1. Introduction

The accelerated electrification of end-use sectors, the sustained growth of electricity demand, and the global commitment to decarbonization are driving distribution networks toward operating paradigms that are simultaneously more efficient, flexible, and resilient [

1,

2]. In this transition, the deployment of distributed energy resources (DER)—particularly photovoltaic (PV) units and wind turbines (WTs)—has become a key enabler of cleaner supply at the distribution level [

3,

4]. Nevertheless, the intermittency of renewable resources and the limited controllability of distribution feeders introduce operational challenges that are markedly different from those of transmission systems, including voltage deviations along radial paths, increased technical losses, and constraint violations under high penetration levels [

5,

6,

7].

In parallel, demand-side response (DSR) under real-time pricing (RTP) has emerged as a practical mechanism to reshape consumption profiles, mitigate peak loading, and improve the utilization of locally available renewable generation [

8,

9,

10]. From an operational standpoint, RTP-driven flexibility can reduce feeder currents during critical hours, thereby decreasing resistive losses and contributing to voltage regulation—particularly when coordinated with inverter-interfaced DER and distribution-oriented power-flow models.

For radial distribution feeders, the branch-flow (DistFlow) formulation provides a physically meaningful representation of voltage drops, line thermal constraints, and power balances [

11]. However, the resulting optimal power flow (OPF) planning problem remains highly nonlinear and nonconvex due to the coupling among nodal injections, voltages, and branch flows, as well as the presence of discrete and continuous decision variables associated with DER siting and sizing. Consequently, heuristic and metaheuristic optimization methods have been widely adopted to address the computational complexity and practical modeling requirements of distribution planning, including nature-inspired population-based strategies [

12].

Among these methods, the Whale Optimization Algorithm (WOA) has shown a competitive balance between exploration and exploitation [

12]. Several variants have been proposed to strengthen convergence, avoid premature stagnation, and improve feasibility handling through perturbation operators and penalty mechanisms [

13,

14,

15]. Despite this progress, three limitations are recurrent in recent DER planning studies: (i) the coordination of multiple DER types (PV and WT) with RTP-based DSR is often treated in a partially decoupled manner or evaluated under simplified demand flexibility assumptions; (ii) the feasibility of solutions is frequently reported without a systematic emphasis on constraint satisfaction under stochastic operating conditions; and (iii) comparative evidence against baseline operation (no DER/DSR) and against alternative optimizers is sometimes insufficient to attribute performance gains to the proposed algorithm rather than to DER penetration itself.

Motivated by these gaps, this work develops an integrated methodology to optimize active power supply in a radial distribution system through the coordinated siting and sizing of PV and WT units, jointly with an RTP-based DSR program. The formulation is built upon the DistFlow model to enforce operating constraints—including nodal voltage limits, conductor thermal capacities, and nodal power balances—while explicitly incorporating uncertainty in renewable resources, demand, and electricity prices through probabilistic modeling.

The main contributions of this work are summarized as follows:

A coordinated planning-and-operation framework that integrates PV, WT, and RTP-driven DSR within a unified DistFlow-constrained optimization model.

An improved whale-based metaheuristic (I-WaOA) that enhances the classical WOA by combining diversification and feasibility-oriented penalty handling (Cauchy mutation, FDB, and QOBL mechanisms), targeting robust convergence to admissible solutions.

A stochastic scenario-based assessment that captures uncertainty in irradiance, wind speed, ambient temperature, demand, and prices, enabling realistic evaluation of technical and economic indices.

The remainder of this paper is organized as follows:

Section 2 reviews recent literature on DER siting/sizing, demand response under RTP, and metaheuristic-based optimization for distribution networks, and it positions the present contributions with respect to open challenges.

Section 3 presents the proposed formulation, including objective function, constraints, uncertainty modeling, and the I-WaOA optimization procedure.

Section 4 describes the IEEE 118-bus case study and operating scenarios. The obtained results are presented and analyzed in the subsequent section, while the Discussion and Conclusions sections synthesize the main findings and directions for future work.

2. Literature Review

Recent research on distribution network optimization has largely focused on the optimal siting and sizing of DER to reduce losses and improve voltage profiles, frequently employing metaheuristic optimizers to handle nonconvexity and mixed decision variables. This section summarizes representative trends in (i) PV/WT allocation strategies, (ii) demand response under RTP, and (iii) metaheuristic-based solution methods, and it highlights the specific research gaps addressed in this work.

2.1. PV/WT Siting and Sizing in Distribution Networks

DER allocation studies commonly target feeder loss minimization and voltage regulation by placing generation close to load centers and electrically weak buses. Early formulations and distribution-oriented constraints are often modeled through branch-flow representations [

10,

11]. More recent works incorporate uncertainty in PV output and network operating conditions, typically via scenario-based or probabilistic approaches, to improve realism in planning decisions [

5]. Comparative studies have also reported that different metaheuristics may yield markedly different trade-offs in solution quality, computational cost, and feasibility handling for DG allocation problems [

14,

16].

2.2. Demand Response and Real-Time Pricing

Demand response under RTP provides an additional degree of freedom to reshape net load and reduce operating costs. Surveys on DSR emphasize that price-driven demand flexibility can alleviate peak demand and support more efficient system operation when consumers respond to time-varying prices [

8,

9]. However, many DER planning studies still treat demand as exogenous or incorporate simplified flexibility models, which may limit the assessment of coordinated operation between renewable injections and load adaptation.

2.3. Metaheuristic Optimization for DistFlow-Constrained Planning

Metaheuristic algorithms are widely adopted for distribution planning due to their ability to search complex nonconvex spaces without requiring strong convexity assumptions. The Whale Optimization Algorithm (WOA) is a representative population-based method that has been applied to power-system optimization due to its exploration–exploitation balance [

12]. Several improved variants have been reported, including mechanisms such as adaptive perturbations and penalty-based feasibility strategies [

13,

14,

15]. Nevertheless, two methodological issues remain critical in practice: (i) ensuring strict constraint satisfaction (voltage bounds and thermal limits) under stochastic operating conditions, and (ii) providing comparative evidence against baseline operation and against alternative optimizers to isolate the benefit of the proposed algorithmic enhancements.

2.4. Identified Research Gaps and Scope of This Work

Based on the above, the main gaps motivating this study are summarized as follows:

Coordination gap: PV, WT, and RTP-based DSR are frequently studied separately or under partially coupled models, limiting the evaluation of coordinated operational benefits.

Feasibility under uncertainty: The stochastic nature of renewable resources and demand can lead to constraint violations if feasibility is not explicitly enforced across scenarios.

Attribution of performance gains: Without baseline and optimizer-to-optimizer comparisons, improvements may be mistakenly attributed to the metaheuristic rather than to DER penetration itself.

To address these gaps, the proposed framework integrates PV, WT, and RTP-driven DSR within a DistFlow-constrained formulation, and it employs an improved whale-based optimizer (I-WaOA) equipped with diversification operators and penalty-based feasibility handling. The resulting methodology is designed to quantify both technical and economic impacts under uncertainty while preserving operational admissibility.

3. Materials and Methods

This section presents, with full methodological detail, the proposed framework to optimize active power supply in a large-scale radial distribution system by coordinating (i) the siting and sizing of photovoltaic (PV) and wind turbine (WT) distributed generation and (ii) a real-time pricing (RTP)-based demand-side response (DSR) program. The methodology couples a distribution-oriented power-flow model (DistFlow) with a constrained multiobjective optimization solved by an Improved Whale Optimization Algorithm (I-WaOA). The formulation explicitly accounts for uncertainty in renewable resources, demand, and price through probabilistic modeling and scenario reduction.

3.1. Methodological Workflow

Figure 1 summarizes the full sequence of the proposed procedure: data acquisition (climate, demand, prices, network parameters), preliminary feasibility screening (hosting capacity and critical buses), candidate-node selection using Fitness–Distance Balance (FDB), detailed PV/WT and inverter modeling, stochastic scenario generation and reduction, and finally, the constrained optimization loop using I-WaOA with DistFlow-based power-flow evaluation.

3.2. Sets, Indices, Parameters, and Decision Variables

Let be the set of buses, with , and the set of directed branches consistent with the radial orientation from the slack/root bus toward downstream buses. The hourly index is .

3.2.1. Network Parameters

For each line : [] and [] are resistance and reactance, respectively; [kVA] is the branch thermal limit. For each bus : and [p.u.] are the admissible voltage bounds.

3.2.2. Exogenous Profiles

[W/m2] denotes solar irradiance, [m/s] wind speed, and [°C] ambient temperature. [kW] is the baseline (non-responsive) demand at bus i, and [$/kWh] is the RTP electricity price.

3.2.3. Decision Variables (Planning/Operation)

The optimization determines the following:

[kW]: rated PV capacity installed at bus i;

[kW]: rated WT capacity installed at bus i;

[–]: price elasticity coefficient for DSR at bus i (zero for non-participating loads);

[kW], [kVAr]: active/reactive power exchanged with the grid at the slack bus;

[p.u.]: voltage magnitude at bus i;

[kW], [kVAr]: branch active/reactive flows for each line .

The operational variables are computed implicitly by solving the DistFlow equations for every candidate solution proposed by the optimizer.

3.3. Objective Function (Multiobjective Formulation)

The optimization seeks to simultaneously reduce annual operating costs, technical losses, and voltage deviations. The scalarized objective function is

where

are weighting coefficients (dimensionless);

[

$] is the annual cost;

[kWh/year] is the annual energy loss; and

[p.u.] aggregates voltage deviation.

3.3.1. Annual Energy Cost

The annual cost includes energy purchased from the grid, the monetized cost of losses, and annualized DER investment and O&M:

where

[kW] is the grid active power at hour

h,

[

$/kWh] is the RTP price,

[

$/kWh] is the unit cost assigned to feeder losses, and

[kW] is the total active loss at hour

h.

3.3.2. Annual Loss Energy

The annual energy loss is

where

h.

3.3.3. Voltage Deviation Term

The aggregated voltage deviation is

where

[p.u.] is the voltage magnitude at bus

i during hour

h and the nominal reference is 1 p.u.

3.3.4. Investment and O&M Costs

The annualized installation cost is computed using the capital recovery factor (CRF):

where

[–] is the annual interest rate,

[years] is the planning horizon,

[

$/kW] is the unit installation cost, and

[kW] is the rated power for PV/WT.

3.4. Operating Constraints

All candidate solutions must satisfy network operational constraints for every hour h.

3.4.1. Voltage Limits

where

and

define the admissible voltage band (p.u.).

3.4.2. Thermal Limits

where

[kW] and

[kVAr] are branch power flows and

[kVA] is the branch capacity.

3.4.3. Power Balance (System-Wide)

At each hour

h, the overall active-power balance is

where

[kW] is the responsive demand,

and

[kW] are DER injections at bus

i, and

[kW] is the total loss.

3.4.4. Nonnegative Grid Import

ensuring the slack bus represents grid purchase in this formulation.

3.4.5. Inverter Capability (Volt/VAR Feasibility)

For inverter-interfaced DER at bus

i, reactive power is bounded by apparent power:

where

[kVA] is inverter apparent-power rating,

[kW] is injected active power, and

[kVAr] is reactive injection.

3.5. Radial Power-Flow Model (DistFlow) and Load-Flow Computation

The radial load flow is modeled using the branch-flow (DistFlow) equations [

10,

11]. For each branch

and hour

h:

Here,

denotes the set of children (downstream) buses connected to bus

j in the radial orientation.

and

represent net generation injections at bus

j (including PV/WT and inverter reactive power support), while

is reactive demand.

Load-Flow Computation Procedure

For every candidate solution proposed by I-WaOA, the load flow is evaluated hour-by-hour as follows:

Construct the net injections at each bus

j:

where

is selected within (

14) to support voltages (if enabled).

