Energy Transformation Towards Climate Neutrality by 2050: The Case of Poland Based on CO2 Emission Reduction in the Public Power Generation Sector

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

- The PSE Forecast, which includes information on the decommissioning of generation units agreed with the Transmission System Operator [28];

- Poland’s Energy Policy until 2040 [29], which presents projections of energy demand and coal consumption for power generation purposes—available in Annex No. 2 to the document under the “PEP Forecast” scenario;

- The National Energy and Climate Plan [30] in which coal demand projections have been published.

3. Methods

- current strategies of Energy Groups (2024/2025);

- annual reports of Energy Groups published in Q1 2025;

- information on long-term capacity market contracts that have been concluded, including CO2 emission constraints/limits that contracted coal units must meet from 2026 onwards (in line with Regulation (EU) 2019/943 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 5 June 2019 on the internal market for electricity);

- authors’ own assumptions.

- REFERENCE (REF) scenario—the average 2023 CF (adjusted for 2024) is held constant throughout the forecast period from 2025 to 2050,

- LOWER-CF scenario—CF is reduced by 5 percentage points relative to the reference level by 2030 (linear decline), and is then held constant until 2050,

- HIGHER-CF scenario—CF is increased by 5 percentage points relative to the reference level by 2030 (linear rise), and then is held constant until 2050.

