Research on the Alternating Current Properties of Cellulose–Innovative Bio-Oil Nanocomposite as the Fundamental Component of Power Transformer Insulation—Determination of Nanodroplet Dimensions and the Distances Between Them

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

3. Fundamentals of the Quantum-Mechanical Phenomenon of Electron Tunnelling in a Pressboard–Bio-Oil–Water Nanodroplet Nanocomposite

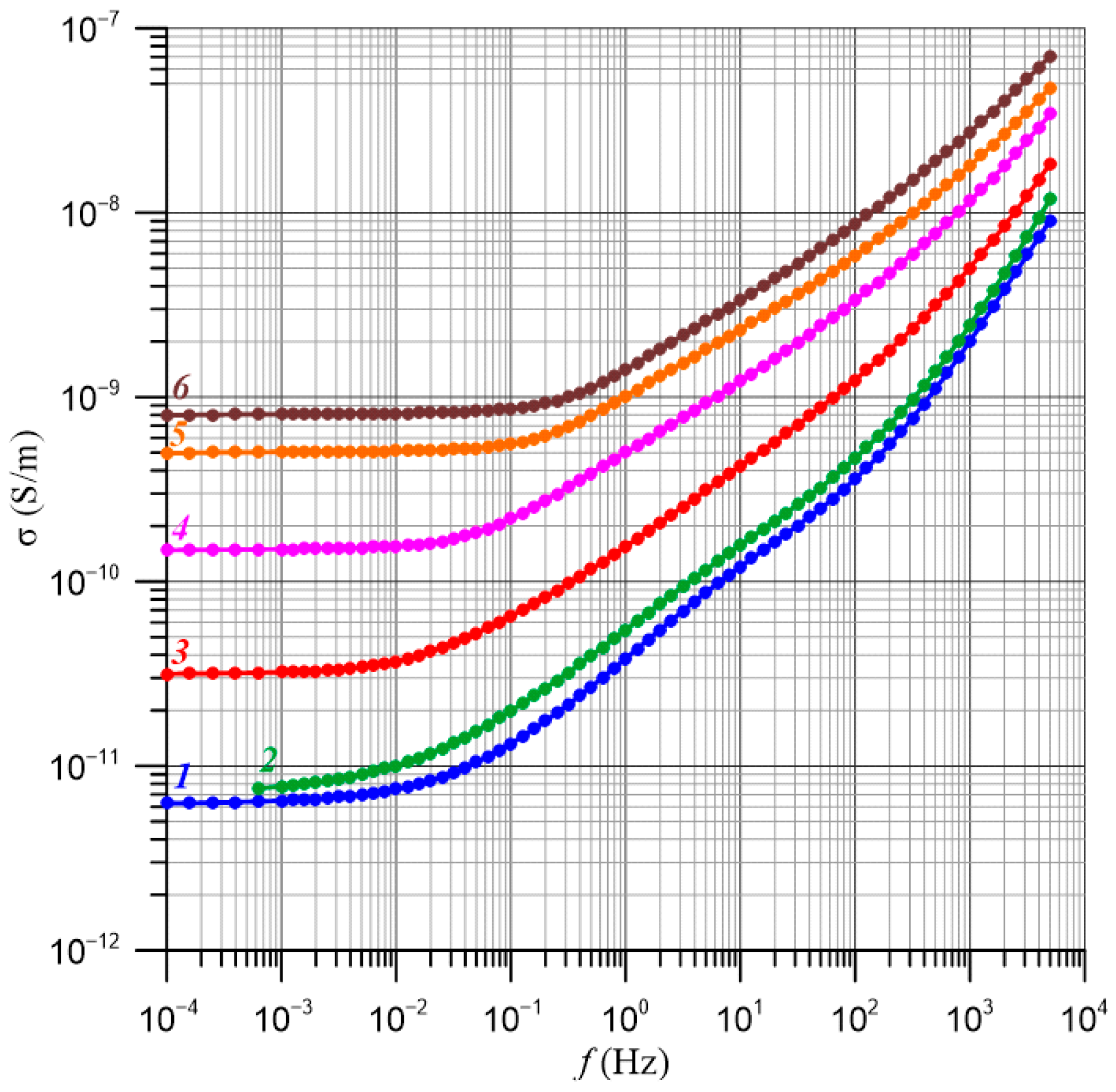

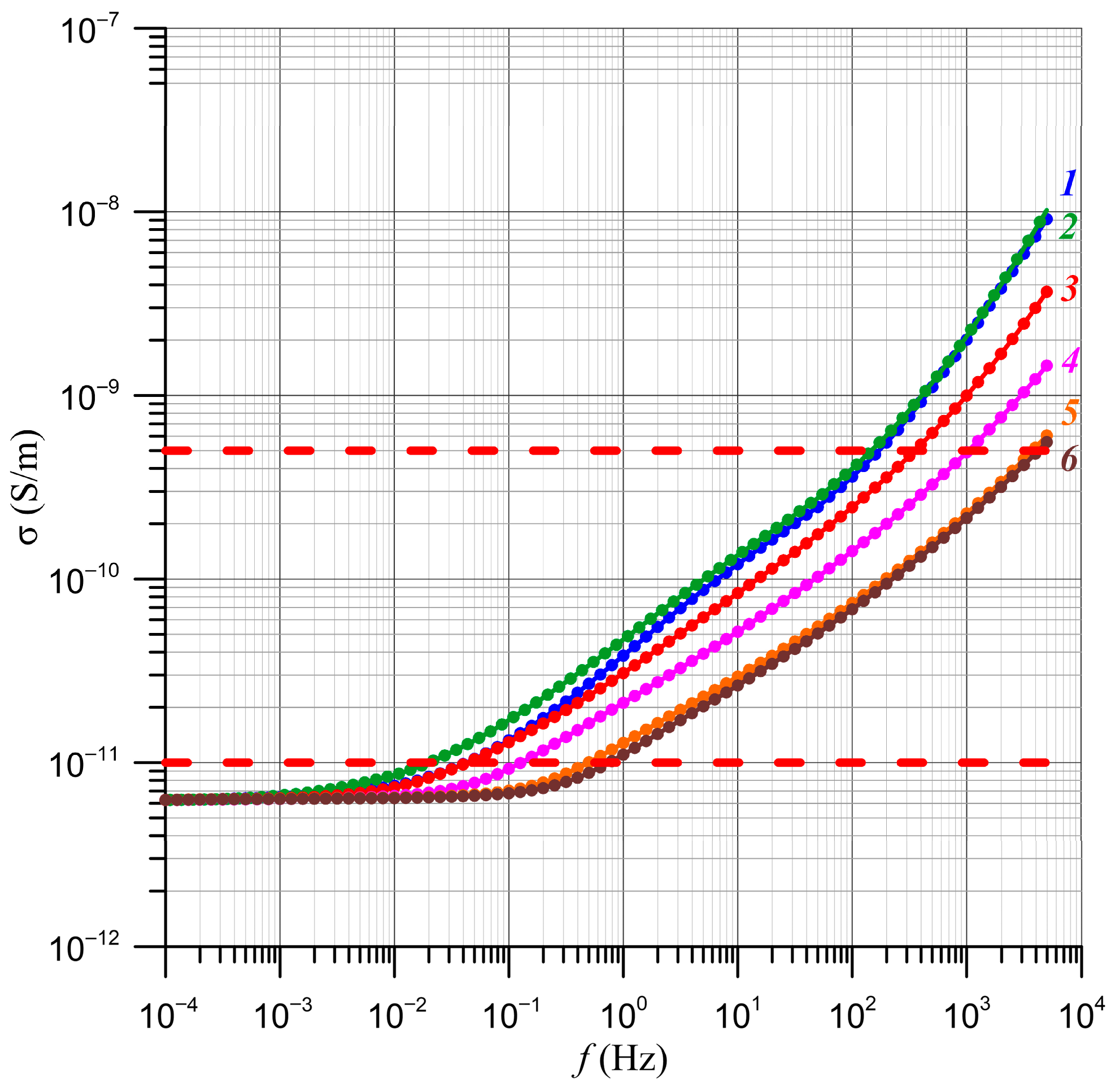

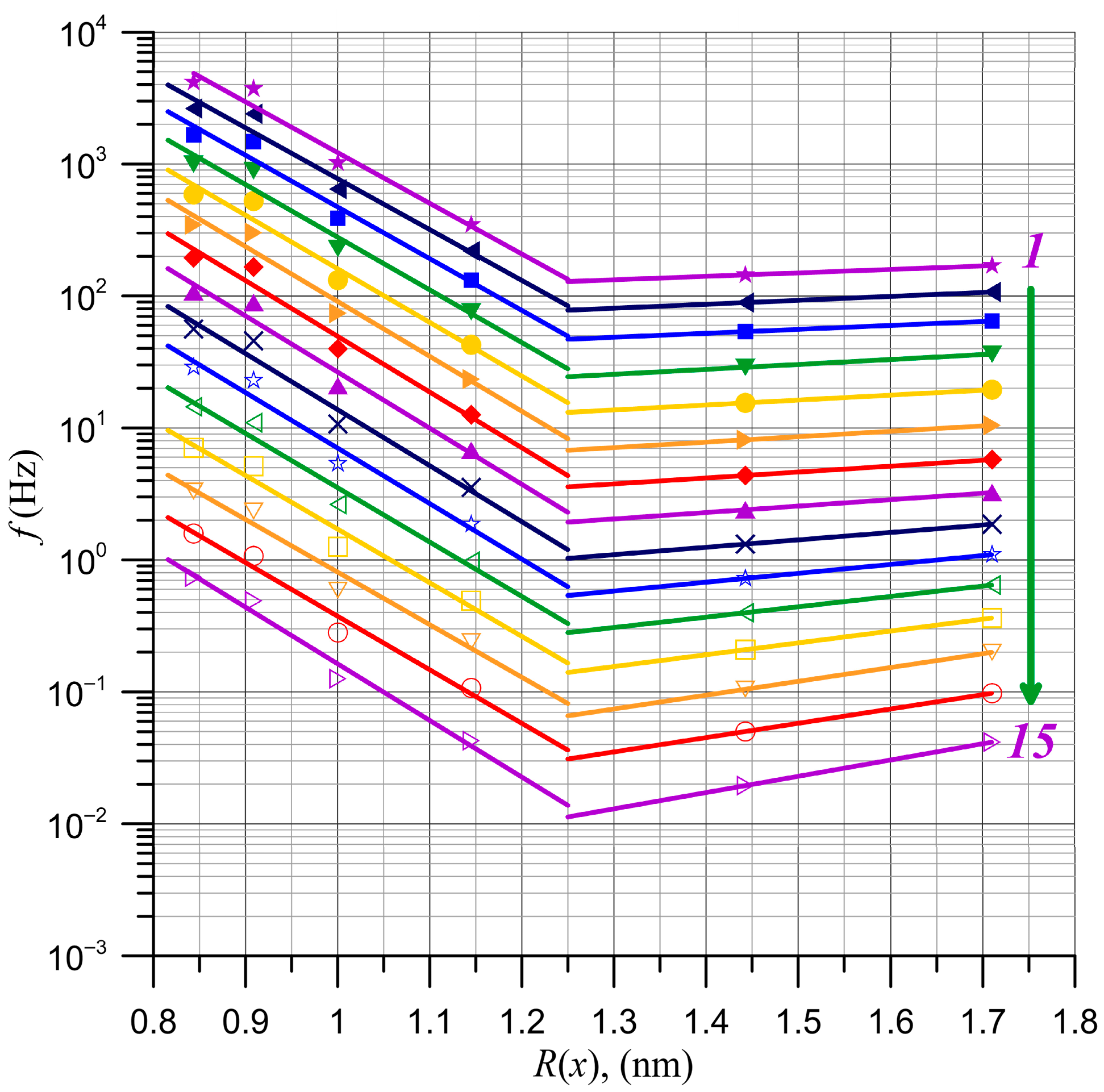

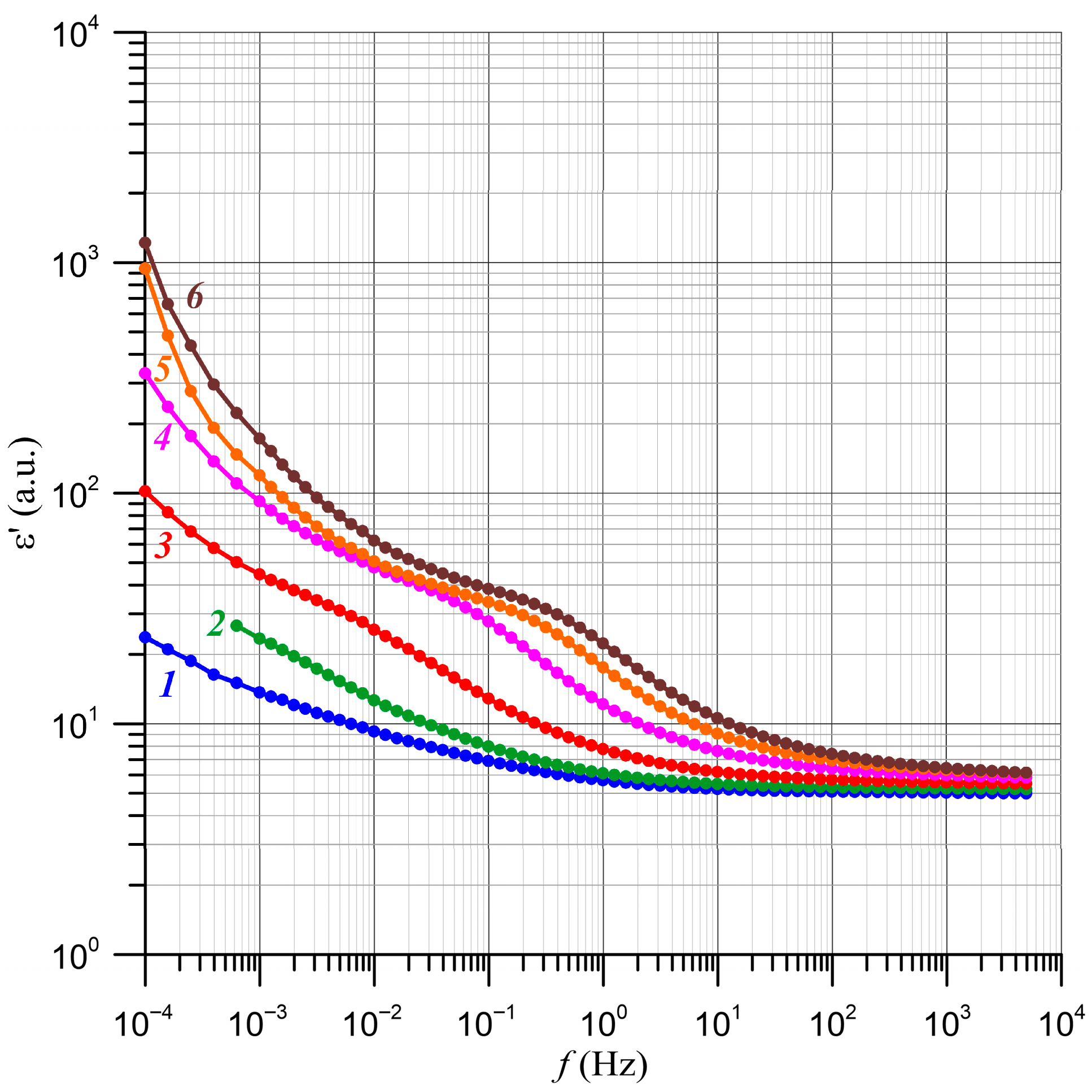

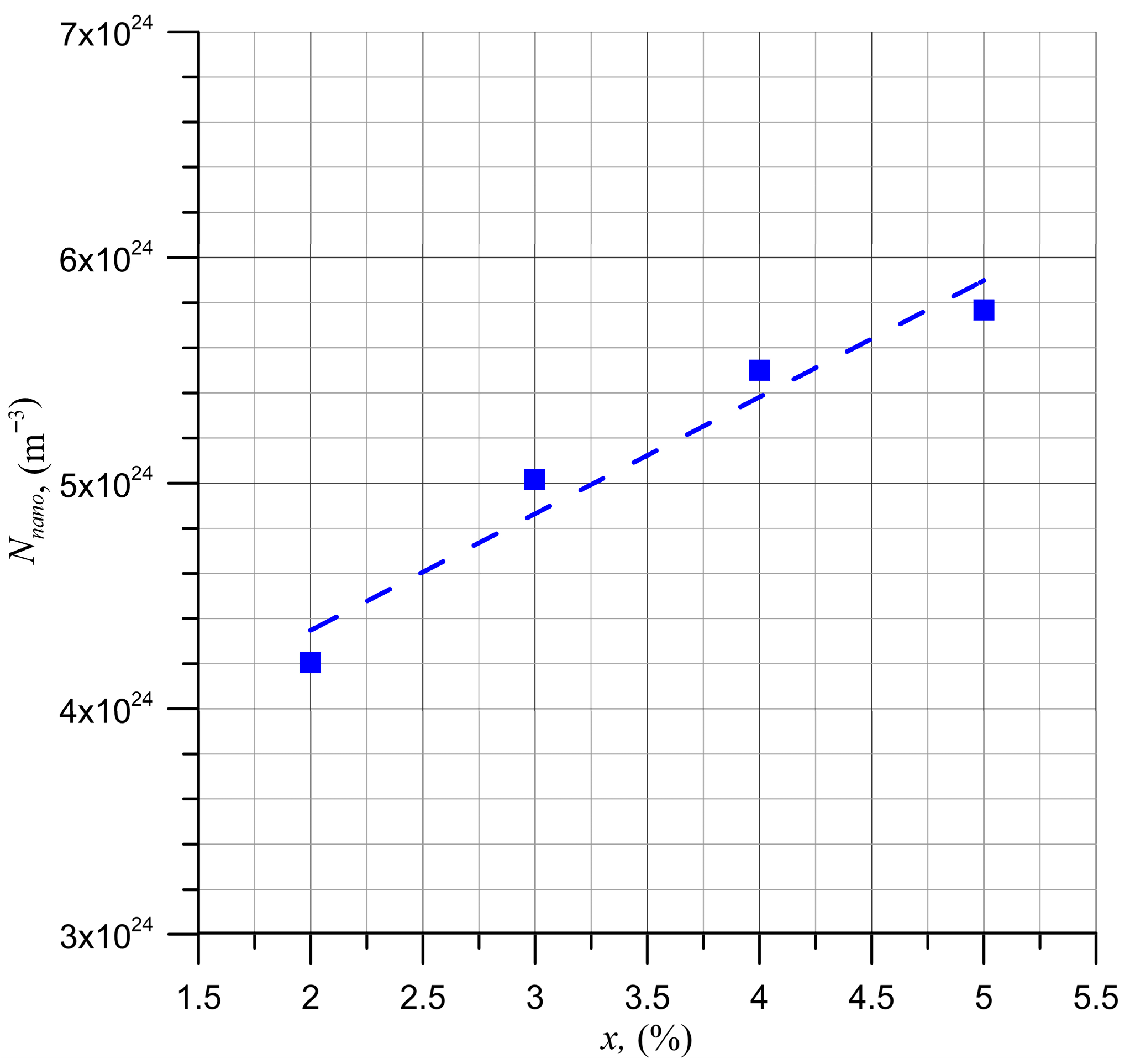

4. Determination of the Relative Relaxation Times Based on the Frequency Dependence of Conductivity

5. Determination of Nanodroplet Parameters

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Krause, C. Power transformer insulation—History, technology and design. IEEE Trans. Dielectr. Electr. Insul. 