Wind–Storage Coordinated Control Strategy for Suppressing Repeated Voltage Ride-Through of Units Under Extreme Weather Conditions

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials

2.1. Conventional Control Methods and Frameworks for Wind–Storage Systems

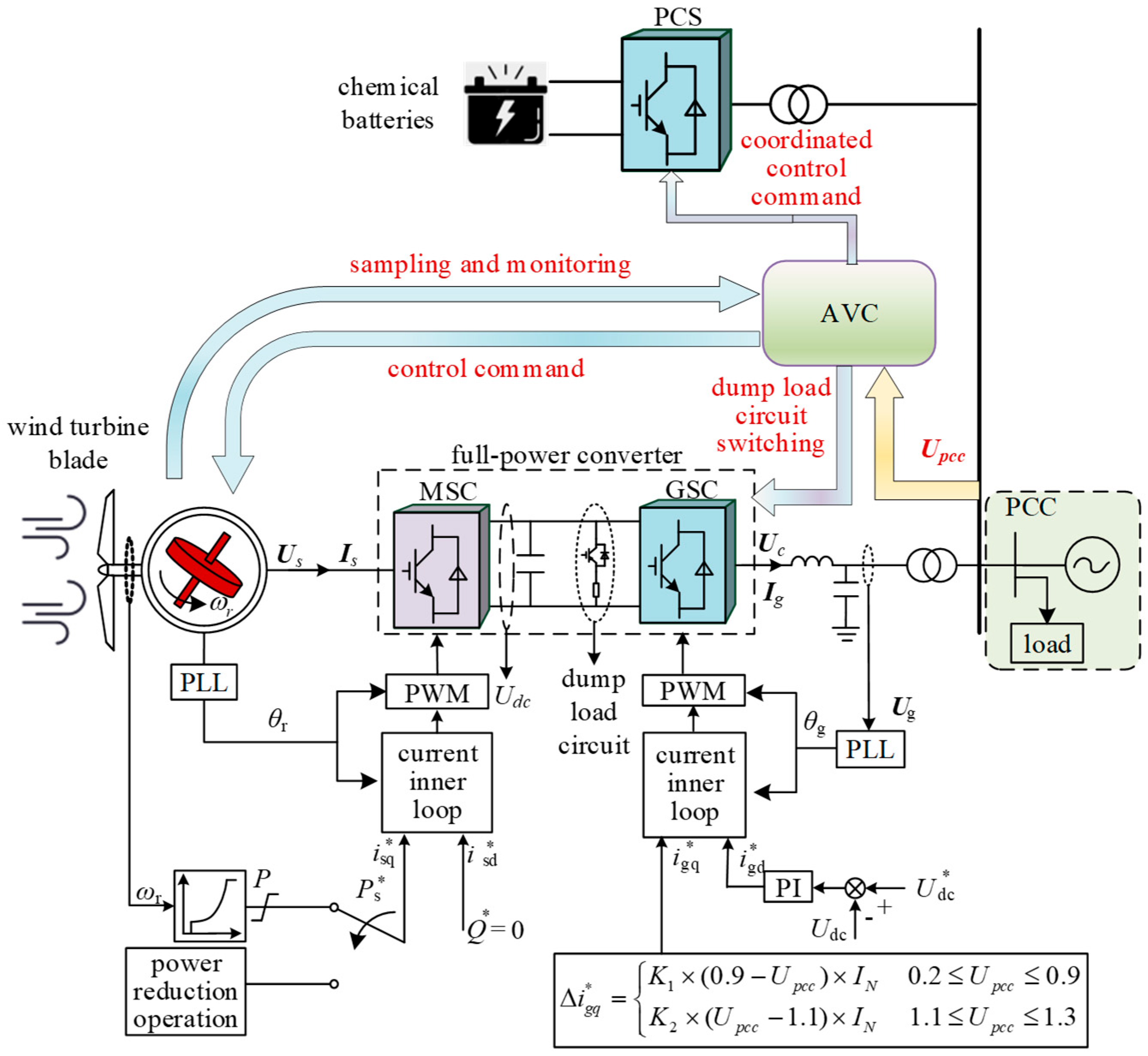

2.1.1. Overall Modeling of Wind–Storage Systems

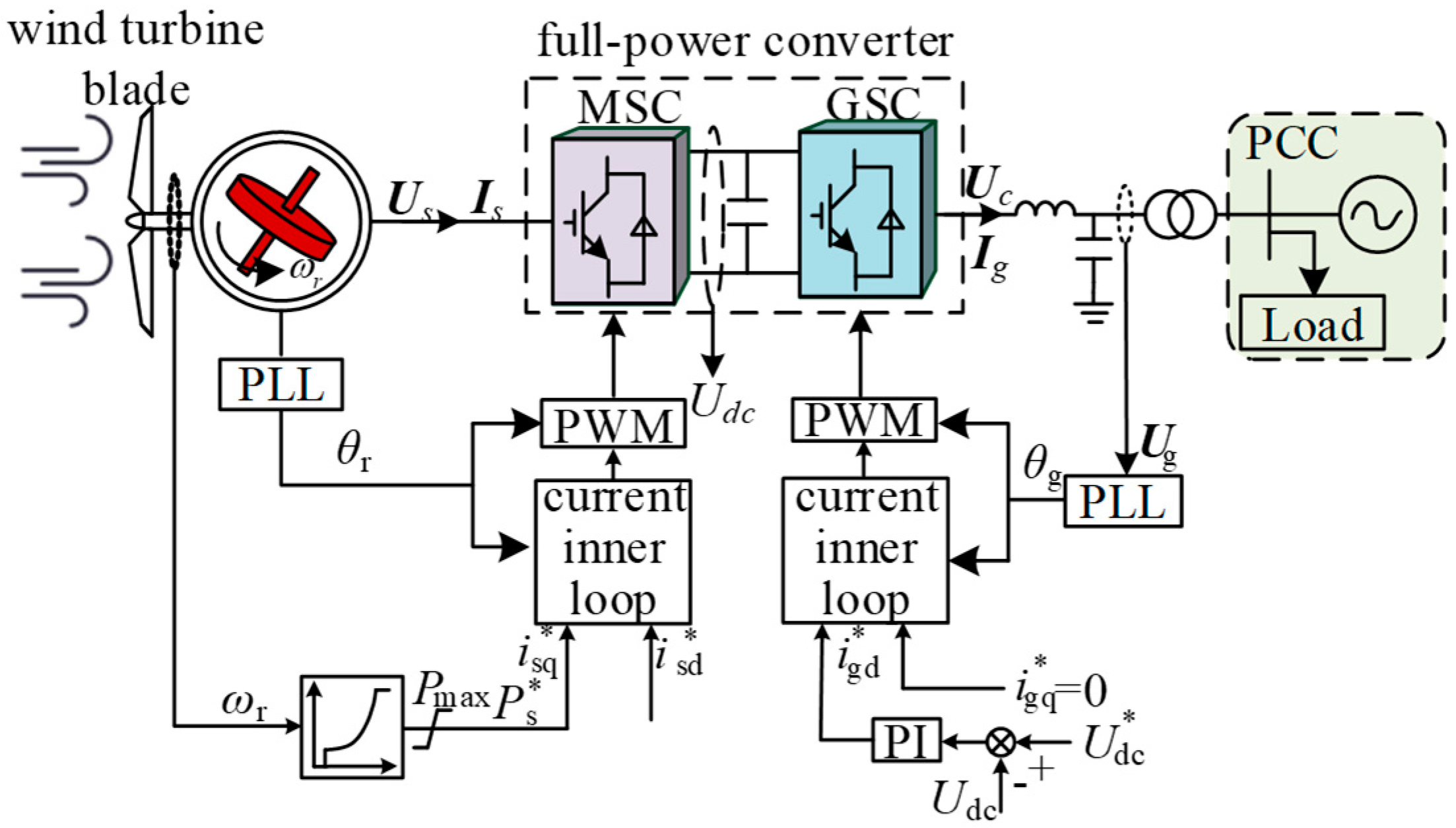

2.1.2. Wind Turbine Control

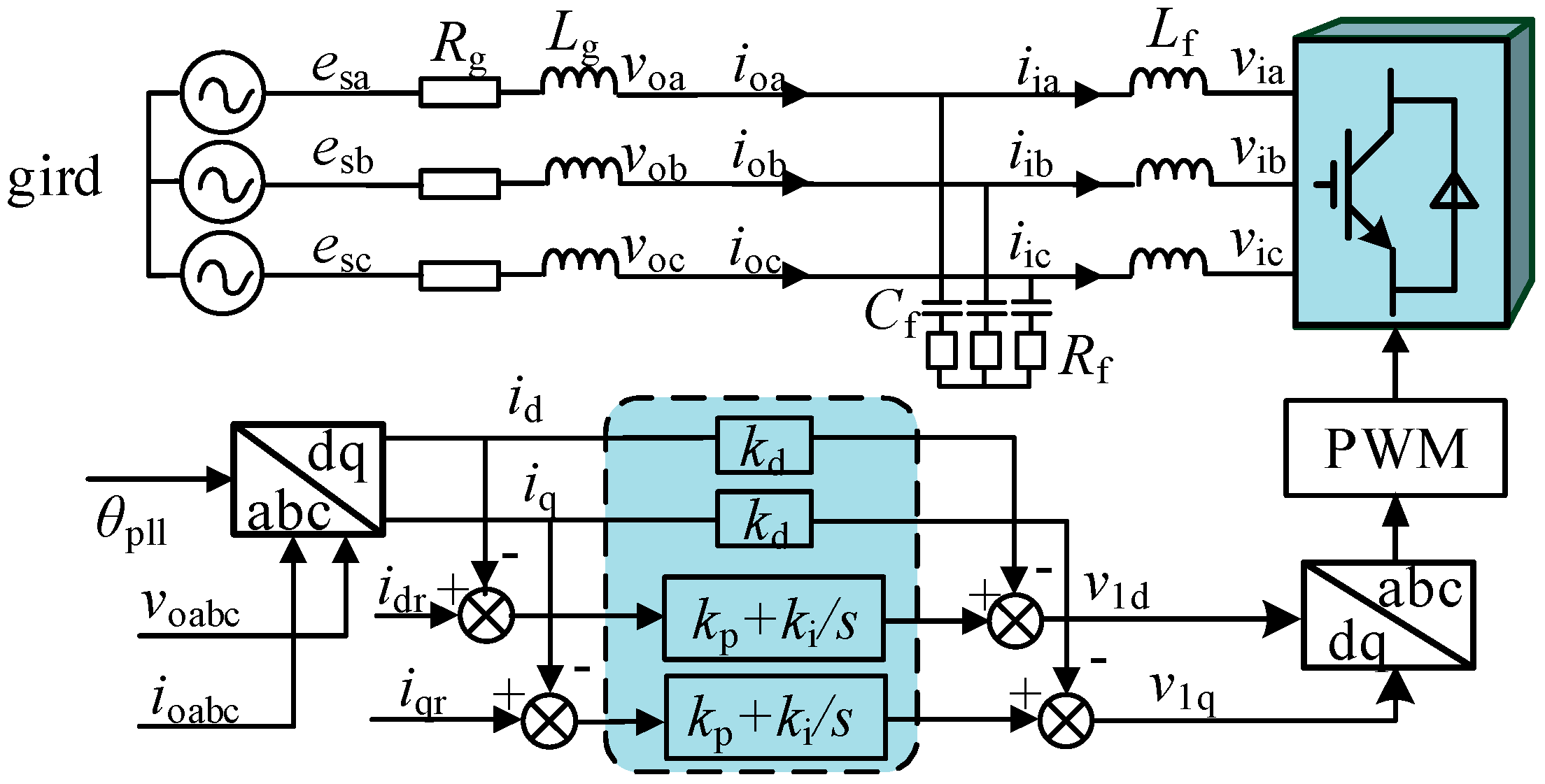

2.1.3. Energy Storage Unit Control

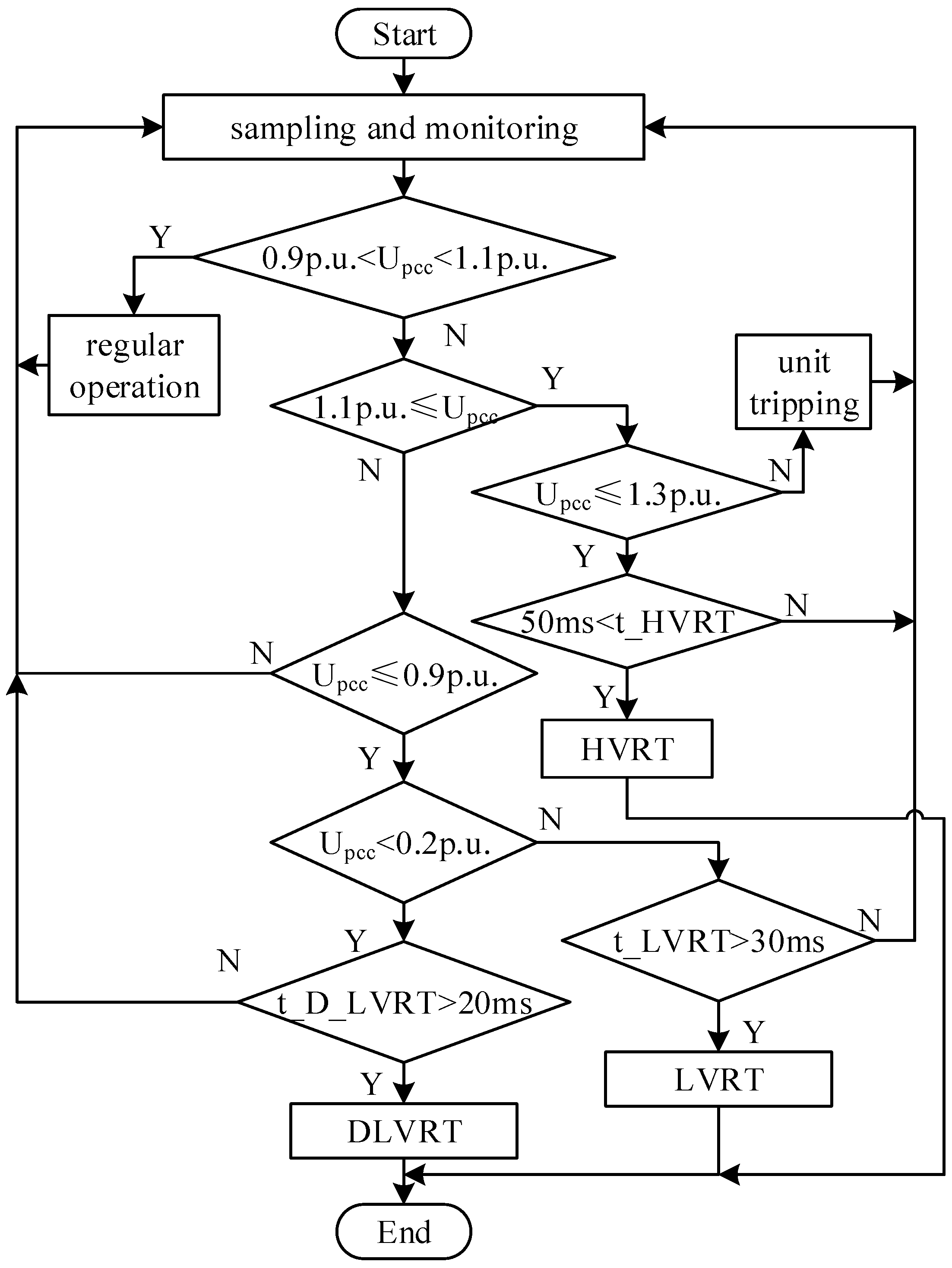

