A Multi-Time Scale Optimal Dispatch Strategy for Green Ammonia Production Using Wind–Solar Hydrogen Under Renewable Energy Fluctuations

Abstract

1. Introduction

- (1)

- A High-Fidelity Multi-Timescale MILP Dispatch Model: An integrated scheduling framework is developed, including the dynamic interactions among renewable energy generation, electrolytic cell, hydrogen storage and Haber–Bosch process, as well as the stability and ramping constraints of ammonia production. The model aims to realize the coordinated scheduling of each section in the wind–solar hydrogen production synthetic ammonia system, and maximize the economic profit while enhancing the stability of the synthetic ammonia production process.

- (2)

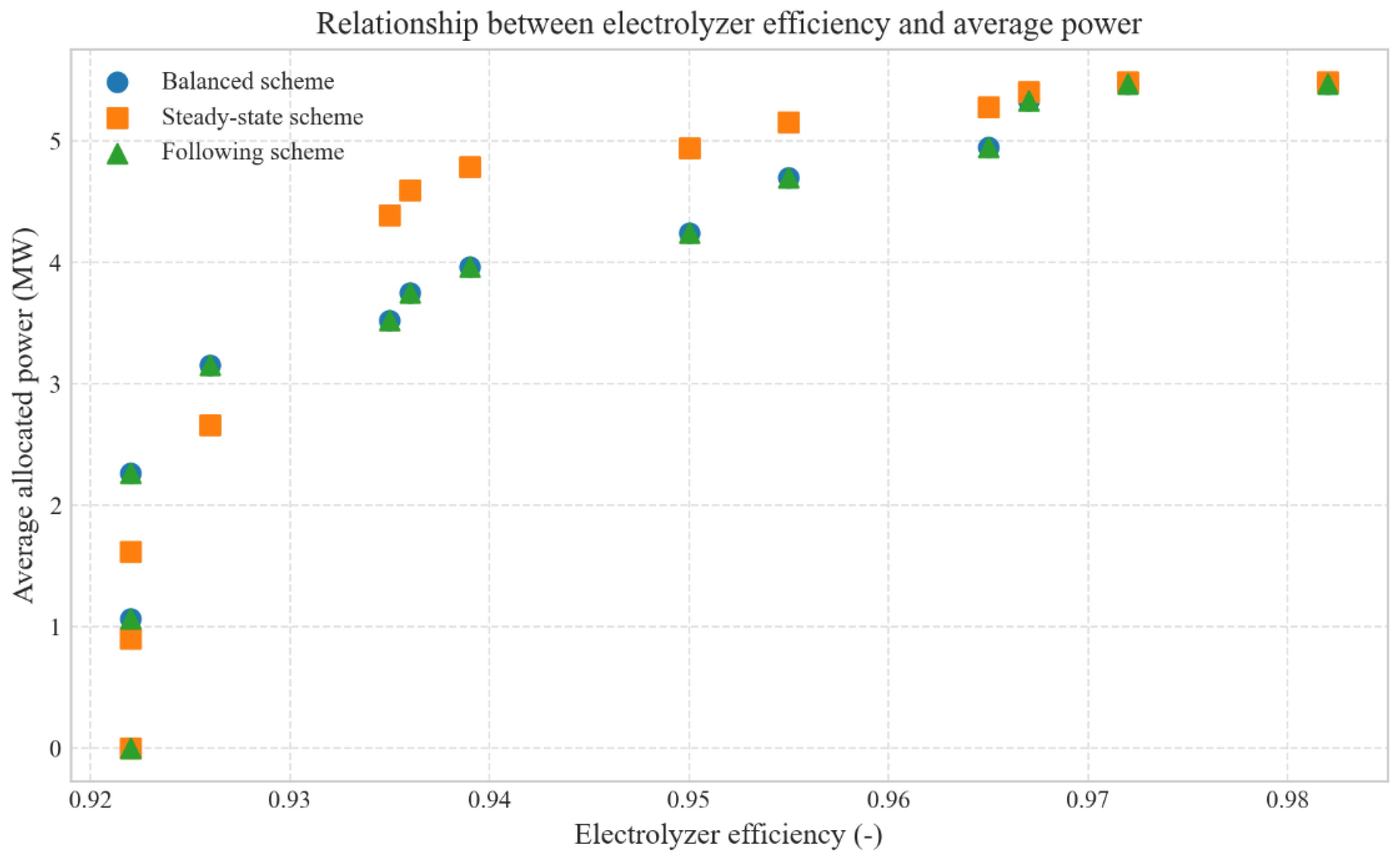

- A Novel Efficiency-Priority Power Allocation Strategy (EPPA): This strategy explicitly considers the efficiency difference between each unit and dynamically allocates higher power load to more efficient electrolyzers. This aims to maximize the total hydrogen production rate per unit power consumption of the cluster, thereby reducing the energy consumption ratio and reducing the degree of degradation of the electrolytic cell.

- (3)

- A Rigorous Multi-Dimensional Performance Validation: The proposed framework is rigorously validated via a 72-h case study using real wind–solar data. A comparative analysis against two benchmarks—a rigid “Steady-State Scheme” and a volatile “Following Scheme”—across multiple key performance indicators quantitatively demonstrates the superiority of the “Balanced Scheme” in balancing economic efficiency, renewable integration, and operational robustness.

