Dynamic CO2 Emission Differences Between E10 and E85 Fuels Based on Speed–Acceleration Mapping

Abstract

1. Introduction

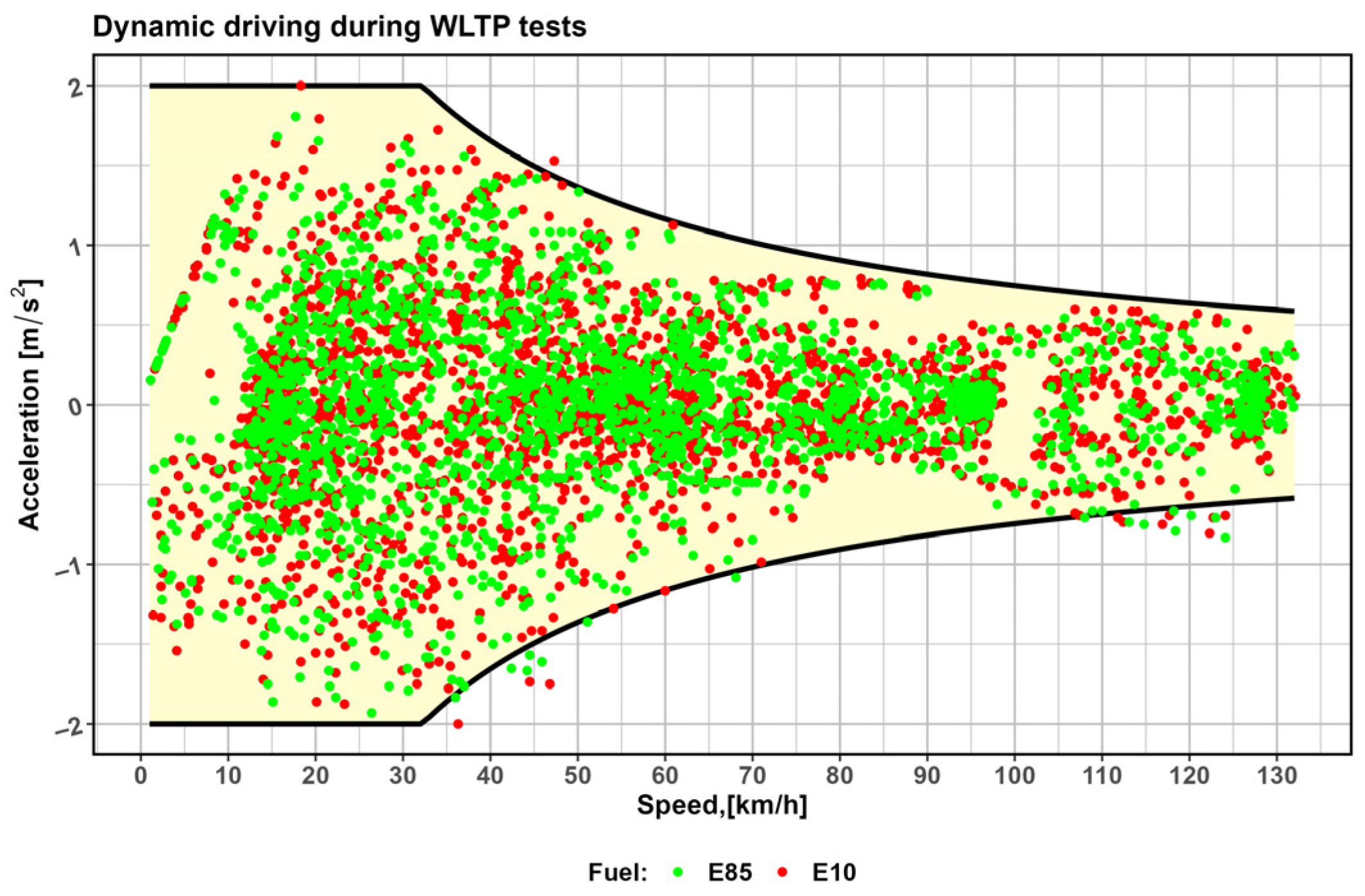

- developing a CO2 emission model dependent on vehicle speed and acceleration,

- identifying driving zones where CO2 emissions are higher with E85,

- determining differences in emissions resulting from the driving dynamics of vehicles fueled with E10 and E85.

