1. Introduction

Climate change poses a significant and urgent global crisis to humanity, representing a long-term, profound challenge that directly impacts human life, health, and the sustainable development of socioeconomic systems. Accelerating the reduction in greenhouse gases such as carbon dioxide emissions is the most fundamental strategy for tackling climate change. With growing attention paid to the concept of sustainable development, the circular economy is increasingly becoming a hot topic of concern. Relevant studies have conducted more systematic and quantitative research on the synergistic effects between climate change mitigation and the circular economy. This research covers multiple dimensions, such as industrial chains and technological innovation. The study areas involve energy, transportation, construction, and manufacturing, etc. For countries and cities that are accelerating their efforts to address climate change and reduce pollution, the strategic position of the circular economy is rising to become the core solution to tackle climate change.

China’s voluntary announcement of its carbon peak and carbon neutrality goals (dual carbon goals) demonstrates its resolve to address global climate change. Within the framework of China’s dual carbon goals, carbon reduction based on the circular economy has emerged as a strategic direction for the coordinated advancement of technology, industry and policy [

1]. China is the world’s largest energy consumer and carbon emitter, accounting for 26.1% of global total energy consumption and 30.7% of total carbon emissions from energy combustion [

2]. Amid profound shifts in the global energy supply-demand landscape and the convergence of traditional and emerging risks to domestic energy security, China’s clean and low-carbon development has entered a critical phase of addressing complex challenges. Achieving China’s dual carbon goals imposes more stringent demands on the efficiency of energy resource circularity and low-carbon technologies [

3]. Energy conservation serves as a critical means to address fundamental resource and environmental bottlenecks in China, while also acting as a key enabler for fostering a green development paradigm and supporting the attainment of these dual carbon goals [

4].

As the dominant contributor to China’s energy consumption and carbon emissions, the industrial sector accounts for over 65% of terminal energy use and more than 70% of national carbon emissions. However, constrained by technological and infrastructural limitations, China’s industrial energy efficiency remains below the global advanced level. Consequently, 50–70% of energy input in industrial processes is dissipated as waste heat, primarily in waste gas streams, wastewater, and residual heat [

4]. This low efficiency has perpetuated a precarious balance between China’s energy demand and supply [

5], while the direct discharge of waste heat exacerbates environmental challenges.

It is important to note that a considerable potential for the recovery of waste heat exists in key industrial sectors, including petrochemicals and cement. In the context of the ongoing energy transition, the strategic value of waste heat has become increasingly prominent. The recovery and utilization of resources not only directly reduce energy consumption intensity but also enhance overall energy system efficiency through multi-energy complementary, positioning it as a critical pathway towards achieving China’s dual carbon goals [

6].

Despite the growing attention to industrial decarbonization and industrial waste heat utilization, previous work suffers from three key limitations. First, existing waste heat potential evaluations tend to focus on static or a single technology device potential quantification, failing to capture the long-term dynamic evolution of waste heat utilization potential considering a combination of technologies. Second, in terms of assessment methods, existing research tends to construct technology-specific models of waste heat utilization. These models have some limitations in the analysis of the cross-industry effects of waste heat utilization. Third, few studies have quantitatively linked waste heat utilization to climate benefits, such as shortening the time to carbon peaking or reducing the carbon emission peak, resulting in insufficient policy-relevant evidence.

To address these gaps, this study makes three key contributions: (1) It constructs an energy technology coupling model to conduct a nationwide assessment of industrial waste heat utilization potential, overcoming the limitations of industry-specific studies. (2) It identifies the evolution pattern of industrial waste heat potential and the growing dominance of low-grade waste heat, filling the gap in structural and temporal analysis of waste heat resources. (3) It quantifies the impacts of waste heat utilization on primary energy conservation and dual carbon goals, and clarifies the role of industrial waste heat in the low-carbon transition and offers actionable insights for related policies.

The remainder of this study is organized as follows:

Section 2 reviews the relevant literature.

Section 3 describes the methodology, including scenario design and data sources.

Section 4 presents and discusses the main results.

Section 5 provides the conclusions and corresponding policy recommendations.

