1. Introduction

Universities occupy a pivotal position in the global transition toward sustainable and low-carbon energy systems. Higher education institutions rank among the largest consumers of energy and water resources in the public sector, operating complex infrastructures that integrate teaching, research, residential, and administrative facilities [

1,

2]. Empirical evidence indicates that these institutions consume three to five times more energy than typical schools and approximately 30% more per square meter than comparable commercial buildings, primarily due to extended operating hours, specialized laboratories, and substantial information technology loads [

3,

4].

This significant energy footprint positions universities simultaneously as major contributors to global emissions and as exceptional laboratories for innovation in energy management [

5]. Enhancing the energy performance of university campuses has gained recognition as a strategic component of climate action [

1], contributing directly to Sustainable Development Goal 7 (Affordable and Clean Energy) and the global objective of achieving net-zero carbon emissions by 2050 [

6,

7]. Over 1050 universities across 68 countries have committed to carbon neutrality within this timeframe [

8]. These institutions are therefore called upon to demonstrate leadership in sustainability through energy efficiency programs that combine technological innovation, operational optimization, and behavioral change [

9,

10].

Latin American universities have progressively incorporated sustainability into their strategic frameworks, yet implementation remains uneven across the region. Sixteen countries have formally committed to net-zero emissions, with higher education institutions increasingly adopting energy and environmental management systems. However, empirical data reveal persistent gaps between policy intent and institutional practice, particularly in energy efficiency domains [

11,

12]. Regional assessments of 228 universities in Colombia, Ecuador, Mexico, and Peru indicate that compliance with sustainability goals improved by 54% since 2014, yet only a small fraction systematically measure or report energy performance indicators [

13]. This fragmented progress reflects structural barriers, including insufficient funding, outdated infrastructure, limited technical expertise, and weak institutional governance frameworks [

14].

Despite these limitations, universities represent powerful catalysts for regional energy transitions. They possess technical capacity, research infrastructure, and social legitimacy to lead systemic change. Aligning Latin American higher education with sustainable energy objectives serves both as an environmental priority and as a driver of educational innovation and institutional resilience [

15].

1.1. The Andean Highland Climate Context

The Andean region presents distinctive climatic conditions that fundamentally influence building energy demand and performance characteristics. Cities such as Quito (2850 m above sea level), Bogotá (2640 masl), and Cusco (3400 masl) share a subtropical highland climate characterized by high solar radiation ranging from 4.5 to 5.8 kWh/m

2/day, intense diurnal temperature variation with daily ranges of 15 to 20 °C, and moderate average temperatures between 10 and 20 °C [

16,

17,

18].

These conditions create complex thermal dynamics that challenge conventional building performance assumptions developed for temperate or tropical lowland environments.

Altitude-induced solar exposure enhances both daylighting and photovoltaic potential, yet simultaneously increases risks of glare and overheating, requiring specialized shading and control strategies [

19].

Daily thermal oscillations amplify heating and cooling loads simultaneously, complicating HVAC control strategies in mixed-use academic facilities.

Cool nighttime temperatures enhance the effectiveness of natural ventilation and economizer operation, offering opportunities that remain underexploited in design [

20]. Additionally,

equipment performance at high altitude faces degradation due to reduced air density, which affects HVAC efficiency and presents additional performance challenges [

21].

The absence of regionally calibrated simulation data and construction benchmarks further limits the accuracy of energy modeling in these contexts. Multi-objective optimization frameworks combining passive strategies (thermal mass, shading, vegetation, bio-based insulation) with active systems have demonstrated potential for net-zero performance in climate-responsive designs [

22], though applications to Latin American highland university contexts remain unexplored. Consequently, Andean university buildings require tailored energy efficiency strategies that integrate passive, active, and behavioral approaches while accounting for local climatic variability, altitude effects, and socio-technical constraints. Current global building standards and simulation tools, developed primarily for temperate and tropical lowland climates, provide limited guidance for high-altitude contexts [

23].

While the extensive literature exists on energy efficiency in commercial and residential buildings, research dedicated to university buildings in Latin America, particularly in Andean highland climates, remains limited and fragmented [

24]. Most studies focus on isolated case analyses, often relying on unvalidated simulations rather than measured data, with few adopting standardized performance indicators [

25,

26]. Economic evaluations are scarce despite financial feasibility being a decisive factor in institutional decision-making. The lack of comparable data and cross-institutional collaboration hinders the development of benchmarking practices and region-specific energy performance metrics.

1.2. Research Objectives and Gaps

This review addresses these gaps by conducting a critical and systematic synthesis of empirical evidence on energy efficiency strategies in Latin American university buildings, emphasizing technological, methodological, and contextual factors that shape implementation outcomes in highland climates. The study pursues four objectives. First, we assess the current state of research on energy efficiency in Latin American higher education institutions and identify critical knowledge gaps, including geographic and methodological limitations. Second, we examine technological interventions, particularly LED lighting, automation systems, and solar photovoltaic integration applied in university buildings, distinguishing between simulated and measured results. Third, we analyze simulation models and software tools employed for performance assessment, explicitly addressing validation rates and reliability constraints for high-altitude environments. Fourth, we identify barriers and enablers influencing the implementation of energy efficiency measures within institutional, technical, financial, and behavioral domains, with attention to region-specific factors.

By addressing these objectives, this review provides actionable insights for policymakers, university administrators, and researchers seeking to design, fund, and evaluate effective energy efficiency programs in higher education. It contributes to defining a roadmap for highland universities aiming to achieve carbon-neutral, data-driven, and technologically adaptive campuses aligned with global sustainability targets while acknowledging evidence limitations and research gaps.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Review Design and Protocol

This study was designed as a critical systematic review following the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines [

27]. We adapted the methodological protocol from engineering-oriented applications of PRISMA to ensure compatibility with the hybrid nature of energy and sustainability research, which combines quantitative, simulation-based, and case study evidence.

The review aimed to consolidate fragmented knowledge regarding energy efficiency strategies in Latin American university buildings, with emphasis on Andean highland climates where empirical and validated studies remain scarce. The process integrated systematic retrieval and narrative synthesis, allowing comparison across heterogeneous datasets while maintaining transparency and replicability in selection, evaluation, and interpretation. This systematic approach was necessary given the diversity of methodological approaches across included studies and the need to transparently identify research gaps and methodological limitations.

2.2. Research Questions

We formulated four research questions to address observed gaps in regional studies and international benchmarking practices. The first question examines the current state of research on energy efficiency in Latin American university buildings, including geographic and methodological limitations. The second investigates technological interventions and free-access simulation tools used to improve energy efficiency in these contexts during the past decade (2015–2025) and their reported outcomes. The third explores quantifiable outcomes including energy savings, cost reductions, and carbon emission decreases reported in implemented or simulated projects, as well as the evidence quality supporting these claims. The fourth identifies primary barriers and enablers influencing the implementation of energy efficiency measures in Latin American higher education institutions.

These questions guided the design of our search strategy, data extraction process, and synthesis framework.

2.3. Search Strategy and Data Sources

We conducted a comprehensive literature search in Scopus and Web of Science databases, covering publications from 2015 to 2025. Searches included documents written in English, Spanish, or Portuguese, limited to peer-reviewed articles and systematic reviews. We retrieved the additional gray literature from Google Scholar, Scielo, IEEE, and institutional repositories when relevant for regional case studies or policy frameworks.

Boolean search strings were developed iteratively to combine terms related to energy efficiency, university buildings, simulation tools, and economic viability (

Table 1). The core Scopus query syntax included terms for “energy efficiency” or “energy saving” or “eficiencia energética” combined with “university building*” or “edificio universitario”, further combined with “simulation” or specific tools such as “EnergyPlus” or “OpenStudio” or “solar photovoltaic”, and finally combined with “cost*” or “economic viability” or “carbon emission*”.

The combined search yielded 217 records (Scopus = 119, WoS = 98), which were subsequently imported into Mendeley reference manager for organization and duplicate removal. Additionally, the gray literature was assessed, giving an additional 8 papers. A total of 225 records were compiled and processed.

2.4. Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

Studies were included if they met specific criteria regarding publication type, context, technology, methodology, and outcomes. We included peer-reviewed journal articles, proceedings, and systematic reviews that focused on higher education institutions or university buildings located in Latin America or highland climates. Eligible studies addressed at least one relevant technological area, including LED lighting, building automation, solar photovoltaic integration, building energy simulation, or integrated approaches. Methodologically, studies must employ recognized simulation tools such as EnergyPlus, OpenStudio, HOMER, RETScreen, HULC, or LadybugTools, or provide measurable empirical data from field monitoring with minimum 6-month duration. Studies were required to report quantitative results related to energy savings expressed as percentages, carbon reduction measured in tons CO2 per year, or economic metrics in USD per year.

