Pressurized Chemical Looping Flue Gas Polishing via Novel Integrated Heat Exchanger Reactor

Abstract

1. Introduction

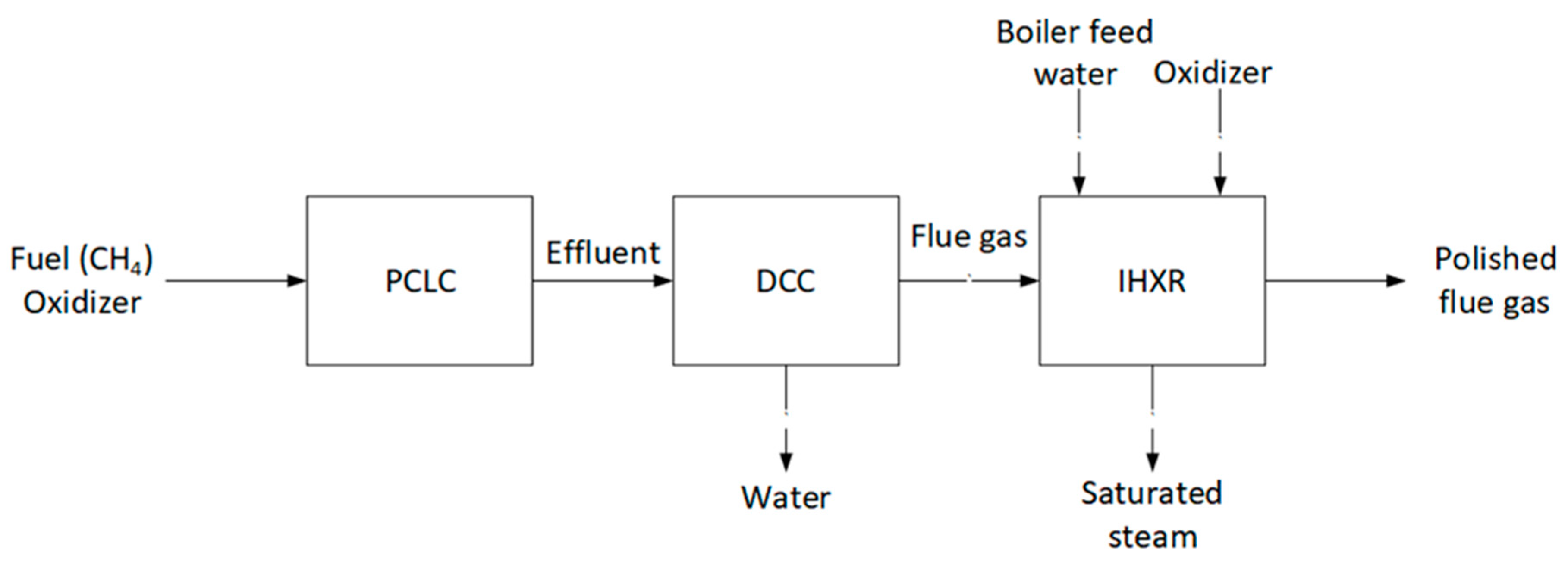

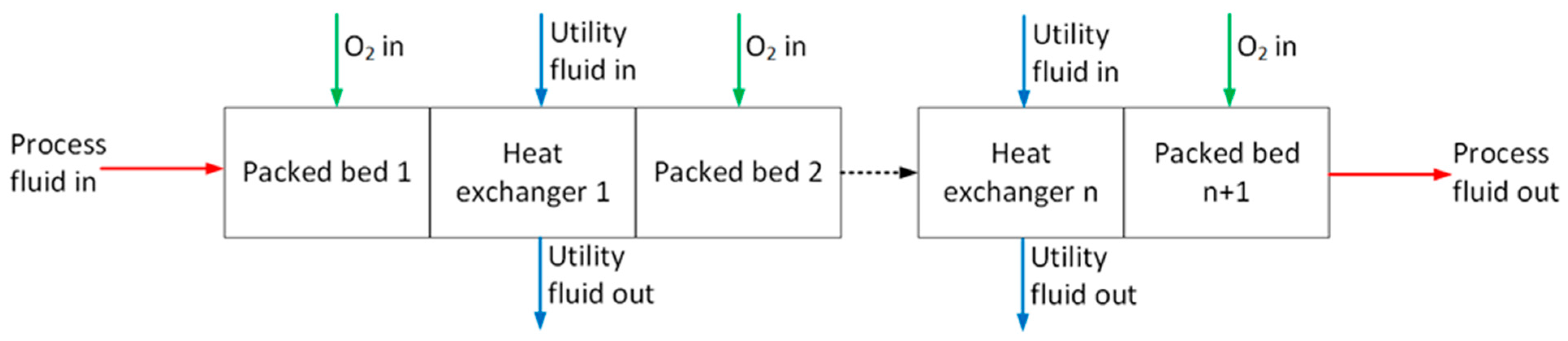

2. Process Description

3. Methodology

3.1. PCLC Flue Gas Composition

3.2. Gibbs Equilibrium Study

3.3. Kinetic Modelling Study

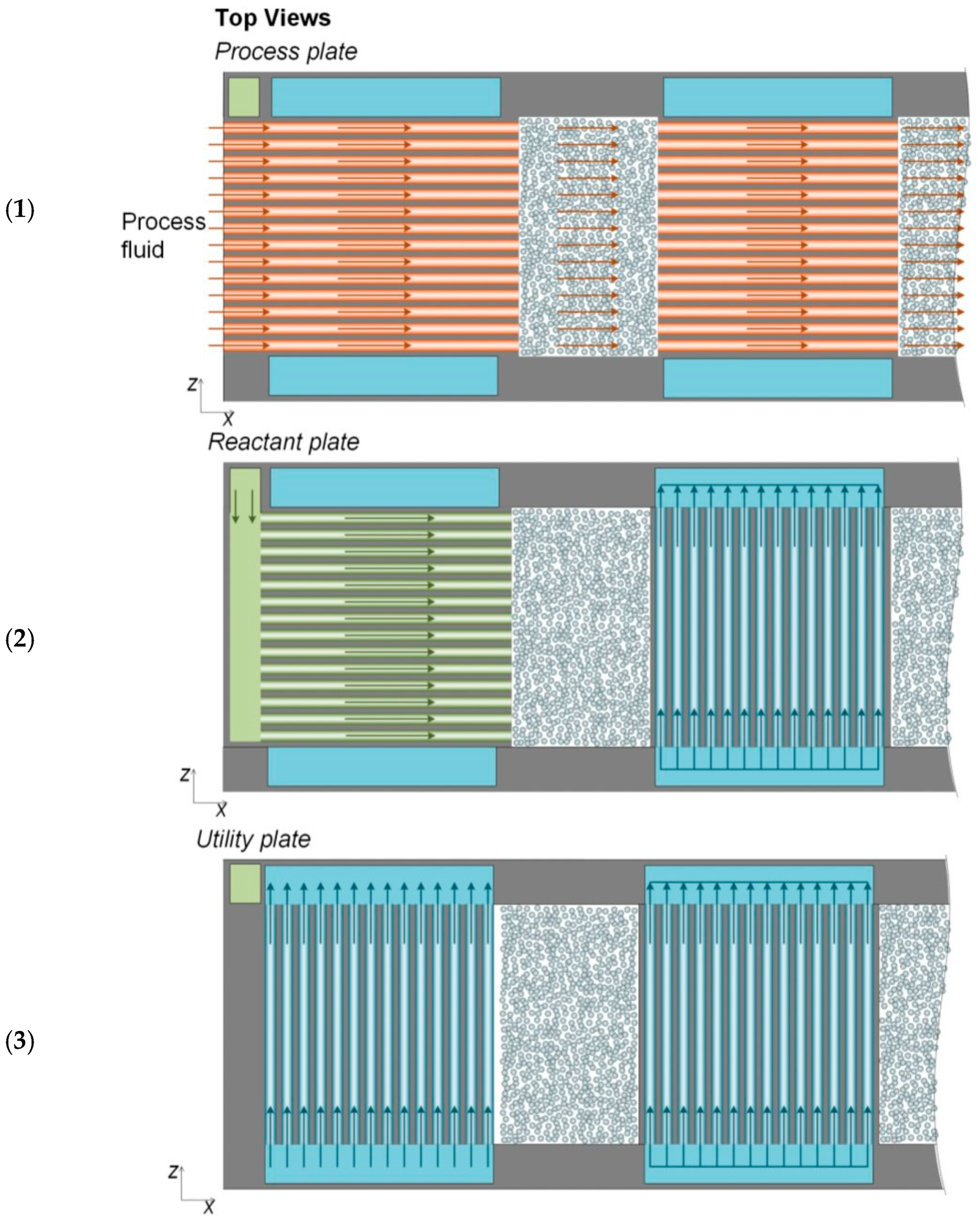

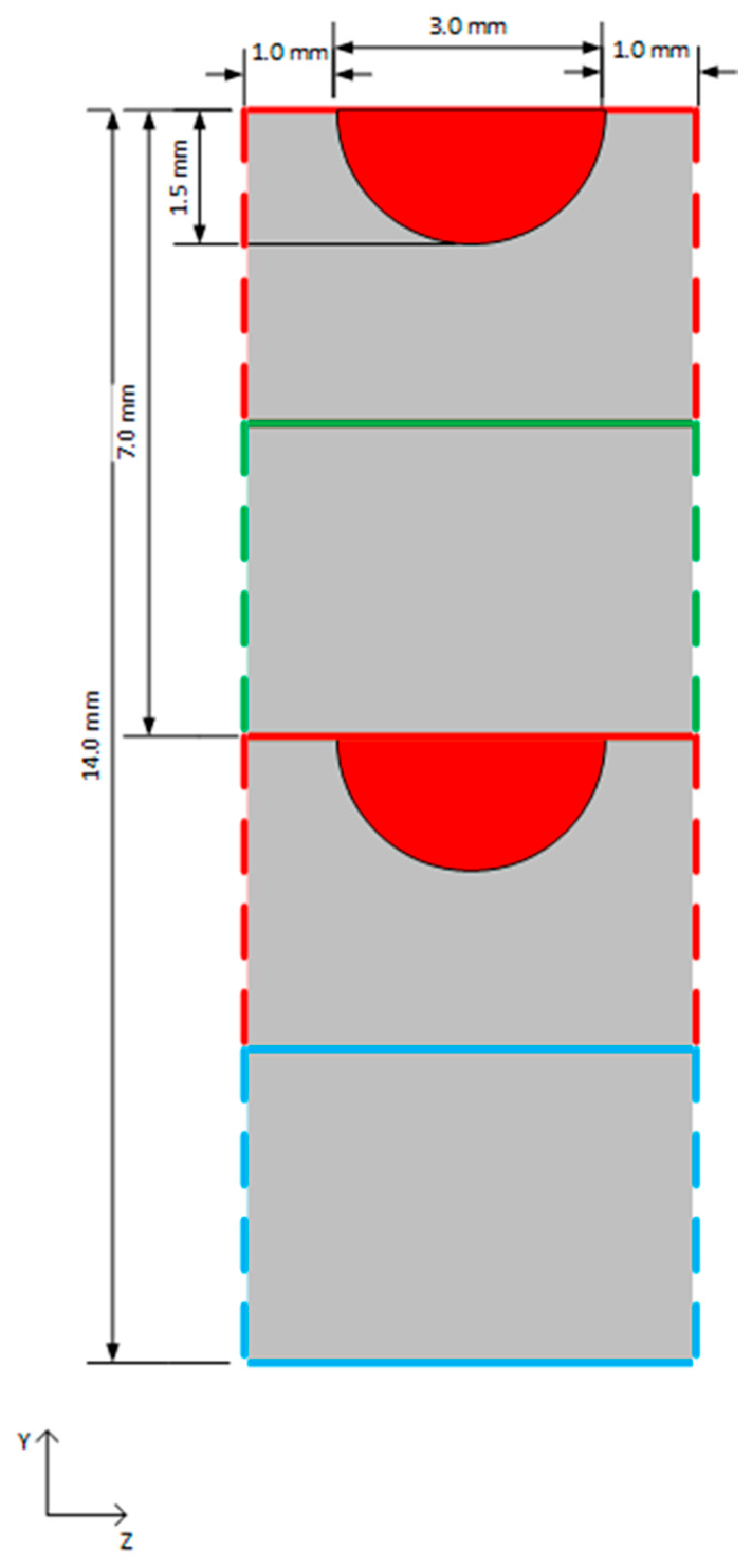

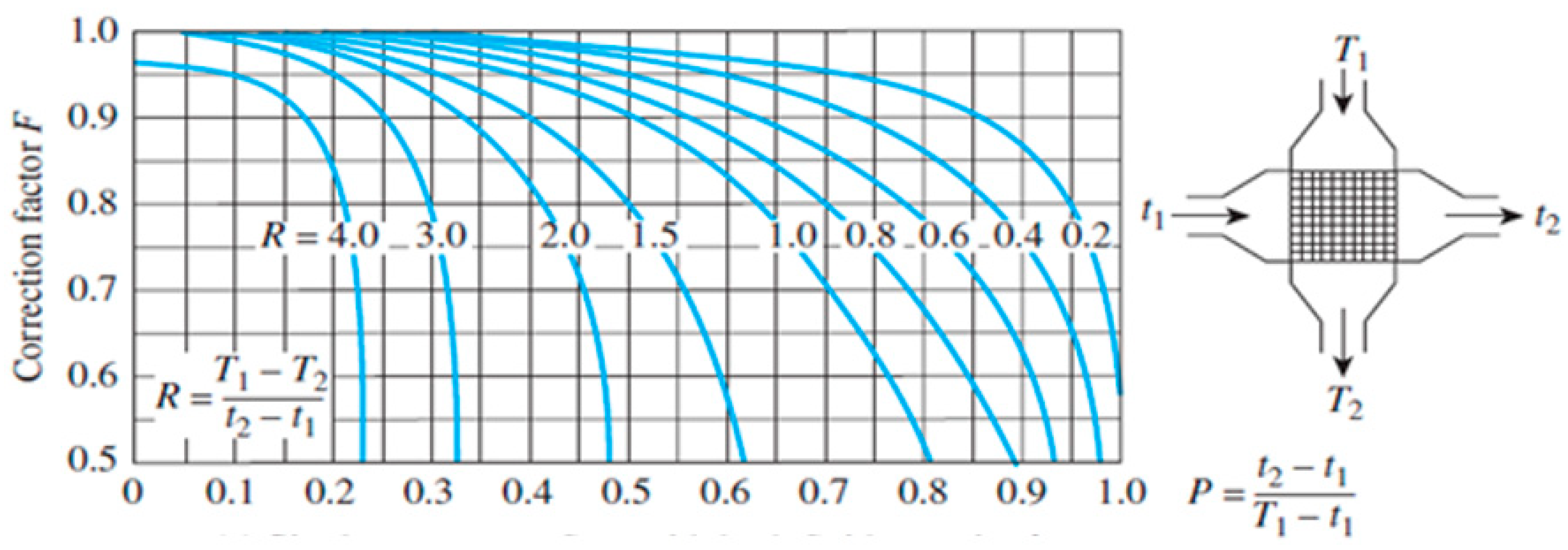

