Robust Optimal Dispatch of Microgrid Considering Flexible Demand-Side

Abstract

1. Introduction

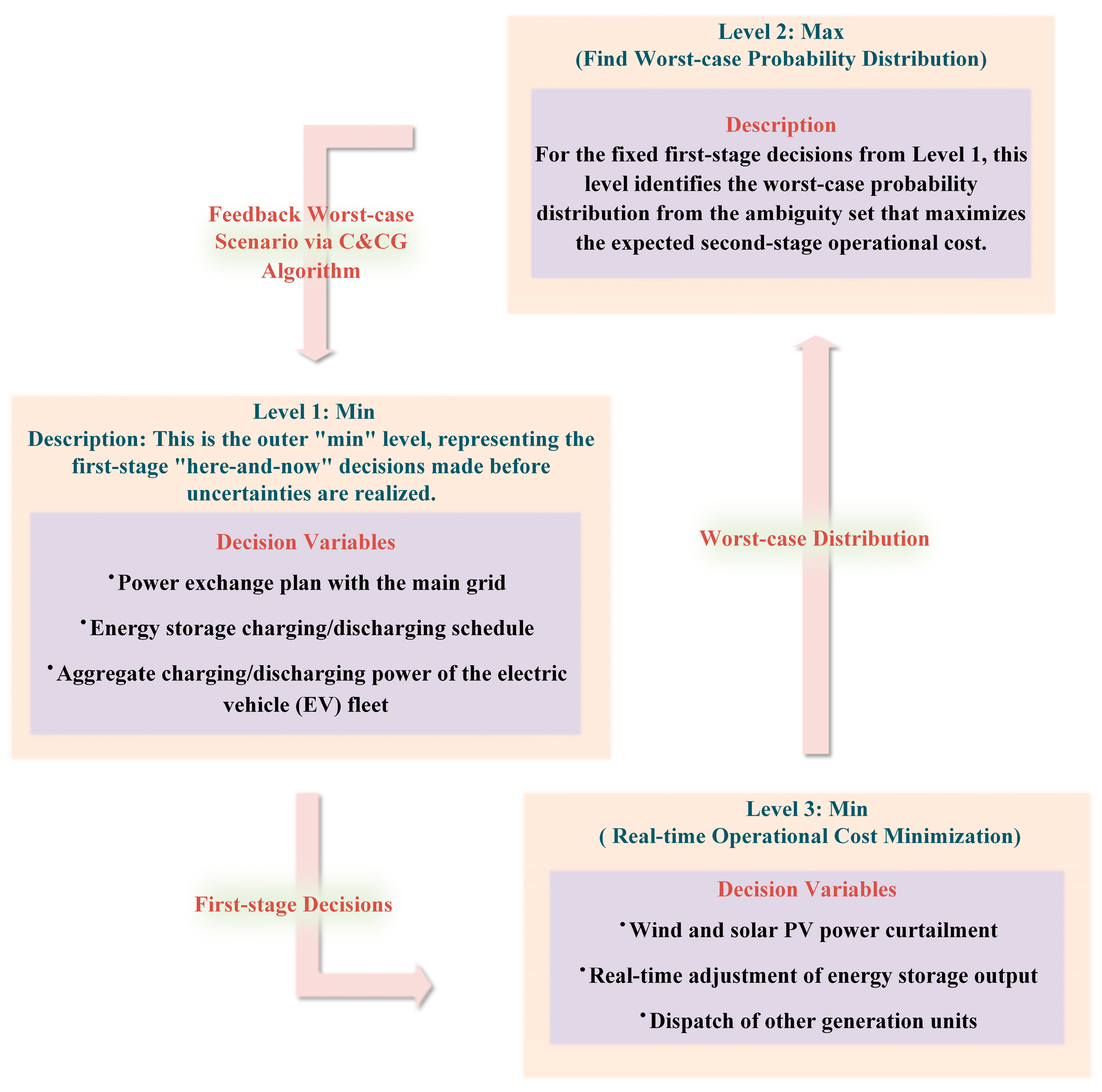

- A three-level min–max–min DRO framework integrating flexible demand-side resources. This structure uniquely embeds the search for the worst-case probability distribution within the optimization process, bridging the economic focus of stochastic optimization and the robustness of traditional robust optimization without relying on accurate probability distributions or being overly conservative.

- An ambiguity set for renewable generation based on KL divergence, with a clear interpretation of the risk parameter ρ. Chosen for its computational practicality, the KL divergence allows the model to handle distributional uncertainty. The parameter ρ serves as an adjustable risk-aversion lever, enabling decision-makers to balance economy and robustness based on data availability and risk preference.

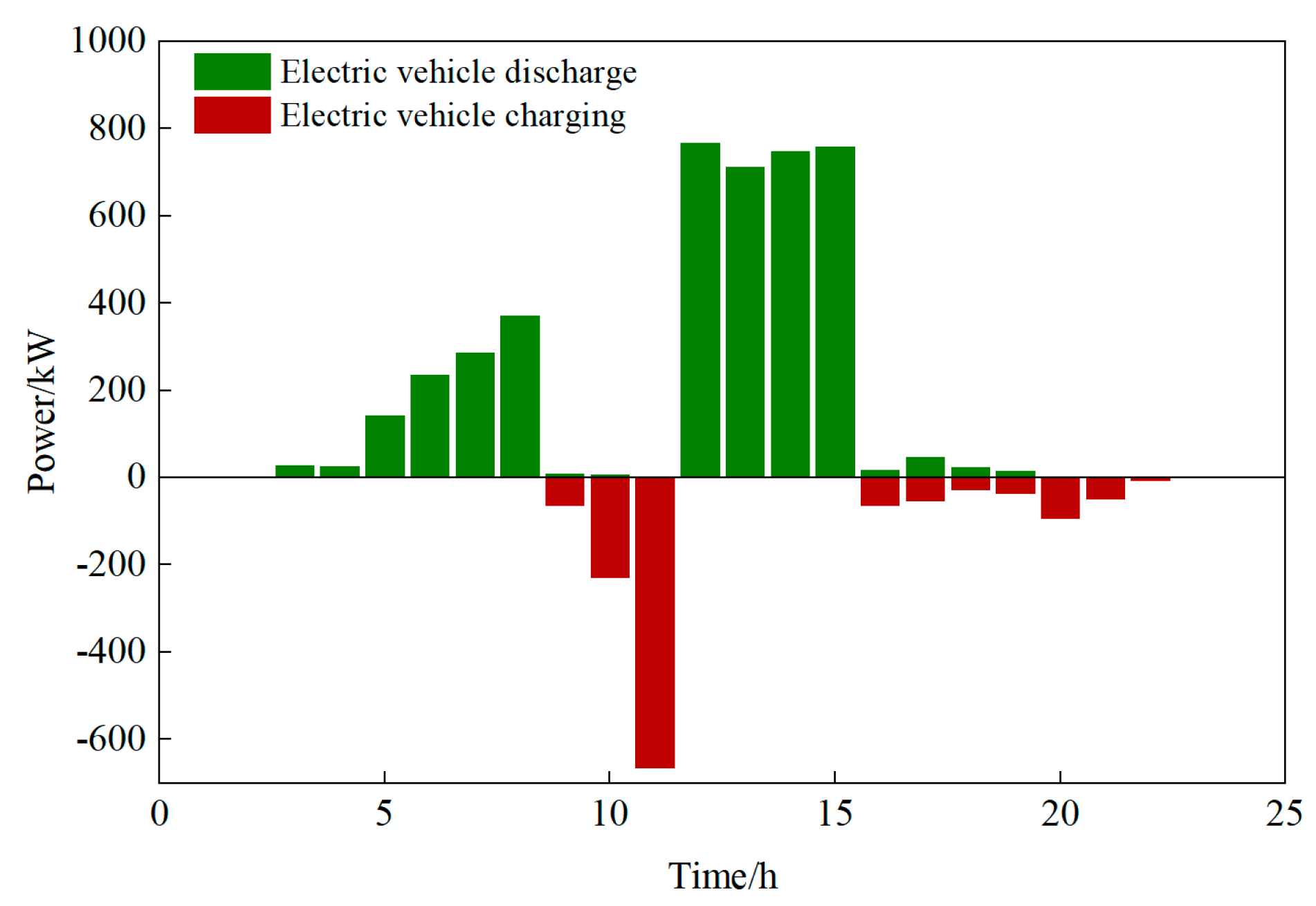

- A coordinated microgrid scheduling model for EV clusters and adjustable loads, solved efficiently. The model aggregates EVs as a dispatchable unit and coordinates them with shiftable and interruptible loads. The complex three-level problem is effectively solved using the C&CG algorithm, ensuring computational feasibility for practical dispatch systems.

2. Microgrid System Architecture and Optimal Operation Model

2.1. Two-Stage Distributionally Robust Optimization Model for Microgrid

- Temporal Decision Stages

- 2.

- Optimization Levels

- (1)

- First stage: the charging and discharging costs of electric vehicles.

