Numerical Simulation of the Post-Tensioned Beams Behaviour Under Impulse Forces Loading

Abstract

1. Introduction

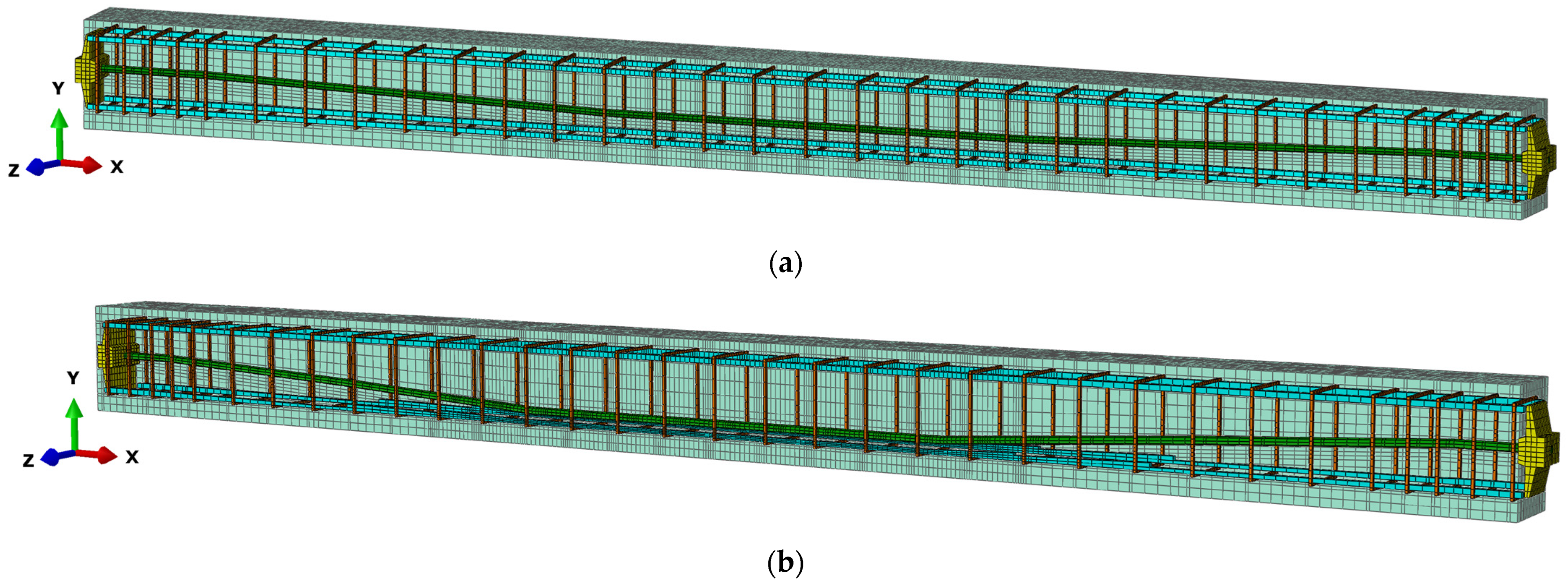

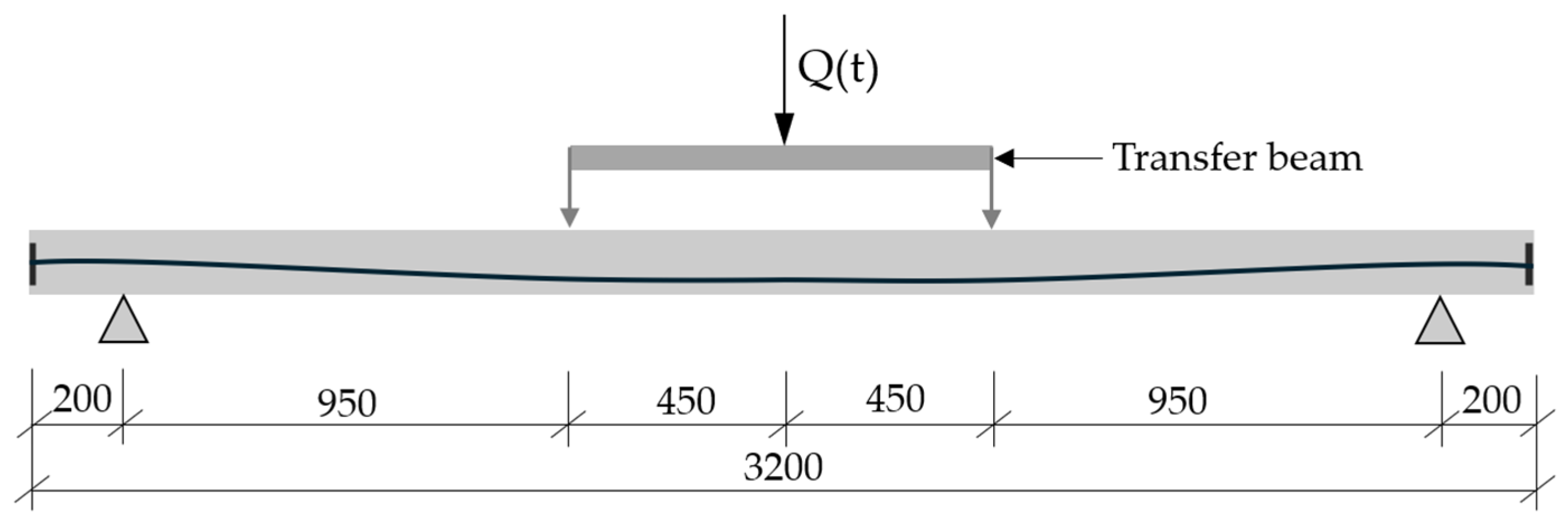

2. Numerical Models of Post-Tensioned Concrete Beams

2.1. Geometry of Post-Tensioned Concrete Beams

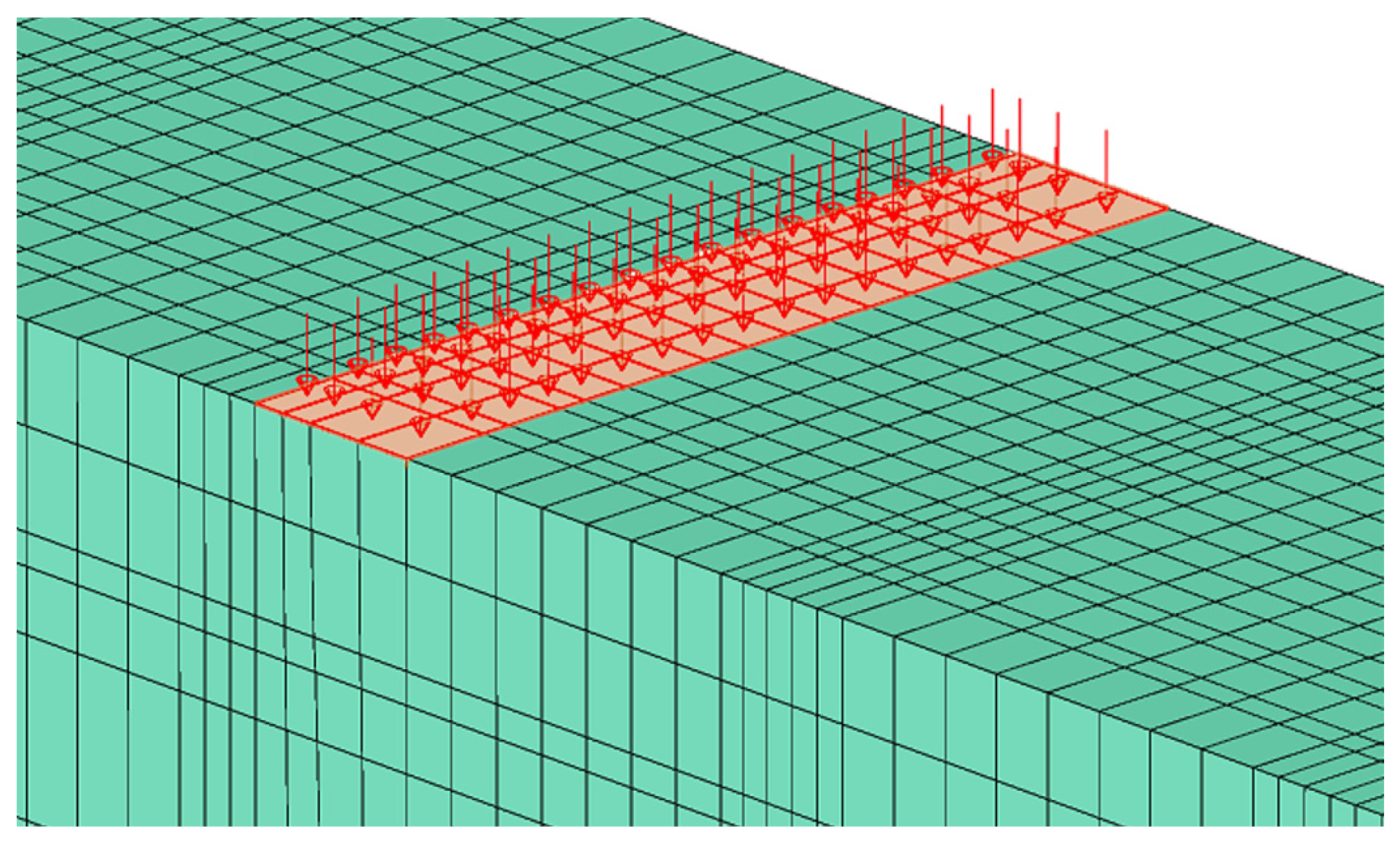

2.2. Numerical Model Description

2.2.1. Contact Parameters

