Surface Performance Evaluation and Mix Design of Porous Concrete with Noise Reduction and Drainage Performance

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Experimental Design

2.1.1. Materials

2.1.2. Specimen Preparation

2.2. Testing Method

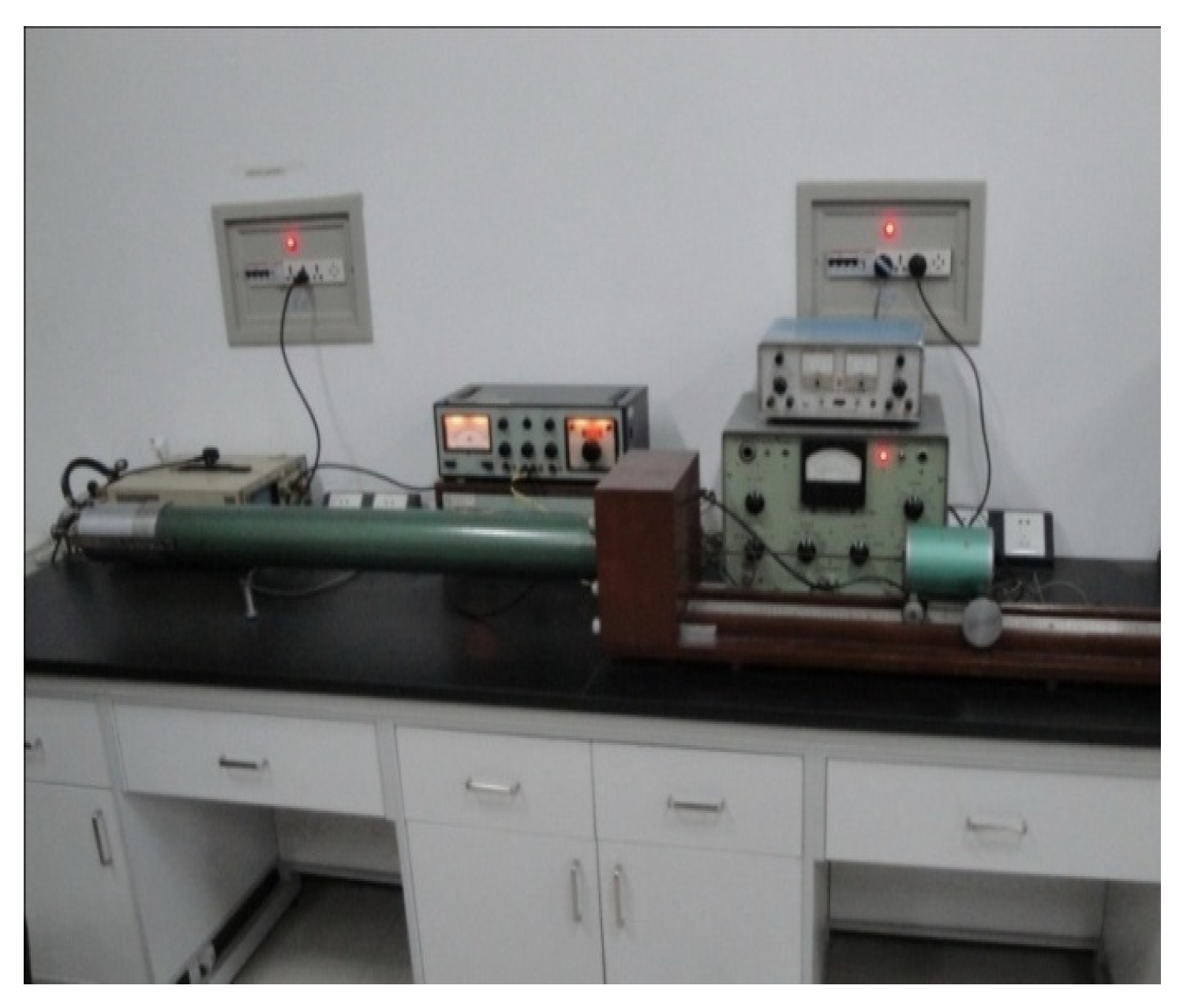

2.2.1. Sound Absorption Test

- (1)

- Prepare cylindrical specimens with a diameter of 95 mm, as specified in Table 4.

- (2)

- Place the specimens into the test apparatus and seal all gaps with plasticine to ensure airtightness.

- (3)

- Position the apparatus within the testing device, adjust the frequency, and record the corresponding sound absorption coefficients.

2.2.2. Void Ratio Test

- (1)

- The specimen’s length, width, and height were measured three times, and the average values were calculated.

- (2)

- The specimen volume was then computed, and the porosity was determined using Equations (3) and (4).

