1. Introduction

Overheating in residential buildings has become a growing issue in the UK [

1]. This problem is largely driven by climate change, the urban heat island effect, increased airtightness in modern dwellings, and inadequate ventilation design [

1,

2,

3,

4,

5]. Research indicates that overheating has become widespread in homes across England, with indoor temperatures frequently rising above 25 °C, creating risks for occupants’ comfort, health, and productivity [

1]. To address this challenge, adequate ventilation is essential to remove excess heat and maintain comfortable indoor conditions. Ventilation in buildings can generally be categorized as natural, mechanical, or hybrid, depending on the design approach. Mechanical ventilation systems that are often used to manage indoor air quality and overheating consume about 40 per cent of a building’s electricity and contribute considerably to greenhouse gas emissions [

6]. With rising energy costs and growing pressure to achieve net-zero carbon targets [

7,

8], natural ventilation is increasingly recognized as an effective passive strategy to lower energy consumption and environmental impact [

9]. Stack-driven ventilation is particularly important in dwellings where mechanical systems are either impractical or costly, and where passive strategies provide a low-energy way to mitigate overheating [

10].

Among the two principal forms of natural ventilation—wind-driven and stack-driven—the stack effect is regarded as particularly effective [

10,

11]. It operates through temperature-induced buoyancy, where warm air rises and exits through upper openings while cooler air is drawn in from lower ones [

11]. Previous studies have examined stack-driven ventilation using theoretical, numerical, and experimental approaches. In a case study of a library building, researchers explored the transition from passive ventilation to a hybrid system. Initially, the natural system was supplemented with heating, which proved effective during transitional seasons, such as spring and autumn. However, after implementing design and construction modifications, the building was able to rely solely on stack ventilation to maintain adequate indoor air quality, even with increased occupancy [

12].

Stack ventilation is influenced by outdoor thermal conditions and is highly sensitive to both wind speed and direction. Since wind behavior is unpredictable, its impact on airflow is difficult to quantify and can either enhance or interfere with buoyancy-driven ventilation [

13]. However, studies have also shown that stack-driven ventilation can remain effective even when the temperature difference between indoor and outdoor air falls below 12 °C [

14].

Further research has demonstrated that passive stack ventilation can perform effectively in retrofitted apartment buildings. Simulations of a five-story building revealed that the system could provide adequate air exchange, especially when windows were used together with the stack. The system’s performance was affected by the quality of maintenance, while improved airtightness did not improve the results. Although the study was conducted in a northern European setting, its importance lies in the fact that it excluded wind influence and clearly demonstrated how stack ventilation works effectively when combined with openable windows [

15].

Complementing this body of work, a recent field study conducted in a semi-detached house showed that acceptable indoor air quality could be maintained throughout the year, despite increased window airtightness and in the absence of mechanical ventilation. Stack ventilation played a significant role, particularly during colder periods, although wind-driven airflow often dominated. These findings reinforce the viability of passive ventilation strategies in low-energy dwellings, provided that local climatic and airflow dynamics are accounted for [

16].

Despite the extensive research into stack ventilation and its recognized benefits for indoor air quality and energy efficiency, there remains a shortage of full-scale empirical research conducted under real-world conditions. A recent systematic review identified only 35 high-quality studies out of more than 300, with most lacking in situ experimental validation, particularly for medium-rise residential buildings [

10]. Much of the existing work has focused on wind-assisted or hybrid systems, while scenarios driven purely by thermal buoyancy—without wind effects—have received little attention. Experimental studies that do exist often rely on idealized test environments or simplified prototypes, limiting their applicability. Full-scale experiments have shown that buoyancy-driven airflow can differ substantially between window types under controlled wind-free conditions [

17]. In addition, although several predictive formulas are available in the literature, their performance under controlled, wind-free conditions has rarely been evaluated against actual measurements.

Given these challenges, the present study investigates buoyancy-driven natural ventilation under wind-free conditions in a full-scale dwelling, The Future Home (TFH), located within the Energy House 2.0 research facility. The experiments were conducted without mechanical ventilation in a controlled laboratory environment, where notable indoor–outdoor temperature differences were established to simulate overheating conditions. Airflow was determined using standard stack-effect equations and verified through on-site velocity measurements obtained with hot-wire anemometers. By comparing theoretical predictions with measured results, this study assesses the accuracy of simplified estimation methods and identifies the factors that affect the correspondence between modeled and actual performance. The findings help enhance ventilation modeling within the UK context and reinforce the role of passive design strategies in mitigating overheating in future housing developments. Furthermore, assessing the energy implications of buoyancy-driven ventilation offers practical insight into reducing dependence on mechanical systems during overheating events in dwellings comparable to TFH.

This article will investigate the following two main research questions:

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Experimental Facility

The experiment was conducted in Energy House 2.0 (

Figure 1), a controlled research facility at the University of Salford designed to study the performance of full-scale dwellings under reproducible environmental conditions [

18].

Energy House 2.0 is a one-of-a-kind facility for testing the performance of buildings under precisely controlled environmental conditions. Designed for full-scale experimentation, it consists of two large climatic chambers, each capable of housing two full-size family homes (four in total).

Each chamber includes soil-filled test pits 1200 mm deep, thermally isolated from the surrounding ground by continuous insulation. The walls and ceilings are also highly insulated, ensuring complete separation from external weather and maintaining exceptional airtightness.

Every chamber is independently managed by a dedicated heating, ventilation, and air-conditioning (HVAC) system. To replicate diverse weather scenarios, weather controls are deployed to modulate key parameters, such as temperature, humidity, and wind speed, enabling precise control of test conditions as follows:

Temperature: (−24 °C to 51 °C);

Relative Humidity (20% to 90%);

Wind (up to ~17 m/s);

Rain (up to 200 mm/h);

Solar Radiation (up to 1200 W/m2);

Snow (up to 250 mm per day).

Temperature and relative humidity can be held at a constant steady state or varied in seasonal or daily patterns.

TFH is located within this facility and is a two-story detached house constructed to meet the specifications of a typical modern UK dwelling, aligned to Future Homes Standard. It provides a realistic domestic layout while allowing precise control of temperature and humidity inside a sealed climatic chamber.

The experiments were carried out in two phases: Phase 1, which involved the investigation of airflow from natural ventilation, and Phase 2, which involved the investigation of cooling energy from natural ventilation.