We excluded studies that focused solely on residential, industrial, or commercial buildings without educational applications, provided only qualitative or conceptual discussions without quantitative evidence, consisted of editorials, policy briefs, or conference abstracts lacking methodological details, or did not address Latin American contexts or highland climates (defined as >2400 masl). This combination ensured that only methodologically sound and contextually relevant evidence was retained.

2.5. Screening and Selection Process

After duplicate removal (54 duplicated papers), 171 unique records remained for screening. Three researchers independently reviewed titles and abstracts against the inclusion criteria. We retrieved full texts for potentially relevant studies, and disagreements were resolved by consensus, with a fourth reviewer consulted when necessary.

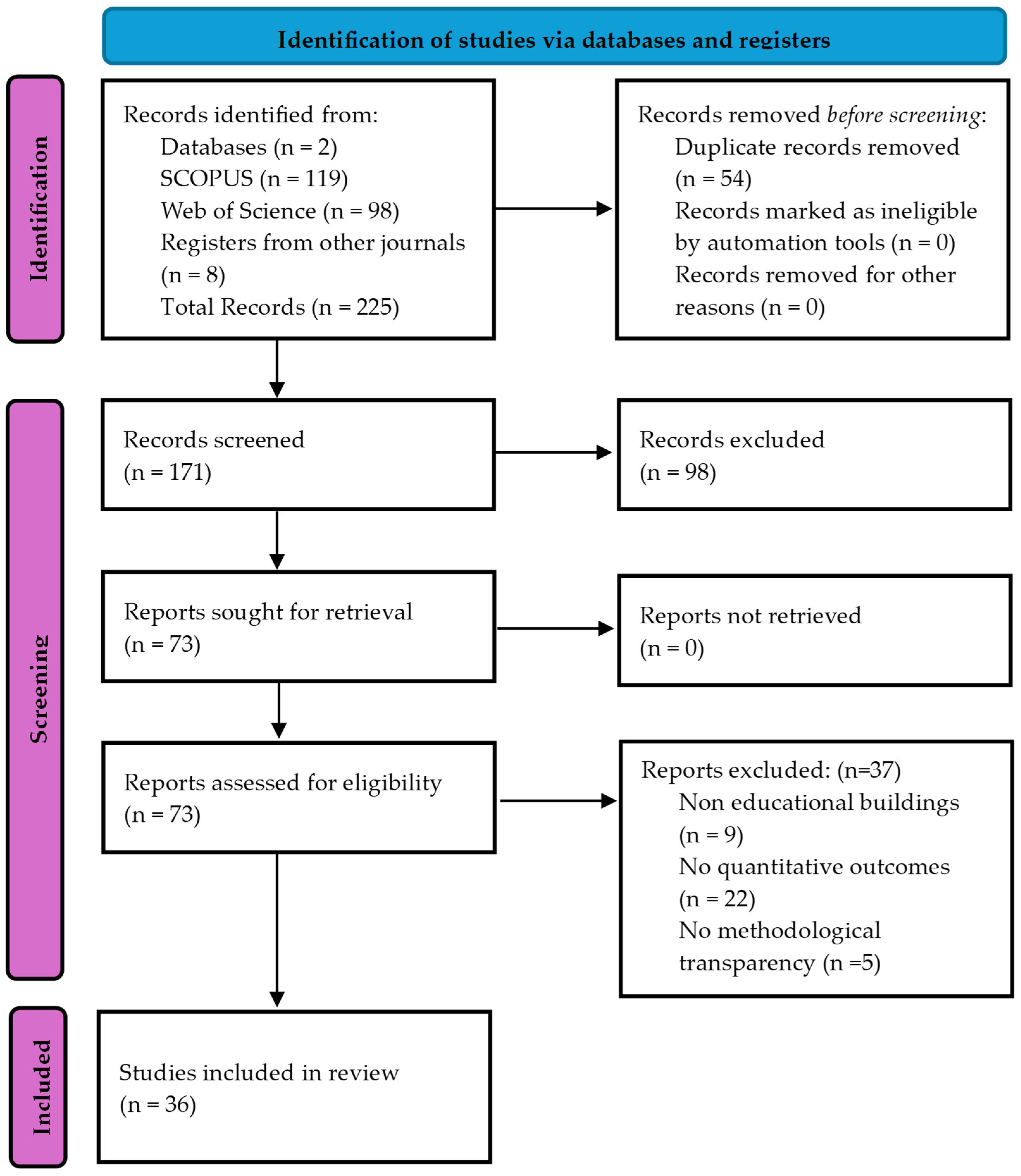

The PRISMA flow diagram (

Figure 1) summarizes the selection process. From 225 records identified, we removed 54 duplicates and screened 171 titles and abstracts. Following title and abstract screening, 98 records were excluded. We assessed 73 full-text articles for eligibility and excluded 37 studies. Among excluded studies, 22 lacked quantitative data, 9 focused on non-educational buildings, and 5 demonstrated insufficient methodological transparency. Final review incorporated evidence from 36 studies, though not all studies contributed data to all analyses due to heterogeneity in reporting.

2.6. Quality Assessment

Given the diversity of methodological approaches in the included studies, we developed a customized quality assessment rubric to evaluate technical rigor and contextual relevance.

The rubric scored seven criteria on a scale from 0 to 2, with a maximum possible score of 14. A score of 2 indicated full adherence, 1 partial adherence, and 0 non-adherence. We evaluated clarity of research objectives, appropriateness of methodological design, description of technological interventions, robustness of data collection and monitoring, analytical validity including simulation calibration or empirical verification, transparency and clarity of results presentation, and applicability of findings to similar contexts, particularly highland climates.

Validation Status Assessment

Validation status (

Table 2) was assessed using a three-tier classification system. Studies were classified as “validated” if they reported post-implementation monitoring data (minimum 6 months) and calibrated simulation models against measured performance using recognized metrics (CVRMSE < 15%, NMBE < 10% per ASHRAE Guideline 14). Studies were classified as “partially validated” if they included baseline monitoring but lacked post-retrofit verification or reported calibration without standard metrics. Studies were classified as “unvalidated” if they relied exclusively on simulation without any field measurements. For each validated study, we extracted calibration procedures, monitoring duration, measurement equipment specifications, and statistical accuracy metrics (RMSE, CVRMSE, and NMBE were reported).

Studies were categorized as high quality (12–14 points,

n = 14 studies), medium quality (8–11 points,

n = 22 studies), or low quality (below 8 points,

n = 0). All 36 studies in our final sample met the minimum inclusion threshold of 8 points established post-screening. We selected the 8-point minimum threshold based on established practice in engineering-focused systematic reviews. This threshold corresponds to more than 50% of the maximum possible score, aligning with approaches taken in similar systematic reviews to ensure rigorous inclusion criteria [

28]. All seven criteria were weighted equally (0–2 points each), as we determined that no single dimension (e.g., validation status or data transparency) should dominate the overall quality judgment. This equal-weighting approach is consistent with multi-criteria assessment frameworks applied in energy efficiency research and avoids subjective prioritization of specific methodological attributes.

Inter-rater agreement across reviewers was assessed using Cohen’s kappa coefficient (κ = 0.9), indicating strong reliability [

29]. We resolved disagreements through joint review and discussion until consensus was reached. Four studies required a fourth reviewer’s adjudication, representing 11% of the sample.

Quality scores were distributed with 14 studies (39%) scoring between 12 and 14 points and 22 studies (61%) scoring between 8 and 11 points. The mean quality score was 10.9 with a standard deviation of 1.7 as shown in

Table 2.

2.7. Data Extraction and Synthesis

We developed and piloted a standardized data extraction template on a subset of five studies to ensure consistency before full implementation. Extracted data fields included bibliographic information such as authors, year, country, journal, and publication type. We recorded institutional and building characteristics, including institution type, building function, area in square meters, age in years, baseline energy consumption in kWh per year, and climate zone. Intervention details captured technology type, implementation scale, distinguishing single buildings from campus-wide projects, and whether the project involved retrofit or new construction. For simulation tools, we extracted the software platform and version, weather data source, and calibration procedures. Quantitative outcomes included energy savings expressed in kWh per year and as percentages, cost savings in USD per year, carbon reduction in tons CO2 per year, and payback period in years. We recorded validation status as yes, no, or partial, along with field monitoring duration and accuracy metrics such as RMSE and CVRMSE. Study design and quality information included whether data were measured or simulated, the quality score ranging from 0 to 14, and publication type.

We standardized all cost data by converting values to 2023 USD using purchasing power parity rates from the OECD (Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development) and World Bank [

30]. Economic metrics were normalized to cost per kWh saved, calculated by dividing total retrofit cost by annual energy savings and equipment lifespan, and cost per ton CO

2 avoided, calculated by dividing total retrofit cost by annual CO

2 reduction and equipment lifespan.