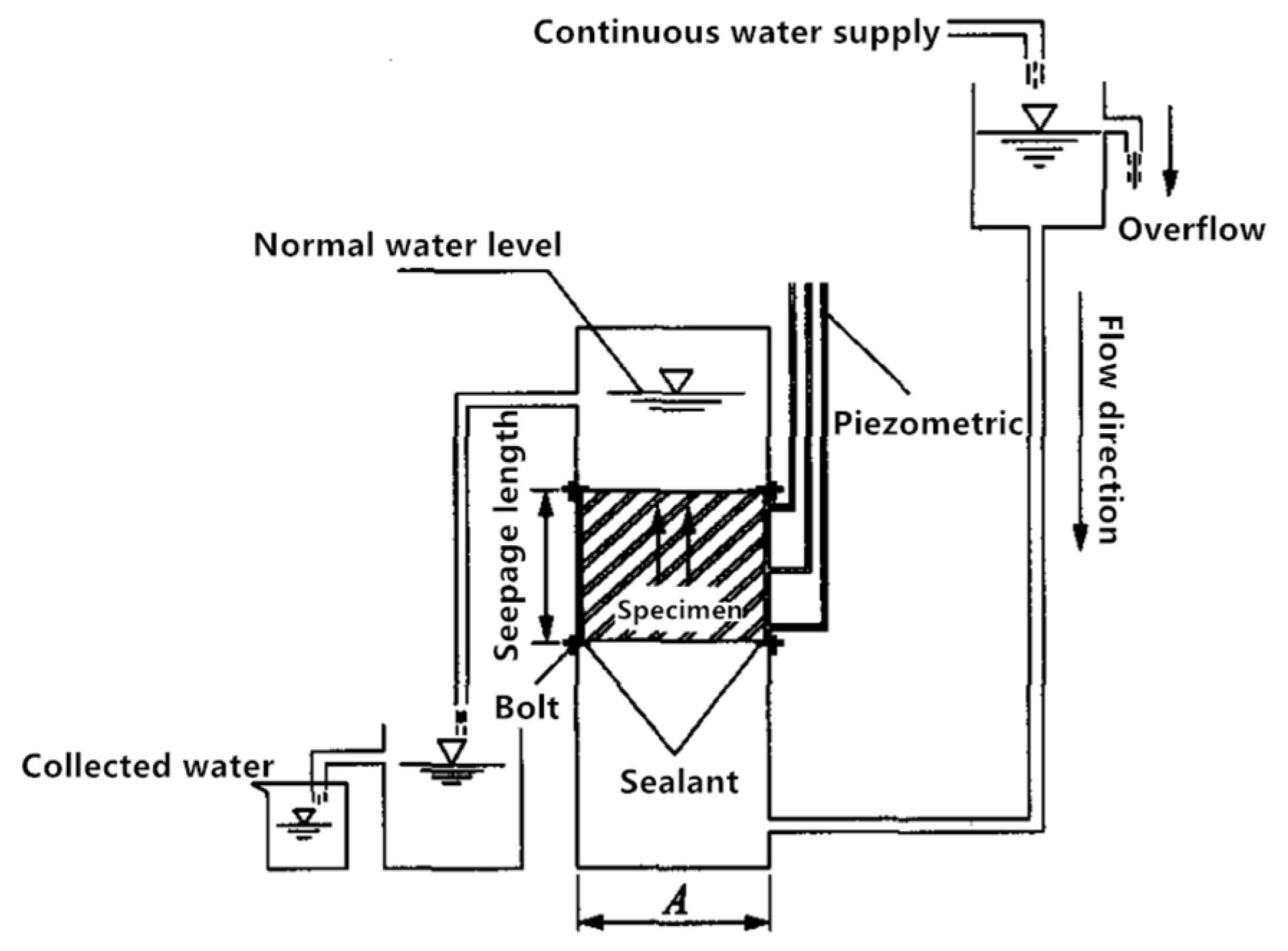

2.2.3. Permeability Coefficient Test

2.2.4. Wear Resistance Experiment

2.2.5. Strength Test

2.2.6. Workability Evaluation Test

- (1)

- Test Procedure

- (2)

- Evaluation of Workability

2.3. Mix Design Parameters

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Sound Absorption Performance