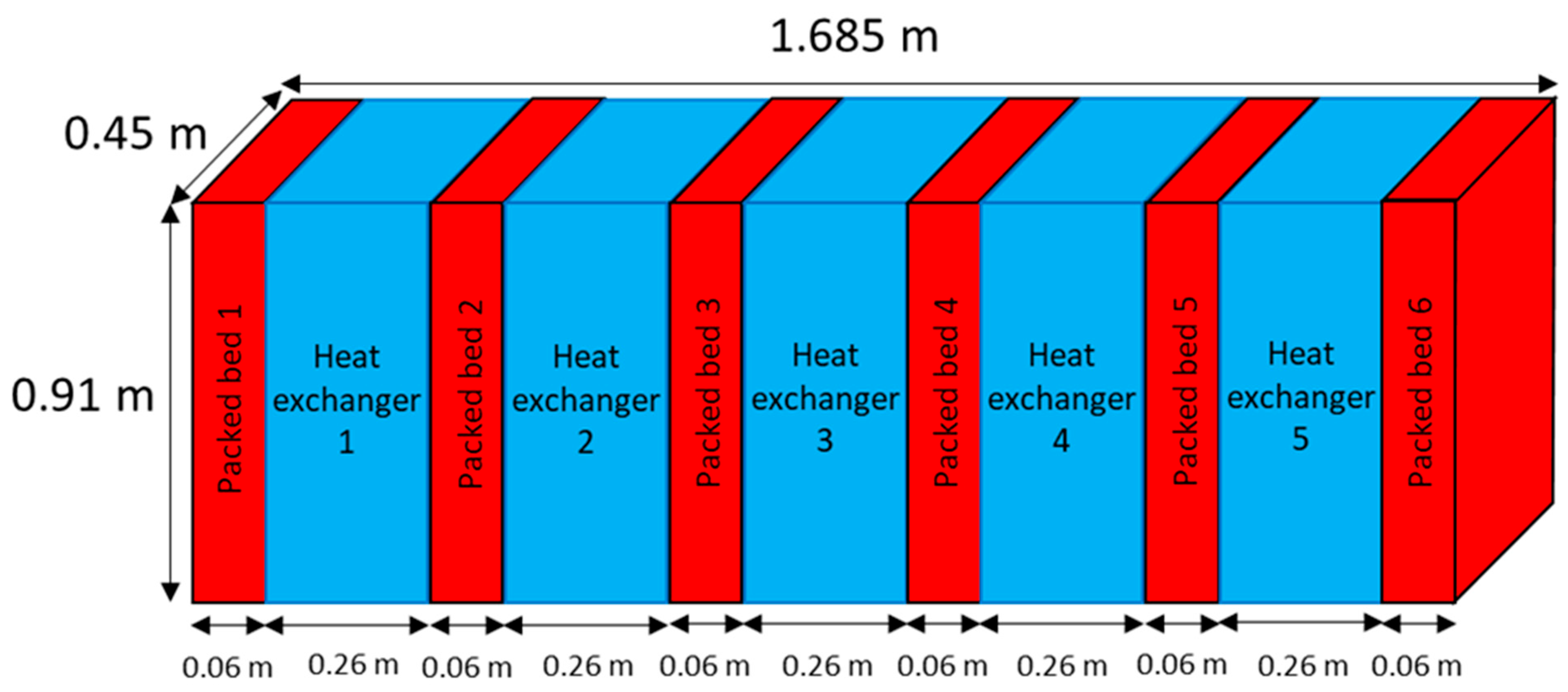

3.4. PCHE Design Study

3.4.1. Determination of Convective Heat Transfer Coefficients

3.4.2. Thermal Circuit Design

4. Results and Discussion

4.1. Outlet Composition and Number of Packed Beds

4.2. Required Packed Bed Section Length

4.3. Required Heat Exchanger Section Length

4.4. Final IHXR Design

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Nomenclature

| D | Flow channel diameter [m] |

