A Two-Stage Voltage Sag Source Localization Method in Microgrids

Abstract

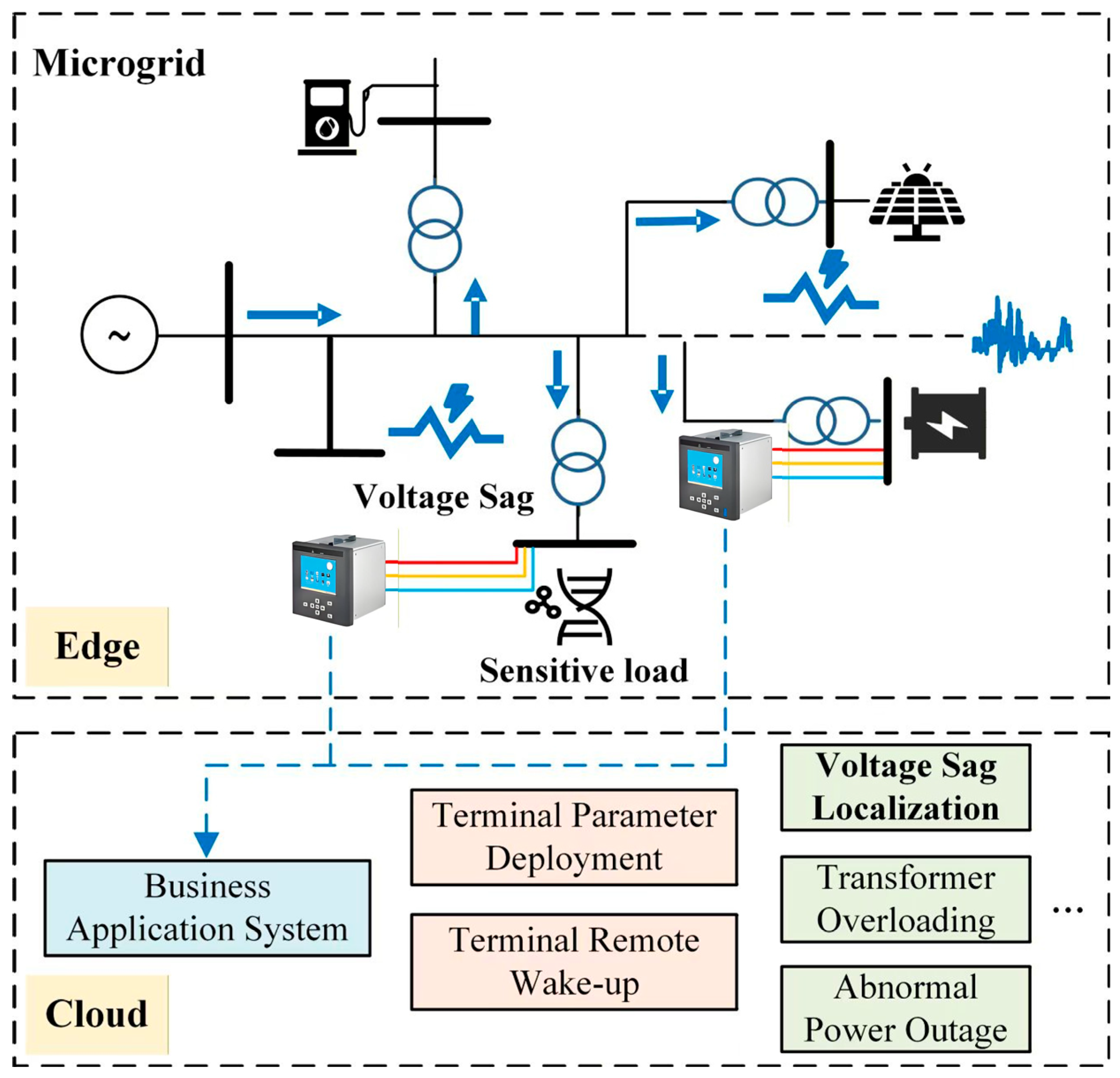

1. Introduction

- (1)

- A two-stage localization framework is proposed for identifying voltage sag sources in microgrids with high renewable penetration. The method integrates a data-driven spatial-temporal learning model and a model-based refinement strategy, combining the strengths of data-driven intelligence and physical interpretability.

- (2)

- An improved STGCN is developed to capture spatio-temporal dependencies among node measurements. The model enables section-level localization of voltage sag sources while maintaining strong robustness against measurement asynchrony and data noise.