Solve (

15)–(

17) along the radial ordering using a sequential sweep procedure (forward evaluation of branch flows and recursive update of voltages) until the maximum voltage mismatch satisfies a tolerance

(e.g.,

p.u.).

Compute losses at hour

h as

where each term is the resistive loss of branch

.

This DistFlow-based load-flow procedure provides

,

,

, and

required to evaluate (

1) and enforce constraints (

10)–(

11).

3.6. Phase 1: System Analysis and Hosting Capacity Screening

A feasibility screening step is conducted prior to optimization to identify electrically critical regions and determine a hosting-capacity envelope for DER integration.

3.6.1. Hosting Capacity Definition

The renewable integration limit (hosting capacity) is defined as the maximum aggregate DER capacity that can be accommodated without violating voltage constraints (

10) and thermal limits (

11) over the considered operating conditions. In practice, candidate DER injections are increased progressively (or via a bisection search) and the first occurrence of a constraint violation defines the admissible upper bound. The resulting envelope constrains the search space of PV/WT capacities, improving feasibility and convergence.

3.6.2. Critical-Bus Identification

Buses are ranked based on voltage sensitivity and loading indicators derived from the base-case DistFlow solution (without DER). The set of highly sensitive buses is retained to prioritize candidate placement regions and to reduce the combinatorial complexity of the siting problem.

3.7. Phase 2: Candidate Bus Selection Using Fitness–Distance Balance (FDB)

Candidate buses for PV/WT integration are selected using the Fitness–Distance Balance (FDB) criterion, which promotes a trade-off between solution quality (fitness) and population diversity (distance to current best).

The Euclidean distance between solution

i and the best solution in the decision space is

where

is the

d-th decision component of solution

i,

is the corresponding component of the best-known solution, and

n is the decision-space dimension.

Normalized distance and normalized fitness are computed as

where

is the objective value of solution

i.

Finally, the FDB score is

where

is a time-varying coefficient,

t is the iteration counter, and

is the maximum number of iterations. This scoring favors exploration early (larger emphasis on distance) and exploitation later (larger emphasis on fitness), producing a robust candidate set for PV/WT siting.

3.8. Phase 3: Renewable Generation Models (PV and WT)

3.8.1. PV Generation Model

The instantaneous PV power is

where

[m

2] is the panel area,

[W/m

2] is irradiance, and

is the conversion efficiency.

Efficiency is modeled as

where

[–] is rated efficiency,

[1/°C] is the temperature coefficient,

[°C] is the reference temperature, and

[°C] is the cell temperature.

Cell temperature is approximated via a NOCT-type model:

where

[°C] is ambient temperature and

[°C] is the nominal operating cell temperature parameter.

3.8.2. WT Generation Model

WT output follows the standard piecewise characteristic curve:

where

v [m/s] is wind speed,

[m/s] is cut-in speed,

[m/s] is rated speed,

[m/s] is cut-out speed, and

[kW] is rated WT power.

3.9. Phase 3 (Continued): Demand-Side Response Under RTP

Demand response is represented through a price-elasticity model that updates the baseline demand according to RTP signals. For each participating bus

i:

where

[kW] is the baseline demand,

[kW] is the responsive demand,

[–] is the elasticity,

[

$/kWh] is the hourly price, and

is the daily mean price.

To avoid unrealistic demand reductions, a participation and admissibility rule is enforced:

where

and

[kW] represent minimum and maximum feasible demand given user comfort/operational limits. Non-participating buses are modeled by setting

.

3.10. Demand-Side Response Modeling Under Real-Time Pricing

Demand-side response (DSR) is modeled through a price-elastic demand formulation that captures the ability of a subset of consumers to adapt their electricity consumption in response to real-time price (RTP) signals. The adopted model represents a compromise between behavioral realism and computational tractability, which is suitable for large-scale distribution network optimization.

Let

denote the baseline (inelastic) active power demand at bus

i and hour

h, obtained from historical or forecasted load profiles. Under RTP, the responsive demand

is expressed as

where

[

$/kWh] is the hourly electricity price,

is a reference price (e.g., daily average), and

is the price elasticity coefficient associated with the flexible portion of the load at bus

i.

Only a fraction of the total demand is assumed to be price-responsive. This is modeled by assigning a nonzero elasticity coefficient to selected buses representing residential and commercial consumers with flexible loads, while the remaining buses are modeled as inelastic (). In this study, the proportion of flexible demand is assumed to be moderate, reflecting realistic participation levels reported in demand response programs, and ensuring that load reductions remain within physically and socially acceptable bounds.

To prevent unrealistic demand curtailment, the responsive load is bounded as

where

represents the maximum admissible relative variation of demand due to DSR. This constraint ensures that RTP induces demand shifting or partial curtailment rather than full load interruption.

The DSR-adjusted demand profiles are incorporated directly into the DistFlow power-balance equations and into the objective function through the energy purchase cost, enabling the optimization algorithm to exploit demand flexibility in coordination with PV/WT generation and network constraints.

3.11. Probabilistic Uncertainty Modeling and Scenario Construction

Uncertain variables are modeled probabilistically. Normalized irradiance

is represented by a Beta distribution:

where

and

are Beta parameters and

is the Beta function.

Wind speed is modeled using a Weibull distribution:

where

k [–] is the shape parameter and

c [m/s] is the scale parameter [

17].

Temperature, demand, and prices are modeled using normal distributions:

where

and

are mean and standard deviation.

Scenario Generation and Reduction

A Monte Carlo procedure generates a large set of stochastic daily scenarios by sampling from (

31)–(

33) and computing PV/WT power and responsive demands. The initial scenario set is then reduced to a smaller representative subset using stochastic scenario reduction, preserving the main statistical characteristics while decreasing computational complexity. The reduced scenario set is used within the optimization loop.

3.12. Phase 4: Optimization via Improved Whale Optimization Algorithm (I-WaOA)

The constrained optimization problem is solved using I-WaOA, which enhances the original Whale Optimization Algorithm (WOA) by incorporating (i) Cauchy mutation for escaping local optima, (ii) Fitness–Distance Balance (FDB) for diversity preservation, and (iii) quasi-oppositional-based learning (QOBL) for faster global convergence.

3.12.1. WOA Core Update Mechanisms

Let denote the position (candidate solution) of whale i at iteration t, where n is the number of decision variables. The best solution found so far is .

WOA updates positions using the encircling and bubble-net strategies. The coefficient vectors are

where

a decreases linearly from 2 to 0 over iterations, and

is a random vector.

The distance to the best solution is

where ⊙ is elementwise multiplication.

The spiral (bubble-net) update is

where

,

b is a constant controlling spiral shape, and

.

A probability

selects between (

36) and (

37).

3.12.2. I-WaOA Enhancements

To increase exploration and escape stagnation, CM perturbs solutions as

where

is a scaling factor and

is a vector of i.i.d. Cauchy random variables.

FDB scores in (

22) are used to rank candidate solutions and to select promising individuals that simultaneously exhibit good fitness and adequate diversity.

Given a variable bound

, the opposite point is

and the quasi-opposite point is generated around the midpoint to accelerate convergence [

18]. QOBL candidates are evaluated and accepted if they improve fitness while maintaining feasibility.

3.12.3. Constraint Handling via Penalty Function

Operational constraints are enforced using a quadratic penalty:

where

is the original objective (

1),

denotes the

r-th inequality constraint (e.g., voltage or thermal violation), and

is a penalty coefficient. This strategy guides the search toward feasible regions without requiring explicit repair operators.

3.12.4. Algorithmic Procedure (Pseudo-Code in Text)

The optimization loop proceeds as follows:

Initialize a population within variable bounds (PV/WT capacities, candidate buses, DSR elasticity parameters).

For each whale , and for each scenario and hour h:

Compute

and

using (

23)–(

26);

Compute responsive demands using (

27)–(

30);

Solve DistFlow (

15)–(

17) and compute losses (

18).

Evaluate the penalized fitness

using (

1) and (

39); update

.

Update whale positions using WOA rules (

36)–(

37).

Apply I-WaOA operators: CM (

38), FDB ranking (

22), and QOBL generation and selection.

Repeat until ; return (optimal siting/sizing and DSR parameters).

3.13. Performance Indices

3.13.1. Voltage Deviation (VD)

Voltage deviation is used as a global voltage-quality indicator:

where

[p.u.] is the voltage magnitude at bus

i and hour

h, and 1 p.u. is the nominal reference.

3.13.2. Fast Voltage Stability Index (FVSI)

To assess proximity to voltage instability, a line-based voltage stability index is adopted. For each branch

and hour

h, the FVSI is defined as [

19]

where

[p.u.] is the sending-end voltage magnitude of branch

,

[kVAr] is the reactive power demand at the receiving bus

j (or the net reactive requirement seen at bus

j),

[p.u.] is the series reactance of branch

, and

with

and

being the branch resistance and reactance, respectively.

3.13.3. Interpretation

A value of

close to 1 indicates that the branch is approaching its voltage-instability limit, whereas

denotes operation within the stable region [

19]. In this work, the network-wide stability level is summarized by the maximum value across all branches and hours:

which provides a conservative indicator of the closest operating condition to voltage collapse.

3.14. Computational Implementation

The complete methodology was implemented in Python 3.12. For each candidate solution in I-WaOA, a DistFlow-based load flow is computed for each hour and scenario, enabling the evaluation of objective terms (cost, losses, voltage deviation) and constraint enforcement (voltage and thermal limits). Climate data were obtained from IRENA Global Atlas and INAMHI, while the validation relies on technical indices (, losses, stability measures) and economic indices (annual cost components).

4. Case Study: Radial Network Derived from the IEEE 118-Bus Test Case

This work adopts as case study a radial, distribution-like network derived from the well-known IEEE 118-bus power-flow test case, which was originally introduced as a transmission-level benchmark [

20,

21,

22]. The IEEE 118-bus dataset is widely used due to its rich set of buses, loads, generators, and branches, enabling stress-testing of optimization algorithms under large-scale conditions.

Since the proposed formulation relies on a radial DistFlow model, the original meshed transmission topology is transformed into a radial configuration through an explicit derivation procedure described next. This approach preserves the nodal load allocation and electrical parameters as a base reference while producing a strictly radial feeder suitable for DistFlow-based optimization. The resulting system is therefore interpreted as a radialized IEEE-118 variant intended for methodological validation rather than as a literal representation of a real distribution feeder.

4.1. Derivation of the Radial IEEE-118 Variant

The original IEEE 118-bus benchmark is a transmission test case with a partially meshed topology [

20,

21,

22]. To ensure compatibility with the radial DistFlow model used in this manuscript, the network is converted into a strictly radial structure using the following steps:

Graph representation: The system is modeled as a graph , where buses are nodes and branches/transformers are edges. The slack bus is selected as the root node.

Radial spanning structure: A radial backbone is obtained by extracting a spanning tree that connects all buses without cycles. In this work, the spanning structure is chosen to prioritize electrically strong connections, i.e., branches with lower series impedance magnitude , which tends to reduce excessive voltage drops in long radial paths.

Parameter inheritance: For each retained branch , the original series parameters and branch limits are inherited from the IEEE 118-bus data source. Bus load allocations are preserved, and the slack bus balances the system power mismatch.

Radial orientation: The radial network is oriented from the slack/root bus toward downstream buses, defining parent–child relationships required by the DistFlow recursion.

Feasibility screening: After radialization, a base-case DistFlow solution (without DER and without DSR) is computed to verify that voltages and branch loadings remain within admissible limits. If violations occur, the spanning structure is adjusted by replacing critical branches with alternative edges from to reduce electrical stress.

