The Double-K Fracture Toughness of Concrete with Different Coarse Aggregate Volume Fractions

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

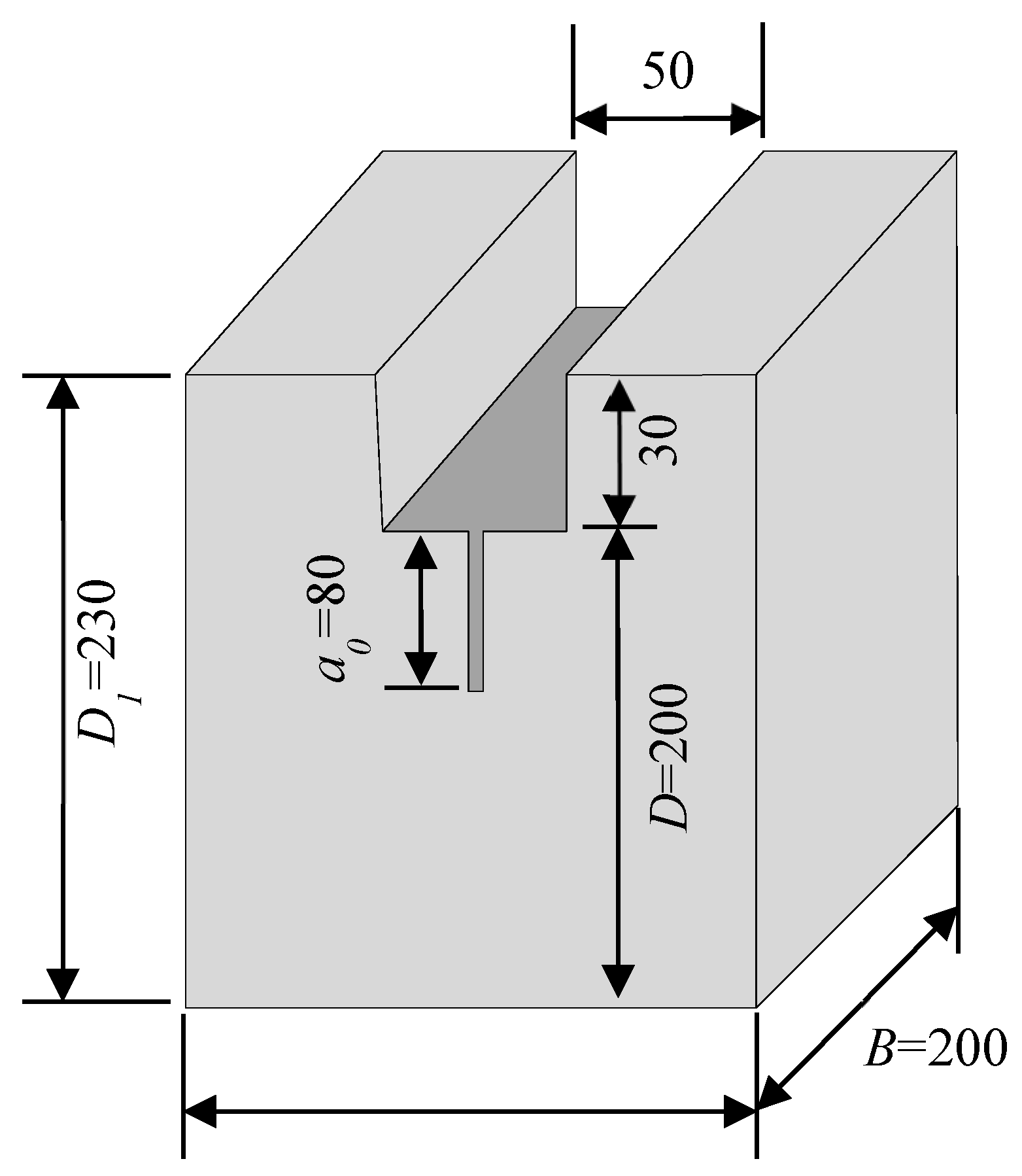

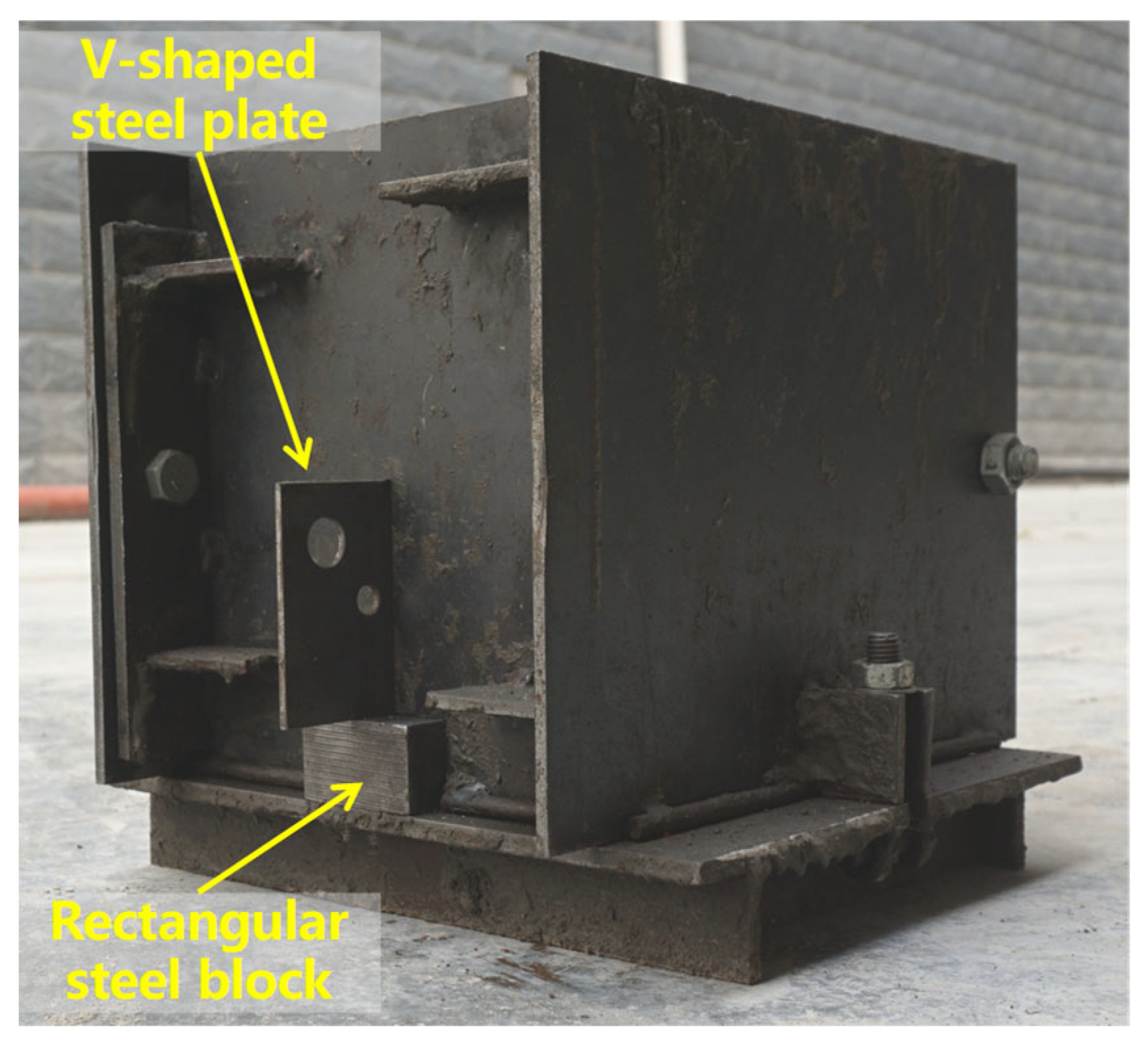

2.1. Specimen Preparation

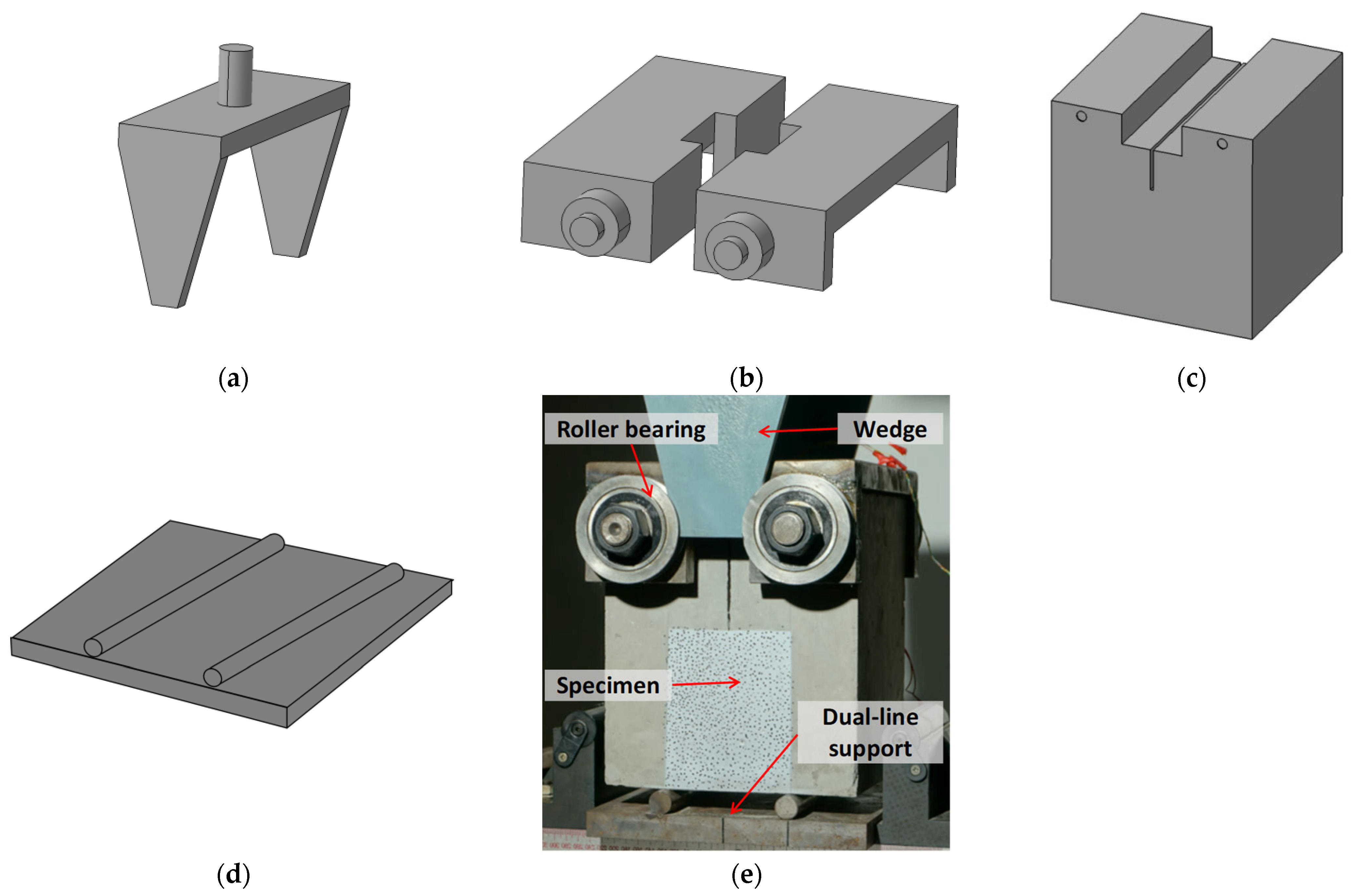

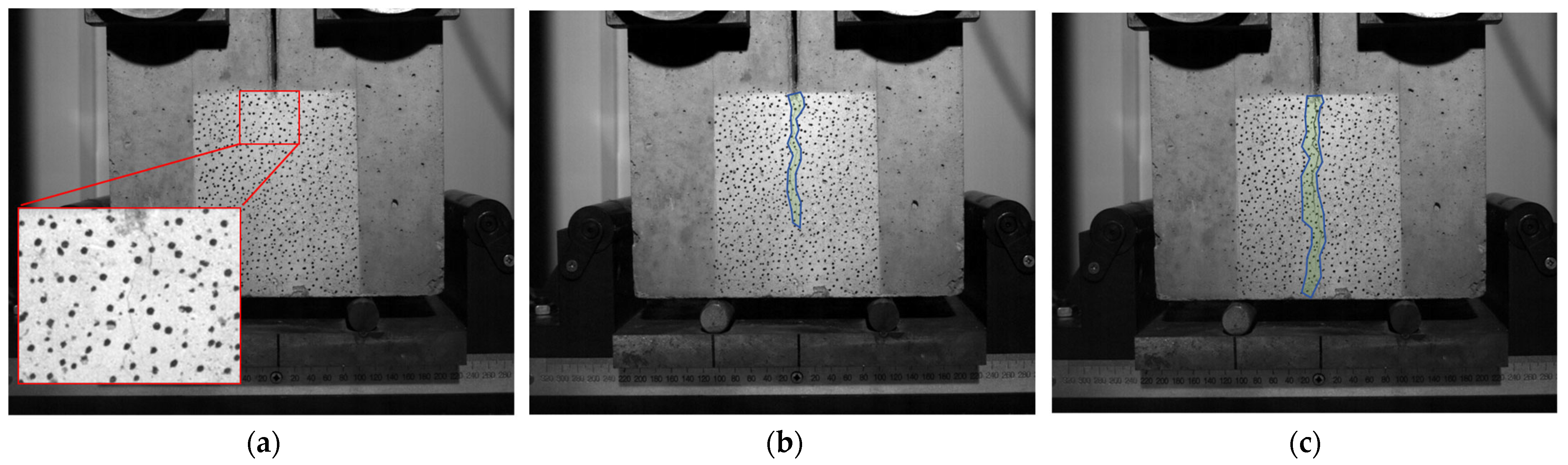

2.2. Test Method

2.3. Determination of Double-K Fracture Toughness

2.3.1. Unstable Toughness

2.3.2. Initiation Toughness

2.3.3. Fracture Energy

2.3.4. Characteristic Length

3. Results and Discussion

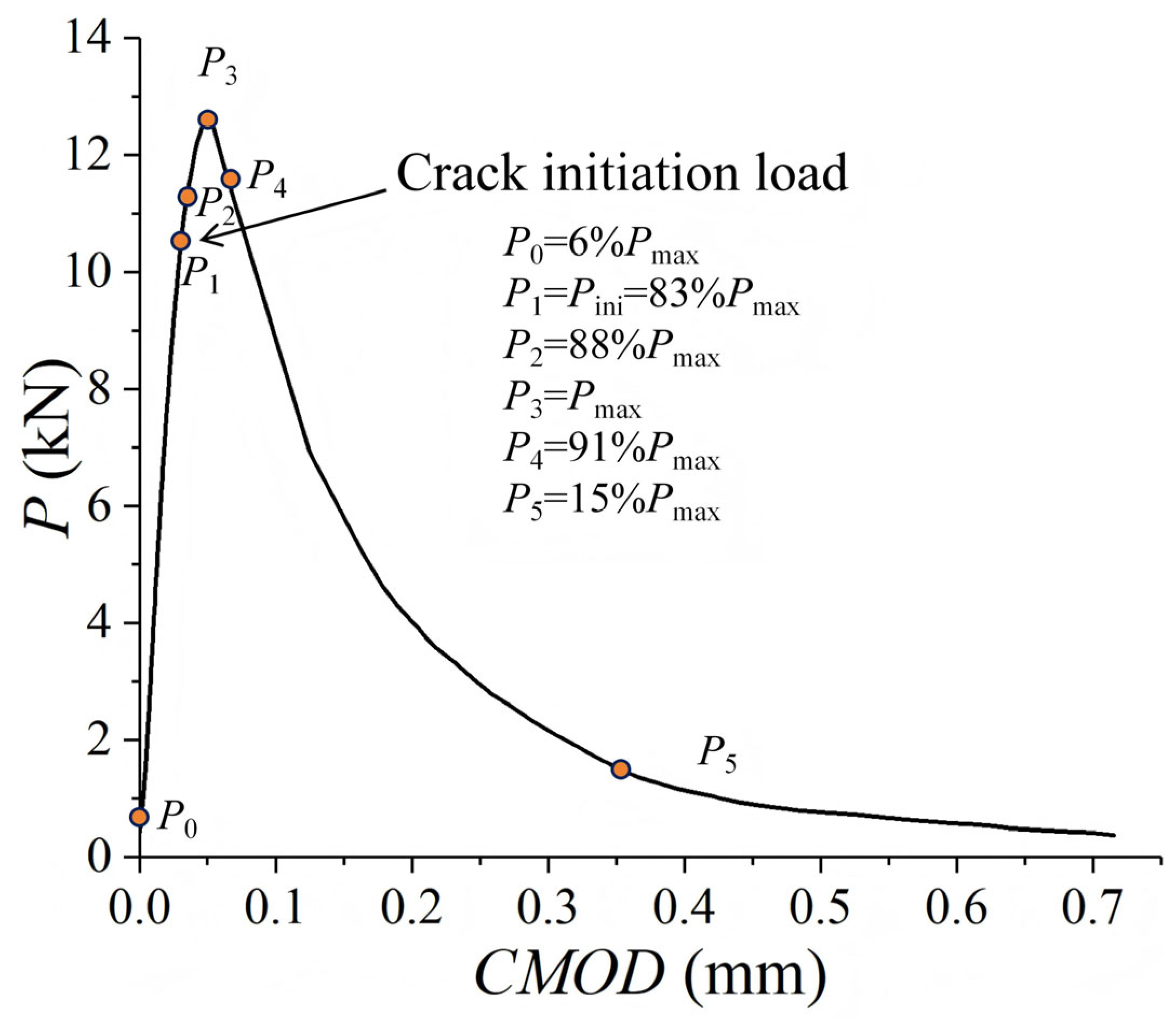

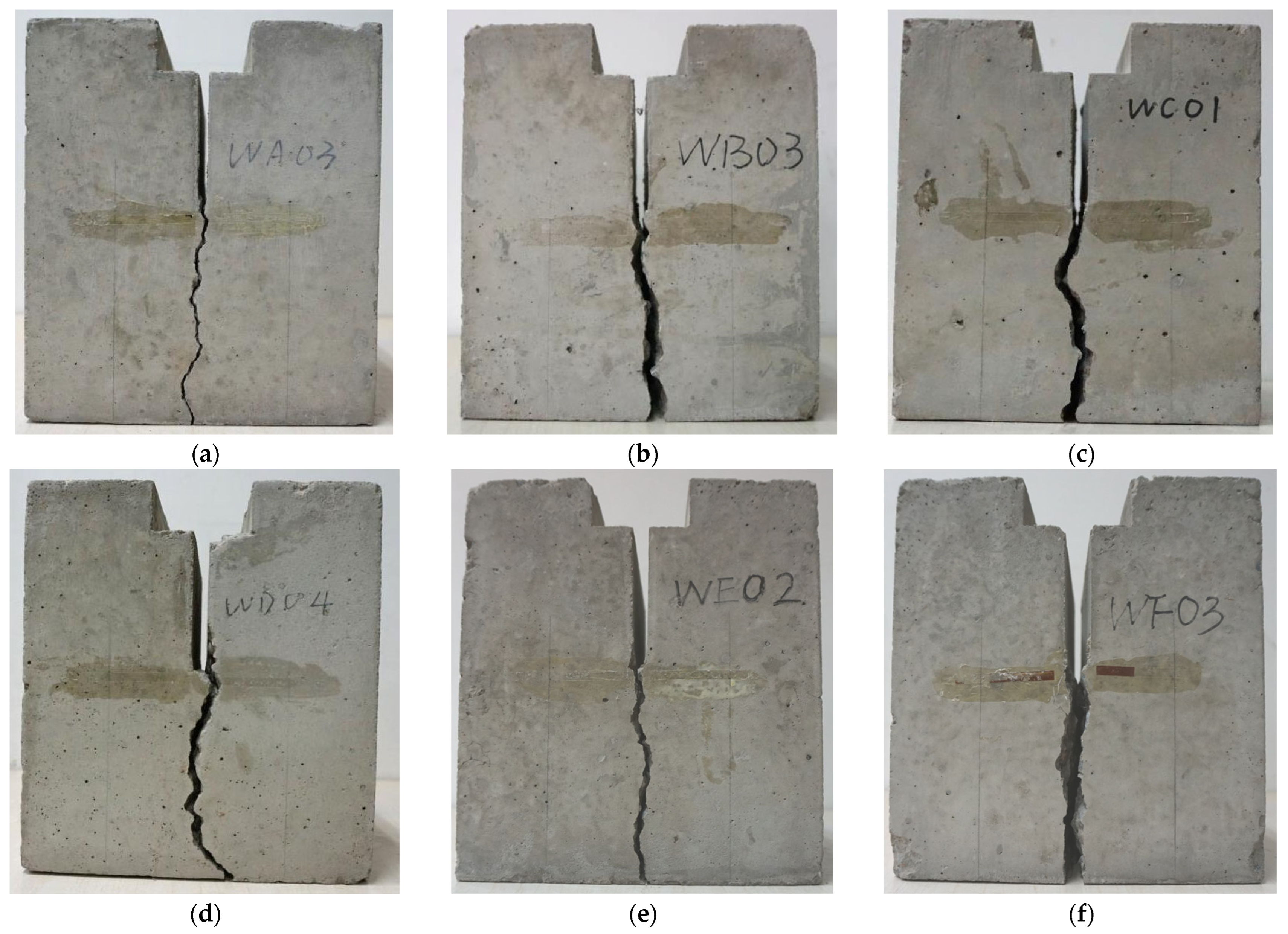

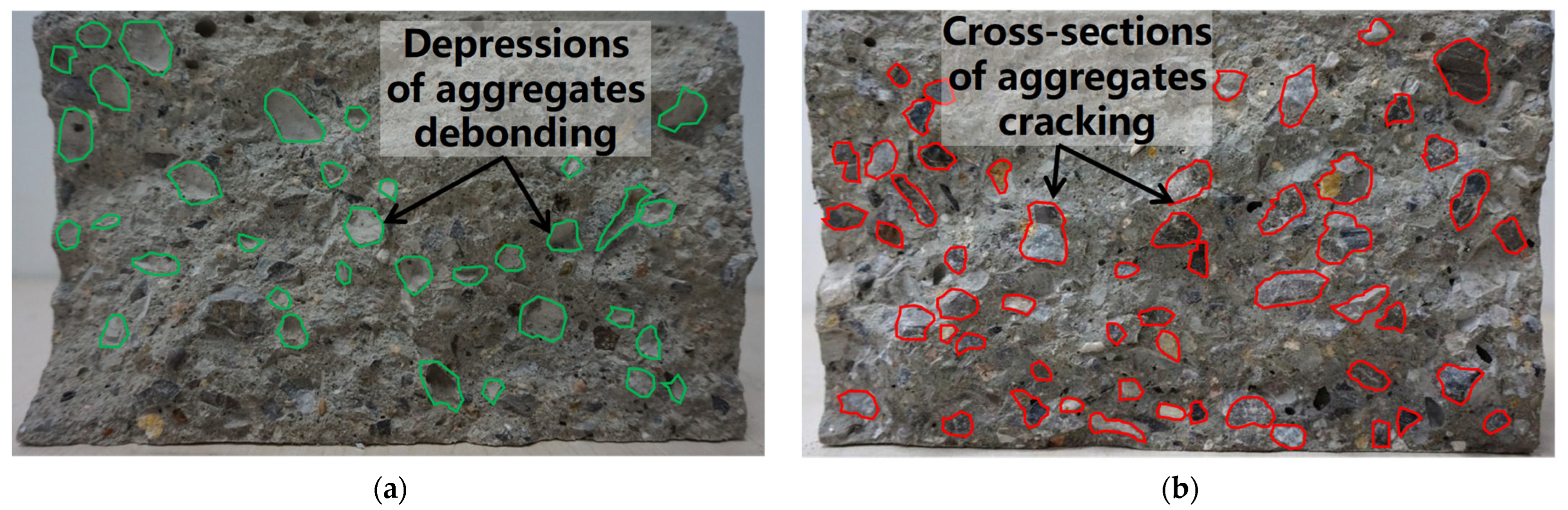

3.1. Fracture Behaviors

- Stage I: From the start of loading to the initial cracking load Pini

- Stage II: From Pini to Pmax, representing the stable crack propagation

- Stage III: Post-peak softening stage, representing the unstable fracture

3.2. Mechanical and Fracture Parameters

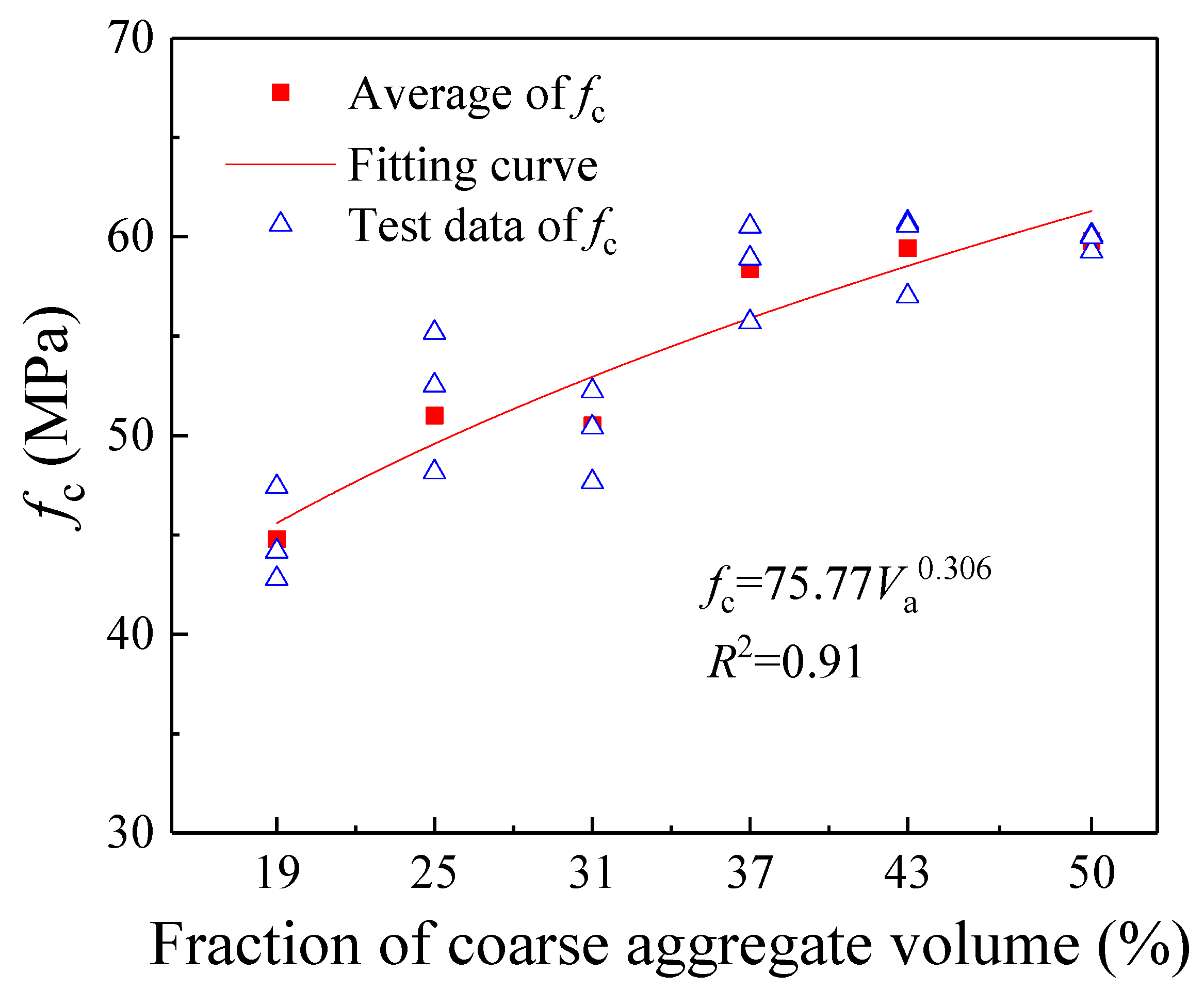

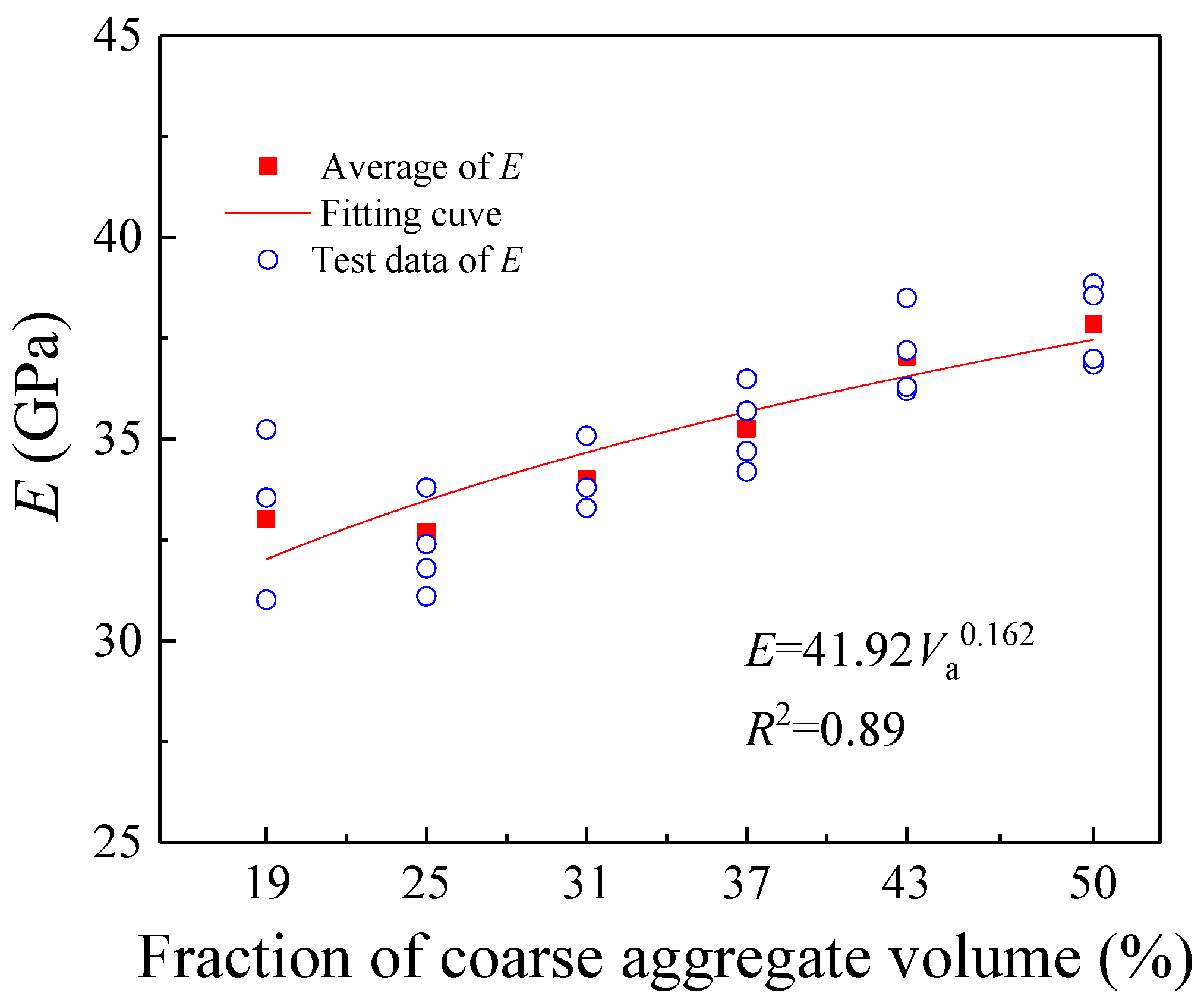

3.2.1. Compressive Strength and Elastic Modulus

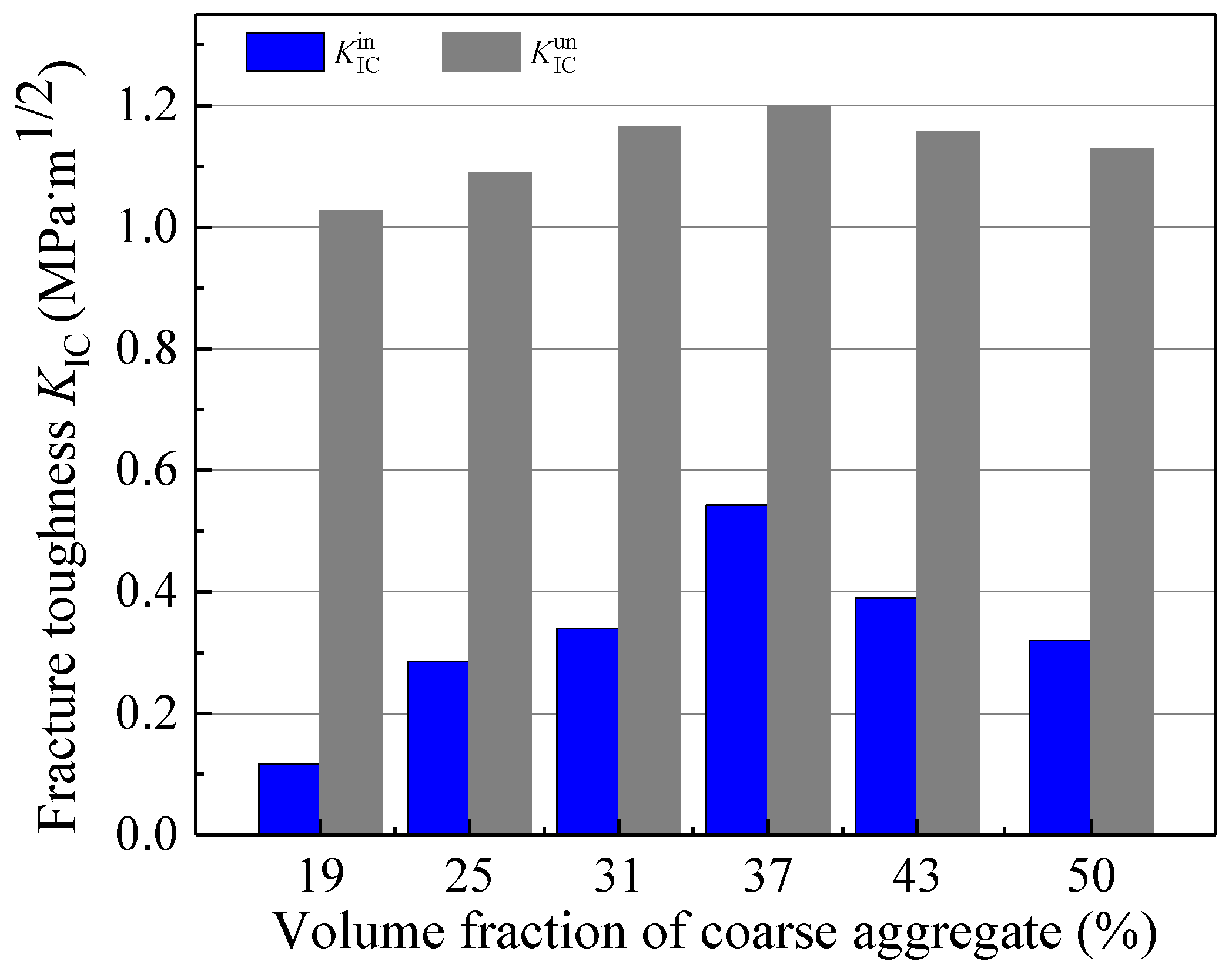

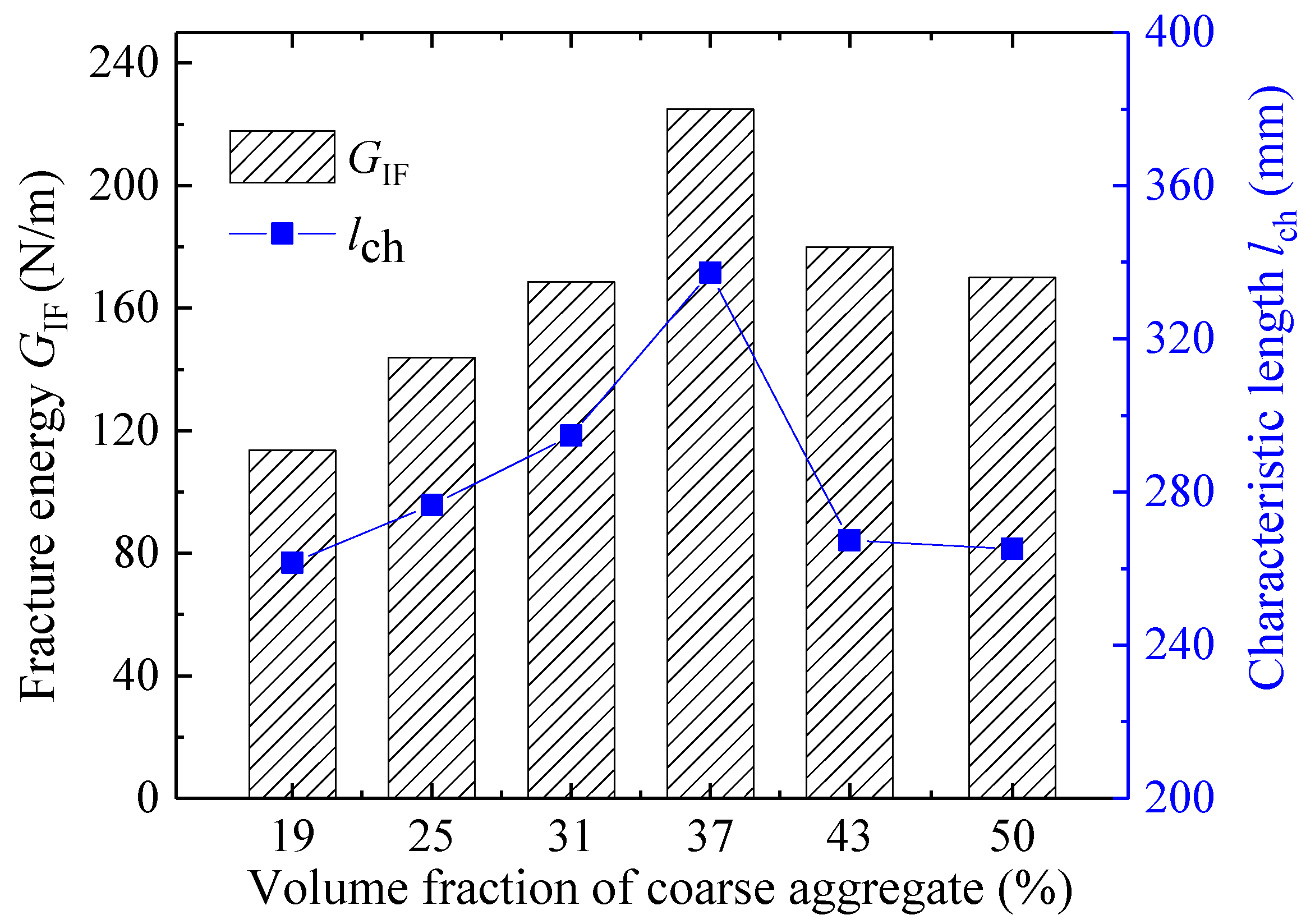

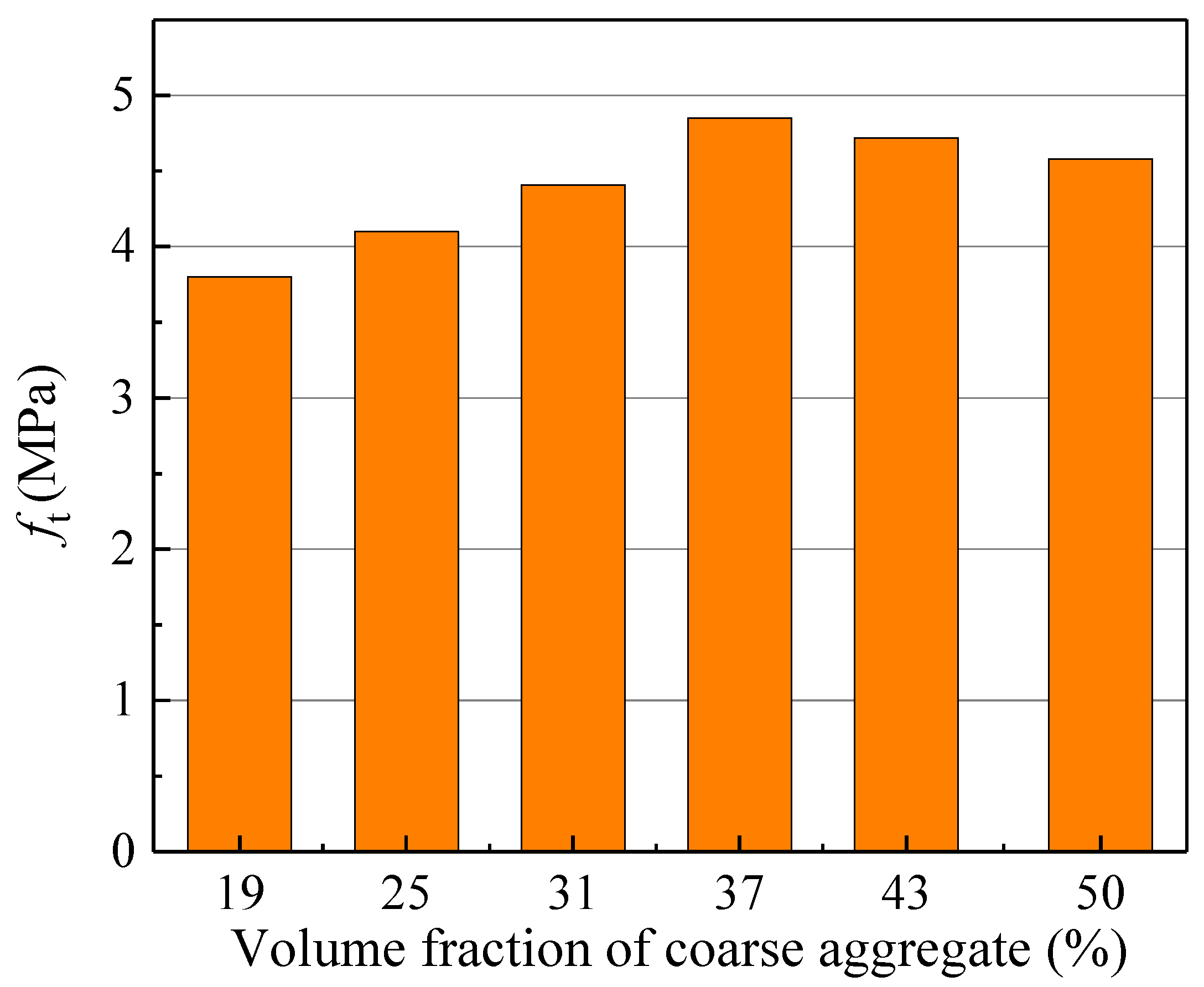

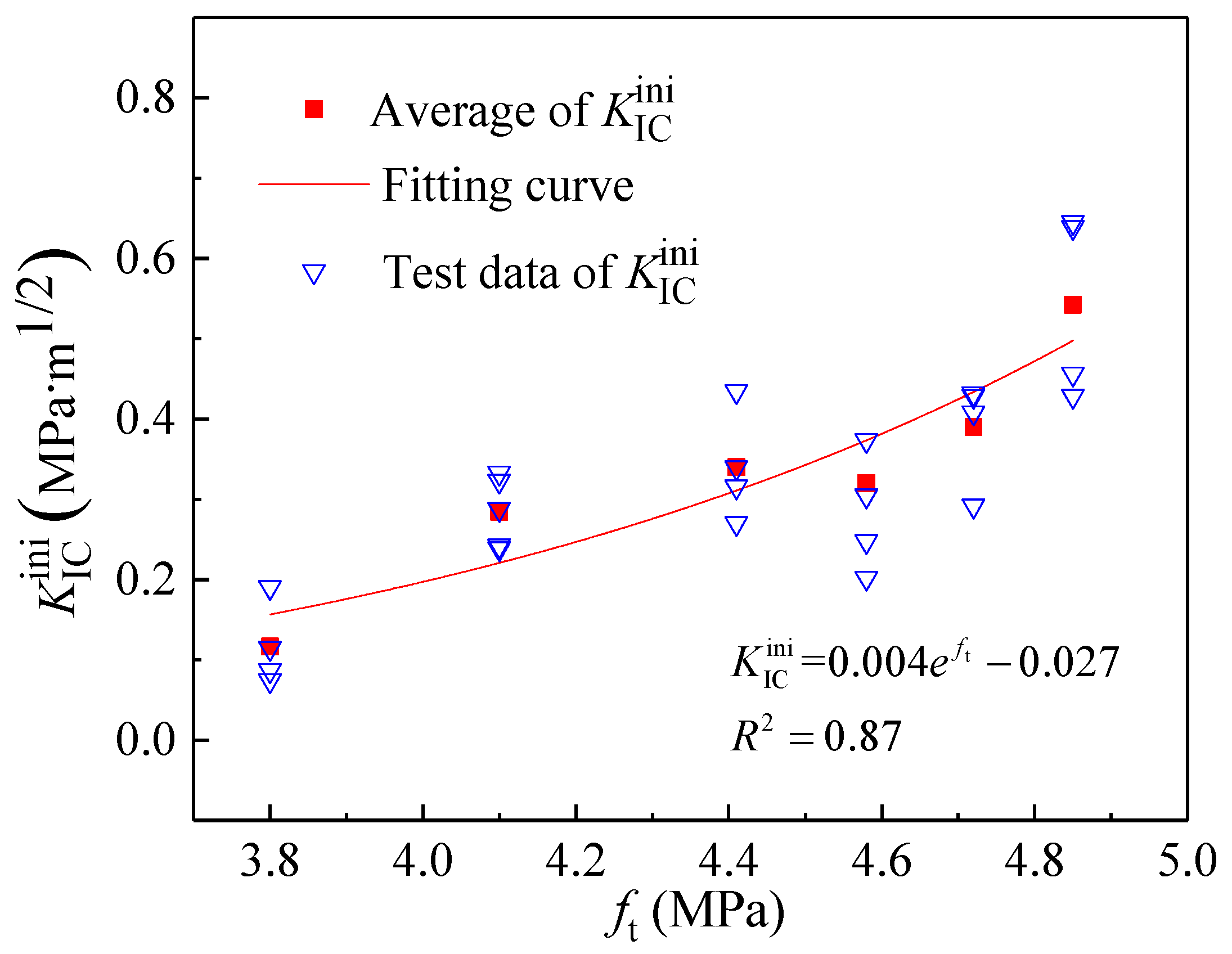

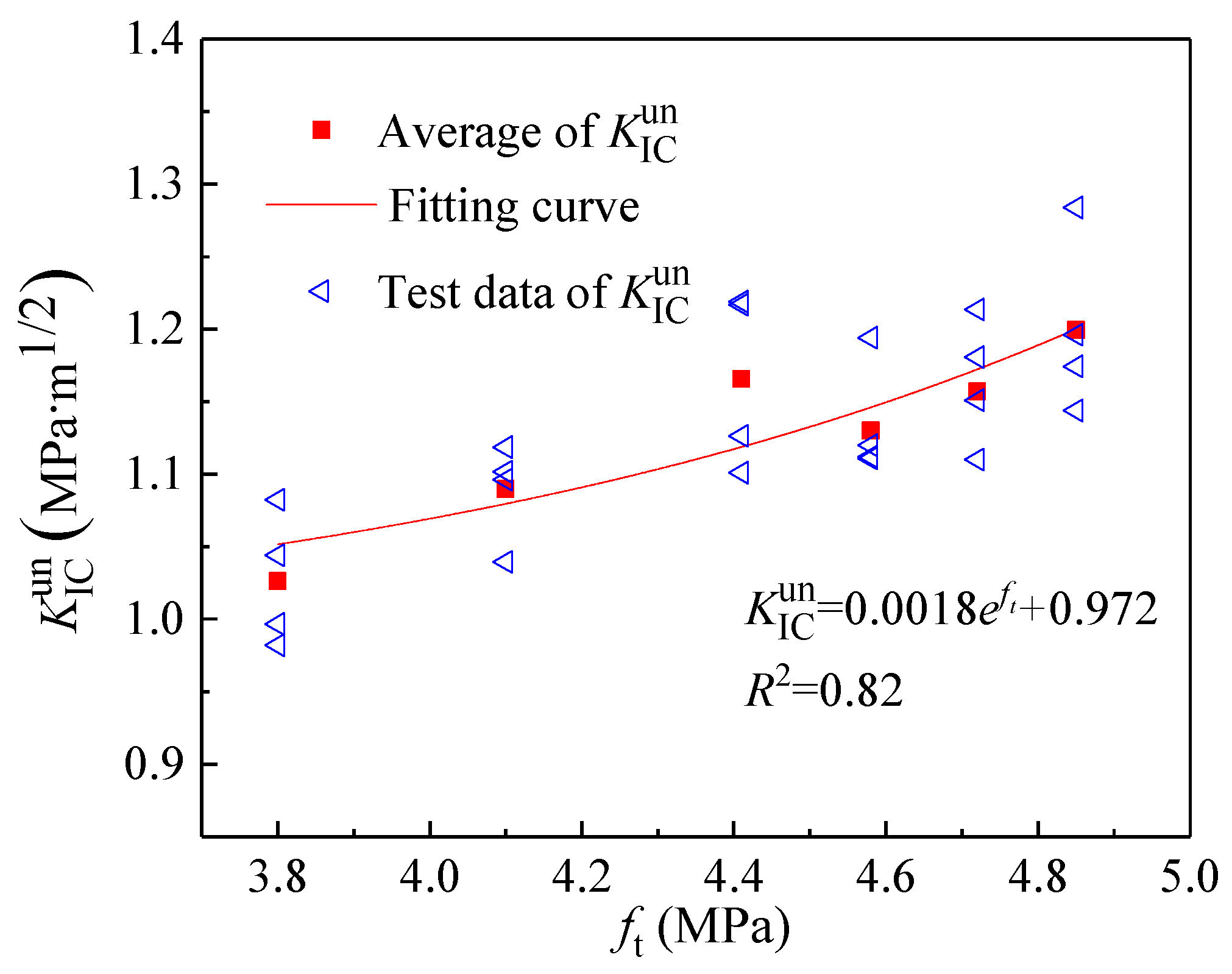

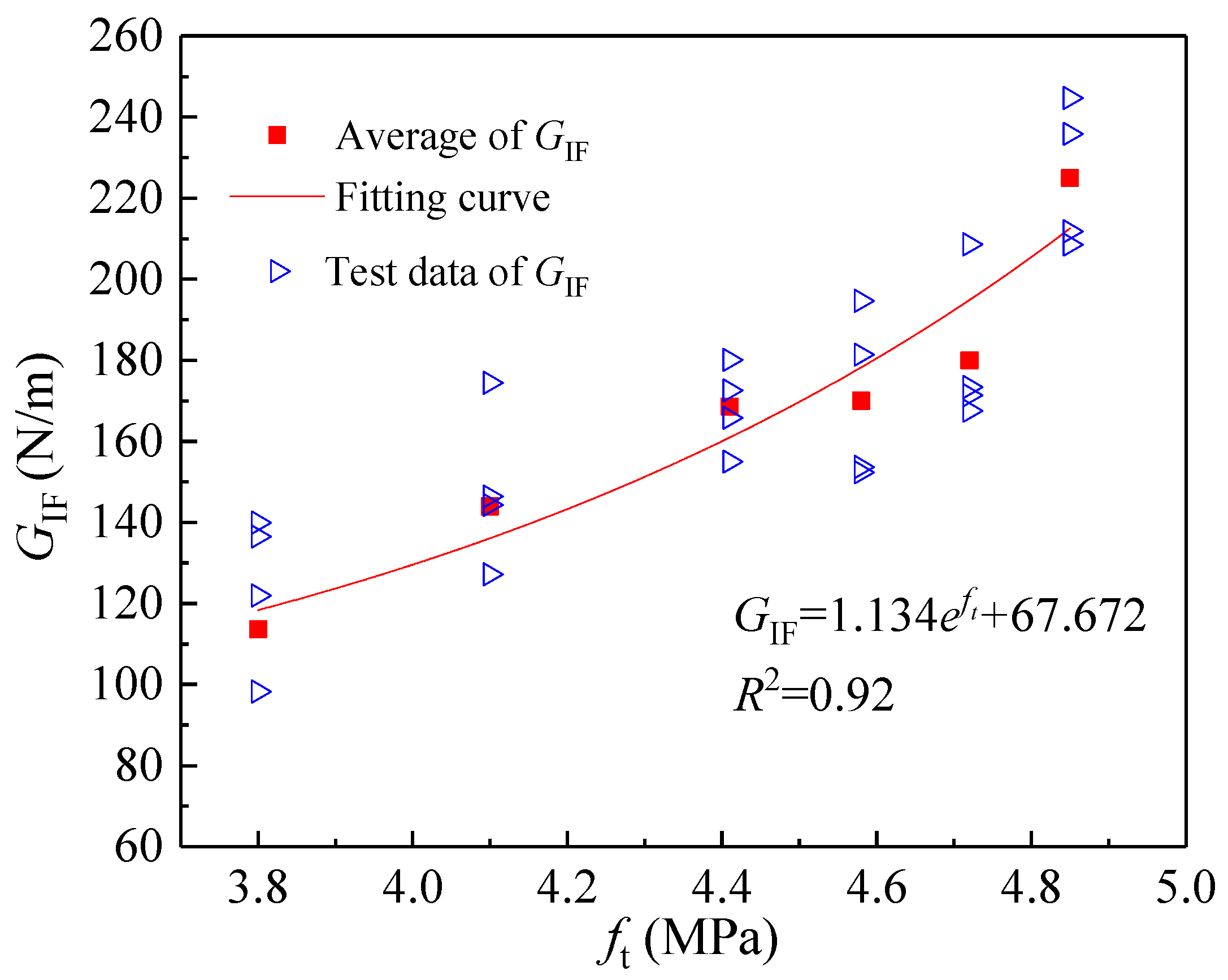