| Dh | Flow channel hydraulic diameter [m] |

| f | Darcy friction factor [-] |

| G | Mass flux [kg/m2] |

| h | Convective heat transfer coefficient [W/(m2·K)] |

| k | Thermal conductivity [W/(m·K)] |

| L | Heat exchanger length [m] |

| Pr | Prandtl number = [-] |

| P | Pressure [kPa] |

| Q | Heat exchanger duty [W] |

| R | Thermal resistance [K/W] |

| ReD | Reynolds number in the flow channel = [-] |

| t | IHXR plate thickness [m] |

| T | Temperature [°C] |

| Dynamic viscosity [Pa·s] |

References

- Energy Innovation Program—Carbon Capture, Utilization and Storage RD&D Call. Available online: https://natural-resources.canada.ca/funding-partnerships/ccus-rdd-call (accessed on 28 April 2025).

- Furlong, A.J.; Bond, N.K.; Pegg, M.J.; Hughes, R.W. Evaluation of dust and gas explosion potential in chemical looping processes. J. Loss Prev. Process Ind. 2024, 89, 105277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ge, H.; Furlong, A.J.; Champagne, S.; Hughes, R.W.; Haelssig, J.B.; Macchi, A. Modelling and Design of a Novel Integrated Heat Exchange Reactor for Oxy-Fuel Combustion Flue Gas Deoxygenation. Energies 2024, 17, 1474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Enhance Energy Inc.; North West Redwater Partnership. Alberta Carbon Trunk Line Summary Report for 2014; Government of Alberta: Edmonton, AB, Cananda, 2014.