2. Methods and Modeling

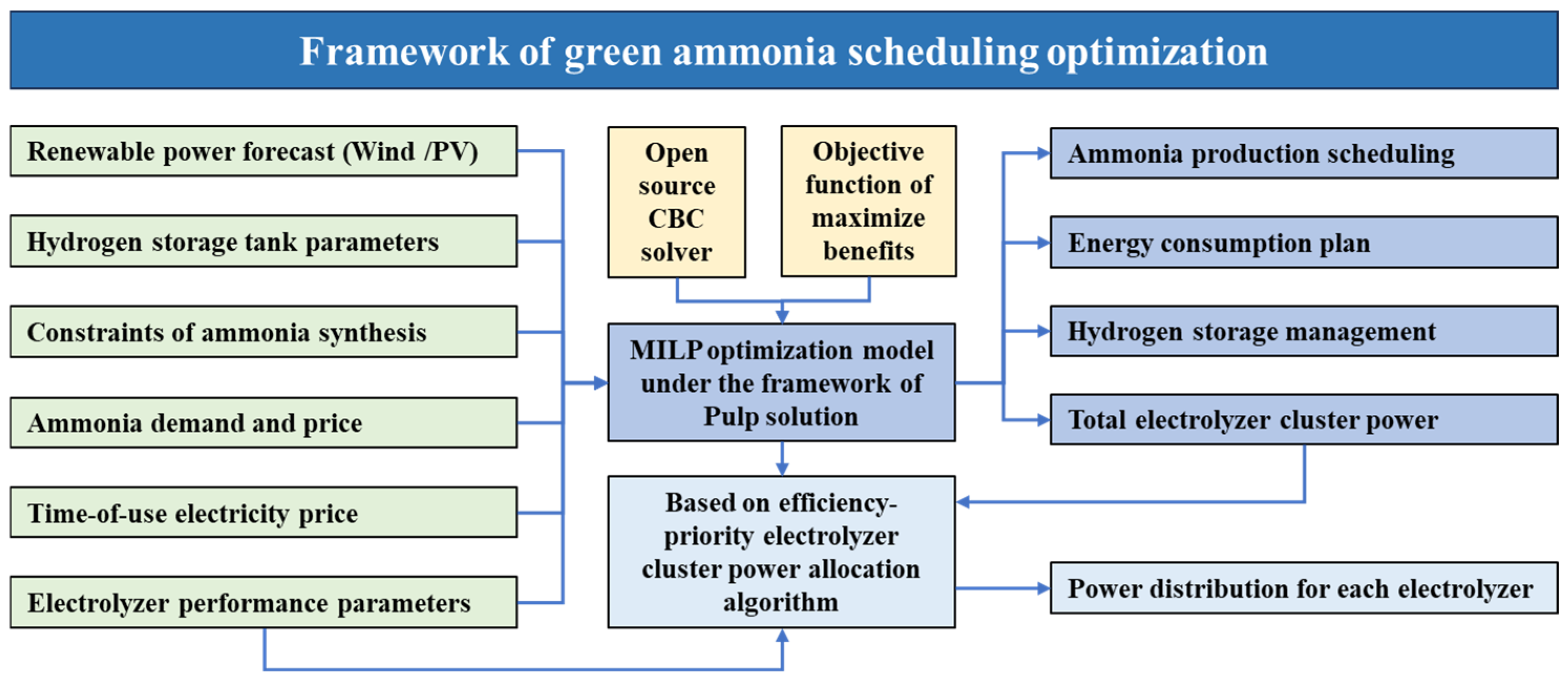

2.1. System Overview

- (1)