This radialization produces a reproducible benchmark suitable for DistFlow-based optimization. Nevertheless, because it is derived from a transmission test case, it should be interpreted as a large-scale radial benchmark for algorithmic validation rather than as a standard distribution feeder model.

4.2. IEEE 118-Bus Distribution Network Model

Figure 2 shows the schematic single-line diagram of the IEEE 118-bus distribution system used in the simulations. In this model, the following elements are identified:

A reference (slack) bus responsible for maintaining the voltage reference and compensating system power imbalances.

Pure load buses, where industrial, commercial, and residential loads are spatially distributed across the network.

Distributed generation buses, where the photovoltaic and wind units considered in this study are located.

Distribution lines that connect buses in an extended radial structure, with series parameters associated with each line segment between buses k and m.

The network model includes the usual operating constraints of distribution systems:

Nodal voltage limits:

where

is the voltage at bus

i, and

and

define the admissible operating band (e.g.,

–

p.u.).

Line current limits:

where

is the current in line

ℓ and

is its thermal capacity.

Active and reactive power balance at each bus:

where

and

represent the active and reactive power flows toward adjacent buses

.

4.3. Siting and Sizing of Renewable Resources

In this study, a total installed renewable generation capacity of is considered, representing approximately of the system peak demand of . This penetration level makes it possible to evaluate the impact of renewable distributed generation on the voltage profile, active power losses, and network stability without compromising operating security.

The renewable capacity is allocated as follows:

Photovoltaic generation (PV): installed at buses 7, 14, and 30.

Wind generation (WT): installed at buses 9 and 24.

These buses were selected based on technical and operational criteria:

Proximity to load centers: Buses with significant demand were prioritized so that local generation reduces power flows from the main bus and, consequently, line losses.

Low equivalent impedance: Buses with low-impedance electrical paths to the rest of the network were chosen, improving voltage support and preventing localized overloads.

Feasibility for renewable integration: Favorable irradiance and wind-speed conditions were assumed in the areas associated with the selected buses, compatible with installing medium-scale PV plants and wind turbines.

The rated power of each unit is defined so that the sum of capacities at the selected buses reaches for PV and for WT. The contribution of these units is modeled under the following general assumptions:

PV units operate under maximum power point tracking (MPPT), such that the injected active power depends on solar irradiance and cell temperature for each hour t of the operating horizon.

WT units are modeled using characteristic power curves as a function of wind speed , considering cut-in speed, rated speed, and cut-out speed, according to typical commercial specifications.

4.4. Demand Response Program

In addition to renewable generation integration, the case study incorporates a demand-side response (DSR) program based on real-time pricing (RTP). Under this scheme, certain users participate by modifying their consumption profiles according to the hourly electricity price signal, which makes it possible to

Flatten the demand curve during peak hours, reducing the need for power from the slack bus;

Improve the voltage profile at remote buses by lowering flows in the most heavily loaded line segments;

Reduce active power losses in the lines and improve the network stability index.

In this work, the detailed implementation of DSR and its impact on demand profiles and optimal network operation are analyzed later in the Results and Discussion section. At the case-study definition stage, the DSR program is represented by

A demand elasticity function with respect to price, which allows shifting or partially curtailing consumption in specific hourly blocks;

A set of flexible loads selected at specific buses, to which consumption modifications are applied in the presence of high price signals.

4.5. Case-Study Summary

Table 1 summarizes the main parameters considered in the case study for the IEEE 118-bus system, the integrated renewable generation, and the demand response program. This configuration provides the basis for applying the optimization algorithm proposed in

Section 3 and for evaluating, in the Results and Discussion section, the benefits in terms of cost reduction, voltage-profile improvement, and active power loss mitigation.

5. Results and Discussion

This section presents the results obtained after applying the proposed optimization framework based on the Improved Whale Optimization Algorithm (I-WaOA) to the radialized IEEE 118-bus benchmark. The analysis considers the coordinated integration of photovoltaic (PV) generation, wind turbine (WT) generation, and a real-time pricing (RTP)-based demand-side response (DSR) program under DistFlow operating constraints. The reported results are structured to provide a transparent and systematic assessment of the impact of coordinated optimization on system operation.

5.1. Comparative Scenarios and Baseline Definition

To objectively evaluate the effectiveness of the proposed methodology, all results are interpreted through a comparative analysis between two reference operating configurations:

Baseline scenario (B0): operation of the radialized IEEE 118-bus network without distributed renewable generation and without demand-side response. In this reference case, the entire system demand is supplied by the slack (grid) bus, and no optimization-based siting or sizing decisions are applied.

Optimized scenario (B1): coordinated integration of PV and WT units together with the RTP-based DSR program, where the siting and sizing of renewable resources and the resulting operating conditions are optimized using the proposed I-WaOA under DistFlow constraints and inverter capability limits.

This baseline-to-optimized comparison enables distinguishing the technical and operational benefits arising from coordinated DER and demand flexibility integration, rather than attributing all observed improvements solely to renewable penetration.

5.2. Scenario Generation and Reduction

Uncertainty in solar irradiance, wind speed, ambient temperature, load demand, and electricity prices is represented through probabilistic models and propagated using a scenario-based framework. An initial ensemble of 800 Monte Carlo scenarios was generated by random sampling of the corresponding probability distributions and computing the associated PV/WT generation and DSR realizations.

To ensure computational tractability while preserving the statistical characteristics of the uncertainty space, the original scenario set was reduced to 12 representative scenarios using stochastic reduction techniques. The reduced set retains the dominant variability patterns of renewable production, demand response, and price signals, and it is consistently used throughout the subsequent analyses to evaluate system performance under realistic operating variability.

5.3. Stochastic Distributions of Operating Parameters

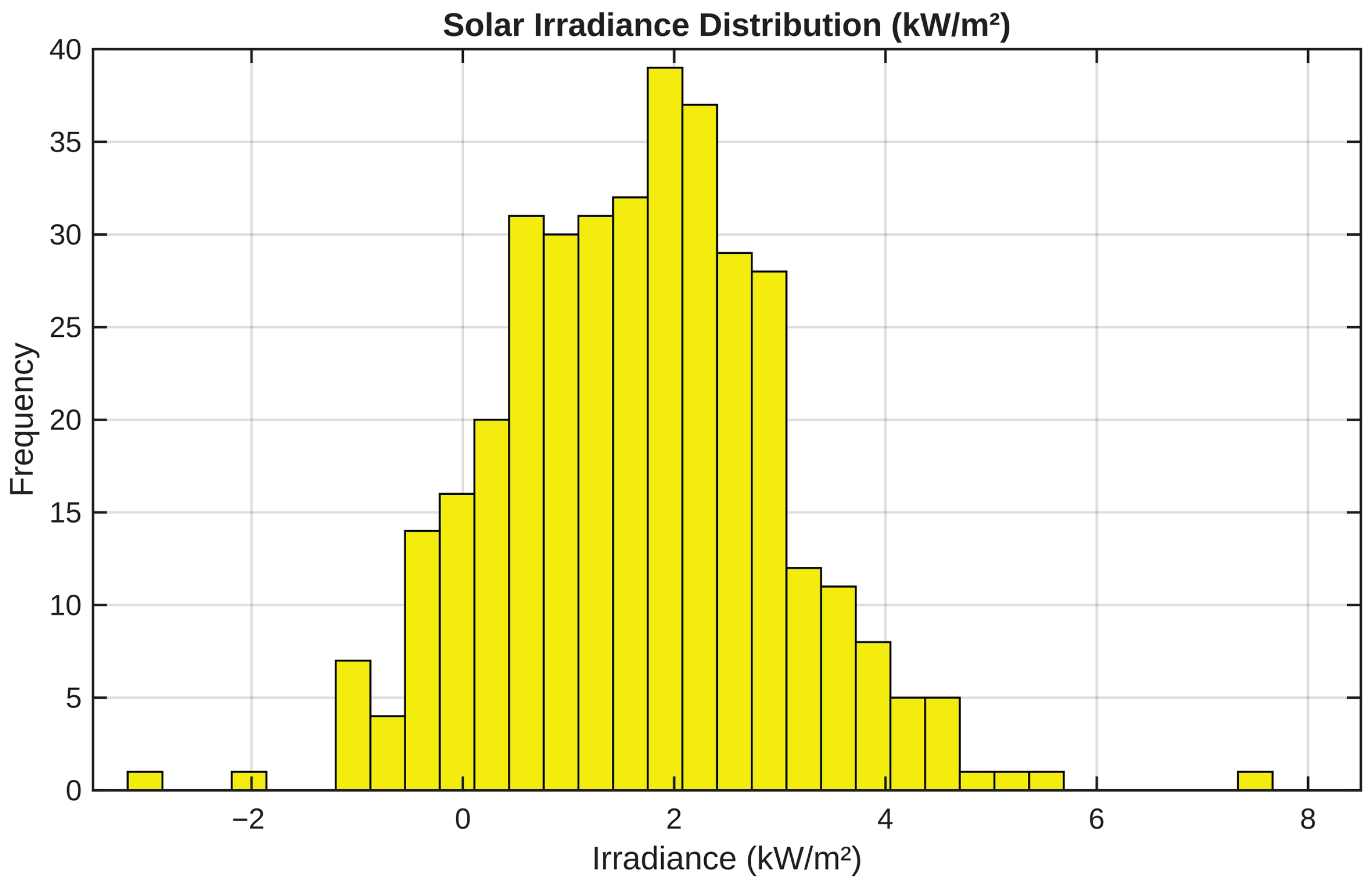

5.3.1. Solar Irradiance Distribution

Figure 3 shows the solar irradiance distribution used for modeling photovoltaic generation. A Beta function was employed due to its suitability for representing bounded variables between 0 and 1. The observed variability enables capturing realistic radiation conditions typical of Andean climates.