2.2.2. Calibration of Numerical Models of Beams in Static Tests

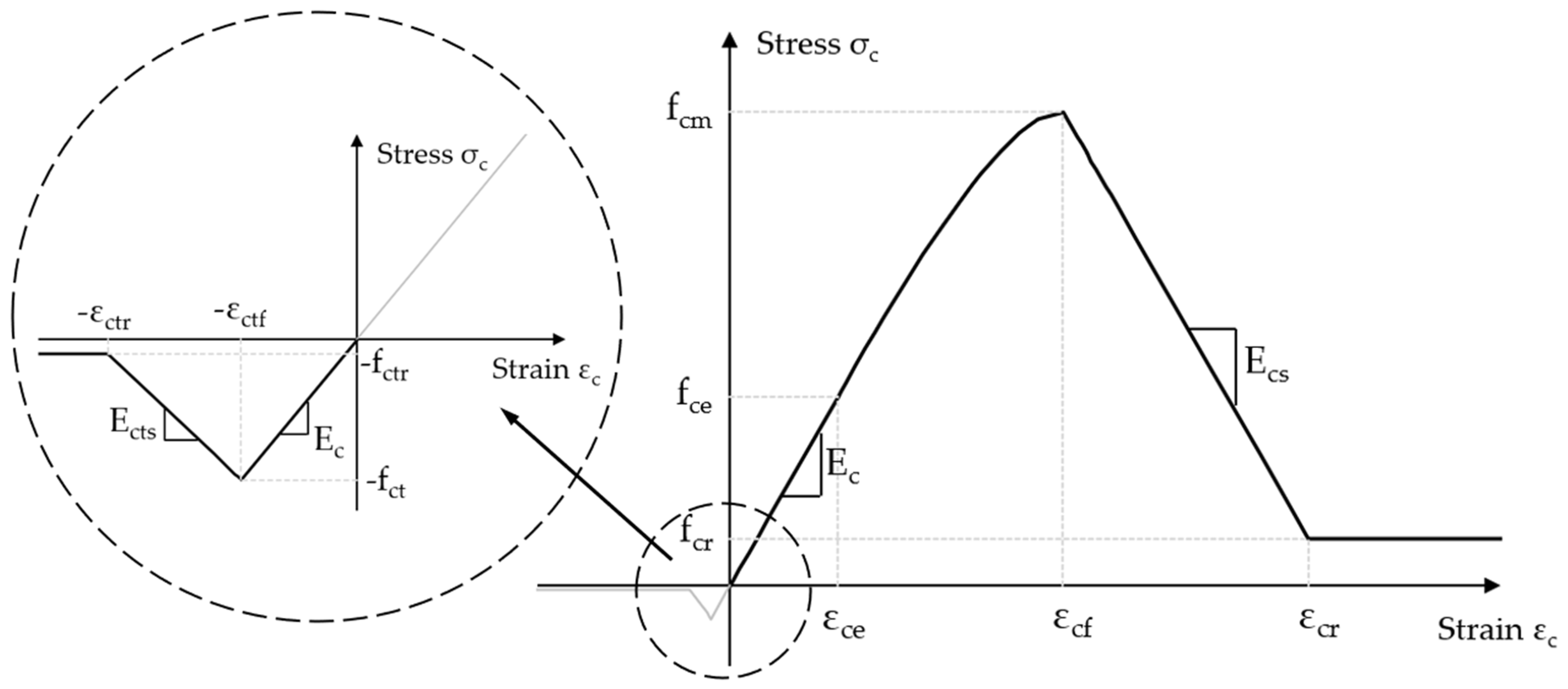

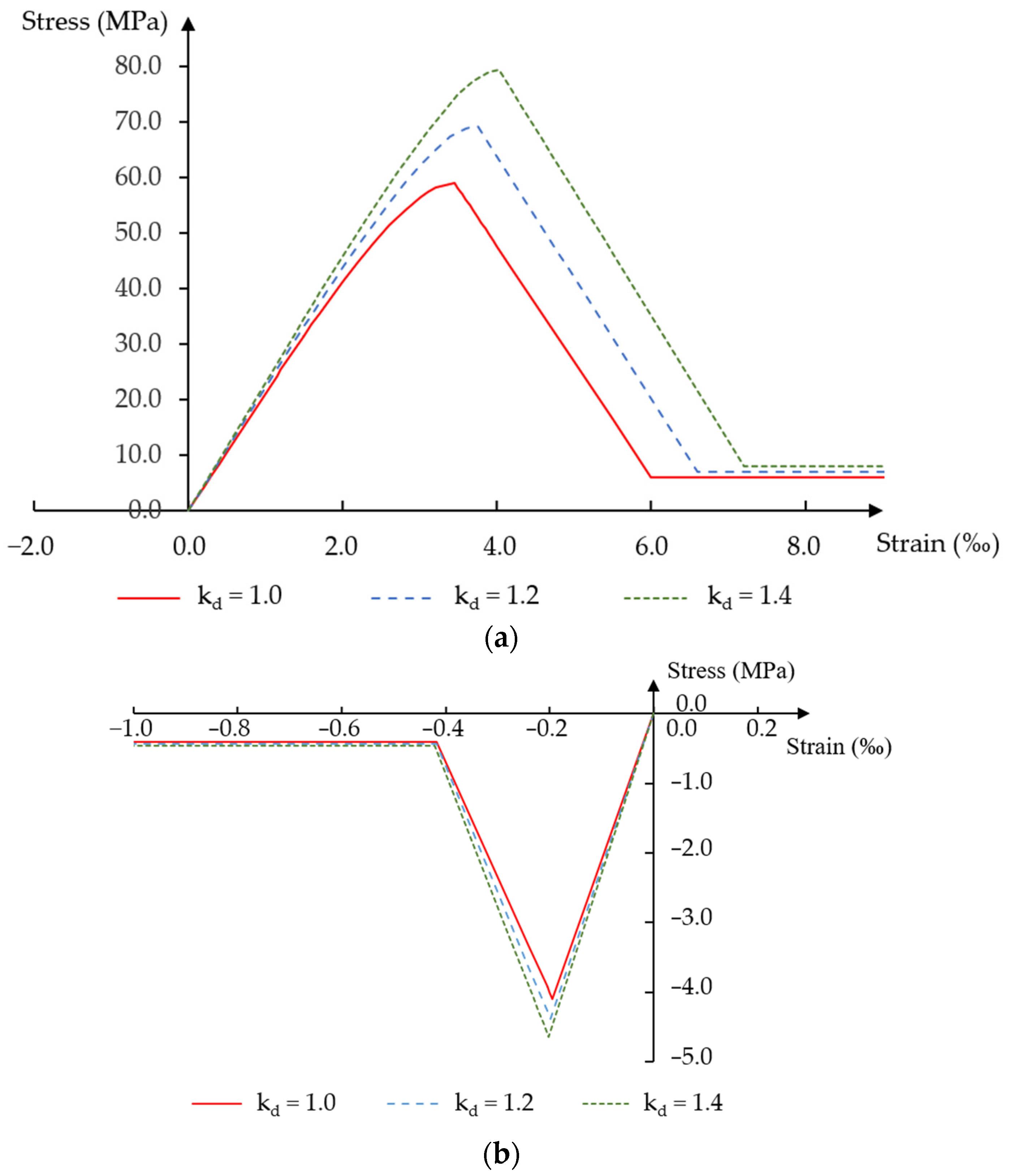

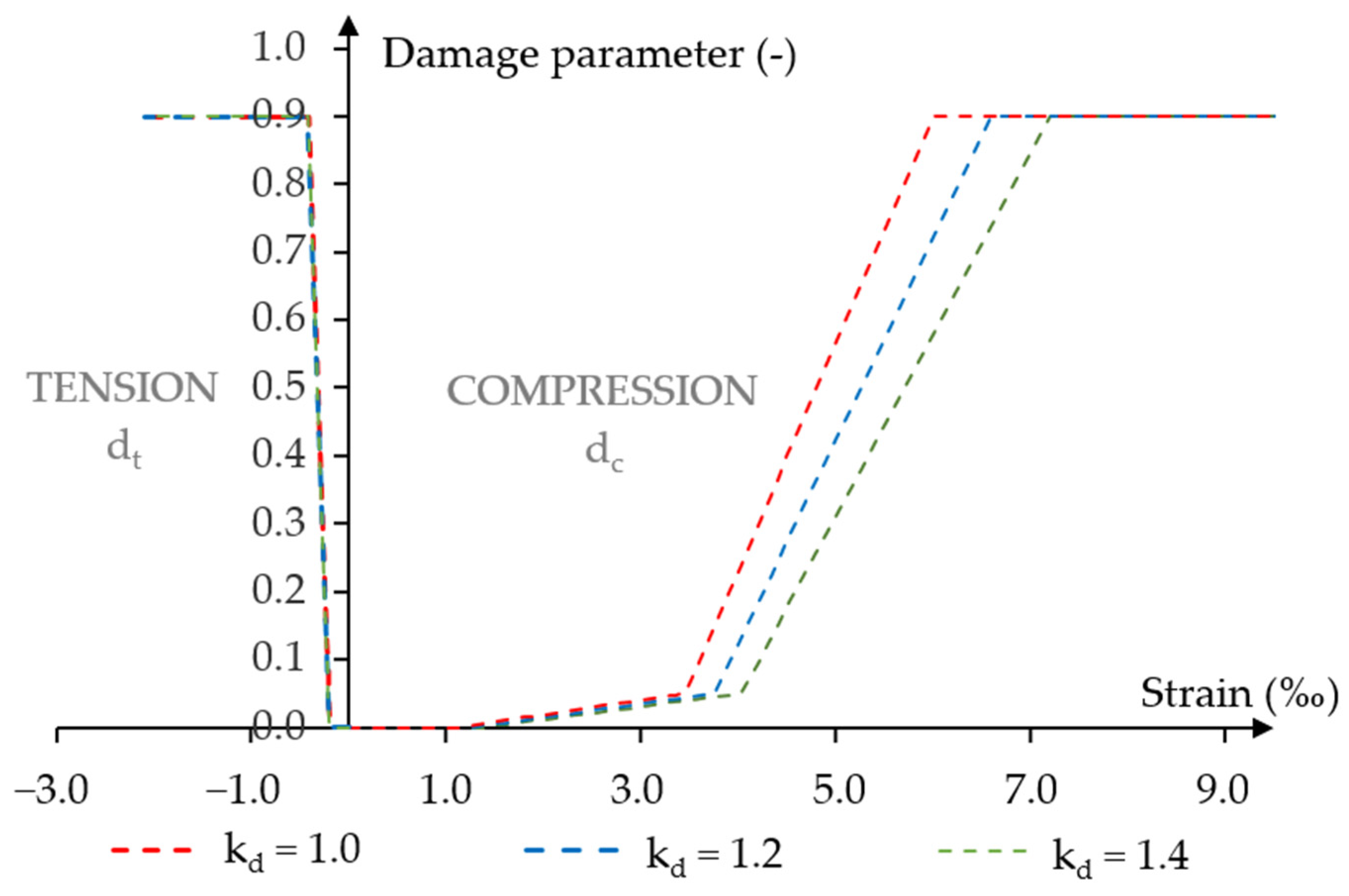

2.3. Materials Model

2.3.1. Concrete

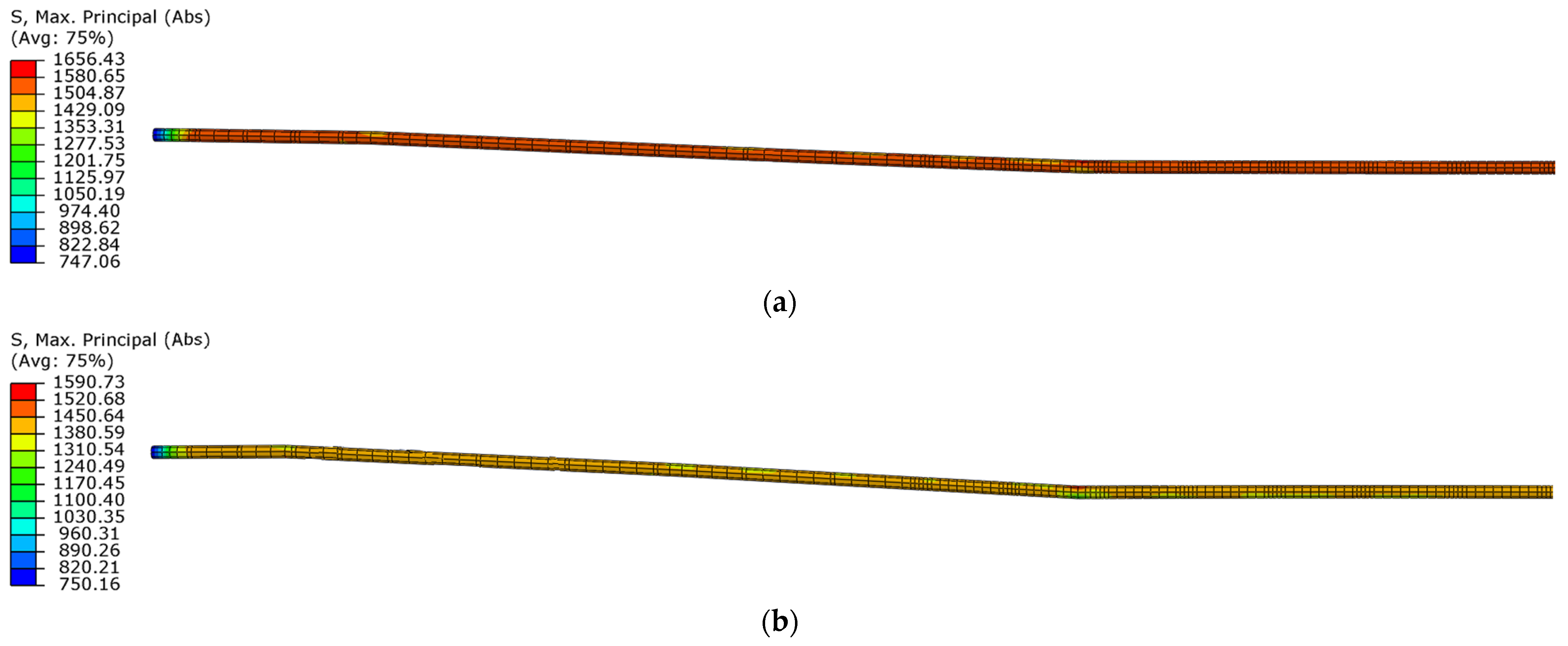

2.3.2. Steel Elements

- (1)

- isotropic hardening dependent on the effective plastic strain,

- (2)

- dynamic hardening dependent on the strain rate,

- (3)

- temperature.

