Research in the Commonwealth of Independent States on Superconducting Materials: Current State and Prospects

Highlights

- Superconductivity research across CIS countries;

- Domination of government-funded superconductivity research in CISs;

- Research focuses on Cuprate superconductors with RE doping;

- Studies of near-room-temperature superconductivity in metal hydrides;

- Ultrathin superconducting films by laser/plasma methods.

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Research Finding

3. Superconductivity Research in the Commonwealth of Independent States (CIS)

4. Notable Advances in Enhancing Superconducting Properties

- Solid-phase reaction: Mixing the starting oxides or salts in a certain ratio, calcining (sintering) the mixture at high temperatures, and subsequent pressing and sintering of the material.

- Plasma spray: The starting materials are sprayed in a plasma stream and deposited as a thin layer on a substrate, yielding homogeneous powders with high dispersion.

- Oxidative synthesis: The starting materials undergo oxidation with an organic reagent (e.g., citrate or glycolate). This results in metal–organic complexes that decompose upon heating to produce oxide powders.

- Sol–gel method: The starting materials are dissolved in water or another solvent with the addition of a complexing agent (e.g., acetylacetonate or ethylene glycol). This forms a colloidal solution (sol), which transforms into a gel upon changes in pH or temperature. The gel is then dried and calcined to produce oxide powders.

- Spray drying: A solution of the starting materials is sprayed into a hot gas stream (air), causing rapid evaporation of the solvent and the formation of fine powder particles.

- Acetate method: The starting materials are dissolved in acetic acid with added ammonia or other bases. This forms metal acetates, which are then precipitated from the solution by changing the pH or concentration. The precipitate is dried and calcined to produce the starting powders.

5. Promising Directions in Superconductor Research

6. Conclusions

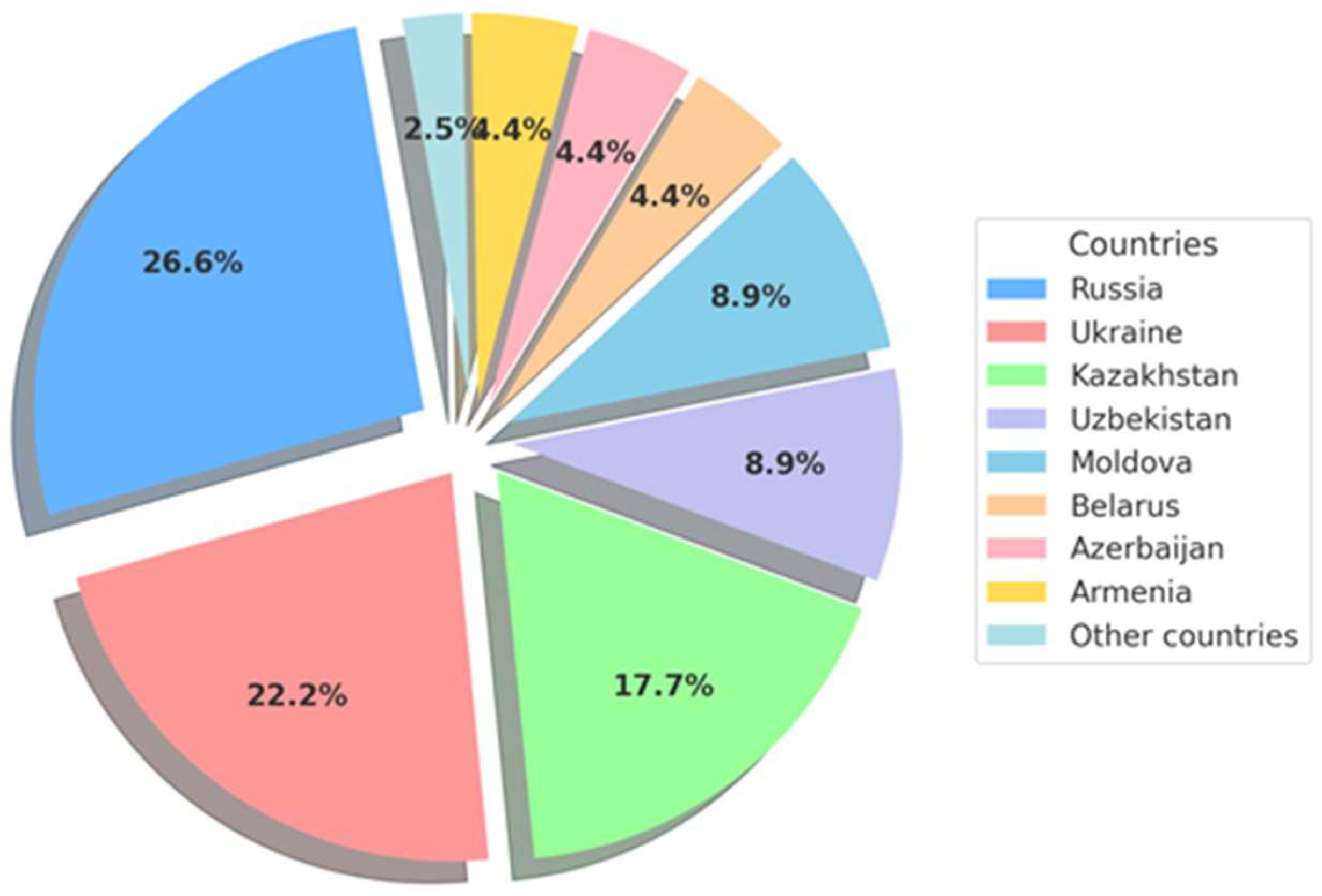

- The greatest contribution to superconducting research comes from scientists in the Russian Federation, particularly from the leading institutions of the Russian Academy of Sciences, such as the P. N. Lebedev Physical Institute (FIAN), A. F. Ioffe Physical-Technical Institute (IPTI), the L. D. Landau Institute for Theoretical Physics (ITF), and the I. A. Osepyan Institute of Solid-State Physics (ISSP).

