1. Introduction

Due to the limited supply and harmful environmental impacts of nonrenewable energy sources, there is a growing demand for renewable energy sources across the world. One such renewable energy source is biofuel, or fuel produced from organic biomass [

1]. This energy source has seen significant growth, with global biofuel production surpassing 1400 TWh in 2024 as shown in

Figure 1 [

2].

Traditional biofuels (or first-generation biofuels) often rely on food crops for a biomass source, which scholars have argued creates some negative impacts in the food and water sectors when examined in the context of the Food–Energy–Water (FEW) Nexus [

3,

4,

5]. While many definitions for the FEW Nexus may be found in the literature, it is defined here as an analysis framework for environmental problems that emphasizes the interrelationship between the food, energy, and water sectors, as well as the idea that these sectors should be prioritized equally [

6]. First-generation biofuel production (and its associated crop consumption) was found to have negative impacts in both the water and food sectors when examined in this context.

The negative energy-to-water impacts of biofuel production include the fact that in 2017, it accounted for 2–3% of all global water consumption while only meeting 4% of the global demand for transportation fuels [

4,

5]. When considering that this is only one source of water withdrawals across the major categories of municipal, industrial, and agricultural usage, it is clear that the water footprint of first-generation biofuels is significant [

7,

8]. The crop cultivation associated with first-generation biofuels also presents a water quality issue from agricultural runoff causing fertilizers and pesticides to leach into runoff, with fertilizer-heavy crops such as U.S.-grown corn and Brazil-grown sugar cane being especially hazardous in this regard [

5,

9,

10,

11].

The negative energy-to-food impacts, on the other hand, primarily involve the fact that the aforementioned reliance of first-generation biofuels on food crops can lead to competition between food needs and energy needs [

3,

4,

5,

12]. This issue can be exacerbated by the fact that rising nonrenewable fuel (oil) prices, combined with environmental concerns, can cause existing food crop streams to switch to industrial (biofuel) uses, driving increases in food prices—an issue that has been termed the food–energy–environment trilemma or the food–feed–fuel trilemma in the previous literature [

12,

13,

14]. The end result of this competition is that first-generation biofuel production consumes an amount of food and cropland that could be used to reduce food poverty by as much as 30% [

5].

One potential solution to this FEW Nexus problem is the usage of alternative biomass sources for biofuel production. Biofuels reliant on these sources are termed second- and third-generation biofuels [

15]. Babcock [

3] suggests that the energy-to-food impacts of biofuel production could be mitigated by using higher-generation biomass sources that do not require additional cropland, particularly those that are of low (or negative) economic value, or those that are treated as waste. Similarly, Mathioudakis et al. [

16] indicates that second-generation biomass sources may be able to achieve lower water footprints than first-generation sources, mitigating the energy-to-water impacts as well.

One biomass source that merits further consideration is food waste, which is classed as a second-generation biomass source because it is one of the primary components of municipal solid waste [

15,

17]. Food waste issues may be responsible for large economic losses, with a loss of

$161.6 billion being attributed to food wastes in the U.S. in 2010 alone (see

Figure 2 for a breakdown by specific food waste type) [

18]. The usage of food waste as a biomass could potentially mitigate these losses while simultaneously providing the benefits of second-generation biofuels mentioned previously—food waste is already being generated in large quantities and is typically sent to municipal solid waste landfills [

19,

20], which suggests that the diversion of food waste streams to biofuel production would not significantly stress the world’s food and water resources. Many previous studies have examined the usage of a variety of food wastes in biofuel production. Most commonly, the usage of brewery waste (yeast, spent grains, spent lees, etc.) has been covered, but other wastes including (but not limited to) meat waste, dairy waste, coffee grounds, vegetable waste, and fruit waste have also been examined [

21,

22,

23,

24].

One challenge with the commercialization of food waste-based biofuels is that second-generation biomass sources are not suitable for direct conversion into bioethanol and biodiesel using the same technologies as first-generation biomass sources [

25]. Instead, it is more viable to use thermochemical processes such as pyrolysis, transesterification, steam reforming, or the focus of this study: hydrothermal liquefaction (HTL; also termed direct biomass liquefaction) [

26,

27]. In HTL, a wet biomass feedstock is digested at high temperatures and pressures, producing bio-oil (or bio-crude oil) as a main product and three by-products: an aqueous co-product (ACP), a gaseous co-product (GCP), and biochar [

28].