3. Methods

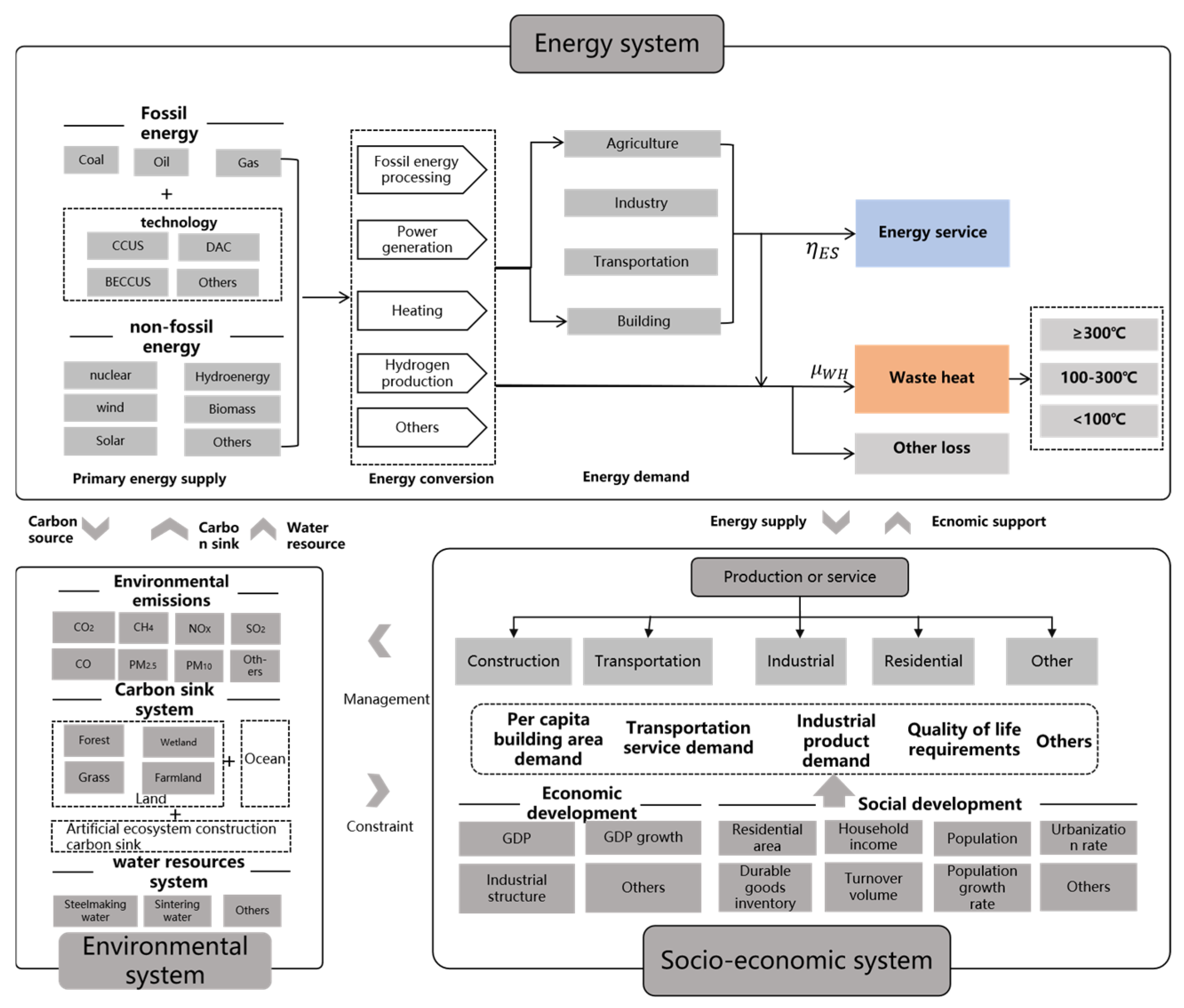

Energy transition does not proceed in isolation within the energy system. Rather, it co-evolves dynamically with the socioeconomic and environmental systems. To analyze the systemic interaction, this study constructs the National Energy Strategy and Alternatives Planning (NESAP) model, which is driven by energy service demand projections. The NESAP model decomposes energy output into three components: energy directly used for energy services, waste heat loss, and other forms of energy loss. Feasible combinations of energy technologies are incorporated as parameters into the model, such as waste heat recovery, power generation, heating, hydrogen production, and carbon management. Specifically, waste heat utilization technologies mainly include three types. Direct utilization, power recovery utilization, and comprehensive utilization [

25]. Direct utilization involves preheating combustion air and heating materials. Power recovery utilization generates power through thermomechanical conversion technology for direct application to water pumps, fans, compressors and other equipment. Comprehensive utilization achieves integrated waste heat recovery through gradient extraction based on temperature levels, such as combined heating, cooling and power supply [

26]. This enables quantitative evaluation of two core objectives: the utilization potential of industrial waste heat, and its impact on China’s carbon peaking and carbon neutrality pathway.

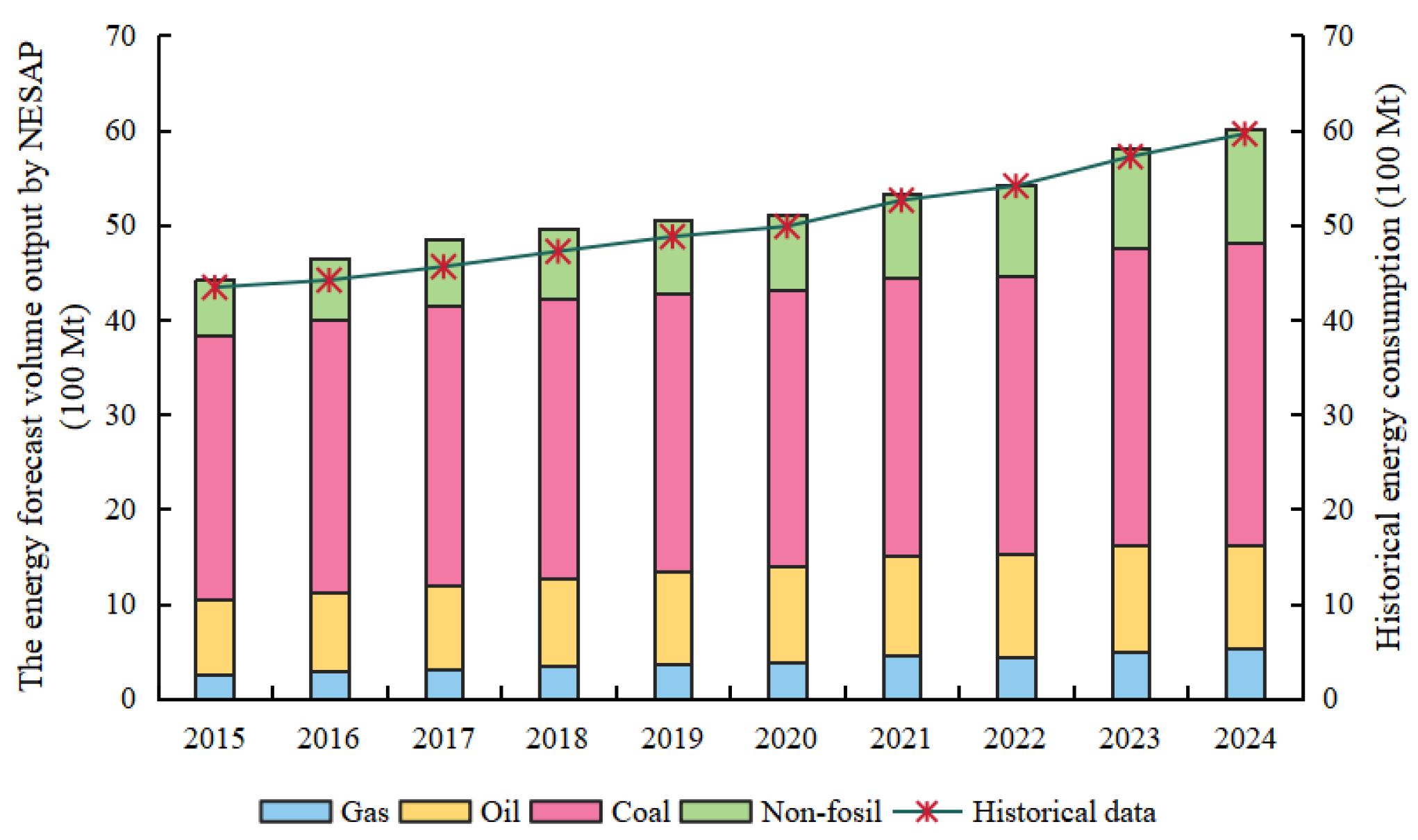

The NESAP model adopts an annual temporal resolution for the study period, with key transition periods highlighted for scenario analysis. This temporal setup balances computational efficiency and analytical precision. Key parameters and model outputs were calibrated using historical data from 2015 to 2019, with relative errors controlled within ±5%. The specific framework of this model is presented in

Figure 1.

As shown in

Figure 1, the socio-economic system includes two components: economic development, such as economic growth rate, industrial structure, etc., and people’s livelihood, such as residential area, household income, etc. This subsystem drives the energy service demand, which covers segmented sectors such as agriculture, industry, transportation, etc. The energy system consists of energy input, low-carbon technologies, and energy conversion processes. The conversion outputs provide energy services to socio-economic sectors, while generating waste heat loss (in exhaust gas, wastewater, etc.) and other losses. The environmental system acts as a constraint and support. It is affected by environmental emissions (CO

2, CH

4, etc.) generated by energy services. The carbon sink system provides emission mitigation and resource support for the entire framework.

