Effects of Rolling Parameters on Stress–Strain Fields and Texture Evolution in Al–Cu–Sc Alloy Sheets

Abstract

1. Introduction

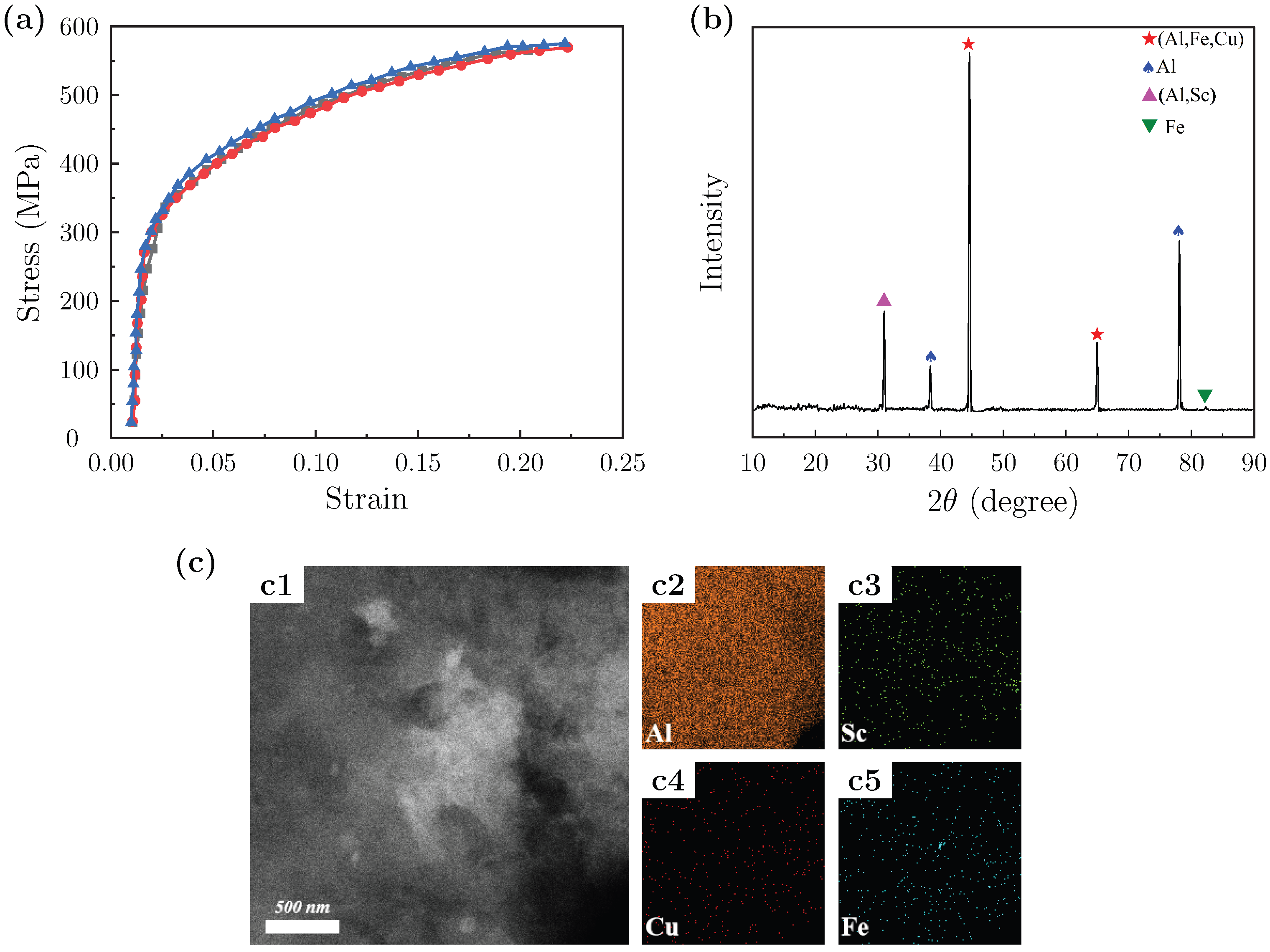

2. Simulation and Experimental Methods

2.1. Simulation Model Development

2.2. Experimental Procedure

3. Results and Discussion

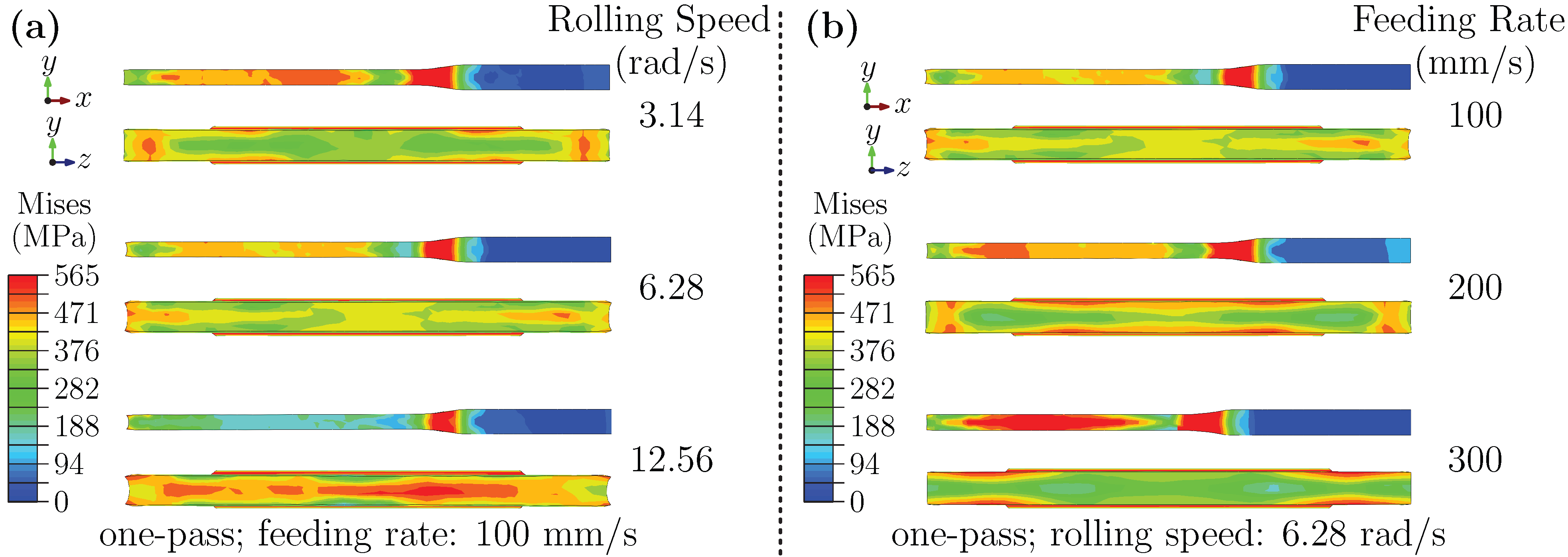

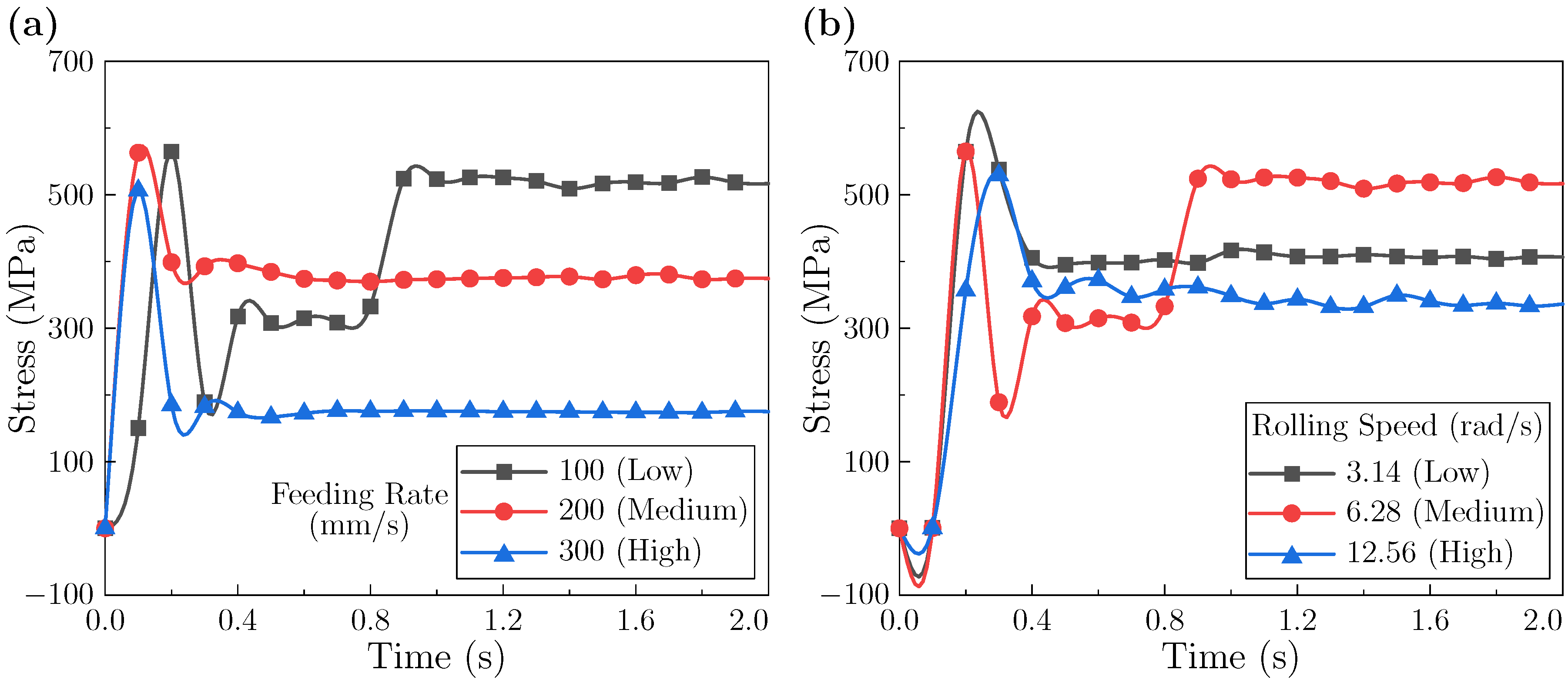

3.1. Stress Analysis

3.1.1. Stress Analysis at Entry Stage: Effects of Rolling Speed and Feeding Rate

3.1.2. Stress Analysis at Deformation Stage: Effects of Rolling Speed and Feeding Rate

