The Application of Rate Transient Analysis for the Production Performance Evaluation of the Temane Gas Field–Mozambique: The Use of the Per-Well Basis Approach

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Rate Transient Analysis Methods: Blasingame, Normalized Rate–Cumulative, and Flowing Material Balance

2.1. Blasingame Method

2.2. Normalized Rate–Cumulative (NRC) Method

2.3. Flowing Material Balance (FMB) Method

3. Methodology

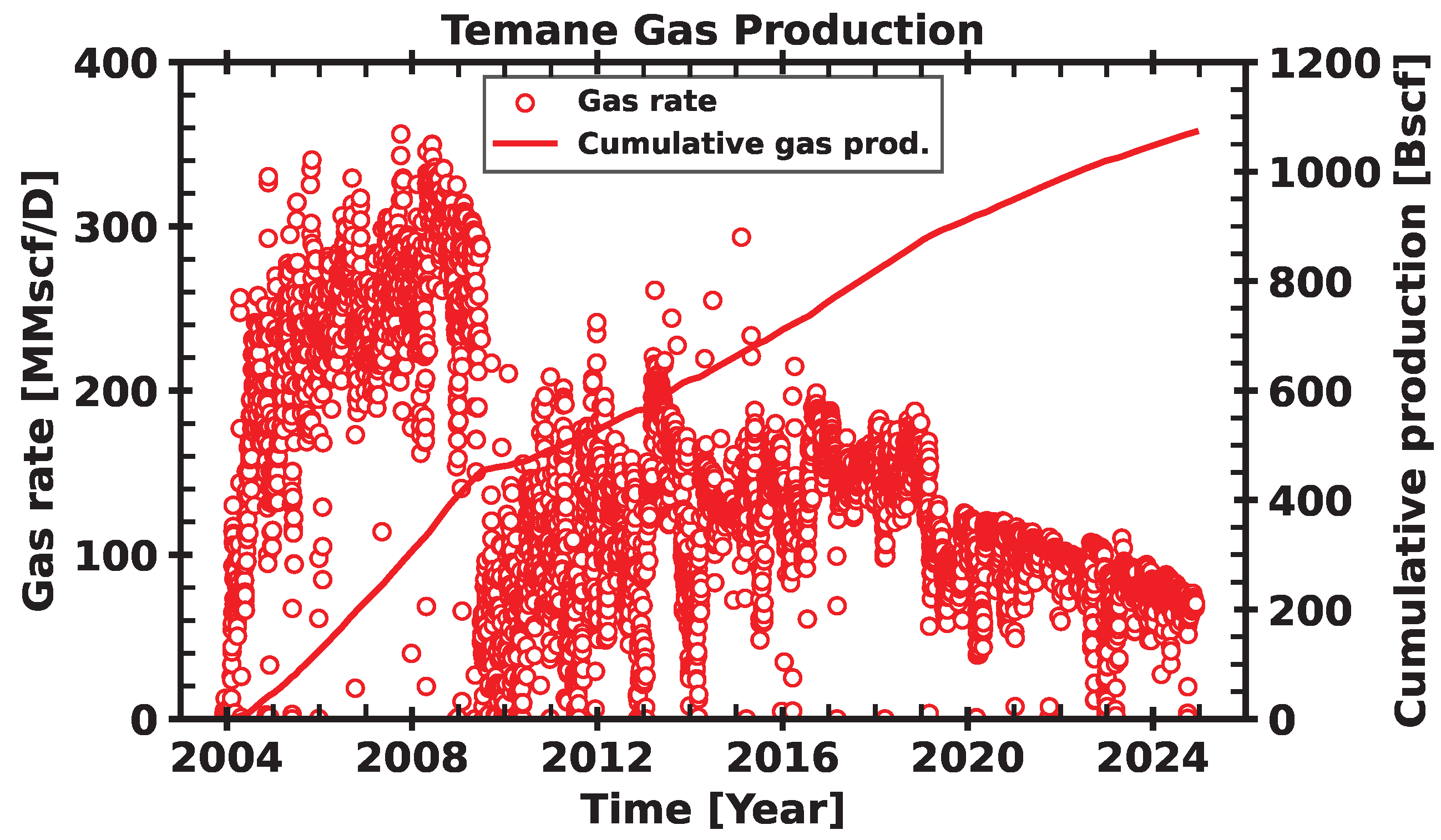

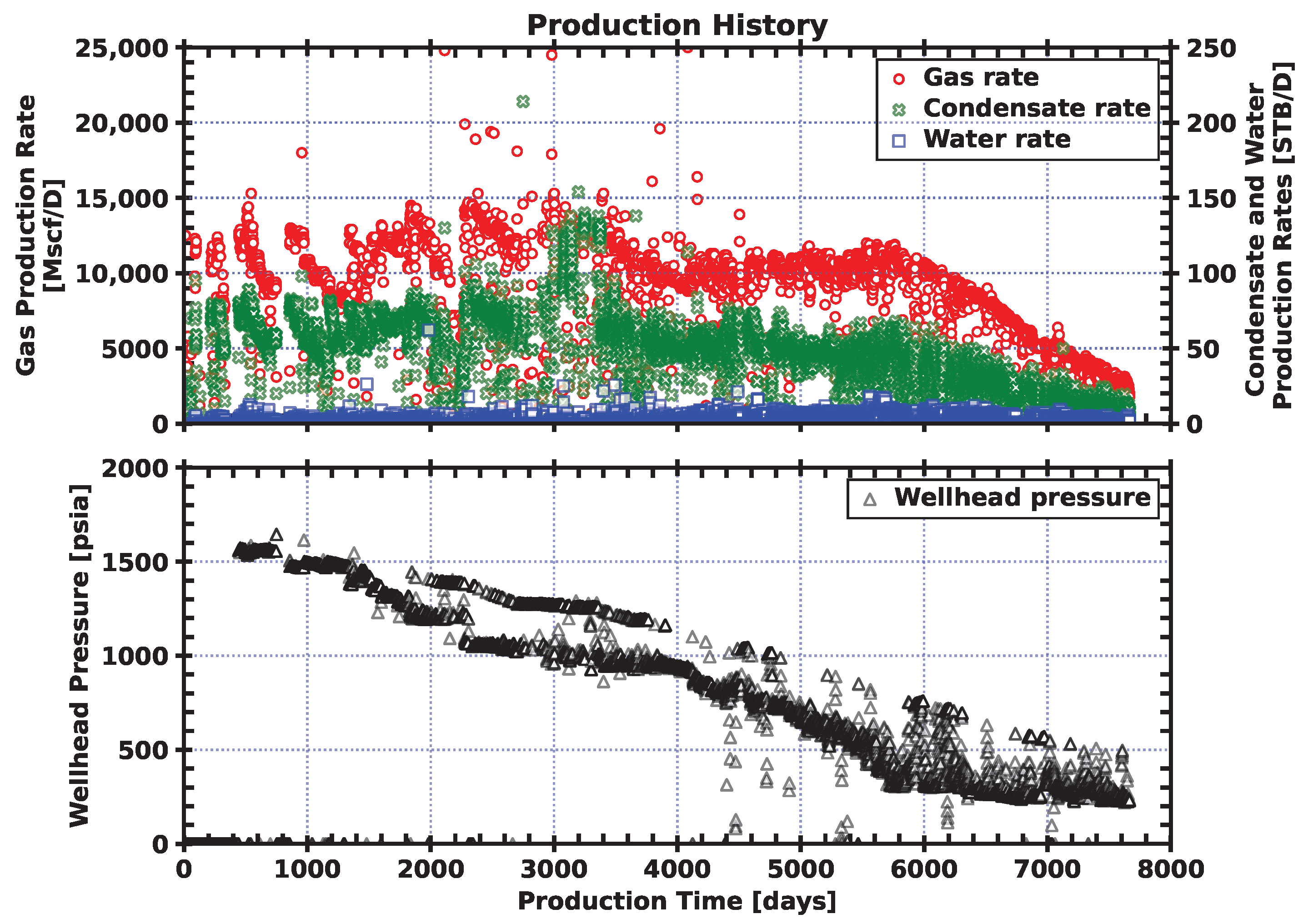

3.1. Field Description and Gas Production History

3.2. Data Preparation