- (2)

- Second Stage: Collaboration cost between the Microgrid and the distribution network, as well as the costs of wind curtailment and photovoltaic curtailment.

2.2. Electric Energy Storage Model

2.3. Demand Response Model

2.3.1. Shiftable Load Model

2.3.2. Interruptible Load Model

2.3.3. Electric Vehicle Model

2.4. Constraints

- (1)

- Power interaction balance constraint of the Microgrid

- (2)

- Energy Storage Constraints

- (3)

- Demand Response Coefficient Constraints

- (4)

- Electric Vehicle Related Constraints

- (5)

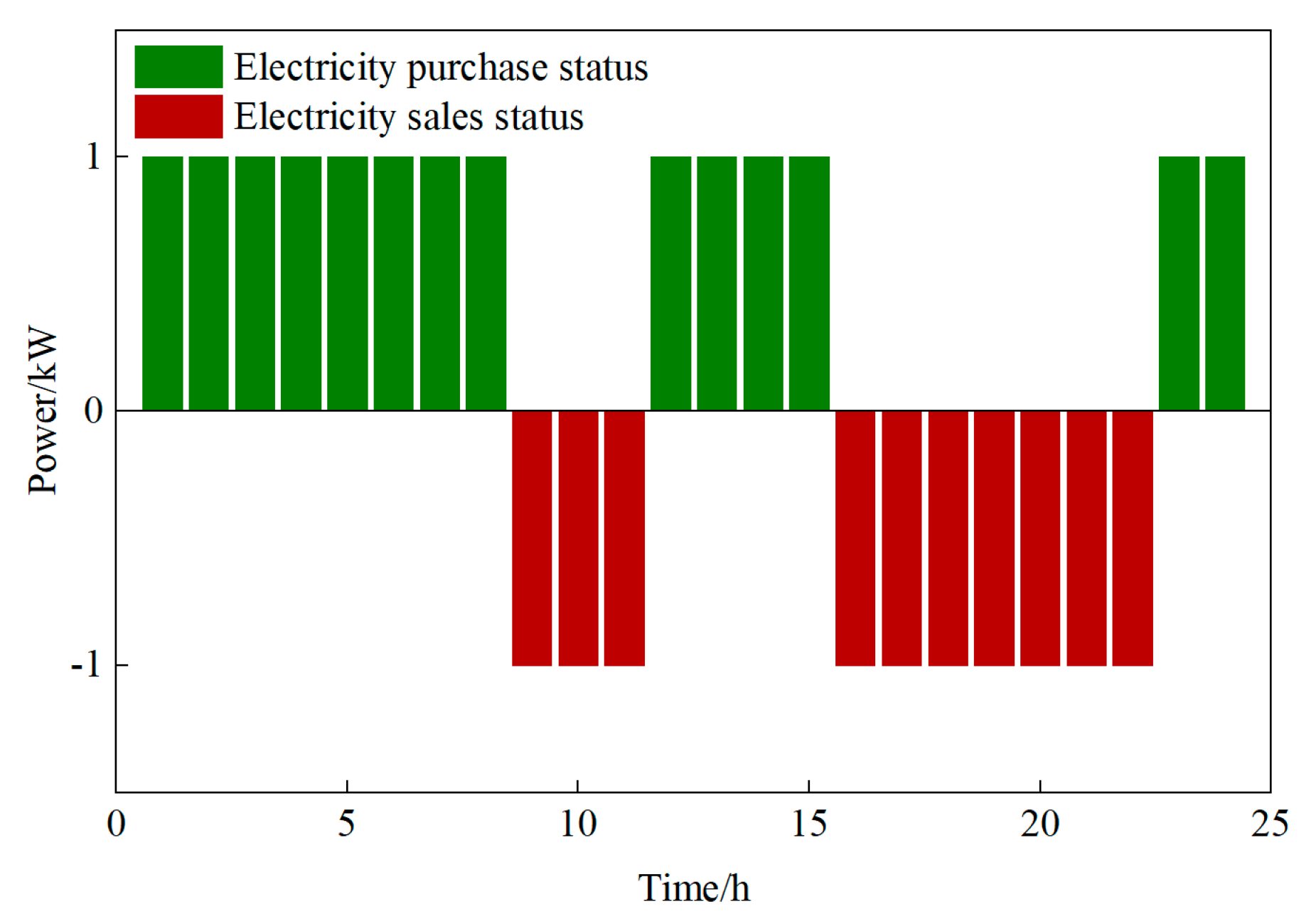

- Microgrid electricity purchase and sale constraints

2.5. Per-Unit System Normalization

3. Construction of Ambiguity Sets for Wind-Photovoltaic Generation Output and Explanation of the Distributionally Robust Optimization Model

