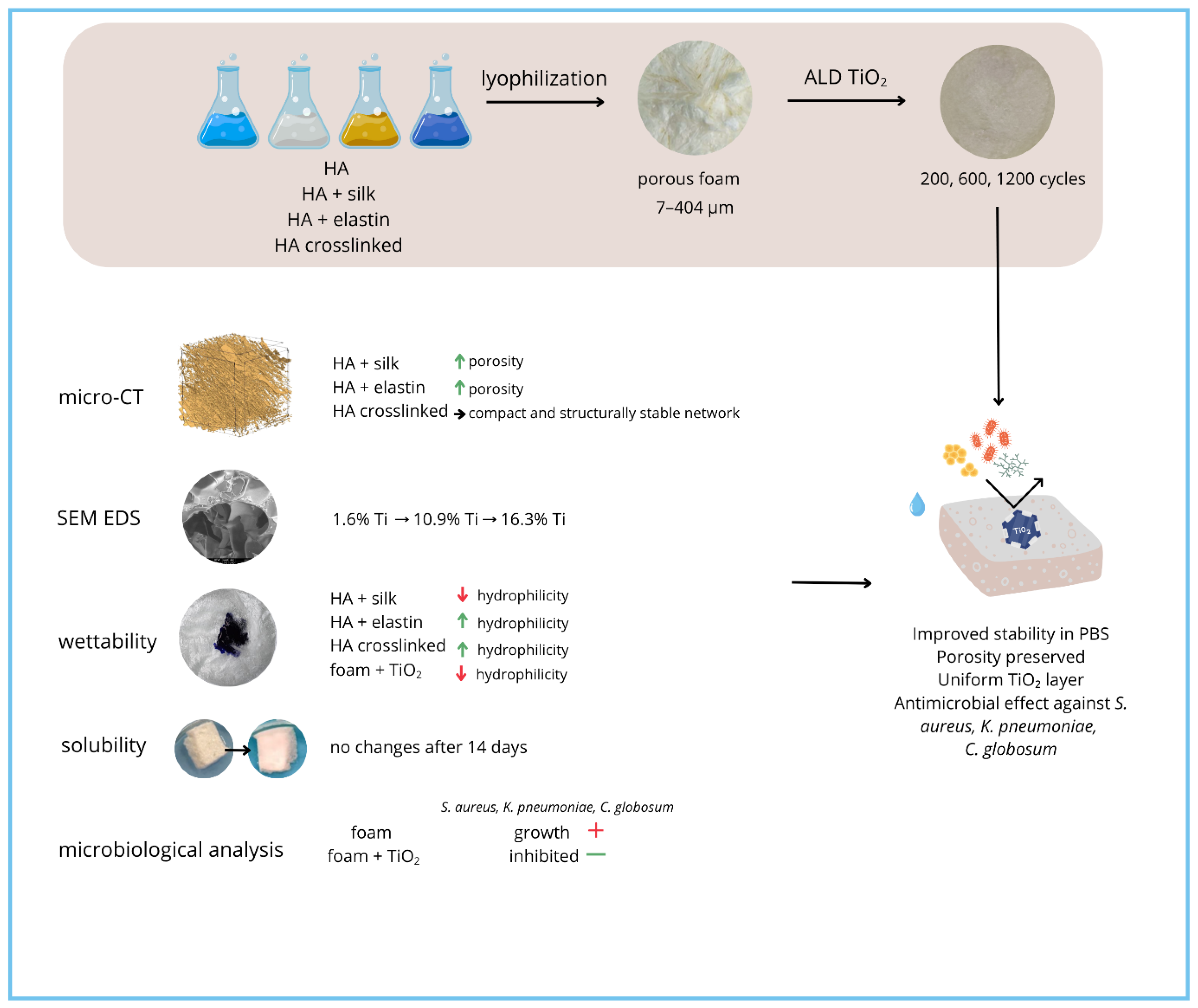

Surface Functionalisation of Hyaluronic Acid-Based Foams with TiO2 via ALD: Structural, Wettability and Antimicrobial Properties Analysis for Biomedical Applications

Highlights

- ALD enables uniform TiO2 coatings on porous HA foams at nanometric scale.

- TiO2 layer protects HA from aqueous degradation and may reduce microbial risk.

- Silk decreases foam hydrophilicity; elastin enhances polarity and water uptake.

- Wettability and solubility depend on distinct mechanisms in HA and modified foams.

- ALD coatings improve scaffold stability for long-term biomedical use.

- TiO2 barrier may support antimicrobial properties, reducing infection risk.

- Protein modifiers allow tuning of foam wettability for tissue engineering.

