Comparative Simulation and Optimization of “Continuous Membrane Column” Cascades for Post-Combustion CO2 Capture

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Single-Membrane Unit Model

3. Designs of the Technological Schemes

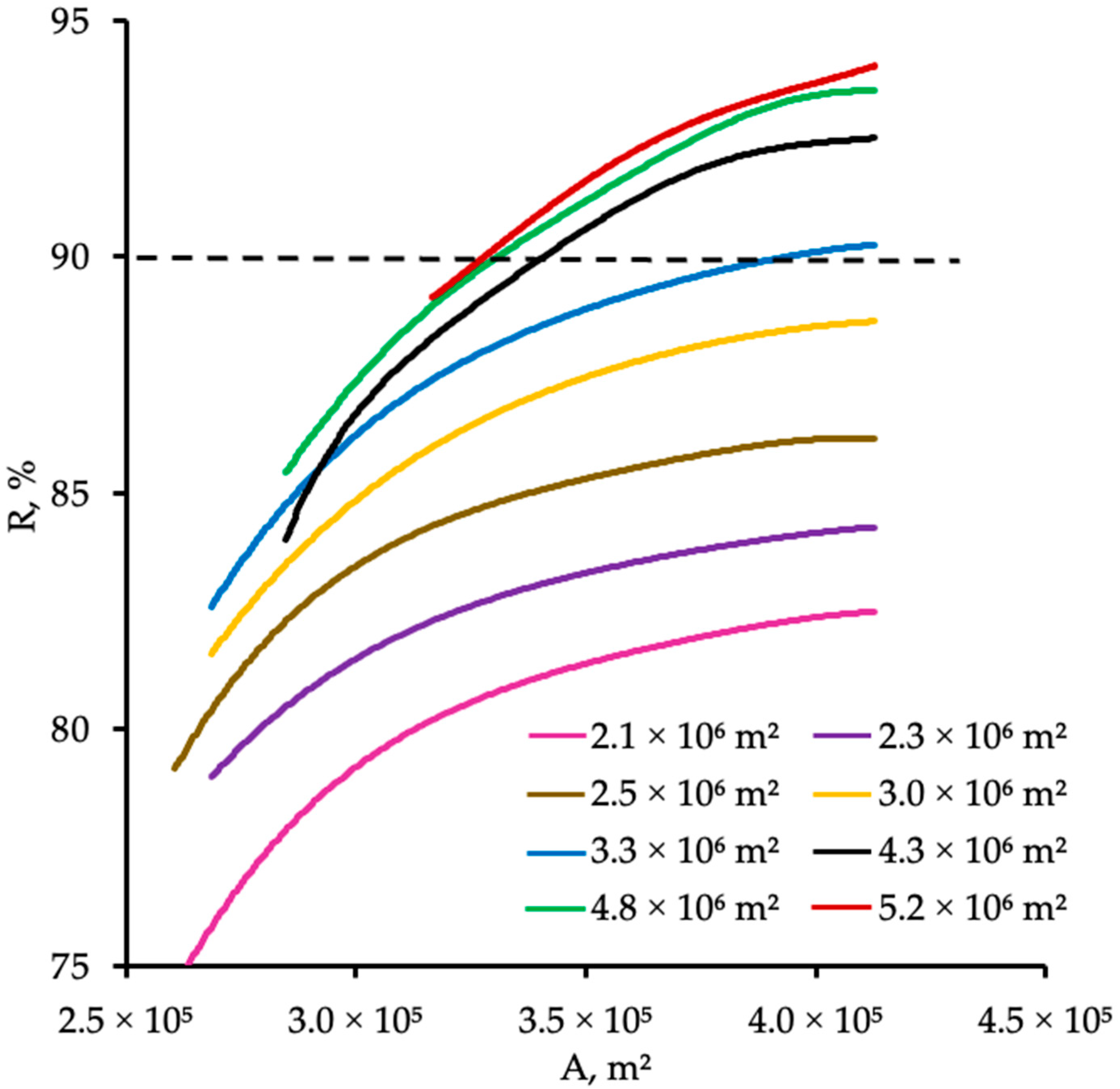

- CO2 recovery ≥ 90%,