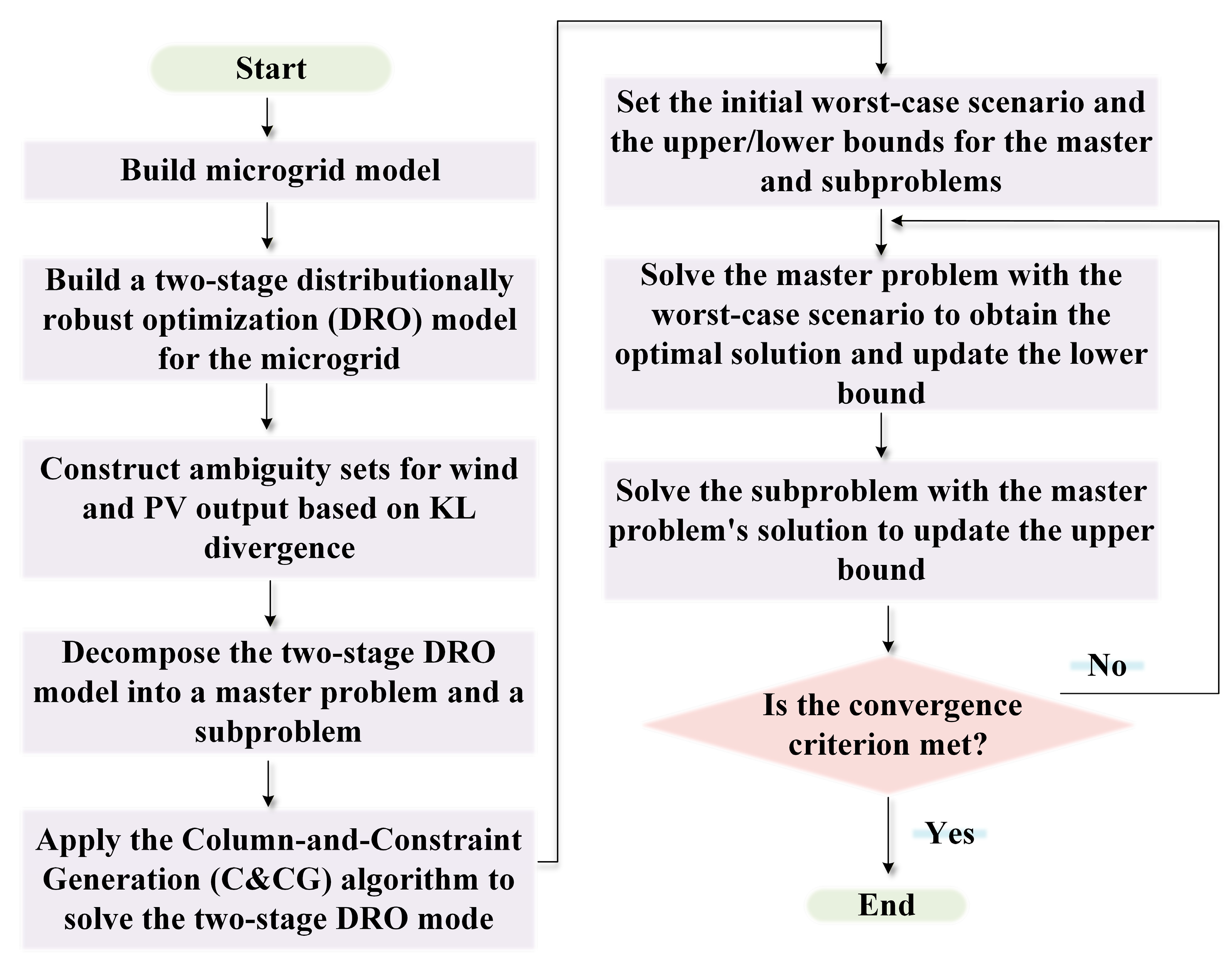

3.1. Construction of Ambiguity Sets for Wind-Photovoltaic Generation Output Based on KL Divergence

3.1.1. Motivation for KL Divergence and Comparison with Wasserstein Metric

3.1.2. Reference Distribution of Wind-Photovoltaic Generation

3.1.3. Establishing the Ambiguity Set

3.1.4. Determination of Set Distance

3.2. Solution Method for the Distributionally Robust Optimization Model

3.2.1. Master Problem

3.2.2. Subproblem

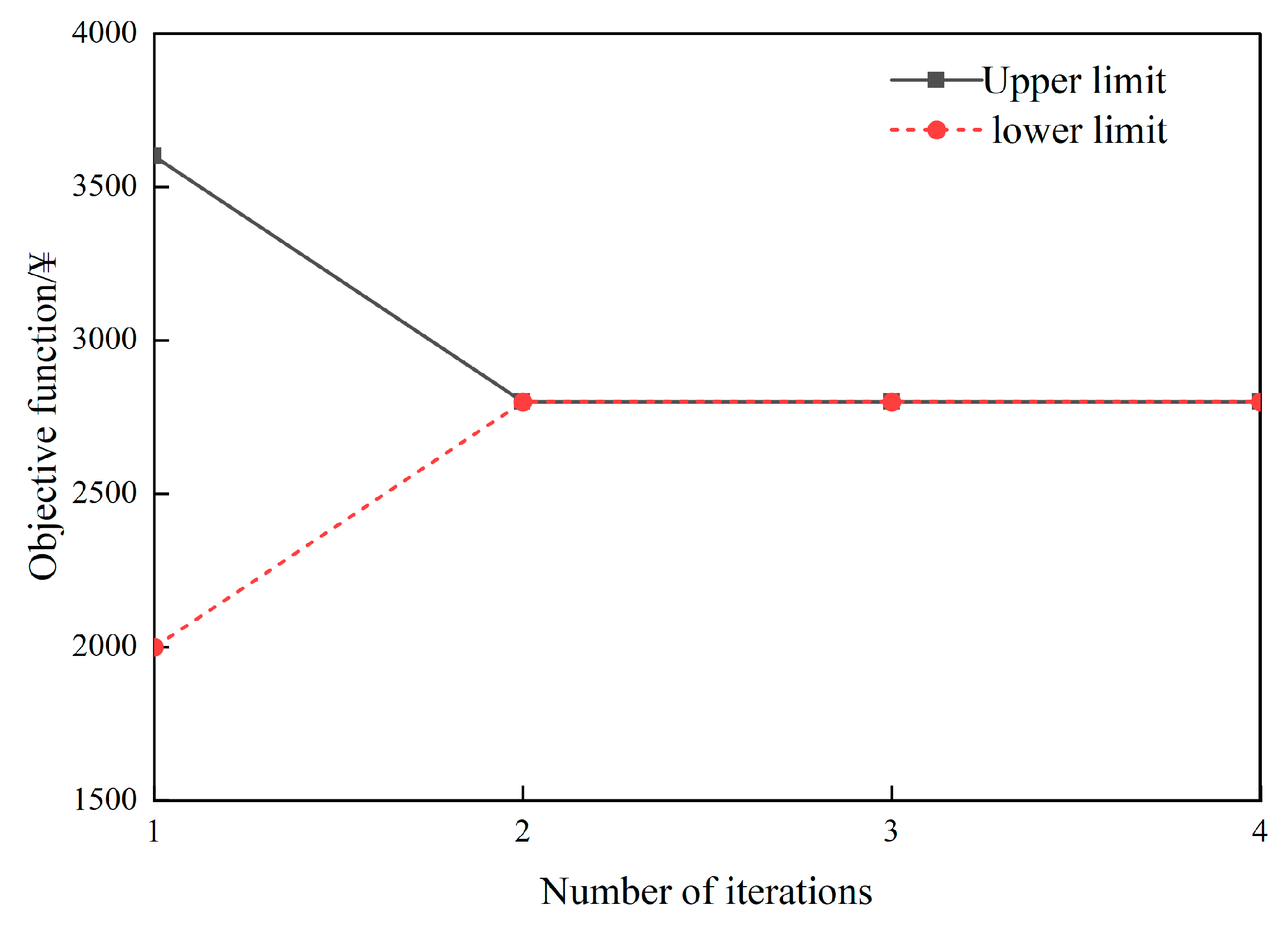

3.2.3. Solution Method Based on the C&CG Algorithm

- MP minimizes costs given a set of critical scenarios;

- SP finds the worst-case distribution for fixed first-stage decisions;

- Iteration continues until bounds converge.