4. Result and Discussion

4.1. Decommissioning of Hard Coal- and Lignite-Fired Power Generation Units

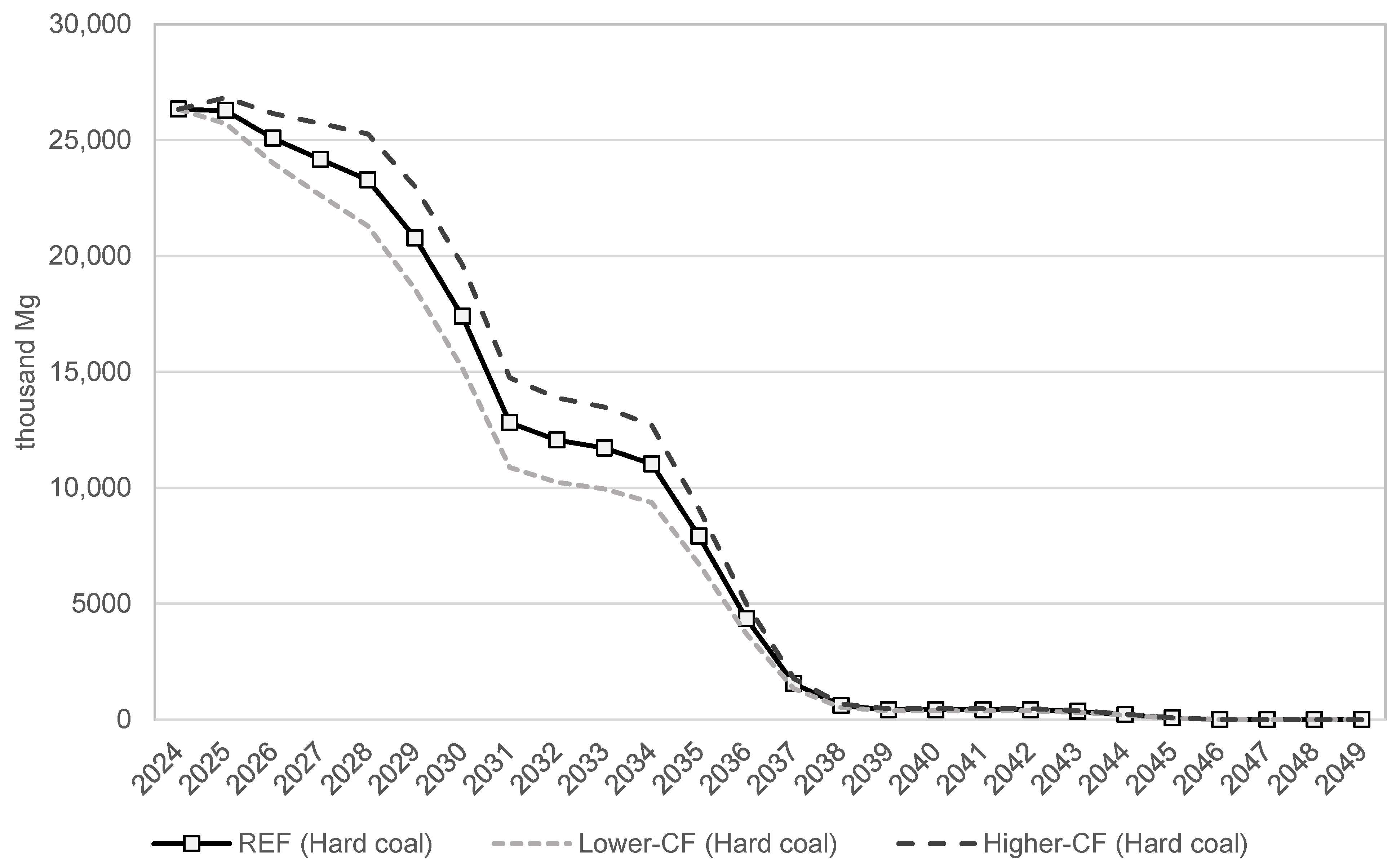

4.2. Forecast of Fuel Consumption for Energy and Heat Production

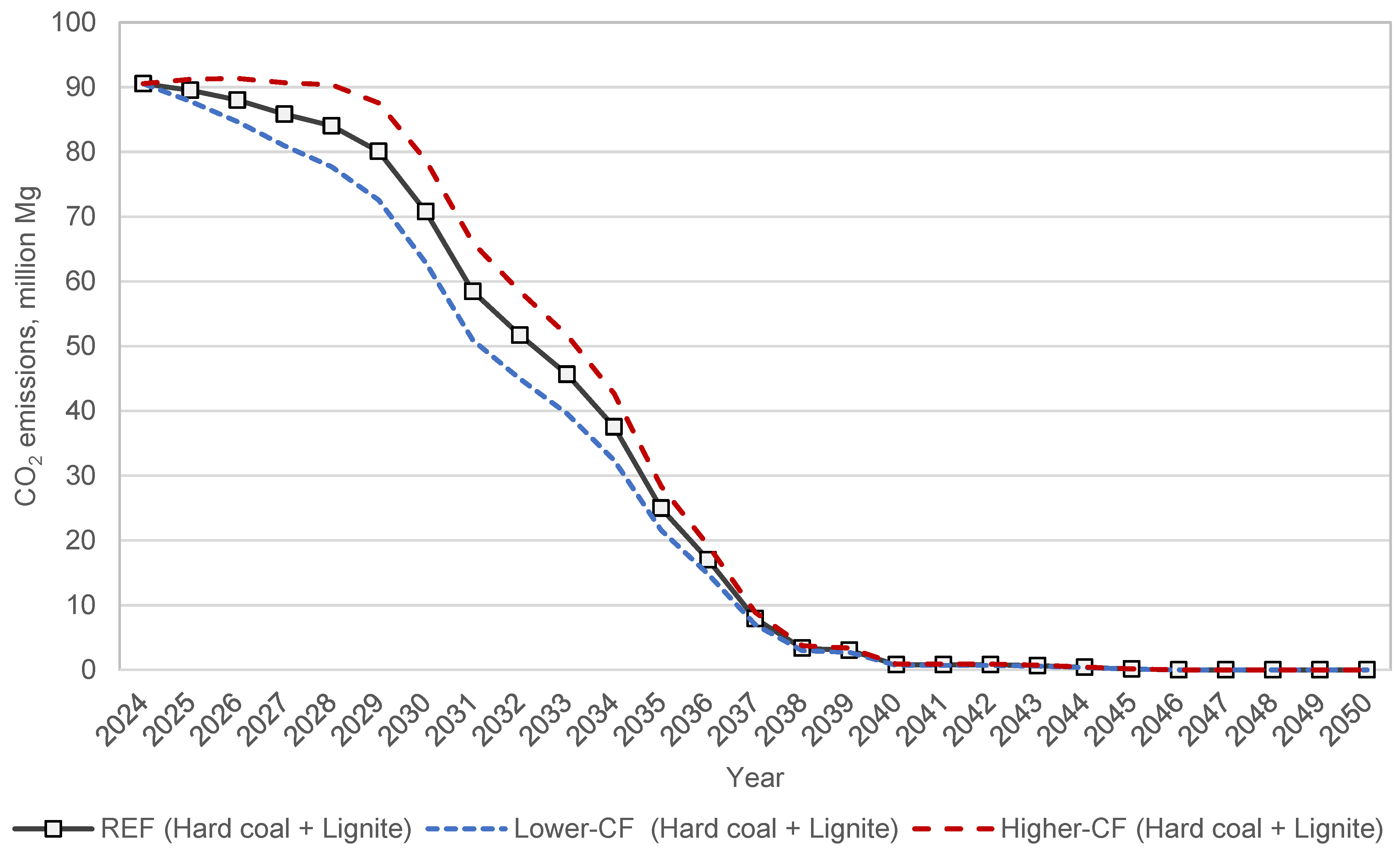

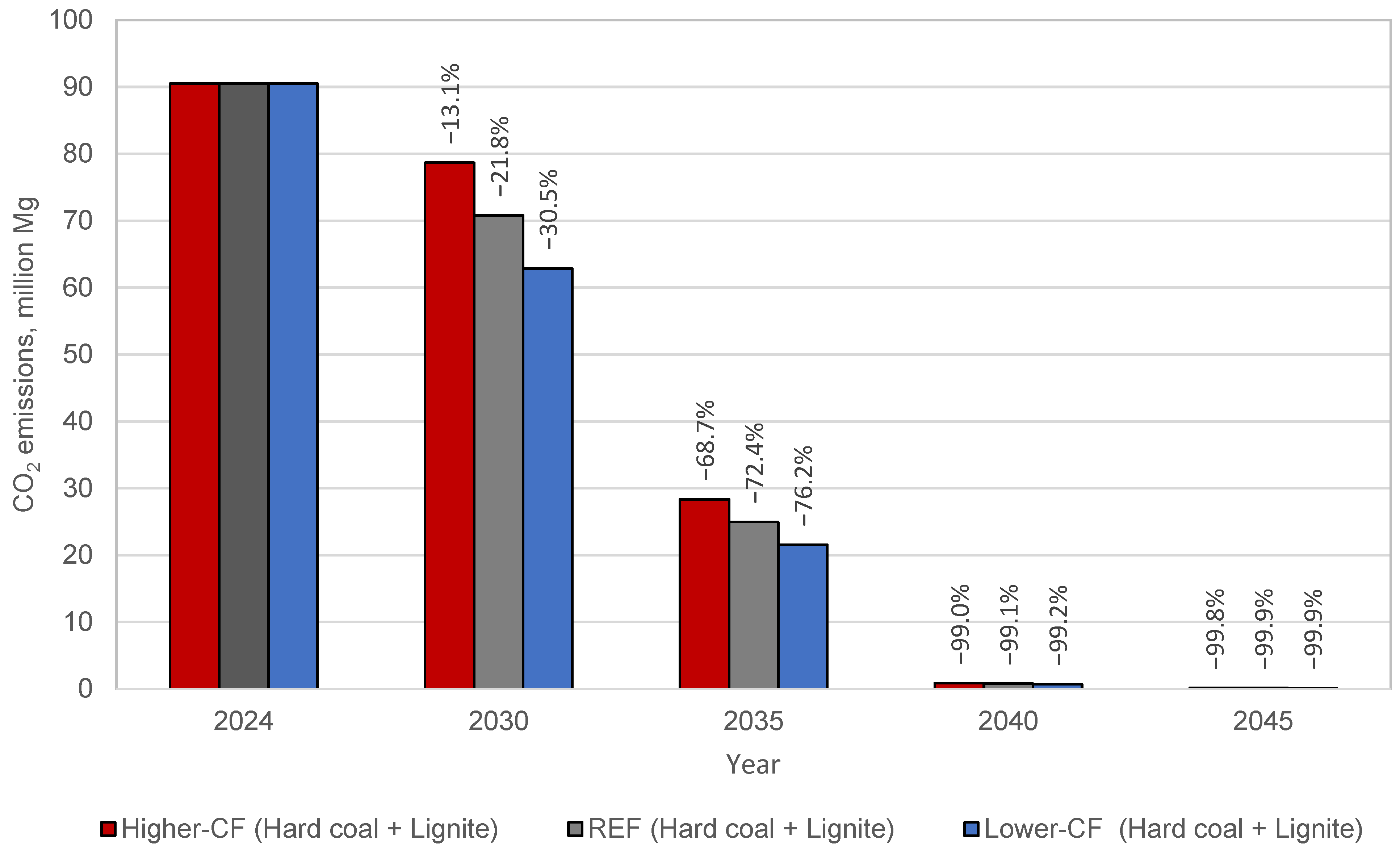

4.3. Reduction in CO2 Emissions

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- EMBER. EU Fossil Generation Below 25% for the First Month Ever. 2024. Available online: https://ember-energy.org/latest-insights/eu-fossil-generation-below-25-for-the-first-month-ever/ (accessed on 17 November 2025).

- Polish Electricity Statistics. Polish Power Industry 2019, Annual Bulletin; Energy Market Agency: Warsaw, Poland, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Polish Electricity Statistics. Polish Power Industry 2023, Annual Bulletin; Energy Market Agency: Warsaw, Poland, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- TSO Report. Summary of Quantitative Data on the Operation of the Polish Energy System in 2024; Polskie Sieci Elektroenergetyczne (PSE): Warsaw, Poland, 2025; Available online: https://www.pse.pl/dane-systemowe/funkcjonowanie-kse/raporty-roczne-z-funkcjonowania-kse-za-rok/raporty-za-rok-2024 (accessed on 17 November 2025).