- At FIAN, under the leadership of Academician V. L. Ginzburg, research on various metal compounds, alloys, ceramic materials based on Nb, Sn, Ge, La, cuprates, iron-containing pnictides, chalcogenides with lanthanides and actinides, and other metals was conducted.

- Research at the A. F. Ioffe Physical-Technical Institute was focused on developing thin superconducting films for radiation detectors, filters, etc. For example, the researchers created superconducting iron-containing membranes in which the critical temperature (Tc) of the FeSe material increased from about 8 K at atmospheric pressure to about 37 K at 9 GPa, accompanied by magnetic ordering. This significant increase in Tc under pressure is a known phenomenon for FeSe, with the highest Tc values observed in thin films or intercalated forms, classifying it as a medium-temperature superconductor.

- The ISSP RAS developed the phenomenological theory of superconductivity and superfluidity, which allows for accurate research results without necessarily explaining the true causes of the phenomena (Nobel Prize-winning theory by Landau and Ginzburg). This theory describes phase transitions involving changes in thermodynamic parameters using the Cooper pair wave function. In 2003, the Nobel Prize in Physics was awarded to A. Abrikosov, V. Ginzburg, and Anthony Leggett for their contributions to the understanding of superconductivity and superfluidity.

- Significant contributions to superconducting research were made by the National Research Nuclear University, with work by Dr. M. I. Yeremets on lanthanum (La, Y)H6 and decahydrides (LaY)H10 with a maximum critical temperature Tc ≈ 253 K, magnetic field B0 ≈ 13.5 T at 183 GPa, and current density 12–27.7 kA/mm2, comparable to NbTa and NbSn at 4.2 K.

- At the L. D. Landau Institute for Theoretical Physics, the main mechanism of superconductivity was found to be the formation of Cooper pairs—weakly bound electron pairs that move without scattering on the atoms of the material’s lattice (electron–phonon interaction in the lattice).

- Publications from Ukraine, Kazakhstan, Belarus, Turkmenistan, Armenia, and Moldova, as well as collaborative works with Russian institutions, demonstrate high-quality research using modern methods and equipment, including techniques for creating low temperatures and producing highly purified components from pure metals, cuprates, iron-containing compounds with rare-earth elements, and other materials.

- It was established that high-temperature superconducting properties are improved when using high-purity materials, high synthesis temperatures, including self-propagating high-temperature synthesis (SHS) methods for preparing film-structured substances using lasers, deposition of high-dispersion nanoscale compounds from gas phases, and other techniques.

- Based on the presented research materials, it is concluded that a promising direction is the production of ultrathin film-structured materials on thin substrates with special properties and the development of technologies for their use. The application of additives in known cuprate superconductors, which form crystalline structures capable of improving superconducting properties and magnetic characteristics, is a significant development. The creation of new technological principles for material production using new methods, such as blending of precursor materials, maintaining the fractional chemical composition, pressing, and spinning under controlled thermal regimes, is also highlighted as a key area of future work. The development and enhancement of SHS technology for new material synthesis remains a priority.

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| CIS | Commonwealth of Independent States |

| HTS | High-temperature superconductors |

| LTS | Low-temperature superconductors |

| MWCT | Multi-walled carbon nanotubes |

| AFM | Antiferromagnetic |

| ARPES | Angularly resolved photoemission spectroscopy |

| SQUID | Superconducting quantum interference device |

| SHS | Self-Propagating High-Temperature Synthesis |

| XRD | X-ray diffraction |

| TRXRD | Time-resolved X-ray diffraction |

| BCS | Bardeen-Cooper-Schrieffer |

| NICA | Nuclotron-based Ion Colliderer &Actility |

| CEF | Crystal electric field |

| SQI | Superconducting quantum interferometer |

| FCC | Future Circular Collider |

References

- Nobuya, B. Low-temperature superconductors: Nb3Sn, Nb3Al, and NbTi. Superconductivity 2023, 6, 100047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sadovskii, M.V. Pseudogap in High-Temperature Superconductors. Physics-Uspekhi 2001, 44, 515–539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poole, C.P.; Farach, H.A.; Creswick, R.J.; Prozorov, R. Superconductivity; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2010; ISBN 978-0-08-055048-0. [Google Scholar]

- Larbalestier, D.; Gurevich, A.; Feldmann, D.M.; Polyanskii, A. High-Tc Superconducting Materials for Electric Power Applications. Nature 2001, 414, 368–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Malozemoff, A.P.; Fleshler, S.; Rupich, M.; Thieme, C.; Li, X.; Zhang, W.; Otto, A.; Maguire, J.; Folts, D.; Yuan, J.; et al. Progress in High Temperature Superconductor Coated Conductors and Their Applications. Supercond. Sci. Technol. 2008, 21, 034005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pęczkowski, P.; Zachariasz, P.; Zalecki, R.; Piętosa, J.; Michalik, J.M.; Jastrzębski, C.; Ziętala, M.; Zając, M.; Gondek, L. Influence of polyurethane skeleton on structural and superconducting properties of Y-123 foams. J. Eur. Ceram. Soc. 2024, 44, 5722–5730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prikhna, T.; Sokolovsky, V.; Moshchil, V. Bulk MgB2 Superconducting Materials: Technology, Properties, and Applications. Materials 2024, 17, 2787. [Google Scholar]

- Goodenough, J.B. Meissner Effect—An Overview|ScienceDirect Topics. Available online: https://www.sciencedirect.com/topics/chemistry/meissner-effect?utm_source (accessed on 25 June 2025).