4. Case Study Analysis

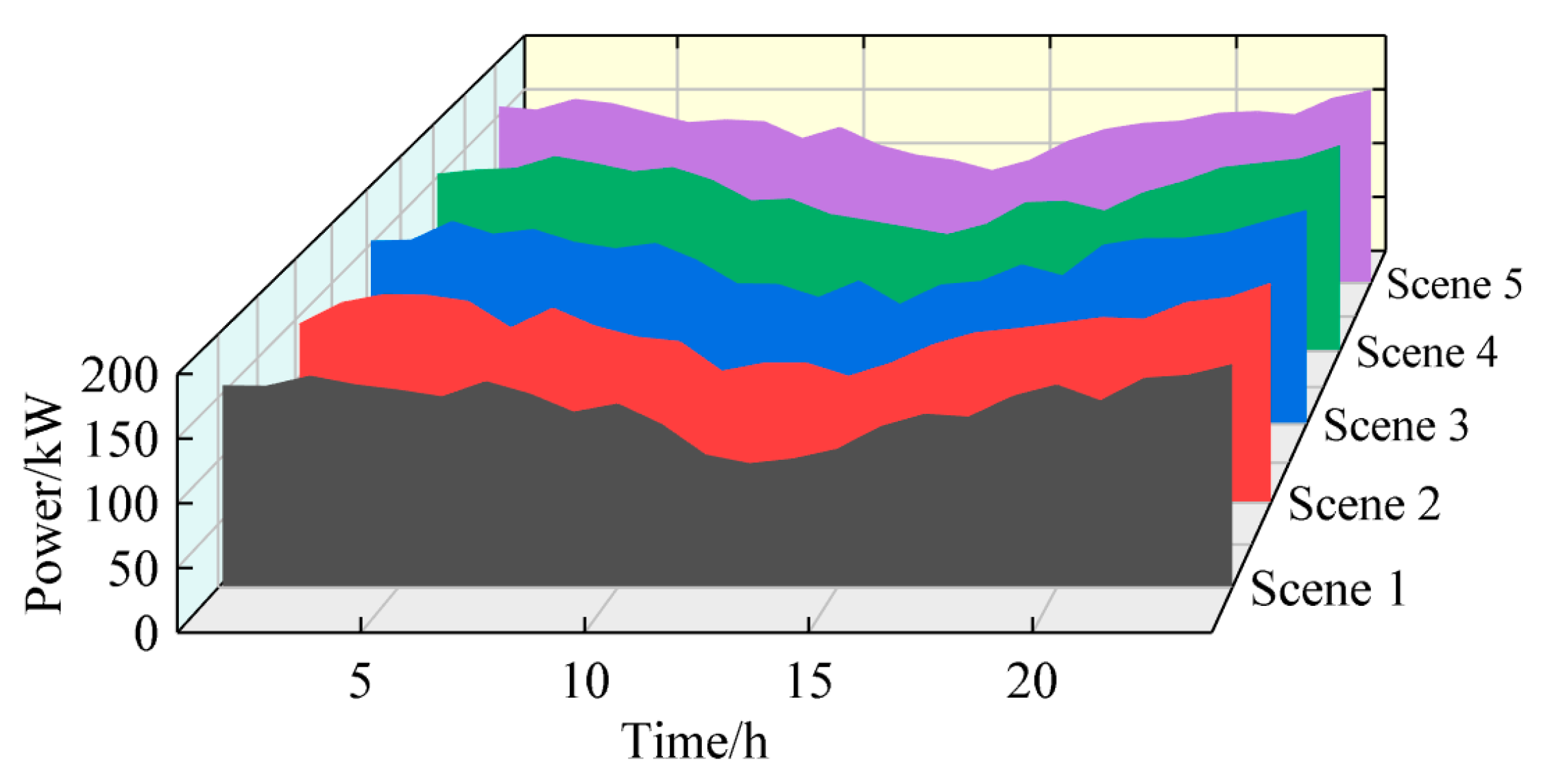

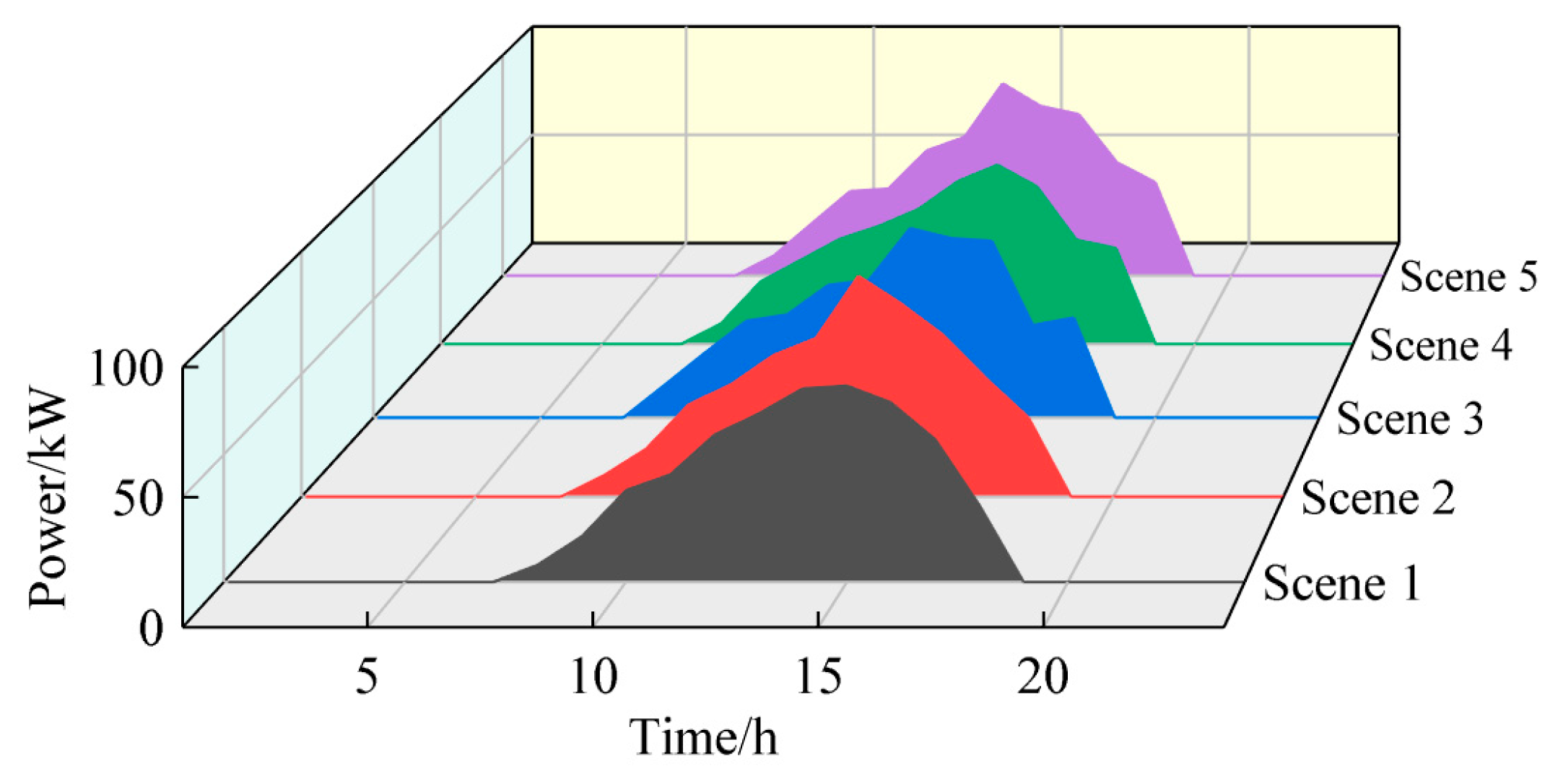

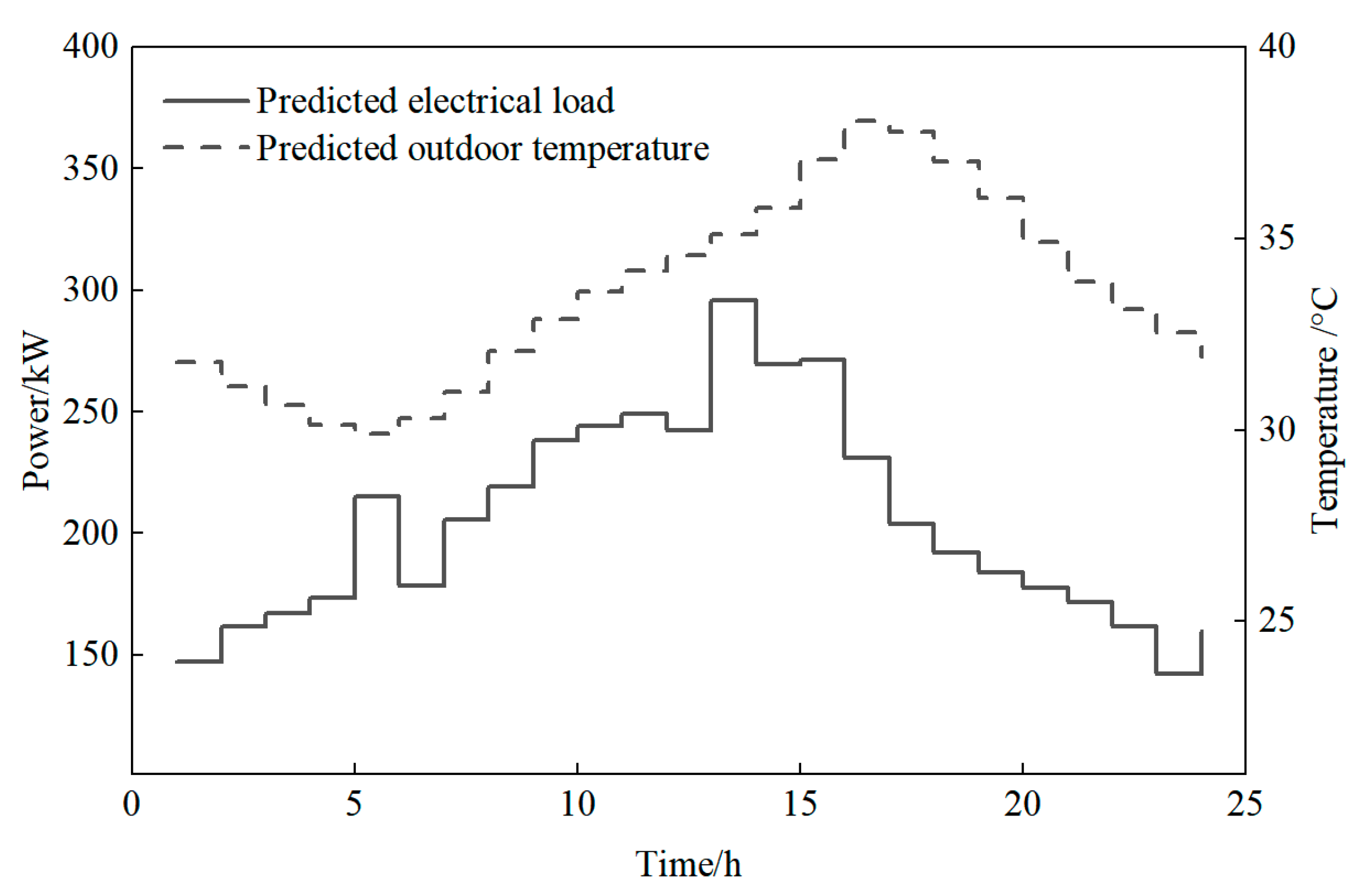

4.1. Basic Microgrid Data

- (1)

- Base Case with normal renewable generation and load;

- (2)

- High Renewable Generation with high PV/wind output;

- (3)

- Low Renewable Generation with scarce renewable availability;

- (4)

- High Load Demand representing a peak load condition;

- (5)

- EV Charging Peak with concentrated electric vehicle charging loads.