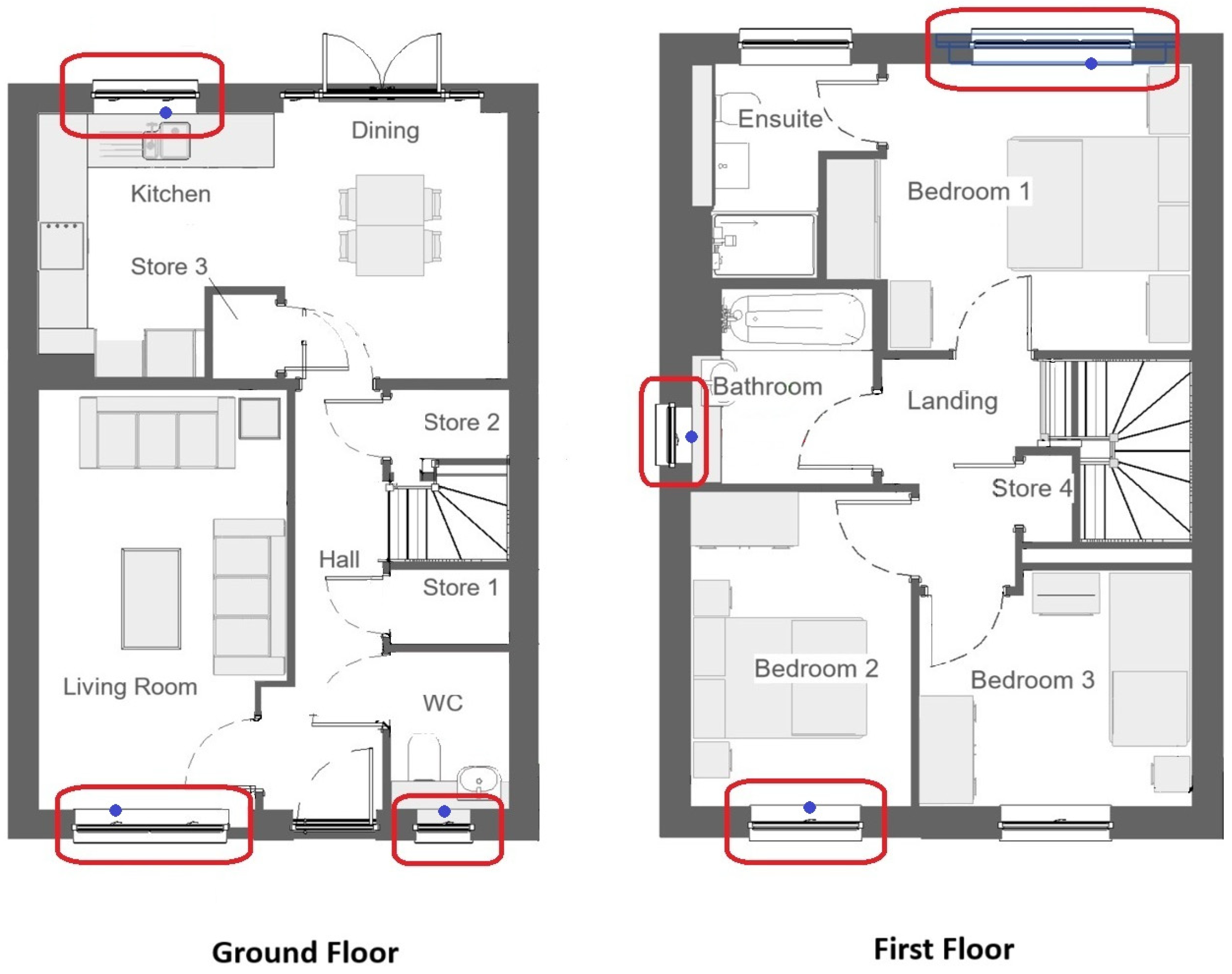

2.2. Phase 1—Investigation of Airflow from Natural Ventilation

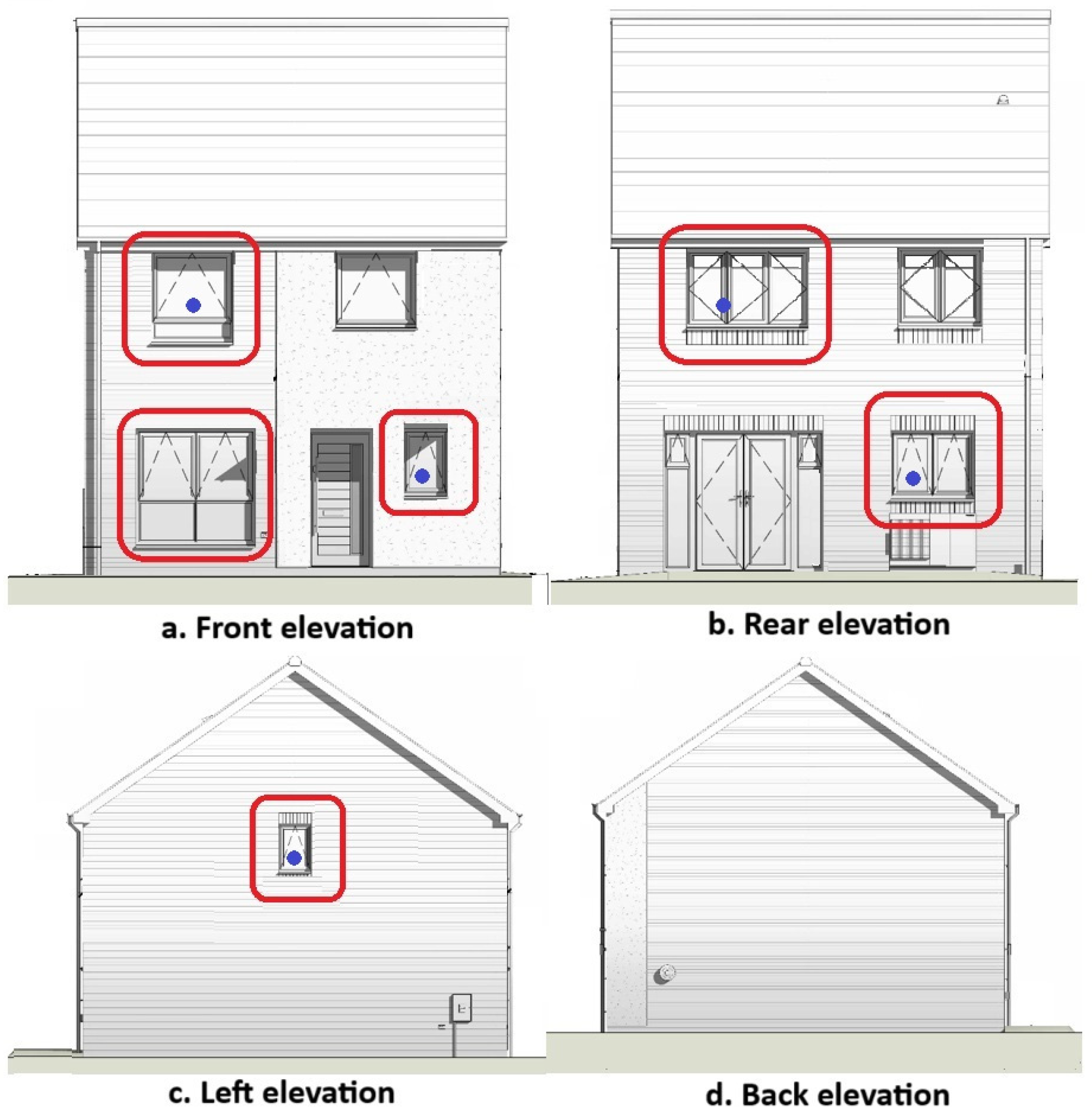

TFH contains a total of eight windows—three on the ground floor and five on the first floor. For this experiment, six windows were selected: three on the ground floor and three on the first floor, each positioned on different façades to create a vertical airflow path through the building. The windows were selected to maintain comparable airflow characteristics between the two levels and to form a balanced stack-driven ventilation configuration, with the ground-floor openings acting as inlets and the first-floor openings acting as outlets. The remaining two windows were excluded to preserve this balanced inlet–outlet arrangement and to remain consistent with the six-channel velocity measurement setup available for the experiment. The locations of the selected openings are shown in

Figure 2 and

Figure 3, which present the floor plans and elevations of TFH, respectively. The positions of the hot-wire velocity probes are indicated schematically by blue circles adjacent to each monitored window.

It was planned that air velocity and temperature would be monitored throughout the test to evaluate buoyancy-driven airflow. Accordingly, the velocity sensors were installed adjacent to these openings. Further details regarding the installation and configuration of the sensors are provided in

Section 2.2.1. After the installation and calibration of all measurement instruments, the indoor air temperature in TFH gradually increased to approximately 35 °C using the heating system, while the surrounding chamber air was maintained at a temperature of approximately 15 °C with a relative humidity of approximately 79%. Once this steady temperature difference was achieved, the selected windows were opened simultaneously to initiate buoyancy-driven airflow. At the instance the windows were opened, all rooms were at approximately 35 °C, consistent with the experimental setup. Following the window opening, indoor temperatures began to decrease due to buoyancy-driven ventilation. The indoor temperatures reported later in the analysis, therefore, represent hourly mean values measured after window opening rather than the initial setpoint. All theoretical and experimental comparisons in this study are based on the measured indoor and outdoor temperatures rather than the chamber setpoint. The test was conducted over 24 h to capture a full-day ventilation cycle under stable thermal conditions. During this period, all mechanical ventilation systems were kept off, and all internal doors were open to allow free air movement between floors, ensuring that airflow was driven solely by stack-effect forces.

