1. Introduction

As offshore wind turbines increase in size and are deployed in more complex environments, accurate dynamic modelling becomes essential for structural design, performance evaluation, and control development. These models are to not only capture the internal dynamics of the wind turbine system but also remain computationally efficient to support iterative design, sensitivity analysis, and control prototyping.

Considering the above, frequency-domain model representations offer a valuable balance between fidelity and efficiency. By focusing on the most dynamically significant components, typically the rotor and nacelle, such models simplify the system while retaining the dominant modes of motion, such as blade flapwise and edgewise bending, torsional dynamics, and nacelle inertial effects. These models are especially useful in early-stage design, where rapid feedback on structural behaviour and controller concepts is essential [

1,

2]. Their utility in later design stages or optimisation tasks where a large number of simulations must be performed might be considered as an additional benefit.

The reduced representation serves primarily as an initial verification step focused on the rotor–nacelle subsystem. Its purpose is to validate component-level behaviour and assess the influence of key dynamic interactions before integrating them into the full simulation framework [

2]. Although reduced models can offer some of the benefits of faster parameter sweeps, preliminary sensitivity analyses, and controller development, their main role in this study is to support the refinement of the complete model. Including the nacelle in this simplified representation enhances model fidelity by accounting for inertial coupling and drivetrain-related dynamics while maintaining computational simplicity. This approach therefore serves as a useful intermediate stage in developing more comprehensive simulation frameworks, providing insight into the essential dynamic behaviour of the rotor–nacelle assembly.

A central consideration in dynamic analysis is the choice between time-domain and frequency-domain modelling approaches. Time-domain simulations, widely used in industry-standard tools, allow for detailed, nonlinear representations of wind turbines under arbitrary loading conditions. They are well-suited for simulating transient effects, complex control systems, and stochastic wind loading [

3].

The design and analysis of offshore wind turbines (OWTs) require accurate structural dynamic models capable of capturing the coupled interactions between aerodynamic loading, structural flexibility, and control systems. Two main approaches dominate the modelling landscape: time-domain simulation tools and frequency-domain analysis methods.

Time-domain simulation remains the industry standard for detailed nonlinear modelling. Tools such as OpenFAST (developed by NREL) [

4], HAWC2 (from DTU) [

5], and Bladed (by DNV) [

6,

7] enable comprehensive aero-hydro-servo-elastic simulations. These tools can capture unsteady aerodynamics, control responses, and interactions with turbulent wind and wave fields, making them indispensable for many aspects of dynamic analysis. Recent advancements in these tools focus on enhancing their modularity, fidelity, and computational efficiency. NREL’s FAST Modularisation Framework has improved the interoperability of its modules, allowing for different time steps and integration schemes [

8,

9,

10,

11]. New modules like BeamDyn have been introduced to model highly flexible composite blades with geometrically exact beam theory, capturing significant deformations, including bend–twist coupling, shear, and extension, which was previously a limitation of simpler blade models like ElastoDyn [

12]. AeroDyn has also seen improvements in skewed-wake, dynamic-wake, and unsteady-airfoil aerodynamics modelling. A notable improvement in simulation capability is achieved through the coupling of OrcaFlex with OpenFAST. Specifically, the OrcaFlexInterface module introduced in FASTv8 allows seamless data exchange between the two tools, enabling comprehensive time-domain simulations that capture the fully coupled behaviour of floating offshore wind systems [

13,

14].

Despite these advancements, time-domain simulations can remain computationally expensive, particularly when long-duration simulations or probabilistic load assessments are required, motivating the continued search for more efficient alternatives. Challenges also persist in accurately modelling complex phenomena such as extreme sea states, ice loading, and coupled dynamics of floating offshore wind turbines (FOWTs) with their mooring systems, as discussed in recent reviews of OWT research and technology advancements [

15,

16].

In contrast, frequency-domain modelling offers computationally efficient alternative, particularly in early-phase design, controller synthesis, and linear systems analysis. These methods typically assume linearised system behaviour around an operating point and express system dynamics in the spectral domain. Approaches range from analytical closed-form models [

17,

18,

19,

20] to modal decomposition and high-fidelity finite-element method (FEM)-based formulations. Frequency-domain analysis provides a compact and rigorous description of wind turbine dynamics for monitoring and control, making resonances, damping, and stability margins directly visible through power spectral densities and frequency responses [

21]. This is why frequency-domain methods are standard in the vibration-based condition monitoring of rotating machinery, where characteristic defect frequencies in spectra reveal bearing and gear faults without disassembly [

22,

23]. Civil-structure health monitoring likewise relies on frequency-domain decomposition and PSD-based operational modal analysis to extract natural frequencies, damping ratios, and mode shapes of bridges and buildings for long-term damage tracking [

24]. In aerospace, Bode and Nyquist analyses underpin flight-control design and certification, with frequency-domain models used to estimate dynamic derivatives and assess robustness [

21]. These mature applications show that representing system dynamics in the frequency domain enables concise characterisation, robust stability assessment and sensitive fault detection. Wind turbines share many of the same features—rotating drivetrains, flexible structures, and narrow-bands of excitation—so the analogous use of spectral methods (e.g., order analysis of gearbox and generator vibrations, PSD-based monitoring of tower and blade modes, and frequency-domain feature extraction from SCADA data) is theoretically well-justified and already emerging in practice [

25,

26,

27]. Building on this cross-domain experience, frequency-domain approaches can improve sensitivity to incipient faults, support data-driven structural health monitoring, and provide a transparent link between measured spectra, turbine dynamics, and control-system design [

25,

27]. Recent research has focused on developing novel frequency-domain methodologies for FOWTs that consider both wave and wind loads through stress transfer functions. These models often involve linearising critical parameters like rotor thrusts, mooring system restoring forces, and hydrodynamic pressures. Studies show that such approaches can significantly decrease computational time (e.g., 92% reduction with only a 4% difference in results compared to time-domain methods) while offering potential for fatigue analysis and initial design stages [

28]. Furthermore, open-source frequency-domain models are being developed to efficiently represent complete floating wind turbine systems, increasingly focusing on control co-design where the integrated optimisation of the support structure, turbine, and controller can lead to significant design improvements [

29]. DNV also highlights the role of frequency-domain methods in rapid redesign loops during early project stages, especially for FOWT support structure optimisation, by representing the wind turbine as a point mass and performing hydrodynamic analysis in the frequency domain [

30].

Simplified models, including rotor-only representations, are commonly employed during early-stage design and control development. These models often assume rigid or decoupled tower and drivetrain dynamics to reduce complexity and improve simulation speed. Studies such as [

31,

32] have shown that reduced-order blade models, derived from FEM, are capable of capturing dominant structural dynamics and are especially useful for pitch control development and flutter analysis. More recent work explores advanced reduced-order modelling (ROM) techniques, including those based on deep learning to approximate nonlinear monopile dynamics or unsteady pressure on turbine rotor blades, significantly reducing computational cost while maintaining accuracy over various loading regimes [

33,

34,

35]. Other ROMs focus on aero-hydro-elastic stability analysis for FOWTs, utilising structural modal projection matrices and aerodynamic shape functions derived from finite beam-element methods [

36]. These efforts demonstrate a growing interest in developing highly efficient, yet accurate, models for specific subsystems or phenomena.

Several comparative studies have examined the validity of frequency-domain models against full time-domain simulations. Ref. [

37] compared fatigue loads under steady-state wind using both approaches. More recent validations continue to benchmark frequency-domain models against OpenFAST, showing good agreement for power spectral densities, probability density functions (PDFs), and standard deviations, particularly in the maximum power control region [

38]. Studies also investigate the inclusion of linearised thrust expressions and frequency-dependent damping/inertia terms in frequency-domain models to better capture dynamic effects related to control, showing improved performance compared to constant damping coefficient methods [

38]. Furthermore, system identification approaches using field measurements are being applied to develop, update, and validate simulation models of wind turbines, including modal analysis in the frequency domain to tune and validate model behaviour against deployed turbines [

39].

However, these studies generally focus on full-system models or specific components within a larger coupled framework. What remains unaddressed in the literature is a detailed comparison between rotor-only FEM-based frequency-domain models and time-domain simulations. While frequency-domain methods offer advantages in terms of computational cost and analytical insight, their accuracy when used in isolation, particularly for the rotor subsystem, has not been systematically evaluated. This creates a gap in understanding how well such reduced models perform in capturing rotor dynamics under realistic offshore conditions, and whether they can be reliably used for tasks like preliminary design, control development, or load envelope estimation. To address this gap, the present work proposes and evaluates a rotor-only FEM-based frequency-domain framework, benchmarked against an industry-standard time-domain solver.

In line with this aim, the structure of the paper is as follows. First, the FEM-based rotor–nacelle model is introduced, and the key assumptions, aerodynamic loading, finite-element implementation, and overall spectral-analysis workflow are described. Next, the wind load modelling used to generate the input spectra that drive the frequency-domain response is presented. The setup of the equivalent OpenFAST model and the post-processing of its time-domain results are then outlined to enable a consistent benchmark comparison. This is followed by a set of numerical case studies, in which the modal analysis is reported, the agreement between spectral predictions is examined, and runtimes of the two approaches are compared. Finally, the main findings are summarised in light of objectives, limitations of the current work are highlighted, and directions for future extensions are indicated.

2. Research Objectives

A gap exists in the literature regarding systematic assessments of frequency-domain approaches for utility-scale wind turbines, particularly in terms of their fidelity, limitations, and computational benefits relative to comprehensive full-system time-domain simulations. The present study starts to address this gap by establishing and critically evaluating a rotor and nacelle frequency-domain framework, built around a high-fidelity FEM representation and benchmarked against an industry-standard time-domain solver. In this context, the following four specific objectives are defined:

Develop a high-fidelity rotor–nacelle FEM frequency-domain model of the NREL 5-MW reference turbine, including flexible blades, shaft/nacelle flexibility, and linearised pitch/torque control;

Couple blade element-momentum aerodynamic loads and turbulent-wind spectra with the structural model to obtain transfer functions and spectral responses for key outputs (blade-root moments, tip deflections, shaft torque);

Benchmark the frequency-domain predictions against an equivalent OpenFAST time-domain model under defined IEC turbulent-wind cases, comparing modal frequencies/damping, power spectral densities, and response statistics;

Quantify computational effort relative to OpenFAST and discuss when the frequency-domain model is sufficiently accurate for early-stage design and control tasks.

Taken together, these objectives define a coherent framework for assessing rotor and nacelle frequency-domain models in a way that is both physically meaningful and directly comparable to established time-domain practice. By explicitly linking component-level dynamics, spectral characteristics, and computational effort, this study aims to clarify the conditions under which such reduced models can be reliably employed in offshore wind turbine analysis and design.

This paper compares response spectra and standard deviations of a rotor–nacelle model. Future papers will extend the comparison to extreme and fatigue response statistics, examine damping in more detail, compare results for the coupled floating hull-turbine model, and present results for the frequency shifting that occurs at the main shaft to nacelle connection.

Dynamic fidelity is evaluated on matching outputs in both models: blade-tip deflection, blade-root bending moments (flapwise and edgewise), rotor speed, generator torque, blade pitch, and azimuth. For each, standard deviations, resultant magnitudes/angles (combining flapwise and edgewise components), and power spectral densities are compared to align modal content and variability, providing a like-for-like benchmark of structural response and control effects.

3. FEM-Based Rotor–Nacelle Model

3.1. Methodology, Computational Model, and Assumptions

The development of a high-fidelity rotor–nacelle model within the frequency domain necessitates clearly defined scope and underlying assumptions to ensure both computational tractability and scientific rigor. This section details the methodological choices, the governing equations, and the structural simplifications adopted for the present analysis.

Modelling assumptions and their expected impacts are summarised below:

Scope: Rotor–nacelle only; tower and platform omitted. Largely isolates rotor and power train behaviour and removes tower coupling, tower-shadow effects, and low-frequency global modes/load paths.

Structural formulation: 3-D beams (shear included) with spanwise-varying properties for blades and nacelle. Appropriate for slender members; local 3D flexibility, potentially altering local mode shapes and load distribution.

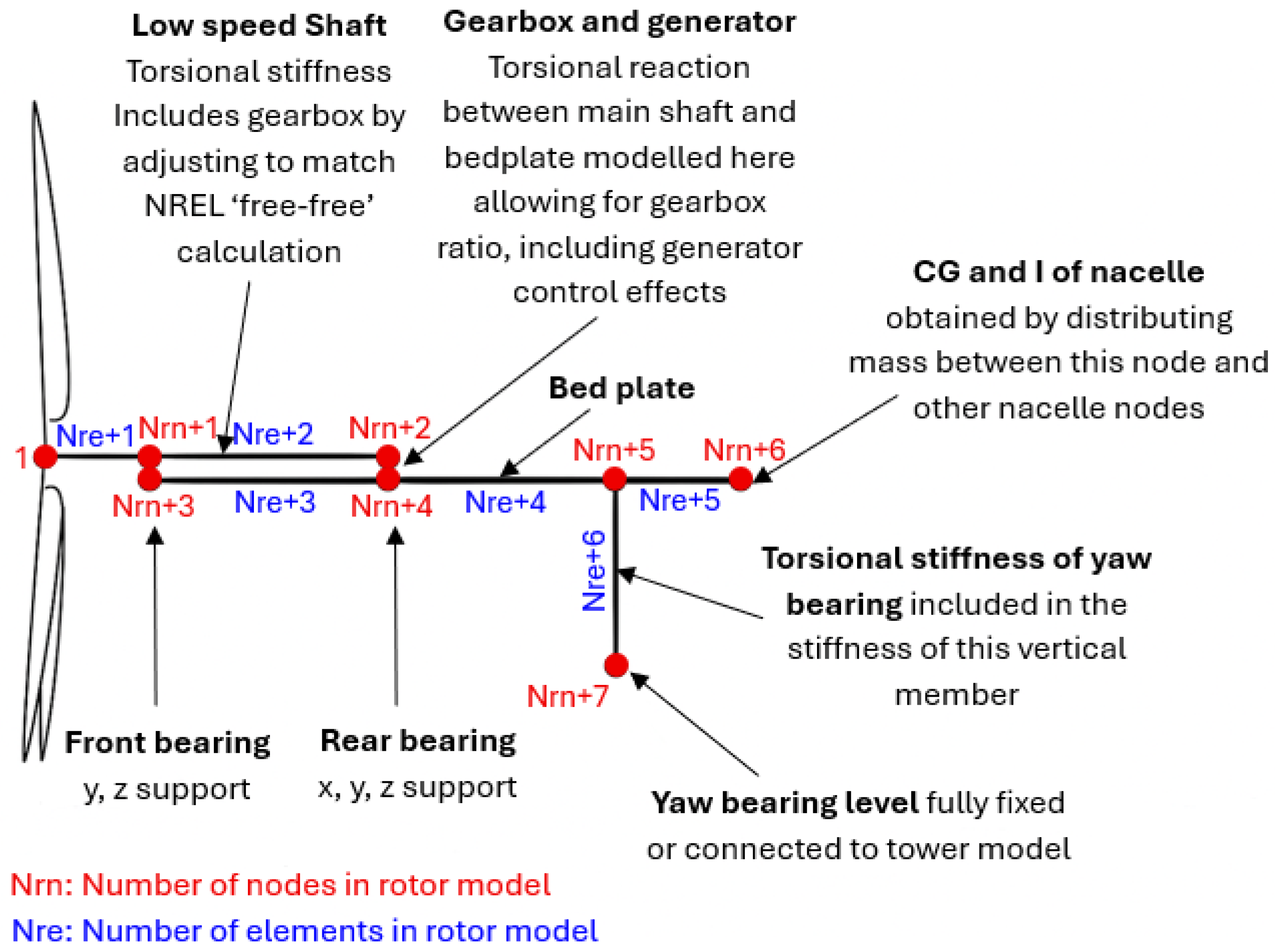

Mass/inertia idealisation: Blade mass is lumped at nodes. This may under-represent shear/rotary inertia in thicker sections and affect higher-frequency modes, but modes presently of interest will be well-modelled, owing to the large number of nodes per blade. Hub mass/inertia is lumped at a single node; drivetrain and nacelle are modelled as connected beam elements to the yaw bearing.

Boundary conditions: Yaw-bearing interface constrained; suppresses yaw compliance and yaw–rotor coupling, raises natural frequencies, avoids the significance of frequency shifts between fixed and rotating parts (although an option in the frequency domain model), and provides a necessary support. Rotor-shaft permitted to rotate relative to the nacelle but fixed laterally to the nacelle by springs. Rotational connection to the nacelle through a damper representing the gearbox and generator. Rotational point inertia at the gearbox end of the main shaft represents the combined inertia of gearbox and generator, transformed to the rotational frequency of the main shaft.

System linearisation: Linear time-invariant second-order model about a mean operating point. Valid for small perturbations; nonlinearities, large pitch excursions, and operating-point shifts may be misrepresented.

Control representation: Input signals low-pass filtered, generator torque mapped to equivalent viscous damping (I/D terms zero for the standard NREL controller); linear PI pitch control (D set to zero in NREL controller), without pitch or pitch-rate limits. It would be expected that the lack of these limits may over-/under-estimate damping, leading to some phase errors and yielding optimistic high-wind or transient responses.

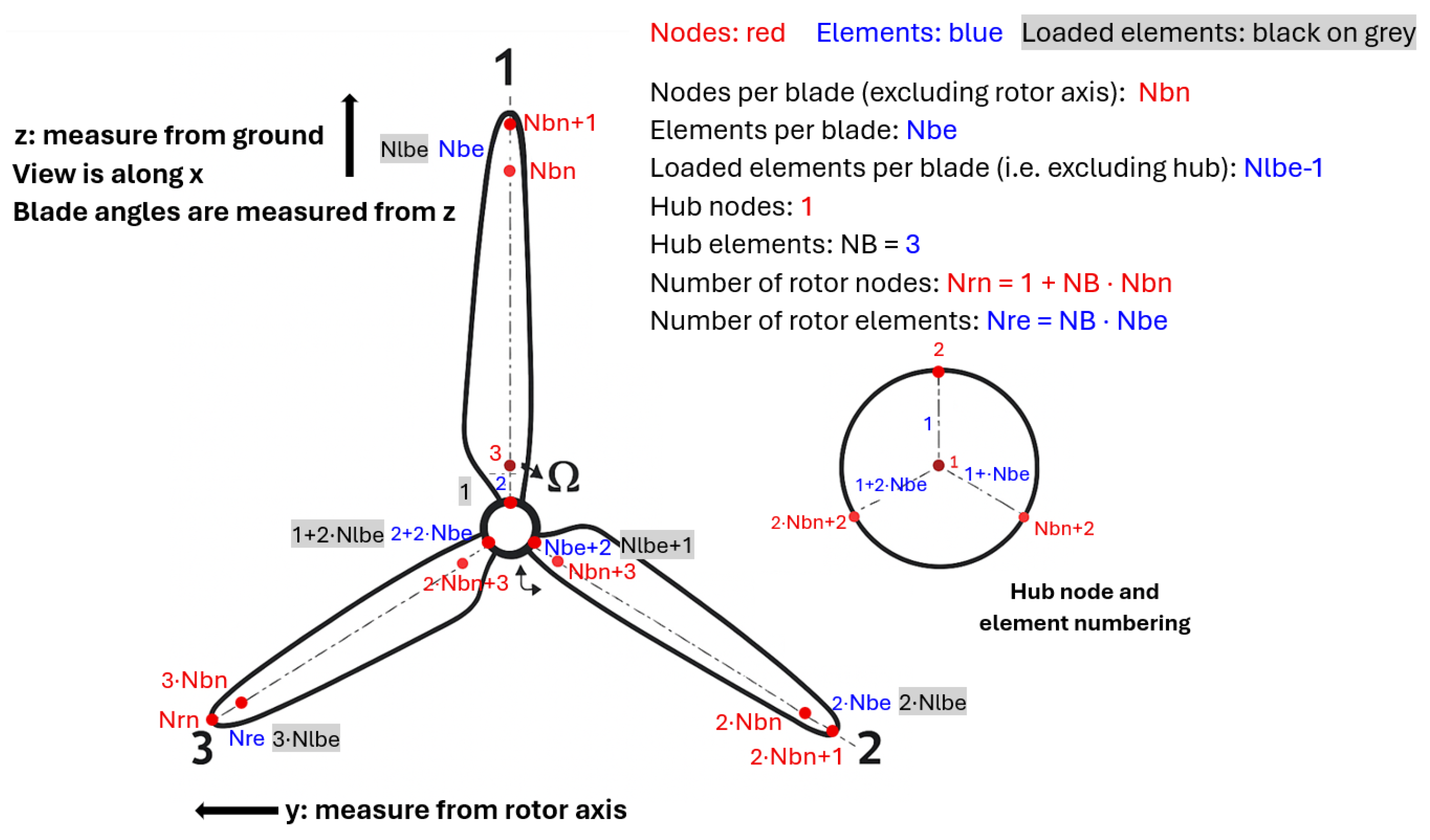

For these types of structures, it is usually convenient to use beam or tube elements. The model is constructed using Euler–Bernoulli 3-D beam finite elements to represent both the blades and the structural components of the nacelle (

Figure 1). Each blade is discretised into multiple beam elements (the number of nodes resulting in elements’ number can be specified) with spanwise-varying stiffness and mass properties to capture flapwise and edgewise bending, torsion, and, where appropriate, axial deformations. Euler–Bernoulli theory, where shear deformation is included, is chosen to reduce model complexity while maintaining sufficient accuracy in capturing the dominant dynamic behaviour of long, slender structures such as wind turbine blades.