- (3)

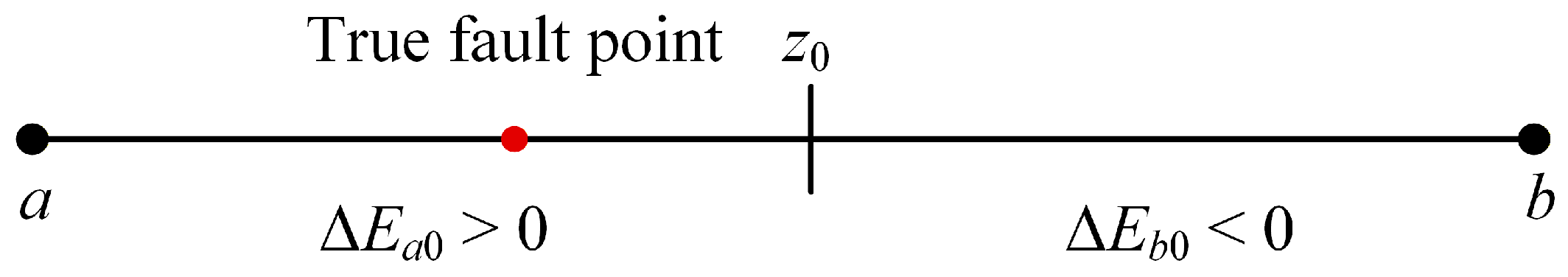

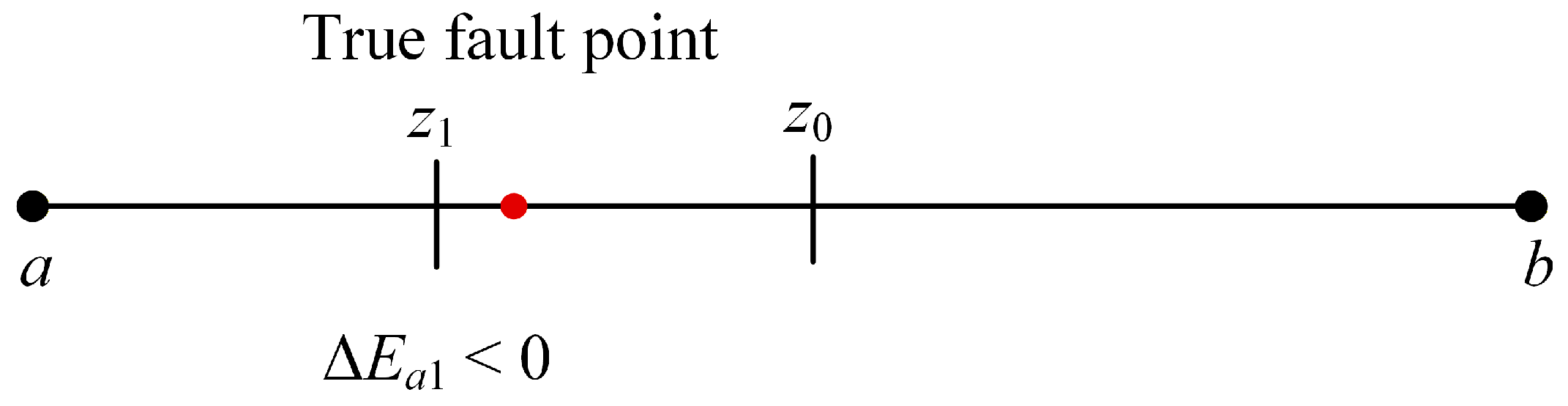

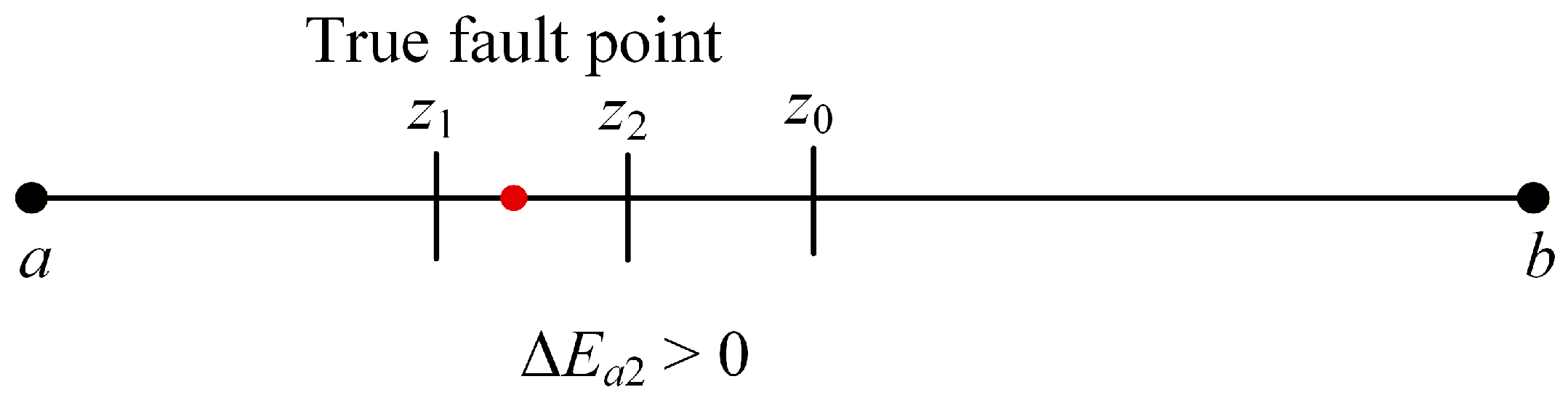

- A binary search refinement algorithm is proposed to achieve precise fault localization within the identified section. The algorithm iteratively compares simulated and measured sag characteristics and converges rapidly to the actual fault point, thereby improving both accuracy and convergence speed.