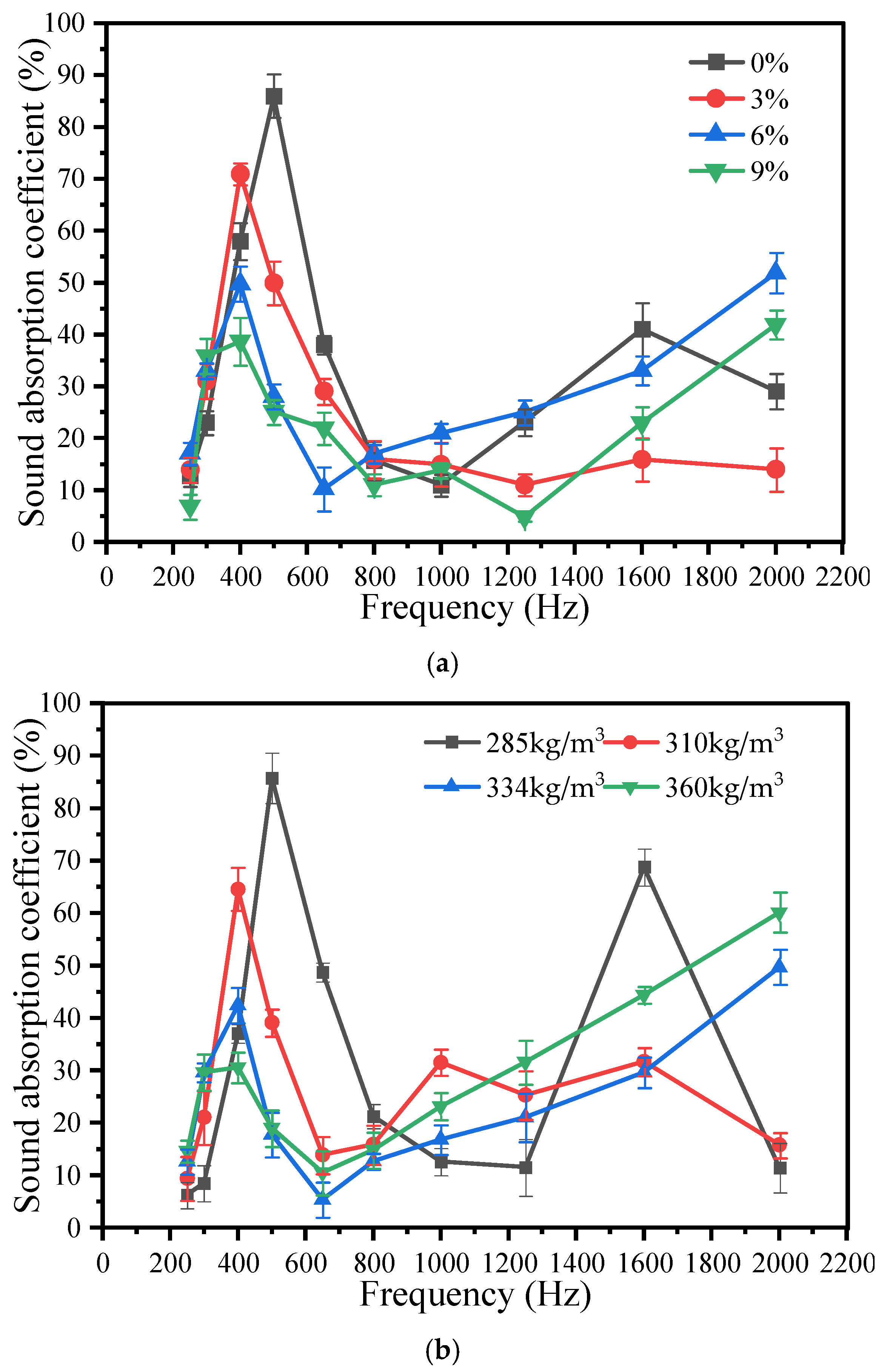

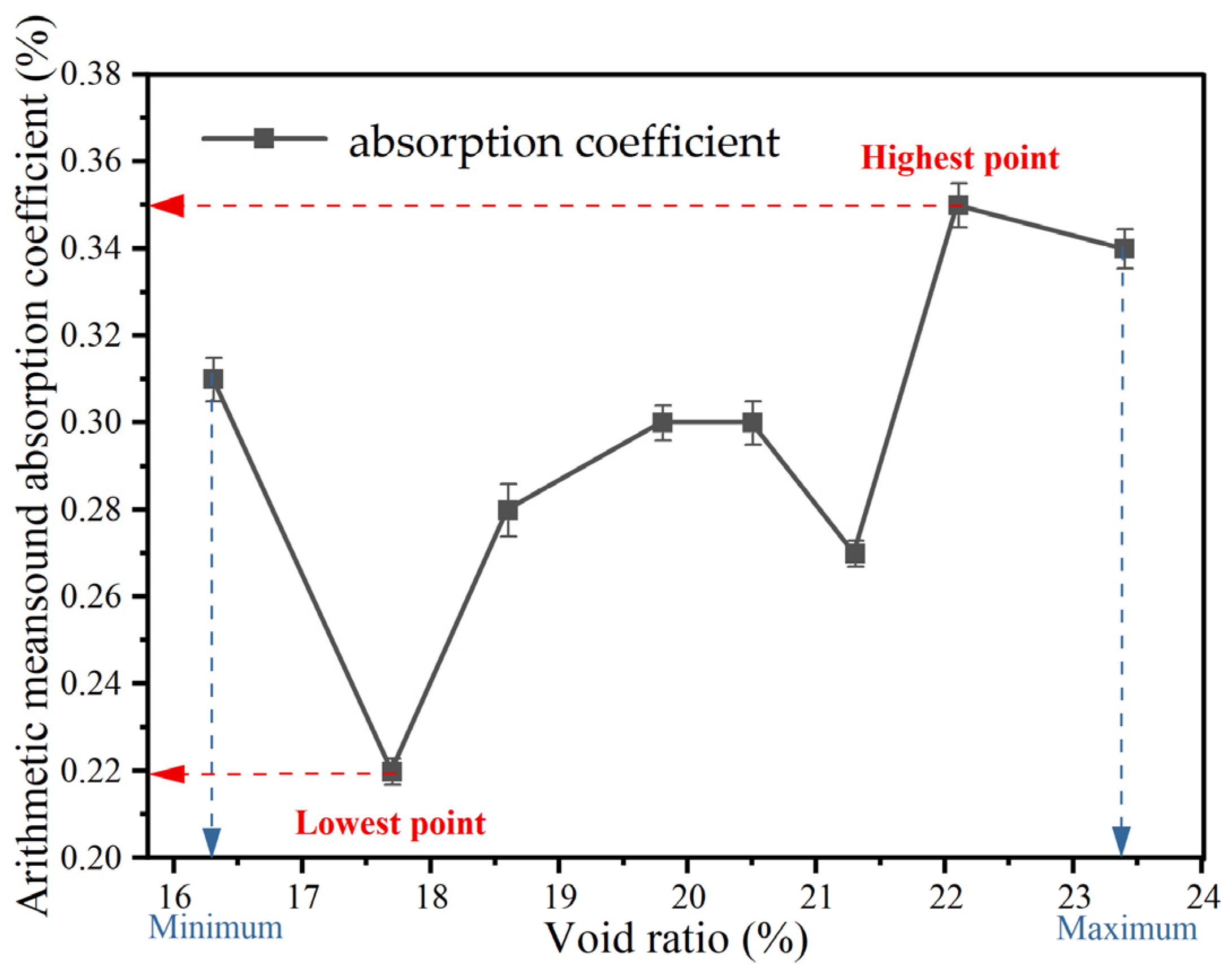

3.1.1. The Influence of Mix Proportion on Sound Absorption Performance

3.1.2. The Effect of Thickness on Sound Absorption Performance

3.2. Drainage Performance

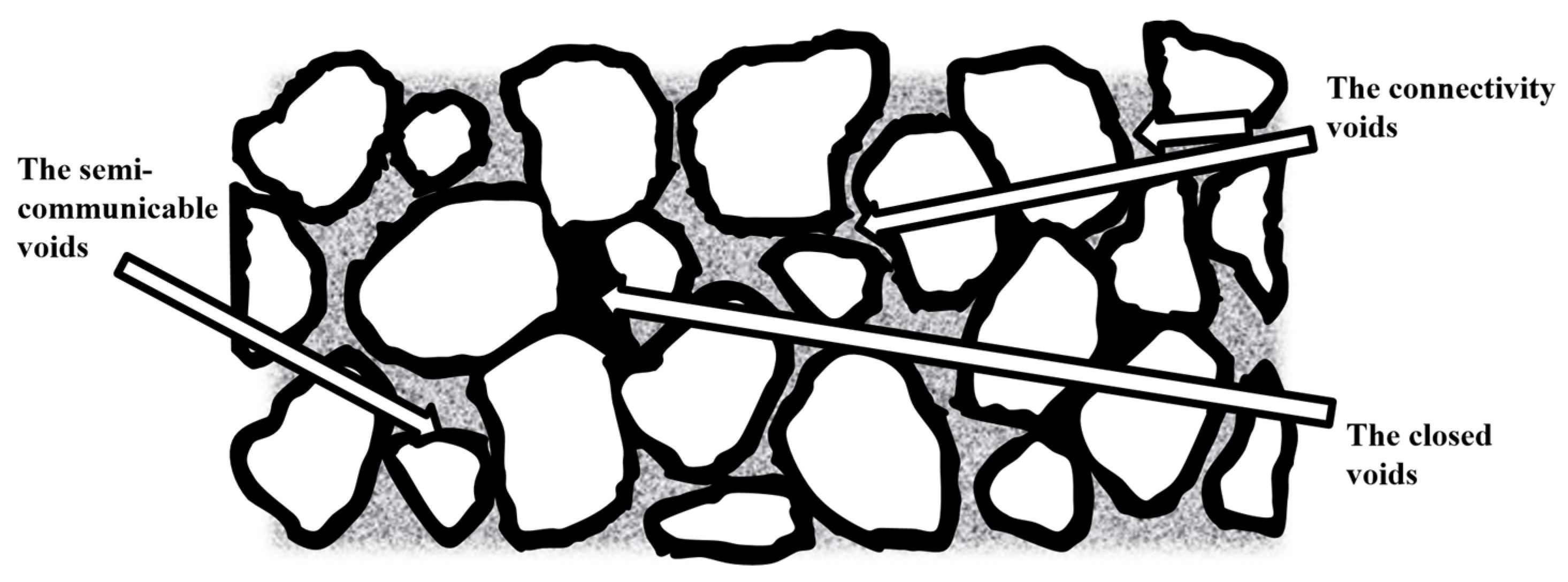

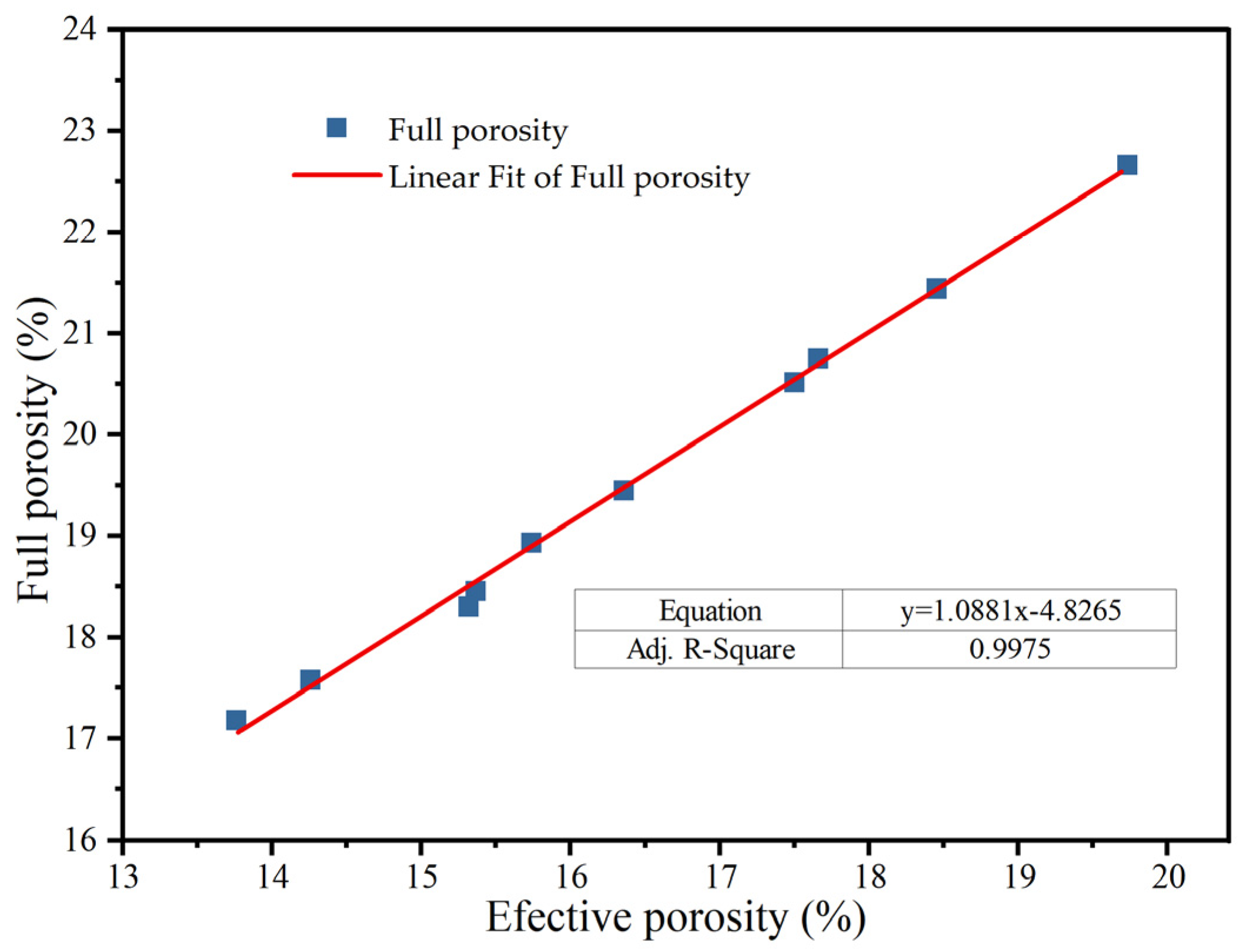

3.2.1. Relationship Between Full Porosity and Effective Porosity

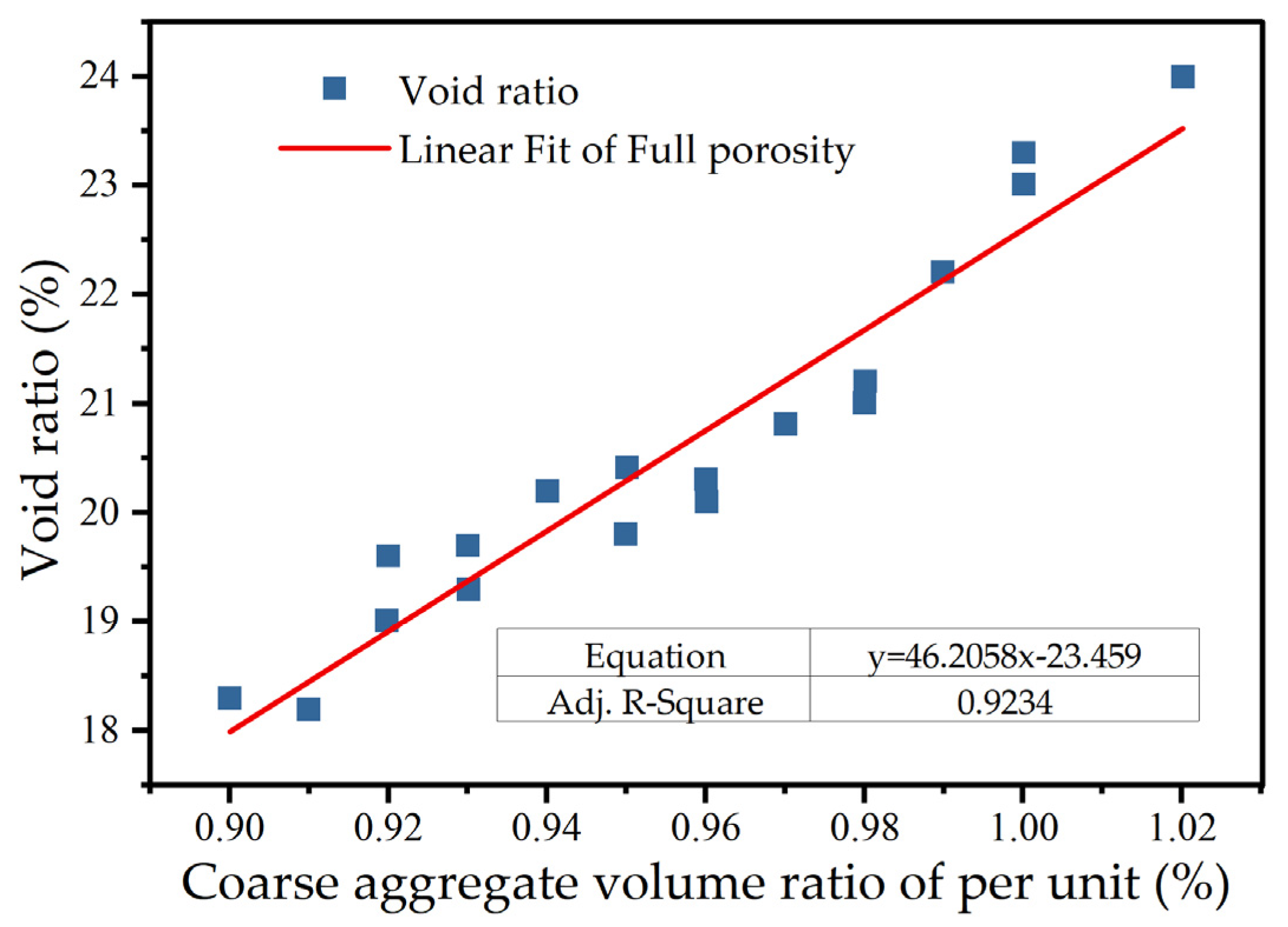

3.2.2. Relationship Between Full Porosity and Coarse Aggregate Content

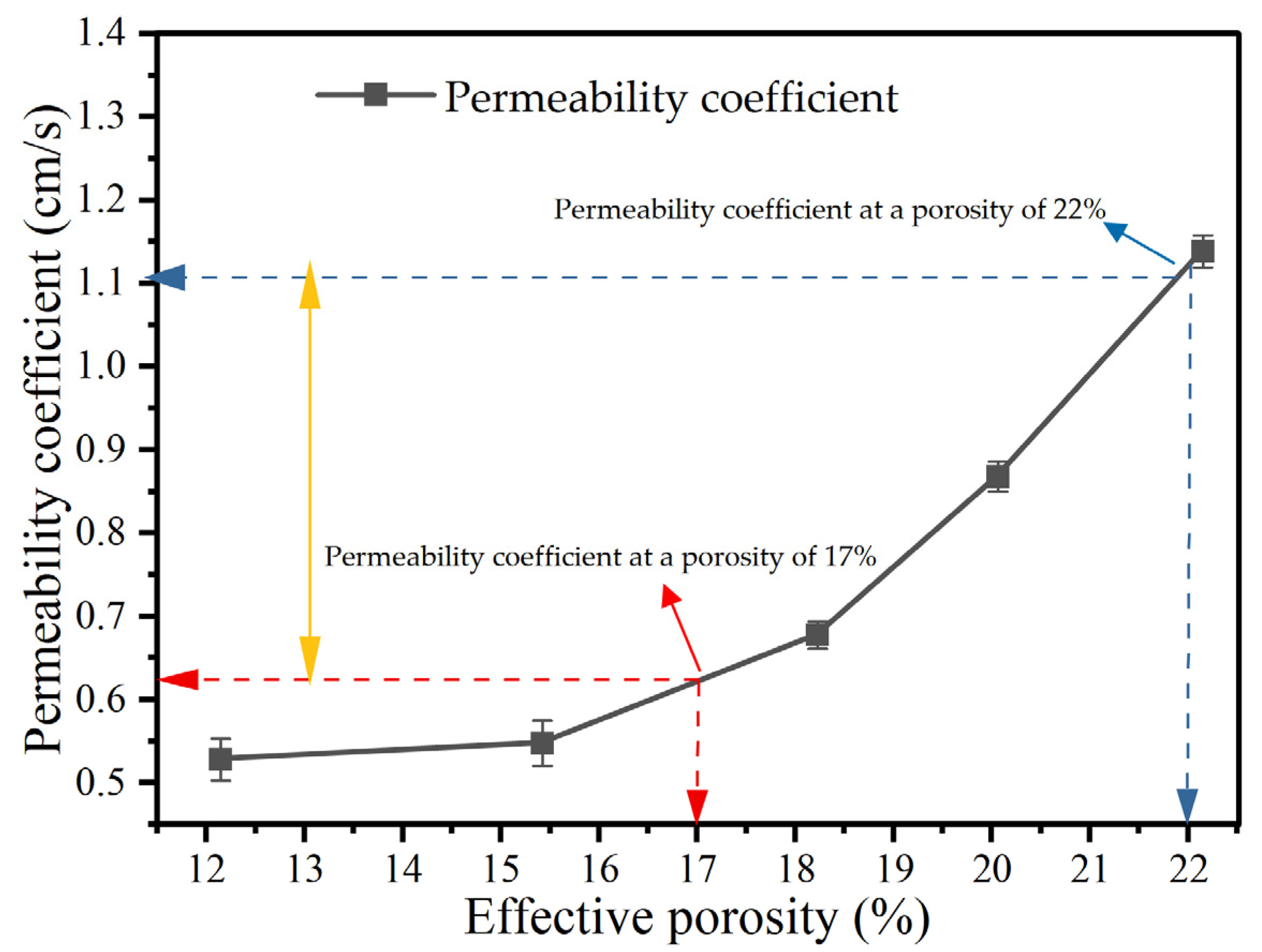

3.2.3. Permeability Coefficient

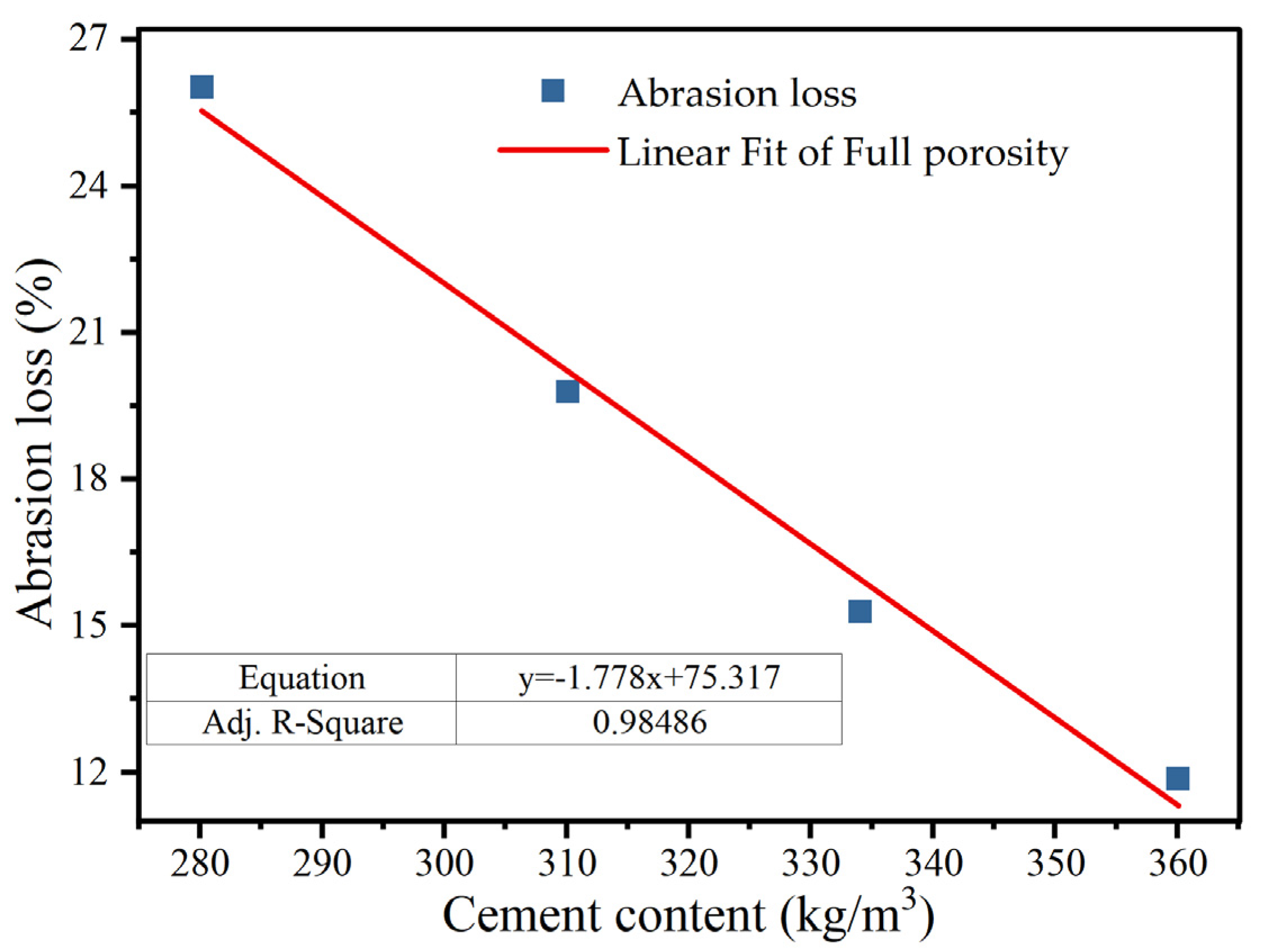

3.3. Anti-Wear Performance

3.4. Mix Design

3.4.1. Mix Design Indices

- (1)

- Strength

- (2)

- Porosity

3.4.2. Formula Regression Results

3.4.3. Procedure of Mix Design

- (1)

- Calculation of the initial mix proportion

- (2)

- Establishment of the Basic Mix Proportion

- (3)

- Determination of lab mix proportion

- (4)

- Conversion working mix proportion

4. Conclusions

- (1)

- The cement content and silica fume dosage exert significant influence on the internal pore structure and acoustic behavior of PCNRD. The average sound absorption coefficient exceeds 0.2, demonstrating that PCNRD provides excellent noise reduction performance suitable for pavement surface applications.

- (2)

- The permeability coefficient increases with the effective porosity, indicating that PCNRD exhibits superior drainage performance compared with asphalt concrete. The optimal effective porosity range is 17–23%, and the recommended upper pavement thickness is 8–10 cm.

- (3)

- The effective porosity shows a strong linear correlation with the total porosity and coarse aggregate content, offering a reliable quantitative basis for optimizing the mix design parameters for PCNRD.

- (4)

- Increasing the cement content effectively reduces the abrasion loss, which remains below 20%, indicating that PCNRD demonstrates good wear resistance suitable for heavy-traffic pavement applications.

