Electrical Resistivity and Carburizing Efficiency of Materials Used in the Cast Iron Melting Process

Abstract

1. Introduction

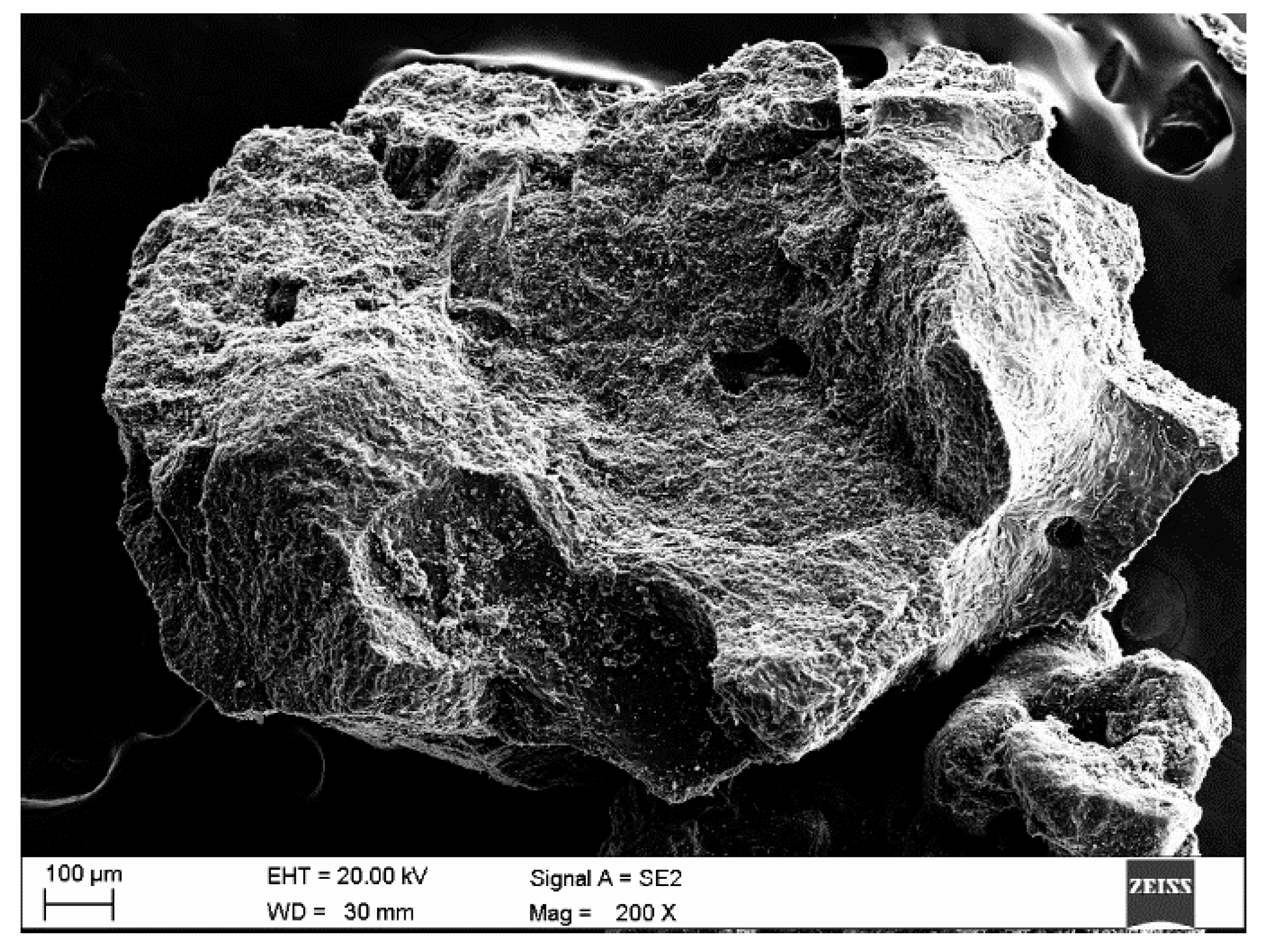

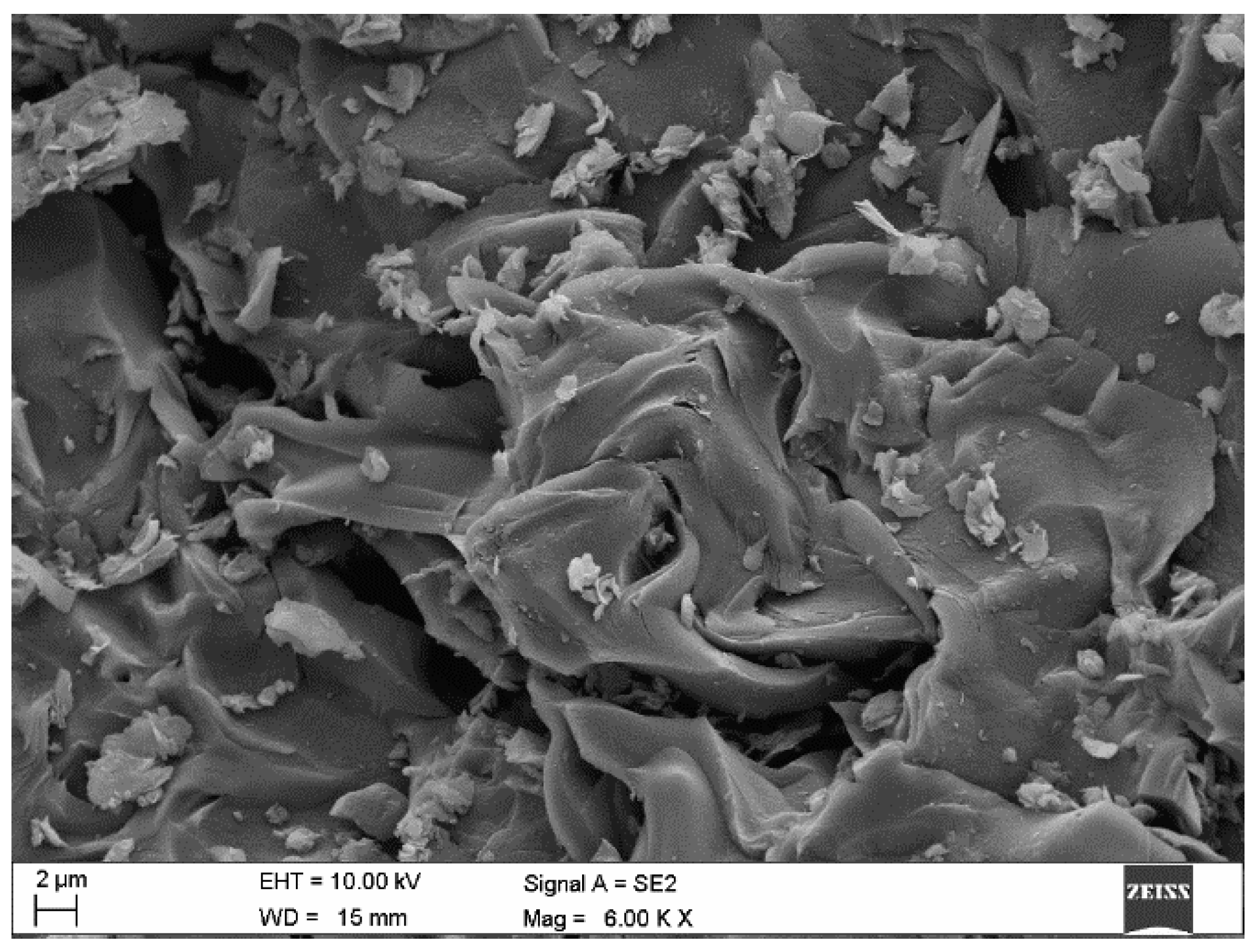

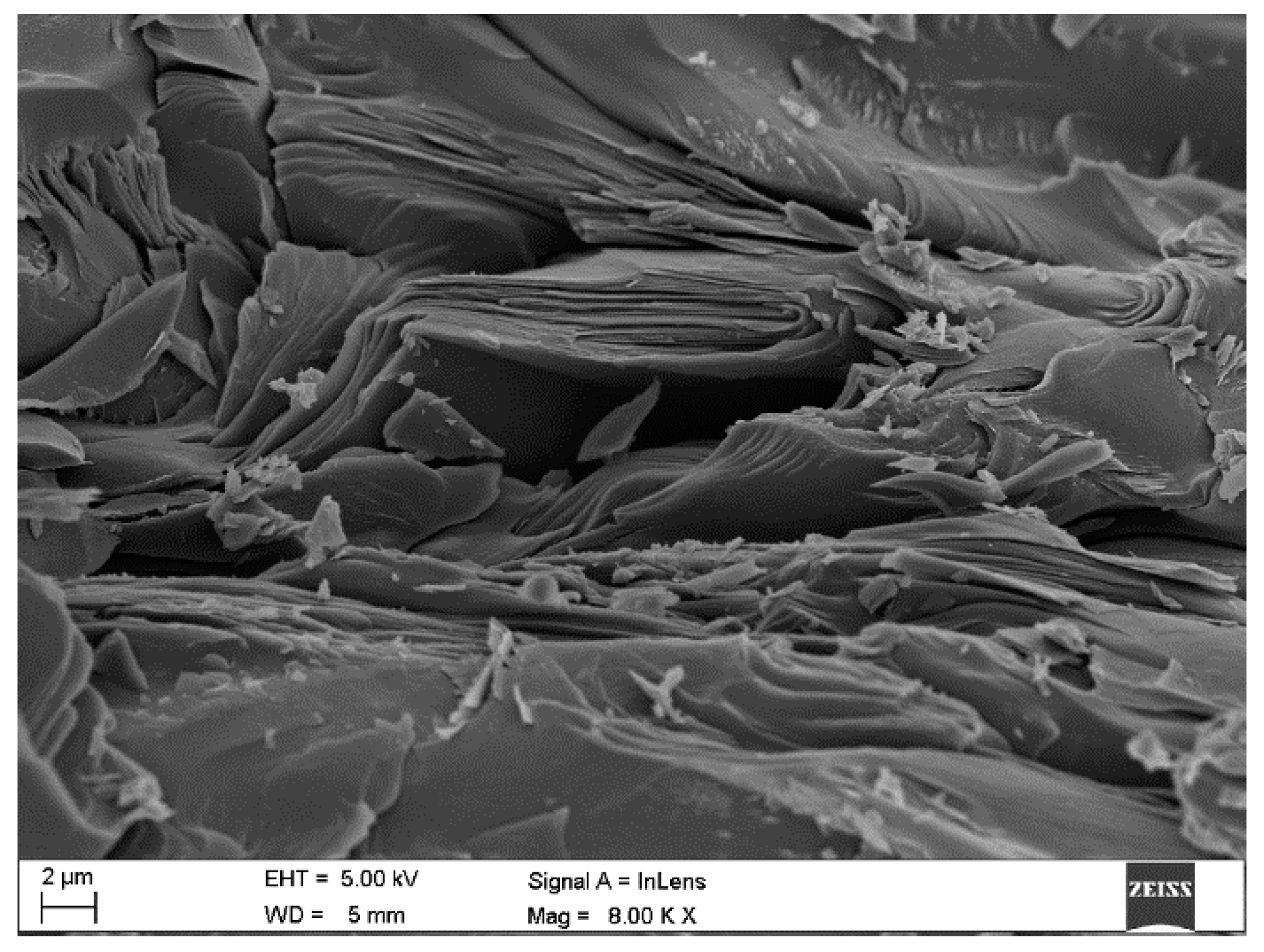

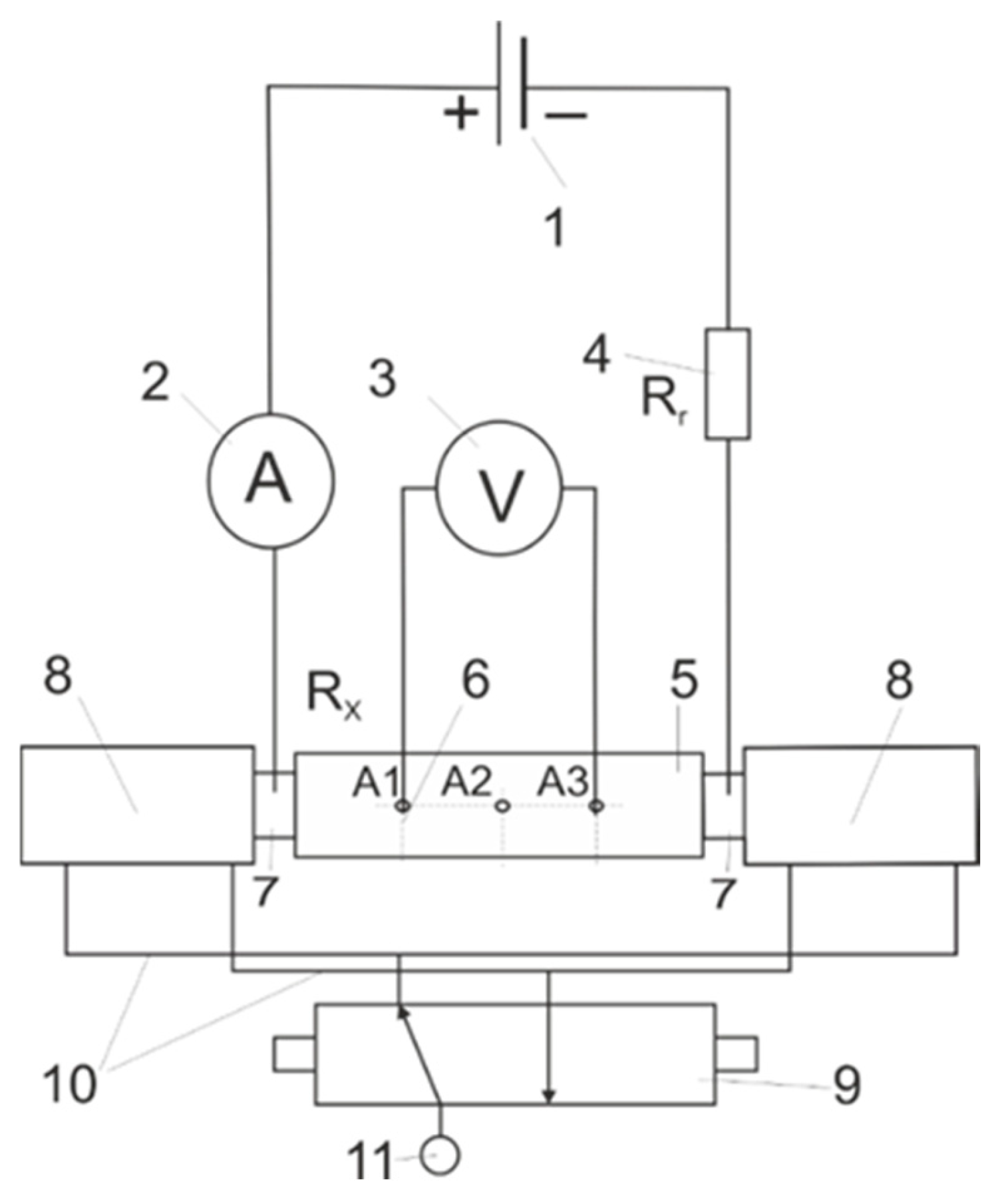

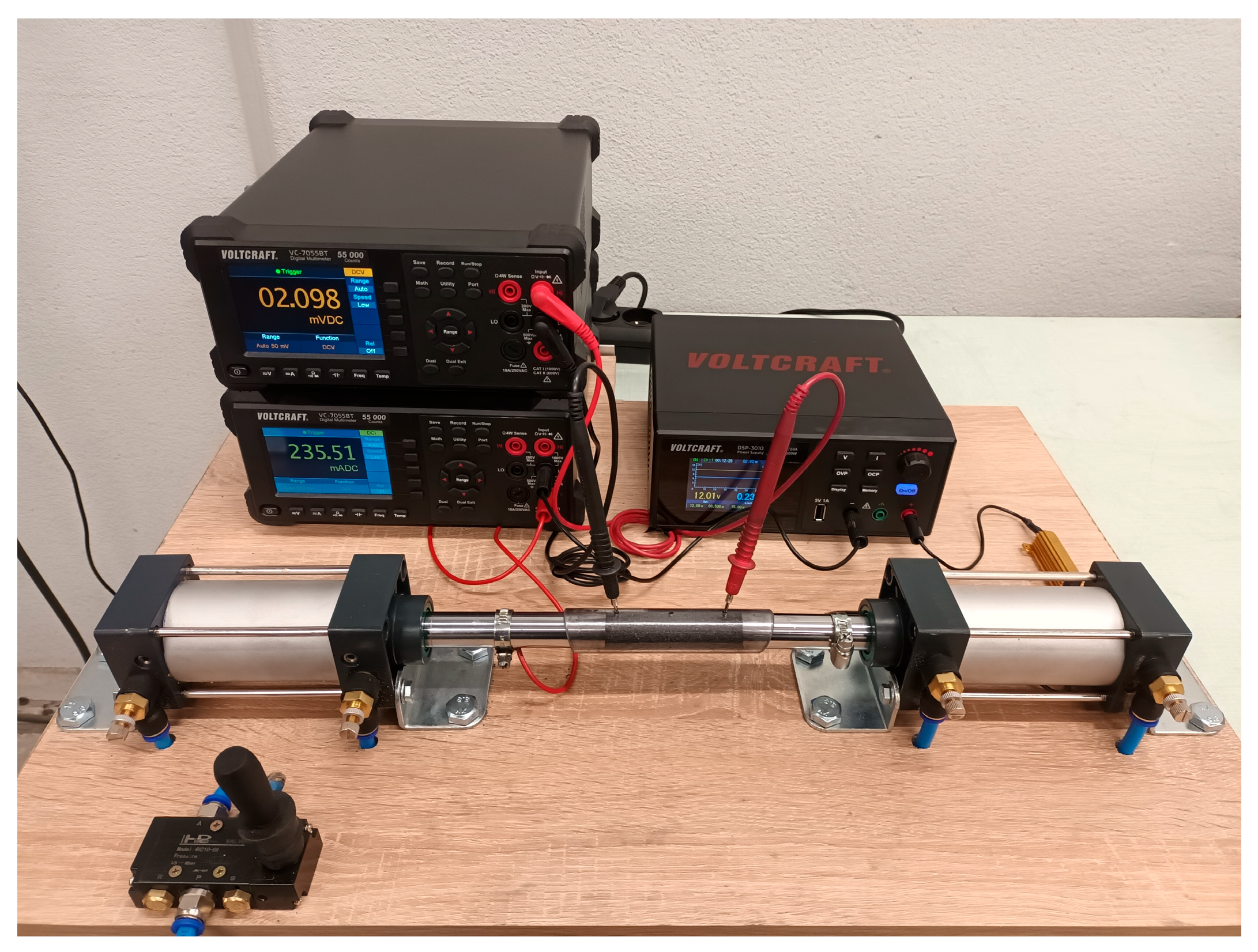