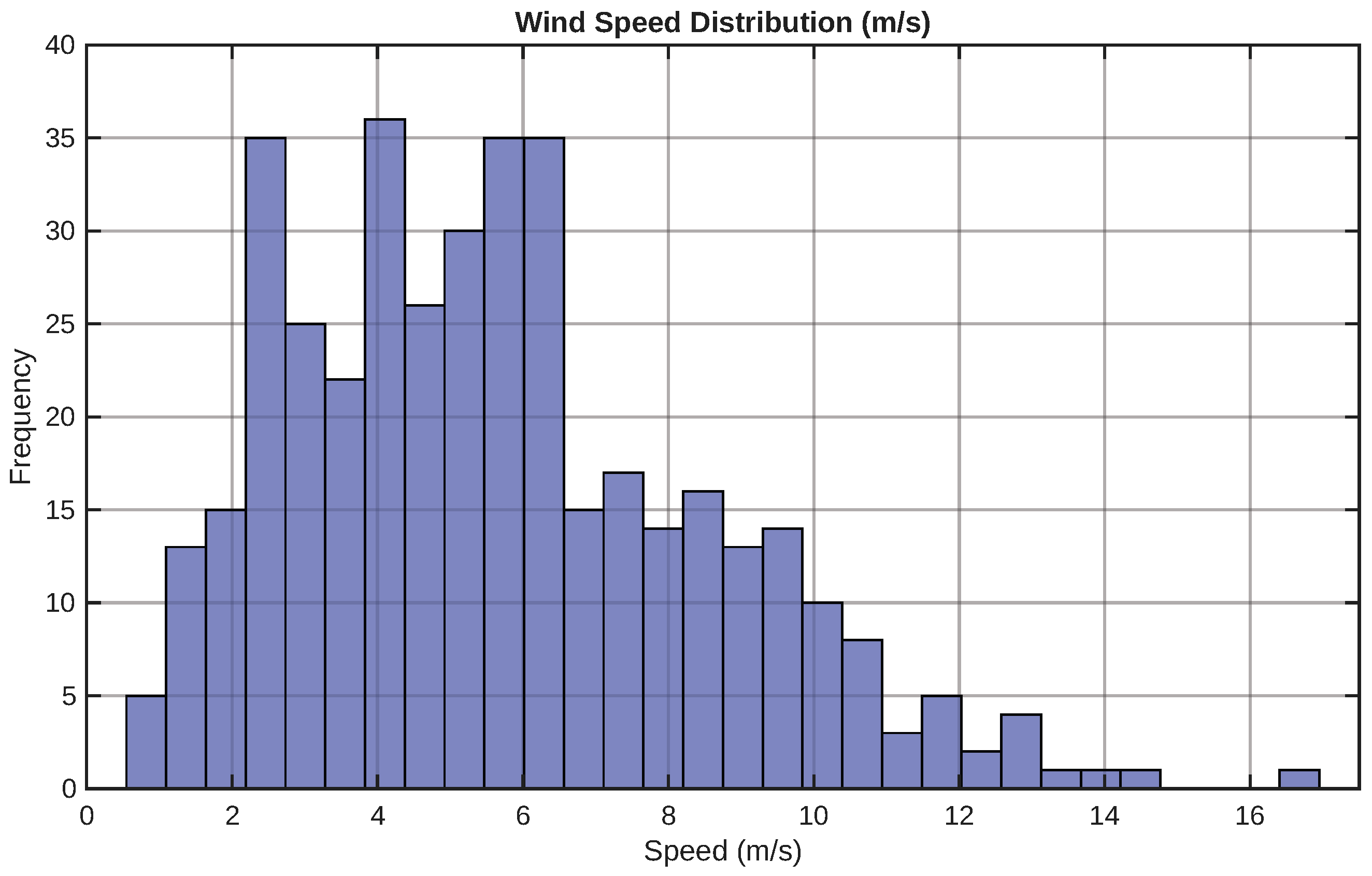

5.3.2. Wind Speed Distribution

Figure 4 presents the Weibull distribution used to model wind speed at the locations assigned to wind generators. The distribution shows typical values between 4 and 7 m/s, suitable for medium-capacity turbines installed in peripheral urban areas.

5.3.3. Load Demand Distribution

Figure 5 shows the normal distribution associated with system demand. It exhibits a daily variation ranging from 1.6 MW to 3.2 MW, concentrated around a mean value of 2.4 MW.

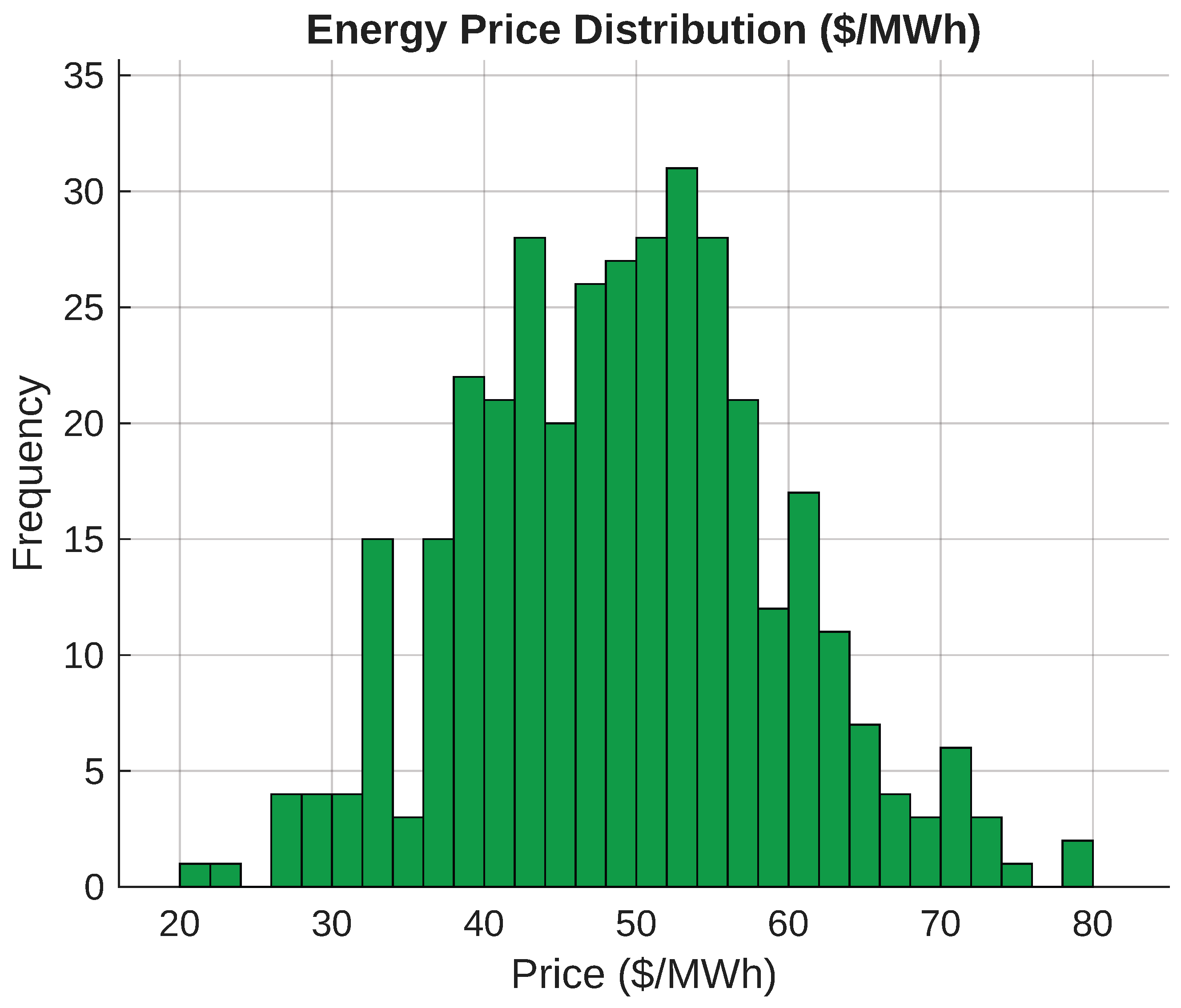

5.3.4. Electricity Price Distribution

Figure 6 presents the normal distribution used for hourly marginal prices. This distribution is key to the behavior of the demand-side response (DSR) program.

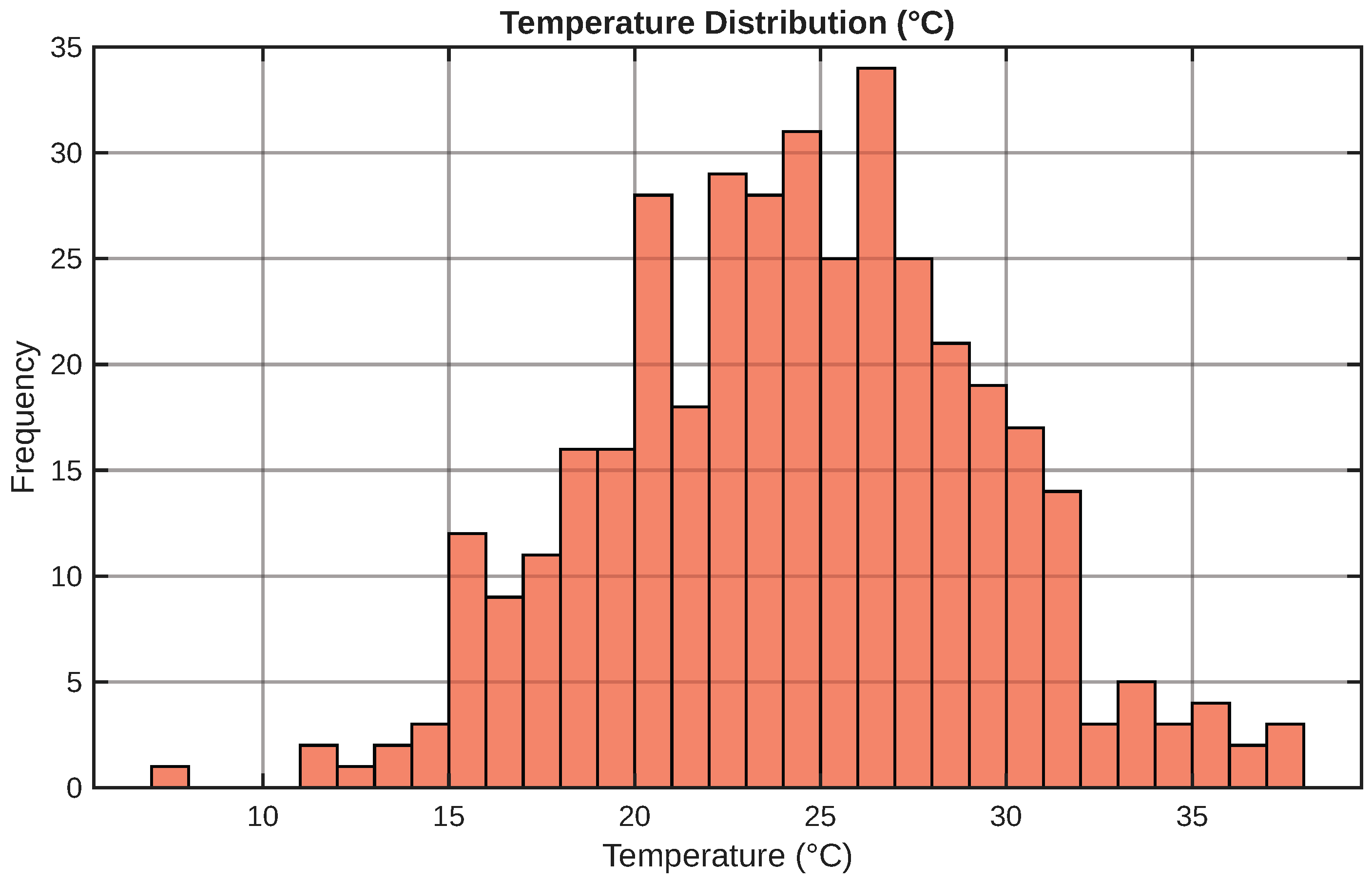

5.3.5. Temperature Distribution

Figure 7 corresponds to the normal distribution employed in the thermal modeling of photovoltaic panels, which directly affects their instantaneous efficiency.