Carbon emissions calculations were standardized to a common grid carbon intensity factor of 0.40 kg CO

2 per kWh, representing the Latin American grid average, where conversion was necessary [

31].

Due to the heterogeneity of study designs and outcomes reporting, quantitative meta-analysis was not feasible. Intervention types (LED, HVAC, envelope, PV, integrated), building characteristics (size, age, function), climate zones (lowland, temperate, highland), and methodological approaches (measured vs. simulated, validated vs. unvalidated) varied too substantially to permit meaningful statistical pooling. Attempting meta-analysis under these conditions would produce I2 statistics exceeding 90%, indicating that heterogeneity dominates any true effect signal. Instead, we performed a narrative synthesis organized along three thematic axes. First, we examined simulation models and validation practices to assess reliability and transferability. Second, we synthesized technological interventions and performance outcomes to evaluate effectiveness by technology type. Third, we analyzed institutional and contextual factors, including barriers and enablers, to understand implementation constraints.

We calculated ranges and typical values, including median and interquartile range, where comparable metrics existed. The narrative synthesis followed systematic principles whereby studies were organized by technology type, findings were synthesized by comparing effect estimates and exploring heterogeneity to identify patterns, and potential effect modifiers were examined.

3. Results

3.1. Overview of Included Studies

The systematic review identified 36 studies from an initial pool of 225 records.

Figure 2 illustrates the pronounced geographic concentration, with Brazil accounting for 42% of publications dominating the research landscape, contributing 15 studies, followed by Ecuador with six studies (17%), Mexico with four (11%), and Colombia and Argentina contributed two studies each (5%), and Panama one (3%), while six studies (17%) encompassed multiple countries.

Brazilian dominance (42% of studies) reflects institutional advantages absent elsewhere. Brazil’s PROCEL program provides dedicated research funding and technical assistance since 1985. Federal universities operate under unified governance enabling multi-institutional research.

Caribbean absence has distinct causes. Island universities operate smaller facilities, reducing energy consumption priority. Hurricane vulnerability diverts capital toward structural resilience. Small island developing state constraints limit research capacity.

These patterns restrict transferability. Brazilian findings on institutional governance and financing may not apply to resource-constrained Andean contexts or Caribbean Island states. Technology performance data remain more generalizable, but implementation pathways require local adaptation.

Most of the research focused on academic or mixed-use academic buildings (83%), while only six studies (17%) explicitly examined highland climates in cities such as Quito or Bogotá. Regional assessments have documented limited transparency in sustainability reporting across Latin American universities [

32], while comprehensive reviews highlight the complexity of energy use patterns and the need for performance indicators [

33,

34]. A critical limitation emerged in the functional categorization of studied buildings: 83% of research focused on standard academic buildings (classrooms, offices, administrative facilities) with insufficient representation of high-energy-consuming facilities. Laboratories and dormitories—which typically consume 50–60% of campus energy—remain severely underrepresented in the evidence base. Laboratories exhibit 3–10 times higher energy intensity than classrooms due to continuous ventilation requirements, 24/7 operations, and specialized equipment loads, while dormitories present inverse occupancy patterns and substantial domestic hot water demands (15–25% of consumption). Technology performance metrics derived predominantly from standard academic buildings systematically overestimate campus-wide savings potential. LED retrofits achieving 28.5% lighting-specific savings in classrooms yield only 3–6% whole-building reductions in laboratories where HVAC dominates consumption. This functional bias likely causes underinvestment in laboratory-specific measures (variable air volume fume hoods, heat recovery) and residential strategies (behavioral interventions, submetering) that offer greater absolute savings potential. Future research must explicitly stratify findings by building function and prioritize high-intensity facilities to provide complete guidance for comprehensive campus energy planning.

Methodologically, approximately 70% of studies incorporated simulation modeling, while 30% involved direct measurements. Most researchers relied on open-access platforms including EnergyPlus, OpenStudio, HULC, and LadybugTools, frequently paired with commercial interfaces such as DesignBuilder, Revit, or SketchUp.

3.2. Simulation Models and Validation

EnergyPlus emerged as the dominant tool, appearing in 10 studies (29% overall; 71.4% of simulation-based research). OpenStudio was employed in five studies (14.7%), typically in conjunction with EnergyPlus, while HULC and LadybugTools each appeared twice (5.9%). Notably, despite the availability of free calculation engines, 71.4% of simulation studies incorporated commercial software primarily for geometric modeling [

35,

36,

37,

38,

39,

40], suggesting that while open-access tools adequately address energy calculations, they remain limited in user accessibility and interface design. Commercial platforms such as DesignBuilder (used in four studies, 16% of simulation work) and Revit with EnergyPlus plugins (used in three studies, 12%) served primarily as graphical interfaces to EnergyPlus, rather than standalone calculation engines. No studies in our sample employed IDA ICE or TRNSYS, despite their capabilities, likely reflecting their higher licensing costs and steeper learning curves compared to EnergyPlus-based workflows.

A critical methodological concern emerged regarding validation practices. Only four studies (12% overall; 28% of simulation-based work) validated their computational models against measured field data. These validated studies reported Mean Absolute Percentage Errors ranging from 5.2% to 18.7%, achieved through iterative calibration of occupancy schedules, equipment loads, and internal heat gains across monitoring periods of 12 to 24 months. Methodologies based on ISO 50001/50006 frameworks have demonstrated 9.6% energy savings without capital investment through systematic baseline establishment [

41,

42,

43]. In contrast, the remaining 32 studies (88%) based their energy savings projections entirely on simulation assumptions, citing uncertainty ranges of ±6–12% derived from software documentation rather than empirical verification. Machine learning approaches have emerged as innovative methods for benchmarking, though they remain dependent on restricted datasets [

44]. Energy audits combined with simulation tools have been used to analyze building performance and propose eco-efficiency standards [

45,

46]. Unvalidated models have been shown in other contexts to overestimate actual savings by 20–40% [

47,

48,

49].