The HTL reaction pathway can be described using a series of three steps: depolymerization, decomposition, and recombination [

29]. In depolymerization, the polymer macromolecules within the feedstock are sequentially broken down into monomers and dissolved [

26,

30]. Then, in decomposition, oxygen is removed from the biomass as water and carbon dioxide while the carbohydrate polymers break down further through a variety of smaller reactions [

31,

32]. The result of depolymerization and decomposition is that the biomass feedstock is broken down or degraded into many small and reactive compounds, which are dissolved in the removed water [

26,

32]. These compounds then polymerize during the recombination step, producing the bio-oil, GCP, and biochar (leaving the ACP as a by-product) [

26,

29]. This process is summarized in

Figure 3.

HTL was selected for examination because of its reliance on a wet feedstock and aqueous medium for the reaction [

33,

34]. This provides an advantage of similar technologies such as pyrolysis, which rely on dry feedstocks (<10% water) and consequently require energy-intensive feedstock dewatering steps [

35]. Bio-oil produced via pyrolysis has also been found to contain a lower energy content than is produced via other technologies, providing another advantage to HTL [

33]. Additionally, many studies have examined the use of HTL for biofuel production (and the factors that affect this process), providing a basis for this study’s methodology and analysis. Multiple prior studies have found that the temperature at which the HTL reaction takes place heavily influences the quantity and composition of the bio-oil produced, with temperatures ranging from 300 to 350 °C being cited as optimal [

36,

37]. Chen et al. [

37] further notes that while the duration of the reaction is less important, a reaction time of 30 min is optimal.

While the bio-oil is the main product of HTL, the three by-products (ACP, GCP, and biochar) warrant consideration as well, as their proper management is important to the commercialization of HTL technologies. The ACP is a wastewater by-product which contains high concentrations of nutrient pollutants, necessitating treatment before it can be discharged to a receiving water body [

38]. Previous studies have examined various potential applications and treatment methods for ACP, including anaerobic digestion, nutrient recovery via struvite precipitation, and microalgae cultivation [

38,

39,

40,

41].

The biochar may be considered a solid waste, but research has shown that it has potential applications as a fuel source, as an adsorbent for metals or dyes, as an additive for livestock feed, and in anaerobic digestion processes [

22,

42,

43,

44,

45,

46,

47,

48]. A more recent research trend related to biochar is its potential application as a soil amendment for agricultural purposes. Several studies have found a positive impact of biochar additions on the growth of various crop plants [

49,

50,

51,

52,

53], although other such as Nesheim [

25] have yielded less conclusive results, indicating a need for further research in this area.

Unlike the ACP and biochar, the GCP has been relatively unexplored in the previous literature. While the treatment challenges and potential applications of the GCP have not been expanded upon, a study of GCP produced from the HTL of brewery grains found that the by-product was composed of approximately 95% carbon dioxide (CO

2) and 1.6% diatomic hydrogen (H

2), with trace quantities of diatomic nitrogen (N

2), carbon monoxide (CO), methane (CH

4), short-chain alkanes, and short-chain alkenes being identified as well [

28].

The purpose of this study is to collect and provide data that may be used to evaluate the feasibility of using food waste feedstocks as a biomass source for commercial biofuel production via HTL. This data includes information regarding the HTL product and by-product yield distribution and ACP characteristics for four different food waste feedstocks: spent coffee grounds, spent brewery grains, pear wine lees, and homogenized honeydew skins. These feedstocks were selected for their high water contents, making them suitable for use in HTL reactions. The secondary goal of this study is to provide a review of previous studies on the HTL of food waste feedstocks, focusing on observations and trends found during the comparison of different studies that analyzed the same food waste feedstocks. This study provides novel insight by performing a comprehensive comparison of ACP nutrient and COD profiles across four food wastes under identical operating conditions.