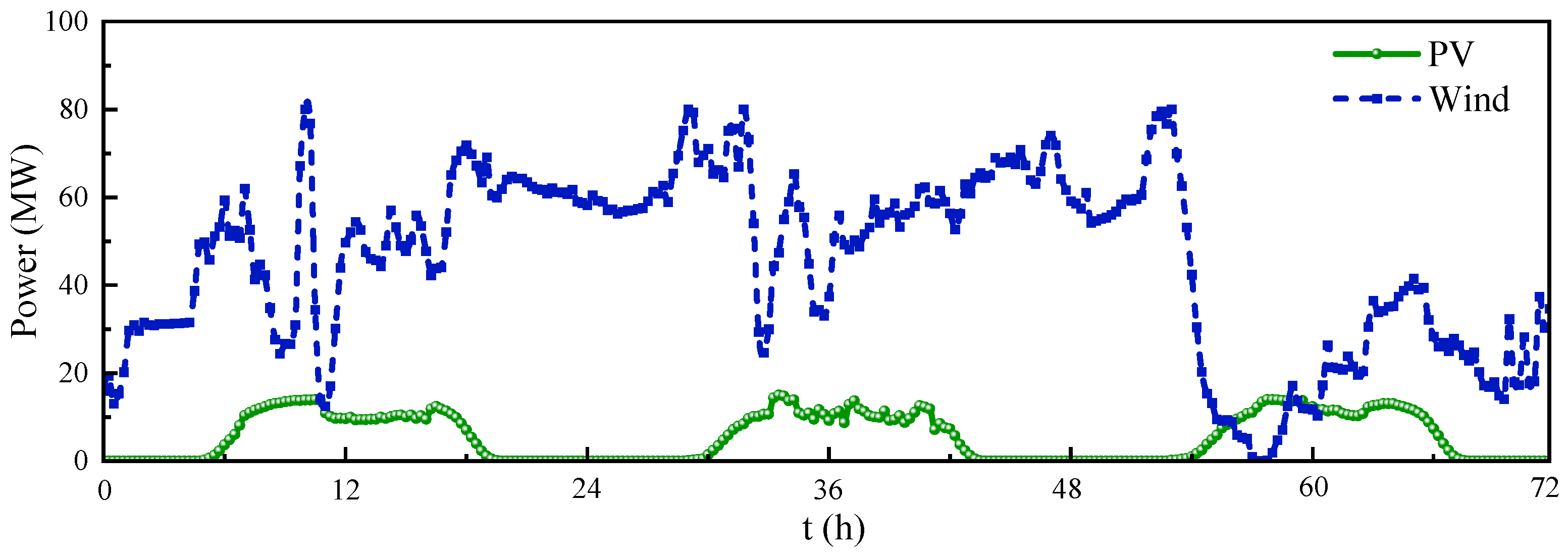

- Renewable energy output forecast data, containing short-term power predictions for wind and PV;

- (2)

- Hydrogen storage parameters, covering operational boundaries such as tank capacity and charge/discharge rate limits;

- (3)

- Ammonia synthesis constraints, including process limitations like the reactor load adjustment range and minimum continuous operation time;

- (4)

- Market information, involving ammonia product demand and dynamic market prices;

- (5)

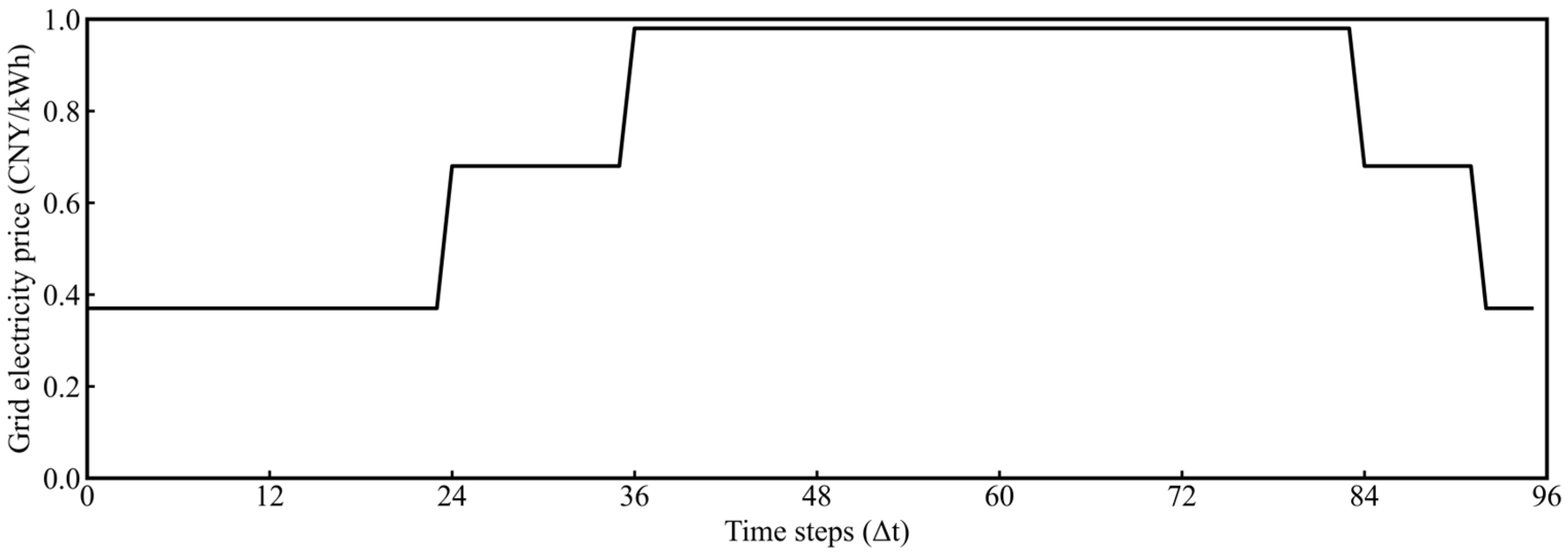

- Time-of-use electricity prices, reflecting temporal economic signals for grid power purchase/sale;

- (6)

- Performance parameters, characterizing the capacity, efficiency characteristics, and operational status of the electrolyzer cluster.

- (1)

- The upper level is an MILP optimization model based on the PuLP framework and the CBC solver@. With the objective function of maximizing economic benefits, it comprehensively considers multiple constraints such as renewable energy consumption, hydrogen storage charge/discharge timing, and the load regulation capability of ammonia synthesis. It optimizes to obtain the ammonia production schedule, energy consumption plan, hydrogen storage dispatch strategy, and the total power demand of the electrolyzer cluster;

- (2)

- The lower level is an efficiency-priority power allocation algorithm for the electrolyzer cluster. Based on the total power demand output from the MILP model and the efficiency status of individual electrolyzers, it achieves optimal power distribution within the cluster to maximize overall hydrogen production efficiency and reduce system energy consumption.