- —initial, static yield strength: ,

- —plastic hardening modulus,

- —effective plastic strain,

- —plastic hardening parameter,

- —dynamic hardening parameter due to strain rate,

- —effective plastic strain rate,

- —reference strain for which the dynamic yield strength is equal to the static yield strength: ,

- —dimensionless thermal coefficient,

- —thermal softening parameter.

- —current temperature at which the tests were performed,

- —transition temperature at or below which the measured material parameters must be determined,

- —melting temperature at which the material will melt or no longer demonstrate shear capacity.

- —static yield strength,

- —elastic-viscoplastic part of the strain rate,

- —viscosity coefficient of steel,

- —material coefficient.

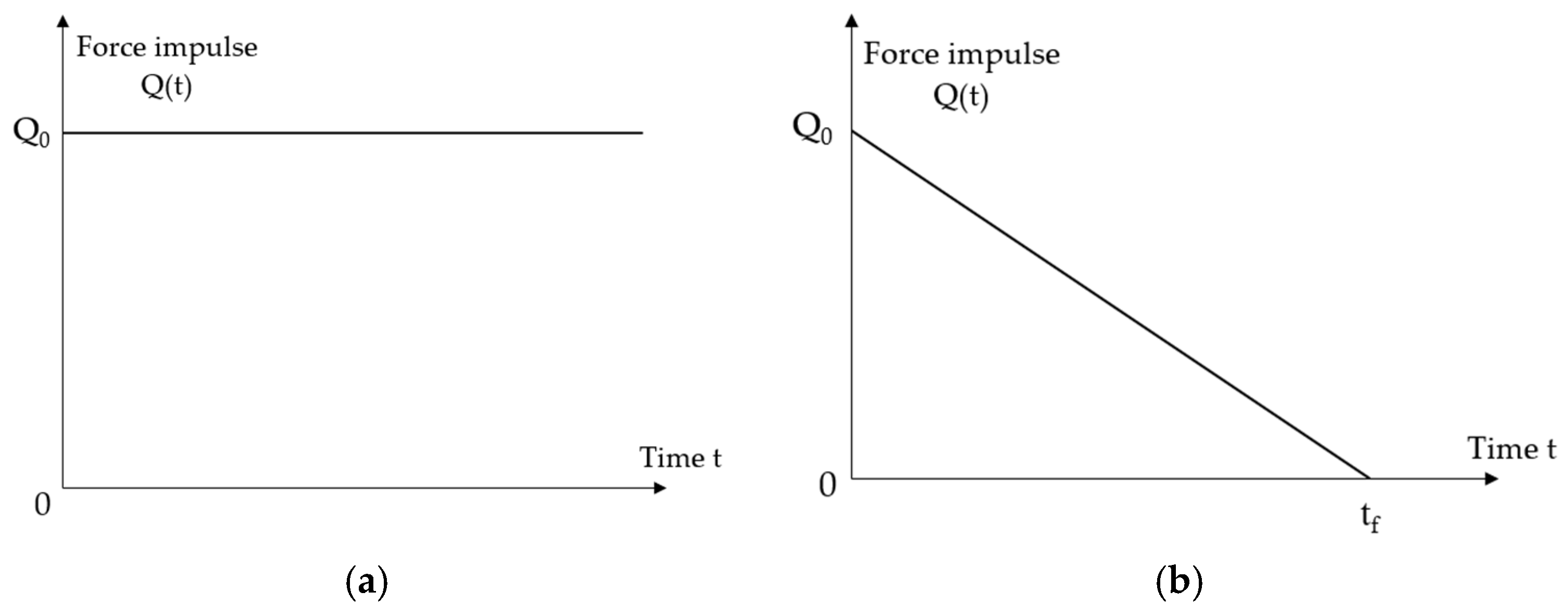

2.4. Methodology for Determining External Load in Dynamic Problems

- (1)

- constant force impulse over an infinite period (Figure 5a):

- (2)

- short-term force impulse that changes linearly over a finite period (Figure 5b):where

- —initial value of the force impulse,

- —static load capacity of the analysed beams [20],

- —dynamic load coefficient,

- —dynamic load capacity factor of beams: ,

- —dynamic load duration.