2. Section-Level Localization of Voltage Sag Sources Based on Improved STGCN

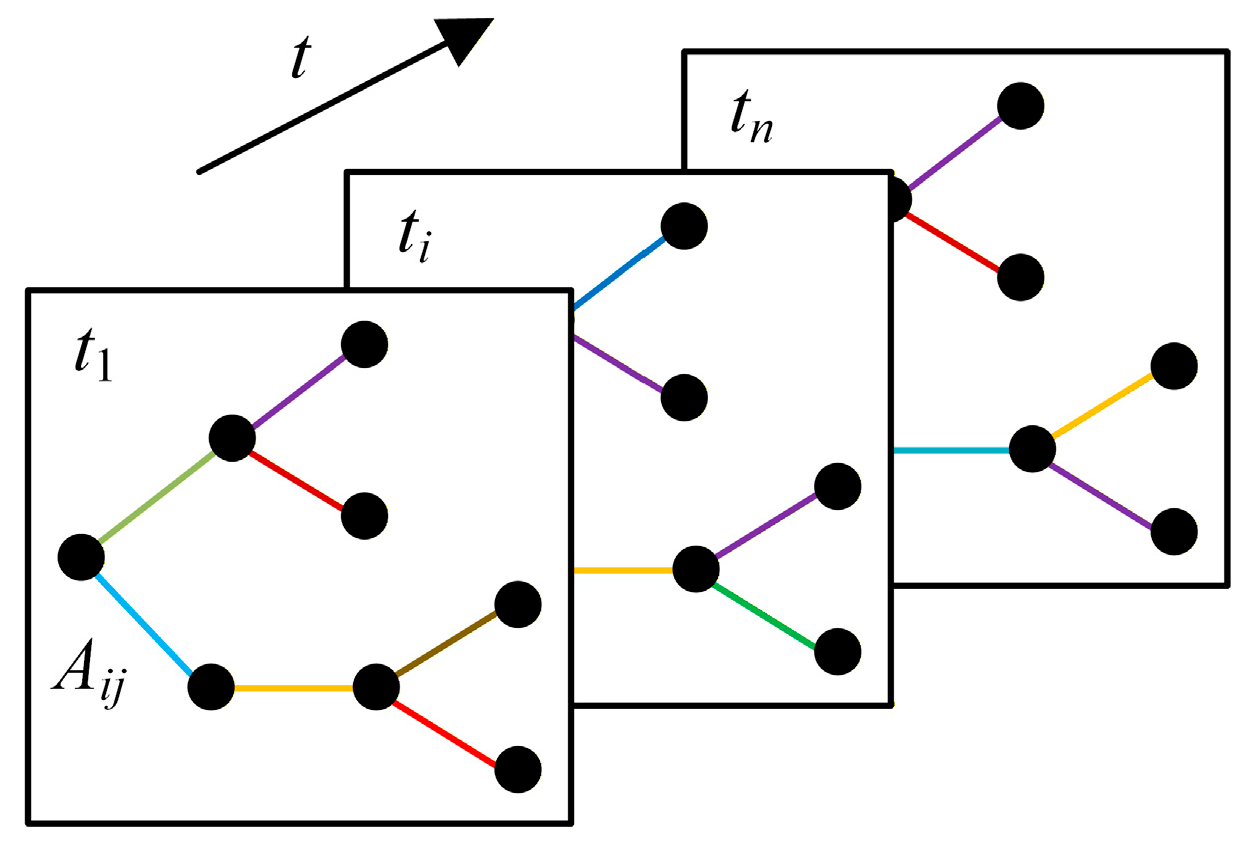

2.1. Spatio-Temporal Correlation Analysis and Modeling of Microgrid

2.1.1. Analysis of Spatio-Temporal Coupling Characteristics of Microgrids

2.1.2. Modeling of Spatio-Temporal Coupling Characteristics of Microgrid

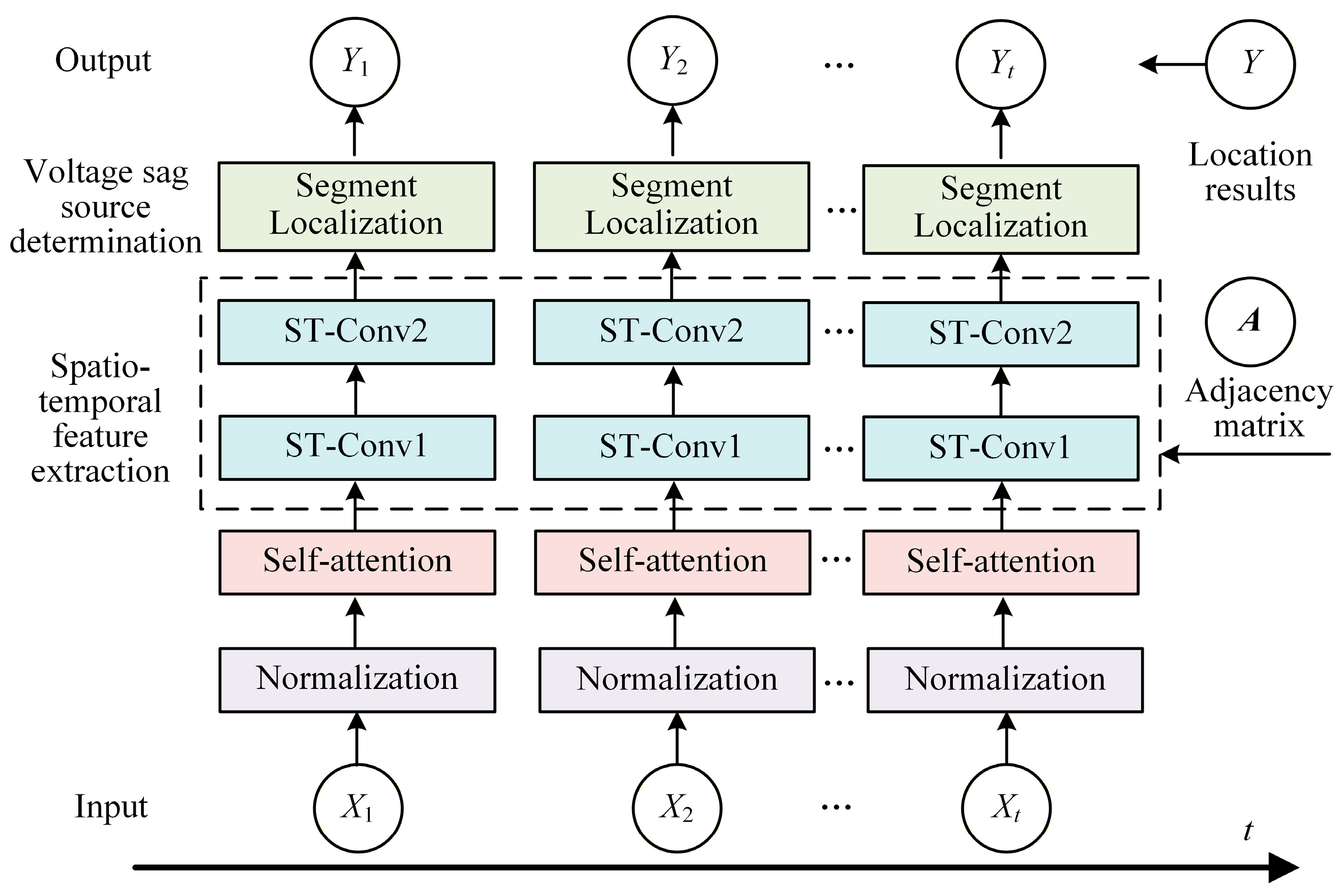

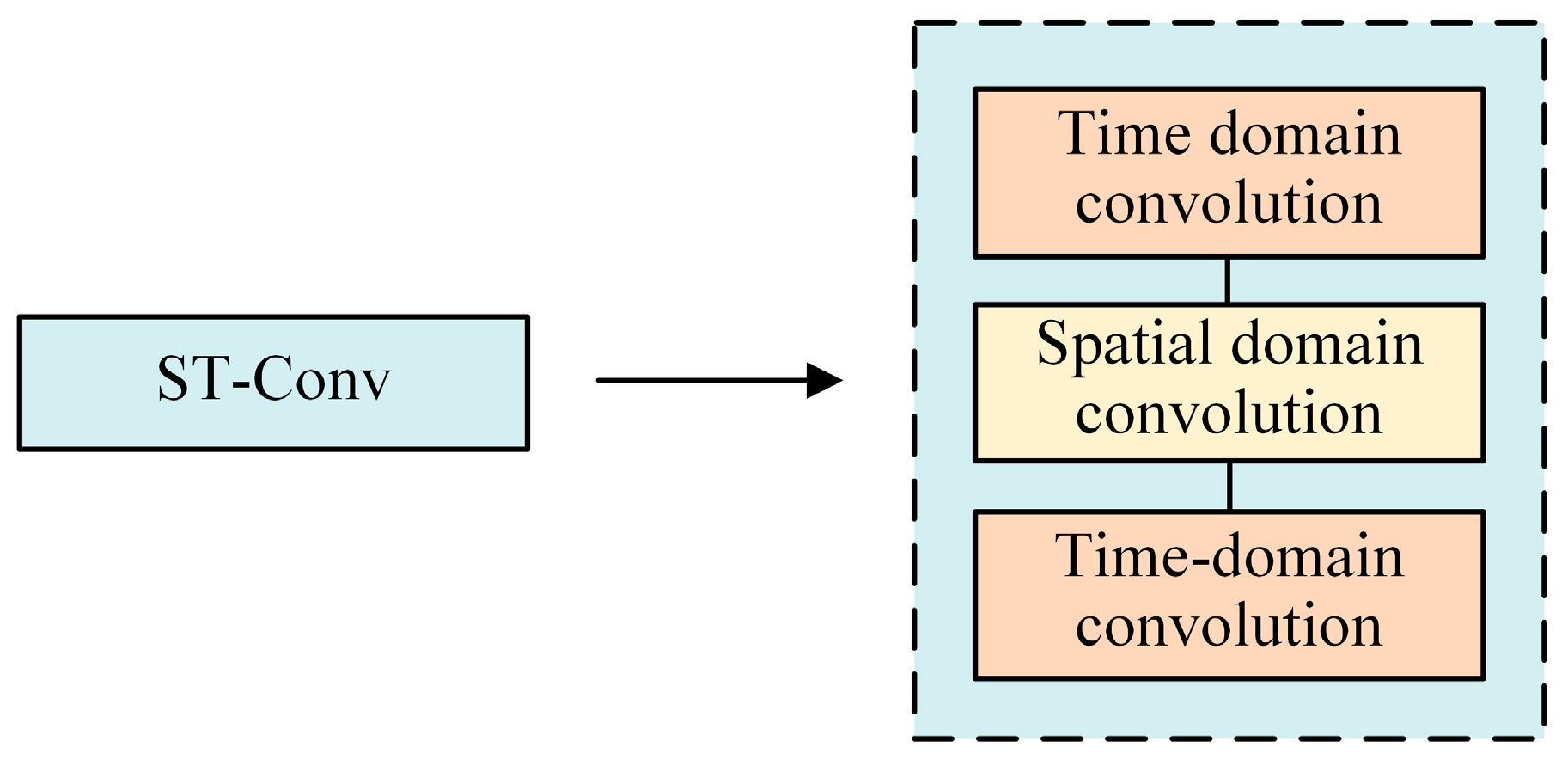