2.2. Modeling of the Wind–Solar Hydrogen-to-Ammonia System

2.2.1. Wind–Solar Power Generation Section

2.2.2. Water Electrolysis Hydrogen Production Section

2.2.3. Hydrogen Storage Section

2.2.4. Air Separation Nitrogen Production Section

2.2.5. Ammonia Synthesis Section

2.3. Composite Optimization Objective Function

- (1)

- Net Ammonia Production Revenue

- (2)

- Electricity Purchase Cost

- (3)

- Ammonia Production Load Fluctuation Penalty Term

- (4)

- Power Curtailment Penalty Term

2.4. Electrolyzer Cluster Power Allocation Strategy

| Algorithm 1. Efficiency-Priority Power Allocation Strategy for Electrolyzer Cluster |

|

3. Case Study

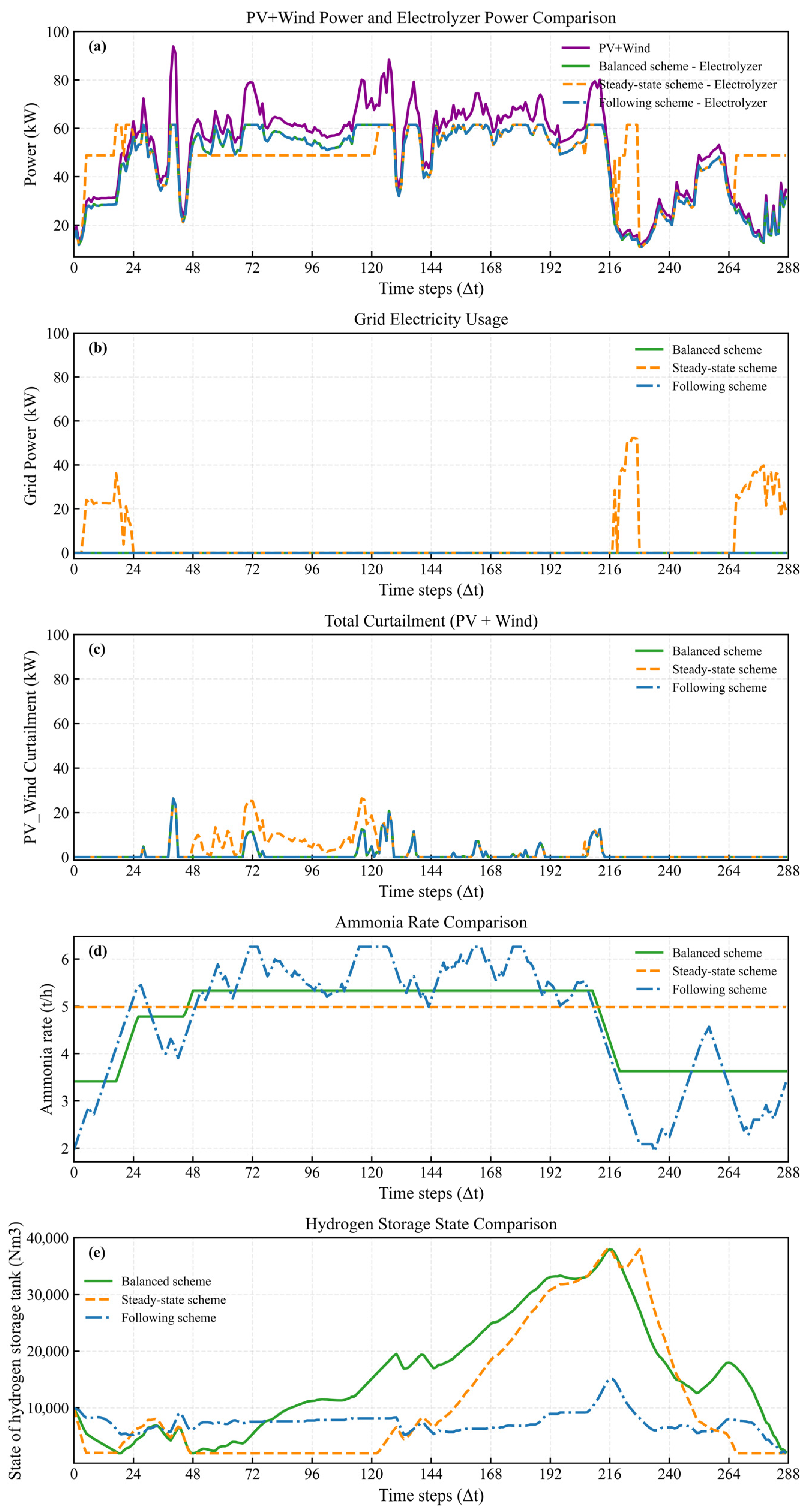

3.1. Dispatch Results Analysis

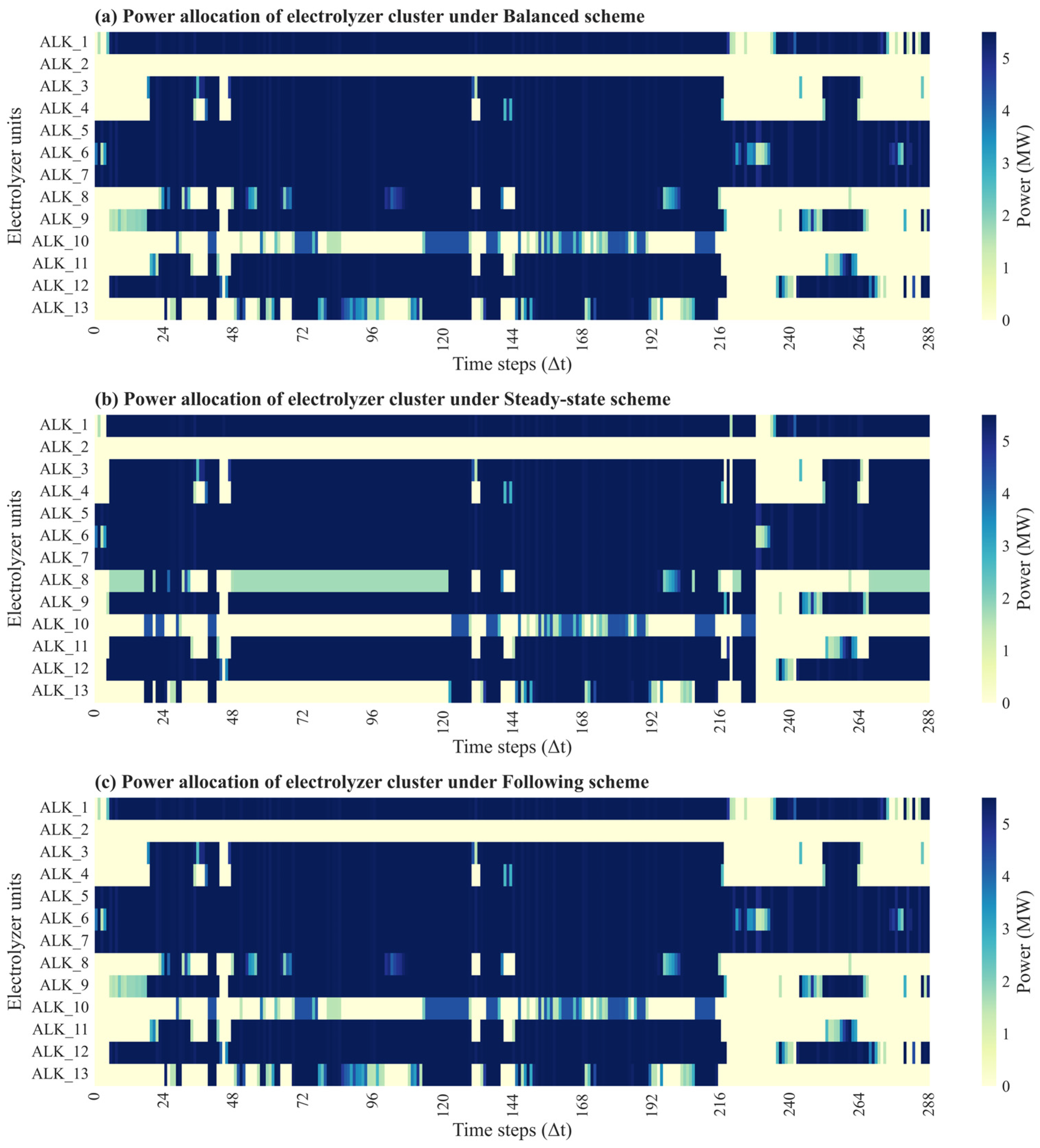

- (1)

- Balanced Scheme (Scheme A): achieves comprehensive coordination between renewable energy utilization and system load stability. All four sub-objectives in the composite optimization—ammonia revenue, electricity cost, load fluctuation penalty, and curtailment penalty—are considered, and the weight coefficients are set to [1, 1, 1, 1]. The reason for the equal weight of 1 is that all sub-goals are represented by the corresponding monetary unit (CNY) to ensure that each project contributes to the total cost based on its inherent economic impact, without arbitrary scaling.

- (2)

- Steady-State Scheme (Scheme B): corresponds to the traditional continuous, constant-load operation mode of chemical plants, primarily relying on the grid to compensate for renewable fluctuations. Since the load is constant and curtailment is not penalized, the weight coefficients are set to [1, 1, 0, 0].