2. Materials and Methods

This study was carried out in a series of five phases: (1) characterization and preparation of food waste feedstocks, (2) HTL of food wastes, (3) solid–liquid phase separation of products, (4) liquid–liquid phase separation of products, and (5) water quality analysis of the ACP. As mentioned previously, the four food wastes chosen for analysis were spent brewery grains, pear wine lees, spent coffee grounds, and homogenized honeydew skins. The grains, pear lees, and coffee grounds were selected due to the coverage of similar feedstocks in existing literature such as Bauer et al. [

21] and Liakos et al. [

24], which allowed for the comparison of each study’s results. The honeydew skins, on the other hand, were selected as a novel feedstock due to regular availability from the source location. The grains were sourced from Ocmulgee Brewpub, Macon, GA, USA; the pear lees were sourced from Myron Winery, Macon, GA, USA; the coffee grounds were sourced from Z Beans Coffee, Macon, GA, USA; and the honeydew skins were sourced from Fresh Food Company, Macon, GA, USA (homogenization was conducted via blender in the research lab). Feedstocks were frozen at −17.8 °C after collection and were thawed in a laboratory refrigerator for 48 h prior to experimentation.

The characterization and preparation of food waste feedstocks was conducted as in Bauer et al. [

21] and Nesheim [

25]. A solids analysis was conducted to determine the water content, total solids (TS), volatile solids (VS; organic solids content), and fixed solids (FS; ash content) of each food waste according to ASTM standards E1756-08R15 and E1755-01R20 (n = 3 replicates for all food wastes) [

54,

55]. Food wastes which had water contents of less than 80% by mass were diluted via the addition of deionized water to a water content of 80% by mass (20% TS by mass). Due to its especially high water content, it was feasible to conduct a water quality analysis of the pear lees as well, using the same methodology described for the water quality analysis of the ACP described later in this section.

The HTL of food waste was conducted using a benchtop Parr Hast 300 mL reactor (Parr Instrument Company, Moline, IL, USA) with a quartz liner, external heater, asbestos insulation, and a Parr 4848 reactor controller (Parr Instrument Company, Moline, IL, USA), as in Nesheim [

25]. To prepare for each HTL run, a 100 g sample of the selected food waste feedstock was prepared in the quartz liner and loaded into the machine (n = 3 replicates was targeted for each food waste feedstock, although n = 4 was achieved for pear lees, while n = 2 was achieved for honeydew skins due to supply limitations). The reactor system was pressurized to 100 psi with diatomic nitrogen gas (N

2) and purged three times before being pressurized to 100 psi once more. The reactor’s motor was set to run at 200 rpm. Each HTL run had three phases: a heating phase (1 h and 45 min), a digestion phase (30 min), and a natural cooling phase (approximately 3 to 4 h). During the heating phase, the system was heated to 300 °C using a 2.67 °C/min ramp, inducing a pressure increase to between 1300 and 1500 psi. The system was held at these conditions during the digestion phase, allowing the HTL reaction to progress. Finally, during the cooling phase, the heater was deactivated and removed from the reactor, allowing the system to naturally cool to room temperature. The GCP was vented from the system at the end of the cooling phase, leaving a mixture of the bio-oil, ACP, and biochar.

The separation of the three remaining products was conducted as in Nesheim [

25]. The first phase of this process was the removal of the biochar in a solid–liquid phase separation, which was performed by passing the bio-oil/ACP/biochar mixture through pre-weighed 1.5 μm glass microfiber filters using a vacuum filtration setup with a Buchner funnel (Fisher Scientific, Pittsburgh, PA, USA). This allowed the solid biochar to be separated from the mixture, weighed, dried at 105 °C, and weighed again. The liquid losses during filtration were quantified as the difference between pre-drying and post-drying masses. Following this, the vs. (organic solids) and FS (ash) content of the dried biochar was quantified according to ASTM standard E1755-01R20 [

55]. A summary of this process is shown in

Figure 4a.