3.3. Flow Regime and Spurious Data Identification

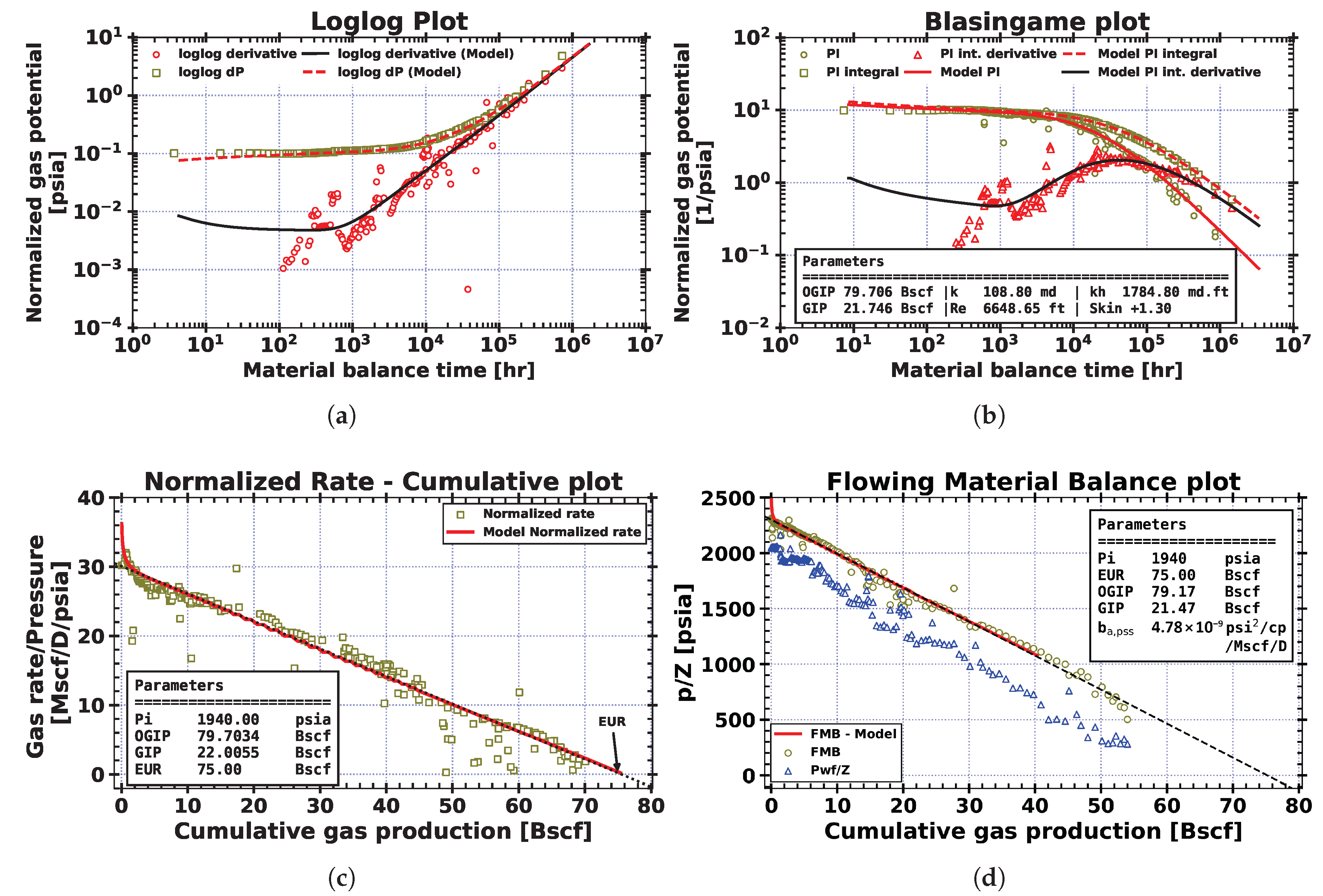

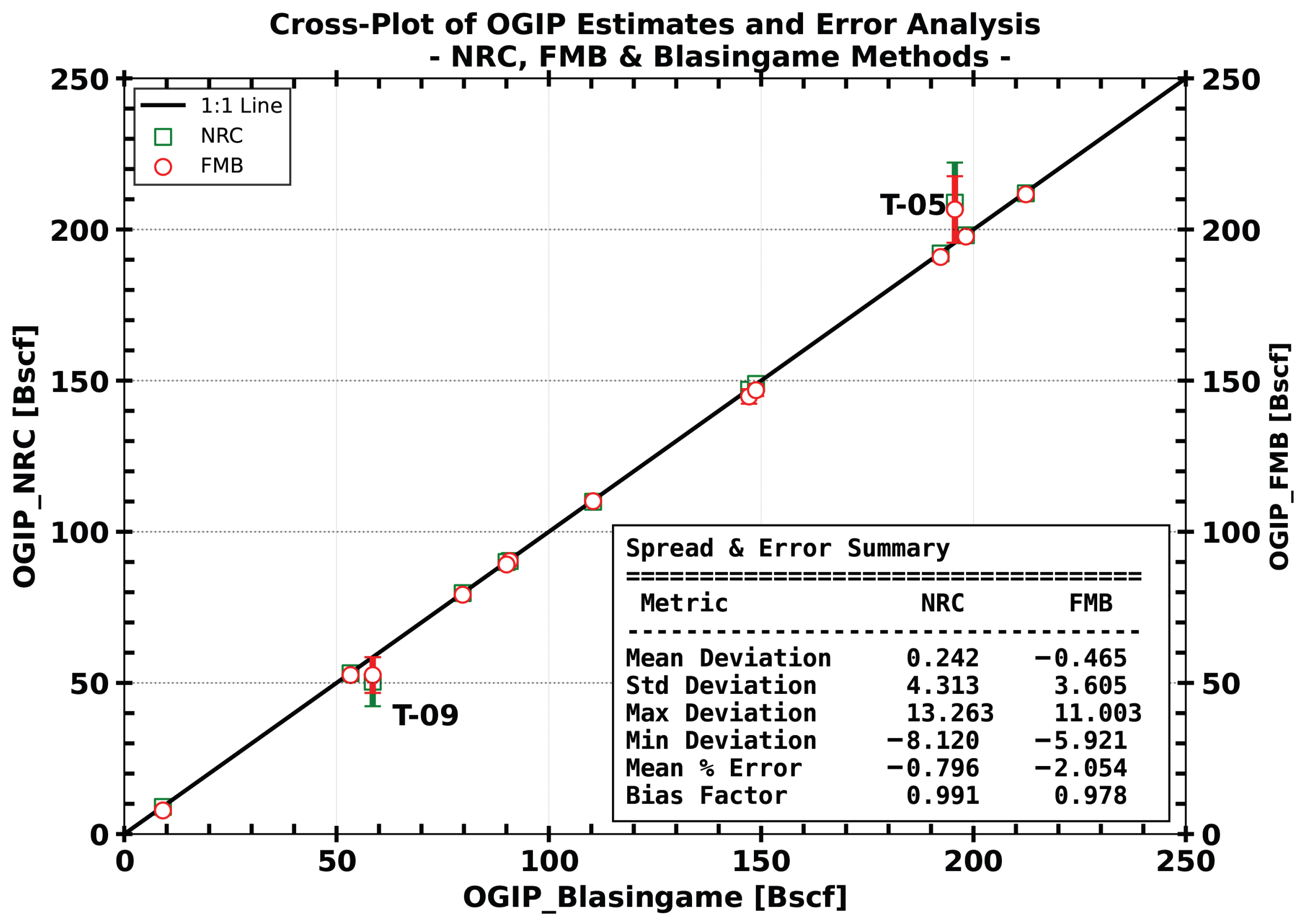

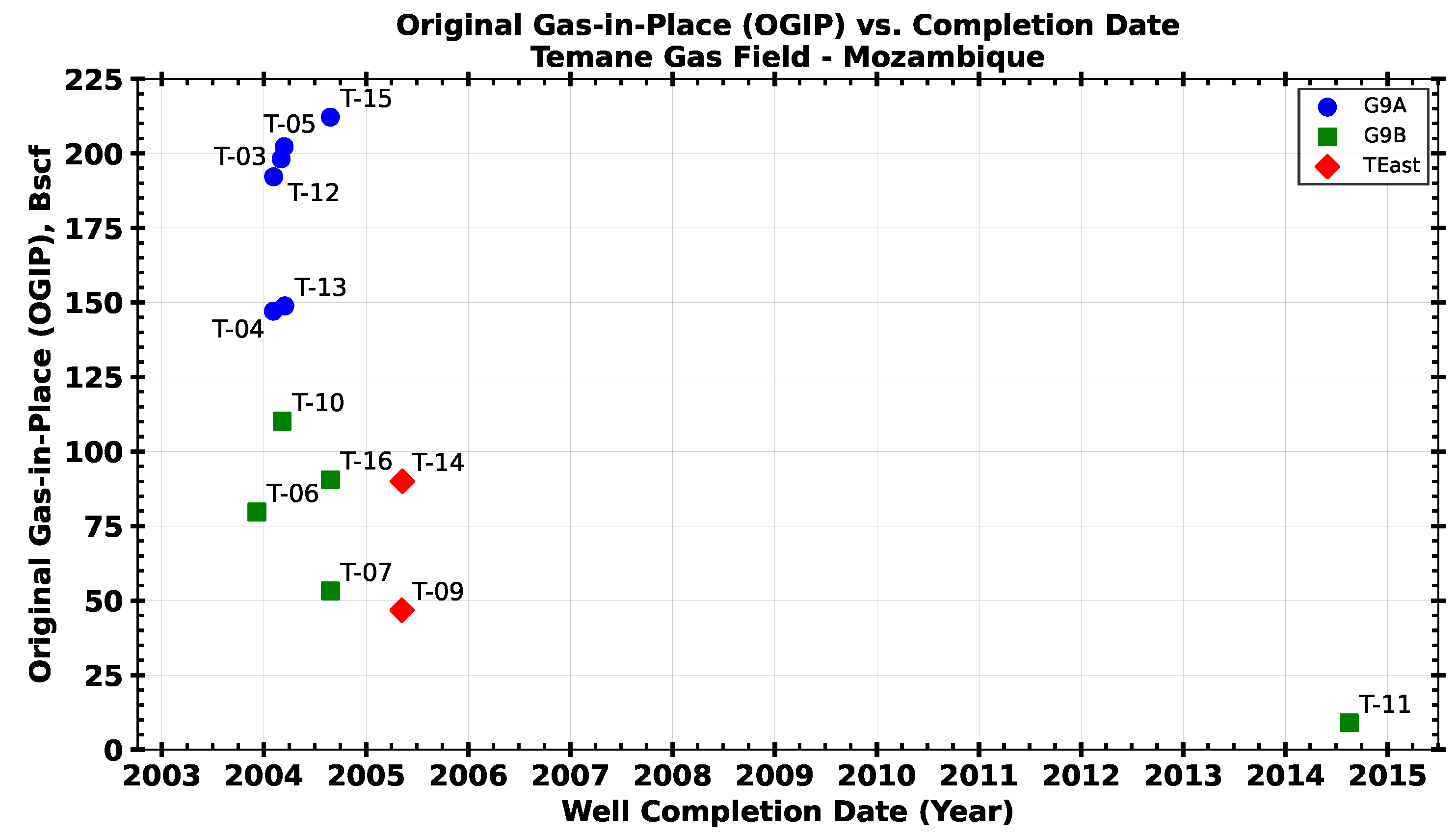

3.4. Original Gas-in-Place and Recovery Factor Estimations

- Rate-trend deviation analysis: identifying deviations in the normalized rate function from the characteristic negative-unit-slope declining trend in the Blasingame plot, following the methodology proposed by Anderson and Mattar [8];

- Reserve trend analysis: the evaluation of OGIP as a function of the well completion date, as proposed by Medina Tarrazzi [39].