2. Literature Review

3. Materials and Methods

4. Analysis of Emission During Tests

5. Results

6. Discussion

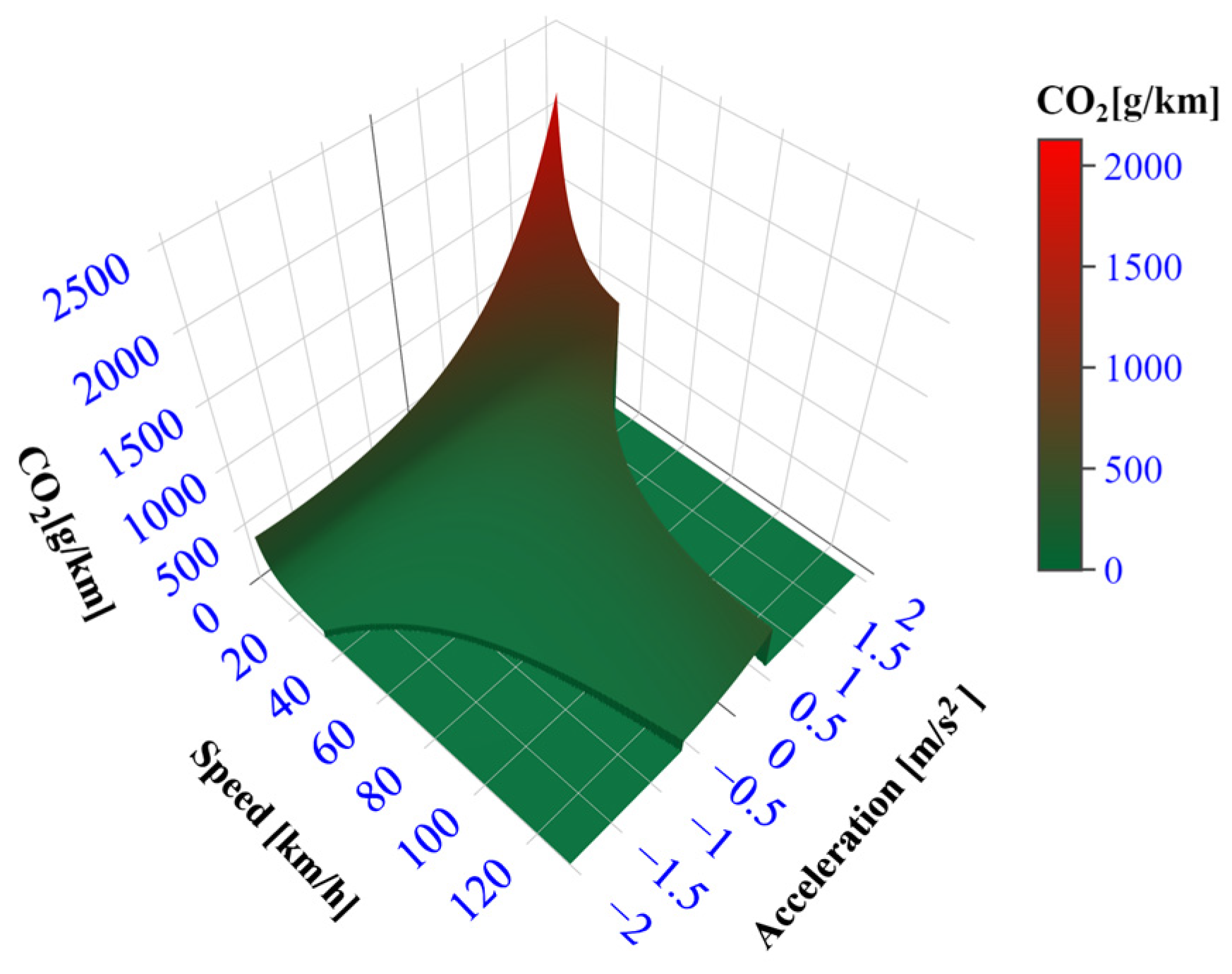

- They show that an identical trajectory (i.e., the same speed and acceleration curve) can generate different CO2 emissions depending on the fuel type used,

- They indicate that the most significant differences between E10 and E85 are concentrated in the regions (v, a) corresponding to high acceleration and increased engine load.

- In the speed-acceleration region, instantaneous CO2 emissions are lower for E85 than for E10 (due to the different elemental composition of ethanol, including its nominally higher H/C ratio but lower effective energy density resulting from the presence of oxygen in the molecule, which reduces the useful energy available during combustion).

- However, in higher load zones, these benefits are weakened or reversed due to the need to supply a larger fuel dose.