3.2.2. Tensile Strength and Fracture Parameters

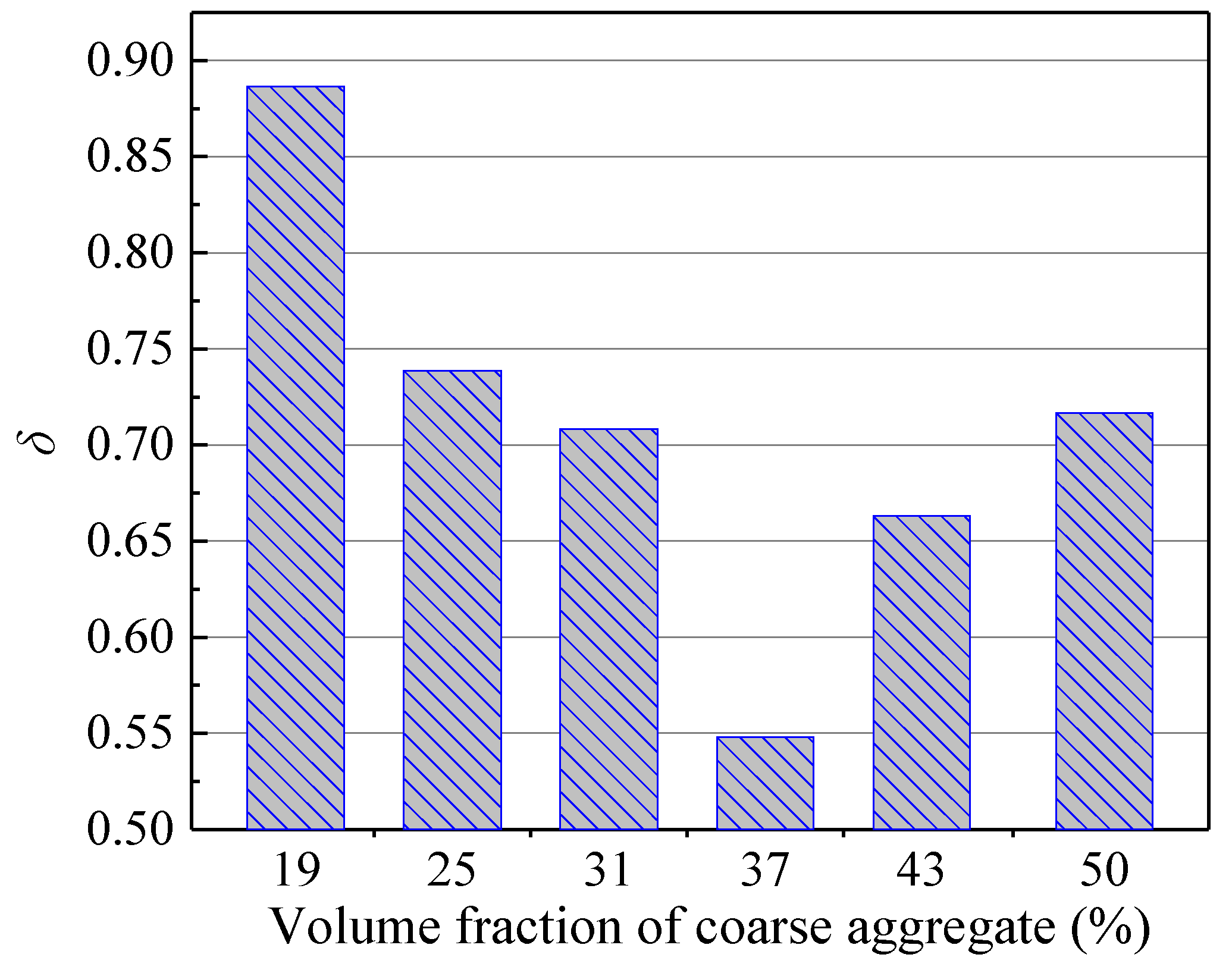

3.2.3. Safety Warning Parameter from the Double-K Fracture Toughness

3.3. Directions for Future Work

4. Conclusions

- Fracture Process and Crack Path: The fracture process of the wedge-splitting test (WST) specimen, characterized by the P-CMOD curve, consistently exhibits three distinct stages: nearly linear elastic state, nonlinear stable crack propagation, and post-peak unstable fracture. The tortuosity of the macroscopic crack path initially increases with the coarse aggregate volume fraction (Va) up to 37%, indicating enhanced crack deflection and energy dissipation, but diminishes thereafter as Va increases to 50%, suggesting a transition in cracking behavior.

- Influence on Basic Mechanical Properties: Both the compressive strength (fc) and elastic modulus (E) monotonically increase with the increase in Va from 19% to 50%. However, the reinforcing effect of coarse aggregates is more pronounced in the lower Va (19–37%), with a significant 22.12% increase in fc, compared to a marginal 2.43% increase in the higher range (37–50%).

- Optimal Fracture Performance: The tensile strength (ft), double-K fracture toughness (initiation toughness and unstable toughness ), and fracture energy (GIF) demonstrate a non-monotonic relationship with