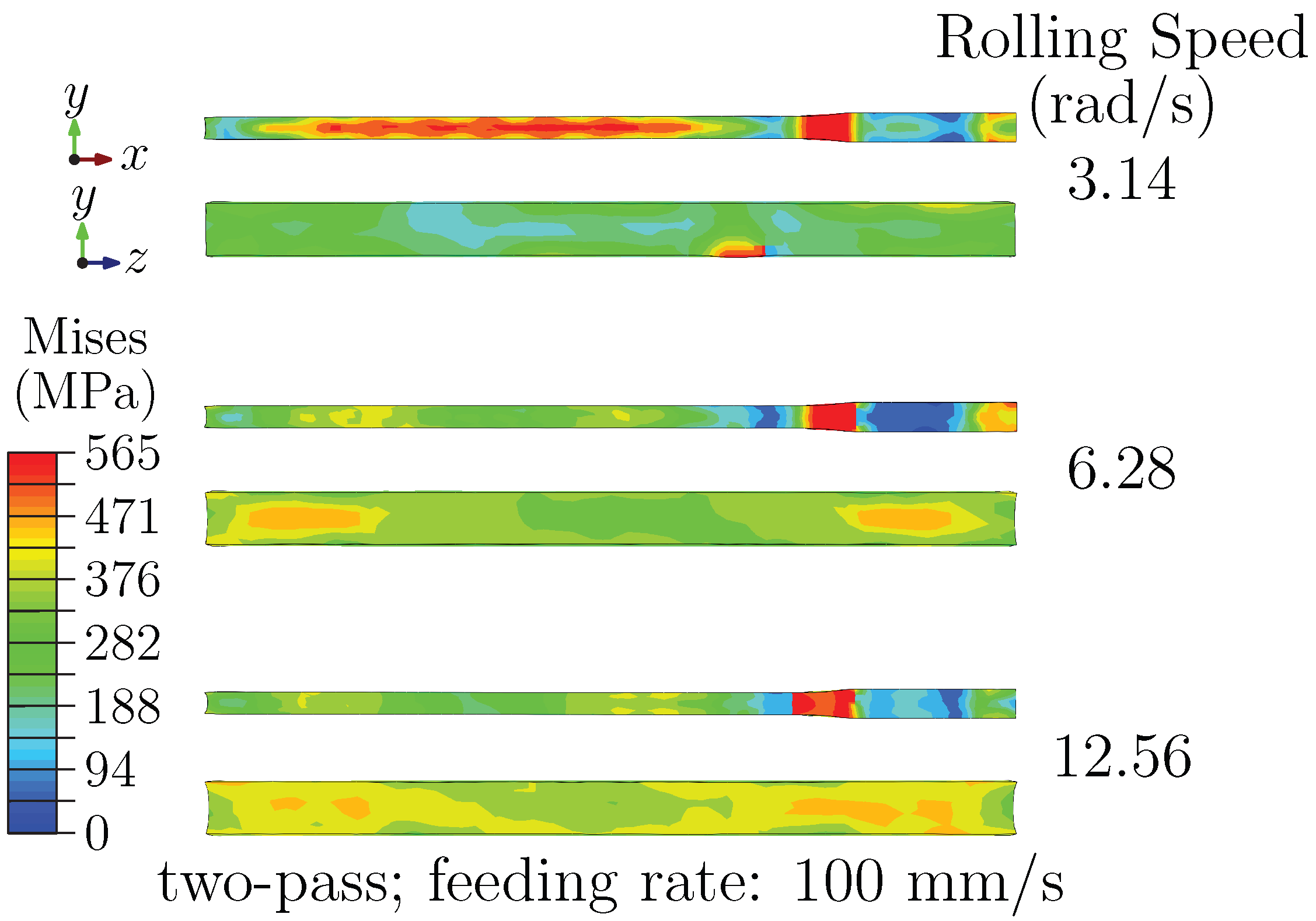

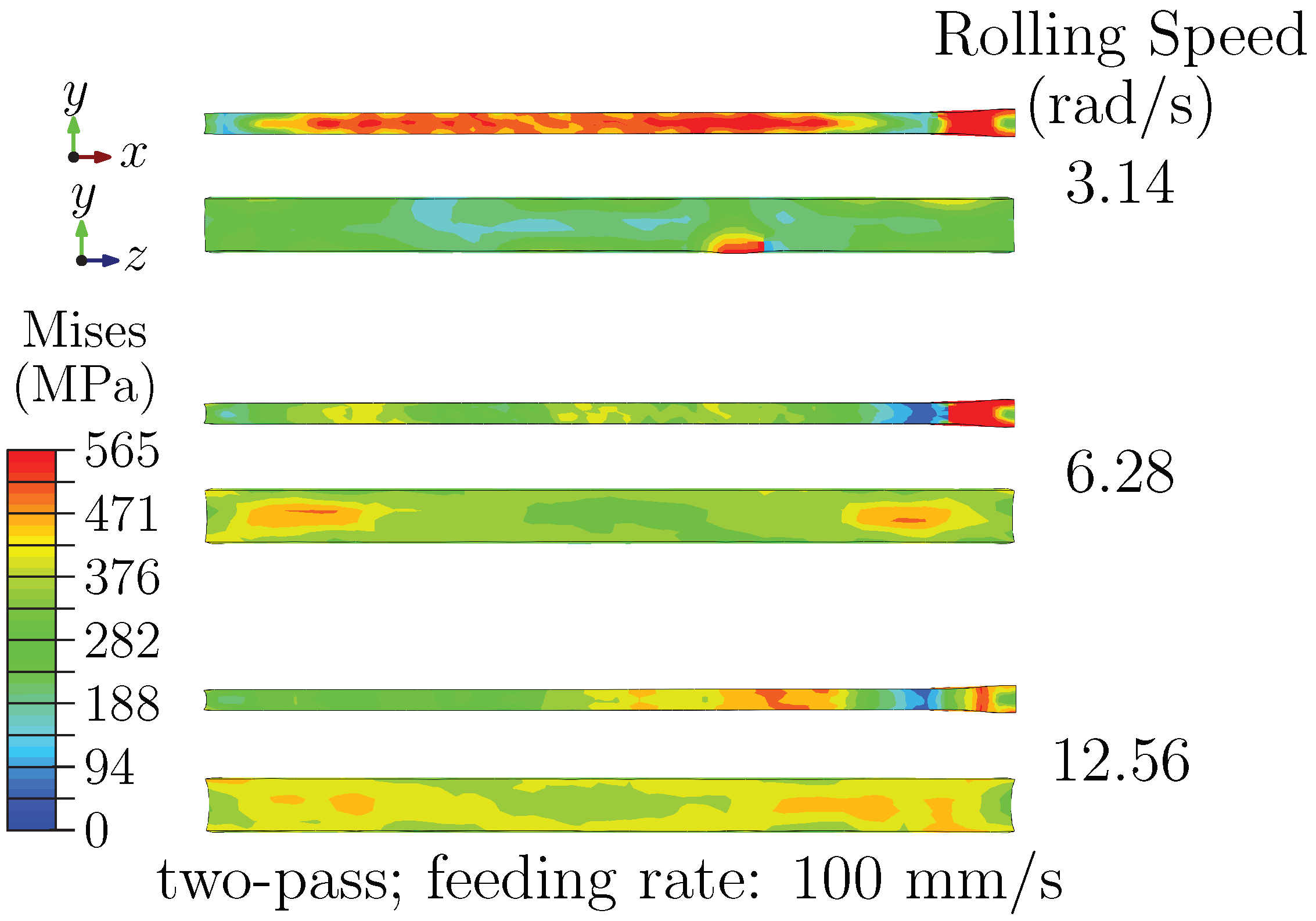

3.1.3. Effect of Pass Number: Inter-Pass Relaxation and Stress Redistribution

3.1.4. Stress Analysis at Exit Stage: Coupled Effects of Rolling Speed, Feeding Rate, and Pass Number

3.1.5. Equivalent Stress Evolution During Rolling

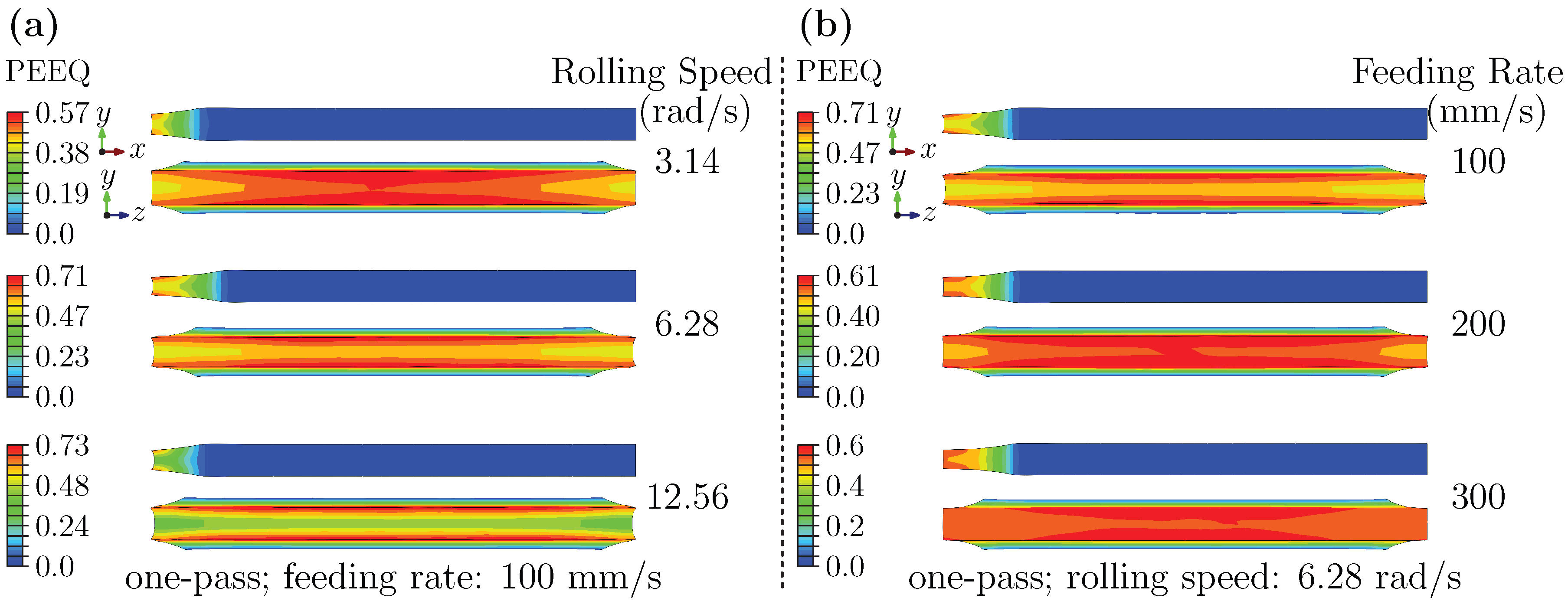

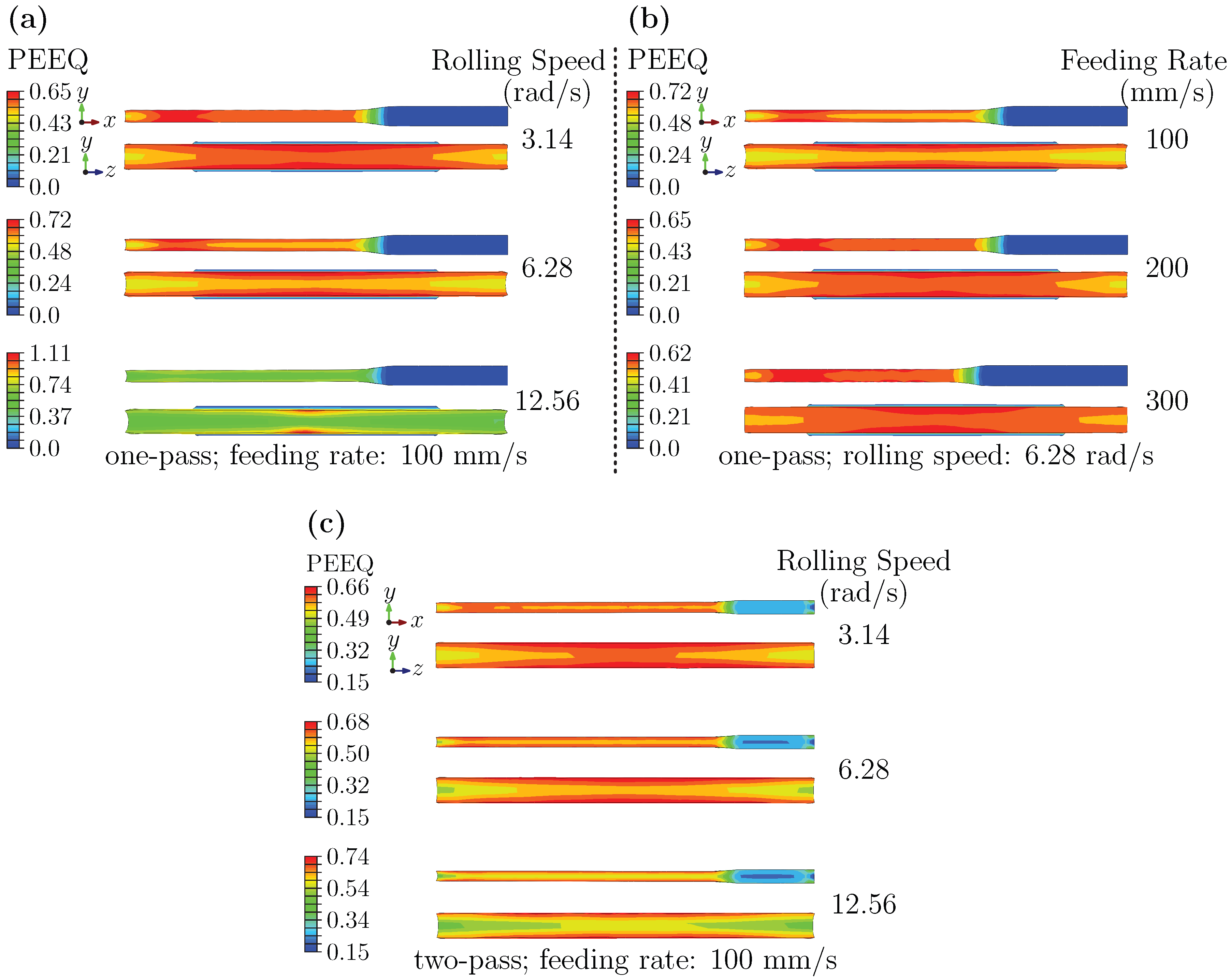

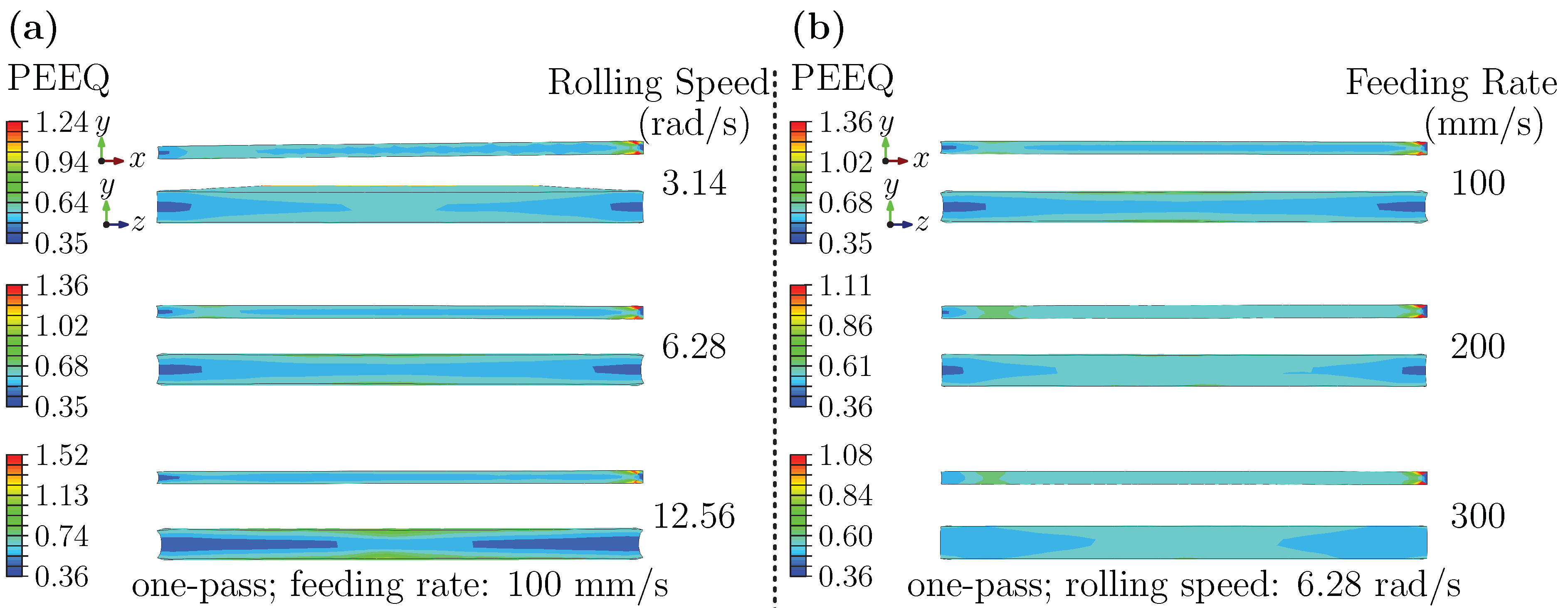

3.2. Strain Analysis

3.2.1. Strain Analysis at Entry Stage: Effects of Rolling Speed and Feeding Rate

3.2.2. Strain Analysis at Deformation Stage: Effects of Rolling Speed, Feeding Rate, and Pass Schedule

3.2.3. Strain Analysis at Final Product Stage: Dependence on Rolling Speed and Feeding Rate

3.3. Rolling Force Analysis

3.3.1. Effect of Rolling Speed

3.3.2. Effect of Feeding Rate

3.3.3. Effect of Differential Speed Ratio

4. Experiment and Texture Analysis

4.1. EBSD Measurement Setup and Results of IPF and KAM Analysis

4.2. Comparison Between VPSC Predictions and Experimental Results

5. Conclusions

- Macroscopic field evolution is dominated by strain-rate effects. Rolling speed plays the most critical role in shaping stress and strain distributions. Higher speeds elevate strain rates, leading to a reduction in peak rolling force and improved stress uniformity on the RD–ND plane. At the same time, they amplify surface–core deformation incompatibility, resulting in residual stress gradients along the ND–TD direction. Feeding rate primarily influences dislocation multiplication and work hardening, thereby raising stress levels and shifting concentration toward the surface. Multi-pass rolling redistributes deformation across passes and facilitates partial recovery, promoting stress homogenization.