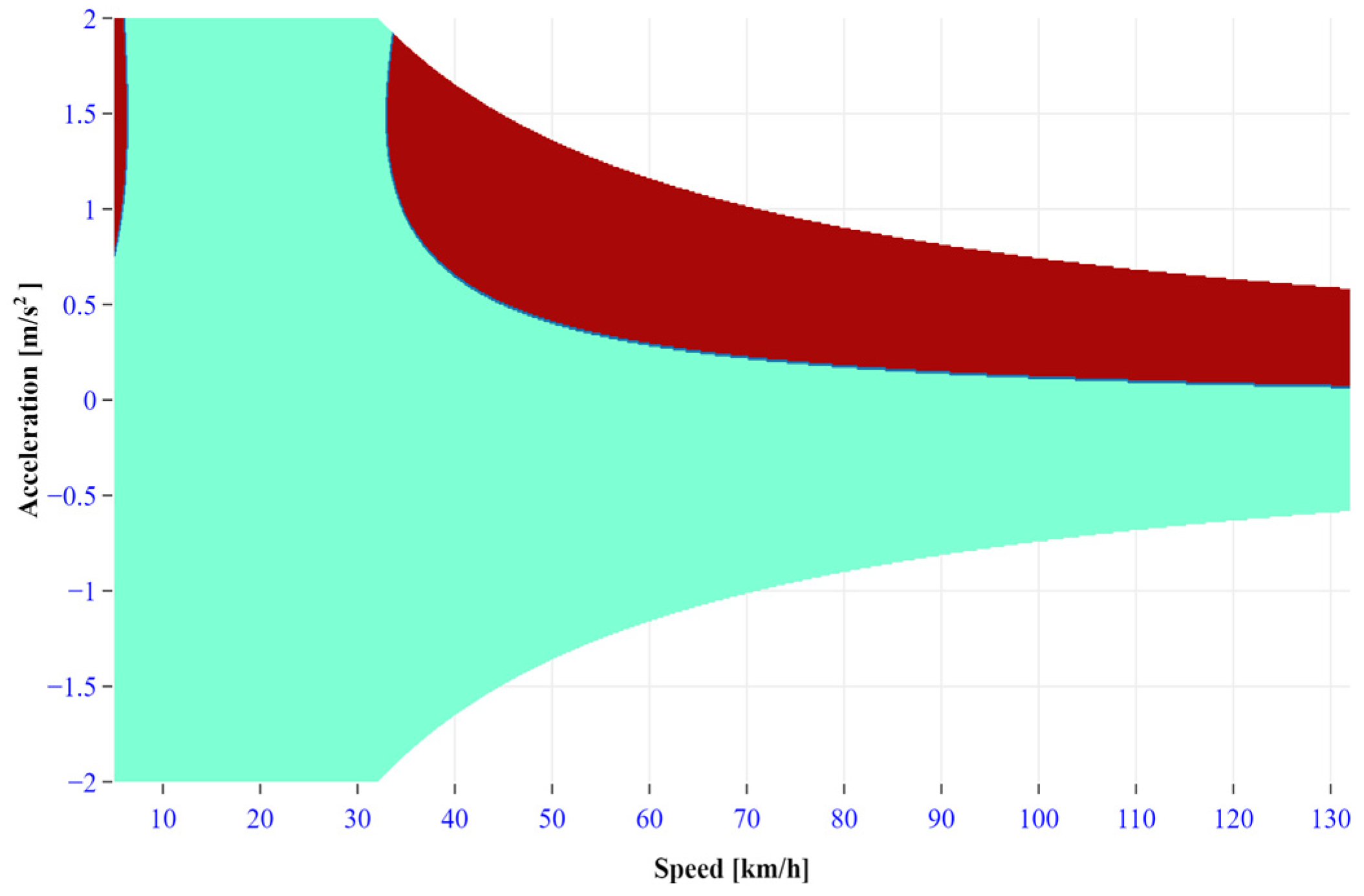

- CO2 emission maps clearly identify areas of the most significant emission increase during positive accelerations.

- Differences between E10 and E85 are primarily visible in these areas.

- However, during steady-state driving and during low accelerations, the impact of fuel type on instantaneous CO2 emissions is significantly smaller.

- At the tailpipe emission level, as the differences between E10 and E85 are limited and dependent on the load structure.

- At the life cycle level, where E85 may be a more climate-favourable fuel, provided appropriate raw materials and production technology are used [79].

7. Conclusions

- The study proposes a speed–acceleration-based framework for comparing instantaneous CO2 emissions between fuels, moving beyond conventional cycle-averaged indicators.

- Emission surfaces and a differential index were used to identify localised regions in the operating state space where fuel-dependent differences occur, rather than assuming uniform emission shifts.

- The results demonstrate that E85 does not lead to a consistent reduction in instantaneous CO2 emissions across the entire WLTP cycle, but alters the emission structure depending on vehicle load and acceleration.

- The most significant differences between E10 and E85 were observed in regions associated with high positive acceleration and increased engine load, where E85 tended to exhibit higher instantaneous CO2 emissions.

- Under steady-state and low-acceleration conditions, the differences in instantaneous CO2 emissions between the two fuels were limited.

- The proposed approach provides a transparent and interpretable alternative to more complex emission models, with potential applicability in fleet, regulatory, and traffic emission assessments.

