A Multi-Objective Optimization Method and System for Energy Internet Topology Based on Self-Adaptive-NSGA-III

Abstract

1. Introduction

- An adaptive dynamic reference point generation method is proposed. It can adaptively control individual evolution based on the population’s iteration status and progress, balancing global and local search capabilities. This method is suitable for multi-objective optimization of the EI topology.

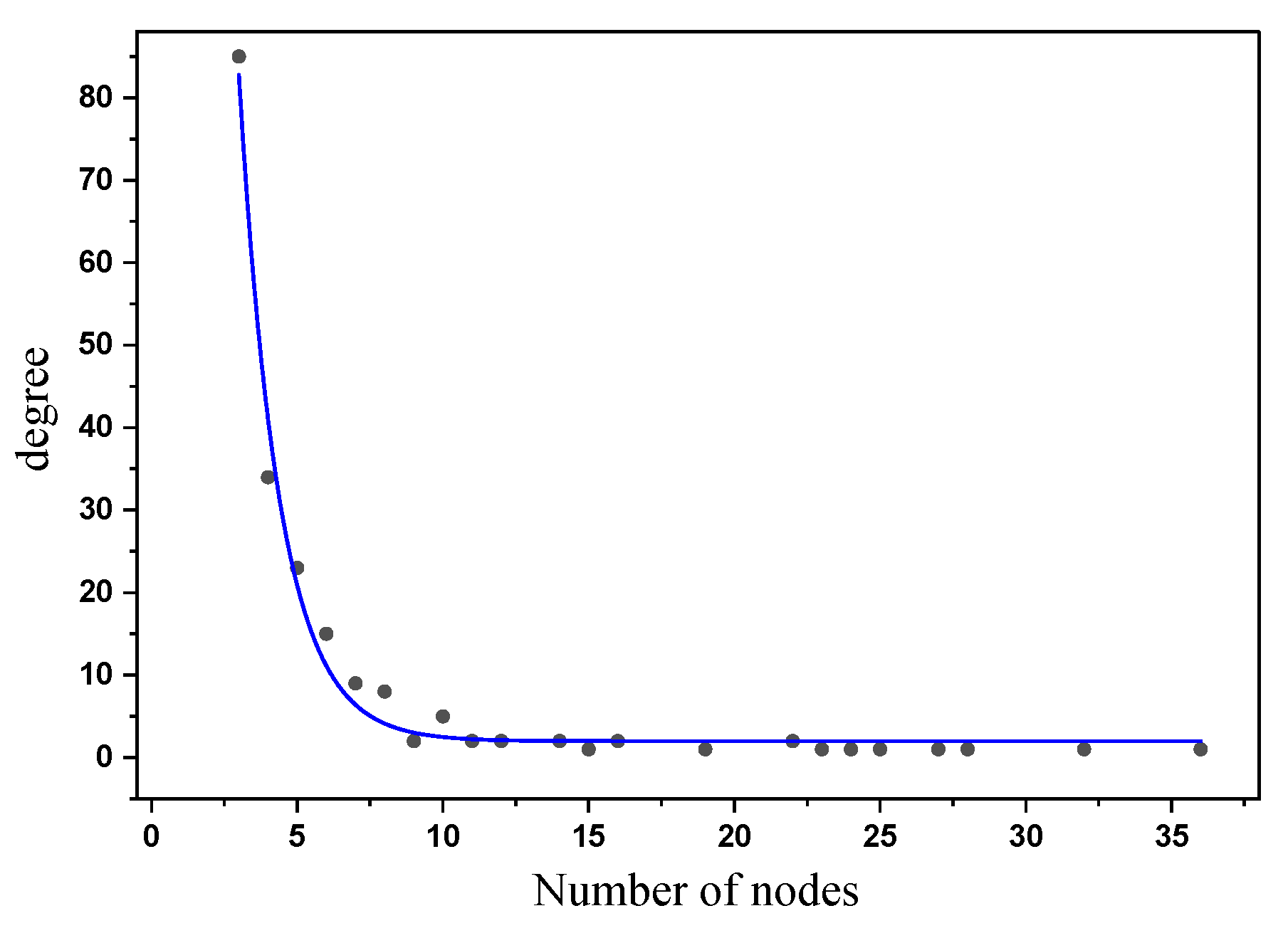

- We design a scale-free network topology optimization method suitable for the NSGA-III algorithm, which can effectively apply to various network topology optimization scenarios while maintaining the degree of node and preserving the scale-free nature of the network topology.