- Zhizn, R. Journal N. and A New Class of High-Temperature Superconductors—Now at the FIAN. Available online: http://www.nkj.ru/archive/articles/20235 (accessed on 25 June 2025).

- Mitsen, K.V.; Ivanenko, O.M. Phase Diagram of La2–xMxCuO4 as the Key to Understanding the Nature of High-Tc Superconductors. Physics-Uspekhi 2004, 47, 493–510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kopaev, Y.V. High-Temperature Superconductivity Models. Physics-Uspekhi 2002, 45, 655–659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aksenov, V.L. Neutron Scattering by Cuprate High-Temperature Superconductors. Physics-Uspekhi 2002, 45, 645–649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elesin, V.F.; Kapaev, V.V.; Kopaev, Y.V. Coexistence of Ferromagnetism and Nonuniform Superconductivity. Physics-Uspekhi 2004, 47, 949–953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Volkov, E.P.; Vysotsky, V.S.; Firsov, V.P. First Russian Long Length HTS Power Cable. Phys. C Supercond. Its Appl. 2012, 482, 87–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bondarenko, S.I.; Guo, Q.; Fan, J.D.; Sivakov, A.G.; Krevsun, A.V.; Link, S.I. Microscopic Study of the YBa2Cu3O7−x Crystal. Mod. Phys. Lett. B 2018, 32, 1850102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Information Card. Available online: https://is.ncste.kz/icard/view/12289 (accessed on 8 June 2025).

- JINR. Available online: https://www.jinr.ru/about-en/ (accessed on 8 June 2025).

- Academy of Sciences of the Republic of Uzbekistan. Available online: https://www.academy.uz/en (accessed on 1 July 2025).

- Ergashev, I.A.; AN RU, Tashkent (Uzbekistan). Inst. Yadernoj Fiziki. Acoustic Relaxations in High-Temperature Superconductor YBa2Cu3O7-x; AN RU, Tashkent (Uzbekistan). Inst. Yadernoj Fiziki: Tashkent, Uzbekistan, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Heisenberg, W. The role of phenomenological theories in the system of theoretical physics. Adv. Phys. Sci. 1967, 91, 731–733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abrikosov, A.A. QMC Copier. On the Theory of Superconductivity. J. Expti. Theoret. Phys. 1957, 5, 1174–1182. Available online: https://www.physics.umd.edu/courses/Phys798C/AnlageSpring24/Abrikosov_JETP_1957.pdf (accessed on 8 June 2025).

- Moskalenko, V.A. Priority of Moldovan physicists in the creation and development of the multiband theory of superconductivity. Electron. Process. Mater. 2013, 49, 118–121. Available online: https://eom.ifa.md/en/journal/shortview/942 (accessed on 8 September 2025).

- Budagov, Y.A.; Trubnikov, G.V.; Shirkov, G.D.; Baturitsky, M.A.; Bogdanovich, M.V.; Kurochkin, Y.A.; Zalessky, V.G.; Kilin, S.Y.; Azaryan, N.S. Cooperation of JINR with scientific institutions of the Republic of Belarus in the field of superconducting accelerator resonators. Phys. Elem. Part. At. Nucl. 2022, 53, 21–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Academy of Sciences of Belarus. Available online: https://milex.belexpo.by/o-vystavke/spisok-uchastnikov/natsionalnaya-akademiya-nauk-belarus.html (accessed on 29 August 2025).

- Priorities of International Scientific, Technical and Innovative Cooperation of the Republic of Belarus|SCIENCE AND INNOVATIONS—Scientific and Practical Journal. Available online: https://innosfera.by/node/5159 (accessed on 29 August 2025).

- Concept of Turkmenistan’s chairmanship in the Commonwealth of Independent States in 2019. In Proceedings of the 2019 Results of the Meeting of the Council of Heads of Government of the CIS and the list of adopted documents, Ashgabat, Turkmenistan, 31 May 2019; Available online: https://centralasia.news (accessed on 3 July 2025).