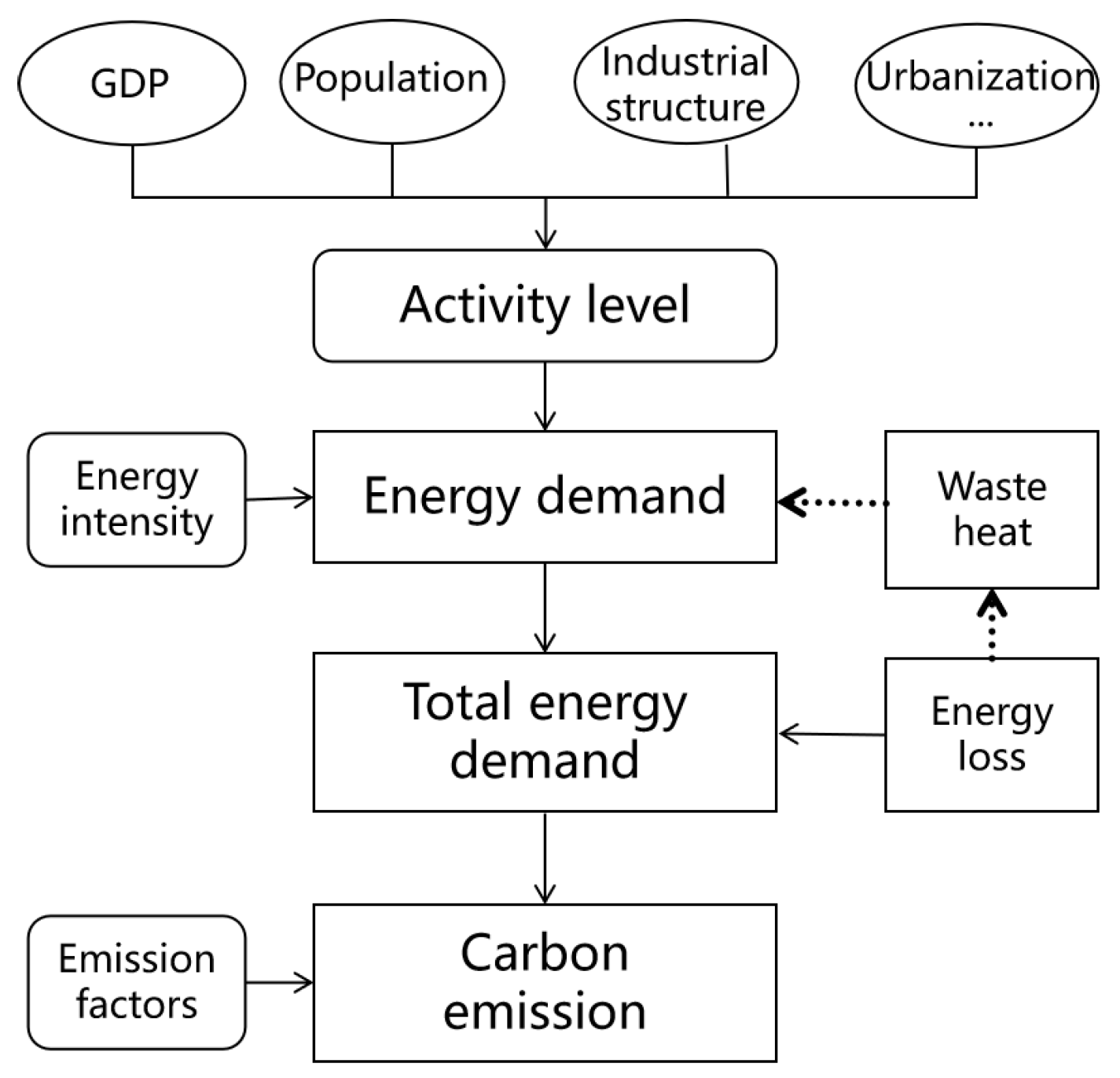

In coupling dimensions, it links the socio-economic demand side, energy supply side, and environment constraint side via quantitative parameters such as waste heat loss coefficient μ. In operational logic, it simulates the cascaded feedback mechanism through scenario-based parameter iteration. The flow-sheet for the calculation of energy consumption and CO

2 emission is shown in

Figure 2. The advantages of this model enable quantitative linkage between industrial waste heat utilization and climate benefits, which fills the gap in previous studies’ qualitative analysis. It also integrates policy constraints and resource limits into the coupling system, making the results more policy-relevant. Moreover, it is tailored to energy-intensive sectors, with fine-grained sectoral sub-items that improve practical applicability. The industry branch is divided into several sub-branches: power generation, steel, non-metallic mineral manufacturing, chemical industry, fuel processing, non-ferrous metals, paper, apparel, and other key industrial sectors.

Correspondingly, the model’s accuracy relies on the availability of segmented sectoral data, which may lead to minor deviations in less data-rich sub-sectors. Meanwhile, it currently adopts a national-scale analysis and does not fully incorporate regional heterogeneity in energy structure and waste heat resources. In the future, we will enrich and improve regional modeling.

In terms of energy demand, this study employs a bottom-up approach for calculation, namely by multiplying activity levels by energy intensity. In the NESAP model, the energy consumption of end-use sectors is mainly calculated using two parameters: energy intensity and activity level. In the modeling practice of this study, three calculation schemes are adopted. For specific industries with a high degree of product homogenization, such as the steel, cement, and aluminum industries, product output is typically regarded as the activity level in relevant research. For industries like food manufacturing and light industry, due to the existence of numerous heterogeneous factors in products, technologies and production processes, the added economic value is commonly used as the activity level in research. For the residential sector, income is taken as the activity level. Drawing on the identity concept proposed by Kaya, this study decomposes China’s end-use energy consumption as follows:

The equation is divided into two parts. In the first part, m denotes different industrial sectors, including agriculture, industry, buildings and transportation. In the second part, n represents two resident categories, namely urban residents and rural residents. Herein, k indicates energy types consumed by each sector, such as coal, petroleum products, natural gas and electricity. GDP and GDPm denote China’s Gross Domestic Product (GDP) and the value-added of each industrial sector, respectively. P and Pn represent China’s permanent resident population and the size of the urban or rural population, respectively. Incn denotes the total disposable income of urban or rural households. ECm, ECn, ECmk and ECnk denote the total energy consumption of sector m, and resident category n, and the standard coal equivalent of the k-th energy type consumed by sector m and household category n, respectively.

In the process from power generation to final use, there are transmission losses, and the loss amount is [

3]:

Among them,

Loss refers to the amount of power transmission loss, and

is the energy transmission efficiency.

ECpower is the primary energy input in the power generation industry.

Elepower,i is the power generation volume of technology

i, and

i is the power generation efficiency of technology

i. In terms of carbon emission trend prediction, this paper utilizes energy forecast data to calculate the carbon emissions of various energy sources in industries such as steel. The emission coefficient method is employed to determine the emissions of specific energy sources, and the total emissions are obtained by aggregating the carbon emissions of different energy sources. The calculation formula is as follows:

Among them,

EM represents carbon emissions,

ECk is the consumption of the

k-th type of energy, and

EFk is the combustion carbon emission factor of the k-th type of energy. In addition to energy combustion, industrial production also generates process emissions, which are calculated by multiplying the output of industrial products by the process emission factor:

Among them,

ALm denotes the production level of industry

m.

refers to the industrial process emissions of industrial products, and

EFprocess represents the industrial process emission factor for products such as steel. The carbon sink capacity is mainly calculated based on the area of land use types and the carbon sink rate:

Among them, Csink represents the natural carbon sink capacity; Areaj is the area of the j-th type of land use, which mainly includes forests, grasslands, wetlands, water areas, crops, etc.; Rj is the carbon sink rate coefficient per unit area of the j-th type of carbon sink source (tCO2/ha/year).