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AFR | Air–Fuel Ratio |

| AI | Artificial Intelligence |

| BECCS | Bioenergy with Carbon Capture and Storage |

| CCS | Carbon Capture and Storage |

| COPERT | COmputer Programme to calculate Emissions from Road Transport |

| E10 | Gasoline with 10% ethanol |

| E85 | Ethanol fuel blend containing 85% ethanol and 15% gasoline |

| FFV | Flex-Fuel Vehicle |

| GHG | Greenhouse Gases |

| IoT | Internet of Things |

| LCA | Life Cycle Assessment |

| LSTM | Long Short-Term Memory |

| MLP | Multilayer Perceptron |

| NEDC | New European Driving Cycle |

| OBD | On-Board Diagnostics |

| PEMS | Portable Emissions Measurement System |

| RDE | Real Driving Emissions |

| SHAP | SHapley Additive exPlanations |

| SI engine | Spark-Ignition engine |

| VSP | Vehicle Specific Power |

| WLTC | Worldwide Harmonized Light-Duty Test Cycle |

| WLTP | Worldwide Harmonized Light Vehicles Test Procedure |

References

- Tibaquirá, J.; Huertas, J.; Ospina, S.; Quirama, L.; Niño, J. The Effect of Using Ethanol-Gasoline Blends on the Mechanical, Energy and Environmental Performance of In-Use Vehicles. Energies 2018, 11, 221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Myung, C.-L.; Choi, K.; Cho, J.; Kim, K.; Baek, S.; Lim, Y.; Park, S. Evaluation of Regulated, Particulate, and BTEX Emissions Inventories from a Gasoline Direct Injection Passenger Car with Various Ethanol Blended Fuels under Urban and Rural Driving Cycles in Korea. Fuel 2020, 262, 116406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frutuoso, F.S.; Alves, C.M.A.C.; Araújo, S.L.; Serra, D.S.; Barros, A.L.B.P.; Cavalcante, F.S.Á.; Araújo, R.S.; Policarpo, N.A.; Oliveira, M.L.M. Assessing Light Flex-Fuel Vehicle Emissions with Ethanol/Gasoline Blends along an Urban Corridor: A Case of Fortaleza/Brazil. Int. J. Transp. Sci. Technol. 2023, 12, 447–459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Warguła, Ł.; Wieczorek, B.; Gierz, Ł.; Karwat, B. Critical Concerns Regarding the Transition from E5 to E10 Gasoline in the European Union, Particularly in Poland in 2024—A Theoretical and Experimental Analysis of the Problem of Controlling the Air–Fuel Mixture Composition (AFR) and the λ Coefficient. Energies 2025, 18, 852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Novakovic, M.; Tuner, M.; Garcia, A.; Verhelst, S. An Experimental Investigation of Directly Injected E85 Fuel in a Heavy-Duty Compression Ignition Engine. In Proceedings of the SAE Powertrains, Fuels & Lubricants Conference & Exhibition, Krakow, Poland, 6–8 September 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Gupta, S.; Kanchan, S.; Kaur, R.; Sandhu, S.S. Investigation of Performance and Emission Characteristics Using Ethanol-Blended Gasoline Fuel as a Flex-Fuel in Two-Wheeler Vehicle Mounted on a Chassis Dynamometer. Clean. Energy 2024, 8, 174–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rimkus, A.; Pukalskas, S.; Mejeras, G.; Nagurnas, S. Impact of Bioethanol Concentration in Gasoline on SI Engine Sustainability. Sustainability 2024, 16, 2397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mateo, N.E.R.; Calderon, A.; Agrupis, S.; Manzano, L.F.T.; Baga, C.C.; Fagaragan, A. Nipa-Based Bioethanol as a Renewable Pure Engine Fuel: A Preliminary Performance Testing and Carbon Footprint Quantification. Int. J. Renew. Energy Dev. 2025, 14, 39–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daylan, B.; Ciliz, N. Life Cycle Assessment and Environmental Life Cycle Costing Analysis of Lignocellulosic Bioethanol as an Alternative Transportation Fuel. Renew. Energy 2016, 89, 578–587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghani, H.U.; Gheewala, S.H. Environmental Sustainability Assessment of Molasses-Based Bioethanol Fuel in Pakistan. Sustain. Prod. Consum. 2021, 27, 402–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Policarpo, N.A.; Frutuoso, F.S.; Cassiano, D.R.; Cavalcante, F.S.A.; Araújo, R.S.; Bertoncini, B.V.; Oliveira, M.L.M. Emission Estimates for an On-Road Flex-Fuel Vehicles Operated by Ethanol-Gasoline Blends in an Urban Region, Brazil. Urban. Clim. 2018, 24, 111–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Songkitti, W.; Aroonsrisopon, T.; Wirojsakunchai, E. An Analysis of Emissions from An Ethanol Flex-Fuel Vehicle under Two Distinct Driving Cycle Tests during Cold Start. Int. J. Automot. Mech. Eng. 2022, 19, 9551–9562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Salvo Junior, O.; Silva Forcetto, A.L.; Maria Laganá, A.A.; Vaz De Almeida, F.G.; Baptista, P. Combining On-Road Measurements and Life-Cycle Carbon Emissions of Flex-Fuel Vehicle. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2024, 204, 114784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos, A.S.; Gilio, L.; Halmenschlager, V.; Diniz, T.B.; Almeida, A.N. Flexible-Fuel Automobiles and CO 2 Emissions in Brazil: Parametric and Semiparametric Analysis Using Panel Data. Habitat. Int. 2018, 71, 147–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pavlovic, J.; Ciuffo, B.; Fontaras, G.; Valverde, V.; Marotta, A. How Much Difference in Type-Approval CO2 Emissions from Passenger Cars in Europe Can Be Expected from Changing to the New Test Procedure (NEDC vs. WLTP)? Transp. Res. Part A Policy Pract. 2018, 111, 136–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chatzipanagi, A.; Pavlovic, J.; Ktistakis, M.A.; Komnos, D.; Fontaras, G. Evolution of European Light-Duty Vehicle CO2 Emissions Based on Recent Certification Datasets. Transp. Res. Part D Transp. Environ. 2022, 107, 103287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jaworski, A.; Mądziel, M.; Lew, K.; Campisi, T.; Woś, P.; Kuszewski, H.; Wojewoda, P.; Ustrzycki, A.; Balawender, K.; Jakubowski, M. Evaluation of the Effect of Chassis Dynamometer Load Setting on CO2 Emissions and Energy Demand of a Full Hybrid Vehicle. Energies 2021, 15, 122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fortune, J.-F.; Cologon, P.; Hayrault, P.; Heninger, M.; Leprovost, J.; Lemaire, J.; Anselmi, P.; Matrat, M. Impact of Fuel Ethanol Content on Regulated and Non-Regulated Emissions Monitored by Various Analytical Techniques over Flex-Fuel and Conversion Kit Applications. Fuel 2023, 334, 126669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Iorio, S.; Catapano, F.; Magno, A.; Sementa, P.; Vaglieco, B.M. The Potential of Ethanol/Methanol Blends as Renewable Fuels for DI SI Engines. Energies 2023, 16, 2791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laskowski, P.; Zimakowska-Laskowska, M. Simulation Study of the Effect of Ethanol Content in Fuel on Petrol Engine Performance and Exhaust Emissions. Combust. Engines 2025, 201, 129–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Triantafyllopoulos, G.; Dimaratos, A.; Ntziachristos, L.; Bernard, Y.; Dornoff, J.; Samaras, Z. A Study on the CO2 and NOx Emissions Performance of Euro 6 Diesel Vehicles under Various Chassis Dynamometer and On-Road Conditions Including Latest Regulatory Provisions. Sci. Total Environ. 