2.1. Voltage Issues in Wind Farms

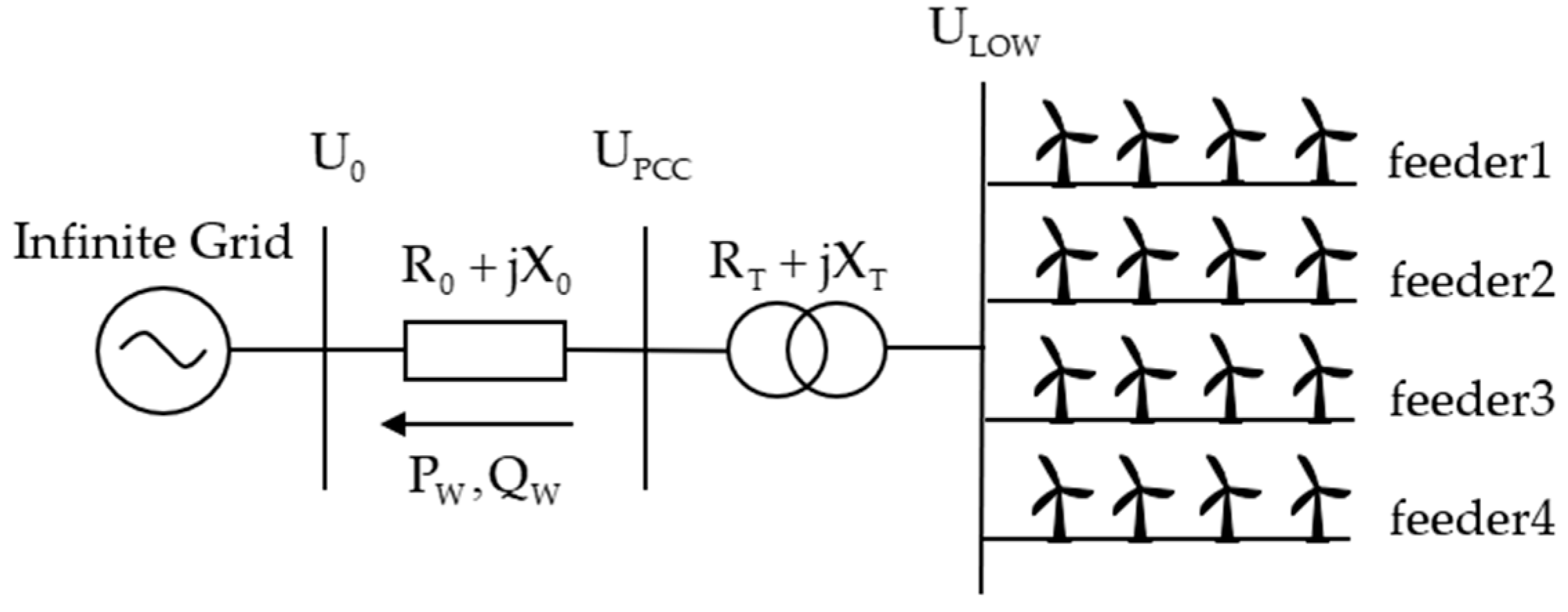

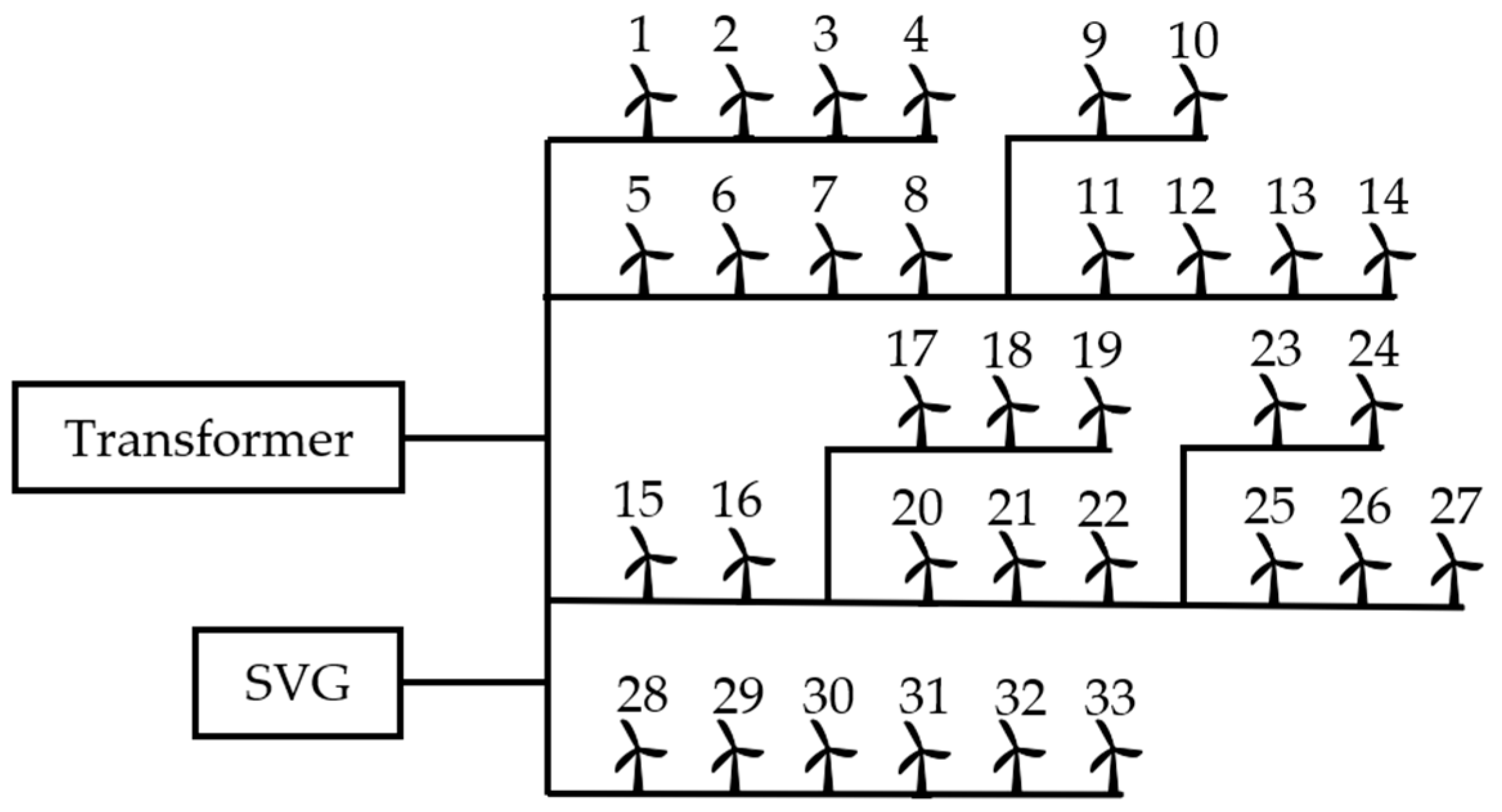

The wiring configuration of a wind farm’s collector system typically involves a single busbar or sectionalized single busbar at the low-voltage side of the farm’s step-up substation. Each busbar section supplies several feeders, where each feeder adopts a radial configuration with a trunk line to connect multiple wind turbine units. For large-scale wind farms, each feeder can typically link 10 to 12 turbine units. The high-voltage busbar of the step-up substation is connected to the main AC grid via transmission lines, as illustrated in

Figure 1.