2.2. Architecture of the Improved STGCN-Based Voltage Sag Source Section Localization Model

2.2.1. Overall Model Architecture and Spatiotemporal Coupling Representation

2.2.2. Section Localization Module Design

3. Precise Localization Strategy of Voltage Sag Sources

4. Case Study

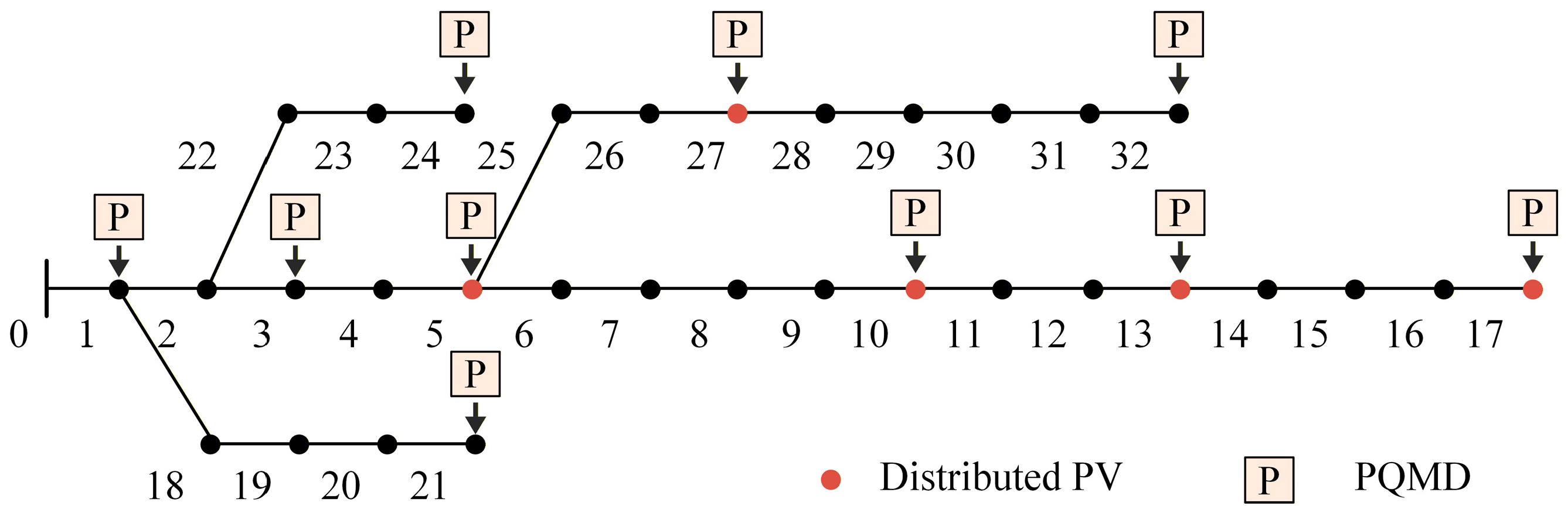

4.1. Test System and Data Configuration