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials

3. Methods

3.1. Sample Preparation

3.1.1. Preparation of Polymeric Solutions

- HA 2%, 2.0–2.2 MDa

- HA 2%, 2.0–2.2 MDa + 1% silk

- HA 2%, 2.0–2.2 MDa + 2% elastin

- HA 2%, crosslinked

3.1.2. Rheological Properties

3.1.3. Lyophilization

3.1.4. Surface Modification—TiO2 Deposition

3.2. Sample Analysis

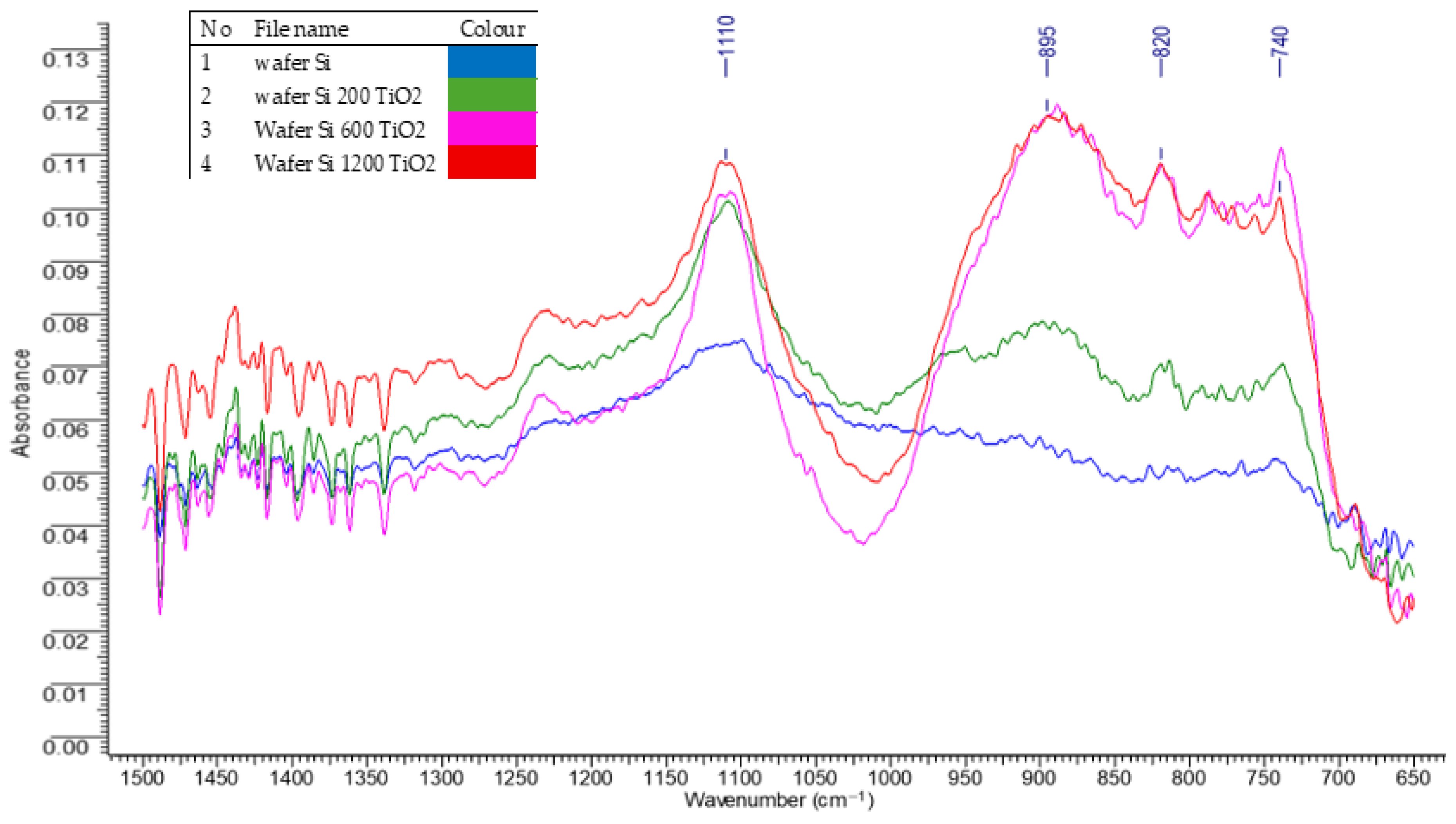

3.2.1. FTIR Absorption Spectroscopy of Deposited Titanium Dioxide Layers

3.2.2. Microscopic Analysis

3.2.3. X-Ray Microtomography

3.2.4. Wettability

3.2.5. Solubility Testing

3.2.6. Antibacterial Testing

4. Results

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

7. Patents

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Al-Shalawi, F.D.; Mohamed Ariff, A.H.; Jung, D.-W.; Mohd Ariffin, M.K.A.; Seng Kim, C.L.; Brabazon, D.; Al-Osaimi, M.O. Biomaterials as implants in the orthopedic field for regenerative medicine: Metal versus synthetic polymers. Polymers 2021, 15, 2601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, X.; Chen, W.; Wang, J.; Zhou, Y. Advances of naturally derived biomedical polymers in tissue engineering. Front. Chem. 2024, 12, 1469183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tawade, P.; Tondapurkar, N.; Jangale, A. Biodegradable and biocompatible synthetic polymers for applications in bone and muscle tissue engineering. J. Med. Sci. 2022, 91, e712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yustisia, Y.; Kato, K. Immunomodulatory properties of mesenchymal stem cells within three-dimensional collagen matrices. Vitr. Cell. Dev. Biol. Anim. 2025. advance online publication. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Q.; Pei, Y.; Tang, K.; Albu-Kaya, M.G. Structure, extraction, processing, and applications of collagen as an ideal component for biomaterials—A review. Collagen Leather 2023, 5, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, J.H.; Gu, J.T.; Dang, G.P.; Wan, M.-C.; Bai, Y.-K.; Bai, Q.; Jiao, K.; Niu, L.-N. DNA-collagen dressing for promoting scarless healing in early burn wound management. Adv. Compos. Hybrid Mater. 2025, 8, 212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumari, R.; Vivekanand, V.; Pareek, N. Chitin and chitosan derivatives and its nanocomposites: Therapeutic applications. In Biotechnological Advances in Chitin and Chitosan Based Biocomposites; Springer: Singapore, 2025; pp. 173–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Obeidat, W.M.; Lahlouh, I.K. Chitosan nanoparticles: Approaches to preparation, key properties, drug delivery systems, and developments in therapeutic efficacy. AAPS PharmSciTech 2025, 26, 108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, R.; Hao, Y.; Francesco, S.; Mao, X.; Huang, W.-C. A chitosan-based antibacterial hydrogel with injectable and self-healing capabilities. Mar. Life Sci. Technol. 2024, 6, 115–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosales, P.; Vitale, D.; Icardi, A.; Sevic, I.; Alaniz, L. Role of hyaluronic acid and its chemical derivatives in immunity during homeostasis, cancer and tissue regeneration. Semin. Immunopathol. 2024, 46, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dutta, R.; Chowdhury, S.; Kar, K.; Mazumder, K. Silk fibroin–based biomaterial scaffold in tissue engineering: Present persuasive perspective. Regen. Eng. Transl. Med. 2025, 11, 531–552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.; Ran, X.; Wang, J.; Wang, S.; Zhang, P.; Gao, E.; Bai, B.; Zhang, J.; Zhou, G.; Lei, D. Elastic fiber-reinforced silk fibroin scaffold with a double-crosslinking network for human ear-shaped cartilage regeneration. Adv. Fiber Mater. 2023, 5, 1008–1024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joshi, R. Biomedical applications of silk fibroin. In Engineering Natural Silk; Springer: Singapore, 2024; pp. 135–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heo, T.-H.; Gu, B.K.; Ohk, K.; Yoon, J.-K.; Son, Y.H.; Chun, H.J.; Yang, D.-H.; Jeong, G.-J. Polynucleotide and hyaluronic acid mixture for skin wound dressing for accelerated wound healing. Tissue Eng. Regen. Med. 2025, 22, 515–526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, E.; Tang, X.; Zhao, M.; Yang, L. Biodegradable multifunctional hyaluronic acid hydrogel microneedle band-aids for accelerating skin wound healing. Drug Deliv. Transl. Res. 2026, 16, 316–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yadav, A.; Waghmare, D.S.; Ahir, A.; Srivastava, A. Comprehensive exploration on chemical functionalization and crosslinked injectable hyaluronic acid hydrogels for tissue engineering applications. Regen. Eng. Transl. Med. 2025, 11, 351–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, S.; Ponting, J.; Rooney, P.; Kumar, P.; Pye, D.; Wang, M. Hyaluronan and angiogenesis: Molecular mechanisms and clinical applications. In Angiogenesis; Springer: Boston, MA, USA, 2023; pp. 219–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, Q.; Zhu, J.; Tu, S.; Fan, X. Enzyme-crosslinked hyaluronic acid-based multifunctional hydrogel promotes diabetic wound healing. Macromol. Res. 2025, 33, 779–788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahmati, M.; Mills, D.K.; Urbanska, A.M.; Saeb, M.R.; Venugopal, J.R.; Ramakrishna, S.; Mozafari, M. Electrospinning for tissue engineering applications. Prog. Mater. Sci. 2020, 117, 100721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abatangelo, G.; Vindigni, V.; Avruscio, G.; Pandis, L.; Brun, P. Hyaluronic acid: Redefining its role. Cells 2020, 9, 1743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grabowski, M.; Gmyrek, D.; Żurawska, M.; Trusek, A. Hyaluronic Acid: Production Strategies, Gel-Forming Properties, and Advances in Drug Delivery Systems. Gels 2025, 11, 424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, Z.; Wang, Y.; Xu, Y.; Wang, J.; Yu, Y. Modification and crosslinking strategies for hyaluronic acid-based hydrogel biomaterials. Smart Med. 2023, 2, e20230029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.; Qin, J.; Hu, Y. Efficient Degradation of High-Molecular-Weight Hyaluronic Acid by a Combination of Ultrasound, Hydrogen Peroxide, and Copper Ion. Molecules 2019, 24, 617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, Y.; Tan, J.; Zhou, Y.; Guo, Y.; Liao, X.; He, L.; Li, D.; Li, X.; Liu, Y. From crosslinking strategies to biomedical applications of hyaluronic acid-based hydrogels: A review. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2023, 231, 123308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fallacara, A.; Baldini, E.; Manfredini, S.; Vertuani, S. Hyaluronic acid in the third millennium. Polymers 2018, 10, 701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Della Sala, F.; Longobardo, G.; Fabozzi, A.; Di Gennaro, M.; Borzacchiello, A. Hyaluronic Acid-Based Wound Dressing with Antimicrobial Properties for Wound Healing Application. Appl. Sci. 2022, 12, 3091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gholamali, I.; Vu, T.T.; Jo, S.-H.; Park, S.-H.; Lim, K.T. Exploring the Progress of Hyaluronic Acid Hydrogels: Synthesis, Characteristics, and Wide-Ranging Applications. Materials 2024, 17, 2439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Trombino, S.; Servidio, C.; Curcio, F.; Cassano, R. Strategies for Hyaluronic Acid-Based Hydrogel Design in Drug Delivery. Pharmaceutics 2019, 11, 407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Priya, A.S.; Premanand, R.; Ragupathi, I.; Bhaviripudi, V.R.; Aepuru, R.; Kannan, K.; Shanmugaraj, K. Comprehensive Review of Hydrogel Synthesis, Characterization, and Emerging Applications. J. Compos. Sci. 2024, 8, 457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, S.; Sharma, A.; Patel, R.; Singh, N. Unlocking the potential of titanium dioxide nanoparticles: An insight into green synthesis, optimizations, characterizations, and multifunctional applications. Microb. Cell Factories 2024, 23, 609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chouirfa, H.; Bouloussa, H.; Migonney, V.; Falentin-Daudré, C. Review of Titanium Surface Modification Techniques and Coatings for Antibacterial Applications. Acta Biomater. 2019, 83, 37–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buzarovska, A.; Gualandi, C.; Parrilli, A.; Scandola, M. Effect of TiO2 Nanoparticle Loading on Poly(l-Lactic Acid) Porous Scaffolds Fabricated by TIPS. Compos. Part B Eng. 2015, 81, 189–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kiran, A.S.K.; Kumar, T.S.S.; Sanghavi, R.; Doble, M.; Ramakrishna, S. Antibacterial and Bioactive Surface Modifications of Titanium Implants by PCL/TiO2 Nanocomposite Coatings. Nanomaterials 2018, 8, 860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nazarov, D.; Kozlova, L.; Rogacheva, E.; Kraeva, L.; Maximov, M. Atomic layer deposition of antibacterial nanocoatings: A review. Antibiotics 2023, 12, 1656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Almaev, A.V.; Yakovlev, N.N.; Almaev, D.A.; Verkholetov, M.G.; Rudakov, G.A.; Litvinova, K.I. High oxygen sensitivity of TiO2 thin films deposited by ALD. Micromachines 2023, 14, 1875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gartner, M.; Szekeres, A.; Stroescu, H.; Mitrea, D.; Covei, M. Advanced nanostructured coatings based on doped TiO2 for various applications. Molecules 2023, 28, 7828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Benčina, M.; Iglič, A.; Mozetič, M.; Junkar, I. Crystallized TiO2 nanosurfaces in biomedical applications. Nanomaterials 2020, 10, 1121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitchell, J.; Lo, K.W.-H. The use of small-molecule co mpounds for cell adhesion and migration in regenerative medicine. Biomedicines 2023, 11, 2507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alvarez-Lorenzo, C.; Ramirez-Romero, A.; Peixoto, D.; Vivero-Lopez, M.; Rodríguez-Moldes, I.; Concheiro, A. Biomimetic cell membrane-coated scaffolds for enhanced tissue regeneration. Adv. Mater. 2025, 37, e2507084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khalili, A.A.; Ahmad, M.R. A review of cell adhesion studies for biomedical and biological applications. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2015, 16, 18149–18184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yeung, T.; Georges, P.C.; Flanagan, L.A.; Marg, B.; Ortiz, M.; Funaki, M.; Zahir, N.; Ming, W.; Weaver, W.; Janmey, P.A. Effects of substrate stiffness on cell morphology, cytoskeletal structure, and adhesion. Cell Motil. Cytoskelet. 2005, 60, 24–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryma, M.; Tylek, T.; Liebscher, J.; Blum, C.; Fernandez, R.; Böhm, C.; Kastenmüller, W.; Gasteiger, G.; Groll, J. Translation of collagen ultrastructure to biomaterial fabrication for material-independent but highly efficient topographic immunomodulation. Adv. Mater. 2021, 33, 2101228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- SanSegundo, E.C.; Mirzaali, M.J.; Fratila-Apachitei, L.E.; Zadpoor, A.A. Magnetized cell-scaffold constructs for bone tissue engineering: Advances in fabrication and magnetic stimulation. Adv. Sci. 2025, 12, e10094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pabjańczyk-Wlazło, E.; Tarzyńska, N.; Bednarowicz, A.; Puszkarz, A.K.; Szparaga, G. Polymer-based electrophoretic deposition of nonwovens for medical applications: The effect of carrier structure, solution, and process parameters. Mar. Drugs 2021, 19, 533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pabjańczyk-Wlazło, E.K.; Puszkarz, A.K.; Bednarowicz, A.; Tarzyńska, N.; Sztajnowski, S. The influence of surface modification with biopolymers on the structure of melt-blown and spun-bonded poly(lactic acid) nonwovens. Materials 2022, 15, 7097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pabjańczyk-Wlazło, E.; Król, P.; Krucińska, I.; Chrzanowski, M.; Puchalski, M.; Szparaga, G.; Kadłubowski, S.; Boguń, M. Bioactive nanofibrous structures based on hyaluronic acid. Adv. Polym. Technol. 2018, 37, 21851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pabjańczyk-Wlazło, E.; Krucińska, I.; Chrzanowski, M.; Szparaga, G.; Chaberska, A.; Kolesińska, B.; Komisarczyk, A.; Boguń, M. Fabrication of pure electrospun materials from hyaluronic acid. Fibres Text. East. Eur. 2017, 25, 52–58. Available online: https://yadda.icm.edu.pl/baztech/element/bwmeta1.element.baztech-1c84afba-e6db-4256-ad93-eef33aae17a5/c/7_pabjanczyk-walzlo_i_inni_fibres_2017_3.pdf (accessed on 4 December 2025). [CrossRef]