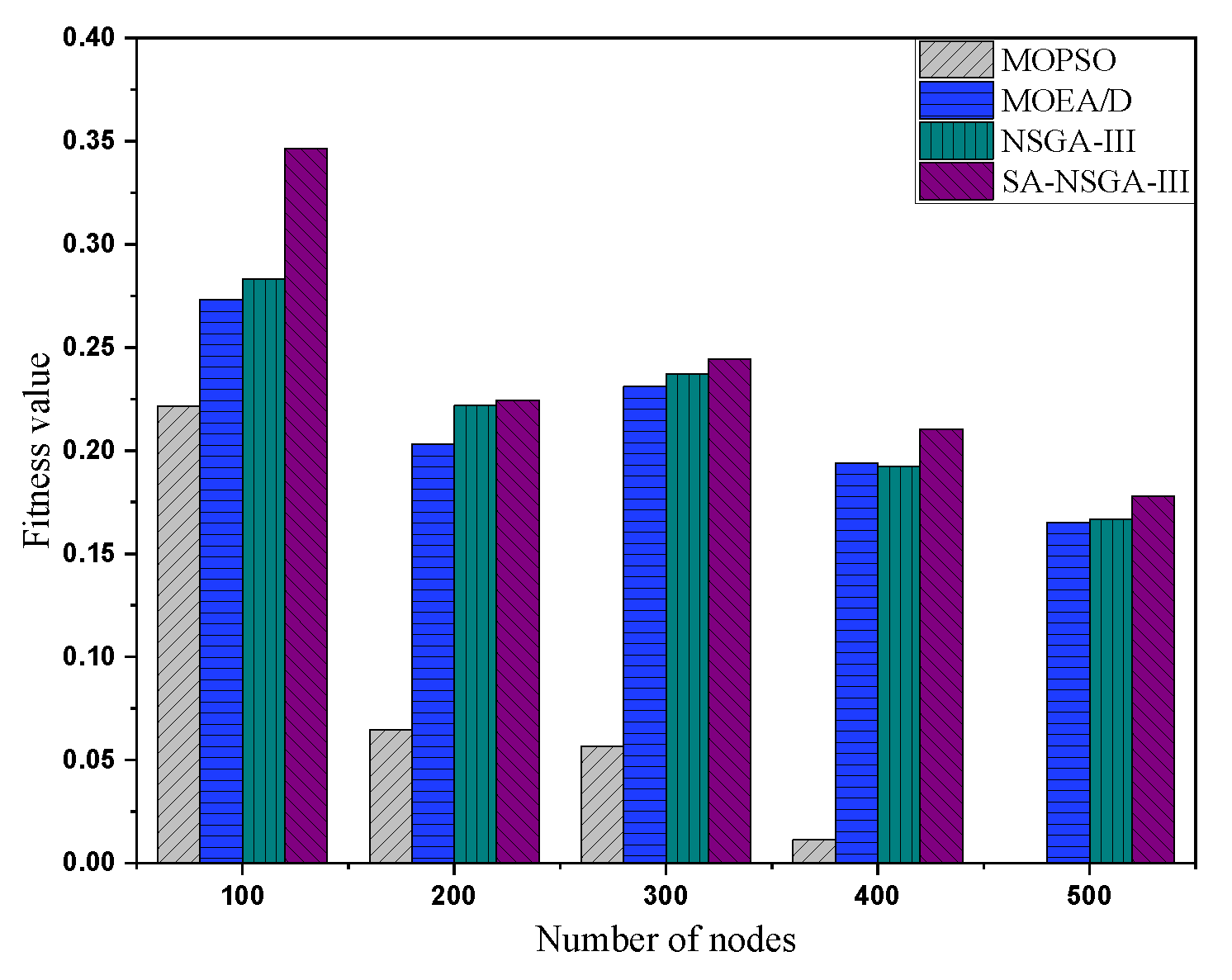

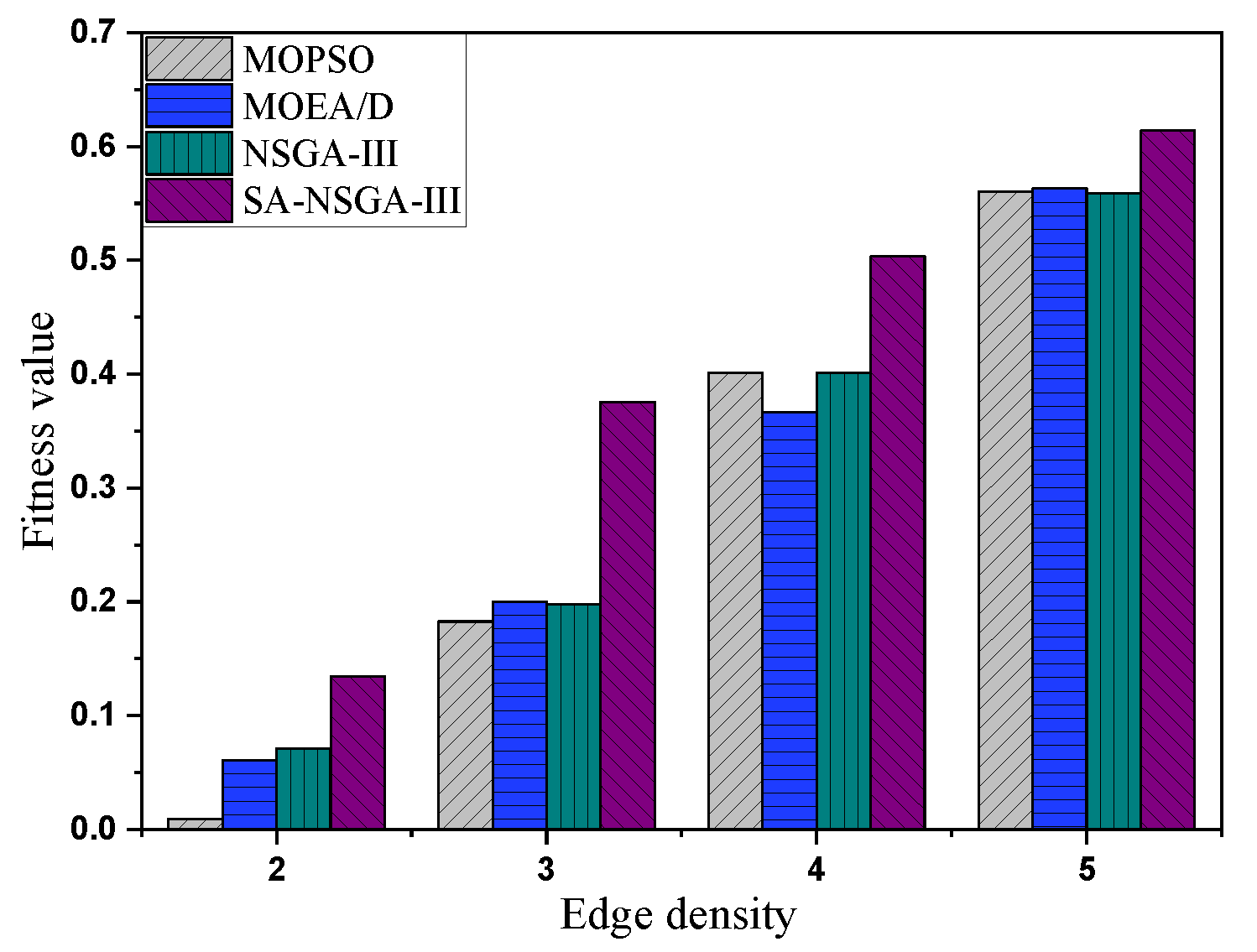

- We validate the advantages of the proposed improved algorithm and the adaptive reference generation method. A large number of experimental results show that the proposed algorithm achieves better fitness gains across the three selected optimization objectives compared to the current schemes.

2. Related Work

2.1. Single Objective Optimization

2.2. MOEA/D Algorithms

2.3. MOPSO Algorithms

2.4. NSGA Algorithms

3. Preliminary Preparation

3.1. Scale-Free Network

3.2. Optimization Based on Free Edges

- 1:

- The four nodes a, b, c, and d of the edges and are all within the communication range r of each other;

- 2:

- The two edges and do not share any common nodes.

- 3:

- Apart from a pair of free edges, the four nodes do not have additional edges that connect to each other.