- EMITOR. Emissions of Environmental Pollutants in Public Power Plants and Combined Heat and Power Plants; Energy Market Agency: Warsaw, Poland, 2024; ISSN 1232-2537. [Google Scholar]

- Malec, M. The Prospects for Decarbonisation in the Context of Reported Resources and Energy Policy Goals: The Case of Poland. Energy Policy 2022, 161, 112763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agora Energiewende and Enervis. Phasing Out Coal in the Eu’s Power System by 2030, a Policy Action Plan. 2021. Available online: https://www.agora-energiewende.org/fileadmin/Projekte/2020/2020_09_EU_Coal_Exit_2030/A-EW_232_EU-Coal-Exit-2030_WEB.pdf (accessed on 17 November 2025).

- Paraschiv, L.S.; Paraschiv, S.; Alexandru, S. Decarbonizing Europe’s Energy System through the Phase-out of Coal-Fired Power Plants Under the Green Deal Initiatives for Sustainable Development. Manag. Environ. Qual. Int. J. 2025, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keles, D.; Yilmaz, H.Ü. Decarbonisation through Coal Phase-out in Germany and Europe—Impact on Emissions, Electricity Prices and Power Production. Energy Policy 2020, 141, 111472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IEA Energy Policy Review. Germany 2025 Report. 2025. Available online: https://www.iea.org/reports/germany-2025 (accessed on 17 November 2025).

- Ocelík, P.; Diviák, T.; Lehotský, L.; Svobodová, K.; Hendrychová, M. Facilitating the Czech Coal Phase-Out: What Drives Inter-Organizational Collaboration? Soc. Nat. Resour. 2022, 35, 705–724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IEA Energy Policy Review. Czech Republic 2021 Report. 2021. Available online: https://www.iea.org/reports/czech-republic-2021 (accessed on 17 November 2025).

- CEZ Group. Vision 2030. 2021. Available online: https://www.cez.cz/sustainability/en/vision-2030 (accessed on 17 November 2025).

- EP Holding. Our Energy Transistion. 2025. Available online: https://www.epholding.cz/en/our-energy-transition/ (accessed on 17 November 2025).

- Ministry of Industry and Trade of the Czech Republic. The National Energy and Climate Plan of the Czech Republic. 2024. Available online: https://mpo.gov.cz/en/energy/strategic-and-conceptual-documents/the-national-energy-and-climate-plan-of-the-czech-republic--285295/ (accessed on 17 November 2025). (In Czech)

- Tkach, D. The Czech Republic’s National Energy and Climate Plan: Pathways to decarbonization, energy, security, and industrial transformation. Econ. Financ. Manag. Rev. 2025, 3, 4–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brauers, H.; Oei, P.Y. The Political Economy of Coal in Poland: Drivers and Barriers for a Shift Away from Fossil Fuels. Energy Policy 2020, 144, 111621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pepłowska, M. Climate Neutrality in Poland: The Role of the Coal Sector in Achieving the 2050 Goal. Polityka Energ.—Energy Policy J. 2025, 28, 113–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kubiczek, P.; Smoleń, M. Three Challenging Decades Scenario for the Polish Energy Transition Out to 2050; Instrat: Warsaw, Poland, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Gutowski, A.; Maciejczak, M. Development of the Polish Power Sector Towards Energy Neutrality—The Scenario Approach. Energies 2024, 17, 2763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forum Energii. Poland: Climate Neutrality by 2050. Electrification and Sector Coupling. 2020. Available online: https://www.forum-energii.eu/en/poland-climate-neutrality-by-2050-electrification-and-sector-coupling (accessed on 17 November 2025). (In Poland).

- Hassan, M.W.; Manowska, A.; Kienberger, T. A breakthrough in achieving carbon neutrality in Poland: Integration of renewable energy sources and Poland’s 2040 energy policy. Energy Rep. 2025, 13, 653–669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wojtaszek, H.; Miciuła, I.; Modrzejewska, D.; Stecyk, A.; Sikora, M.; Wójcik-Czerniawska, A.; Smolarek, M.; Kowalczyk, A.; Chojnacka, M. Energy Policy Until 2050—Comparative Analysis Between Poland and Germany. Energies 2024, 17, 421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tauron. TAURON Group Strategy 2025–2035. 2024. Available online: https://www.tauron.pl/tauron/relacje-inwestorskie/prezentacje (accessed on 17 November 2025). (In Poland).