2012, 19, 1941–1947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oommen, T.V.; Prevost, T.A. Cellulose insulation in oil-filled power transformers: Part II—Maintaining insulation integrity and life. IEEE Electr. Insul. Mag. 2006, 22, 5–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amoiralis, E.I.; Tsili, M.A.; Kladas, A.G. Transformer design and optimization: A literature survey. IEEE Trans. Power Deliv. 2009, 24, 1999–2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fofana, I.; Wasserberg, V.; Borsi, H.; Gockenbach, E. Retrofilling conditions of high-voltage transformers. IEEE Electr. Insul. Mag. 2001, 17, 17–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fritsche, R.; Geissler, M.; Pukel, G.; Wolmarans, C. The Use of a Bio-Based Hydrocarbon Insulating Liquid in Power Transformers. In Proceedings of the IEEE 21st International Conference on Dielectric Liquids (ICDL), Sevilla, Spain, 29 May–2 June 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, W.; Wang, Z.; Chu, H.; Liu, G.; Qiao, X.; Feng, Y.; Zhang, J. Comparison of the basic properties of bio-based hydrocarbon liquids and mineral oils: A molecular dynamics structure and physicochemical properties synergistic Analysiss. Chem. Phys. Lett. 2025, 873, 142172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, W.; Liu, G.; Wang, Z.; Hao, J.; Dai, X.; Zhang, J. Electronic Properties of Bio-based Hydrocarbon Liquids Under Extreme Electric Fields: Molecular Insights Into Its Excellent Impulse Insulation Properties Based on DFT and First Principles. IEEE Trans. Dielectr. Electr. Insul. 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stuchala, F.; Rozga, P.; Malaczek, M.; Staniewski, J. Comparative Analysis of Selected Insulating Liquids Including Bio-Based Hydrocarbon and GTL in Terms of Breakdown and Acceleration Voltage at Negative Lightning Impulse. IEEE Trans. Dielectr. Electr. Insul. 