4. Results and Discussion

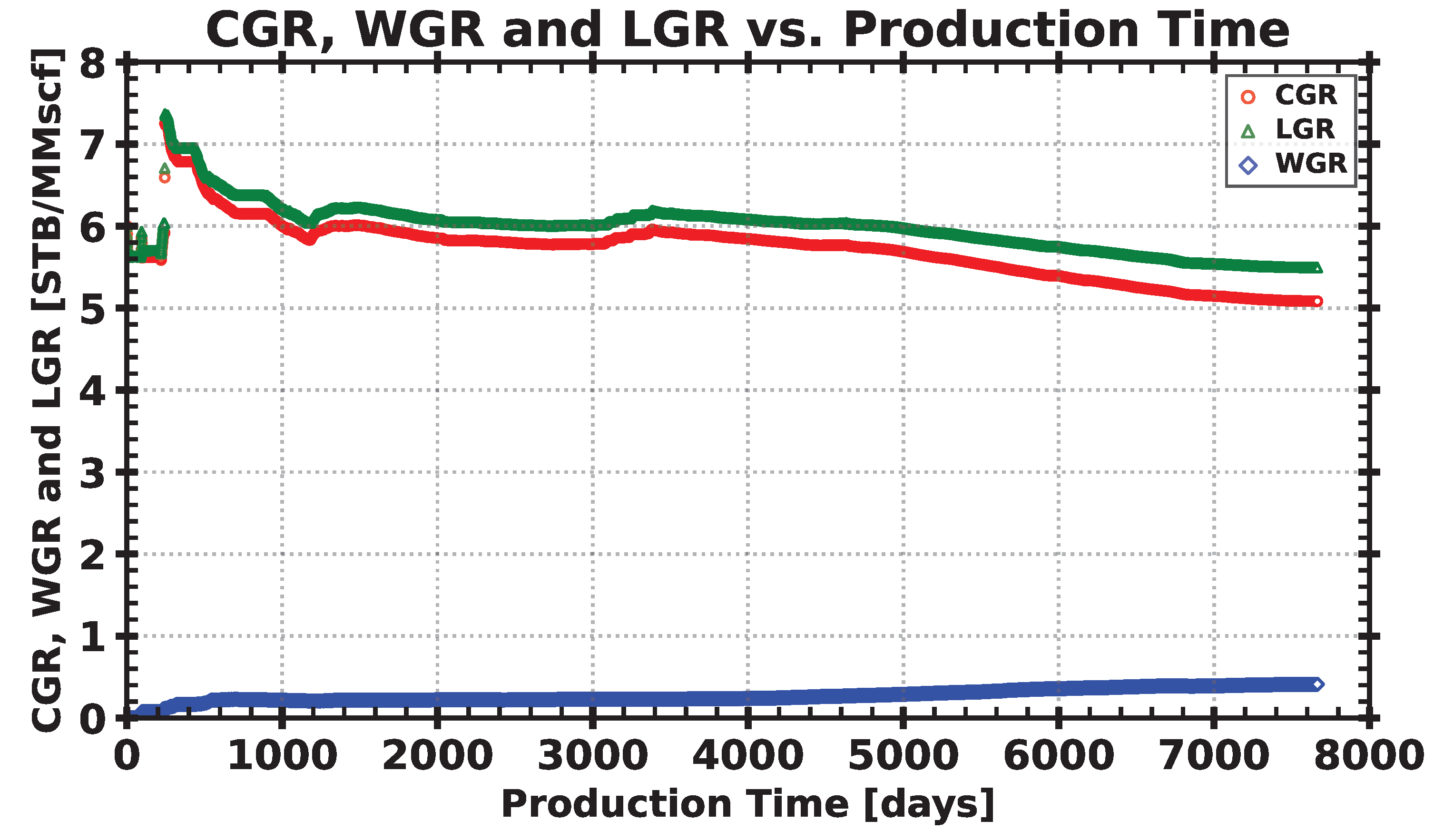

4.1. Data Quality and Diagnosis

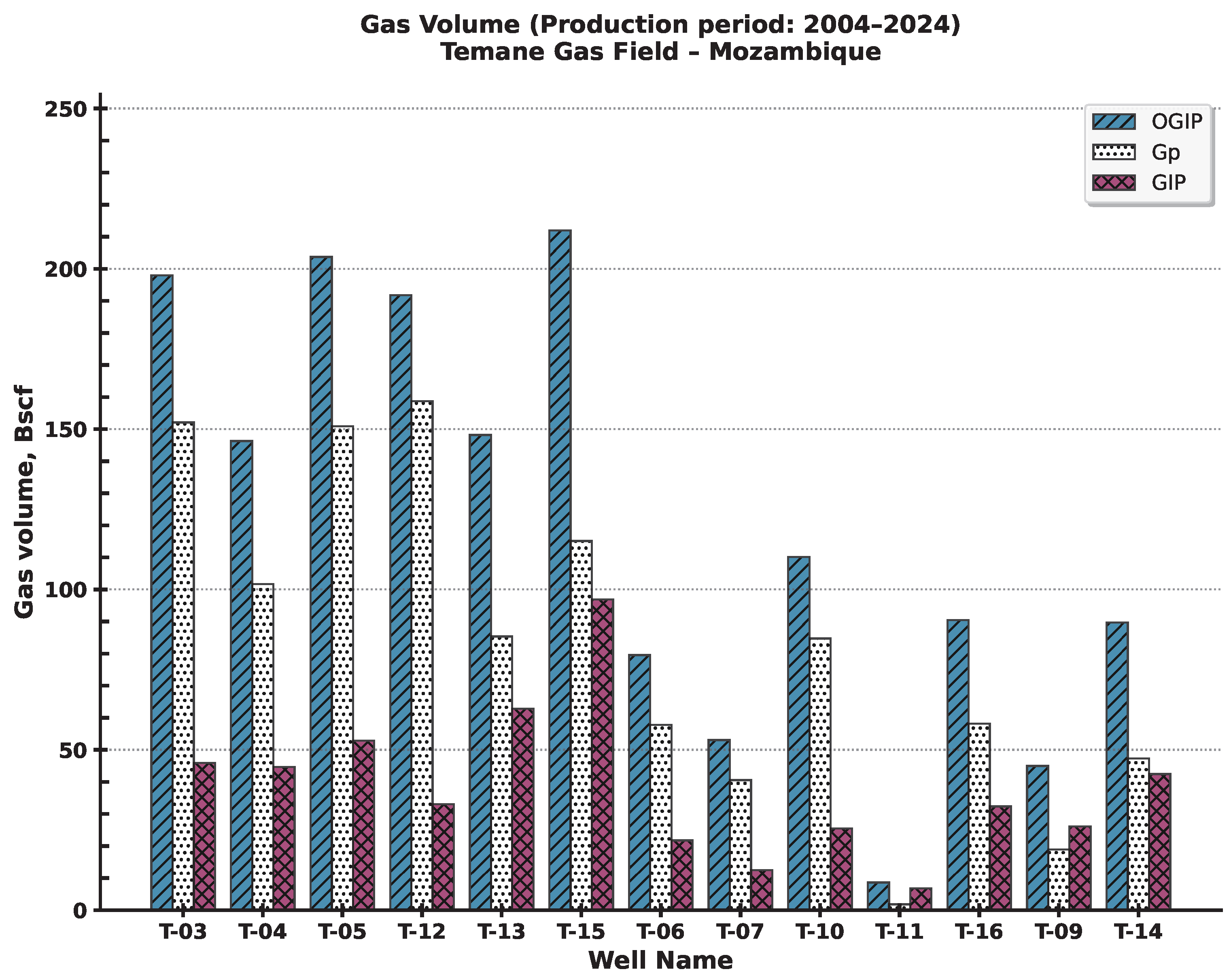

4.2. Original Gas-in-Place (OGIP) and Remaining Gas-in-Place (GIP) Values

5. Conclusions

- All three methods yielded comparable estimates for the OGIP, cumulative production (Gp), and remaining gas in place (GIP), with average values of 1576.38 Bscf, 1073.01 Bscf, and 503.37 Bscf, respectively;