- Process parameter interactions govern rolling force behavior and energy demand. Increased rolling speed enhances rolling force fluctuations, while higher feeding rate slightly raise the peak load but stabilize the process by improving flow continuity. The solution for force reduction is demonstrated through asynchronous rolling, which reduces deformation resistance by up to 30% at a differential speed ratio of 2.0. However, the accompanying asymmetric shear can cause sheet warping, underscoring the importance of balancing force reduction with dimensional accuracy and forming quality.

- Microstructural evolution is highly sensitive to deformation kinetics. EBSD and VPSC analyses reveal that higher rolling speed strengthen shear deformation contributions, promoting grain rotation toward orientations and shifting texture toward shear-dominated components. Elevated strain rates also increase dislocation density, manifested as enhanced local orientation gradients. These observations demonstrate that process parameters—especially rolling speed—can be used as effective levers for tuning texture, anisotropy, and recrystallization behavior.

- Integrated simulation–experiment approaches enable predictive process design. The combined FEM–VPSC framework reproduces key macroscopic and microscopic trends across parameter conditions, with close agreement to EBSD measurements. This capability enables the isolation and quantification of parameter effects, providing a foundation for virtual process design, rapid parameter screening, and reduced reliance on extensive experimental iterations.

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| C3D8R | 8-node linear brick element with reduced integration |