Va, peaking at a Va of 37%. This indicates the existence of an optimal Va for maximizing fracture resistance. Notably, is significantly more sensitive to changes in Va than , evidenced by a 350% increase from Va = 19% to 37%, compared to a 16.5% increase for .

- Quantitative Relationships: Strong exponential correlations were established between ft and , , and GIF. These relationships facilitate the prediction of fracture properties based on the more readily measurable tensile strength.

- Safety Warning Parameter: A novel safety warning parameter (δ), defined as the ratio of cohesive toughness to unstable toughness, was proposed to quantitatively assess the pre-peak ductility and provide a warning margin before unstable fracture. For critical concrete structures, a range of Va (25–31%) is recommended, as it offers a balanced combination of high crack initiation resistance and adequate safety warning capacity for critical engineering structures.

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Mukhtar, F.; El-Tohfa, A. A Review On Fracture Propagation in Concrete: Models, Methods, and Benchmark Tests. Eng. Fract. Mech. 2023, 281, 109100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, Y.; Xiao, J.; Zhang, H.; Wang, D.; Zhang, M.; Zhang, J. Effect of Accelerated Carbonation of Fully Recycled Aggregates On Fracture Behaviour of Concrete. Cem. Concr. Compos. 2024, 148, 105442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, J.; Wang, J.; Zhu, F. Influence of Interaction Between Microcracks and Macrocracks On Crack Propagation of Asphalt Concrete. Materials 2024, 17, 2877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.; Zhuo, Y.; Li, D.; Huang, Y. Fracture Toughness of Ordinary Plain Concrete Under Three-Point Bending Based On Double-K and Boundary Effect Fracture Models. Materials 2024, 17, 5387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, K.; Qing, L.; Hu, Y. The Effects of Specimen Size and Aggregate On the Evolution of the Fracture Process Zone in Concrete: A Mesoscale Investigation. Compos. Struct. 2025, 355, 118852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shah, S.P.; McGarry, F.J. Griffith Fracture Criterion and Concrete. J. Eng. Mech. Div. 1971, 97, 1663–1676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elices, M.; Planas, J. Fracture Mechanics Parameters of Concrete. Adv. Cem. Based Mater. 1996, 4, 116–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hillerborg, A.; Modéer, M.; Petersson, P.E. Analysis of Crack Formation and Crack Growth in Concrete by Means of Fracture Mechanics and Finite Elements. Cem. Concr. Res. 1976, 6, 773–781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bažant, Z.P.; Oh, B.H. Crack Band Theory for Fracture of Concrete. Matériaux Constr. 