4. Algorithm Design

4.1. Population Initialization

4.2. Objective Function Definition

4.2.1. Algebraic Connectivity

4.2.2. Robustness

4.2.3. Smallest Average Path Length

4.2.4. Fitness Value

4.3. Genetic Operation

| Algorithm 1 Mutation Operation |

|

| Algorithm 2 Crossover Operation |

|

4.4. Non-Dominated Sort

4.5. Selection of Individuals in the Last Front

4.5.1. Dynamic Reference Point

4.5.2. Normalization

4.6. Reference Point Association and Selection Mechanism

5. Experimental Design and Analysis of Results

5.1. Parameter Settings

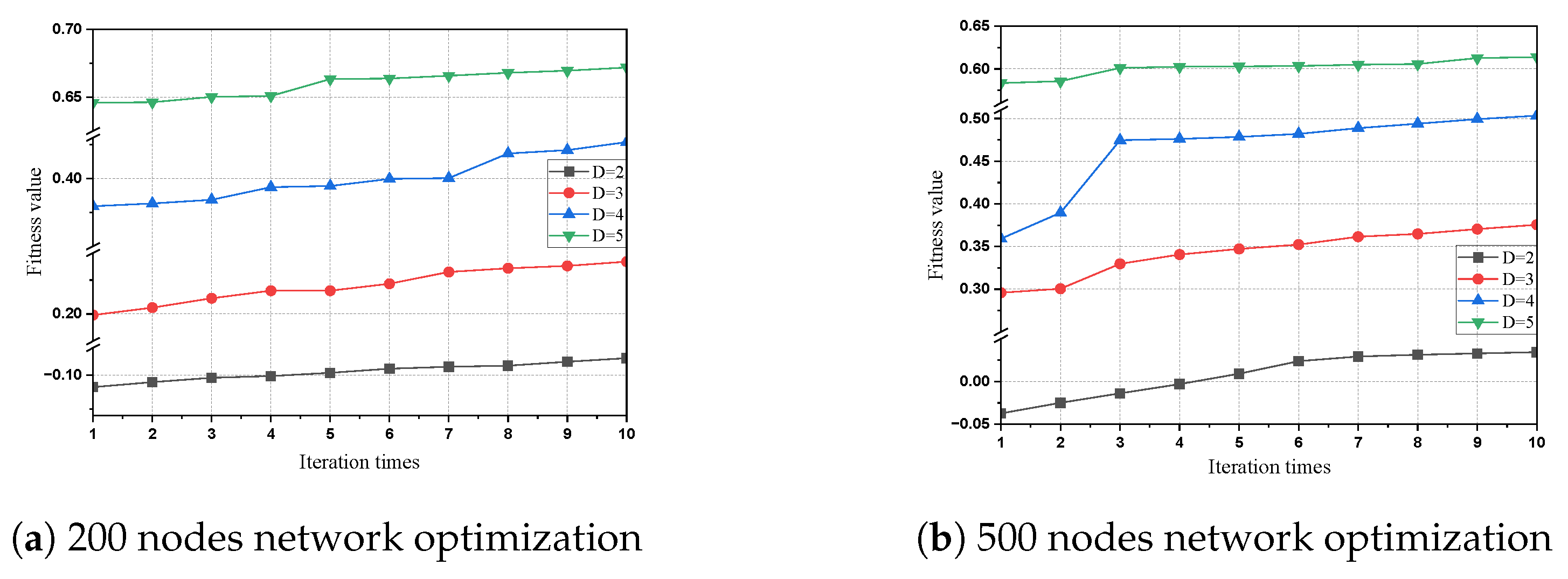

5.2. Optimization at Different Network Densities

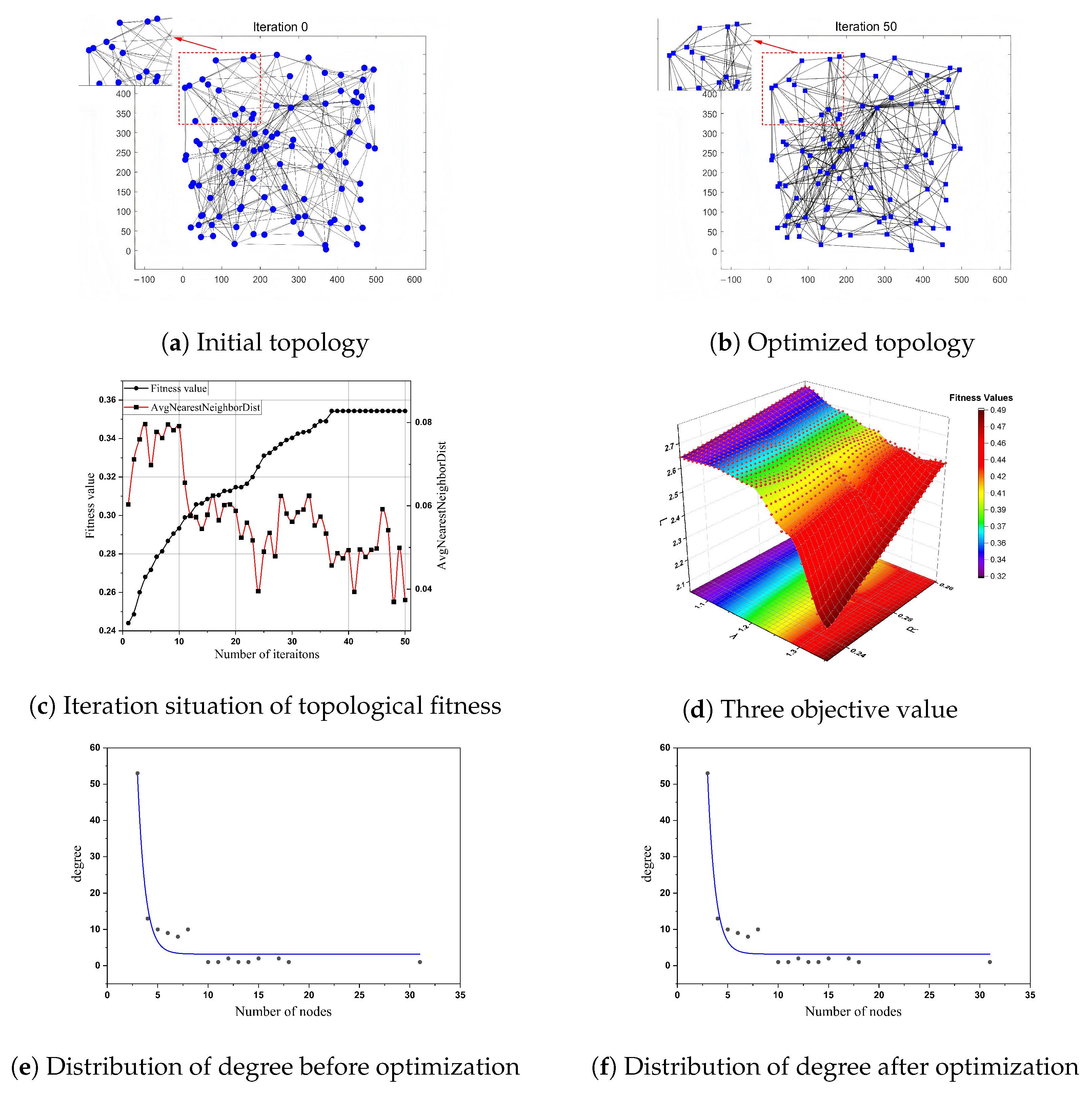

5.3. Comparison Between the Initial Topology and the Optimized Topology

5.4. Comparison of Different Algorithms

5.5. Comparison of Different Reference Point Generation Methods

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Xue, Z.; Xu, Y.; Han, Y.; Gao, F.; Jiang, W.; Zhu, Y.; Li, K.; Guo, Q.; Sun, J. Energy internet: A novel green roadmap for meeting the global energy demand. In Proceedings of the 2021 IEEE 5th Conference on Energy Internet and Energy System Integration (EI2), Taiyuan, China, 22–24 October 2021; pp. 3855–3860. [Google Scholar]

- Fencl, T.; Burget, P.; Bilek, J. Network topology design. Control Eng. Pract. 2011, 19, 1287–1296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strogatz, S.H. Exploring complex networks. Nature 2001, 410, 268–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiu, T.; Zhao, A.; Xia, F.; Si, W.; Wu, D.O. ROSE: Robustness strategy for scale-free wireless sensor networks. IEEE/ACM Trans. Netw. 2017, 25, 2944–2959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, D.; Qiu, T.; Deonauth, N.; Zhao, A. A small world model for improving robustness of heterogeneous networks. In Proceedings of the 2015 IEEE Global Conference on Signal and Information Processing (GlobalSIP), Orlando, FL, USA, 14–16 December 2015; pp. 849–852. [Google Scholar]