2019, 666, 337–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Martinet, S.; Louis, C.; Pasquier, A.; Tassel, P.; Perret, P. Emission Characterization of In-Use Diesel and Gasoline Euro 4 to Euro 6 Passenger Cars Tested on Chassis Dynamometer Bench and Emission Model Assessment. Aerosol Air Qual. Res. 2017, 17, 2289–2299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zimakowska-Laskowska, M.; Kozłowski, E.; Laskowski, P.; Wiśniowski, P.; Świderski, A.; Orynycz, O. Vehicle Exhaust Emissions in the Light of Modern Research Tools: Synergy of Chassis Dynamometers and Computational Models. Combust. Engines 2025, 200, 145–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dimaratos, A.; Toumasatos, Z.; Doulgeris, S.; Triantafyllopoulos, G.; Kontses, A.; Samaras, Z. Assessment of CO2 and NOx Emissions of One Diesel and One Bi-Fuel Gasoline/CNG Euro 6 Vehicles During Real-World Driving and Laboratory Testing. Front. Mech. Eng. 2019, 5, 62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kozłowski, E.; Rimkus, A.; Zimakowska-Laskowska, M.; Matijošius, J.; Wiśniowski, P.; Traczyński, M.; Laskowski, P.; Madlenak, R. Energy and Environmental Impacts of Replacing Gasoline with LPG Under Real Driving Conditions. Energies 2025, 18, 5522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuranc, A.; Caban, J.; Šarkan, B.; Dudziak, A.; Stoma, M. Emission of Selected Exhaust Gas Components and Fuel Consumption in Different Driving Cycles. Komunikácie 2021, 23, B265–B277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mogno, C.; Fontaras, G.; Arcidiacono, V.; Komnos, D.; Pavlovic, J.; Ciuffo, B.; Makridis, M.; Valverde, V. The Application of the CO2MPAS Model for Vehicle CO2 Emissions Estimation over Real Traffic Conditions. Transp. Policy 2022, 124, 152–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orynycz, O.; Zimakowska-Laskowska, M.; Kulesza, E. CO2 Emission and Energy Consumption Estimates in the COPERT Model—Conclusions from Chassis Dynamometer Tests and SANN Artificial Neural Network Models and Their Meaning for Transport Management. Energies 2025, 18, 3457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Tong, Z.; Haroon, M. Estimation of Transport CO2 Emissions Using Machine Learning Algorithm. Transp. Res. Part. D Transp. Environ. 2024, 133, 104276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q.; Wei, N.; Mao, H. Impact of Ethanol-Gasoline Implementation on Vehicle Emission Based on Remote Sensing Test. Environ. Res. Commun. 2022, 4, 055008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, Y.; Xu, J.; Ni, J. Carbon Emission Model of Vehicles Driving at Fluctuating Speed on Highway. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2022, 30, 18064–18077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Suarez, J.; Makridis, M.; Anesiadou, A.; Komnos, D.; Ciuffo, B.; Fontaras, G. Benchmarking the Driver Acceleration Impact on Vehicle Energy Consumption and CO2 Emissions. Transp. Res. Part D Transp. Environ. 2022, 107, 103282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alam, G.M.I.; Arfin Tanim, S.; Sarker, S.K.; Watanobe, Y.; Islam, R.; Mridha, M.F.; Nur, K. Deep Learning Model Based Prediction of Vehicle CO2 Emissions with eXplainable AI Integration for Sustainable Environment. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 3655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khajavi, H.; Rastgoo, A. Predicting the Carbon Dioxide Emission Caused by Road Transport Using a Random Forest (RF) Model Combined by Meta-Heuristic Algorithms. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2023, 93, 104503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhaparova, S.; Kulisz, M.; Kospanov, N.; Ibrayeva, A.; Bayazitova, Z.; Kurmanbayeva, A. Modeling Air Pollution from Urban Transport and Strategies for Transitioning to Eco-Friendly Mobility in Urban Environments. Environments 2025, 12, 411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le Cornec, C.M.A.; Molden, N.; Van Reeuwijk, M.; Stettler, M.E.J. Modelling of Instantaneous Emissions from Diesel Vehicles with a Special Focus on NOx: Insights from Machine Learning Techniques. Sci. Total Environ. 2020, 737, 139625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Lin, C.; Zhao, B.; Gong, B.; Liu, H. Trajectory-Based Vehicle Emission Evaluation for Signalized Intersection Using Roadside LiDAR Data. J. Clean. Prod. 2024, 440, 140971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhai, Z.; Tu, R.; Xu, J.; Wang, A.; Hatzopoulou, M. Capturing the Variability in Instantaneous Vehicle Emissions Based on Field Test Data. Atmosphere 2020, 11, 765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mądziel, M. Instantaneous CO2 Emission Modelling for a Euro 6 Start-Stop Vehicle Based on Portable Emission Measurement System Data and Artificial Intelligence Methods. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2023, 31, 6944–6959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jang, S.; Song, K.-H.; Kim, D.; Ko, J.; Lee, S.M.; Elkosantini, S.; Suh, W. Road-Section-Based Analysis of Vehicle Emissions and Energy Consumption. Sustainability 2023, 15, 4421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhong, H.; Chen, K.; Liu, C.; Zhu, M.; Ke, R. Models for Predicting Vehicle Emissions: A Comprehensive Review. Sci. Total Environ. 2024, 923, 171324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, F.; Zhu, J.; Yang, H.; He, X.; Peng, Q. Data-Driven Symmetry and Asymmetry Investigation of Vehicle Emissions Using Machine Learning: A Case Study in Spain. Symmetry 2025, 17, 1223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramirez-Sanchez, E.; Tang, C.; Xu, Y.; Renganathan, N.; Jayawardana, V.; He, Z.; Wu, C. NeuralMOVES: A Lightweight and Microscopic Vehicle Emission Estimation Model Based on Reverse Engineering and Surrogate Learning. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2502.04417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, O.; Ramadan, I.; Shawky, M. Modelling Vehicle Emissions and Fuel Consumption Based on Instantaneous Speed and Acceleration Levels. Eng. Res. J. Fac. Eng. 2022, 51, 106–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Volintiru, O.N.; Mărășescu, D.; Coșofreț, D.; Popa, A. Aspects Regarding the CO2 Footprint Developed by Marine Diesel Engines. Fire 2025, 8, 240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohassab, H.; Abouelsoud, M.; Shmroukh, A.N.; Ghazaly, N.M. Experimental Investigation of Performance, Combustion Efficiency and Emissions of SI Engine for Several Octane Numbers. J. Adv. Res. Fluid. Mech. Therm. Sc. 2025, 127, 81–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Dai, H.; Feng, H.; Guo, M.; Zylianov, V.; Feng, Z.; Cui, J. Carbon Emission of Urban Vehicles Based on Carbon Emission Factor Correlation Analysis. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 2037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Longo, K.; Wang, X.; Zhao, H. Impact of Diesel-Hythane Dual-Fuel Combustion on Engine Performance and Emissions in a Heavy-Duty Engine at Low-Load Condition. Int. J. Engine Res. 2024, 25, 276–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Zhang, J.; Zhang, Z.; Zhang, B.; Hu, J.; Zhong, W.; Ye, Y. Effect of Ammonia Energy Ratio and Load on Combustion and Emissions of an Ammonia/Diesel Dual-Fuel Engine. Energy 2024, 302, 131860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chojnowski, J.; Karczewski, M.; Szamrej, G.A. Dual-Fuel Engines Using Hydrogen-Enriched Fuels as an Ecological Source of Energy for Transport, Industry and Power Engineering. Combust. Engines 2024, 198, 3–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rimkus, A.; Kozłowski, E.; Vipartas, T.; Pukalskas, S.; Wiśniowski, P.; Matijošius, J. Emission Characteristics of Hydrogen-Enriched Gasoline Under Dynamic Driving Conditions. Energies 2025, 18, 1190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Subramanian, T.; Varuvel, E.G.; Leenus, J.M.; Beddhannan, N. Effect of Electrochemical Conversion of Biofuels Using Ionization System on CO2 Emission Mitigation in CI Engine along with Post-Combustion System. Fuel Process. Technol. 2018, 173, 21–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wasilewski, J.; Szyszlak-Bargłowicz, J.; Zając, G.; Szczepanik, M. Assessment of Co2 Emission by Tractor Engine at Varied Control Settings of Fuel Unit. Agric. Eng. 2020, 24, 105–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dižo, J.; Blatnický, M.; Sága, M.; Šťastniak, P. A Numerical Study of a Compressed Air Engine with Rotating Cylinders. Appl. Sci. 2021, 11, 7504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cristofanelli, P.; Fratticioli, C.; Hazan, L.; Chariot, M.; Couret, C.; Gazetas, O.; Kubistin, D.; Laitinen, A.; Leskinen, A.; Laurila, T.; et al. Identification of Spikes in Continuous Ground-Based in Situ Time Series of CO2, CH4 and CO: An Extended Experiment within the European ICOS Atmosphere Network. Atmos. Meas. Tech. 2023, 16, 5977–5994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El Yazidi, A.; Ramonet, M.; Ciais, P.; Broquet, G.; Pison, I.; Abbaris, A.; Brunner, D.; Conil, S.; Delmotte, M.; Gheusi, F.; et al. Identification of Spikes Associated with Local Sources in Continuous Time Series of Atmospheric CO, CO2 and CH4. Atmos. Meas. Tech. 2018, 11, 1599–1614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryoo, J.