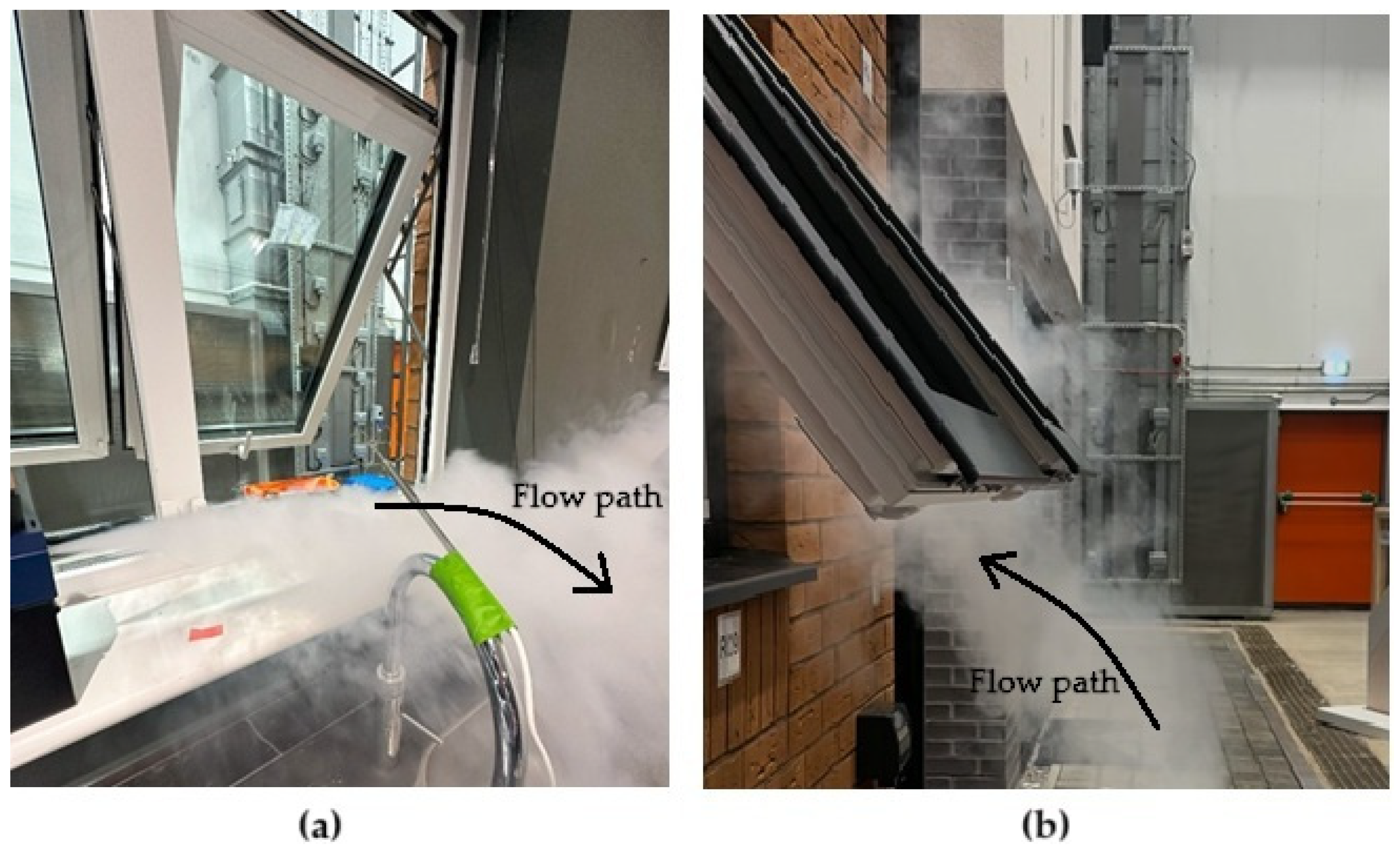

Air velocity was continuously recorded at the six selected window openings. Indoor and outdoor temperatures were monitored throughout the test using the facility’s Environmental Monitoring System (Campbell Scientific, Logan, UT, USA) to confirm the temperature differential. A smoke visualization test was also performed at the start of the experiment to verify airflow direction and confirm inflow and outflow through the openings.

2.2.1. Measurement Instruments and Setup

Air velocity was measured using a KIMO C310 multifunction transmitter (Sauermann Group, Montpon, France) with six SVO omnidirectional hot-wire anemometer probes. These sensors provide high accuracy for low-velocity natural ventilation flows [

19,

20]. For each window, a single probe was installed 0.16 m above the windowsill and 0.19 m from the inner surface of each opening, ensuring uniform probe placement across all windows. The use of a single-point velocity measurement represents a known methodological limitation. Velocity profiles across window openings, particularly for top-hung windows, are inherently non-uniform. Of the six monitored windows, five were top-hung, while one opening (Bedroom 1) had a different configuration, as shown in

Figure A1. For the top-hung windows, the probe was positioned approximately near the centroid of the dominant flow region, where airflow was expected to be most representative, based on preliminary smoke visualization. To maintain consistency across all measurements, the same vertical probe height (0.16 m above the sill) was also applied to the non-top-hung window, even though an alternative placement could have been considered. This approach was adopted to ensure comparability between openings and to avoid introducing additional variability due to probe positioning. The single-probe strategy was selected primarily due to practical constraints, including the limited number of available sensors and the cost associated with deploying multiple probes per opening. The implications of this limitation, including its expected influence on the inflow–outflow balance, are considered in the uncertainty analysis and further discussed in

Section 4.2.

Each probe was connected to a multi-channel data logger (Campbell Scientific, Shepshed, UK) that recorded one-minute averages throughout the 24 h test period. Logger channels were labeled to match each corresponding window opening.

As the test house is a highly insulated dwelling with very low leakage, any remaining infiltration paths were considered negligible compared to the measured window flows.

The KIMO SVO probes used in this study have a stated accuracy of ±3% of the measured value ±0.05 m/s, which was adopted as the measurement uncertainty in the analysis.

The main instruments and sensors used in the experimental testing are summarized in

Table 1.

2.2.2. Theoretical Framework and Calculations

The theoretical airflow rate was calculated using the buoyancy-driven orifice equation recommended in CIBSE AM10 and BS EN 5925 [

19,

20]. This relationship expresses the volumetric airflow rate as a function of the effective opening area, discharge coefficient, indoor–outdoor temperature difference, and the vertical separation between openings:

where

Qb is the buoyancy-driven airflow rate (m

3/s),

Cd is the discharge coefficient (–),

g is gravitational acceleration (9.81 m/s

2),

ha is the vertical distance between the midpoints of the openings (m), Δ

t is the temperature difference between indoor and outdoor air (°C),

is the mean temperature (°C), and

Ab is the effective opening area of the flow path (m

2), calculated using the inverse-square relationship of:

and where

A1,

A2,

A3,

A4 = free areas of individual openings (m

2)

In Equation (1), Cd, Ab, and ha are the key parameters requiring close attention, as their accuracy directly affects the calculated airflow rate.

The discharge coefficient (

Cd) represents the ratio between the actual airflow through an opening and the theoretical flow that would occur in the absence of losses, accounting for friction, turbulence, and flow contraction effects [

19,

24]. While its definition is straightforward, determining an appropriate value for

Cd is complex because it depends on the geometry and flow conditions of the openings. For sharp-edged window openings under buoyancy-driven flow, most experimental and design studies recommend

Cd values between 0.6 and 0.65 [

20,

25,

26]. In this study, a constant value of 0.6 was adopted, consistent with established guidance and previous full-scale experiments on medium-sized openings operating under natural-ventilation conditions.

The effective opening area (

Ab) refers to the portion of a window through which air passes during natural ventilation. Its size depends on the window type and geometry. For example, side-hung sashes create rectangular flow paths, while top-hung windows form a triangular area due to their tilt. The effective area represents the true airflow section, considering the effects of frames, sash position, and contraction losses [

20,

25].