- Liu, H.; Liu, M.; Liu, S.; Tang, Y.; Liu, R.; Fei, J.; Zan, Y.; Zheng, R.; Huang, Y. Prediction of supercritical CO2 flow and heat transfer behaviors in zigzag-type printed circuit heat exchangers by improved POD-GABP reduced order model. Appl. Therm. Eng. 2025, 267, 125763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, J.H.; Kwon, J.G.; Kim, T.H.; Kim, M.H.; Cha, J.-E.; Jo, H. Experimental study of a straight channel printed circuit heat exchanger on supercritical CO2 near the critical point with water cooling. Int. J. Heat Mass Transf. 2020, 150, 119364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alain, A.E.; Ge, H.; Champagne, S.; Haelssig, J.; Macchi, A.; Hughes, R.W. Modelling of an intensified heat exchange reactor for flue gas polishing in a 600 kWth pressurized chemical looping pilot plant. In Proceedings of the 7th International Conference on Chemical Looping, Banff, AB, Canada, 29 September–2 October 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Halabi, M.; de Croon, M.; van der Schaff, J.; Cobden, P.; Schouten, J. Modeling and analysis of autothermal reforming of methane to hydrogen in a fixed bed reformer. Chem. Eng. J. 2008, 137, 568–578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, Y.-F.Y. The oxidation of CO and hydrocarbons over noble metal catalysts. J. Catal. 1984, 87, 152–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Methane. Available online: https://www.inchem.org/documents/icsc/icsc/eics0291.htm (accessed on 28 April 2025).

- Turton, R.; Shaeiwitz, J.A. Chemical Process Equipment Design; Prentice Hall: Boston, MA, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- He, L.; Fan, Y.; Bellettre, J.; Yue, J.; Luo, L. A review on catalytic methane combustion at low temperatures: Catalysts, mechanisms, reaction conditions and reactor designs. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2020, 119, 109589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gnielinski, V. New Equations for Heat and Mass Transfer in Turbulent Pipe and Channel Flow. Int. Chem. Eng. 1976, 16, 359–367. [Google Scholar]

- Hesselgreaves, J.E.; Law, R.; Reay, D.A. Compact Heat Exchangers: Selection, Design and Operation; Butterworth-Heinemann: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Le Pierres, R.; Southall, D.; Osborne, S. Impact of Mechanical Design Issues on Printed Circuit Heat Exchangers. In Proceedings of the SCO2 Power Cycle Symposium, Boulder, CO, USA, 24–25 May 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Material Properties: 316 Stainless. Available online: https://trc.nist.gov/cryogenics/materials/316Stainless/316Stainless_rev.htm (accessed on 20 August 2025).

- Cengel, Y.A.; Ghajar, A.J. Heat and Mass Transfer; McGraw-Hill Education: New York, NY, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

