Analysis of Useful Energy Demand for Heating Purposes in a Building with a Self-Supporting Polystyrene Structure in a Temperate Climate

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

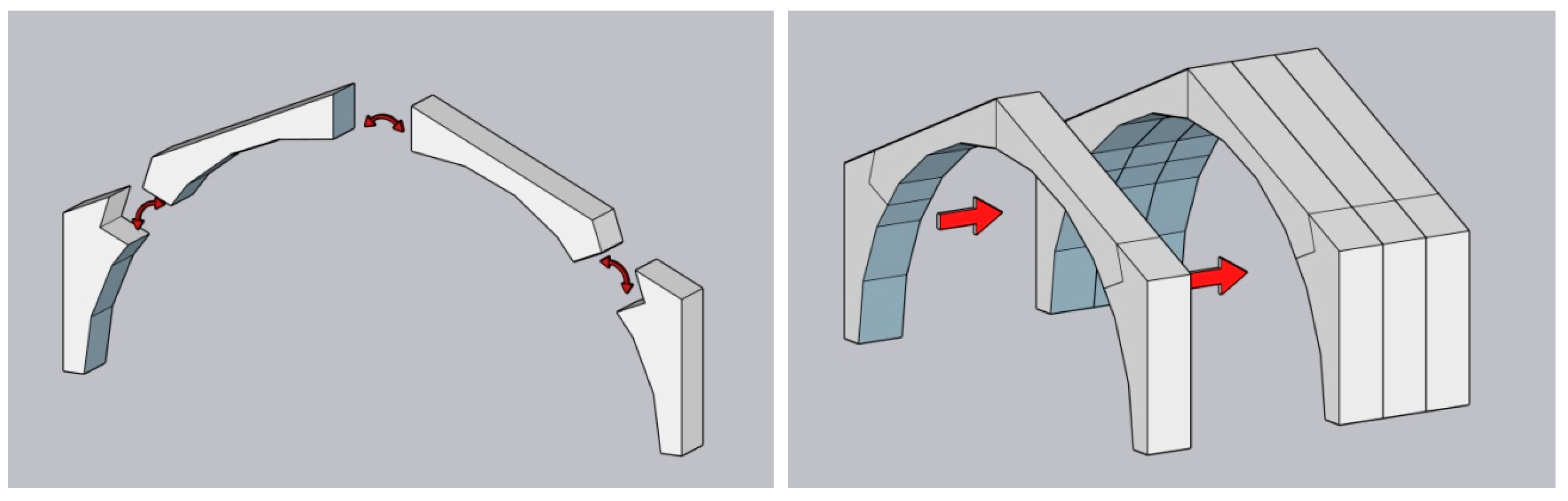