2.5. Prestressing Force Value

2.6. Boundary Conditions

2.7. Parameters of the Numerical Calculation Procedure

2.7.1. Dynamic Equilibrium Equation for Dynamic Problems Analysis

2.7.2. Selection of the Damping Parameter in Solving Dynamic Problems

3. Results of Numerical Research of Dynamically Loaded PT Beams

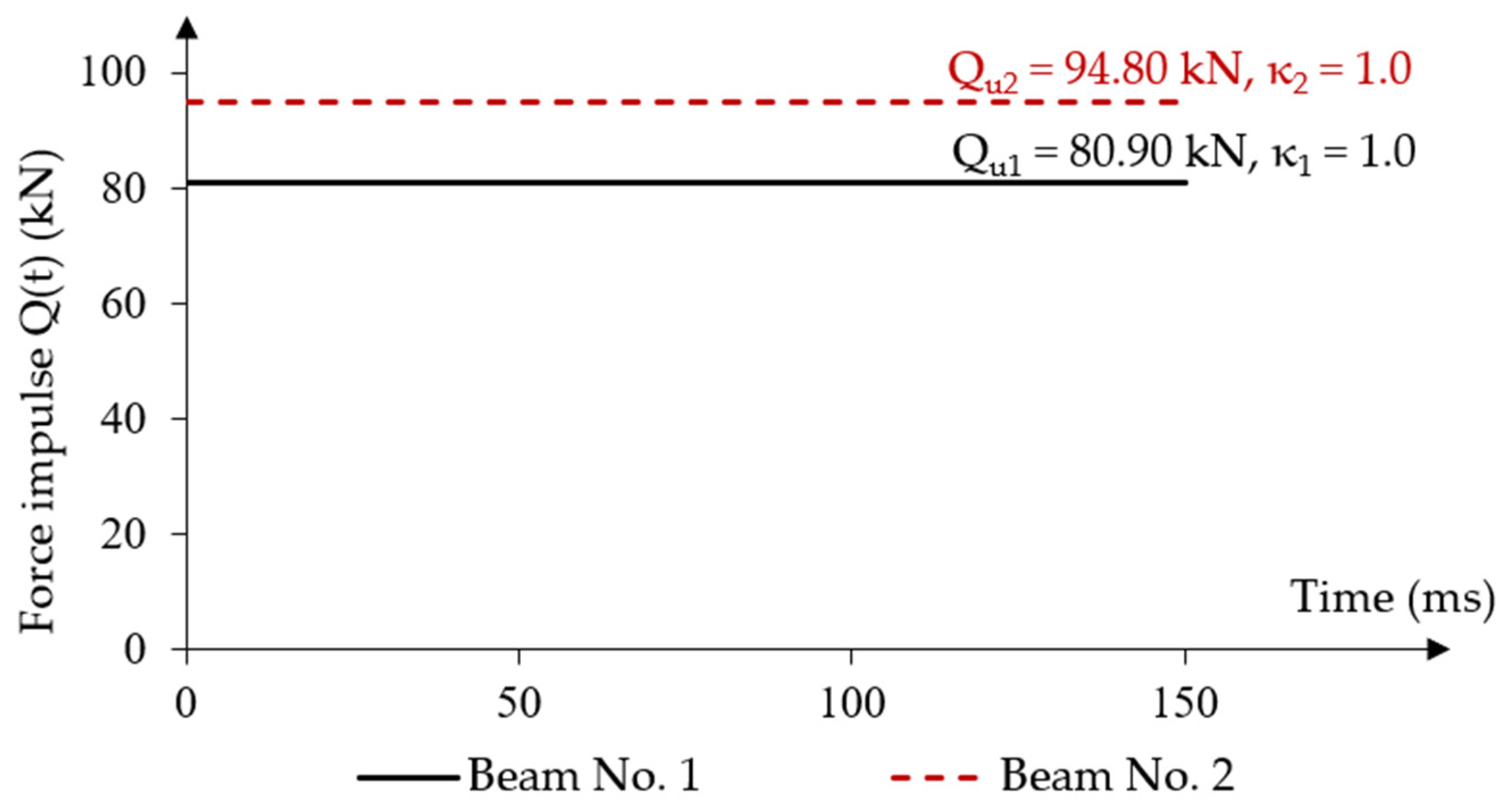

3.1. The Effect of a Constant Impulsive Force over Time

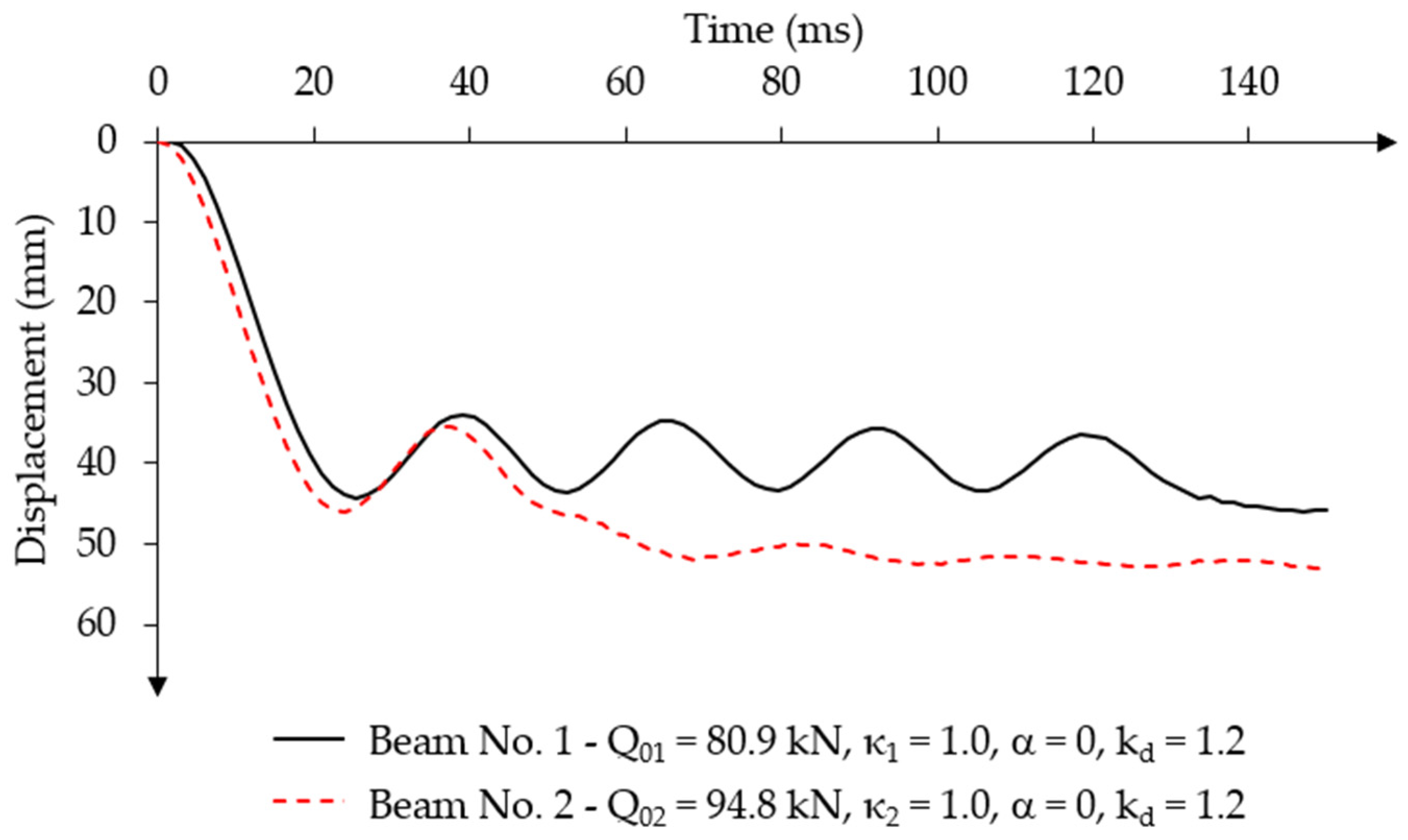

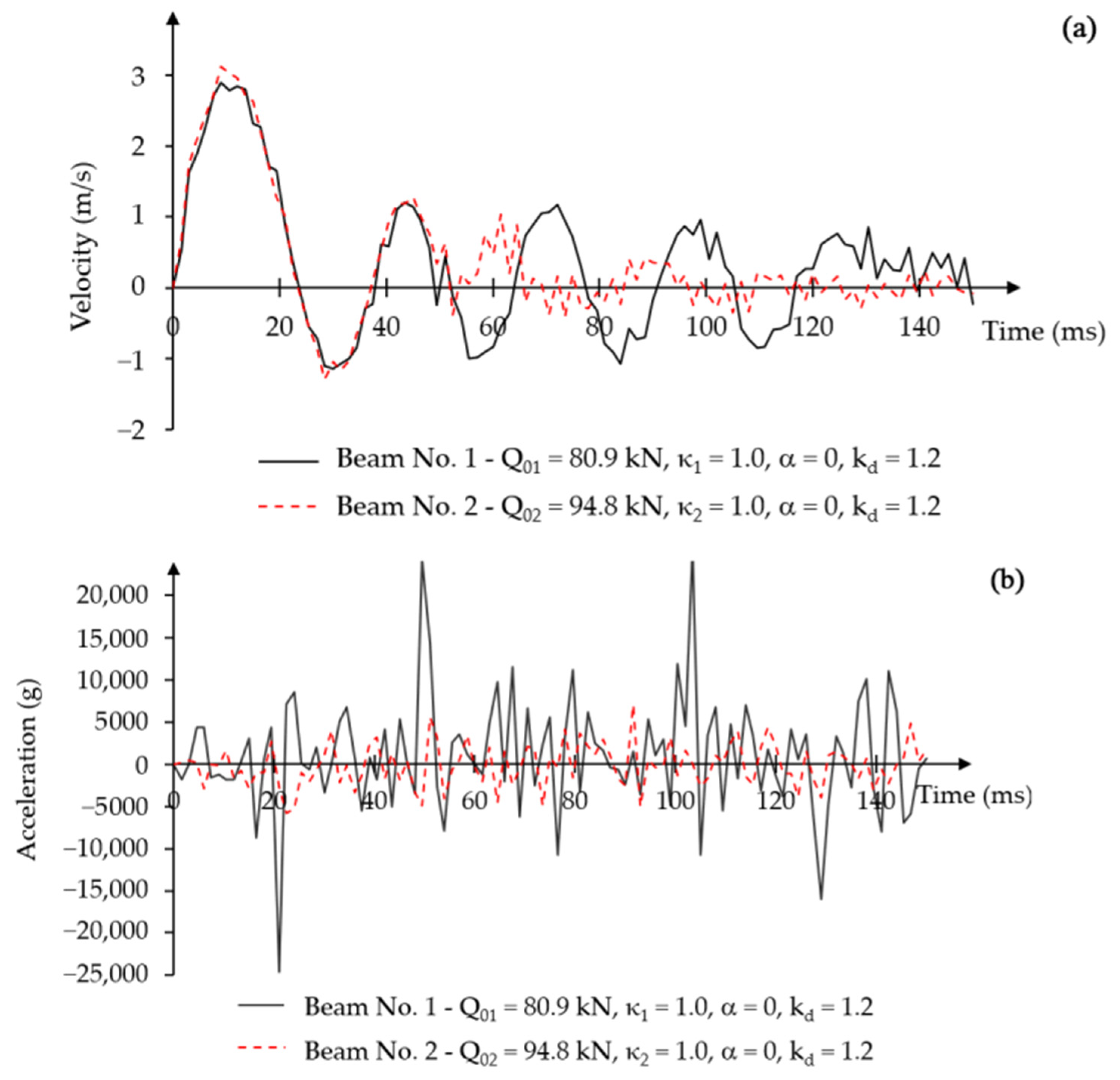