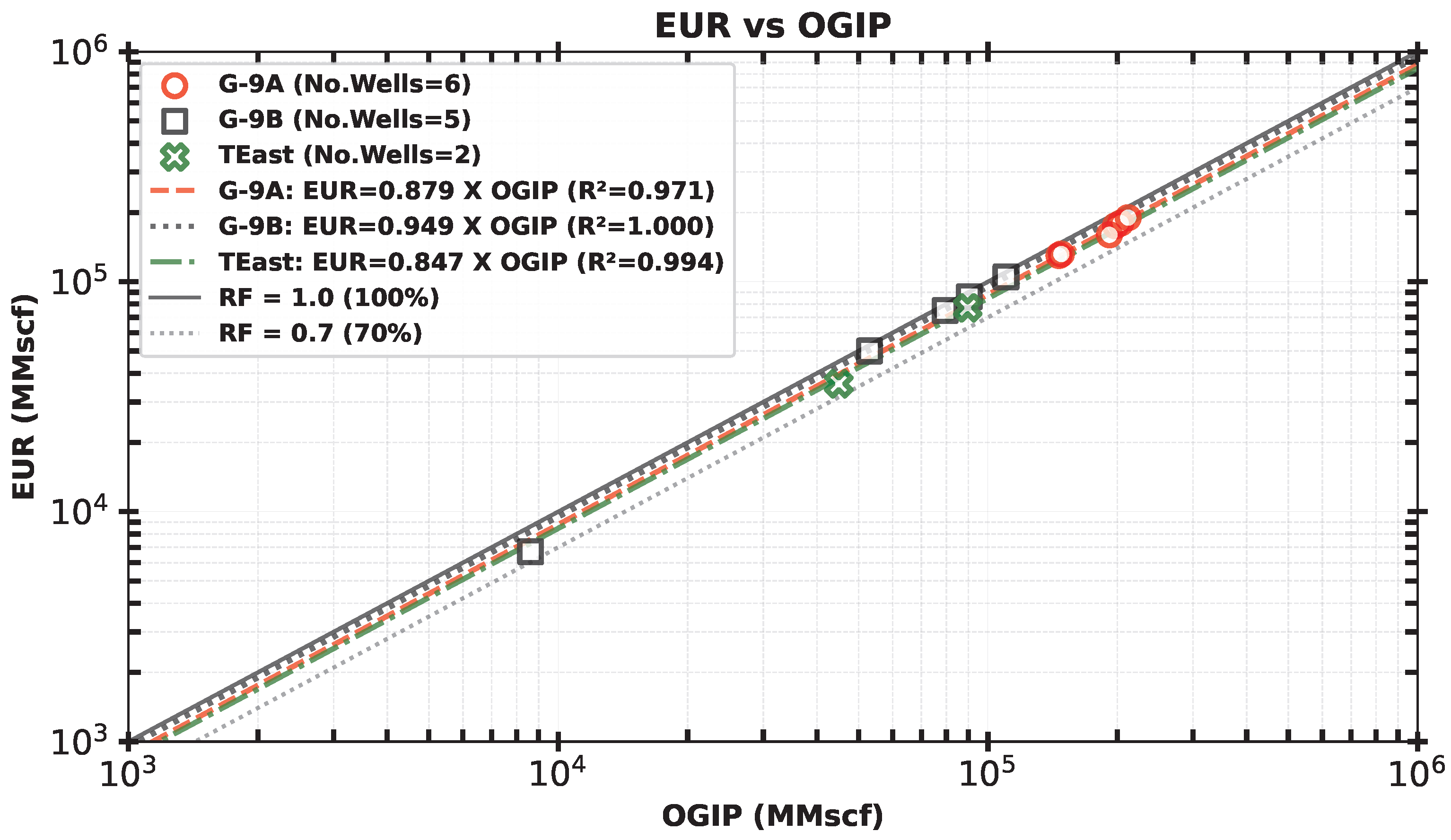

- The estimated ultimate recovery (EUR) of the Temane gas field is approximately 1405.25 Bscf, corresponding to an ultimate recovery factor of approximately 89.14%. As of 1 December 2024, approximately 76.36% of the EUR has been produced;

- Reservoirs G-9A and G-9B are the most depleted, followed by the TEast reservoir, with recovery factors of approximately 79%, 74.92%, and 58.01%, respectively. The lower recovery factor in the TEast reservoir is attributed to the temporary shut-in of both production wells due to well integrity issues.

- The estimated EUR of 1405.25 Bscf compares well with the operator’s reported mid reserves of approximately 1334.00 Bscf, showing a difference of only 5.34%. This close agreement supports the assumption of substantially independent drainage areas. However, because this analysis was conducted assuming the non-occurrence of inter-well interference based on rate trends observed in the Blasingame method and reserve trend analysis, additional studies, such as interference tests or tracer studies, would be required for the definitive confirmation of flow barriers between wells across all three reservoirs in the Temane gas field.

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Nomenclature

| Abbreviations | |

| BHFP | Bottomhole flowing pressure |

| CPF | Central processing facility |

| EUR | Estimated ultimate recovery |

| FMB | Flowing material balance |

| FY | Fiscal year |

| GIP | Remaining gas in place |

| Gp | Cumulative gas production |

| MAE | Mean absolute error |

| MAPE | Mean absolute percentage error |

| OGIP | Original gas in place |

| RF | Recovery factor |

| RMSE | Root mean square error |

| ROMPCO | Republic of Mozambique Pipeline Company |

| RTA | Rate transient analysis |

| Field variables | |

| A | drainage area, sq. ft. |

| pseudosteady-state constant, psia/Mscf/D | |

| gas formation volume factor, RB/Mscf | |

| Dietz shape factor | |

| condensate–gas ratio, STB/Mscf | |

| gas isothermal compressibility, 1/psia | |

| total system compressibility, 1/psia | |

| G | original gas in place, MMscf or Bscf |

| h | thickness, ft. |

| k | permeability, md |

| liquid–gas ratio, STB/Mscf | |

| real gas pseudopressure, psia2/cp | |

| average reservoir pressure, psia | |

| normalized pseudopressure, psia | |

| flowing bottomhole pressure, psia | |

| normalized pseudopressure drop, psia | |

| gas production flow rate, Mscf/D | |

| dimensionless gas flow rate | |

| dimensionless cumulative production based on area | |

| external drainage radius, ft. | |

| wellbore radius, ft. | |

| initial water saturation, fraction | |

| t | time, days |

| T | temperature, ∘F |

| water–gas ratio, STB/Mscf | |

| Z | gas deviation factor, fraction |

| Greek Letters | |

| gas viscosity, cp | |

| porosity, fraction | |

| Euler’s constant, | |

| Circumference-to-diameter ratio, |

References

- Gakusi, A.E.; Sartori, D.; Asamoah, J. Fostering Regional Integration in Africa: Lessons from Sasol Natural Gas Project between South Africa and Mozambique. Open J. Soc. Sci. 2015, 3, 187–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salimo, P.; Buur, L.; Macuane, J.J. The politics of domestic gas: The Sasol natural gas deals in Mozambique. Extr. Ind. Soc. 2020, 7, 1219–1229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- SAGMP. South African Gas Master Plan Consultation Document, Technical Report; Centre for Environmental Rights (CER): Cape Town, South Africa, 2021. Available online: https://cer.org.za/wp-content/uploads/2022/02/Gas-Master-Plan-Consultation-Document-Rev-I.pdf (accessed on 9 December 2025).

- CMH. Relatório Anual e Demonstrações Financeiras, Technical Report; Companhia Moçambicana de Hidrocarbonetos, S.A.: Maputo, Moçambique, 2025. Available online: https://cmh.co.mz/images/Relatorio&Contas/Financial_Statements_FY25_PT.pdf (accessed on 9 December 2025).