2024, 31, 2443–2450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- NYTRO® BIO 300X—The New Bio-Based Alternative from Nynas. Transform. Technol. Mag. 2020, 46–51. Available online: https://www.powersystems.technology/community-hub/in-focus/nytro-bio-300x-the-new-bio-based-alternative-from-nynas.html (accessed on 5 October 2025).

- Wolmarans, C.; Feischl, T.; Radić, I.; Maljković, V. Factory Acceptance Test of a 40 MVA power transformer filled with a bio-based & biodegradable hydrocarbon insulating liquid. In Proceedings of the 41st CIGRE International Symposium, Ljubljana, Slovenia, 21–24 November 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Wolmarans, C.; Gamil, A.; Al-Abadi, A.; Milone, M.; Jornaan, J.; Hellberg, R. Type Testing of 80 MVA Power Transformer witha New Bio-Based, Biodegradable and Low Viscosity Insulating liquid. In Proceedings of the CIGRE Session 2022, Paris, France, 28 August–2 September 2022; p. 11125. [Google Scholar]

- Wolmarans, C.; Pahlavanpour, B.; Kalkan, G. Improving the sustainability and performance of power transformers with a bio-based hydrocarbon. In Proceedings of the Polaris Conference 2022, Glasgow, UK, 8–9 November 2022; pp. 1–4. [Google Scholar]

- Gielniak, J.; Graczkowski, A.; Moranda, H.; Przybylek, P.; Walczak, K.; Nadolny, Z.; Moscicka-Grzesiak, H.; Feser, K.; Gubanski, S. Moisture in cellulose insulation of power transformers—Statistics. IEEE Trans. Dielectr. Electr. Insul. 2013, 20, 982–987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Facilites Instructions, Standards and Techniques. Transformer Diagnostics; US Department of The Interior Bureau of Reclamation: Washington, DC, USA, 2003; Volume 3–31.