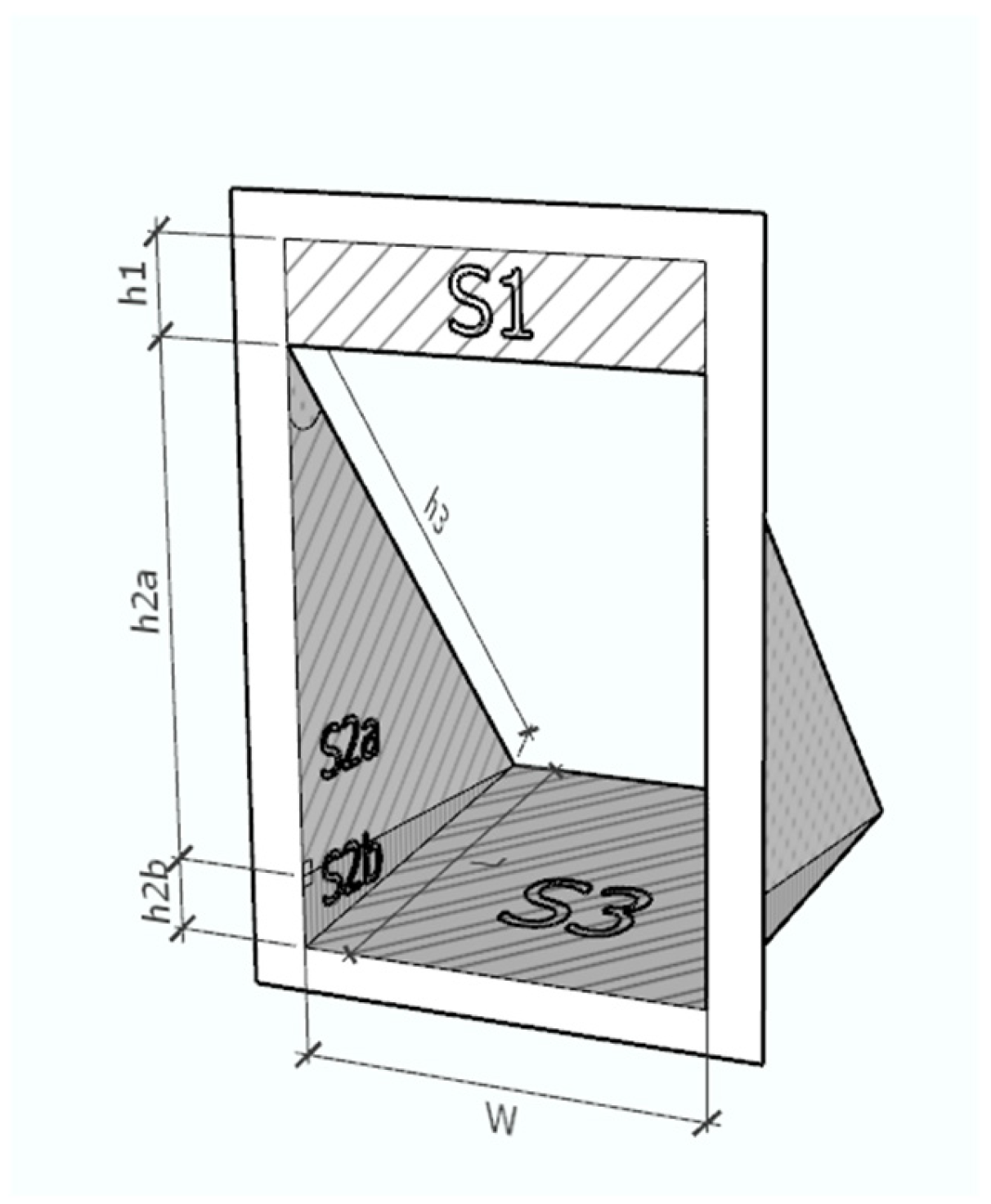

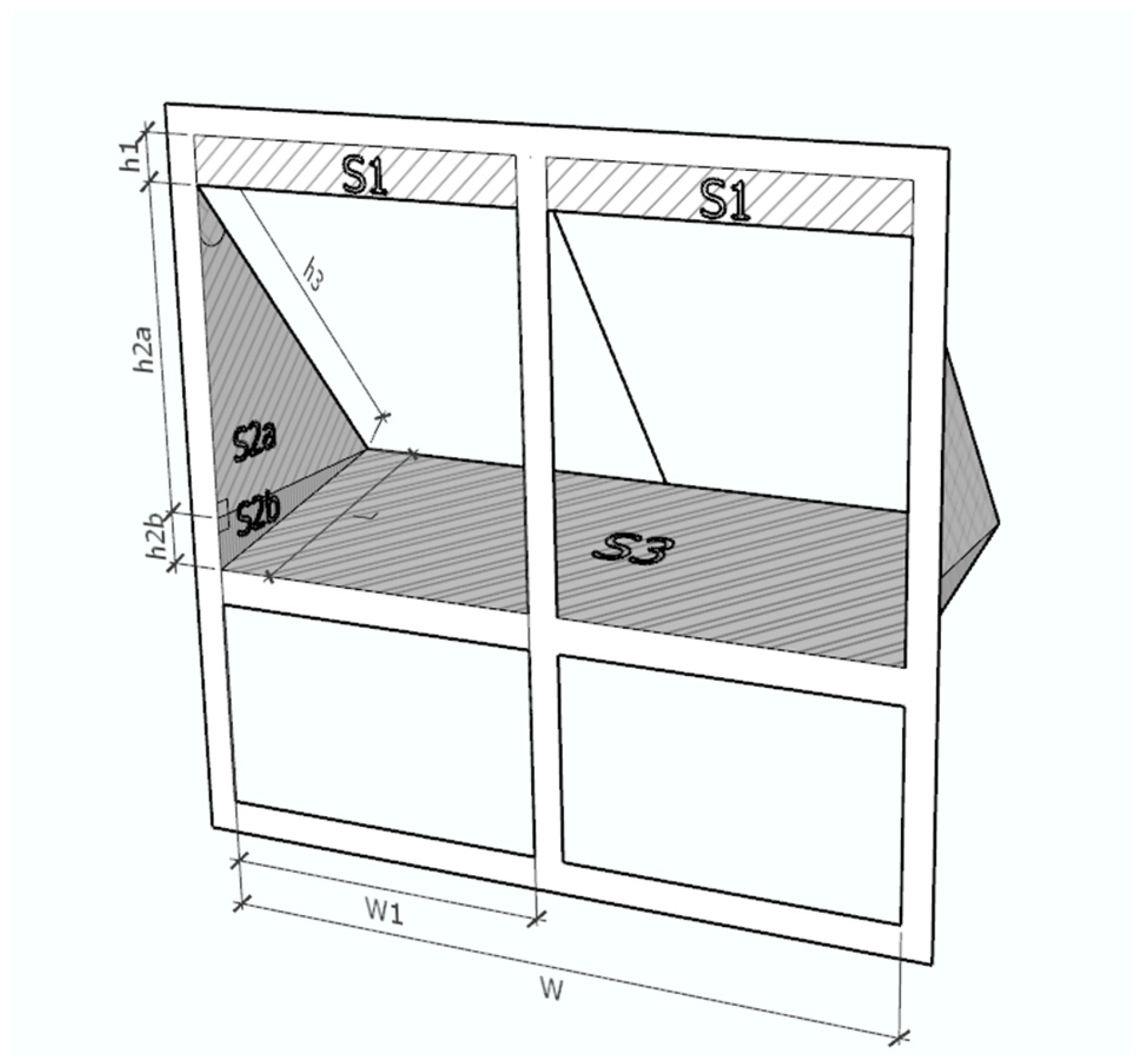

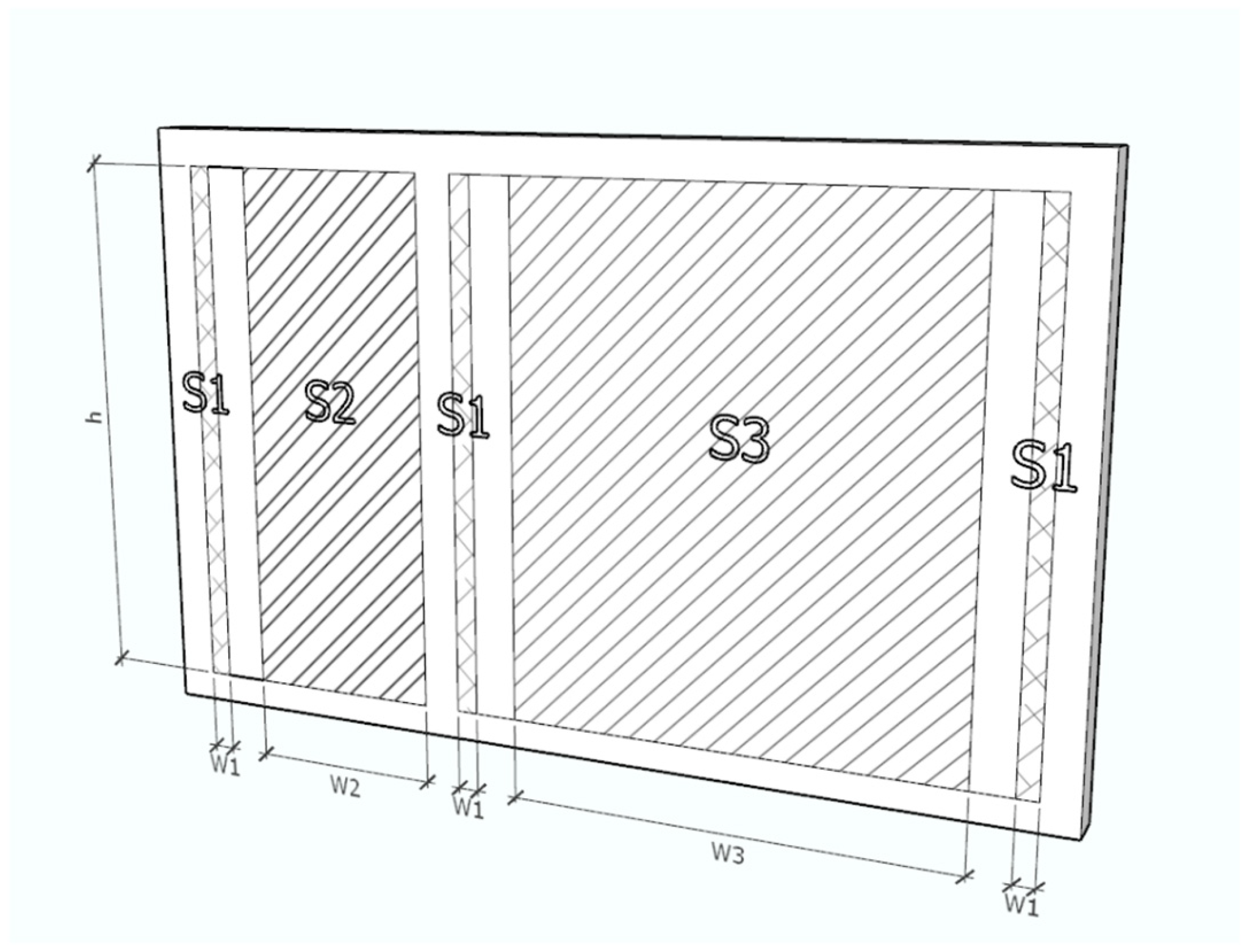

In this study, the openable areas of all selected windows were measured directly on site under test conditions. To obtain accurate values, the windows were grouped into three types: top-hung windows without a central mullion (bathroom and WC), top-hung windows with a central mullion (kitchen and living room), and side-hung windows (bedroom 1). Each window opening was subdivided into smaller geometric sections based on its tilt and shape, and the total openable area was obtained by summing these components. This method aligns with established geometric approaches for determining the effective flow area of real windows under buoyancy-driven ventilation [

26,