- Belyavsky, V.I.; Kopaev, Y.V.; Tuan, N.N. Superconductivity in Cuprate Homological Series: Interlayer Dielectric Coupling of Superconducting Pairs. JETP Lett. 2008, 87, 565–569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eglitis, R.I.; Kotomin, E.A.; Popov, A.I.; Kruchinin, S.P.; Jia, R. Comparative ab initio calculations of SrTiO3, BaTiO3, PbTiO3, and SrZrO3 (001) and (111) surfaces as well as oxygen vacancies. Low Temp. Phys. 2022, 48, 80–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuzmicheva, T.E.; Kuzmichev, S.A. Pnictides of the AFeAs Family (A = Li, Na) Based on Alkali Metals: Current State of Research on Electronic and Superconducting Properties (Mini-Review). ResearchGate 2021, 114, 685–698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuzmichev, S.; Kuzmicheva, T.; Morozov, I.; Boltalin, A.; Shilov, A. Multiple Andreev reflections effect spectroscopy of LiFeAs single crystals: Three superconducting order parameters and their temperature evolution. SN Appl. Sci. 2022, 4, 189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pavlov, N.S.; Shein, I.R.; Pervakov, K.S.; Nekrasov, I.A. Electronic Structure of InCo2As2 and KInCo4As4: LDA + DMFT. Pisʹma V Ž. Êksperimentalʹnoj Teor. Fiz. 2023, 117, 65–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Terekhov, A.V.; Zolochevskii, I.V.; Khristenko, E.V.; Ishchenko, L.A.; Bezuglyi, E.V.; Zaleski, A.; Khlybov, E.P.; Lachenkov, S.A. Anisotropy of electric resistance and upper critical field in magnetic superconductor Dy0.6Y0.4Rh3.85Ru0.15B4. Phys. C Supercond. Its Appl. 2016, 524, 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Cardwell, D.A.; Larbalestier, D.C.; Braginski, A.I. Handbook of Superconductivity: Processing and Cryogenics, Volume Two, 2nd ed.; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2022; ISBN 978-0-429-18302-7. [Google Scholar][Green Version]

- Zlobin, A.V.; Schoerling, D. Superconducting Magnets for Accelerators. In Nb3Sn Accelerator Magnets: Designs, Technologies and Performance; Schoerling, D., Zlobin, A.V., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2019; pp. 3–22. ISBN 978-3-030-16118-7. [Google Scholar][Green Version]

- Director of Nuclear Research Institute: Azerbaijani Scientists Take Part in Such Priority Projects as NICA Collider—INTERVIEW. Available online: https://report.az/en/education-and-science/director-of-nuclear-research-institute-azerbaijani-scientists-take-part-in-such-priority-projects-as-nica-collider-interview (accessed on 1 July 2025).[Green Version]

- Chigvinadze, J.G.; Acrivos, J.V.; Ashimov, S.M.; Gulamova, D.D.; Donadze, G. Superconductivity at T=200K in Bismuth Cuprates Synthesized Using Solar Energy. arXiv 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bezotosnyi, P.I.; Dmitrieva, K.A. Modeling of the Critical State of Layered Superconducting Structures with Inhomogeneous Layers. Phys. Solid State 2021, 63, 1605–1610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ginzburg, V.L. On Superconductivity and Superfluidity (What I Have and Have Not Managed to Do), as Well as on the “physical Minimum” at the Beginning of the XXI Century (December 8, 2003). Physics-Uspekhi 2004, 47, 1155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ginzburg, V.L.; Andryushin, E.A. Superconductivity; World Scientific: Singapore, 2004; ISBN 978-981-256-211-1. [Google Scholar]

- The Nobel Prize in Physics 2003. Available online: https://www.nobelprize.org/prizes/physics/2003/summary (accessed on 8 June 2025).

- Gerbshtein, Y.M.; Nikulin, E.I. High-Temperature Superconductors YBaCu2O5 and Tl1.5BaCa2Cu2.5O8 with a Decreased Content of Heavy Metals (Ba and Tl). Phys. Solid State 2012, 54, 459–461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trojan, I.A.; Semenok, D.V.; Ivanova, A.G.; Kvashnin, A.G.; Zhou, D.; Sadakov, A.V.; Sobolevsky, O.A.; Pudalov, V.M.; Lyubutin, I.S.; Oganov, A.R. High-Temperature Superconductivity in Hydrides. Physics-Uspekhi 2022, 65, 748–761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schlyakhova, G.V.; Barannikova, S.A.; Zuev, L.B. The study of nanostructural elements of superconductive cable Nb-Ti. Izv. Ferr. Metall. 2015, 56, 64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuznetsova, E.I.; Degtyarev, M.V.; Blinova, Y.V.; Sudareva, S.V.; Aksentsev, Y.N.; Pilyugin, V.P. Mechanism of Structure Formation during High-Temperature Annealing of Pressure-Deformed Bulk MgB2 Samples. Phys. Solid State 2017, 59, 1673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anishchenko, I.V.; Pokrovskii, S.V.; Rudnev, I.A. Simulation of Magnetic Levitation Systems Based on Superconducting Rings. Bull. Lebedev Phys. Inst. 2018, 45, 373–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osipov, M.; Starikovskii, A.; Abin, D.; Rudnev, I. Influence of the Critical Current on the Levitation Force of Stacks of Coated Conductor Superconducting Tapes. Supercond. Sci. Technol. 2019, 32, 054003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chair of Atomic Physics, Plasma Physics and Microelectronics. Available online: https://affp.phys.msu.ru/index.php/en/ (accessed on 1 September 2025).

- Rudnev, I.; Abin, D.; Osipov, M.; Pokrovskiy, S.; Ermolaev, Y.; Mineev, N. Magnetic Properties of the Stack of HTSC Tapes in a Wide Temperature Range. Phys. Procedia 2015, 65, 141–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leon, N. Cooper—Nobel Lecture. Available online: https://www.nobelprize.org/uploads/2018/06/cooper-lecture.pdf (accessed on 1 July 2025).