- Ostwald, W. Über die Geschwindigkeitsfunktion der Viskosität disperser Systeme. Kolloid-Zeitschrift 1925, 36, 157–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katsidis, C.C.; Siapkas, D.I. General transfer-matrix method for optical multilayer systems with coherent, partially coherent, and incoherent interference. Appl. Opt. 2002, 41, 3978–3987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, K.; Qin, X.; Palomino, R.M.; Simonovis, J.P.; Senanayake, S.D.; Rodriguez, J.A.; Zaera, F. Redox properties of TiO2 thin films grown on mesoporous silica by atomic layer deposition. J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 2023, 14, 4696–4703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tegewa Drop Test. Melliand Textilberichte 1987, 68, 581–583.

- Bahners, T.; Gutmann, J.S. Procedures for the characterization of wettability and surface free energy of textiles—Use, abuse, misuse and proper use: A critical review. Res. Adv. Appl. Chem. 2019, 10, 97–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ISO 20645:2004; Textile Fabrics—Determination of Antibacterial Activity—Agar Diffusion Plate Test. ISO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2004.

- EN 14119:2003; Testing of Textiles—Evaluation of the Action of Microfungi. CEN: Brussels, Belgium, 2003.

- Chambre, L.; Martín-Moldes, Z.; Parker, R.N.; Kaplan, D.L. Bioengineered elastin- and silk-biomaterials for drug and gene delivery. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 2020, 160, 186–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fathi, A.; Mithieux, S.M.; Wei, H.; Chrzanowski, W.; Valtchev, P.; Weiss, A.S.; Dehghani, F. Elastin based cell-laden injectable hydrogels with tunable gelation, mechanical and biodegradation properties. Biomaterials 2014, 35, 5425–5435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chiappim, W.; Testoni, G.E.; de Lima, J.S.B.; Medeiros, H.S.; Pessoa, R.S.; Grigorov, K.G.; Vieira, L.; Maciel, H.S. Effect of process temperature and reaction cycle number on atomic layer deposition of TiO2 thin films using TiCl4 and H2O precursors: Correlation between material properties and process environment. Braz. J. Phys. 2016, 46, 56–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lai, X.; Weng, Y.; Chen, G.; Que, S.; Zhou, X.; Yan, Q.; Wu, C.; Guo, T.; Sun, J.; Zhang, Y. Morphology regulation of TiO2 thin film by ALD growth temperature and its applications to encapsulation and light extraction. J. Mater. Sci. Mater. Electron. 2020, 31, 21316–21324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jolivet, A.; Labbé, C.; Frilay, C.; Debieu, O.; Marie, P.; Horcholle, B.; Lemarié, F.; Portier, X.; Grygiel, C.; Cardina, J.; et al. Structural, optical, and electrical properties of TiO2 thin films deposited by ALD: Impact of the substrate, the deposited thickness and the deposition temperature. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2023, 608, 155214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Igamov, B.D.; Bekpulatov, I.R.; Normamatov, A.M.; Imanova, G.; Kamardin, A.I. Correlation between thickness-dependent morphology, phase structure, and vibrational properties of TiO2 thin films deposited via DC magnetron sputtering: A multi-technique characterization approach. Next Mater. 2025, 9, 101354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keskiväli, L.; Seppänen, T.; Porri, P.; Pääkkönen, E.; Ketoja, J.A. Atomic layer deposited TiO2 on a foam-formed cellulose fibre network—Effect on hydrophobicity and physical properties. BioResources 2023, 18, 7923–7942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