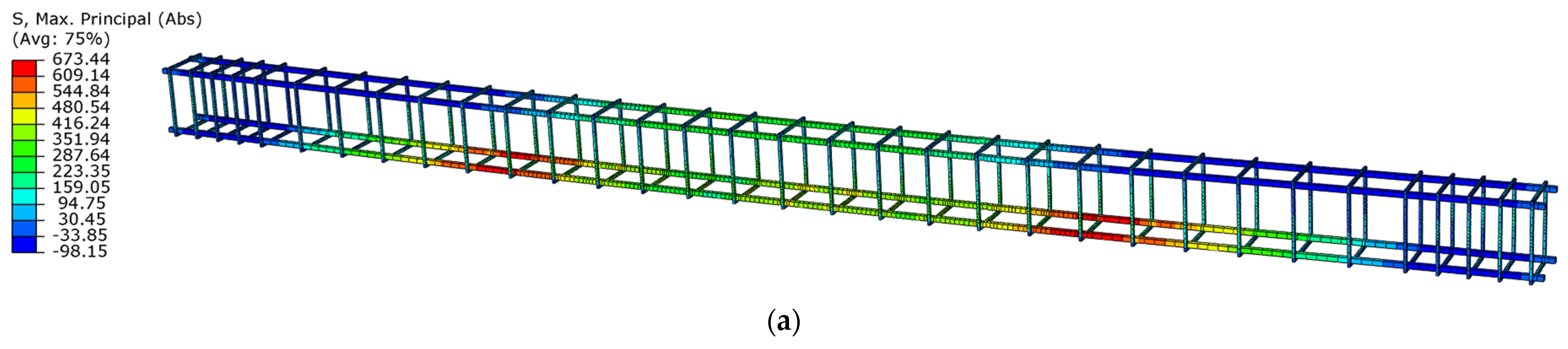

3.1.1. Determining the Dynamic Load Capacity of Post-Tensioned Beams

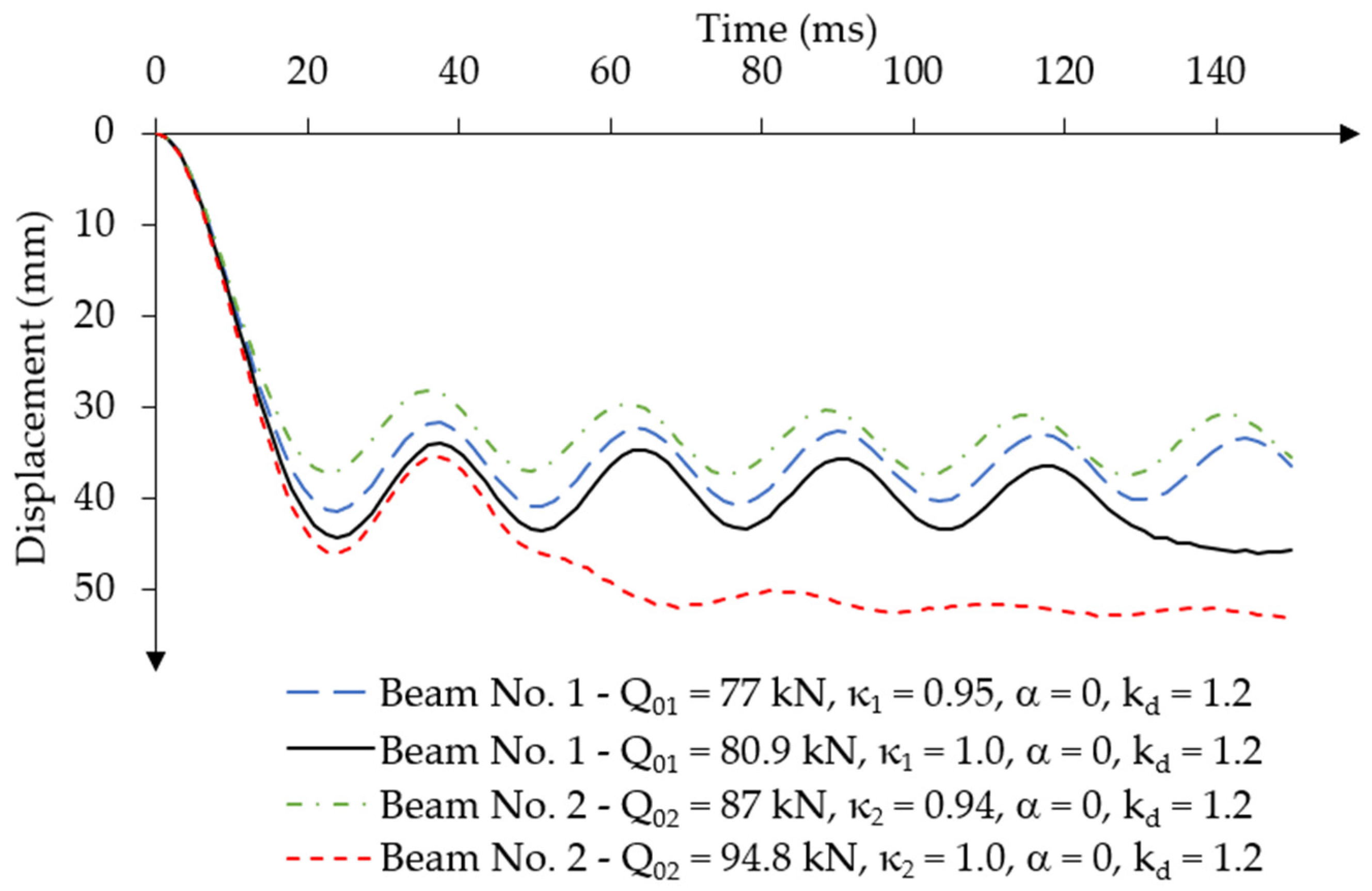

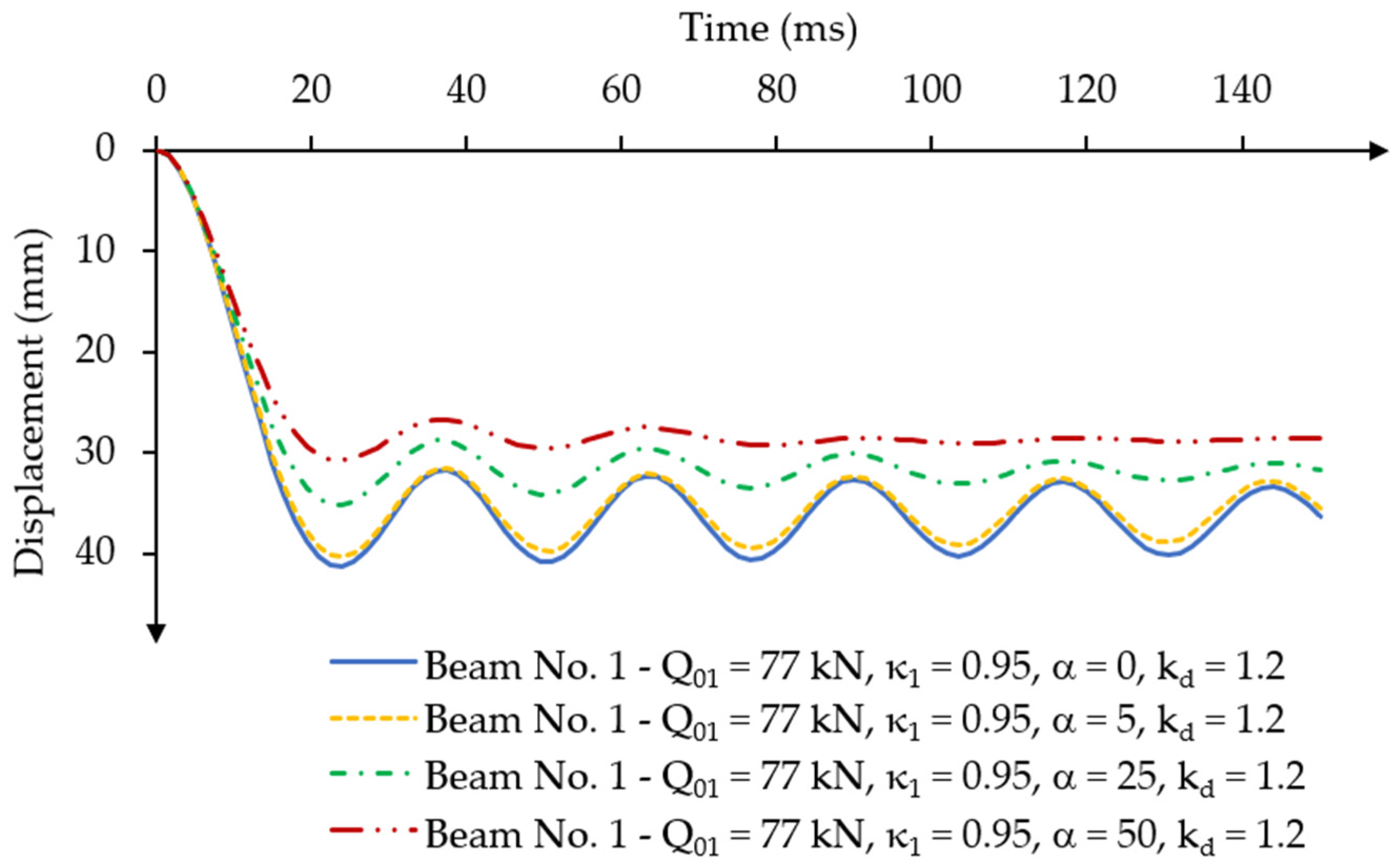

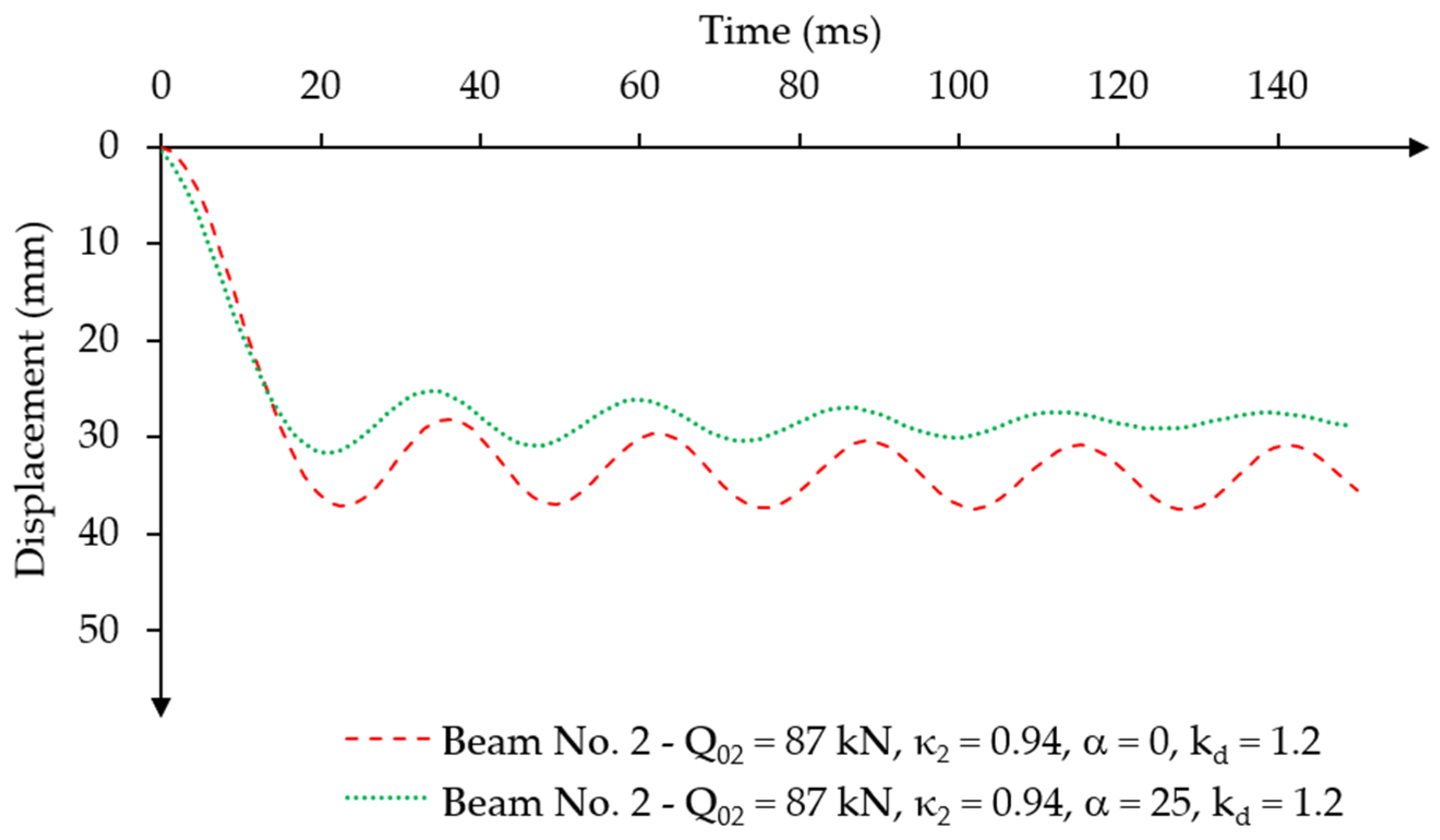

3.1.2. Selection of the Mass Damping Parameter

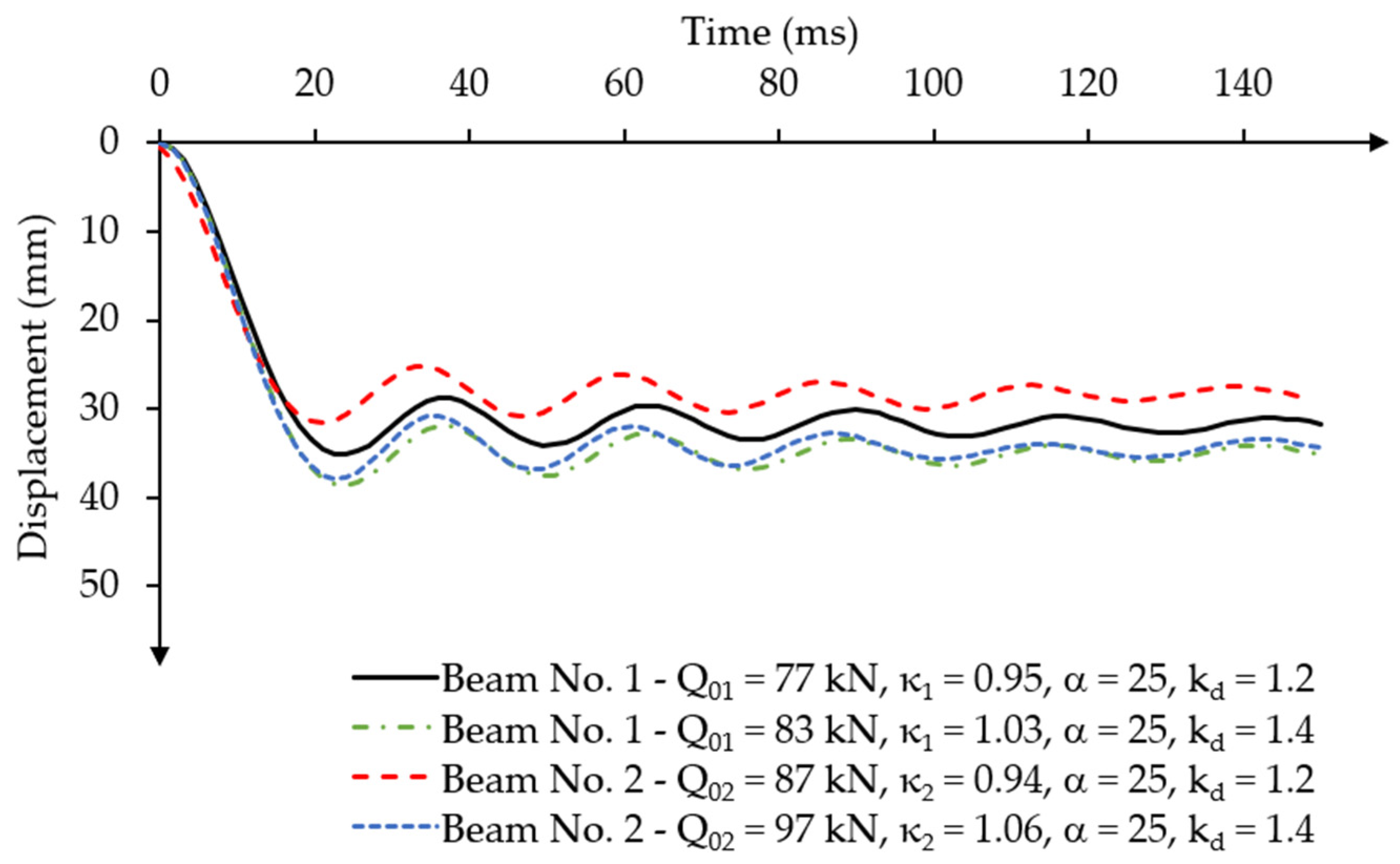

3.1.3. Influence Analysis of the Dynamic Strength Coefficient of Concrete on the Dynamic Response of Post-Tensioned Beams for Constant Force Impulse over Time