Unlike simplified rotor models that treat the nacelle as a rigid body or a lumped mass–inertia system, the present model represents the nacelle as a structural assembly composed of beam elements and nodes, extending from the rotor hub to the yaw-bearing interface. The drivetrain, including the low-speed shaft, main bearing supports, gearbox housing, generator, and bedplate, is modelled using Euler–Bernoulli beams with geometric and material properties. This allows the model to resolve bending and torsional flexibility within the nacelle structure, which can significantly influence the overall dynamic response particularly in low-frequency modes. The hub connects the three blades to the drivetrain and is represented by a node with concentrated mass and inertia properties. This ensures proper coupling between blade dynamics and nacelle motion.

A fundamental assumption in this study is the structural simplification, which explicitly excludes the tower and platform dynamics. This simplification is justified by the study’s focus on the internal dynamic behaviour of the rotor and its interaction with the nacelle, particularly concerning blade flexibility, pitch control, and aeroelastic phenomena. By decoupling the rotor–nacelle system from the global turbine modes (e.g., tower modes, platform rigid-body motions), the analysis can isolate and precisely characterise the high-frequency dynamics and local blade-level responses that might be masked or heavily influenced by the lower-frequency global modes in a full-system model.

To simulate the rotor–nacelle-only configuration, specific boundary conditions are applied. The nacelle is considered constrained at its interface yaw-bearing level (

Figure 2) with the excluded tower, allowing only the rotational degrees of freedom of the rotor shaft and the translational/rotational degrees of freedom of the nacelle relevant to the rotor’s motion. Support constraints are rigorously defined to reflect the isolation of the rotor–nacelle assembly, ensuring that the model accurately represents the intended subsystem without spurious rigid-body modes or unphysical responses from unconstrained degrees of freedom. These constraints are crucial for obtaining a well-posed frequency-domain problem.

The rotor–nacelle dynamics can be modelled approximately as a linearised second-order system exhibiting damped harmonic motion; however, the system is governed by the equation of motion in the frequency domain. The model incorporates the effects of Proportional–Integral–Derivative (PID) control systems, for both generator torque and blade pitch. These control systems are specifically designed to be dependent on the mean wind speed and the excitation frequency. In terms of generator controller characteristic, the generator is converted to an equivalent low-speed shaft rotational damping coefficient, whilst controller integral and differential terms are set to 0. The proportional term of the PID controller is integrated into the system’s damping matrix.

For pitch control, the proportional and integral terms determine the transfer function of the distributed blade load forces. These forces are calculated based on unit pitch changes derived from the BEM analysis. These terms are then converted into asymmetric components that are added to the system’s damping and stiffness matrices. While differential terms can also be included, they are not a requirement for the standard NREL control algorithm, which is the basis for this study. It is important to note that the NREL algorithm includes limiting values (e.g., pitch rate limits) that cannot be directly modelled within a linear frequency-domain framework, though the frequency of exceeding these limits can be assessed [

40].

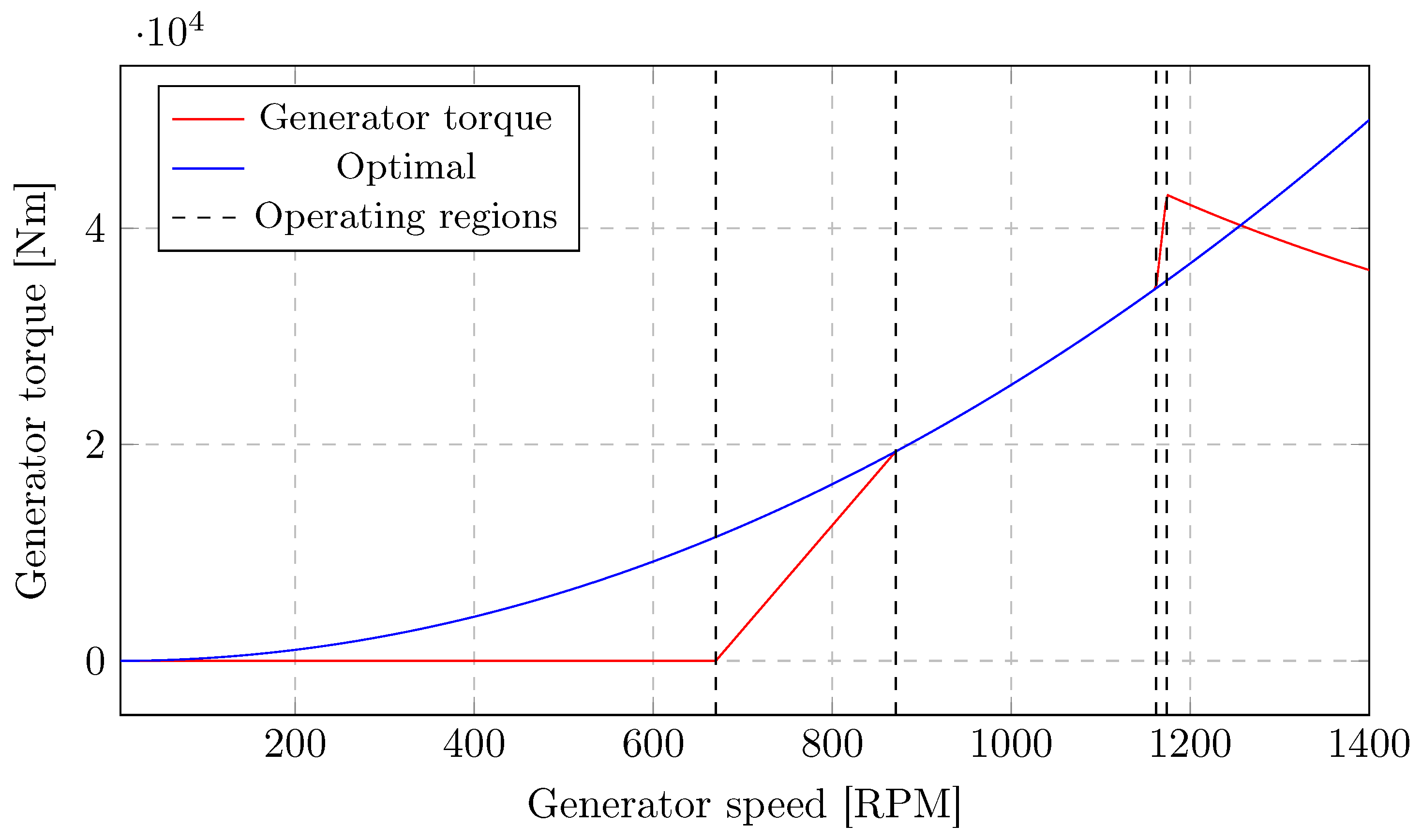

Figure 3 presents the generator controller characteristic in terms of the torque versus speed response of the variable-speed controller.

A structure’s dynamic characteristics can be analysed utilising a frequency-domain approach. The analysis allows to extract modal properties such as natural frequencies, mode shapes, and damping ratios. The method can be applied to linear time-invariant (LTI) systems and the response to harmonic excitation can be then characterised fully analytically. The general form of the time-domain equation of motion for an

n-DOF system is

where

,

, and

denote the mass, damping, and stiffness matrices, respectively, and

is the displacement vector. Assuming a harmonic excitation and a response of the form

, the dynamic equilibrium is presented in Equation (

2). The formula represents a linearised system, typically derived by perturbing the nonlinear equations of motion around a specific operating point (e.g., a constant mean wind speed and rotor speed). This formulation allows the evaluation of frequency response functions (FRFs), eigenfrequencies, and mode shapes of the considered structure:

where

is the global mass matrix, representing the inertial properties of the rotor and nacelle components,

is the global damping matrix, encompassing both structural damping and linearised aerodynamic damping contributions,

is the global stiffness matrix, accounting for the elastic properties of the blades and the rigid body stiffness of the hub and nacelle,

is the excitation frequency (angular frequency in rad/s), representing the frequency at which the system is being analysed,

i is the imaginary unit,

is the complex-valued vector of nodal displacements and rotations in the frequency domain,

is the complex-valued vector of external forces (e.g., linearised aerodynamic forces, control inputs) in the frequency domain.

The matrix expression in Equation (

2) formulates the frequency-dependent dynamic stiffness (impedance) matrix

, which governs the steady-state response of the system under sinusoidal loading. For undamped systems

, the free vibration problem

reduces to the classical generalised eigenvalue problem. The solutions to this problem yield eigenvalues

from which the undamped natural frequencies

are obtained, and corresponding eigenvectors

, which represent the undamped mode shapes.

In the more realistic scenario of damped systems, the eigenvalue problem becomes complex. It can be formulated in a state-space representation or solved directly from the dynamic stiffness matrix with zero external force:

The eigenvalues obtained from the complex-valued system in the frequency domain are, in general, complex numbers:

where

is the (negative) decay rate and

is the damped natural frequency. These complex eigenvalues characterise both the oscillatory and dissipative behaviour of the system. The modal damping ratio

is computed as

where

is the undamped (natural) frequency.

Eigenvalues and damping ratios are crucial in order to assess the stability, transient response, and energy dissipation characteristics of the considered dynamic system. Eigenvectors carry not only the magnitude of displacement information for each degree of freedom within a mode but also the phase relationships between these displacements. It is worth noting that the phase information is vital for understanding the true, time-varying deformation pattern of a damped mode, as different parts of the structure may not reach their peak displacements simultaneously.

This frequency-domain formulation is integral to modal and stability analysis across various engineering disciplines, especially in the case of aeroelastic rotor dynamics analysis. It enables the efficient evaluation of resonance conditions, assessment of damping performance, and quantification of mode-specific energy dissipation.

3.2. Aerodynamic Loading Based on Blade-Element-Momentum Theory

Aerodynamic loading in operating conditions is introduced via quasi-steady linear gains computed based on a Blade-Element-Momentum (BEM) theory analysis. These gains represent the partial derivatives (unit change) of aerodynamic loads in blades with respect to the following:

local gust velocity;

blade pitch angle;

rotor angular speed.

They can represent either partial changes (where induction factors are held constant) or the full change between two distinct wind speeds, allowing for variations in induction factors. These loading derivatives can be treated as a force (real) on a small part of the structure, across the blade span caused by a unit amplitude sinusoidal wind speed, of frequency f, on that part of the structure.

Equilibrium partial derivatives are used to describe how aerodynamic forces or performance parameters respond to small changes in input variables under steady-state (equilibrium) flow conditions. Unlike dynamic derivatives, which capture transient effects, equilibrium derivatives assume that the flow has fully adapted to the new condition. They are particularly useful for steady-state performance analysis, the static sensitivity of the turbine’s power, thrust, and other forces to changes in operating conditions and control system design in wind turbine modelling.

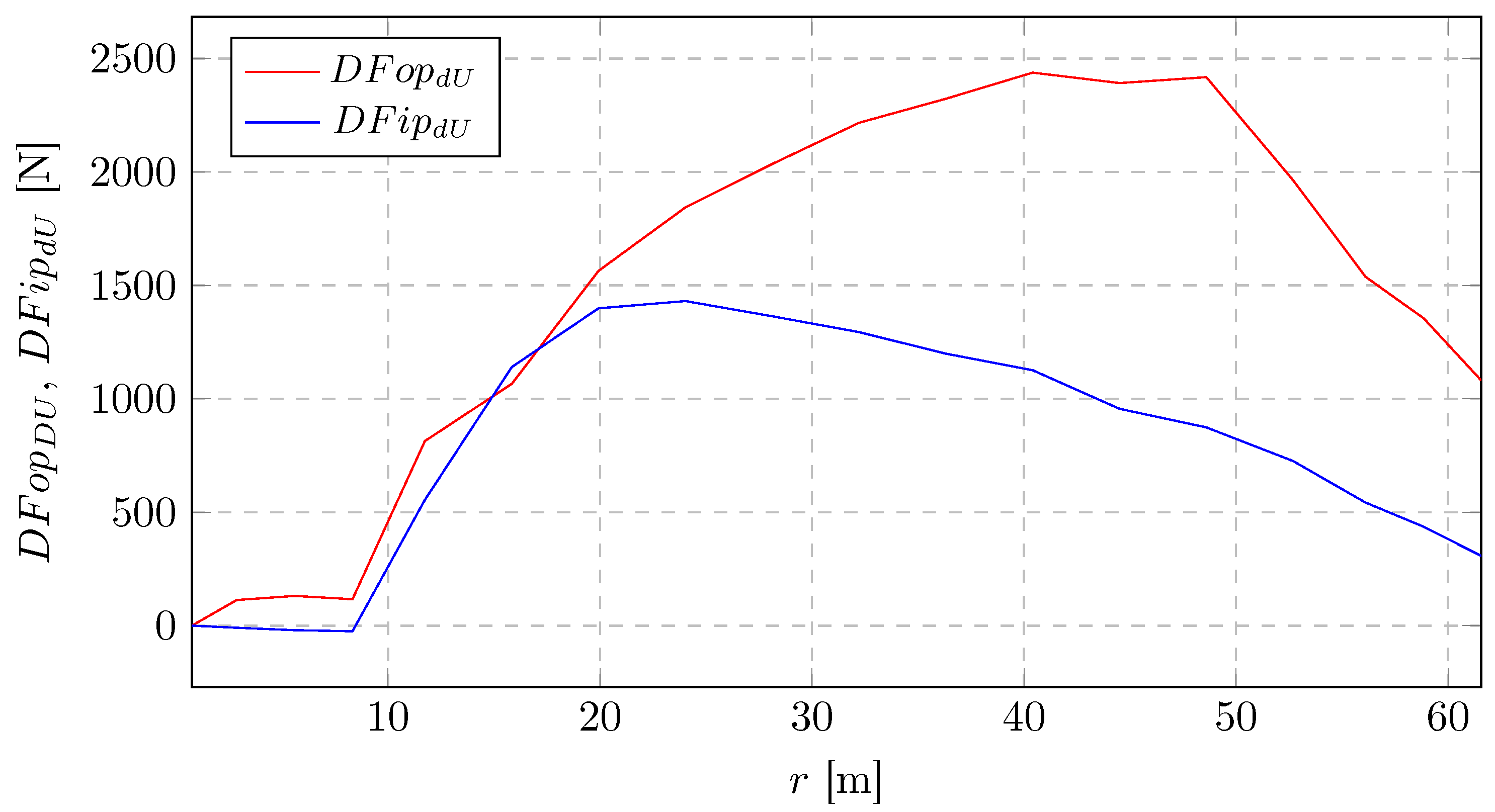

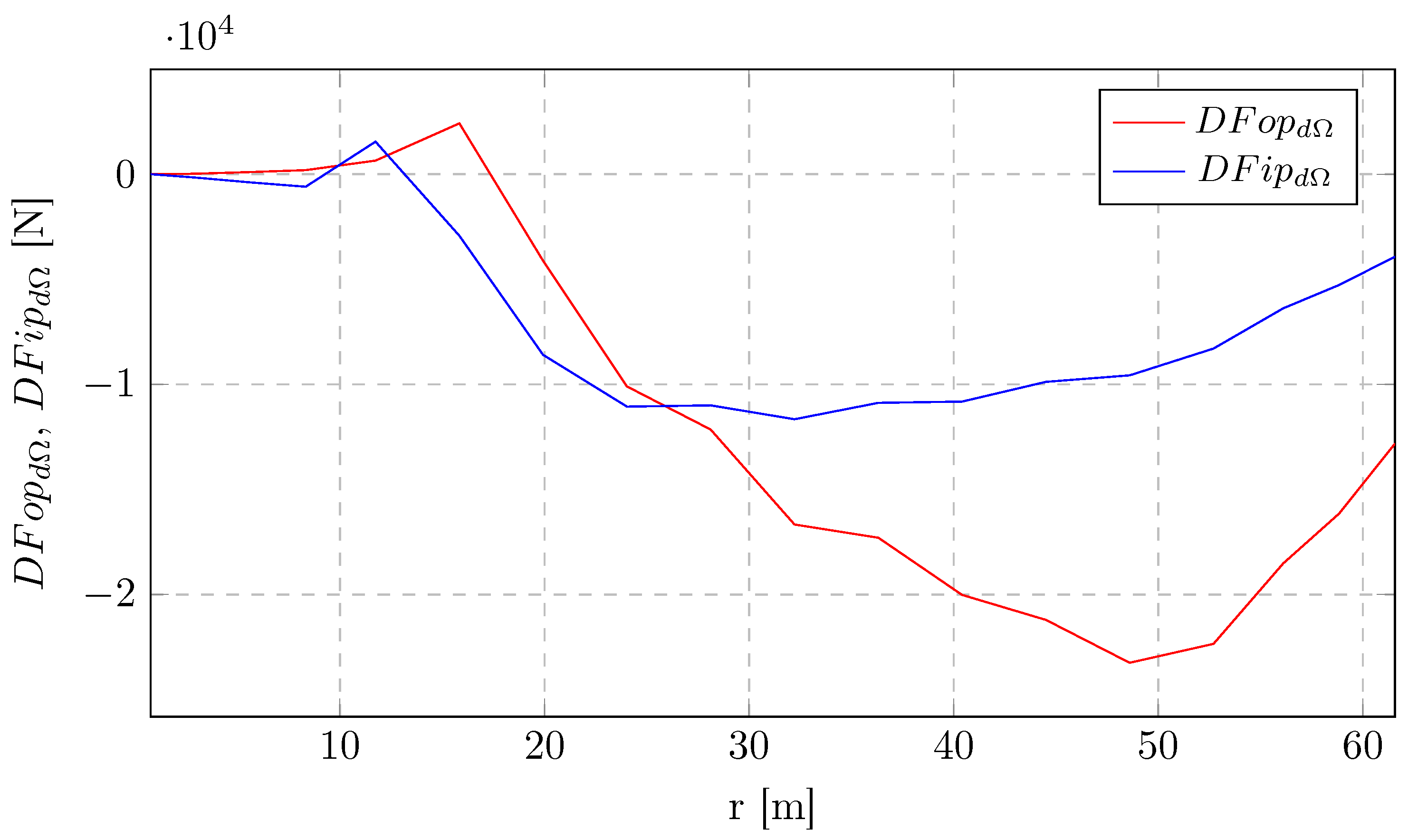

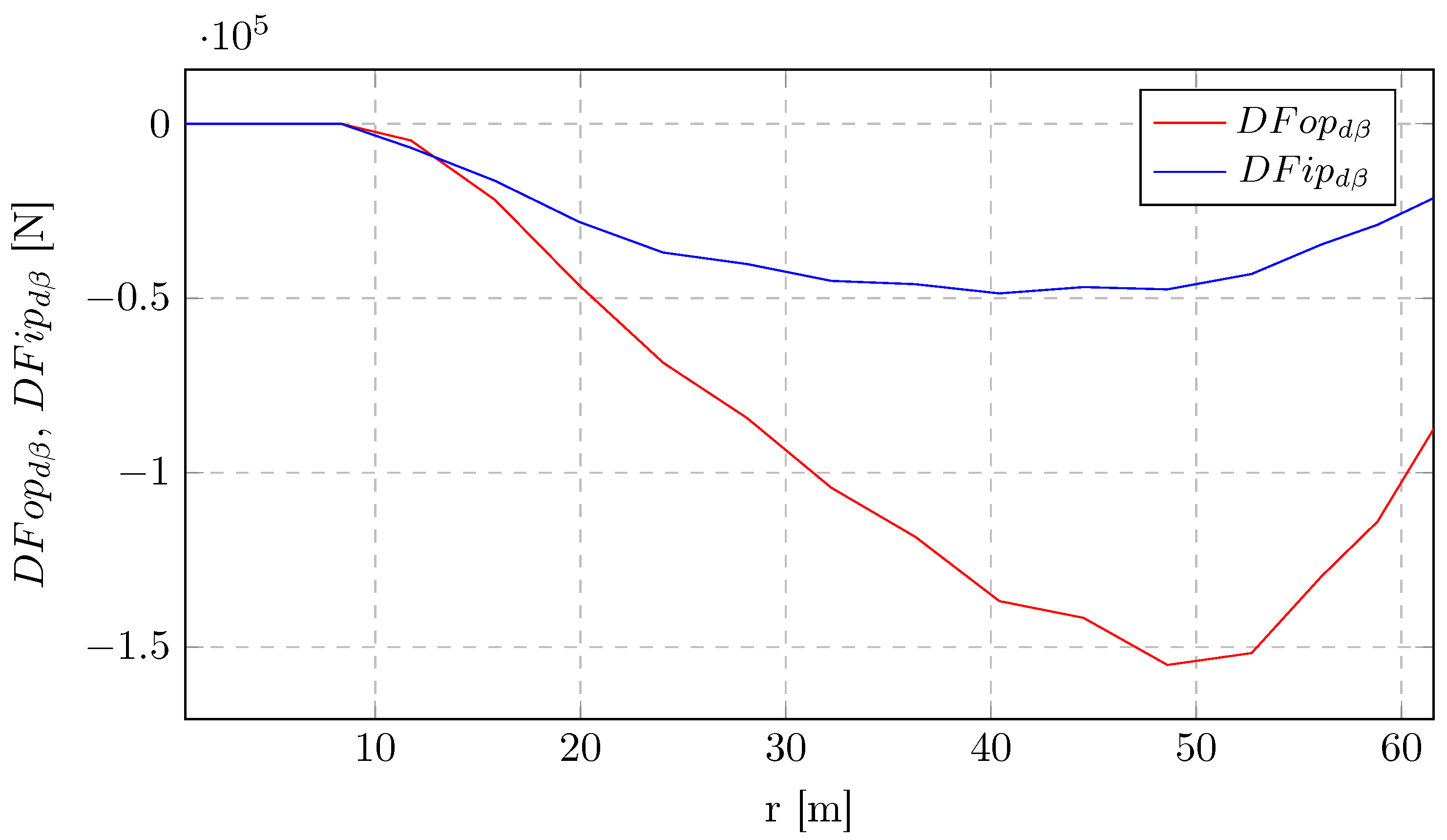

These are presented in

Figure 4,

Figure 5 and

Figure 6 showing the effect of separately changing wind speed

U, angular velocity

, and pitch angle

by

, while allowing the flow to reach equilibrium in terms of axial induction (

a), radial induction (

), and tip loss. The resulting derivatives are shown for both in-plane and out-of-plane aerodynamic forces across the rotor’s blade length.