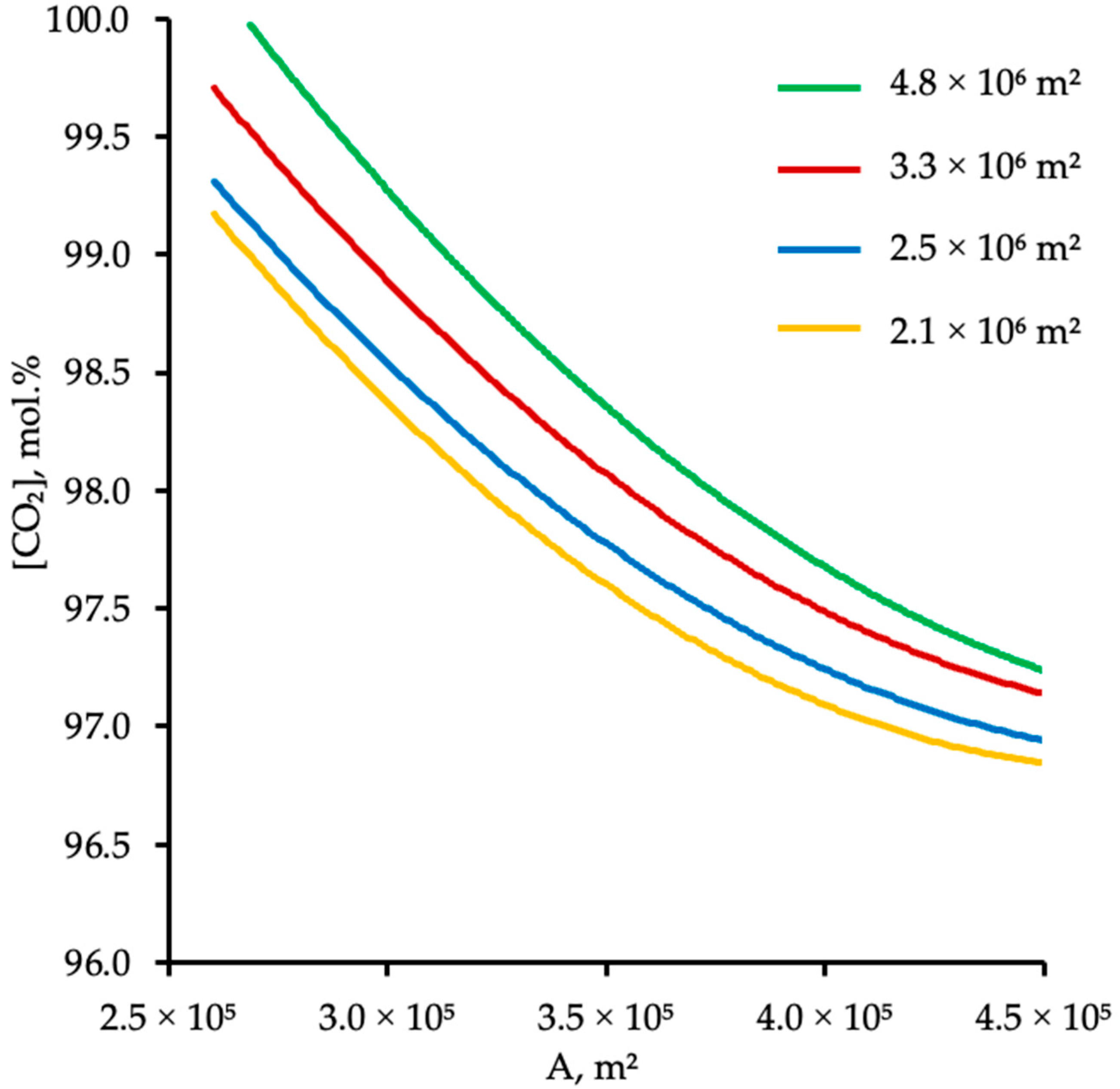

- Product stream purity ≥ 95 mol.%,

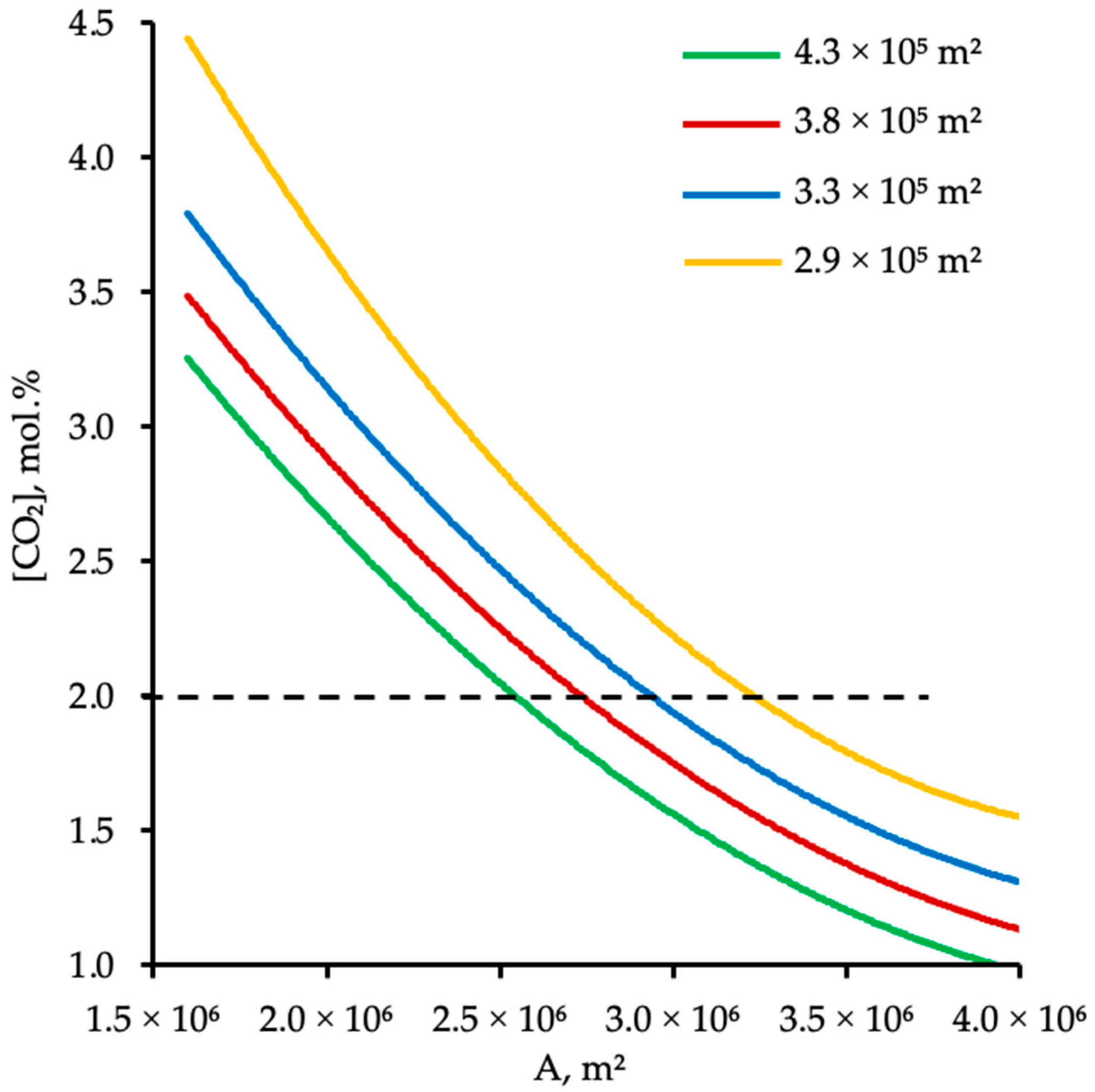

- CO2 concentration in the vent gas ≤ 2 mol.%.