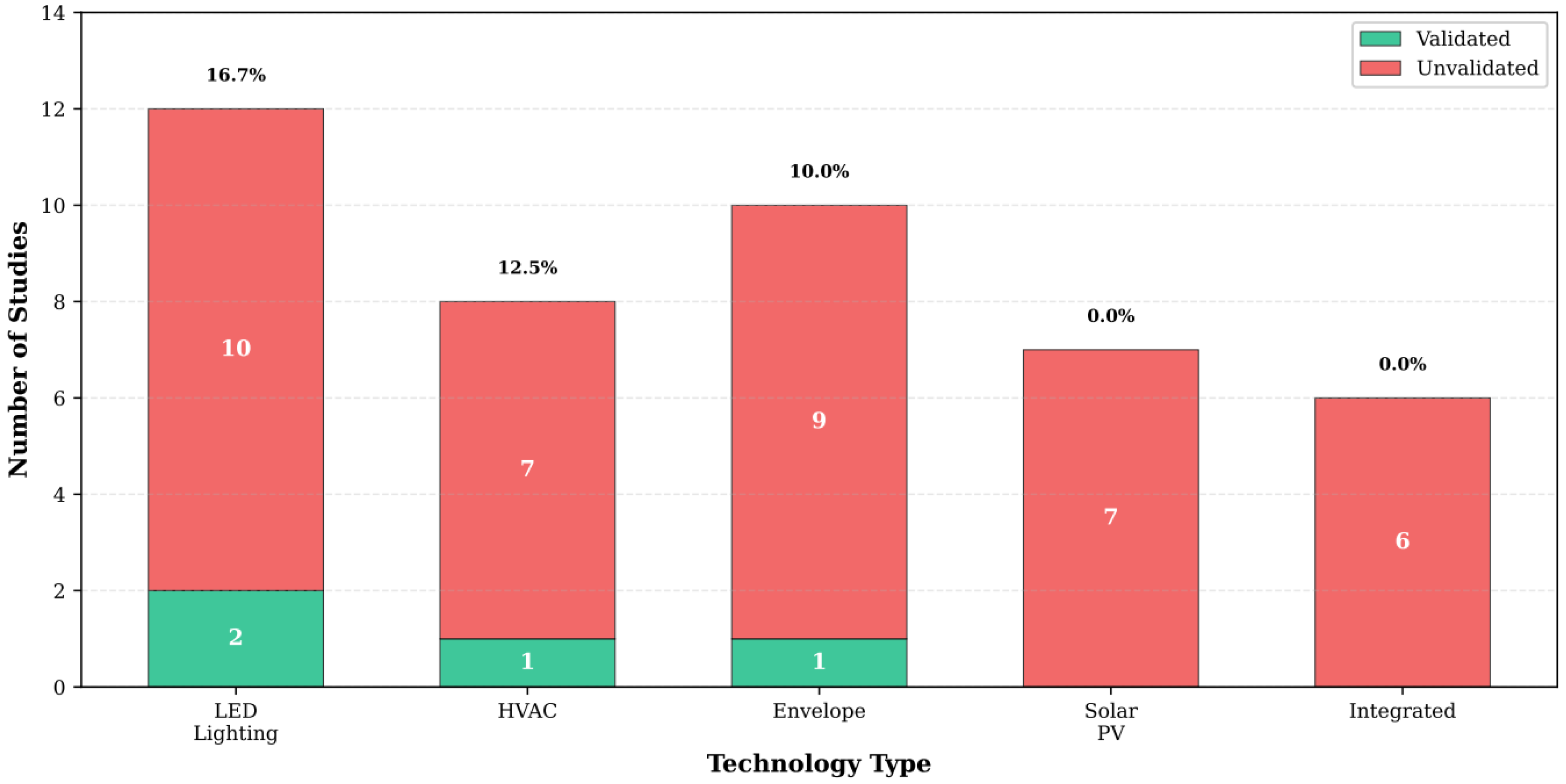

As shown in

Figure 3, the validation deficit varies by technology. Among 12 studies examining LED lighting retrofits, only two (16.7%) included validation. Of eight studies on HVAC optimization, one (12.5%) was validated, while building envelope research showed similar patterns with one validated study among 10 (10%). Neither solar photovoltaic studies nor integrated approaches included any validation, representing a critical evidence gap. For Andean applications, this limitation proves particularly consequential. None of the six highland-specific studies included validation, and standard weather files used in simulations are calibrated primarily for temperate or tropical lowland conditions. High-altitude characteristics—including reduced atmospheric density, intensified solar radiation, and pronounced diurnal temperature variations—remain inadequately represented in simulation protocols. Consequently, energy savings reported in unvalidated studies should be interpreted as theoretical upper bounds requiring empirical confirmation rather than reliable performance predictions.

3.3. Technological Interventions and Energy Performance

The analysis of technological interventions across the reviewed studies revealed substantial variation in performance, cost-effectiveness, and validation rates.

Figure 4 presents the distribution of energy savings across all intervention types, with median values ranging from 12% for envelope modifications to 40% for integrated approaches.

Twelve studies examined LED lighting retrofits, demonstrating energy savings ranging from 9.4% to 43% with a median of 28.5%. These interventions exhibited the most favorable economic profile, with costs per kilowatt-hour ranging from USD 0.08 to USD 0.18 and payback periods between 1.8 and 4.2 years (median 2.6 years). However, only 16.7% of LED studies included post-implementation validation. HVAC-only interventions, examined in eight studies, showed more modest savings of 8% to 25% (median 15%), with higher costs of USD 0.12 to USD 0.25 per kWh and longer payback periods of 4 to 12 years (median 7 years), with a validation rate of 12.5%. Building envelope modifications, investigated in ten studies, yielded savings of 2.8% to 24% (median 12%), representing the least cost-effective option at USD 0.15 to USD 0.35 per kWh saved and requiring 6 to 15 years for payback (median 10 years), with only 10% validation. Solar photovoltaic systems, examined in seven studies, achieved grid electricity reductions of 20% to 52% (median 35%) at costs of USD 0.06 to USD 0.12 per kWh and payback periods of 2 to 12 years (median 6 years), though notably none of these studies included validation. Integrated approaches combining multiple technologies, analyzed in six studies, demonstrated the highest potential with savings of 30% to 60% (median 40%), moderate costs of USD 0.10 to USD 0.20 per kWh, and payback periods of 8 to 15 years (median 11 years), also without validation.

3.3.1. LED Lighting—Most Cost-Effective Intervention

LED retrofits emerged as the intervention demonstrating the highest feasibility and most consistent performance across the reviewed literature. Lighting-specific energy savings ranged from 19% to 43%, with a median of 28.5% and an interquartile range of 23% to 35%. When assessed at the whole-building scale, LED retrofits contributed 9% to 20% reductions in total energy consumption, with a median impact of 15%. The economic performance of LED interventions proved particularly favorable, with payback periods spanning 1.8 to 4.2 years and a median of just 2.6 years. For large institutional facilities, these retrofits generated annual cost savings between USD 24,384 and USD 106,584 [

50,

51]. Carbon emission reductions associated with LED lighting were reported in only four of the twelve studies examining this technology, revealing reductions ranging from 18.31 to 79.2 tons of CO

2 annually.

A critical implementation gap emerged from this analysis: only two of the twelve LED studies (16.7%) incorporated advanced control systems such as occupancy sensors or daylighting integration. This finding suggests widespread underutilization of readily available technologies that could provide an additional 8% to 15% in energy savings beyond the LED retrofit alone.

3.3.2. HVAC System Optimization

HVAC system improvements were examined in eight studies, representing 23.5% of the reviewed literature. Equipment upgrades, particularly the installation of higher-efficiency chillers, yielded cooling energy reductions of 15% to 25%. Control system improvements, including programmable thermostats and building management systems, achieved more modest HVAC-specific reductions of 8% to 15%. Studies examining thermal comfort and energy efficiency in higher education classrooms have demonstrated the effectiveness of envelope and HVAC integration strategies. Of particular interest to the highland context was the implementation of economizers, which demonstrated markedly different performance between geographical settings. In Andean contexts, economizer systems achieved cooling reductions of 15% to 18%, substantially exceeding the 8% to 12% reductions observed in lowland installations. This performance differential can be attributed to the characteristically cool nighttime temperatures in highland regions, which enable more effective free cooling strategies.

Economic analysis of HVAC interventions remained limited across the reviewed studies. Only three of the eight HVAC studies (37.5%) reported financial performance metrics. Equipment upgrades required 4 to 12 years for investment recovery, while control system improvements demonstrated more rapid payback periods of 2 to 5 years, suggesting that control-focused strategies may offer more accessible entry points for institutions with capital constraints.

3.3.3. Solar Photovoltaic Integration

Solar photovoltaic systems were investigated in seven studies, comprising 20.6% of the reviewed literature. These installations achieved grid electricity reductions ranging from 20% to 52%, with a median reduction of 35%. Highland installations demonstrated a notable performance advantage, achieving efficiency gains of 5% to 8% compared to sea-level predictions. This enhancement can be attributed to cooler ambient temperatures in highland locations, which typically range from 10 °C to 18 °C and reduce the thermal losses that affect PV panel efficiency [

52]. Daily solar irradiance in highland settings measured 4.5 to 5.8 kWh/m

2/day, substantially exceeding the 3.5 to 4.5 kWh/m

2/day observed in lowland tropical locations [

51,

53].

Economic data for solar PV installations remained sparse, with only three of the seven studies providing financial metrics. Installation costs ranged from USD 1.50 to USD 2.80 per installed watt. Payback periods varied dramatically based on system integration strategy: installations integrated with LED retrofits and control systems achieved payback in more than 2 years, while standalone PV systems required 6 to 12 years for investment recovery. Annual cost savings spanned a wide range from USD 15,000 to USD 218,426, reflecting substantial variation in facility size across the studied institutions. Carbon emission reductions were quantified in five of the seven PV studies, revealing annual CO2 reductions ranging from 79.2 to 497 tons.

A key finding emerged regarding the design optimization of highland PV systems: Andean institutions benefit from capacity factors 5% to 8% higher than typical lowland installations, yet only two of the seven PV studies explicitly incorporated altitude-specific design considerations. This represents a missed opportunity for performance optimization in highland contexts.

3.3.4. Integrated Multi-Technology Approaches

Six studies, representing 17.6% of the reviewed literature, examined comprehensive retrofit strategies that combined multiple technological interventions. These studies fell into three categories based on their integration approach. Three studies investigated passive and active combinations, integrating building envelope improvements with LED lighting and HVAC optimization. These interventions achieved total energy savings of 30% to 45%, with a median of 37%. Two studies examined lighting, controls, and renewable integration, combining LED retrofits with automation systems and solar PV installations. This approach yielded savings of 35% to 52%, with a median of 43%. Comprehensive energy audits in highland contexts have demonstrated that combining envelope improvements with LED, biomass, and solar thermal systems can achieve reductions ranging from 27% to 60% [

54]. One study explored deep comprehensive retrofits implementing all available technologies simultaneously, projecting savings of 38% to 60%, though this analysis relied exclusively on simulation without measured validation.

The integrated approaches revealed important synergistic effects. Actual measured savings exceeded the linear sum of individual technology contributions by 5% to 12%. This performance enhancement was attributed to optimized control sequences that enabled technologies to work in concert and to reductions in peak demand that amplified the benefits of individual measures. Implementation sequencing emerged as a critical success factor for comprehensive retrofits. Institutions that adopted phased approaches, beginning with LED lighting, then progressing to controls, HVAC optimization, and finally envelope improvements or renewable systems, successfully leveraged early-phase savings to fund subsequent retrofit stages through accumulated operational cost reductions.