2.2. Wind Turbine Fault Ride-Through Index Constraints and Control Characteristics

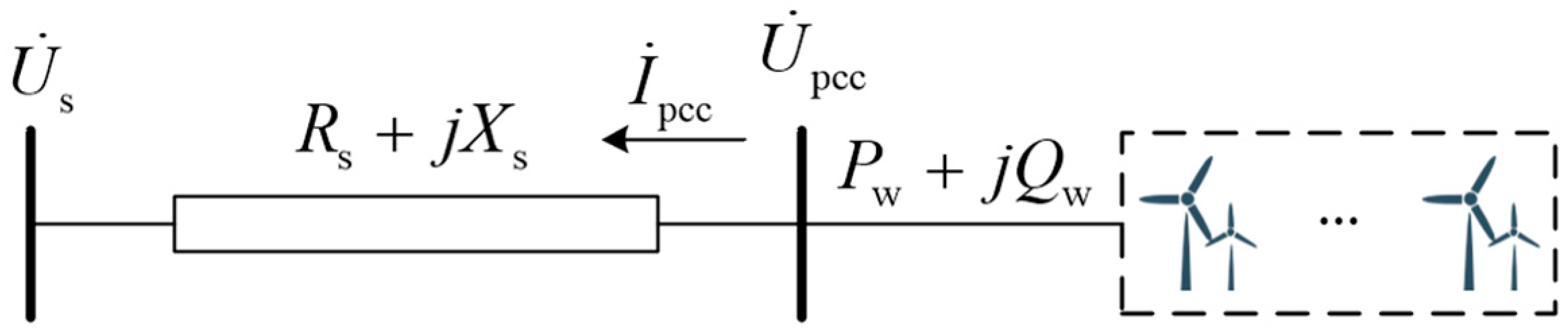

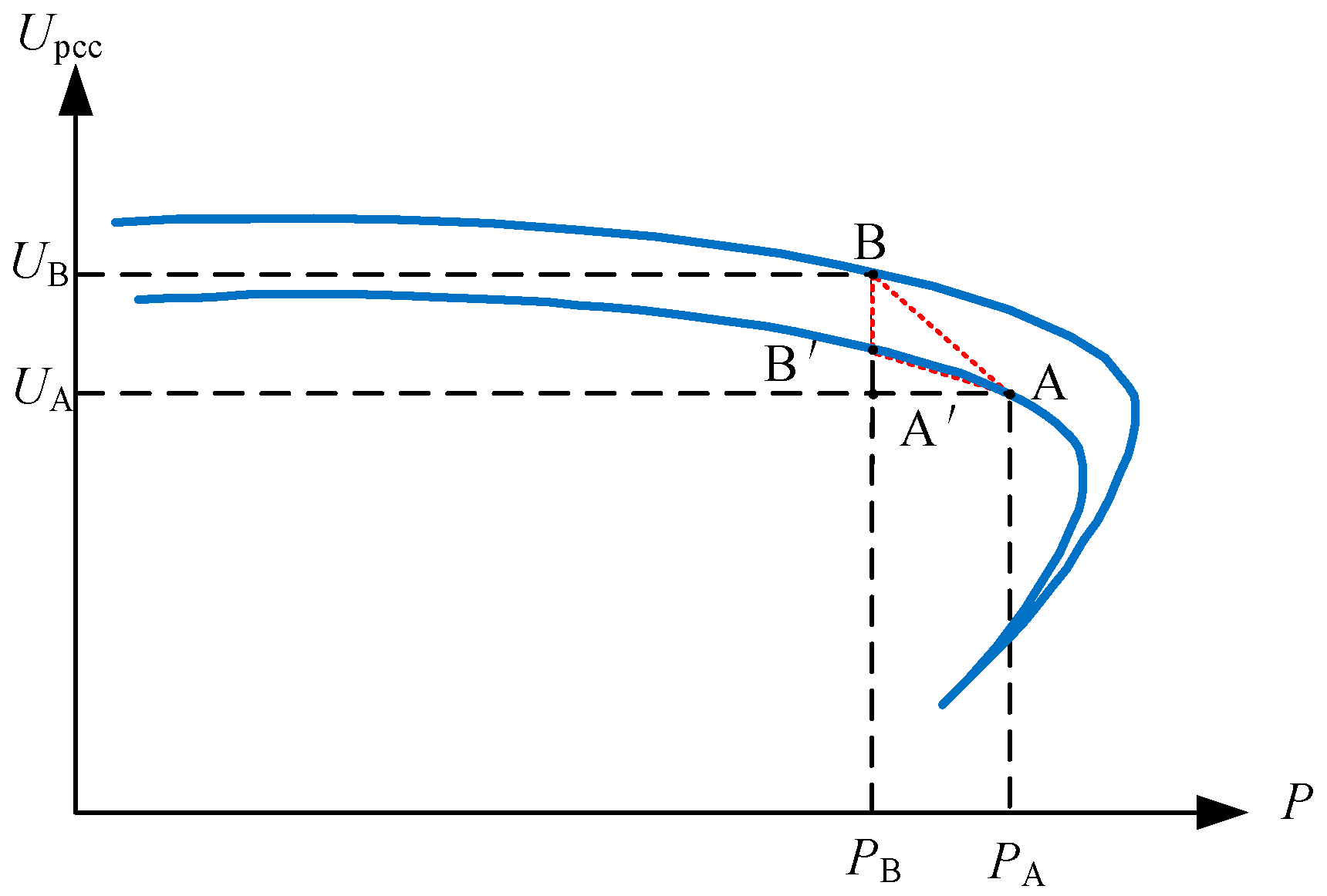

2.3. Analysis of Voltage Repeated Fluctuation Mechanism

3. Methods: Wind–Storage Coordinated Voltage Ride-Through Control Strategy

3.1. Overall Coordinated Control Framework

3.2. Wind–Storage Coordinated LVRT

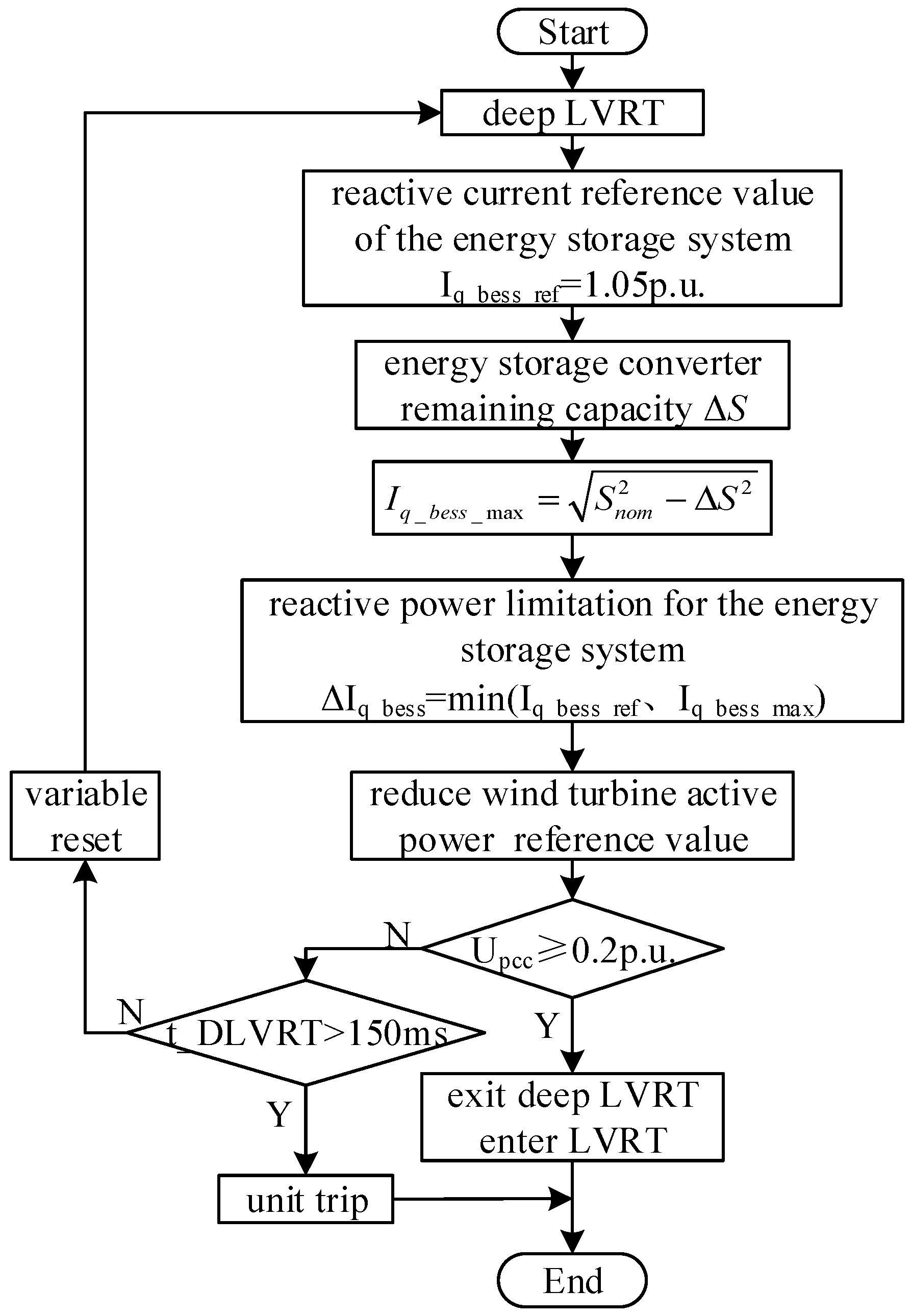

3.2.1. Deep LVRT Mode

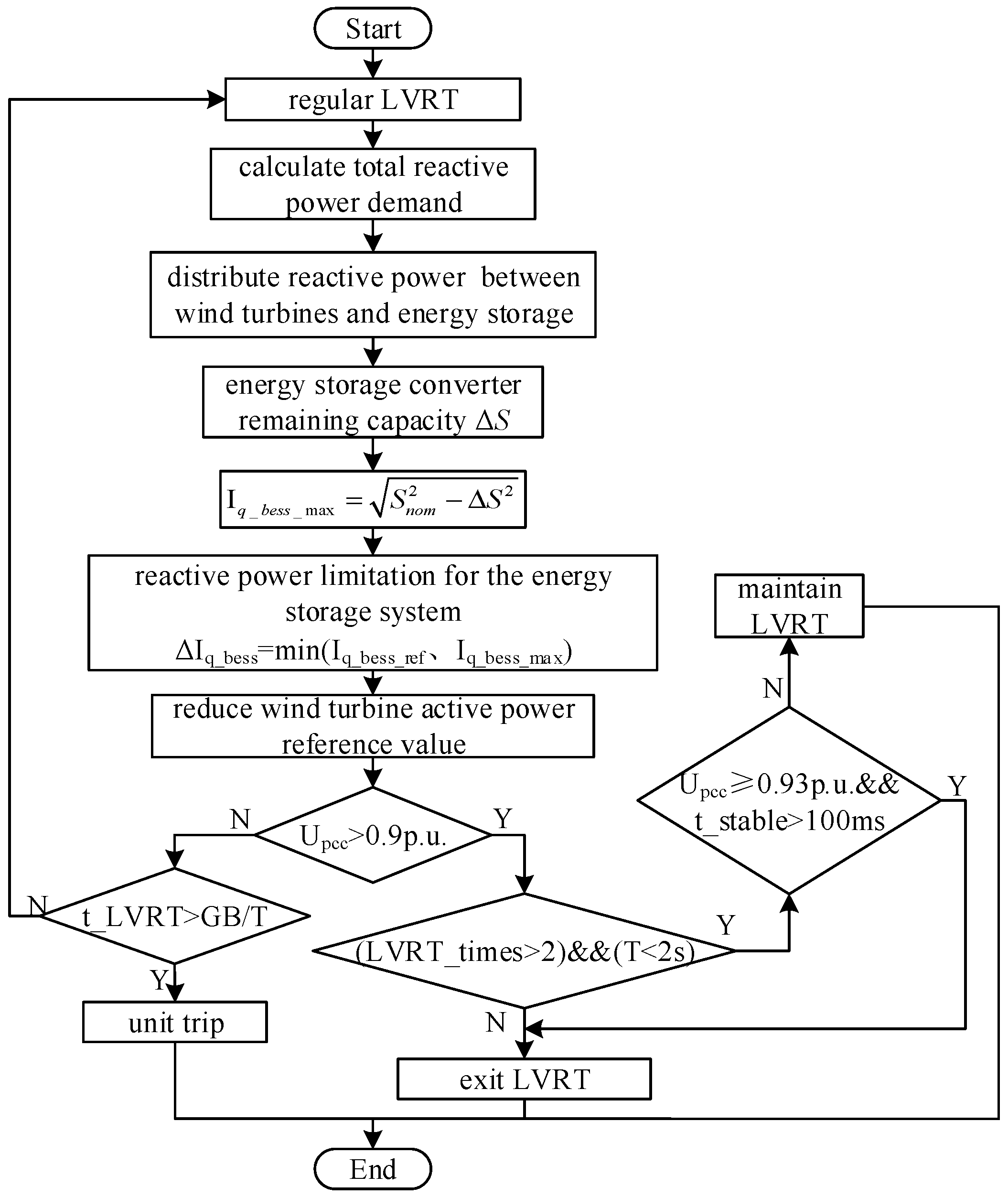

3.2.2. Regular LVRT Mode

3.3. Wind–Storage Coordinated HVRT

4. Results

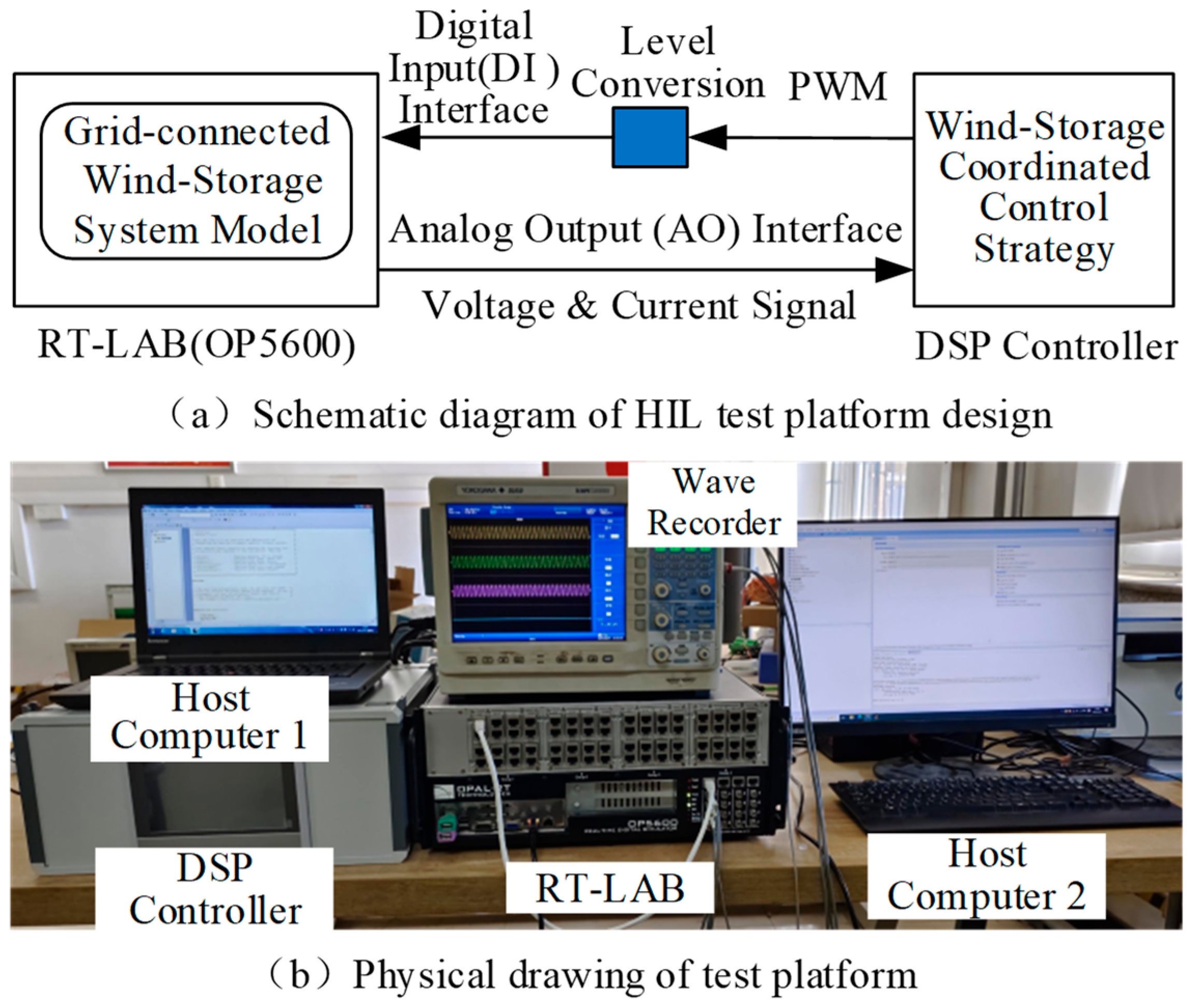