In this study, the calculation of waste heat involves two core concepts, namely total waste heat potential and waste heat utilization potential. The total waste heat potential refers to the theoretical maximum amount of waste heat generated from all energy-consuming processes within the research scope. It represents the upper limit of waste heat resources in the energy system, providing a fundamental baseline for evaluating the overall scale of waste heat. The waste heat utilization potential denotes the portion of the total waste heat potential that is technically and economically recoverable under practical conditions. As a subset of total waste heat potential, it reflects the actual available waste heat resources for engineering applications and policy formulation. The calculation of total waste heat potential mainly uses energy consumption and waste heat loss rate, and the calculation method is as follows:

Among them,

EWH is the total waste heat potential,

EC is the energy consumption,

is the proportion of the

k-th type of energy in the

m-th industry, and

is the waste heat loss rate of the

k-th type of energy in the

m-th industry. The effective waste heat potential is calculated using Carnot’s theorem, which stipulates that the maximum efficiency of a heat engine is determined by the ambient temperature (298.15 K) and the maximum temperature:

Among them,

is the maximum waste heat utilization potential,

Tlow is defined as the ambient temperature (298.15 K), and

Thigh is the waste heat temperature. The calculation method of waste heat utilization potential is as follows:

The carbon reduction effect of waste heat utilization is analyzed in a quantitative form:

where

Y represents greenhouse gas emissions.

X represents the recycling level of waste heat.

a is a constant term.

β is the undetermined coefficient of the model.

ε is the random error term of the model.

5. Results and Analysis

5.1. Analysis of Waste Heat Utilization Potential

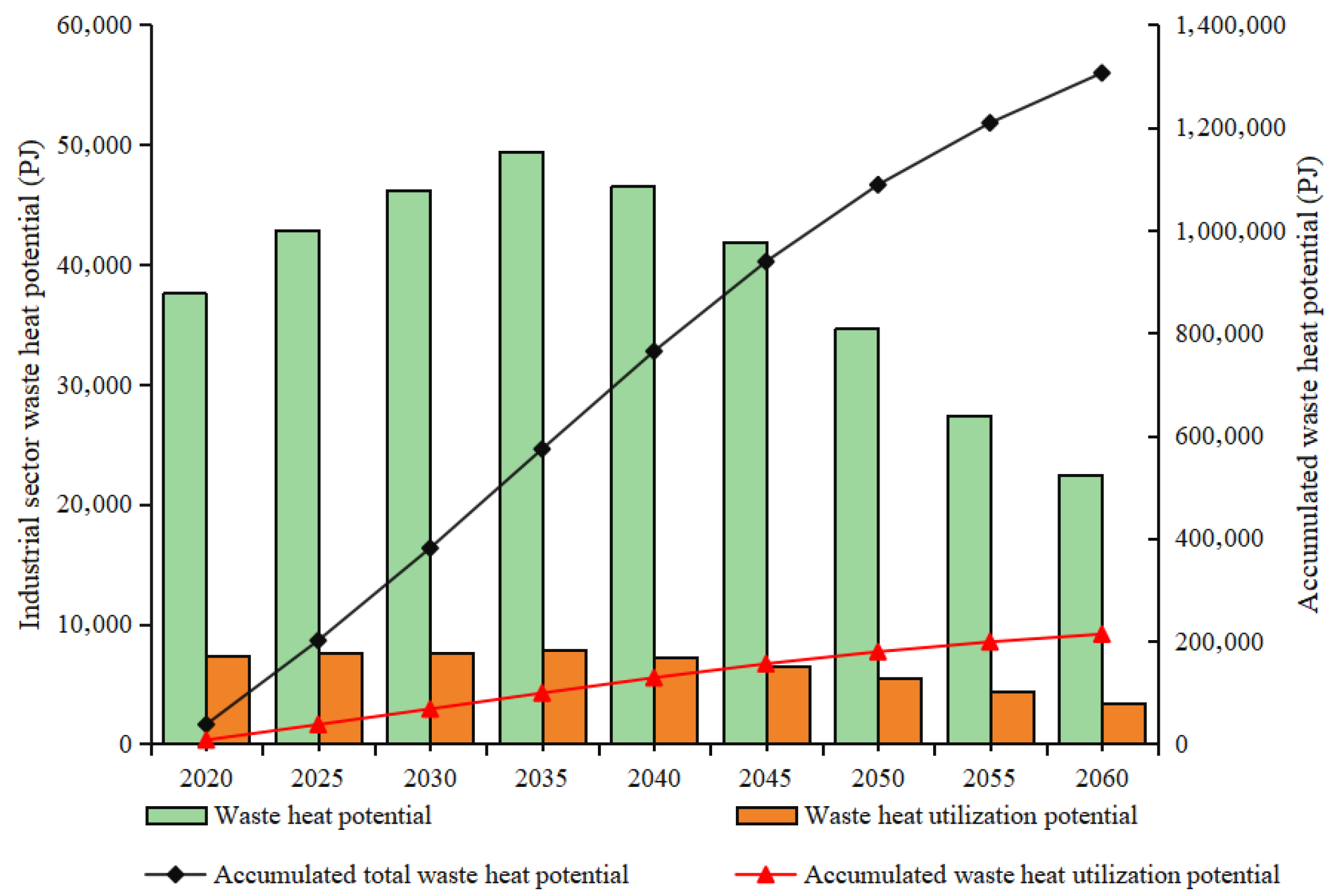

Employing assumptions with respect to China’s socio-economic development and parameters reported in

Table 1,

Table 2,

Table 3 and

Table 4, the total waste heat potential estimates for the period 2020–2060 are presented in

Figure 4. Derived from the above estimates, we find that the total waste heat potential of China’s industrial sector is projected to exhibit an inverted U-shaped temporal trend. Specifically, due to the rigid energy consumption growth in the industrial sector, the total waste heat potential will sustain a relatively stable growth rate during 2020–2035. The total waste heat potential is expected to reach 49,401 Petajoules (PJ) by 2035, from 37,608 PJ in 2020, with an annual growth rate of 1.8%. The turning point in the total waste heat potential pathways from 2035 is mainly due to the effective control of the primary energy consumption. By 2060, the total waste heat potential will decrease to 22,467 PJ.

It should be pointed out that not all waste heat can be recycled. The portion that can be recycled is called waste heat utilization potential. As shown in

Figure 4, the waste heat utilization potential will stabilize at around 7500 PJ from 2030 to 2035. However, its proportion in the total waste heat potential resources drops from 19.6% in 2020 to 15.9% in 2035. This is primarily attributed to the fact that high-grade waste heat is predominantly derived from fossil fuel combustion. As the share of fossil fuel consumption gradually declines, the waste heat utilization potential accordingly exhibits a commensurate downward trajectory. Beyond 2035, against the backdrop of a further decline in total energy consumption, the waste heat utilization potential will accordingly exhibit a steady downward temporal trend, dropping to 3416 PJ by 2060 in China. The cumulative total waste heat potential shows a steady upward trend, which will reach about 1.3 million PJ in 2060.