- Sasol. Business Performance Metrics, Technical Report; Sasol, Ltd.: Johannesburg, South Africa, 2025. Available online: https://www.sasol.com/sites/default/files/2025-10/Business%20Performance%20metrics%20for%20the%20three%20months%20ended%2030%20September%202025.pdf (accessed on 6 December 2025).

- Macie, C.A. Production-based Characterization of the Temane Gas Field. Master’s Thesis, Universidade Eduardo Mondlane, Maputo, Moçambique, 2016. (In Mozambique). [Google Scholar]

- Clarke, A.; Imber, J.; Davies, R.; Van Hunen, J.; Daniels, S.; Yielding, G. Application of material balance methods to CO2 storage capacity estimation within selected depleted gas reservoirs. Pet. Geosci. 2017, 23, 339–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, D.; Mattar, L. Practical diagnostics using production data and flowing pressures. In Proceedings of the SPE Annual Technical Conference and Exhibition, Houston, TX, USA, 26–29 September 2004; SPE: Houston, TX, USA, 2004; p. SPE-89939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, D.; Thompson, J.M.; Behmanesh, H. Diagnosing the health of your well with rate transient analysis. In Proceedings of the Unconventional Resources Technology Conference, Houston, TX, USA, 23–25 July 2018; Society of Exploration Geophysicists, American Association of Petroleum Geologists, Society of Petroleum Engineers: Houston, TX, USA, 2018; p. URTeC 2902908. [Google Scholar]

- Arps, J.J. Analysis of decline curves. Trans. AIME 1945, 160, 228–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arnold, R.; Anderson, R. Preliminary Report on the Coalinga Oil District, Fresno and Kings Counties, California; Number 357; US Government Printing Office: Washington, DC, USA, 1908. [Google Scholar]

- Cutler, W.W. Estimation of Underground Oil Reserves by Oil-Well Production Curves; Number 228; US Government Printing Office: Washington, DC, USA, 1924. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson, R.H.; Bollens, A. The loss ratio method of extrapolating oil well decline curves. Trans. AIME 1927, 77, 771–778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blasingame, T.A.; Rushing, J.A. A production-based method for direct estimation of gas-in-place and reserves. In Proceedings of the SPE Eastern Regional Meeting, Morgantown, WV, USA, 14–16 September 2005; SPE: Morgantown, WV, USA, 2005; p. SPE-98042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ilk, D.; Perego, A.; Rushing, J.; Blasingame, T. Integrating multiple production analysis techniques to assess tight gas sand reserves: Defining a new paradigm for industry best practices. In Proceedings of the SPE Unconventional Resources Conference/Gas Technology Symposium, Calgary, AB, Canada, 16–19 June 2008; SPE: Calgary, AB, Canada, 2008; p. SPE-114947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fetkovich, M. Decline Curve Analysis Using Type Curves. J Pet. Technol. 1980, 32, 1065–1077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carter, R.D. Type Curves for Finite Radial and Linear Gas-Flow Systems: Constant-Terminal-Pressure Case. SPE J. 1985, 25, 719–728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blasingame, T.A.; Lee, W.J. Variable-Rate Reservoir Limits Testing. In Proceedings of the Permian Basin Oil and Gas Recovery Conference, Midland, TX, USA, 13–14 March 1986; SPE: Midland, TX, USA, 1986; p. SPE-15028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fraim, M.L.; Wattenbarger, R.A. Gas Reservoir Decline-Curve Analysis Using Type Curves with Real Gas Pseudopressure and Normalized Time. SPE Form. Eval. 1987, 2, 671–682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blasingame, T.A.; Johnston, J.L.; Lee, W.J. Type-Curve Analysis Using the Pressure Integral Method. In Proceedings of the SPE California Regional Meeting, Bakersfield, CA, USA, 5–7 April 1989; SPE: Bakersfield, CA, USA, 1989; p. SPE-18799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blasingame, T.; McCray, T.; Lee, W. Decline curve analysis for variable pressure drop/variable flowrate systems. In Proceedings of the SPE Unconventional Resources Conference/Gas Technology Symposium, Houston, TX, USA, 22–24 January 1991; SPE: Houston, TX, USA, 1991; p. SPE-21513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palacio, J.; Blasingame, T. Decline-curve analysis using type curves-analysis of gas well production data. In Proceedings of the SPE Joint Rocky Mountain Regional and Low Permeability Reservoirs Symposium, Denver, CO, USA, 26–28 April 1993; SPE: Denver, CO, USA, 1993; p. SPE-25909. [Google Scholar]

- Al-Hussainy, R.; Ramey, H., Jr.; Crawford, P. The flow of real gases through porous media. J. Pet. Technol. 1966, 18, 624–636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Callard, J.; Schenewerk, P. Reservoir performance history matching using rate/cumulative type-curves. In Proceedings of the SPE Annual Technical Conference and Exhibition, Dallas, TX, USA, 22–25 October 1995; SPE: Dallas, TX, USA, 1995; p. SPE-030793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agarwal, G.R.; Gardner, D.C.; Kleinsteiber, S.W.; Fussel, D.D. Analyzing Well Production Data Using Combined-Type-Curve and Decline-Curve Analysis Concept. SPE Reserv. Eval. Eng. 1999, 2, 478–486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mattar, L.; McNeil, R. The “flowing” gas material balance. J. Can. Pet. Technol. 1998, 37, PETSOC-98-02-06. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mattar, L.; Anderson, D.; Stotts, G. Dynamic material balance-oil-or gas-in-place without shut-ins. J. Can. Pet. Technol. 2006, 45, PETSOC-2005-113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beohar, A.; Verma, S.; Sabharwal, V.; Kumar, R.; Shankar, P.; Gupta, A. Integrating pressure transient and rate transient analysis for eur estimation in tight gas volcanic reservoirs. In Proceedings of the SPE Oil and Gas India Conference and Exhibition, Mumbai, India, 4–6 April 2017; SPE: Mumbai, India, 2017; p. SPE-185376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solomon, S.; Bureau-Cauchois, G.; Ahmed, N.; Aarnes, J.; Holtedahl, P. CO2 storage capacity assessment of deep saline aquifers in the Mozambique Basin. Energy Procedia 2014, 63, 5266–5283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sasol. Mozambique PVT Analysis: Gas Reservoirs; Memorandum; Sasol: Maputo, Mozambique, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Oden, R.; Jennings, J. Modification of the cullender and smith equation for more accurate bottomhole pressure calculations in gas wells. In Proceedings of the SPE Permian Basin Oil and Gas Recovery Conference, Midland, TX, USA, 10–11 March 1988; SPE: Midland, TX, USA, 1988; p. SPE-17306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gray, H. Vertical Flow Correlation in Gas Wells, User’s Manual for API 14B Surface Controlled Subsurface Safety Valve Sizing Computer Program; American Petroleum Institute: Dallas, TX, USA, 1978. [Google Scholar]