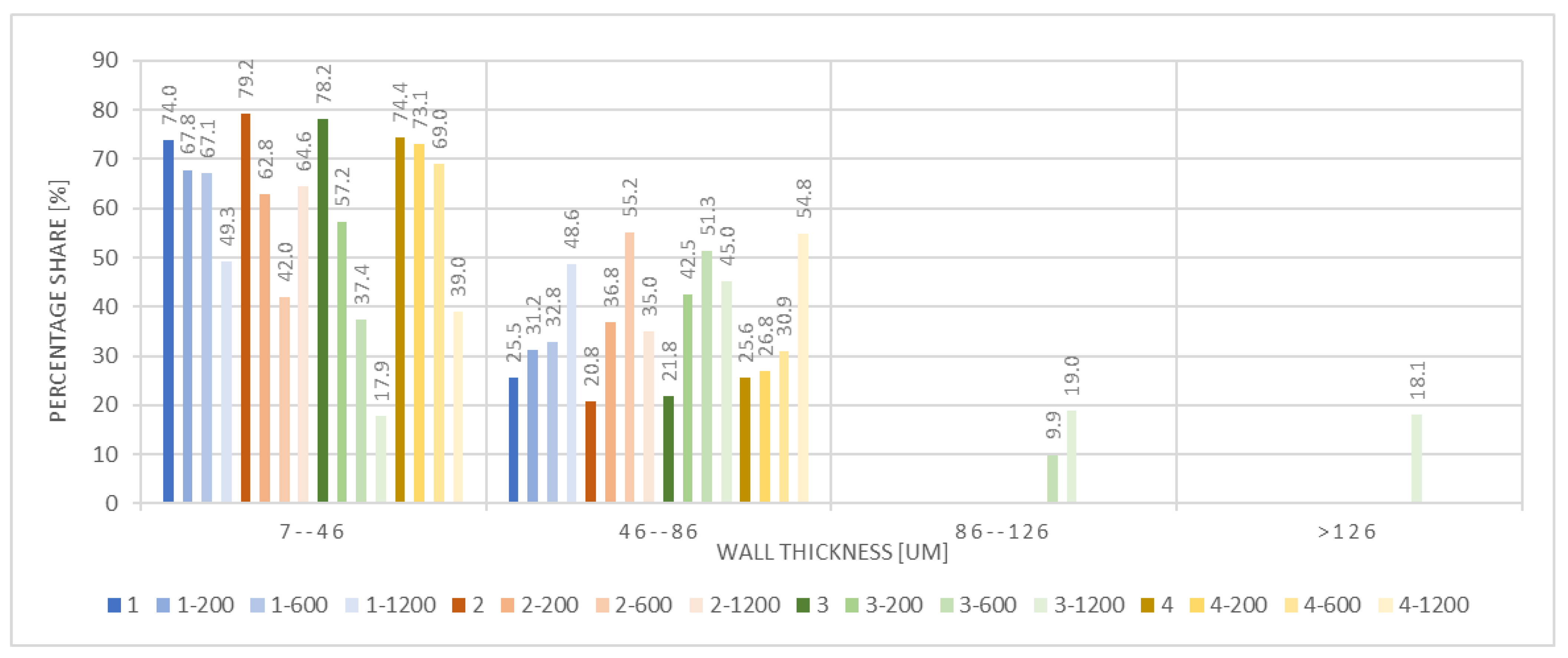

- Bružauskaitė, I.; Bironaitė, D.; Bagdonas, E.; Bernotienė, E. Scaffolds and cells for tissue regeneration: Different scaffold pore sizes—Different cell effects. Cytotechnology 2016, 68, 355–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yanguas-Gil, A. Physical and Chemical Vapor Deposition Techniques. In Growth and Transport in Nanostructured Materials; SpringerBriefs in Materials; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2016; pp. 19–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Li, Y.; Cao, K.; Chen, R. Advances in Atomic Layer Deposition. Int. J. Extrem. Manuf. 2022, 4, 22001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barreiro, D.L.; Houben, K.; Schouten, O.; Koenderink, G.H.; Thies, J.C.; Sagt, C.M.J. Order–Disorder Balance in Silk-Elastin-like Polypeptides Determines Their Self-Assembly into Hydrogel Networks. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2025, 17, 650–662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, D.; Sun, C.; Han, Z.; Yuan, B.; Pan, D.; Chen, J.; Xu, H.; Liu, C.; Shen, C. Intermolecular interaction simultaneously mediated network morphology and β-sheet crystallization of silk fibroin/polyacrylamide hydrogel for its excellent adhesive strain sensing performances. Sci. China Mater. 2024, 67, 1533–1542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vazquez-Portalatin, N.; Alfonso-Garcia, A.; Liu, J.C.; Marcu, L.; Panitch, A. Physical, biomechanical, and optical characterization of collagen and elastin blend hydrogels. Ann. Biomed. Eng. 2020, 48, 2924–2935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pal, P.; Nguyen, Q.C.; Benton, A.H.; Marquart, M.E.; Janorkar, A.V. Drug-Loaded Elastin-Like Polypeptide-Collagen Hydrogels with High Modulus for Bone Tissue Engineering. Macromol. Biosci. 2019, 19, e1900142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vorvolakos, K.; Isayeva, I.S.; Luu, H.M.; Patwardhan, D.V.; Pollack, S.K. Ionically cross-linked hyaluronic acid: Wetting, lubrication, and viscoelasticity of a modified adhesion barrier gel. Med. Devices 2011, 4, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Israelachvili, J.N. Intermolecular and Surface Forces, 3rd ed.; Academic Press: San Diego, CA, USA, 2011; pp. 305–320, 331–340, ISBN: 978-0-12-391927-4, eBook ISBN: 9780123919335. [Google Scholar]

- Jothi Prakash, C.G.; Prasanth, R. Approaches to design a surface with tunable wettability: A review on surface properties. J. Mater. Sci. 2021, 56, 108–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Microorganism | Significance in the Field |

|---|---|

| Klebsiella pneumoniae (Gram-negative bacterium) | K. pneumoniae is a clinically significant, opportunistic Gram-negative pathogen, often implicated in severe hospital-acquired infections, including pneumonia, wound, urinary tract, and bloodstream infections. It is commonly associated with multidrug resistance and biofilm formation on medical devices and scaffolds. Testing against K. pneumoniae demonstrates whether the biomaterial provides protection against highly relevant nosocomial bacteria that commonly colonize medical scaffolds or dressings. |

| Staphylococcus aureus (Gram-positive bacterium) | S. aureus, including methicillin-resistant strains (MRSA), is a leading cause of wound infections, implant colonization, osteomyelitis, and sepsis. Its ability to adhere to surfaces and form biofilms makes it a primary target in biomaterial evaluation for medical devices, wound dressings, and tissue engineering scaffolds. Effective inhibition of S. aureus growth is thus one of the most essential requirements for materials intended for contact with biological tissues. |

| Aspergillus niger (filamentous fungus) | A. niger represents a model of pathogenic filamentous fungi, frequently causing invasive infections in immunocompromised patients, as well as being a major causative agent of biomaterial- and device-associated fungal colonization. For applications in regenerative medicine, prevention of fungal contamination is critical for safety and material longevity. |

| Chateomium globosum (saprophytic mold) | C. globosum is a ubiquitous environmental fungus known for its strong cellulolytic and proteolytic enzymatic activity, often involved in the biodeterioration of biomaterials, textiles, and polymers. Testing susceptibility against C. globosum addresses the long-term resistance of materials to environmental fungal colonization and degradation, relevant in both hospital and ambient settings. |

| HA 2% 2.0–2.2 | HA 2% 2.0–2.2 + 1% Silk | HA 2% 2.0–2.2 + 2% Elastin | HA 2% Crosslinked | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| k | 55.959 | 45.790 | 42.259 | 0.840 |

| n | 0.397 | 0.430 | 0.453 | 0.790 |

|  |  |  |

| Cycle Numer n | Layer Thickness [nm] | Layer Increment [Å/cycle] | Error | Correlation R2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 200 | 5.7 | 0.285 | 0.013 | 0.19 |