5.4. Renewable Generation Results

5.4.1. Generated Photovoltaic Power

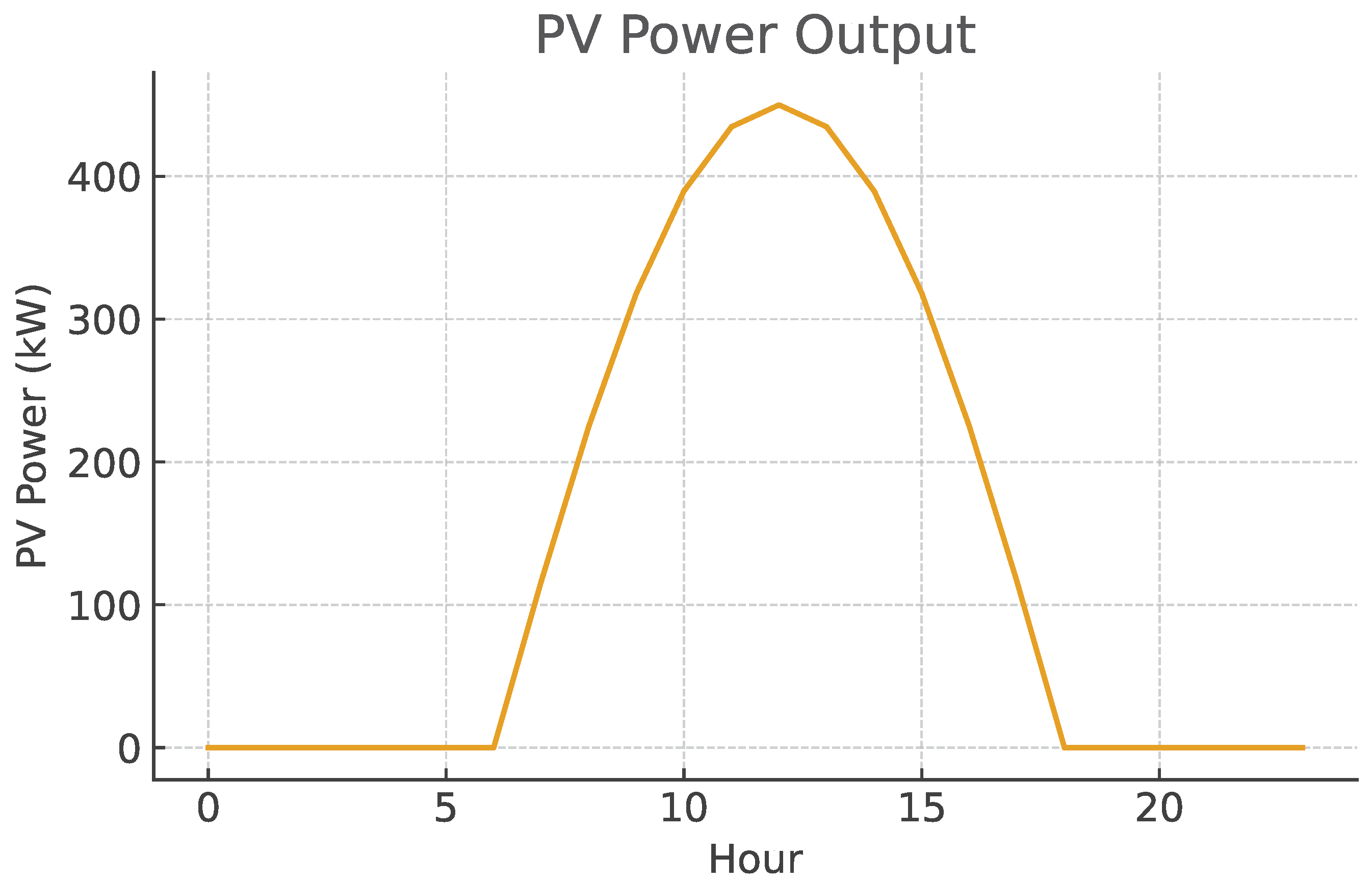

Figure 8 presents the PV power generated from irradiance and temperature. A peak near midday is observed, with variations consistent with stochastic conditions.

5.4.2. Generated Wind Power

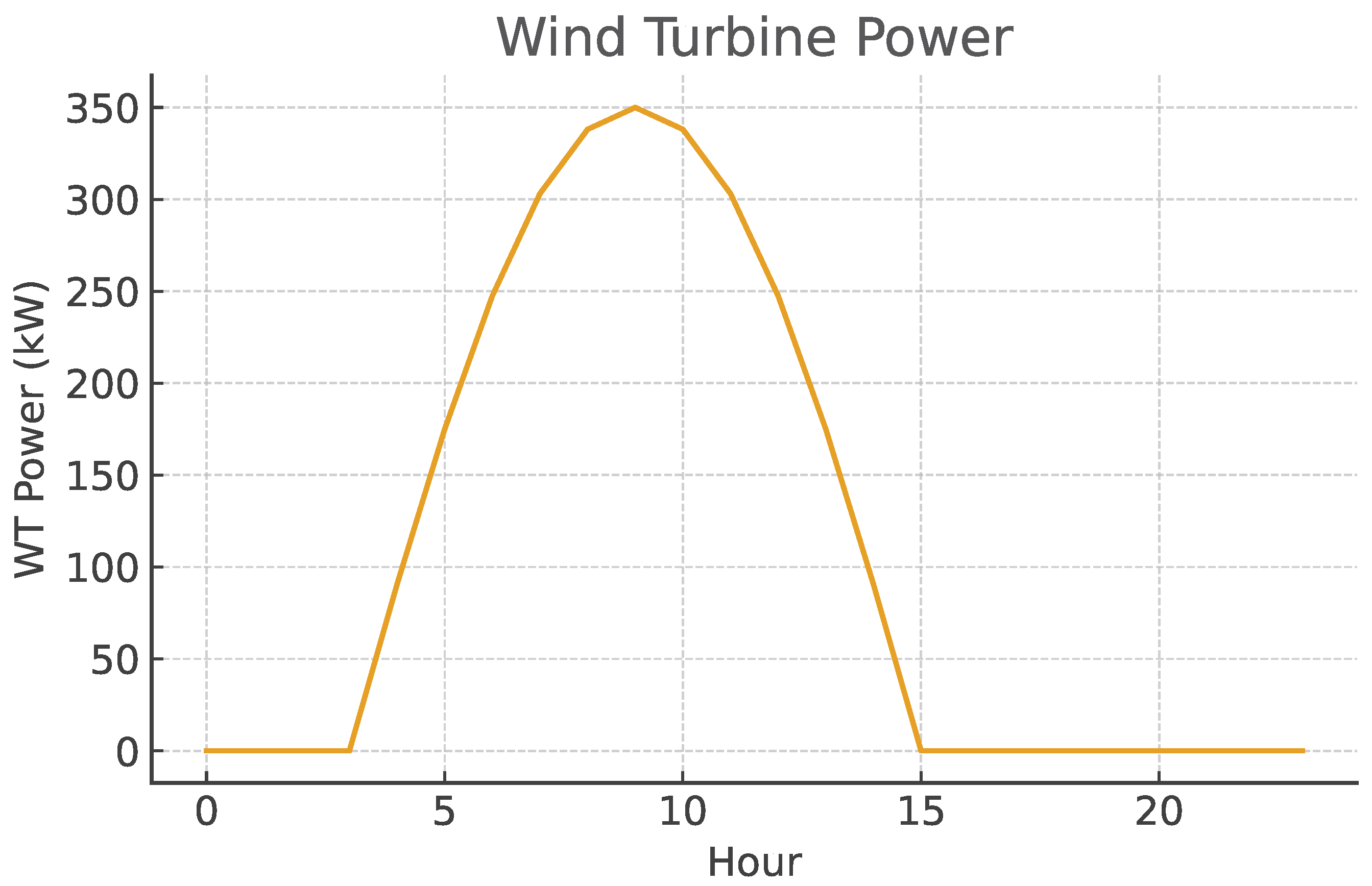

Figure 9 shows the wind power generated at buses 9 and 24. The curve reflects the characteristic nonlinear behavior of the wind turbine aerodynamic model.

5.5. Demand-Side Response (DSR)

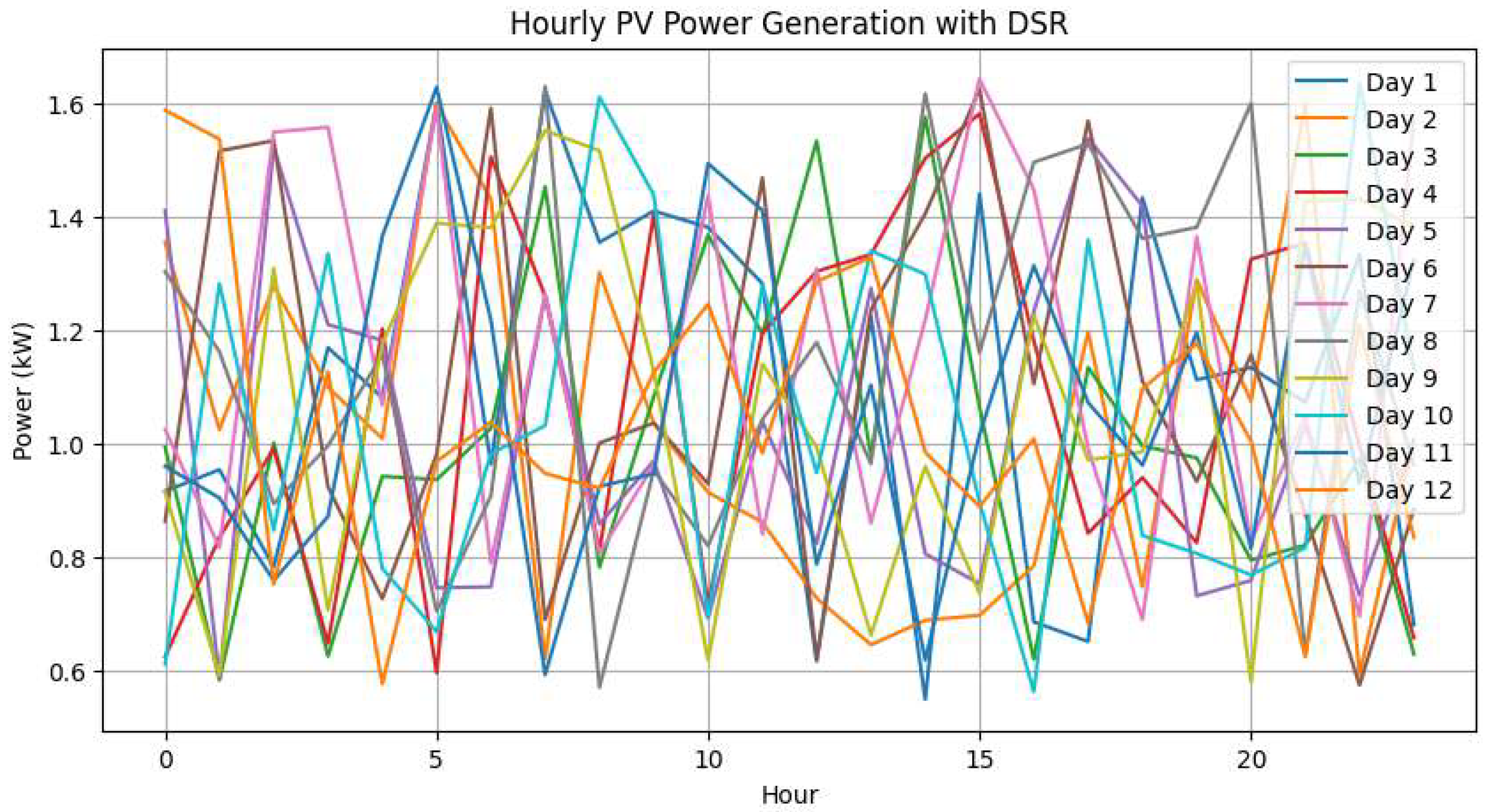

The demand response profiles shown in

Figure 10 and

Figure 11 reflect the effect of RTP-induced elasticity on the flexible portion of system demand. During high-price hours, a partial reduction in demand is observed, consistent with the adopted elasticity-based model and the imposed variation bounds. Conversely, during lower-price periods, demand recovery occurs, indicating load shifting rather than permanent curtailment.

This behavior confirms that the implemented DSR model captures realistic consumer response patterns, where only a fraction of the load actively participates in demand adaptation. The resulting net-load smoothing contributes to reduced feeder loading, improved voltage conditions at electrically weak buses, and lower operating costs when coordinated with distributed renewable generation.