- Duns, H., Jr.; Ros, N. Vertical flow of gas and liquid mixtures in wells. In Proceedings of the World Petroleum Congress, Frankfurt, German, 19–26 June 1963; WPC: Frankfurt, German, 1963; p. WPC-10132. [Google Scholar]

- Reinicke, K.; Remer, R.; Hueni, G. Comparison of measured and predicted pressure drops in tubing for high-water-cut gas wells. SPE Prod. Eng. 1987, 2, 165–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dranchuk, P.; Abou-Kassem, H. Calculation of Z factors for natural gases using equations of state. J. Can. Pet. Technol. 1975, 14, PETSOC-75-03-03. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, A.L.; Gonzalez, M.H.; Eakin, B.E. The viscosity of natural gases. J. Pet. Technol. 1966, 18, 997–1000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ilk, D.; Anderson, D.M.; Stotts, G.W.; Mattar, L.; Blasingame, T.A. Production-Data Analysis—Challenges, Pitfalls, Diagnostics. SPE Res. Eval. Eng. 2010, 13, 538–552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kabir, C.; Izgec, B. Diagnosis of reservoir compartmentalization from measured pressure/rate data during primary depletion. J. Pet. Sci. Eng. 2009, 69, 271–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Medina Tarrazzi, T.M. Characterization of Gas Condensate Reservoirs Using Pressure Transient and Production Data-Santa Barbara Field, Monagas, Venezuela. Ph.D. Thesis, Texas A&M University, College Station, TX, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- IHS Markit Ltd. Water-Gas Ratio (WGR)–Stable Behavior. 2020. Available online: https://www.ihsenergy.ca/support/documentation_ca/Harmony/content/html_files/reference_material/general_concepts/data_diag_flowchart/4-wgr_water_rate.htm#WGR-stable (accessed on 12 August 2025).

- Danesh, A. 1-Phase Behaviour Fundamentals. In PVT and Phase Behaviour of Petroleum Reservoir Fluids; Developments in Petroleum Science; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 1998; Volume 47, pp. 1–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, Q.; Jia, Y.; Liu, P.; Hu, X.; Hao, S. Rate transient analysis methods for water-producing gas wells in tight reservoirs with mobile water. Energy Geosci. 2024, 5, 100251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, C.; Jamiolahmady, M. An equivalent single phase approach to production data analysis in gas condensate reservoirs. J. Nat. Gas Sci. Eng. 2020, 76, 103162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Behmanesh, H.; Hamdi, H.; Clarkson, C.R. Production data analysis of gas condensate reservoirs using two-phase viscosity and two-phase compressibility. J. Nat. Gas Sci. Eng. 2017, 47, 47–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arabloo, M.; Sureshjania, M.H.; Gerami, S. A new approach for analysis of production data from constant production rate wells in gas condensate reservoirs. J. Nat. Gas Sci. Eng. 2014, 21, 725–731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mattar, L.; Anderson, D.M. A systematic and comprehensive methodology for advanced analysis of production data. In Proceedings of the SPE Annual Technical Conference and Exhibition, Denver, CO, USA, 14–16 October 2003; SPE: Denver, CO, USA, 2003; p. SPE-84472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roozshenas, A.A.; Hematpur, H.; Abdollahi, R.; Esfandyari, H. Water production problem in gas reservoirs: Concepts, challenges, and practical solutions. Math. Probl. Eng. 2021, 2021, 9075560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Reservoir | OGIP (Bscf) | Gp (Bscf) | GIP (Bscf) | EUR (Bscf) 1 | RF (%) 2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| G9A | 1099.88 | 763.80 | 336.08 | 966.79 | 79.00 |

| G9B | 341.80 | 243.02 | 98.78 | 324.37 | 74.92 |

| TEast | 134.70 | 66.19 | 68.50 | 114.09 | 58.02 |

| ∑ | 1576.38 | 1073.01 | 503.37 | 1405.25 | ...... |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Ubisse, B.; Sugai, Y.; Bila, A.; Macie, C. The Application of Rate Transient Analysis for the Production Performance Evaluation of the Temane Gas Field–Mozambique: The Use of the Per-Well Basis Approach. Energies 2026, 19, 291. https://doi.org/10.3390/en19020291

Ubisse B, Sugai Y, Bila A, Macie C. The Application of Rate Transient Analysis for the Production Performance Evaluation of the Temane Gas Field–Mozambique: The Use of the Per-Well Basis Approach. Energies. 2026; 19(2):291. https://doi.org/10.3390/en19020291

Chicago/Turabian StyleUbisse, Bartolomeu, Yuichi Sugai, Alberto Bila, and Carlos Macie. 2026. "The Application of Rate Transient Analysis for the Production Performance Evaluation of the Temane Gas Field–Mozambique: The Use of the Per-Well Basis Approach" Energies 19, no. 2: 291. https://doi.org/10.3390/en19020291

APA StyleUbisse, B., Sugai, Y., Bila, A., & Macie, C. (2026). The Application of Rate Transient Analysis for the Production Performance Evaluation of the Temane Gas Field–Mozambique: The Use of the Per-Well Basis Approach. Energies, 19(2), 291. https://doi.org/10.3390/en19020291