| 600 | 16.5 | 0.275 | 0.009 | 0.88 |

| 1200 | 31.2 | 0.260 | 0.013 | 0.97 |

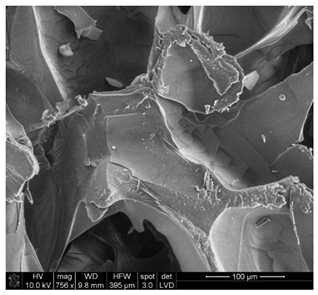

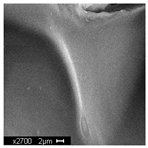

| Sample 1—n = 200 | |

|  |

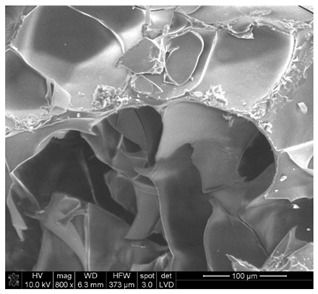

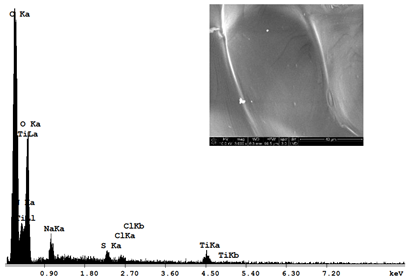

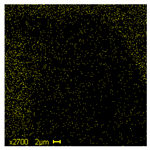

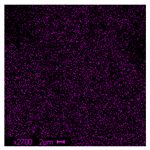

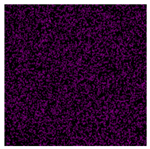

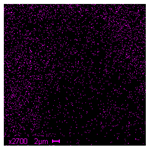

| SEM | EDS |

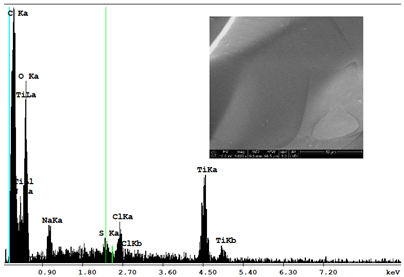

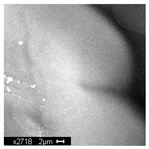

| Sample 1—n = 600 | |

|  |

| SEM | EDS |

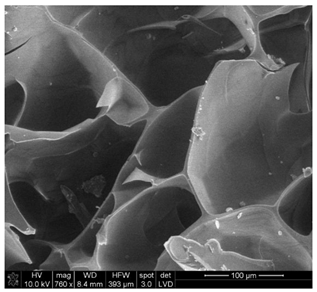

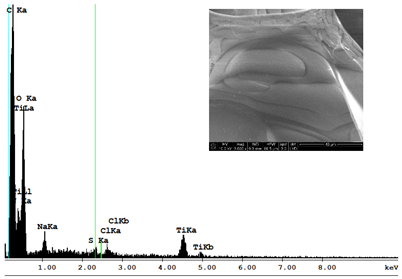

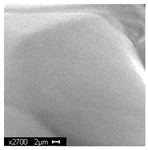

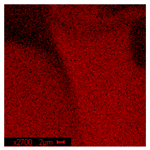

| Sample 1—n = 1200 | |

|  |

| SEM | EDS |

| n = 200 (%) |  | n = 600 (%) |  | n = 1200 (%) | |

| C |  | 54.38 |  | 45.74 |  | 43.00 |

| O |  | 41.01 |  | 38.88 |  | 36.02 |

| Na |  | 1.99 |  | 2.13 |  | 1.64 |

| S |  | 0.53 |  | 0.68 |  | 1.25 |

| Cl |  | 0.41 |  | 1.67 |  | 1.78 |

| Ti |  | 1.64 |  | 10.89 |  | 16.30 |

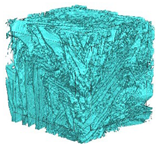

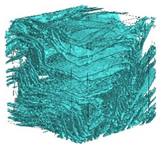

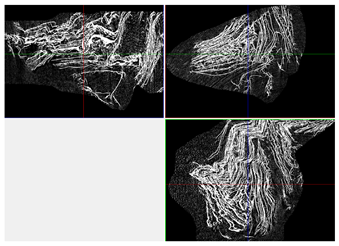

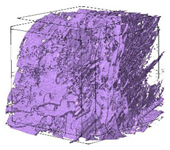

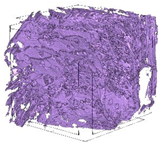

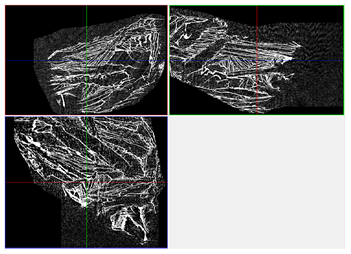

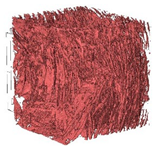

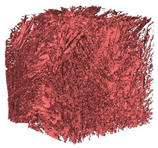

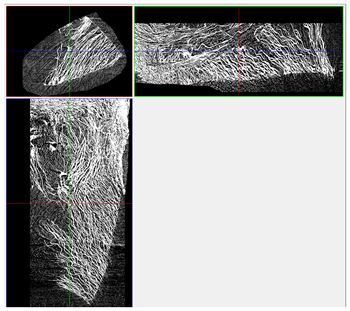

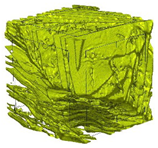

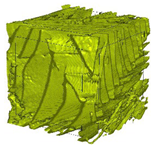

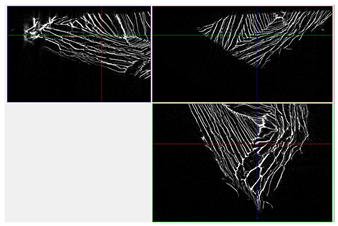

| 3D Visualizations | 2D Visualizations of the Edges | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Sample 1-600 |  |  |  |