- Shnyrkov, V.I.; Yangcao, W.; Soroka, A.A.; Turutanov, O.G.; Lyakhno, V.Y. Frequency-tunable microwave photon counter based on a superconducting quantum interferometer. Low Temp. Phys. 2018, 44, 281–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amosov, A.P.; Borovinskaya, I.P. Powder Technology of Self-Propagating High-Temperature Synthesis of Materials. Available online: https://elibrary.ru/owgpcl (accessed on 1 June 2025).

- Prigozhin, L.; Sokolovsky, V. Computing AC Losses in Stacks of High-Temperature Superconducting Tapes. Supercond. Sci. Technol. 2011, 24, 075012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rabadanova, A.E.; Gadzhimagomedov, S.K.; Palchaev, D.K.; Murlieva, Z.K. Properties of YBCO Ceramics Depending on Oxygen Doping. Her. Dagestan State Univ. 2022, 37, 42–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pokrovskiy, S.; Mineev, N.; Sotnikova, A.; Ermolaev, Y.; Rudnev, I. The Study of Relaxation Characteristics of Stack of HTS Tapes for Use in Levitation Systems and Trapped Flux Magnets. J. Phys. Conf. Ser. 2014, 507, 022025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abin, D.; Osipov, M.; Pokrovskii, S.; Rudnev, I. Relaxation of Levitation Force of a Stack of HTS Tapes. IEEE Trans. Appl. Supercond. 2016, 26, 8800504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bondarenko, S.I.; Krevsun, A.V.; Ilichev, E.V.; Hubner, U.; Koverya, V.P.; Link, S.I. Thin Film Superconducting Quantum Interferometer with Ultralow Inductance. Low Temp. Phys. 2018, 44, 184–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kostyurina, E.A.; Kalashnikov, K.V.; Filippenko, L.V.; Kiselev, O.S.; Koshelets, V.P. Highly symmetric superconducting quantum DC interferometer on Nb/AlO/Nb Josephson junctions for non-destructive testing systems of materials. Radio Eng. Electron. 2017, 62, 1142–1147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korobova, N.E.; Ketegenov, T.A.; Tyumentseva, O.A. Method for Producing High-Temperature Superconducting Films. Patent of the Republic of Kazakhstan No. 20707 Bulletin No. 1 (IPG), 15 January 2009. Available online: https://kz.patents.su/3-ip20707-sposob-polucheniya-vysokotemperaturnyh-sverhprovodyashhih-plenok.html (accessed on 1 July 2025).

- Tonoyan, A.O.; Arapkelyan, E.R.; Hayryapetyan, S.M.; Mamalis, A.G.; Davtyan, S.P. On Some Issues of Obtaining Polymer-Ceramic Superconducting Kmpositions. Chem. J. Armen. 2001, 54, 65–74. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/273122103 (accessed on 1 July 2025).

- Bologa, M.K. Research and Innovations at the Institute of Applied Physics. Evolution and Achievements. Electron. Process. Mater. 2006, 42, 4–91. [Google Scholar]

- Schmidt, V.V. The Physics of Superconductors: Introduction to Fundamentals and Applications; Springer Science & Business Media: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2013; ISBN 978-3-662-03501-6. [Google Scholar]

- Sadovskii, M.V. High-Temperature Superconductivity in Iron-Based Layered Compounds. Physics-Uspekhi 2008, 51, 1201–1227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Popova, E.N.; Popov, V.V.; Romanov, E.P.; Sudareva, S.V.; Dergunova, E.A.; Vorobyova, A.E.; Balaev, S.M.; Shikov, A.K. Effect of doping, composite geometry and diffusion annealing schedules on the structure of Nb3Sn layers in Nb/Cu-Sn wires. Defect Diffus. Forum 2008, 273–276, 514–519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levashov, E.A.; Rogachev, A.S.; Kurbatkina, V.V. Promising Materials and Technologies of Self-Propagating High-Temperature Synthesis—Read in the Electronic Library System Znanium. Available online: https://znanium.ru/catalog/document?id=370115 (accessed on 1 June 2025).

- Rosenband, V.; Gany, A. Thermal Explosion Synthesis of a Magnesium Diboride Powder. Combust. Explos. Shock. Waves 2014, 50, 653–657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lebrat, J.P.; Varma, A. Combustion Synthesis of the YBa2Cu3O7−x Superconductor. Phys. C Supercond. 1991, 184, 220–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miloshenko, V.E.; Kalyadin, O.V.; Yu, V. Izmailov Effect of magnetic field on freely moving superconductors in the audio frequency range. J. Tech. Phys. 2009, 79, 97–103. Available online: https://journals.ioffe.ru/articles/viewPDF/9665 (accessed on 4 June 2025).

- Pokrovskii, S.; Osipov, M.; Abin, D.; Rudnev, I. Magnetization and Levitation Characteristics of HTS Tape Stacks in Crossed Magnetic Fields. IEEE Trans. Appl. Supercond. 2016, 26, 8201304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romanovskii, V.R. Thermal Mechanisms of Irreversible Destruction of Superconducting Properties of Technical Superconductors. J. Tech. Phys. 2017, 87, 1185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Podlivaev, A.; Rudnev, I. A New Method of Reconstructing Current Paths in HTS Tapes with Defects. Supercond. Sci. Technol. 2017, 30, 035021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romanovskii, V.R. Thermoelectrodynamic Mechanisms of the Growth of Current–Voltage Characteristics of Technical Superconductors under Magnetic Flux Creep. Tech. Phys. 2017, 62, 58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anischenko, I.V.; Pokrovskii, S.V.; Rudnev, I.A. Simulation of Magnetization and Heating Processes in HTS Tapes Stacks. J. Phys. Conf. Ser. 2019, 1238, 012020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anischenko, I.V.; Pokrovskii, S.V.; Rudnev, I.A. The Dynamic Processes in Second Generation HTS Tapes under the Pulsed Current and Magnetic Impact. J. Phys. Conf. Ser. 2019, 1389, 012064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurbatova, E.; Kushchenko, E.; Kurbatov, P. Comparison of Magnetic Systems with HTS Bulks and HTS Tape for Non-Contact Bearings. In Proceedings of the 2020 21st International Symposium on Electrical Apparatus & Technologies (SIELA), Bourgas, Bulgaria, 3–6 June 2020; pp. 1–4. [Google Scholar]