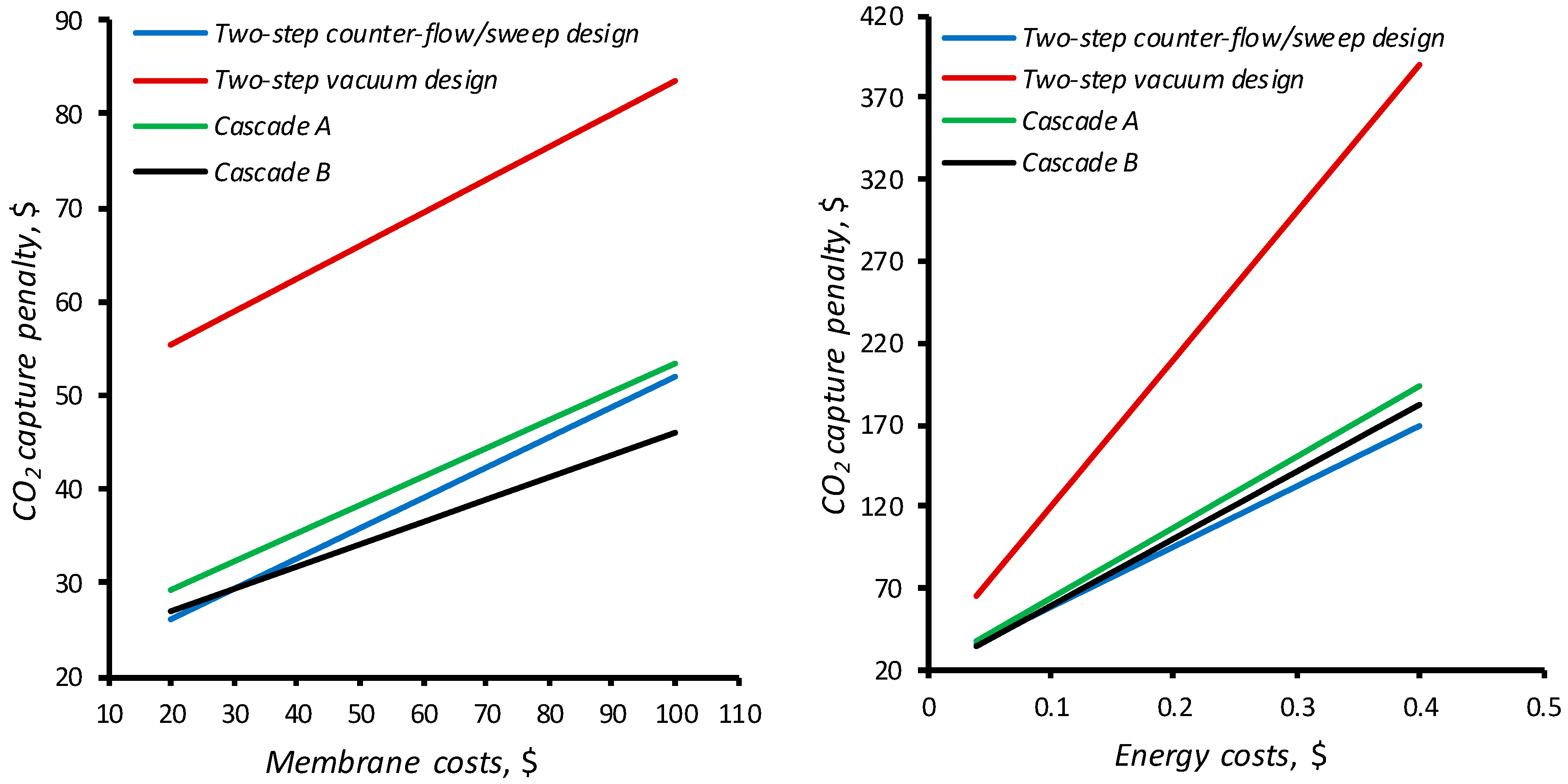

4. Results and Discussion

4.1. Effect of Membrane Selectivity

4.2. Effect of Membrane Area

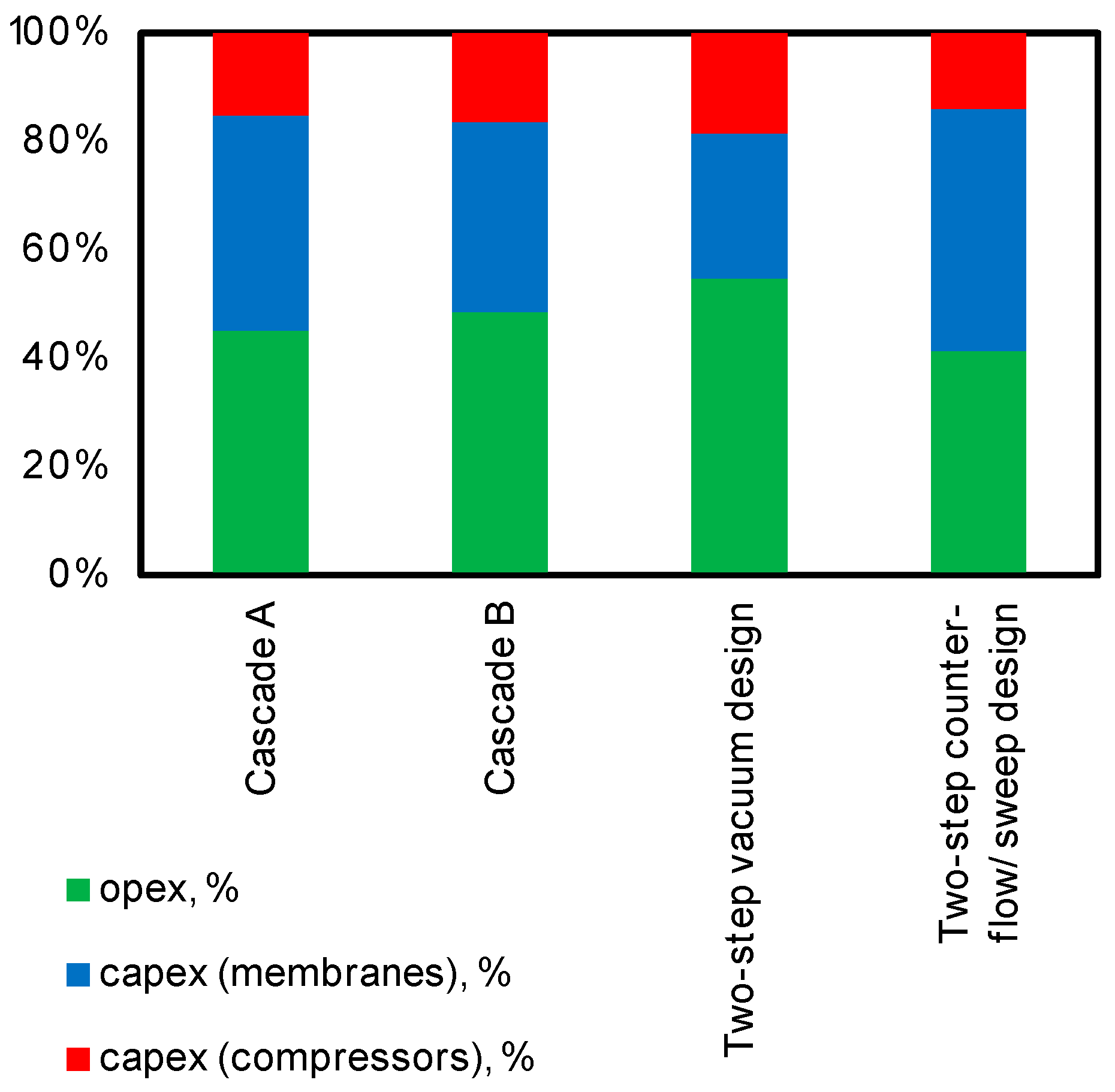

4.3. Feasibility Study for Carbon Dioxide Capture from CHPP Flue Gases

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Choudhry, T.; Kayani, U.N.; Gul, A.; Haider, S.A.; Ahmad, S. Carbon emissions, environmental distortions, and impact on growth. Energy Econ. 2023, 126, 107040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.; Lu, J.; Obobisa, E.S. Striving towards 2050 net zero CO2 emissions: How critical are clean energy and financial sectors? Heliyon 2023, 9, e22705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Looyd, P.J.D. Precombustion technologies to aid carbon capture. In Greenhouse Gas Control Technologies; Elsevier Science Ltd.: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2005; pp. 1957–1961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghoniem, A.F.; Zhao, Z.; Dimitrakopoulos, G. Gas oxy combustion and conversion technologies for low carbon energy: Fundamentals, modeling and reactors. Proc. Combust. Inst. 2019, 37, 33–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raganati, F.; Ammendola, P. CO2 Post-combustion Capture: A Critical Review of Current Technologies and Future Directions. Energy Fuels 2024, 38, 13858–13905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boer, D.G.; Langerak, J.; Pescarmona, P.P. Zeolites as Selective Adsorbents for CO2 Separation. ACS Appl. Energy Mater. 2023, 6, 2634–2656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raganati, F.; Miccio, F.; Ammendola, P. Adsorption of Carbon Dioxide for Post-combustion Capture: A Review. Energy Fuels 2021, 35, 12845–12868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zanco, S.E.; Pérez-Calvo, J.-F.; Gasós, A.; Cordiano, B.; Becattini, V.; Mazzotti, M. Postcombustion CO2 Capture: A Comparative Techno-Economic Assessment of Three Technologies Using a Solvent, an Adsorbent, and a Membrane. ACS Eng. Au 2021, 1, 50–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hack, J.; Maeda, N.; Meier, D.M. Review on CO2 Capture Using Amine-Functionalized Materials. ACS Omega 2022, 7, 39520–39530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laribi, S.; Dubois, L.; De Weireld, G.; Thomas, D. Study of the post-combustion CO2 capture process by absorption-regeneration using amine solvents applied to cement plant flue gases