- Lelekakis, N.; Martin, D.; Guo, W.; Wijaya, J.; Lee, M. A field study of two online dry-out methods for power transformers. IEEE Electr. Insul. Mag. 2012, 28, 32–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, D.; Perkasa, C.; Lelekakis, N. Measuring paper water content of transformers: A new approach using cellulose isotherms in nonequilibrium conditions. IEEE Trans. Power Deliv. 2013, 28, 1433–1439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prevost, T.A.; Oommen, T.V. Cellulose insulation in oil-filled power transformers: Part I—History and development. IEEE Electr. Insul. Mag. 2006, 22, 28–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Subocz, J. Przewodnictwo i Relaksacja Dielektryczna Warstowywch Układów Izolacyjnych; Uczelniane, W., Ed.; Zachodniopomorski Uniwersytet Technologiczny (Szczecin) Wydaw; Uczelniane Zachodniopomorskiego Uniwersytetu Technologicznego w Szczecinie: Szczecin, Poland, 2012; ISBN 8376631136/9788376631134. [Google Scholar]

- Hao, J.; Liao, R.; Chen, G.; Ma, Z.; Yang, L. Quantitative analysis ageing status of natural ester-paper insulation and mineral oil-paper insulation by polarization/depolarization current. IEEE Trans. Dielectr. Electr. Insul. 2012, 19, 188–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mishra, D.; Haque, N.; Baral, A.; Chakravorti, S. Assessment of interfacial charge accumulation in oil-paper interface in transformer insulation from polarization-depolarization current measurements. IEEE Trans. Dielectr. Electr. Insul. 2017, 24, 1665–1673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zenker, M.; Kierczyński, K. The influence of electric field intensity on the activation energy of the DC conductivity the electrical pressboard of impregnated with synthetic ester. In Proceedings of the Photonics Applications in Astronomy, Communications, Industry, and High-Energy Physics Experiments 2017, Wilga, Poland, 28 May–6 June 2017; Romaniuk, R.S., Linczuk, M., Eds.; SPIE: Bellingham, WA, USA, 2017; Volume 10445, p. 104455Q. [Google Scholar]

- Fofana, I.; Yéo, Z.; Farzaneh, M. Dielectric response methods for diagnostics of power transformers. Recent Adv. Dielectr. Mater. 2009, 19, 249–299. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, S.L. The simulation analysis of transformer recovery voltage by field and circuit method based on PSO algorithm. In Proceedings of the 12th International Conference on the Properties and Applications of Dielectric Materials (ICPADM), Xi’an, China, 20–24 May 2018; pp. 610–613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, T.; Li, X.; Lv, H.; Tan, X. Parameter Identification and Calculation of Return Voltage Curve Based on FDS Data. IEEE Trans. Appl. Supercond. 2014, 24, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blennow, J.; Ekanayake, C.; Walczak, K.; García, B.; Gubanski, S.M. Field experiences with measurements of dielectric response in frequency domain for power transformer diagnostics. IEEE Trans. Power Deliv. 2006, 21, 681–688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, X.; Liu, J.; Lai, B.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, C. FDS Measurement-Based Moisture Estimation Model for Transformer Oil-Paper Insulation Including the Aging Effect. IEEE Trans. Instrum. Meas. 2021, 70, 6006810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen, H.; Cheng, L.; Jiang, Y.; Zhu, T.; Chen, Z.; Dai, X.; Gao, C. Influence of Water Molecules on Polarization Behavior and Time–Frequency Dielectric Properties of Cellulose Insulation. J. Electr. Eng. Technol. 2021, 16, 1559–1571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, H.; Mu, H.; Zhang, D.; DIng, N.; Wu, Y.; Zhang, G.; Tian, J.; Liang, Z. Analysis of FDS Characteristics of Oil-Impregnated Paper Insulation Under High Electric Field Strength Based on the Motion of Charge Carriers. IEEE Trans. Dielectr. Electr. Insul. 2021, 28, 1153–1161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Megger. IDAX 300/350—Insulation Diagnostic Analyzers; Megger: Dover, UK, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- OMICRON Electronics Asia Limited. DIRANA—The Fastest Way of Moisture Determination of Power- and Instrument Transformers and Condition Assessment of Rotating Machines; OMICRON electronics Asia Limited: Shanghai, China, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Zukowski, P.; Kierczynski, K.; Rogalski, P.; Okal, P.; Zenker, M.; Pajak, R.; Szrot, M.; Molenda, P.; Koltunowicz, T.N. Research on the Influence of Moisture in the Solid Insulation Impregnated with an Innovative Bio-Oil on AC Conductivity Used in the Power Transformers. Energies 2024, 17, 5164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koltunowicz, T.N.; Kierczynski, K.; Rogalski, P.; Okal, P.; Pahlavanpour, B.; Wolmarans, C.; Pajak, R.; Zenker, M.; Szrot, M.; Molenda, P.; et al. Measurements of mechanical, thermal and electrical parameters for insulating bio-oils used in the power industry. Fuel 2025, 397, 135463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Żukowski, P.; Kierczyński, K.; Kołtunowicz, T.N.; Rogalski, P.; Subocz, J. Application of elements of quantum mechanics in analysing AC conductivity and determining the dimensions of water nanodrops in the composite of cellulose and mineral oil. Cellulose 2019, 26, 2969–2985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Fan, X.; Zhang, Y.; Lai, B.; Jiao, J. Analysis of low-frequency polarisation behaviour for oil-paper insulation using logarithmic-derivative spectroscopy. High Volt. 2021, 6, 460–469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fofana, I.; Hemmatjou, H.; Meghnefi, F.; Farzaneh, M.; Setayeshmehr, A.; Borsi, H.; Gockenbach, E. On the frequency domain dielectric response of oil-paper insulation at low temperatures. IEEE Trans. Dielectr. Electr. Insul. 2010, 17, 799–807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ekanayake, C.; Gubanski, S.M.; Graczkowski, A.; Walczak, K. Frequency Response of Oil Impregnated Pressboard and Paper Samples for Estimating Moisture in Transformer Insulation. IEEE Trans. Power Deliv. 2006, 21, 1309–1317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moranda, H.; Moscicka-Grzesiak, H. A Particularly Dangerous Case of the Bubble Effect in Transformers That Appeared in a Large Mass of Pressboard Heated by Mineral Oil. Energies 2025, 18, 380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- EN 60814:1997; Insulating liquids—Oil-Impregnated Paper and Pressboard—Determination of Water by Automatic Coulometric Karl Fischer Titration. iTeh, Inc.: Newark, DE, USA, 1997.