| Sample 2-600 |  |  |  |

| Sample 3-600 |  |  |  |

| Sample 4-600 |  |  |  |

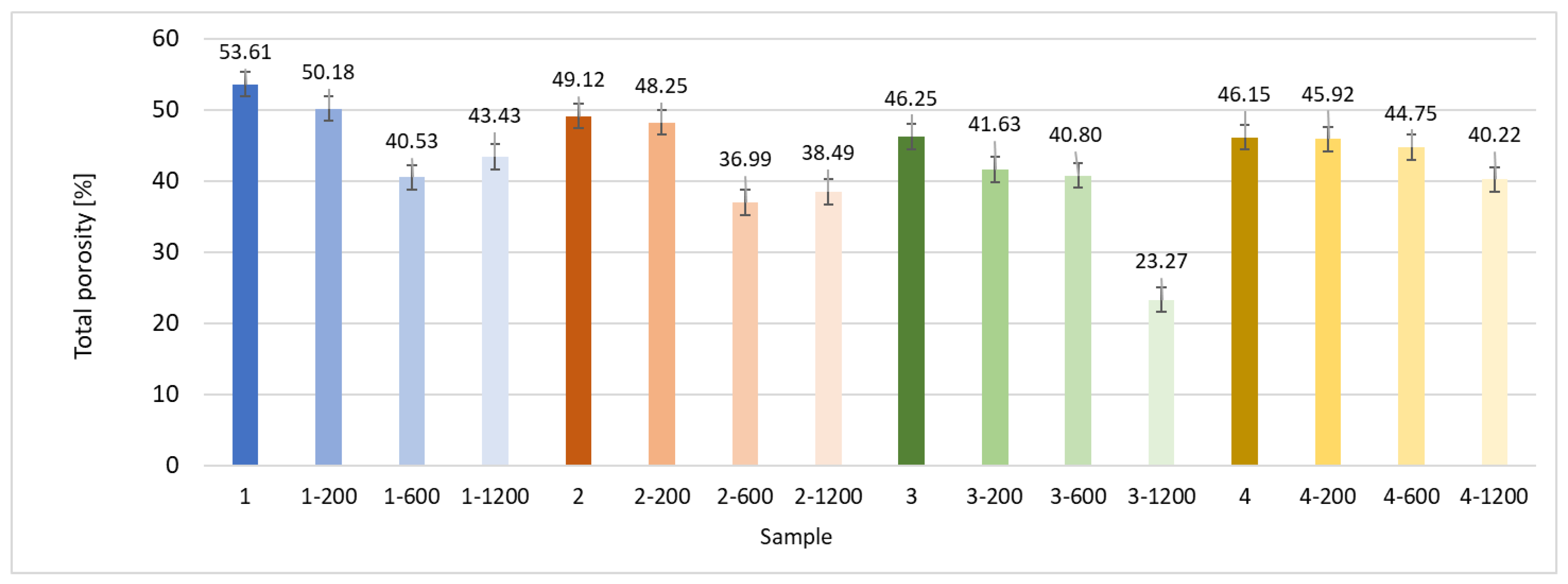

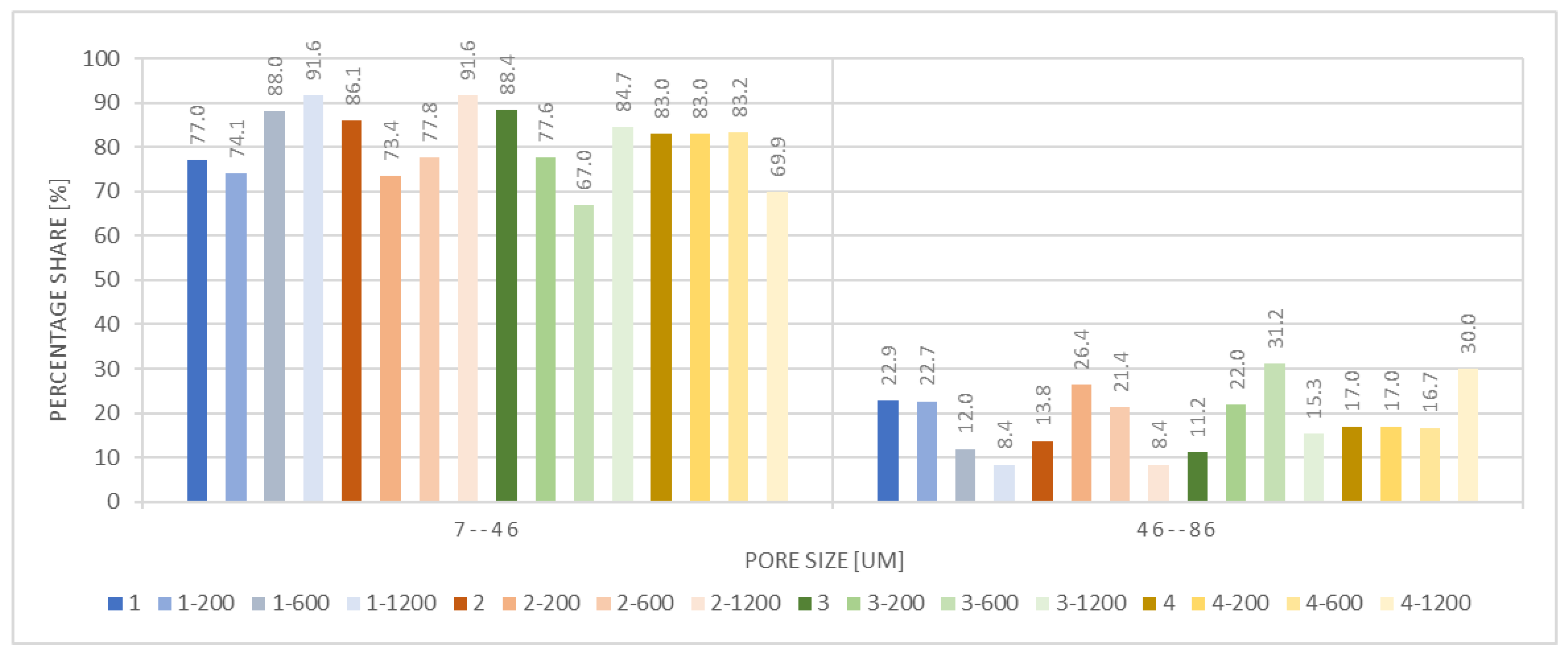

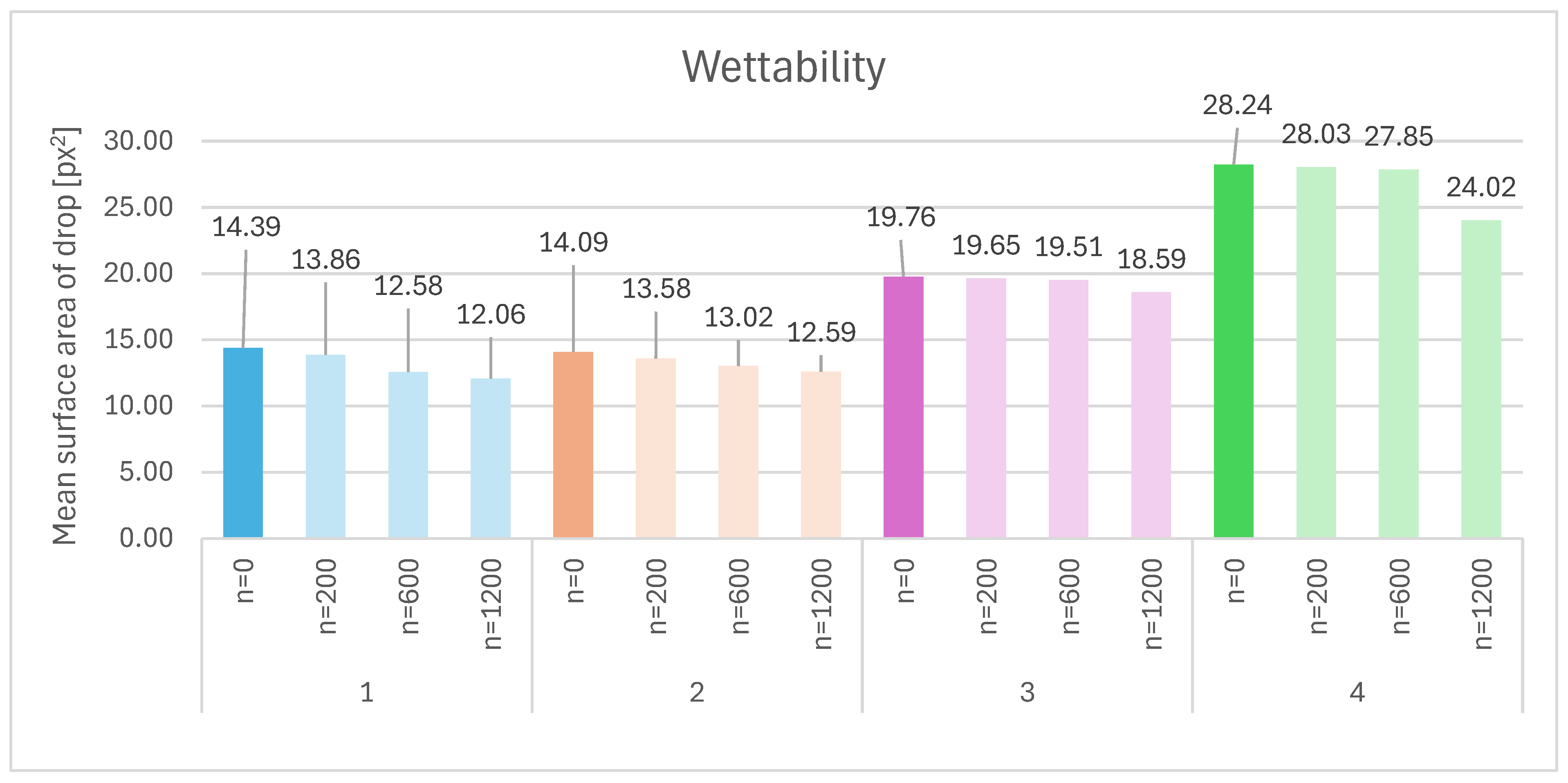

| Sample | Composition | n = 0 [px2] | n = 200 [px2] | n = 600 [px2] | n = 1200 [px2] | Δ200 vs. 0 [%] | Δ600 vs. 0 [%] | Δ1200 vs. 0 [%] | Relative to Sample 1 at n = 0 | Relative to Sample 1 at n = 1200 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | HA 2% | 14.39 | 13.86 | 12.58 | 12.06 | −3.7% | −12.6% | −16.2% | — | — |

| 2 | HA 2% + 1% silk | 14.09 | 13.58 | 13.02 | 12.59 | −3.6% | −7.6% | −10.6% | −2.1% | +4.4% |

| 3 | HA 2% + 2% elastin | 19.76 | 19.65 | 19.51 | 18.59 | −0.6% | −1.3% | −5.9% | +37.3% | +54.2% |

| 4 | HA 2% crosslinked | 28.24 | 28.03 | 27.85 | 24.02 | −0.7% | −1.4% | −15.0% | +96.3% | +99.3% |

| n = 0 Cycles | n = 200 Cycles | n = 600 Cycles | n = 1200 Cycles | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| t = 0 | The foam retains its structural integrity and original dimensions. |  | The foam retains its structural integrity and original dimensions. |  | The foam retains its structural integrity and original dimensions. |  | The foam retains its structural integrity and original dimensions. |  |

| 3 days | The foam exhibited a noticeable reduction in volume, accompanied by visible signs of dissolution along its edges. Additionally, an increase in the material’s transparency was observed. | No changes | ||||||

| 9 days | Progression of changes | No changes | ||||||

| 14 days | The foam lost most of its volume, with visible signs of dissolution; the sample transitioned into a hydrogel without a discernible structure. |  | No changes |  | No changes |  | No changes |  |

| Sample | Klebsiella pneumoniae | Staphylococcus aureus | Aspergillus niger | Chateomium globosum |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| n = 0 | +++ | +++ | +++ | +++ |