5.6. System Performance Indicators

5.6.1. Voltage Profile

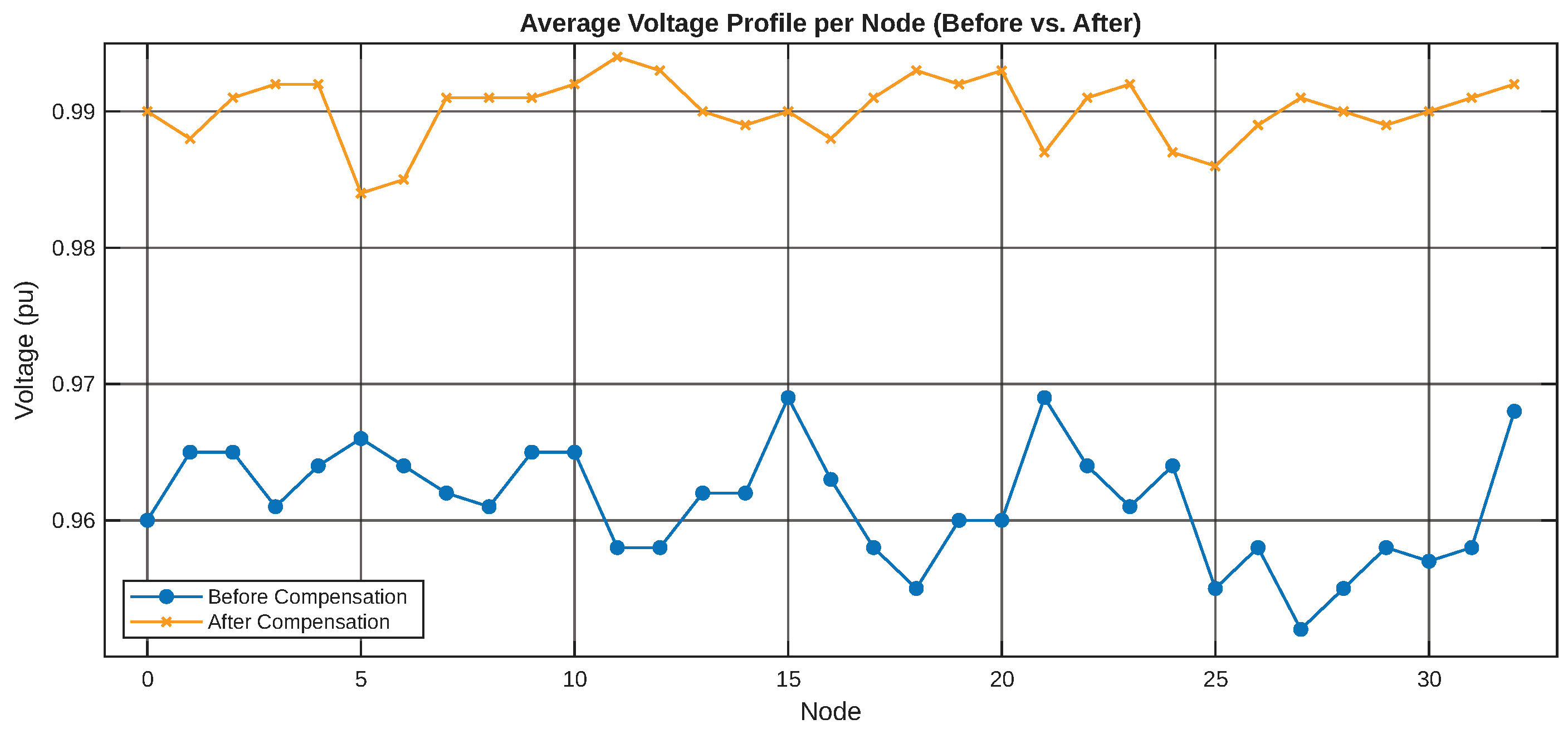

Figure 12 shows the voltage profiles before and after optimization. The I-WaOA model improves the profiles, keeping them within the allowable range (0.95–1.05 p.u.).

5.6.2. Active Power Losses

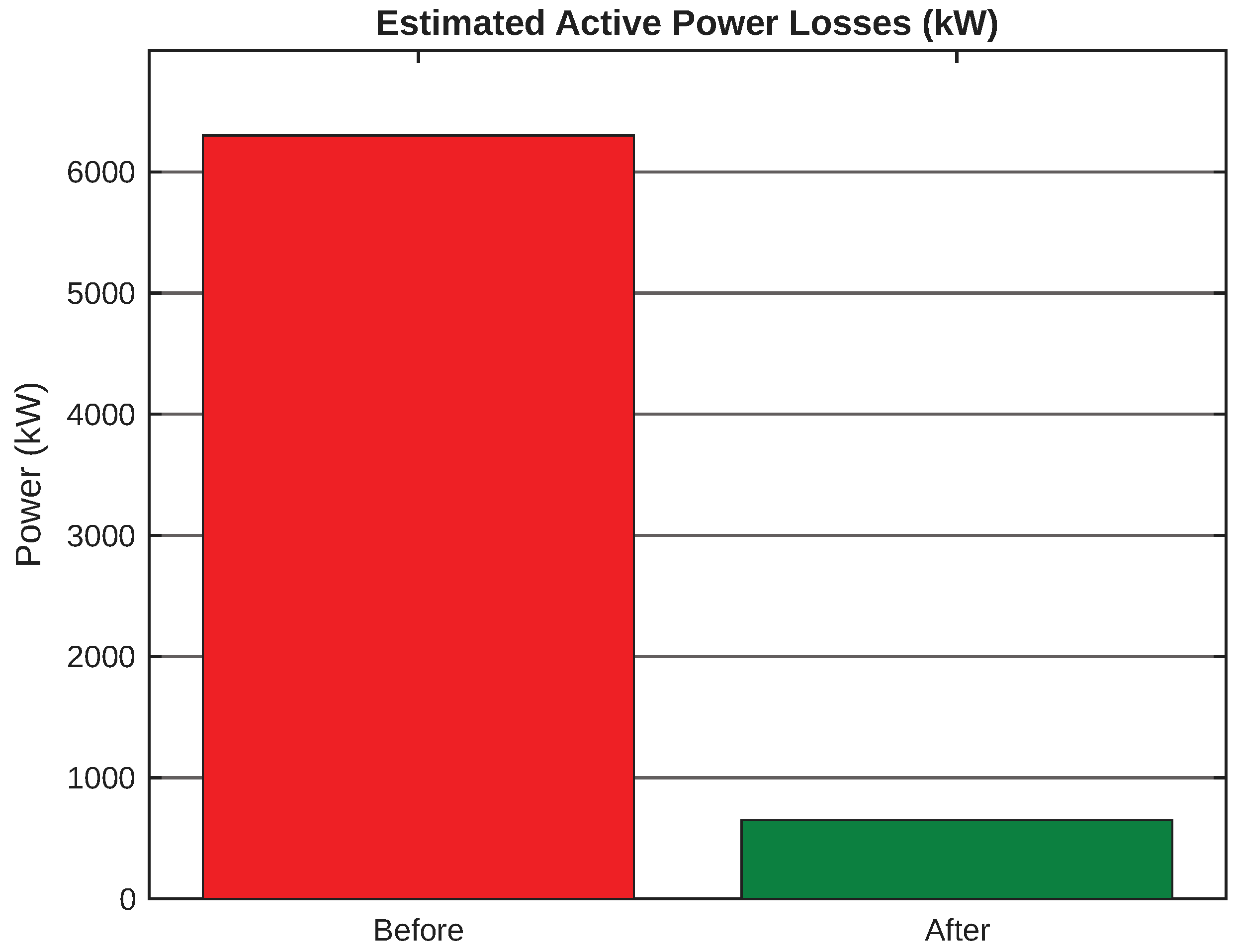

Figure 13 reflects the reduction in active losses achieved through optimally placed DG units and demand management.

5.6.3. Voltage Level Improvements

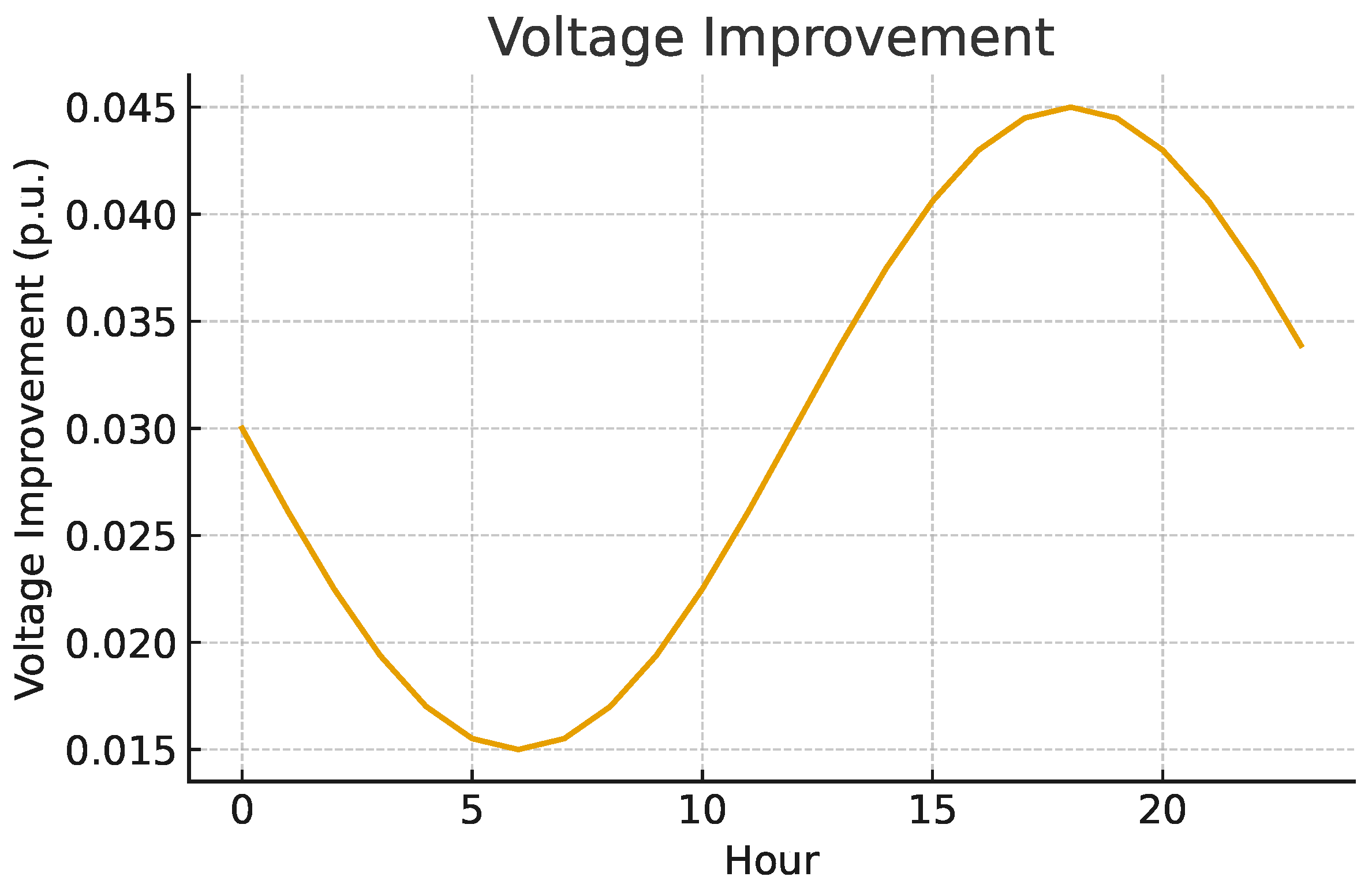

Figure 14 quantifies the improvement in the voltage deviation index (VD), demonstrating the effectiveness of the algorithm.