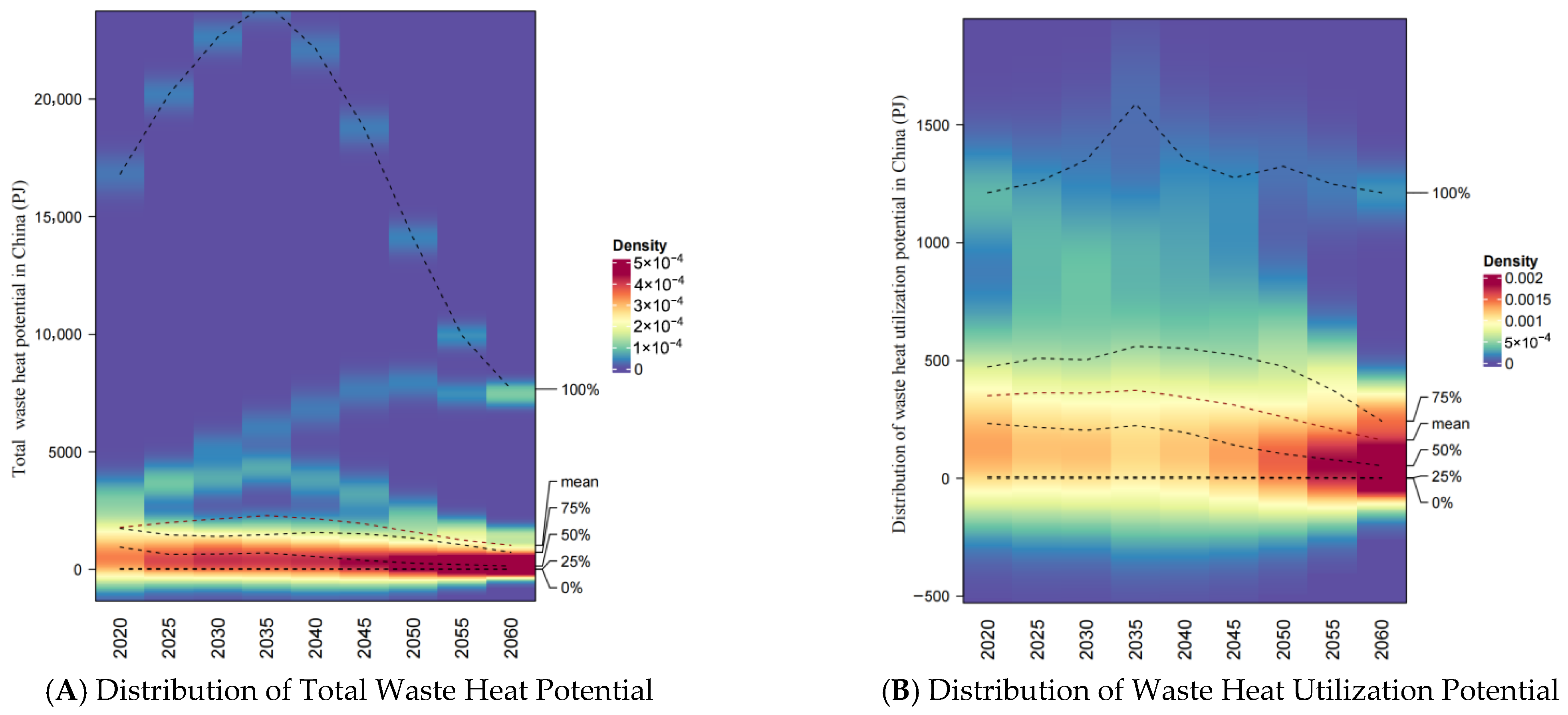

Figure 5A,B show the trend of waste heat potential distribution in the industrial sector. Each row represents the distribution of waste heat potential, and each column represents time. Red indicates a higher distribution density of the industry, light yellow indicates a medium density, and dark blue indicates a lower density. In the near and medium term, the distribution of total waste heat potential exhibits substantial heterogeneity across different sectors, with its main concentration within the range of 0–2500 Petajoules (PJ), as shown in

Figure 5A. Regarding the distribution of waste heat utilization potential, there is a large heterogeneity during 2020–2045. Afterwards, this heterogeneity gradually decreased and was mainly distributed at 500 PJ in 2060, as shown in

Figure 5B.

5.2. Industry and Grade Heterogeneity of Waste Heat Distribution

Figure 6 shows the evolution trend of waste heat utilization potential in different industries. Over the period 2025–2035, the iron and steel sector will remain the primary contributor to industrial waste heat utilization potential in China, and its proportion is projected to be 1666 PJ, accounting for 22% by 2025. Yet, amid shifts in product demand and process structure upgrading, the waste heat utilization potential will follow a downward trajectory, falling to 1390 PJ by 2035. The waste heat utilization potential of the power generation industry will increase at an average annual growth rate of 1.7% between 2025 and 2035. By 2035, it will reach 1423 PJ, accounting for 18% of the total waste heat utilization potential. By then, it will overtake the iron and steel industry to become the sector with the highest waste heat utilization potential.

By 2060, the waste heat utilization potential of the iron and steel industry will decrease by 398 PJ, representing a 71.4% drop compared with 2035 levels. With the phased decommissioning of coal-fired power, the waste heat utilization potential of the power generation industry will steadily decline. By 2060, it will drop to 453 PJ. The waste heat utilization potential of the non-metallic mineral industry will show a downward trend, with waste heat utilization potential decreasing by 90.1% compared with 2035. The waste heat utilization potential of industries such as non-ferrous metals, the chemical industry, and fuel processing will undergo modest changes, with the total remaining at approximately 1000 PJ. By 2060. The waste heat utilization potential of other industries will drop to 1402 PJ.

Predictions of subdivided waste heat temperature categories indicate that China’s industrial sector is dominated by low-grade waste heat below 100 °C as is shown in

Table 6. This low-grade waste heat is projected to account for 66% of total waste heat in 2025, and this share will steadily rise to 83% by 2060. Middle-grade waste heat between 100 °C and 300 °C accounts for 24% of the total waste heat in 2025. High-grade waste heat above 300 °C (Including 300 °C) exhibits relatively limited exploitable potential, accounting for only 10% of waste heat utilization potential by 2025 and declining to 4% by 2060. However, amid the steady reduction in fossil energy consumption across energy-intensive industries such as iron and steel and thermal power, the share of middle- and high-grade waste heat utilization is steadily declining. By 2060, the share of middle-grade waste heat will fall to 13%, while that of high-grade waste heat will decline to 4%.

Figure 7 illustrates the probability distribution curves of waste heat utilization potential across China’s industrial sector, segmented by temperature grade for 2035 and 2060.

Figure 7A shows that in 2035, the waste heat utilization potentials for most industries are concentrated around 375 PJ for low-grade (<100 °C), 600 PJ for middle-grade (100–300 °C), and 400 PJ for high-grade (≥300 °C) categories. By 2060, the entire distribution curves shift leftward compared to those in 2035, as shown in

Figure 7B: the low-grade distribution curve moves to around 364 PJ. Middle-grade distribution curve shows the most significant leftward shift, concentrating near 229 PJ. The high-grade distribution curve also shifts left, centering around 200 PJ. In summary, amid China’s energy transition, the waste heat utilization potential across temperature grades shows a marked leftward shift in its distribution. This reflects a systematic reduction in the quality and quantity of available waste heat, which is most pronounced for middle- and high-grade waste heat.