-M.; Fung, I.; Ehleringer, J.R. Short-Term Energy and Meteorological Impacts on Thanksgiving CO2 in Salt Lake City. Environ. Res. Commun. 2025, 7, 065001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mądziel, M.; Jaworski, A.; Kuszewski, H.; Woś, P.; Campisi, T.; Lew, K. The Development of CO2 Instantaneous Emission Model of Full Hybrid Vehicle with the Use of Machine Learning Techniques. Energies 2021, 15, 142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajala, A.A.; Adeoye, O.L.; Salami, O.M.; Jimoh, A.Y. An Examination of Daily CO2 Emissions Prediction through a Comparative Analysis of Machine Learning, Deep Learning, and Statistical Models. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2025, 32, 2510–2535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Singh, M.; Dubey, R. Deep Learning Model Based CO2 Emissions Prediction Using Vehicle Telematics Sensors Data. IEEE Trans. Intell. Veh. 2023, 8, 768–777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Zhou, R.; Peng, S.; Mao, H.; Yang, Z.; Andre, M.; Zhang, X. Development of Vehicle Emission Model Based on Real-Road Test and Driving Conditions in Tianjin, China. Atmosphere 2022, 13, 595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosero, F.; Rosero, C.X.; Segovia, C. Towards Simpler Approaches for Assessing Fuel Efficiency and CO2 Emissions of Vehicle Engines in Real Traffic Conditions Using On-Board Diagnostic Data. Energies 2024, 17, 4814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fontaras, G.; Ciuffo, B.; Zacharof, N.; Tsiakmakis, S.; Marotta, A.; Pavlovic, J.; Anagnostopoulos, K. The Difference between Reported and Real-World CO2 Emissions: How Much Improvement Can Be Expected by WLTP Introduction? Transp. Res. Procedia 2017, 25, 3933–3943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasan Shahariar, G.M.; Sajjad, M.; Suara, K.A.; Jahirul, M.I.; Chu-Van, T.; Ristovski, Z.; Brown, R.J.; Bodisco, T.A. On-Road CO2 and NOx Emissions of a Diesel Vehicle in Urban Traffic. Transp. Res. Part D Transp. Environ. 2022, 107, 103326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qi, Z.; Gu, M.; Cao, J.; Zhang, Z.; You, C.; Zhan, Y.; Ma, Z.; Huang, W. The Effects of Varying Altitudes on the Rates of Emissions from Diesel and Gasoline Vehicles Using a Portable Emission Measurement System. Atmosphere 2023, 14, 1739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Z.; Wu, L.; Niu, H.; Jia, Z.; Qi, Z.; Liu, Y.; Zhang, Q.; Wang, T.; Peng, J.; Mao, H. Investigating the Impact of High-Altitude on Vehicle Carbon Emissions: A Comprehensive on-Road Driving Study. Sci. Total Environ. 2024, 918, 170671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García, A.; Monsalve-Serrano, J.; Martínez-Boggio, S.; Rückert Roso, V.; Duarte Souza Alvarenga Santos, N. Potential of Bio-Ethanol in Different Advanced Combustion Modes for Hybrid Passenger Vehicles. Renew. Energy 2020, 150, 58–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ogunkunle, O.; Ahmed, N.A. Overview of Biodiesel Combustion in Mitigating the Adverse Impacts of Engine Emissions on the Sustainable Human–Environment Scenario. Sustainability 2021, 13, 5465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeCicco, J.M.; Liu, D.Y.; Heo, J.; Krishnan, R.; Kurthen, A.; Wang, L. Carbon Balance Effects of U.S. Biofuel Production and Use. Clim. Change 2016, 138, 667–680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaspers, B.C.; Kuo, P.-C.; Amladi, A.; Van Neerbos, W.; Aravind, P.V. Negative CO2 Emissions for Transportation. Front. Energy Res. 2021, 9, 626538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiltink, T.; Ramirez Ramirez, A.; Pérez-Fortes, M. Trade-Offs in the Integration of Biogenic CO2-Based Supply Chains for Storage and Use in the Transport Sector. In Proceedings of the 17th Greenhouse Gas Control Technologies Conference (GHGT-17), Calgary, AB, Canada, 20–24 October 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christianides, D.; Bagaki, D.A.; Timmers, R.A.; Zrimec, M.B.; Theodoropoulou, A.; Angelidaki, I.; Kougias, P.; Zampieri, G.; Kamergi, N.; Napoli, A.; et al. Biogenic CO2 Emissions in the EU Biofuel and Bioenergy Sector: Mapping Sources, Regional Trends, and Pathways for Capture and Utilisation. Energies 2025, 18, 1345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Labib, S.M.; Neema, M.N.; Rahaman, Z.; Patwary, S.H.; Shakil, S.H. Carbon Dioxide Emission and Bio-Capacity Indexing for Transportation Activities: A Methodological Development in Determining the Sustainability of Vehicular Transportation Systems. J. Environ. Manag. 2018, 223, 57–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bezyk, Y.; Sówka, I.; Górka, M. Assessment of Urban CO2 Budget: Anthropogenic and Biogenic Inputs. Urban. Clim. 2021, 39, 100949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.; Berelson, W.M.; Rollins, N.E.; Asimow, N.G.; Newman, C.; Cohen, R.C.; Miller, J.B.; McDonald, B.C.; Peischl, J.; Lehman, S.J. Observing Anthropogenic and Biogenic CO2 Emissions in Los Angeles Using a Dense Sensor Network. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2025, 59, 3508–3517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dees, J.; Oke, K.; Goldstein, H.; McCoy, S.T.; Sanchez, D.L.; Simon, A.J.; Li, W. Cost and Life Cycle Emissions of Ethanol Produced with an Oxyfuel Boiler and Carbon Capture and Storage. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2023, 57, 5391–5403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brandão, M.; Heijungs, R.; Cowie, A.L. On Quantifying Sources of Uncertainty in the Carbon Footprint of Biofuels: Crop/Feedstock, LCA Modelling Approach, Land-Use Change, and GHG Metrics. Biofuel Res. J. 2022, 9, 1608–1616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soleymani Angili, T.; Grzesik, K.; Rödl, A.; Kaltschmitt, M. Life Cycle Assessment of Bioethanol Production: A Review of Feedstock, Technology and Methodology. Energies 2021, 14, 2939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Umesh; Moholkar, V.S. 2G Bioethanol for Sustainable Transport Sector: Review and Analysis of the Life Cycle Assessments. Curr. Pollut. Rep. 2025, 11, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osman, A.I.; Chen, L.; Yang, M.; Msigwa, G.; Farghali, M.; Fawzy, S.; Rooney, D.W.; Yap, P.-S. Cost, Environmental Impact, and Resilience of Renewable Energy under a Changing Climate: A Review. Environ. Chem. Lett. 2023, 21, 741–764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahman, A.; Murad, S.M.W.; Mohsin, A.K.M.; Wang, X. Does Renewable Energy Proactively Contribute to Mitigating Carbon Emissions in Major Fossil Fuels Consuming Countries? J. Clean. Prod. 2024, 452, 142113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Mae, M.; Nishimura, S.; Matsuhashi, R. Vehicular Fuel Consumption and CO2 Emission Estimation Model Integrating Novel Driving Behavior Data Using Machine Learning. Energies 2024, 17, 1410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seo, J.; Park, S. Optimizing Model Parameters of Artificial Neural Networks to Predict Vehicle Emissions. Atmos. Environ. 2023, 294, 119508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, T.; McCaffery, C.; Ma, T.; Hao, P.; Durbin, T.D.; Johnson, K.C.; Karavalakis, G. Expanding the Ethanol Blend Wall in California: Emissions Comparison between E10 and E15. Fuel 2023, 350, 128836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kozak, M.; Waligórski, M.; Wcisło, G.; Wierzbicki, S.; Duda, K. Exhaust Emissions from a Direct Injection Spark-Ignition Engine Fueled with High-Ethanol Gasoline. Energies 2025, 18, 454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hunicz, J. Modelowanie Silników Spalinowych (Modeling of Internal Combustion Engines); Lublin University of Technology Publishing House: Lublin, Poland, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Hastie, T.; Tibshirani, R.; Friedman, J. The Elements of Statistical Learning; Springer Series in Statistics; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2009; ISBN 978-0-387-84857-0. [Google Scholar]