- (3)

- Following Scheme (Scheme C): the system load varies with the fluctuations in renewable power output, without fully considering the dynamic constraints and equipment adaptability of the chemical process. Similar to Scheme B, only the economic objectives are considered, with weight coefficients are set to [1, 1, 0, 0].

3.2. Analysis of Electrolyzer Cluster Control Effectiveness

4. Conclusions

- (1)

- Under fluctuating renewable generation, the Balanced Dispatch Scheme achieves high self-sufficiency, with a 2.4% curtailment rate and no grid electricity dependence. It effectively balances power fluctuation mitigation and load stability. Compared to the Steady-State Scheme, it reduces the unit electricity cost by about 19.4% and increases comprehensive revenue by approximately 169,000 CNY, significantly improving both economic performance and energy utilization efficiency.

- (2)

- Although the apparent revenue of the Following Scheme is similar to that of the Balanced Dispatch Scheme, its frequent load fluctuations lead to a significant increase in equipment start-stop cycles, posing potential issues such as reduced lifespan and worsened thermal stability. Consequently, it is unsuitable for long-term continuous chemical production.

- (3)

- The efficiency-priority power allocation strategy for electrolyzers effectively prevents overloading of some units and enhances the overall energy efficiency and operational stability of the hydrogen production system cluster.