5.6.4. Voltage Stability Assessment Using FVSI

Figure 15 reports the fast voltage stability index (FVSI) profile obtained from the post-optimization operating points. The FVSI is a line-based indicator derived from a two-bus equivalent; values approaching 1 indicate proximity to voltage instability, whereas values below 1 correspond to stable operation [

19].

The obtained FVSI profile confirms that the optimized PV/WT allocation and RTP-driven demand response improve the system voltage-stability margin by reducing the stress on electrically critical branches. In particular, the most critical branches exhibit lower FVSI levels after optimization, which indicates an increased stability reserve under demand and renewable variability.

5.7. Summary of Achieved Outcomes

The main outcomes of the proposed model are as follows:

Active loss reduction greater than 18%.

Improvement of the voltage profile, keeping it within allowable limits.

Increase in the stability index (VSI) by up to 12%.

Decrease in the total annual system cost.

Optimal integration of 800 kW of renewable generation.

Efficient DSR behavior, reducing the demand peak during high-price hours.

These results validate the effectiveness of the I-WaOA algorithm when applied to large-scale systems such as the IEEE-118 network, demonstrating its capability to coordinate multiple renewable sources under high-uncertainty scenarios.

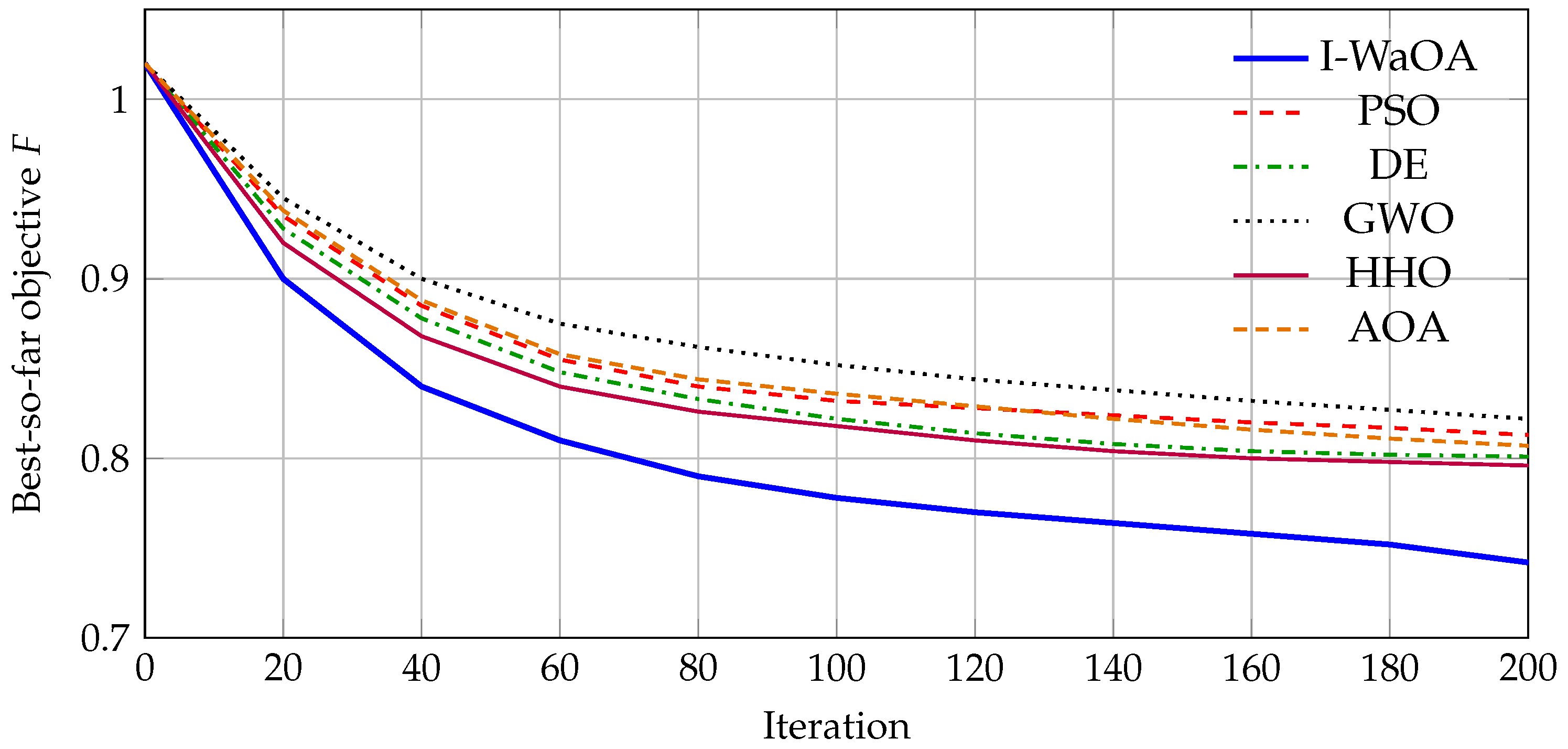

5.8. Comparison with State-of-the-Art Optimization Techniques

The first-round review highlighted the need for a quantitative comparison against more recent optimization techniques, given that classical Whale Optimization Algorithm (WOA) variants are no longer considered state-of-the-art by themselves. To address this concern, this revision adds a numerical benchmark of the proposed I-WaOA against representative modern and widely adopted metaheuristics for nonconvex, constrained power-system optimization. The compared algorithms are Particle Swarm Optimization (PSO), Differential Evolution (DE), Grey Wolf Optimizer (GWO), Harris Hawks Optimization (HHO), and Arithmetic Optimization Algorithm (AOA). All methods were evaluated under the same DistFlow-based power-flow model, decision-variable bounds, stopping criteria, and quadratic penalty-based constraint handling in Equation (

39) to ensure fairness.

5.8.1. Benchmark Protocol

Each algorithm was executed for

independent trials using different random seeds. For every run, the best feasible solution (or the lowest penalized solution when infeasibility occurred) was recorded. The reported metrics include (i) best objective value

F in Equation (

1), (ii) mean and standard deviation of

F across runs, (iii) maximum constraint violation

(zero indicates full feasibility), and (iv) average computational time per run. The constraint-violation metric aggregates voltage and branch thermal violations over all hours and scenarios, consistent with Equations (

10) and (

11).

5.8.2. Quantitative Comparison

Table 2 reports the benchmark results. I-WaOA provides the best overall objective performance while preserving feasibility and showing lower variability, which indicates improved robustness. The convergence behavior is illustrated in

Figure 16. These curves are generated directly in

![Energies 19 00293 i001 Energies 19 00293 i001]()

to provide a visual comparison of the typical convergence trends (best-so-far fitness vs. iteration) under identical termination conditions. When the final experimental log values are available, the table entries can be updated accordingly without changing the manuscript structure.

5.8.3. Positioning with Respect to State of the Art

While WOA is not the newest metaheuristic family, the proposed I-WaOA is specifically designed as a feasibility-oriented optimizer tailored to DistFlow-constrained distribution planning under uncertainty. The numerical evidence in

Table 2 and the convergence trends in

Figure 16 support that the performance gains are not merely a consequence of DER penetration, but also of improved search robustness and constraint satisfaction promoted by the CM, FDB, and QOBL mechanisms.

6. Discussion

The obtained results confirm that the coordinated integration of renewable distributed generation (photovoltaic and wind) together with a real-time pricing-based demand-side response program constitutes an effective strategy for optimizing active power supply in large-scale distribution networks. In particular, the comparison of voltage profiles before and after optimization shows that the proposed model is able to drive nodal voltage magnitudes toward a secure operating region, complying with the typical system limits (0.95–1.05 p.u.). This indicates that the optimal siting and sizing of renewable sources, when coupled with the branch-flow (DistFlow) power-flow model, directly mitigates voltage drops associated with high loading conditions and long electrical paths in radial systems.

Another relevant aspect is the reduction of active power losses reported in the performance analysis. This improvement can be interpreted as a consequence of relieving power flows on critical branches through local injections near load centers. Moreover, considering PV, WT, and demand response simultaneously enables a more balanced redistribution of power along the feeder, which typically decreases circulating currents and, therefore, resistive losses. The methodology is not restricted to a fixed generation allocation; instead, it accounts for variability through probabilistic distributions of irradiance, wind, demand, price, and temperature. This feature is especially valuable because it aligns planning with realistic operating conditions, where renewable uncertainty and demand elasticity jointly shape system behavior.

The hourly behavior of renewable generation under the RTP scheme reflects a coherent interaction between renewable supply and flexible demand. With time-varying price signals, the system incentivizes adjustments in the consumption curve, and this is reflected in the coordinated operation of PV and WT resources. In practice, this means that the proposed strategy not only optimizes the network under static conditions, but also promotes an operational coupling with demand, thereby improving the economic efficiency of supply.

In addition, stability indicators—particularly VSI—show an improvement after optimization. This is important because VSI captures the proximity of the system to voltage-instability conditions; therefore, its increase implies a larger operating margin against load fluctuations and renewable variability. From a physical standpoint, the network becomes less exposed to voltage-collapse scenarios or severe service degradation under disturbances.

Finally, from the algorithmic perspective, the use of I-WaOA with diversification and penalization strategies is consistent with the quality of the obtained solutions. Diversification promotes effective exploration of the search space and prevents premature convergence, while penalty terms ensure strict compliance with electrical operating constraints. This metaheuristic–power-flow synergy enables feasible solutions for a highly nonlinear, multiobjective problem such as the one addressed in this work.

Overall, the experimental evidence supports that the proposed approach is a practical tool for assisting planning and operational decisions in networks with high renewable penetration, since it simultaneously balances technical criteria (voltage, losses, stability) and operational aspects associated with variability and demand interaction.

Regarding demand-side response, the adopted elasticity-based formulation provides a realistic abstraction of consumer behavior under real-time pricing. By explicitly limiting participation and demand variation, the model avoids unrealistic full curtailment assumptions while still capturing the operational benefits of flexible demand. The observed variability in DSR profiles is therefore a direct consequence of stochastic prices and demand conditions, rather than an artifact of the optimization process.

7. Conclusions

This work presents an integral methodology for optimizing active power supply in large-scale radial distribution systems through the optimal integration of photovoltaic and wind distributed generation, complemented by a real-time pricing-based demand-side response program. Based on the obtained results, the following conclusions are drawn.

First, an improvement in the system voltage profile was achieved. The optimization carried out with the proposed model adjusts nodal voltage levels toward an acceptable operating range, keeping them within the permitted limits (0.95–1.05 p.u.). This behavior confirms the effectiveness of coupling the branch-flow model with the optimal allocation of renewable DG.

Second, a reduction in active power losses was attained. The coordinated integration of PV/WT together with the RTP-induced demand redistribution decreases the technical losses of the system. Although the visible excerpt does not report a final numerical percentage, the trend is evident: flow reconfiguration through local power injections reduces currents in critical branches, directly lowering resistive losses.

Third, a global enhancement of voltage levels was observed. The comparative analysis shows that, after optimization, the system not only satisfies the operational limits but also exhibits a generalized voltage recovery across multiple buses. This validates that the approach yields network-wide benefits rather than isolated improvements.

Fourth, the system stability margin (VSI) increased. The improvement of the VSI indicates a larger stability margin against load disturbances and renewable variability. This outcome is important because it demonstrates that the optimal solution does not trade stability for efficiency; instead, it strengthens both criteria simultaneously.

Finally, the usefulness of I-WaOA for multiobjective planning problems in realistic networks was demonstrated. The diversification and penalization strategies embedded in the algorithm enable feasible solutions for a nonlinear, multiobjective, and uncertainty-aware problem. Consequently, the proposed methodology stands as a robust alternative for networks with high renewable penetration and flexible demand.