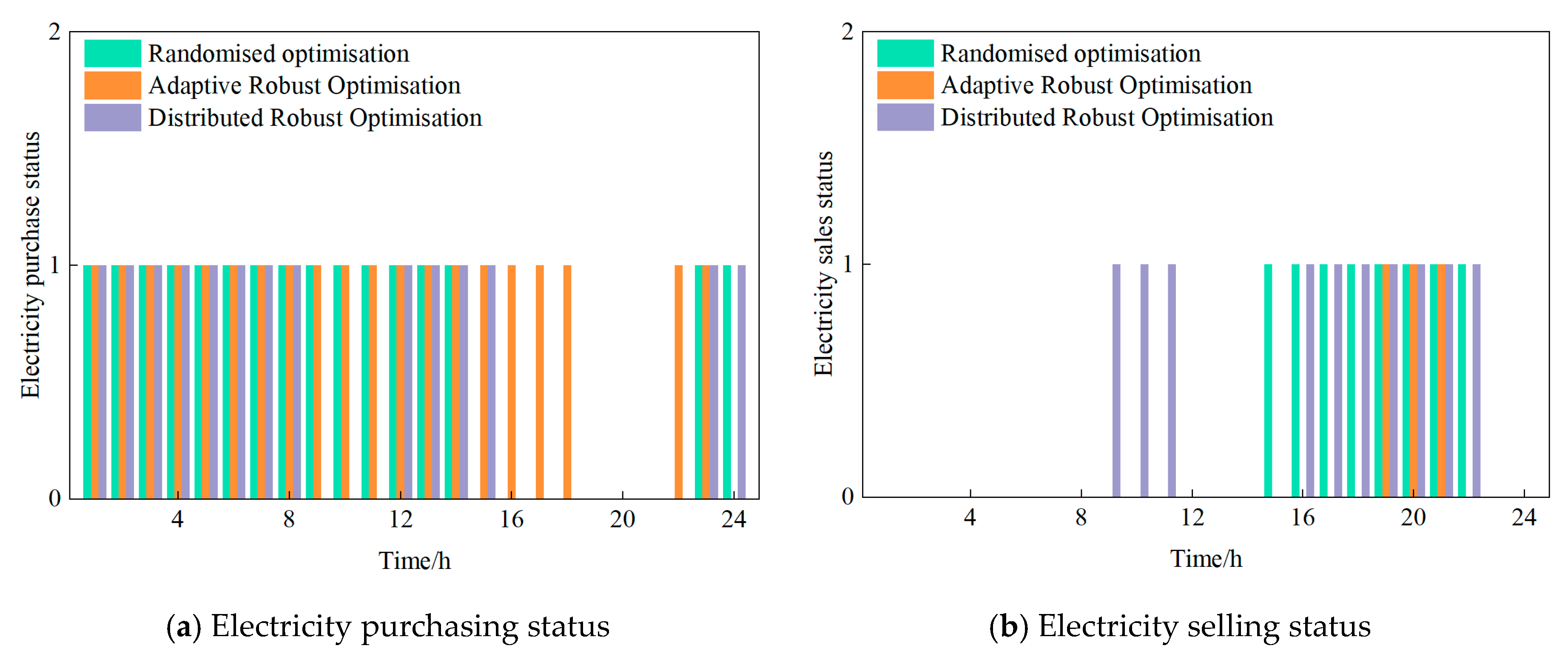

4.2. Comparison of Distributionally Robust Optimization with Other Optimization Methods

4.3. Analysis of Distributionally Robust Optimization Scheduling Results

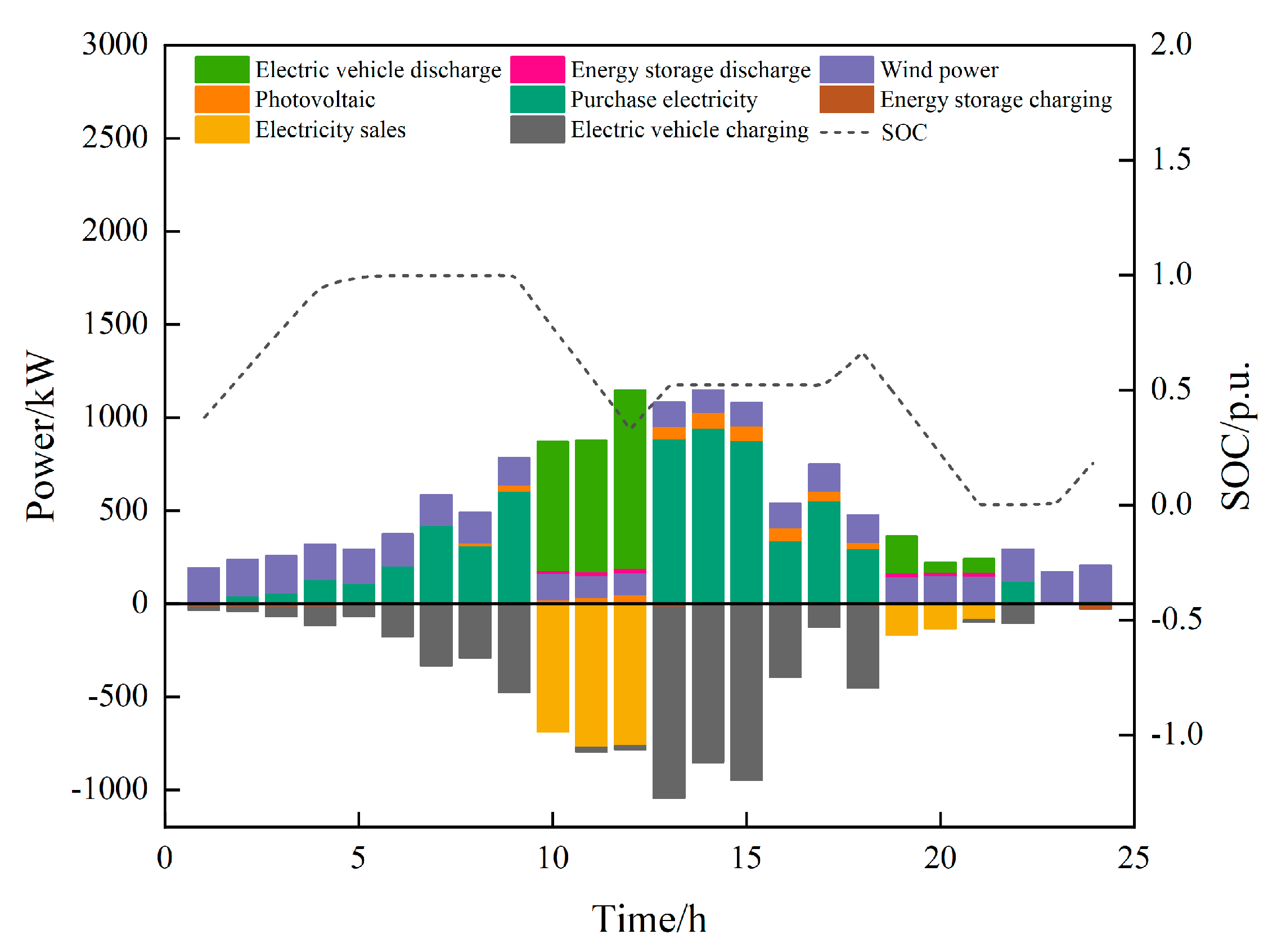

4.3.1. Analysis of Optimization Status Within the Microgrid

4.3.2. Analysis of Distributionally Robust Optimization Effects Based on KL Divergence

- (1)

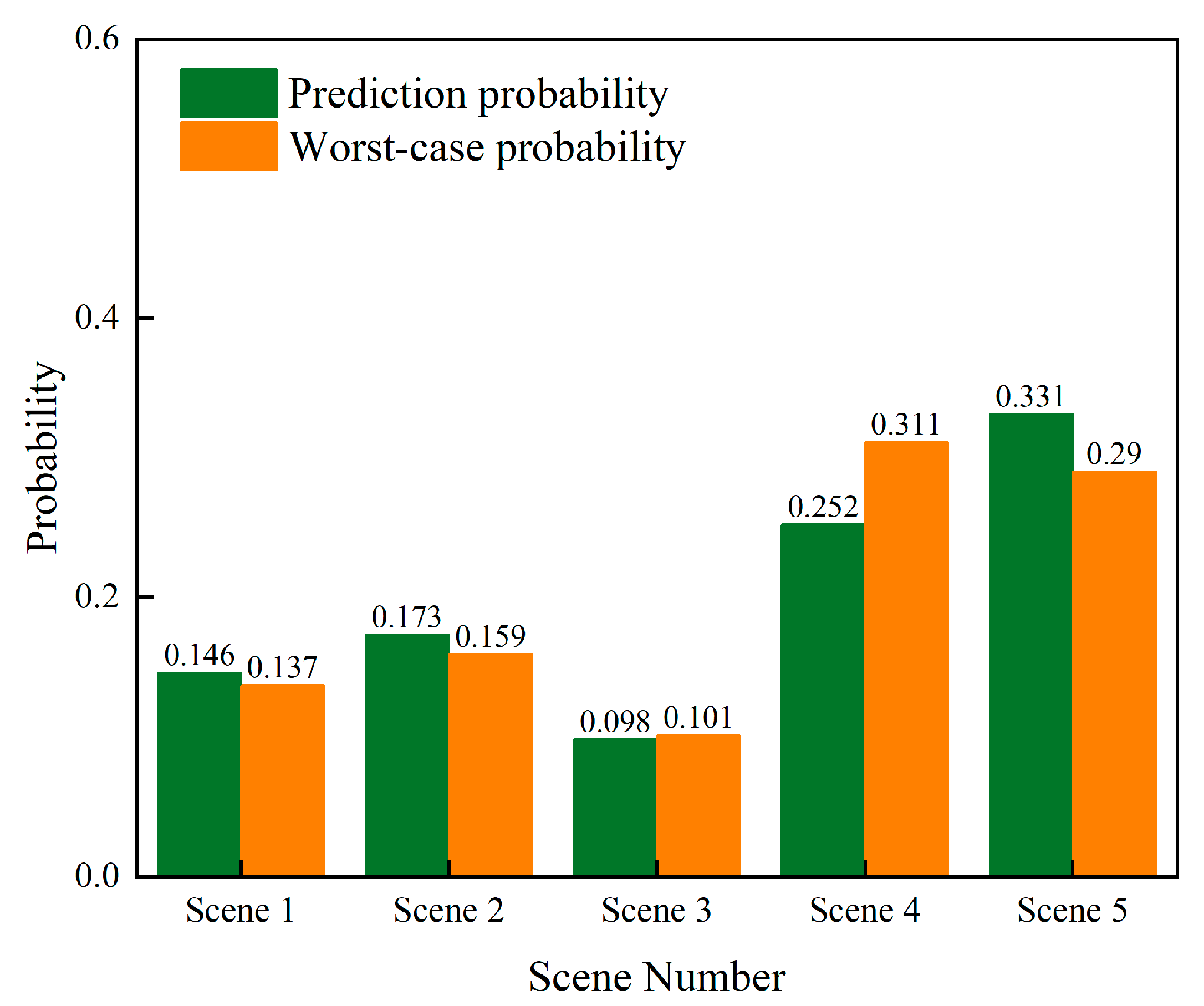

- Robustness Analysis

- (2)

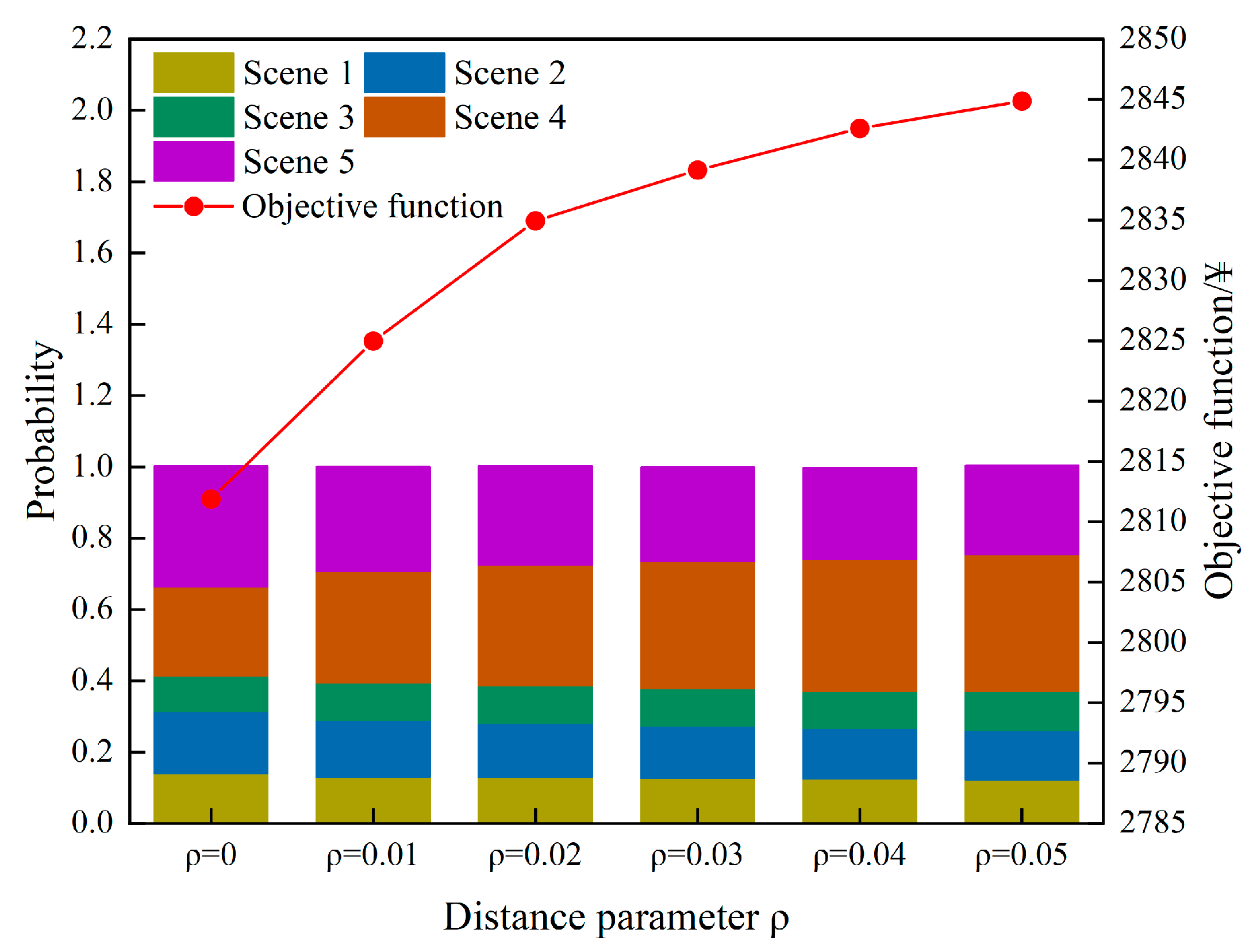

- Analysis of the Impact of Changing the KL Divergence Distance Parameter on the Optimization Results

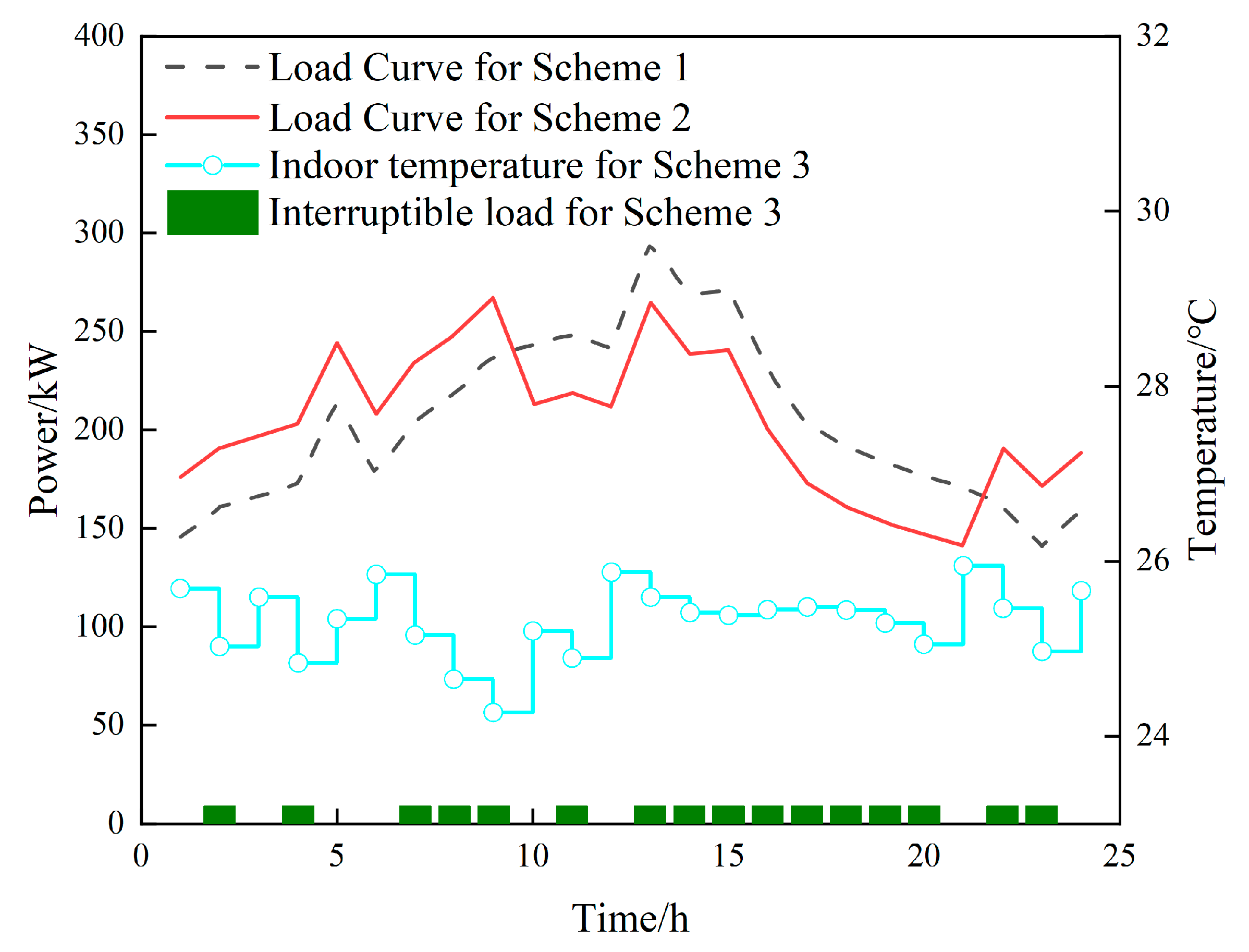

4.3.3. Optimization Effect Analysis Based on Demand Response

4.4. Algorithm Convergence Results

5. Conclusions

5.1. Discussion of Findings

- (1)

- The proposed DRO model demonstrates a superior balance between economy and robustness. It achieves a 2.86% reduction in daily operating cost compared to robust optimization, while remaining within 4.88% of the cost of stochastic optimization. This performance substantiates the model’s key advantage: by hedging against the worst-case probability distribution rather than a deterministic worst-case scenario, it effectively mitigates the over-conservatism inherent in traditional robust optimization [22], while providing greater resilience to distributional errors than stochastic optimization.