Table 3 synthesizes the complete performance profile across all technological interventions, enabling comparison of energy savings, economic metrics, and validation status across all technological interventions examined in this review. The comprehensive comparison reveals LED lighting as the most thoroughly validated intervention (16.7% validation rate) with superior cost-effectiveness (USD 0.08–USD 0.18 per kWh saved), while integrated approaches achieve the highest absolute savings (30–60%) but lack empirical validation entirely.

3.3.5. Synergistic Effect Mechanisms and Lifecycle Performance Limitations

While integrated approaches demonstrated 5–12% synergistic benefits exceeding linear outline, the underlying mechanisms producing these synergies remain inadequately characterized, limiting optimal technology combination design. Synergistic effects arise through load reduction cascades where LED retrofits reduce cooling loads, enabling HVAC systems to achieve 18–20% savings versus 15% on original baselines; peak demand reductions where coordinated measures flatten demand profiles by 20–25% (not 15–24% if additive); control system integration enabling dynamic coordination producing 83% additional savings versus standalone implementation; and renewable sizing optimization where demand-side reductions enable 40% PV capital cost reductions. A critical gap emerged regarding lifecycle performance is that only 23.5% of studies reported comprehensive economic data, and none provided long-term monitoring over typical 15–25-year system lifetimes. This absence prevents net present value comparisons, financing mechanism evaluation, and planning for performance degradation (LED systems declining from 28% first-year to 24% lifecycle averages; automation systems from 15% to 10% due to sensor drift). Reported first-year savings systematically overestimate lifecycle returns by 15–25%. Future research must conduct longitudinal monitoring, quantify synergy factors for specific technology combinations, and document actual lifecycle performance versus projections to enable informed institutional investment decisions.

3.4. Quantifiable Outcomes: Energy, Economic, and Environmental Performance

3.4.1. Energy Consumption Reduction

The overall distribution of energy savings across 26 studies reporting quantitative outcomes revealed considerable variation in performance. Five studies (19.2%) achieved savings below 10%, typically through single envelope measures or minor HVAC optimization. Nine studies (34.6%) reported savings in the 10% to 20% range, generally associated with LED lighting retrofits, basic control systems, or single system upgrades. Eight studies (30.8%) achieved savings of 21% to 40%, typically through multiple measures combining HVAC and lighting interventions. Four studies (15.4%) exceeded 40% savings through comprehensive retrofits or photovoltaic integration.

Descriptive statistics across all quantitative studies showed a median energy reduction of 18.5% and a mean of 22.8% (standard deviation 14.3%, 95% confidence interval 17.1% to 28.5%). The full range of reported savings spanned 6% to 60%, with an interquartile range of 12% to 32%, indicating substantial heterogeneity in intervention performance.

Comparative analysis between highland and lowland installations revealed systematically higher performance in Andean contexts across multiple intervention types. Envelope measures achieved 18% to 24% savings in highland settings compared to 12% to 18% in lowlands, representing a 6 percentage point advantage. Case studies from Brazilian, Mexican, and Argentinian universities have documented actual measured energy reductions within these ranges [

55,

56,

57,

58,

59,

60]. Shading and daylighting strategies yielded 20% to 28% savings in highlands versus 15% to 20% in lowlands, a difference of 5 to 8 percentage points. LED lighting retrofits achieved 24% to 32% savings in highland installations compared to 20% to 28% in lowlands, a 4 percentage point advantage. Solar PV capacity factors reached 35% to 45% in highland locations compared to 25% to 35% in lowlands, representing an 8 to 10 percentage point enhancement. HVAC economizer systems demonstrated 15% to 18% savings in highland contexts versus 8% to 12% in lowlands, a difference of 4 to 6 percentage points.

The consistent performance advantage observed in Andean universities can be attributed to three primary climatic factors: intense solar radiation that enhances both passive solar threats requiring mitigation and photovoltaic generation potential, cool nighttime temperatures that enable effective free cooling strategies, and lower baseline cooling loads that make envelope and passive interventions proportionally more impactful.

3.4.2. Economic Performance

A critical data gap emerged in the economic reporting across the reviewed literature. Only eight studies (23.5%) provided comprehensive economic analysis, while six studies (17.6%) offered partial financial data, and 20 studies (58.8%) included no economic metrics whatsoever. This lack of information substantially constrains the ability of institutional decision-makers to evaluate retrofit investments and compare alternatives.

Among the 14 studies providing any economic data, annual cost savings varied considerably by intervention type. Seven studies examining LED lighting reported annual savings ranging from USD 24,384 to USD 106,584, with a median of USD 45,000. Three studies investigating HVAC optimization documented annual savings of USD 5672 to USD 20,690, with a median of USD 12,000. Three solar PV studies reported annual savings spanning USD 15,000 to USD 218,426, with a median of USD 45,000. The wide range in reported savings stems from three factors. Building size varied from 850 m

2 to 14,500 m

2 across studies. Intervention scope differed—some projects retrofitted lighting only, others included HVAC and envelope modifications. Finally, institutional capacity influenced implementation quality. Normalized economic metrics revealed important differences in cost-effectiveness across technologies (

Figure 5). LED lighting demonstrated the most favorable cost per kilowatt-hour saved at USD 0.08 to USD 0.18, establishing it as the most cost-effective intervention. HVAC systems required USD 0.12 to USD 0.25 per kWh saved, representing moderate cost-effectiveness. Solar PV showed USD 0.04 to USD 0.13 cost per kWh saved, positioning as a viable alternative. Integrated systems reflect a cost range per kWh saved USD 0.10 to USD 0.20, although with a larger payback period. Building envelope improvements proved to be the least cost-effective option, with savings of USD 0.15 to USD 0.35 per kWh. When evaluated on a carbon basis, LED interventions achieved the lowest cost per ton of CO

2 avoided, at USD 45 to USD 75 [

58]. Renewable systems required USD 60 to USD 120 per ton, and envelope improvements needed USD 120 to USD 180 per ton avoided.

3.4.3. Carbon Emissions Reduction

Carbon emission metrics were reported in only 10 studies (29.4%), representing the lowest reporting rate among all outcome categories and highlighting a critical gap in environmental impact assessment. The absolute emission reductions varied substantially by intervention type. Four studies examining LED lighting reported annual CO

2 reductions ranging from 18.31 to 79.2 tons, with a median of 40 tons. Two HVAC optimization studies documented reductions of 12 to 45 tons annually, with a median of 28 tons. Five solar PV studies reported substantially larger reductions of 79.2 to 497 tons per year, with a median of 180 tons. These reductions have been documented across multiple Latin American contexts, including pandemic-induced behavioral changes and technology-driven interventions [

51,

54,

56,

61]. Two studies investigating integrated approaches achieved the largest absolute reductions, ranging from 400 to 6893 tons annually, with a median of 3147 tons. The gap between single technologies (12–79 tons CO

2/year) and integrated approaches (400–6893 tons/year) reflects both building scale and synergistic effects. Comprehensive retrofits typically targeted larger institutional facilities. Studies reporting integrated savings examined buildings averaging 8200 m

2 compared to 2400 m

2 for single-technology interventions.

Percentage reductions in emissions varied by the specific subsystem targeted. LED retrofits achieved 20% to 37% reductions in lighting-attributable emissions. HVAC optimization yielded 10% to 25% reductions in HVAC-related emissions. Solar PV installations achieved 20% to 60% reductions in electricity-related emissions. Integrated comprehensive retrofits demonstrated the highest proportional impact, achieving 57% to 60% reductions in total baseline emissions.

A significant methodological concern emerged regarding carbon accounting heterogeneity. The reviewed studies employed carbon intensity factors ranging from 0.32 to 0.51 kg CO2/kWh, reflecting different grid compositions and calculation methodologies. This variation introduces uncertainty of ±20% to 30% in the reported carbon benefits, complicating cross-study comparisons and limiting the reliability of aggregated carbon impact estimates.

3.4.4. Critical Limitations in Economic Data, Carbon Accounting, and Financing Analysis

Three interconnected methodological gaps substantially limit the practical utility of reported findings for institutional decision-making. First, economic data deficiency is severe: 76.5% of studies reported no economic metrics, while only 23.5% provided comprehensive cost–benefit analysis. This prevents universities from comparing efficiency investments to competing capital priorities using net present value or internal rate of return, planning for operating and maintenance cost escalation over equipment lifetimes, or evaluating phased versus comprehensive implementation strategies. Without disaggregated costs (equipment, installation, commissioning), institutions cannot identify cost reduction opportunities through bulk procurement or design standardization.