4.1. HIL Simulation Test Platform

4.2. Test Results

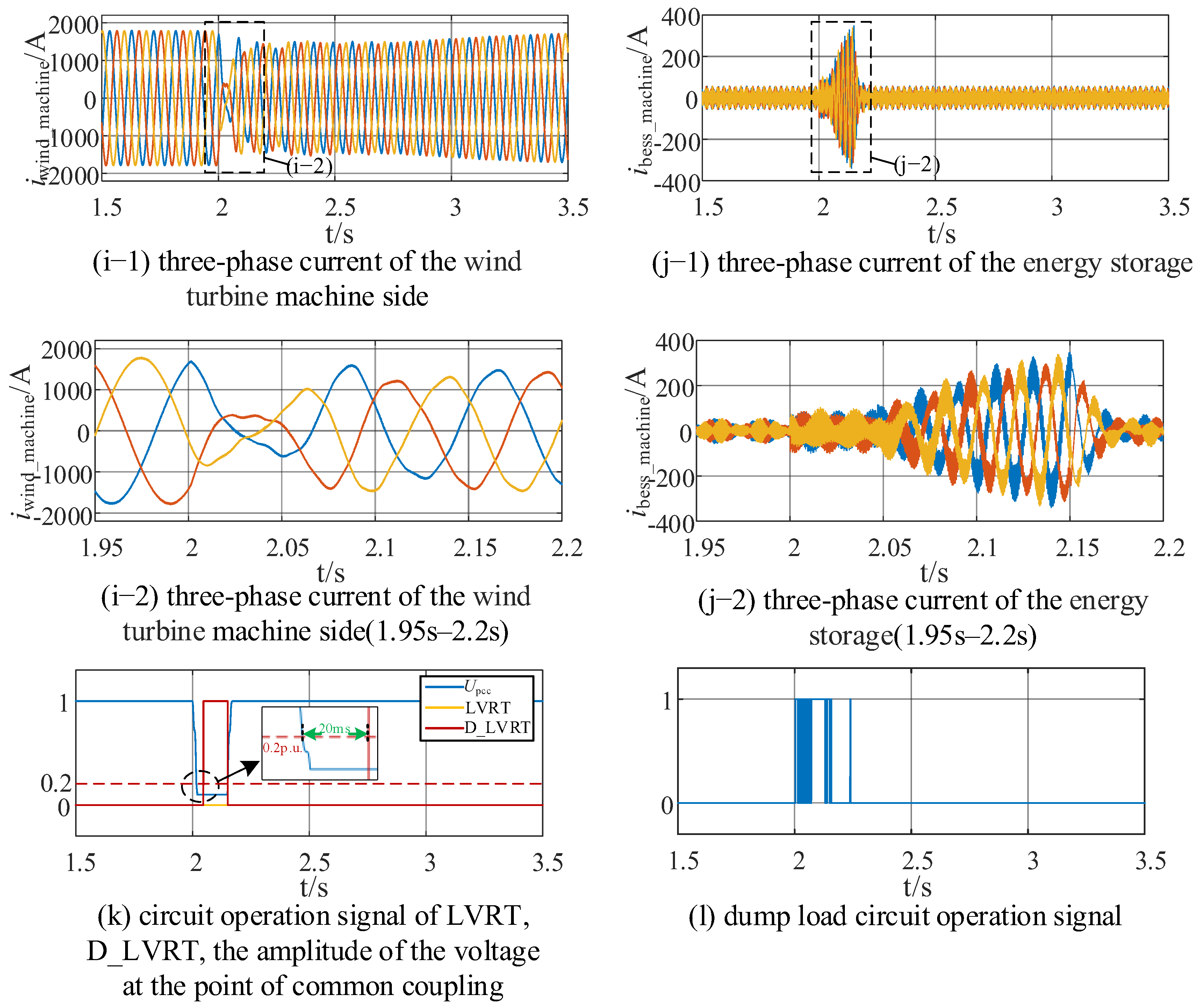

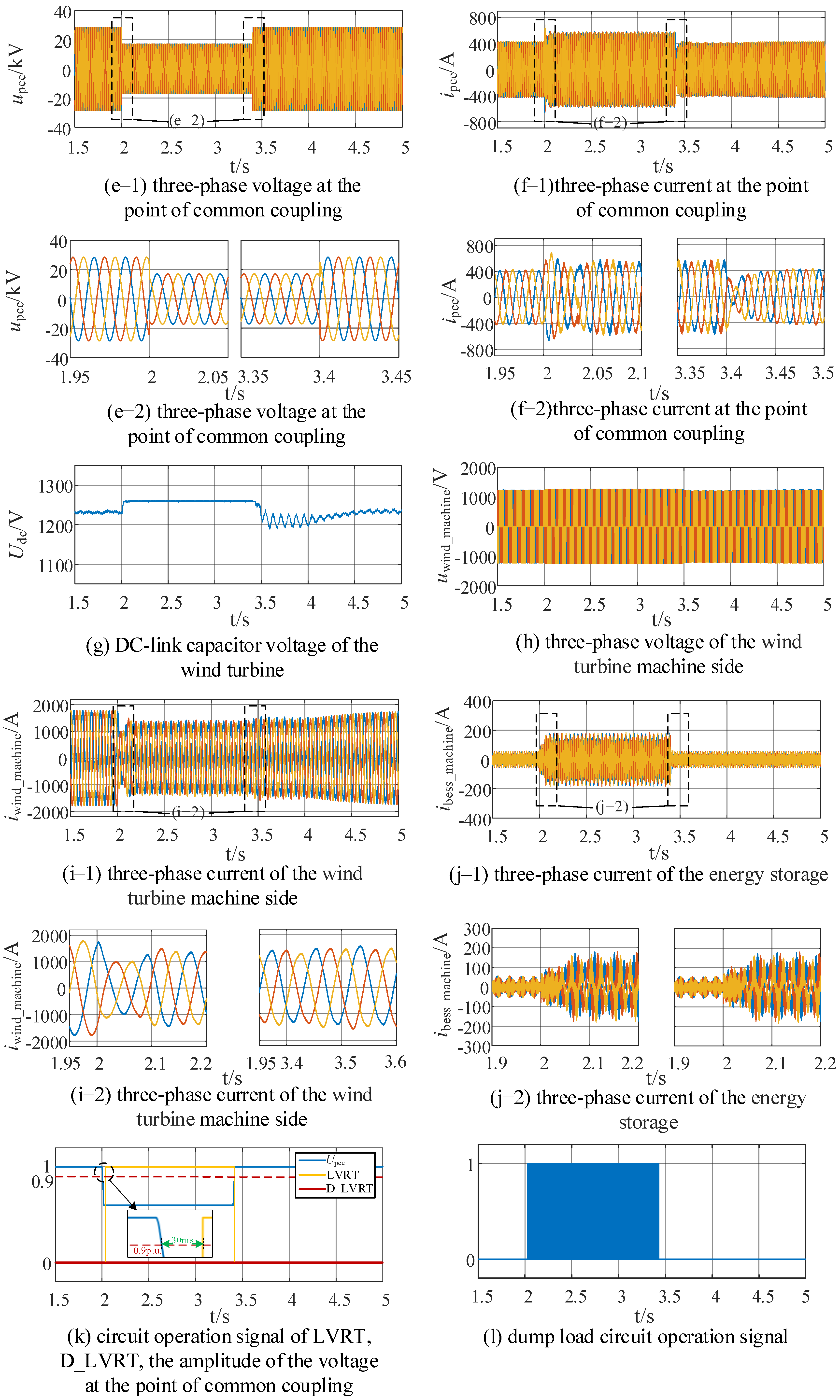

4.2.1. Deep LVRT

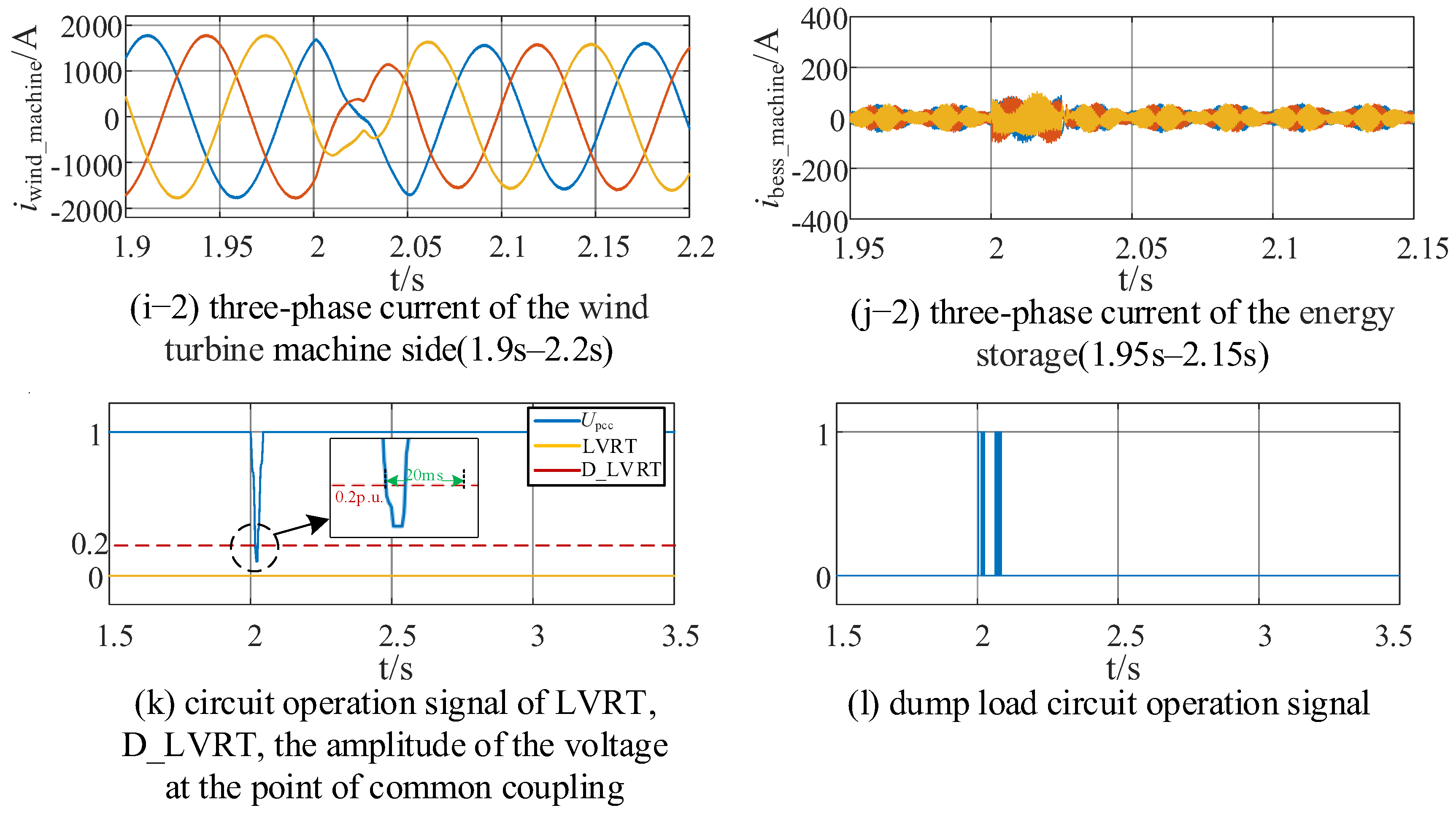

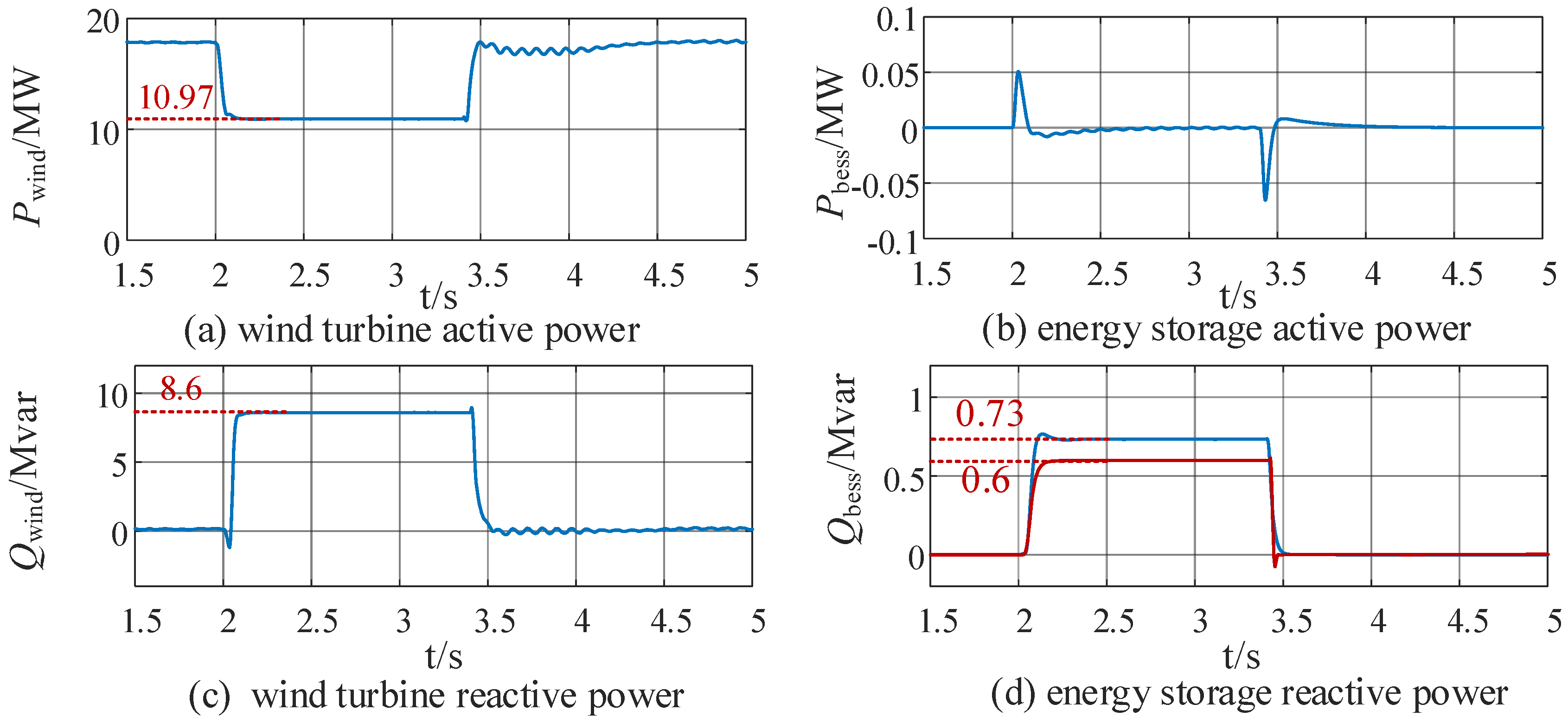

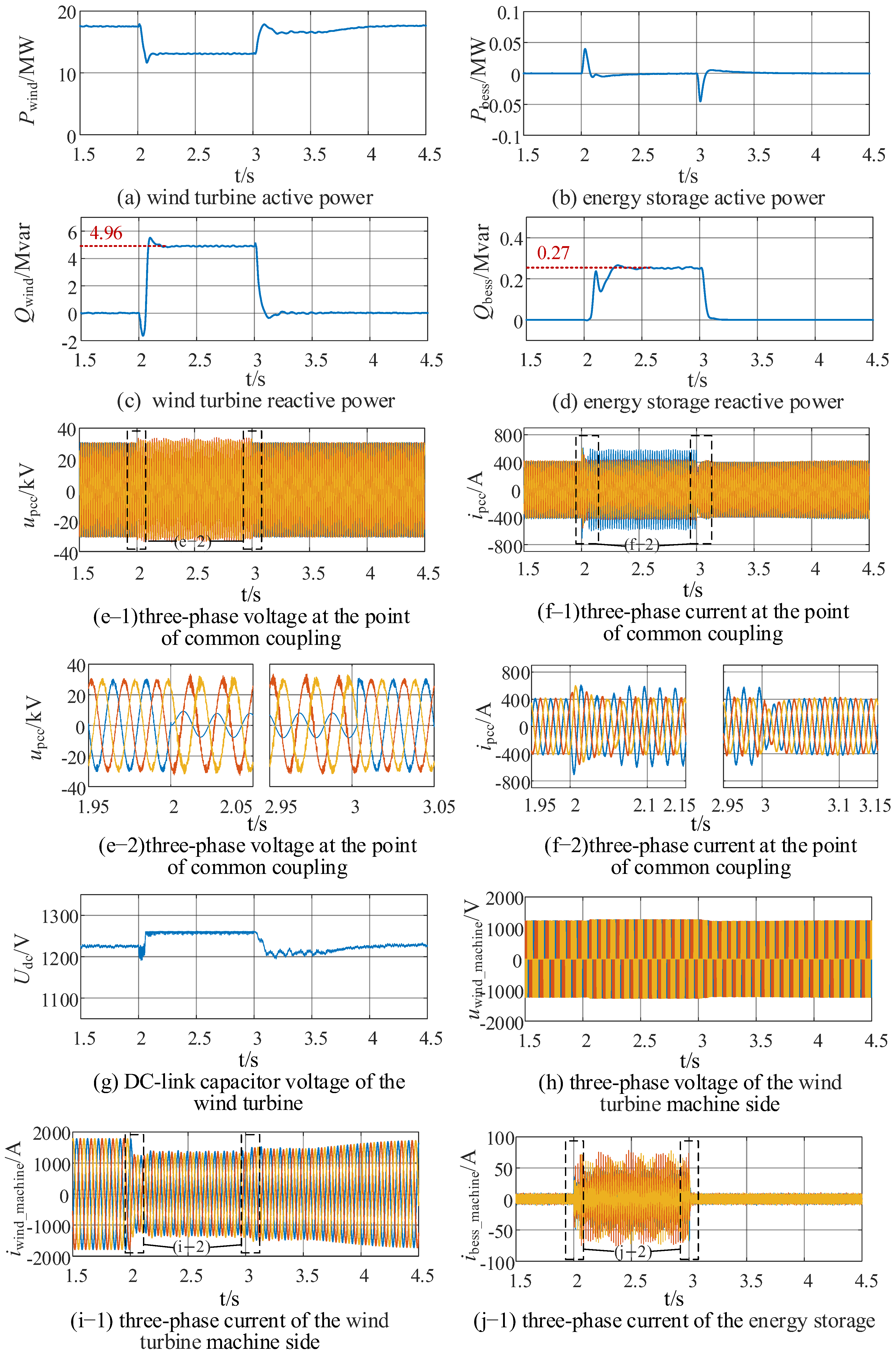

4.2.2. Regular LVRT

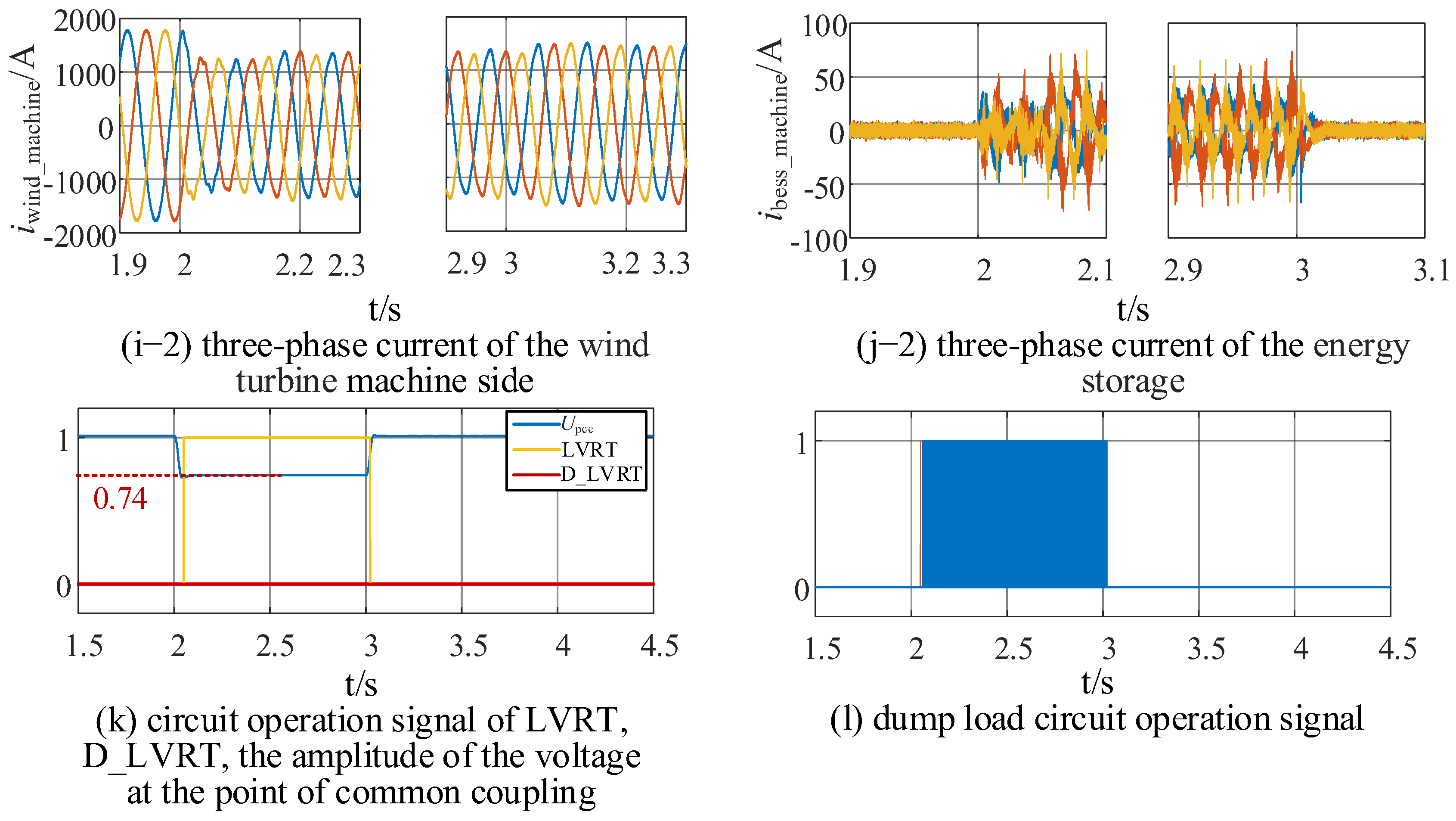

4.2.3. Voltage Fluctuation

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

- (1)

- This study classifies different operating modes based on voltage levels and designs an anti-fluctuation control logic. Compared with the traditional LVRT strategy, the