| EBSD | Electron Backscatter Diffraction |

| EDM | Electrical Discharge Machining |

| FEM | Finite Element Method |

| IPF | Inverse Pole Figure |

| KAM | Kernel Average Misorientation |

| PEEQ | Equivalent Plastic Strain |

| RD | Rolling Direction |

| ND | Normal Direction |

| TD | Transverse Direction |

| VPSC | Viscoplastic Self-Consistent (model) |

References

- Xue, H.; Yang, C.; Kuang, J.; Zhang, P.; Zhang, J.; Liu, G.; Sun, J. Highly interdependent dual precipitation and its effect on mechanical properties of Al–Cu-Sc alloys. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 2021, 820, 141526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, L.; Li, J.; Cheng, P.; Liu, G.; Wang, R.; Chen, B.; Zhang, J.Y.; Sun, J.; Yang, M.X.; Yang, G. Experiment and modeling of ultrafast precipitation in an ultrafine-grained Al–Cu–Sc alloy. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 2014, 607, 596–604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, B.; Liu, G.; Wang, R.; Zhang, J.; Jiang, L.; Song, J.; Sun, J. Effect of interfacial solute segregation on ductile fracture of Al–Cu–Sc alloys. Acta Mater. 2013, 61, 1676–1690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Dong, S.; Wang, F.; Qian, C.; Deng, Z.; Wang, F.; Zeng, J.; Jin, L.; Dong, J. The combined strengthening of multiple intragranular precipitates and intergranular eutectic structure in a cast heat-resistant Al-Cu-Ce-Mn-Sc-Zr alloy. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 2025, 945, 148979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.; Li, X.; Zhang, Y.; Wen, K.; Yan, L.; Li, Y.; Li, Y.; Yu, M.; Gao, G.; Yan, H.; et al. Achieving high strength and good laser welding performance by adding Sc to T8-aged Al-Cu-Li alloys with different Cu/Li ratios. Mater. Des. 2025, 256, 114285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drits, M.E.; Toropova, L.S.; Dutkiewicz, J.; Salawa, J. Effect of solution treatment on the aging processes of Al-Sc alloys. Cryst. Res. Technol. 1984, 19, 1341–1345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seidman, D.N.; Marquis, E.A.; Dunand, D.C. Precipitation strengthening at ambient and elevated temperatures of heat-treatable Al(Sc) alloys. Acta Mater. 2002, 50, 4021–4035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robson, J.D.; Jones, M.J.; Prangnell, P.B. Extension of the N-model to predict competing homogeneous and heterogeneous precipitation in Al-Sc alloys. Acta Mater. 2003, 51, 1453–1468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blake, N.; Hopkins, M.A. Constitution and age hardening of Al-Sc alloys. J. Mater. Sci. 1985, 20, 2861–2867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iwamura, S.; Miura, Y. Loss in coherency and coarsening behavior of Al3Sc precipitates. Acta Mater. 2004, 52, 591–600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zakharov, V.V. Kinetics of decomposition of the solid solution of scandium in aluminum in binary Al–Sc alloys. Met. Sci. Heat Treat. 2015, 57, 410–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, L.; Li, J.; Liu, G.; Wang, R.; Chen, B.; Zhang, J.; Sun, J.; Yang, M.X.; Yang, G.; Yang, J.; et al. Length-scale dependent microalloying effects on precipitation behaviors and mechanical properties of Al–Cu alloys with minor Sc addition. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 2015, 637, 139–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, Y.; Kuang, J.; Liu, G.; Sun, J. Effect of minor Sc and Fe co-addition on the microstructure and mechanical properties of Al-Cu alloys during homogenization treatment. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 2019, 746, 11–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kairy, S.K.; Rouxel, B.; Dumbre, J.; Lamb, J.; Langan, T.; Dorin, T.; Birbilis, N. Simultaneous improvement in corrosion resistance and hardness of a model 2xxx series Al-Cu alloy with the microstructural variation caused by Sc and Zr additions. Corros. Sci. 2019, 158, 108095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, J.; Ma, S.; Zhu, Y.; Zhao, J.; Wang, B.; Zhang, D.; Fu, Y.; Liao, G.; Wang, S. Sc microalloying improved heat and corrosion resistance of an Al-Cu-Mg alloy under varied heat treatment processes. Mater. Charact. 2025, 228, 115392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, B.; Yin, N.; Miao, J.; Wu, Z.; Zhang, Z.; Luo, A.; Pan, S. Local Al-Cu-Sc ternary phase transformation degrades corrosion performance of Sc-microalloyed Al-Cu alloy. Corros. Sci. 2025, 255, 113152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panda, S.; Vignesh, R.V.; Govindaraju, M. Investigations on the microstructural evolution and mechanical properties of Al-Cu-Al tri-metal strips fabricated through roll bonding and heat-treatment processes. Can. Metall. Quart. 2024, 63, 1012–1029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, H.; Hu, X.; Wang, J.; Zhou, X.; Zhang, Q.; Zhang, B. Evolution and formation mechanism of residual stress in Al-Cu alloy rings during ring rolling and quenching. Eng. Fail. Anal. 2024, 163, 108578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yousefi Mehr, V.; Rezaeian, A.; Toroghinejad, M.R. Effects of processing parameters on the fracture behaviour of cold roll bonded and accumulative roll bonded Al–Cu lamellar composites. Mater. Sci. Technol. 2021, 37, 1096–1106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siahaan, E. The Reduction Effect of Al-Cu Series 2024 on the Processing Rolled In Mechanical Properties. Mater. Sci. Eng. 2020, 1007, 012012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Selvan, C.C.; Narayanan, C.S.; Ravisankar, B.; Narayanasamy, R.; Valliammai, C.T. The dependence of the strain path on the microstructure, texture and mechanical properties of cryogenic rolled Al-Cu alloy. Mater. Res. Express. 2020, 7, 036525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Q.; Li, H.; Zhao, M.; Li, Y.; Ma, Y.; Song, Y. Effect of cold rolling and annealing processes on the microstructure and mechanical properties of S32101 lean duplex stainless steel. J. Mater. Sci. 2025, 60, 17989–18006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, W.; Pang, H.; Wang, Y.; Zheng, W.; Xu, G.; Tian, J. Study on the Deformation Resistance and Microstructure of Interstitial Free Steel under Different Rolling Processes. J. Mater. Eng. Perform. 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, Y.; Cao, J.; Liu, S.; Wang, B.; Zhang, P. Numerical Calculation and Analysis of Temperature Field for Zirconium Alloy Strip in Multi Rolling Processes and Multi-Pass Hot Rolling. J. Phys. Conf. Ser. 2025, 2539, 012040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, F.; Mao, L.; Rong, J.; Zhang, B.; Wei, L.; Wen, S.; Jiao, H.; Wu, S. Influence of different rolling processes on microstructure and strength of the Al–Cu–Li alloy AA2195. Prog. Nat. Sci. Mater. Int. 2022, 32, 87–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, X.; Deng, Y.; Guo, X.; Pan, Q. Influence of asymmetric rolling process and thickness reduction on the microstructure and mechanical properties of the Al–Mg-Si alloy. Met. Mater. Int. 2022, 28, 1620–1629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, W.; Yi, Y.; Huang, S.; Mao, X.; Fang, J.; Tong, D.; Luan, Y. Manufacturing large 2219 Al–Cu alloy rings by a cold rolling process. Mater. Manuf. Process. 