- Rusakov, V.A.; Melekh, B.A.-T.; Volkov, M.P. Forming the Fe(Se1 –xTex) Superconducting Coatings on the Iron Surface. Tech. Phys. 2020, 65, 63–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antonov, A.V.; El’kina, A.I.; Vasiliev, V.K.; Galin, M.A.; Masterov, D.V.; Mikhaylov, A.N.; Morozov, S.V.; Pavlov, S.A.; Parafin, A.E.; Tetelbaum, D.I.; et al. Experimental Observation of S-Component of Superconducting Pairing in Thin Disordered HTSC Films Based on YBCO. Phys. Solid State 2020, 62, 1598–1603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- About ISSP RAS. Available online: http://www.issp.ac.ru/main/index.php/en/about-issp.html (accessed on 1 July 2025).

- Kordyuk, A.A. Pseudogap from ARPES Experiment: Three Gaps in Cuprates and Topological Superconductivity (Review Article). Low Temp. Phys. 2015, 41, 319–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kordyuk, A.A.; Krabbes, G.; Nemoshkalenko, V.V.; Viznichenko, R.V. Surface influence on flux penetration into HTS bulks. Phys. B Condens. Matter 2000, 284–288, 903–904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borisenko, S.V.; Zabolotnyy, V.B.; Kordyuk, A.A.; Evtushinsky, D.V.; Kim, T.K.; Carleschi, E.; Doyle, B.P.; Fittipaldi, R.; Cuoco, M.; Vecchione, A.; et al. Angle-resolved photoemission spectroscopy at ultra-low temperatures. J. Vis. Exp. JoVE 2012, 68, 50129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solovyov, I.I.; Kornev, V.K.; Klenov, N.V.; Sharafiev, A.V.; Kalabukhov, A.S.; Chuharkin, M.L.; Snigirev, O.V. Microwave Amplifier Based on a High-Temperature SQUID with Four Josephson Junctions—Patent|ISTINA—Intellectual System for Thematic Research of Scientometric Data. Available online: https://istina.ips.ac.ru/patents/5382370/ (accessed on 25 June 2025).

- Degtyarenko, P.N.; Sadakov, A.V.; Ovcharov, A.V.; Degtyarenko, A.Y.; Gavrilkin, S.Y.; Sobolevskiy, O.A.; Tsvetkov, A.Y.; Massalimov, B.I. Influence of the Gd Concentration on Superconducting Properties in Second-Generation High-Temperature Superconducting Wires. Pisʹma V Ž. Êksperimentalʹnoj Teor. Fiz. 2023, 118, 590–595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kir’yakov, N.V.; Grigoryan, E.A.; Sikharulidze, G.G.; Morozov, Y.G.; Nersesyan, M.D.; Peresada, A.G.; Merzhanov, A.G. Investigation into the Processes of Gas Evolution from HTSC-Ceramics Y-Ba-Cu-O During Vacuum Heat Treatment. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/305683658 (accessed on 25 June 2025).

- Potanin, A.Y.; Levashov, E.A.; Kovalev, D.Y. Dynamics of Phase Formation During Synthesis of Magnesium Diboride from Elements in Thermal Explosion Mode. Powder Metall. Funct. Coat. 2016, 3, 12–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Opata, Y.A.; Monteiro, J.F.H.L.; Jurelo, A.R.; Siqueira, E.C. Critical Current Density in (YBa2Cu3O7−δ)1−x–(PrBa2Cu3O7−δ)x Melt-Textured Composites. Phys. C Supercond. Its Appl. 2018, 549, 107–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahn, B.T.; Beyers, R.B.; Lee, W.Y. Methods for Producing Tl2Ca2Ba2Cu3 Oxide Superconductors 1994. Available online: https://patents.google.com/patent/US5306698 (accessed on 20 June 2025).

- Tolendiuly, S.; Fomenko, S.M.; Abdulkarimova, R.G.; Mansurov, Z.A.; Dannangoda, G.C.; Martirosyan, K.S. The Effect of MWCNT Addition on Superconducting Properties of MgB2 Fabricated by High-Pressure Combustion Synthesis. Int. J. Self-Propagating High-Temp. Synth. 2016, 25, 97–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tolendiuly, S.; Fomenko, S.M.; Dannangoda, G.C.; Martirosyan, K.S. Self-Propagating High Temperature Synthesis of MgB2 Superconductor in High-Pressure of Argon Condition. Eurasian Chem.-Technol. J. 2017, 19, 177–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tolendiuly, S.; Alipbayev, K.A.; Fomenko, S.M.; Sovet, A.; Zhauyt, A. Effect graphite on magnesium diboride superconductivity synthesized by combustion method under argon pressure: Part I. Metalurgija 2022, 61, 285–288. [Google Scholar]