| Strong microbial growth. No inhibition zone was detected, and no reduction in growth was noted compared to the control. | Strong microbial growth. No inhibition zone compared to the control. | Extensive growth, covering the entire surface, with intensity comparable to the control. | Strong microbial growth with intensity similar to the control. | |

| n = 1200 | - | - | +++ | – |

| No microbial growth exhibited a clear inhibition zone exceeding 1 mm. | No microbial growth exhibited a clear inhibition zone exceeding 1 mm. | Growth visible without magnification devices, covering up to 25% of the examined area. | No visible growth assessed under a microscope (×50). |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Pabjańczyk-Wlazło, E.; Tarzyńska, N.; Bednarowicz, A.; Puszkarz, A.K.; Szparaga, G.; Sztajnowski, S.; Kaczmarek, P. Surface Functionalisation of Hyaluronic Acid-Based Foams with TiO2 via ALD: Structural, Wettability and Antimicrobial Properties Analysis for Biomedical Applications. Materials 2025, 18, 5530. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma18245530

Pabjańczyk-Wlazło E, Tarzyńska N, Bednarowicz A, Puszkarz AK, Szparaga G, Sztajnowski S, Kaczmarek P. Surface Functionalisation of Hyaluronic Acid-Based Foams with TiO2 via ALD: Structural, Wettability and Antimicrobial Properties Analysis for Biomedical Applications. Materials. 2025; 18(24):5530. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma18245530

Chicago/Turabian StylePabjańczyk-Wlazło, Ewelina, Nina Tarzyńska, Anna Bednarowicz, Adam K. Puszkarz, Grzegorz Szparaga, Sławomir Sztajnowski, and Piotr Kaczmarek. 2025. "Surface Functionalisation of Hyaluronic Acid-Based Foams with TiO2 via ALD: Structural, Wettability and Antimicrobial Properties Analysis for Biomedical Applications" Materials 18, no. 24: 5530. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma18245530

APA StylePabjańczyk-Wlazło, E., Tarzyńska, N., Bednarowicz, A., Puszkarz, A. K., Szparaga, G., Sztajnowski, S., & Kaczmarek, P. (2025). Surface Functionalisation of Hyaluronic Acid-Based Foams with TiO2 via ALD: Structural, Wettability and Antimicrobial Properties Analysis for Biomedical Applications. Materials, 18(24), 5530. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma18245530