- (4)

- The proposed scheduling framework has economy, flexibility and stability in the scenario of high penetration of renewable energy, which provides a systematic modeling idea and practical reference for the intelligent operation of green ammonia system, and is of great significance to promote the integration of new energy-chemical industry and low carbonization of industry.

- (5)

- Future research can extend this framework by incorporating electrolyzer degradation prediction models, adopting stochastic or robust optimization to better handle long-term renewable uncertainty, refining dynamic models of the ammonia synthesis loop, and developing real-time optimization or AI-assisted control strategies. These directions may further enhance system flexibility, operational reliability, and large-scale applicability of renewable-powered ammonia production.

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Nomenclature

| PV | Photovoltaic |

| ALK | Alkaline electrolyzer |

| EPPA | Efficiency-priority power allocation strategy |

| TEA | Techno-economic analysis |

| MILP | Mixed-integer linear programming |

| MINLP | Mixed-integer nonlinear programming |

| ASU | Air separation unit |

| Wind power at time t | |

| PV power at time t | |

| Grid-purchased power at time t | |

| Power for water electrolysis at time t | |

| Auxiliary power consumption at time t | |

| Curtailed wind power at time t | |

| Curtailed PV power at time t | |

| Total hydrogen production from all electrolyzers at time t | |

| Total hydrogen production power of all electrolyzers at time t | |

| The rated hydrogen production power consumption | |

| Dispatch time step | |

| Lower limits for the total hydrogen production power of all electrolyzers | |

| Upper limits for the total hydrogen production power of all electrolyzers | |

| Total hydrogen consumption by the ammonia synthesis section at time t | |

| Hydrogen charging flow rates of the storage tank at time t | |

| Hydrogen discharging flow rates of the storage tank at time t | |

| Storage tank is in charging state at time t | |

| Storage tank is in discharging state at time t | |

| Storage tank is in idle state at time t | |

| The capacity of the hydrogen storage tank at time t + 1 | |

| The capacity of the hydrogen storage tank at time t | |

| The lower capacity limits of the hydrogen storage tank | |

| The upper capacity limits of the hydrogen storage tank | |

| Nitrogen demand at time t | |

| Hydrogen-to-nitrogen ratio | |

| Rated ammonia production rate | |

| Load factor of the ammonia synthesis unit | |

| Load ramp rate of the ammonia synthesis unit | |

| Ammonia production rate at time t | |

| Ammonia production rate at time t − 1 | |

| The lower limits of the ammonia synthesis unit load factor | |

| The upper limits of the ammonia synthesis unit load factor | |

| The upper limits of the load ramp rate coefficient | |

| The lower limits of the load ramp rate coefficient | |

| Hydrogen consumption per ton of ammonia | |

| Net ammonia production revenue | |

| Electricity purchase cost | |

| Ammonia production load fluctuation penalty term | |

| Power curtailment penalty term | |

| The weighting coefficient for net ammonia production revenue | |

| The weighting coefficient for electricity purchase cost | |

| The weighting coefficient for net ammonia production load fluctuation penalty Term | |

| The weighting coefficient for power curtailment penalty term | |

| Selling price of ammonia | |

| The price of wind and solar green electricity | |

| The time-of-use gird electricity price | |

| The penalty coefficient for ammonia load fluctuation | |

| Rated power of electrolytic cell in EPPA algorithm | |

| The lower limits of electrolytic cell in EPPA algorithm | |

| The upper limits of electrolytic cell in EPPA algorithm | |

| Electrolytic cell i power in EPPA algorithm | |

| Electrolytic cell i efficiency in EPPA algorithm | |

| The lower ratio limits of electrolytic cell in EPPA algorithm | |

| The upper ratio limits of electrolytic cell in EPPA algorithm | |

| The remaining hydrogen in EPPA algorithm | |

| The collection of electrolytic cells sorted in descending order of efficiency in EPPA algorithm | |