1983, 16, 155–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jenq, Y.S.; Shah, S.P. Two Parameter Fracture Model for Concrete. J. Eng. Mech. 1985, 111, 1227–1241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bažant, Z.P. Size Effect in Blunt Fracture: Concrete, Rock, Metal. J. Eng. Mech. 1984, 110, 518–535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, S.; Reinhardt, H.W. Determination of Double-K Criterion for Crack Propagation in Quasi-Brittle Fracture, Part II: Analytical Evaluating and Practical Measuring Methods for Three-Point Bending Notched Beams. Int. J. Fract. 1999, 98, 151–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, S.; Reinhardt, H.W. Determination of Double-K Criterion for Crack Propagation in Quasi-Brittle Fracture, Part III: Compact Tension Specimens and Wedge Splitting Specimens. Int. J. Fract. 1999, 98, 179–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, S.; Reinhardt, H.W. Determination of Double-Determination of Double-K Criterion for Crack Propagation in Quasi-Brittle Fracture Part I: Experimental Investigation of Crack Propagation. Int. J. Fract. 1999, 98, 111–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Feng, J. Experimental Study On Effect of Coarse Aggregate Volume Fraction On Mode I and Mode II Fracture Behavior of Concrete. J. Adv. Concr. Technol. 2022, 20, 57–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, X.; Chen, H.; Tang, Y.; Li, H. Simplified Determination of Double-K Fracture Parameters of Nuclear Graphite Using the Peak Load. Theor. Appl. Fract. Mech. 2025, 140, 105161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, P.; Yang, Y.; Wang, J.; Jiao, M.; Ling, Y. Fracture Models and Effect of Fibers On Fracture Properties of Cementitious Composites—A Review. Materials 2020, 13, 5495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qing, L.; Li, Q. A Theoretical Method for Determining Initiation Toughness Based On Experimental Peak Load. Eng. Fract. Mech. 2013, 99, 295–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, S.; Barai, S.V. Determining Double-K Fracture Parameters of Concrete for Compact Tension and Wedge Splitting Tests Using Weight Function. Eng. Fract. Mech. 2009, 76, 935–948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, S.; Barai, S.V. Influence of Specimen Geometry On Determination of Double-K Fracture Parameters of Concrete: A Comparative Study. Int. J. Fract. 2008, 149, 47–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kucharczyková, B.; Šimonová, H.; Kocáb, D.; Topolář, L. Advanced Evaluation of the Freeze–Thaw Damage of Concrete Based On the Fracture Tests. Materials 