- James, G.; Witten, D.; Hastie, T.; Tibshirani, R. An Introduction to Statistical Learning: With Applications in R; Springer Texts in Statistics; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2021; ISBN 978-1-0716-1417-4. [Google Scholar]

- Pawlik, P.; Kania, K.; Przysucha, B. Fault Diagnosis of Machines Operating in Variable Conditions Using Artificial Neural Network Not Requiring Training Data from a Faulty Machine. Eksploat. I Niezawodn. Maint. Reliab. 2023, 25, 168109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kłosowski, G.; Rymarczyk, T.; Niderla, K.; Kulisz, M.; Skowron, Ł.; Soleimani, M. Using an LSTM Network to Monitor Industrial Reactors Using Electrical Capacitance and Impedance Tomography—A Hybrid Approach. Eksploat. I Niezawodn. Maint. Reliab. 2023, 25, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tamam, M.Q.M.; Abdullah, N.R.; Yahya, W.J.; Kadir, H.A.; Putrasari, Y.; Ahmad, M.A. Effects of Ethanol Blending with Methanol-Gasoline Fuel on Spark Ignition Engine Performance and Emissions. J. Adv. Res. Fluid Mech. Therm. Sci. 2021, 83, 54–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doğan, B.; Erol, D.; Yaman, H.; Kodanli, E. The Effect of Ethanol-Gasoline Blends on Performance and Exhaust Emissions of a Spark Ignition Engine through Exergy Analysis. Appl. Therm. Eng. 2017, 120, 433–443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pavlovic, J.; Marotta, A.; Ciuffo, B. CO2 Emissions and Energy Demands of Vehicles Tested under the NEDC and the New WLTP Type Approval Test Procedures. Appl. Energy 2016, 177, 661–670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsokolis, D.; Tsiakmakis, S.; Dimaratos, A.; Fontaras, G.; Pistikopoulos, P.; Ciuffo, B.; Samaras, Z. Fuel Consumption and CO2 Emissions of Passenger Cars over the New Worldwide Harmonized Test Protocol. Appl. Energy 2016, 179, 1152–1165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahariar, G.M.H.; Bodisco, T.A.; Zare, A.; Sajjad, M.; Jahirul, M.I.; Van, T.C.; Bartlett, H.; Ristovski, Z.; Brown, R.J. Impact of Driving Style and Traffic Condition on Emissions and Fuel Consumption During Real-World Transient Operation. Fuel 2022, 319, 123874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| j = 0 | 7.77974 | 0.11166 | 69.67153 | 0 |