| Species | Requirement (mol%) |

|---|---|

| Minimum CO2 | 95 |

| Maximum CH4 | 1 |

| Maximum CO | 1 |

| Maximum H2 | 1 |

| Maximum O2 | 0.1 |

| Maximum N2 | 1 |

| Maximum Hydrocarbons | 2 |

| Maximum Inert (N2, Ar, CH4) | 4 |

| Species | Inlet Feed (kmol/h) | Species | Inlet Feed (kmol/h) |

|---|---|---|---|

| CH4 | 6.16 | CH4 | 12.32 |

| CO2 | 503.64 | CO2 | 497.48 |

| CO | 7.29 | CO | 7.29 |

| H2O | 17.19 | H2O | 17.19 |

| Hydrogen | 0.00 | Hydrogen | 0.00 |

| Oxygen | 0.00 | Oxygen | 0.00 |

| Nitrogen | 6.33 | Nitrogen | 6.33 |

| Flue gas flow rate | 22,955 kg/h |

| Reaction temperature/pressure | 350 °C/665 kPa |

| Reactor hydraulic diameter | 0.72 m |

| Properties of Pd/CeO2/Al2O3 catalyst | |

| Particle density | 4643 kgcat/m3cat |

| Particle diameter | 0.003 m |

| Bed void fraction | 0.55 |

| Activation energy | 62,760 kJ/kmol |

| Pre-exponential factor | 3.14 × 107 kmol CO2/m3cat·s·bar2 |

| m | 0.6 |

| n | 0.7 |

| Composition—Dry Basis (%) | Reactor 1 | Reactor 2 | Reactor 3 | Reactor 4 | Reactor 5 | Reactor 6 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Methane | 0.95 | 0.74 | 0.51 | 0.29 | 0.09 | 0.00 |

| CO2 | 96.52 | 96.80 | 97.08 | 97.39 | 97.89 | 98.79 |

| CO | 0.86 | 0.72 | 0.61 | 0.51 | 0.37 | 0.00 |

| Hydrogen | 0.39 | 0.38 | 0.37 | 0.34 | 0.27 | 0.00 |

| Oxygen | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| Nitrogen | 1.20 | 1.20 | 1.20 | 1.20 | 1.20 | 1.21 |

| Additional Info | ||||||

| O2 injection rate (kmol/h) | 2.66 | 2.66 | 2.66 | 2.66 | 2.66 | 2.66 |

| Outlet T (°C) | 397.1 | 394.1 | 393.3 | 393.3 | 394.0 | 399.7 |

| Composition—Dry Basis (%) | Reactor 1 | Reactor 2 | Reactor 3 | Reactor 4 | Reactor 5 | Reactor 6 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Methane | 1.72 | 1.27 | 0.87 | 0.48 | 0.14 | 0.00 |

| CO2 | 95.09 | 95.53 | 96.09 | 96.71 | 97.45 | 98.80 |

| CO | 1.39 | 1.34 | 1.18 | 0.98 | 0.70 | 0.00 |

| Hydrogen | 0.61 | 0.67 | 0.68 | 0.64 | 0.51 | 0.00 |

| Oxygen | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| Nitrogen | 1.19 | 1.19 | 1.19 | 1.19 | 1.19 | 1.20 |

| Additional Info | ||||||

| O2 injection rate (kmol/h) | 4.71 | 4.71 | 4.71 | 4.71 | 4.71 | 4.71 |

| Outlet T (°C) | 417.0 | 422.9 | 424.7 | 425.4 | 426.9 | 437.0 |

| Gibbs Reactor Inlet Conditions | Length (m) | O2 Injection (kmol/h) | Inlet CO (kmol/h) | Outlet CO (kmol/h) | Pressure Drop (kPa) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Base case | 0.06 | 0.98 | 1.96 | 0.00 | 7.11 |

| Upper limit case | 0.06 | 1.87 | 3.73 | 0.00 | 7.62 |

| CH4 Conversion | Exchanger Length (m) | Entrance Length (m) | Inlet Gas Temperature (°C) | Outlet Gas Temperature (°C) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 98.5 | 0.19 | 0.025 | 397 | 350.0 |

| 97 | 0.265 | 0.025 | 427 | 350.0 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Ge, H.; Perry, M.; Haelssig, J.; Macchi, A. Pressurized Chemical Looping Flue Gas Polishing via Novel Integrated Heat Exchanger Reactor. Energies 2025, 18, 6393. https://doi.org/10.3390/en18246393

Ge H, Perry M, Haelssig J, Macchi A. Pressurized Chemical Looping Flue Gas Polishing via Novel Integrated Heat Exchanger Reactor. Energies. 2025; 18(24):6393. https://doi.org/10.3390/en18246393

Chicago/Turabian StyleGe, Hongtian, Matthew Perry, Jan Haelssig, and Arturo Macchi. 2025. "Pressurized Chemical Looping Flue Gas Polishing via Novel Integrated Heat Exchanger Reactor" Energies 18, no. 24: 6393. https://doi.org/10.3390/en18246393

APA StyleGe, H., Perry, M., Haelssig, J., & Macchi, A. (2025). Pressurized Chemical Looping Flue Gas Polishing via Novel Integrated Heat Exchanger Reactor. Energies, 18(24), 6393. https://doi.org/10.3390/en18246393