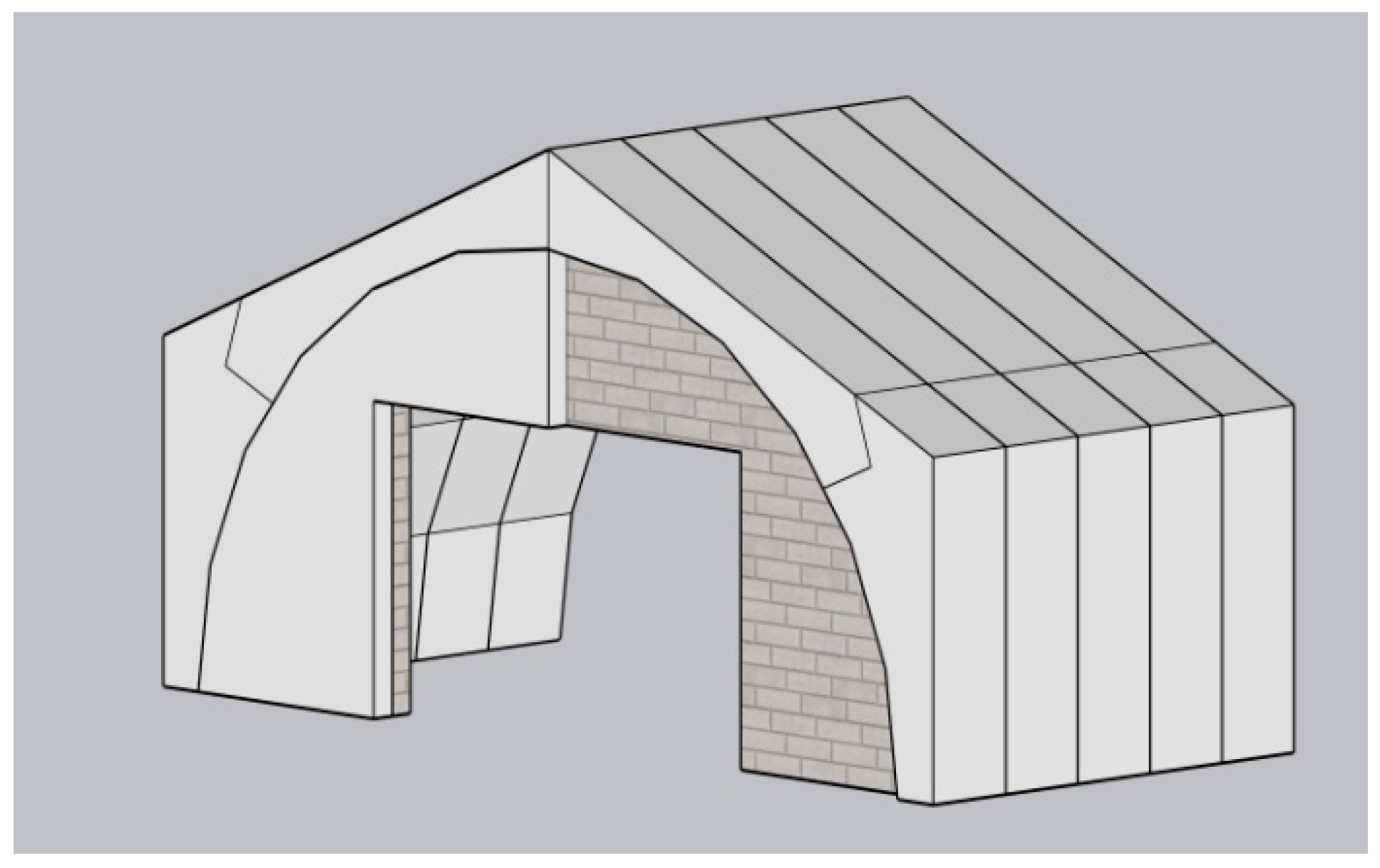

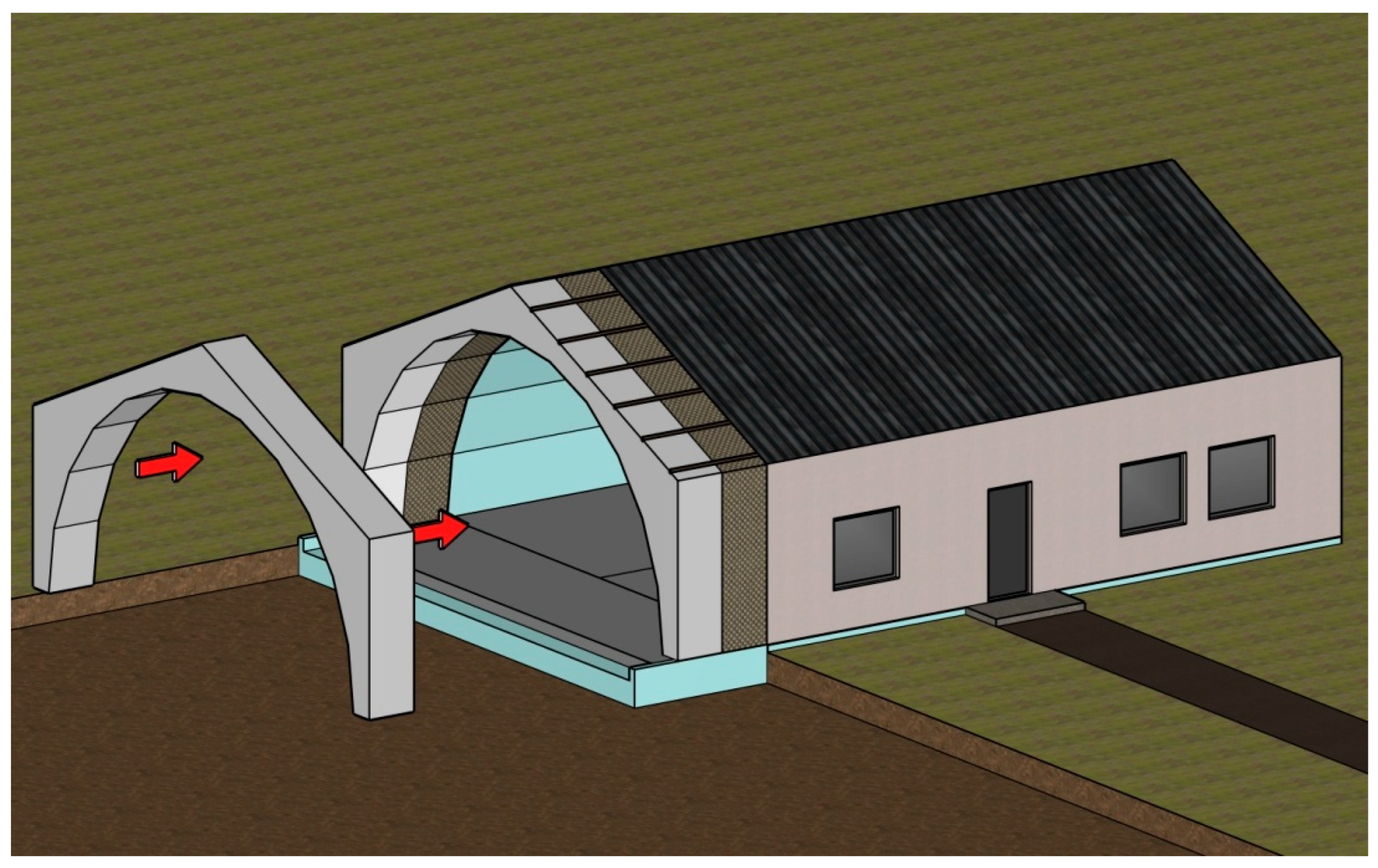

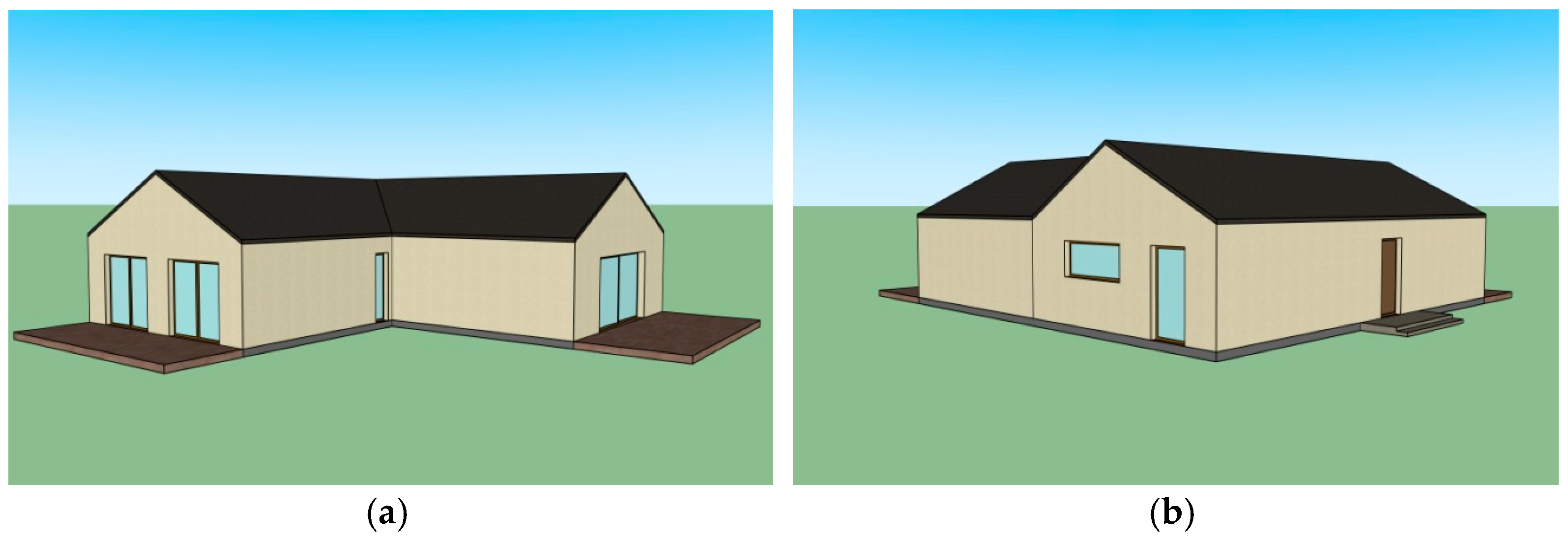

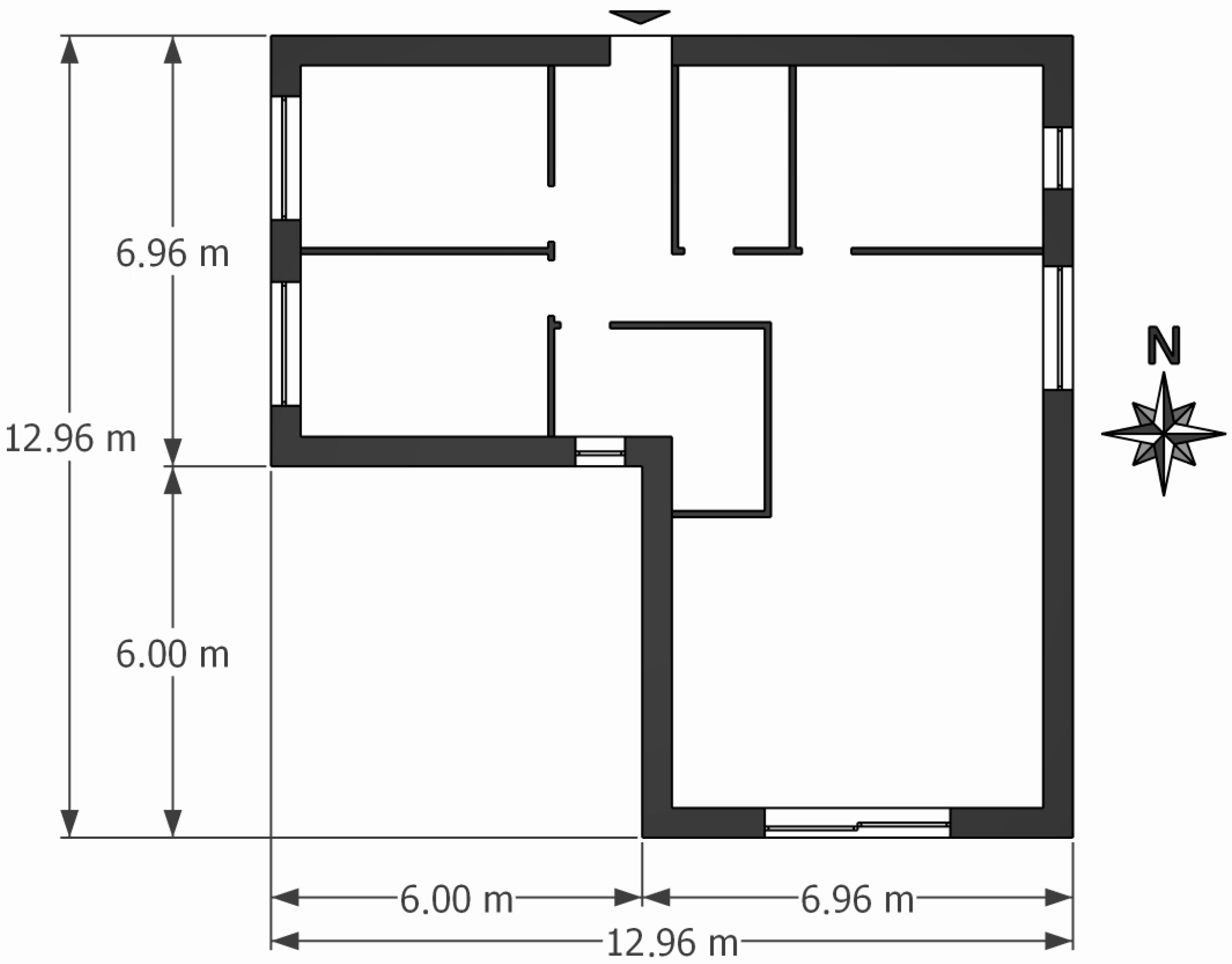

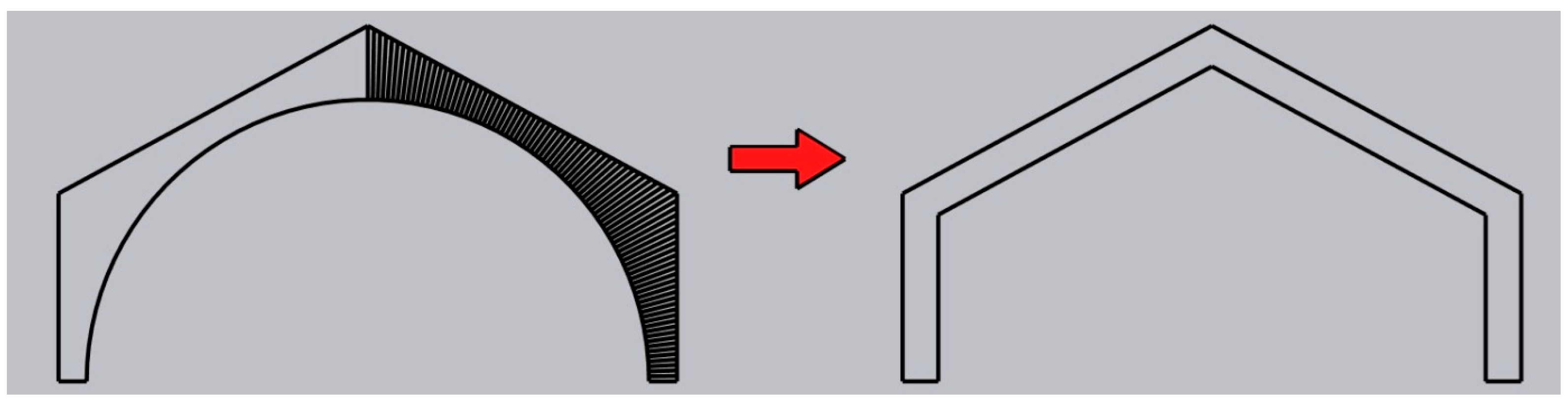

2.1. Research Object

2.2. Assumptions for Calculations

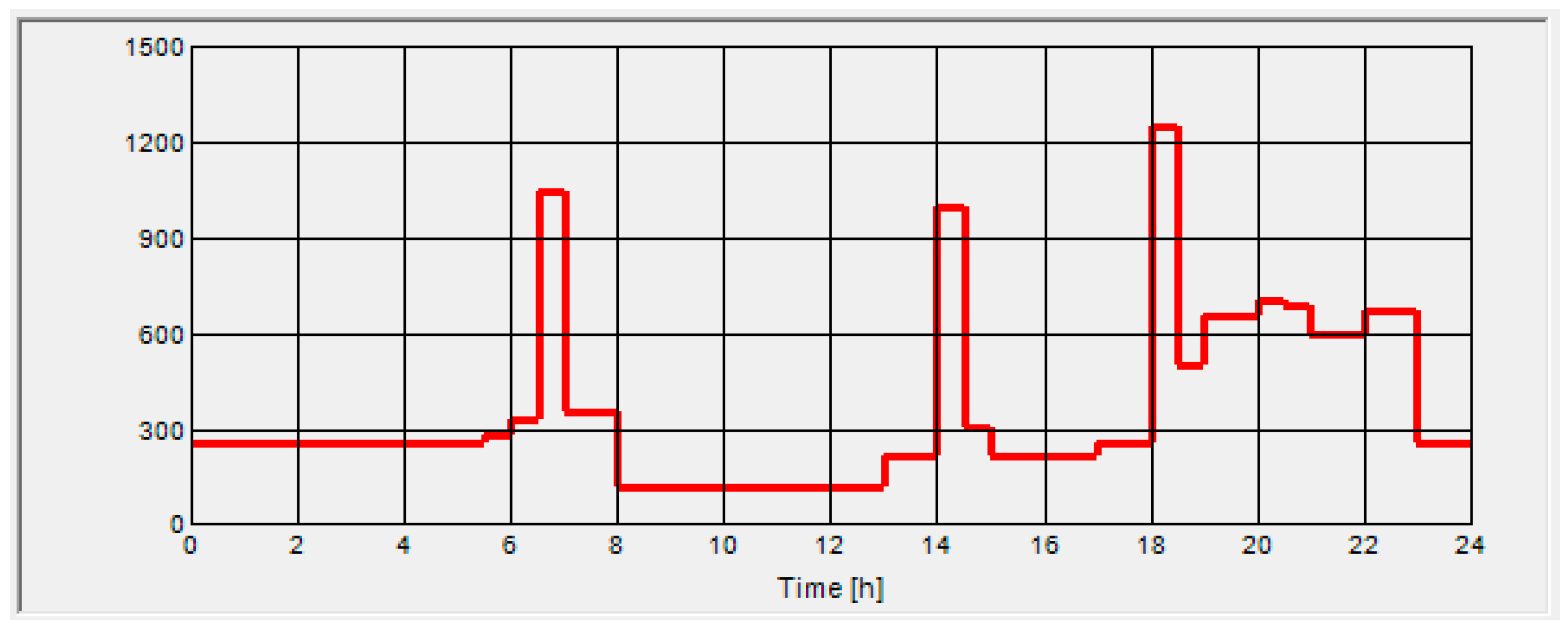

2.3. Indoor Climate

2.4. Outdoor Climate

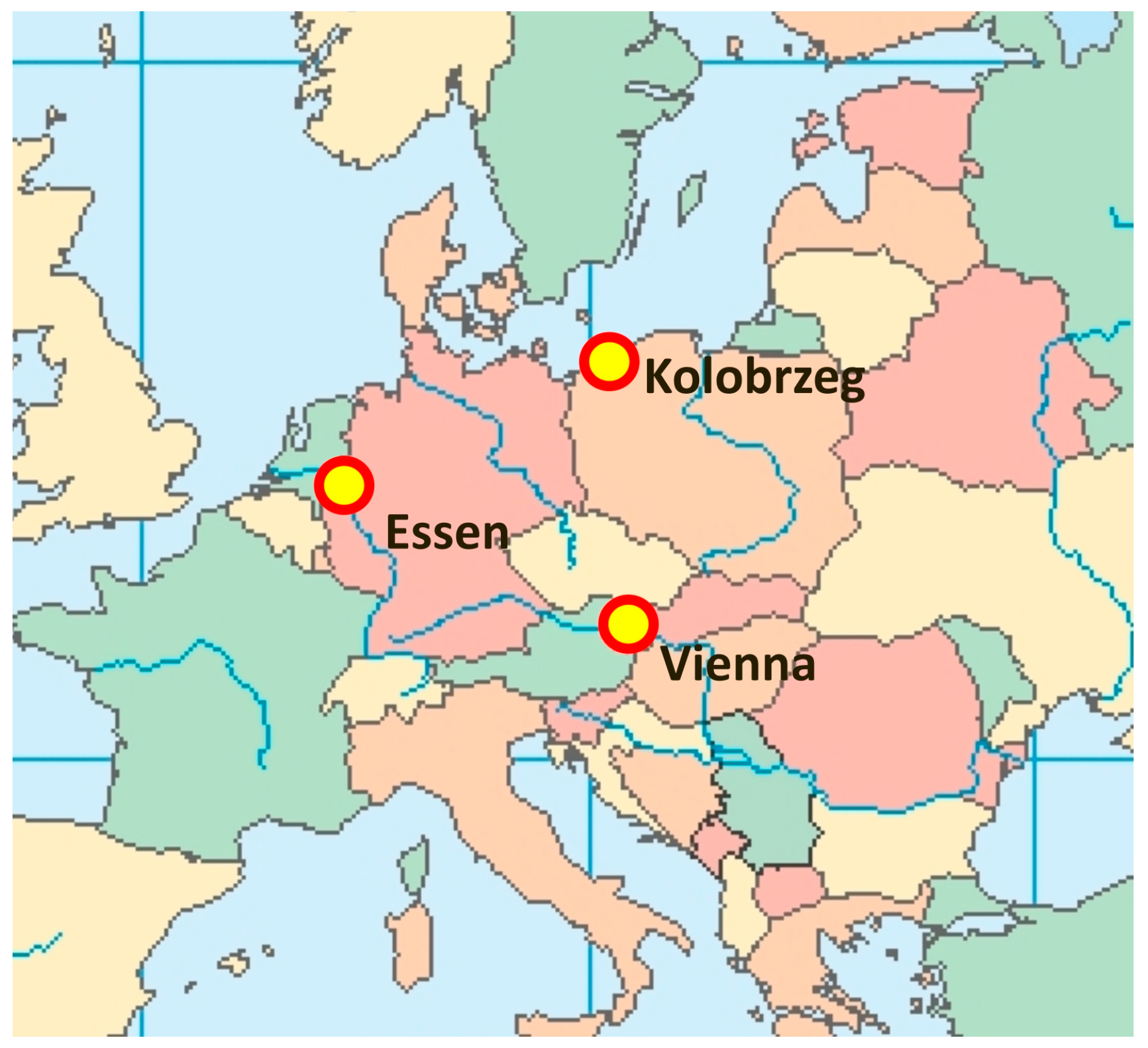

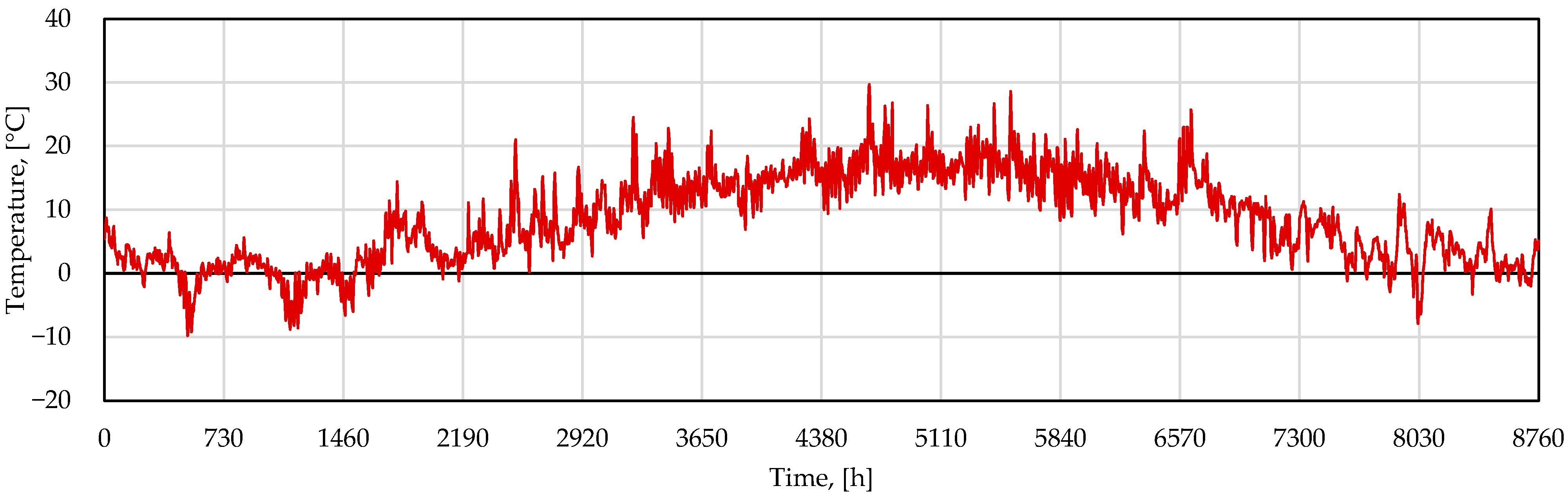

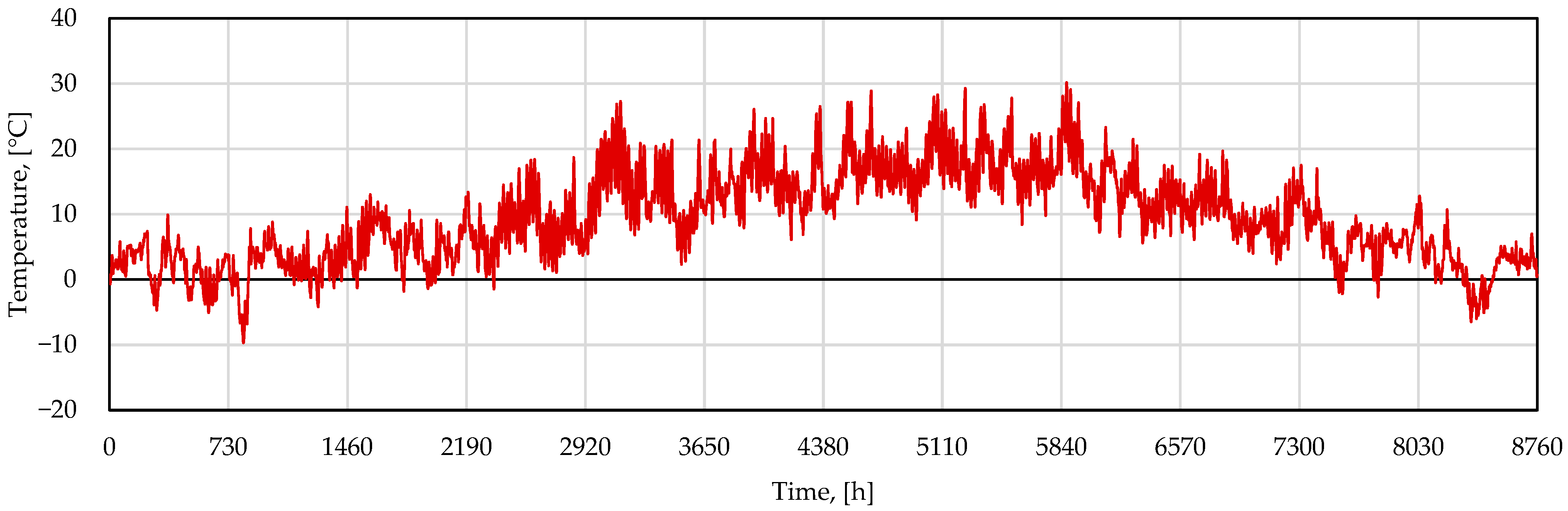

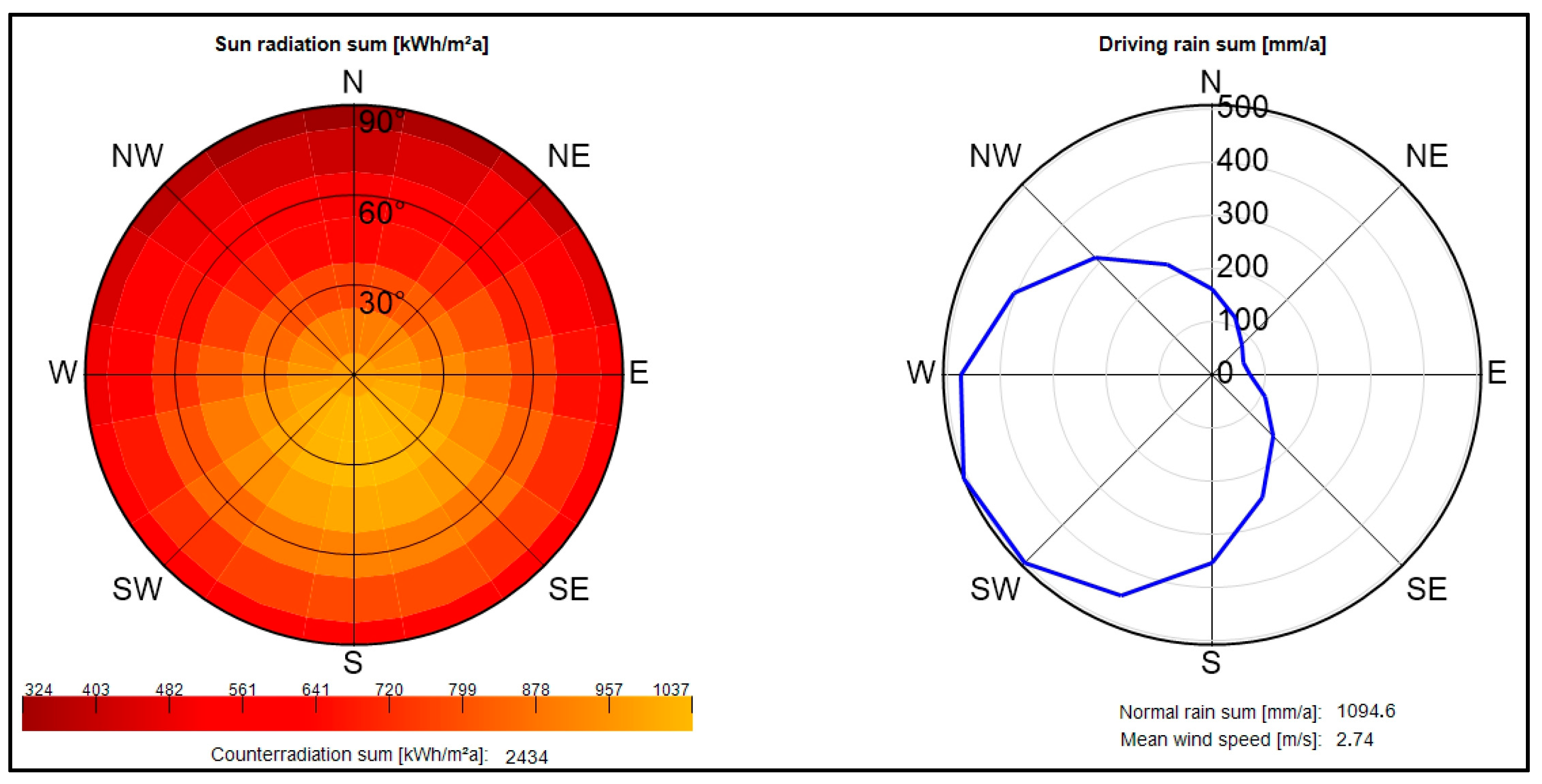

2.5. Kołobrzeg

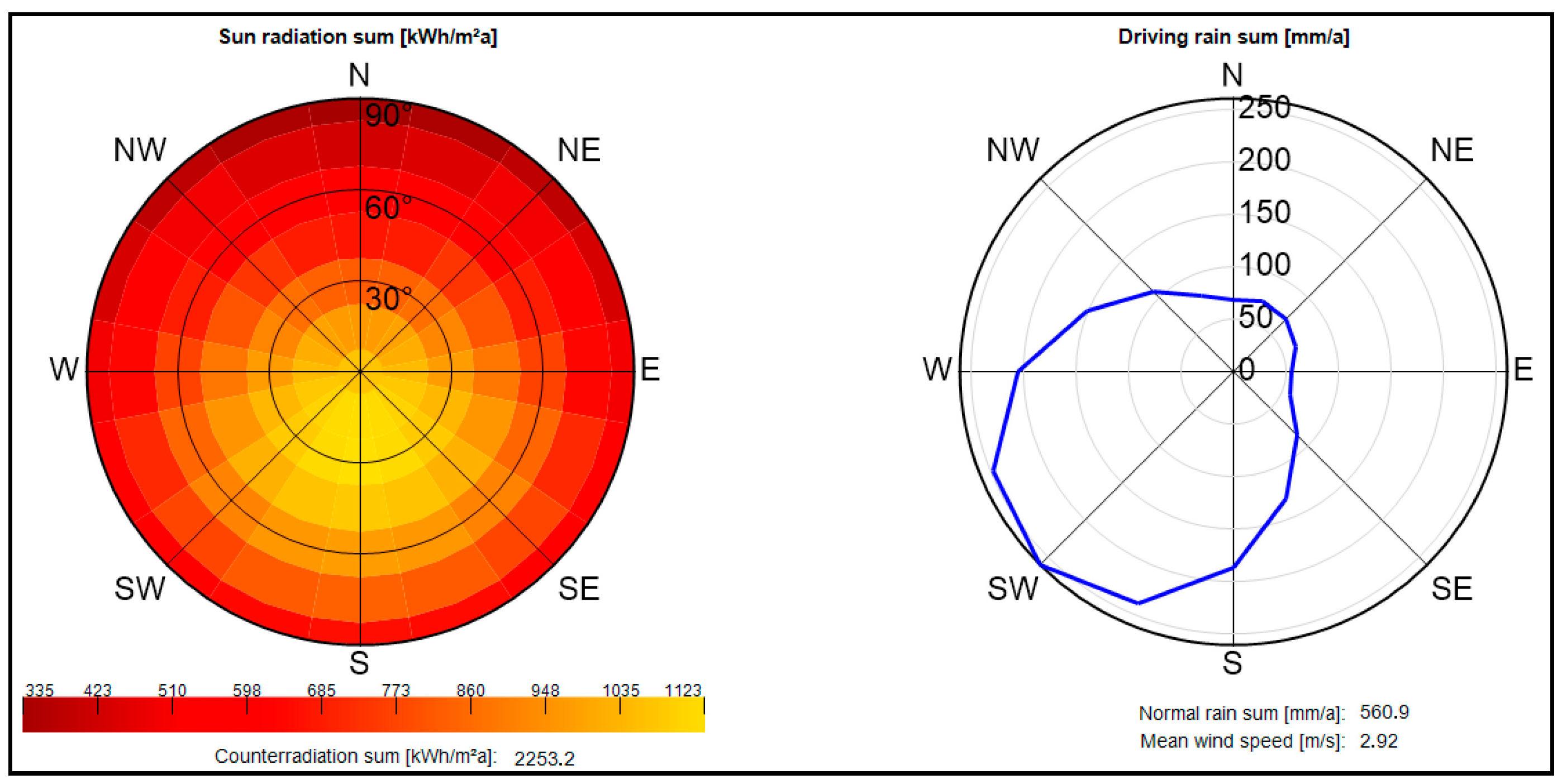

2.6. Vienna

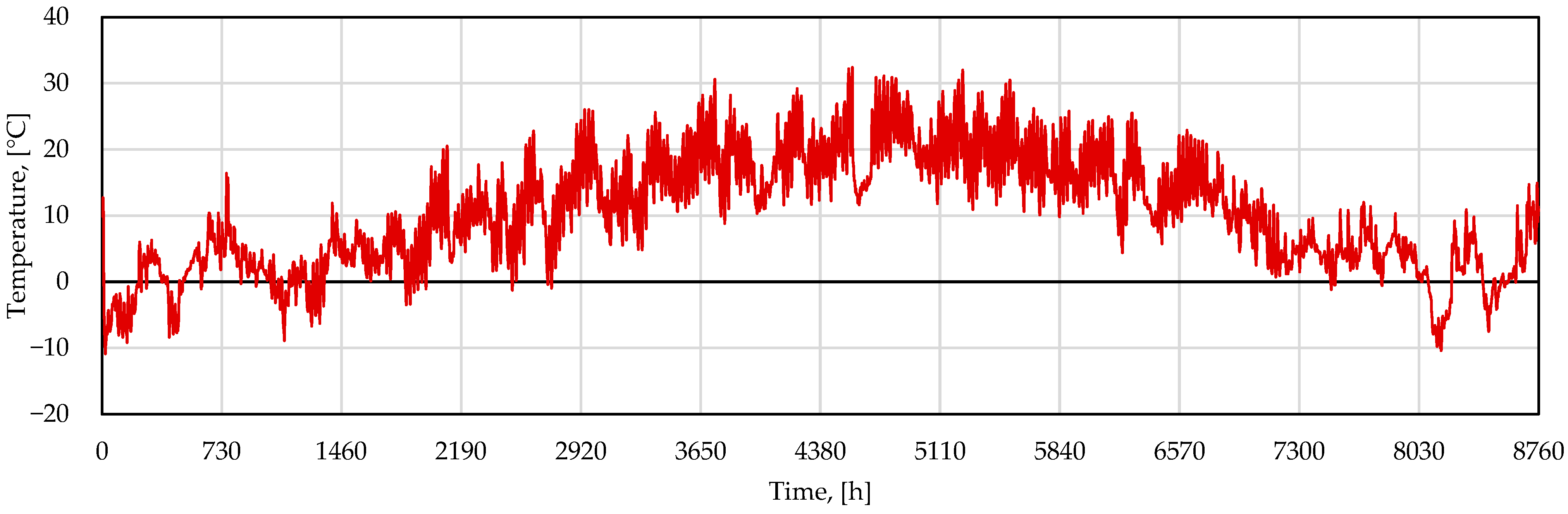

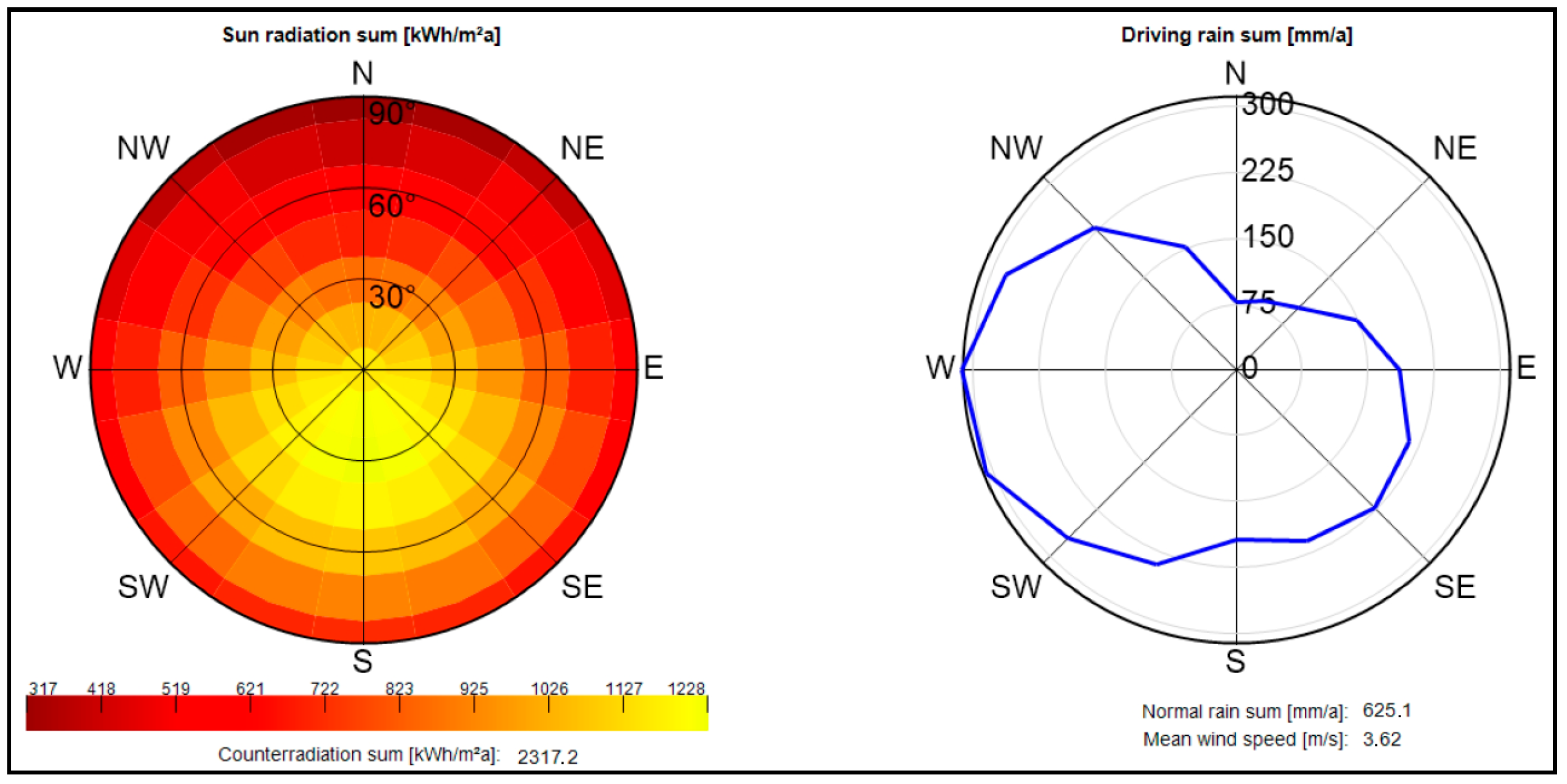

2.7. Essen

3. Results

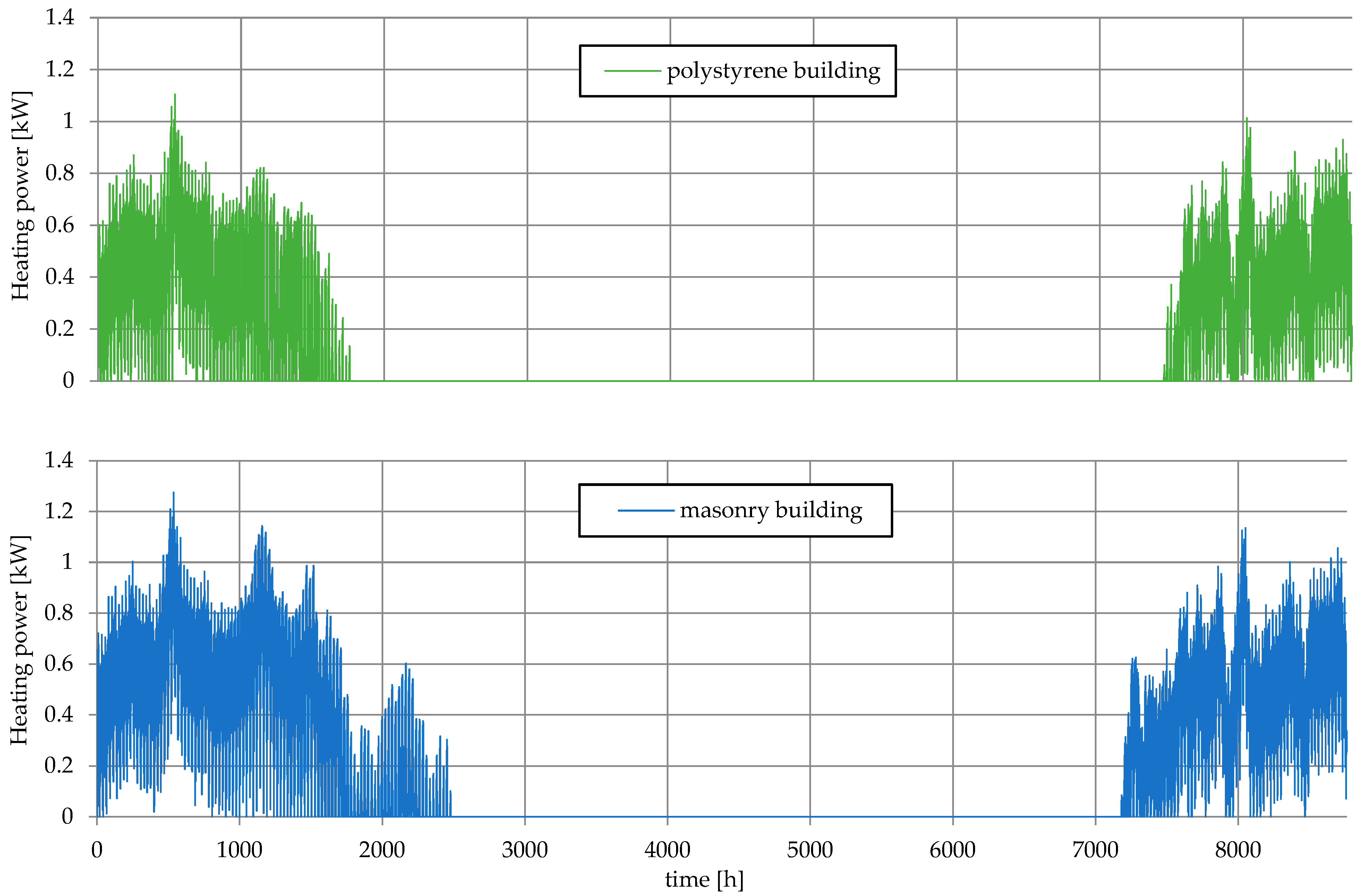

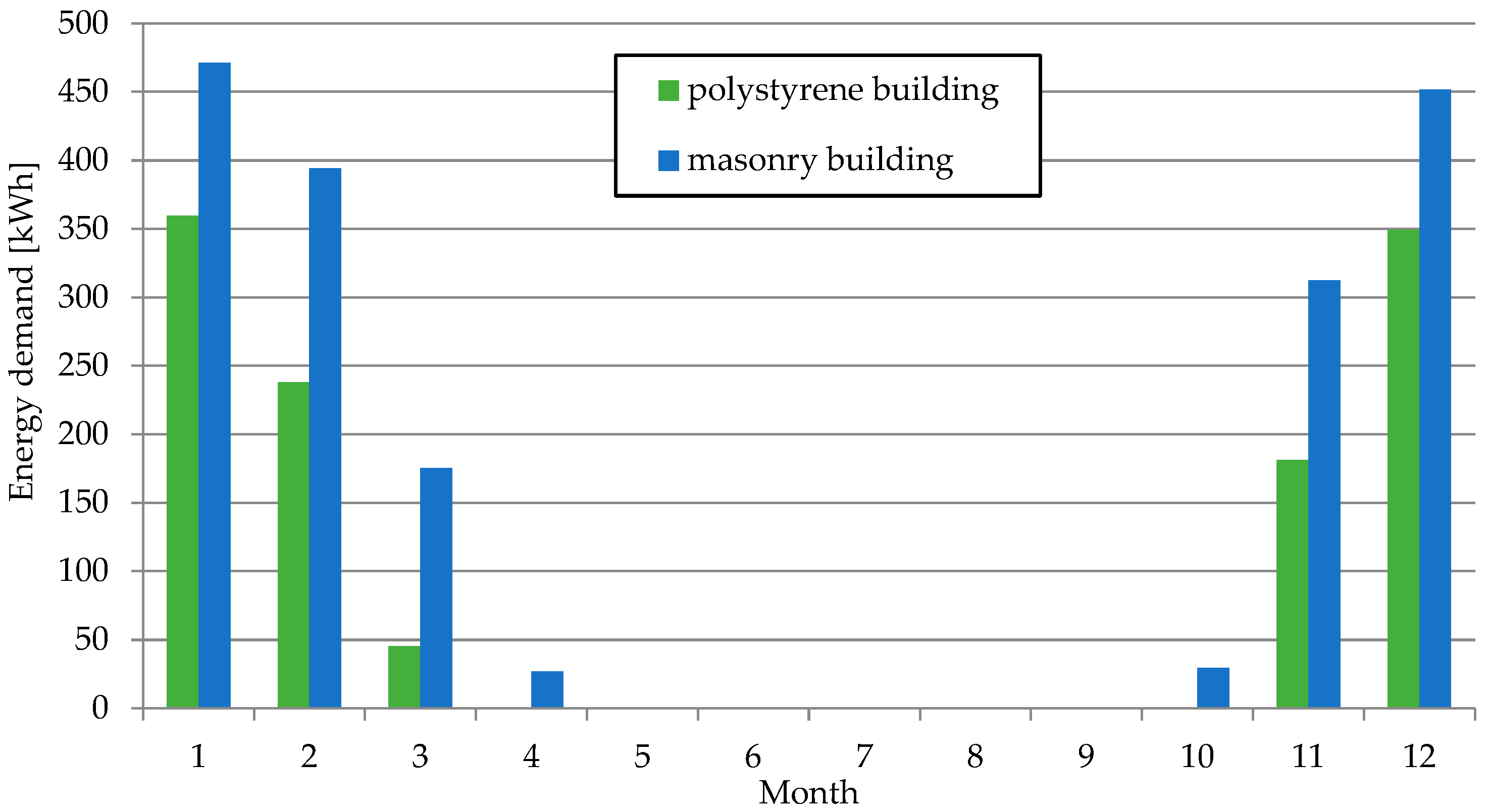

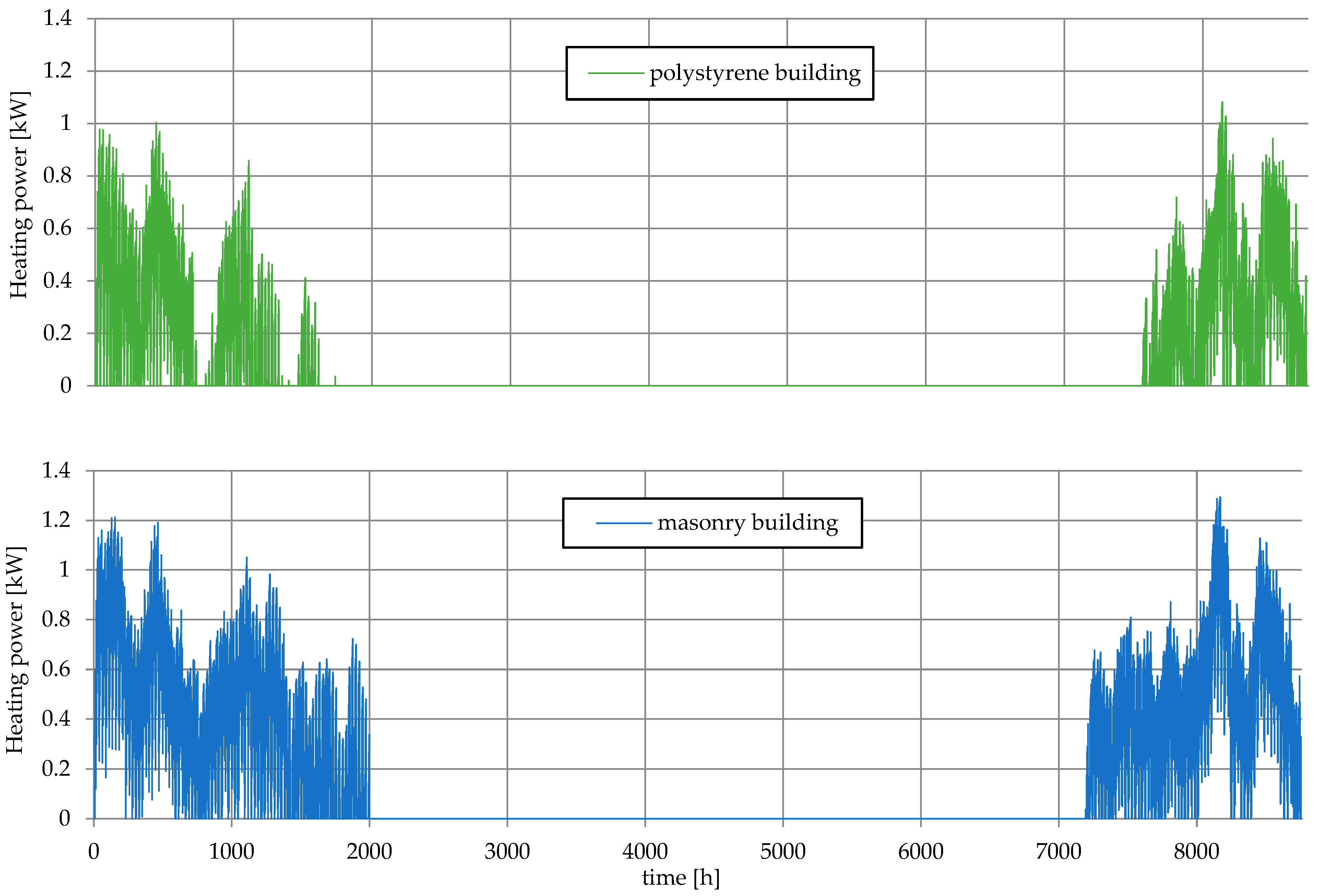

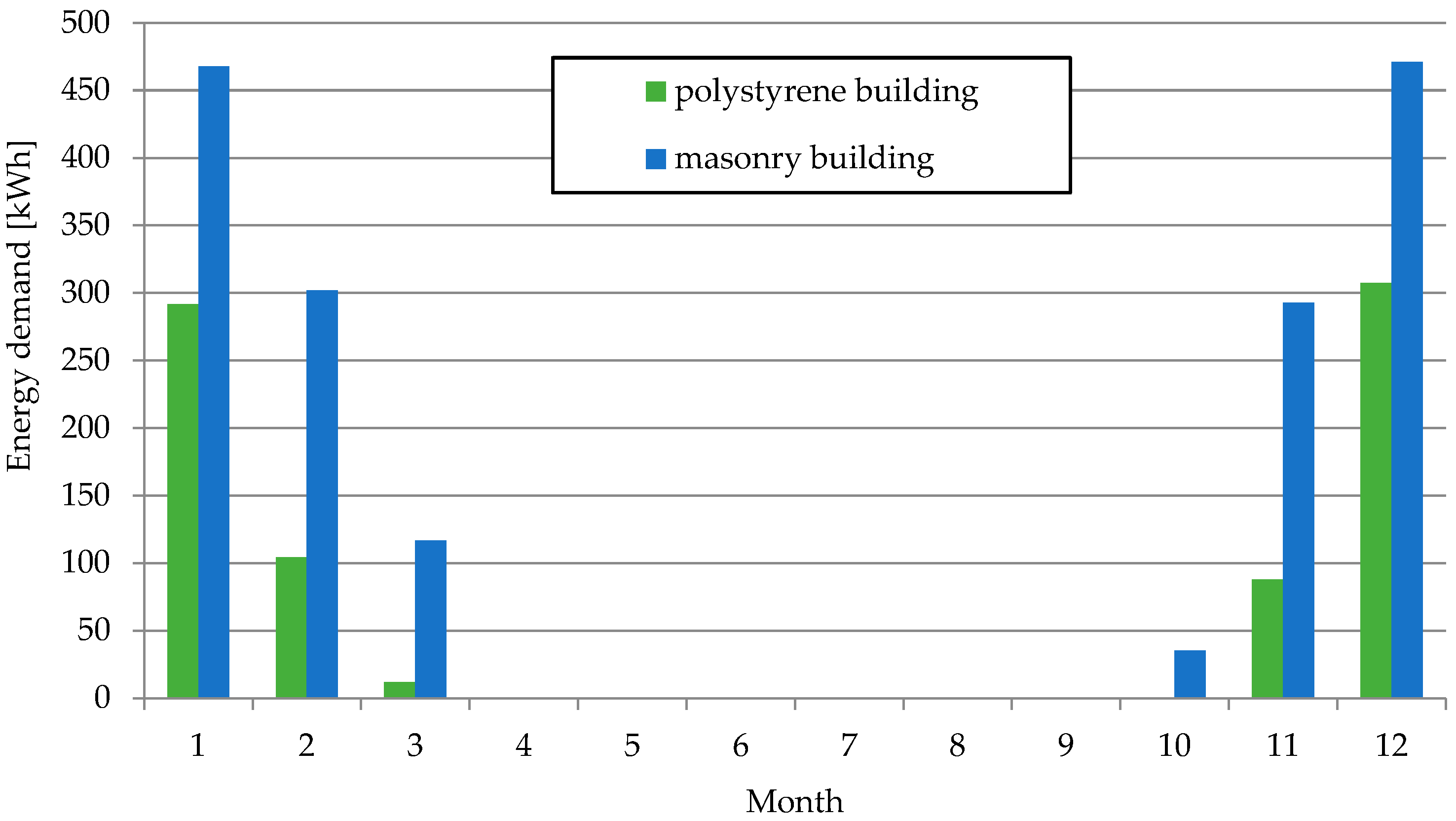

3.1. Energy Demand—Kołobrzeg

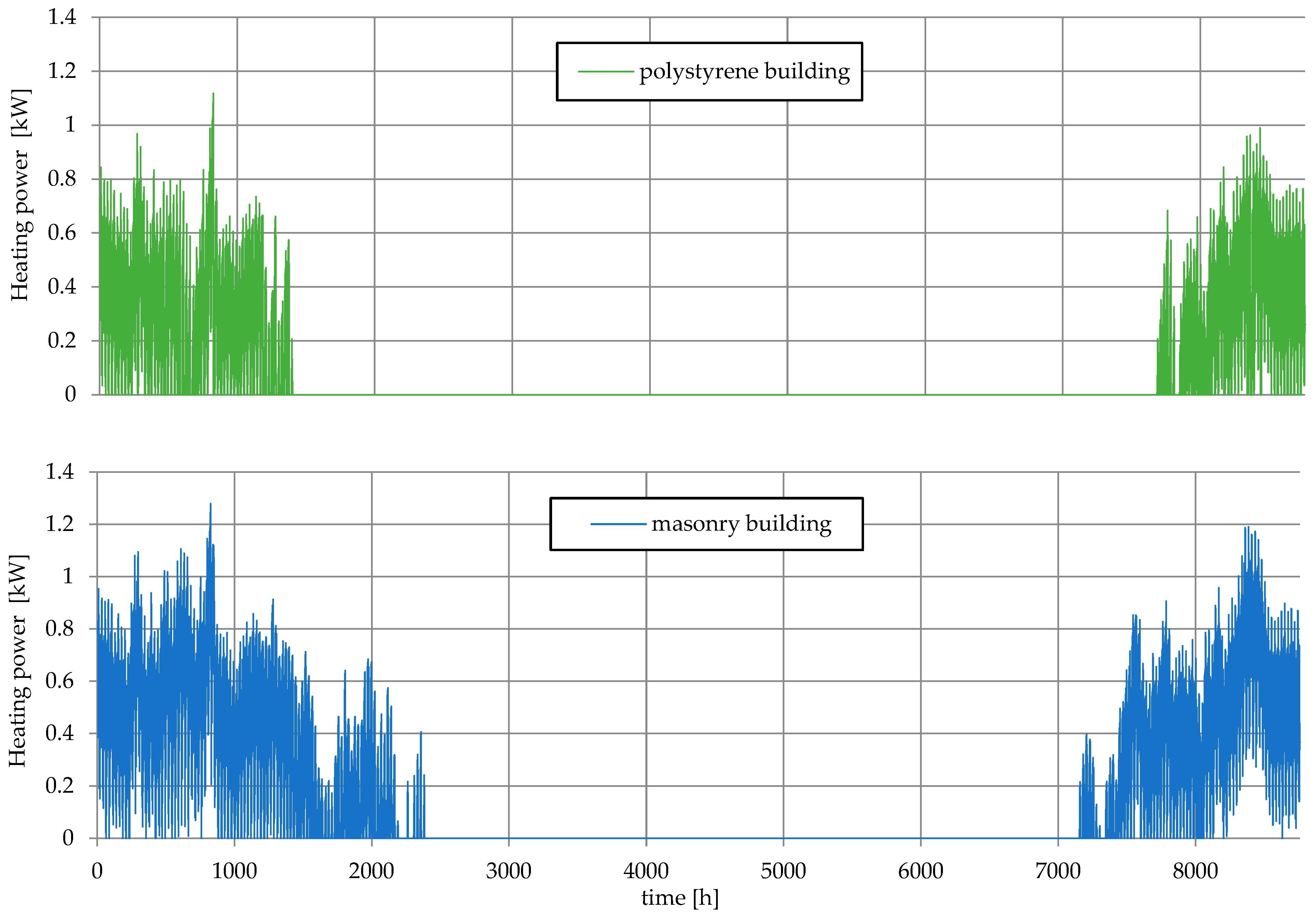

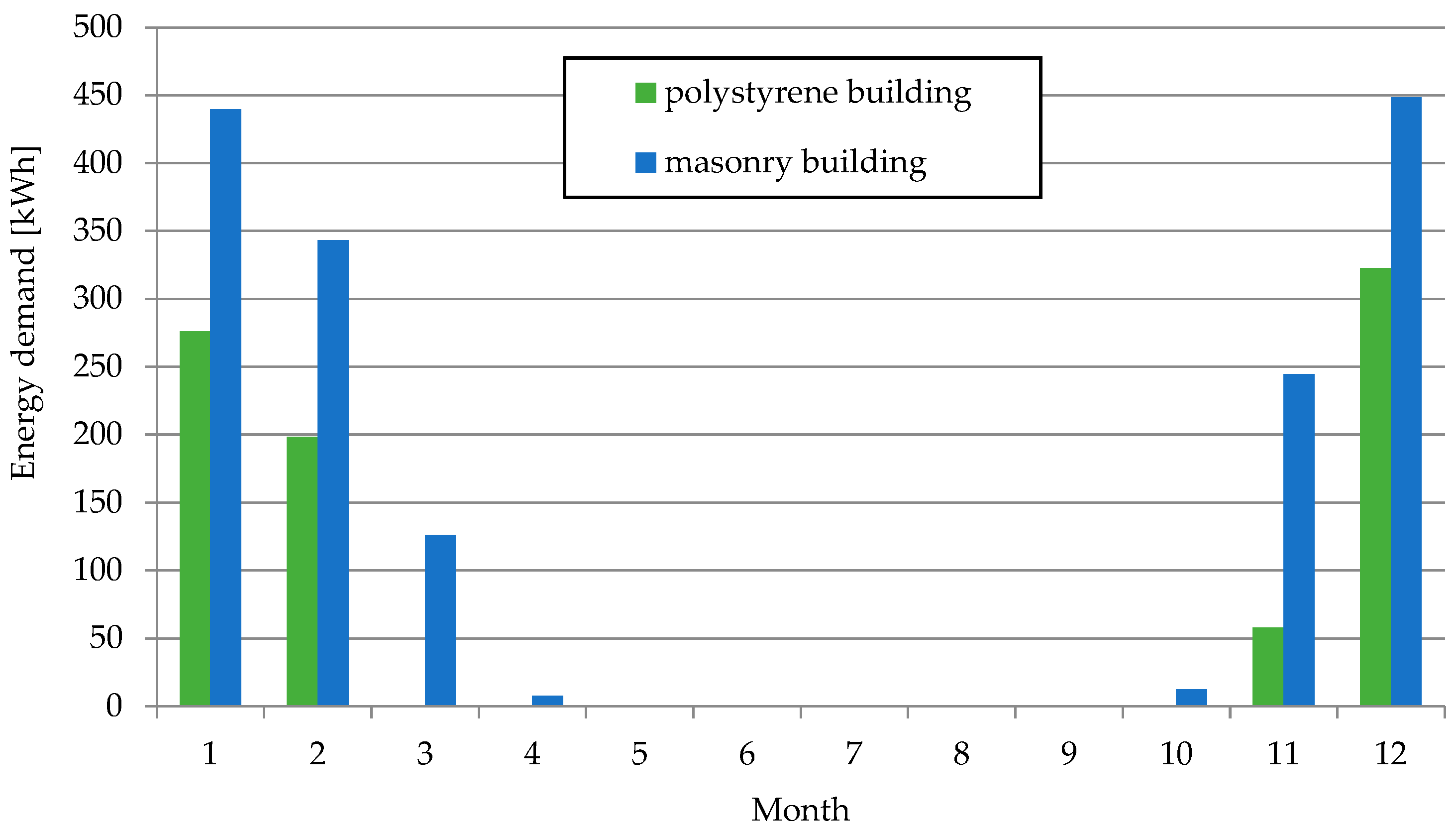

3.2. Energy Demand—Vienna

3.3. Energy Demand—Essen

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| IEA | International Energy Agency |

| PH | Passive House |

| ICF | Insulated Concrete Forms |

| SIP | Structural Insulated Panels |

References

- IEA. Energy Efficiency 2023; IEA: Paris, France, 2023; Available online: https://www.iea.org/reports/energy-efficiency-2023 (accessed on 6 October 2025).

- Passive House Institute (PHI). Available online: https://passivehouse.com (accessed on 6 October 2025).

- Anand, V.; Kadiri, V.L.; Putcha, C. Passive buildings: A state-of-the-art review. J. Infrastruct. Preserv. Resil. 2023, 4, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Firląg, S.; Baig, A.S.; Koc, D. Historical Analysis of Real Energy Consumption and Indoor Conditions in Single-Family Passive Building. Sustainability 2025, 17, 717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mihai, M.; Tanasiev, V.; Dinca, C.; Badea, A.; Vidu, R. Passive house analysis in terms of energy performance. Energy Build. 2017, 144, 74–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wąs, K.; Radoń, J.; Sadłowska-Sałęga, A. Maintenance of Passive House Standard in the Light of Long-Term Study on Energy Use in a Prefabricated Lightweight Passive House in Central Europe. Energies 2020, 13, 2801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnston, D.; Siddall, M.; Ottinger, O.; Soeren, P.; Feist, W. Are the energy savings of the passive house standard reliable? A review of the as-built thermal and space heating performance of passive house dwellings from 1990 to 2018. Energy Effic. 2020, 13, 1605–1631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, J.; Dong, Y.; Wang, T.-H.; Chang, W.-S.; Park, J. U-Values for Building Envelopes of Different Materials: A Review. Buildings 2024, 14, 2434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kočí, V.; Bažantová, Z.; Černý, R. Computational analysis of thermal performance of a passive family house built of hollow clay bricks. Energy Build. 2014, 76, 211–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, X.; Wang, Y.; Rouapoor, M.; Wu, Q.; Roskilly, T. Comparison of building performance between Conventional House and Passive House in the UK. Energy Procedia 2017, 142, 1823–1828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kosny, J.; Asiz, A.; Smith, I.; Shresta, S.; Fallahi, A. A review of high R-value wood framed and composite wood wall technologies using advanced insulation techniques. Energy Build. 2014, 72, 441–456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cabral, M.R.; Blanchet, P. A State of the Art of the Overall Energy Efficiency of Wood Buildings—An Overview and Future Possibilities. Materials 2021, 14, 1848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feist, W.; Schnieders, J.; Dorer, V.; Haas, A. Re-inventing air heating: Convenient and comfortable within the frame of the Passive House concept. Energy Build. 2005, 37, 1186–1203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahapatra, K.; Olsson, S. Energy Performance of Two Multi-Story Wood-Frame Passive Houses in Sweden. Buildings 2015, 5, 1207–1220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mazur, Ł.; Szlachetka, O.; Jeleniewicz, K.; Piotrowski, M. External Wall Systems in Passive House Standard: Material, Thermal and Environmental LCA Analysis. Buildings 2024, 14, 742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maref, W.; Armstrong, M.M.; Saber, H.H.; Rousseau, M.; Ganapathy, G.; Nicholls, M.; Swinton, M.C. Field Energy Performance of an Insulating Concrete form (ICF) Wall; National Research Council of Canada: Ottawa, ON, Canada, 2012. [CrossRef]

- Ekrami, N.; Garat, A.; Fung, A.S. Thermal Analysis of Insulated Concrete Form (ICF) Walls. Energy Procedia 2015, 75, 2150–2156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mantesi, E.; Hopfe, C.J.; Mourkos, K.; Glass, J.; Cook, M. Empirical and computational evidence for thermal mass assessment: The example of insulating concrete formwork. Energy Build. 2019, 188–189, 314–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kashan, M.E.; Fung, A.S.; Eisapour, A.H. Insulated concrete form foundation wall as solar thermal energy storage for Cold-Climate building heating system. Energy Convers. Manag. X 2023, 19, 100391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Maghraby, Y.; Tarabieh, K.; Sharkass, M.; Mashaly, I.; Fahmy, E. Thermal and Structural Performances of Screen Grid Insulated Concrete Forms (SGICFs) Using Experimental Testing. Buildings 2024, 14, 2599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fard, F.A.; Jafarpour, A.; Nasiri, F. Comparative assessment of insulated concrete wall technologies and wood-frame walls in residential buildings: A multi-criteria analysis of hygrothermal performance, cost, and environmental footprints. Adv. Build. Energy Res. 2019, 15, 466–498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghosh, S.; Bigelow, B. Comparative Analysis of Energy Efficiency: Insulated Concrete Form vs. Wood-Framed Residential Construction. Buildings 2025, 15, 804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nässén, J.; Hedenus, F.; Karlsson, S.; Holmberg, J. Concrete vs. wood in buildings—An energy system approach. Build. Environ. 2012, 51, 361–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amran, Y.H.M.; El-Zeadani, M.; Lee, Y.H.; Lee, Y.Y.; Murali, G.; Feduik, R. Design innovation, efficiency and applications of structural insulated panels: A review. Structures 2020, 27, 1358–1379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Finnegan, S.; Edwards, R.; Al-Derbi, B.; Campbell, I.; Fulton, M. The Potential of Structurally Insulated Panels (SIPs) to Supply Net Zero Carbon Housing. Buildings 2022, 12, 2081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- WUFI-Wärme Und Feuchte Instationär. Available online: https://wufi.de/en (accessed on 15 October 2025).

- Lengsfeld, K.; Holm, A. Entwicklung und Validierung einer hygrothermischen Raumklima-Simulationssoftware WUFI®-Plus. Bauphysik 2007, 29, 178–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sadłowska-Sałęga, A.; Radoń, J. Feasibility and limitation of calculative determination of hygrothermal conditions in historical buildings: Case study of st. Martin church in Wiśniowa. Build. Environ. 2020, 186, 107361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Radon, J.; Was, K.; Flaga-Maryanczyk, A.; Schnotale, J. Experimental and theoretical study on hygrothermal long-term performance of outer assemblies in lightweight passive house. J. Build. Phys. 2017, 41, 299–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nawalany, G.; Sokołowski, P. Numerical Analysis of the Effect of Ground Dampness on Heat Transfer between Greenhouse and Ground. Sustainability 2021, 13, 3084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nawalany, G.; Lendelova, J.; Sokołowski, P.; Zitnak, M. Numerical Analysis of the Impact of the Location of a Commercial Broiler House on Its Energy Management and Heat Exchange with the Ground. Energies 2021, 14, 8565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sadłowska-Sałęga, A.; Wąs, K. Moisture Risk Analysis for Three Construction Variants of a Wooden Inverted Flat Roof. Energies 2021, 14, 7898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coelho, G.B.A.; Silva, H.E.; Henriques, F.M.A. Calibrated hygrothermal simulation models for historical buildings. Build. Environ. 2018, 142, 439–450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laska, M.; Reclik, K. Analysis of Internal Conditions and Energy Consumption during Winter in an Apartment Located in a Tenement Building in Poland. Sustainability 2024, 16, 3958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dylewski, R. Optimal Thermal Insulation Thicknesses of External Walls Based on Economic and Ecological Heating Cost. Energies 2019, 12, 3415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aviža, D. Investigation of the Determination of the Cost-Optimal Thickness of the Thermal Insulation Layer of the Walls of a Modernized Public Building. Taikom. Tyrim. Stud. Ir. Prakt. Appl. Res. Stud. Pract. 2021, 17, 79–84. Available online: https://ojs.panko.lt/index.php/ARSP/article/view/148 (accessed on 6 October 2025).

| Layers | Thickness [m] | Thermal Conductivity [W/m·K] |

|---|---|---|

| Plasterboard | 0.0125 | 0.2 |

| Fibreglass mesh | 0.0005 | 0.035 |

| Compacted polystyrene | 0.48 | 0.036 |

| Fibreglass mesh | 0.0005 | 0.035 |

| External plaster | 0.01 | 0.87 |

| Layers | Thickness [m] | Thermal Conductivity [W/m·K] |

|---|---|---|

| Interior plaster | 0.01 | 0.2 |

| Aerated concrete | 0.25 | 0.14 |

| Compacted polystyrene | 0.23 | 0.036 |

| External plaster | 0.01 | 0.87 |

| Layers | Thickness [m] | Thermal Conductivity [W/m·K] |

|---|---|---|

| Sheet metal | 0.0005 | 60 |

| Fibreglass mesh | 0.001 | 0.035 |

| Compacted polystyrene | 0.48 | 0.036 |

| Fibreglass mesh | 0.001 | 0.035 |

| Plasterboard | 0.0125 | 0.2 |

| Layers | Thickness [m] | Thermal Conductivity [W/m·K] |

|---|---|---|

| Sheet metal | 0.0005 | 60 |

| Air layer | 0.12 | 0.035 |

| Vapour barrier foil | 0.001 | 2.3 |

| Mineral wool/rafter | 0.16 | 0.036 |

| Mineral wool | 0.2 | 0.036 |

| Vapour barrier foil | 0.001 | 2.3 |

| Plasterboard | 0.0125 | 0.2 |

| Layers | Thickness [m] | Thermal Conductivity [W/m·K] |

|---|---|---|

| Concrete screed | 0.0005 | 1.6 |

| Reinforced concrete slab | 0.2 | 1.6 |

| Compacted polystyrene | 0.4 | 0.036 |

| Construction film | 0.0001 | 2.3 |

| Lean concrete | 0.1 | 1.6 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Wąs, K.; Nawalany, G.; Žitňák, M. Analysis of Useful Energy Demand for Heating Purposes in a Building with a Self-Supporting Polystyrene Structure in a Temperate Climate. Energies 2025, 18, 6514. https://doi.org/10.3390/en18246514

Wąs K, Nawalany G, Žitňák M. Analysis of Useful Energy Demand for Heating Purposes in a Building with a Self-Supporting Polystyrene Structure in a Temperate Climate. Energies. 2025; 18(24):6514. https://doi.org/10.3390/en18246514

Chicago/Turabian StyleWąs, Krzysztof, Grzegorz Nawalany, and Miroslav Žitňák. 2025. "Analysis of Useful Energy Demand for Heating Purposes in a Building with a Self-Supporting Polystyrene Structure in a Temperate Climate" Energies 18, no. 24: 6514. https://doi.org/10.3390/en18246514

APA StyleWąs, K., Nawalany, G., & Žitňák, M. (2025). Analysis of Useful Energy Demand for Heating Purposes in a Building with a Self-Supporting Polystyrene Structure in a Temperate Climate. Energies, 18(24), 6514. https://doi.org/10.3390/en18246514