- Koch, M.; Tenbohlen, S.; Krüger, M.; Kraetge, A. A Comparative Test and Consequent Improvements on Dielectric Response Methods. In Proceedings of the 15th International Symposium on High Voltage Engineering (ISH 2007), Ljubljana, Slovenia, 27–31 August 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Gubanski, S.M.; Blennow, J.; Karlsson, L.; Feser, K.; Tenbohlen, S.; Neumann, C.; Moscicka-Grzesiak, H.; Filipowski, A.; Tatarski, L. Reliable Diagnostics of HV Transformer Insulation for Safety Assurance of Power Transmission System REDIATOOL—A European Research Project. In Proceedings of the Paris Session 2006, Paris, France, 20–22 November 2006; CIGRE: Paris, France, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, D.; Yun, H.; Zhan, J.; Sun, X.; He, W.; Niu, C.; Mu, H.; Zhang, G.J. Insulation condition diagnosis of oil-immersed paper insulation based on non-linear frequency-domain dielectric response. IEEE Trans. Dielectr. Electr. Insul. 2018, 25, 1980–1988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Żukowski, P.; Kołtunowicz, T.N.; Kierczyński, K.; Rogalski, P.; Subocz, J.; Szrot, M.; Gutten, M.; Sebok, M.; Jurcik, J. Permittivity of a composite of cellulose, mineral oil, and water nanoparticles: Theoretical assumptions. Cellulose 2016, 23, 175–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mott, N.F.F.; Davis, E.A.A. Electronic Processes in Non-Crystalline Materials, 2nd ed.; Clarendon Press: Oxford, UK; New York, NY, USA, 1979; ISBN 9780198512882. [Google Scholar]

- Ravich, Y.I.; Nemov, S.A. Hopping conduction via strongly localized impurity states of indium in PbTe and its solid solutions. Semiconductors 2002, 36, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Żukowski, P.; Kołtunowicz, T.; Partyka, J.; Węgierek, P.; Komarov, F.F.; Mironov, A.M.; Butkievith, N.; Freik, D. Dielectric properties and model of hopping conductivity of GaAs irradiated by H+ ions. Vacuum 2007, 81, 1137–1140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, R.; Ning, Y.; Jones, E.R.; Cunningham, V.J.; Penfold, N.J.W.; Armes, S.P. Stimulus-responsive block copolymer nano-objects and hydrogels: Via dynamic covalent chemistry. Polym. Chem. 2017, 8, 5374–5380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goudarzi, Z.; Parvin, N.; Sharifianjazi, F. Formation of hydroxyapatite on surface of SiO2–P2O5–CaO–SrO–ZnO bioactive glass synthesized through sol-gel route. Ceram. Int. 2019, 45, 19323–19330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tseng, K.H.; Chung, M.Y.; Chang, C.Y. Parameters for Fabricating Nano-Au Colloids Through the Electric Spark Discharge Method with Micro-Electrical Discharge Machining. Nanomater 2017, 7, 133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Billas, I.M.L.; Châtelain, A.; De Heer, W.A. Magnetism of Fe, Co and Ni clusters in molecular beams. J. Magn. Magn. Mater. 1997, 168, 64–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jönsson, B.J.; Turkki, T.; Ström, V.; El-Shall, M.S.; Rao, K.V. Oxidation states and magnetism of Fe nanoparticles prepared by a laser evaporation technique. J. Appl. Phys. 1996, 79, 5063–5065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Charitidis, C.A.; Georgiou, P.; Koklioti, M.A.; Trompeta, A.F.; Markakis, V. Manufacturing nanomaterials: From research to industry. Manuf. Rev. 2014, 1, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daraio, C.; Jin, S. Synthesis and Patterning Methods for Nanostructures Useful for Biological Applications. In Nanotechnology for Biology and Medicine; Fundamental Biomedical Technologies ((FBMT)); Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2012; pp. 27–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; Sun, D.; Fu, Y.; Du, H. Recent advances of superhard nanocomposite coatings: A review. Surf. Coat. Technol. 2003, 167, 113–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Vlack, L.H. Materials Science for Engineers; Addison-Wesley Publishing Company: Boston, MA, USA, 1970; ISBN 978-0201080742. [Google Scholar]