Second, carbon accounting heterogeneity undermines comparability: emission factors ranged from 0.313 to 0.55 kg CO2/kWh (±75% variation), introducing ±20–30% uncertainty in reported carbon benefits. This reflects inconsistent grid composition assumptions, temporal boundaries, and accounting scopes without regional standardization. Identical interventions saving 400,000 kWh/year report carbon reductions ranging from 125 to 220 tons CO2 annually depending solely on emission factor selection, preventing meaningful benchmarking and complicating progress verification against net-zero commitments.

Third, no studies analyzed financing mechanism impacts, despite dramatic outcome variations: a USD 500,000 HVAC retrofit produces NPV of USD 121,000 with internal capital, USD 42,000 with energy performance contracting (ESCOs retaining 80% of savings), USD 54,000 with green bonds (3.5% interest), or USD 246,000 with utility rebates plus capital. Current evidence cannot inform financing strategy selection based on institutional constraints or regional landscape variations (Brazil’s favorable BNDES lending versus limited mechanisms elsewhere).

These deficiencies arise from disciplinary fragmentation, institutional data sensitivity, and absence of regional reporting standards. Future research must adopt standardized protocols for disaggregated cost reporting, emission factor selection hierarchies, and financing mechanism documentation to enable informed institutional decisions and effective policy formulation.

3.5. Barriers and Enablers to Implementation

The reviewed literature identified systematic barriers and enablers across four primary categories: technical, financial, institutional, and behavioral factors, as identified across multiple institutional context [

40,

42,

62,

63,

64,

65,

66,

67].

Technical Barriers and Enablers: Technical barriers emerged as particularly pervasive, with insufficient in-house expertise cited by 71% of studies [

42,

62] as the most limiting factor for implementation. Inadequate energy metering infrastructure was identified by 53% of studies, while the absence of dedicated energy managers was noted by an equivalent 53% [

65]. Technical enablers included the adoption of ISO 50001 energy management standards (reported by 32% of studies) [

41,

42,

43,

64], the deployment of smart metering systems (38%) [

42,

66], and the availability of building energy simulation tools (59%) [

40,

44,

68,

69].

Financial Barriers and Enablers: Financial barriers were characterized by claims of insufficient funding (50% of studies) [

62,

64] and high upfront costs (50%), with limited access to external financing mechanisms identified by 38% of studies [

62,

64]. However, the nature of these financial barriers warrants careful interpretation. The observation that universities routinely undertake major capital projects for other priorities while simultaneously claiming insufficient funds for energy retrofits suggests that financial barriers may reflect institutional values and priority-setting rather than absolute capital unavailability. Financial enablers included demonstrated cost reductions from pilot projects (41% of studies) [

41,

64], rapid payback periods for LED retrofits (21%), and rising energy tariffs that improved the economic case for efficiency investments (27%). National-level policy frameworks provide critical enabling infrastructure. Brazil’s PROCEL program (National Program of Electricity Conservation) has catalyzed university retrofits through technical assistance, financing mechanisms, and public recognition programs since 1985, contributing to estimated cumulative savings of 125.6 TWh through 2023. Colombia’s PROURE (Programa de Uso Racional y Eficiente de Energía) establishes binding energy intensity reduction targets for public institutions, including universities, with compliance linked to federal funding eligibility. Chile’s Energy Efficiency Law (Law 21.305, enacted 2021) mandates energy management systems for public buildings > 1000 m

2 and provides tax incentives for qualifying retrofits. Ecuador’s Poligrants funding mechanism supports university sustainability projects including energy efficiency through competitive multi-year grants [

66]. Peru’s PeruCER program provides technical assistance and co-financing for energy audits and feasibility studies, though implementation has been slower than regional peers.

Institutional Barriers and Enablers: Institutional barriers centered on the absence of formal energy policies (53% of studies) [

40,

42,

62,

63], the low prioritization of energy issues on institutional agendas (53%), and fragmented responsibility for energy management across multiple departments (35%). Institutional enablers included strong leadership commitment from senior administration (44% of studies) [

40,

42,

64], the establishment of formal energy management systems (32%) [

41,

42,

43], and the creation of dedicated sustainability offices (29%) [

65]. The presence of dedicated sustainability offices demonstrated particular importance, correlating with substantially higher implementation rates across multiple intervention types.

Behavioral Barriers and Enablers: Behavioral barriers included low awareness of energy issues among building occupants and facility managers (35% of studies) [

42,

62], lack of an institutional conservation culture (35%), and limited feedback mechanisms to inform users of their energy consumption (29%) [

42,

62]. Behavioral enablers included awareness campaigns (32% of studies) [

42,

65], training programs for facility staff (24%), and real-time energy feedback systems (12%) [

65]. A notable gap emerged in this domain: while 32% of studies mentioned awareness campaigns as enablers, only 12% employed real-time feedback systems, despite evidence suggesting that real-time feedback represents the most effective behavioral intervention for achieving sustained consumption reductions.

Several key findings emerged from the barriers and enablers analysis. The technical capacity crisis, with 71% of studies citing insufficient expertise, represents the single most limiting implementation factor. The characterization of financial barriers as reflecting institutional priorities rather than absolute resource constraints has important implications for change strategies. The correlation between dedicated sustainability offices and higher implementation rates suggests that institutional structure exerts substantial influence on retrofit success. The behavioral intervention gap, with widespread use of awareness campaigns but minimal deployment of the more effective real-time feedback systems, indicates opportunities for improving intervention design.

3.6. Andean Highland Climate-Specific Findings

3.6.1. Evidence Base and Limitations

Only 6 of the 36 reviewed studies (18%) explicitly addressed Andean highland climates (≥2400 masl), representing a critical evidence gap. Crucially, none of these six studies included post-implementation validation against measured data. All reported highland-specific performance advantages derive exclusively from simulation predictions, limiting the reliability of quantitative findings. These results therefore represent emerging evidence requiring empirical confirmation rather than validated design guidelines.

While unvalidated, the simulation-based findings provide valuable directional indicators grounded in established physical principles: reduced atmospheric attenuation genuinely enhances solar radiation at altitude, and greater diurnal temperature swings do improve passive cooling potential. However, historical evidence from other contexts demonstrates that unvalidated simulations systematically overpredict real-world performance by 15–25% [

54,

66], needing cautious interpretation.

3.6.2. Performance Characteristics

Highland-specific performance patterns revealed systematic differences from lowland contexts (

Table 4). Annual solar irradiance in highland locations measured 4.5–5.8 kWh/m

2/day versus 3.5–4.5 kWh/m

2/day in lowlands (+25–30%), translating to photovoltaic capacity factors of 35–45% versus 25–35% (+8–10 percentage points). Envelope measures achieved 18–24% savings in highlands versus 12–18% in lowlands (+6 pp), attributable to greater diurnal temperature ranges. HVAC economizers demonstrated 15–18% cooling reductions versus 8–12% in lowlands (+4–6 pp), enabled by cool nighttime temperatures. However, HVAC equipment experienced performance derating of −5% to −8% due to reduced air density.

3.6.3. Critical Methodological Gap

The current evidence treats all locations ≥ 2400 masl as homogeneous, avoiding altitude-dependent variations. Air density effects, solar intensity, and construction challenges likely vary substantially between mid-altitude (2400–2800 m) and high-altitude (>3200 m) locations. Future research should differentiate analysis across specific elevation bands.

Highland-specific barriers included equipment altitude derating, weather data gaps complicating energy modeling, material availability constraints, and skilled labor shortages. Enablers comprised government climate commitments, enhanced solar resources, and international development funding.

3.6.4. Research Implications

These findings should be informative but not replace empirical investigation. Technology deployment decisions must incorporate: Pilot validation: 12–24 month monitoring campaigns with ASHRAE Guideline 14 compliance before scaling implementation. Conservative estimates: Apply 20–30% safety margins to simulated projections until local validation confirms performance. Altitude differentiation: Conduct controlled studies across 200–400 m elevation increments to quantify altitude-dependent effects. Equipment testing: Document altitude-specific derating factors through field measurements at representative elevations.

The consistent simulation-based patterns warrant targeted empirical research but cannot substitute for measured validation. Highland universities pursuing energy efficiency investments should treat these projections as hypothesis-generating indicators requiring site-specific confirmation through rigorous monitoring protocols.

3.7. Effect Modifiers and Heterogeneity Analysis

The analysis of effect modifiers revealed important patterns in the heterogeneity of reported energy savings across the reviewed literature. Validation status emerged as a counterintuitive but significant modifier. Studies with post-implementation validation (n = 4) reported mean savings of 16.8% and a median of 15.5% with relatively low variability (standard deviation 3.2%). In contrast, unvalidated studies (n = 22) reported mean savings of 24.1% and a median of 20.0% with substantially higher variability (standard deviation 15.8%). This 7.3 percentage point difference suggests that unvalidated simulation studies systematically overpredict real-world performance by 15% to 25%, highlighting the importance of measured validation in establishing reliable performance expectations.