5.3. Analysis on the Impact of Waste Heat Utilization on the Dual Carbon Pathway

The findings demonstrate that making full use of waste heat yields consistent energy-saving benefits across the industrial sector. However, it displays distinct features of uneven evolution. From 2025 to 2060, industrial sector energy consumption shows a downward trend, indicating that waste heat utilization delivers energy-saving effects. Among them, the initial energy-saving range of energy-intensive industries, such as non-ferrous metals exceeds 13%, as shown in

Table 7. Notably, the power generation industry’s energy-saving rate fluctuates marginally at roughly 2.3%, primarily due to the model taking into account the mandatory configuration requirements of CCUS systems in coal-fired power units. The typical amine-based carbon capture system integrated into the model diminishes power generation efficiency, with its parasitic energy consumption offsetting a portion of the waste heat utilization potential.

The energy-saving effects across industries exhibit convergence over time. In the near and medium term, disparities in initial energy-saving rates among industrial sectors stand at 14.4 percentage points, ranging from −16.7% to −2.3%. By 2060, however, the range of energy-saving benefits narrows to 6.7 percentage points, ranging from −10.6% to −2.3%. This technological convergence phenomenon indicates that the law of diminishing marginal returns in waste heat utilization is universal across different industries.

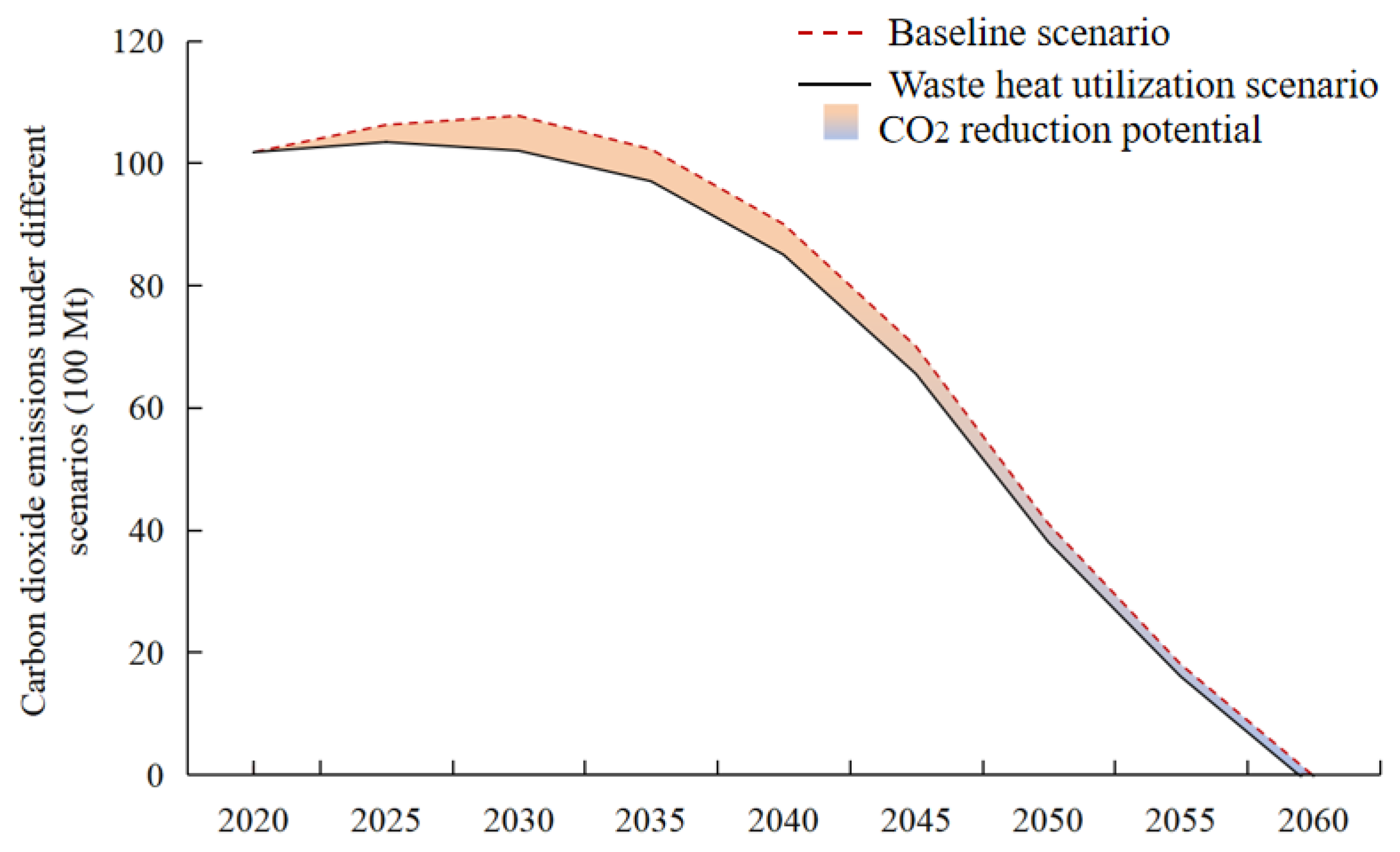

Figure 8 illustrates the development paths of carbon emissions under various scenarios. The red dashed line represents the carbon emission curve under the baseline scenario of carbon neutrality by 2060. The black solid line represents the development path of carbon emissions under the waste heat utilization scenario, and the vertical width of the shaded area reflects the emission reduction potential brought by the implementation of waste heat utilization measures. It is found that waste heat utilization has the greatest potential to reduce carbon emissions from 2025 to 2035, which can effectively lower the carbon emission peak and reduce the emission level during the plateau period.

Under the baseline scenario, China’s carbon emissions will exhibit a high-level peak characteristic, expected to occur around 2030 with a peak value of approximately 10,800 million tons (Mt) of CO2. Following the peak, emissions will exhibit a steady decline, approaching near-zero levels by 2060. Under the waste heat utilization scenario, the peak level will decrease significantly, advance the peak year to around 2028, and reduce peak emissions by 5.1% relative to the baseline scenario.

After 2035, there will be a relatively steep downward curve, and the goal of near-zero emissions will be achieved in 2058. As illustrated in the shaded area of

Figure 8, waste heat utilization exhibits the highest carbon abatement potential between 2025 and 2035, cutting emissions by more than 500 Mt. After 2035, the shaded area gradually shrinks, indicating a decline in the carbon abatement effectiveness of waste heat utilization.