- (5)

- Regression relationships between the strength and porosity were established, and a practical mix design procedure specifically for PCNRD was proposed using the strength and effective porosity as dual control indices, providing technical guidance for its broader engineering implementation.

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| PCNRD | porous concrete with noise reduction and drainage performance |

| W/C | water–cement ratio |

| LOI | loss on ignition |

References

- Adresi, M.; Yamani, A.; Tabarestani, M.K.; Rooholamini, H. A comprehensive review on pervious concrete. Constr. Build. Mater. 2023, 407, 133308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mikhailenko, P.; Piao, Z.Y.; Kakar, M.R.; Bueno, M.; Athari, S.; Pieren, R.; Heutschi, K.; Poulikakos, L. Low-Noise pavement technologies and evaluation techniques: A literature review. Int. J. Pavement Eng. 2022, 23, 1911–1934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mikhailenko, P.; Piao, Z.Y.; Kakar, M.R.; Bueno, M.; Poulikakos, L.D. Durability and surface properties of low-noise pavements with recycled concrete aggregates. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 319, 128788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahman, T.; Tajudin, A.N.; Wulaningtyas, A.H.; Andika, N.; Irawan, M.Z.; Widyatmoko, I. Recent developments in mitigating clogging in permeable pavements: A state-of-the-art review. Innov. Infrastruct. Solut. 2025, 10, 80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ziccarelli, M. Mix Design of Pervious Concrete in Geotechnical Engineering Applications. Materials 2025, 18, 1909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bilal, H.; Gao, X.J.; Cavaleri, L.; Khan, A.; Ren, M. Mechanical, Durability, and Microstructure Characterization of Pervious Concrete Incorporating Polypropylene Fibers and Fly Ash/Silica Fume. J. Compos. Sci. 2024, 8, 456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, X.X.; Zhou, H.; Bian, X.Y.; Chen, X.Y.; Ren, C.Q. Compressive Strength, Permeability, and Abrasion Resistance of Pervious Concrete Incorporating Recycled Aggregate. Sustainability 2024, 16, 4063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Claudino, G.O.; Rodrigues, G.G.O.; Rohden, A.B.; Mesquita, E.F.T.; Garcez, M.R. Mix design for pervious concrete based on the optimization of cement paste and granular skeleton to balance mechanical strength and permeability. Constr. Build. Mater. 2022, 347, 128620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.Y.; Sun, H.R.; Shui, X.T.; Chen, W.X. Experimental Investigation on the Properties of Sustainable Pervious Concrete with Different Aggregate Gradation. Int. J. Concr. Struct. Mater. 2023, 17, 64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amran, M.; Fediuk, R.; Murali, G.; Vatin, N.; Al-Fakih, A. Sound-Absorbing Acoustic Concretes: A Review. Sustainability 2021, 13, 10712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Odeyemi, S.O. Mechanical Properties of Granite-Gravel Porous Concrete. Int. J. Eng. Res. Afr. 2021, 57, 115–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodrigues, P.C.; Braga, N.T.D.; Junior, E.S.A.; Cordeiro, L.D.P.; de Melo, G.D.V. Effect of pore characteristics on the sound absorption of pervious concretes. Case Stud. Constr. Mater. 2022, 17, e01302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qu, G.L.; Zheng, M.L.; Lu, C.; Song, J.K.; Dong, D.Z.; Yuan, Y.M. Multi-objective optimization based on the RSM-MOPSO-GA algorithm and synergistic enhancement mechanism of high-performance porous concrete. J. Clean. Prod. 2025, 486, 144492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, M.L.; Chen, S.F.; Sheng, Y.P. Workability Evaluation Method and Index for Non-vibrated Porous Concrete. In Proceedings of the International Workshop on Energy and Environment in the Development of Sustainable Asphalt Pavements, Xi’an, China, 6–8 June 2010; pp. 526–529. [Google Scholar]

- Sathe, S.; Kolapkar, S.; Bhosale, A.; Dandin, S. Permeability Measurement of Pervious Concrete by Constant and Falling Head Methods: Influence of Aggregate Gradation and Cement-to-Aggregate Ratio. Pract. Period. Struct. Des. Constr. 2024, 29, 04024052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Xu, X.J. Predicting Multiple Properties of Pervious Concrete through the Gaussian Process Regression. Adv. Civ. Eng. Mater. 2021, 10, 56–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Debnath, B.; Sarkar, P.P. Characterization of pervious concrete using over burnt brick as coarse aggregate. Constr. Build. Mater. 2020, 242, 118154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pereira, L.; Godinho, L.; Branco, F.G.; Oliveira, P.D. A machine-learning based approach to estimate acoustic macroscopic parameters of porous concrete. Constr. Build. Mater. 2024, 426, 136075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.; Hong, J.; Pyo, S. Acoustic characteristics of sound absorbable high performance concrete. Appl. Acoust. 2018, 138, 171–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shamim, M.; Shakeel, H.; Naseer, S. Experimental Investigation of Effect of Pervious Concrete on Rigid Pavement in Pakistan. Civ. Eng. J. Staveb. Obz. 2023, 32, 83–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.Q.; Xie, J.G.; Yin, Z.Q. Study on sound absorption model of porous asphalt concrete based on permeability coefficient. Measurement 2025, 249, 117032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ni, T.Y.; Jiang, C.H.; Tai, H.X.; Zhao, G.Q. Experimental Study on Sound Absorption Property of Porous Concrete Pavement Layer. In Proceedings of the 3rd International Conference on Civil Engineering and Transportation (ICCET 2013), Kunming, China, 14–15 December 2014; pp. 238–241. [Google Scholar]

- Sánchez-Mendieta, C.; Galán, J.J.; Martinez-Lage, I. Physical and Hydraulic Properties of Porous Concrete. Sustainability 2021, 13, 10562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, F.T.; Yang, L.; Jiang, Y.Q. Optimum Mix Design and Correlation Analysis of Pervious Concrete. Materials 2025, 18, 4129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bohatkiewicz, J.; Halucha, M.; Debinski, M.K.; Jukowski, M.; Tabor, Z. Investigation of Acoustic Properties of Different Types of Low-Noise Road Surfacers under In Situ and Laboratory Conditions. Materials 2022, 15, 480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hou, F.J.; Qu, G.L.; Yan, Z.W.; Zheng, M.L.; Ma, Y.; Li, J.; Fan, F.F.; Zhang, J.G. Properties and relationships of porous concrete based on Griffith’s theory: Compressive strength, permeability coefficient, and porosity. Mater. Struct. 2024, 57, 52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kapicová, A.; Bíly, P.; Fládr, J.; Seps, K.; Chylík, R.; Trtík, T. Development of sound-absorbing pervious concrete for interior applications. J. Build. Eng. 2024, 85, 108697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, S.; Huang, K.A.; Chu, W.C.; Wang, W.S. Feasibility Study of Pervious Concrete with Ceramsite as Aggregate Considering Mechanical Properties, Permeability, and Durability. Materials 2023, 16, 5127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, J.W.; Liu, Z.X.; Xu, G.L.; Tian, Q.; Shen, W.G.; Li, B.W.; Chen, T. Mix design methods for pervious concrete based on the mesostructure: Progress, existing problems and recommendation for future improvement. Case Stud. Constr. Mater. 2022, 17, e01253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elizondo-Martinez, E.J.; Tataranni, P.; Rodriguez-Hernandez, J.; Castro-Fresno, D. Physical and Mechanical Characterization of Sustainable and Innovative Porous Concrete for Urban Pavements Containing Metakaolin. Sustainability 2020, 12, 4243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ewa, D.E.; Ukpata, J.O.; Otu, O.N.; Memon, Z.A.; Alaneme, G.U.; Milad, A. Scheffe’s Simplex Optimization of Flexural Strength of Quarry Dust and Sawdust Ash Pervious Concrete for Sustainable Pavement Construction. Materials 2023, 16, 598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Seeni, B.S.; Madasamy, M. Factors influencing performance of pervious concrete. Gradevinar 2021, 73, 1017–1030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shang, X.F. Mixing Ratio Design and Experimental Studies of High-Performance Porous Concrete Strength. In Proceedings of the 3rd International Conference on Applied Engineering, Wuhan, China, 22–25 April 2016; pp. 1099–1104. [Google Scholar]