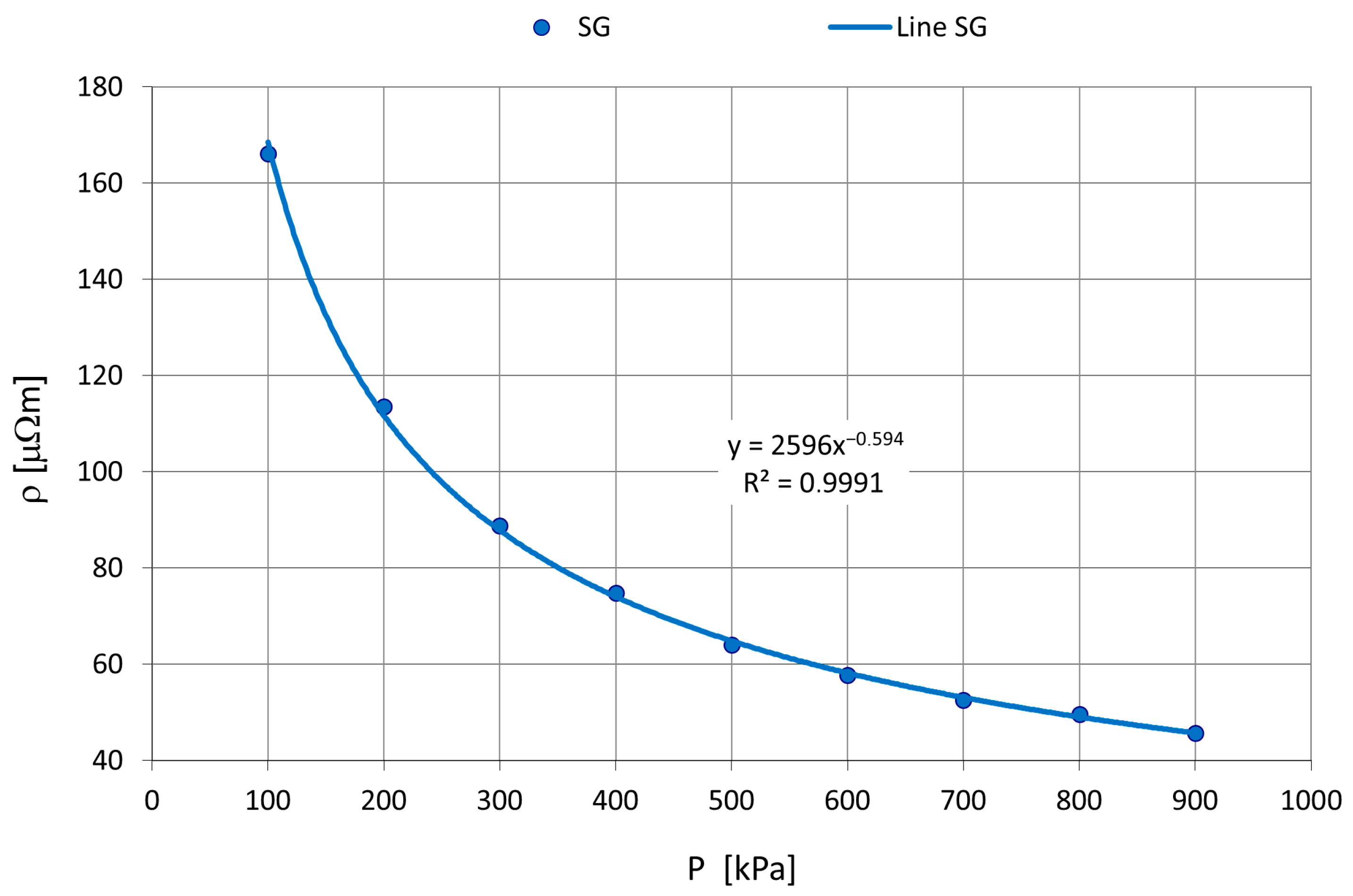

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results

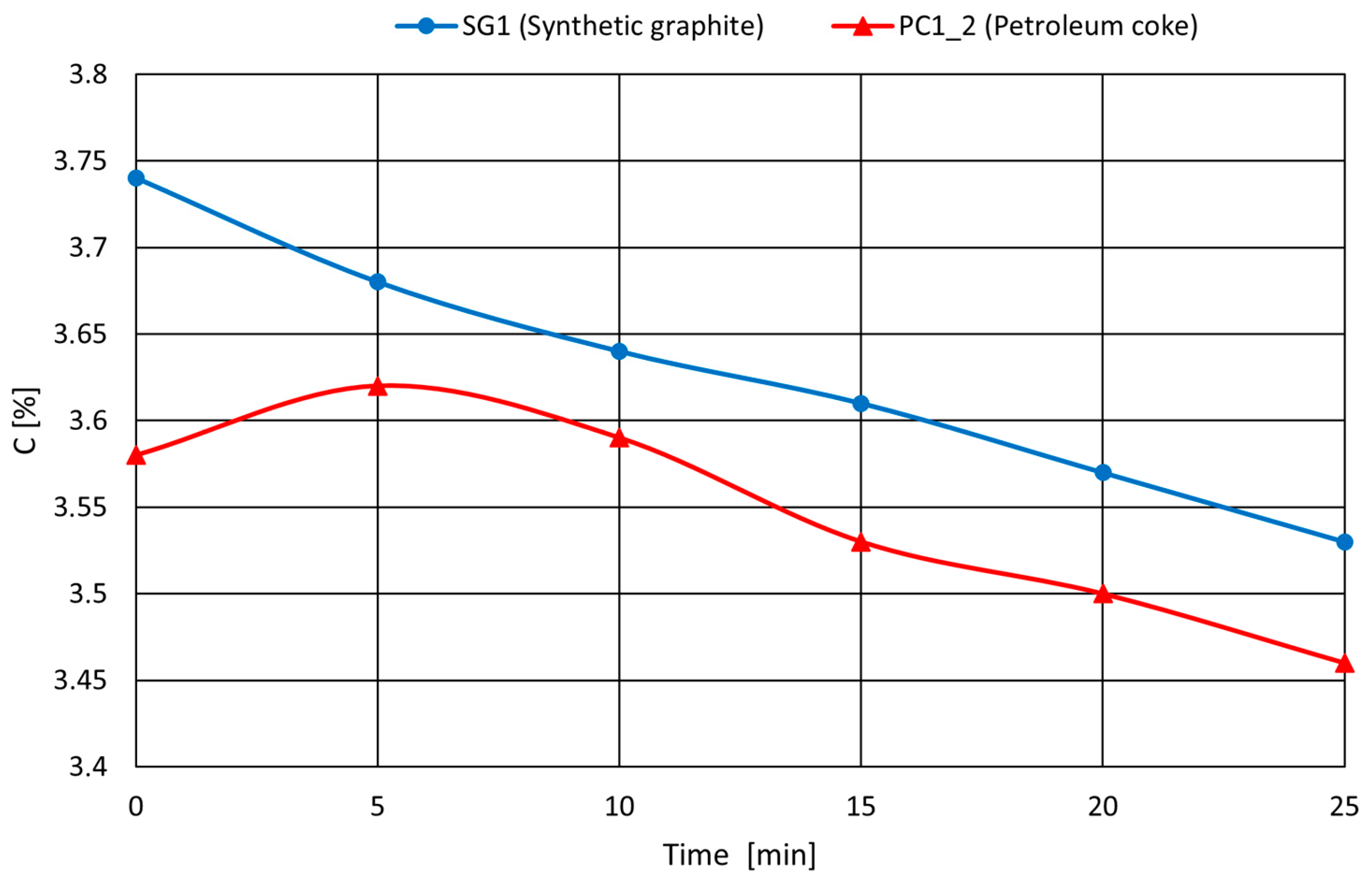

Melting Experiments

- Mm—mass of the metal,

- Mn—mass of the carburizer,

- Cmn—carbon content in the carburizer (assumed to be 98% for all materials),

- DC—increase in carbon content in cast iron, calculated from the initial carbon content Cp and the final content Ck after melting (Delta C = Ck − Cp). The calculated carburization efficiencies are summarized in Table 4.

4. Conclusions

- The investigated carburizing materials (petroleum coke and synthetic graphite) exhibited a wide range of electrical resistivity values, ranging from 36.5 to 1390 mΩ·m.

- A correlation was established that enables the prediction of carburization efficiency from the measured and calculated electrical resistivity, with a very high coefficient of determination (R2).

- A correlation was established enabling the prediction of carburization efficiency from the measured and calculated electrical resistivity, with a very high coefficient of determination (R2).

- Electrical resistivity measurements are significantly more cost-effective and much less time-consuming (requiring only a few minutes) compared to the costs and time associated with melting experiments and chemical analyses needed to determine the carburization efficiency of production-grade carburizers.

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- A/RES/70/1. Transforming Our World: The 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development. Resolution Adopted by the General Assembly on 25 September 2015. Available online: https://commission.europa.eu/ (accessed on 23 April 2025).