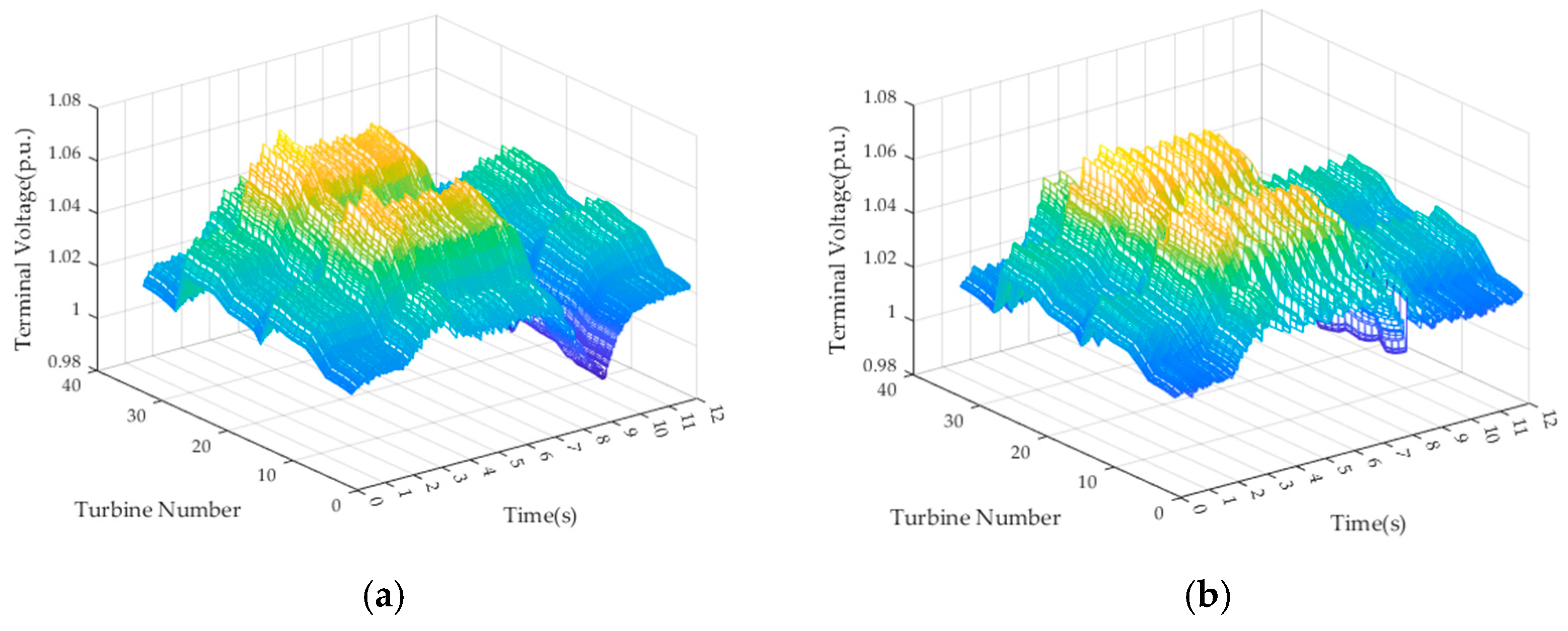

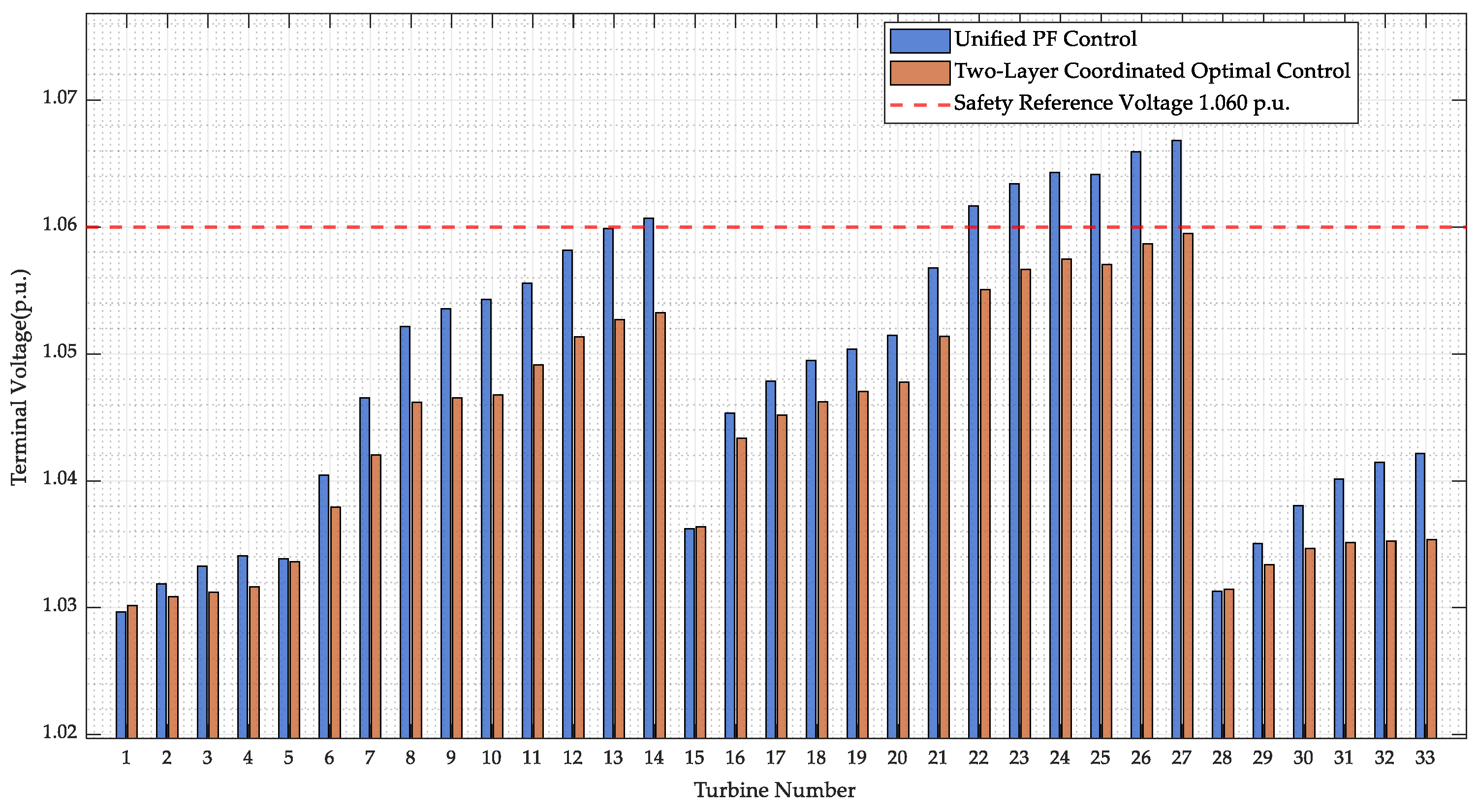

In a typical large-scale wind farm in China, there are over a hundred wind turbine units. Depending on the terrain, the distance between each unit ranges from several hundred meters to several kilometers. Consequently, the length of a feeder from start to end often spans several kilometers to several tens of kilometers. According to data measured from a specific wind farm, under heavy load conditions, the voltage difference between the low-voltage busbar at the wind farm’s step-up substation and the terminal node of a feeder can reach 5%. Therefore, reactive power and voltage control in a wind farm should not only focus on the PCC (Point of Common Coupling) voltage but also consider the internal voltage distribution within the wind farm.

First, the PCC voltage of the wind farm and its variation patterns are analyzed. Assume the wind farm contains multiple feeders connected in a radial trunk configuration, with each feeder supplying multiple wind turbine units and possibly having other branch lines, forming a radial distribution. Z

1 = R

1 + jX

1 represents the impedance of the collector line between adjacent wind turbine units (assuming equal distance between units), typically using cables for power transmission. Z

T = R

T + jX

T is the impedance of the wind farm’s step-up transformer. Z

0 = R

0 + jX

0 is the impedance of the transmission line exporting power from the wind farm, usually using overhead lines for transmission. The analysis begins with the PCC bus voltage of the wind farm. The PCC bus voltage is primarily determined by the system bus voltage U

0 and the voltage drop along the wind farm’s export line. According to the transmission line voltage drop calculation, neglecting the transverse component, the voltage at the wind farm’s point of common coupling (PCC) can be expressed as:

U

PCC represents the voltage at the PCC (Point of Common Coupling) bus of the wind farm, U

0 denotes the voltage at the infinite grid bus, while P

W and Q

W are the active power and reactive power output from the wind farm node, respectively. Although the reactance of high-voltage transmission lines is typically greater than their resistance, the active power output of a wind farm is often significantly larger than its reactive power output. Therefore, it is necessary to account for the impact of fluctuations in the wind farm’s active power output on the PCC voltage. Currently, wind turbine units usually operate at a constant power factor, which can be adjusted within a certain range, either leading or lagging. Based on Equation (1), the variation pattern of the wind farm’s PCC voltage can be expressed as:

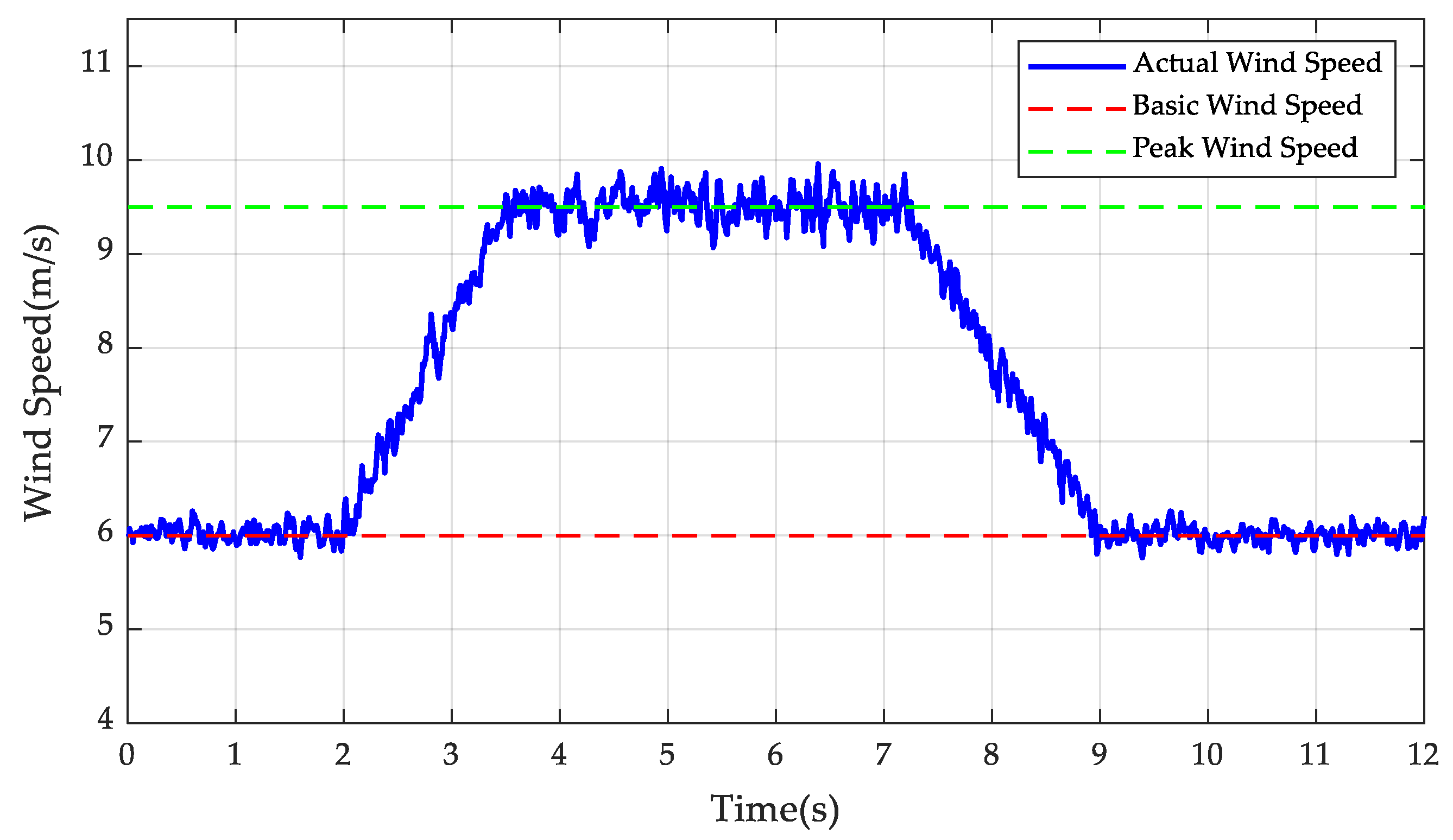

Therefore, changes in wind speed will cause fluctuations in the active power output of the wind farm. The impact of these fluctuations on the voltage at the point of common coupling (PCC) is not only related to the impedance of the transmission line but also to the operating power factor of the wind farm. By promptly adjusting the operating power factor and increasing or decreasing the reactive power output, fluctuations in the voltage at the point of common coupling (PCC) can be effectively suppressed.

Next, the variation pattern of the terminal voltage of wind turbine units is analyzed. Based on the PCC voltage of the wind farm, the expression for the terminal voltage of each turbine unit can also be derived as follows:

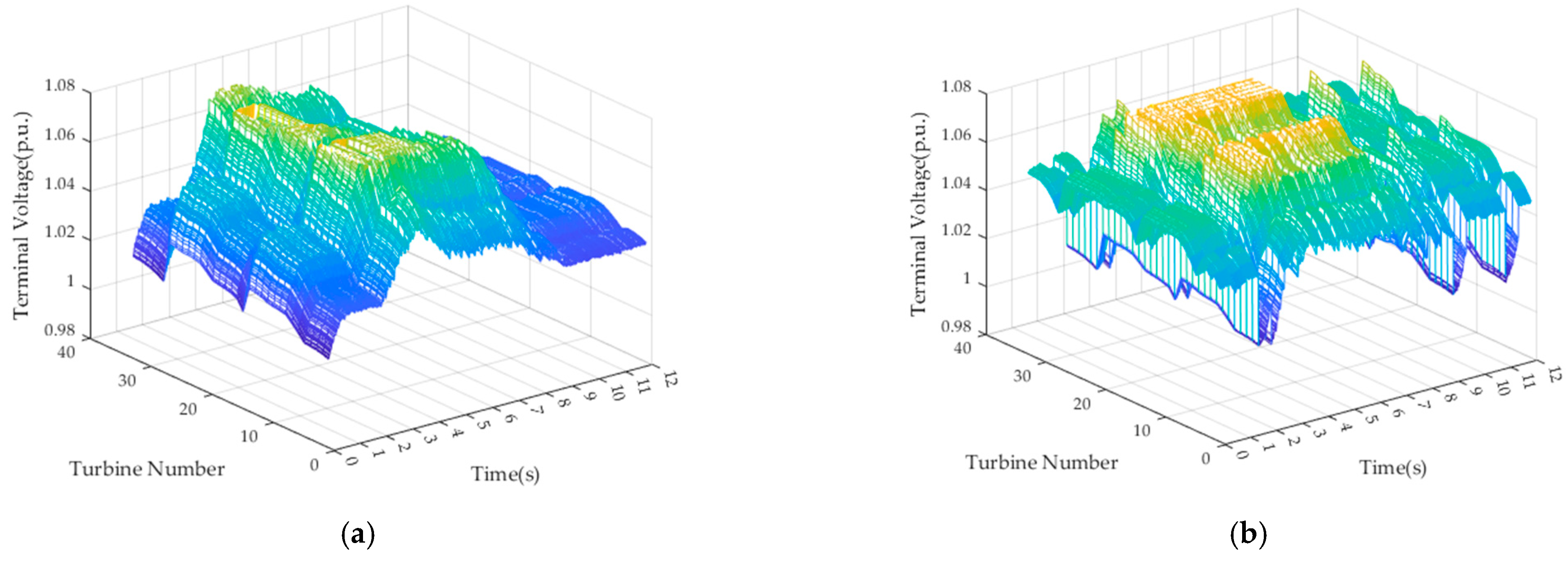

ULN represents the rated voltage of the internal feeder network in the wind farm. By neglecting the impedance of the unit’s box-type transformer and expressing all voltage parameters in per-unit values, it can be seen that the voltage level of the wind turbine units primarily depends on the voltage of the wind farm’s PCC bus. When the PCC bus voltage is either too high or too low, the voltages of the units within the wind farm will correspondingly increase or decrease. Therefore, wind farm voltage control should first aim to keep the PCC bus voltage within a reasonable range. On the other hand, the terminal voltage of a unit is also related to its active and reactive power output. Fluctuations in power output will similarly cause fluctuations in the terminal voltage. Thus, even when the wind farm’s PCC bus voltage is controlled within a reasonable range, the terminal voltage of individual units may still deviate due to changes in the power flow distribution along the collector lines. Variations in the active power output of the units mainly originate from changes in wind speed, while the reactive power depends on the unit’s reactive power control strategy.

Based on the above analysis, it can be concluded that the voltage drop along the collector lines within the wind farm cannot be entirely ignored [

19]. This results in a gradual increase in the voltage distribution at the nodes of the wind turbine units from the beginning to the end of the feeder. When the wind farm participates in providing auxiliary voltage support to the system, even if the voltage at the PCC is maintained within the target range, some turbine units at the end of the feeders within the farm may still experience high voltage limits. This can cause these units to either malfunction or trigger high-voltage protection actions, leading to their disconnection from the grid, thereby compromising the safe operation of the system [

20].

2.2. Optimal Power Flow Problem and Second-Order Cone Relaxation Technique

The essence of reactive power optimization in wind farms is the optimal power flow problem, which is one of the most common optimization problems in power systems. It involves adjusting relevant parameters of generators or loads by controlling associated power devices, under the premise of satisfying physical constraints of the power network, such as system stable operation and security constraints, to optimize objective functions such as total generation cost and total network losses. The objective functions or constraint equations of the optimal power flow problem are typically nonlinear, and the optimization variables may be continuous or discrete. The standard form of the optimal power flow problem is as follows:

In Equation (4), u and x are the optimization variables; f(u, x) represents the objective function to be optimized; g(u, x) denotes the equality constraints; and h(u, x) represents the inequality constraints. The variables in the optimal power flow (OPF) problem characterize the operational state of the power system, typically including bus voltage magnitudes and phase angles, as well as variables for active and reactive power injections at the buses.