2020, 35, 291–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, H. Grain refinement of Mg–Al alloys by optimization of process parameters based on three-dimensional finite element modeling of roll casting. Trans. Nonferrous Met. Soc. China 2013, 23, 773–780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vlach, M.; Stulikova, I.; Smola, B.; Piesova, J.; Cisarova, H.; Danis, S.; Plasek, J.; Gemma, R.; Tanprayoon, D.; Neubert, V. Effect of cold rolling on precipitation processes in Al–Mn–Sc–Zr alloy. Mater. Sci. Eng. A. 2012, 548, 27–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, Q.; Li, W.; Ren, J.; Guo, X.; Li, Q.; Lu, X.; Qiao, J. Dislocation-based mechanical responses and deformation mechanisms of Al/Cu heterointerfaces: A computational study via molecular dynamics simulations. Mod. Phys. Lett. B. 2024, 38, 2450152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, D.; Wang, P.; Zhao, Y. Interfacial reaction and strengthening mechanism of Cu/Al composite strip produced by asymmetrical rolling. J. Northeast. Univ. Nat. Sci. 2019, 40, 1574–1578, 1583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, T.; Song, W.; Shan, F.; Song, K.; Zhang, K.; Peng, C.; Sun, H.; Hu, L. Phase formation, texture evolutions, and mechanical behaviors of Al0.5CoCr0.8FeNi2.5V0.2 high-entropy alloys upon cold rolling. Prog. Nat. Sci. Mater. Int. 2022, 32, 196–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Wang, A.; Liang, T.; Zhang, J.; Mao, Z.; Ji, J.; Xie, J.; Chang, Q.; Su, B.; Liu, S. Texture characteristics and tensile deformation behavior of Cu/Al layered composites prepared by cast-rolling method. J. Mater. Res. Technol. 2024, 29, 461–470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qi, J.; Gong, Z.; Kang, K.; Jin, I. The influence of rolling process on the texture evolution of 7150 high-strength aluminum alloy sheet. Shanghai Met. 2019, 41, 59–65. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, Y.; Liu, X.; Liu, Y.; Yang, C.; Qiu, T. Effect of rolling process on mechanical properties of 2219 aluminum alloy plate. Hot Work. Technol. 2016, 45, 1–4. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, L.; Chapuis, A.; Xin, Y.; Liu, Q. VPSC-TDT modeling and texture characterization of the deformation of a Mg-3Al-1Zn plate. J. Alloy. Compd. 2017, 710, 159–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.; Song, H.; Zhang, S.; Cheng, M.; Lee, M. Effect of shear deformation on plasticity, recrystallization mechanism and texture evolution of Mg–3Al–1Zn alloy sheet: Experiment and coupled finite element-VPSC simulation. J. Alloy. Compd. 2019, 805, 138–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graça, A.; Vincze, G.; Wen, W.; Butuc, M.C.; Lopes, A.B. Numerical Study on Asymmetrical Rolled Aluminum Alloy Sheets Using the Visco-Plastic Self-Consistent (VPSC) Method. Metals 2022, 12, 979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Luan, S.; Yuan, S.; Wang, J.; Chen, L.; Jin, P. Microstructure Evolution and Deformation Behavior of Extruded Mg-5Al-0.6 Sc Alloy during Room and Elevated Temperature Tension Revealed by Ex-Situ EBSD and VPSC. Materials 2023, 16, 4534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Cai, Q.; Xie, B.; Yun, Y.; Zhou, Z. Simulation of microstructure evolution in ultra-heavy plates rolling process based on Abaqus secondary development. Steel Res. Int. 2018, 89, 1800409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bagheripoor, M.; Bisadi, H. Effects of rolling parameters on temperature distribution in the hot rolling of aluminum strips. Appl. Therm. Eng. 2011, 31, 1556–1565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kendig, K.L.; Miracle, D.B. Strengthening mechanisms of an Al-Mg-Sc-Zr alloy. Acta Mater. 2002, 50, 4165–4175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jablonski, P.D.; Hawk, J.A. Homogenizing advanced alloys: Thermodynamic and kinetic simulations followed by experimental results. J. Mater. Eng. Perform. 2017, 26, 4–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abvabi, A.; Rolfe, B.; Hodgson, P.; Weiss, M. The influence of residual stress on a roll forming process. Int. J. Mech. Sci. 2015, 101, 124–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Z.Y.; Zhang, D.; Nie, G.C.; Ding, H.; Zhang, X.M. In-situ imaging approach for investigating residual stress formation in rolling process. Int. J. Mech. Sci. 2023, 248, 108220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allegri, G.; Giorleo, L.; Ceretti, E.; Giardini, C. Driver roll speed influence in ring rolling process. Procedia Eng. 2017, 207, 1230–1235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, B.; Hu, W.; Kong, L.; Hodgson, P. The influence of roll speed on the rolling of metal plates. Met. Mater. 1998, 4, 915–919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kojima, S.; Yokoyama, A.; Komatsu, M.; Kiritani, M. High-speed deformation of aluminum by cold rolling. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 2003, 350, 81–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Bian, T.; Li, H.; Yang, X.; Lei, C. Stress relaxation aging of 7050 aluminum alloy under elastic and plastic loadings: A perspective from the geometrically necessary dislocations. J. Alloy. Compd. 2025, 1010, 177066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, J.; Pan, R.; Li, C.; Zhang, W.; Lin, J.; Davies, C.M. Experimental investigation of multi-step stress-relaxation-ageing of 7050 aluminium alloy for different pre-strained conditions. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 2018, 710, 111–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gurrutxaga–Lerma, B.; Verschueren, J.; Sutton, A.P.; Dini, D. The mechanics and physics of high-speed dislocations: A critical review. Int. Mater. Rev. 2021, 66, 215–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yasunaga, K.; Iseki, M.; Kiritani, M. Dislocation structures introduced by high-speed deformation in bcc metals. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 2003, 350, 76–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kiritani, M. Analysis of high-speed-deformation-induced defect structures using heterogeneity parameter of dislocation distribution. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 2003, 350, 63–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mazilkin, A.; Straumal, B.; Rabkin, E.; Baretzky, B.; Enders, S.; Protasova, S.; Kogtenkova, O.A.; Valiev, R.Z. Softening of nanostructured Al–Zn and Al–Mg alloys after severe plastic deformation. Acta Mater. 2006, 54, 3933–3939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, M.P.; Roven, H.J.; Murashkin, M.Y.; Valiev, R.Z.; Kilmametov, A.; Zhang, Z.; Yu, Y. Structure and mechanical properties of nanostructured Al–Mg alloys processed by severe plastic deformation. J. Mater. Sci. 2013, 48, 4681–4688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kupidura, P.; Górski, K.; Jeżowska, W.; Jankowska, A. Analysis of impact of an edge effect on efficacy of selected texture analysis methods. Teledet. Środow. 2015, 53, 15–26. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, B.; Zhu, L.; Xin, Y.; Lei, J. Grain rotation in plastic deformation. Quantum Beam Sci. 2019, 3, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scheriau, S.; Pippan, R. Influence of grain size on orientation changes during plastic deformation. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 2008, 493, 48–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, X.; Zajac, S. The strain-rate dependence of flow stress and work-hardening rate in three Al-Mg alloys. Scand. J. Metall. 2000, 29, 101–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lademo, O.G.; Engler, O.; Benallal, A.; Hopperstad, O.S. Effect of strain rate and dynamic strain ageing on work-hardening for aluminium alloy AA5182-O. Int. J. Mater. Res. 2012, 103, 1035–1041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.; Shankar, R.M.; Liu, Z. Visco-plastic self-consistent modeling of crystallographic texture evolution related to slip systems activated during machining Ti-6AL-4V. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 2021, 853, 157336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Density (g·cm−3) | Young’s Modulus (GPa) | Poisson’s Ratio (—) | Thermal Conductivity (W/(m·K)) | Yield Strength (MPa) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2.85 | 73 | 0.33 | 173 | 325 |