3.3. Finite-Element Implementation

Beam-element theory is the basis of structural analysis used to model slender members that primarily resist bending, shear, and axial loads. Based on classical beam theories, the stiffness behaviour of a beam element is derived from the relationship between applied forces and resulting displacements. The stiffness properties of a beam element can be expressed in matrix form. The element stiffness matrix

defines how the element resists deformation under external loads, capturing both translational and rotational degrees of freedom at each node [

41].

For a 3-dimensional beam element (generally used for most offshore structures) with two nodes—Node 1 (

i) and Node 2 (

j)—each having six degrees of freedom (three translational and three rotational), the matrix size is

. The partitions refer to the coupling between the two ends of the 3D beam element, and the matrix can be written in shorthand form (

4):

Each term in the stiffness matrix represents the force generated in degree of freedom due to a unit displacement applied at degree of freedom , while all other degrees of freedom are held fixed. This interpretation reflects the physical meaning of stiffness as a resistance to deformation. In particular, the partition characterises the stiffness behaviour at the end of a cantilever beam, capturing how that section of the structure responds to localised displacements and loads.

The degrees of freedom (DoFs) at each node are typically ordered as translational displacements , which represent movements along the local , and z axes, followed by rotational degrees of freedom , which correspond to rotations about the local , and z.

For the majority of nodes, a single global axis system is used, typically with the z-axis pointing upward and the x- and y-axes lying in the horizontal plane. However, for some nodes, especially those connected to inclined members, the global axis system may not be the most convenient. In such cases, an alternative (local) coordinate system is preferable.

Since structural elements are not always aligned with the global x-axis, their stiffness matrices have to be defined in their own local coordinate systems, which are oriented at an angle relative to the global axes. To incorporate these elements correctly into the overall structural model, it was necessary to transform local element quantities (such as displacements and forces) into the global coordinate system. This was achieved using a rotation matrix T, which relates the local and global coordinate systems. The transformation matrix allows vector quantities to be rotated from the local into the global system, enabling consistent structural analysis across the entire model.

Assuming the subscripts

and

o denoting quantities in the local (element-associated) and global coordinate systems, respectively, the transformation between these two systems can be achieved through the application of a rotation matrix

T. The transformation of the displacement vector

and the force vector

to the local and global (inverse transformation) coordinate system can be expressed as presented in Equation (

5) and Equation (

6), respectively:

Since the transformation matrix T is orthogonal for purely rotational transformations, its inverse is equal to its transpose . This property simplifies the conversion between local and global coordinates. The transformation is essential for assembling element stiffness matrices, which are typically defined in local coordinates, into the global stiffness matrix used for solving the equilibrium equations of the entire structure.

The transformation of the stiffness matrix is more involved than that of forces or displacements, as stiffness is not a vector quantity but a second-order tensor. Nonetheless, the transformation of the stiffness matrix can be systematically derived by applying the same rules used for transforming force and displacement vectors. By expressing the local force–displacement relationship and substituting the appropriate transformation expressions, the global stiffness matrix can be obtained from its local counterpart through a coordinate transformation. From the transformation relationships established for forces and displacements, the corresponding transformation of the stiffness matrix can be derived. Starting from the local force–displacement relationship,

substituting the transformation expressions for displacements and forces:

Premultiplying both sides of the local stiffness equation by the transpose of the transformation matrix

T (which is equivalent to its inverse due to orthogonality),

recognising that

, the formula presented in Equation (

10) is obtained:

Thus, by the definition of the force–displacement relationship in the global coordinate system, the global stiffness matrix

is given by

The expression presented in Equation (

11) defines the transformation of the stiffness matrix from the local coordinate system of the element to the global coordinate system of the overall structure. This framework enables the consistent treatment of arbitrarily oriented elements within a unified global coordinate system, facilitating the analysis of complex structures with inclined or non-standard geometry.

Both structural mass and any hydrodynamic added mass are applied at the nodal degrees of freedom. This method assigns discrete mass values directly to the translational and rotational freedoms at each node. Achieving accurate results using the lumped mass approach may require a large number of nodes along each structural member to adequately capture the distribution of inertia.

The individual stiffness matrices are assembled according to their end nodes and corresponding degrees of freedom into a global stiffness matrix. In typical structural analysis, the global stiffness matrix exhibits symmetry about its leading diagonal, which allows most computational frameworks to store and operate only on its upper (or lower) triangular part. However, in the present formulation, the gyroscopic and Coriolis matrices, later combined with the mass, stiffness, and damping matrices, are not symmetric. Consequently, both the upper and lower parts of the matrix must be stored and processed.

To improve accuracy without nodal refinement, a more advanced and consistent mass distribution method is often employed. This approach takes into account the actual distribution of mass along the element length and provides a more realistic dynamic representation.

The transformation of an element matrix from local to global coordinates is performed using a rotation matrix

T, following the same procedure used for stiffness matrix transformation:

This applies to second-order tensors such as mass, damping, and stiffness matrices, ensuring that local element behaviour is correctly mapped to the global coordinate system. To model the energy taken out by the generator and torsional energy dissipation in the drive shaft, damping is applied between connected nodes using a torsional damping constant. This captures relative rotational motion, enhancing the dynamic model’s accuracy for driveline vibration predictions. To incorporate aerodynamic damping into the structural dynamic model, local element damping matrices were constructed based on linearised aerodynamic force responses to small velocity perturbations. These were derived from the sensitivity of aerodynamic forces to both translational and angular velocities in the in-plane and out-of-plane directions of each structural element.

The element-wise aerodynamic damping matrix was structured as a matrix. These terms specifically capture aerodynamic resistance to in-plane translational and rotational motion, including limited coupling between them. These terms were computed using the in-plane and out-of-plane force derivatives , scaled by respective damping factors, and normalised by the local blade radius where appropriate.

After computing each element’s local aerodynamic damping matrix, these were assembled into the global aerodynamic damping matrix. This assembly process follows the same procedure as the stiffness matrix construction, including the necessary coordinate transformations from local element axes to the global structural coordinate system.

The resulting global aerodynamic damping matrix was subsequently added to the structure’s frequency-dependent global damping matrix, allowing the model to account for aerodynamic energy dissipation in both in-plane bending and rotational modes. Centripetal forces were also included, effectively increasing the blades’ flexural stiffness. In addition, gyroscopic and Coriolis effects were represented by asymmetric terms incorporated into the damping matrices. This combined formulation enables a more accurate prediction of aeroelastic damping and mode-specific stability characteristics of the rotating, wind-excited rotor.

3.4. Frequency-Domain Spectral Analysis

Frequency-domain methods offer a range of advantages that make them particularly attractive for early design and control-oriented studies. Moreover, the frequency-domain approach is well-suited to analytical insights, as the system’s behaviour can be decomposed into contributions from individual moves aiding physical interpretation.

However, their primary limitation lies in their inherent assumption of linearity, which may not adequately capture the full range of nonlinear behaviours experienced by OWTs, particularly under extreme or transient loading conditions or when dealing with highly turbulent wind fields and complex wave–structure interactions that introduce significant nonlinearities. Nevertheless, for system-level understanding and the efficient evaluation of numerous design scenarios, frequency-domain models remain highly valuable and a key objective of this study is to demonstrate that, for the specific scope of rotor dynamics, the discrepancy between their results and those obtained from time-domain software can be negligiby small, making the methodolgy advantageous comparing to time-domain approaches. Transfer functions between unit harmonic wind inputs and turbine response variables are computed across a range of excitation frequencies and spatial positions along the blade radius. These are combined with the wind input spectra through a double summation, resulting in a formula for the Power Spectral Density (PSD) of a desired output (node/element) response:

where

is the transfer function relating wind excitation at blade section i to the structural response;

is the complex conjugate of the transfer function at location j;

is the cross-spectral density of wind fluctuations between blade sections i and j;

is the output power spectral density (PSD) of the structural response.

Once the response spectrum

is obtained, several important statistical properties can be derived, allowing for a reliable assesment between the desired nodes/elements of the considered structure. The key properties are presented in Equations (

15)–(

17):

standard deviation (this metric is critical for fatigue assessments, as it reflects the amplitude of fluctuation in structural response due to turbulent wind loading)

spectral moments (for

)

The zeroth moment gives the variance, while higher-order moments (e.g., ) provide information on mean crossing rates, bandwidth, and oscillation periods. These are useful in fatigue damage estimation and in predicting extreme response events using statistical models such as the Rayleigh distribution for narrowband processes or Dirlik distribution for broad band processes.

All calculations assume a fixed mean wind speed and a corresponding Kaimal turbulence spectrum. The frequency-domain formulation uses positive phase advance for positive frequencies, as is standard in linear system and spectral analysis.

4. Stochastic Modelling of Wind Loads

Most conventional wind load design methodologies treat wind as a static load—a constant force that does not vary with time. However, in reality the wind consists of both a steady mean flow and time-varying fluctuations commonly referred to as turbulence. As a result, actual wind loading on structures includes a combination of static loading from the mean wind and dynamic loading from turbulent gusts. In the analysis and design of wind turbines, it is essential to model turbulent wind fields realistically. These fields are typically characterised as stochastic (random) processes defined by their statistical properties in space and time. Wind velocity can be decomposed into mean wind speed

and fluctuating (turbulent) component

, which can be modelled statistically. Wind decomposition can be expressed as presented in Equation (

18):

To fully characterise a multivariate turbulent wind field, one needs to use some statistical measures—second-order statistics such as auto- and cross-covariance functions. The auto-covariance describes how a wind speed component at a single point correlates with itself at different times while the cross-covariance function captures the statistical dependency between two spatial points or two wind components. It tells how the wind fluctuation at one point (or direction) influences another. The statistical formulas for auto- and cross-covariance functions are presented, respectively, as follows:

where

is a turbulent fluctuation of the wind component i;

is a turbulent fluctuation of the wind component j (different spatial locations or directions);

is a time lag;

is an expectation (statistical average).

In the case of multiblade rotor modelling, the accurate representation of cross-covariance is crucial, as this ensures that wind inputs at various blade positions maintain physically realistic correlations. This, in turn, significantly influences the predicted dynamic loading and fatigue behaviour of rotor components, directly affecting the reliability and lifetime estimation of wind turbines. Both covariance functions types are time-domain counterparts to the PSD and coherence functions in the frequency domain.

The turbulent inflow was represented using the IEC Kaimal spectrum, which is the standard choice for utility-scale wind turbine design and certification [

42,

43]. The Kaimal model is recommended in IEC 61400-1 as the reference one-dimensional turbulence spectrum for onshore and offshore sites, and underpins the definition of the IEC turbulence classes and design load cases [

42]. It is derived from field measurements over flat terrain and has been extensively validated against full-scale atmospheric boundary-layer data, showing good agreement over the range of frequencies most relevant to rotor-scale loading [

44]. In addition, the Kaimal spectrum provides a simple analytical form with a clear dependence on mean wind speed and turbulence intensity, which facilitates the consistent specification of inflow conditions across different simulations and tools. Using the IEC Kaimal spectrum therefore ensures compatibility with established design practice, enables direct comparison with other studies based on IEC load cases, and provides a physically realistic representation of turbulence for the assessment of wind turbine dynamic response.

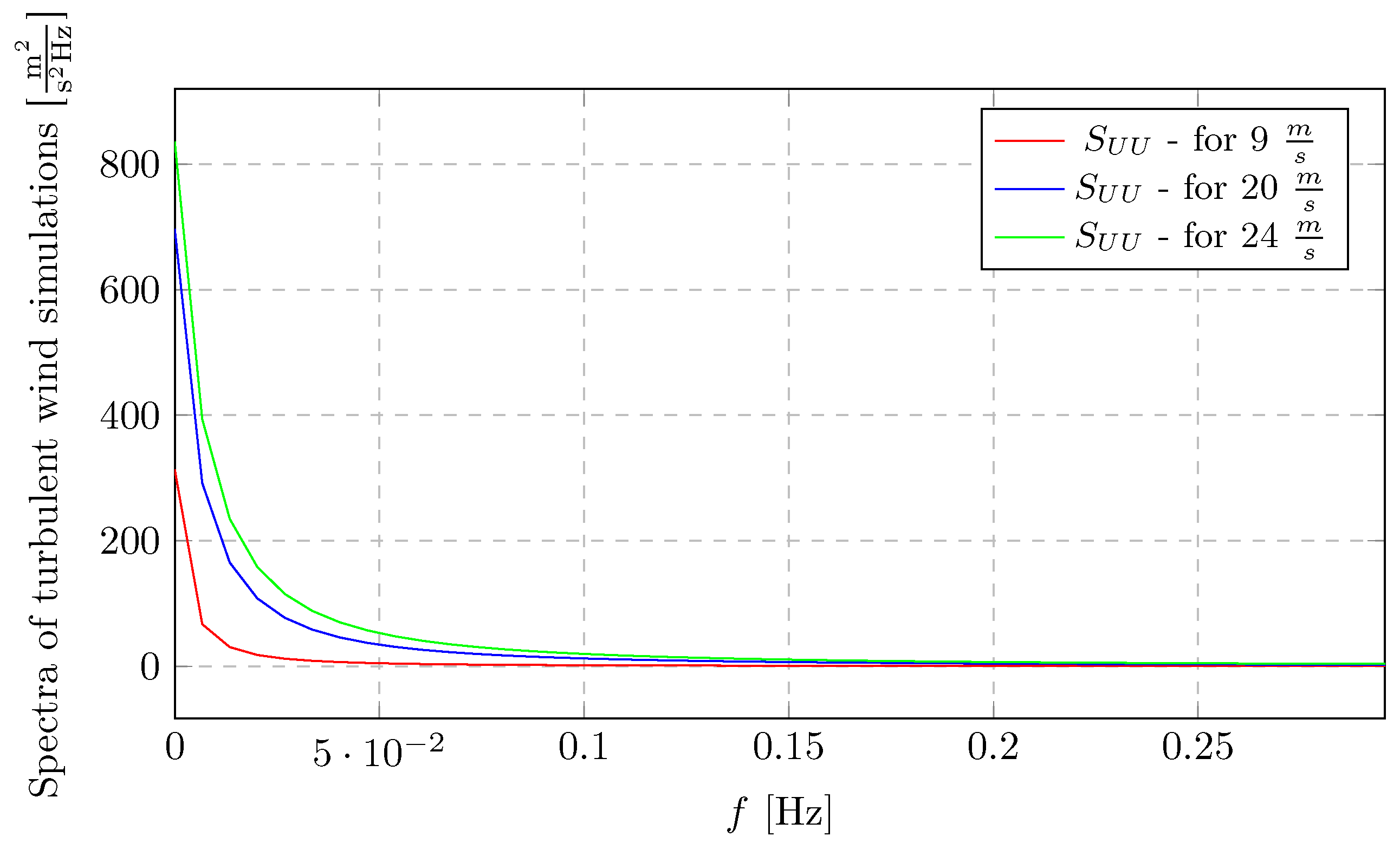

In order to represent the turbulent inflow in a way that is consistent with IEC design recommendations and covers the main operating regions of the turbine, the following key parameters were used in the simulations:

Mean wind speeds: (cover below-rated, near-rated, and above-rated conditions).

Turbulence intensity: (IEC class specification; for realistic variability at hub height).

Turbulence length scale and coherence scale : IEC-recommended values for hub-height turbulence; integral scale and spatial decay set to match IEC design spectra.

Coherence decay constant a: IEC value to enforce the prescribed exponential drop-off with separation r and frequency f.

Bandwidth: spectrum evaluated up to to capture the energy-containing range relevant to rotor dynamics.

Using the IEC Kaimal spectrum and coherence ensures that the FEM-based frequency-domain model and the OpenFAST reference see identical, standard-compliant inflow, enabling a like-for-like comparison of spectral responses and load statistics.

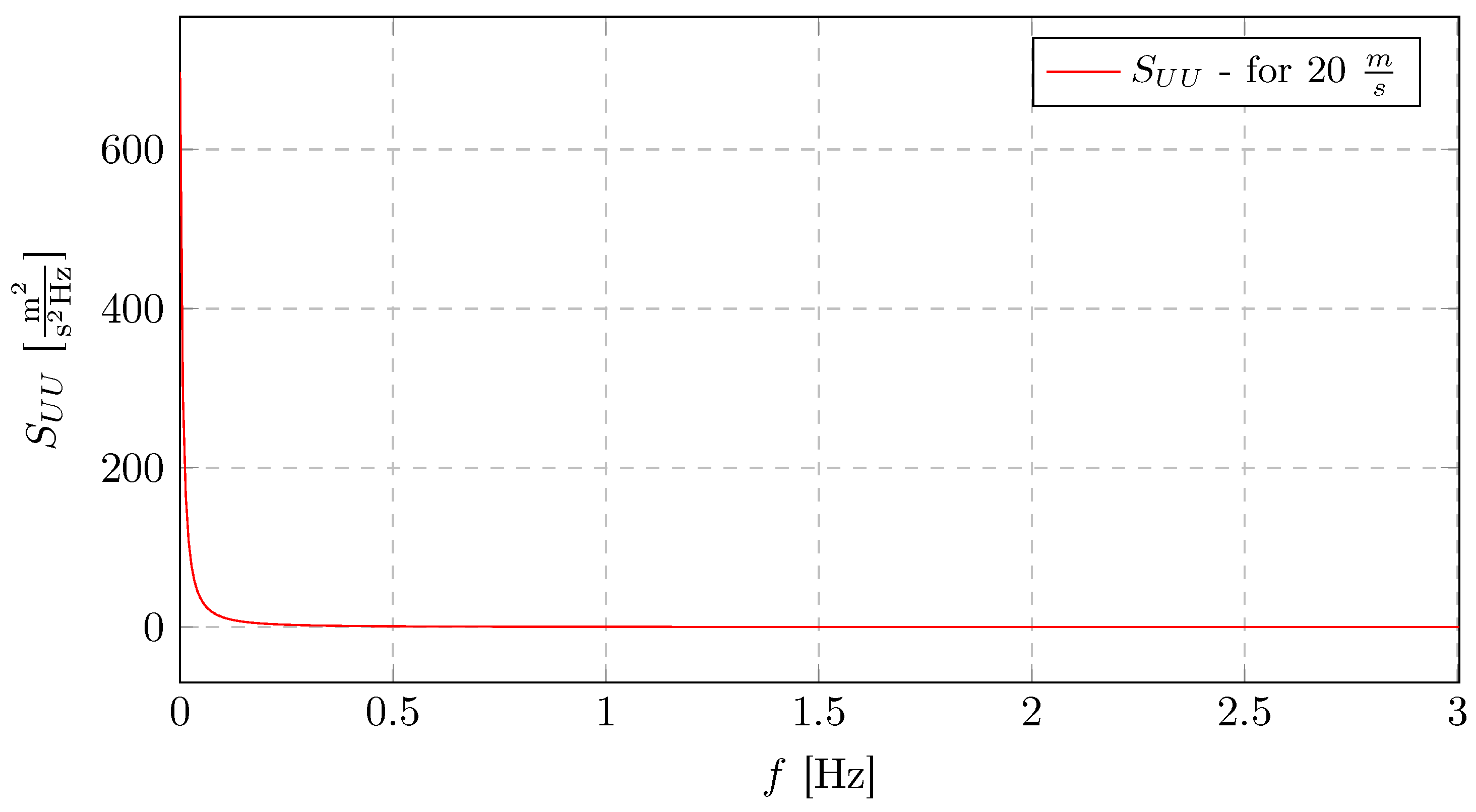

In order to characterise turbulent wind inflow for a dynamic analysis of the investigated model, a systematic procedure based on the IEC-recommended Kaimal spectrum was employed. The process begins with the generation of a target power spectral density for a hub-height wind speed of

and a longitudinal turbulence intensity of

. The Kaimal spectrum formula is presented in Equation (

21):

where

is the standard deviation of turbulence (linked to the specified intensity);

is the turbulence length scale;

U is the mean wind speed;

f is a frequency range.

The spectrum obtained for a range of 3 Hz and

is presented in

Figure 7.

Wind can now be represented by a matrix of cross-spectral densities

representing the frequency-dependent mean of the product of the wind speed at any two points

i and

j in the wind. The cross-spectrum

is computed by multiplying Kaimal PSD with the coherence function

(Equation (

23)), where the coherence is modelled as an exponential decay function with frequency and spatial separation presented in the following equation:

where

a is a constant;

r is distance between points;

f is the frequency of the velocity component;

is a turbulence length scale.

Having the full spectral matrix, one can utilise inverse Fourier transform (IFFT), which enables obtaining the auto- and cross-covariance functions in the time domain, providing a representation of the time- and spatial-correlated structure of the wind field at the blade spanwise positions. This calculation is performed using rotational sampling as described in [

45]. The covariances are calculated using the following distances between the points and accounting for the time lag

:

To investigate the dynamics of blade response in the frequency domain, the Fourier transform (FFT) of these covariance functions should be performed next. This step yields blade auto- and cross-spectra, which determine the input for assessing spatially distributed aerodynamic excitation in simulations and analyses in the frequency domain.