However, due to the non-convexity introduced by quadratic power flow constraints, the OPF problem is a non-convex optimization problem that is difficult to solve precisely and is prone to converging to local solutions during the solution process. Therefore, an efficient solution of the OPF problem relies on advances in convex optimization theory.

The main idea of convex relaxation methods is to transform part of the non-convex constraints into a convex optimization problem concerning new variables through variable substitution. The global optimal solution of the convex optimization problem can then be obtained. Optimization using convex relaxation methods is highly efficient, and under exact relaxation conditions, it guarantees obtaining the global optimal solution of the original problem within polynomial time. Among these, convex relaxation techniques represented by second-order cone programming relaxation have been widely applied in solving the OPF problem.

Second-order cone programming, as a special type of convex optimization problem, can be mathematically expressed as follows:

In the equation, x represents the optimization variable; Ai denotes the coefficients of the second-order cone constraints. Second-order cone programming lies between linear programming and semidefinite programming, belonging to the category of convex optimization problems. When Ai = 0, the second-order cone programming problem reduces to a linear optimization problem; when ci = 0, it transforms into a quadratically constrained quadratic programming problem.

However, its limitations primarily require a radial network topology and sensitivity to the magnitude of impedance parameters, which may result in excessive clearance or failure to solve.

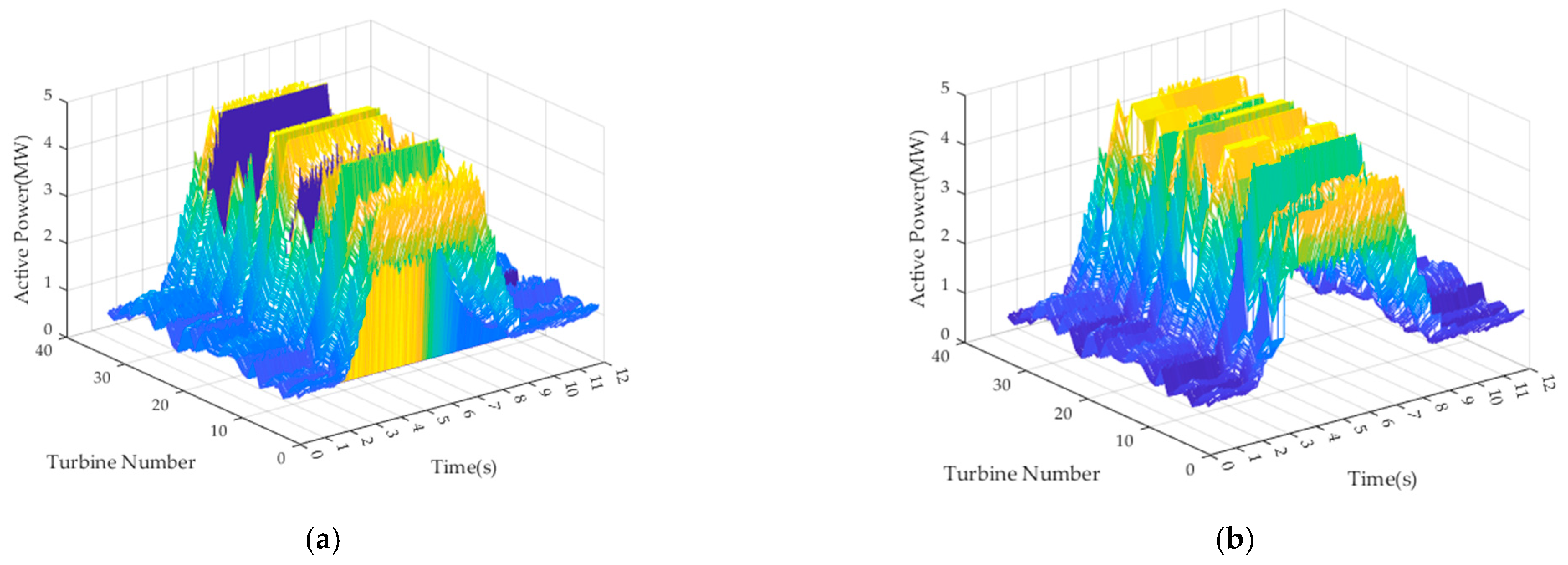

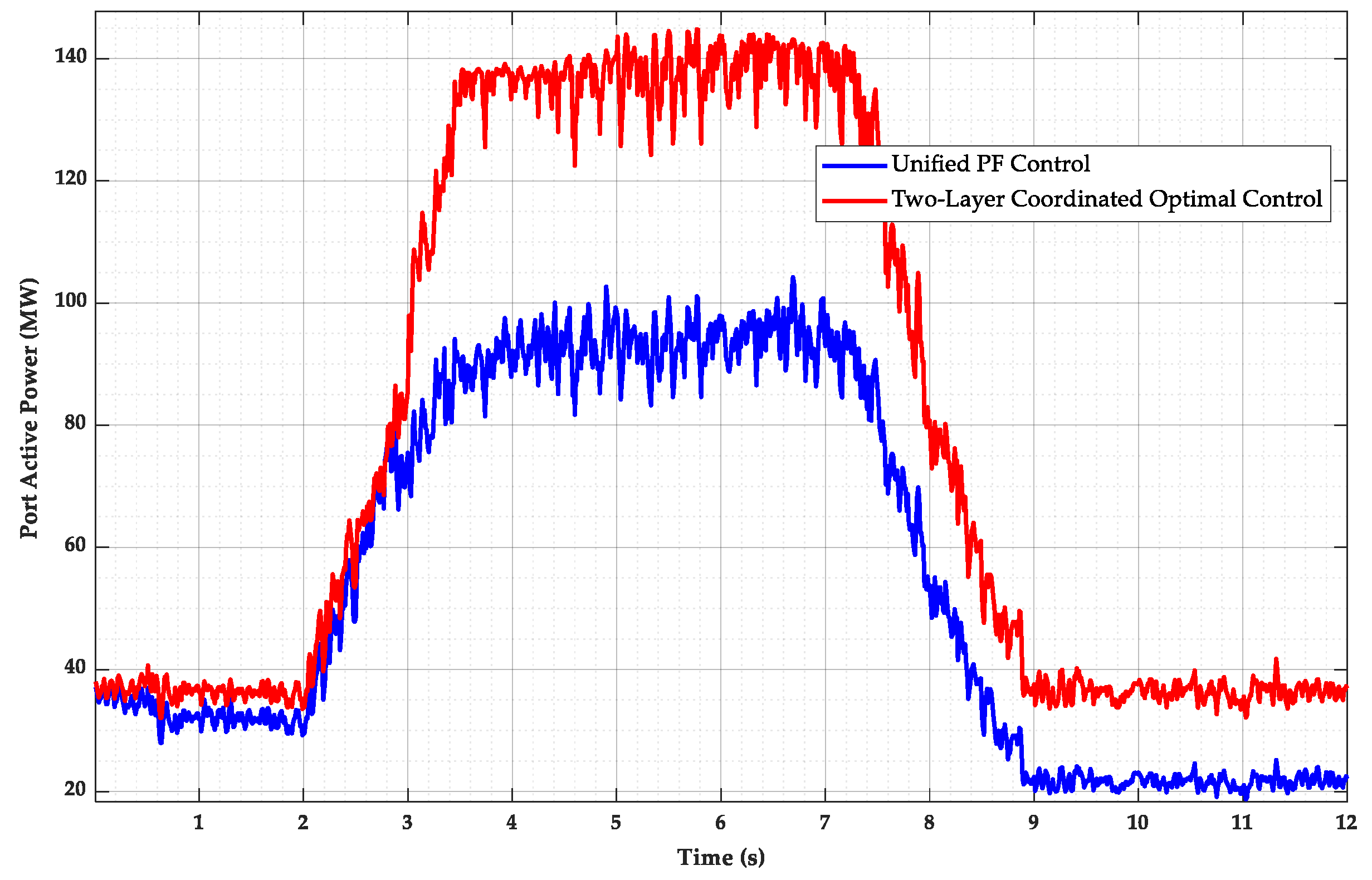

2.3. Global Voltage Two Layer Optimization Method Based on Second-Order Cone Optimization

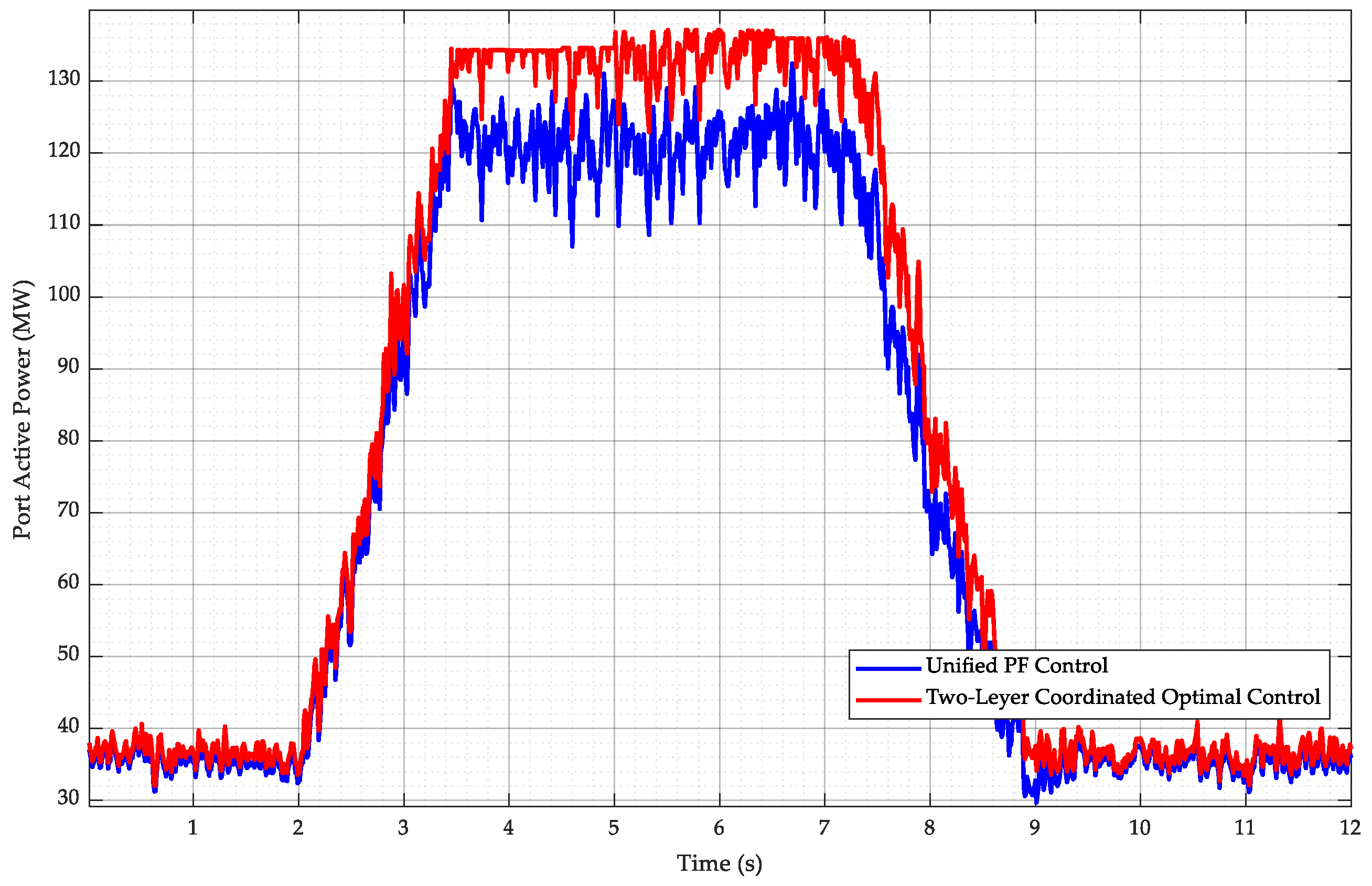

Both the voltage at the point of common coupling (PCC) and the terminal voltages of the wind turbine units within the wind farm belong to the 35 kV intra-farm voltage network. Therefore, the power flow within the farm can be optimized. The aim is to obtain the optimal distribution of active and reactive power output from the wind turbine units while ensuring intra-farm voltage security. The optimization objective is to maximize the active power output at the wind farm’s export point and the reactive power margin of the compensation devices, after accounting for the active power losses on the intra-farm collector lines. The objective function is formulated as follows:

Among them, Pout represents the active power output at the wind farm’s export point, QSVG denotes the reactive power output of the SVG, and w1 and w2 represent the weighting coefficients, respectively. The weights were selected based on the operational priority: maximizing active power export (Pout) is the primary goal, followed by preserving the SVG reactive margin (|QSVG|). Therefore, we selected w1 to be significantly larger than w2.

The constraints for the global optimization include branch power flow constraints based on the linearized DistFlow model, branch current constraints, voltage constraints at the sending and receiving ends of branches, branch power constraints accounting for losses and power distribution, node power constraints, maximum rotor current constraints for doubly fed induction generators (DFIGs), upper and lower limits for active and reactive power output, node voltage security region constraints, and point of common coupling voltage constraints. These can be expressed as follows:

Here, Ui and Uj represent the voltages at nodes i and j, respectively. rij and xij denote the resistance and reactance of the branch between nodes i and j. Iij, Pij, and Qij represent the current, active power, and reactive power flowing through the branch between nodes i and j. pj and qj represent the active and reactive power injected at node j, respectively. Pi,ref, Qi,ref, and QSVG,ref denote the active power reference value of the wind turbine to be optimized, the reactive power reference value of the wind turbine, and the reactive power reference value of the SVG, respectively. Pi,mppt represents the maximum power point tracking reference value for the active power of wind turbine ii derived from the MPPT algorithm. Qi,min and Qi,max denote the lower and upper limits of reactive power under the current active power output, respectively. Vmin and Vmax represent the lower and upper safety limits of the PCC voltage, respectively. SSVG denotes the reactive power capacity of the SVG. Pjk and Qjk represent the active power and reactive power on the branches connected to node j, respectively.

The reactive power limits on the machine side of a doubly fed induction generator (DFIG) are directly influenced by the current constraints of the stator and rotor windings, as well as the rotor-side converter. Here, the reactive power regulation capability on the grid side of the wind turbine is treated as a reactive power reserve, while only the machine-side reactive power is considered as the optimization target. The upper and lower limits of the reactive power on the machine side of the wind turbine are as follows:

Here, Us denotes the stator voltage of the wind turbine, Xs and Xm represent the stator reactance and magnetizing reactance of the wind turbine, respectively, and Irmax denotes the maximum rotor current limit of the wind turbine. Umin and Umax represent the lower and upper safety limits of the node voltage, respectively, and Imax denotes the branch current limit.

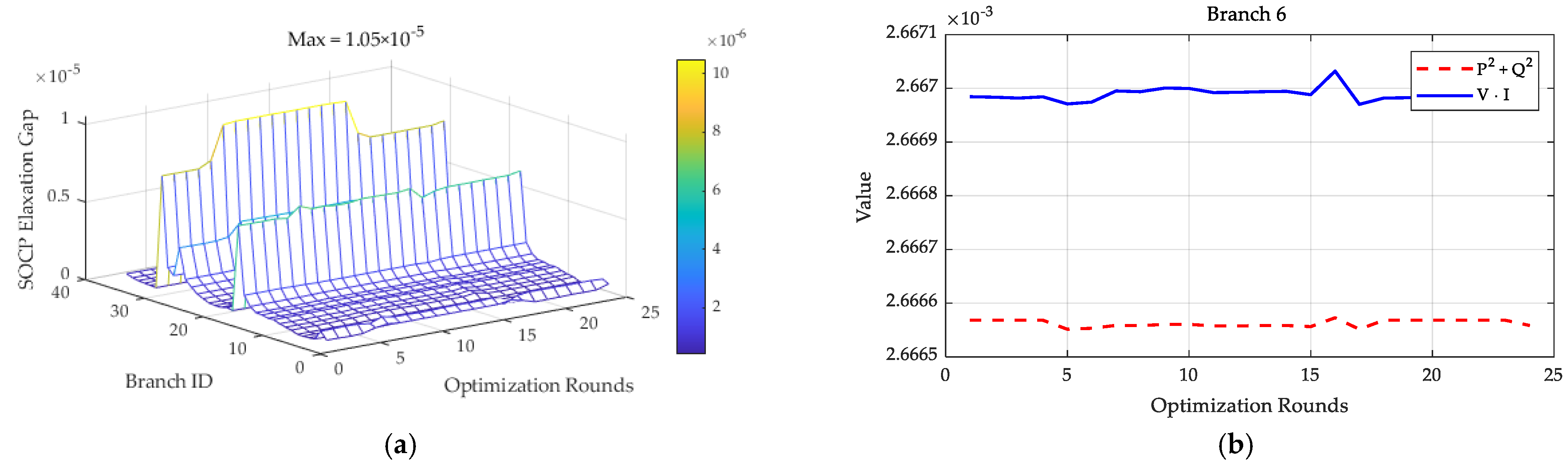

Since the power flow constraints and the upper and lower limits of the machine-side reactive power in the constraints are non-convex nonlinear constraints, they can only be solved using intelligent algorithms. However, intelligent algorithms suffer from issues such as low computational efficiency, high computational resource consumption, and susceptibility to local optima. Therefore, it is necessary to relax these nonlinear constraints to obtain second-order cone constraints that are easier for solvers to handle. The convex relaxation process via second-order cone programming is as follows: First, appropriate transformations are applied to the variables and constraints, aiming to convert the non-convex power flow equality equations into convex forms for optimized solving. During this transformation, variables or corresponding constraints can be relaxed, converting the optimization model into a convex optimization problem, thereby enabling the solution of the global optimum. Although this relaxation method expands the feasible region of the constraints, under exact relaxation conditions, the optimal solution of the original problem can be obtained at the boundary of the original feasible region.