27]. Detailed window configurations and dimensions, as well as the classification and geometric procedure used for calculating the free opening areas, are presented in

Appendix A.1 (

Figure A1) and

Appendix A.2 (

Figure A2,

Figure A3 and

Figure A4).

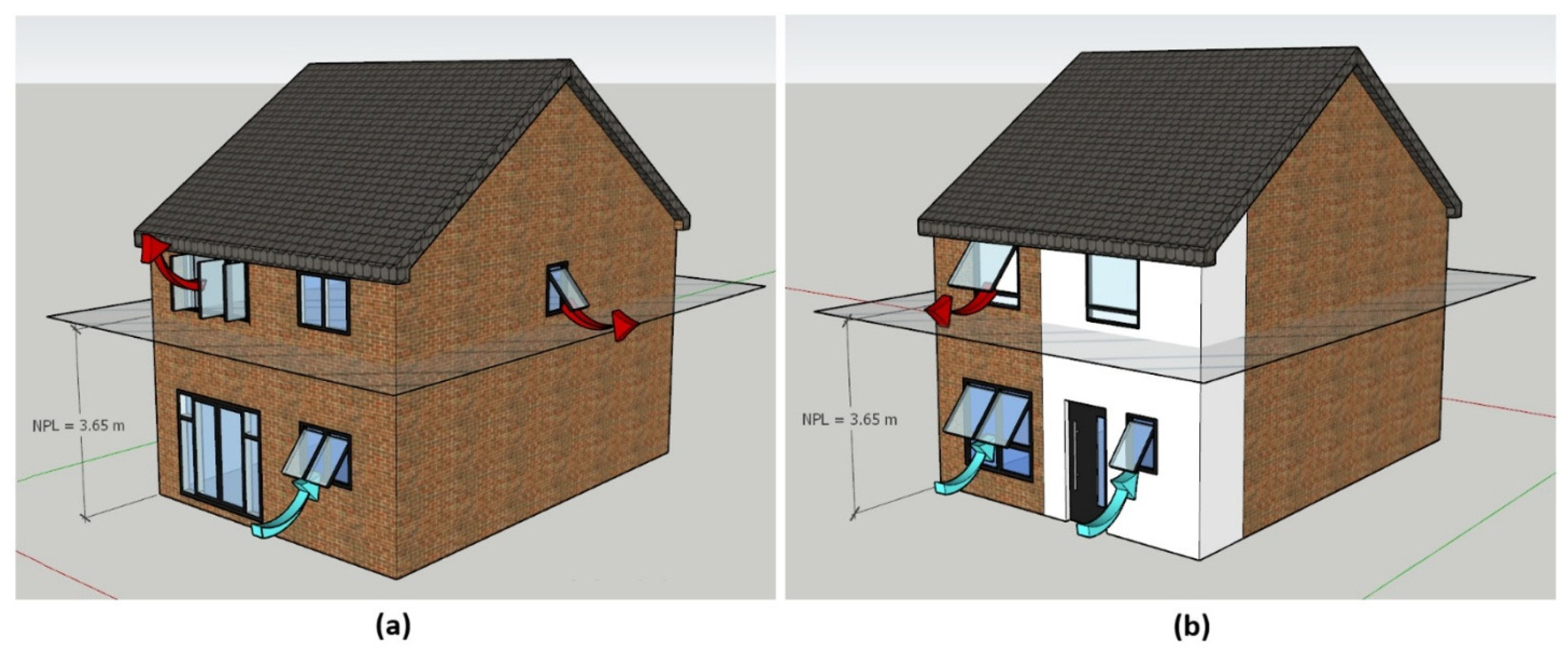

In stack-driven ventilation, the airflow direction and rate depend strongly on the position of the Neutral Pressure Level (NPL), the height at which indoor and outdoor pressures are equal [

20]. Openings below this level act as inlets, while those above it serve as outlets, defining the effective pressure difference driving the buoyancy flow [

28]. The NPL location varies with the geometry and relative size of openings and is therefore essential for determining the correct vertical height used in the buoyancy-driven equation.