| j = 1 | −0.90216 | 0.05313 | −16.98035 | 4.8133 × 10−61 |

| j = 2 | 0.10142 | 0.04486 | 2.26088 | 0.02386 |

| j = 3 | 0.00764 | 0.0027 | 2.83167 | 0.00467 |

| j = 4 | 0.20812 | 0.11319 | 1.8386 | 0.0661 |

| j = 5 | 0.0036 | 0.00132 | 2.72613 | 0.00646 |

| j = 6 | 0.00004719 | 1.3204 × 10−5 | 3.5734 | 0.00036 |

| j = 7 | 0.12972 | 0.0161 | 8.05862 | 1.2223 × 10−15 |

| j = 0 | 7.73088 | 0.09175 | 84.26171 | 0 |

| j = 1 | −0.903 | 0.04446 | −20.30846 | 1.5451 × 10−84 |

| j = 2 | 0.00039 | 0.0458 | 0.00848 | 0.99323 |

| j = 3 | 0.00762 | 0.00237 | 3.21284 | 0.00133 |

| j = 4 | 0.42347 | 0.11549 | 3.66674 | 0.00025 |

| j = 5 | 0.00988 | 0.00135 | 7.2993 | 3.9524 × 10−13 |

| j = 6 | 4.8251 × 10−5 | 1.1938 × 10−5 | 4.04169 | 5.4793 × 10−5 |

| j = 7 | 0.1065 | 0.01603 | 6.64491 | 3.7675 × 10−11 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Laskowski, P.; Kozłowski, E.; Zimakowska-Laskowska, M.; Wiśniowski, P.; Matijošius, J.; Oszczak, S.; Keršys, R.; Wojs, M.K.; Dowkontt, S. Dynamic CO2 Emission Differences Between E10 and E85 Fuels Based on Speed–Acceleration Mapping. Energies 2026, 19, 40. https://doi.org/10.3390/en19010040

Laskowski P, Kozłowski E, Zimakowska-Laskowska M, Wiśniowski P, Matijošius J, Oszczak S, Keršys R, Wojs MK, Dowkontt S. Dynamic CO2 Emission Differences Between E10 and E85 Fuels Based on Speed–Acceleration Mapping. Energies. 2026; 19(1):40. https://doi.org/10.3390/en19010040

Chicago/Turabian StyleLaskowski, Piotr, Edward Kozłowski, Magdalena Zimakowska-Laskowska, Piotr Wiśniowski, Jonas Matijošius, Stanisław Oszczak, Robertas Keršys, Marcin Krzysztof Wojs, and Szymon Dowkontt. 2026. "Dynamic CO2 Emission Differences Between E10 and E85 Fuels Based on Speed–Acceleration Mapping" Energies 19, no. 1: 40. https://doi.org/10.3390/en19010040

APA StyleLaskowski, P., Kozłowski, E., Zimakowska-Laskowska, M., Wiśniowski, P., Matijošius, J., Oszczak, S., Keršys, R., Wojs, M. K., & Dowkontt, S. (2026). Dynamic CO2 Emission Differences Between E10 and E85 Fuels Based on Speed–Acceleration Mapping. Energies, 19(1), 40. https://doi.org/10.3390/en19010040