Initially, squared variables are introduced to replace constraints involving quadratic terms, such as branch currents and node voltages, as shown in the following equations:

Perform second-order cone relaxation on the nonlinear and non-convex power flow constraints; transform the maximum rotor current constraint for doubly fed induction generators into an active-reactive power output circle constraint, apply second-order cone relaxation to it, and incorporate the resulting convex second-order cone constraints into the wind farm optimization model. This can be expressed as:

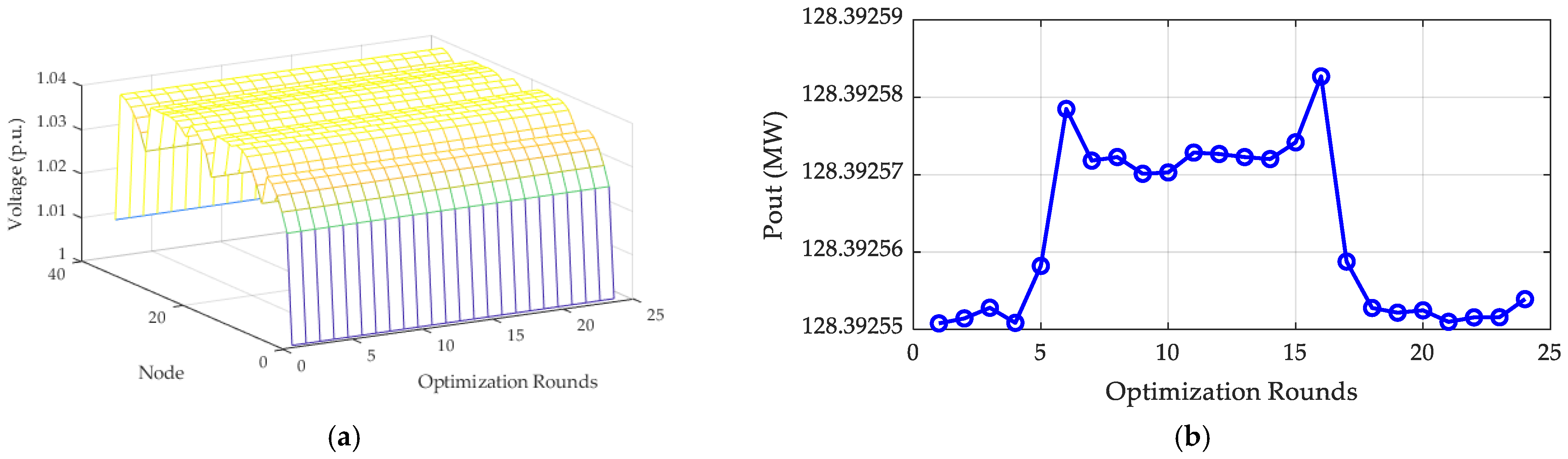

At this point, the non-convex and nonlinear constraints are transformed into a rotated second-order cone form. Research indicates that second-order cone relaxation is always tight under radial distribution network structures. Therefore, the optimal active and reactive power output of wind turbine units, as well as the corresponding terminal voltages and intra-farm power flow distribution, can be obtained by solving the optimization problem using commercial solvers. However, due to the different voltage levels between the impedance of the long-distance transmission line Z0 = R0 + jX0 (connecting the infinite grid and the PCC) and the intra-farm collector line impedance Z1 = R1 + jX1, which does not conform to the distribution network scenario, directly using a solver would result in an excessively large relaxation gap in the second-order cone relaxation, leading to solution failure.

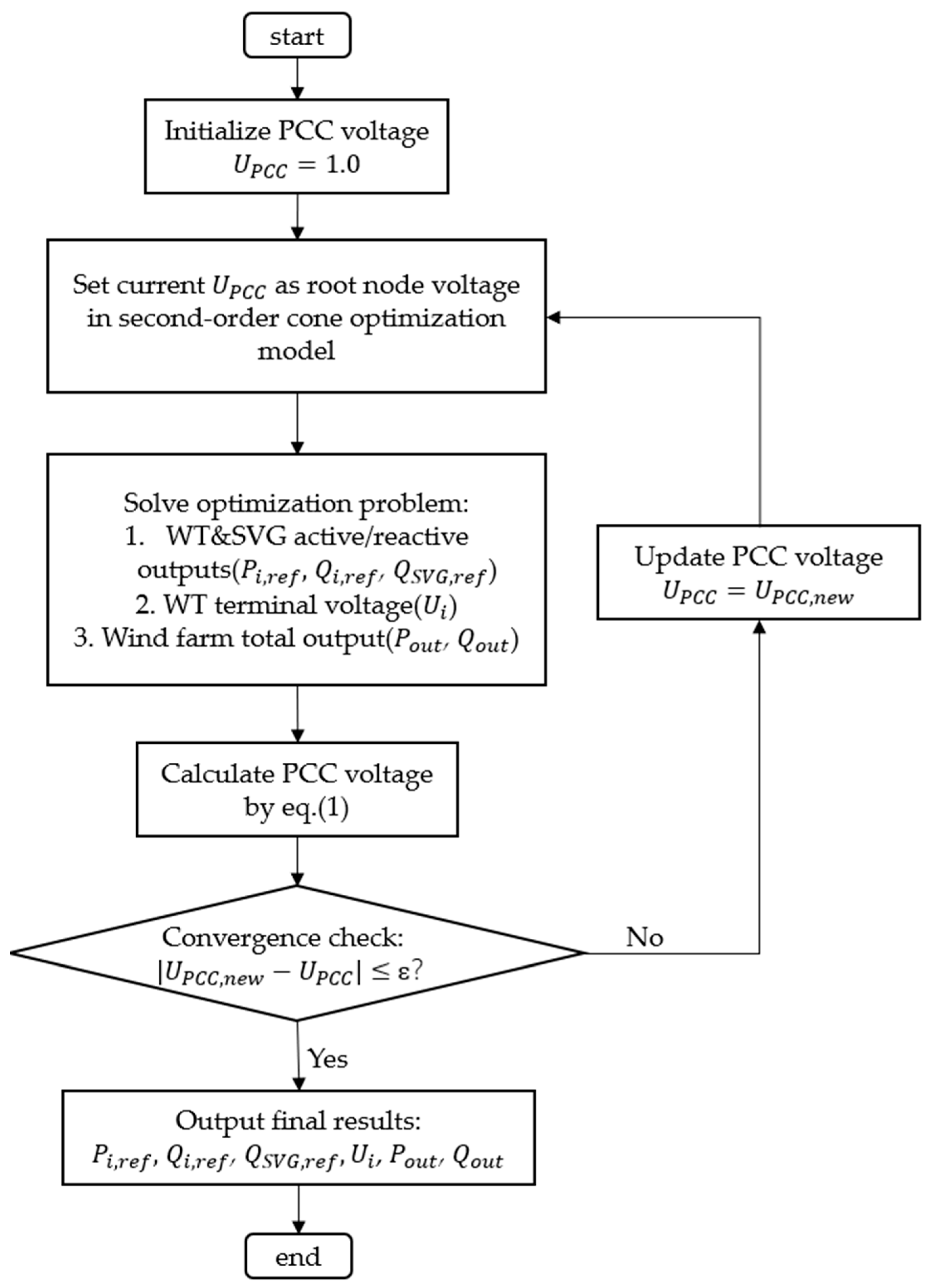

Therefore, this paper proposes a two-layer optimization. First, the per-unit PCC voltage is initialized to 1 and set as the root node voltage in the wind farm’s second-order cone optimization model to solve for the optimal active/reactive power output of the wind turbines and the corresponding terminal voltages. This yields the active power output P

out and reactive power output Q

out at the wind farm’s export point. These values are then substituted back into Equation (1) to calculate the PCC voltage U

PCC. This updated PCC voltage is iteratively fed back into the second-order cone optimization model until the difference between the PCC voltages from two consecutive iterations falls below the allowable error, at which point the iteration terminates. The iterative process is shown in

Figure 2.