4.2. Accuracy Analysis of the Proposed Method in Different Fault Scenarios

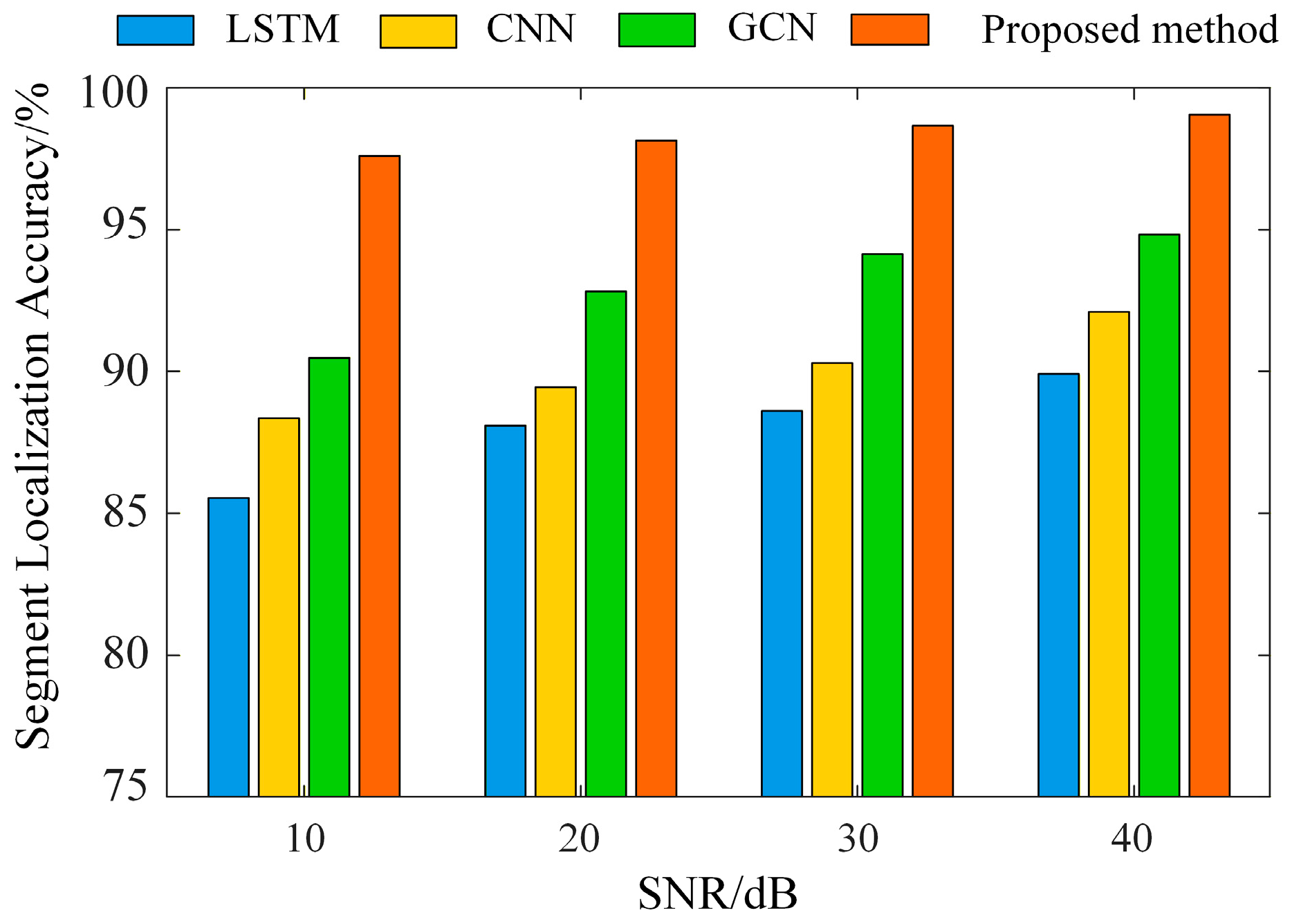

4.2.1. Section Localization of Voltage Sag Sources

4.2.2. Precise Localization of Voltage Sag Sources

4.3. Accuracy Analysis of the Proposed Method in Different Fault Scenarios

4.4. Verification of the Generalizability of the Proposed Method

5. Conclusions

- (1)

- The improved STGCN effectively integrates the spatial topology and steady-state time series information of the microgrid, and the extracted spatio-temporal features have good section localization capabilities. Compared with other basic methods, it maintains a high accuracy rate of section localization under different penetration rates of distributed new energy and can adapt to the operational characteristics of microgrids.