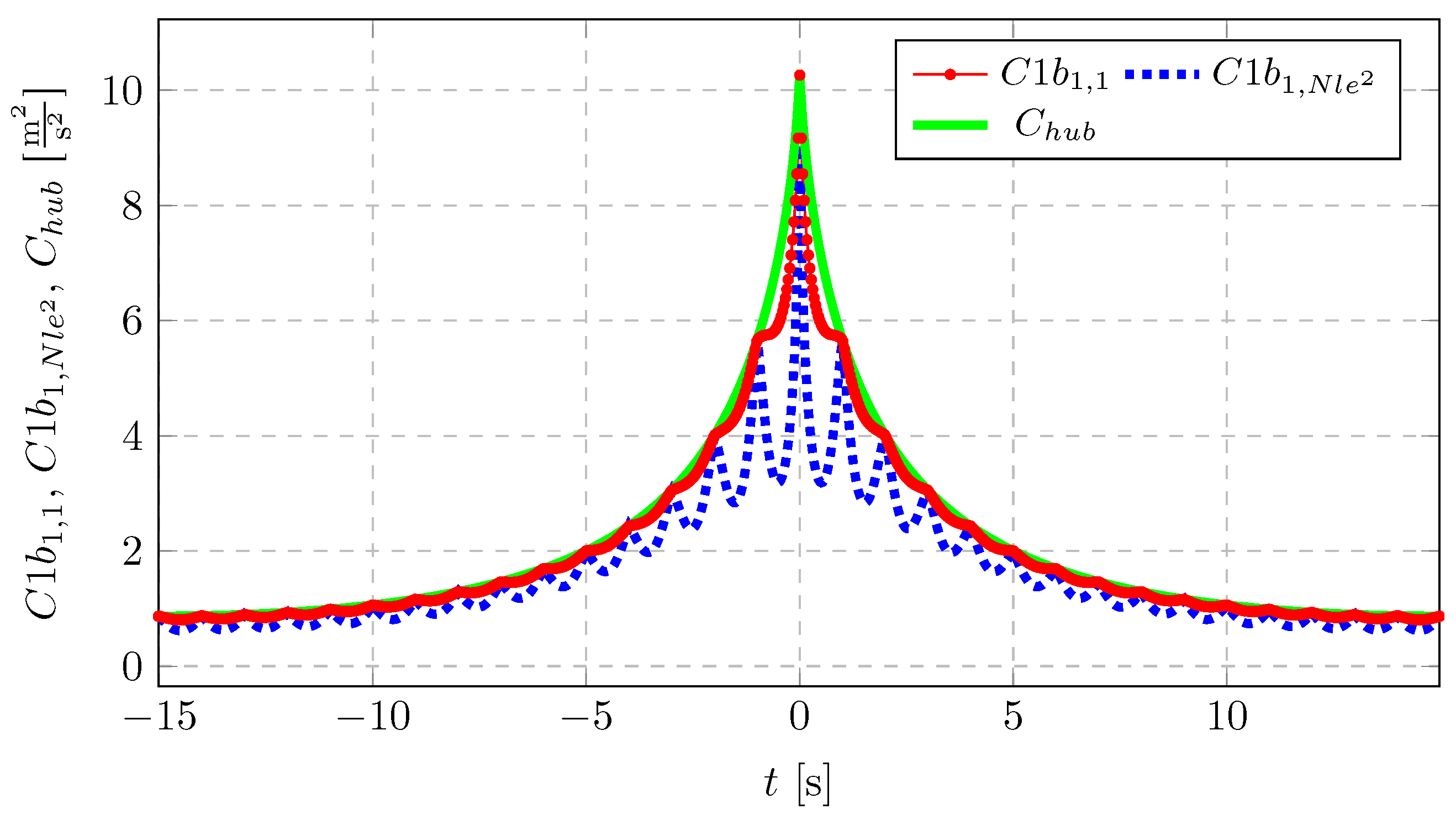

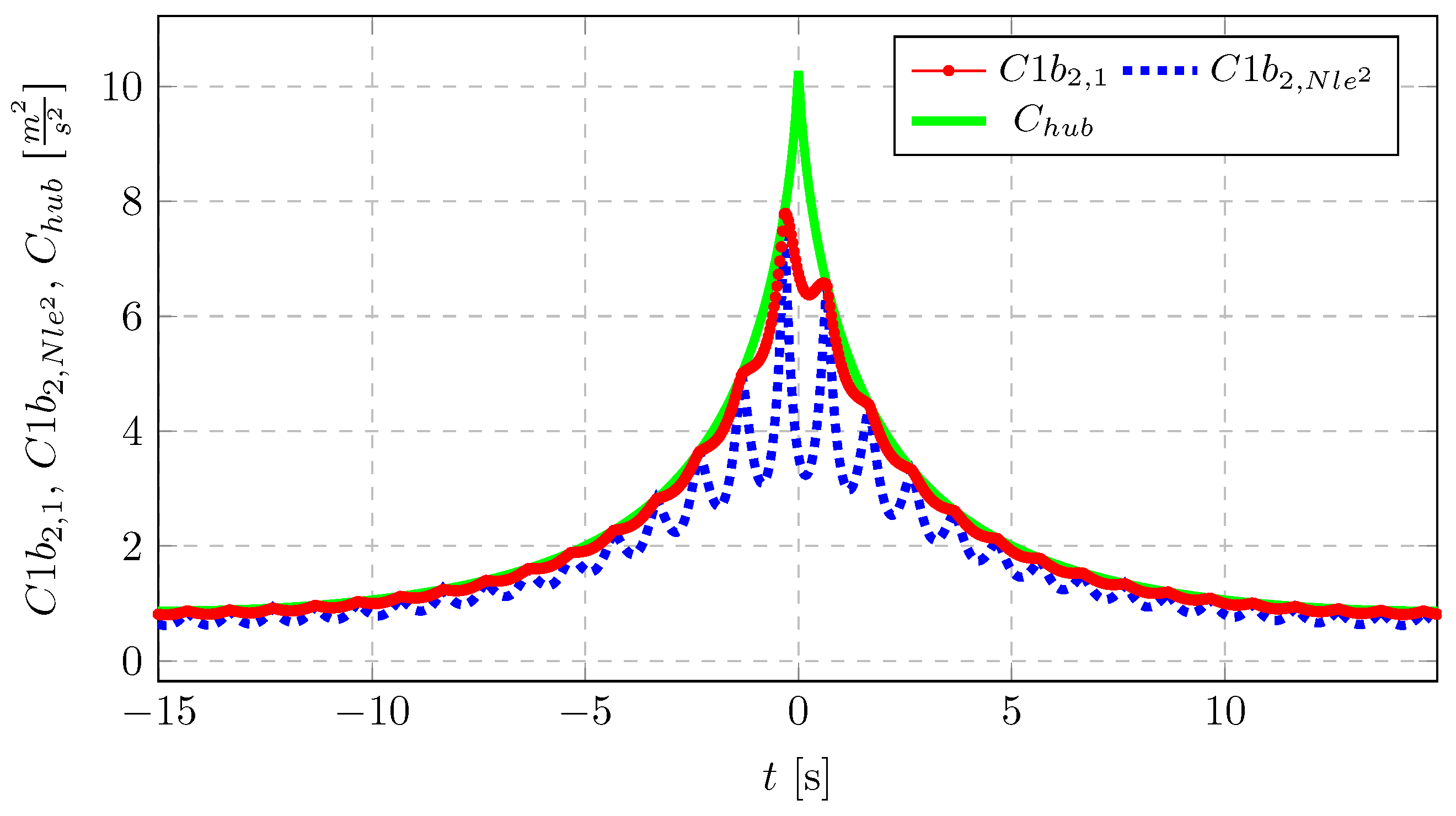

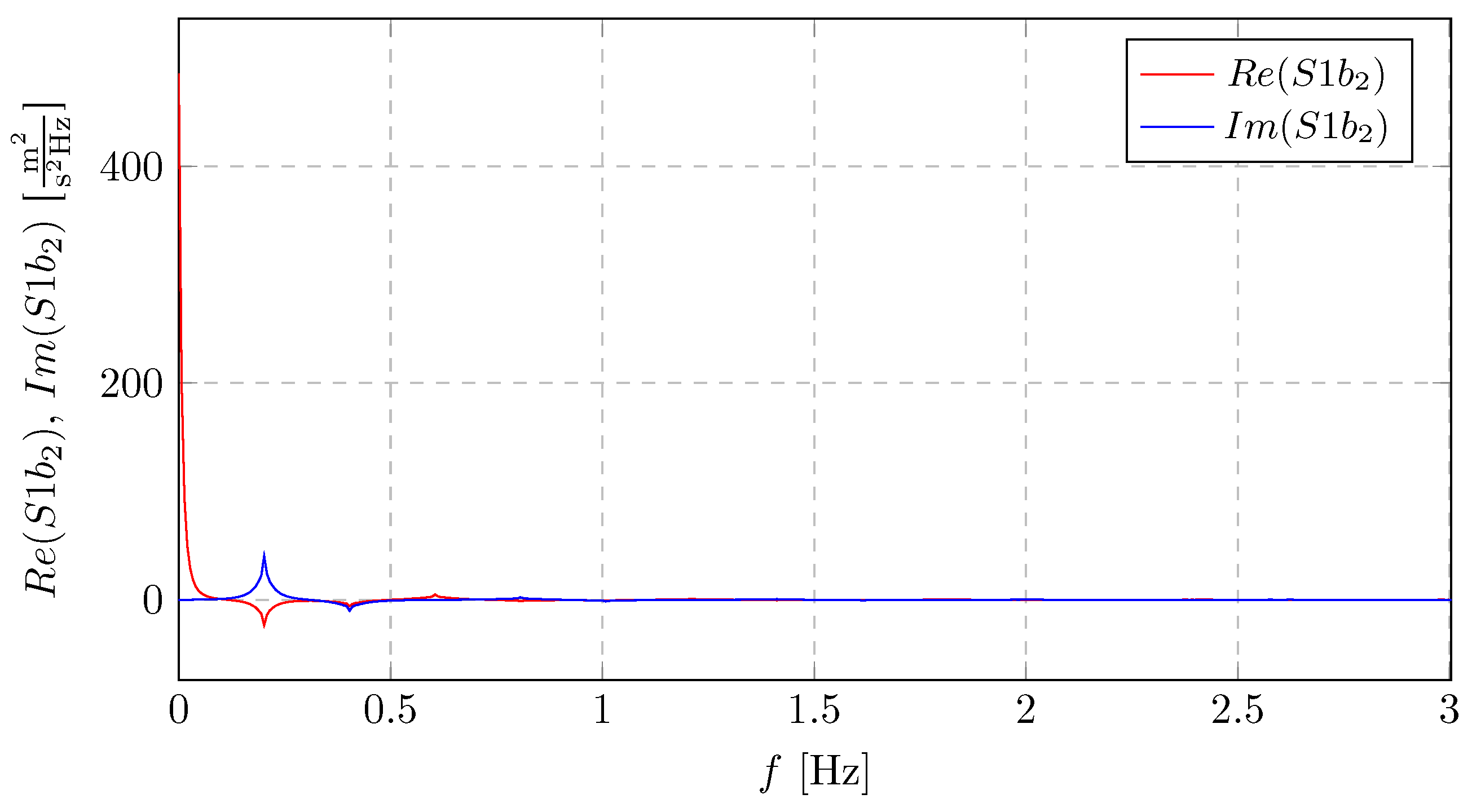

Figure 8,

Figure 9 and

Figure 10 present the simulation results for the auto- and cross-covariance functions, as well as the corresponding spectra.

The combination of the computed wind spectra and relevant transfer functions enables the computation of output spectra (frequency-response functions) or any dynamic quantity of interest, e.g., blade root bending moment, shaft torque, or blade tip deflection.

5. OpenFAST Model Overview—Setup of Equivalent Model

In order to provide a reference model for comparison with the FEM-based one, simulations were performed using the 5 MW baseline wind turbine implemented in OpenFAST. The turbine represents a three-bladed, upwind, horizontal-axis offshore configuration developed by the National Renewable Energy Laboratory (NREL). The OpenFAST model was configured in a simplified form to isolate the rotor dynamics from tower and yaw coupling effects.

In this setup, the tower was modelled as a rigid body and the yaw bearing was fixed, effectively constraining both the tower bending and nacelle yaw degrees of freedom. Consequently, the nacelle orientation remained constant during the simulation. Aerodynamic interaction between the rotor and the tower was disabled, excluding phenomena such as tower shadow and flow blockage. The aeroelastic behaviour of the blades was represented using the BladeDyn module, which accounts for the distributed flexibility and coupled aero-structural response of the blades.

A strict parameter-alignment protocol was applied to ensure that any discrepancies between the FEM and OpenFAST results arise from differences in modelling approach rather than from inconsistent inputs. Geometry and mass properties follow the NREL 5 MW reference definition, including blade span and planform, spanwise mass distribution, hub–nacelle inertias, shaft length, and the bedplate layout. Structural stiffness is matched by imposing the same spanwise flapwise and edgewise bending stiffness () and torsional stiffness () distributions, while nacelle and shaft bending/torsion properties are chosen to correspond to the BeamDyn/ElastoDyn settings in OpenFAST. Structural damping adopts the OpenFAST default values (modal damping ratios or equivalent Rayleigh coefficients), in order to avoid artificial differences in decay rates and power spectral density (PSD) magnitudes. The control laws are harmonised by implementing the same Region 2 quadratic torque law (k), Region 3 torque cap, and identical pitch PI controller gains; any omission of actuator rate limits in the linear FEM-based controller is explicitly noted. Aerodynamic inputs are aligned through the use of identical BEM aerodynamic polars.

The turbulent wind field was generated using the IEC Kaimal spectrum, ensuring the same inflow conditions as those applied in the FEM-based simulations. This setup guarantees consistent aerodynamic excitation in both modelling approaches. As a result, the OpenFAST configuration effectively represents an isolated rotor–nacelle assembly, enabling a focused comparison of rotor aerodynamic and structural responses with those predicted by the FEM-based model, without the influence of tower or yaw dynamics.

In order to process time-domain simulation results derived from OpenFAST, to investigate the dynamic behaviour of the rotor–nacelle system under operating conditions, authors have prepared a post-processing programme based on a Python library [

46,

47,

48,

49]. A two-hour coupled simulation was run in OpenFAST (7200

total simulation time with the first 700

removed to avoid transient effects) to ensure sufficient data for capturing a reliable system response. The study focused on key rotor and nacelle components, including blade tip deflection, blade root moments (

), rotor speed, azimuth angle, generator torque, and blade pitch.

To extract frequency-domain characteristics, the time-series data were first detrended and pre-processed. The processed signals were then transformed into the frequency domain using the Fast Fourier Transform (FFT). Subsequently, spectral representations were analysed to compute statistical parameters—specifically, the standard deviation and mean value of each response.

The result processing methodology enables a direct comparison of response spectra and associated statistical parameters (mean values (), standard deviations (), and higher-order moments ()) between the OpenFAST simulations and the proposed finite-element rotor–nacelle model.

6. Numerical Simulations: Analysis of Rotor–Nacelle

Model

6.1. Rotor–Nacelle Numerical Model

In order to evaluate the performance of the two modelling approaches, a comparative analysis between frequency-domain simulations and nonlinear, coupled time-domain simulations was performed. The coupled simulations were conducted using OpenFAST [

50] under three reference wind conditions, excluding wave effects.

A finite-element method (FEM)-based rotor–nacelle model of the wind turbine was developed by the authors. The analysis was carried out using METHOD [

51], a proprietary computational framework with algorithms implemented in Python (3.11.14). The software is organised into three primary modules:

BEM analysis module—responsible for aerodynamic load prediction;

wind field generation module—for creating deterministic and turbulent wind conditions;

modal and spectral analysis module—for determining system natural frequencies, mode shapes, and damping ratios and computing rotor–nacelle spectral response resulting in power spectral densities (PSDs) for selected nodes or structural components.

The proposed tool provides full analytical transparency, as its formulation is based on documented closed-form solutions.

Following the methodology outlined in

Section 3.3, three case studies were prepared. Aerodynamic steady-state fields were computed using BEM theory, as presented in

Section 3.2. Turbulent wind fields with a fixed nacelle (at the yaw bearing level) were generated for three selected hub-height mean wind speeds—9

, 20

, and 24

. These wind fields were created based on the Kaimal spectrum with IEC turbulence class and an intensity level of 16%, as described and justified in

Section 4.

The rotor–nacelle assembly in the FEM model is discretised with 18 nodes per blade (17 beam elements), and a preliminary refinement study confirmed that this resolution converges the first three flapwise, edgewise, and torsional modes within 1% in frequency. The nacelle–shaft system is represented by 8 nodes (hub, front and rear bearings, gearbox, generator, bedplate and yaw interface), resulting in a total of 62 nodes and 372 degrees of freedom (6 per node), and stiffness, damping, and mass matrices of size

. This discretisation is sufficiently dense to capture blade bending, torsion, and shaft–nacelle flexibility, while keeping the frequency-domain matrix inversions computationally tractable. Control settings within the FEM model follow the NREL 5 MW baseline as presented in

Table 1. The corresponding simulation parameters are listed in

Table 2. Yaw is fixed and the tower is treated as rigid to isolate rotor–nacelle behaviour. All remaining simulation parameters (e.g., inflow and turbulence characteristics) are quantified and justified in the corresponding modelling section (

Section 4).

Figure 11 illustrates the rotor-averaged wind speed PSDs (

) for the three wind speeds considered. A pitch and generator torque controller were implemented according to the procedure described in

Section 3.1, with additional modifications to tuning conditions described in the guidelines [

40]. The main structural and aerodynamic properties of the wind turbine model are summarised in

Table 1.

6.2. Comparative Study

The dynamic model of aero-servo-elastic rotor–nacelle used in this study incorporates a full dynamic and control simulation framework. The turbine operates in Region 3, corresponding to high wind speeds above the rated ( ), where the rotor is pitch-regulated and torque-limited. In this operational regime, the blade pitch controller actively adjusts pitch angle to maintain constant generator power output, while the generator torque is held at its rated value. The analysis includes full aerodynamic, structural, and inertial effects, including centrifugal and Coriolis/gyroscopic contributions, activated via activation parameters:

—pitch control activation;

—generator torque control activation;

—Coriolis and gyroscopic force factor;

—centrifugal force factor;

—aero damping factor;

—structural (mass/stiffness) damping factors (based on SM, as it is consistent with NREL methodology);

—drivetrain damping factor;

—leading/lagging effect factor.

Aerodynamic and structural damping terms [

52] are enabled (as well, drivetrain damping is incorporated) in the analysis through setting the activation factors to 1. The control system utilises standard NREL-based tuning with active pitch and torque regulation, along with signal filtering and a controller sampling time of

s. A pitch reduction factor

is applied to match realistic NREL controller behaviour.

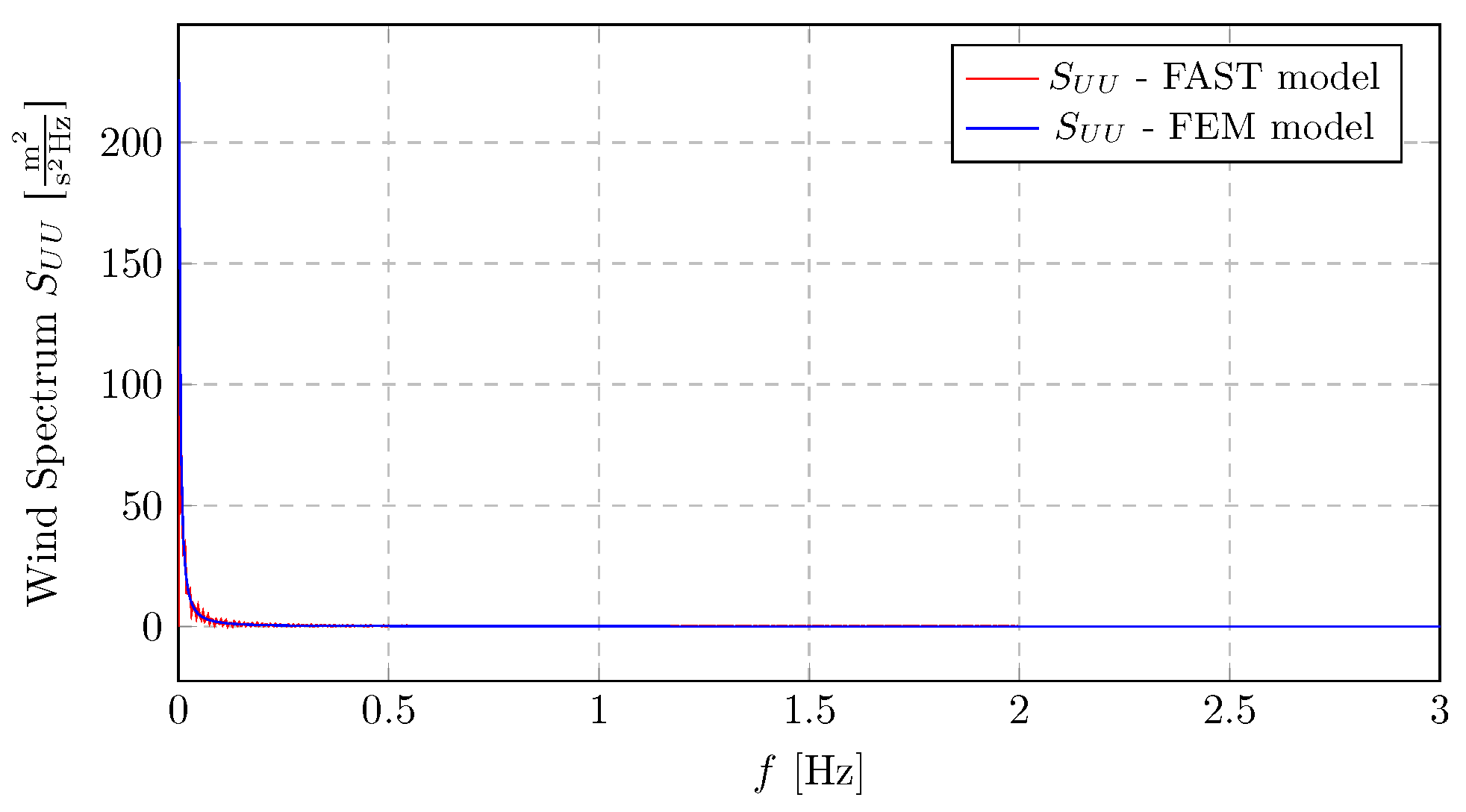

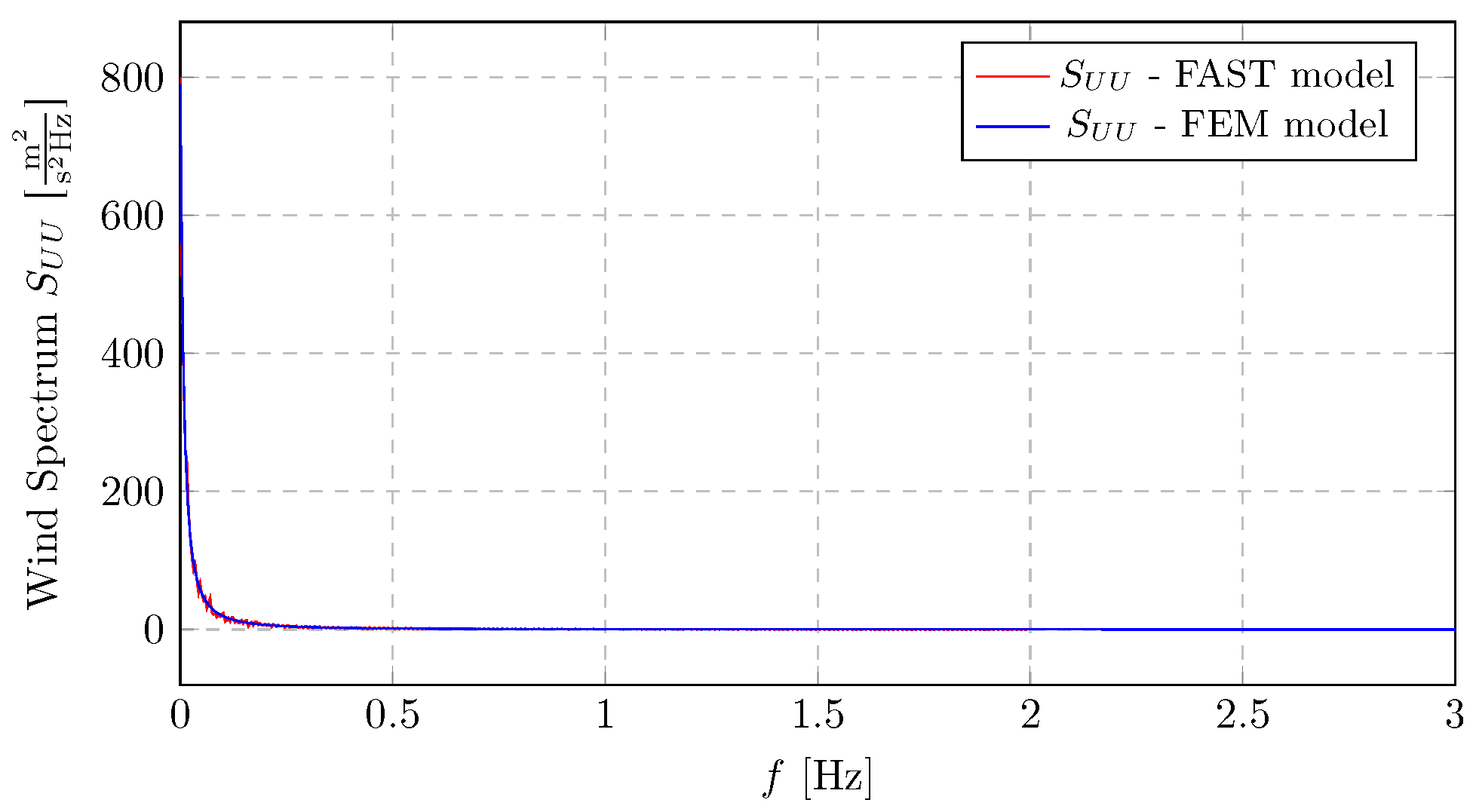

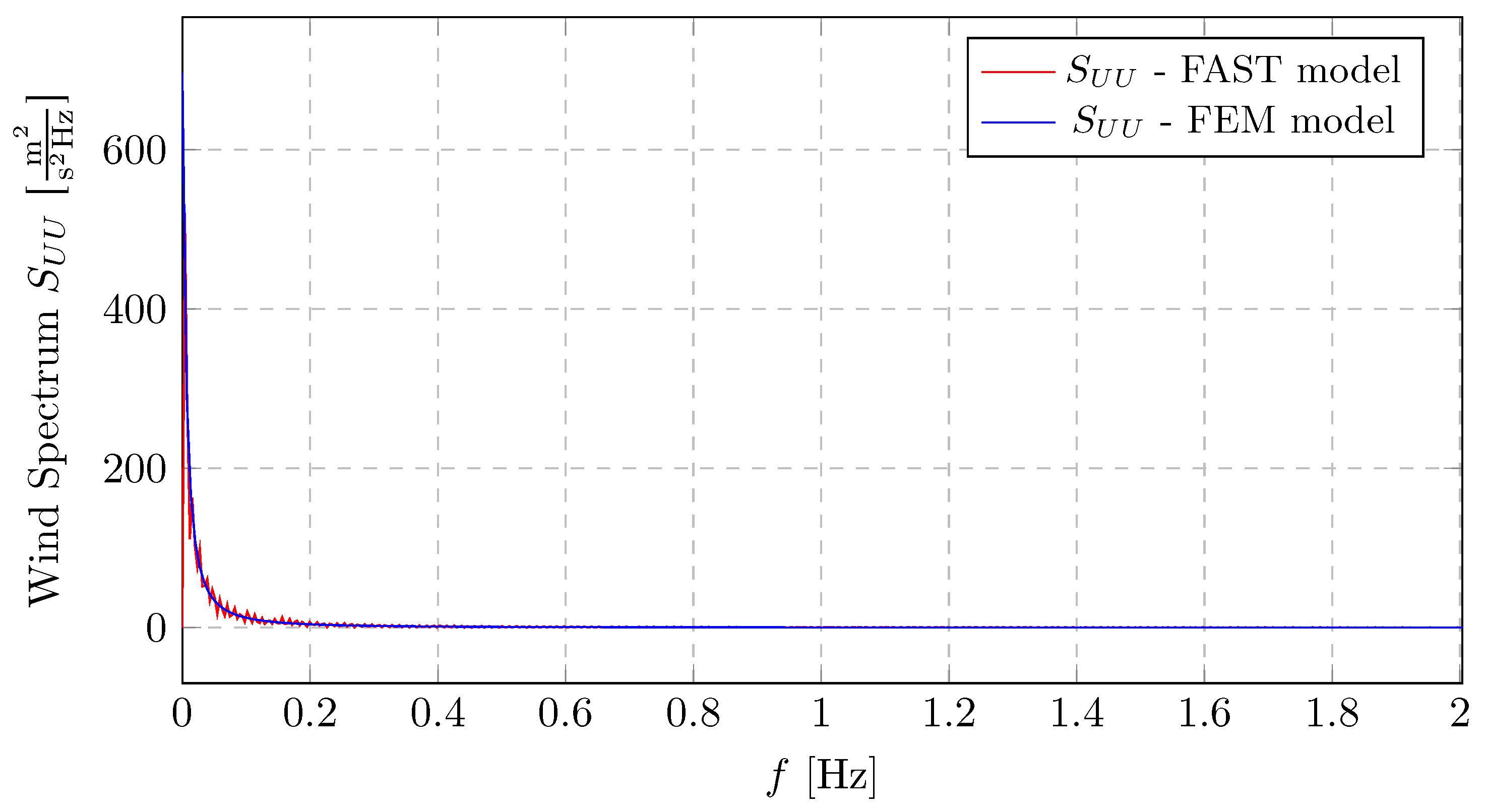

The wind spectrum (

), shown in

Figure 12, displays a typical shape dominated by low-frequency content. Most of the energy is concentrated near low frequencies, where the spectral peak reaches about 600

, rapidly decreasing with higher frequencies. Beyond approximately 0.5 Hz, the spectral energy becomes negligible. This wind field agreement confirms that both simulations were driven by the same turbulent wind input, which is essential for ensuring a valid and consistent comparison of the resulting turbine response.

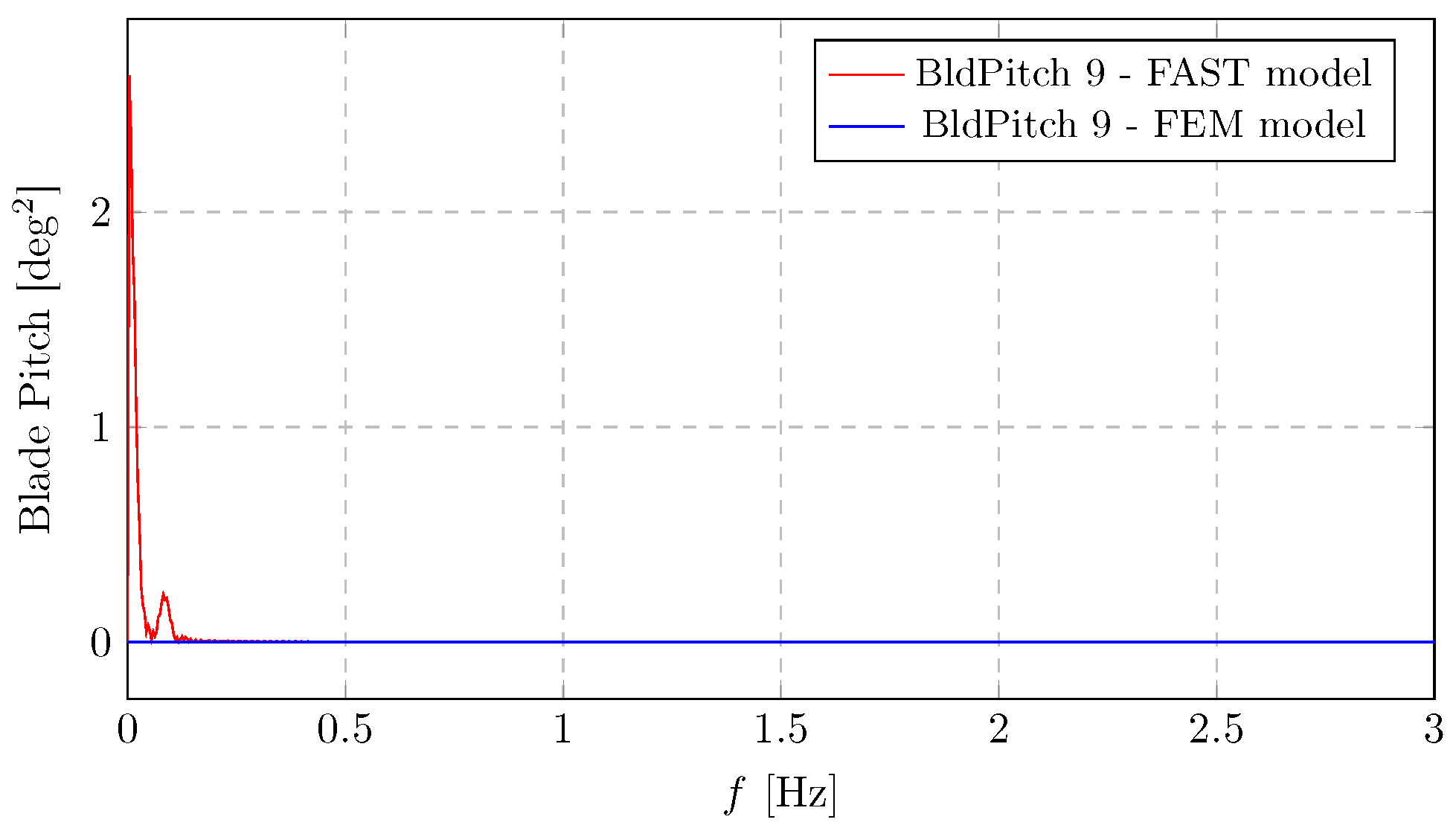

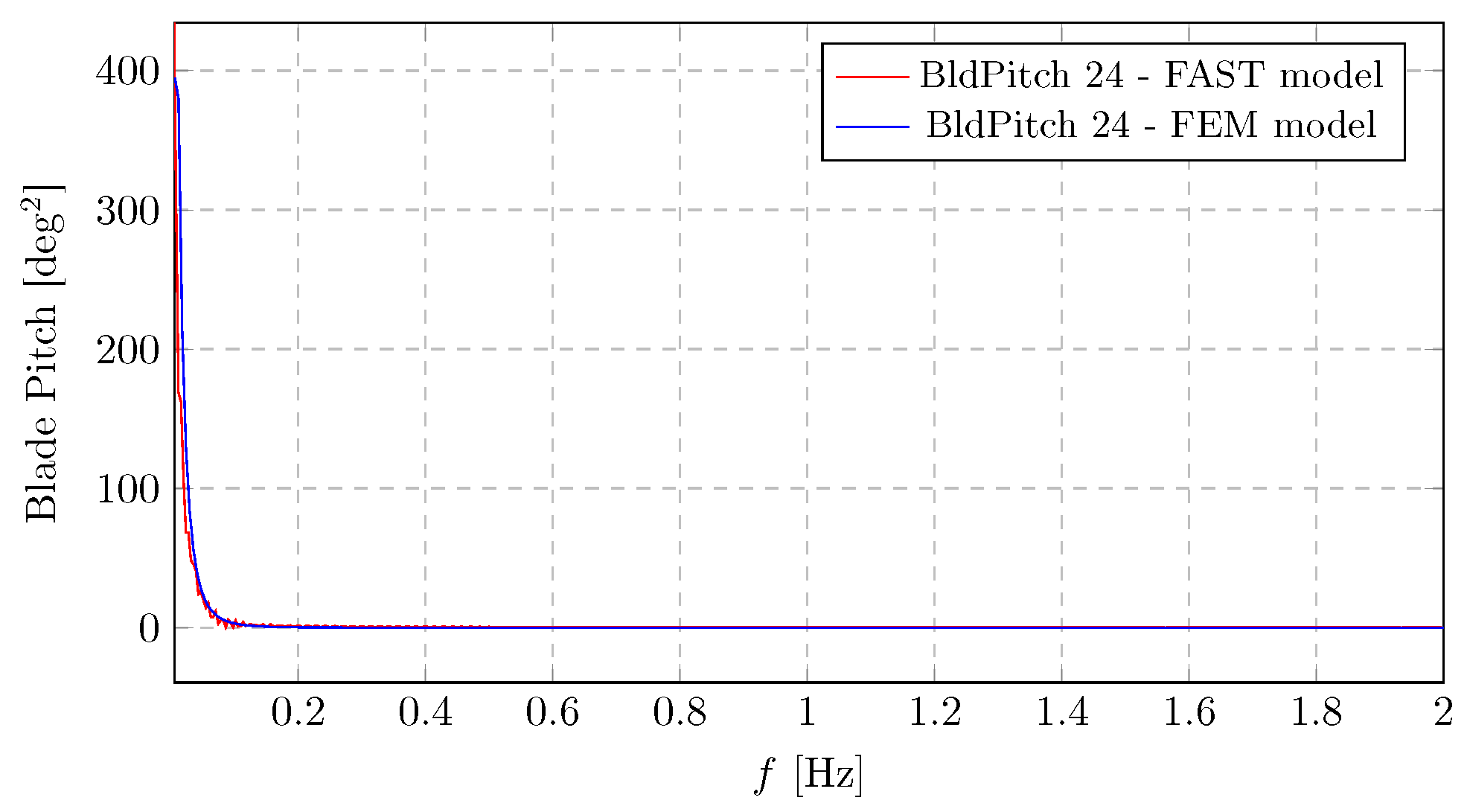

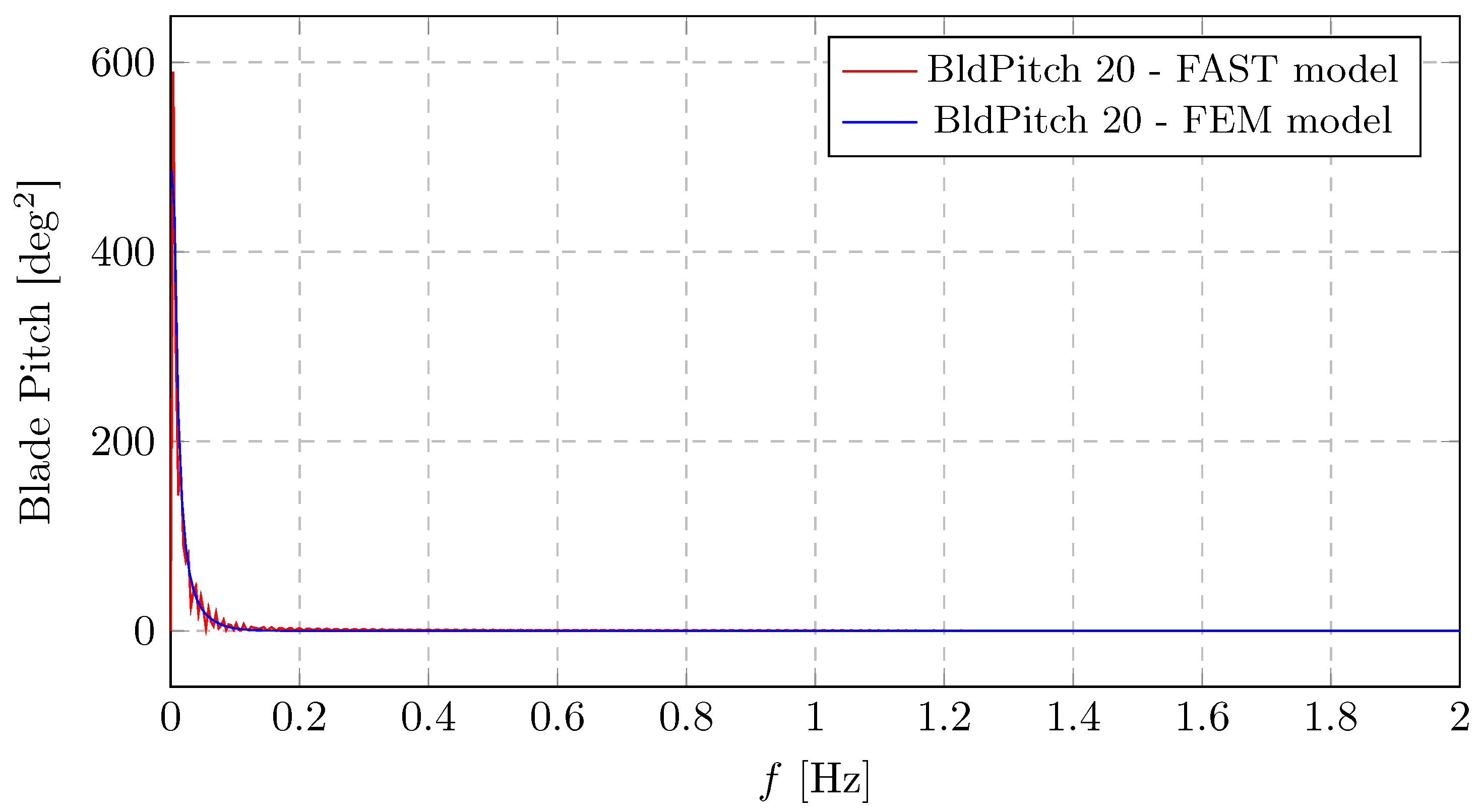

This section provides a focused comparative analysis of two key control-related parameters—the blade pitch frequency response (

Figure 13) and generator torque spectrum (

Figure 14)—to assess the consistency between the proposed finite-element method (FEM) model and the established FAST simulation results. The blade pitch frequency spectrum reveals a dominant magnitude at very low frequencies, with spectral energy rapidly diminishing as frequency increases. This behaviour indicates that blade pitch activity is mainly governed by low-frequency dynamics, typically driven by the turbine’s collective pitch control system in response to large wind speed variations.

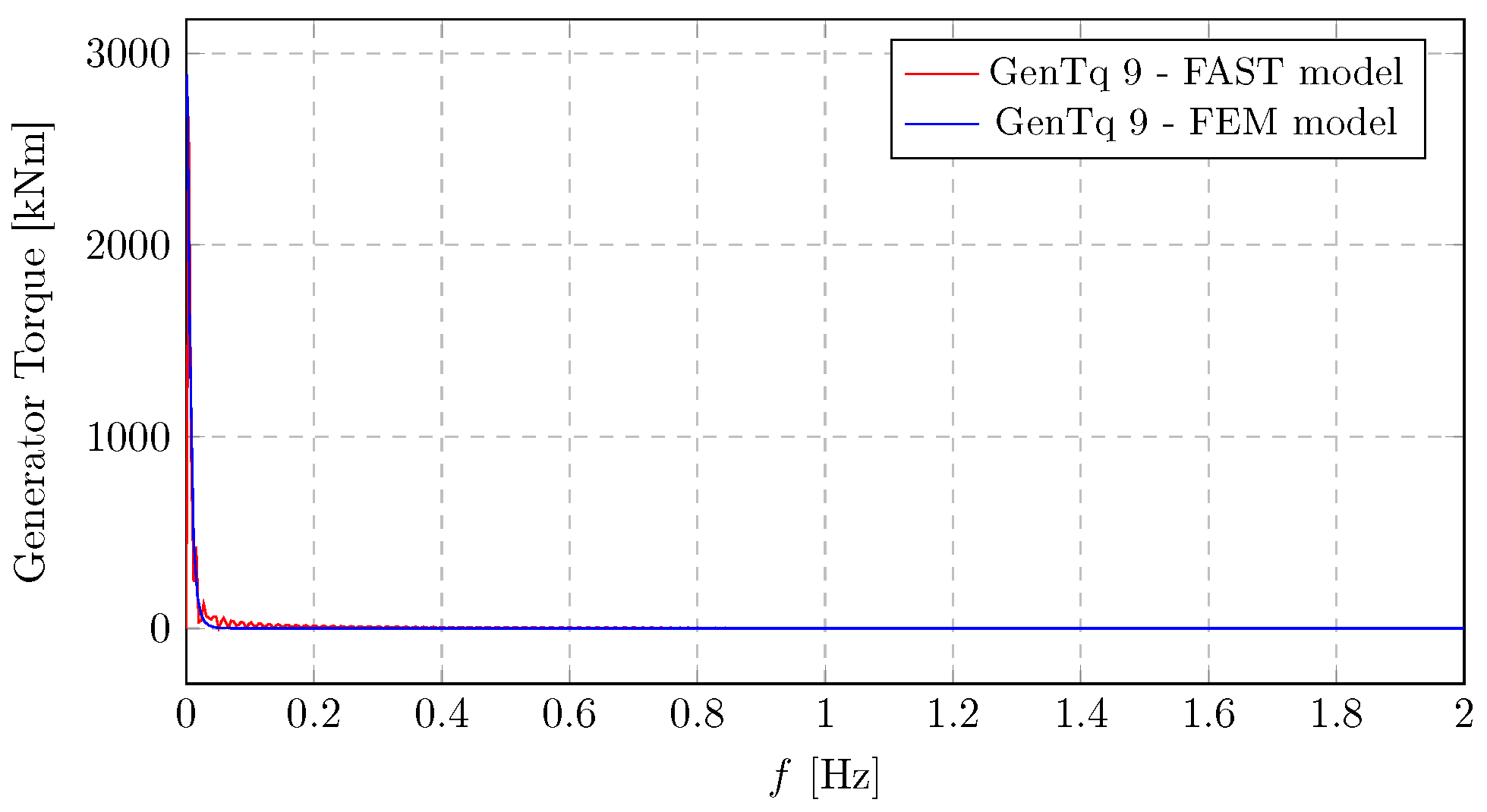

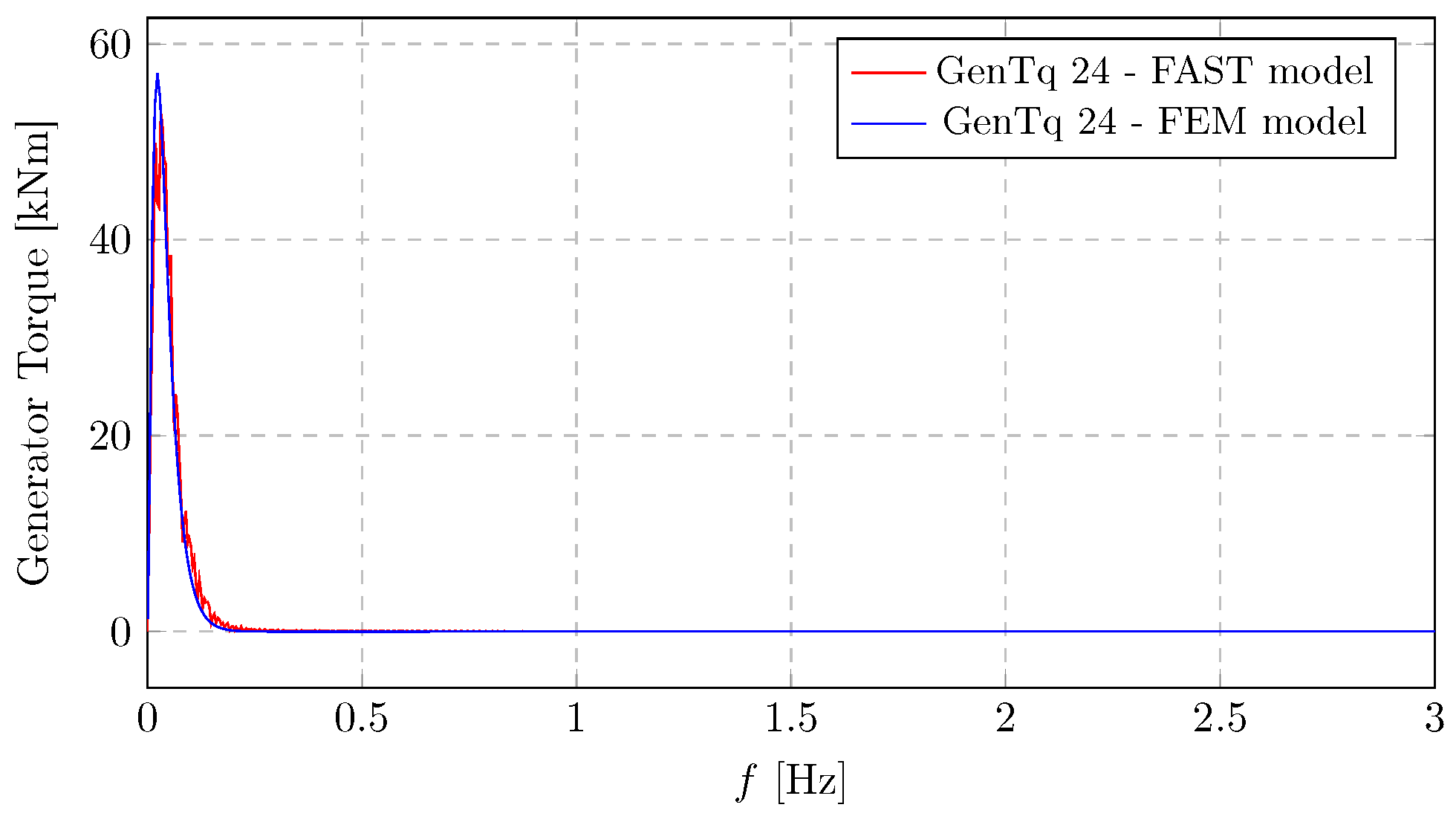

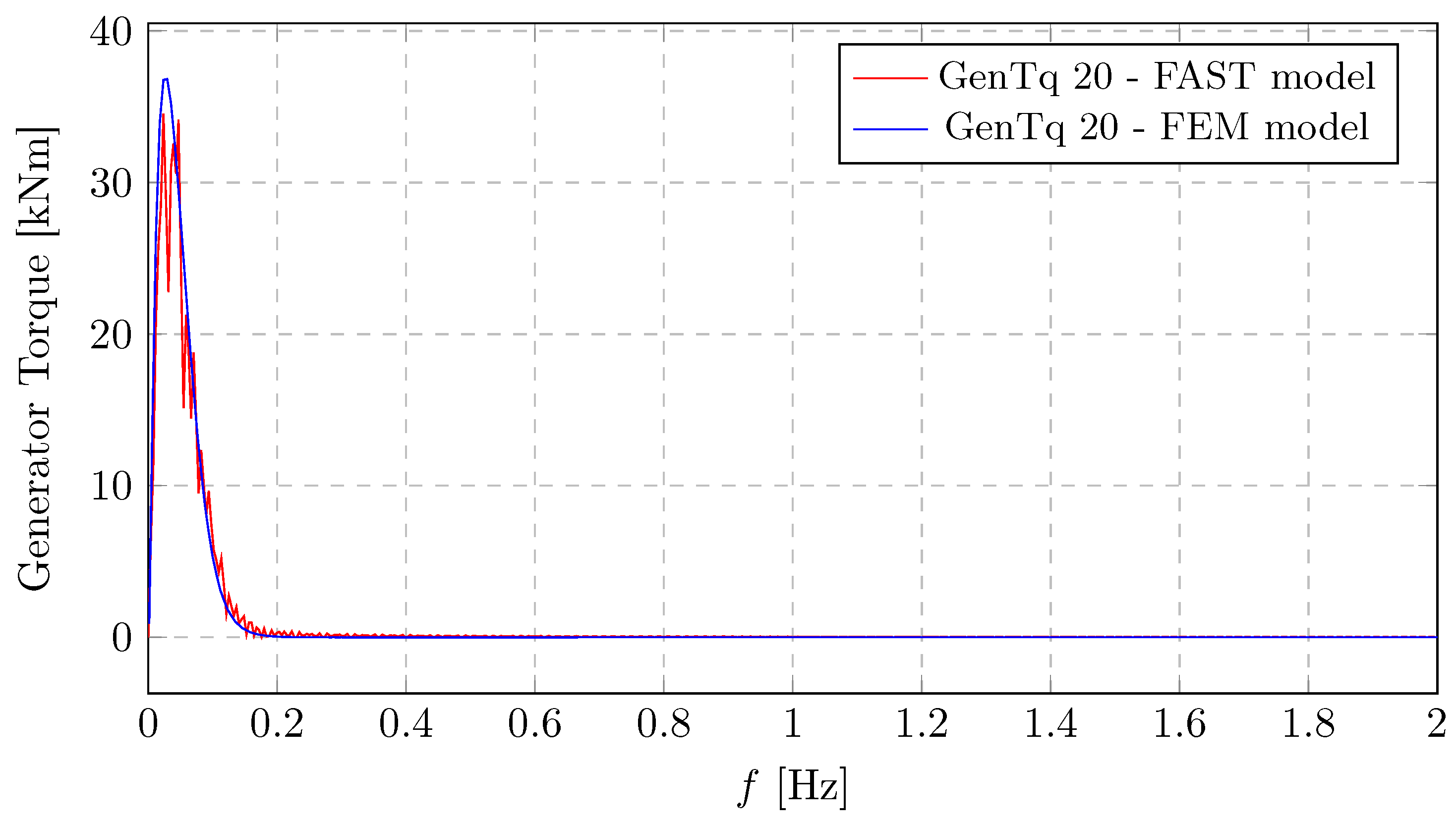

The generator torque spectrum presented in

Figure 14 also shows its highest PSD magnitude (reaching approximately 37

) at very low frequencies, reflecting the direct influence of wind variations. The agreement between the FEM and FAST models for the generator torque spectrum demonstrates that the proposed approach is equally capable of capturing the complex dynamic interactions (drivetrain dynamics, control system response) that govern generator torque, with their curves being nearly the same across the entire frequency range.

In accordance with the NREL convention, blade deflections and internal moments are expressed in a blade-fixed coordinate system defined by the flapwise and edgewise axes at the blade tip [

4]. This coordinate system is oriented relative to the local blade chord, providing a consistent reference for describing structural properties and load components along the blade span.

The flapwise axis corresponds to the direction in which the blade bends backwards or forwards relative to the rotor plane, primarily under the influence of aerodynamic lift. The edgewise axis corresponds to bending along the chord direction, i.e., toward or away from the leading or trailing edge, and is mainly associated with gravitational and inertial loading. Within this framework, all structural quantities are then consequently defined with respect to these flap-wise and edge-wise axes.

It should be noted that, whereas the FAST results are expressed in an axis system that pitches with the blade, the frequency-domain model results are referred to a similar coordinate system but it is fixed at the mean blade tip pitch angle. This distinction affects the comparison of results at low frequencies, where the blade undergoes significant pitching motion, leading to small discrepancies between the two representations.

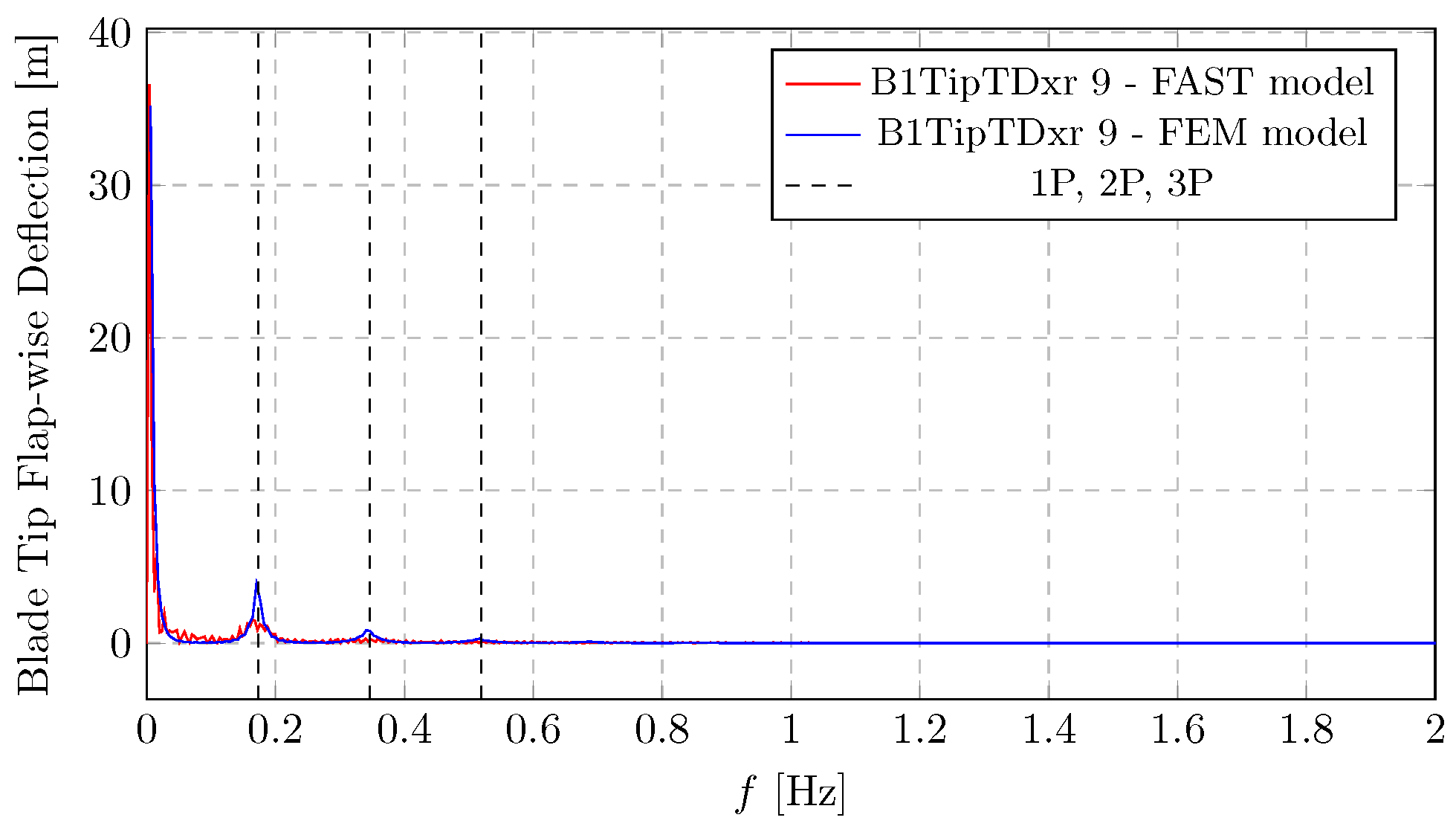

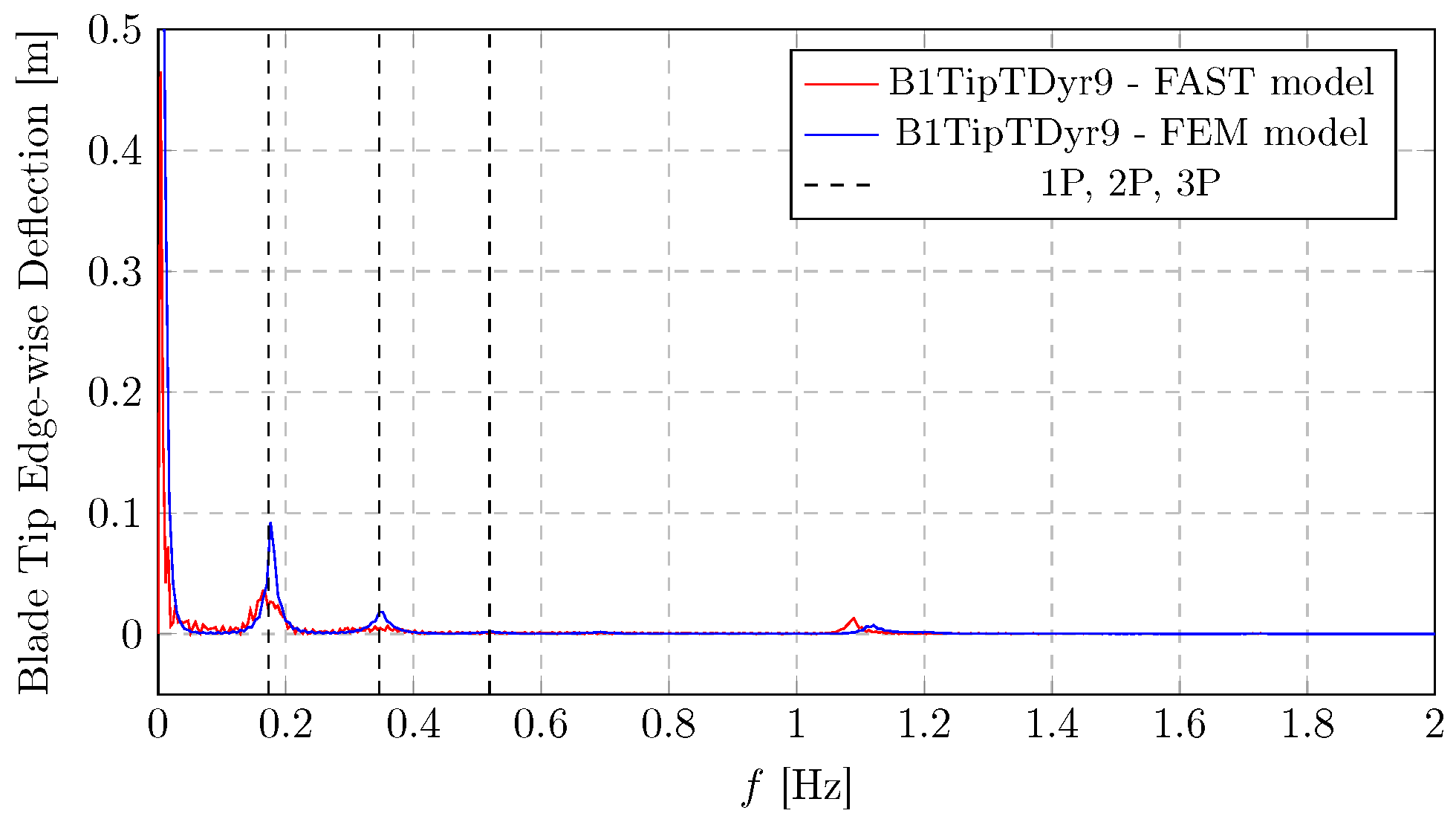

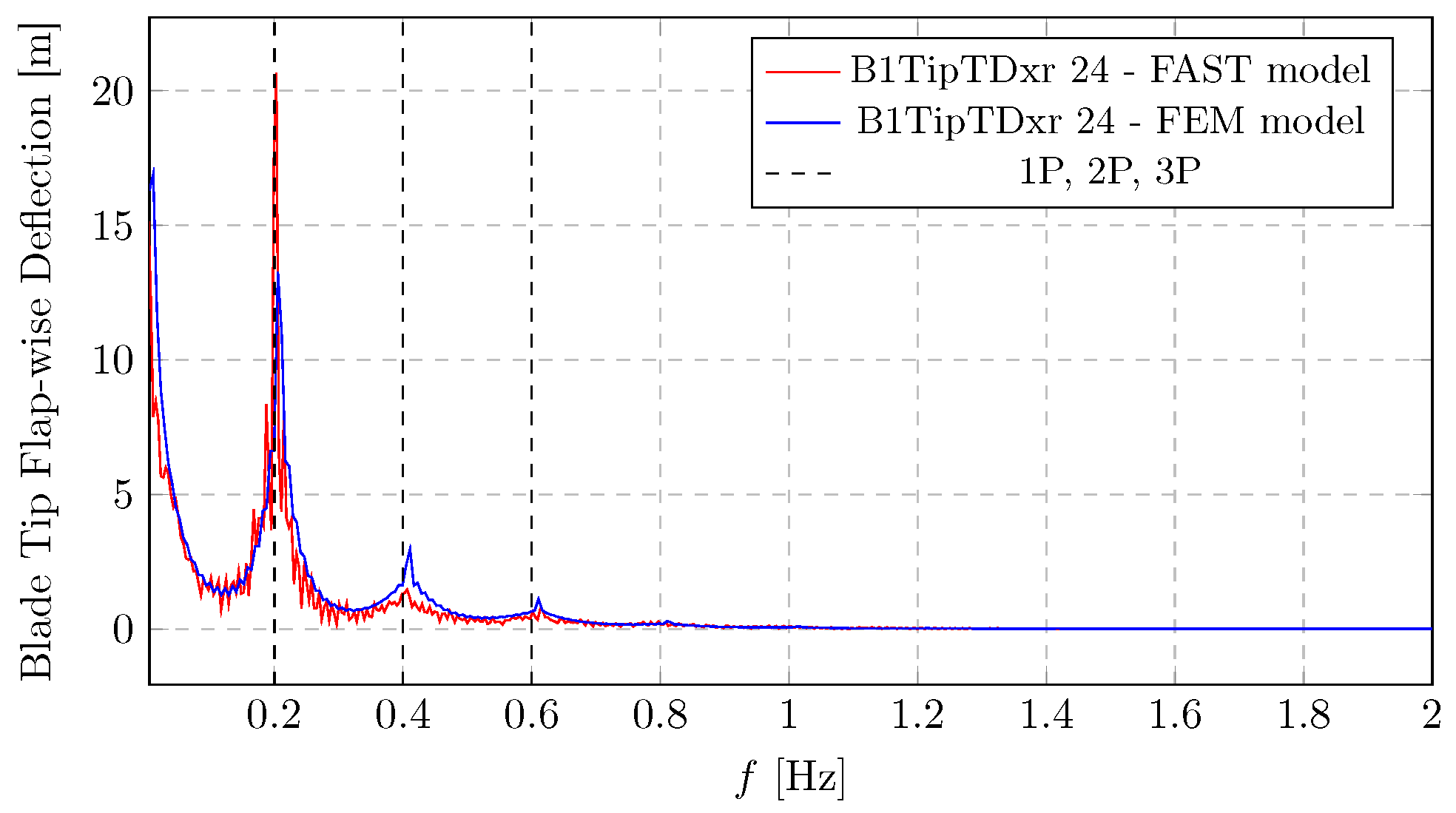

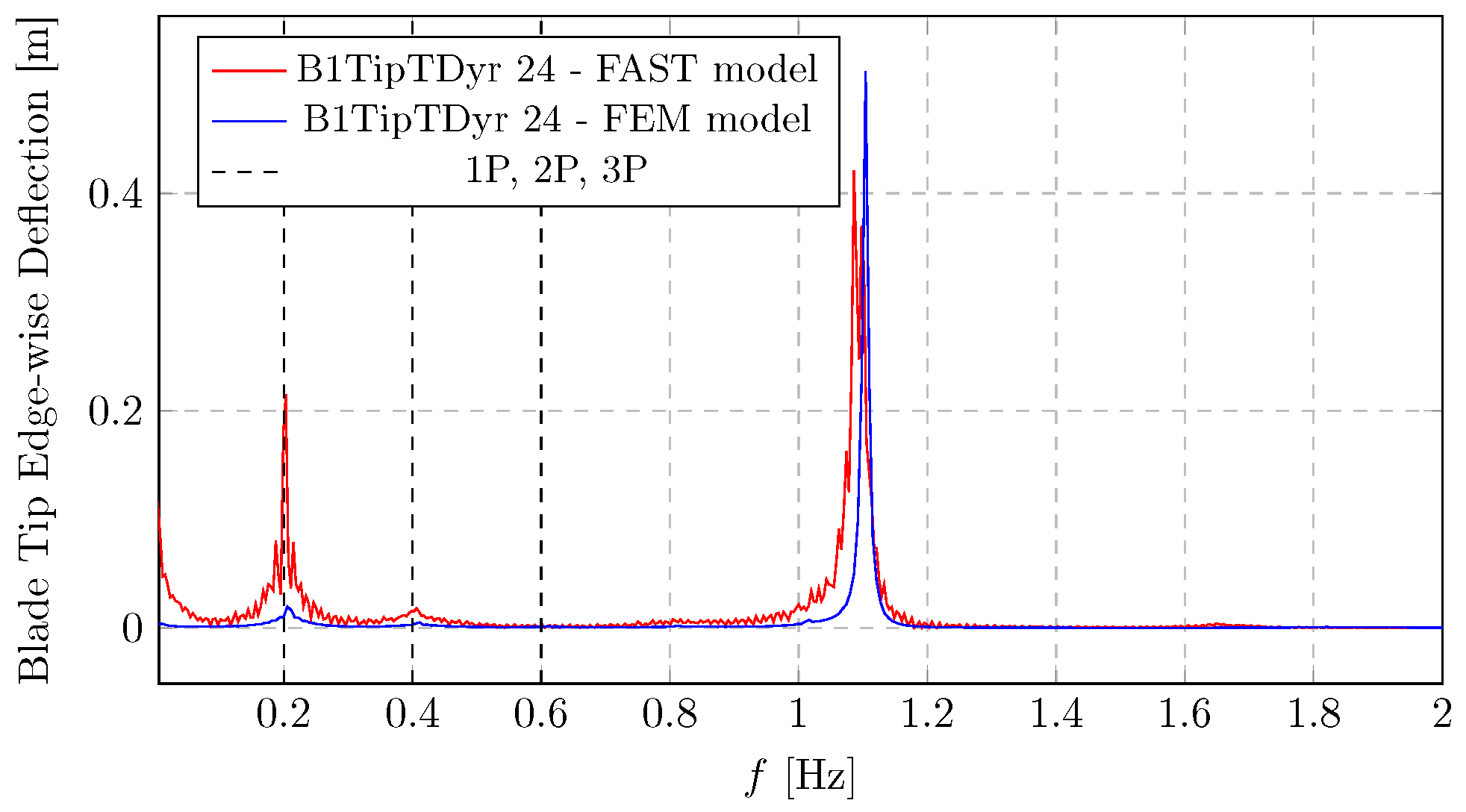

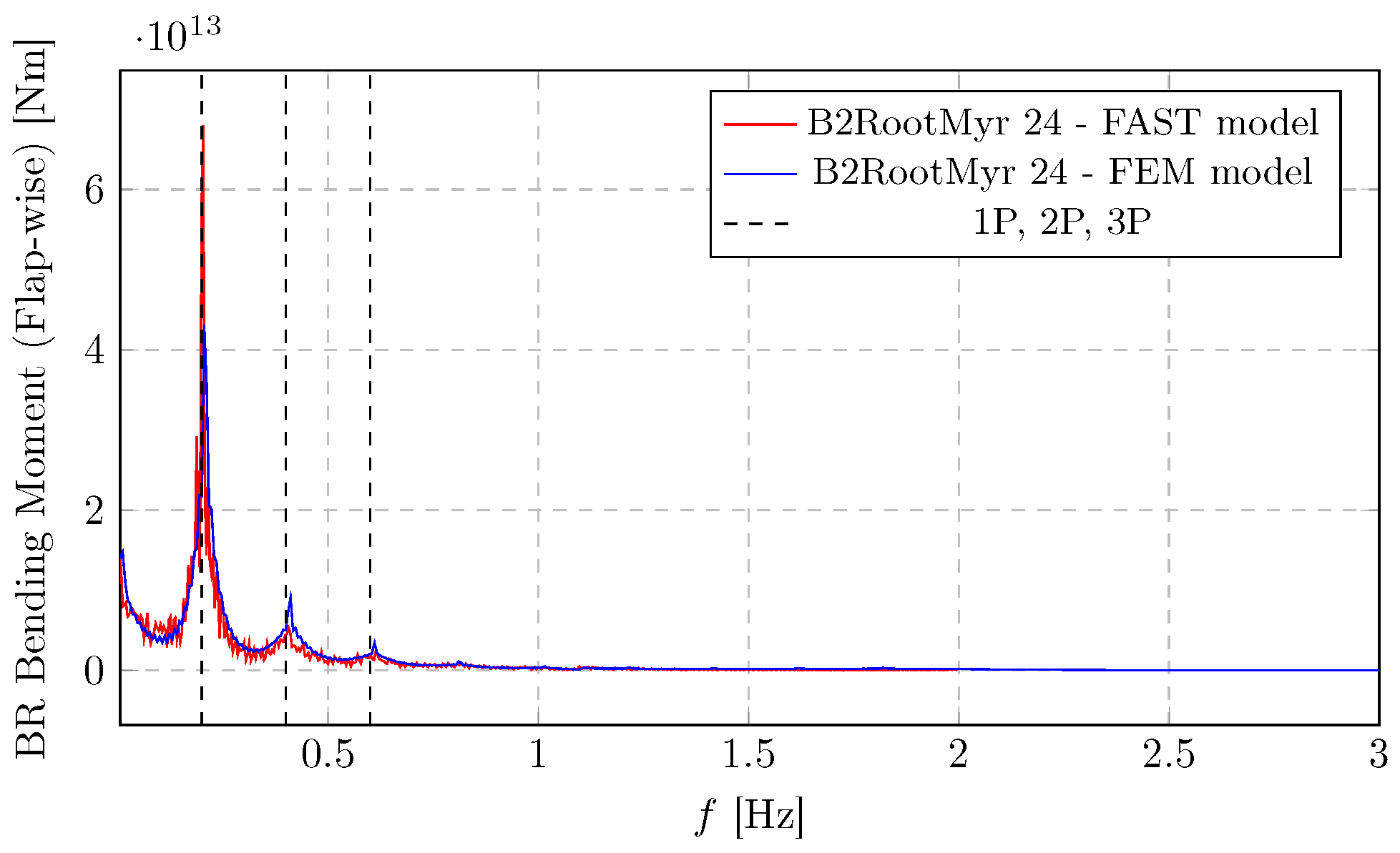

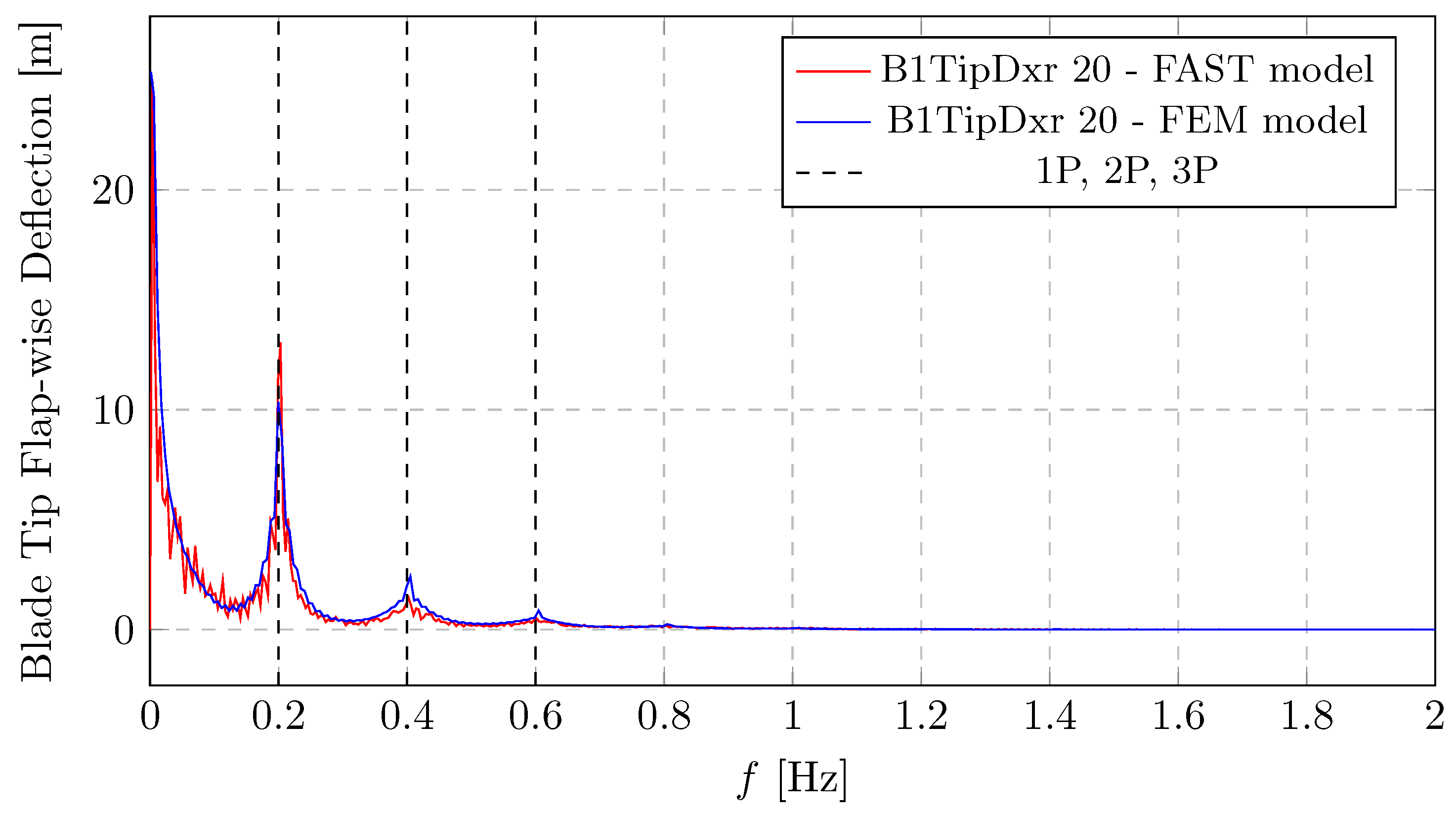

A similar dynamic behaviour can be observed in

Figure 15 and

Figure 16, which present the spectra of blade tip deflections. A spectral peak appears at the fundamental rotor frequency (1P), with additional energy at higher harmonics (2P, 3P) and a distinct peak around 0.7–0.8

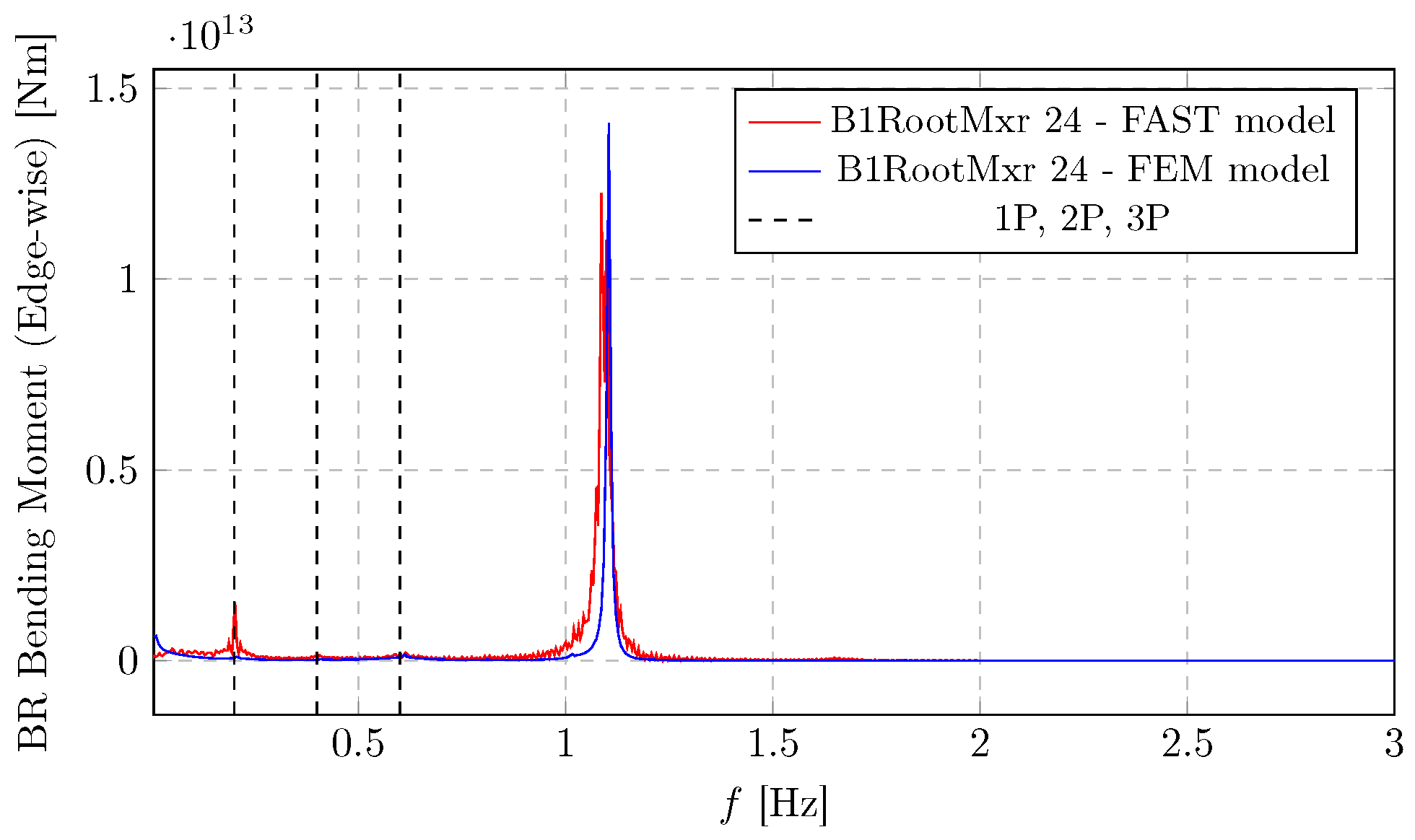

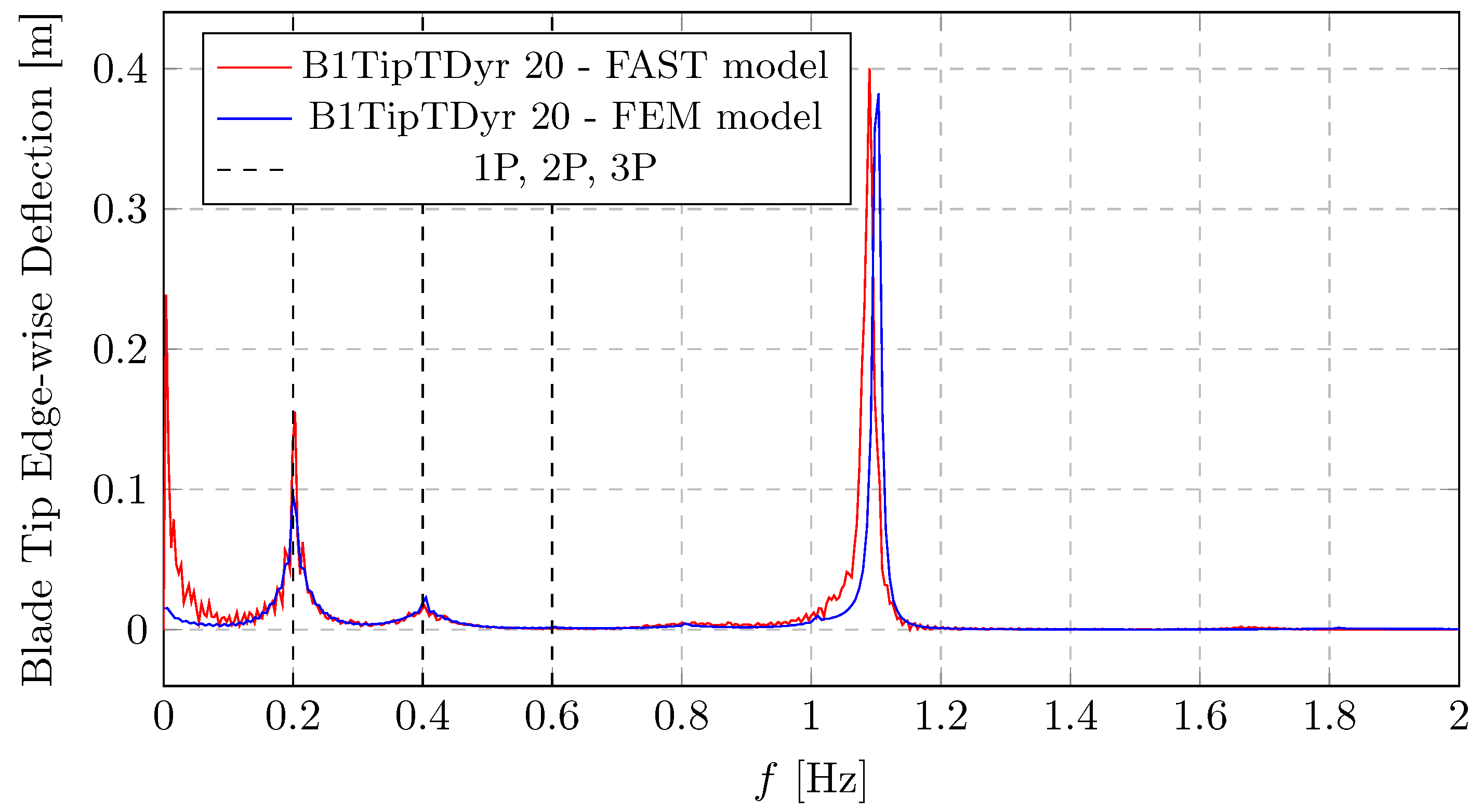

. The amplitude of the flap deflections highlights the high flexibility of the turbine blades. The edgewise deflection spectrum (

Figure 17) reveals a different dynamic behaviour. While the 1P peak remains visible, the dominant spectral component occurs near 1.1 Hz, which corresponds to the blade’s edgewise bending response, also seen in

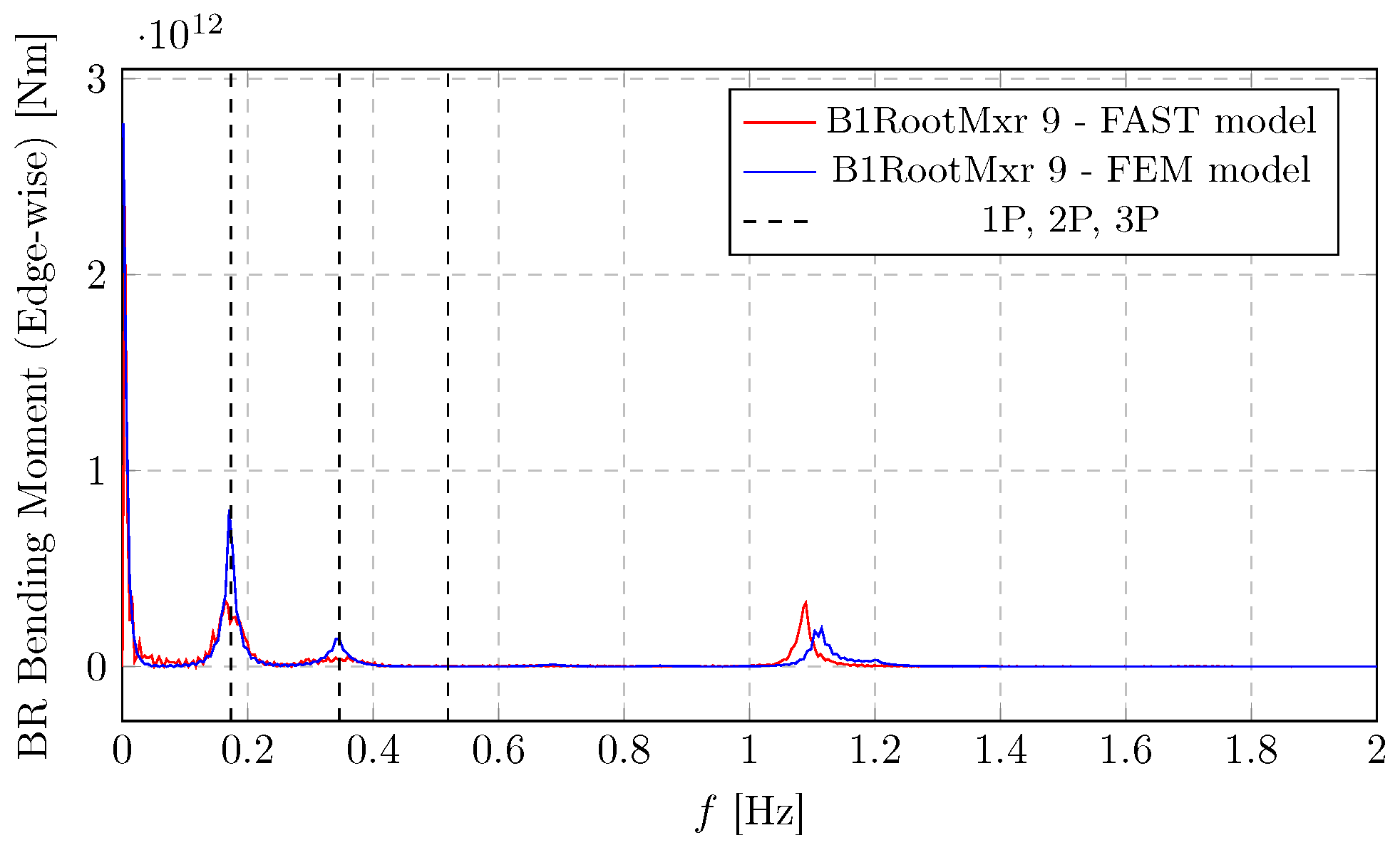

Figure 18. Due to the higher stiffness in the edgewise direction, deflections are significantly smaller than flapwise ones. Notably, results from both the OpenFAST simulations and the authors’ finite-element model exhibit excellent agreement across the entire frequency range, reinforcing the validity of the proposed modelling approach.

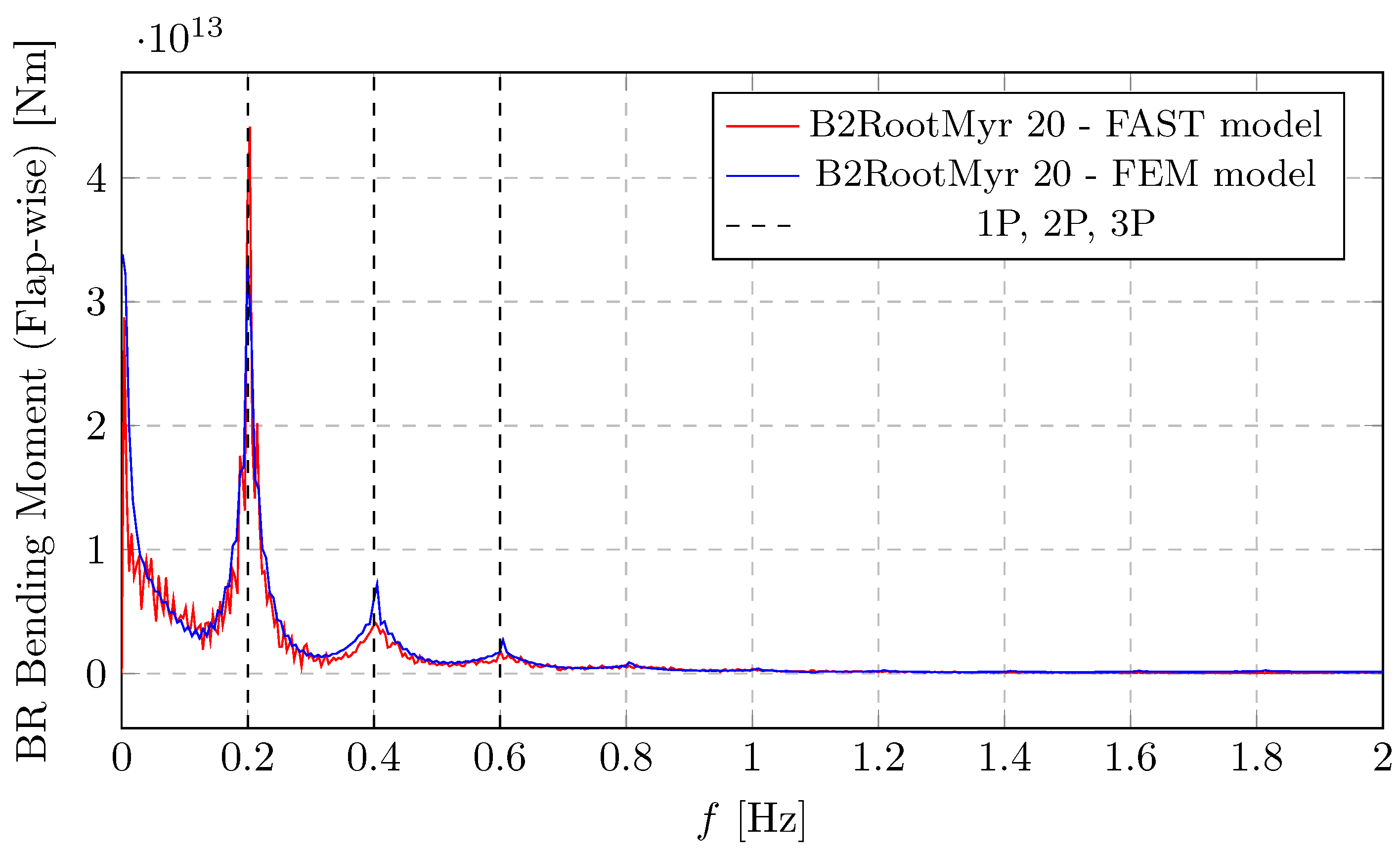

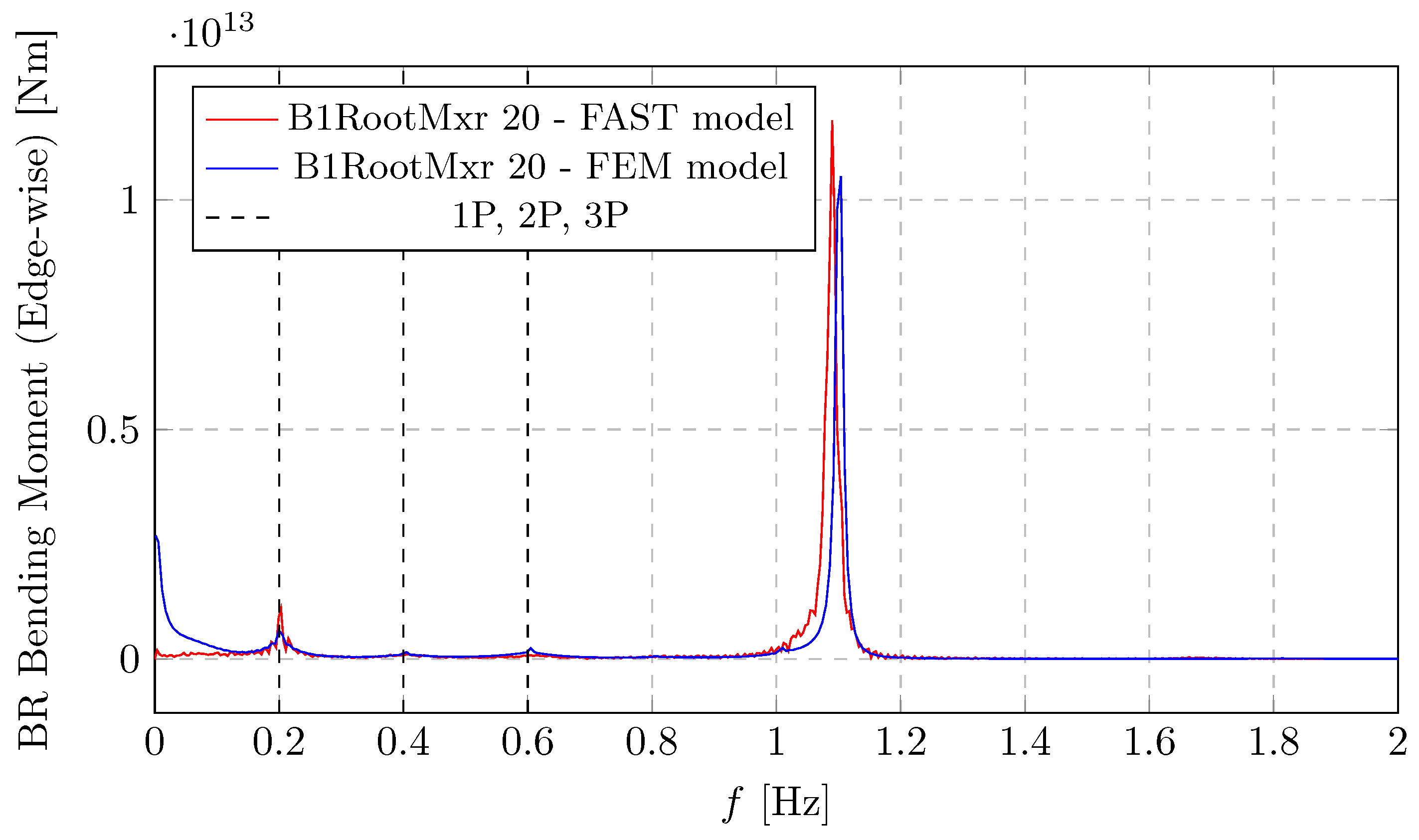

Figure 17 and

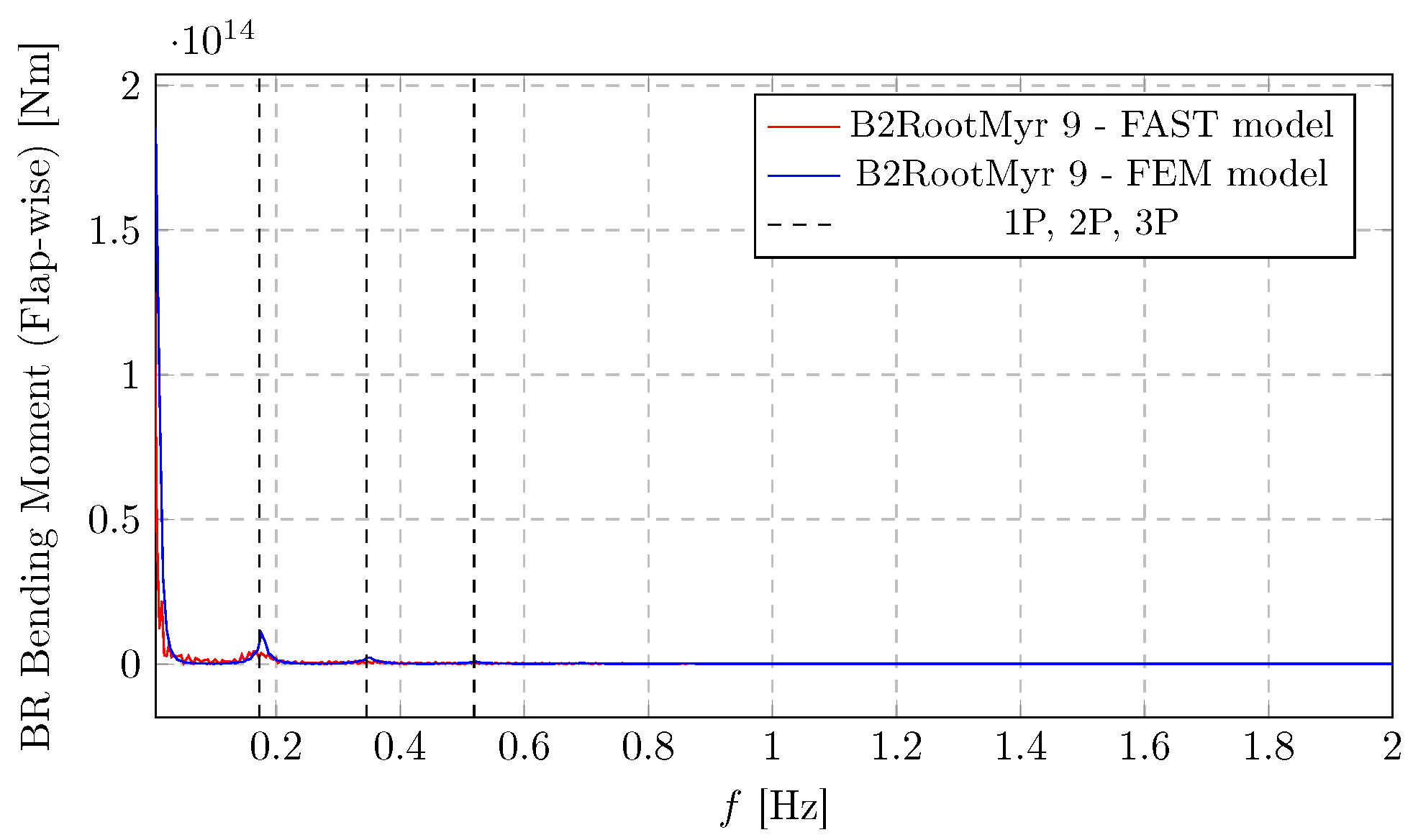

Figure 18 present a comparison between blade root bending moments in two geometrical planes. The FAST model (red) and the FEM model (blue) show a good agreement, especially in identifying the dominant frequencies and the overall shape of the frequency response. In

Figure 17, a significant peak (around

Nm) is observed at 1P frequency (0.2 Hz). This indicates a substantial response at the rotor’s rotational speed, possibly due to thrust variations or blade flapping. Smaller peaks are also seen near the 2P and 3P harmonics that are evident as an excitation source. These are caused by the rotational sampling of the eddies.

Figure 18 shows similar dynamic behaviour, revealing a significant peak at 1P, suggesting a strong edgewise bending response at the rotor’s rotational excitation. An evident peak is visible around 1.1 Hz. This is likely a structural natural frequency (possibly a blade edgewise mode) that is excited. It can be seen that the flapwise bending moments are significantly larger in magnitude compared to the edgewise moments, which is typical for wind turbine blades, as they primarily flap due to aerodynamic forces.

6.3. Summary of Results and Discussion

Results of the two methods used to model aero-servo dynamics of the considered rotor–nacelle model are summarised in

Table 3. Standard deviations of the selected model’s structural elements are compared against results from OpenFAST simulations. Statistic measure of the realisations are shown for some selected turbine’s structural elements and its parameters for wind (

U), pitch (

), hub angular velocity (

), generator torsion (

), blade tip flap-wise and edge-wise deflections (

) as well as blade flap-wise and edge-wise bending moments (

). In

Table 4, some parameters of total response and angle to global

x direction and their comparison were summarised.

The comparative analysis presented in

Table 3 and

Table 4 demonstrates a close correspondence between METHOD and FAST model predictions for both operational and structural response parameters. The mean wind velocity (

U) and pitch angle (

) exhibit differences below 3%, confirming that the aerodynamic loading conditions are consistently reproduced in both numerical environments. Likewise, the hub angular velocity (

) and generator torsion (

) vary by approximately 10%, which may be attributed to the simplified drivetrain dynamics and lumped-mass representation adopted.

For the structural response, METHOD predicts slightly higher amplitudes of blade flapwise deflection and the corresponding bending moment by approximately 10–15% compared with FAST. This behaviour indicates that the FEM model captures a more compliant global response of the blade, reflecting the higher fidelity of its finite-element discretisation and the inclusion of distributed structural properties. The edgewise components remain in close agreement between the two models, indicating that both approaches consistently reproduce the overall deformation characteristics.

Resultant quantities follow a similar trend. The total blade root moment magnitude () obtained from the FEM model exceeds that from FAST by about 8%, while the resultant tip deflection () differs by roughly 12%. Despite these magnitude differences, the resultant directional angles remain closely aligned, with deviations within , confirming a coherent representation of the global response orientation. These differences arise mainly from the distinct reference frames, with FAST reporting quantities in a blade-fixed axis system that pitches with the blade, whereas FEM uses a system fixed at the mean blade-tip pitch. This distinction affects the representation of low-frequency components and contributes to the minor discrepancies observed in the resultant amplitudes. A systematic difference remains at very low frequencies. This discrepancy occurs in the band where blade pitch motion is largest and is consistent with the different axis conventions used. Although the pitching axis system has not yet been implemented in METHOD, the order of magnitude of the difference is consistent with the expected effect of transforming between these two coordinate systems.

The main differences between the FEM and OpenFAST results, and their implications for the interpretation of the benchmark, can be summarised as follows:

Overall, the comparison demonstrates that the proposed FEM-based model reproduces the dynamic behaviour predicted by FAST with satisfactory accuracy, while considerably reducing the computational time and improving numerical efficiency. Hence, METHOD framework can be considered a reliable and physically transparent alternative to FAST for detailed analyses of wind turbine dynamics.

6.4. Computational Efficiency and Performance Comparison

The computational efficiency represents one of the main advantages of METHOD software compared to the reference model. Only one METHOD analysis is required for any wind and wave condition, whereas time-domain analysis programs such as OpenFAST need long or multiple shorter analyses with different random ‘seeds’, which result in different gust time histories. Haid et al. [

53] found that about 1 min of simulation was required in order for starting transients to decay and that then the average of the extreme value in each of 10 10-min records predicted the average of the extreme value in each of 36 10-min records to within 3.5% at 95% confidence. BS EN IEC 61400-1:2019 [

42], Section 7.6.2.2, requires 15 10-min (excluding starting transient decay time) simulations to be performed and the maximum responses averaged. This would amount to approximately 2.75 h of simulation if each 10-min record was analysed separately or 2.5 h if one longer analysis was performed and then the split into 10-min segments in order to average 15 10-min maxima.

A comparison of simulation times in

Table 5 indicates that METHOD provides a substantial improvement in performance across all stages of the analysis, reducing preprocessing time from several minutes to a few seconds.

By linearly interpolating the values reported in

Table 5 to a simulation duration of 2.5 h, the total OpenFAST computational time is estimated as 3123 s, whereas the corresponding METHOD computational time is 57.4 s. The resulting ratio, 3123/57.4 ≈ 54.4, indicates that, for the analyses considered here, the METHOD frequency-domain model runs approximately 54 times faster than the OpenFAST time-domain simulations.

These results highlight that METHOD provides a major reduction in total simulation time without noticeably compromising model fidelity, physical consistency, or the standard deviation of the calculated responses. This improvement makes it particularly well-suited for parametric or fatigue-life studies, where numerous long-term realisations are required. Further METHOD performance gains could be achieved through the parallelization of wind-field generation and the solver-level optimization of the coupled aeroelastic routines.

7. Conclusions

A frequency-domain finite-element framework (METHOD), implemented in Python, has been benchmarked in a rotor–nacelle configuration against the industry-standard NREL OpenFAST time-domain tool. Although METHOD provides a full-turbine representation (including tower and substructure), this study deliberately focused on the rotor–nacelle extract to validate the modelling stage that dominates aerodynamic excitation and drive-train loading. The rotor–nacelle model employs 372 degrees of freedom (18 nodes per blade and 8 nacelle/shaft nodes), providing sufficient resolution to capture the dominant flapwise, edgewise, and torsional modes while keeping the frequency-domain inversions computationally tractable. Validation focused on key dynamic quantities, including blade tip deflections, blade root moments, rotor speed, generator torque, and blade pitch, using both statistical descriptors (standard deviations) and spectral measures (power spectral densities, PSDs).

At above-rated wind speeds, standard deviations and PSDs for blade tip deflections, root moments, rotor speed, generator torque, and blade pitch generally agree within ∼1–3% for wind and pitch channels, 8–10% for hub-speed and torque, and 2–13% for structural responses, while resultant displacements differ by approximately 8–12% with directional angles, within about

. Below rated (

Appendix A cases), discrepancies are markedly smaller, reflecting the absence of strong nonlinearities from actuator saturation and large pitch excursions. The spectra consistently retain the dominant rotor harmonics (1P, 2P, 3P) and natural frequencies. Residual differences can be traced to linearised aerodynamics and damping at mid-/high frequencies, and to neglected pitch-rate and torque limits plus reference-frame conventions (mean-pitch-fixed FEM versus blade-fixed OpenFAST) at low frequencies. Within these bounds (typically <10% for key PSD peaks and <12% for response variances at above-rated), the frequency-domain model reproduces OpenFAST behaviour with a fidelity that is adequate for early-stage design, controller tuning, and fatigue/sensitivity studies.

The study nonetheless has several limitations. The analysis is based on linearised aeroelastic dynamics about selected operating points, with a simplified treatment of aerodynamics (quasi-steady BEM gains), structural damping (Rayleigh/modal models), and control (no explicit pitch-rate limits or torque ceiling). Future work will incorporate explicit controller saturation effects, refined aero/damping linearisation and coupling toward full aero-hydro-servo-elastic representations, with the aims of tightening above-rated accuracy, extending the validation to the complete turbine system, and exploiting METHOD’s full-turbine capabilities in an integrated frequency-domain design framework.

From a practical standpoint, METHOD offers a transparent, modular, and computationally efficient alternative to fully nonlinear time-domain simulations. Leveraging numerical backends, it enables orders-of-magnitude reductions in runtime and memory demand compared with long OpenFAST campaigns, making large parametric sweeps, controller-tuning studies, and fatigue-life screening feasible within typical design timelines. Because the underlying formulation is based on full-turbine FEM, the framework can accommodate extensions such as flexible towers, substructures, and additional degrees of freedom, while retaining the same frequency-domain solution strategy. The present rotor–nacelle benchmark shows that, even for this most dynamically active subsystem, principal response errors can be maintained in the ∼5–12% range above rated (and even lower below rated), while substantially shortening design cycles and reducing computational cost, allowing large parametric sweeps, controller-tuning loops, and fatigue-life screening to be carried out within hours rather than days.