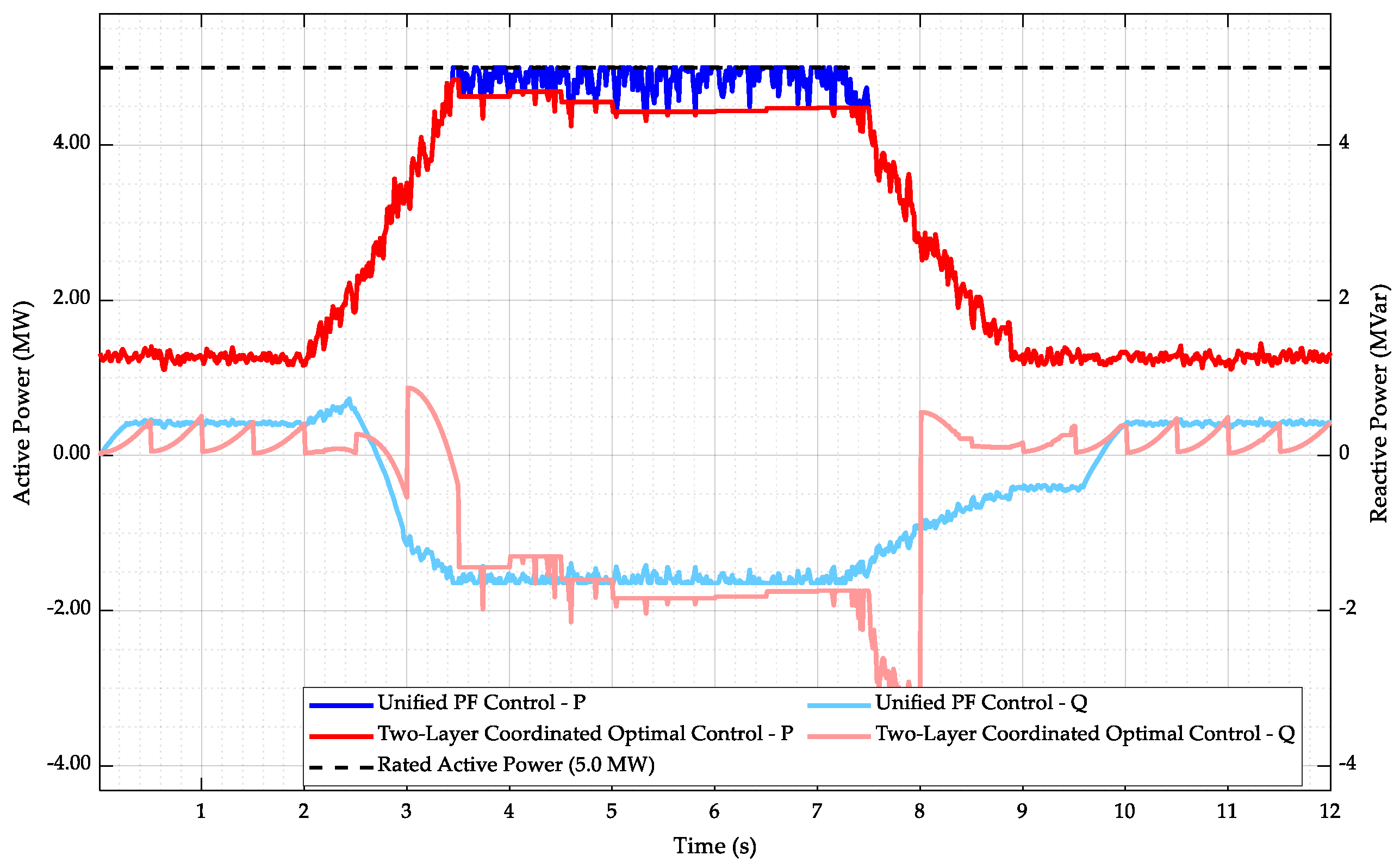

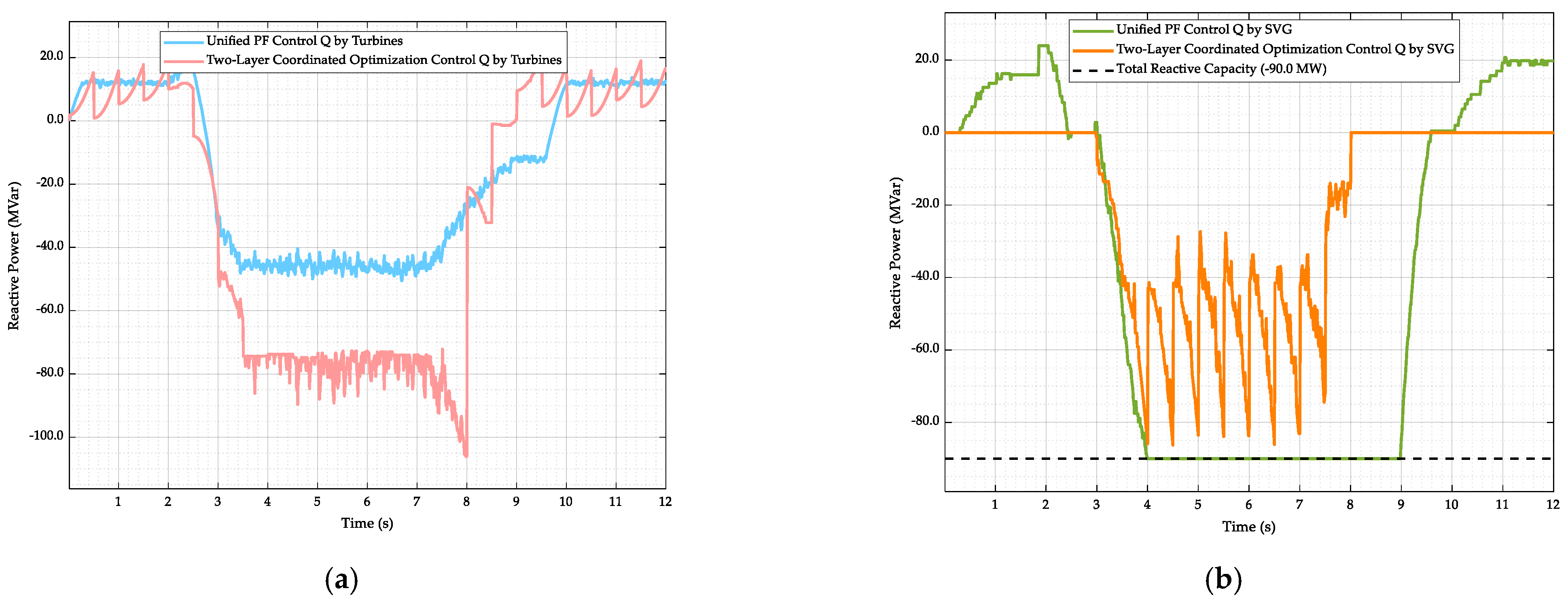

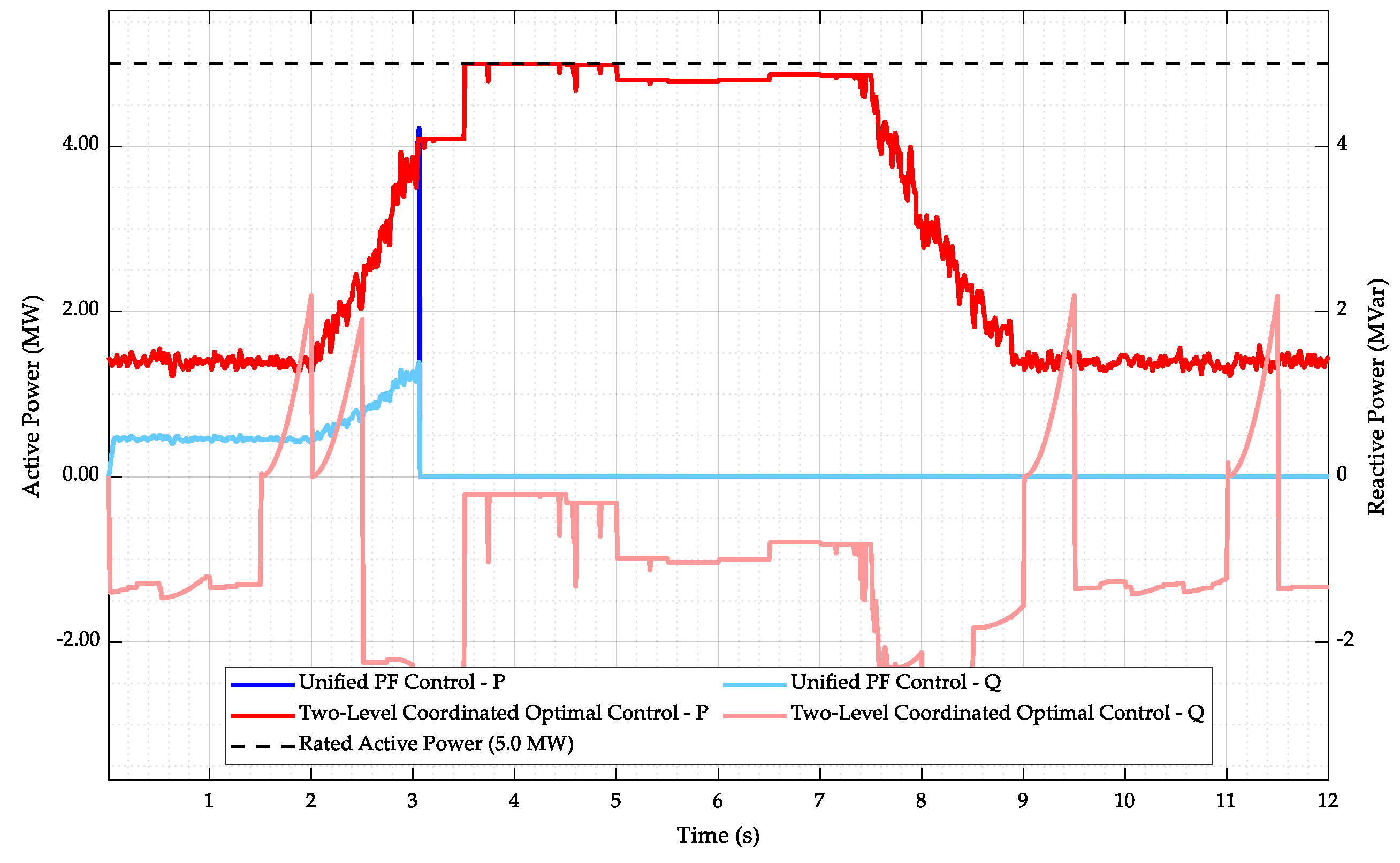

2.4. Wind Farm Reactive Power Demand Setting

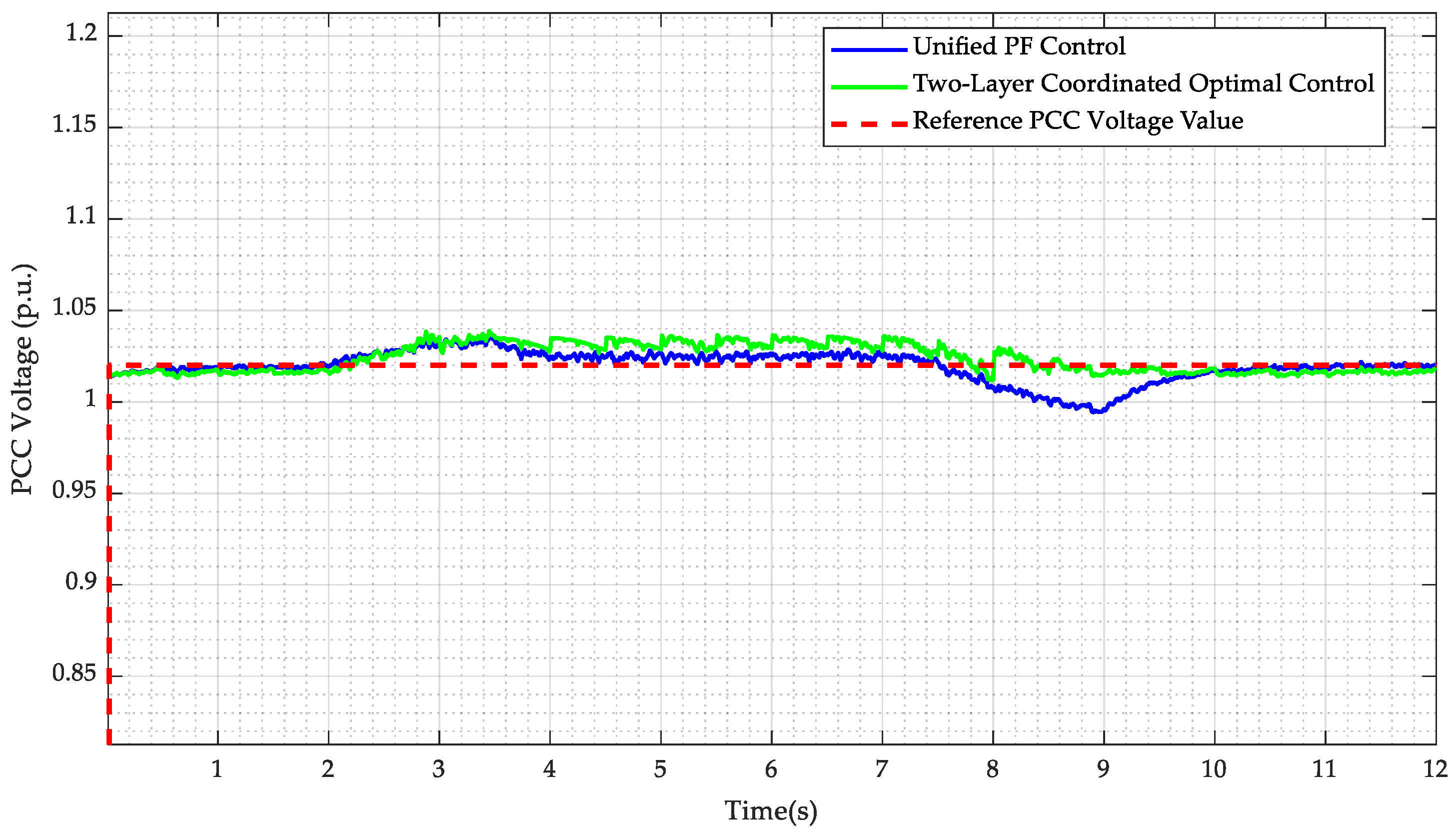

Reactive power and voltage control for the wind farm adopts a hierarchical control structure, primarily consisting of two layers: the global optimization layer and the voltage control layer. Considering the computation time required for global optimization and the fact that the time constant for adjusting the reactive power output of wind turbine units is larger than that of the SVG, the action time of the global optimization layer for wind turbines is on the order of seconds. Based on the current wind speed, this layer optimally solves for the best active and reactive power output, which is then allocated to the wind turbines and reactive power compensation devices within the farm to ensure that the terminal voltages remain within the safe range.

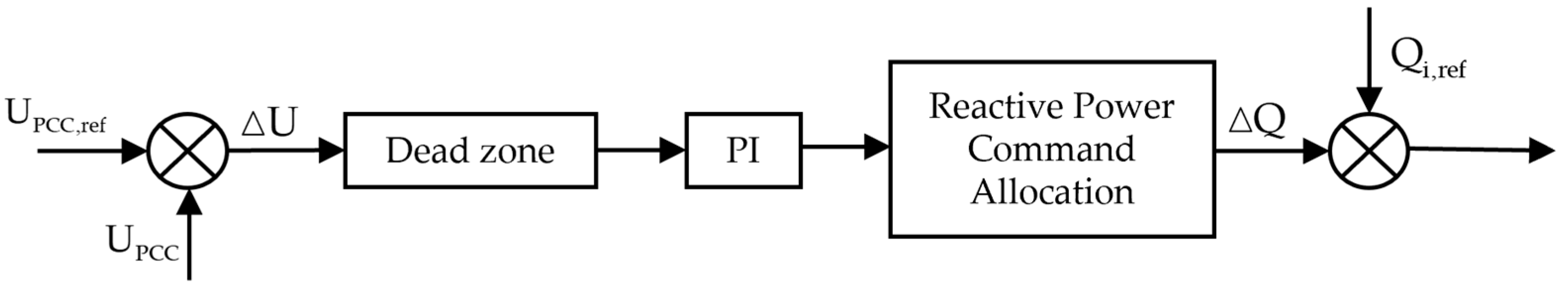

The voltage control layer operates on a millisecond timescale. The reactive power command generation process is shown in

Figure 3. It maintains the PCC voltage at the command value from the upper-layer AVC system through PI control with a fixed voltage at the point of common coupling (PCC) when wind speed fluctuates. Within each global control cycle, the active power output of the wind turbines tracks the wind speed via the MPPT algorithm. For wind turbines that have already utilized their full reactive output capability, the active power command value set by the global optimization layer is used as the upper limit for active power output to prevent exceeding the maximum rotor current constraint during this control cycle.

Regarding the reactive power command calculated through PI control, it is first evenly distributed to each wind turbine unit. Within the limit of not exceeding the rotor current constraint, the upper limit of reactive power output is determined. The difference between the total reactive power demand and the additional reactive power generated by the turbines is treated as an additional reactive power command for the SVG. This reactive command is superimposed on the SVG command value from each global optimization cycle, which serves as a feedforward signal, and the combined total reactive command is then issued to the SVG.