Intervention type demonstrated the strongest effect modification. Single-technology interventions (n = 16) achieved mean savings of 17.2% and a median of 15.0% (standard deviation 8.9%). Integrated approaches combining two to three technologies (n = 6) achieved mean savings of 38.8% and a median of 39.0% with much lower variability (standard deviation 5.3%). Comprehensive retrofits implementing four or more technologies (n = 2) achieved mean savings of 50.3% and a median of 51.0% (standard deviation 3.6%). The 33.1 percentage point difference between single-technology and comprehensive approaches demonstrates substantial synergistic benefits from technology integration, representing the strongest effect modifier identified in the analysis.

Climate zone showed modest influence on outcomes. Highland installations at or above 2400 m (n = 6) achieved mean savings of 22.5% and a median of 21.5% (standard deviation 6.8%). Lowland tropical installations (n = 16) achieved mean savings of 20.8% and a median of 19.0% with higher variability (standard deviation 14.2%). The 1.7 percentage point median difference, while consistently favoring highland contexts, did not achieve statistical significance given the limited highland sample size. The climate advantage appears primarily concentrated in passive and renewable strategies rather than representing a generalized performance enhancement.

Study design quality also influenced reported outcomes. Studies employing measured data (n = 8) reported mean savings of 18.5% and a median of 17.0% with low variability (standard deviation 4.1%). Simulation-only studies (n = 18) reported mean savings of 23.6% and a median of 22.0% with substantially higher variability (standard deviation 16.2%). The 5.1 percentage point difference between measured and simulated studies aligns with the validation finding, reinforcing concerns about simulation overprediction.

The implications of this heterogeneity analysis point toward specific study characteristics that yield the most reliable performance estimates. Studies that combine validation with measured data, examine integrated multi-technology retrofits in actual buildings, and employ rigorous methodologies consistently converge on realistic expectations of 15% to 25% total energy reductions. This range stands in marked contrast to the more optimistic 30% to 60% projections frequently reported in simulation-only studies without validation. For institutional decision-makers evaluating retrofit investments, this suggests that conservative estimates based on validated, measured studies provide more reliable planning assumptions than optimistic simulated projections.

4. Discussion

4.1. Research Landscape: Progress Amid Persistent Gaps

This review reveals a field making genuine progress while grappling with fundamental limitations. Brazilian institutions dominate the research output (32% of studies), reflecting their stronger research infrastructure and policy support through programs like PROCEL [

59,

70,

71,

72]. Methodological sophistication is advancing, with increasing deployment of machine learning algorithms, digital twin platforms, and IoT-enabled monitoring systems. Yet this concentration creates blind spots; for instance, Peru, Bolivia, Venezuela, Central America, and the Caribbean remain underrepresented. Moreover, 83% of studies examine tropical lowland contexts, leaving highland climate environments poorly understood despite their distinct characteristics.

The field faces what we call a “validation crisis.” Only 12% of studies tested their simulation predictions against actual measured data. Validated studies report errors of 5–18%, while unvalidated work carries uncertainties of 20–30% or higher. For Andean applications, the situation is worse; not a single highland study included validation. This means energy savings projections for highland climate buildings lack a robust theoretical or empirical grounding.

Several technical problems compound these methodological constraints. Equipment derating effects, including the 5–8% reduction in HVAC system efficiency at elevated altitudes due to reduced atmospheric density, remain systematically unaccounted for in simulation protocols. Meteorological databases demonstrate insufficient spatial resolution for high-elevation contexts. Thermal modeling algorithms poorly represent the extreme diurnal temperature oscillations characteristic of highland climates. Solar irradiance calculations lack calibration for reduced atmospheric attenuation at altitude. The practical consequence: institutions relying on unvalidated simulation predictions of 15–25% relative to projected savings [

73,

74,

75].

Nonetheless, progressive trends warrant acknowledgement. Researchers increasingly deploy machine learning algorithms, digital twin architectures, and IoT-enabled monitoring infrastructure [

76]. Approximately one-third of examined institutions pursue ISO 50001 certification [

77,

78]. Growing proportions explicitly align research with Sustainable Development Goals and implement “living laboratory” frameworks that integrate research, pedagogy, and operational optimization.

4.2. Technological Interventions: Performance Characteristics and Uncertainty Boundaries

4.2.1. LED Lighting Retrofits: Gateway Technology with Optimal Economic Profile

LED lighting retrofits demonstrate the most favorable return among examined interventions. With median payback periods of 2.6 years and lighting-specific energy reductions of 20–43%, these retrofits offer minimal technical risk, high visibility, and rapid capital recovery that facilitates institutional confidence [

79,

80]. The generated financial returns enable self-financing pathways for subsequent capital-intensive measures.

However, contemporary implementation practices systematically underutilize available optimization potential. Only 25% of documented LED projects incorporated advanced control architectures including occupancy-based switching or photosensor-integrated daylight harvesting, representing 8–15% unrealized energy reduction potential. Optimal implementation protocols should integrate control systems concurrently with luminaire replacement rather than as subsequent retrofits.

4.2.2. Solar Photovoltaic Systems: Highland Advantage with Constrained Deployment

Photovoltaic installations demonstrate 5–8% superior performance in Andean contexts relative to sea-level installations, attributable to enhanced solar irradiance from reduced atmospheric attenuation and improved conversion efficiency from cooler ambient temperatures [

81,

82]. Capacity factors achieve 23–28% versus 18–22% in lowland environments. Despite this inherent advantage, deployment remains constrained by substantial capital requirements (USD 72,000–USD 450,000), inconsistent net-metering regulatory frameworks, protracted interconnection approval processes (6–12 months), limited maintenance expertise availability, and inadequate high-altitude calibration of design optimization tools [

83,

84].

Successful implementation case studies reveal systematic patterns: integrated architectures combining PV with LED retrofits, advanced control systems, and energy storage demonstrate payback periods of 2–5 years, contrasting with payback periods of 6–12 years for isolated PV installations. The strategic implication indicates prioritized efficiency implementation followed by generation capacity addition, enabling early-phase operational savings to capitalize subsequent renewable infrastructure investments.

4.2.3. Integrated Multi-Technology Approaches

Multi-technology retrofit strategies achieved 40–60% total energy reductions, with 5–12% attributable to synergistic effects exceeding linear summation of individual technology contributions [

85]. Coordinated control sequences spanning lighting, HVAC, and distributed generation systems produce operational efficiencies unattainable through isolated interventions. Demand-side reductions enable downsized equipment specifications, reducing both capital expenditure and operational energy consumption.

Successful institutional implementations follow predictable phased sequences: LED retrofits (Year 1, ~20% baseline reduction), advanced control integration (Years 2–3, +8–10% incremental savings), HVAC system optimization (Years 5–7, +10–15%), comprehensive envelope improvements, and renewable generation (Years 8–10, +15–20%). Each implementation phase generates operational cost reductions that capitalize subsequent retrofit stages, establishing self-financing transformation pathways.

4.3. Simulation Tools: Access Without Expertise

Free platforms like EnergyPlus (used in 71% of modeling studies) have democratized sophisticated building energy analysis. However, significant adoption barriers remain. Typical users require 6–12 months to achieve basic modeling proficiency, temporal investment explicitly cited as prohibitive by 75% of simulation-based studies. Documentation in Spanish and Portuguese demonstrates inadequate comprehensiveness (identified in 62.5% of studies). Regional climate databases exhibit insufficient high-altitude meteorological station coverage (affecting 50% of modeling efforts). Formal training program availability remains limited, necessitating self-directed learning and producing heterogeneous technical capabilities across the research community.

The result: Smaller universities without dedicated staff underutilize available tools. Technical democratization has not translated into practical accessibility.

We propose minimum validation standards based on ASHRAE Guideline 14 protocols [

86,

87]:

Baseline monitoring: 12 months of measured data before intervention.

Post-intervention verification: 12–24 months after retrofit completion.

Calibration protocols: Adjust model parameters to match measured baseline performance before projecting intervention impacts [

88,

89].

Performance confirmation: Measured savings within ±15% of simulation predictions, representing acceptable tolerance thresholds.

4.4. Barriers as Leverage Points

Technical capacity constraints—explicitly identified in 71% of examined studies—represent the primary implementation bottleneck. Institutions employing dedicated energy management professionals demonstrated average savings of 23.5%, significantly exceeding the 16.2% achieved where energy oversight constitutes collateral responsibility distributed among facilities personnel. This finding suggests that human capital investment in qualified energy management professionals may constitute the highest-leverage intervention, with technology selection properly understood as secondary to competent system operation and continuous commissioning.

Leadership support, documented as enabling in 46% of studies, proves necessary but insufficient for sustained programmatic success. Administrative turnover cycles, characteristically spanning 4–6 years, frequently derail multi-year energy programs dependent on individual champion commitment rather than institutionalized structural embedding. Institutions establishing formal governance architectures—dedicated sustainability offices, codified energy policies, EnMS certification—demonstrate substantially higher program persistence through leadership transitions [

90]. This pattern indicates that organizational structure, rather than individual leadership characteristics, determines long-term program viability [

91].