- Tolendiuly, S.; Alipbayev, K.A.; Fomenko, S.M.; Sovet, A.; Zhauyt, A. Effect graphite on magnesium diboride superconductivity synthesized by combustion method under argon pressure: Part II. Metalurgija 2022, 61, 385–388. [Google Scholar]

- Tolendiuly, S.; Fomenko, S.M.; Abdulkarimova, R.G.; Akishev, A. Synthesis and Superconducting Properties of the MgB2@BaO Composites. Inorg. Nano-Met. Chem. 2020, 50, 349–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tolendiuly, S.; Sovet, A.; Fomenko, S. Effect of Doping on Phase Formation in YBCO Composites. J. Compos. Sci. 2023, 7, 517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dautov, L.M.; Kalauov, B.P.; Kusainov, S.K. New Tendencies in the Superconductivity Interpretation. I. Izv. Natsionalnoj Akad. Nauk Resp. Kazakhstan Seriya Fiz.-Mat. 2006, 6, 9–16. Available online: https://inis.iaea.org/records/nm45e-vg187 (accessed on 2 June 2025).

- Afanasyev, D.A.; Ibraev, N.K.; Huangbai, E.; Kazakhstan Patent Database. Method for Obtaining High-Temperature Superconducting Films. IP 20592, 15 December 2008. Available online: https://kz.patents.su/3-ip20592-sposob-polucheniya-vysokotemperaturnyh-sverhprovodyashhih-plenok.html#top (accessed on 29 August 2025).

- Krasil’nikov, V.N.; Zhukov, V.P.; Chulkov, E.V.; Baklanova, I.V.; Kellerman, D.G.; Gyrdasova, O.I.; Dyachkova, T.V. Novel method for the production of copper (II) formates, their thermal, spectral and magnetic properties. J. Alloys Compd. 2020, 845, 156208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dergunova, E. Age of Superconductors. Available online: https://atomicexpert.com/age_of_superconductors (accessed on 25 June 2025).

- In Russia, a Mecca of Superconductors. Available online: https://www.iter.org/node/20687/russia-mecca-superconductors (accessed on 25 June 2025).

- Golovashkin, A.I.; Zherikhina, L.N.; Tskhovrebov, A.M.; Izmailov, G.N. Supersensitive SQUID/Magnetostrictor Detecting System. Quantum Electron. 2012, 42, 1140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maksimov, E.G. About Ginzburg—Landau, and a Bit about Others. Physics-Uspekhi 2010, 53, 1185–1190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mineev, V.P. About Landau Institute. Available online: https://www.itp.ac.ru/en/about/ (accessed on 1 July 2025).

- Bardeen, J.; Cooper, L.N.; Schrieffer, J.R. Theory of Superconductivity. Phys. Rev. 1957, 108, 1175–1204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feigelman, M.V.; Kamenev, A.; Larkin, A.I.; Skvortsov, M.A. Weak charge quantization on a superconducting island. Phys. Rev. B 2002, 66, 054502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Carbotte, J.P. Properties of Boson-Exchange Superconductors. Rev. Mod. Phys. 1990, 62, 1027–1157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tinkham, M. Introduction to Superconductivity; McGraw-Hill: Columbus, OH, USA, 1975; ISBN 978-0-07-064877-7. [Google Scholar]

- Zhetpisbaev, K.; Kumekov, S.; Mohd Suib, N.R.; Abd-Shukor, R. Effect of complex magnetic oxides nanoparticle on (Bi1.6Pb0.4)Sr2Ca2Cu3O10 superconductor prepared by co-precipitation method. AIP Conf. Proc. 2017, 1838, 020009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhetpisbaev, K.; Kumekov, S.; Mohd Suib, N.R.; Abu Bakar, I.P.; Abd-Shukor, R. Effect of Co0.5Zn0.5Fe2O4 Nanoparticle on AC Susceptibility and Electrical Properties of YBa2Cu3O7-δ Superconductor. Int. J. Electrochem. Sci. 2019, 14, 279–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korobova, N.E.; Ketegenov, T.A.; Tyumentseva, O.A. Method for Producing High-Temperature Superconducting Films. Patent of the Republic of Kazakhstan No. 21352 Bulletin No. 6, 15 June 2009. Available online: https://kz.patents.su/3-ip21352-sposob-polucheniya-vysokotemperaturnyh-sverhprovodyashhih-plenok.html (accessed on 1 July 2025).

- Tonoyan, A.O.; Davtian, S.P.; Martirosian, S.A.; Mamalis, A.G. High-temperature superconducting polymer–ceramic compositions. J. Mater. Process. Technol. 2001, 108, 201–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lakhno, V.D. Pseudogap Isotope Effect as a Probe of Bipolaron Mechanism in High Temperature Superconductors. Materials 2021, 14, 4973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Technology Developed for NICA Became Breakthrough in Applied Field. Joint Institute for Nuclear Research, 27 December 2022. Available online: https://www.jinr.ru/posts/technology-developed-for-nica-became-breakthrough-in-applied-field (accessed on 10 July 2025).