with high CO2 contents. Int. J. Greenh. Gas Control 2019, 90, 102799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Isogai, H.; Nakagaki, T. Mechanistic analysis of post-combustion CO2 capture performance during amine degradation. Int. J. Greenh. Gas Control 2022, 114, 103597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, J.; Yang, W.; Xu, L.; Bei, L.; Lei, S.; Li, W.; Liu, H.; Wang, B.; Sun, L. Review on post-combustion CO2 capture by amine blended solvents and aqueous ammonia. Chem. Eng. J. 2024, 488, 150954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, L.; Ren, Z.; Si, W.; Ma, Q.; Huang, W.; Liao, K.; Huang, Z.; Wang, Y.; Li, J.; Xu, P. Research progress on CO2 capture and utilization technology. J. CO2 Util. 2022, 66, 102260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, H.; Sharma, R.; Malik, A.K.; Sharma, A.K.; Kumar, P.; Singh, D. Advancements in carbon capture and utilization technologies: Transforming CO2 into valuable resources for a sustainable carbon economy. Next Energy 2026, 10, 100476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, T.; Li, R.; Zhang, Z.; Song, C. Current status of onboard carbon capture and storage (OCCS) system: A survey of technical assessment. Carbon Capture Sci. Technol. 2025, 15, 100402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, X.; Khan, M.N.; Thakur, G.C. Machine Learning in Carbon Capture, Utilization, Storage, and Transportation: A Review of Applications in Greenhouse Gas Emissions Reduction. Processes 2025, 13, 1160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Q.; Xiong, J.; Gao, H.; Olson, W.; Liang, Z. Energy-efficient regeneration of amine-based solvent with environmentally friendly ionic liquid catalysts for CO2 capture. Chem. Eng. Sci. 2024, 283, 119380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, X.; He, H.; Barzagli, F.; Amer, M.W.; Li, C.; Zhang, R. Analysis of the energy consumption in solvent regeneration processes using binary amine blends for CO2 capture. Energy 2023, 270, 126903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rochelle, G.T. Thermal degradation of amines for CO2 capture. Curr. Opin. Chem. Eng. 2012, 1, 183–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bedell, S.A. Oxidative degradation mechanisms for amines in flue gas capture. Energy Procedia 2009, 1, 771–778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Voice, A.K.; Rochelle, G.T. Oxidation of amines at absorber conditions