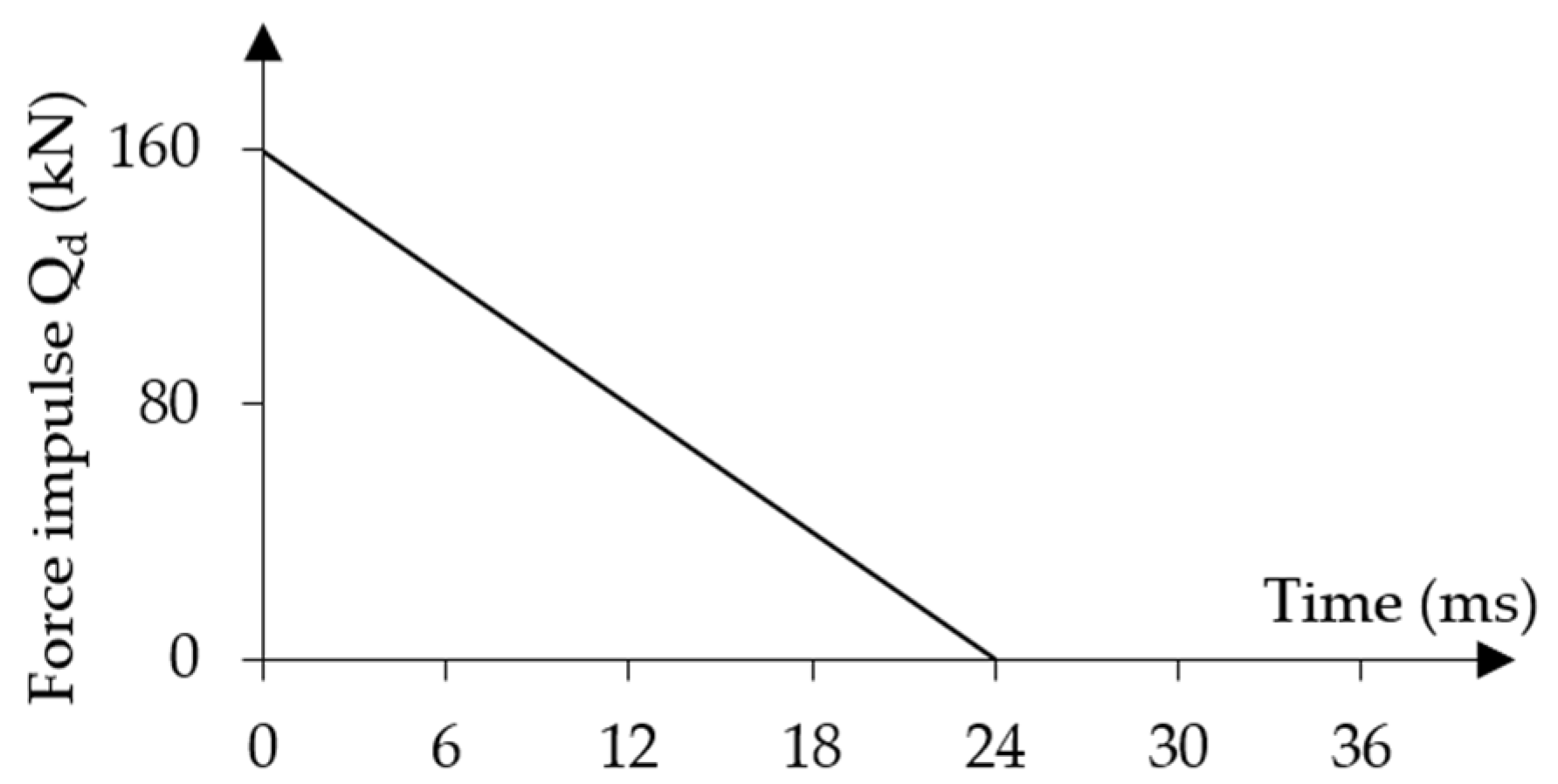

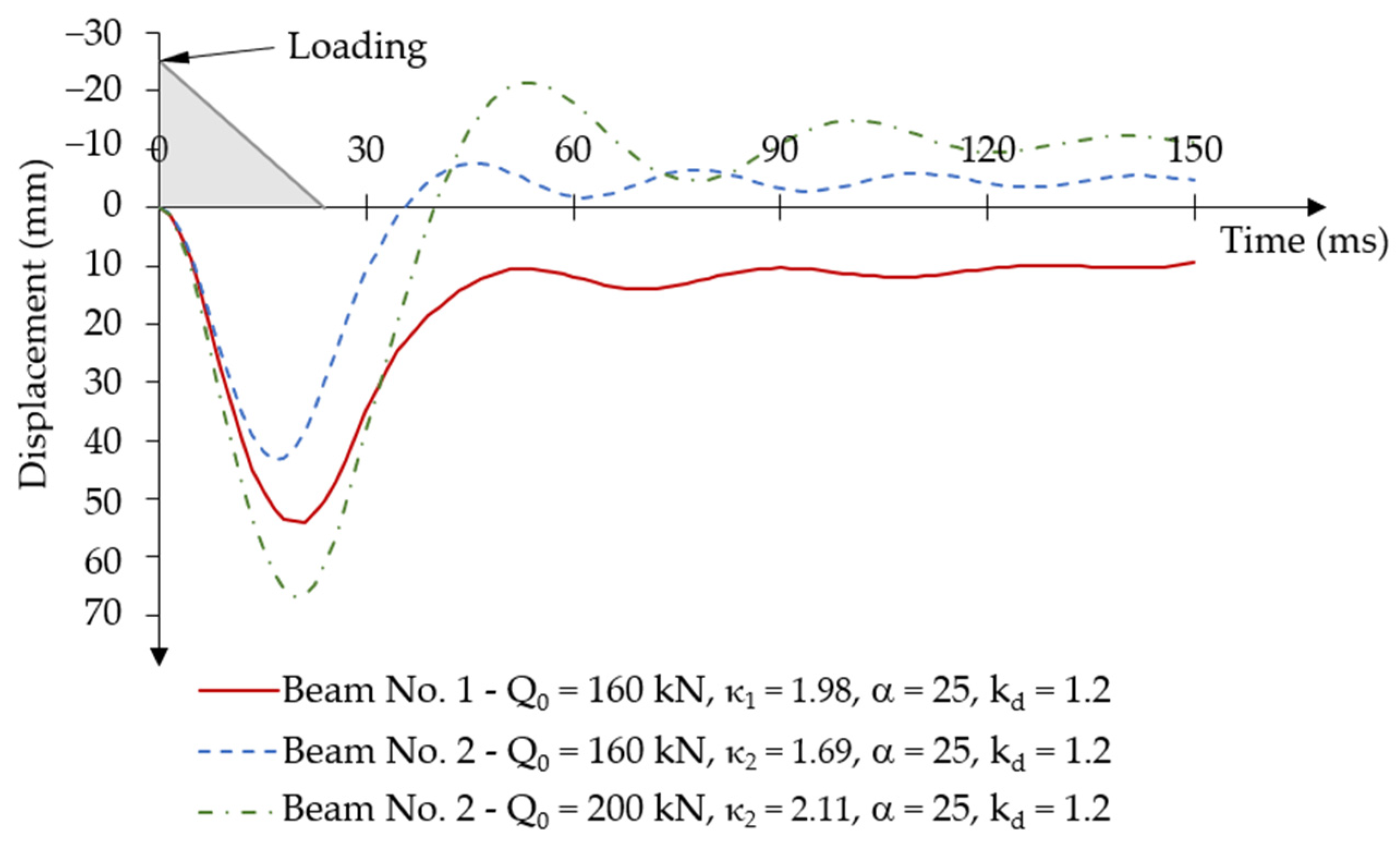

3.2. The Effect of a Short-Term Time-Varying Force Impulse

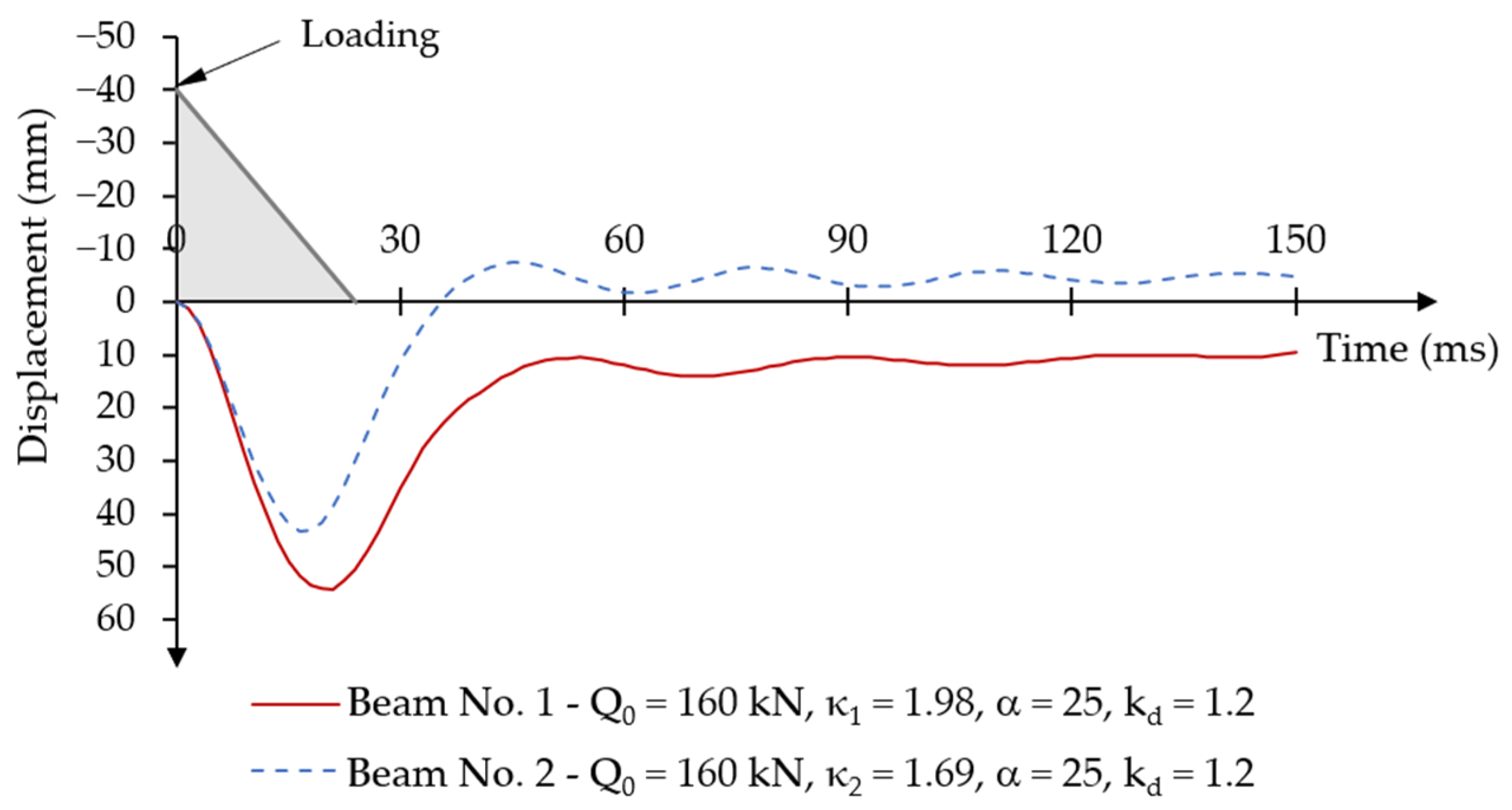

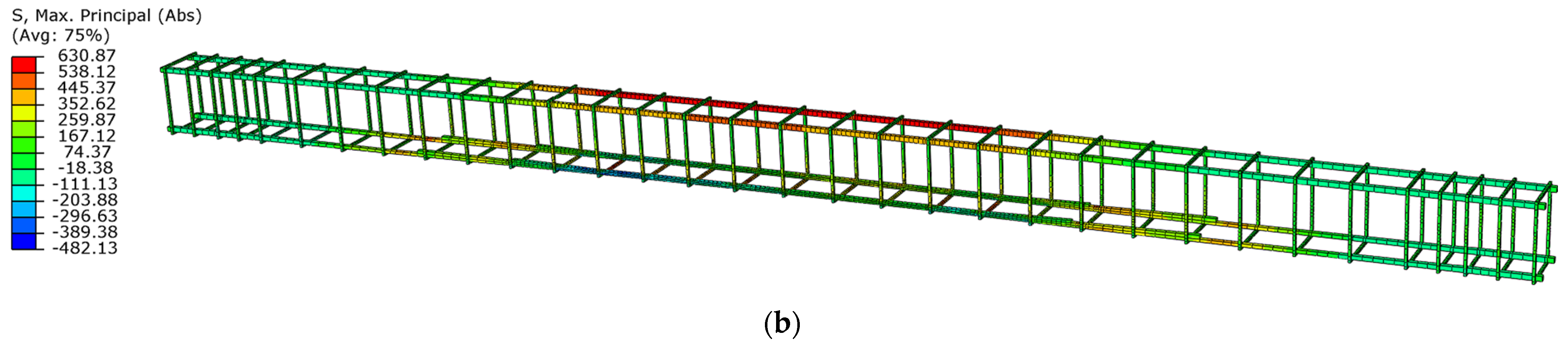

3.2.1. Determination of the Dynamic Load-Capacity of Post-Tensioned Beams

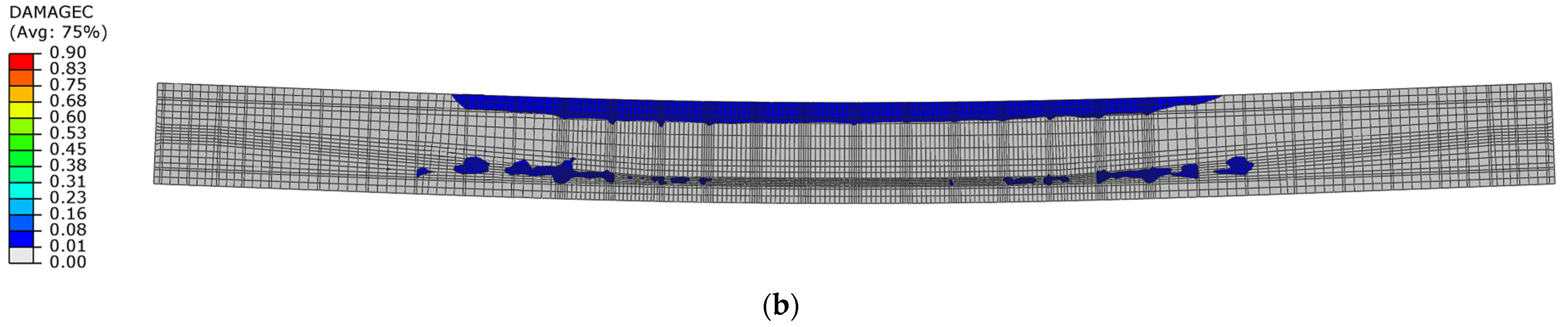

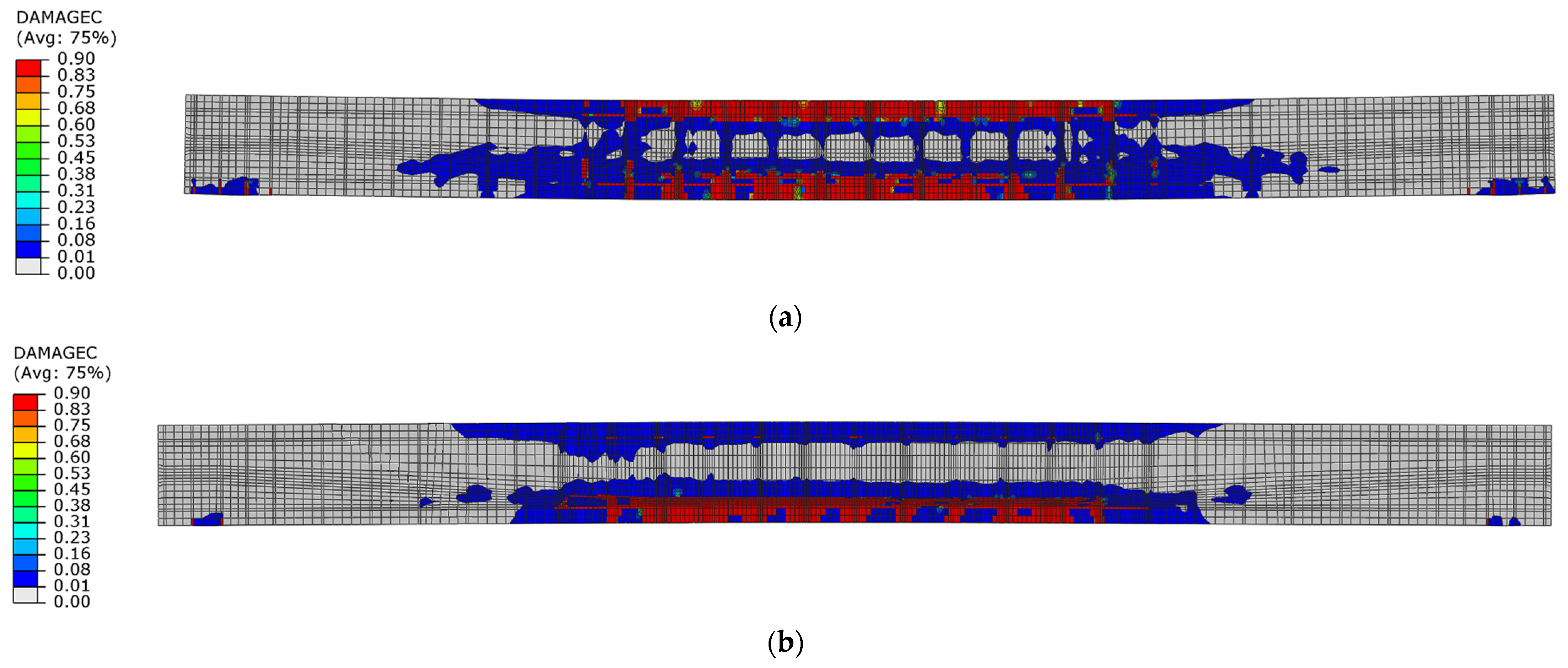

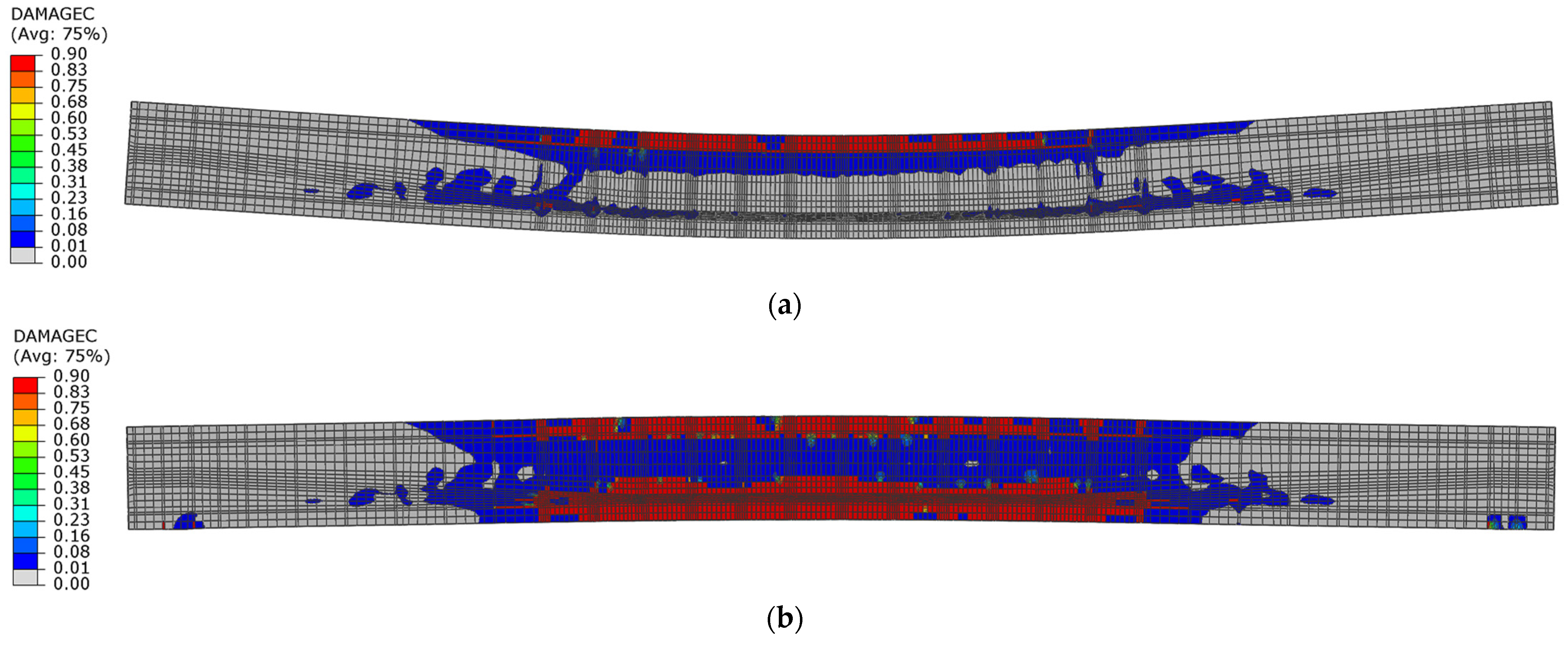

3.2.2. Damage Mechanism Analysis and Load-Capacity Analysis

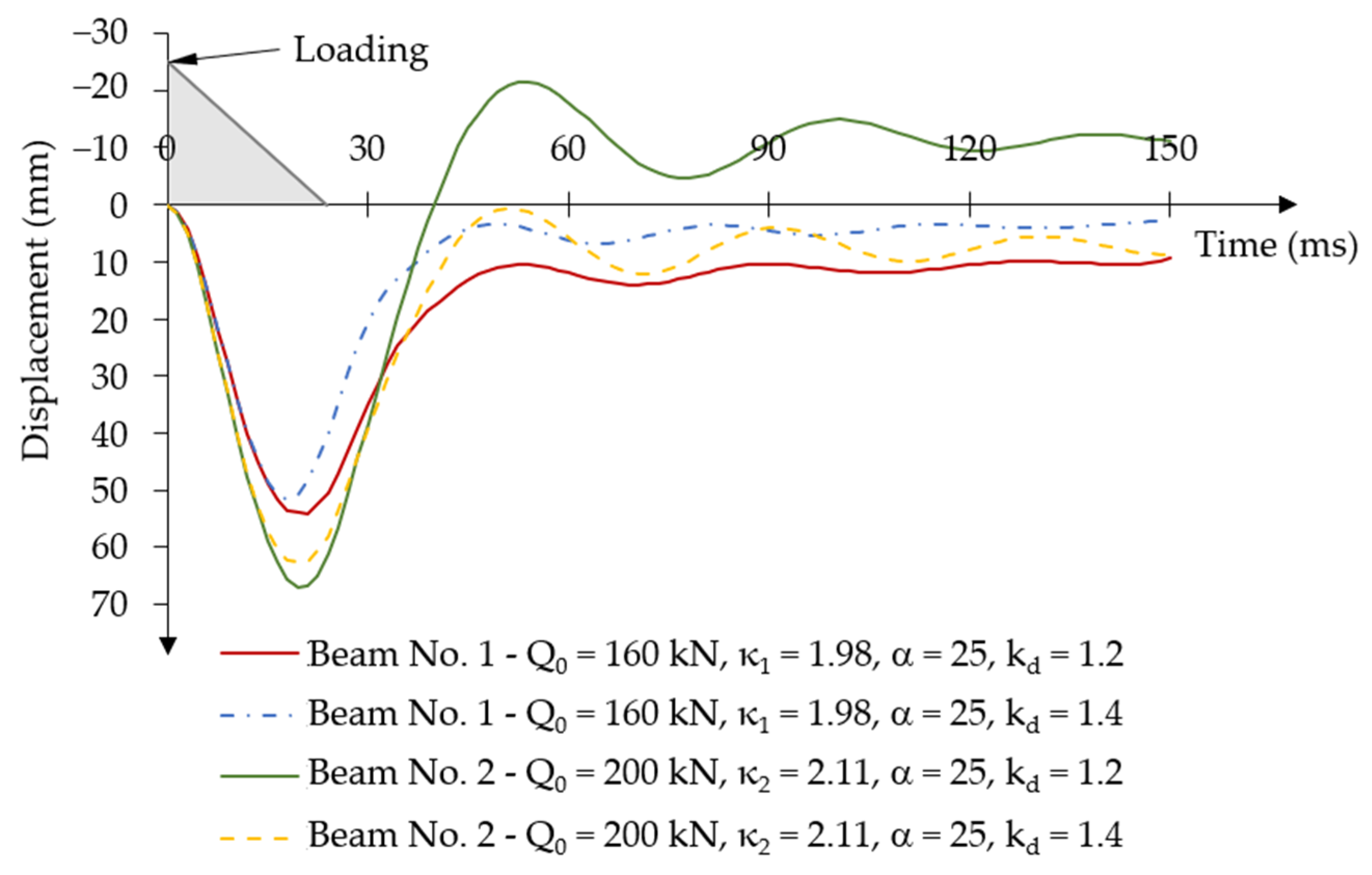

3.2.3. Influence Analysis of the Dynamic Strength Coefficient of Concrete on the Dynamic Response of Post-Tensioned Beams for Variable Force Impulse over Time

4. Conclusions

- The explicit method for solving the dynamic equilibrium equation using Abaqus/Explicit is an efficient numerical method for analysing the dynamic problem for post-tensioned beams with a non-linear prestressing tendon.

- The use of a Rayleigh mass damping parameter of α = 25 for post-tensioned beams with different prestressing eccentricity led to a damped motion that decayed after reaching the maximum displacement amplitude 5–10 times.

- Modelling the dynamic behaviour of concrete based on the assumption of a constant dynamic strength coefficient of concrete in compression.

- Numerical models of dynamically loaded post-tensioned concrete beams showed some specific differences in the influence of the prestressing eccentricity on the value of displacement change over time, the permanent displacement value and the dynamic load capacity. These values depend on the specific type of force impulse action.

- In the numerical simulation of the effects of a constant force impulse over time, the post-tensioned beams obtained a lower load capacity by approximately 5% compared to the load capacity achieved in the experimental static tests [20], regardless of the assumed prestressing eccentricity. A constant amplitude difference was achieved in both beams, which indicates the stability of the method. However, the values of permanent displacements were smaller in the beam with the higher prestressing eccentricity for a load value of 95% of the static load capacity.