| P | Sn | Sc | Ca | Fe | Cu | Al |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| <0.001 | <0.001 | 0.009 | 0.0011 | 0.012 | 2.69 | Bal. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Zhang, G.; Liu, L.; Li, T.; Tang, S.; Gao, B. Effects of Rolling Parameters on Stress–Strain Fields and Texture Evolution in Al–Cu–Sc Alloy Sheets. Materials 2025, 18, 5414. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma18235414

Zhang G, Liu L, Li T, Tang S, Gao B. Effects of Rolling Parameters on Stress–Strain Fields and Texture Evolution in Al–Cu–Sc Alloy Sheets. Materials. 2025; 18(23):5414. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma18235414

Chicago/Turabian StyleZhang, Guoge, Lijie Liu, Tuo Li, Shan Tang, and Bo Gao. 2025. "Effects of Rolling Parameters on Stress–Strain Fields and Texture Evolution in Al–Cu–Sc Alloy Sheets" Materials 18, no. 23: 5414. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma18235414

APA StyleZhang, G., Liu, L., Li, T., Tang, S., & Gao, B. (2025). Effects of Rolling Parameters on Stress–Strain Fields and Texture Evolution in Al–Cu–Sc Alloy Sheets. Materials, 18(23), 5414. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma18235414