2021, 14, 6378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhuo, K.; Liu, G.; Lan, X.; Zheng, D.; Wu, S.; Wu, P.; Guo, Y.; Lin, J. Fracture Behavior of Steel Slag Powder-Cement-Based Concrete with Different Steel-Slag-Powder Replacement Ratios. Materials 2022, 15, 2243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mu, Y.; Xia, H.; Yan, Y.; Wang, Z.; Guo, R. Fracture Behavior of Basalt Fiber-Reinforced Airport Pavement Concrete at Different Strain Rates. Materials 2022, 15, 7379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Hu, S.; He, Z. Mechanical and Fracture Properties of Fly Ash Geopolymer Concrete Addictive with Calcium Aluminate Cement. Materials 2019, 12, 2982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y.; Zheng, L.; Li, P.; Wang, Q.; Zhang, Y. Effects of Mix Components On Fracture Properties of Seawater Volcanic Scoria Aggregate Concrete. Materials 2024, 17, 4100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bušić, R.; Gazić, G.; Guljaš, I.; Miličević, I. Experimental Determination of Double-K Fracture Parameters for Self-Compacting Concrete with Waste Tire Rubber and Silica Fume. Theor. Appl. Fract. Mech. 2025, 139, 105021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- GB/T 14685-2022; Pebble and Crushed Stone for Construction. Standards Press of China: Beijing, China, 2022.