- The value of the dynamic strength coefficient of concrete significantly influences the dynamic response characteristics of post-tensioned beams under a constant force impulse over time. The dynamic load capacity increases relative to the static load capacity for higher values of the dynamic strength coefficient of concrete. The beam with a larger eccentricity achieved a 6% increase in dynamic load capacity, while the beam with a smaller eccentricity achieved a 3% increase in dynamic load capacity.

- Numerical models of post-tensioned beams showed a dynamic load capacity significantly exceeding the static load capacity under a short-term time-varying force impulse load. The beam with the larger prestressing eccentricity achieved a dynamic load capacity at an initial impulse load value of 211% of the static load capacity, while the beam with the smaller prestressing eccentricity achieved a dynamic load capacity value of 198% of the static load capacity. During the loading phase, both beams had similar vertical displacement characteristics. However, the beam with the larger prestressing eccentricity reached the first maximum displacement amplitude earlier than the beam with the smaller prestressing eccentricity at the same initial short-term impulse load. In the unloading phase, as the system returned to the equilibrium position and permanent plastic deformations in the concrete were achieved, the beam with the greater prestressing eccentricity reached a negative value of the first minimum displacement amplitude. However, in the beam with the smaller prestressing eccentricity, the values of the first minimum displacement amplitude were positive.