| Total demand of hydrogen production in EPPA algorithm | |

| The upper hydrogen production of electrolytic cell i in EPPA algorithm | |

| Electrolytic cell i hydrogen production in EPPA algorithm | |

| Index for electrolytic cells | |

| Index for time periods |

References

- Liu, L.; Wang, Y.; Wang, Z.; Li, S.; Li, J.; He, G.; Li, Y.; Liu, Y.; Piao, S.; Gao, Z.; et al. Potential contributions of wind and solar power to China’s carbon neutrality. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2022, 180, 106155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mucci, S.; Mitsos, A.; Bongartz, D. Power-to-X processes based on PEM water electrolyzers: A review of process integration and flexible operation. Comput. Chem. Eng. 2023, 175, 108260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klyapovskiy, S.; Zheng, Y.; You, S.; Bindner, H.W. Optimal operation of the hydrogen-based energy management system with P2X demand response and ammonia plant. Appl. Energy 2021, 304, 117559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, J.; Tong, B.; Wang, H.; Xu, G.; Zhang, R.; Zhang, W. Flexible design and operation of off-grid green ammonia systems with gravity energy storage under long-term renewable power uncertainty. Appl. Energy 2025, 388, 125629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Song, M.; Jia, M.; Li, B.; Fei, H.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, X. Multi-objective distributionally robust optimization for hydrogen-involved total renewable energy CCHP planning under source-load uncertainties. Appl. Energy 2023, 342, 121212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lan, R.; Irvine, J.T.S.; Tao, S. Ammonia and related chemicals as potential indirect hydrogen storage materials. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2012, 37, 1482–1494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elahi, S.; Seddighi, S. Renewable energy storage using hydrogen produced from seawater membrane-less electrolysis powered by triboelectric nanogenerators. J. Power Sources 2024, 609, 234682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ojelade, O.A.; Zaman, S.F.; Ni, B.-J. Green ammonia production technologies: A review of practical progress. J. Environ. Manag. 2023, 342, 118348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, C.; Walsh, S.D.C.; Longden, T.; Palmer, G.; Lutalo, I.; Dargaville, R. Optimising renewable generation configurations of off-grid green ammonia production systems considering Haber-Bosch flexibility. Energy Convers. Manag. 2023, 280, 116790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fasihi, M.; Weiss, R.; Savolainen, J.; Breyer, C. Global potential of green ammonia based on hybrid PV-wind power plants. Appl. Energy 2021, 294, 116170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheema, I.I.; Krewer, U. Operating envelope of Haber–Bosch process design for power-to-ammonia. RSC Adv. 2018, 8, 34926–34936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verleysen, K.; Parente, A.; Contino, F. How does a resilient, flexible ammonia process look? Robust design optimization of a Haber-Bosch process with optimal dynamic control powered by wind. Proc. Combust. Inst. 2023, 39, 5511–5520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chehade, G.; Dincer, I. Progress in green ammonia production as potential carbon-free fuel. Fuel 2021, 299, 120845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calise, F.; Cappiello, F.L.; Cimmino, L.; Dentice d’Accadia, M.; Vicidomini, M. Thermo-economic analysis and dynamic simulation of a novel layout of a renewable energy community for an existing residential district in Italy. Energy Convers. Manag. 2024, 313, 118582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Lin, J.; Heuser, P.M.; Heinrichs, H.U.; Xiao, J.; Liu, F.; Robinius, M.; Song, Y.; Stolten, D. Co-Planning of Regional Wind Resources-based Ammonia Industry and the Electric Network: A Case Study of Inner Mongolia. IEEE Trans. Power Syst. 2022, 37, 65–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Wang, L.; Van herle, J.; Maréchal, F.; Desideri, U. Techno-economic comparison of green ammonia production processes. Appl. Energy 2020, 259, 114135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Armijo, J.; Philibert, C. Flexible production of green hydrogen and ammonia from variable solar and wind energy: Case study of Chile and Argentina. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2020, 45, 1541–1558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassan, Q.; Sameen, A.Z.; Salman, H.M.; Jaszczur, M. Large-scale green hydrogen production via alkaline water electrolysis using solar and wind energy. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2023, 48, 34299–34315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, Z.; Lin, J.; Liu, F.; Li, J.; Zhao, Y.; Song, Y. Optimal Sizing of Isolated Renewable Power Systems with Ammonia Synthesis: Model and Solution Approach. IEEE Trans. Power Syst. 2024, 39, 6372–6385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allman, A.; Daoutidis, P. Optimal scheduling for wind-powered ammonia generation: Effects of key design parameters. Chem. Eng. Res. Des. 2018, 131, 5–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, J.; Zhang, Z.; Zhang, R.; Zhang, W.; Xu, G.; Wang, H. Optimal capacity and multi-stable flexible operation strategy of green ammonia systems: Adapting to fluctuations in renewable energy. Energy Convers. Manag. 2024, 314, 118720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karrabi, M.; Jabari, F.; Foroud, A.A. A green ammonia and solar-driven multi-generation system: Thermo-economic model and optimization considering molten salt thermal energy storage, fuel cell vehicles, and power-to-gas. Energy Convers. Manag. 2025, 323, 119226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Florez, J.; AlAbbad, M.; Vazquez-Sanchez, H.; Morales, M.G.; Sarathy, S.M. Optimizing islanded green ammonia and hydrogen production and export from Saudi Arabia. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2024, 56, 959–972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laimon, M.; Goh, S. Unlocking potential in renewable energy curtailment for green ammonia production. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2024, 71, 964–971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campion, N.; Nami, H.; Swisher, P.R.; Vang Hendriksen, P.; Münster, M. Techno-economic assessment of green ammonia production with different wind and solar potentials. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2023, 173, 113057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nayak-Luke, R.; Bañares-Alcántara, R.; Wilkinson, I. “Green” Ammonia: Impact of Renewable Energy Intermittency on Plant Sizing and Levelized Cost of Ammonia. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 2018, 57, 14607–14616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schulte Beerbühl, S.; Fröhling, M.; Schultmann, F. Combined scheduling and capacity planning of electricity-based ammonia production to integrate renewable energies. Eur. J. Oper. Res. 2015, 241, 851–862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez, A.; Martín, M. Optimal renewable production of ammonia from water and air. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 178, 325–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allman, A.; Palys, M.J.; Daoutidis, P. Scheduling-informed optimal design of systems with time-varying operation: A wind-powered ammonia case study. AIChE J. 2019, 65, e16434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mewafy, A.; Ismael, I.; Kaddah, S.S.; Hu, W.; Chen, Z.; Abulanwar, S. Optimal design of multiuse hybrid microgrids power by green hydrogen–ammonia. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2024, 192, 114174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Deng, X.; Zhang, T.; Liu, S.; Song, L.; Yang, F.; Ouyang, M.; Shen, X. Exploration of the configuration and operation rule of the multi-electrolyzers hybrid system of large-scale alkaline water hydrogen production system. Appl. Energy 2023, 331, 120413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varela, C.; Mostafa, M.; Zondervan, E. Modeling alkaline water electrolysis for power-to-x applications: A scheduling approach. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2021, 46, 9303–9313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiu, Y.; Zhou, Y.; Chen, S.; Zang, T.; Zhou, B. Flexibility assessment and aggregation of alkaline electrolyzers considering dynamic process constraints for energy management of renewable power-to-hydrogen systems. Renew. Energy 2024, 235, 121261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, Y.; Qiu, Y.; Zhu, J.; Chen, S.; Zhou, B.; Li, J.; Yang, B.; Lin, J. Scheduling Multiple Industrial Electrolyzers in Renewable P2H Systems: A Coordinated Active-Reactive Power Management Method. IEEE Trans. Sustain. Energy 2025, 16, 201–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohebali Nejadian, M.; Ahmadi, P.; Houshfar, E. Comparative optimization study of three novel integrated hydrogen production systems with SOEC, PEM, and alkaline electrolyzer. Fuel 2023, 336, 126835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Z.; Chen, S.; Kong, X.; Ma, L.; Liu, X.; Lee, K.Y. A centralized EMPC scheme for PV-powered alkaline electrolyzer. Renew. Energy 2024, 229, 120688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, X.; Qian, Y.; Yang, S. Fluctuation Analysis of a Complementary Wind–Solar Energy System and Integration for Large Scale Hydrogen Production. ACS Sustain. Chem. Eng. 2020, 8, 7097–7110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.; Zhao, T.; Tang, S.; Wang, Y.; Ma, M. Research on design and multi-frequency scheduling optimization method for flexible green ammonia system. Energy Convers. Manag. 2024, 300, 117976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bicer, Y.; Dincer, I.; Vezina, G.; Raso, F. Impact Assessment and Environmental Evaluation of Various Ammonia Production Processes. Environ. Manag. 2017, 59, 842–855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salmon, N.; Bañares-Alcántara, R. Impact of grid connectivity on cost and location of green ammonia production: Australia as a case study. Energy Environ. Sci. 2021, 14, 6655–6671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmidt, O.; Gambhir, A.; Staffell, I.; Hawkes, A.; Nelson, J.; Few, S. Future cost and performance of water electrolysis: An expert elicitation study. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2017, 42, 30470–30492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hurtubia, B.; Sauma, E. Economic and environmental analysis of hydrogen production when complementing renewable energy generation with grid electricity. Appl. Energy 2021, 304, 117739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bouaboula, H.; Ouikhalfan, M.; Saadoune, I.; Chaouki, J.; Zaabout, A.; Belmabkhout, Y. Addressing sustainable energy intermittence for green ammonia production. Energy Rep. 2023, 9, 4507–4517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Indicator | Balanced Scheme | Steady-State Scheme | Following Scheme |