The second phase of the product separation process was the isolation of the bio-oil and ACP in a liquid–liquid phase separation, using the methodology of Nesheim [

25]. The process liquid (i.e., the bio-oil/ACP mixture) was pipetted into a series of pre-weighed 15 mL glass vials, with dichloromethane (DCM) being added to each vial to achieve a 1:2 process liquid-to-DCM volume ratio. Typically, 4 mL of process liquid and 8 mL of DCM were added to each vial (note that at a density of 1.33 g/mL, the typical mass of DCM was 10.64 g) [

56]. The vials were then centrifuged at 4000 rpm for a period of 14 min, catalyzing the phase separation. After centrifuging, the ACP had risen to the top of each vial, leaving a bio-oil/DCM mixture at the bottom. The ACP was pipetted out of each vial and weighed, while the remaining mixture was placed uncapped under a fume hood to facilitate the evaporation of the DCM. After the complete evaporation of the DCM had been ensured, the remaining bio-oil was weighed. The liquid losses during filtration were then added to the masses of bio-oil and ACP. In this calculation, it was assumed that the ratio of bio-oil to ACP in the liquid losses was the same as the ratio of bio-oil to ACP observed in the liquid-liquid phase separation. Consequently, this ratio was maintained in the final result. Because the GCP had been vented from the system, its mass was calculated indirectly using a mass balance at this point. The measured masses of bio-oil, ACP, and biochar were subtracted from the input mass (100 g), yielding the mass of GCP. A summary of this process is shown in

Figure 4b.

Figure 4.

Visual summary of the experimental methodology for: (

a) The solid–liquid phase separation of biochar from bio-oil and ACP; (

b) The liquid–liquid phase separation of bio-oil and ACP, as adapted from Nash et al., 2025 [

57].

Figure 4.

Visual summary of the experimental methodology for: (

a) The solid–liquid phase separation of biochar from bio-oil and ACP; (

b) The liquid–liquid phase separation of bio-oil and ACP, as adapted from Nash et al., 2025 [

57].

The water quality analysis of the ACP was conducted using Hach Test ‘N Tube (TNT) (Hach Company, Loveland, CO, USA)test kits and a DRB200 digital spectrophotometer. Five water quality parameters were evaluated according to their respective Hach standard procedures: total nitrogen (TNT 828), nitrate (TNT 836), total phosphorus (TNT 845), reactive phosphorus (TNT 845), and chemical oxygen demand (COD; high range+) [

58,

59,

60,

61]. Two iterations of each test were conducted for each ACP sample produced from the HTL of grains, pear lees, and coffee grounds, while three iterations were conducted for the ACP samples produced from honeydew skins to account for the lower number of HTL runs conducted for this food waste (n = 6 replicates for grain, coffee grounds, and honeydew skins; n = 8 replicates for pear lees).

4. Conclusions

Biomass-based fuels, or biofuels, present a promising solution to the issues presented by the usage of nonrenewable energy sources. These fuels present their own problems; however, due to their negative impacts in the food and water sectors [

3,

4,

5]. The usage of food waste as a biomass feedstock in HTL processes presents a potential solution to this conundrum, which this research seeks to examine.