multi-condition performance of the proposed strategy is significantly optimized. Under the extreme condition where the voltage drops to 0.1 pu, the traditional strategy will trigger wind turbine tripping, while the proposed strategy enables wind turbines to remain grid-connected and provide reactive power support. Under the condition of repeated voltage fluctuations induced by the coupling of weak power grids and active power fluctuations, the proposed strategy can suppress repeated LVRT within 2 s and avoid cyclic jumps of the system operating point along the PV curve. Under normal faults, the proposed strategy increases the reactive power support of the energy storage system from 0.6 Mvar (of the traditional strategy) to 0.733 Mvar, with an improvement rate of 22.2% under test conditions. This not only meets the requirements of China’s national standards but also avoids the problem of insufficient reactive power caused by the independent regulation of wind turbines and energy storage systems.

- (2)

- Engineering application value of the strategy: The proposed strategy does not require additional hardware equipment and only needs to optimize the wind turbine control program and the wind farm’s AVC strategy. On the one hand, it replaces the “direct turbine tripping” operation in practical operation and maintenance, ensuring the stability of the wind farm’s active power output and improving the wind farm’s adaptability to extreme weather; on the other hand, it improves the energy storage utilization rate under normal operating conditions and reduces the long-term operation cost of the wind–storage system, serving as an effective improvement to the traditional LVRT and AVC strategies.

- (3)

- Validation effectiveness of the strategy: This study established a HIL test environment based on RT-LAB OP5600 and completed verifications for working conditions such as deep LVRT, normal LVRT, and voltage fluctuations. The test results show that the proposed strategy can accurately match reactive power demands and effectively solve the problem of repeated LVRT caused by voltage fluctuations, which fully verifies the effectiveness of the wind–storage coordinated voltage ride-through control strategy and improves the wind farm’s adaptability to unconventional voltage events under extreme weather.