- Lian, C.; Zhuge, Y. Optimum mix design of enhanced permeable concrete—An experimental investigation. Constr. Build. Mater. 2010, 24, 2664–2671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anburuvel, A.; Subramaniam, D.N. A Novel Multi-variable Model for the Estimation of Compressive Strength of Pervious Concrete. Int. J. Pavement Res. Technol. 2024, 17, 720–731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Subramaniam, D.N.; Anburuvel, A. Performance Analysis Relevant to Primary Design Parameters of Pervious Concrete: A Critical Review. Transp. Res. Rec. 2025, 2679, 1183–1208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elizondo-Martínez, E.J.; Andrés-Valeri, V.C.; Jato-Espino, D.; Rodriguez-Hernandez, J. Review of porous concrete as multifunctional and sustainable pavement. J. Build. Eng. 2020, 27, 100967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holmes, N.; Kelliher, D.; Tyrer, M. Simulating cement hydration using HYDCEM. Constr. Build. Mater. 2020, 239, 117811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harrer, R. Cement and the Hydration. Chem. Unserer Zeit 2014, 48, 406–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, Z.; Yang, H.M.; Liu, M.Y. Hydration mechanism of sulphoaluminate cement. J. Wuhan Univ. Technol. Mater. Sci. Ed. 2014, 29, 70–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doyle, J.D.; Howard, I.L. Characterization of Dense-Graded Asphalt With the Cantabro Test. J. Test. Eval. 2016, 44, 77–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Easterling, J.; Howard, I.L.; Lewis, J.V.; Sullivan, W.G. Advancing Field Aging Simulation Methods for Cantabro Abrasion Loss Testing. Transp. Res. Rec. 2024, 2678, 963–979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyu, Q.; Dai, P.F.; Chen, A.G. Correlations among physical properties of pervious concrete with different aggregate sizes and mix proportions. Road Mater. Pavement Des. 2024, 25, 2747–2771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anbazhagan, P.; Uday, A.; Moustafa, S.S.R.; Al-Arifi, N.S.N. Soil Void Ratio Correlation with Shear Wave Velocities and SPT N Values for Indo-Gangetic Basin. J. Geol. Soc. India 2017, 89, 398–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sha, F.; Zhang, S.M.; Sun, X.C.; Fan, G.X.; Diao, Y.H.; Duan, X.F.; Qiao, A.L.; Wang, H. Mechanical performance and pore characteristics of pervious concrete. Case Stud. Constr. Mater. 2024, 21, e03674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, F.; Li, Z.; Liu, B.W.; Yu, Z.H.; Li, Z.T.; Zhu, M.Y.; Wang, Y.J.; Ding, X.Z. Experimental and Numerical Investigations on the Influences of Target Porosity and w/c Ratio on Strength and Permeability of Pervious Concrete. Materials 2025, 18, 3951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Li, L.T.; Deng, Z.B.; Liu, P.G.; Wei, D.B. Analysis of the Permeability Capacity and Engineering Performance of Porous Asphalt Concrete. Materials 2025, 18, 4200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- China Highway Consultants Co., Ltd. Specifications for Design of Highway Cement Concrete Pavement; China Communication Press: Beijing, China, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Mondal, S.; Biligiri, K.P. Crumb Rubber and Silica Fume Inclusions in Pervious Concrete Pavement Systems: Evaluation of Hydrological, Functional, and Structural Properties. J. Test. Eval. 2018, 46, 892–905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kotwal, A.; Deb, P. Evaluation of mechanical properties of silica fume mixed with pervious concrete pavement. Innov. Infrastruct. Solut. 2023, 8, 270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yusuf, I.T.; Jimoh, Y.A.; Salami, W.A. An appropriate relationship between flexural strength and compressive strength of palm kernel shell concrete. Alex. Eng. J. 2016, 55, 1553–1562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García Beltrán, M. Estudio de Durabilidad y de Comportamiento Mecánico en Hormigones y Materiales Tratados con Cemento, Aplicando Residuos Industriales y Áridos Reciclados. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Cordoba, Cordoba, Spain, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Amudhavalli, N.; Poovizhiselvi, M. Relationship between compressive strength and flexural strength of polyester fiber reinforced concrete. Int. J. Eng. Trends Technol. 2017, 45, 158–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamoodi, A.Z.; Kadim, J.A.; Chkheiwer, A.H. Properties of pervious concrete made from graded and single size crushed coarse aggregate. Period. Eng. Nat. Sci. 2021, 9, 361–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez-Mendieta, C.; Galán-Díaz, J.J.; Martinez-Lage, I. Relationships between density, porosity, compressive strength and permeability in porous concretes: Optimization of properties through control of the water-cement ratio and aggregate type. J. Build. Eng. 2024, 97, 110858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Materials | Properties | Dosage |

|---|---|---|

| Cement | Ordinary Portland cement (P.O.42.5). Density: 3.1 g/cm3 28-day compressive strength: 53.5 MPa 28-day bending flexural strength: 8.7 MPa | 334 kg/m3 |

| Coarse aggregate | Particle size: 5–10 mm, diorite. Apparent density: 2.927 g/cm3 Particle size: 10–16 mm, diorite. Apparent density: 2.924 g/cm3 The result of screening is listed in Table 2 | 1731 kg/m3 |

| Silica fume | Average particle size: 0.1~0.15 μm Specific surface: 15~27 m2/g The chemical component of silica fume is listed in Table 3 | 6% (relative to the cement content) |

| Water-reducing agent | High-efficiency water reduction | 1.5% (relative to the cement content) |

| Grading (mm) | 16 | 13.2 | 9.5 | 4.75 | 2.36 | 1.18 | 0.6 | 0.3 | 0.15 | 0.075 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 10–16 | 100.00 | 87.93 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| 5–10 | 100.00 | 100.00 | 99.30 | 7.70 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| SiO2 | Al2O3 | CaO | MgO | SO3 | Fe2O3 | Na2O | K2O | LOI (Loss on Ignition) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 90 | 0.4 | 0.8 | 0.6 | — | 0.3 | 0.3 | 0.8 | 3.8 |

| Cement Type | CaO | SiO2 | Al2O3 | Fe2O3 | MgO | SO3 | Na2O | K2O | LOI (Loss on Ignition) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| P.O.42.5 | 63.51 | 20.63 | 5.09 | 4.28 | 1.47 | 2.26 | — | — | 1.3 |