- Mihashi, H.; Nomura, N.; Niiseki, S. Influence of Aggregate Size On Fracture Process Zone of Concrete Detected with Three Dimensional Acoustic Emission Technique. Cem. Concr. Res. 1991, 21, 737–744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolinski, S.; Hordijk, D.A.; Reinhardt, H.W.; Cornelissen, H.A.W. Influence of Aggregate Size On Fracture Mechanics Parameters of Concrete. Int. J. Cem. Compos. Lightweight Concr. 1987, 9, 95–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Golewski, G.L. Effect of Coarse Aggregate Type On the Fracture Toughness of Ordinary Concrete. Infrastructures 2024, 9, 185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, F.P.; Barr, B.I.G.; Lydon, F.D. Fracture Properties of High Strength Concrete with Varying Silica Fume Content and Aggregates. Cem. Concr. Res. 1995, 25, 543–552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alyhya, W.S.; Abo Dhaheer, M.S.; Al-Rubaye, M.M.; Karihaloo, B.L. Influence of Mix Composition and Strength On the Fracture Properties of Self-Compacting Concrete. Constr. Build. Mater. 2016, 110, 312–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beygi, M.H.A.; Kazemi, M.T.; Nikbin, I.M.; Amiri, J.V.; Rabbanifar, S.; Rahmani, E. The Influence of Coarse Aggregate Size and Volume On the Fracture Behavior and Brittleness of Self-Compacting Concrete. Cem. Concr. Res. 2014, 66, 75–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, B.; Liu, J. Effect of Aggregate On the Fracture Behavior of High Strength Concrete. Constr. Build. Mater. 2004, 18, 585–590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Feng, J.; Li, H.; Meng, Z. Effect of Coarse Aggregate Volume Fraction On Mode II Fracture Toughness of Concrete. Eng. Fract. Mech. 2021, 242, 107472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Li, X.; Li, Z.; Yuan, Y.; Feng, J. Toughening and Toughness Degradation of Concrete Under Varying Volume Fractions of Coarse Aggregate. Theor. Appl. Fract. Mech. 2025, 138, 104976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- GB/T 176-2017; Methods for Chemical Analysis of Cement. Standards Press of China: Beijing, China, 2018.

- GB/T 40407-2021; X-Ray Powder Diffraction Analysis Method for Determining the Phases in Portland Cement Clinker. Standards Press of China: Beijing, China, 2022.

- GB/T 8074-2008; Testing Method for Specific Surface of Cement-Blaine Method. Standards Press of China: Beijing, China, 2008.

- GB/T 17671-2021; Test Method of Cement Mortar Strength (ISO Method). Standards Press of China: Beijing, China, 2022.

- GB/T 1346-2011; Test Methods for Water Requirement of Normal Consistency, Setting Time and Soundness of the Portland Cement. Standards Press of China: Beijing, China, 2012.

- GB/T 50081-2019; Standard for Test Methods of Concrete Physical and Mechanical Properties. China Architecture & Building Press: Beijing, China, 2019.

- Daniewicz, S.R. Accurate and Efficient Numerical Integration of Weight Functions Using Gauss-Chebyshev Quadrature. Eng. Fract. Mech. 1994, 48, 541–544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reinhardt, H.W.; Cornelissen, H.A.W.; Hordijk, D.A. Tensile Tests and Failure Analysis of Concrete. J. Struct. Eng. 1986, 112, 2462–2477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Comite, E.D.B. Ceb-Fip Model Code 1990: Design Code; Thomas Telford Ltd.: London, UK, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- RILEM Technical Committees. Determination of the Fracture Energy of Mortar and Concrete by Means of Three-Point Bend Tests On Notched Beams. Mater. Struct. 1985, 18, 287–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amparano, F.E.; Xi, Y.; Roh, Y.S. Experimental Study On the Effect of Aggregate Content On Fracture Behavior of Concrete. Eng. Fract. Mech. 2000, 67, 65–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.K.; Lee, C.S.; Park, C.K.; Eo, S.H. The Fracture Characteristics of Crushed Limestone Sand Concrete. Cem. Concr. Res. 1997, 27, 1719–1729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Chemical Composition wt (%) | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SiO2 | Fe2O3 | Al2O3 | CaO | MgO | Na2O | K2O | SO3 |

| 22.27 | 2.95 | 6.37 | 60.23 | 4.52 | 0.13 | 0.52 | 2.51 |

| Mineral Composition wt (%) | |||||||

| 3CaO·Al2O3 | 3CaO·SiO2 | 2CaO·SiO2 | 4CaO·Al2O3·Fe2O3 | ||||

| 6.9 | 49.58 | 28.13 | 8.62 | ||||

| Specific Surface Area (m2/kg) | fc (MPa) | ft (MPa) | Setting Time (min) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 329 | 3 d | 28 d | 3 d | 28 d | initial | final |

| 23.5 | 50.3 | 5.6 | 8.8 | 196 | 258 | |

| Group | Va 1 (%) | Specimens | Unit Mass (kg/m3) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cement | Sand | Coarse Aggregate | Limestone Powder | Water | Superplasticizer | |||

| A | 19 | WA01~WA05 | 490 | 1167 | 500 | 96 | 179.3 | 5 |

| B | 25 | WB01~WB05 | 490 | 1000 | 667 | 96 | 179.3 | 5.5 |

| C | 31 | WC01~WC05 | 490 | 834 | 833 | 96 | 179.3 | 6.1 |

| D | 37 | WD01~WD05 | 490 | 667 | 1000 | 96 | 179.3 | 7.4 |

| E | 43 | WE01~WE05 | 490 | 500 | 1167 | 96 | 179.3 | 7.9 |

| F | 50 | WF01~WF05 | 490 | 334 | 1333 | 96 | 179.3 | 8.4 |

| Va (%) | fc (MPa) | ft (MPa) | E (GPa) | (MPa·m1/2) | (MPa·m1/2) | GIF (N/m) | lch (mm) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 19 | 44.79 | 3.8 | 33.23 | 0.12 | 1.01 | 113.66 | 261.57 |

| 25 | 51.96 | 4.1 | 32.3 | 0.28 | 1.09 | 143.94 | 276.58 |

| 31 | 50.08 | 4.41 | 34.01 | 0.34 | 1.17 | 168.56 | 294.78 |

| 37 | 58.36 | 4.85 | 35.26 | 0.54 | 1.20 | 225.01 | 337.28 |

| 43 | 59.43 | 4.72 | 37.04 | 0.39 | 1.16 | 180.23 | 267.41 |

| 50 | 59.78 | 4.58 | 37.85 | 0.32 | 1.13 | 170.52 | 265.19 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Li, X.; Zhang, Y.; Chen, Y.; Yuan, Y.; Feng, J.; Li, Z. The Double-K Fracture Toughness of Concrete with Different Coarse Aggregate Volume Fractions. Materials 2025, 18, 5526. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma18245526

Li X, Zhang Y, Chen Y, Yuan Y, Feng J, Li Z. The Double-K Fracture Toughness of Concrete with Different Coarse Aggregate Volume Fractions. Materials. 2025; 18(24):5526. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma18245526

Chicago/Turabian StyleLi, Xiao, Ying Zhang, Yanwei Chen, Ying Yuan, Jili Feng, and Zhiguang Li. 2025. "The Double-K Fracture Toughness of Concrete with Different Coarse Aggregate Volume Fractions" Materials 18, no. 24: 5526. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma18245526

APA StyleLi, X., Zhang, Y., Chen, Y., Yuan, Y., Feng, J., & Li, Z. (2025). The Double-K Fracture Toughness of Concrete with Different Coarse Aggregate Volume Fractions. Materials, 18(24), 5526. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma18245526