The NPL height (

HNPL) was calculated following the weighted-average approach described by [

27], which assumes steady-state flow where total inflow equals total outflow (

Qin =

Qe). It is expressed as:

where

HNPL is the height of the NPL above a reference point, usually the base of the building,

Ai is the free area of the

i-th opening (m

2), and

hi is the height of the centroid of the

i-th opening above the same reference point (m). The

HNPL for TFH was approximately 3.65 m above the ground floor reference level.

Figure 4 presents schematic front, rear, and left elevations of TFH, showing the calculated NPL and the corresponding airflow directions through the window openings.

To determine the total buoyancy-driven airflow, the openings were grouped into two zones: ground-floor inlets and first-floor outlets. Because the vertical distances between individual windows were not identical, the centroid height of each opening was calculated separately using the area-weighted mean of its subsections. The vertical separation between each lower–upper pair of openings was then obtained from the difference between their centroid heights. All possible lower–upper combinations were analyzed, and the average vertical distance between them was taken as the representative ha in the buoyancy-driven airflow equation.

2.2.3. Experimental Data Analysis

Logger outputs were converted from voltage to air velocity using the instrument’s defined range. One-minute readings were then averaged to hourly mean velocities for each opening.

Volumetric airflow through each window was computed from Equation (4) [

26].

where

Q is the volumetric airflow rate (m

3/s),

A is the measured free opening area of the window (m

2), and

is the corresponding hourly mean air velocity (m/s). The free opening areas (A) used in this equation were taken from the measured window geometries described in

Appendix A. The total inflow and outflow for the dwelling were obtained by summing the window flows on the ground and first floors, respectively. The resulting measured flow rates were later compared with theoretical predictions from Equation (1) to evaluate model accuracy.

2.3. Phase 2—Investigation of Cooling Energy from Natural Ventilation

In addition to airflow measurements, the cooling energy provided by natural ventilation was evaluated to quantify its potential contribution to reducing indoor air temperature under overheating conditions. This assessment aimed to estimate the sensible cooling effect generated by the buoyancy-driven air exchange between indoor and outdoor environments.

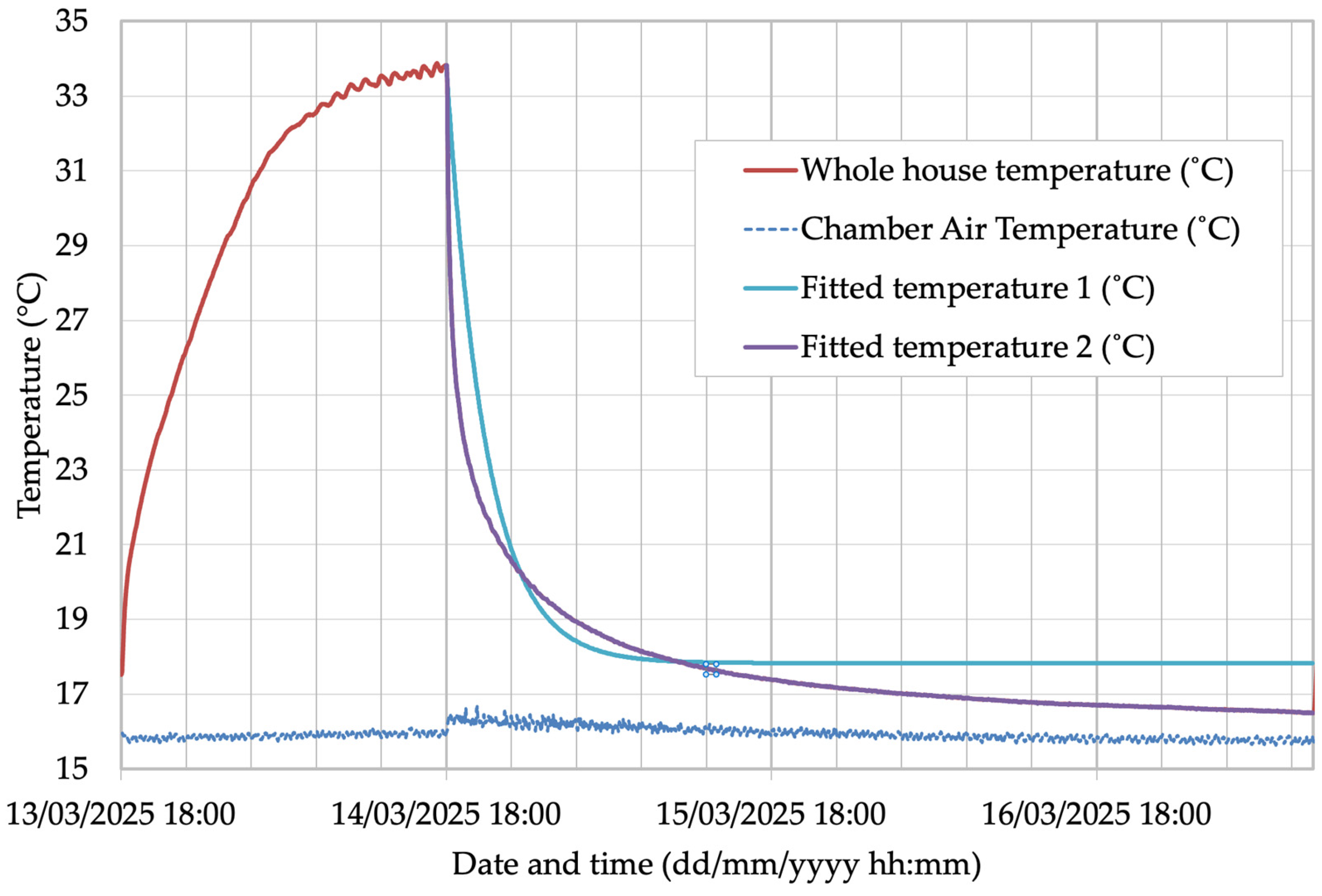

In this phase of the test, the internal temperature was set to circa 33 °C, and the outside (chamber) temperature was set to 16 °C. At the start of the test, internal heaters were switched off, and all windows were opened simultaneously. A mid-point room air temperature was recorded in each room, and an area-weighted whole house temperature was calculated as follows:

where

Ai—floor areas of individual spaces;

Ti—air temperatures of individual spaces;

n—total number of individual spaces.

Subsequently, Equation (6) was used [

29], to characterize the internal air temperature in the building as follows:

where

Tr—Internal room temperature at time t;

Tr,o—Internal room temperature at time zero when heat input started;

Ta—External air temperature;

Qint—Internal heat gain;

Qsol—Solar gain;

HTC—Heat transfer coefficient;

t—Time;

tc—Time constant.

As the experiment was conducted in an environmental chamber under controlled conditions without solar radiation, Equation (6) was modified accordingly as follows:

and

Qint was subsequently obtained from curve-fitting of Equation (7) to the measured data.