- Zukowski, P.; Kołtunowicz, T.N.; Kierczyński, K.; Subocz, J.; Szrot, M.; Gutten, M. Assessment of water content in an impregnated pressboard based on DC conductivity measurements theoretical assumptions. IEEE Trans. Dielectr. Electr. Insul. 2014, 21, 1268–1275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shklovskii, B.I.B.I.; Efros, A.L.A.L. Electronic Properties of Doped Semiconductors; Springer Series in Solid-State Sciences; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 1984; Volume 45, ISBN 978-3-662-02405-8. [Google Scholar]

- Raetzke, S.; Koch, M.; Krueger, M.; Talib, A. Condition Assessment of Instrument Transformers Using Dielectric Response Analysis. Elektrotech. Inftech. 2016, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| No. | σi | K(σi) | R2 |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 5.00 × 10−10 | 8.850 | 0.8749 |

| 2 | 3.78 × 10−10 | 8.879 | 0.8612 |

| 3 | 2.86 × 10−10 | 9.026 | 0.8708 |

| 4 | 2.16 × 10−10 | 9.192 | 0.8677 |

| 5 | 1.64 × 10−10 | 9.357 | 0.8645 |

| 6 | 1.24 × 10−10 | 9.581 | 0.8726 |

| 7 | 9.35 × 10−11 | 9.728 | 0.8815 |

| 8 | 7.07 × 10−11 | 9.798 | 0.8910 |

| 9 | 5.35 × 10−11 | 9.780 | 0.9018 |

| 10 | 4.04 × 10−11 | 9.686 | 09127 |

| 11 | 3.06 × 10−11 | 9.485 | 0.9330 |

| 12 | 2.31 × 10−11 | 9.361 | 0.9494 |

| 13 | 1.75 × 10−11 | 9.178 | 0.9575 |

| 14 | 1.32 × 10−11 | 9.349 | 0.9689 |

| 15 | 1.00 × 10−11 | 9.880 | 0.9703 |

| Average | 9.409 | 0.9052 | |

| Std. Dev. | 0.3239 | 0.03895 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Kierczyński, K.; Kołtunowicz, T.N.; Bondariev, V.; Okal, P.; Zenker, M.; Szrot, M.; Molenda, P.; Cichoń, A.; Żukowski, P. Research on the Alternating Current Properties of Cellulose–Innovative Bio-Oil Nanocomposite as the Fundamental Component of Power Transformer Insulation—Determination of Nanodroplet Dimensions and the Distances Between Them. Energies 2025, 18, 6311. https://doi.org/10.3390/en18236311

Kierczyński K, Kołtunowicz TN, Bondariev V, Okal P, Zenker M, Szrot M, Molenda P, Cichoń A, Żukowski P. Research on the Alternating Current Properties of Cellulose–Innovative Bio-Oil Nanocomposite as the Fundamental Component of Power Transformer Insulation—Determination of Nanodroplet Dimensions and the Distances Between Them. Energies. 2025; 18(23):6311. https://doi.org/10.3390/en18236311

Chicago/Turabian StyleKierczyński, Konrad, Tomasz N. Kołtunowicz, Vitalii Bondariev, Paweł Okal, Marek Zenker, Marek Szrot, Paweł Molenda, Andrzej Cichoń, and Paweł Żukowski. 2025. "Research on the Alternating Current Properties of Cellulose–Innovative Bio-Oil Nanocomposite as the Fundamental Component of Power Transformer Insulation—Determination of Nanodroplet Dimensions and the Distances Between Them" Energies 18, no. 23: 6311. https://doi.org/10.3390/en18236311

APA StyleKierczyński, K., Kołtunowicz, T. N., Bondariev, V., Okal, P., Zenker, M., Szrot, M., Molenda, P., Cichoń, A., & Żukowski, P. (2025). Research on the Alternating Current Properties of Cellulose–Innovative Bio-Oil Nanocomposite as the Fundamental Component of Power Transformer Insulation—Determination of Nanodroplet Dimensions and the Distances Between Them. Energies, 18(23), 6311. https://doi.org/10.3390/en18236311