for CO2 capture from flue gas. Energy Procedia 2011, 4, 171–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, J.; Wang, S.; Zhou, S.; Zhao, B.; Chen, C. Corrosion and degradation performance of novel absorbent for CO2 capture in pilot-scale. Energy Procedia 2011, 4, 1534–1541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, J.W.; Heo, S.; Yeo, J.G.; Lee, S.; Kim, J.K.; Lee, J.H. Membrane-Based CO2 Capture Across Industrial Sectors: Process Conditions, Case Studies, and Implementation Insights. Membranes 2025, 15, 200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pazani, F.; Shariatifar, M.; Maleh, M.S.; Alebrahim, T.; Lin, H. Challenge and promise of mixed matrix hollow fiber composite membranes for CO2 separations. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2023, 308, 122876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Favre, E. Carbon dioxide recovery from post-combustion processes: Can gas permeation membranes compete with absorption? J. Memb. Sci. 2007, 294, 50–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, D.; Wang, Z.; Wang, J.; Wang, S. Potential of Two-Stage Membrane System with Recycle Stream for CO2 Capture from Postcombustion Gas. Energy Fuels 2009, 23, 4755–4762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, L.; Riensche, E.; Weber, M.; Stolten, D. Cascaded Membrane Processes for Post-Combustion CO2 Capture. Chem. Eng. Technol. 2012, 35, 489–496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Micari, M.; Dakhchoune, M.; Agrawal, K.V. Techno-economic assessment of postcombustion carbon capture using high-performance nanoporous single-layer graphene membranes. J. Memb. Sci. 2021, 624, 119103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, Z.; Mahurin, S.M.; Dai, S.; Jiang, D. Ion-Gated Gas Separation through Porous Graphene. Nano Lett. 2017, 17, 1802–1807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- He, G.; Huang, S.; Villalobos, L.F.; Zhao, J.; Mensi, M.; Oveisi, E.; Rezaei, M.; Agrawal, K.V. High-permeance polymer-functionalized single-layer graphene membranes that surpass the postcombustion carbon capture target. Energy Environ. Sci. 2019, 12, 3305–3312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- GitHub—CCSI-Toolset/membrane_model: Membrane Separation Model: Updated Hollow Fiber Membrane Model and System Example for Carbon Capture. Available online: https://github.com/CCSI-Toolset/membrane_model (accessed on 25 November 2021).

- Merkel, T.C.; Lin, H.; Wei, X.; Baker, R. Power plant post-combustion carbon dioxide capture: An opportunity for membranes. J. Memb. Sci. 2010, 359, 126–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kniep, J.; Sun, Z.; Lin, H.; Mohammad, M.; Thomas-Droz, S.; Vu, J.; He, Z.; Merkel, T.; Amo, K. Field Tests of MTR Membranes for Syngas Separations: Final Report of CO2-Selective Membrane Field Test Activities at the National Carbon Capture Center; Membrane Technology and Research, Inc.: Newark, CA, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Hwang, S.-T.; Thorman, J.M. The continuous membrane column. AIChE J. 1980, 26, 558–566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vorotyntsev, V.; Drozdov, P.N. Ultrapurification of gases in a continuous membrane column cascade. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2001, 22–23, 367–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y.; Merkel, T.C.; Baker, R.W. Pressure ratio and its impact on membrane gas separation processes. J. Memb. Sci. 2014, 463, 33–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robeson, L.M. The upper bound revisited. J. Memb. Sci. 2008, 320, 390–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Rao, S.; Han, Y.; Pang, R.; Ho, W.S.W. CO2-selective membranes containing amino acid salts for CO2/N2 separation. J. Memb. Sci. 2021, 638, 119696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Comesaña-Gándara, B.; Chen, J.; Bezzu, C.G.; Carta, M.; Rose, I.; Ferrari, M.C.; Esposito, E.; Fuoco, A.; Jansen, J.C.; McKeown, N.B. Redefining the Robeson upper bounds for CO2/CH4 and CO2/N2 separations using a series of ultrapermeable benzotriptycene-based polymers of intrinsic microporosity. Energy Environ. Sci. 2019, 12, 2733–2740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, M.; Nothling, M.D.; Zhang, S.; Fu, Q.; Qiao, G.G. Thin film composite membranes for postcombustion carbon capture: Polymers and beyond. Prog. Polym. Sci. 2022, 126, 101504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Batoon, V.; Borsaly, A.; Casillas, C.; Hofmann, T.; Huang, I.; Kniep, J.; Merkel, T.; Paulaha, C.; Salim, W.; Westling, E. Scale-Up Testing of Advanced PolarisTM Membrane CO2 Capture Technology. SSRN Electron. J. 2022, 23–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bozorg, M.; Ramírez-Santos, Á.A.; Addis, B.; Piccialli, V.; Castel, C.; Favre, E. Optimal process design of biogas upgrading membrane systems: Polymeric vs high performance inorganic membrane materials. Chem. Eng. Sci. 2020, 225, 115769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variable | Typical | Base Case |

|---|---|---|

| Inner Fiber Diameter, μm | 100–700 | 400 |

| Outer Fiber Diameter, μm | 200–800 | 600 |

| Effective Fiber Length, m | 0.15–1.50 | 1.00 |

| Permeance, GPU * | 10–10,000 | 1000 |

| Parameter | Value |

|---|---|

| Feed flow, kmol h−1 | 67,543.8 |

| Pressure, MPa | 0.1 |

| Temperature, °C | 50 |

| Composition, mol.% | |

| N2 | 73 |

| CO2 | 11.6 |

| H2O | 11 |

| O2 | 4.4 |

| Parameter | Value | Units |

|---|---|---|

| Pressure in the feed side, MPa | 0.15 | MPa |

| Pressure in the permeate side, MPa | 0.02 | MPa |

| Membrane area, m2 | ||

| Membrane permeance, GPU | 1000 | GPU |

| α (CO2/N2) | 50 | |

| α (CO2/H2O) | 0.3 | |

| α (CO2/O2) | 12.5 | |

| CO2 content, mol.% | ||

| Product flow | ≥95 | mol.% |

| Residual flow | ≤2 | mol.% |

| Cascade A (Figure 2A) | ||

| Stripping section | 3.15 × 106 | m2 |

| Enrichment section | 4.3 × 105 | m2 |

| Cascade B (Figure 2B) | ||

| Stripping section | 2.8 × 106 | m2 |

| Enrichment section | 1.4 × 104 | m2 |

| Merkel et al. [32] Two-step vacuum design | ||

| Step 1 | 1.7 × 106 | m2 |

| Step 2 | 2.5 × 106 | m2 |

| Merkel et al. [32] Two-step counter-flow/sweep design | ||

| Step 1 | 3.5 × 106 | m2 |

| Step 2 | 2.6 × 105 | m2 |

| Compressor Unit | Costs, M USD |

|---|---|

| Cascade A (Figure 2A) | |

| Feed stream compressor | 12.4 |

| Vacuum-compressor unit | 35.3 |

| Pre-condenser stream compressor | 20.6 |

| Cascade B (Figure 2B) | |

| Feed stream compressor | 12.4 |

| Pre-condenser stream compressor | 53.0 |

| Merkel et al. [32] Two-step vacuum design | |

| Feed stream and recycle compressor | 89.1 |

| Pre-condenser stream compressor | 53.5 |

| Merkel et al. [32] Two-step counter-flow/sweep design | |

| Feed stream compressor | 12.4 |

| Pre-condenser stream compressor | 46.2 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Smorodin, K.A.; Atlaskin, A.A.; Kryuchkov, S.S.; Atlaskina, M.E.; Tsivkovsky, N.S.; Sysoev, A.A.; Zhmakin, V.V.; Petukhov, A.N.; Suvorov, S.S.; Vorotyntsev, A.V.; et al. Comparative Simulation and Optimization of “Continuous Membrane Column” Cascades for Post-Combustion CO2 Capture. Energies 2026, 19, 303. https://doi.org/10.3390/en19020303

Smorodin KA, Atlaskin AA, Kryuchkov SS, Atlaskina ME, Tsivkovsky NS, Sysoev AA, Zhmakin VV, Petukhov AN, Suvorov SS, Vorotyntsev AV, et al. Comparative Simulation and Optimization of “Continuous Membrane Column” Cascades for Post-Combustion CO2 Capture. Energies. 2026; 19(2):303. https://doi.org/10.3390/en19020303

Chicago/Turabian StyleSmorodin, Kirill A., Artem A. Atlaskin, Sergey S. Kryuchkov, Maria E. Atlaskina, Nikita S. Tsivkovsky, Alexander A. Sysoev, Vyacheslav V. Zhmakin, Anton N. Petukhov, Sergey S. Suvorov, Andrey V. Vorotyntsev, and et al. 2026. "Comparative Simulation and Optimization of “Continuous Membrane Column” Cascades for Post-Combustion CO2 Capture" Energies 19, no. 2: 303. https://doi.org/10.3390/en19020303

APA StyleSmorodin, K. A., Atlaskin, A. A., Kryuchkov, S. S., Atlaskina, M. E., Tsivkovsky, N. S., Sysoev, A. A., Zhmakin, V. V., Petukhov, A. N., Suvorov, S. S., Vorotyntsev, A. V., & Vorotyntsev, I. V. (2026). Comparative Simulation and Optimization of “Continuous Membrane Column” Cascades for Post-Combustion CO2 Capture. Energies, 19(2), 303. https://doi.org/10.3390/en19020303