- The value of the dynamic strength coefficient of concrete significantly influences the dynamic response characteristics of prestressed post-tensioned concrete beams under the action of a short-term time-varying force impulse load. When a higher value of the dynamic strength coefficient of concrete was applied to the beam with a larger prestressing eccentricity, no negative oscillations of displacement amplitudes occurred during the unloading phase. However, increasing the value of the dynamic strength coefficient of concrete in the beam with a smaller prestressing eccentricity resulted in only a reduction in permanent displacements by approximately 67%.

- The presented method for determining the dynamic load capacity of post-tensioned beams is applicable to other structural elements. On the basis of static load capacity, the initial dynamic loading conditions can be assumed for numerical simulations.

- A constant amplitude difference achieved under constant load over time and without damping indicates the stability of the analysis method.

- The dynamic load capacity increases relative to the static load capacity for higher values of the dynamic strength coefficient of concrete.

- Depending on the prestressing eccentricity, the post-tensioned beams indicated some specific differences in behaviour under short-term, time-varying impulse force. It was related to the predominant effect of the greater prestressing eccentricity during the unloading phase, in conjunction with changes in the concrete compression damage zones.

- The conducted numerical simulations show that post-tensioned beams with variable prestressing eccentricity effectively contribute to dynamic loading.

- Appropriate parameters of the recording equipment used in experimental tests are essential for accurately capturing very high accelerations and displacements. In the case of short-term, time-varying impulse loading, these phenomena occur within extremely short time intervals.

- Preparation of the experimental stand should enable adjustments for large vertical displacement values, particularly observed in post-tensioned beams with larger prestressing eccentricity.

- The design of the experimental stand should include sufficiently stiff supports to prevent the occurrence of vertical displacements, as these influence the measured accelerations and displacement values.

- The design of the experimental stand must accommodate the vertical upward movement of post-tensioned beams at midspan, caused by inertial effects following load application.

- Accurate recording of the magnitudes of force impulse at all points of application is essential in four-point bending tests.

- Strain rate values affect the strength of the materials used in the test beams, including concrete, reinforcing steel, and prestressing steel. For each material component, these values must be determined through experimental testing.

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Hop, T. The effect of degree of prestressing and age of concrete beams on frequency and damping of their free vibration. Mater. Struct. 1991, 24, 210–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noh, M.-H.; Seong, T.-R.; Lee, J.; Park, K.-S. Experimental investigation of dynamic behavior of prestressed girders with internal tendons. Int. J. Steel Struct. 2015, 15, 401–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, B.H.; Kim, S.J.; Yeo, K.S.; Jang, J.B.; Lee, H.P. Estimating Effective Prestress Force on Grouted Tendon by Impact Responses. In Dynamics of Civil Structures, Volume 4; Proulx, T., Ed.; Conference Proceedings of the Society for Experimental Mechanics Series; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cigada, A.; Caprioli, A.; Vanali, M. Experimental investigation of the pre-tension effects on the modal parameters of a slender pre-tensioned concrete beam. In Dynamics of Civil Structures, Volume 4; Proulx, T., Ed.; Conference Proceedings of the Society for Experimental Mechanics Series; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, T.H.-K.; Nghiem, A.; Demartino, C.; Zhou, S. Structural resilience of post-tensioned members to repeated low-velocity impacts. Eng. Struct. 2025, 330, 119902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sadraie, H.; Soltani, H.; Khaloo, A.; Bakhtiari Doost, R.; Abdoos, H. Experimental and numerical study of bidirectional post-tensioned and reinforced concrete slabs subject to drop-impact load. Structures 2025, 77, 109136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tran, D.T.; Pham, T.M.; Hao, H. Experimental and analytical investigations of prefabricated segmental concrete beams post-tensioned with unbonded steel/FRP tendons subjected to impact loading. Int. J. Impact Eng. 2024, 186, 104868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al Rawi, Y.; Temsah, Y.; Baalbaki, O.; Jahami, A.; Darwiche, M. Experimental investigation on the effect of impact loading on behavior of post-tensioned concrete slabs. J. Build. Eng. 2020, 31, 101207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, H.; Chorzepa, M.G. An effective numerical simulation methodology to predict the impact response of pre-stressed concrete members. Eng. Fail. Anal. 2015, 55, 63–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nghiem, A.; Kang, T.H.-K. Validation of Numerical Modeling Techniques for Unbonded Post-Tensioned Beams under Low Velocity Impact. J. Struct. Eng. 2022, 148, 04022101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mortar, N.A.M.; Al Bakri, A.; Mohd, M.; Hussin, K.; Razak, R.A.; Hamat, S.; Hilmi, A.H.; Shahedan, N.N.; Li, L.Y.; Ikmal, H.A. Finite element analysis on structural behaviour of geopolymer reinforced concrete beam using Johnson-Cook damage in Abaqus. Arch. Metall. Mater. 2022, 67, 1349–1354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erdem, R.T.; Gücüyen, E. Numerical Investigation of Impact Loads on RC Beams. Proc. Bulg. Acad. Sci. 2025, 78, 1039–1050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, J. Impact Performance of RC Beams Reinforced by Engineered Cementitious Composite. Buildings 2023, 13, 1688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayhan, B.; Lale, E. Modeling strain rate effect on tensile strength of concrete using damage plasticity model. Int. J. Impact Eng. 2022, 162, 104132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gebbeken, N.; Greulich, S. A new material model for SFRC under high dynamic loadings. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Interaction of the Effects of Munitions with Structures, Mannheim, Germany, 5–9 May 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Zhu, Z.-M.; Hu, Y.-C.; Tan, Y.-H.; Xi, F. Rate correlation of elastic modulus and damage factor in the concrete damage plasticity model and its implementation. Structures 2025, 78, 109354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.; Li, Z.; Li, H.; He, M.; Gao, W.; Zhou, J.; Xu, Z. Dynamic response of concrete materials at high strain rates: Experimental and numerical studies. Eng. Fract. Mech. 2025, 330, 111606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cadoni, E.; Fontana, M.; Forni, D.; Knobloch, M. High strain rates testing and constitutive modeling of B500B reinforcing steel at elevated temperatures. Eur. Phys. J. Spec. Top. 2018, 227, 179–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Filiatrault, A.; Holleran, M. Stress-strain behavior of reinforcing steel and concrete under seismic strain rates and low temperatures. Mat. Struct. 2001, 34, 235–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jancy, A.; Stolarski, A.; Zychowicz, J. Experimental and Numerical Research of Post-Tensioned Concrete Beams. Materials 2023, 16, 4141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stolarski, A. Dynamic strength criterion for concrete. J. Eng. Mech. 2004, 130, 1428–1435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stolarski, A.; Cichorski, W.; Szcześniak, A. Non-Classical Model of Dynamic Behavior of Concrete. Appl. Sci. 2019, 9, 2590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, G.R.; Cook, W.H. A Constitutive Model and Data for Metals Subjected to Large Strain, High Strain Rates and High Temperature. In Proceedings of the 7th International Symposium on Ballistics, The Hague, The Netherlands, 19–21 April 1983; pp. 541–547. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson, G.R.; Cook, W.H. Fracture Characteristics of Three Metals Subjected to Various Strains, Strain Rates, Temperatures and Pressures. Eng. Fract. Mech. 1985, 21, 31–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perzyna, P. The Constitutive Equations for Rate Sensitive Plastic Materials. Quart. Appl. Math. 1963, 20, 321–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- TTM Tension Technology S.r.l. European Technical Approval ETA-09/0012, TTM Monostrand System Types E and EX; Consiglio Superiore Dei Lavori Pubblici: Ceprano, Italy, 2009.

- ABAQUS. Dassault Systemes User Assistance R2026x GA, Version 2025. Available online: https://www.3ds.com/support/documentation/user-guides (accessed on 30 October 2025).

- Brenkus, N.R.; Tatar, J.; Hamilton, H.R.; Consolazio, G.R. Simplified finite element modelling of post-tensioned concrete members with mixed bonded and unbonded tendons. Eng. Struct. 2019, 179, 387–397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jankowiak, T.; Łodygowski, T. Identification of parameters of concrete damage plasticity constitutive model. Found. Civ. Environ. Eng. 2005, 5, 53–69. [Google Scholar]

- Sümer, Y.; Aktaş, M. Defining parameters for concrete damage plasticity model. Chall. J. Struct. Mech. 2015, 1, 149–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szczecina, M.; Winnicki, A. Calibration of the CDP model parameters in Abaqus. In Proceedings of the The 2015 World Congress on Advances in Structural Engineering and Mechanics (ASEM15), Incheon, Republic of Korea, 25–29 August 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Voyiadjis, G.Z.; Taqieddin, Z.N. Elastic Plastic and Damage Model for Concrete Materials: Part I—Theoretical Formulation. Int. J. Struct. Changes Solids—Mech. Appl. 2009, 1, 31–59. [Google Scholar]

- Yu, T.; Teng, J.G.; Wong, Y.L.; Dong, S.L. Finite element modeling of confined concrete-II: Plastic-damage model. Eng. Struct. 2010, 32, 680–691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- EN 1992-1-1; Design of Concrete Structures: Part 1-1: General Rules and Rules for Buildings. European Committee for Standardization: Brussels, Belgium, 2004.

- Cichorski, W.; Stolarski, A. Prognosis of Dynamic Behaviour of Reinforced Concrete Deep Beams of Very High Strength Materials. Arch. Civ. Eng. 2020, 66, 257–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bąk, G.; Stolarski, A. Delayed Yield Effect in Dynamic Flow of Elastic/Visco-Perfectly Plastic Material. Arch. Mech. 1985, 37, 285–302. [Google Scholar]

- Wriggers, P. Nonlinear Finite Element Methods; Springer: Berlin, Germany, 2008. [Google Scholar]

| Parameter | Value | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| = 1.0 | = 1.2 | = 1.4 | |

| 59.0 MPa | 69.20 MPa | 79.40 MPa | |

| 4.095 MPa | 4.39 MPa | 4.64 MPa | |

| 21.05 GPa | 22.08 GPa | 23.01 GPa | |

| 0.4 | 0.4 | 0.4 | |

| 0.1 | 0.1 | 0.1 | |

| 0.1 | 0.1 | 0.1 | |

| 3.45‰ | 3.75‰ | 4.03‰ | |

| 0.19‰ | 0.20‰ | 0.20‰ | |

| 6.0‰ | 6.60‰ | 7.20‰ | |

| 0.42‰ | 0.42‰ | 0.42‰ | |

| Parameter | (°) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Value | 56.3 | 0.1 | 1.16 | 0.677 | 0 |

| Steel Element | (GPa) | (MPa) | (MPa) | (kg/m3) | ) | (°K) | (°K) | (°K) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Prestressing steel | 181.6 | 1816 | 7112 | 7850 | 0.3 | 0.024 | 0.02 | 0.00001 | 293 | 293 | 1540 | 1.03 |

| Reinforcing bar ϕ6 | 210.0 | 532 | 1136 | 0.05 | ||||||||

| Reinforcing bar ϕ10 | 210.0 | 541 | 943 | |||||||||

| Anchorage | 200.0 | 430 | 1710 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Jancy, A.; Stolarski, A. Numerical Simulation of the Post-Tensioned Beams Behaviour Under Impulse Forces Loading. Materials 2025, 18, 5432. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma18235432

Jancy A, Stolarski A. Numerical Simulation of the Post-Tensioned Beams Behaviour Under Impulse Forces Loading. Materials. 2025; 18(23):5432. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma18235432

Chicago/Turabian StyleJancy, Anna, and Adam Stolarski. 2025. "Numerical Simulation of the Post-Tensioned Beams Behaviour Under Impulse Forces Loading" Materials 18, no. 23: 5432. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma18235432

APA StyleJancy, A., & Stolarski, A. (2025). Numerical Simulation of the Post-Tensioned Beams Behaviour Under Impulse Forces Loading. Materials, 18(23), 5432. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma18235432