4. Discussion

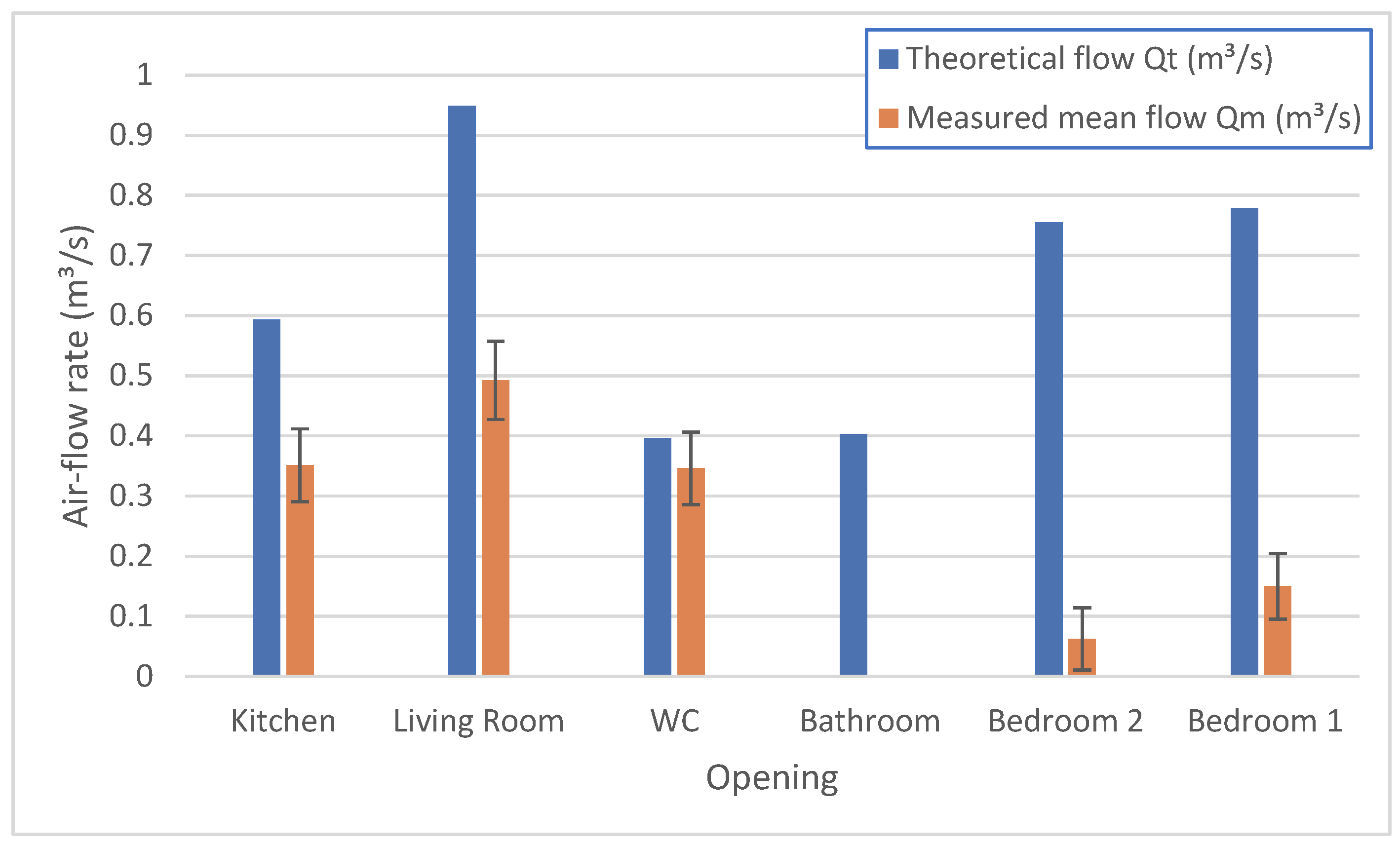

4.1. Variation in Airflow Performance Across Openings

The analysis of the measured data provides insight into airflow behavior across different openings and floor levels during the buoyancy-driven ventilation test. Recorded velocities decreased during the initial hours after window opening and then remained relatively steady throughout the monitoring period. This reduction was less pronounced than expected, most likely because the heating system remained active, maintaining buoyancy forces through a stable indoor-outdoor temperature difference.

At the individual opening level, the WC window consistently exhibited the highest velocities, starting at approximately 0.7 m/s before stabilizing between 0.4 m/s and 0.5 m/s. The kitchen and living room followed similar patterns, both settling around 0.25–0.35 m/s after the initial decline.

For the first-floor openings, Bedroom 1 recorded slightly higher velocities than Bedroom 2, but both remained within a similar range of approximately 0.1 m/s. Their consistent behavior reflects weaker driving forces near the upper part of the building, where pressure differences are smaller. When grouped by floor level, a clear trend was observed: downstairs openings exhibited substantially higher velocities than those upstairs.

Considering airflow rates, which account for both velocity and opening area, the living room dominated total ventilation due to its larger free area, even though its velocities were moderate. In contrast, the WC, despite having the highest velocities, generated smaller flow rates because of its smaller opening size. The kitchen’s results lay between these two, narrowing the difference with the WC compared to the velocity-only analysis.

The difference between the two upstairs rooms became more evident once airflow, rather than velocity, was examined. Although their velocities were relatively close, the slightly larger bedroom 1 opening area amplified the disparity in volumetric flow. This demonstrates the sensitivity of stack ventilation to window geometry and highlights the importance of accurately determining free opening areas.

The persistence of relatively high airflow rates throughout the 24 h period indicates the effect of the heating system in maintaining the indoor–outdoor temperature difference and preserving the pressure differentials responsible for airflow. At the group level, the downstairs windows consistently recorded higher airflow rates than the upstairs ones. This is consistent with stack-effect theory, in which inflow occurs at lower levels where pressure differences are greater, while outflow takes place at upper openings where the gradients are smaller [

20]. In principle, however, total volumetric inflow should equal total outflow, as mass balance requires that the air volume entering the building must also leave. The discrepancy observed here likely results from methodological limitations rather than a genuine imbalance in flow.

4.2. Interpretation of Measured and Theoretical Airflow Behavior

The comparison between theoretical and measured airflow rates revealed consistent differences across all monitored openings. As shown in

Figure 7, Q

t derived from the buoyancy-driven orifice equation were consistently greater than Q

m, particularly for the upper-story windows. This indicates that the simplified theoretical model tends to overestimate actual airflow under real domestic conditions. The key factors contributing to the discrepancy between theoretical and measured airflow rates are summarized as follows:

Velocity at each window was measured using a single probe positioned 0.16 m above the lower edge, assuming it represented the average across the entire opening. In practice, velocity distribution is non-uniform, particularly for top-hung windows: inflow accelerates near the bottom, while outflow is typically stronger at the upper edge. The fixed probe height, therefore, likely caused inflow velocities on the ground floor to be slightly overestimated and upper-level outflows to be underestimated, producing a small bias toward higher measured inflow. This bias is expected to be approximate rather than precise, and the resulting inflow–outflow imbalance should therefore be interpreted as indicative rather than exact.

- 2.

Effective opening area uncertainty

The calculation of window opening areas introduced further uncertainty. The top-hung sashes formed multiple slots and triangular sections (S1–S3, see

Figure A2 and

Figure A3). The probe primarily measured air passing through the lower slots, while outflow from the upper slot—potentially with higher velocities—was included in the total calculated area but not fully captured. This mismatch between the measured velocity zone and the assumed total area likely contributed to the observed imbalance between inflow and outflow.

- 3.

Instrument accuracy

Instrument uncertainty also influenced the results. The omnidirectional SVO probe has a stated accuracy of ±3% of the reading ±0.05 m/s, which becomes significant at the low air velocities typical of upper-story outflows.

- 4.

Model assumptions and thermal stratification

Beyond measurement-related effects, model assumptions contributed to the systematic overprediction of airflow. The theoretical calculations assumed uniform indoor and outdoor temperatures, whereas in practice, vertical thermal stratification may have occurred between lower and upper openings. Such stratification would lead to local variations in buoyancy pressure that are not captured by the simplified two-node model. This effect, combined with the use of a fixed discharge coefficient and the idealized steady-flow assumption of the orifice equation, contributed to higher predicted flow rates compared with experimental observations.

Although CFD simulations would facilitate better discussion of the differences from theoretical results, CFD modeling was beyond the scope of this particular phase of research and will be carried out as part of future studies.

Taken together, these findings demonstrate that while the buoyancy-driven orifice model provides a useful first-order approximation, its application to multi-opening domestic buildings requires careful calibration. Accounting for vertical temperature gradients, realistic discharge coefficients, and detailed velocity profiles would significantly enhance the accuracy of future predictive models.

4.3. Back-Calculated Discharge Coefficient (Cd)

The consistent overprediction of theoretical airflow compared with measured values indicated that the assumed discharge coefficient (Cd = 0.6) was higher than the effective value observed under the test conditions. To resolve this discrepancy, a back-calculation was carried out using the buoyancy-driven ventilation equation (Equation (1)) to determine the Cd value that reconciles theoretical predictions with the measured data.

