y.; Yu, J.; Liu, Y.; Zhang, Y. Controlled Interfacial Reactions and Superior Mechanical Properties of High Energy Ball Milled/Spark Plasma Sintered Ti-6Al-4V-Graphene Composite. Adv. Eng. Mater. 2021, 23, 2001411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, T.M.; Huang, H.L.; Hosseini, S.R.E.; Chen, W.; Li, F.; Chen, C.; Zhou, K.C. Obtaining heterogeneous α laths in selective laser melted Ti-5Al-5Mo-5V-1Cr-1Fe alloy with high strength and ductility. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 2022, 835, 142624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Sun, Z.; Duan, J.; Wu, X.; Mo, X.; Nan, H.; Xu, J.; Fu, A.; Cao, Y.; Liu, B. Mechanical Properties and Fracture Behavior of Hot Isostatically Pressed TiC/TC4 Composites. Materials 2025, 18, 5529. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma18245529

Sun Z, Duan J, Wu X, Mo X, Nan H, Xu J, Fu A, Cao Y, Liu B. Mechanical Properties and Fracture Behavior of Hot Isostatically Pressed TiC/TC4 Composites. Materials. 2025; 18(24):5529. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma18245529

Chicago/Turabian StyleSun, Zhiyu, Jinyi Duan, Xiang Wu, Xiaofei Mo, Hai Nan, Jingchao Xu, Ao Fu, Yuankui Cao, and Bin Liu. 2025. "Mechanical Properties and Fracture Behavior of Hot Isostatically Pressed TiC/TC4 Composites" Materials 18, no. 24: 5529. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma18245529

APA StyleSun, Z., Duan, J., Wu, X., Mo, X., Nan, H., Xu, J., Fu, A., Cao, Y., & Liu, B. (2025). Mechanical Properties and Fracture Behavior of Hot Isostatically Pressed TiC/TC4 Composites. Materials, 18(24), 5529. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma18245529