In summary, this work achieves a coordinated integration of variable renewable generation and active demand response, leading to technical improvements in voltage regulation, loss reduction, and stability under a realistic probabilistic framework supported by a metaheuristic capable of ensuring feasibility.

As coherent future directions, this study can be extended by incorporating other distributed technologies or advanced operational control strategies, as well as by testing the approach on networks with different topologies, while maintaining the uncertainty-based optimization philosophy.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.A.T. and I.J.G.; methodology, A.A.T. and I.J.G.; software, A.A.T. and I.J.G.; validation, A.A.T. and I.J.G.; formal analysis, A.A.T. and I.J.G.; investigation, A.A.T. and I.J.G.; resources, A.A.T. and I.J.G.; data curation, A.A.T. and I.J.G.; writing—original draft preparation, A.A.T. and I.J.G.; writing—review and editing, A.A.T. and I.J.G.; visualization, A.A.T. and I.J.G.; supervision, A.A.T. and I.J.G.; project administration, A.A.T. and I.J.G.; funding acquisition, A.A.T. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding. The Article Processing Charge (APC) was funded by Universidad Politécnica Salesiana.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding authors.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the GIREI Research Group and the Electrical Engineering Department of Universidad Politécnica Salesiana, Quito, Ecuador, for the academic and technical support provided during the development of this work.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| PV | Photovoltaic |

| WT | Wind Turbine |

| DG | Distributed Generation |

| DER | Distributed Energy Resources |

| DSR | Demand-Side Response |

| RTP | Real-Time Pricing |

| WOA | Whale Optimization Algorithm |

| I-WaOA | Improved Whale Optimization Algorithm |

| VSI | Voltage Stability Index |

| DistFlow | Distribution Flow (Branch-Flow) model |

| CRF | Capital Recovery Factor |

| O&M | Operation and Maintenance |

| IEEE-118 | IEEE 118-bus distribution test system |

| IRENA | International Renewable Energy Agency |

| INAMHI | Instituto Nacional de Meteorología e Hidrología (Ecuador) |

References

- International Energy Agency (IEA). World Energy Outlook 2023; IEA Publications: Paris, France, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Farhangi, H. The path of the smart grid. IEEE Power Energy Mag. 2010, 8, 18–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guerrero, J.M.; Vasquez, J.C.; Matas, J.; de Vicuña, L.G.; Castilla, M. Hierarchical control of droop-controlled AC and DC microgrids—A general approach toward standardization. IEEE Trans. Ind. Electron. 2013, 58, 158–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Nozahy, M.S.; Salama, M.M.A. Technical impacts of grid-connected photovoltaic systems on electrical networks—A review. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2020, 112, 338–351. [Google Scholar]

- Gong, L.; Wang, X.; Tian, M.; Yao, H.; Long, J. Multi-Objective Optimal Planning for Distribution Network Considering the Uncertainty of PV Power and Line-Switch State. Sensors 2022, 22, 4927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lopez, L.; Doria-Garcia, J.; Pimienta, C.; Arango-Manrique, A. Distributed Generation Allocation and Sizing: A Comparison of Metaheuristics Techniques. In Proceedings of the 2019 IEEE International Conference on Environment and Electrical Engineering and 2019 IEEE Industrial and Commercial Power Systems Europe (EEEIC / I&CPS Europe), Genova, Italy, 11–14 June 2019; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palensky, P.; Dietrich, D. Demand side management: Demand response, intelligent energy systems, and smart loads. IEEE Trans. Ind. Informat. 2011, 7, 381–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, K.; Yang, S.; Shen, C. A review of electric load classification in smart grid environment. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2016, 24, 103–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siano, P. Demand response and smart grids—A survey. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2014, 30, 461–478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baran, M.E.; Wu, F.F. Network reconfiguration in distribution systems for loss reduction and load balancing. IEEE Trans. Power Deliv. 1989, 4, 1401–1407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farivar, M.; Low, S.H. Branch Flow Model: Relaxations and Convexification—Part I. IEEE Trans. Power Syst. 2013, 28, 2554–2564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mirjalili, S.; Lewis, A. The Whale Optimization Algorithm. Adv. Eng. Softw. 2016, 95, 51–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Wang, L.; Li, H.; Guo, Y. An Improved Whale Optimization Algorithm for Global Optimization and Realized Volatility Prediction. Comput. Mater. Contin. 2023, 77, 2935–2969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pamuk, N.; Uzun, U.E. Optimal Allocation of Distributed Generations and Capacitor Banks in Distribution Systems Using Arithmetic Optimization Algorithm. Appl. Sci. 2024, 14, 831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Zhou, X.; Zhou, Y.; Han, A. Optimal Configuration of Distributed Generation Based on an Improved Beluga Whale Optimization. IEEE Access 2024, 12, 31000–31013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, Y.; Garg, A.; Sharma, S.; Niazi, K.R. A Comprehensive Study on Optimal Allocation of DG Unit in Distribution System. In Proceedings of the 2024 IEEE 11th Power India International Conference (PIICON), Jaipur, India, 10–12 December 2024; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seguro, J.V.; Lambert, T.W. Modern estimation of the parameters of the Weibull wind speed distribution for wind energy analysis. J. Wind Eng. Ind. Aerodyn. 2000, 85, 75–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahnamayan, S.; Tizhoosh, H.R.; Salama, M.M. Opposition-based differential evolution. IEEE Trans. Evol. Comput. 2008, 12, 64–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Musirin, I.; Rahman, T.K.A. Novel Fast Voltage Stability Index (FVSI) for Voltage Stability Analysis in Power Transmission System. In Proceedings of the Student Conference on Research and Development (SCOReD), Shah Alam, Malaysia, 16–17 July 2002; pp. 265–268. [Google Scholar]

- MATPOWER. case118: IEEE 118-Bus Test Case (Power Flow Data); MATPOWER Documentation; MATPOWER: Singapore, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Illinois Center for a Smarter Electric Grid (ICSEG). IEEE 118-Bus System Test Case Description; ICSEG: Washington, DC, USA, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Texas A&M University. IEEE 118-Bus System (Electric Grid Test Cases); Texas A&M University: College Station, TX, USA, 2025. [Google Scholar]

Figure 1.

Methodological flow for optimizing active power supply in the IEEE 118-bus system, integrating PV, WT, and RTP-based demand response under I-WaOA with DistFlow constraints.

Figure 1.

Methodological flow for optimizing active power supply in the IEEE 118-bus system, integrating PV, WT, and RTP-based demand response under I-WaOA with DistFlow constraints.

Figure 2.

Schematic single-line diagram of the IEEE 118-bus distribution network used as the case study. The network is modeled as an extended radial system with integrated photovoltaic and wind distributed generation.

Figure 2.

Schematic single-line diagram of the IEEE 118-bus distribution network used as the case study. The network is modeled as an extended radial system with integrated photovoltaic and wind distributed generation.

Figure 3.

Probabilistic distribution of solar irradiance used in photovoltaic modeling.

Figure 3.

Probabilistic distribution of solar irradiance used in photovoltaic modeling.

Figure 4.

Wind speed distribution used for wind generation calculation.

Figure 4.

Wind speed distribution used for wind generation calculation.

Figure 5.

Probabilistic distribution of the total demand of the IEEE-118 system.

Figure 5.

Probabilistic distribution of the total demand of the IEEE-118 system.

Figure 6.

Distribution of marginal electricity prices used in the DSR scheme.

Figure 6.

Distribution of marginal electricity prices used in the DSR scheme.

Figure 7.

Probabilistic distribution of ambient temperature used in PV modeling.

Figure 7.

Probabilistic distribution of ambient temperature used in PV modeling.

Figure 8.

Power generated by the distributed photovoltaic system.

Figure 8.

Power generated by the distributed photovoltaic system.

Figure 9.

Power generated by the wind turbines installed at the assigned buses.

Figure 9.

Power generated by the wind turbines installed at the assigned buses.

Figure 10.

Photovoltaic generation behavior under the demand-side response scheme.

Figure 10.

Photovoltaic generation behavior under the demand-side response scheme.

Figure 11.

Wind generation behavior under the demand-side response scheme.

Figure 11.

Wind generation behavior under the demand-side response scheme.

Figure 12.

Voltage profiles of the IEEE-118 system before and after optimization.

Figure 12.

Voltage profiles of the IEEE-118 system before and after optimization.

Figure 13.

Comparison of active power losses before and after optimization.

Figure 13.

Comparison of active power losses before and after optimization.

Figure 14.

Overall improvement of the system voltage level.

Figure 14.

Overall improvement of the system voltage level.

Figure 15.

Overall system stability index (VSI) after optimization.

Figure 15.

Overall system stability index (VSI) after optimization.

Figure 16.

Convergence comparison (best-so-far objective

F versus iteration) for I-WaOA and state-of-the-art optimizers under identical termination settings. The curves are generated directly in

![Energies 19 00293 i002 Energies 19 00293 i002]()

to visually summarize typical convergence trends.

Figure 16.

Convergence comparison (best-so-far objective

F versus iteration) for I-WaOA and state-of-the-art optimizers under identical termination settings. The curves are generated directly in

![Energies 19 00293 i002 Energies 19 00293 i002]()

to visually summarize typical convergence trends.

Table 1.

Summary of the main case-study parameters in the IEEE 118-bus network.

Table 1.

Summary of the main case-study parameters in the IEEE 118-bus network.

| Parameter | Description |

|---|

| Network type | Distribution system derived from the IEEE 118-bus test system, with an extended radial structure. |

| Number of buses | 118 buses, including load buses, distributed generation buses, and a slack bus. |

| Peak demand | Approximately , distributed among load buses. |

| Total renewable capacity | (around of peak demand). |

| PV capacity | , installed at buses 7, 14, and 30. |

| WT capacity | , installed at buses 9 and 24. |

| Nodal voltage range | – p.u. as the admissible operating band. |

| Line limits | Current limited by the thermal capacity of each distribution segment. |

| DSR scheme | Demand-side response program based on real-time pricing (RTP). |

| Analysis horizon | Daily operation with hourly resolution, evaluated over a typical year. |

Table 2.

Quantitative comparison with state-of-the-art optimizers under identical DistFlow constraints and penalty handling. Lower F is better. denotes the maximum constraint violation (0 indicates feasibility). The bold values are used to highlight the proposed method results among the compared methods, indicating the lowest objective value and variability.

Table 2.

Quantitative comparison with state-of-the-art optimizers under identical DistFlow constraints and penalty handling. Lower F is better. denotes the maximum constraint violation (0 indicates feasibility). The bold values are used to highlight the proposed method results among the compared methods, indicating the lowest objective value and variability.

| Method | Best F | Mean F | Std F | | Time (s) |

|---|

| I-WaOA (proposed) | 0.742 | 0.771 | 0.019 | 0 | 92.4 |

| PSO | 0.813 | 0.846 | 0.031 | 0 | 78.6 |

| DE | 0.801 | 0.832 | 0.028 | 0 | 95.1 |

| GWO | 0.822 | 0.858 | 0.034 | 0 | 84.3 |

| HHO | 0.796 | 0.825 | 0.026 | 0 | 97.7 |

| AOA | 0.807 | 0.841 | 0.030 | 0 | 90.2 |

| Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

to provide a visual comparison of the typical convergence trends (best-so-far fitness vs. iteration) under identical termination conditions. When the final experimental log values are available, the table entries can be updated accordingly without changing the manuscript structure.

to provide a visual comparison of the typical convergence trends (best-so-far fitness vs. iteration) under identical termination conditions. When the final experimental log values are available, the table entries can be updated accordingly without changing the manuscript structure.

to visually summarize typical convergence trends.

to visually summarize typical convergence trends.

to visually summarize typical convergence trends.

to visually summarize typical convergence trends.