Using Cd = 0.6 and an effective total area of 2.45 m2, the theoretical calculation produced a buoyancy-driven flow of 1.94 m3/s, while the measured total inflow was only 1.19 m3/s. Substituting the measured value into the orifice equation yielded an apparent discharge coefficient of approximately 0.37.

This back-calculated value is considerably lower than the range typically reported for sharp-edged openings (≈0.6 ± 0.1) and suggests that under the specific experimental configuration—multiple top-hung windows, combined inflow–outflow pathways, and non-uniform pressure fields—the effective aerodynamic performance of the openings was reduced. In particular, the presence of top-hung window configurations with central mullions results in tortuous airflow paths and increased effective flow resistance, which reduces the effective discharge coefficient under buoyancy-driven conditions.

The analysis was performed at the whole-building level, consistent with the two-node formulation of the buoyancy model, in which lower and upper openings are aggregated into single inflow and outflow nodes. Estimating Cd for each opening individually would require distinct height separations and flow paths, which are inconsistent with this formulation. Therefore, a system-level interpretation provides a more reliable understanding of discharge behavior under the controlled conditions of this study.

In summary, reconciling the theoretical and measured airflow rates required lowering the assumed discharge coefficient from 0.6 to 0.37, demonstrating that only part of the nominal opening area contributed effectively to the stack-driven ventilation under test conditions.

4.4. Comparison with Previous Studies

The experimental results from TFH were compared with findings from previous full-scale and simulation studies to evaluate their consistency with established research on stack-driven ventilation. Buoyancy-driven ventilation rates reported in earlier experiments under calm conditions ranged between 0.50 and 0.94 m

3/s using tracer gas methods and 0.69–0.83 m

3/s using velocity-based techniques [

28]. In contrast, the measured inflow rate in TFH averaged 1.19 m

3/s, with a peak of 1.67 m

3/s during the first hour after window opening. The higher airflow values observed here can be attributed to the larger indoor–outdoor temperature differences of 15–18 °C and the greater total opening area created by the six simultaneously opened windows, which together enhanced buoyancy forces compared with earlier setups [

28].

Simulation-based studies have also reported comparable results. Numerical analyses using the COMIS model predicted air change rates between 4 and 30 h

−1 (0.04–0.5 m

3/s) depending on room geometry and boundary conditions [

31]. The present experiment produced values ranging from 0.05 to 0.69 m

3/s, which fall within the upper end of this range. The slightly higher flows in this study can be explained by the controlled boundary conditions in TFH, where stable and elevated temperature gradients were maintained throughout the test [

31].

A full-scale field investigation conducted on a residential building equipped with multiple chimneys and a bottom-pivoted tilted window operating under buoyancy forces in a cold climate also reported a similar aerodynamic behavior. In that study, which applied a modified theoretical model developed for single-sided ventilation, the measured discharge coefficient was

Cd = 0.345, indicating reduced flow efficiency compared with typical rectangular openings [

14]. The discharge coefficient calculated in the present study (

Cd = 0.37) is in good agreement with this earlier finding, confirming that the airflow behavior through tilted window openings under stack-driven conditions follows a comparable trend across different experimental contexts. This result aligns with findings showing that the discharge coefficient is not constant but varies significantly with opening size, window type, and temperature difference, and that assuming a fixed Cd can lead to errors in predicting airflow capacity [

26].

Overall, the measured ventilation rates in TFH are consistent with the ranges reported in previous experimental and simulation studies [

14,

28,

31]. The higher airflow rates observed in this study reflect the influence of the controlled boundary conditions within the climatic chamber. The calculated discharge coefficient also shows good agreement with previous full-scale findings on stack-driven ventilation. These results highlight the need to calibrate theoretical models against real-scale data to enhance the accuracy of natural ventilation predictions in residential buildings.

4.5. Cooling-Down Power and Energy from Natural Ventilation

Due to the busy testing schedule at the Energy House 2.0 test facility, the cooling-down tests had to be conducted separately from the air velocity measurement tests for logistical reasons, such as the availability of the test facility and instrumentation.

Although the cooling-down energy of 90.7 kWh indicates a significant contribution from natural ventilation in managing overheating, further studies are necessary to generalize these results. This will involve conducting multiple sequences of heating-up and cooling-down, along with simultaneous air velocity measurements.

4.6. Limitations and Future Work

While the experiment successfully quantified buoyancy-driven ventilation in TFH, several limitations must be acknowledged. Although the study achieved its primary objective of measuring and comparing natural airflow under stack-driven conditions, some methodological and contextual constraints may have influenced the results and should be addressed in future work.

One limitation arises from the asymmetry between the ground- and first-floor window areas, which likely affected airflow distribution and contributed to differences between theoretical and measured results. Future experiments conducted in dwellings with more balanced or symmetrical openings would enable a more accurate assessment of model performance. A staged opening strategy, beginning with one window per floor and progressively increasing to multiple openings, could also help examine how opening configuration influences ventilation performance.

The second limitation relates to measurement resolution. Single-point velocity measurements did not fully capture vertical variations across openings. Employing multiple probes at different heights—particularly for top-hung windows—would improve accuracy and representativeness. Whilst having multiple velocity measurements per window would have been preferable, it was not possible to add more hot-wire sensors due to their significant cost in this phase of this research. Nevertheless, we believe that the current results are a good starting point for future studies.

Further methodological refinements are recommended. Deactivating the heating system once the windows are opened would prevent artificial thermal influence on buoyancy forces, ensuring that temperature differences are driven purely by natural conditions. In addition, using computational fluid dynamics (CFD) modeling or alternative sensor systems would strengthen the reliability of the results and enhance confidence in the experimental findings. Planned CFD studies can be used to resolve three-dimensional velocity and pressure fields within the dwelling, enabling a more detailed investigation of airflow distribution, vertical stratification, and the sources of discrepancy between theoretical predictions and experimental measurements.

This investigation focused on a single case study, limiting the broader applicability of the findings. Future research should extend the analysis to a range of building types and layouts to determine whether discrepancies between measured and theoretical airflow rates are case-specific or indicative of broader limitations in simplified stack-effect models. Future experimental work is also recommended to investigate the interaction between stack-driven ventilation and wind effects, in order to move beyond wind-free laboratory conditions toward more representative real-world residential operating scenarios.

In parallel, further studies will focus on running the experiments multiple times, using arrays of air velocity sensors placed near each window to improve the understanding of window air velocity distribution, as well as running multiple cooling-down sequences to facilitate generalization of power and energy contributions from natural ventilation.

5. Conclusions

This study experimentally investigated buoyancy-driven natural ventilation in a two-story domestic test house within Energy House 2.0. This research compared theoretical predictions from the buoyancy-driven orifice formula with full-scale measured data collected under wind-free conditions. The results demonstrated that stack ventilation can provide significant and stable airflow when a sufficient indoor–outdoor temperature difference is maintained, validating the fundamental principles of natural buoyancy-driven flow in domestic buildings.

However, the comparison between theoretical and measured data revealed that simplified orifice equations systematically overpredict actual airflow rates. The discrepancy was primarily attributed to geometric limitations of top-hung windows, non-uniform velocity distributions, and the use of a fixed discharge coefficient. A back-calculated coefficient of 0.37 was found to better represent the real aerodynamic performance of the tested configuration, emphasizing the need to calibrate theoretical models for multi-opening, domestic-scale applications.

Natural ventilation cooling-down power of 1417 W and energy of 90.7 kWh with all windows open were quantified, improving the understanding of the effectiveness of natural ventilation under the specific test conditions.

Overall, the findings contribute valuable empirical evidence for improving the predictive accuracy of natural ventilation models in low-rise housing. They highlight the importance of considering real boundary conditions, opening geometry, and flow asymmetry in design calculations. The results also support the broader use of buoyancy-driven ventilation as an effective passive strategy for mitigating overheating and reducing reliance on mechanical systems in future low-carbon residential developments.