| Kind of Test | Specimen Size (mm) | Specimen Number for Each Testing Level | Variable | Notes | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Standard specimen molding test | 150 × 150 × 150 | - | - | At 28 days | |

| Sound absorption test | Φ 95 × 80 | 11 × 1 | Silica fume content (wt.%) | 0 | Frequency is also the variable At 28 days |

| 3 | |||||

| 6 | |||||

| 9 | |||||

| Cement content (kg/m3) | 285 | ||||

| 310 | |||||

| 334 | |||||

| 360 | |||||

| Thickness (mm) | 60 | ||||

| 80 | |||||

| 100 | |||||

| Permeability test | 150 × 150 × 150 | 5 × 1 | Target void ratio (%) | 12 | At 28 days |

| 15 | |||||

| 18 | |||||

| 20 | |||||

| 25 | |||||

| Wear resistance test | Φ 101.6 × 63.5 | 4 × 3 | Cement content (kg/m3) | 280 | At 28 days |

| 310 | |||||

| 334 | |||||

| 360 | |||||

| Kind of Test | Factors | Conditions |

|---|---|---|

| Standard specimen molding test | Water–cement ratio (W/C) | 0.3 |

| Molding method | Upper vibration molding | |

| Permeability test | Test temperature | 10 °C |

| W/C | Workability State | Estimation Scale |

|---|---|---|

| Small | Complete disintegration; aggregates are loose and surface lacks luster | A |

| ↓ | Partial disintegration; aggregates dull, no surface sheen | B |

| Specimen retains the container’s shape; aggregates exhibit surface sheen | C | |

| Specimen collapses slowly; aggregate surfaces fully glossy | D | |

| Large | Specimen collapses immediately; slurry leakage observed | E |

| Level | Factor | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| A Water–Cement Radio | B Cement Content (kg/m3) | C Silica Fume Content (%) | D Strength Grade of Cement (MPa) | |

| 1 | 0.28 | 285 | 0 | 32.5 |

| 2 | 0.30 | 310 | 3 | 42.5 |

| 3 | 0.33 | 334 | 6 | 52.5 |

| 4 | 0.36 | 360 | 9 | — |

| Serial Number | Test Number | Mixture Ratio | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A | B (kg/m3) | C (%) | D (MPa) | ||

| 1-1 | 1 | 0.28 | 334 | 6 | 52.5 |

| 1-2 | 2 | 0.28 | 285 | 0 | 42.5 |

| 1-3 | 3 | 0.28 | 334 | 9 | 32.5 |

| 2-1 | 4 | 0.30 | 285 | 3 | 32.5 |

| 2-2 | 5 | 0.30 | 334 | 0 | 52.5 |

| 2-3 | 6 | 0.30 | 285 | 6 | 42.5 |

| 3-1 | 7 | 0.33 | 360 | 3 | 42.5 |

| 3-2 | 8 | 0.33 | 310 | 9 | 32.5 |

| 3-3 | 9 | 0.33 | 360 | 6 | 52.5 |

| 4-1 | 10 | 0.36 | 310 | 0 | 52.5 |

| 4-2 | 11 | 0.36 | 360 | 9 | 42.5 |

| 4-3 | 12 | 0.36 | 310 | 3 | 32.5 |

| Mix Proportion | Silica Fume Content (%) | Cement Content (kg/m3) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 3 | 6 | 9 | 285 | 310 | 334 | 360 | |

| Sum average | 0.35 | 0.23 | 0.36 | 0.28 | 0.33 | 0.28 | 0.28 | 0.33 |

| Arithmetical mean | 0.34 | 0.27 | 0.30 | 0.22 | 0.35 | 0.3 | 0.28 | 0.31 |

| Void ratio (%) | 23.4 | 21.3 | 19.8 | 17.3 | 22.1 | 20.5 | 18.6 | 16.3 |

| Traffic Classification | Ponderosity, Extra Heavy | Heavy | Medium | Light |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Flexural strength standard values (MPa) | ≥5.0 | ≥5.0 | 4.5 | 4.0 |

| Traffic Classification | Ponderosity, Extra Heavy | Heavy | Medium | Light |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| The flexural strength standard values of PCNRD (MPa) | ≥4.5 | ≥4 | 3.5 | 3.5 |

| The compressive strength standard values of PCNRD (MPa) | ≥32 | ≥27 | 21 | 21 |

| Serial Number | Test Number | 7 d Compressive Strength (MPa) | 28 d Flexural Strength (MPa) | Effective Porosity (MPa) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1-1 | 1 | 17.5 | 3.23 | 19.9 |

| 1-2 | 2 | 12.8 | 2.65 | 22.4 |

| 1-3 | 3 | 18.3 | 3.46 | 18.3 |

| 2-1 | 4 | 13.1 | 2.80 | 22.2 |

| 2-2 | 5 | 19.1 | 3.95 | 18.9 |

| 2-3 | 6 | 16.7 | 3.28 | 20.4 |

| 3-1 | 7 | 21.5 | 4.30 | 17.1 |

| 3-2 | 8 | 19.6 | 4.16 | 17.9 |

| 3-3 | 9 | 22.0 | 5.27 | 18.9 |

| 4-1 | 10 | 18.4 | 4.24 | 18.9 |

| 4-2 | 11 | 17.5 | 3.59 | 19.0 |

| 4-3 | 12 | 14.4 | 2.95 | 21.1 |

| Dependent Variable | Independent Variable | Regression Equation | Serial Number |

|---|---|---|---|

| w/c, c, s, d | (16) | ||

| w/c, s, d | (17) | ||

| c, s, d | (18) | ||

| c, s | (19) | ||

| w/c, c, s, d | (20) | ||

| w/c, s, d | (21) | ||

| w/c, d | (22) | ||

| w/c, c, s, d | (23) | ||

| w/c, s, d | (24) | ||

| c, s | (25) |

| Items | Objective Value | Adjustment Method |

|---|---|---|

| Void ratio | Pc | Exceed objective value and reduce unit volume ratio of coarse aggregate. Be inferior to objective value and increase unit volume ratio of coarse aggregate. |

| State grade of workability | C | Grade A and B is to increase water–cement ratio; Grade C and D is to reduce the water–cement ratio. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Xiu, Y.; Hu, M.; Zhang, C.; Wu, S.; Zheng, M.; Xu, J.; Song, X. Surface Performance Evaluation and Mix Design of Porous Concrete with Noise Reduction and Drainage Performance. Materials 2025, 18, 5433. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma18235433

Xiu Y, Hu M, Zhang C, Wu S, Zheng M, Xu J, Song X. Surface Performance Evaluation and Mix Design of Porous Concrete with Noise Reduction and Drainage Performance. Materials. 2025; 18(23):5433. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma18235433

Chicago/Turabian StyleXiu, Yijun, Miao Hu, Chenlong Zhang, Shaoqi Wu, Mulian Zheng, Jinghan Xu, and Xinghan Song. 2025. "Surface Performance Evaluation and Mix Design of Porous Concrete with Noise Reduction and Drainage Performance" Materials 18, no. 23: 5433. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma18235433

APA StyleXiu, Y., Hu, M., Zhang, C., Wu, S., Zheng, M., Xu, J., & Song, X. (2025). Surface Performance Evaluation and Mix Design of Porous Concrete with Noise Reduction and Drainage Performance. Materials, 18(23), 5433. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma18235433