- Janerka, K.; Jezierski, J.; Szajnar, J.; Stawarz, M. Sposób i Układ do Pomiaru Oporności Właściwej Materiałów Węglowych. PL Patent 227630, 31 January 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Sanchez-Gonzalez, J.; Macıas-Garcıa, A.; Alexandre-Franco, M.F.; Gomez-Serrano, V. Electrical conductivity of carbon blacks under compression. Carbon 2005, 43, 741–747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Celzard, A.; Mareche, J.F.; Payot, F.; Furdin, G. Electrical conductivity of carbonaceous powders. Carbon 2002, 40, 2801–2815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Probst, N.; Grivei, E. Structure and electrical properties of carbon black. Carbon 2002, 40, 201–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pantea, D.; Darmstadt, H.; Kaliaguine, S.; Summchen, L.; Roy, C. Electrical conductivity of thermal carbon blacks. Influence of surface chemistry. Carbon 2001, 39, 1147–1158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skoczkowski, K. Technologia Produkcji Wyrobów Węglowo-Grafitowych; Śląskie Wydawnictwo Techniczne: Katowice, Poland, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Skoczkowski, K. Wykładziny Węglowo-Grafitowe; Wydawnictwo Fundacji im. Wojciecha Świętosławskiego na Rzecz Wspierania Nauki i Potencjału Naukowego w Polsce; Gliwice: Gliwice, Poland, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Rattanaweeranona, S.; Limsuwana, P.; Thongpoola, V.; Piriyawonga, V.; Asanithia, P. Influence of Bulk Graphite Density on Electrical Conductivity. Procedia Eng. 2012, 32, 1100–1106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Mao, H.-K. Solid Carbon at High Pressure: Electrical Resistivity and Phase Transition. Phys. Chem. Miner. 1994, 21, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janerka, K.; Pawlyta, M.; Jezierski, J.; Szajnar, J.; Bartocha, D. Carburiser properties transfer into the structure of melted cast iron. J. Mater. Process. Technol. 2014, 214, 794–801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janerka, K.; Jezierski, J.; Pawlyta, M. The properties and structure of the carburisers. Arch. Foundry Eng. 2010, 10, 67–74. [Google Scholar]

- Janerka, K.; Jezierski, J.; Stawarz, M.; Szajnar, J. Method for Resistivity Measurement of Grainy Carbon and Graphite Materials. Materials 2019, 12, 648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- ASTM C611-98; Standard Test Method for Electrical Resistivity of Manufactured Carbon and Graphite Articles at Room Temperature. ASTM International: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2017.

- Grafitowe Elektrody do Pieców Łukowych. Available online: https://www.carbograf.pl/graf-elektrody-do-piecow-lukowych (accessed on 20 April 2025).

- Szadkowski, B. Laboratorium Metrologii Elektrycznej i Elektronicznej: Praca Zbiorowa. Cz.1, Pomiary Wybranych Wielkości Fizycznych, 9th ed.; Wyd. Pol. Śląskiej: Gliwice, Poland, 2004. [Google Scholar]

| Source of Variance Comp. | Variance Component | (% of Total Variance) |

|---|---|---|

| Total Gage R&R | 0.0011996 | 4.92 |

| Repeatability | 0.0006915 | 2.83 |

| Reproducibility | 0.0005081 | 2.08 |

| Operator | 0.0001020 | 0.42 |

| Operator × sample no. | 0.0004062 | 1.66 |

| Part-To-Part | 0.0232028 | 95.08 |

| Total Variation | 0.0244024 | 100.00 |

| No. | Carburizer | C; % | S; % | Ashes; % | VOC; % | Humidity; % |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | SG1 | 98.5 | 0.20 | 0.30 | 0.60 | 0.20 |

| 2 | SG2 | 99.20 | 0.05 | 0.64 | 0.24 | 0.30 |

| 3 | SG3 | 99.97 | 0.01 | 0.03 | 0.20 | 0.03 |

| 4 | SG4_1 | 99.35 | 0.04 | 0.20 | 0.25 | 0.10 |

| 5 | SG4_2 | 99.35 | 0.04 | 0.20 | 0.25 | 0.10 |

| 6 | SG4_3 | 99.35 | 0.04 | 0.20 | 0.25 | 0.10 |

| 7 | SG1_2 | 98.50 | 0.28 | 0.24 | 0.47 | 0.01 |

| 8 | PC1 | 98.4 | 1.27 | 0.2 | 0.5 | 0.2 |

| 9 | PC2 | 99.25 | 0.82 | 0.48 | 0.27 | 0.10 |

| 10 | PC3 | 98.00 | 0.6 | 0.6 | 1.00 | 0.50 |

| 11 | PC4 | 98.40 | 1.27 | 0.22 | 0.34 | 0.26 |

| 12 | PC5 | 98.20 | 1.26 | 1.26 | 0.25 | 0.53 |

| 13 | PC6 | 98.30 | 0.86 | 0.28 | 0.24 | 0.47 |

| 14 | PC7 | 99.6 | 0.03 | 0.3 | 0.7 | 0.3 |

| 15 | PC4_2 | 98.3 | 1.26 | 0.1 | 0.4 | 0.3 |

| 16 | PC1_2 | 98.3 | 1.05 | 0.39 | 0.35 | 0.25 |

| No. | Carburizers | Specific Resistivity [μΩ m] |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | SG1 | 35.92 |