- (2)

- The model successfully integrates the merits of both stochastic and robust optimization paradigms. Central to this integration is the KL divergence parameter ρ, which provides system operators with a direct and mathematically transparent mechanism to calibrate the trade-off between conservatism and cost. An increase in ρ, indicative of greater risk aversion, shifts the probability weight towards higher-cost scenarios, thereby systematically enhancing operational robustness.The incorporation of interruptible and transferable demand response modes is confirmed as a critical driver of system efficiency. These mechanisms effectively optimize load scheduling, curtail peak demand, and consequently reduce overall scheduling costs. The efficacy of coordinating such flexible resources, including electric vehicle clusters, aligns with and reinforces the findings of prior studies [23], and is further supported by recent research on low-carbon scheduling of AC/DC microgrids [24,25], differentiated demand response [26], energy storage support [27], renewable uncertainty handling [28], and the integration of EVs [29,30,31,32], underscoring their indispensable role in future energy systems.

5.2. Limitations

5.3. Future Work

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A. Nomenclature

| Symbol | Description | Unit | Equation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sets and Indices | |||

| t | Index for time periods | - | |

| T | Total number of time periods | ||

| s | Index for scenarios | ||

| S, N | Total number of scenarios | ||

| u | Index for electric vehicle (EV) users | ||

| U | Total number of EV users | ||

| Set of time periods when EV u is available for charging/discharging | (8) | ||

| Total number of outer loop iterations | (32) | ||

| Index for outer loop iteration count | |||

| Decision Variables | |||

| x | Vector of first-stage (day-ahead) decision variables | (1) | |

| y | Vector of second-stage (real-time) decision variables | ||

| Charging (positive) or discharging (negative) power of EV user at time t | kW | (2)(8) | |

| Power purchased from the main grid in scenario s at time t | kW | (3)(9)(10)(23) | |

| Power sold to the main grid in scenario s at time t | kW | (3)(9)(10)(24) | |

| Curtailed photovoltaic power in scenario s at time t | kW | (4) | |

| Curtailed wind power in scenario s at time | kW | ||

| Charging power of the energy storage system in scenario s at time t | kW | (5)(13) | |

| Discharging power of the energy storage system in scenario s at time t | kW | (5)(14) | |

| Actual microgrid load at time t in scenario s before demand response | kW | (6)(9) | |

| Actual microgrid load at time t in scenario s after demand response | kW | ||

| Power of the air conditioner (interruptible load) at time t in scenario s | kW | (7)(9) | |

| Binary variable indicating the ON (1)/OFF (0) state of the air conditioner at time t in scenario s | - | ||

| Binary variable for energy storage charging status | - | (13)(15) | |

| Binary variable for energy storage discharging status | - | (14)(15) | |

| Binary variable for energy storage discharging status | kW | (6)(17) | |

| Auxiliary variable for demand response | kW | ||

| Binary variable for microgrid purchasing status from the primary grid | - | (23) | |

| Binary variable for microgrid selling status to the primary grid | - | (24) | |

| First-stage decision variables | - | (30) | |

| Second-stage continuous decision variables in scenario s | - | ||

| Binary (0–1) variables in the first-stage optimization model | - | ||

| Binary (0–1) variables in the second-stage optimization model | - | ||

| Auxiliary variable for linearizing the model, representing the upper bound of the subproblem cost | - | (32) | |

| Second-stage continuous decision variables in the w-th iteration, corresponding to the most critical scenario | - | ||

| Parameters | |||

| Cost coefficient for EV charging/discharging at time t | ¥/kWh | (2) | |

| Electricity purchase price from the main grid at time t | ¥/kWh | (3) | |

| Electricity sale price to the main grid at time t | ¥/kWh | ||

| Unit economic penalty coefficient for renewable energy curtailment | ¥/kWh | (4) | |

| Charging efficiency of the energy storage system | - | (5) | |

| Discharging efficiency of the energy storage system | - | ||

| Time interval | h | (5)(7)(8) | |

| Indoor temperature at time t in scenario s | °C | (7) | |

| Outdoor temperature at time t in scenario s | °C | ||

| R | Thermal resistance (insulation coefficient) of the building | °C/kW | |

| C | Thermal capacity of the building | kWh/°C | |

| State of charge (SOC) of EV u at time t | kWh | (8)(22) | |

| Charging efficiency of the electric vehicle | - | (8) | |

| Discharging efficiency of the electric vehicle | - | ||

| Photovoltaic (PV) power generation at time t in scenario s | kW | (9) | |

| Wind turbine (WT) power generation at time t in scenario s | kW | ||

| Inflexible (fixed) load demand at time t in scenario s | kW | ||

| Number of typical rooms (with air conditioners) | - | ||

| Minimum state of charge (SOC) of the energy storage system | kWh | (11) | |

| Maximum state of charge (SOC) of the energy storage system | kWh | ||

| Maximum charging power of the energy storage system | kW | (13) | |

| Maximum discharging power of the energy storage system | kW | (14) | |

| Demand response coefficient | - | (6)(16) | |

| Maximum achievable value of the demand response coefficient | - | (16) | |

| Minimum allowable indoor temperature | °C | (18) | |

| Maximum allowable indoor temperature | °C | ||

| Maximum charging power of EV user u | kW | (19) | |

| Maximum discharging power of EV user u | kW | (20) | |

| Arrival time of EV u | - | (21) | |

| Departure time of EV u | - | ||

| Minimum state of charge (SOC) of EV u | kWh | (22) | |

| Maximum state of charge (SOC) of EV u | kWh | ||

| Maximum power purchase capacity from the main grid | kW | (23) | |

| Maximum power sale capacity to the main grid | kW | (24) | |

| Total number of historical output samples | - | (25) | |

| Number of original scenarios contained within the k-th reduced-typical scenario | |||

| The set distance, indicating the similarity threshold between the reference distribution and the probability distribution P. | (28) | ||

| N | The dimension of the sample spac | (27)(29) | |

| The upper quantile of the chi-square distribution with R−1 degrees of freedom at confidence level α | (29) | ||

| Coefficient vector of the first-stage decision variables in the objective function | (30) | ||

| Coefficient vector of the second-stage decision variables in the objective function | |||

| Coefficient matrix of the first-stage constraints | |||

| Coefficient matrix of the second-stage continuous variables in the constraints | |||

| Coefficient matrix of the second-stage integer variables in the constraints | |||

| Right-hand side constant vector of the constraints | |||

| Prescribed convergence tolerance error threshold for the outer loop | kWh | (32) | |

| Other Symbols | |||

| Total operating cost objective function | ¥ | (1) | |

| Total cost of electric vehicle charging and discharging | ¥ | ||

| Cost of power exchange with the main grid in scenario s | ¥ | ||

| Penalty cost for renewable curtailment in scenario s | ¥ | ||

| Probability of scenario s occurring | - | ||

| Ambiguity set of probability distributions | - | ||

| State of charge (SOC) of the energy storage system at time t in scenario s | kWh | (5)(11)(12) | |

| Net power exchange of the microgrid with the main grid | kW | (10) | |

| Reference distribution of wind-photovoltaic generation | - | (26) | |

| Probability of the k-th typical scenario after reduction | (25) | ||

| The ambiguity set of uncertainty constructed based on KL divergence. | (28) | ||

| The value of the probability distribution function P at the sample point n | (27) | ||

| The value of the reference distribution function at the sample point n | |||

| (Uncertain) probability of occurrence for scenario s | (30) | ||

| Lower bound of the original problem obtained by solving the master problem. | (33) | ||

| Upper bound of the original problem obtained by solving the subproblem. | |||

References

- Ye, X.; Wang, C.; Shi, Z. Analysis of High Proportion Renewable Energy Integration Abroad and Recommendations for Sustainable Development of New Energy in China. China Electr. Power 2025, 58, 137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Georgia, K.; Szábo, S.; Jäger-Waldau, A. Powering Up to Cool Down Climate Change: Tripling Renewable Energy to Meet COP28 Pledge in the EU. In Proceedings of the 2024 IEEE 52nd Photovoltaic Specialist Conference (PVSC), Seattle, WA, USA, 9–14 June 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Wu, Y.; Li, X. Microgrid Islanded Operation Strategy Supported by Aggregated Charging and Discharging of Electric Vehicles. Mod. Electr. Power 2025, 42, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zuo, J.; Zhong, Y.; Bao, B. Multi-Objective Optimization Model for Power Grid Operation Scheduling Considering the Uncertainty of New Energy. Grid Clean Energy 2025, 41, 152–158. Available online: https://epjournal.csee.org.cn/zh/article/129939526/ (accessed on 28 November 2025).