- (2)

- Based on the section localization, binary search is introduced. By injecting and discriminating the equivalent voltage sag source current, the range is rapidly narrowed down, achieving the preset accuracy within a limited number of rounds and realizing high-precision voltage sag source localization within the fault section.

- (3)

- Under the conditions of noise interference and topological changes, the proposed method can still maintain a high localization accuracy rate, demonstrating good robustness and generalization ability, and has strong engineering application potential.

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Xu, F.W.; Guo, K.; Wang, C.; Huang, J.; Zhao, B.; Liu, J. Estimation of Voltage Sag Frequency Based on the Multiple Characteristic Factors. IEEE Trans. Power Del. 2025, 40, 2402–2411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, S.N.; Peng, K.X.; Hu, C.B.; Ding, S.X.; Fan, H. A Residual-Generator-Based Plug-and-Play Control Scheme Toward Enhancing Power Quality in AC Microgrids. IEEE Trans. Ind. Electron. 2022, 69, 8146–8156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, T.K.; Chang, G.W.; Liu, Y.J.; Li, G.Y. Improving Voltage Ride-Through Capability of Grid-Tied Microgrid with Harmonics Mitigation. IEEE Trans. Power Del. 2023, 38, 738–741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ji, L.; Shi, J.B.; Hong, Q.T.; Fu, Y.; Chang, X.; Cao, Z. A Multi-Objective Control Strategy for Three Phase Grid-Connected Inverter During Unbalanced Voltage Sag. IEEE Trans. Power Del. 2021, 36, 2490–2500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, Y.L.; Kwang, M.H.; Soon, R.N. A Fault Location Algorithm for Multi-Section Combined Transmission Lines Considering Unsynchronized Sampling. Energies 2024, 17, 703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alireza, F.; Mohammad, S.G.; Mehdi, S.; Mehdi, B. Support Vector Machine Based Fault Location Identification in Microgrids Using Interharmonic Injection. Energies 2021, 14, 2317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hajiahmadi, M.; Hooshmand, R.-A.; Kiyoumarsi, A. Voltage Sag Monitor Placement for Fault Location Detection Based on Precise Determination of Areas of Vulnerability. J. Modern Power Syst. Clean Energy 2025, 13, 228–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, B.; Tang, L.J.; Gu, Z.M.; Liu, L.; Wu, Z.S. Research on Distribution Network Fault Location Based on Electric Field Coupling Voltage Sensing and Multi-Source Information Fusion. Energies 2025, 18, 913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, Y.P.; Liu, X.H.; Jia, R.; Huang, Q.; Xiao, G.; Wang, P. Sag Source Location and Type Recognition via Attention-based Independently Recurrent Neural Network. J. Modern Power Syst. Clean Energy 2021, 9, 1018–1031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, P.; Zhang, Z.Y.; Dai, N.Y.; Huang, Q.; Lee, W.J. Robust dynamic equivalent modeling of active distribution network with time-varying parameters. IEEE Trans. Power Syst. 2025, 40, 2014–2026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lan, Z.; Yuan, Y.S.; He, D.; Zeng, J.H.; Yu, X.P. A Fault Location Method for DC Distribution Network Based on Differential Initial Value of Current. South. Power Syst. Technol. 2023, 17, 109–116. [Google Scholar]

- Chang, G.W.; Chao, J.P.; Huang, H.M.; Huang, H.M.; Chen, C.L.; Chu, S.Y. On tracking the source location of voltage sags and utility shunt capacitor switching transients. IEEE Trans. Power Del. 2008, 23, 2124–2131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, H.Q.; Zeng, X.J.; Yu, K.; Li, Z.; Xie, Z.J.; Deng, J. Fault Section Location Method for Distribution Network Based on Multi-Dimensional Waveform Difference Clustering Analysis. South. Power Syst. Technol. 2024, 18, 58–68+97. [Google Scholar]

- Rao, G.K.; Jena, P.A. Novel Fault Identification and Localization Scheme for Bipolar DC Microgrid. IEEE Trans. Ind. Inform. 2023, 19, 11752–11764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yadegar, M.; Zarei, S.F.; Meskin, N.; Blaabjerg, F. A Distributed High-Impedance Fault Detection and Protection Scheme in DC Microgrids. IEEE Trans. Power Del. 2024, 39, 141–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arsoniadis, C.G.; Nikolaidis, V.C. Precise Fault Location in Active Distribution Systems Using Unsynchronized Source Measurements. IEEE Syst. J. 2023, 17, 4114–4125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, K.; Wang, H.F.; Shahidehpour, M.; He, B.T. Block-Sparse Bayesian Learning Method for Fault Location in Active Distribution Networks with Limited Synchronized Measurements. IEEE Trans. Power Syst. 2021, 36, 3189–3203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Zhang, Y.X. Traveling Wave Propagation Characteristic-Based LCC-MMC Hybrid HVDC Transmission Line Fault Location Method. IEEE Trans. Power Del. 2022, 37, 208–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lopes, F.V.; Reis, R.L.A.; Silva, K.M. Improving Traveling Wave-Based Transmission Line Fault Location by Leveraging Classical Functions Available in off-the-Shelf Devices. IEEE Trans. Power Del. 2023, 38, 2969–2972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, Y.X.; Li, Z.W.; Xi, Y.H.; Wu, G.R.; Peng, W.X.; Mu, L.Z. Accurate Fault Location Method for Multiple Faults in Transmission Networks Using Travelling Waves. IEEE Trans. Ind. Inform. 2024, 20, 8717–8728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huo, J.B.; Li, W.; Zhou, Q.L.; Bai, H.; Li, D.; Yuan, Z.Y. Feeder Single-Phase Disconnection Fault Protection Method of Arc Suppression Coil Grounding System Based on Zero Sequence Admittance. South. Power Syst. Technol. 2023, 17, 117–124. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Y.; Wu, X.Y.; Shuai, Z.K.; Zhou, Q.; Chen, H.J.; Shen, Z.J. A Systematic Stability Enhancement Method for Microgrids with Unknown-Parameter Inverters. IEEE Trans. Power Electron. 2023, 38, 3029–3043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Shuai, Z.K.; Liu, X.; Chen, Y.D.; Li, Z.Y.; Hong, Y. Stability Analysis and Location Optimization Method for Multiconverter Power Systems Based on Nodal Admittance Matrix. IEEE J. Emerg. Sel. Top. Power Electron. 2021, 9, 529–538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; He, H. Fault Diagnosis for TE Process Using RBF Neural Network. IEEE Access 2021, 9, 118453–118460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, B.; Yin, H.T.; Zhu, Z.X. Spatio-temporal graph convolutional networks: A deep learning framework for traffic forecasting. In Proceedings of the 27th International Joint Conference on Artificial Intelligence, Stockholm, Sweden, 13–19 July 2018; pp. 3634–3640. [Google Scholar]

| Parameter Type | Sample Parameter Range | Number of Parameters |

|---|---|---|

| voltage sag line | Lines 1–32 | 32 |

| fault location | At 20%, 40%, 60%, and 80% of the line length | 4 |

| fault resistance | 0.01, 2, 5, 10, 20, 50, 80, 100Ω | 8 |

| PV output | 20%, 40%, 60%, 80%, 100% | 5 |

| load level | 90%, 100%, 110% | 3 |

| Fault Type | Accuracy/% | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| LSTM | CNN | GCN | Proposed Method | |

| Single-phase to ground fault | 91.04 | 93.89 | 95.84 | 99.39 |

| Two-phase to ground fault | 90.91 | 94.36 | 96.22 | 99.65 |

| Two-phase short circuit | 91.34 | 93.95 | 96.01 | 99.58 |

| Three-phase to ground fault | 92.07 | 94.96 | 96.78 | 99.82 |

| Three-phase short circuit | 91.26 | 94.55 | 96.64 | 99.71 |

| Change Scenarios | Accuracy/% |

|---|---|

| Connect the connection line between nodes 17 and 32 | 98.33 |

| Connect the connection lines between nodes 17 and 32, and 7 and 20 | 96.92 |

| Connect the connection lines between nodes 7 and 20, and disconnect the line between nodes 19 and 20 | 97.17 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Yao, R.; Bai, H.; Jiang, S.; Liu, T.; Lei, Y.; Zheng, Y. A Two-Stage Voltage Sag Source Localization Method in Microgrids. Energies 2026, 19, 258. https://doi.org/10.3390/en19010258

Yao R, Bai H, Jiang S, Liu T, Lei Y, Zheng Y. A Two-Stage Voltage Sag Source Localization Method in Microgrids. Energies. 2026; 19(1):258. https://doi.org/10.3390/en19010258

Chicago/Turabian StyleYao, Ruotian, Hao Bai, Shiqi Jiang, Tong Liu, Yiyong Lei, and Yawen Zheng. 2026. "A Two-Stage Voltage Sag Source Localization Method in Microgrids" Energies 19, no. 1: 258. https://doi.org/10.3390/en19010258

APA StyleYao, R., Bai, H., Jiang, S., Liu, T., Lei, Y., & Zheng, Y. (2026). A Two-Stage Voltage Sag Source Localization Method in Microgrids. Energies, 19(1), 258. https://doi.org/10.3390/en19010258