- Li, R.H.; Yu, J.X.; Huang, X.; Cheng, H.; Shang, Z. Measuring robustness of complex networks under MVC attack. In Proceedings of the 21st ACM international Conference on Information and Knowledge Management, Maui, HI, USA, 29 October–2 November 2012; pp. 1512–1516. [Google Scholar]

- Hebal, S.; Harous, S.; Mechta, D. Energy routing challenges and protocols in energy internet: A survey. J. Electr. Eng. Technol. 2021, 16, 3197–3212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, M.; Guan, S.; Guo, W.; Chen, J.; Zheng, H.; Qin, T. Deployment and adaptive optimization strategies for B5G heterogeneous edge base station microgrid using K-means and MPC. Tsinghua Sci. Technol. 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, Z.; Chung, C.; Wang, Q.; Chen, H.; Yang, H.; Wu, C. Fortifying Renewable-Dominant Hybrid Microgrids: A Bi-Directional Converter Based Interconnection Planning Approach. Engineering 2025, 51, 130–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghiasi, M.; Wang, Z.; Mehrandezh, M.; Jalilian, S.; Ghadimi, N. Evolution of smart grids towards the Internet of energy: Concept and essential components for deep decarbonisation. IET Smart Grid 2023, 6, 86–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hussain, H.M.; Narayanan, A.; Nardelli, P.H.; Yang, Y. What is energy internet? Concepts, technologies, and future directions. IEEE Access 2020, 8, 183127–183145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herrmann, H.J.; Schneider, C.M.; Moreira, A.A.; Andrade, J.S.; Havlin, S. Onion-like network topology enhances robustness against malicious attacks. J. Stat. Mech. Theory Exp. 2011, 2011, P01027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buesser, P.; Daolio, F.; Tomassini, M. Optimizing the robustness of scale-free networks with simulated annealing. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Adaptive and Natural Computing Algorithms, Ljubljana, Slovenia, 14–16 April 2011; pp. 167–176. [Google Scholar]

- Rong, L.; Liu, J. A heuristic algorithm for enhancing the robustness of scale-free networks based on edge classification. Phys. A Stat. Mech. Its Appl. 2018, 503, 503–515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, M.; Liu, J. A memetic algorithm for enhancing the robustness of scale-free networks against malicious attacks. Phys. A Stat. Mech. Its Appl. 2014, 410, 131–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiu, T.; Yang, X.; Chen, N.; Zhang, S.; Min, G.; Wu, D.O. A self-adaptive robustness optimization method with evolutionary multi-agent for IoT topology. IEEE/ACM Trans. Netw. 2023, 32, 1346–1361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, Y.; Liu, C.; Liu, S.; Liu, Y.; Wu, Y. SmartTRO: Optimizing topology robustness for Internet of Things via deep reinforcement learning with graph convolutional networks. Comput. Netw. 2022, 218, 109385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Konstantinidis, A.; Yang, K. Multi-objective energy-efficient dense deployment in wireless sensor networks using a hybrid problem-specific MOEA/D. Appl. Soft Comput. 2011, 11, 4117–4134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, C.; Ding, C.; Xiao, L.; Cheng, F.; Ai, Z. Deep belief ensemble network based on MOEA/D for short-term load forecasting. Nonlinear Dyn. 2021, 105, 2405–2430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Liu, J.; Jin, Y. A computationally efficient evolutionary algorithm for multiobjective network robustness optimization. IEEE Trans. Evol. Comput. 2021, 25, 419–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lai, D.T.C.; Sato, Y. An empirical study of cluster-based MOEA/D bare bones PSO for data clustering. Algorithms 2021, 14, 338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, L.; Yang, Y.; Tang, Z.; He, Y.; Luo, X. FCAN-MOPSO: An improved fuzzy-based graph clustering algorithm for complex networks with multiobjective particle swarm optimization. IEEE Trans. Fuzzy Syst. 2023, 31, 3470–3484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, R.; Wang, H.; Shi, L.; Han, C.; He, Q.; Che, Y.; Luo, L. A novel framework of MOPSO-GDM in recognition of Alzheimer’s EEG-based functional network. Front. Aging Neurosci. 2023, 15, 1160534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, J.; Pu, C.; Ding, S.; Cao, G.; Xia, C.; Pardalos, P.M. Multi-objective optimization of transport processes on complex networks. IEEE Trans. Netw. Sci. Eng. 2022, 10, 780–794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, W.; Sun, B.; Huang, Y.; Mahmoodi, S. Adaptive complex network topology with fitness distance correlation framework for particle swarm optimization. Int. J. Intell. Syst. 2022, 37, 5217–5247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taleb, S.M.; Baiche, K.; Meraihi, Y.; Yahia, S.; Mirjalili, S.; Ramdane-Cherif, A. A binary multi-objective approach for solving the WMNs topology planning problem. Peer-to-Peer Netw. Appl. 2025, 18, 1–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, K.; Xu, B.; Guo, S.; Gong, W.; Chatzinotas, S.; Maity, I.; Zhang, Q.; Ren, Q. Non-grid-mesh topology design for megaleo constellations: An algorithm based on nsga-iii. IEEE Trans. Commun. 2024, 72, 2881–2896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, Q.; Yang, F.; Song, W.; Ying, C. A Hierarchical Reservation Adaptive Evolutionary Algorithm Based on NSGA-II for Multiobjective Optimization of Networks. In Proceedings of the 2023 9th International Conference on Computer and Communications (ICCC), Chengdu, China, 8–11 December 2023; pp. 2269–2274. [Google Scholar]