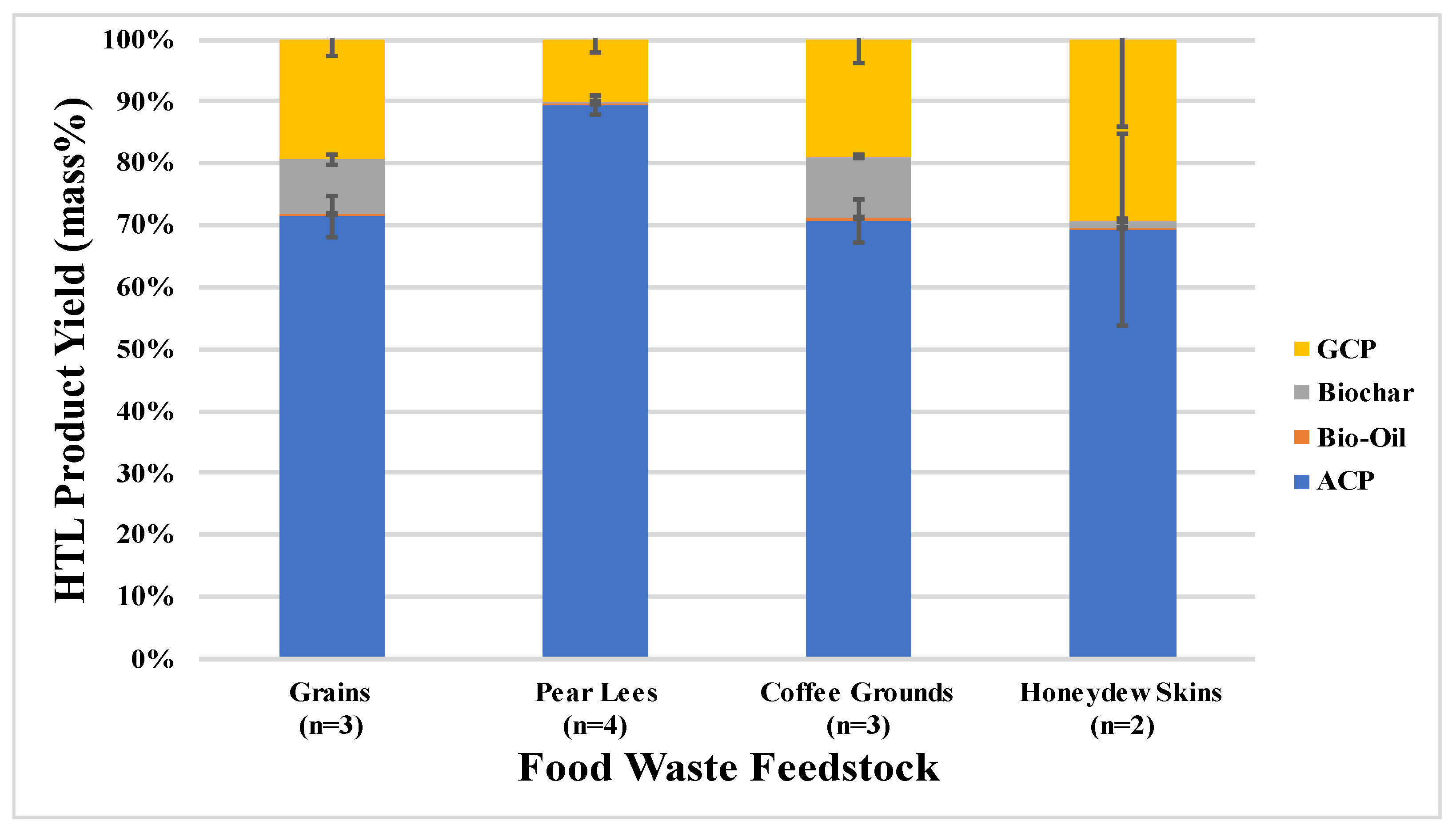

This research explored the effects of varying food waste feedstocks (spent brewery grains, pear wine lees, spent coffee grounds, and homogenized honeydew skins) on the yield and characteristics of the products and by-products of the HTL conversion process. A mass yield distribution analysis found that of the four feedstocks, the spent coffee grounds produced the largest percentage of bio-oil and biochar, the pear lees produced the highest percentage of ACP and the honeydew skins produced the highest percentage of biogas. Additionally, the pear lees yielded the highest concentration of ash in its biochar, while the honeydew skins yielded the lowest pollutant concentrations in its ACP.

A comparison of these results with pre-existing literature data found that additional factors, such as HTL reaction conditions, feedstock preparation techniques (such as atmospheric drying), or smaller variations in feedstock type (i.e., different types of wine lees) may have impacted the mass yield distributions and ACP characteristics of the HTL products.

For future research on the HTL of food waste feedstocks, it is recommended that specific attention be given to the source, production, and other ‘fine details’ that may contribute to or affect the categorization of food waste feedstocks, to ensure the comparability of results between studies. Additionally, further research may be needed to gain a deeper understanding of the impact of factors such as feedstock preparation techniques and HTL reaction conditions on the characteristics of the HTL products (particularly the ACP and biochar), as the existing literature does not explore these potential effects.