Table 8 presents the carbon emissions trends and carbon reduction contribution of waste heat utilization technologies across different stages. In summary, waste heat utilization technologies hold substantial carbon abatement potential in the initial phase of carbon peaking. However, as clean energy replacement progresses, their marginal carbon abatement effect gradually declines. During the rising and peaking period, with the in-depth promotion of waste heat boiler transformation in industries such as iron and steel and cement, waste heat utilization has a carbon reduction potential of about 560 Mt. During the peak plateau period, industrial sectors still have a carbon reduction potential of about 480 Mt per year. In the accelerated emission reduction period, the breakthrough of medium and low-temperature waste heat utilization technologies becomes a key driving force for emission reduction, and the carbon reduction potential of industrial waste heat decreases to about 270 Mt per year. During the deep decarbonization period, the waste heat CCUS coupling system can utilize an important source of waste heat. However, as fossil energy consumption gradually decreases, the potential for reducing carbon through waste heat utilization steadily declines. At this point, large-scale clean energy integration becomes crucial for achieving carbon neutrality.

Figure 9 shows the changing trend of carbon reduction potential from waste heat utilization in various industries. During the interval between the carbon peaking and the subsequent peak plateau phases, the power generation, iron and steel, and non-metallic mineral industries contribute significantly to the carbon reduction potential, accounting for 125 Mt, 84 Mt, and 61 Mt, respectively, in the year 2035. The carbon reduction potential from waste heat utilization in other industries, such as papermaking, shows an upward trend, with an average annual growth rate of 1.6% from 2025 to 2035. In the medium and long term, as the consumption of fossil energy gradually decreases, the contribution of carbon reduction from waste heat in industries such as iron and steel, fuel processing, and non-metallic minerals shows a significant downward trend. The contribution of the chemical industry remains small throughout the period, accounting for only about 10 Mt. By the year 2060, the power generation and non-ferrous metal industries will have the largest proportion of carbon reduction potential from waste heat utilization, with a combined share of 50.5%.

5.4. Discussion of the Main Results

Overall, the NESAP simulation results are consistent with findings from the existing literature, demonstrating reliability both in replicating historical data and in delivering reasonable forecasts of development trends for the period 2025–2060. There is a significant positive correlation between the potential of waste heat utilization and the potential of carbon emission reduction [

37]. To quantify the carbon reduction effect of waste heat, a diagnostic regression analysis was performed using waste heat data and emission reduction outputs from the NESAP model. The results indicate that a 1% increase in waste heat utilization leads to a 1.08% rise in carbon emission reduction potential, as presented in

Table 9. It is important to clarify that the regression results reflect a correlation analysis derived from NESAP model output data rather than rigorous causal inference. Consequently, other control variables were not incorporated into the model. These results may change if the effects of other variables are taken into account.

Figure 10 illustrates the linearly fitted relationship between waste heat utilization potential and carbon emission reduction potential. The scatter points of different colors represent the waste heat utilization potential and carbon reduction potential values of different industries. The black solid line is the fitted regression line, and the gray shadow indicates the 95% confidence interval.

The high-potential cluster (6.5–8 on the horizontal axis) represents application scenarios with abundant waste heat resources and significant emission reduction effects, such as waste heat power generation in the iron and steel industry, fuel processing, and waste heat recovery in the power generation industry. This is consistent with the results of reference [

24]. Priority can be given to supporting technological upgrading in high-potential fields to reduce the peak of carbon emissions in 2030. The low-potential area (4.5–6.5 on the horizontal axis) corresponds to application scenarios with low waste heat utilization potential, such as the light industry with low-grade waste heat. Installing waste heat equipment may break the original process balance and offset the benefits of waste heat utilization. Industries in this category should prioritize upgrading and optimizing existing process flows. Meanwhile, they can explore green electricity replacement and green hydrogen coupling for deep decarbonization, so as to achieve energy conservation through process upgrading.

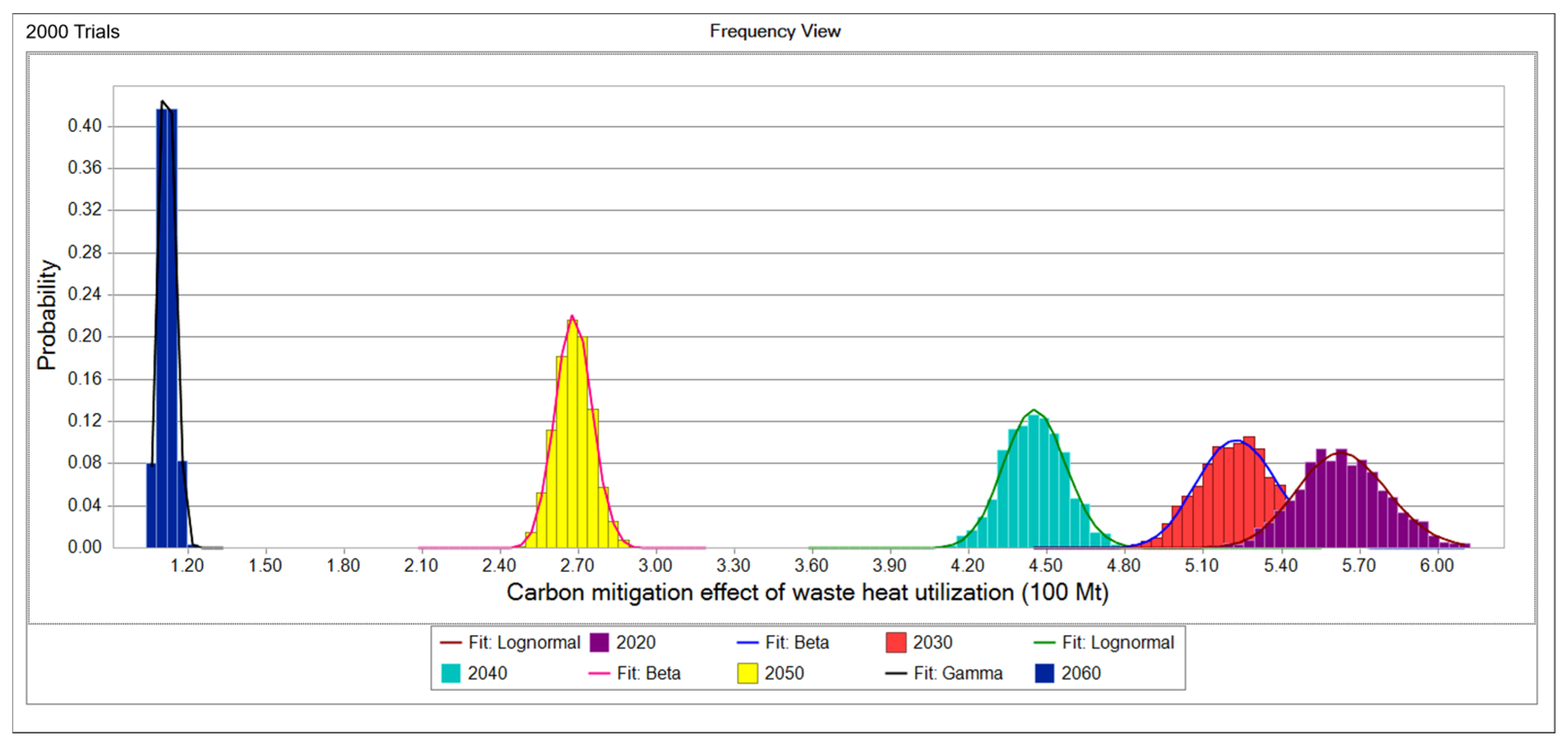

The carbon reduction effect of waste heat utilization exhibits a certain degree of uncertainty, which stems from different methods of parameter estimation. For instance, the uncertainty arises from variations in the selection of waste heat utilization parameters across different industries. This study employs the Monte Carlo method to conduct an uncertainty analysis of the carbon reduction effect of waste heat utilization. Specifically, the study first defines the prior probability distributions of input parameters using a triangular distribution. The triangular distribution describes the potential variation range of growth rates with three key parameters: minimum growth rate, maximum growth rate, and initially set growth rate. Samples are then drawn from these defined probability distributions. Based on the functional relationship between the input parameters and the variable to be estimated, the estimated values of the target variable are derived using the input samples. Finally, by fitting the probability distribution of these estimated values, the resulting distribution can be regarded as the probability distribution of the variable to be estimated.