- Xiong, A.; Tong, Y.; Guo, S.; Wang, Y.; Shao, S.; Mei, L. An Optimal Allocation Method of Power Multimodal Network Resources Based on NSGA-II. Wirel. Commun. Mob. Comput. 2021, 2021, 9632277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, N.; Qiu, T.; Si, W.; Wu, D.O. DAiMo: Motif Density Enhances Topology Robustness for Highly Dynamic Scale-free IoT. IEEE Trans. Mob. Comput. 2024, 24, 2360–2375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ming, Y.; Yang, J.; Cao, J.; Zhou, Z.; Xing, C. Distributed energy sharing in energy internet through distributed averaging. Tsinghua Sci. Technol. 2018, 23, 233–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Trappe, W. Topology adaptation for robust ad hoc cyberphysical networks under puncture-style attacks. Tsinghua Sci. Technol. 2015, 20, 364–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schneider, C.M.; Moreira, A.A.; Andrade, J.S., Jr.; Havlin, S.; Herrmann, H.J. Mitigation of malicious attacks on networks. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2011, 108, 3838–3841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shimizu, N.; Mori, R. Average shortest path length of graphs of diameter 3. In Proceedings of the 2016 Tenth IEEE/ACM International Symposium on Networks-on-Chip (NOCS), Nara, Japan, 31 August–2 September 2016; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

| Parameters | Value | Parameters | Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| (m2) | |||

| D | |||

| r | 250 m | ||

| N | |||

| G | |||

| M | 50 | ||

| Algorithm | Time Complexity |

|---|---|

| ) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Wang, C.; Liao, Y.; Gao, X.; Zhang, Z.; Guo, W.; Chen, J.; Qin, T. A Multi-Objective Optimization Method and System for Energy Internet Topology Based on Self-Adaptive-NSGA-III. Energies 2026, 19, 108. https://doi.org/10.3390/en19010108

Wang C, Liao Y, Gao X, Zhang Z, Guo W, Chen J, Qin T. A Multi-Objective Optimization Method and System for Energy Internet Topology Based on Self-Adaptive-NSGA-III. Energies. 2026; 19(1):108. https://doi.org/10.3390/en19010108

Chicago/Turabian StyleWang, Chaomin, Yang Liao, Xuchong Gao, Zhanyong Zhang, Wenhao Guo, Junjiang Chen, and Tuanfa Qin. 2026. "A Multi-Objective Optimization Method and System for Energy Internet Topology Based on Self-Adaptive-NSGA-III" Energies 19, no. 1: 108. https://doi.org/10.3390/en19010108

APA StyleWang, C., Liao, Y., Gao, X., Zhang, Z., Guo, W., Chen, J., & Qin, T. (2026). A Multi-Objective Optimization Method and System for Energy Internet Topology Based on Self-Adaptive-NSGA-III. Energies, 19(1), 108. https://doi.org/10.3390/en19010108