- ORLEN. ORLEN Group 2035 Strategy; ORLEN: Warsaw, Poland, 2025; Available online: https://www.orlen.pl/pl/o-firmie/strategia (accessed on 17 November 2025). (In Poland)

- ENEA. ENEA Group Development Strategy Until 2035 Presentation. 2024. Available online: https://ir.enea.pl/informacje-dla-inwestorow/zalacznik/2753547 (accessed on 17 November 2025). (In Poland).

- PGE. Energy for a Secure Future. Flexibility. PGE Group’s 2035 Strategy. 2025. Available online: https://www.gkpge.pl/grupa-pge/o-grupie/poznaj-strategie (accessed on 17 November 2025). (In Poland).

- TSO. Transmission Network Development Plan for 2025–2034; Polskie Sieci Elektroenergetyczne (PSE): Warsaw, Poland, 2024; Available online: https://www.pse.pl/-/projekt-nowego-planu-rozwoju-sieci-przesylowej-na-lata-2025-2034-uzgodniony (accessed on 17 November 2025). (In Poland)

- Ministry of Climate and Environment. Energy Policy of Poland Until 2040 (EPP2040); Ministry of Climate and Environment: Warsaw, Poland, 2021. Available online: https://www.gov.pl/web/ia/polityka-energetyczna-polski-do-2040-r-pep2040 (accessed on 17 November 2025). (In Poland)

- Ministry of Climate and Environment. The National Energy and Climate Plan (KPEiK); Ministry of Climate and Environment: Warsaw, Poland, 2019. Available online: https://www.gov.pl/web/klimat/krajowy-plan-na-rzecz-energii-i-klimatu-na-lata-2021-2030---wersja-2019-r (accessed on 17 November 2025). (In Poland)

- Energy Market Agency. Public Thermal Plants and CHP Plants Catalogue as of 31/12/2024; Energy Market Agency: Warsaw, Poland, 2025; ISSN 1899-1920. [Google Scholar]

- Ministry of Climate and Environment. The Statistical Information on Electricity, Monthly Bulletin, Jan–Dec 2024; Energy Market Agency: Warsaw, Poland, 2024; ISSN 1232-5457. [Google Scholar]

- Calorific Values (CV) and CO2 Emission Factors (EC) in 2022 for Reporting Under the Emissions Trading System for 2025. Available online: https://www.kobize.pl/uploads/materialy/materialy_do_pobrania/monitorowanie_raportowanie_weryfikacja_emisji_w_eu_ets/WO_i_WE_do_monitorowania-ETS-2025.pdf (accessed on 17 November 2025). (In Poland).

- Kaszyński, P.; Komorowska, A.; Zamasz, K.; Kinelski, G.; Kamiński, J. Capacity Market and (the Lack of) New Investments: Evidence from Poland. Energies 2021, 14, 7843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Komorowska, A.; Kaszyński, P.; Kamiński, J. Where does the capacity market money go? Lessons learned from Poland. Energy Policy 2023, 173, 113419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaszyński, P. The impact of the capacity remuneration mechanism on the decarbonisation of the energy sector in Poland in the context of the future demand for natural gas for electricity production. Gospod. Surowcami Miner.-Miner. Resour. Manag. 2025, 41, 55–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Kaszyński, P.; Malec, M.; Fijołek, M.; Kamiński, J. Energy Transformation Towards Climate Neutrality by 2050: The Case of Poland Based on CO2 Emission Reduction in the Public Power Generation Sector. Energies 2026, 19, 118. https://doi.org/10.3390/en19010118

Kaszyński P, Malec M, Fijołek M, Kamiński J. Energy Transformation Towards Climate Neutrality by 2050: The Case of Poland Based on CO2 Emission Reduction in the Public Power Generation Sector. Energies. 2026; 19(1):118. https://doi.org/10.3390/en19010118

Chicago/Turabian StyleKaszyński, Przemysław, Marcin Malec, Michał Fijołek, and Jacek Kamiński. 2026. "Energy Transformation Towards Climate Neutrality by 2050: The Case of Poland Based on CO2 Emission Reduction in the Public Power Generation Sector" Energies 19, no. 1: 118. https://doi.org/10.3390/en19010118

APA StyleKaszyński, P., Malec, M., Fijołek, M., & Kamiński, J. (2026). Energy Transformation Towards Climate Neutrality by 2050: The Case of Poland Based on CO2 Emission Reduction in the Public Power Generation Sector. Energies, 19(1), 118. https://doi.org/10.3390/en19010118