The probability distributions of the carbon reduction effect of waste heat utilization are illustrated in

Figure 11. Herein, the horizontal axis represents the carbon reduction volume in each year under the waste heat utilization scenario, while the vertical axis denotes frequency and probability, respectively. It can be observed that as time progresses, the potential of waste heat utilization gradually diminishes, and the uncertainty becomes increasingly smaller. Specifically, the probability distribution of carbon reduction in 2020 exhibits a larger variance, whereas that in 2060 shows a smaller variance. Meanwhile, the variances of the probability distributions from 2020 to 2060 decrease sequentially. Furthermore, the interval between the carbon reduction probability distributions of different years indicates that the carbon reduction effect of waste heat utilization in China is gradually weakening.

We also examine which parameters’ uncertainties have a significant impact on the uncertainty of the carbon reduction effect of waste heat utilization. The sensitivity analysis results are shown in

Figure 12. The vertical axis represents the parameters influencing the carbon reduction effect. The horizontal axis denotes the contribution rate of each parameter’s uncertainty to the uncertainty of the carbon reduction volume achieved through waste heat utilization. It can be seen that the uncertainty in 2035 mainly stems from the energy emission factors, with a contribution rate of 26.1%. Other uncertainty sources include indicators such as waste heat utilization efficiency and waste heat grade.

For 2060, the uncertainty is primarily driven by the uncertainty of waste heat utilization efficiency, which has the highest contribution rate of 31.2%. Other sources of uncertainty include emission factors and GDP. It should be noted that energy structure optimization, especially the improvement of electrification level, will reduce the potential of waste heat utilization, thereby weakening the carbon reduction effect of waste heat. The results show that the energy structure reduces the carbon reduction effect by −3.4%.

Across all years, both waste heat utilization efficiency and energy emission factors are important sources of uncertainty regarding the carbon reduction effect of waste heat. This is because these two factors respectively determine the physical volume foundation and environmental value benchmark of carbon reduction, and both exhibit significant dynamic volatility and spatiotemporal heterogeneity. Specifically, waste heat utilization efficiency is not a constant value but is constrained by factors, such as heat exchange technology performance and heat loss during long-distance pipeline transmission. Its actual operating conditions often deviate from the design level and deteriorate due to equipment aging, leading to deviations in the accounting of the physical volume of substituted fossil energy. Meanwhile, energy emission factors depend not only on the carbon intensity fluctuations of the traditional energy being substituted, but also more sensitively on the power carbon emission factors driving the waste heat utilization system. This factor exhibits non-linear evolution with the clean energy transition of regional power grids and energy structure adjustments. The interaction between the instability of such technical parameters and the unpredictability of external energy policies means that even minor parameter perturbations will be significantly amplified in long-term cumulative calculations, thereby leading to high uncertainty in the assessment of carbon reduction effects.

6. Conclusions and Recommendations

6.1. Conclusions

The circular economy serves as a core component of China’s ecological civilization construction and will play an ever-growing role in fostering the development of green production modes. This study quantitatively calculates the waste heat utilization potential, temperature grades, and industrial distribution of China’s industrial sectors. The findings of this study indicate that:

The total waste heat potential in China demonstrates an overall inverted U-shaped trend. Industrial total waste heat potential is maximized during 2030–2035, thereby effectively reducing the peak level of energy consumption. Energy-intensive industries achieve an over 13% energy-saving rate, confirming the sustained benefits of waste heat utilization in industry. Notably, this practice is characterized by uneven development initially. Energy-intensive industries maintain an over 13% initial energy-saving rate.

Middle-grade waste heat holds the greatest potential, whereas high-grade and low-grade types account for smaller shares. High-grade waste heat is concentrated in the iron and steel, non-metallic mineral, and non-ferrous metal industries, and serves as a priority for recovery. Middle-grade waste heat predominates in industries such as power generation and fuel processing, acting as a core potential target for waste heat utilization. The low-grade waste heat is predominantly concentrated in industries such as the chemical and light industries, which collectively generate a substantial volume of such waste heat. However, its low energy density undermines the economic viability of recovery.

A significant positive correlation exists between the waste heat utilization and the carbon mitigation. Specifically, for each 1% increase in waste heat utilization, there is a corresponding 1.08% increase in carbon emission reduction. The power generation, iron and steel, and non-metallic mineral industries have been identified as significant contributors to the carbon reduction potential, with estimated contributions of 125 Mt, 84 Mt, and 61 Mt, respectively, by the year 2035. By the year 2060, the power generation and non-ferrous metal industries will have the largest proportion of carbon reduction potential from waste heat utilization, with a combined share of 50.5%.

However, there are some limitations in our research. First is the spatial scale constraint. The current study adopts a national-scale analysis framework, which does not fully account for the heterogeneity of regional energy structures, industrial layouts, and waste heat resource endowments in China. The second is technical uncertainty. Long-term projections of waste heat utilization potential are based on static assumptions about the iteration speed of low-carbon technologies. Actual technological progress may deviate from the preset scenarios. In future studies, we will expand the framework to regional-level analysis, integrating local industrial characteristics and resource endowments to optimize the spatial heterogeneity of the model. And we will introduce time-varying parameters for low-carbon technology iteration to enhance the rationality of long-term scenario simulations.

6.2. Recommendations

(1) Establish a technology promotion mechanism and promote the market-oriented application of high temperature waste heat utilization technologies. For industries with high imitation coefficients, build cross-regional waste heat utilization demonstration parks, and promote technology replication through benchmark projects. For industries with low diffusion indices, priority should be given to support the research and development of high-efficiency conversion technologies for low-grade waste heat, such as organic Rankine cycle systems, to break through economic bottlenecks.

(2) Phased deployment of waste heat utilization technologies to boost their contribution to the carbon peaking stage. During the carbon emissions growth-to-peak phase, guide high-emission industries to upgrade waste heat boilers. During the carbon peak plateau phase, gradually promote organic Rankine cycle power generation technology. For the deep decarbonization phase, deploy waste heat-green hydrogen coupling systems to enhance overall energy efficiency and emission reduction performance.

(3) Establish a cascaded and recycled utilization system for waste heat resources. Refine the whole-industry-chain incentive mechanism, and support cross-industry waste heat integration projects. Meanwhile, foster a cross-industry cascaded recycling system for waste heat, and advance an intensive, green, low-carbon, and cost-effective high-quality energy development model.