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| LVRT | Low-voltage ride-through |

| PMSG | Permanent magnet synchronous generator |

| HIL | Hardware-in-the-loop |

| FRT | Fault ride-through |

| GSC | Grid-side converter |

| PSO | Particle swarm optimization |

| PCC | Point of common coupling |

| MPPT | Maximum power point tracking |

| MSC | Machine-side converter |

| PLL | Phase-locked loop |

| HVRT | High-voltage ride-through |

| AVC | Automatic voltage control |

| BESS | Battery energy storage system |

References

- Akdemir, K.Z.; Kern, J.D.; Lamontagne, J. Assessing risks for new England’s wholesale electricity market from wind power losses during extreme winter storms. Energy 2022, 251, 123886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kabsha, M.M.; Rather, Z.H. Advanced LVRT control scheme for offshore wind power plant. IEEE Trans. Power Deliv. 2021, 36, 3893–3902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Xu, Z.; Zhang, J.; Meng, K. Variable droop voltage control for wind farm variable droop voltage control for wind farm. IEEE Trans. Sustain. Energy 2017, 9, 491–493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- An, S.; Qiu, J.; Lin, J.; Yao, Z.; Liang, Q.; Lu, X. Planning of a multi-agent mobile robot-based adaptive charging network for enhancing power system resilience under extreme conditions. Appl. Energy 2025, 395, 126252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kebede, A.; Kalogiannis, T.; Van, M.J.; Berecibar, M. A comprehensive review of stationary energy storage devices for large scale renewable energy sources grid integration. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2022, 159, 112213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen, T.; Zhang, Z.; Lin, X.; Li, Z.; Chen, C.; Wang, Z. Research on modeling and the operation strategy of a hydrogen-battery hybrid energy storage system for flexible wind farm grid-connection. IEEE Access 2020, 8, 79347–79356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyu, X.; Jia, Y.; Liu, T.; He, Y. Concurrent optimal re/active power control for wind farms under low-voltage-ride-through operation. IEEE Trans. Power Syst. 2020, 35, 4956–4959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Badihi, H.; Zhang, Y.; Pillay, P.; Rakheja, S. Fault-tolerant individual pitch control for load mitigation in wind turbines with actuator faults. IEEE Trans. Ind. Electron. 2021, 68, 532–543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geng, H.; Xu, D.; Wu, B.; Yang, G. Active Damping for PMSG-Based WECS With DC-Link Current Estimation. IEEE Trans. Ind. Electron. 2011, 58, 1110–1119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phuong, T.H.; Nguyen, S.; Studli, J.H.; Middleton, R.H. Coordinated Control for Low Voltage Ride Through in PMSG Wind Turbines. In Proceedings of the 10th IFAC Symposium on Control of Power and Energy Systems CPES 2018, Tokyo, Japan, 4–6 September 2018. [Google Scholar]

- GB/T 19963.1–2021; China Electricity Council. Technical Specification for Connecting Wind Farm to Power System—Part 1: On Shore Wind Power. Standards Press of China: Beijing, China, 2021.

- Xu, M.; Wu, L.; Liu, H.T.; Yang, Y.; Li, Y. Research on the mechanism and control methods of repeated voltage fluctuations in large-scale wind power integration system. In Proceedings of the 2021 International Conference on Power System Technology (POWERCON), Haikou, China, 8–9 December 2021; pp. 1214–1219. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, L.; Zhao, W.; Xu, M.; Xu, P.; Li, F.; Yang, Y.; Pan, Y. Mechanism Analysis and Suppression of Repeated Voltage Fluctuation Considering Fault Ride Through Characteristics of the Wind Turbine. J. Glob. Energy Interconnect. 2022, 5, 290–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lan, T.; Jing, Y.; Xu, S.; Zhao, B. Modelling and analysis of abnormal transient performance in bulk power system dominated by low-voltage-ride-through of distributed renewables. In Proceedings of the 12th International Conference on Renewable Power Generation (RPG 2023), Shanghai, China, 14–15 October 2023; pp. 821–825. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Q.; Chen, M.; Hao, W.; Li, Z.; Gan, D. Analysis on dynamic voltage of renewable energy generators during post-fault recovery based on monotone control theory. In Proceedings of the 2021 International Conference on Power System Technology (POWERCON), Haikou, China, 8–9 December 2021; pp. 1155–1160. [Google Scholar]

- Kong, H.; Yang, J.Z.; Zhao, Y.H.; Zhang, Z.; Hou, S.; Xue, A. Bifurcation analysis and criterion of voltage oscillation induced by low voltage ride through control in renewable energy stations. IEEE Trans. Circuits Syst. II: Express Briefs 2024, 71, 2439–2443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lai, Q.; Shen, C.; Li, D. Dynamic modeling and stability analysis for repeated LVRT process of wind turbine based on switched system theory. IEEE Trans. Power Syst. 2025, 40, 2711–2723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, M.; Wang, Y.; Wang, X.; Chang, J.; Zhou, Y.; Liu, T. Modeling and Simulation of Large-Scale Wind Power Base Output Considering the Clustering Characteristics and Correlation of Wind Farms. Front. Energy Res. 2022, 10, 810082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, X.; Lee, W.; Sahni, M.; Cheng, Y.; Lee, L.K. Dynamic Equivalent Model Development to Improve the Operation Efficiency of Wind Farm. IEEE Trans. Ind. Appl. 2016, 52, 2759–2767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, S.; Gao, Z.W. Extended modeling for wind turbines with application to hybrid renewable energy systems. Eng. Sci. Technol. Int. J. 2025, 70, 102168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- GB/T 17626.11-2023; National Standardization Administration. Electromagnetic Compatibility—Testing and Measurement Techniques—Part 11: Voltage Dips, Short Interruptions and Voltage Variations Immunity Tests for Equipment with Input Current up to 16 A per Phase. Standards Press of China: Beijing, China, 2023.

- GB/T 30137-2024; National Standardization Administration. Power Quality—Voltage Swell, Voltage Dips and Short Interruptions. Standards Press of China: Beijing, China, 2024.

- GB/T 39269-2020; National Standardization Administration. Voltage Dip and Short Interruption—Immunity Testing Method for Low Voltage Equipment. Standards Press of China: Beijing, China, 2020.

| PMSG Model Parameters | Values | BESS Model Parameters | Values |

|---|---|---|---|

| Rated capacity/MVA | 1.5 | Rated capacity/MVA | 1 |

| Total wind farm rated power/MW | 18 | Total wind farm rated power/MW | 3 |

| Rated wind speed/(m/s) | 11 | Rated capacity per unit/MWh | 1.25 |

| DC bus voltage/V | 1200 | DC bus voltage/V | 1200 |

| Converter switching frequency/kHz | 10 | Converter switching frequency/kHz | 10 |

| Grid-side filter inductance/mH | 15 | Filter inductance/mH | 10 |

| Grid-side filter capacitance/μF | 50 | Filter capacitance/μF | 40 |

| Machine-side converter current loop PI (kp, ki) | 0.9, 22 | Converter current loop PI (kp, ki) | 2.5, 10 |

| Grid-side converter current loop PI (kp, ki) | 0.5, 150 | SOC operating range | 20–90% |

| Reactive current coefficient during LVRT | 2 | Reactive current coefficient during LVRT | 3 |

| Test Condition | Proposed Coordinated Control Strategy | Traditional LVRT Control Strategy | Comparison Effect |

|---|---|---|---|

| Upcc dip: 0.1 p.u.; 150 ms | PMSG maintains grid integration and provides reactive power support | PMSG trip | Enhanced adaptability to extreme operating conditions |

| Upcc dip: 0.1 p.u.; 25 ms | PMSG maintains grid integration | PMSG trip | |

| Upcc fluctuation | Suppresses repeated LVRT within 2 s | Repeated LVRT | |

| Upcc dip: 0.6 p.u.; 1.4 s | BESS reactive power support: 0.733 Mvar | BESS reactive power support: 0.6 Mvar | Improved reactive power support |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Wang, Y.; Shang, K.; Xu, Z.; Hu, C.; Gao, B.; Meng, J. Wind–Storage Coordinated Control Strategy for Suppressing Repeated Voltage Ride-Through of Units Under Extreme Weather Conditions. Energies 2026, 19, 65. https://doi.org/10.3390/en19010065

Wang Y, Shang K, Xu Z, Hu C, Gao B, Meng J. Wind–Storage Coordinated Control Strategy for Suppressing Repeated Voltage Ride-Through of Units Under Extreme Weather Conditions. Energies. 2026; 19(1):65. https://doi.org/10.3390/en19010065

Chicago/Turabian StyleWang, Yunpeng, Ke Shang, Zhen Xu, Chen Hu, Benzhi Gao, and Jianhui Meng. 2026. "Wind–Storage Coordinated Control Strategy for Suppressing Repeated Voltage Ride-Through of Units Under Extreme Weather Conditions" Energies 19, no. 1: 65. https://doi.org/10.3390/en19010065

APA StyleWang, Y., Shang, K., Xu, Z., Hu, C., Gao, B., & Meng, J. (2026). Wind–Storage Coordinated Control Strategy for Suppressing Repeated Voltage Ride-Through of Units Under Extreme Weather Conditions. Energies, 19(1), 65. https://doi.org/10.3390/en19010065