- Mitsen, K.V.; Ivanenko, O.M. Superconducting Phase Diagrams of Cuprates and Pnictides as a Key to Understanding the HTSC Mechanism. Physics-Uspekhi 2017, 60, 402–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aksenov, V.L. Pulsed Nuclear Reactors in Neutron Physics. Physics-Uspekhi 2009, 52, 406–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avdeev, M.V.; Aksenov, V.L. Small-Angle Neutron Scattering in Structure Research of Magnetic Fluids. Physics-Uspekhi 2010, 53, 971–993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maksimov, E.G.; Dolgov, O.V. A Note on the Possible Mechanisms of High-Temperature Superconductivity. Physics-Uspekhi 2007, 50, 933–937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vinnikov, L.Y.; Veshchunov, I.S.; Sidel’nikov, M.S.; Stolyarov, V.S.; Egorov, S.V.; Skryabina, O.V.; Jiao, W.; Cao, G.; Tamegai, T. Direct Observation of Vortex and Meissner Domains in a Ferromagnetic Superconductor EuFe2(As0.79P0.21)2 Single Crystal. JETP Lett. 2019, 109, 521–524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pustovit, Y.V.; Prokopenko, O.V.; Kurdyumov, G.V.; Kordyuk, A.A. Anomalous Downshift of Electronic Bands in Fe(Se, Te) in Superconducting State. Metallofiz. I Noveishie Tekhnologii 2020, 42, 1609–1615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Country | Key Institutions/Research Centers | Research Focus | Notable Materials Studied | Significant Achievements/Findings | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Armenia | National Academy of Sciences of Armenia | Polymer-ceramic superconducting nanocomposites | YBCO composites | Improved Tc by copolymerization with metals | [18,19] |

| Azerbaijan | High-Energy Physics Lab (JINR, Dubna) | Superconducting systems for colliders | Proton and heavy-ion superconducting systems | Participation in NICA collider project | [20] |

| Belarus | National Academy of Sciences of Belarus, Scientific and Practical Center of the National Academy of Sciences of Belarus for Materials Science. National Center for Particle and High Energy Physics of Belarus State University, the Research Institute for Nuclear Problems of BSU, the Belarusian State University of Informatics and Radioelectronics. | Application in medical equipment, superconducting resonators | Nb-based superconductors | Development of niobium resonators for MRI and accelerators | [21,22,23,24,25,26] |

| Kazakhstan | Institute of Combustion Problems, Toraighyrov University, Karaganda University, Ulba Metallurgical Plant | MgB2 synthesis via SHS, doping effects, HTS films and composites | MgB2, YBCO, Bi-2223, NZFO-doped superconductors | High Jc values from CNT/MgB2, SHS optimization, substrate temperature effects on Tc | [27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34] |

| Moldova | Institute of Applied Physics | Multi-band superconductors, anisotropic properties | MgB2, borocarbides | Theoretical modeling of anisotropic spectra | [35,36] |

| Russia | P. N. Lebedev Physical Institute, Ioffe Institute, ISMAN, L. D. Landau Institute, Kurchatov Institute, the Physics Department of Moscow State University, the Moscow Institute of Physics and Technology, the University of Science and Technology MISIS, the Moscow Aviation Institute. Nuclear University “MEPhI” | HTS and LTS synthesis, BCS theory, phase transitions, hydrides, SHS, pseudogap physics | Nb3Sn, MgB2, YBCO, Tl-based cuprates, La-Y hydrides, FeN4H4 | Hydrides with Tc up to 253 K, SHS of YBCO, pseudogap theory, Abrikosov vortices, MgB2 synthesis via SHS | [15,24,37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44,45,46,47,48,49,50] |

| Ukraine | G. V. Kurdyumov Institute for Metal Physics (IMP), Kyiv Academic University, B. I. Verkin Institute | Electronic structure, HTS mechanisms, vortex matter, amorphous and iron-based superconductors | Cuprates, borides, FeSe, In-Sn alloy, amorphous superconductors | ARPES studies of HTS, SQI with ultra-low inductance, electronic structure mapping, vortex dynamics, levitation methods | [16,50,51,52,53,54,55,56,57] |

| Uzbekistan | National Academy of Sciences of Uzbekistan, Physico-Technical Institute | Doped cuprates, polarons, solar furnace synthesis | LSCO, Bi-2212 | Formation of pseudogaps, HTS synthesis via solar furnace | [58,59,60] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Tolendiuly, S.; Akishev, A.; Fomenko, S.; Nur-Akasyah, J.; Ilhamsyah, A.B.P.; Rakhym, N. Research in the Commonwealth of Independent States on Superconducting Materials: Current State and Prospects. Materials 2025, 18, 4299. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma18184299

Tolendiuly S, Akishev A, Fomenko S, Nur-Akasyah J, Ilhamsyah ABP, Rakhym N. Research in the Commonwealth of Independent States on Superconducting Materials: Current State and Prospects. Materials. 2025; 18(18):4299. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma18184299

Chicago/Turabian StyleTolendiuly, Sanat, Adil Akishev, Sergey Fomenko, Jaafar Nur-Akasyah, Abu Bakar Putra Ilhamsyah, and Nursultan Rakhym. 2025. "Research in the Commonwealth of Independent States on Superconducting Materials: Current State and Prospects" Materials 18, no. 18: 4299. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma18184299

APA StyleTolendiuly, S., Akishev, A., Fomenko, S., Nur-Akasyah, J., Ilhamsyah, A. B. P., & Rakhym, N. (2025). Research in the Commonwealth of Independent States on Superconducting Materials: Current State and Prospects. Materials, 18(18), 4299. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma18184299