|---|---|---|---|

| Curtailed Energy (MWh) | 90.43 | 241.0 | 90.43 |

| Grid Electricity Usage (MWh) | 0 | 363.75 | 0 |

| Electrolyzer Power Consumption (MWh) | 3287.03 | 3480.83 | 3287.03 |

| Total Hydrogen Storage Throughput (104 Nm3) | 11.8 | 10.94 | 5.76 |

| Ammonia Production (t) | 338.9 | 358.64 | 338.9 |

| Unit Electricity Consumption Cost (CNY/t) | 2187.15 | 2702.72 | 2187.15 |

| Comprehensive Revenue (104 CNY) | 27.55 | 10.66 | 27.55 |

| Model solving time (s) | 1.96 | 1.79 | 1.74 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Zheng, Y.; Zhu, S.; Yang, D.; Li, J.; Rong, F.; Ji, X.; He, G. A Multi-Time Scale Optimal Dispatch Strategy for Green Ammonia Production Using Wind–Solar Hydrogen Under Renewable Energy Fluctuations. Energies 2025, 18, 6518. https://doi.org/10.3390/en18246518

Zheng Y, Zhu S, Yang D, Li J, Rong F, Ji X, He G. A Multi-Time Scale Optimal Dispatch Strategy for Green Ammonia Production Using Wind–Solar Hydrogen Under Renewable Energy Fluctuations. Energies. 2025; 18(24):6518. https://doi.org/10.3390/en18246518

Chicago/Turabian StyleZheng, Yong, Shaofei Zhu, Dexue Yang, Jianpeng Li, Fengwei Rong, Xu Ji, and Ge He. 2025. "A Multi-Time Scale Optimal Dispatch Strategy for Green Ammonia Production Using Wind–Solar Hydrogen Under Renewable Energy Fluctuations" Energies 18, no. 24: 6518. https://doi.org/10.3390/en18246518

APA StyleZheng, Y., Zhu, S., Yang, D., Li, J., Rong, F., Ji, X., & He, G. (2025). A Multi-Time Scale Optimal Dispatch Strategy for Green Ammonia Production Using Wind–Solar Hydrogen Under Renewable Energy Fluctuations. Energies, 18(24), 6518. https://doi.org/10.3390/en18246518