- Chen, M.; Geng, J.; Zhao, Y. Weekly Operation Strategy of Electric-Hydrogen Coupled Microgrid Based on Two-stage Stochastic Optimization. China Electr. Power 2024, 58, 82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, B.; Han, X.; Li, W. Multi-timescale stochastic optimization scheduling strategy for AC-DC hybrid microgrids incorporating multi-scenario analysis. High Volt. Eng. 2020, 46, 2359–2369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, H. Research on Optimal Scheduling of Multi-Form Microgrid Clusters Considering Uncertainty Under the New Power System. Ph.D. Theis, North China Electric Power University, Beijing, China, 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Wu, R.; Yao, X. Joint Bidding Strategy of Compressed Air Energy Storage and Wind Power Based on Stochastic Dual Dynamic Integer Programming. South. Power Grid Technol. 2024, 18, 127–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Y. Research on Low-Carbon Economic Dispatch of Microgrids Based on Robust Optimization. Ph.D. Thesis, Taiyuan University of Technology, Taiyuan, China, 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Lou, G.; Ji, L.; Wang, P.; Jing, X.; Huang, J. Adaptive Two-Stage Robust Optimization Scheduling Method for Wind-Solar-Storage Based on the i-C&CG Algorithm. J. Electr. Power Sci. Technol. 2025, 40, 141–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Guo, L.; Wang, C. Two-stage robust optimization economic dispatch method for microgrid. Proc. Chin. Soc. Electr. Eng. 2018, 38, 4013–4022+4307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Hou, H.; Zhao, B.; Zhang, L.; Shi, Y.; Xie, C. Risk-averse stochastic capacity planning and P2P trading collaborative optimization for multi-energy microgrids considering carbon emission limitations: An asymmetric Nash bargaining approach. Appl. Energy 2024, 357, 122505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Wang, Z.; Li, Z.; Yang, M.; Cheng, X. Distributed optimization for network-constrained peer-to-peer energy trading among multiple microgrids under uncertainty. Int. J. Electr. Power Energy Syst. 2023, 149, 109065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, Y.; Zhai, J.; Kang, Z.; Zhao, B.; Gao, X.; Li, Z. Distributionally robust chance-constrained energy management for island DC microgrid with offshore wind power hydrogen production. Energy 2025, 316, 134570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y. Distributionally Robust Low-carbon Economic Optimal Scheduling for Integrated Energy Microgrid. Ph.D. Thesis, Hunan University, Changsha, China, 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, L.; Tang, Z.; Huang, X. Bilevel Dynamic Distribution Network Reconfiguration Considering Uncertainties of Distributed Generation and Electric Vehicles. Electr. Power Syst. Prot. Control. 2020, 48, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, S.; He, Y.; Dai, Z. Modeling of Temporal Correlation Polyhedral Uncertainty of Wind Power and Robust Unit Commitment Optimization. Acta Energiae Solaris Sin. 2020, 41, 293–301. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, X.; Kuang, Y.; Zhou, L. Collaborative Optimal Scheduling of Active Distribution Network and Multiple Microgrids Considering Wind and Solar Uncertainties. Water Resour. Hydropower Technol. 2025, 1–10. Available online: https://link.cnki.net/urlid/10.1746.tv.20250417.1730.002 (accessed on 28 November 2025).

- Lu, J.; Huang, D.; Ren, H. Data-driven source-load robust optimal scheduling of integrated energy production unit including hydrogen energy coupling. Glob. Energy Interconnect. 2023, 6, 375–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, Y.; Yin, Z.; Zhang, Y.; Zhu, R. Distributed collaborative scheduling of multiple microgrids based on distributionally robust non-zero-sum games. J. Electr. Power Syst. Autom. 2025, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, X.; Bao, Z.; Yu, M.; Guo, C.; Guo, Y.; Wang, J. Distributionally robust multi-stage planning of integrated energy systems for industrial parks considering source and load uncertainties. Power Constr. 2025, 46, 99–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, M.; Wu, Y.; Li, Y. Day-Ahead Economic Operation Model and Solution Method for Microgrids Based on Distributionally Robust Optimization. Proc. Chin. Soc. Electr. Eng. 2022, 34, 81–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ge, L.; Fan, Y.; Lai, J.; Sun, H.; Zhang, Y. Artificial Intelligence-Enabled Microgrid Optimal Operation Technology for a Low-Carbon Economy. High Volt. Technol. 2023, 49, 2219–2238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, X.; Zhang, W.; Zou, W.; Li, B.; Chen, X. Low-Carbon Optimal Scheduling of AC-DC Hybrid Microgrids Considering Green Certificate Trading and Carbon Emission Constraints. Intell. Power 2025, 53, 9–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Chen, Y.; Li, H.; Liu, L.; Huang, J.; Guo, P. Two-Stage Robust Optimization Low-Carbon Economic Dispatch of Electric-Thermal Integrated Energy Systems Considering Carbon Trading. Power Constr. 2024, 45, 58–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, C.; Zhang, J.; Chen, L. Coordinated Optimal Scheduling of Microgrid Sources, Loads, and Storage Considering Differentiated Demand Response. Electr. Power Autom. Equip. 2020, 40, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, Z.; Li, L.; Yang, P. Microgrid Optimal Scheduling Strategy Considering Networked Energy Storage Support Capability. China Electr. Power 2025, 58, 103–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, X.; Liu, J.; Zhao, D. Multi-Energy Microgrid Scheduling Optimization Model Based on Renewable Energy Uncertainty. Science. Technol. Eng. 2020, 20, 14523–14532. [Google Scholar]

- Rezaei, N.; Khazali, A.; Mazidi, M.; Ahmadi, A. Economic energy and reserve management of renewable-based microgrids in the presence of electric vehicle aggregators: A robust optimization approach. Energy 2020, 201, 117629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuang, H.; Xu, Y.; Li, Z. Microgrid Optimal Scheduling Including Electric Vehicles Based on an Improved Scarab Optimization Algorithm. Power Sci. Eng. 2024, 40, 10–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, C.; Zhang, K.; Feng, J. Hierarchical Optimal Scheduling of an Independent Wind/Solar/Diesel Microgrid Incorporating Electric Vehicle Charging Stations. J. Tianjin Univ. Technol. 2022, 41, 61–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, Y.; Yin, L.; Xu, G. Multi-objective Optimization of Combined Cooling, Heating, and Power Microgrid Based on Incentive Demand Response. South. Power Grid Technol. 2025, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Decision Stage | Category | Decision Variables | Symbol |

|---|---|---|---|

| Stage1 (Day-ahead) | Microgrid Trading | Power purchased from the main grid | |

| Power is sold to the main grid. | |||

| Energy Storage | Charging power | ||

| Discharging power | |||

| Electric Vehicle Fleet | Aggregate charging power | ||

| Aggregate discharging power | |||

| Stage2 (Real-time) | Unit Dispatch & Balancing | Realized PV power curtailment | |

| Realized wind power curtailment | |||

| Actual charging power of energy storage (adjustment) | |||

| Actual discharging power of energy storage (adjustment) |

| Parameter | Value | Parameter | Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| 0.3 | , | 0.95, 0.90 | |

| , | 0.3, 0.3 | , | 100, 0 |

| /°C | 18 | (p.u.) | 0.2 |

| /(kW·h·(°C)−1) | 0.525 | , /kW | 500, 500 |

| , /°C | 26.24 | /°C | 25 |

| 0.01 | 6 | ||

| , /kW | 20, 20 | , | 0.98, 0.98 |

| Time Period | Electricity Purchase Price/(yuan/kWh) | Electricity Sale Price/(yuan/kWh) |

|---|---|---|

| 00:00–07:00 | 0.43405 | 0.33405 |

| 08:00–22:00 | 0.78405 | 0.68405 |

| 12:00–15:00 | 0.63405 | 0.53405 |

| 16:00–18:00 | 0.78405 | 0.68405 |

| 19:00–22:00 | 0.88405 | 0.78405 |

| 23:00–24:00 | 0.43405 | 0.33405 |

| Model | Single-Day Operating Cost/¥ |

|---|---|

| Stochastic optimization | 2688.92 |

| Robust optimization | 2903.47 |

| Distributionally robust optimization | 2820.38 |

| Scheme Number | Single-Day Operating Cost/¥ |

|---|---|

| Scheme 1 | 2886.58 |

| Scheme 2 | 2799.78 |

| Scheme 3 | 2820.38 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Pan, P.; Yang, W.; Li, Z. Robust Optimal Dispatch of Microgrid Considering Flexible Demand-Side. Energies 2025, 18, 6516. https://doi.org/10.3390/en18246516

Pan P, Yang W, Li Z. Robust Optimal Dispatch of Microgrid Considering Flexible Demand-Side. Energies. 2025; 18(24):6516. https://doi.org/10.3390/en18246516

Chicago/Turabian StylePan, Pengcheng, Wenjie Yang, and Zhongkun Li. 2025. "Robust Optimal Dispatch of Microgrid Considering Flexible Demand-Side" Energies 18, no. 24: 6516. https://doi.org/10.3390/en18246516

APA StylePan, P., Yang, W., & Li, Z. (2025). Robust Optimal Dispatch of Microgrid Considering Flexible Demand-Side. Energies, 18(24), 6516. https://doi.org/10.3390/en18246516