| 2 | SG2 | 36.1 |

| 3 | SG3 | 76.95 |

| 4 | SG4_1 | 95.6 |

| 5 | SG4_2 | 95.6 |

| 6 | SG4_3 | 95.6 |

| 7 | SG1_2 | 144.5 |

| 8 | PC1 | 172.1 |

| 9 | PC2 | 282.6 |

| 10 | PC3 | 550 |

| 11 | PC4 | 672.2 |

| 12 | PC5 | 704.6 |

| 13 | PC6 | 740.6 |

| 14 | PC7 | 792.00 |

| 15 | PC4_2 | 819.00 |

| 16 | PC1_2 | 1390.00 |

| No. | Carburizer | Mm [kg] | Mn [kg] | Cp % | Ck % | E % |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | SG1 | 29.5 | 0.165 | 3.22 | 3.74 | 94.39 |

| 2 | SG2 | 11.73 | 0.210 | 2.20 | 3.81 | 90.66 |

| 3 | SG3 | 11.46 | 0.440 | 0.21 | 3.69 | 90.67 |

| 4 | SG4_1 | 9.82 | 0.400 | 0.21 | 3.68 | 85.75 |

| 5 | SG4_2 | 10.00 | 0.400 | 0.21 | 3.65 | 86.56 |

| 6 | SG4_3 | 9.60 | 0.400 | 0.20 | 3.79 | 86.72 |

| 7 | SG1_2 | 11.74 | 0.216 | 2.20 | 3.77 | 86.63 |

| 8 | PC1 | 14.12 | 0.522 | 0.21 | 3.34 | 85.31 |

| 9 | PC2 | 9.76 | 0.400 | 0.21 | 3.49 | 81.67 |

| 10 | PC3 | 11.76 | 0.235 | 2.20 | 3.68 | 75.27 |

| 11 | PC4 | 29.5 | 0.165 | 3.22 | 3.62 | 72.68 |

| 12 | PC5 | 11.76 | 0.241 | 2.20 | 3.71 | 75.03 |

| 13 | PC6 | 11.76 | 0.241 | 2.20 | 3.75 | 76.94 |

| 14 | PC7 | 29.5 | 0.165 | 3.22 | 3.62 | 71.80 |

| 15 | PC4_2 | 29.5 | 0.165 | 3.22 | 3.61 | 70.43 |

| 16 | PC1_2 | 29.5 | 0.165 | 3.22 | 3.58 | 65.48 |

| No. | Carburizer | E % | Specific Resist. [μΩ m] |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | SG1 | 94.39 | 35.92 |

| 2 | SG2 | 90.66 | 36.10 |

| 3 | SG3 | 90.67 | 76.95 |

| 4 | SG4_1 | 85.75 | 95.60 |

| 5 | SG4_2 | 86.56 | 95.60 |

| 6 | SG4_3 | 86.72 | 95.60 |

| 7 | SG1_2 | 86.63 | 144.50 |

| 8 | PC1 | 85.31 | 172.10 |

| 9 | PC2 | 81.67 | 282.60 |

| 10 | PC3 | 72.68 | 550.00 |

| 11 | PC4 | 75.27 | 672.20 |

| 12 | PC5 | 75.03 | 704.60 |

| 13 | PC6 | 76.94 | 740.60 |

| 14 | PC7 | 71.80 | 792.00 |

| 15 | PC4_2 | 70.43 | 819.00 |

| 16 | PC1_2 | 65.48 | 1390.00 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Janerka, K.; Jezierski, J.; Wojciechowski, M.; Rosanowski, K. Electrical Resistivity and Carburizing Efficiency of Materials Used in the Cast Iron Melting Process. Materials 2025, 18, 5413. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma18235413

Janerka K, Jezierski J, Wojciechowski M, Rosanowski K. Electrical Resistivity and Carburizing Efficiency of Materials Used in the Cast Iron Melting Process. Materials. 2025; 18(23):5413. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma18235413

Chicago/Turabian StyleJanerka, Krzysztof, Jan Jezierski, Mateusz Wojciechowski, and Kacper Rosanowski. 2025. "Electrical Resistivity and Carburizing Efficiency of Materials Used in the Cast Iron Melting Process" Materials 18, no. 23: 5413. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma18235413

APA StyleJanerka, K., Jezierski, J., Wojciechowski, M., & Rosanowski, K. (2025). Electrical Resistivity and Carburizing Efficiency of Materials Used in the Cast Iron Melting Process. Materials, 18(23), 5413. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma18235413