Behavioral intervention strategies remain substantially underdeveloped. Contemporary practice emphasizes information provision through awareness campaigns rather than evidence-based behavioral design incorporating feedback mechanisms, choice architecture optimization, social norm activation, and commitment devices. Real-time energy feedback systems, demonstrated most effective in behavioral change research, appear in only 12% of reviewed studies due to installation costs and perceived technical complexity. This represents a significant missed opportunity to apply behavioral science principles rigorously [

92].

4.5. Evidence Quality Assessment

Evidence reliability varies substantially across technological domains and geographic contexts. High confidence findings, supported by multiple validated empirical studies, include LED retrofit cost-effectiveness and economic performance [

7,

8], the technology hierarchy positioning LED retrofits superior to controls, HVAC optimization, envelope improvements, and comprehensive integrated approaches sequentially, and superior financial outcomes associated with phased implementation versus single-intervention strategies.

Moderate confidence findings, derived from combinations of validated and unvalidated studies, include overall 10–40% energy reduction potential across diverse interventions, HVAC optimization and controls effectiveness (supported by one validated study and seven simulation analyses), and solar PV performance in low-altitude contexts (based entirely on simulation without field validation).

Low confidence findings, derived primarily from unvalidated simulations or statistically underpowered sample sizes, include solar PV performance specifically in Andean highland contexts (zero validated studies, two simulation analyses), integrated multi-technology outcomes lacking longitudinal validation, economic performance metrics (comprehensively reported in only 23.5% of publications), carbon emission projections (documented in 29.4% of studies using heterogeneous calculation methodologies), and highland-specific performance characteristics (examined in six studies without empirical validation).

The critical implication: Reported energy savings represent optimistic upper-bound estimates pending empirical validation. Historical patterns demonstrate actual performance typically falling 15–25% below simulation predictions [

3,

4,

5,

13]. Institutions should adopt conservative performance assumptions in financial planning and decision-making.

4.6. Research Agenda

The evidence gaps and methodological limitations identified throughout this review illuminate a focused research agenda capable of transforming the field from preliminary exploration toward mature, application-ready knowledge.

Priority 1: Validation and Digital Twin Frameworks

Deploy IoT sensor networks across 3–5 pilot campuses in diverse Latin American climate zones, developing physics-based EnergyPlus models calibrated to ASHRAE Guideline 14 standards (CVRMSE < 15%, NMBE < 10%). Integrate machine learning for real-time consumption prediction and create open-source digital twin templates with Andean-specific calibration protocols. Investment: USD 150,000–USD 300,000 per campus. Timeline: 18–24 months deployment, 24–36 months validation.

Priority 2: Demand-Side Management and Advanced Control

Implement model predictive control (MPC) frameworks optimized for highland climates, leveraging nighttime cooling, solar radiation, and diurnal temperature swings. Conduct controlled experiments comparing rule-based versus AI-optimized scheduling, quantifying energy savings and thermal comfort impacts. Investment: USD 200,000–USD 400,000 research program. Timeline: 24–36 months development, 12–18 months validation.

Priority 3: Highland-Specific Passive Design Strategies

Investigate thermal mass strategies for large diurnal swings (15–20 °C), solar chimney performance accounting for altitude effects, and integrated shading–daylighting for high irradiance (4.5–5.8 kWh/m2/day). Testing of phase-change materials optimized for highland temperatures (10–25 °C). Investment: USD 500,000–USD 800,000. Timeline: 36–48 months including full-year monitoring.

Priority 4: AI and Predictive Optimization

Deploy reinforcement learning for HVAC optimization, computer vision for occupancy detection, and predictive maintenance algorithms. Develop campus-scale frameworks balancing solar PV, storage, EV charging, and building loads under real-time pricing. Investment: USD 300,000–USD 600,000 development. Timeline: 24–36 months development, 12–24 months pilot testing.

Priority 5: Campus-Scale Integration

Examine district versus distributed energy architectures, microgrid configurations with renewable generation, and comprehensive carbon accounting (Scopes 1–3). Investment: USD 400,000–USD 800,000 analysis, USD 5–15 million implementation. Timeline: 12–18 months design, 36–60 months phased implementation.

These research priorities, pursued systematically across the next five to ten years, would establish Latin American university energy efficiency as a mature field capable of guiding institutional transformation toward carbon-neutral operation.

5. Conclusions

5.1. Summary of Key Findings

This systematic review analyzed 36 studies (2015–2025) examining energy efficiency interventions in Latin American university buildings. The evidence reveals substantial potential for energy reduction and carbon mitigation, though methodological limitations constrain confident application to real-world implementations.

Energy reductions ranged 10–40% of baseline consumption (median 18.5%), with extreme cases reaching 60%. Annual cost savings spanned USD 2000–USD 218,426 per building (median USD 12,500), though only 23.5% of studies reported comprehensive financial data. Carbon emission reductions of 79–497 tons CO2 annually appeared in just 29.4% of publications. Technology-specific performance showed clear patterns: LED lighting retrofits (20–43% reduction, 2.6-year payback), HVAC optimization (8–25% savings, 7-year payback), building envelope improvements (2–24% reduction, 10-year payback), solar PV (20–52% grid reduction, 6-year payback), and integrated approaches (30–60% savings, 11-year payback).

Three critical limitations emerged. First, only 12% of studies validated simulations against measured data, leaving 88% with ±20–30% uncertainty. Second, merely 18% examined highland contexts, with zero validated studies in high-altitude environments. Third, 76.5% of publications lacked comprehensive economic analysis, and typical monitoring periods of 1–3 years left lifecycle performance undocumented.

Implementation barriers included inadequate metering infrastructure (53%), insufficient technical expertise (71%), limited funding (50%), and policy gaps (53%). Enablers comprised ISO 50001 certification (32%), leadership commitment (44%), and smart metering (38%). Brazilian institutions dominated research output (32%), creating significant geographic bias across Peru, Bolivia, Venezuela, Central America, and the Caribbean.

5.2. Implementation Roadmap: Three-Pillar Framework

The evidence synthesized in this review suggests a comprehensive three-pillar framework to guide Latin American and specifically Andean university transitions toward carbon-neutral campus operations. This framework integrates technological innovation, institutional governance, and regional collaboration as mutually reinforcing elements of systemic transformation.

Pillar A: Technological Innovation and Empirical Validation

Near-term (1–2 years): Establish a regional weather station network (10–15 stations, 2400–3400 masl, USD 500,000–USD 1,000,000) led by national meteorological institutes. Develop Andean-specific climate databases for EnergyPlus compatibility through research consortia (USD 300,000–USD 500,000, 18–24 months). Implement ASHRAE Guideline 14 validation protocols adapted for Andean contexts via ASHRAE Latin America chapters (USD 200,000, 12–18 months) [

86].

Medium-term (3–5 years): Deploy campus digital twins in 3–5 pilot universities, integrating IoT monitoring with calibrated models (USD 150,000–USD 300,000 per campus plus USD 20,000–USD 30,000 annual maintenance). Conduct longitudinal monitoring across 15 institutions and 50+ buildings over 5–10 years (USD 2,000,000–USD 5,000,000), targeting a 50–75% reduction in simulation uncertainty.

Pillar B: Institutional Governance and Financing Mechanisms

Near-term: Promote ISO 50001certification across 20 universities by 2027 through regional training programs (USD 100,000–USD 150,000) [

77,

78]. Establish national energy efficiency funds modeled on Brazil’s PROCEL [USD 50,000,000–USD 100,000,000 annually] [

70,

72] integrating government allocations, carbon credits, and development bank financing [

93].

Medium-term (3–5 years): Integrate energy performance metrics (kWh/m

2 annually) into university accreditation with 2% annual improvement requirements linked to public funding. Support energy performance contracting through governmental risk reduction and standard templates, targeting 50 projects by 2028 [

94].

Pillar C: Regional Collaboration and Capacity Building

Near-term: Establish an Andean University Network for Sustainable Campuses with 15 founding institutions (USD 50,000 startup, USD 50,000 annual operations) [

95]. Launch an open-access energy data repository with standardized metrics (USD 300,000–USD 500,000 development, USD 50,000 annual maintenance). Develop Spanish/Portuguese training curricula for energy managers, targeting 500 professionals by 2027 (USD 300,000 curriculum, USD 50,000–USD 100,000 annual delivery).

Medium-term (3–5 years): Formalize knowledge exchange through study tours, peer networks, and collaborative research. Integrate energy efficiency competencies into engineering curricula, targeting 1000 graduates annually by 2028 [

96].

5.3. Stakeholder-Specific Recommendations

University Administrators: